Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

Thesis Statements

What is a thesis statement.

Your thesis statement is one of the most important parts of your paper. It expresses your main argument succinctly and explains why your argument is historically significant. Think of your thesis as a promise you make to your reader about what your paper will argue. Then, spend the rest of your paper–each body paragraph–fulfilling that promise.

Your thesis should be between one and three sentences long and is placed at the end of your introduction. Just because the thesis comes towards the beginning of your paper does not mean you can write it first and then forget about it. View your thesis as a work in progress while you write your paper. Once you are satisfied with the overall argument your paper makes, go back to your thesis and see if it captures what you have argued. If it does not, then revise it. Crafting a good thesis is one of the most challenging parts of the writing process, so do not expect to perfect it on the first few tries. Successful writers revise their thesis statements again and again.

A successful thesis statement:

- makes an historical argument

- takes a position that requires defending

- is historically specific

- is focused and precise

- answers the question, “so what?”

How to write a thesis statement:

Suppose you are taking an early American history class and your professor has distributed the following essay prompt:

“Historians have debated the American Revolution’s effect on women. Some argue that the Revolution had a positive effect because it increased women’s authority in the family. Others argue that it had a negative effect because it excluded women from politics. Still others argue that the Revolution changed very little for women, as they remained ensconced in the home. Write a paper in which you pose your own answer to the question of whether the American Revolution had a positive, negative, or limited effect on women.”

Using this prompt, we will look at both weak and strong thesis statements to see how successful thesis statements work.

While this thesis does take a position, it is problematic because it simply restates the prompt. It needs to be more specific about how the Revolution had a limited effect on women and why it mattered that women remained in the home.

Revised Thesis: The Revolution wrought little political change in the lives of women because they did not gain the right to vote or run for office. Instead, women remained firmly in the home, just as they had before the war, making their day-to-day lives look much the same.

This revision is an improvement over the first attempt because it states what standards the writer is using to measure change (the right to vote and run for office) and it shows why women remaining in the home serves as evidence of limited change (because their day-to-day lives looked the same before and after the war). However, it still relies too heavily on the information given in the prompt, simply saying that women remained in the home. It needs to make an argument about some element of the war’s limited effect on women. This thesis requires further revision.

Strong Thesis: While the Revolution presented women unprecedented opportunities to participate in protest movements and manage their family’s farms and businesses, it ultimately did not offer lasting political change, excluding women from the right to vote and serve in office.

Few would argue with the idea that war brings upheaval. Your thesis needs to be debatable: it needs to make a claim against which someone could argue. Your job throughout the paper is to provide evidence in support of your own case. Here is a revised version:

Strong Thesis: The Revolution caused particular upheaval in the lives of women. With men away at war, women took on full responsibility for running households, farms, and businesses. As a result of their increased involvement during the war, many women were reluctant to give up their new-found responsibilities after the fighting ended.

Sexism is a vague word that can mean different things in different times and places. In order to answer the question and make a compelling argument, this thesis needs to explain exactly what attitudes toward women were in early America, and how those attitudes negatively affected women in the Revolutionary period.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a negative impact on women because of the belief that women lacked the rational faculties of men. In a nation that was to be guided by reasonable republican citizens, women were imagined to have no place in politics and were thus firmly relegated to the home.

This thesis addresses too large of a topic for an undergraduate paper. The terms “social,” “political,” and “economic” are too broad and vague for the writer to analyze them thoroughly in a limited number of pages. The thesis might focus on one of those concepts, or it might narrow the emphasis to some specific features of social, political, and economic change.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution paved the way for important political changes for women. As “Republican Mothers,” women contributed to the polity by raising future citizens and nurturing virtuous husbands. Consequently, women played a far more important role in the new nation’s politics than they had under British rule.

This thesis is off to a strong start, but it needs to go one step further by telling the reader why changes in these three areas mattered. How did the lives of women improve because of developments in education, law, and economics? What were women able to do with these advantages? Obviously the rest of the paper will answer these questions, but the thesis statement needs to give some indication of why these particular changes mattered.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a positive impact on women because it ushered in improvements in female education, legal standing, and economic opportunity. Progress in these three areas gave women the tools they needed to carve out lives beyond the home, laying the foundation for the cohesive feminist movement that would emerge in the mid-nineteenth century.

Thesis Checklist

When revising your thesis, check it against the following guidelines:

- Does my thesis make an historical argument?

- Does my thesis take a position that requires defending?

- Is my thesis historically specific?

- Is my thesis focused and precise?

- Does my thesis answer the question, “so what?”

Download as PDF

6265 Bunche Hall Box 951473 University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473 Phone: (310) 825-4601

Other Resources

- UCLA Library

- Faculty Intranet

- Department Forms

- Office 365 Email

- Remote Help

Campus Resources

- Maps, Directions, Parking

- Academic Calendar

- University of California

- Terms of Use

Social Sciences Division Departments

- Aerospace Studies

- African American Studies

- American Indian Studies

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Asian American Studies

- César E. Chávez Department of Chicana & Chicano Studies

- Communication

- Conservation

- Gender Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Political Science

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.20: Video: Evolution of the Thesis Statement

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59392

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Previous pages established the importance of a working thesis statement early in the writing process. This working thesis is likely to be revisited and revised several times as the writing process continues.

After gathering evidence, and before starting to write the essay itself, is a natural point to look again at the project’s thesis statement. The following video offers friendly, appealing advice for developing a thesis statement more concretely.

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/itcc/?p=298

- Video: Evolution of the Thesis Statement. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- How To Write A Killer Thesis Statement by Shmoop. Authored by : Shmoop. Located at : https://youtu.be/8wxE8R_x5I0 . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

The evolutionary contingency thesis and evolutionary idiosyncrasies

- Open access

- Published: 21 March 2019

- Volume 34 , article number 22 , ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- T. Y. William Wong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2750-7990 1

6618 Accesses

7 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Much philosophical progress has been made in elucidating the idea of evolutionary contingency in a recent re-burgeoning of the debate. However, additional progress has been impaired on three fronts. The first relates to its characterisation: the under-specification of various contingency claims has made it difficult to conceptually pinpoint the scope to which ‘contingency’ allegedly extends , as well as which biological forms are in contention. That is—there appears to be no systematic means with which to fully specify contingency claims which has led to a tendency for authors to talk past each other. Secondly, on the matter of evidence, recent research has focused on the evidential import of (genuine) convergent evolution which is taken to disconfirm the evolutionary contingency thesis. However, there has been a neglect of convergent evolution’s converse: ‘evolutionary idiosyncrasies’ or the singular evolution of certain forms, which I argue is evidentially supportive of evolutionary contingency. Thirdly, evolutionary contingency has often been claimed to vary in degrees and that the debate, itself, is a matter of ‘relative significance’ (sensu Beatty). However, there has been no formal method of evaluating the strength of contingency and its relative significance in a particular domain. In this paper, I address all three issues by (i) proposing a systematic means of fully specifying contingency theses with the concept of the modal range . Secondly, I (ii) propose an account of evolutionary idiosyncrasies , investigate the explanations for their occurrences, and, subsequently, spell out their significance with respect to the evolutionary contingency thesis. Finally, having been equipped with the evidential counterpart to convergent evolution, I shall (iii) sketch a likelihood framework for evaluating, precisely on the basis of a sequence of opposing data, the strength and relative significance of evolutionary contingency in a particular domain. With this in hand, the relative observations of idiosyncrasies and convergences can be informative of the strength and relative significance of contingency in any particular domain.

