- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 23 September 2019

Comparison of the effectiveness of lectures based on problems and traditional lectures in physiology teaching in Sudan

- Nouralsalhin Abdalhamid Alaagib 1 ,

- Omer Abdelaziz Musa 2 &

- Amal Mahmoud Saeed 1

BMC Medical Education volume 19 , Article number: 365 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

49 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Lectures are one of the most common teaching methods in medical education. Didactic lectures were perceived by the students as the least effective method. Teaching methods that encourage self-directed learning can be effective in delivering core knowledge leading to increased learning. Problem based learning has been introduced as an active way of learning but it has some obstacles in developing countries where the intake is huge with minimum resources. This study introduces a new teaching approach: lectures based on problems (LBP) and evaluates their effectiveness compared to traditional lectures (TL) in physiology teaching.

LBP and TL were applied in physiology teaching of medical students at University of Science and Technology during their study of introduction to physiology and respiratory physiology courses. Equal number of lectures was given as LBP and as TL in each course. Students were given quizzes at the end of each course which were used to compare the effectiveness of the two types of lectures. A questionnaire was used to assess students’ satisfaction about LBP and the perceived effects of the two methods on the students’ attitude and practice towards learning physiology.

In LBP the students have better attention ( P = 0.002) and more active role ( P = 0.003) than in TL. Higher percentage of students think that LBP stimulated them to use references more ( P = 0.00006) and to use the lecture time more effectively ( P = 0.0001) compared to TL. However, there was no significant difference between LBP and TL in the awareness of the learning objectives. About 64% of students think that LBP is more enjoyable and it improved their understanding of physiology concepts. Comparison of the students’ quiz marks showed that the means of the students’ marks in the introduction to physiology and respiratory courses were higher in the quizzes of LBP than in TL with a significant difference between them (( P = .000), ( P = .006) respectively.

Conclusions

LBP improved students’ understanding of physiology concepts and increased students’ satisfaction about physiology learning. LBP achieved some of the objectives of PBL with the minimum resources and it can be used to improve the effectiveness of the lectures.

Peer Review reports

Lectures are one of the most common teaching methods in medical education. It has been suggested that teaching methods that enhance engagement and encourage self-directed learning can be effective in delivering core knowledge and explaining difficult concepts leading to increased learning [ 1 ]. Transformation began with the introduction of problem-based learning (PBL) in some medical schools; more recently, lectures has increasingly been replaced by team-based learning.

Traditional, didactic lectures were perceived by the students as the least effective method used, yet involving students actively within the lecture time was regarded as a more effective learning tool [ 2 ]. Lectures have the advantage of sharing information with a large number of students and it can be effective in transmitting factual information [ 3 ]. Thus, lectures can be an effective teaching method when the lecture is given as large-group interactive learning sessions with discussion and frequent questions to students who have prepared in advance [ 4 , 5 ]. Although the term “effective” has been widely used, the definitions of effectiveness is inescapably linked to the outcomes of educational activity through evaluation of the extent to which an activity approximates the achievement of its goals [ 6 ]. Generally some of the characteristics of effective teaching focus on teacher performance while others focus on student learning needs and outcomes [ 7 ]. Young and Shaw proposed six major dimensions of effective teaching: value of the subject, motivating students, a comfortable learning atmosphere, organization of the subject, effective communication, and concern for student learning [ 8 ]. Moreover, effective learning actively involves the student in metacognitive processes of planning, monitoring and reflecting. It is promoted by activity with reflection, collaboration for learning, learner responsibility for learning and learning about learning [ 9 ].

Lecturing, whether effective or not, is still the most commonly used learning method as it is an economical and practical method; especially when the number of students is large and the available resources are limited. For effective learning educationalists must change their use of the lecture time and make use of methods and techniques in which students are more active, communicating and collaborating for learning; with evaluation of the effectiveness of these methods by the students on their learning. Interactive lecture is an example of how knowledge about meaningful learning can be implemented in the lecture hall [ 10 ]. In interactive lecture students are asked to actively participate and process knowledge throughout the lecture. They also take an active part in contextualizing the content and directing the focus of the lecture towards areas they find difficult to understand [ 11 ]. Therefore, teachers can use the lecture to encourage students to construct their own understanding of concepts, relationships, and enhance application of theories by choosing suitable student centered learning approaches [ 12 ]. Chilwant compared structured interactive lectures with conventional lectures in two groups of second year medical students. The effect of two methods was evaluated by giving questionnaire and MCQs. Although their results showed no significant difference in average MCQ marks of two groups, students in the interactive group enjoyed being actively involved in the lecture which increased their engagement, attention during the lecture and stimulated their critical thinking [ 5 ]. Fyrenius et. al. presented a structure of organizing lectures into three phases, based on the theoretical prerequisites of meaningful learning like pre-understanding, relevance and active involvement [ 11 ]. The three phases are: introductory lecture (1–2 h), in-depth lecture (1–2 h) and application lecture (1–2 h) [ 11 ]. Moreover, lectures can be enriched by the use of educational media. Some studies showed that involvement of students in a large room or a lecture hall through voluntary participation in additional active learning exercises with aid of software [ 13 ] and use of game-like format of the review session and its custom-designed software, that combines interactivity, team learning and peer-to-peer instruction [ 14 ], resulted in an improvement in understanding and application of physiological concepts and enriched students’ learning experiences. Many Studies showed that students prefer learning approaches in which the students have more active role than the TL like case based learning [ 15 ], team based learning [ 16 ], small group discussion [ 17 ] and flipped classroom.

It is not only the method of teaching that affects the learning process; students’ own learning approaches influence their learning significantly . The learning approach adopted by students appears to be an important factor in determining both the quantity and the quality of their learning resulting in different learning outcomes [ 18 ]. Learning styles and learning approaches differ among medical students [ 19 ], and this could be partly attributable to their preferred learning style and partly to the context in which the learning takes place. Three basic approaches have been identified: surface, deep and strategic approaches [ 18 ]. The most desirable and successful is the deep approach in which students are motivated by an interest in the subject material. Their intention is to understand the material, to recognize its vocational relevance and to relate it to previous knowledge and personal experiences. The surface approach is rote learning in which students focus is on memorization pieces of information in isolation from the wider context motivated by either a desire to complete the course or a fear of failure. The main motivation of students using the strategic approach is achievement of high grades so they use either the surface or deep approach depending on what they feel would produce the most successful results [ 18 ]. They are much more influenced by the context than by the nature of the task itself. In TL students are passive recipient of information and have insufficient exposure to the content which encourages superficial learning. Abraham et. al. found that PBL promotes a deep approach to physiology learning and they suggested that physiology teaching outcomes could be improved through the use of the PBL teaching model [ 20 ]. Numerous studies that compared lecture-based learning (LBL) models to the PBL model showed certain advantages of PBL with respect to improving student abilities in active learning, critical thinking, communication skills, teamwork, critical thinking, peer-learning, self-learning and research skills [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. However, a number of disadvantages of PBL were reported like: time constraints, inadequate resources, inconsistency in knowledge acquisition, inadequate contribution of clinicians and lack of required faculty training on PBL facilitation and required student preparation and motivation [ 24 ]. Moreover, PBL model seems difficult to apply in educational context with the large number of students and limited resources.

