How to Memorize Verbatim Text

This page discusses some common memory techniques for memorizing text word-for-word (verbatim).

Views on Verbatim Memorization

The ancient mnemonists (like Quintilian ) distinguished between memoria rerum (memory for things) and memoria verborum (memory for exact words). The conclusion back then, and now, is that memoria verborum is much more difficult than memoria rerum :

‘Things’ are thus the subject matter of the speech; ‘words’ are the language in which that subject matter is clothed. Are you aiming at an artificial memory to remind you only of the order of the notions, arguments, ‘things’ of your speech? Or do you aim at memorising every single word in it in the right order? The first kind of artificial memory is memoria rerum ; the second kind is memoria verborum . The ideal, as defined by Cicero in the above passage, would be to have a ‘firm perception in the soul’ of both things and words. But ‘memory for words’ is much harder than ‘memory for things’; the weaker brethren among the author of Ad Herennium’s rhetoric students evidently rather jibbed at memorising an image for every single word, and even Cicero himself, as we shall see later, allowed that ‘memory for things’ was enough. [ The Art of Memory by Frances Yates]

Before deciding to memorize every word, consider whether you really need to know every word or just the concepts in the book. For example, if you are trying to learn a text book, or even a speech or presentation that you have written yourself, you don’t probably need to try to memorize every word.

If you want to memorize verbatim text, you should familiarize yourself with basic mnemonics , mnemonic images and the memory palace technique .

Additional Resources

Here are some forum threads and other pages on this topic:

- How to Memorize a Book

- Lanier Verbatim Memory System

- Verbatim App: Memorizing texts word-for-word

- How & How Much

- Working on a system to memorize text verbatim

- Need Ideas for a System to Memorize Scripture

- Memorizing the Bible

- Bible Scripture Verbatim Process and My Visual Alphabet Simple Application

- What have you achieved using mnemonics?

- Seeking adivces on Memorising Prufrock by T. S. Eliot

- Revelation 20

- What to do when you’re stuck on a word/phrase?

Feedback and Comments

What did you think about this article? Do you have any questions, or is there anything that could be improved? We would love to hear from you! You can leave a comment after clicking on a face below.

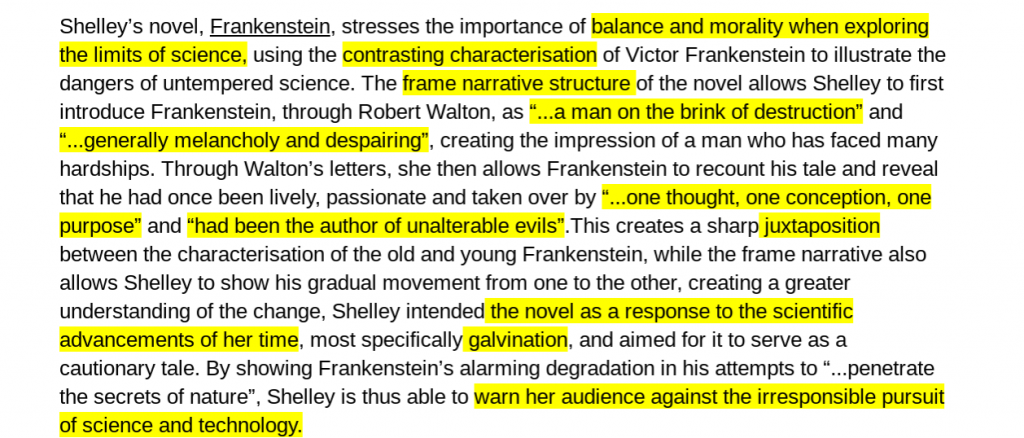

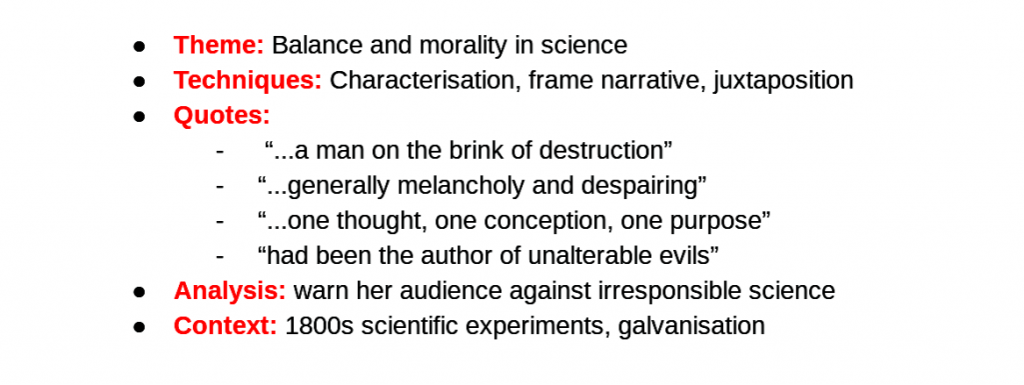

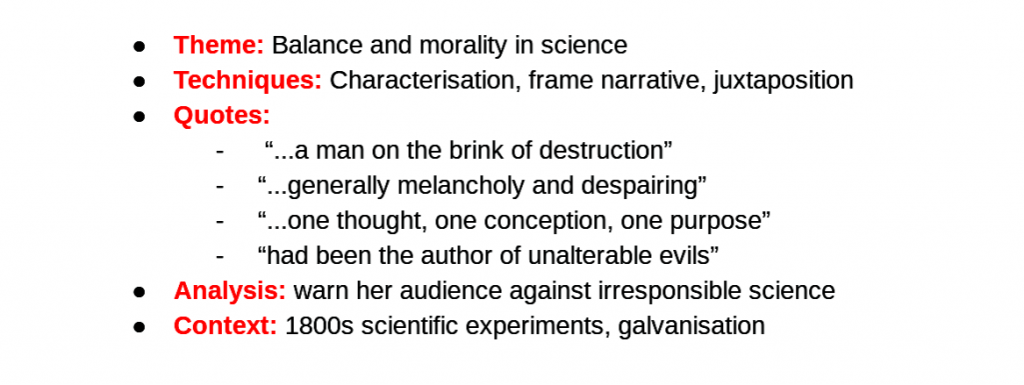

How to memorise essays and long responses

Lauren Condon

Marketing Specialist at Atomi

When it comes to memorising essays or long responses for your exams, there are three big things to consider.