Similar content being viewed by others

The domain relativity of evolutionary contingency

Gouldian arguments and the sources of contingency.

Incommensurability in Evolutionary Biology: The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis Controversy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The idea of evolutionary contingency has undergone a substantial resurgence in recent years with a number of contingency-theorists entertaining the modality of evolutionarily-derived biological forms. At present, there is no consensus as to what evolutionary contingency means other than to broadly suggest that certain evolved biological forms could have been otherwise . The suggestion is that there is an element of ‘chanciness’ (or some similar descriptor) to which forms would have actually evolved in the history of life. If evolutionary contingency were true, then as the story goes: had the ‘tape of life’ been replayed (from a different or the same starting point), the result would be an evolutionary menagerie bearing biological forms markedly different from the present ones. That is—instead of our ever so familiar birds, reptiles, and mammals, we would be left with forms ‘endlessly most beautiful’… should we find ourselves fortunate enough to remain.

The majority of recent papers have set out to propose etiological structures such as ‘casual dependence’, ‘path dependence’, or, ‘sensitivity to initial conditions’ that supposedly account for the modality of evolutionarily contingent forms (e.g. Beatty 2006 ; Desjardins 2011, 2016 ; Powell 2012 ; Sterelny 2005 ; Turner 2011 ). Certain biological forms are held to be contingent, or non-contingent, precisely because they are, or are not, at the end of a path dependent causal chain, for example. This inquisition into the relevant etiological structure for contingency is important because an advocate of the evolutionary contingency thesis (ECT) would assert that particular biological forms failed to robustly evolve because certain etiological conditions did not hold—e.g. the outcome was contingent because it was highly sensitive to initial conditions. However, aside from the question of which of the etiological structures best capture evolutionarily contingent dynamics, it is not clear which biological forms are meant to lack robustness and, furthermore, how far robustness is to extend —both of which makes conceptually grasping and empirically evaluating the thesis difficult. Despite the, now, frequent biological and philosophical discussions of the ECT, there has hitherto been no principled way of answering these two questions. Hence, there is a real need for some theoretical tools enabling one to fully spell out what the evolutionary contingency thesis amounts to. To this end, in “ The modal range ” section, I propose the idea of the modal range which allows contingency-theorists to relativise contingency claims to particular, more tractable, domains of interest.

The antithesis of the evolutionary contingency thesis—the robust view of life (RVL)—asserts (amongst other things) that certain biological forms are robustly realised which is to say that these forms are repeatedly realised across a number of evolutionary scenarios. Footnote 1 This view advocates that due to reasons of adaptive optimality or certain prevailing structural properties (sensu Sole and Goodwin 2001 ), certain forms are disposed to repeatedly evolve within some range of evolutionary scenarios. There is, however, a kind of phenomenon, seldomly investigated, that speaks against such repeatability. These are forms that, for one reason or another, have evolved uniquely . Often peculiar and distinctive, these forms constitute direct counter-examples to the robust view of life in that their evolution has been singular within the corresponding range. But their evidential role extends further than acting as mere counter-examples: the reasons for their singular evolution are informative of the way in which evolution has failed to be robust. Accordingly, one task of the present paper is to explicate what these reasons are and, more generally, investigate what these uniquely evolved forms— evolutionary idiosyncrasies —can say about the evolutionary contingency thesis.

Within the current evolutionary contingency literature, the bulk of the empirical evidence has been confined to ‘convergences’ which purportedly undermine the ECT by showing (i) that natural selection is ‘powerful’ enough to overcome historical encumbrances and, a fortiori , transcend individual phylogenetic constraints (e.g. Conway Morris 2003 ; Currie 2012a ; Powell 2012 ) or (ii) that there are structural properties (or functional constraints) of evolutionary systems that rigidly circumscribe the space of possible or probable forms (e.g. Sole and Goodwin 2001 ; Salazar-Ciudad et al. 2003 ; McGhee 2011 ; Brandon and McShea 2010 ). The latter refers to physical, chemical, functional, dynamical, or other aspects of an evolutionary system that dispose evolution towards certain forms. For example, certain chemical facts true within some evolutionary system may bound evolution towards particular RNA configurations within that system. In contrast to convergences, evolutionary idiosyncrasies, as we shall see, do just the converse: they demonstrate that (i) history fails to be a limiting factor in the determination of form (within an evolutionary system) and/or that (ii) there are limited structuralities that circumscribe the space of possible or probable forms (within an evolutionary system).

The term ‘evolutionary idiosyncrasies’ is non-standard and was first introduced as the title of the third chapter of Improbable Destinies where Losos ( 2017 ) provides an impressive catalogue of various evolutionary one - offs from the duck-billed platypus to the Hawaiian Alula plant. The platypus possesses, amongst its suite of peculiar traits, a leathery, electro-sensitive bill conducive for prey-searching whilst the Alula plant embodies the odd appearance of voluminous flowers at the top of a long and thick stalk, leading to its being known colloquially as ‘cabbage on a stick’. However, what makes idiosyncrasies evolutionarily interesting is not that they possess peculiar traits per se, but that their evolution has been a singular event. And, it is this singular evolution that I claim is at odds with the robust view of life and supportive of the ECT.

Despite the explicit intention of Improbable Destinies (Losos 2017 ) to evaluate the ECT, there is a noticeable paucity of investigation of the theoretical implications and/or philosophical significance of evolutionary idiosyncrasies with respect to the ECT . Nonetheless, Losos is to be commended for his pioneering step into a previously unrecognised area that is, as I argue in this paper, highly relevant for the ECT. Inspired by Losos’ lead, I consider possible explanations for the occurrence of idiosyncrasies and conclude that there are, exhaustively, four non-mutually-exclusive explanations which threaten the repeatability of form in one way or another.

The first explanation—(i) unique environments —asserts that certain forms evolved only once because the environmental conditions and/or selective pressures leading to that form has been unique. Secondly, (ii) natural selection may have been contingent or weak such that natural selection responds differently to the same environmental conditions as to lack consistency in its production of form or, fails to repeatedly produce the most superior form for a given environment. Thirdly, there may be (iii) multiple solutions to the same ecological problem (also known as Functional Equivalence) such that there are several equally-as-adaptive solutions that can evolve by natural selection. Fourthly, (iv) historicities , or difference-making historical events with a low objective probability of occurrence, such as genetic drift events or migration events may apply diversionary tendencies across evolutionary scenarios such that the same form does not repeatedly arise. As I consider these explanations in greater depth, it will become clear that they each undermine, at least, one of two necessary premises of the robust view of life: what I call, environment-trait uniformity and environmental regularity. As such, observations of idiosyncrasies speak against a robust view of life and, ipso facto , are supportive of the ECT.