The main critique for LBL is the passive delivery of knowledge in a teacher centered approach; and students have insufficient exposure to the content which encourages superficial learning. However, interactive lectures proved to be effective in learning. For effective learning educators may need to use a variety of learning experiences [ 25 ]. A teaching model that combines the benefits of PBL and interactive lecture, by delivering lectures based on problems (LBP), may lead to better learning outcome with more active role of students during the lecture. This study introduces a new teaching approach LBP; to our knowledge they have not been used anywhere before. The aim of this study is to assess the effectiveness of LBP compared to TL and to evaluate the perceived effects of the two methods on the students’ attitude and practice towards learning physiology.

Study design

This is an interventional quasi study done in University of Science and Technology in Sudan in 2018. In this university, physiology is taught by the traditional curriculum and the duration of the lecture is 2 h. The study was done during the introduction to physiology course in the second semester of the first year and the respiratory course during the third semester in the second year for the same batch of medical students. In the introduction to physiology and the respiratory courses equal numbers of lectures were taught in a form of TL and LBP and both types were delivered by the same course instructor. Two of the authors contributed in teaching of the lectures by the two methods and each course was taught by a different instructor.

Steps of LBP:

Step 1: Introducing the clinical problem to the whole class in 5 min.

Step 2: Clarifying what is not clear in the scenario within the class in 5 min.

Step 3: Paired student analysis of the problem for clues and key words and suggesting generally what the problem is about in 15 min. In this step students can use their books or mobile phones to search in the internet.

Step 4: In the class, students share with the instructor what they have worked out in step 3. This takes about 10 min.

Step 5: Students are given 10 min to formulate learning objectives based on the scenario and each pair of students should write down at least two learning objectives.

Step 6: The instructor goes through the learning objectives in a 45–50 min lecture. The objectives of the problem can be taught in more than one lecture with reference to the same problem.

Step 7: Later in the small groups tutorial after the students studied the learning resources they discuss the problem again and answer some short answer questions based on the scenario.

Step 8: At the start of the next lecture, students are given quizzes on the previous one in 15–20 min. Each student has to solve these quizzes alone and then the answers are shared with the class.

Inclusion criteria

All medical students in Batch 21 at University of Science and Technology. Each student should have attended at least 3 lectures of each of the TL and LBP in each course.

Exclusion criteria

Students who did not attend 25% of the lectures in any of the two courses or did not attend the end of course test were excluded. Students who refused to participate or did not sign the informed consent were also excluded from the study.

Sampling technique

By the end of the two courses, students were contacted by the investigator in the lecture hall. They were informed about the study and its objectives. To avoid measurement bias it was stated clearly that participation in the study will not affect their exam performance or grades by any means. Moreover, the data was collected using self– administered questionnaire that contains no names or identifiable information. An informed consent form attached with the questionnaire was passed by a teacher assistant to the students in the lecture hall after completion of the two courses. One hundred and forty six out of 183 students responded and agreed to fill the questionnaire.

To compare the effectiveness of the two methods quizzes were given to the students at the end of each course; in a form of multiple choice questions and short answer questions; covering the topics given as LBP and TL with equal weight. The quizzes tested some factual knowledge in addition to application of knowledge to explain some clinical signs and symptoms. Most questions asked were “how,” “what is the cause”, “what would happen if” or “explain” questions in addition to some questions to “define”, to “classify” or to draw a schematic diagram to explain a mechanism. All students were subjected to the same end of course quizzes with no difference between the groups regarding the kinds of knowledge tested. The results of these quizzes were used to compare the effectiveness of the two methods. The marks of the quizzes were taken from the secretary office in a form of excel sheet that doesn’t contain any names only the results of the whole class.

A questionnaire was filled by each participant to assess the perceived effect of the two methods on the students’ attitude and practice towards learning physiology through questions that determined the type of lectures in which the students had more active role and in which they were more aware to the learning objectives. Students were also asked about the type of lectures which stimulated them to use the lecture time more effectively, to use references and study resources and the type of lecture students think will enable them to score higher marks in the exam. Likert scale rating questions were used to assess students’ satisfaction about LBP and whether LBP improved their understanding of physiology concepts.

Results were saved and analyzed using SPSS version 23. Descriptive statistics were displayed in percentages and means ± SD. To evaluate the effectiveness of LBP, comparisons of students’ perception to certain items regarding LBP and TL were done using Z- test. According to Bonferroni criteria when assessing multiple tests for the same variable the level of significance should be adjusted by number of tests. Here the level of significance was adjusted as 0.05/6 = 0.0083 (where 6 is the number of tested items). Therefore, P value < 0.0083 is significant and P value < 0.0016 is considered highly significant. Comparison of the effectiveness of the two methods regarding students’ performance was done using independent t- test and a P value of ≤0.05 was taken as significant. Students’ satisfaction about LBP in physiology teaching was displayed as proportions.

One hundred and forty six out of 183 students responded and filled the questionnaire with a participation rate of 79.8%. Their age ranged between 17 and 24 years; 88.3% with age of 18–20 and the mean age was 18.7 ± 1.1 years. Two third of the class (62%) were females and 38% were males.

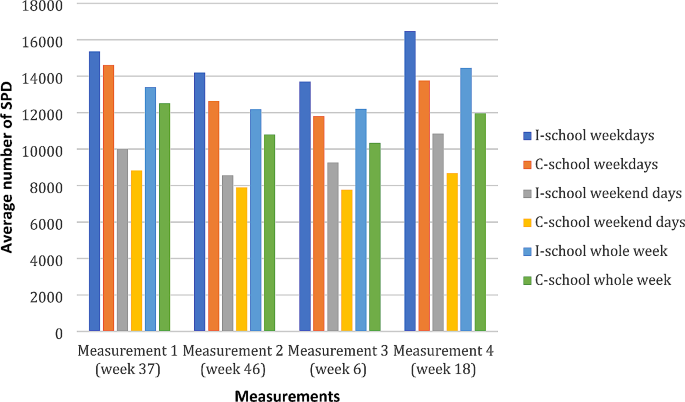

Comparison of the effect of the type of the lecture on students’ attitude and practice towards learning physiology is shown in Table 1 .

Results showed that in LBP students have significantly better attention ( P = 0.002) and more active role ( P = 0.003) than in TL. Fifty one percent of students think that they have better attention in LBP compared to 24% in the TL. Almost half the class (53.4%) have more active role in the LBP compared to 27.6% in the TL.

Higher percentage of students think that LBP stimulated them to use references more ( P = 0.00006) and to use the lecture time more effectively ( P = 0.0001) compared to TL with statistically highly significant difference between the two methods. Fifty eight percent of students think that they use the lecture time more effectively in the LBP and that the LBP stimulated them more to use the references and study resources to answer the questions more than the TL (Table 1 ). However, there was no significant difference between LBP and TL in the awareness of the learning objectives and the type of the lecture which students think will enable them to score higher marks in the exam (Table 1 ). Almost 20% of students found no difference between the two lectures methods regarding parameters reported in Table 1 .

Reflections of students about LBP using the Likert scale rating (Table 2 ) showed that about 64% agreed that LBP improved their understanding of physiology concepts and that LBP are more enjoyable than TL. Almost two third of the class (64.4%) think that LBP should be continued and improved; 13% disagreed and 22.6% couldn’t decide.

Comparison of students’ quiz marks on the two methods was done using independent t-test (Table 3 ). The means of students’ marks in the introduction to physiology course ( n = 101) and respiratory course ( n = 146) were higher in the quizzes of LBP than in traditional lectures with a significant difference between the two methods (( P = .000), ( P = .006) respectively).

In the introductory course 13/101 (12.87%) had the same score in the quizzes of the two methods. In the respiratory course 15/146 students (10.27%) score the same in the quizzes of the two methods.