- Should you even try to memorise an essay?

- Do you know how to adapt your memorised response to the exam question?

- How on earth are you meant to memorise a 1,200 word essay??

It’s a lot to weigh up but we can help you out here. If you want an answer to the first question, here’s one we prepared earlier. But wait, there’s more! If you’re super keen to read more about question #2, then go ahead and click here .

And for that third point on how to actually memorise a long essay? Well, all you have to do is keep reading...

1. Break it down

Your essay/long response/creative writing piece could be anywhere between 800 and 1,200 words long. Yeah… that’s a lot. So when it comes to memorising the whole thing, it’s a lot easier to break the answer down into logical chunks and work on memorising it bit by bit.

So if you want to memorise your Discovery Essay, you might have something like this:

- Introduction

- Theme 1 with the assigned text

- Theme 1 with the related text

- Theme 2 with the assigned text

- Theme 2 with the related text

You’re going to want to memorise the paragraphs and pay attention to the structure then you can piece it all together in the exam. Having a killer structure makes it a lot easier to remember the overall bones of this situation and if you’re finding this effective, you can even break those body paragraphs down further like topic sentence > example > explanation > connection to thesis.

2. Use memory tricks

Now, there are lots of different strategies and approaches when it comes to memorising a long piece of writing. Moving in sections, you can try reading it out loud over again (slowly looking at the paper less and less) or the classic look-cover-write-check approach. If you’re really struggling, make some of your own flashcards that have the first sentence on one side and the next sentence on the back so you can test your progress.

You could also enlist the help of some creative mnemonics (memory tricks) to remind you which sentence or section needs to come next. Pick one keyword from each sentence in the paragraph and turn them into a silly sentence to help you remember the structure of the paragraph and to make sure you don’t forget one of your awesome points.

3. Play to your strengths

Not all of us are super geniuses that can just read an essay and then memorise the entire thing but we’re all going to have our own strengths. There’s going to be something whether it’s art, music, writing, performance or sport that just ‘clicks’ in your brain and this is what you want to capitalise on. So for me, I was really into debating and public speaking (hold back the jokes please) and was used to giving speeches and remembering them. So whenever I wanted to memorise a long response, I would write out the essay onto palm cards and then practice it out loud like a speech. Did it annoy my family? Yes. Was I too embarrassed to tell people my strategy? Yes. Did it work? Absolutely. 💯

Whatever your strengths are, find a way to connect them to your essay and come up with a creative way of learning your long response that will be much easier and more effective for you!

4. Start early

So you know how there’s that whole long-term/short-term memory divide? Yeah well that’s going to be pretty relevant when it comes to memorising. You’re going to have a much better chance of remembering your long response if you start early and practice it often, instead of trying to cram it in the night before… sorry.

The good news is, you still have a couple of months before the HSC so try to get your prepared response written, get good feedback from your teachers and then make it perfect so it’s ready to go for the HSC. Then, the next step is to start memorising the essay now and test yourself on it fairly regularly all the way up to your exams. This way, you have plenty of time to really lock it deep into your memory.

5. Test yourself

The final and maybe even most important step is to test yourself. And not with flashcards or the look-cover-check-repeat anymore. Once you’ve got the essay memorised pretty well, you want to spend the weeks coming up to HSC doing past questions so you can practice

- Having the essay memorised

- Being able to recall it under pressure

- Adapting it to any question so that all your hard work will actually pay off

For this to work, you really need to commit 100% to exam conditions (no cheating!) and it’s definitely worth sending those responses to your teacher to get them marked. That way, you will actually know if you’re doing a good job of remembering the core of your argument but also tailoring it perfectly to the question.

Any subject with essays or long responses can be super daunting so if you want to have a pre-written, adaptable response ready to go then it’s worth making sure you can actually memorise it for your exam. Remember to break down the essay into sections, play to your memory strengths and make sure you consistently test yourself all the way up to HSC. That should do the trick. 👌

Published on

July 28, 2017

Recommended reads

Strategies for using retrieval

The syllabus: your key to smashing your studies

Techniques to smash procrastination

What's atomi.

Engaging, curriculum-specific videos and interactive lessons backed by research, so you can study smarter, not harder.

With tens of thousands of practice questions and revision sessions, you won’t just think you’re ready. You’ll know you are!

Study skills strategies and tips, AI-powered revision recommendations and progress insights help you stay on track.

Short, curriculum-specific videos and interactive content that’s easy to understand and backed by the latest research.

Active recall quizzes, topic-based tests and exam practice enable students to build their skills and get immediate feedback.

Our AI understands each student's progress and makes intelligent recommendations based on their strengths and weaknesses.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Erin Wright Writing

Writing-Related Software Tutorials

How to Use Microsoft Word (10 Core Skills for Beginners)

By Erin Wright

Do you want to learn how to use Microsoft Word quickly? This tutorial teaches ten core skills for beginners.

Table of Contents

How to Start a New Document

How to change the font, size, and color, how to change the alignment, line spacing, and indentations, how to add headings, how to change the margins, how to add images, how to add page numbers, how to add headers and footers, how to run the editor (spelling and grammar check), how to save and print your file.

Please note that this is a quick start guide. I have in-depth tutorials for most of these topics for those who would like to learn more.