In addition, I shall formally characterise the positive evidential link between idiosyncrasies and the ECT in quantitative terms as to lay the groundwork for, subsequently, sketching a likelihood framework for evaluating the ECT in light of a given body of evidence consisting of a sequence of opposing data: the presence of idiosyncrasies vis - à - vis convergences. The need for the likelihood framework is motivated by the two common assertions that evolutionary contingency is a matter of ‘relative significance’ (e.g. Beatty 1995 , 1997 , 2006 ) and that evolutionary contingency can vary by degrees (e.g. Powell 2012 ). Both assertions allegedly present methodological issues for evaluating the evolutionary contingency thesis (Ibid.; Beatty 1995 ; Powell and Mariscal 2015 ); the former in systematically evaluating and balancing opposing evidence, and the latter in quantifying contingency’s exact degree of strength.

However, the likelihood framework proffered here kills two birds with one stone. It offers a powerful, objective means with which to evaluate between various ECT’s of different strengths, and to do so precisely on the basis of opposing evidence. The two hypotheses hitherto encountered—the ECT and RVL—can be understood as absolute extremes at the polar ends of a ‘contingency spectrum’ which contains a number of intermediary hypotheses. I submit that by way of a likelihood function, one can compute the probability of a body of evidence (i.e. some number of idiosyncrasies and convergences) conferred by any contingency hypothesis on the spectrum. In this way, the relative proportions of idiosyncrasies versus convergences can be informative of how evolutionarily contingent a particular domain is: the more idiosyncrasies there are vis-à-vis convergences, the more evolutionarily contingent the domain is. Hence, the methodological pessimism associated with evolutionary contingency varying in degree or being a ‘relative significance’ dispute can be dissolved.

The plan is as follows: I begin by introducing the crucial notion of the modal range , so that contingency claims can be made precise with respect to what it means for a form to be robust or replicable. Following that, in “ Evolutionary idiosyncrasies and the Robust view of life ” section, I characterise evolutionary idiosyncrasies and illustrate the prima facie threat that they pose for the robust view of life. I, then, consider each of the four explanations for idiosyncrasies and explain how they each undermine the robust view of life. Moving on to the quantitative, in “ The likelihood framework and the contingency spectrum ” section, I advance two likelihood arguments (in the technical sense) to show that the likelihood ratio of idiosyncrasies in favour of the ECT (over the RVL) and the likelihood ratio of ‘convergences’ in favour of the RVL (over the ECT) are both above 1. Armed with these likelihood ratios which show the two phenomena’s direction of support on the contingency spectrum, I sketch a likelihood framework in which to evaluate the ECT given the idiosyncrasy-convergence dichotomy. In “ Evolutionary idiosyncrasies as differential evidence ” section, in order to demonstrate how idiosyncrasies can differ in their evidential strength , I consider certain statistical parameters, and draw a distinction between two different kinds of idiosyncrasies: divergent idiosyncrasies (DVI) and disparate idiosyncrasies (DPI), where the former is stronger evidence for the ECT than the latter. Moreover, both the evidential strength and the evidential target (i.e. which variant of the ECT) is also dependent on two conceptual dimensions in which idiosyncrasies can be defined and recognised. In this regard, I explain how an epistemic agent can adjust these dimensions to suit their respective epistemic projects.

The modal range

Contingency claims assert varying levels of robustness or repeatability for certain biological forms across an array of evolutionary scenarios. But, barring some indeterminist exceptions, Footnote 2 most contingency-theorists advocate that questions of evolutionary contingency are about the prevalence of biological forms amidst the variance of certain, important evolutionary conditions of epistemic interest. In other words, a biological form is robust if it invariantly evolves in a wide range of evolutionary scenarios where ( inter alia ) the initial conditions, geographical space, developmental generators, history, or, even nomological laws (may) differ between scenarios. Footnote 3 Some of these differences may be counterfactual such that what is of concern includes non-actual possibilities—for example, would a particular biological form still evolve in face of certain facts contrary to the actual world? In fact, contingency-theorists are often concerned with the evolution of forms in counterfactual scenarios (e.g. Beatty 1995 ; Conway Morris 2003 ; Beatty 2006 ; Powell 2012 ). As such, the range of scenarios need not be limited to the actual but can extend to the merely possible as well. For this reason, let us call the range of evolutionary scenarios under consideration for repeatability, the modal range .

The concept of the modal range is crucial in that it specifies the extent to which evolution is alleged to be contingent. To harken back to the introduction, it answers the question of how far robustness is to extend. A form is more-or-less robust within a specifically - defined modal range consisting of some evolutionary scenarios that may differ in certain respects. Contingency claims without a modal range index are not fully defined and are hence, difficult to conceptualise if not empirically evaluate. That is—contingency claims are defined in virtue of limiting the modal space (geographically, nomologically, historical, etc.) in which forms are alleged to be contingent. For example, if the modal range contains only evolutionary scenarios on Earth, then what is of concern is evolutionary contingency on Earth (e.g. Conway Morris 2003 ). Accordingly, then, for any question of evolutionary contingency, what is being asked is whether the evolutionary dynamics within some modal range are sufficient to result in the repeated evolution of certain forms within that range. A different modal range index entails a different contingency question and is likely to result in a different answer. In fact, the very same contingency-theorist (i.e. Vermeij 2006 ) may answer contingency questions in the affirmative for a modal range specifying early periods of life’s history—i.e. the Cambrian —yet vehemently deny contingency for later periods of life due to the sentiment that certain phenomena including (but not limited to) phylogenetic inertia or generative entrenchment will heavily constrain downstream possibilities (c.f. Shanahan 2011 ; Wimsatt 2001 ).

In general, the determination of the modal range is dependent on the demands of a contingency-theorist’s epistemic project. That is—if one were interested in the evolutionary contingency of some particular domain, then one ought to employ the appropriate modal range index as to track the relevant features of that domain and not of some other domain. Accordingly, given their respective epistemic goals, Conway Morris ( 2003 ) ought to consider the repeatability of forms within only evolutionary scenarios on Earth whilst Vermeij ( 2006 ) should take care to consider repeatability during the relevant time periods .

Nonetheless, due to the ambiguities afforded by a theoretically infinite number of modal range indices, one ought to be careful not to operationalise between two different senses of the ECT in any debate about the its truth, lest there be any argumentative cross-talk. Footnote 4 Moreover, when characterising a contingency-theorist’s view, it is imperative to refer to the modal range at hand. Exegetically, Gould has often been mistakenly portrayed as wholly denying the repeatability of form (e.g. McGhee 2011 , p. 271; see Powell and Mariscal ( 2015 ) for discussion). However, it is congruent with and, in fact, implied by Gould’s larger view of life that there will be some repeatability of form due to frozen, developmental constraints (Gould 1977 ; Gould and Lewontin 1979 ). To this end, Gould even points to a case of repeatability ( 2002 ): the repeated evolution of feeding appendages in the crustaceans due to certain developmental precursors (also discussed in Powell and Mariscal ( 2015 )). Importantly, Gould ( 1989 ) also claims that these developmental constraints could easily have been otherwise and hence, there is, undoubtedly, some contingency in this respect. The concept of the modal range allows one to recognise the nuances of Gould’s view. That is—Gould can be understood as denying the contingency of evolutionary forms for modal ranges with deep developmental entrenchments yet asserting contingency for modal ranges without such developmental entrenchments (probably, modal ranges upstream in history). Footnote 5 I shall, now, characterise evolutionary idiosyncrasies and outline the threat that they pose for the RVL.