The results of this study showed that about half the class thinks that they have more active role and better attention in the LBP compared to the TL. Although TL allow sharing a large body of content with a large number of students, they often promote passive and superficial learning. In TL the objectives of the lecture are shown at the start of the lecture and they are covered adequately by the teacher. However, students sitting passively may find difficulty in paying attention throughout the lecture. In LBP, when students are analyzing the problem for key words, searching the internet to know what is the problem about and during writing the learning objectives the instructor had to move throughout the lecture hall to monitor the class. It was rare to find a pair of students who were not seriously involved in the process. Throughout the lecture the instructor and the students try to link the lecture contents to the learning objectives and to the clinical scenario which contributed to the increase in students’ attention during the lecture. One of the most active interactions during LBP occurred when students shared the key words they have worked out and their suggestions of what the clinical problem could be about. This encouraged them to follow the lecture with enthusiasm and curiosity to find out whether they were right and to add what they missed. These results support the idea that the culture of the lecture is still acceptable by the students and that it can be an effective learning mechanism given that the students are engaged actively within the lecture [ 2 ].

In this study assessment of students attitude and practice towards learning physiology showed that a significantly higher percentage of students (58.2%) think that they use the lecture time more effectively in LBP than in TL and that LBP stimulated them more to use the references and study resources to learn physiology. By highly structuring the activities in LBP e.g. introducing a clinical problem, identifying difficult terminologies, analyzing the problem for clues and key words, formulating the learning objectives by the students and sharing the answers of the quizzes with the whole class, an active learning environment was created that enabled students to think, seek for information and use references, speak, and question freely. In LBP, the instructor may need to adopt an informal approach that promotes active learning through pair student interaction and discussion. Thus, the lecture became intellectually stimulating and challenging, as well as highly interactive. In LBP students are busy and participating actively in the lecture without significant loss of time. However, when more than hundred student talk at the same time the lecture hall may become noisy; that the instructor has to take control of the class and may need to use a signal to end conversations to be able to proceed [ 10 ]. TL seem easier for the instructor in controlling the class and managing the lecture time than LBP. In LBP highly structured classroom monitoring and time management is necessary to facilitate students’ interactions within the class and to proceed with the steps of LBP. Actually, the large number of students in the lecture hall is a major challenge for most educators who wish to innovate in teaching to make the lectures interactive and student centered. The use of student-centered active-learning instructional approaches, such as active- and inquiry-oriented learning in the classroom, improved student attitudes and increased learning outcomes relative to a standard lecture format [ 26 , 27 ]. Students centered learning approach shifts the focus from teaching to learning and promotes a learning environment favorable of the metacognitive development necessary for students to become active independent learners and critical thinkers.

In this study 64.3% of students think that LBP improved their understanding of physiology concepts. In step7 of LBP, in the small groups tutorials after the students studied the learning resources and revised what they have learned in the lecture, they discuss the problem again and answer some questions based on the scenario. The interactions in this step with peers and facilitators give opportunities to the learners to apply what they have learned and allow exchange of information and construction of knowledge. In the lecture hall, students were given quizzes on the previous lesson and each student had to solve and then the answers were shared with the whole class. This can be considered a type of test-enhanced learning which facilitates retention of factual knowledge and it binds testing directly to teaching and the educational process. Larsen et al. reported that being tested on the material after reading it or hearing a lecture about a topic, enhance later retention of information and it is a better way to learn material than rereading it [ 28 ]. It was suggested that this technique may be particularly effective as students struggle to master complex and extensive sets of information, such as in physiology or pharmacology [ 28 ]. In addition, if students test themselves as a strategy for learning, they can discover their own areas of weakness and re-study material in a purposeful way. In LBP quizzes are given at the start of the next lecture about the previous lesson. It was suggested that for tests to enhance memory, they should be given relatively soon after learning and should be derived specifically from the information learned [ 29 ].

Sharing the answers of the quizzes with the whole class and providing feedback led, in most of the times, to discussion among the students in the class and this provided a good material for later discussion in the tutorial session. However, most likely it is the peer interaction rather than knowing the correct answer per se that promotes student learning [ 30 ] simply from peer influence of knowledgeable students on their neighbors. Furthermore, providing feedback enhances the benefits of testing by correcting errors and confirming correct responses [ 31 ]. This feedback and the short discussion that occurred in the lecture theatre allowed the instructor to have an idea about the depth of student understanding and the areas that need further clarification to be included in the tutorial’s questions.

We found that 58.9% of students think that LBP are more satisfactory. Two third of the students (about 64%) found LBP more enjoyable than TL and that LBP should be continued and improved. Moreover, comparison of the effectiveness of the two methods showed that the performance of students was significantly higher in the quizzes of LBP than those of TL in both the introduction to physiology and respiratory physiology courses. In LBP the use of quizzes and sharing and discussing the answers enhanced students’ learning and contributed to the better performance. However, the satisfaction most likely came from the problems introduced at the start of the lecture and the ability to apply knowledge of basic science on clinical setting which encourage deep learning approach. By using a clinical problem in LBP, students became clinically oriented and they appreciated the value of the basic information given at their level. Horne and Rosdahl showed that students found the case-based sessions better than TL format with respect to the overall learning experience, enjoyment of learning and increasing retention and ability to apply knowledge [ 32 ]. Basic science knowledge learned in the context of a clinical case is better comprehended and more easily applied by medical students than learning pure basic science knowledge [ 33 , 34 ]. In medical education, physiology is not just the acquisition of fact and the understanding of the physiological mechanisms, but rather the ability to use this basic knowledge to understand the process of diseases, to explain some symptoms and signs, to suggest treatment and to acquire the skill of critical thinking and problem solving.

In spite of the fact that students’ performance was significantly better in the quizzes following LBP than the TL, assessment of students’ perception about their exam performance showed that higher percentage of students (38.4%) thinks that they will score better in the exam when they had TL compared to 35.6% who choose LBP and 26% think their score will be the same when they are taught by LBP or TL. This can be explained by the familiarity of the student to the didactic learning approach. Generally the means of learning in secondary education in Sudan put more responsibility on the teacher mainly ‘chalk and talk’ experience. Students in the first year in the university think that in the TL, they are given all the information needed to answer the exam questions unlike LBP in which they need to be self-learners and to solve questions and to use the references to reach the level of understanding needed to answer the exam questions. A second reason might be the anxiety felt by the students at time of exams. In this study students were more satisfied and enjoyed LBP more than TL; but when it comes to the exam students may become uncomfortable with LBP and may feel uncertain about what they have learned. They may think that they have wasted time on activities without knowing exactly what they have learned. Therefore, students may prefer more concrete and defined blocks of information given in the TL. They think their performance in the exam will be better when they know exactly the limits and boundaries of the subject they are going to be tested on.

In this study we found about 25% of students couldn’t decide and were neutral in all the investigated items regarding their satisfaction about LBP. This can be explained by the fact that students in this study were in the first year of their university study and they might be unaware of the benefits of the new active method and some students may be resistant to the active learning methods due to the increased self-learning and work outside the class. One of the studies that investigated student responses to active learning tasks showed that on initial exposure to the method, the majority of students found active methods strange, threatening and ineffectual. It is only with time and exposure to the method a change in students behavior may occur and students become comfortable and confident both with the method and their role [ 2 ]. However, most medical students later know that they must become lifelong learners to continue and succeed in their career. Therefore, students need the help of the educators to develop their skills in active self-directed learning and to practice more techniques of active learning.