Watch all the steps shown here in real time!

Explore more than 250 writing-related software tutorials on my YouTube channel .

The images below are from Word for Microsoft 365. These steps are similar in Word 2021, Word 2019, and Word 2016.

We will cover these ten core skills in Word for Mac in a separate tutorial.

- Open Word on your computer.

When Word opens, you will be in the Home screen of the Backstage view.

- Select Blank document to start a new document. (Alternatively, select Open if you want to open an existing Word document.)

When the new document opens, you will be in the Home tab in the ribbon , and your cursor will automatically be placed towards the top, left-hand corner of the page, ready to type.

You can change the font, size, and color before or after you type text. However, if you want to change existing text, first left-click, hold, and drag with your mouse to select the text.

- Select the Home tab in the ribbon if you are not already there (see figure 2).

- Select the menu arrow to open and choose from the (A) Font , (B) Font Size , or (C) Font Color menus in the Font group.

If you selected existing text, that text will change immediately. If you haven’t selected existing text, all new text will feature the choices you just made.

Further Reading: How to Change the Font, Font Size, and Font Color in Microsoft Word

Like the font choices shown above, you can change the alignment, line spacing, and indentations before or after you type text. However, if you want to change existing text, first left-click, hold, and drag with your mouse to select the text.

- Select the Home tab, if you are not already there (see figure 2).

- Select the Align Left , Center , Align Right , or Justify button to position the text on the page.

- Select the Line and Paragraph Spacing menu arrow and then choose a spacing option from the drop-down menu.

- Select the Decrease Indent or Increase Indent buttons to adjust the indent as necessary.

Further Reading: How to Adjust Line Spacing in Microsoft Word and Three Ways to Indent Paragraphs in Microsoft Word

You can turn existing text into a heading or choose a heading level before typing the heading text.

- Select the Home tab if you are not already there (see figure 2).

- Select a heading level from the Styles group.

- If the heading level you want isn’t visible, select the More button.

- Select a heading level from the menu that appears over the Styles group.

Further Reading: How to Create and Customize Headings in Microsoft Word

You can change the page margins for your entire Word document at once.

- Select the Layout tab in the ribbon.

- Select the Margins button and then select an option from the drop-down menu.

Further Reading: How to Adjust the Page Margins in Microsoft Word

- Place your cursor where you want to insert the image.

- Select the Insert tab in the ribbon, select the Pictures button, and then select the location of the image:

- This Device lets you choose an image stored on your computer or network server.

- Stock Images lets you choose stock images, icons, cutout people, stickers, and illustrations. The full stock image library is only available to users signed into Word for Microsoft 365.

- Online Pictures lets you search for images through Bing, Microsoft’s search engine.

For this tutorial, we will insert an image stored on the device.

- (For “This Device” option only) Locate and select the image in the Insert Picture dialog box and then select the Insert button.

Your image should now appear in your Word document.

- (Optional) Select one of the resizing handles and then drag the image to a new size.

- (Optional) Select the Layout Options button and then choose how the image is positioned with the surrounding text:

A. In Line with Text

E. Top and Bottom

F. Behind Text

G. In Front of Text

The effect of each option will depend on the size of your image and the density of your text. So, you may need to experiment with several options to find the one most suited to your content.

Further Reading: How to Insert and Modify Images in Microsoft Word

- Select the Insert tab in the ribbon (see figure 13).

- Select the Page Number button and then select a location from the drop-down menu, followed by a design from the submenu.

- Select the Close button to close the Header and Footer tab. (This tab only appears when the Header and Footers areas are active.)

Further Reading: How to Add Page Numbers in Microsoft Word

- Select the Header or Footer button and then select a design from the drop-down menu.

- Type your text into the placeholders.

- Select the Close button to close the Header and Footer tab (see figure 18).

Further Reading: How to Insert Headers and Footers in Microsoft Word

In Word for Microsoft 365, the spelling and grammar check is called the Editor. Your spelling and grammar options will depend on which version of Word you are using. Therefore, your interface may look different than the images shown below.

- Select the Review tab in the ribbon and then select the Editor button. (Older versions of Word will have a Check Document button, instead.)

- Select the corrections or refinements category you want to review in the Editor pane.

- If Word finds a possible error, select a recommendation or select Ignore Once or Ignore All .

Word will automatically move to the next issue within the category.

- Select a new category or select the closing X to close the Editor.

What Is the Difference between the Editor Button and the Spelling and Grammar Button?

You may notice a Spelling and Grammar button next to the Editor button in the Review tab. This button provides a quick way to check only spelling or spelling and grammar without checking the additional refinements reviewed by the Editor.

Further Reading: How to Use the Editor in Word for Microsoft 365

I recommend saving your file before printing just in case there is a disruption during the printing process.

- Select the File tab in the ribbon.

- Select the Save tab in the Backstage view.

- Select the location where you want to save the File.

- Type a name in the File Name text box and then select the Save button.

- Once you have saved your document to a specific location, you can then select the Save icon if you make changes to the document later.

- To print, reselect the File tab (see figure 26) and then select the Print tab in the Backstage view.

- Ensure the correct printer is selected and turned on, enter the number of copies into the text box, and then select the Print button.

From there, follow any additional dialog boxes provided by your printer.

Updated November 26, 2023

- Microsoft Word Tutorials

- Adobe Acrobat Tutorials

- PowerPoint Tutorials

- Writing Tips

- Editing Tips

- Writing-Related Resources

Essay Memorization Techniques

Linda basilicato.

To memorize an essay or prepare for an essay exam, avoid trying to memorize your practice essay word for word. Instead, memorize key points and put trust in your ability to put together an essay based on those key ideas. Try not to get attached to pretty or well-put sentences written beforehand. This will only occupy valuable mental space needed for the exam. Remember, for an essay test you are graded mostly on content, not eloquence. Papers are the proper outlet for eloquence.