Evolutionary idiosyncrasies and the robust view of life

To my knowledge, there has not yet been any formal definition of evolutionary idiosyncrasies (or equivalent Footnote 6 ) in the biological or philosophical literature. Although evolutionary oddities and peculiar biological forms are often cited (usually, to convey a sense of awe), a lack of an explicit formulation of this class of phenomena in the literature is not entirely surprising given that, historically, little theoretical significance has been attributed to them. However, as I argue that the existence of uniquely evolved biological forms in nature has considerable bearing to the ECT, this class of phenomena has sufficient theoretical significance to merit explicit formulation:

Evolutionary Idiosyncrasies : biological forms that are uniquely evolved (within some modal range Footnote 7 )

As such, evolutionary idiosyncrasies are defined by their singular evolution and not by the form’s uniqueness, per se. That is—there can be multiple instantiations of an idiosyncrasy: say, multiple platypus individuals, for example. The singular evolution of a form and its uniqueness are distinct notions and need not co-vary. Just as convergent evolution is defined by their having independent bouts of evolution rather than whether there are multiple instances of the form at hand, evolutionary idiosyncrasies (though uniquely evolved) can be multiply instantiated all the same. Conversely, if a form is unique, per se, in that it fails to be instantiated elsewhere in the modal range, it does not follow that the form is also an idiosyncrasy since the form may have evolved multiple times but has been, subsequently, reduced to a single instantiation. All in all, what matters is whether a form has independently evolved more than once as to be informative of the evolutionary dynamics, relevant to contingency, of a domain.

But even then, a caveat is in order: there are two conceptual complications with defining and recognising evolutionary idiosyncrasies. The first pertains to what it is that is supposed to be uniquely evolved. In other words, what is the subject of idiosyncrasy ? When it is said that a biological form Footnote 8 has uniquely evolved, is one referring to a particular trait like an electro-sensitive leathery bill, a particular species like the Hawaiian Alula, or, even a particular biological population ? A clear denotation of the subject of idiosyncrasy is required before its evolution can be even precluded elsewhere.

Furthermore, the determination of the subject of idiosyncrasy may also be plagued by the so-called grain issue . Just as almost always encountered with convergence, whether two forms are alike or different depends on the grain of the form’s description (Sterelny 2005 ; Currie 2012b ; Powell 2012 ). For example, some coarse-grained traits like predator avoidance is so broad as to have, undoubtedly, evolved across several evolutionary lineages. Yet, at the same time, a finer-grained trait—say camouflage —is likely to be less ubiquitous. An even finer-grained trait like a specific colour pattern of camouflage would be even less common. In general, coarse-grained resolutions yield fewer idiosyncrasies than fine-grained resolutions, ceterus paribus . Consequently, the number of idiosyncrasies (or whether there are any idiosyncrasies at all) appear to be a matter arbitrarily dependent on grain specification.

But note that the determination of the subject of idiosyncrasy and the grain of analysis, though related, are distinct. It is just that determining the subject of idiosyncrasy will involve taking a stand on the level of grain to invoke. This is because possible subjects of idiosyncrasy (i.e. traits, species, populations, etc.) are often amenable to different descriptions due to differences in resolution. For example, the fastest animal on Earth, the peregrine falcon possesses many traits. There is the coarse-grained trait of ‘being able to fly’, a finer-grained trait of ‘having wings’, and, an even finer-grained trait of having ‘pointed, stiff-feathered wings’. Yet, presumably, only the lattermost is a strong candidate for an idiosyncrasy. A different trait—say a pointed, loose - feathered - wing—is roughly at the same level of grain as the peregrine falcon’s stiff-feathered wing, but it is clearly a different subject of idiosyncrasy which may or may not be uniquely evolved. However, settling on any one of these traits to be the subject of idiosyncrasy will, at the same time, answer the question of grain: for example, the trait of having ‘pointed, stiff-feathered wings’ will simply have a, fine-grained, description at that level. Graining is merely a property of a subject of an idiosyncrasy. The point is that insofar as a subject of idiosyncrasy has been determined, the grain of analysis will also be given. The election of the grain is important only insofar as it is part and parcel of specifying the subject of idiosyncrasy.

Secondly, there is the question of the scope of uniqueness . Forms are idiosyncratic if and only if they are uniquely evolved, but what does it take to be uniquely evolved ? Let us say that Form A is uniquely evolved if and only if the same form has not evolved elsewhere . But, then, what does ‘elsewhere’ refer to? Are the forms to be considered ones found only on Earth or found beyond? Similarly, are forms in the ancient past or distant future to be considered? The widening of scope makes it less likely for any particular form to be uniquely evolved whilst narrowing the scope improves its chances.

These two complications present epistemic challenges in defining and recognising idiosyncrasies, but they do not undermine the concept, per se. That is—insofar as the subject of idiosyncrasy (including the grain of analysis), and the scope of uniqueness are specified, then there is very much a given number of idiosyncrasies in the world. For a ‘ theory of idiosyncrasies ’ then, it might be said that there are two conceptual dimensions in need of specification before idiosyncrasies are fully defined and thus, can be recognised. But the supposed conundrum is figuring out how, exactly, to specify these dimensions.

At this time, I respond briefly by pointing out that the specification of the subject of idiosyncrasy and the scope of uniqueness are wholly relative to the respective goals of individual epistemic agents and the nature of propositions they intend to make. This is because an alteration of either dimension will result in a shift of the evidential target of idiosyncrasies. For example, altering the scope of uniqueness shifts the variant of the ECT that is supported by idiosyncrasies since idiosyncrasies are now indicative of evolutionary singularity in a different modal range. That is—by altering the scope of uniqueness, idiosyncrasies are bouts of singular evolution in face of a different set of variances amongst evolutionary scenarios: perhaps, it is no longer singularity amongst scenarios with varying nomologies but varying histories. The independent variable(s) of the array has changed.

Recall that it is crucial in any debate about the contingency of evolution for the participants to hold fixed the modal range in which evolution is alleged to be contingent, lest there be argumentative cross-talk. So, suppose a contingency-theorist was interested in the evolutionary contingency of the terrestrial domain (i.e. on Earth). In this case, idiosyncrasies are evidentially relevant only if they are informative of the evolutionary dynamics of that domain . Any different—say if the scope of uniqueness of idiosyncrasies was extended to only one continent—then idiosyncrasies fail to be informative of the evolutionary dynamics (e.g. the power of natural selection or the existence of certain structuralities) present on Earth (barring extrapolation from continent to planet). As such, idiosyncrasies would not tell us about the wholesale repeatability of form on Earth, but only on one continent. Accordingly, if one were interested in the power of natural selection on Earth, then an Earth-wide scope of uniqueness would be appropriate. In other words, it is epistemically imperative that the scope of uniqueness of idiosyncrasies correspond to the modal range of the ECT variant in question. In a return to the topic of differential evidence in “ Evolutionary idiosyncrasies as differential evidence ” section, we shall see that an alteration of the subject of idiosyncrasy also shifts the evidential target. In general, taking a position on either of the two dimensions will not only affect the number of idiosyncrasies recognised but alter their evidential implications as well. Hence, the specification of the two conceptual dimensions depends on the epistemic demands of a contingency-theorist’s project.

