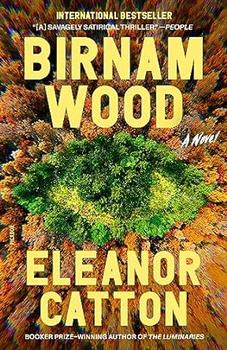

Guerrilla Gardeners Meet Billionaire Doomsayer. Hurly-Burly Ensues.

“Birnam Wood,” by the Booker Prize winner Eleanor Catton, is a fast-moving ecological novel and a generational cri de coeur.

Credit... Deena So Oteh

Supported by

- Share full article

By Dwight Garner

- Published March 13, 2023 Updated March 31, 2023

BIRNAM WOOD, by Eleanor Catton

Eleanor Catton’s third novel, “Birnam Wood,” is a big book, a sophisticated page-turner, that does something improbable: It filters anarchist, monkey-wrenching environmental politics, a generational (anti-baby boomer) cri de coeur and a downhill-racing plot through a Stoppardian sense of humor. The result is thrilling. “Birnam Wood” nearly made me laugh with pleasure. The whole thing crackles, like hair drawn through a pocket comb.

Catton, who was born in Canada, raised in New Zealand and now lives in Cambridge, England, is a prodigy. She was, at 28, the youngest-ever recipient of the Booker Prize. She won it for “ The Luminaries ” (2013), a byzantine, dry-witted novel about irascible gold prospectors and unsolved crimes on New Zealand’s South Island in 1866. She is also the author of “ The Rehearsal ” (2008), a much slimmer novel, about a relationship between a male teacher and a student at an all-girls high school.

Catton has felt like the real thing out of the gate. One reason is her way with dialogue. Her characters are almost disastrously candid. They talk the way real people talk, but they’re freer, ruder, funnier. Alongside the wordplay and in-jokes, and the topping of those jokes, unexpected abrasions pile up. You sense the world being thrashed out in front of your eyes.

Another reason is her knowingness — her thinginess. Catton is at home in the physical world, and her details land. (In “Birnam Wood” her scrimping gardeners strew hair-salon clippings as slug repellent.) Her books move sure-footedly, as if on gravel paths, between microclimates.

Finally, there is Catton’s generosity, to her characters and to her readers. She turns her men and women around and around in appraisal, allowing the available light to alternately flatter and roast them. Even the venal clods burst to complicated life. Catton resembles one of those teachers who can take a student’s simple-minded question and, without condescending, shape it into an ingenious one. She’s generous to her readers because, in the manner of Iris Murdoch or John Fowles (at his best), writers to whom she deserves to be compared, her philosophical predisposition doesn’t dim her relish for pure plot, for blood-warm suspense. The bullets really fly in “Birnam Wood.” The big explosion will probably go off. Greta Gerwig could film this novel, but so could Quentin Tarantino.

Catton’s title is from Shakespeare: “Macbeth shall never vanquished be until Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill shall come against him.” Here it’s the name of a guerrilla gardening collective that sometimes legally, and sometimes less so, cultivates wherever it can, “along verges and fence lines, beside motorway offramps, inside demolition sites and in junkyards filled with abandoned cars.”

“Why Are You on Facebook?” is the title of one of Van Morrison’s nutty recent songs. The question isn’t a bad one, though. The Birnam Wood collective makes sure its apolitical Facebook page is sunny and welcoming. It posts a daily gardening tip. This is part of its front for the fact that some members — a few are described as “crust punks” — do a bit more than trespass.

They took cuttings from suburban gardens, leaf litter out of public parks and manure from farmland. Mira had stolen scions from commercial apple orchards — budding whips of Braeburn and Royal Gala that she grafted to the stocks of sour crab-apple trees — and equipment out of unlocked garden sheds, though only, she insisted, in wealthy neighborhoods, and only those tools that did not seem to be in frequent use.

The idealistic members yearn for widespread, lasting social change. They want people to see how much fertile land goes to waste. It’s 2017 and the populists and privatizers, even in New Zealand, are sweeping into power. Birnam Wood has this cockeyed, D.I.Y. notion that people, and nations, could do vastly more to pool their resources.