Explore this article

- Write by Hand

- Use Your Own Words

- Know Your Learning Style

Just because you're not going to memorize and regurgitate your practice essay verbatim for the test doesn't mean you shouldn't write it many times. But do try to write from memory. Don't mindlessly copy words from a page. Keep your notes nearby, but use them less and less each time you sit down to write. Again, don't try to memorize exact sentences, just get all the important information down on paper.

2 Write by Hand

If you're going to have to write the essay by hand, practice by hand, at least some of the time. But don't start out the test with your hand already cramped and sore.

After you've written the practice essay you hope to memorize, write a simple outline for it. Use mnemonics to help memorize the outline. Mnemonics are simple memory tricks such as PEMDAS (or Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally), a common memorization technique used by math teachers to help students learn the order of operations (Parentheses, exponents, multiplication and division, addition and subtraction). Other mnemonic devices involve songs, rhymes and silly, simple stories used to string together the basic information you need to remember.

Memorize this outline and write it down as soon as you sit down to take the exam. Then use it as you used your notes during your earlier practice and study sessions.

4 Use Your Own Words

You may wish to memorize a key quote or two, but most of the information should be expressed in your own words. Remember you will most likely be graded on content and by the pieces of information included (or excluded) from your essay. Take the time to really understand concepts that are tricky for you. Come up with illustrative analogies to explain a concept simply and to show that you really understand it.

5 Know Your Learning Style

If you're more of a talker than a writer, use this skill to your advantage. Instead of writing over and over again, simply explain out loud the answer to each question to prove you really understand it. But don't do this exclusively. For every two to four times you explain your answer in speech, write your answer down on paper. Written words are very different from spoken explanation. You will most likely need the written practice to succeed on an essay exam. Don't make the mistake of thinking you will know how to write an essay because you can explain it out loud. You might find yourself stumped or running out of time when you sit down and put pen to paper.

About the Author

Linda Basilicato has been writing food and lifestyle articles since 2005 for newspapers and online publications such as eHow.com. She graduated magna cum laude from Stony Brook University in New York and also holds a Master of Arts in philosophy from the University of Montana.

Related Articles

How to Answer a Reading Prompt on Standardized Test

Steps to Writing Research Paper Abstracts

How to Do a Nursing Proctored Essay

How to Use Cornell Note Taking

How to Prepare for an ESL Test

Do Outlines Need to Be in Complete Sentences?

How to Write an Explanation Essay

How to Make an Outline for an Informative Essay

How to Answer a Question in Paragraph Form

How Do I Write a Short Response on a Standardized Test?

Tips on Writing an Essay on a Final Exam

How to Write a Rough Draft

How to Make Note Cards

Note Taking Method for More Effective Studying

How to Answer Open-Ended Essay Questions

Tips for High School Students on Creating Introductions...

How to Summarize an Essay or Article

How to Study for the NAPLEX

How to Write a DBQ Essay

How to Write an AP Synthesis Essay

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

Last places remaining for July 14th and July 28th courses . Enrol now and join students from 175 countries for the summer of a lifetime

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument. Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

Word Choice

What this handout is about.

This handout can help you revise your papers for word-level clarity, eliminate wordiness and avoid clichés, find the words that best express your ideas, and choose words that suit an academic audience.

Introduction

Writing is a series of choices. As you work on a paper, you choose your topic, your approach, your sources, and your thesis; when it’s time to write, you have to choose the words you will use to express your ideas and decide how you will arrange those words into sentences and paragraphs. As you revise your draft, you make more choices. You might ask yourself, “Is this really what I mean?” or “Will readers understand this?” or “Does this sound good?” Finding words that capture your meaning and convey that meaning to your readers is challenging. When your instructors write things like “awkward,” “vague,” or “wordy” on your draft, they are letting you know that they want you to work on word choice. This handout will explain some common issues related to word choice and give you strategies for choosing the best words as you revise your drafts.

As you read further into the handout, keep in mind that it can sometimes take more time to “save” words from your original sentence than to write a brand new sentence to convey the same meaning or idea. Don’t be too attached to what you’ve already written; if you are willing to start a sentence fresh, you may be able to choose words with greater clarity.

For tips on making more substantial revisions, take a look at our handouts on reorganizing drafts and revising drafts .

“Awkward,” “vague,” and “unclear” word choice

So: you write a paper that makes perfect sense to you, but it comes back with “awkward” scribbled throughout the margins. Why, you wonder, are instructors so fond of terms like “awkward”? Most instructors use terms like this to draw your attention to sentences they had trouble understanding and to encourage you to rewrite those sentences more clearly.

Difficulties with word choice aren’t the only cause of awkwardness, vagueness, or other problems with clarity. Sometimes a sentence is hard to follow because there is a grammatical problem with it or because of the syntax (the way the words and phrases are put together). Here’s an example: “Having finished with studying, the pizza was quickly eaten.” This sentence isn’t hard to understand because of the words I chose—everybody knows what studying, pizza, and eating are. The problem here is that readers will naturally assume that first bit of the sentence “(Having finished with studying”) goes with the next noun that follows it—which, in this case, is “the pizza”! It doesn’t make a lot of sense to imply that the pizza was studying. What I was actually trying to express was something more like this: “Having finished with studying, the students quickly ate the pizza.” If you have a sentence that has been marked “awkward,” “vague,” or “unclear,” try to think about it from a reader’s point of view—see if you can tell where it changes direction or leaves out important information.

Sometimes, though, problems with clarity are a matter of word choice. See if you recognize any of these issues:

- Misused words —the word doesn’t actually mean what the writer thinks it does. Example : Cree Indians were a monotonous culture until French and British settlers arrived. Revision: Cree Indians were a homogenous culture.