In Improbable Destinies , Losos ( 2017 ) offers many examples of idiosyncrasies but, perhaps, most notable is the semi-aquatic duck - billed platypus , found only in eastern Australia. The platypus’ unique evolution is exemplified by the amalgamation of several peculiar features: its mammalian egg-laying, venomous spur, leathery bill, and prey-sensing electroreceptors. Losos’ point is that, as a whole , there has been no other species like the platypus. Footnote 9

There is tension between such cases of evolutionary idiosyncrasies and the robust view of life: if biological forms were robust in their evolution, then it would be striking that idiosyncratic forms like that of the platypus did not evolve more than once. This is because the robust view of life stipulates that the same evolutionary outcomes will repeatedly evolve within some modal range whilst idiosyncrasies assert, precisely, that there has been singular evolution within that modal range. Ceterus paribus , these are contradictory assertations.

The source of the tension stems from the fact that the robust view of life explains, in part, such repeatability by appealing to there being certain, definite environment - trait dyads : given any one environment, there is necessarily a given trait. Footnote 10 In other words, the robust view of life requires that certain evolutionary conditions necessarily lead to particular evolutionary outcomes. Footnote 11 This is either manifested by (i) a Hard Adaptationist sense of natural selection (Amundson 1994 ) that dictates that certain environmental pressures are met with the most superior solution (e.g. McGhee 2011 ; Powell 2012 ), or, (ii) that non-selective nomological aspects or the so-called structuralities of the environment dispose one particular outcome (e.g. McShea 1994 ; Sole and Goodwin 2001 ; Stayton 2008 ; Brandon and McShea 2010 ). But this environment - trait uniformity alone is not enough for robust repeatability since it is possible for same evolutionary conditions to fail to repeatedly exist within the modal range.

Accordingly, the remaining half of the explanation for robust repeatability is that there is, in fact, environmental regularity such that there are multiple instances of the same evolutionary environment within the modal range. Footnote 12 Putting these two parts together, the robust view of life says that a form, F 1 , is repeatedly realised in some modal range (say, within all Earth-like planets in the universe at all times) because (i) environment E 1 necessarily gives rise to form F 1 due to some evolutionary force (e.g. selection or drift), and (ii) environment E 1 can be widely found on Earth-like planets in the universe. Environment-trait uniformity and environmental regularity are two necessary premises (amongst others) that are required of the robust view of life in order to assert the repeatability of form. If, for instance, there was no environmental regularity within the modal range concerned then, despite the power of natural selection or functional constraints to dispose forms in certain environments, there would nonetheless be no repetition of form. Footnote 13 Alternatively, if certain environments do not guarantee particular forms, then despite an abundance of similar environments, the same form need not repeatedly result.

Accordingly, at a more fundamental level of analysis, the tension exists because observations of idiosyncrasies threaten the truth of the two premises of a robust view of life. That is—observations of idiosyncrasies provide reasons to dissolve the classical environment-trait dyad or reject that there are alternative histories with similar evolutionary conditions within the modal range. This is because the individual explanations for idiosyncrasies, themselves, logically contradict environment-trait uniformity and/or environmental regularity. To see this, let us now consider the four explanations in turn.

Explanations for evolutionary idiosyncrasies

Unique environments.

One obvious explanation for occurrences of idiosyncrasies is that the evolutionary environment in which an idiosyncrasy evolved was unique and so, it was no surprise that the idiosyncrasy evolved only once. In other words, the set of conditions that led to the evolution of an idiosyncrasy failed to be present elsewhere (within the modal range) such that the form, supposedly guaranteed by the environment, did not evolve elsewhere (within the modal range). Since an evolutionary environment (sensu lato Footnote 14 ) may be manifested by the set of selective pressures or non-selective nomological properties (i.e. structuralities sensu Sole & Goodwin), this could mean that the selective pressures were unique such that natural selection did not yield a similar form elsewhere or that the structuralities of the environment were unique such that a similar form did not result elsewhere. Footnote 15 (Or even that the amalgamation of both selective pressures and structuralities were unique.) In essence, a unique environment presents evolutionary conditions, not found elsewhere within the modal range, with which evolutionary forces are to operate. And so, it is no surprise that the result of these forces is a form that evolved only once within the modal range. Returning to the platypus example, perhaps, its evolution was one-off because the environmental conditions conducive to its evolution failed to be present elsewhere.

All in all, unique environments suffice to explain the occurrence of idiosyncrasies, but the existence of unique environments is logically opposed to the environmental regularity premise of the robust view of life. For obvious reasons, there cannot be both environmental regularity (i.e. more than one instance of the same environment) and a unique environment within a modal range. And so, if unique environments are to explain the occurrence of an idiosyncrasy within a modal range, then the robust view of life is false for that modal range.

Empirically, this sort of explanation is compelling. A recent review paper by Stuart et al. ( 2017 ) points outs that deviations from the expectation of ‘convergences’ is often a result of subtle environmental heterogeneity or subtle differences between environments. Other studies have a similar conclusion (e.g. Landry et al. 2007 ; Matthews et al. 2010 ; Moore et al. 2016 ). But this is not the only explanation for occurrences of idiosyncrasies.

Weak or contingent natural selection

Given that the natural habitat of the platypus (e.g. streams and ponds) appears to be ubiquitous on Earth (Losos 2017 , p. 88), Losos wonders why forms similar to the platypus could not be found elsewhere other than eastern Australia. In other words, for Losos, the evolutionary environment for the platypus is clearly not unique. His first gesture at resolving this curiosity is to point to the possibility that natural selection could be limited in its ability to generate the same form. That is—either natural selection is weak or contingent (he uses the word “unpredictable” in lieu of contingent Footnote 16 ). If natural selection were weak in the sense that it does not always succeed in resulting in the most superior solution, then identical evolutionary environments need not result in the same biological form under natural selection’s crank. For the advocate of the robust view of life, optimality reasons can explain why certain forms are robust (i.e. forms are robust because they are adaptive peaks) but such reasons must be coupled by some mechanism (i.e. hill climbing mechanism) that sufficiently ensures the evolution of the superior trait. Without the latter— if natural selection were ‘weak’ —then there is no reason to think that a trait will be robustly realised even if the trait in question were most superior.

As for Losos’ claim that idiosyncrasies can be explained by natural selection that is ‘contingent’, it is not clear what is exactly meant by this though one may surmise given his reference to random mutation and mutational order. Perhaps, natural selection is contingent in that natural selection is dependent on low probability events (often referred to as ‘chancy’ or ‘stochastic’ events) that generate the suite of genetic material made available and their ordering , like random mutation and mutational ordering (Mani and Clarke 1990 ), respectively. But if natural selection is contingent in this sense, then natural selection cannot guarantee a particular outcome given certain evolutionary environments; different outcomes may result depending on chancy precedents.

Accordingly, idiosyncrasies can occur despite any environmental regularity because natural selection failed to guarantee environment-trait uniformity due to either (i) selection’s limited ability to produce the most superior form or (ii) the chancy availability of genetic variance with which selection is dependent upon. Either way, an explanation of idiosyncrasy invoking weak or contingent natural selection dissolves the environment-trait dyad since certain evolutionary environments fail to guarantee particular outcomes.