We get to know three of Birnam Wood’s members well. The alpha is Mira, the group’s founder. She’s 29 and a horticulturist by training. Mira is broke and a bundle of nerves; she has feral qualities but longs for a rural authenticity she senses she lacks. She got into gardening for the same reason some of us got into reading: “It offered a respite from this habit of relentless interior critique.” She’s lost in a complicated, funny way, as if, morally, she’s trying to find her eyeglasses while she’s wearing them.

Then there’s Shelley, Mira’s best friend. Shelley is skeptical and sane and has a self-deprecating sense of humor. She’s the closest thing this book has to a reader’s representative and the only load-bearing wall, at least at the start, that doesn’t seem off plumb. Shelley is forbearance personified but she’s tired of being taken by Mira “for a dogsbody, a beta fish, a bridesmaid, a ride-along.” The sleeve of her good will has begun to fray. She’s aching to leave the collective, and she may not be as sensible as we think she is.

Finally, there’s Tony, a mansplaining Bernie bro (his detractors say) with a master’s in “critiquing the anti-humanism of post-structuralist political thought.” He’s as cultivatedly shaggy, and as appalled by capitalism, as only a trust-fund kid can be. He probably works himself up with Temple of the Dog’s anthem “ Hunger Strike ” on loop in his earbuds.

Tony has returned to Birnam Wood after several years traveling and finding himself in activism. He and Mira almost had a little thing once. Now Tony wants to be a blogger, or a podcaster, or a journalist of some sort. “A scoop is better than sex,” the late blogger Nikki Finke used to say. Before long, Tony has stumbled onto the scoop of a lifetime. Either that, or he’s got the journalistic equivalent of a nasty wad of gum in his hair.

The story involves an inscrutable American billionaire named Robert Lemoine who flies his own planes and wears designer tracksuits, a bit like Bobby Axelrod in “Billions.” He’s made his money in high-tech drones, a fact that feeds this book’s obsession with surveillance. “Birnam Wood” will make you want to attend, as Tony has done, a digital obfuscation workshop.

Lemoine is a doomsteader. He is sinking an elaborate bunker into the ground on a big tract of rural land he’s purchasing. New Zealand is, as similar billionaires know, in the middle of nowhere — on the part of a world map where “reverse” is on a gear shift, as John Updike wrote in a 1983 short story .

The Birnam Wood collective and Lemoine meet with a jolt when he catches Mira on his new property scouting for land to cultivate. They end up liking each other; they’re both outlaws; they find each other spicy. Lemoine proposes investing in Birnam Wood, the first real money the collective has ever seen. For him it’s moral cover. For Birnam Wood, getting into bed with a rapacious billionaire drone maker is a crisis.

Tony is outraged. (Tony is always outraged.) The more he looks into Lemoine and his plans, and his gift for purging his foes, the stranger everything begins to seem. To give away more would be to ruin a story that sails as if on a magic carpet, or a fleet of quadcopter drones.

“Birnam Wood” is an ardent ecological novel, but it’s not a softheaded one. That’s another reason it’s a rarity. I sometimes feel that if I must read even one more wet novel that argues courageously, in the teeth of its audience’s predilections, in favor of trees and moss and sunshine, I will pluck out my eyes.

It has resonances with two recent novels that escape this fate — Nell Zink’s “Avalon,” in which characters employ criminal gardening tactics, and Allegra Hyde’s “Eleutheria,” about a utopian compound on a tropical island.

Catton’s novel takes place, as do all novels in 2023, under skies thrice poisoned — by greenhouse gasses, by crisscrossing drones and by a moon we’ve littered with golf balls. Lower to the ground, Tony will discover, is an excremental flow of chemicals, leading to a bigger discovery.

Writing a novel is not unlike tending a garden, and “Birnam Wood” becomes a kind of serpentine pastoral. Catton has a naturalist’s eye, and she traces her character’s streams of perception when their fingers are in the dirt, tinkering with the photosynthesizing world:

Even in her failures and mistakes — as when she learned that onion seeds don’t tend to keep, or that low soil temperatures result in carrots that are pale, or that fennel inhibits growth in other plants and should be propagated only on its own — she never felt chastised, for truth, in a garden, did not take the form of rectitude, and right was not the opposite of wrong. To learn even something as simple as to water the roots of a plant rather than its leaves was not to be dealt the harsh reality of a cold hard fact, but rather to be let into a secret. In a garden, expertise was personal and anecdotal — it was allegorical — it was ancient — it had been handed down; one felt that gardeners across generations were united in a kind of guild.