Limitation of the study

For LBP to be applied efficiently the teachers may need training on the steps of LBP. Like most of the active learning approaches time management is a challenge for educators who wish to use LBP. In this study students were given the clinical problem in the lecture. It would have been better if they were given the problem before the lecture to be prepared in advance. Also the use of clickers or colored cards would have improved sharing of answers for within the class questions.

LBP is an effective active learning method which increased students’ satisfaction about physiology learning and improved students’ learning outcome in physiology. LBP achieved some of the objectives of PBL with the minimum resources and it can also be used by educators who want to improve the effectiveness of their lectures in medical schools that use the traditional curriculum.

The use of active student centered learning approaches in medical schools with large number of students should be evaluated by researches and should not be hindered by students’ resistance and complaint as they might not be familiar with these styles of learning and they may not be aware of the long term value of self- directed learning.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Lecture Based Learning

Lectures Based on Problems

Problem Based Learning

Traditional Lectures

Wolff M, Wagner MJ, Poznanski S, Schiller J, Santen S. Not another boring lecture: engaging learners with active learning techniques. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(1):85–93.

Article Google Scholar

Butler JA. Use of teaching methods within the lecture format. Med Teach. 1992;14(1):11–25.

McKeachie W. Learning and cognition in the college classroom. In: Teaching tips: strategies, research and theory for college and university teachers. Lexington: Heath; 1994. p. 279–95.

Google Scholar

Schwartzstein RM, Roberts DH. Saying goodbye to lectures in medical school—paradigm shift or passing fad? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):605–7.

Chilwant K. Comparison of two teaching methods, structured interactive lectures and conventional lectures. Biomed Res. 2012;23(3):363–6.

Belfield C, Thomas H, Bullock A, Eynon R, Wall D. Measuring effectiveness for best evidence medical education: a discussion. Med Teach. 2001;23(2):164–70.

Devlin M, Samarawickrema G. The criteria of effective teaching in a changing higher education context. High Educ Res Dev. 2010;29(2):111–24.

Young S, Shaw DG. Profiles of effective college and university teachers. J High Educ. 1999;70(6):670–86.

Watkins C, Lodge C, Whalley C, Wagner P, Carnell E. Effective learning. London: Institute of Education, University of London; 2002. Available from: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10002819 . Cited 2019 May 25

Ebert-May D, Brewer C, Allred S. Innovation in large lectures: teaching for active learning. Bioscience. 1997;47(9):601–7.

Fyrenius A, Bergdahl B, Silén C. Lectures in problem-based learning—why, when and how? An example of interactive lecturing that stimulates meaningful learning. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):61–5.

Powell K. Spare me the lecture. Nature. 2003;425:234–6.

Carvalho H, West CA. Voluntary participation in an active learning exercise leads to a better understanding of physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2011;35(1):53–8.

Zakaryan V, Bliss R, Sarvazyan N. Non-trivial pursuit of physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2005;29(1):11–4.

Samuelson DB, Divaris K, De Kok IJ. Benefits of case-based versus traditional lecture-based instruction in a preclinical removable prosthodontics course. J Dent Educ. 2017;81(4):387–94.

Remington TL, Bleske BE, Bartholomew T, Dorsch MP, Guthrie SK, Klein KC, et al. Qualitative analysis of student perceptions comparing team-based learning and traditional lecture in a Pharmacotherapeutics course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(3):55.

Joshi KP, Padugupati S, Robins M. Assessment of educational outcomes of small group discussion versus traditional lecture format among undergraduate medical students. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2018;5(7):2766–9.

Newble D, Entwistle N. Learning styles and approaches: implications for medical education. Med Educ. 1986;20(3):162–75.

Samarakoon L, Fernando T, Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S. Learning styles and approaches to learning among medical undergraduates and postgraduates. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):42.

Abraham R, Vinod P, Kamath M, Asha K, Ramnarayan K. Learning approaches of undergraduate medical students to physiology in a non-PBL-and partially PBL-oriented curriculum. Adv Physiol Educ. 2008;32(1):35–7.

Kermaniyan F, Mehdizadeh M, Iravani S, MArkazi Moghadam N, Shayan S. Comparing lecture and problem-based learning methods in teaching limb anatomy to first year medical students. Iranian J Med Educ. 2008;7(2):379–88.

Enarson C, Cariaga-Lo L. Influence of curriculum type on student performance in the United States medical licensing examination step 1 and step 2 exams: problem-based learning vs. lecture-based curriculum. Med Educ. 2001;35(11):1050–5.

Henderson S, Kinahan M, Rossiter E. Problem-based learning as an authentic assessment method. PG diploma in practitioner research projects. Dublin: DIT; 2018. https://arrow.dit.ie/ltcpgdprp/17/ .

Abdelkarim A. Advantages and disadvantages of problem-based learning from the professional perspective of medical and dental faculty. EC Dent Sci. 2018;17:1073–9.

Silén C. Responsibility and independence in learning–what is the role of the educators and the framework of the educational programme. In: Improving student learning: improving student learning–theory, research and practice (Oxford, the Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development); 2003. p. 249–62.

Preszler RW, Dawe A, Shuster CB, Shuster M. Assessment of the effects of student response systems on student learning and attitudes over a broad range of biology courses. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2007;6(1):29–41.

Armbruster P, Patel M, Johnson E, Weiss M. Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2009;8(3):203–13.

Larsen DP, Butler AC, Roediger HL III. Test-enhanced learning in medical education. Med Educ. 2008;42(10):959–66.

Roediger HL III, Karpicke JD. The power of testing memory: basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2006;1(3):181–210.

Smith MK, Wood WB, Adams WK, Wieman C, Knight JK, Guild N, et al. Why peer discussion improves student performance on in-class concept questions. Science. 2009;323(5910):122–4.

Butler AC, Roediger HL. Feedback enhances the positive effects and reduces the negative effects of multiple-choice testing. Mem Cogn. 2008;36(3):604–16.

Horne A, Rosdahl J. Teaching clinical ophthalmology: medical student feedback on team case-based versus lecture format. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(2):329–32.

Patel VL, Evans D, Kaufman D. Reasoning strategies and the use of biomedical knowledge by medical students. Med Educ. 1990;24(2):129–36.

Patel VL, Groen G, Scott H. Biomedical knowledge in explanations of clinical problems by medical students. Med Educ. 1988;22(5):398–406.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff members of the Physiology Department of Faculty of Medicine University of Science and Technology, for their assistance throughout this study and all the students who took part in this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan

Nouralsalhin Abdalhamid Alaagib & Amal Mahmoud Saeed

Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, The National Ribat University, Khartoum, Sudan

Omer Abdelaziz Musa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The lectures for students were performed by NA and OM. NA collected the data, did statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. OM formulated the research idea and critically edited the draft of the paper. AS supervised the whole work and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nouralsalhin Abdalhamid Alaagib .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Faculty of Medicine University of Khartoum reference NO: Ref: FM/DO/EC. All participants signed a written informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Alaagib, N.A., Musa, O.A. & Saeed, A.M. Comparison of the effectiveness of lectures based on problems and traditional lectures in physiology teaching in Sudan. BMC Med Educ 19 , 365 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1799-0

Download citation

Received : 01 April 2019

Accepted : 09 September 2019

Published : 23 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1799-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Traditional lectures

- Lectures based on problems

- Active learning

- Medical education

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Public Education about Cancer pp 68–99 Cite as

Health Education: Some Principles and Practice

Committee on public education of the commission on cancer control.