But notice that explanations invoking the weakness or contingency of natural selection nonetheless ultimately rely on historical events. As above, natural selection is weak only because it at the mercy of past phylogenetic constraints and other historicities (c.f. Gould and Lewontin 1979 ). Likewise, natural selection is contingent only because it is dependent on the occurrence of prior historical events (e.g. random mutation) that supposedly lack counterfactual robustness. But this is no cause for concern for, as we shall see, the various explanations for idiosyncrasies are not mutually-exclusive and may work in tandem to undermine the RVL.

Furthermore, if what is meant by natural selection being contingent is that it fails to guarantee a particular outcome given certain environmental conditions, then there appears to be yet another way in which natural selection is contingent. This is because certain environmental conditions may leave open a choice of equally-as-effective design solutions (Arnold 1983 ; Beatty 2008 ). That is—on the basis of adaptive value alone, the solutions may be more-or-less indistinguishable from one another. Thus, natural selection cannot possibly favour one solution over another (whichever solution is reached must be due to non-adaptive factors). There may be multiple (equally adaptive) solutions to the same ecological problem—let us call this the Multiply Soluble Thesis (MST).

Multiple solutions to the same ecological problem

Darwin brushed past this very idea in considering the range of the orchid’s fertilisation mechanisms ( 1862 ). He noted that orchid fertilisation was facilitated by insects, but such a mechanism was, in principle, liable to lead to inbreeding which would incur substantial adverse fitness effects over time (Ibid.)—modern studies confirm this (e.g. Smithson 2006 ). At the same time, theoretical considerations stipulate that orchid fitness would increase by maximising reproduction. Thus, orchid fertilisation may be said to have (at least) two primary ecological problems: the maximisation of reproduction by cross-pollination and the avoidance of inbreeding.

But Darwin further noted that the various species of orchids were, for all intents and purposes, subjected to identical environments since they were open to visitation by the very same complement of insect species. Footnote 17 Yet orchids showed substantial diversity in their morphology in enlisting insects for cross-pollination. In the case of the Orchis mascula , there are two adhesive sacs of pollen masses suspended by thin elastic threads. The nectary of the Orchis mascula was in such a way that when an insect attempts to feed, it would undoubtedly brush past these sacs of pollen, thereby attaching the sacs to themselves, and, subsequently, bring pollen to its next destination (another Orchis mascula , perhaps). The Catasetum saccatum , on the other hand, violently launches pollen sacs downwards at insects when certain, elaborate triggers are activated. The point is that orchids exhibited multiple solutions to the same ecological problems. Footnote 18 In the modern ecological literature, this has been come to be known as the many-to-one mapping of form to function (e.g. Alfaro et al. 2004 ; Wainright et al. 2005 ; Thompson et al. 2017 ).

Losos too recognizes the idea of the MST and considers it as a candidate explanation for idiosyncrasies and, in particular, the unique evolution of the platypus. Although the environmental conditions in eastern Australia that gave rise to the platypus may be present elsewhere on Earth, the range of solutions may ultimately be underdetermined by the environmental conditions. That is—perhaps, other species with morphology distinct from the platypus could answer the same ecological demands to that of the platypus. And hence, the same form need not repeatedly evolve in the same environments. In this way, the environment-trait dyad is once again broken such that particular outcomes are no longer guaranteed by certain environments. Idiosyncrasies that are explained by the MST are opposed to the robust view of life in virtue of undermining environment-trait uniformity.

In demonstrating the MST, there are a host of empirical cases that document significant morphological diversity for the same function. For instance, Young et al. ( 2009 ) studied how a many-to-one mapping of form to function can lead to morphological diversity in shrews generating the same amount of jaw force. Similarly, the canonical stickleback studies (e.g. Wainright et al. 2005 ; Thompson et al. 2017 ) illustrate that the MST can apply selectively to feeding structures. These studies agree that the lower jaw structure of the threespine stickleback has exhibited a strong linear relationship with its function (i.e. lever ratio) or a one - to - one mapping of form to function . In other words, the MST is false for the lower jaw structure. However, two other structures of the threespine stickleback, the epaxial-buccal cavity and 4-bar structure show significant functional equivalence in their respective functions (as measured by ‘suction index’ or ‘kinematic transmission’). Thompson et al. ( 2017 ) further demonstrated that because of a many-to-one mapping of form to function, there was less repeated evolution of the latter two structures. Footnote 19 Putting aside methodological and grain issues, these studies extend plausibility to the MST.

Historicities

It is true that an explanation for idiosyncrasies based on the MST undermines the robust view of life by dissolving the environment-trait dyad. However, logically-speaking, the MST per se is not enough to entail the unique evolution of a form. Just as there is no positive reason to think that any one particular form will repeatedly evolve when there are equally adaptive alternatives (in design space), there is no positive reason to think that a different solution will arise at every evolutionary bout even when there are alternatives. Rather, there must be some reason for why it is that the same design solution was not elected even in the presence of alternatives.

This brings us to the fourth explanation for idiosyncrasies: difference-making historical events with low objective chance of occurrence. Let us call this historicities. Footnote 20 Even if there were several equally-adaptive solutions to the same ecological problem, whichever form natural selection or genetic drift produces depend upon certain preceding historical events like random mutations or their ordering. For example, if the necessary complement of genetic variation for the evolution of wings did not arise through random mutation then there can be no such evolution of wings. In this way, low probability historical events such as historicities limit the directionality of an evolutionary population’s movement through adaptive space. Alternatively, historical factors may place an evolutionary population initially closer to one peak than another and thereby, increasing its probability of climbing the closer peak.

Historicities relevant to the ECT encompass many phenomena and can be biological or non-biological. Biological historicities include ( inter alia ) random mutation, mutational order, migration events, and phylogenetic constraints due to ancestry. Certain migration events with low objective chance of occurrence such as ones prompted by volcanic eruption may result in gene flow into a population with significant outcome difference making effects. In this regard, the empirical literature has demonstrated that differential gene flow due to differential migration resulted in significant phenotypic divergences of the lake-stream stickleback (Hendry and Taylor 2004 ) and, indeed, other organisms (Hendry 2017 ).

Famously due to Gould ( 1989 ), one commonly discussed historicity in the contingency literature has been historical events that severely circumscribe downstream outcomes via the generation of phylogenetic constraints. Indeed, one principal argument in Wonderful Life (1989) was that the survivors of Cambrian extinction could have easily been otherwise such that the phylogenetic constraints (e.g. bauplan ) of our vertebrate clade, which descended from the reigning survivors of a supposedly indeterminate sampling event (i.e. Cambrian Extinction), had a low objective probability of occurrence. According to Gould (Ibid.), extant vertebrates could easily have had different body plans and hence, be markedly different. The thrust of this argument comes from the low objective probabilities of the survival events during the Cambrian such that replaying the Cambrian period would undoubtedly or, more accurately, probably result in a different surviving menagerie. In general, on account of the low probability of phylogenetic events, evolutionary systems within a modal range are probable to have different phylogenetic constraints. This is because it is, by definition, relatively improbable for the same low probability phylogenetic event to occur in more than one evolutionary system. Thus, there is a probabilistic expectation that different evolutionary systems are to have different phylogenetic constraints. And, for this reason, idiosyncrasies may result since the form is improbable to evolve again in alternative evolutionary systems.