“Birnam Wood” is also very much of its moment: Like a refreshed “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” it’s all laptops and cycle helmets. You will learn more here about thermal imaging, drone evasion, burner applications and the raiding of other people’s browser histories, to name but four things, than you thought possible. This is also an intimate novel about female friendship that dips into the things that keep one up at night, the national character of New Zealand, hangovers and dinner parties and microdosing.

At a few moments you sense the clanking of plot in “Birnam Wood.” Some late scenarios are implausible. But the pop novel that lurks inside this wise work already has you on the hook.

Catton gives Tony, the Bernie bro, his jeremiads, some of which are woozily inspiring. He can get pretty lathered up about a lot of things, including “the utter shamelessness with which his natural inheritance, his future , had been either sold or laid to waste by his parents’ generation, trapping him in a perpetual adolescence that was further heightened by the infantilizing unreality of the internet as it encroached upon, and colonized, real life — ‘real life,’ Tony thought, with bitter air quotes.”

Reflexively, Catton takes the moral wind out of him at the same time. As the plot in “Birnam Wood” really kicks into gear, as everything begins to converge, Tony says to himself: “I am going to be so [expletive] famous.”

BIRNAM WOOD | By Eleanor Catton | 424 pp. | Farrar, Straus & Giroux | $28

Dwight Garner has been a book critic for The Times since 2008. His most recent book is “Garner’s Quotations: A Modern Miscellany.” More about Dwight Garner

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, “Knife,” addresses the attack that maimed him in 2022, and pays tribute to his wife who saw him through .

Recent books by Allen Bratton, Daniel Lefferts and Garrard Conley depict gay Christian characters not usually seen in queer literature.

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Advertisement

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

Eco-idealism and staggering wealth meet in 'birnam wood'.

John Powers

Ever since Ursula K. Le Guin and Edward Abbey lit the fuse back in the 1970s, there's been an ever-growing explosion of political eco-fiction. From Octavia Butler and Richard Powers to Amitav Ghosh and Margaret Atwood , novelists have gotten more and more fascinated with those who fight to save the environment.

One such group occupies the center of Birnam Wood , the whooshingly enjoyable new novel by Eleanor Catton , a New Zealander whose previous book, The Luminaries , made her, at 28, still the youngest person ever to win the Booker Prize. Where that 2013 novel was a wild-and-woolly beast, Birnam Wood — its title comes from Macbeth — is shapelier and more conventional. Filled with utopian hopes, personal betrayals, accidental deaths and profoundly unaccidental murders, this New Zealand-set book is a witty literary thriller about the collision between eco-idealism and staggering wealth.

The story begins by introducing three 20-something members of Birnam Wood, a guerrilla collective that seeks to fight capitalism and ecological devastation by, legally or not, growing things on unplanted land, public and private. There's Mira, the group's willful and charismatic founder. There's her burnt-out sidekick, Shelley, who does the grunt work and secretly wants to quit the group. And then there's Tony, the most radical thinker of the bunch who has returned to the group after several years abroad. He has romantic hopes for himself and Mira — hopes that Shelley quietly hopes to sink.

Mira hears about an unoccupied farm owned by Sir Owen Darvish and his wife Jill, who embody the solidity and complacency of well-off Kiwis. Mira thinks it perfect for a Birnam Wood project. But when she drives there from Christchurch, she discovers that it's been bought by Robert Lemoine, an elusive American billionaire/drone manufacturer who says he plans to build a survivalist bunker. Attracted to Mira, Lemoine offers to help finance Birnam Wood. Because her group badly needs money, she's interested. But will a rich benefactor's money help the group spread its message — or corrupt it?

The Two-Way

Book news: eleanor catton is the youngest-ever booker winner.