- Words with unwanted connotations or meanings. Example : I sprayed the ants in their private places. Revision: I sprayed the ants in their hiding places.

- Using a pronoun when readers can’t tell whom/what it refers to. Example : My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though he didn’t like him very much. Revision: My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though Jake doesn’t like Trey very much.

- Jargon or technical terms that make readers work unnecessarily hard. Maybe you need to use some of these words because they are important terms in your field, but don’t throw them in just to “sound smart.” Example : The dialectical interface between neo-Platonists and anti-disestablishment Catholics offers an algorithm for deontological thought. Revision : The dialogue between neo-Platonists and certain Catholic thinkers is a model for deontological thought.

- Loaded language. Sometimes we as writers know what we mean by a certain word, but we haven’t ever spelled that out for readers. We rely too heavily on that word, perhaps repeating it often, without clarifying what we are talking about. Example : Society teaches young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change society. Revision : Contemporary American popular media, like magazines and movies, teach young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change the images and role models girls are offered.

Sometimes the problem isn’t choosing exactly the right word to express an idea—it’s being “wordy,” or using words that your reader may regard as “extra” or inefficient. Take a look at the following list for some examples. On the left are some phrases that use three, four, or more words where fewer will do; on the right are some shorter substitutes:

| I came to the realization that | I realized that |

| She is of the opinion that | She thinks that |

| Concerning the matter of | About |

| During the course of | During |

| In the event that | If |

| In the process of | During, while |

| Regardless of the fact that | Although |

| Due to the fact that | Because |

| In all cases | Always |

| At that point in time | Then |

| Prior to | Before |

Keep an eye out for wordy constructions in your writing and see if you can replace them with more concise words or phrases.

In academic writing, it’s a good idea to limit your use of clichés. Clichés are catchy little phrases so frequently used that they have become trite, corny, or annoying. They are problematic because their overuse has diminished their impact and because they require several words where just one would do.

The main way to avoid clichés is first to recognize them and then to create shorter, fresher equivalents. Ask yourself if there is one word that means the same thing as the cliché. If there isn’t, can you use two or three words to state the idea your own way? Below you will see five common clichés, with some alternatives to their right. As a challenge, see how many alternatives you can create for the final two examples.

| Agree to disagree | Disagree |

| Dead as a doornail | Dead |

| Last but not least | Last |

| Pushing the envelope | Approaching the limit |

| Up in the air | Unknown/undecided |

Try these yourself:

| Play it by ear | _____?_____ |

| Let the cat out of the bag | _____?_____ |

Writing for an academic audience

When you choose words to express your ideas, you have to think not only about what makes sense and sounds best to you, but what will make sense and sound best to your readers. Thinking about your audience and their expectations will help you make decisions about word choice.

Some writers think that academic audiences expect them to “sound smart” by using big or technical words. But the most important goal of academic writing is not to sound smart—it is to communicate an argument or information clearly and convincingly. It is true that academic writing has a certain style of its own and that you, as a student, are beginning to learn to read and write in that style. You may find yourself using words and grammatical constructions that you didn’t use in your high school writing. The danger is that if you consciously set out to “sound smart” and use words or structures that are very unfamiliar to you, you may produce sentences that your readers can’t understand.

When writing for your professors, think simplicity. Using simple words does not indicate simple thoughts. In an academic argument paper, what makes the thesis and argument sophisticated are the connections presented in simple, clear language.

Keep in mind, though, that simple and clear doesn’t necessarily mean casual. Most instructors will not be pleased if your paper looks like an instant message or an email to a friend. It’s usually best to avoid slang and colloquialisms. Take a look at this example and ask yourself how a professor would probably respond to it if it were the thesis statement of a paper: “Moulin Rouge really bit because the singing sucked and the costume colors were nasty, KWIM?”

Selecting and using key terms

When writing academic papers, it is often helpful to find key terms and use them within your paper as well as in your thesis. This section comments on the crucial difference between repetition and redundancy of terms and works through an example of using key terms in a thesis statement.

Repetition vs. redundancy

These two phenomena are not necessarily the same. Repetition can be a good thing. Sometimes we have to use our key terms several times within a paper, especially in topic sentences. Sometimes there is simply no substitute for the key terms, and selecting a weaker term as a synonym can do more harm than good. Repeating key terms emphasizes important points and signals to the reader that the argument is still being supported. This kind of repetition can give your paper cohesion and is done by conscious choice.

In contrast, if you find yourself frustrated, tiredly repeating the same nouns, verbs, or adjectives, or making the same point over and over, you are probably being redundant. In this case, you are swimming aimlessly around the same points because you have not decided what your argument really is or because you are truly fatigued and clarity escapes you. Refer to the “Strategies” section below for ideas on revising for redundancy.

Building clear thesis statements

Writing clear sentences is important throughout your writing. For the purposes of this handout, let’s focus on the thesis statement—one of the most important sentences in academic argument papers. You can apply these ideas to other sentences in your papers.

A common problem with writing good thesis statements is finding the words that best capture both the important elements and the significance of the essay’s argument. It is not always easy to condense several paragraphs or several pages into concise key terms that, when combined in one sentence, can effectively describe the argument.

However, taking the time to find the right words offers writers a significant edge. Concise and appropriate terms will help both the writer and the reader keep track of what the essay will show and how it will show it. Graders, in particular, like to see clearly stated thesis statements. (For more on thesis statements in general, please refer to our handout .)

Example : You’ve been assigned to write an essay that contrasts the river and shore scenes in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. You work on it for several days, producing three versions of your thesis:

Version 1 : There are many important river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn.

Version 2 : The contrasting river and shore scenes in Huckleberry Finn suggest a return to nature.