- Conference paper

38 Accesses

Part of the book series: UICC Monograph Series ((UICC,volume 5))

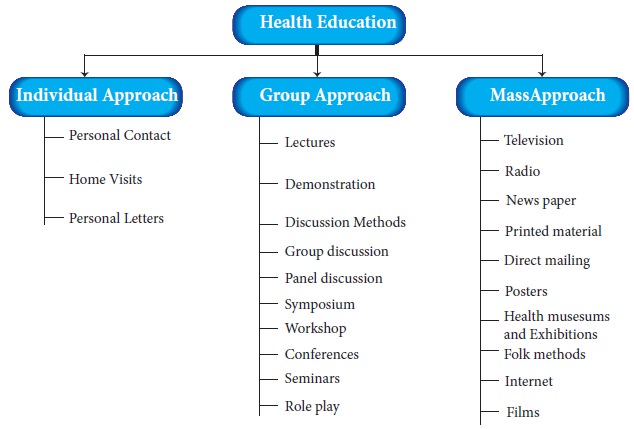

For a comprehensive yet manageable review of the principles of health education, as derived from behavioural studies, we can do no better than refer the reader to Section III of Health Education Monographs , Supplement No. 1, published by S. O. P. H. E. 1 This excellent work reviews the “Methods and Materials in Health Education (Communication)” with separate sections on: (a) fear — arousing communications; (b) pretesting and readability; (c) audio-visual methods and materials (d) group techniques, and (e) the comparative effectiveness of different methods. Perhaps even more important than the section on methods and materials is Section IV of the Monograph dealing with programme planning and evaluation. We have not repeated references included in the S.O.P.H.E. review .

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

References: Principles of health education

Aitken-Swan , J. , and Paterson , R. (1959). Assessment of the resuts of five years of cancer education. Brit. med. J . i , 708. The assessment of five years of cancer education showed that the number of patients with breast cancer who delayed more than one month decreased. No such decrease was noted in a control area, nor did the delay for cancer of the cervix uteri decline. There was an increase in the experimental area of those with breast and cervix uteri cancer who presented themselves when the growths were of limited extent. Finally, from an interview inquiry it was found that the campaign made more impact on those with breast cancer than with cancer of the cervix uteri. One third of the patients in contact with the campaign were too afraid to act upon the advice given. Talks were more influential than articles, but reached a smaller public.

Article Google Scholar

Baric , L. , and Wakefield , J. (1965). A reappraisal of cancer education. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 8 , 78. After reviewing the present scientific knowledge, the authors make a clear case for the role of education in cancer prevention, and pinpoint five areas where further testing and evaluation are urgently needed.

Google Scholar

Bharara , S. S. (1963). Joining science and tradition. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 6 , 106.

Biocca , S. M. , and Joly , D. (1960). Fighting cancer in Argentina. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 3 , 174. To succeed in the battle against cancer it is necessary to have available: (1) a qualified medical staff, able to make an accurate diagnosis; (2) a well-informed population, aware of the importance of early diagnosis; (3) a medical network that provides the essential facilities for such a diagnosis. The authors describe a campaign carried out in Argentina.

Blokhin , N. N. (Ed.) (1962). Methodological Handbook of anti-cancer propaganda . Moscow: Institute of Health Education (Russian Text). This book contains articles on aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis. It also deals directly with cancer education in two chapters and four appendices.

Bogolepova , L. (1962). The people’s health culture. Proceedings of the Internat. Conf. on Health and Health Education , vol. 5 , p. 520. Geneva: Int. J. Hlth Educ. (French text, English and Spanish Summaries).

Bond , B. W. (1958). A study in health education methods. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 1 , 41. This study compared the effectiveness of the two methods of education, namely group-discussion plus decision and a straightforward lecture, in a health education programme concerned with breast cancer. (See page 52, col. 1 of this monograph.)

Brotherston , J. (1963). Aimless benevolence. .. . a box of tricks. .. . or? Int. J. Hlth Educ . 6 , 158. In a compact but pertinent article the author considers the aims and methods of health education. The objectives are both particular and general. “The real difficulty is not to find good deeds to do, but to know where, when and with what to begin”. The author is in favour of tackling the “more circumscribed but necessary area [of] the quality and efficiency of the communication between the health worker and his patient or client”. He condemns the authoritarian attitude of nurse and doctor; they must be made to realise the need to educate — the rest will follow. With respect to the behavioural sciences, “the need now is for a statement of applied social science carefully related to the needs of health practitioners.” Training is a cornerstone to progress, and a scientific approach to the choice of objectives is required.

Burton , J. (1964). Three uses of health education in clinical preventive and public health practice. II. The role of education in cancer prevention. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 7 , 68. This is a background paper prepared by the author for the Who expert committee responsible for the technical report from which we have quoted extensively in the text of this chapter. The author’s paper is used almost in its entirety for the sections on health education within the technical report.

Cameron , C. S. (1956). The truth about cancer , New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc., A thoughtful round up of information about cancer and its control by the then medical director of the American Cancer Society. A vigorous expression of an aggressive philosophy of public education in cancer with emphasis on the concept that “only when everyone recognizes and accepts the importance of personal responsibility will the control of cancer become a living reality.” The book has been brought up to date by the author and will be reissued by Collier Books (paperback) in 1966.

Clemmesen , J. , and Stancke , B. (1965). The effect of a cancer campaign in Denmark. S. A f r. Cancer Bull . 9 , 100. Analysis of the long-term effects of an educational campaign for breast self-examination conducted between 1951 and 1955. The years of the campaign saw more cases, and more of them suited to treatment, than previous years. An improvement in survival was observed over the subsequent 9-year follow-up.

Costalat , P. (1958). Survey on Health Attitudes. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 1 , 207. The inquiry proved that the health assumptions of the young Moroccan women interviewed fitted in neither with modern concepts nor with the former popular traditions. They generally combine both, with resulting incoherence and a stagnant health behaviour. Group education is the best method in these circumstances to crystallize the information spread by mass media. Simultaneous education of parents and children is needed. The author stresses the value of interviews, and the value of sometimes appealing to ideas already accepted by some numbers of the group or basing arguments on a related subject.

Derryberry , M. (1958). Some Problems Faced in Educating for Health. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 1 , 178. Why are people so willing to take chances with their health? There is evidence of an educational need to help people relate in a more positive way to their doctors. The “teachable moment” was immediately after the condition was diagnosed: information was sought from many sources at this point, and this, as well as misinformation, was exchanged. We must prepare people to react intelligently and healthfully when they or their relatives and friends are sick; we must help people find the information they want from a reliable source. There are many examples of the risks people take with their health, why do they do so? The author takes smoking as an example of this and considers it in terms of habit formation and society. There is need for more than a statistical demonstration; the chance element is not referred to self, the emotional, irrational elements weigh strongly against the intellectual, rational arguments. We do not know nearly enough about the factors involved. There is a need for research into methods, and careful planning.

Derryberry , M. (1960). Research: Retrospective and Perspective. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 3 , 164. The primary goal of health education is to increase people’s knowledge of the scientific facts about health and to stimulate them to apply the knowledge in improved health practices. Research in health education is concerned with the process by which people change their health behavior. It includes study of all the various factors in the process and the dynamics of the relationship between these factors..... The importance of knowledge, .... of social factors; .... individual factors. It is also concerned with the character of the action that is being advocated. We need to learn what educational methods work with what kinds of people to produce what kinds of actions. It is in the dynamics of these interrelationships that much intensive work is needed. We must not mistake effort for accomplishment: evaluation is essential both in pretesting and in objective evidence of the increased information and for performance of the recommended action.