While Catton has sympathy for the grand idealism of the Birnam Wood collective, she also sees its fault lines. Indeed, the book's at its best taking us inside the characters' heads to lay bare the illusions, desires and petty motivations that often work against their dreams. For instance, Mira emerges as something of a modern-day version of Jane Austen 's Emma — Catton actually scripted a 2020 film adaptation of that novel. Mira's sense of political righteousness blinds her to her own motivations. The disaffected Shelley accuses her of "rebelling for the sake of it, like she had always done, acting as though the rules that bound the little people were just too tiresome and ordinary to apply to her."

Working in the tradition of the 19th-century novel — one hears echoes of George Eliot as well as Austen — Catton likes to confront her characters with choices and then lay bare the consequences, often unintended, of what they've chosen. There's a great, lacerating scene in which Tony, a world-class mansplainer, falls out of favor with the group by attacking identity politics and intersectionality. Because of this split, he will wind up spying on Lemoine — a move that sends the plot caroming in a wild new direction.

You see, while our heroes in the collective are muddling their way through ordinary human issues, they're faced with a villain from a 21st-century thriller. Lemoine isn't merely an amoral billionaire with all the compassion of one of his drones. He's a high-tech bad guy, complete with NSA-level spyware and mercenaries to do his bidding. Too bad to be true, he's so skillful at wielding his malignancy that, in spite of herself, Catton seems to hold him in a kind of awe.

Normally, it would be an artistic flaw that realistic characters like Mira, Shelley, Tony and the Darvishes must confront such a comic-book baddie, and I guess it is here: What starts off looking like a novel about character winds up in a climax out of a genre novel. Yet the story plays like gangbusters: I devoured all 400-plus pages in two days.

And in showing the collective's encounter with Lemoine, Catton taps into a feeling very much of our moment. We live at a time when many environmentalists feel helpless next to mega-rich forces who seem able to despoil the planet as they wish and to avoid any governmental attempts to check them. In Birnam Wood , we see the consequences of this gap in power, and the results are not pretty.

Birnam Wood

Eleanor catton.

432 pages, Hardcover

First published March 2, 2023

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

…all the great tragedies are stories ultimately of betrayal. They’re stories where people betrayed the people closest to them but they're also stories where people betray themselves. They kind of betrayed the better person that they could have become. – B&N interview

Third Apparition – Macbeth shall never vanquish’d be until Great Birnam wood to high Dunsiname hill Shall come against him. Macbeth – That will never be. Who can impress the forest, bid the tree Unfix his earth-bound root? - The Scottish Play

…the yellow circle labelled ‘Mira’ pulled out into the street and began traversing slowly north. Shelley Noakes reduced the scale of the map until her own circle, a gently pulsing blue, appeared at the edge of the screen, and watched the yellow disc advance imperceptibly upon the blue for almost thirty seconds before turning off the phone and throwing it, suddenly and childishly, into the pile of laundry at the end of her bed.

Shelley wanted out. Out of the group; out of the suffocating moral censure, the pretended fellow feeling, the constant obligatory thrift; out of financial peril; out of the flat; out of her relationship with Mira, which was not romantic in any physical sense, but which had somehow come to feel both exclusive and proprietary; and above all, out of her role as the sensible, dependable, predictable sidekick, never quite as rebellious as Mira, never quite as free-thinking, never – even when they acted together – quite as brave.

[Catton] drew up another intricate masterplan in which each of the main characters could be seen as Macbeth, with a corresponding Lady Macbeth, witches and so on. It sounds tricksier than it is: as the narrative perspective shifts, everybody could be the villain. She wanted to stop readers playing “the polarised blame game we are all used to in contemporary politics,” she explains. “You wouldn’t be able to say: ‘These are my people so they are obviously the good guys. These are the people that I despise so they are obviously the bad guys.’” - from The Guardian interview

It’s something I have thought about a lot…how my generational placement or position has conditioned me. The book is designed generationally. There are three generations represented in terms of the points of view. And I wanted to really explore the generational differences in terms of how they deal with certain contemporary problems that we’re all kind of facing globally. - from The Toronto Public Library interview