Version 3 : Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

Let’s consider the word choice issues in these statements. In Version 1, the word “important”—like “interesting”—is both overused and vague; it suggests that the author has an opinion but gives very little indication about the framework of that opinion. As a result, your reader knows only that you’re going to talk about river and shore scenes, but not what you’re going to say. Version 2 is an improvement: the words “return to nature” give your reader a better idea where the paper is headed. On the other hand, they still do not know how this return to nature is crucial to your understanding of the novel.

Finally, you come up with Version 3, which is a stronger thesis because it offers a sophisticated argument and the key terms used to make this argument are clear. At least three key terms or concepts are evident: the contrast between river and shore scenes, a return to nature, and American democratic ideals.

By itself, a key term is merely a topic—an element of the argument but not the argument itself. The argument, then, becomes clear to the reader through the way in which you combine key terms.

Strategies for successful word choice

- Be careful when using words you are unfamiliar with. Look at how they are used in context and check their dictionary definitions.

- Be careful when using the thesaurus. Each word listed as a synonym for the word you’re looking up may have its own unique connotations or shades of meaning. Use a dictionary to be sure the synonym you are considering really fits what you are trying to say.

- Under the present conditions of our society, marriage practices generally demonstrate a high degree of homogeneity.

- In our culture, people tend to marry others who are like themselves. (Longman, p. 452)

- Before you revise for accurate and strong adjectives, make sure you are first using accurate and strong nouns and verbs. For example, if you were revising the sentence “This is a good book that tells about the Revolutionary War,” think about whether “book” and “tells” are as strong as they could be before you worry about “good.” (A stronger sentence might read “The novel describes the experiences of a soldier during the Revolutionary War.” “Novel” tells us what kind of book it is, and “describes” tells us more about how the book communicates information.)

- Try the slash/option technique, which is like brainstorming as you write. When you get stuck, write out two or more choices for a questionable word or a confusing sentence, e.g., “questionable/inaccurate/vague/inappropriate.” Pick the word that best indicates your meaning or combine different terms to say what you mean.

- Look for repetition. When you find it, decide if it is “good” repetition (using key terms that are crucial and helpful to meaning) or “bad” repetition (redundancy or laziness in reusing words).

- Write your thesis in five different ways. Make five different versions of your thesis sentence. Compose five sentences that express your argument. Try to come up with four alternatives to the thesis sentence you’ve already written. Find five possible ways to communicate your argument in one sentence to your reader. (We’ve just used this technique—which of the last five sentences do you prefer?)Whenever we write a sentence we make choices. Some are less obvious than others, so that it can often feel like we’ve written the sentence the only way we know how. By writing out five different versions of your thesis, you can begin to see your range of choices. The final version may be a combination of phrasings and words from all five versions, or the one version that says it best. By literally spelling out some possibilities for yourself, you will be able to make better decisions.

- Read your paper out loud and at… a… slow… pace. You can do this alone or with a friend, roommate, TA, etc. When read out loud, your written words should make sense to both you and other listeners. If a sentence seems confusing, rewrite it to make the meaning clear.

- Instead of reading the paper itself, put it down and just talk through your argument as concisely as you can. If your listener quickly and easily comprehends your essay’s main point and significance, you should then make sure that your written words are as clear as your oral presentation was. If, on the other hand, your listener keeps asking for clarification, you will need to work on finding the right terms for your essay. If you do this in exchange with a friend or classmate, rest assured that whether you are the talker or the listener, your articulation skills will develop.

- Have someone not familiar with the issue read the paper and point out words or sentences they find confusing. Do not brush off this reader’s confusion by assuming they simply doesn’t know enough about the topic. Instead, rewrite the sentences so that your “outsider” reader can follow along at all times.

- Check out the Writing Center’s handouts on style , passive voice , and proofreading for more tips.

Questions to ask yourself

- Am I sure what each word I use really means? Am I positive, or should I look it up?

- Have I found the best word or just settled for the most obvious, or the easiest, one?

- Am I trying too hard to impress my reader?

- What’s the easiest way to write this sentence? (Sometimes it helps to answer this question by trying it out loud. How would you say it to someone?)

- What are the key terms of my argument?

- Can I outline out my argument using only these key terms? What others do I need? Which do I not need?

- Have I created my own terms, or have I simply borrowed what looked like key ones from the assignment? If I’ve borrowed the terms, can I find better ones in my own vocabulary, the texts, my notes, the dictionary, or the thesaurus to make myself clearer?

- Are my key terms too specific? (Do they cover the entire range of my argument?) Can I think of specific examples from my sources that fall under the key term?

- Are my key terms too vague? (Do they cover more than the range of my argument?)

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cook, Claire Kehrwald. 1985. Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Grossman, Ellie. 1997. The Grammatically Correct Handbook: A Lively and Unorthodox Review of Common English for the Linguistically Challenged . New York: Hyperion.

Houghton Mifflin. 1996. The American Heritage Book of English Usage: A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

O’Conner, Patricia. 2010. Woe Is I: The Grammarphobe’s Guide to Better English in Plain English , 3rd ed. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Tarshis, Barry. 1998. How to Be Your Own Best Editor: The Toolkit for Everyone Who Writes . New York: Three Rivers Press.

Williams, Joseph, and Joseph Bizup. 2017. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace , 12th ed. Boston: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Memorise an Entire Essay or Speech

Sharing is caring!

- Facebook 4904

- Pinterest 38

How to memorise a complete essay or speech

Christmas and New year is over and for some there looms the prospect of mid term exams. A lot of these exams will be closed book exams. A closed book exam tests your knowledge and memory of a subject. One of the ways in which some students prepare is to actively learn the subject areas and also look at past questions and anticipate a question which might come up. At the moment my wife is studying for exams in which she is actively learning her subjects and also she has written 3 x 500 word essays on the three areas of study.

Together we have come up with a system which means that she can memorise a 500 word essay in 1 day and 3 x 500 word essays in 3 days. Together with actively learning the subject she is confident that she has prepared well.