Derrberry , M. (1960). Health education — its objectives and methods. Hlth Education Monographs No 8 . The author draws an analogy between health education and medicine in their diagnostic and therapeutic processes. He further considers health education as involving forces which must be analysed, a thorough consideration being given to existing “knowledge, attitudes, goals, perceptions, social status, power structure, cultural traditions and other aspects of whatever public is to be reached. Only in terms of these elements can a successful program be built”.

Donaldson , M. (1962). The cancer riddle: a message of hope . London: Arthur Barker. A broad presentation of information about cancer and its treatment for the general public. It includes a discussion (Chapter 18) of the role of “cancer education among the public”. Dr. Donaldson’s ardent advocacy of public education in Britain began in the early 1930s, when his views received little or no support from professional colleagues. Such programmes as exist in Britain today stem from Donaldson’s pioneer work. A number of his articles are listed in other sections.

Ennes , H. (1958). Teachable Moments. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 1 , 70. The educational component of health activity, although continous, may vary in intensity, as, for example, in emergencies. At such moments people are potentially more amenable to education. “Our experience in 1957–58 with the influenza outbreak indicates to us that a specific health threat increases public receptivity to information, and facilitates programs of action for improving general health behavior as well as protection against the present danger.”

Erdmann , Fr . (1960). Öffentliche Krebsaufklärung als Mittel zur Prophylaxe. [Inf ormation on Cancer as a Prophylactic Means in the Fight against Cancer]. Krebsarzt 15 , 240. The author describes the educational aims and methods of his department for “inf ormation on cancer and advanced training in oncology”.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Hammond , E. C . (1959). Cancer education for the public in the U. S. A. In: Cancer , vol. 3 , ed. by R. W. Raven. London: Butterworth & Co. (Publ.) Ltd.

Hochbaum , G. M. (1959) Some implications of theories of communication to health education practice . Paper presented at the Seminar on Communication in Public Health Education Practice, School of Public Health and Center for Continuation Study, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 1959 (Mimeo). In this excellent paper the author deals with “ some practical implications of some of the principles of effective communication”. He begins by considering the meaning of “communication”, which can be looked on as having three levels, depending on its purpose — the mere communication of information, the performance of some fairly immediate and specific action, and, thirdly, the more fundamental change of the communicant’s attitudes, beliefs, and motivational patterns leading eventually to behavioural changes. Of fundamental importance is the subjective meaning of a message and how it fits into the already existing frame-work of a person’s attitudes, interests and needs; information may be necessary in bringing about rational behaviour, but it is not usually sufficient by itself. The author continues with a very useful consideration of the timing of a communication and the best use of the “teachable moments”, which are those moments created by certain circumstances (e.g. an epidemic) when there is an increased readiness to learn. Of importance for the continued effect of health communications is the sustaining of the emotional impact not only by correct timing but also by correctly spaced follow-up communications. Action should be provided while motivation is still close to the peak. Motivation is strengthened when an action is carried out freely and for reasons that are perceived by the individual as good and acceptable, especially where such reasons are explicitly stated. These considerations also have implications for the long-term planning and integration of programmes. The author goes on to consider the role of anxiety in health communications, its uses and abuses, and its use in cancer education. An important principle in this connection is that “the anxious person looks for reasurance and not for facts”. The advantages and drawbacks of mass media are critically reviewed. Finally a very useful section considers the relative merits of educating the public to accept broad principles concerning health, and programmes aimed at producing isolated actions.

Hochbaum , G. M. (1960a). Research relating to health education. Hlth Education Monograph No 8 . The author considers his topic in two parts. Firstly, the importance of discovering the attitudes, beliefs, needs, fears etc. of the individuals and social groups, prior to any attempt to influence them educationally: such factors influence what will be accepted or rejected, by whom, and under what circumstances. Having thus considered the “whys” of human behaviour, the author goes on to consider the ways and means of changing it: topics covered include mass media, group dynamics, and the theory of cognitive dissonance.

Hochbaum , G. M. (1960b). Modern Theories of Communication. Children 7 , 13. Based on Hochbaum (1959a).

Hochbaum , G. M. (1960c). Behavior in response to health threats . Paper presented at the 1960 Annual Meeting of the Amer. Psychol. Ass. in Chicago, September 2nd. 1960. (Mimeo). See text of this chapter for summary.

Hochbaum , G. M. (1962). Evaluation: A diagnostic procedure. Proceedings of the Internat. Conf. on Health and Health Education , vol. 5 , 636. Geneva: Int. J Hlth Educ. The author summarizes the critical aspects in the evaluation of health education programmes as:” (1) Decisions on programme goals and methods, and decisions on evaluation techniques should go hand—in— hand. (2) Both the .... goals and the evaluation measures should be concerned with human behaviour. Non-observable aspects of behaviour, such as changes in knowledge and attitudes are only intermediary or substitute criteria. (3) Evaluation should be carried out as a continuous process [i. e. before, during and after the programme]. (4) Evaluation should not be considered as a measure of success, but as a diagnostic procedure that helps to identify effective and ineffective aspects of the programme”. Health education objectives differ from those of a health programme: the former is concerned with the behaviour which is of help in achieving the latter (which are more concerned with medical statistics).

Hochbaum , G. M. (1965). Research to improve health education. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 8 , 141. Insufficient attention is paid to differentiating between the two kinds of research: (1) aimed at improving health education, and (2) aimed mainly at advancing knowledge. The two may differ in objectives, methodology, design, and analysis and treatment of data. Much health educational research fails because it does not adhere to principles of sound scientific research; but much fails because it adheres to them too compulsively, despite the obvious limitations imposed by field conditions. In this case compromise is necessary, but with a clear realization of how compromise will affect the interpretation of data.

Hopper , J. M. H. (1960). The value of various forms of publicity. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 3 , 143. This study supports the view that “the best way of publicising health problems is to use all the forms available, as when the four selected forms of publicity [press, bus posters, hoardings or posters at place of work, and letter to parents of tuberculin positive children] were used, attendance dropped to 88 per cent of the total attendance when the sixteen forms” as used in the 1957 campaign were employed. The results also showed that some forms of publicity attract the attention of far greater numbers of people (the first three mentioned above); prominence should be given to these in future campaigns.

Horn , D. (1956). The attitudes of psychiatrists on the effect of cancer propaganda . Amer. Cancer Soc. (Mimeo). The results of a survey of 387 psychiatrists carried out in 1955 show that since 1949 (when there was also a “deliberate effort .... to de-emphasize the more fear-provoking aspects of cancer and to emphasize a “note of hope. ...”) there has been a significant decrease in the number of psychiatrists that believe American Cancer Society literature has increased anxiety among psychiatric patients (from 35 % to 25 %). Among those believing that there has been an increase in anxiety, there has been a decrease in the number believing that such anxiety results in greater harm than good.

Hyman , H. H. , and Sheatsley , P. B. (1958). Some reasons why information campaigns fail. In: Readings in social psychology , ed. by E. E. Maccoby et al . New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winton.

James , W. (1964). The American Cancer Society’s school education program. J. Sch. Hlth 34 , 466. The ACS public education director outlines concepts in a continuing programme aimed first at school administrators and teachers, to bring cancer instruction to students (down to Junior high school) “while they are in an active learning situation and before they have developed obstructive fears and misconceptions”.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Johns , E. (1962). The Los Angeles evaluative study. Proceedings of the International Conference on Health and Health Education , vol. 5 , 514. Geneva: Int. J. Hlth Educ. This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of school health education. The effectiveness of health education was judged by means of an appraisal of the programme activities and the health behaviour of pupils in terms of knowledge, attitudes and practices.