Non-biological events include ( inter alia ) asteroid impacts, global climate change, and certain perturbations stemming from outside the evolutionary system. Despite their non-biological nature, the key is that these historical events are difference-making to the evolutionary outcome and have a low objective probability of occurrence—e.g. they are ‘chancy’, ‘stochastic’, or ‘random’. Without the latter, it is possible for the same historical events to occur ubiquitously within a modal range as for the same forms to repeatedly evolve.

An explanation of idiosyncrasies founded in historicities can undermine the environment-trait uniformity premise of the robust view of life through its interaction with natural selection: an environment fails to guarantee a specific form because certain historicities such as random mutation limited natural selection. Alternatively, the environmental regularity premise can be undermined by historicities, such as asteroid impacts or volcanic eruptions, that occur in some but not all environments, thereby introducing differences amongst environments in a modal range. That is—historicities may, sometimes, produce unique environments within a modal range (though they need not Footnote 21 ). In the former case, natural selection is limited in virtue of historicities (i.e. mutation events) whilst in the latter, an environment is unique due to historicities (i.e. asteroid impact or volcanic eruption).

Having considered the four explanations for idiosyncrasies, it is helpful to consider their effects in terms of Simpson’s ( 1944 ) adaptive landscape metaphor (not to be confused with Wright’s earlier adaptive landscape of gene frequencies ). Recall that the MST asserts that there are multiple equally-as-adaptive solutions to the same environmental problem. This can be understood as the prevalence of several equally-as-high peaks on the adaptive landscape. Footnote 22 So, one explanation for the occurrence of idiosyncrasies is that there were several adaptive peaks, each encompassing a distinct solution, on the landscape.

However, whichever peak is sought can highly depend on historical factors: either those that determined the starting conditions on the adaptive landscape or those that influence the directionality of movement (e.g. the generation of genetic variation upon which natural selection can act) across the adaptive landscape. On the adaptive landscape, if natural selection is, indeed, weak or contingent, then there is a limitation in the directionality of movement across the topographical space. In other words, the supposed hill-climbing mechanism is limited. But again, such a limitation would be ultimately due to historical events such as random mutation or drift events.

Lastly, the topography of an adaptive landscape is, itself, a manifestation of the environment. That is—the ridges and contours are determined by the environmental conditions. Hence, unique topographies correspond to unique environments. A unique environment can, then, be understood to provide a unique topography on which evolutionary forces act. All in all, the adaptive landscape metaphor is meant to emphasise that the four explanations for idiosyncrasies are not mutually-exclusive and may, sometimes, work in tandem to explain particular bouts of idiosyncrasies: even if there are many peaks, whichever adaptive solution is sought can depend on the details of natural selection and/or historical factors. Likewise, the determination of the topography (i.e. environment), itself, is sometimes dependent on the historicities.

The likelihood framework and the contingency spectrum

Thus far, I have argued that each of the four explanations of idiosyncrasies undermine at least one of two necessary premises for the robust view of life and, as such, idiosyncrasies are evidence against the robust view of life. Moreover, since the RVL and ECT are contradictory views, evolutionary idiosyncrasies also serve as evidence for the ECT. But how might we invoke idiosyncrasies as evidence in further analyses?

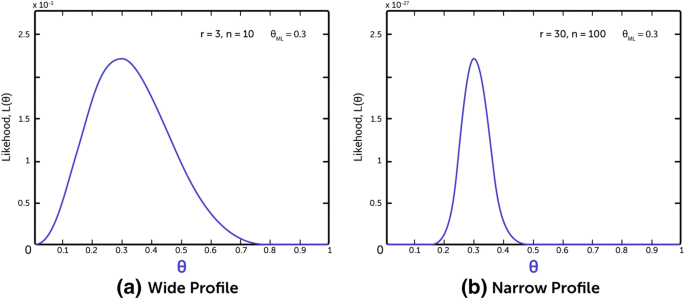

In this section, I sketch a likelihood framework in which to evaluate contingency hypotheses in light of a body of evidence. More specifically, I model the idiosyncrasy-convergence dichotomy as Bernoulli processes and I define a likelihood function that will yield, from a given a set of data (i.e. observations of idiosyncrasies vis-à-vis convergences), a likelihood distribution for all of the hypotheses on the ‘contingency spectrum’. In other words, for any given set of observations consisting of some number of idiosyncrasies and some number of convergences, one can compute the likelihood (in the technical sense) of various hypotheses that differ in the degree of contingency that they assert. Subsequently, one can also determine which hypothesis has the maximum likelihood (via maximum likelihood estimation methods Footnote 23 ). That is—even if a number of contingency hypotheses is consistent with the data, there will nonetheless be one hypothesis that confers the greatest probability on the data. And, according to the Law of Likelihood (see later), this hypothesis is one that is best evidentially supported by the data.

For the proponents of Bayesianism, one can further derive the posterior probability mass function (pmf) by applying this likelihood function to some appropriate prior distribution. Quite powerfully, this would, then, yield the conditional probability of any ECT hypothesis in light of the evidence; however, this Bayesian inference would nonetheless be severely limited by the determination of the priors (where uniformity may not be appropriate) and the quality/quantity of the data. Footnote 24 Regardless, the merit of the likelihood function stands on its own and is found in the function’s ability to produce different likelihoods for a range of hypotheses that correspondingly differ in their assertion of the degree of contingency for some modal range or domain.

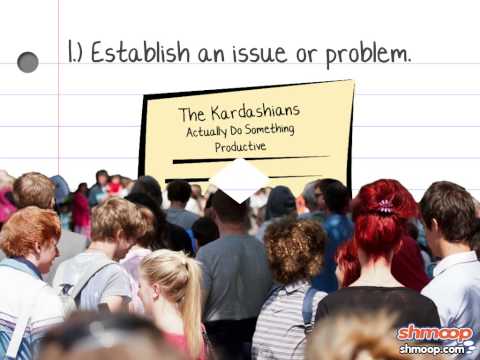

Evolutionary contingency is said to vary in degrees (e.g. Beatty 1995 , 2006 ; Powell 2012 ; Turner 2011 ). By that, it is meant that different domains may exhibit different levels of evolutionary contingency; there may be some domains where contingency reigns strongly whilst there may be other domains where robustness is the norm. In domains where contingency is strong, biological forms are less repeatable or less robust than in domains where contingency is weak. Accordingly, I submit that we can understand the RVL and ECT as extremes on the polar ends of a contingency spectrum with an infinite number of intermediary hypothesis in the middle (see Fig. 1 ).

Contingency spectrum

Recall that the ECT denies that there is any repeatability within a modal range such that all forms within that range are idiosyncrasies. Conversely, the RVL says that there is repeatability and that there are no idiosyncrasies at all. Both of these hypotheses are radical in the degree of contingency they assert and no actual contingency-theorist advocates either of them. Rather, the more plausible hypotheses lie in the intermediate, and it is just that contingency-theorists disagree on which of the intermediary hypotheses is true. As mentioned, fortunately, likelihood functions provide a means of evaluating between the various hypotheses on the spectrum—or, in other words, evaluating the strength of contingency—given some appropriate data. But what is considered appropriate data, and, furthermore, what would the data be supportive of?