In this article I will show you the system we came up with to memorise 1500 words verbatim. Sound hard? It is actually quite easy and is a system I used when at university studying for my psychology degree for 2 x 1000 word essays.

This method can also be used for memorising any kind of written work or speech.

Before you begin

Before you begin this it is important to actually believe that you can memorise a complete essay or speech whether it be 500 words or 2000 words. When I first suggested using this method to my wife she said that she would never be able to memorise an essay word for word.

Once she got over this and started telling herself that she could do it we started.

Active learning

First off, this method of memorising an essay should not be substituted for actively learning a subject. Active learning is when you read, not skim, the subject area and take note of the key points. Cross reading is also very good for active learning. This is when you read books on the subjects by different authors. Some authors are not good at getting information across so cross reading is an excellent way learning.

The method for memorising an essay or speech.

You will need to write out the essay or speech first. Treat this part of the process as if you were writing an essay to hand in for marking by your lecturer. In other words make sure it is worthy of memorising.

When you have written the essay make sure it is grammatically correct as you will be memorising every comma and full stop.

When you are sure you have a good essay or speech print it off and mark down the left margin the number of paragraphs e.g. if you have 6 paragraphs write at the side of each paragraph the numbers 1 "“ 6. In the right hand margin write the number of sentences in each paragraph. This is the first part of the memorisation process.

A quiet place to study

Now, make sure you have quiet space to be able to read, walk and vocalise your essay. When you are sure you will not be interrupted you can start.

With your printed essay start walking and reading out loud the essay or speech. When you have read it out loud a few times go back to the first sentence and read it out loud. Then read it again and again until you have memorised it. When you are confident you have memorised it word for word go on to the next sentence. When you have memorised the second sentence, whilst walking vocalise the first two sentences without looking at your printed essay. If you are okay with this go on to do the same with your 3rd sentence and so on until you have memorised your first full paragraph. This can take anywhere between 15 "“ 45 depending on motivation, alertness, quietness etc.

The reason I ask you to walk is to keep your blood flowing whilst memorising. If you are sitting down you might nod off, by walking it will prevent you from nodding off. I find walking up and down an excellent way to concentrate on reading.

Keep reading, and vocalising your essay or speech until you have memorised it completely. When you are confident of having memorised it. Vocalise it without looking at your printed sheet. If you get it right, do it again, and if you get it right a second time reward yourself with a cup of tea or coffee or whatever is your want and leave it for a few hours.

When a few hours have passed go back to the essay, read it out loud whilst walking and looking at the printed sheet and then try to memorise it again.

Once you are confident that you have memorised it completely, at the bottom of the page write down the first few words of each sentence of your essay, separated by a comma, and number each line for each paragraph. When you have done that put in the number of sentences at the end of the list and bracket it.

For example if I was writing out the first few words of this article for the first 3 paragraphs it would look like this;

- Christmas and New year, A lot of, A closed book, One of the, At the moment (5)

- Together we have, Together with actively (2)

- In this article, sound hard? (2)

Now what you should do is only look at the list at the bottom of the paper and read out from that whilst walking. This way you are only looking at the first few words and finishing the sentence without looking at it. If you get stuck just go back to the main essay and look at it, until you have got it completely.

Now memorise the bottom of the sheet of paper with the first few words of the essay and how many sentences are in each paragraph. This should only take 10-15 minutes at the most.

This sounds a very convoluted way of memorising an essay but it is a lot easier than it reads here.

Time taken to memorise

You should be able to memorise a full 500 word essay in about 3 hours, for your first time, using the above method. When you are practiced you should be able to memorise a 500 word essay in about 60 "“ 90 minutes.

Some Amazing Comments

You may also like, 50 jobs that ai will replace in the next 5 years, what is the tinkerbell effect, discover your emotional intelligence, the love language quiz will reveal your true self, the esm method of goal setting, 7 things you don't want to learn too late in life, about the author, steven aitchison.

Steven Aitchison is the author of The Belief Principle and an online trainer teaching personal development and online business. He is also the creator of this blog which has been running since August 2006.

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

Memorizer : Memorizing, made easier.

Enter what you want to memorize. Be sure to use line breaks.

Hello there! Want to focus? Go fullscreen. Not sure what to memorize? Try an example.

Help me memorize it!

Firstly, say it at least a few times. Try glancing at the screen briefly.

It might help to also write down what you're trying to memorize. Even when writing, make sure to glance at the screen as briefly as possible.

It's best to repeat this step until you know the flow of the text.

Secondly, say it without mistakes . Below are the first letters of each word.

Unlike the previous step, keep looking at the text to ensure that you're not skipping words.

Make sure you're comfortable with every line of the text.

Thirdly, say it without pausing . Below are the first words of each line.

If you have to learn a lot of text, try memorizing it in parts first and then all together. This is so that you don't take ages to get past this step.

If you're unsure about a word, go back two steps and reread that part.

Great! Repeat these steps every hour or so until it's memorized. Try saying it right now.

Text saved! When you come back later you won't have to enter it again. Delete saved text.

Available offline! You can use Memorizer without an internet connection.

Back Restart

About Memorizer

This free, streamlined memorization tool can help you with lines , poems , speeches and monologues - basically anything that needs to be spoken.

Memorizer works with dozens of languages , including English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and German.

Memorizer Options

Dark Mode Fullscreen

Latest Features

2015/10: Offers dark mode (in supported browsers). 2013/12: Available offline (in supported browsers). 2013/12: Calculates approximate speaking time.

Keyboard Shortcuts

Next step : ctrl / cmd + enter Enter fullscreen: f Exit fullscreen: esc

Memorization Tips

You learn best by hearing , seeing , or doing , so find out what type of learner you are and have matching memorization techniques.