Katsunuma , H. (1958). Before planning: a survey. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 1 , 151. To help determine the best health education approach in a rural community, a survey on family attitudes regarding health problems was recently undertaken in a district near Tokyo.

King , S. H. (1958). What we can learn from the behavioural sciences. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 1 , 194. The author stresses the importance of familiarity with the major concepts of the behavioural sciences, and their integration across the biological, psychological and social-cultural levels. “They [public health workers] also need to be introduced to the findings of research projects that are pertinent to an understanding of disease and of social factors that inhibit or facilitate health programmes.” The major concepts considered are: social perception or definition of the situation, homeostasis or a striving towards a balance, beliefs and attitudes, and political structures and communication lines.

Knutson , A. L . (1952a). Evaluating health education. Publ. Hlth Rep . 67 , 73. In the evaluation of any health education programme one should consider the following points: adequate preliminary investigation should be made to ascertain needs and behaviour; goals must be specified, but evaluated in relation to the overall aims; concrete evidence that an objective has been achieved is the only realistic criterion for measuring effectiveness; methods of evaluation must be chosen in terms of the specific goals; a baseline of zero cannot be presumed; evaluative measurements are nearly always indirect measures; long-term needs should be borne in mind apart from the immediate goals.

Knutson , A. L . (1952b). Pretesting: A positive approach to evaluation. Publ. Hlth Rep . 67 , 699. A critical review should be made prior to pretesting a programme so that the needs, objectives, methods, and subject matter are clearly defined, accurate and likely to be most successful. The pretest should be planned in terms of certain specific conditions that need to be satisfied in order to achieve programme goals; the programme will then be more likely to succeed. The conditions to be satisfied include: amount of public exposure, attention and interest, motivation, pattern of behaviour, comprehension, understanding of purpose, learning and retention.

Knutson , A. L. , Shimberg , B. , Harris , J. S. , and Derryberry , M. (1952). Pretesting and evaluating health education. Publ. Hlth Monograph No 8 . Washington, D. C.: United States Public Health Service Publication No 212 .

Koch , F. , and Stakemann , G. (1964). A population screening for carcinoma of the uterus with the irrigation smear technique. Dan. med. Bull . 11 , 209. A remarkable project in the borough of Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, appears to demonstrate the acceptability of self-obtained smears (by pipette) without major educational effort. Of 11,192 selected women, 82.2 % used and returned the pipettes. Propaganda limited to one 3-minute interview on T. V. and a few items in newspapers. The authors suggest this success is due to the fact that women can undertake the procedure in the privacy of their homes, and without the inconvenience or embarrassment of making an appointment for examination.

La Pointe , J. L. , Wittkower , E. D. , and Lougheed , M. N. (1959). Psychiatric evaluation of the effect of cancer education on the lay public. Cancer (Philad.) 12 , 1200. The authors believe that cancer education and many other forms of health education have relatively little effect considering the amounts of time, money and skill spent on them. There is a reliance on the mass media, merely presenting material to large groups of individuals regardless of their receptivity. A more personal approach through discussion groups and the like may produce a lessening of resistances and thus reduce the blocking reactions. Once the general public has allowed itself to be exposed to education, greater resistances might be overcome if other factors, such as the different needs of the population, or which person is more liable to be heard and understood in specific groups, were known. “The real problem is not whether enough information is put across to the general public, but how and how successfully the information is communicated. There is little doubt in our minds, for instance, that propaganda based on curability through early treatment is more likely to be successful than is propaganda based on fear.”

Lifson , S. S . (1958). Do they understand what they read? Int. J. Hlth Educ . 1 , 100. Giving literature to patients in hospitals is not enough. We must find out if they understand what they read. An interesting survey was carried out in this connection by the U. S. Tuberculosis Association, making use of reading tests. It proved two things: the need for hospital personnel to be aware of the level of vocabulary comprehension of their patients; and, secondly, that we should not rely mainly on the printed word for our educational effort.

McCormick , G. (1964). Programme planning — An organized approach. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 7 , 91. The author discusses how he used the W. H. O. guide to programme — planning when he was co-ordinator of a community nursing-home demonstration programme. The W. H. O. guide enumerated the following five steps:(1) collecting information essential for planning; (2) establishment of objectives; (3) assessing the barriers to health education and how they may be overcome; (4) appraising apparent and potential resources (organisations, personnel, materials and funds); (5) developing the detailed educational plan of operations (including a definite mechanism for continuous evaluation).

Maclaine , A. G. (1965). Lay education in cancer control. Med. J. Aust . 2 , 171. A succinct review of experience elsewhere and discussion of possible applications to the situation in Australia. This article is not written from a limited parochial point of view, and its interest is therefore not confined to the country of origin.

McNickle , d’ A. , and Pfrommer , V. G. (1959). It takes two to communicate. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 2 , 136.

Nix , M. E. (1961). Health education and human motivation. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 4 , 192. Although the importance of health and illness has global significance, attitudes regarding these will vary according to the cultural ideals of a community. Therefore, although the problem of the control of tuberculosis is universal, it can be solved by giving careful consideration to the fixed customs of the group. The author considers the different types of atmosphere of a group associated with the types of leadership, and the consequences for human motivation and behaviour. If the leader is authoritarian or laissez—faire the positive results, if any, are unlikely to be permanent. Ideally the relationship should be one of educated self-determination, in which a person follows a responsible leader with understanding and the realization that the programme will benefit him and those around him.

Osborn , G. R. , and Leyshon , V. N. (1966). Domiciliary testing of cervical smears by home nurses. Lancet 1 , 256.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Public health nurses in Derby were used in a cervical cytology programme (a) to identify the high-risk women (multiparous, low on socio-economic scale) in their care; (b) to persuade them to have a smear taken; (c) to take smears (after careful training) in the home. The value of this highly personal form of selective health education was shown by results. Moreover, a positive smear rate of 26.5 per 1000 was found in this group, almost four times greater than the rate recorded for the general population at clinics in the same town.

Paterson , R. , and Aitken-Swan , J . (1954). Public opinion on cancer: A survey among women in the Manchester area. Lancet ii , 857. A report of the first survey carried out at the beginning of the experimental cancer education programme by the Manchester Committee on Cancer. (See Chapter I of this Monograph).

Paterson , R. , and Aitken-Swan , J. (1958). Public opinion on cancer: Changes following five years of cancer education. Lancet ii . 791. This is a repeat survey of the one carried out in 1953 (Paterson and Aitken-Swan 1954) and showed a good general improvement in attitudes to cancer. (See Chapter I of this Monograph).

Paterson , R. , Brown , C. M. , and Wakefield , J. (1954). An experiment in cancer education. Brit. med. J . ii , 1219. This is an early article describing the cancer education programme of the Manchester Committee on Cancer.

Phillips , A. J . (1955). Public opinion on cancer in Canada. Canad. med. Ass. J . 73 , 639. (See Chapter I of this report).

Phillips , A. J. , and Taylor , R. M. (1961). Public opinion on cancer in Canada; a second survey. Canad. med. Ass. J . 84 , 142. This is a report on a repeat of the 1955 survey (Phillips 1955), and shows an improvement in public opinion concerning cancer after a carefully planned educational campaign. (See Chapter I of this report).