The previous section showed that evolutionary idiosyncrasies are evidence against the RVL and are evidence for the ECT. It seems that idiosyncrasies point towards the ECT. However, there is a different kind of observation that seems to point in exactly the opposite direction. These are observations of ‘convergences’ which have had much discussion in the contingency literature. Roughly put, convergences are the repeated evolution of the same form from sufficiently independent taxa/species/lineages/starting points. Footnote 25 I shall reconstruct these points in probabilistic terms as to adhere with the likelihood framework. I do this by advancing two likelihood arguments to show that ‘idiosyncrasies’ evidentially favour the ECT (over the RVL), and ‘convergences’ evidentially favour the RVL (over the ECT). In other words, I shall show that (i) the probability of idiosyncrasies given the ECT is higher than the probability of idiosyncrasies given the robust view of life, and (ii) the probability of convergences given the RVL is higher than the probability of convergences given the ECT.

The first argument can be depicted in the terms of comparative likelihoods, where ‘IDIO’ refers to observations of evolutionary idiosyncrasies and ‘RVL’ refers to the robust view of life:

(IE1) Pr (IDIO | ECT) > Pr (IDIO | RVL)

If the left-hand term is greater than the right-hand term, then the likelihood ratio in favour of the ECT is above 1. Then, according to Hacking’s (1965) ‘Law of Likelihood’ or, in the form more common today (i.e. Sober 2008 ), observations of idiosyncrasies count as evidence for the ECT (over the RVL) :

Law of Likelihood Footnote 26 : An observation O evidentially supports (is in favour of) H 1 over H 2 if and only if Pr (O | H 1 ) > Pr (O | H 2 ) (Sober 2008 )

Evolutionary idiosyncrasies, as defined, are biological forms that have uniquely evolved such that they have not evolved elsewhere within the modal range. If the ECT were true of some modal range such that there is little or no repeatability within that range, it would not be a surprise that there are idiosyncrasies within that modal range. However, if the RVL were true such that there is much repeatability, then the existence of idiosyncrasies which, by definition, defy repeatability would be a surprise. Therefore, (IE1) is true, and idiosyncrasies favour the ECT over the RVL.

On the other hand, convergences or the independent origination of the same form would not be a surprise if the RVL were true. This is because the RVL stipulates that there are cases of repeated evolution of the same form within a modal range. However, if the ECT were true such that there was little or no repetition of form, then one would not expect convergences. So, IE2 is also true such that convergences favour the RVL over the ECT:

(IE2) Pr (CONV | RVL) > Pr (CONV | ECT) [‘CONV’ refers to convergences]

It is now clear which ends of the contingency spectrum, these two phenomena point towards. Observations of idiosyncrasies push us towards the right of the contingency spectrum (viz. towards the ECT), and observations of convergences should push us towards the left of the contingency spectrum (viz. towards the RVL). Footnote 27 Now, suppose that one were interested in the degree of contingency (and, a fortiori , the truth of contingency) in some domain, and had observed some number of idiosyncrasies and some number of convergences. In this case, one might ask for the comparative evidential support , by the data observed, for all of the hypotheses on the contingency spectrum. And, to answer this question, one would need to compute the likelihood of every hypothesis given the data (implicit, here, is the Law of Likelihood). This can be done by way of a likelihood function. Furthermore, one might wish also to determine which hypothesis has the greatest likelihood in which case there exists maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) methods. The thesis with the greatest likelihood is the one best supported by the evidence.

A simple likelihood function can be, without difficulty, defined under certain idealised conditions and assumptions. Footnote 28 Firstly, both observations of idiosyncrasies and convergences must occur within the same modal range . After all, evidence for or against contingency in some domain is irrelevant for evaluation of the ECT in another domain. Secondly, observations of idiosyncrasies and convergences must be commensurable. By this, I take it that, at least, idiosyncrasies and convergences must be specified at the same level of analysis and to the same scope of uniqueness. Recognising the convergence of coarse-grained trait like agricultural farming hardly counts against an idiosyncrasy about specific mechanisms of feeding structures. Thirdly, we might want to assume (for arithmetic simplicity, though we need not Footnote 29 ) that idiosyncrasies and convergences have the same ‘evidential weight’ such that one observation of idiosyncrasies counts exactly against one instance of convergences, and vice versa. That is—the difference in likelihoods of the ECT and the RVL given idiosyncrasies, and the difference in likelihoods of the RVL and ECT are identical Footnote 30 :

(Evidential Weight) Pr (IDIO | ECT) - Pr (IDIO | RVL) = Pr (CONV | RVL) – Pr (CONV | ECT)

If Evidential Weight is true, then the ECT will raise the probability of any instance of idiosyncrasies by just the same amount as the RVL will raise the probability of any instance of convergences. In other words, idiosyncrasies and convergences push towards opposite sides by, exactly, the same amount. Fourthly, we assume mutual independence between all the observations. If these four conditions hold, then a binomial likelihood function can be defined to yield a likelihood distribution. Let us define this likelihood function by way of example.

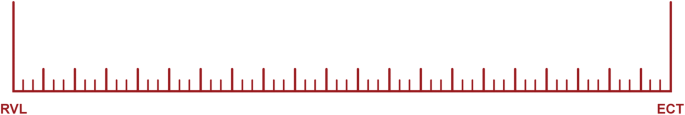

Suppose that some researchers were interested in the evolutionary contingency of the South American continent. They make a total of 100 observations that consists of 64 idiosyncrasies and 36 convergences. If we understand the sequence of idiosyncrasies and convergences as a sequence of binary events, then modelling the data as a binomial distribution is appropriate since the observations are independent Bernoulli processes. Let the sequence of events serving as our data be: x i = {x 1 ,…, X (n) }, whereby an idiosyncrasy is denoted by 1 and a convergence is denoted by 0. In our sample, the sequence might thus be coded as ‘1, 1, 0, 1, 0,… n’ such that total of 1′s is 64 and total of 0′s is 36. (Of course, there are many sequences in which the data contains 64 idiosyncrasies and 36 convergences; this is accounted for by the binomial coefficient of ‘n choose x’). The likelihood function for a binomial distribution is given by:

Likelihood Function (Binomial Distribution) :

A binomial distribution has a single parameter, θ, which, in our running example, specifies the probability of the next observation being an idiosyncrasy given the data (i.e. Pr (Idio (n) |Data) = θ). And, naturally, the probability of the next observation being a convergence would be θ C = 1 − θ. In general, this likelihood function would generate a likelihood value for θ given a body of evidence consisting of some number of idiosyncrasies versus some number of convergences. Plugging in the values from the example yields:

Likelihood Function (n = 100, 64 idiosyncrasies, 36 convergences):

This function outputs a likelihood for various θ’s ranging from 0 to 1. In other words, it tells us the likelihood of hypotheses that specify, from 0 to 1, the probability of next observation being an idiosyncrasy given the body of data. For example, the hypothesis that states that probability of the next observation being an idiosyncrasy (given the data) is 0.5 has the likelihood of 7.8861e-31. We can illustrate the function in the form of a graph (Fig. 2 ).

Likelihood distribution for 64 idiosyncrasies and 36 convergences