In addition, ask people who know you well and/or are familiar with memorizing (teachers, actors, etc.) to help you out.

Make sure to experiment - the only way to find out how you memorize best is by trying to memorize in different ways.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Words to Use in an Essay: 300 Essay Words

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

Words to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary.

It’s not easy to write an academic essay .

Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way.

To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life.

If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place!

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay.

The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write.

You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay.

That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay.

Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay.

When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases:

To use the words of X

According to X

As X states

Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.”

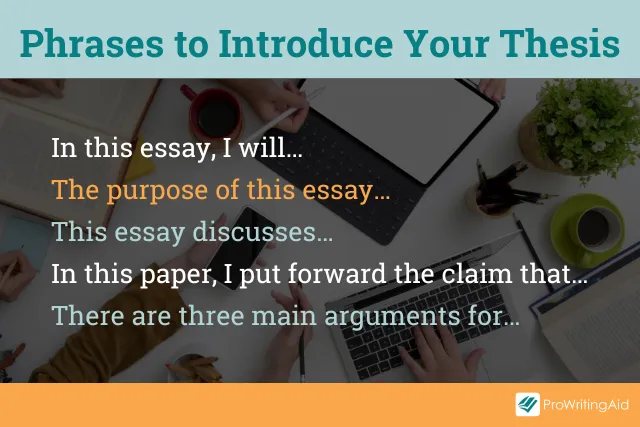

Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper.

If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases:

In this essay, I will…

The purpose of this essay…

This essay discusses…

In this paper, I put forward the claim that…

There are three main arguments for…

Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students.

After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea.

When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words:

First and foremost

First of all

To begin with

Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers.

All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on.

The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence.

It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research.

Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay.

It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random.

Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional.

The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea:

Additionally

In addition

Furthermore

Another key thing to remember

In the same way

Correspondingly

Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces.

Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words:

In other words

To put it another way

That is to say

To put it more simply

Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.”

Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words:

For instance

To give an illustration of

To exemplify

To demonstrate

As evidence

Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward.

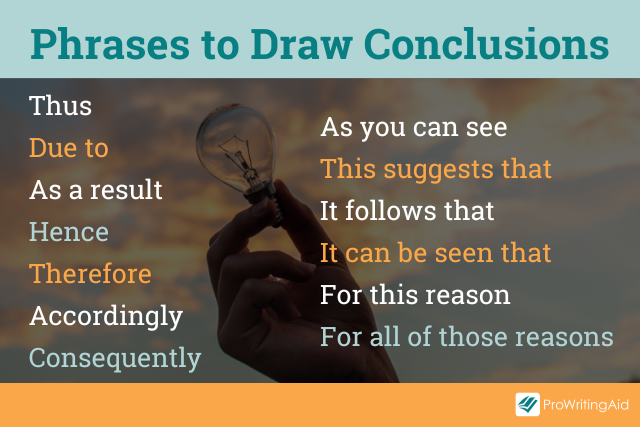

Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said.

When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words:

As a result

Accordingly

As you can see

This suggests that

It follows that

It can be seen that

For this reason

For all of those reasons

Consequently

Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”

When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words:

What’s more

Not only…but also

Not to mention

To say nothing of

Another key point

Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct.

Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words:

On the one hand / on the other hand

Alternatively

In contrast to

On the contrary

By contrast

In comparison

Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived.

Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases:

Having said that

Differing from

In spite of

With this in mind

Provided that

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

Notwithstanding

Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century.

Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay.

Strong Verbs for Academic Writing

Verbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb.

You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb.

For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail.

Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine.

Verbs that show change:

Accommodate

Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something:

Verbs that show increase:

Verbs that show decrease:

Deteriorate

Verbs that relate to parts of a whole:

Comprises of

Is composed of

Constitutes

Encompasses

Incorporates

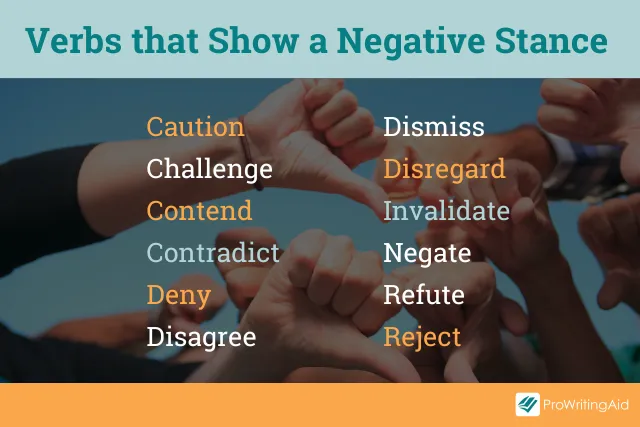

Verbs that show a negative stance:

Misconstrue

Verbs that show a positive stance:

Substantiate

Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence:

Corroborate

Demonstrate

Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis:

Contemplate

Hypothesize

Investigate

Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format:

Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic Essays

You should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences.

However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay.

Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis:

Significant

Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis:

Controversial

Insignificant

Questionable

Unnecessary

Unrealistic

Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays:

Comprehensively

Exhaustively

Extensively

Respectively

Surprisingly

Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis.

In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words:

In conclusion

To summarize

In a nutshell

Given the above

As described

All things considered

Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever.

In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought.

To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words:

Unquestionably

Undoubtedly

Particularly

Importantly

Conclusively

It should be noted

On the whole

Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure.

These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way.

There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics.

If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature.

So how do you improve your vocabulary skills?

The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words.

One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading.

Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays.

You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay.

Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible.

Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.

There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates

Published on September 18, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction , a body , and a conclusion . But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

The basics of essay structure, chronological structure, compare-and-contrast structure, problems-methods-solutions structure, signposting to clarify your structure, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay structure.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

| Part | Content |

|---|---|

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex . The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay . General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis . Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.