Popma , A. M. (1962). Public education and cancer control. Acta Uni. int. Cancr . 18 , 723. The author deals with the history of public cancer education both in the United States and Great Britain. Fear of cancer needs to be eradicated by education organised by the medical profession. Much evidence is cited to show the value of early diagnosis of cancer of all sites, especially asymptomatic cancer. Cancerophobia, the most common objection to education, is not a true problem. It should be guided by education into a salutary fear of undue delay in seeking adequate treatment.

Price-Williams , D. R. (1962). New attitudes emerge from the old. Proceedings of the International Conference on Health and Health Education , vol. 5 , 554. Geneva: International Journal of Health Education. The author emphasizes the importance of taking into account the background of ideas and practices in health education. New ideas must be seen in relation to the old ones that they are disrupting or replacing. The author illustrates his points with examples from a tribe he studied in Nigeria.

Rankin , D. W. , and Brown , A. J . (1964). Cancer education in Victoria. Med. J. Aust . 1 , 357. A description of five years of intensive cancer education of the public by the Anti-cancer Council of Australia, its organization objectives, methods and evaluation.

Raven , R. W. , (1953). Cancer and the community. Brit. med. J . ii , 850. Among other topics, he discusses a cancer education programme. Telling the public the symptons is not enough, they must also be told how to act in certain circumstances, and what can be done to help them. This must be done wisely and in stages throughout the country.

Read , C. R. (1965). The control of neoplasia — education for prevention. In: The social responsibility of gynecology and obstetrics . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. The American Cancer Society’s vice president for public education and information reviews his and the Society’s experience in many years of education against cancer of the uterus. He emphasizes the need for physician leadership, the importance of terminology acceptable to the media and meaningful to the public, the need to use both media and person-to-person approaches through informal networks of communication, (churches, unions, women’s clubs, neighbourhoods, etc.), the educational stress on “hope, on the peace of mind the Pap test can give”. Many millions in America have learned a new health habit, but there has been too little success with low-income groups and women over the age of 65. The diffusion process in health education is slow.

Roberts , B. J. (1965). A framework for consideration of forces in achieving earliness of treatment. Hlth Education Monographs No 19 . A stimulating analysis of the motivational and other forces involved in achieving early detection and treatment, particularly of breast cancer, by health educational methods. Invaluable because it offers for the first time a holistic view of the decision-making forces that lead to action, rather than the usual fragmentary examination of some aspects of the problem.

Roberts , B. J. (1962). Concepts and methods of evaluation in health education. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 5 , 52. In this article the author attempts to clarify the concepts surrounding evaluation in health education, and considers the problems of measurement involved in such evaluation.

Rosenstock , I. M. , Hochbaum , G. M. , and Kegeles , S. S. (1960). Determinants of health behavior . Golden Anniversary White House Conference on Children and Youth. See the text of this chapter for a summary.

Rosenstock , I. M. (1960). Gaps and potentials in health education research. Hlth Education Monographs No 8 . The author considers that applied research is needed to “develop simple, economical and valid methods for diagnosing health education problems; [and also] ... to develop valid methods for educating individuals and groups in a real life health setting”. Further “basic research is needed to increase our growing knowledge of why people do what they do”. Finally, much more programme evaluation is required to help in improving programmes.

Rosenstock , I. M. (1961). Decisionmaking by individuals. Hlth Education Monographs No 11 . See the text of this chapter for summary.

Rosenstock , I. M. (1962). Many opinnions.. . Few Hard Facts. Proceedings of the International Conference on Health and Health Education , vol. 5 , 565. Geneva: Int. J. Hlth Educ. The author is of the opinion that “what we still do not know .... is how best to diagnose and use existing motivational states and existing social structures to change behaviour”.

Rosenstock , I. M. (1963). Public response to cancer screening and detection programs. J. chron. Dis . 16 , 407. In the second part of the paper, Rosenstock attempts to apply the behavioural model already developed (see text of chapter) to cancer detection. The research that is required should be directed at the groups shown to be in need of it by a consideration of their health behaviour status — e. g. the undermotivated. The author concludes with recommendations for (a) a fact-finding phase; and (b) an action phase.

Ross , W. S. (1965). The climate is hope — How they triumphed over cancer , New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc. The book reports the personal attitudes to cancer of physicians, their patients, most of whom have been cured, and researchers. Sixteen rambling chapters — largely taped interviews — reflect the fears and guilt of some patients, the courage of others. Physicians speak candidly of their limitations as well as their successes: one is deeply interested in problems of stress and cancer, another in the value of a cancer detection examination, a third in the philosophy of radical operations, a fourth in the unbearable family tensions that often develop when a child has cancer. “Cancer is a highly complex group of diseases, each with its own course and prognosis ... Hence the reactions and the judgements of both patients and therapists often vary greatly and may be controversial.”

Sandman , I. (1962). Parent education in the U. S. A: Some impressions on methods. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 5 , 34. The author examined whether group discussions would produce better results than the traditional courses in health education of expectant mothers. The answer appears to be in the affirmative. Although factual information is important, an understanding of one’s feelings is also important and both are achieved in discussions.

Seppilli , A. (1962). A community survey — First step towards a film. Proceedings of the International Conference on Health and Health Education , vol. 5 , 527. Geneva: Int. J. Hlth Education. (French text, English and Spanish Summaries).

Spillius , J. (1962). The impact of social structure. Proceedings of the International Conference on Health and Health Education , vol. 5 , 560. Geneva: Int. J. Hlth Educ. The author suggests “(1) that the health educator may have to redefine the kind of system he is dealing with; (2) that a health education programme may constitute a direct attack on some of the individuals in the community, especially those who hold some kind of medical lore; (3) that it is necessary to study the customary ways of imparting information, recognizing that there may be an informal [social] structure, such as a network of kin which is just as potent as the formal structure in imparting information and shaping opinion; (4) that it is necessary to make a distinction between decision-making and choices ...,(5) that cultures change, customs change, and in some societies at a more rapid rate than in others .... it should [therefore] be possible to change ideas on health and disease if we analyse the social patterns, see who is responsible for health practices, and whether or not the community’s ideas are really as irrational as they appear. In attempting to promote change, we should obviously use the existing social structure as much as possible”. Society should not be looked at in terms of social structure alone; health education programmes affect the social, economic and technological structures, and these three aspects must be included in the planning and execution of the programme. The physical and economic burden placed on the people of a developing country must be borne in mind in any health education programme.

Steuart , G. (1965). The physician and health education. Brit. med. J . ii , 590. The author considers that the passive role of the patient is not conducive to good health education via the doctor, and recommends that the relationship be changed to a more patient-oriented one, in which the latter plays an active part. Steuart deals with the reasons why a patient should be educated, possible objections to his proposals, and the part played in all this by basic medical education of the doctor.

Steuart , G. (1959). The importance of programme planning. Int. J. Hlth Educ . 2 , 94. Systematic and intelligent planning are essential for successful health education. (See text of this chapter). Illustrations are taken from a programme concerning ante-natal and maternity care in a South African Indian community.

Steuart , G. (1962). A slender store of studies.. . Proceedings of the International Conference on Health andHealth Education , vol. 5 , 608. Geneva: Int. J. Hlth Educ. In this very instructive article the author reviews the studies of the educational content of health education programmes. Such studies are concerned with evaluation of the effectiveness of programmes, the existence and extent of the problem in the community or group, the establishment of criteria or baselines against which to measure and compare results, the comparative effectiveness of methods and the use of methods appropriate to the population and problem. More such studies are needed, and the help of the pure scientist must be used wherever possible. This article includes a bibliography of nearly fifty articles.