“Millennials are quite willing to cosy up to the tech gen Xers,” she says. “We are all personally enriching billionaires like Elon Musk by freely giving away our data…These minerals are in the phones that are around us all the time. I want my iPhone. I want to be able to have the freedoms that it brings. We are all complicit.” - from The Guardian interview

Macbeth is a play that's all about prophecy. It's animated by prophecy. So I …re-read it with everything that was happening in terms of world events resounding in my head and suddenly saw it in a really different way, as a play that contains very interesting and loud warnings about what happens when you regard the future with too much certainty if you're too convinced about what lies just down the road. Because of course Macbeth makes the ending of Macbeth happen. None of that was written on the wall before before he received those prophecies and I and so I kind of wanted to achieve a similar effect in a novel by writing a book about incremental political actions and moral actions that end up kind of having these enormous effects that were avoidable. - from the Barnes & Noble interview

Like all self-mythologising rebels, Mira preferred enemies to rivals, and often turned her rivals into enemies, the better to disdain them as secret agents of the status quo.

Eleanor Catton MNZM (born 1985) is a New Zealand novelist and screenwriter. Born in Canada, Catton moved to New Zealand as a child and grew up in Christchurch. She completed a master's degree in creative writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters. Her award-winning debut novel, The Rehearsal , written as her Master's thesis, was published in 2008, and has been adapted into a 2016 film of the same name. Her second novel, The Luminaries , won the 2013 Booker Prize, making Catton the youngest author ever to win the prize (at age 28) and only the second New Zealander. It was subsequently adapted into a television miniseries, with Catton as screenwriter. In 2023, she was named on the Granta Best of Young British Novelists list.

…her next work, “a queasy immersion thriller” that will be called Doubtful Sound, after the remote fjord in the south-west of New Zealand where it is set. She has had the title for a long time – “I just think it is so beautiful” – but it was only in the final months of completing Birnam Wood that the story came to her. - from The Guardian interview

A new vocabulary had come into force: Birnam Wood was now a start-up, a pop-up, the brainchild of “creatives”; it was organic, it was local; it was a bit like Uber; it was a bit like Airbnb. In this new, perpetually unsettled climate, Shelley’s defection from the conventional economy had gained, she knew, a kind of retroactive valour, and even Mira — seditious, independent-minded Mira — suddenly seemed to be just the sort of trendy big-talking renegade one could imagine being contracted by the government as a black-ops adviser, writing inflammatory blogs and newspaper columns that defended unorthodox opinions and debated the right to free speech. Agitation had lost its juvenile cast: it had been made urgent again, righteous again, necessary again. An aura of prescience now permeated Birnam Wood.

Between the press coverage of the knighthood and the reporting on the landslide on the pass, Thorndike had been much in the public consciousness in recent months, and if Birnam Wood could stage a demonstration on the Darvish property, Mira thought — if they could arrange to be caught in the act of trespassing — if they could invite prosecution, even, for the alleged crime of planting a sustainable organic garden on an empty tract of land — and if they could then present to the media exactly what they’d planted, and explain their mission, and enumerate their goals, and prove themselves to be serious and good-hearted professionals whose work was tidy, and efficient, and fruitful, and thoughtful, and respectful of the land — would that not be a form of breaking good? They would risk criminal charges, of course, but at least they’d get their message out. And since Owen Darvish was to be knighted for services to conservation, at the very least they might provoke an interesting debate.

Forget the bunker, forget everything he’d planned to write about survivalism, and growth hacking, and techno-futurism, and imperial-stage-capitalist decline, and New Zealand’s pathetically obsequious courting of the superrich. Forget all of that. This was his story. He couldn’t quite see the whole picture yet — but a picture was undoubtedly forming. Whatever was going on in Korowai was going on in secret, and he, Tony Gallo, Anthony Gallo, was going to be the one to flush it out.

“So anyway,” Shelley went on, “this is what I was thinking: that, like, the real choices that you make in your life, the really difficult, defining choices, are never between what’s right and what’s easy. They’re between what’s wrong and what’s hard.”

THIRD APPARITION MACBETH

Be lion-mettled, proud; and take no care Who chafes, who frets, or where conspirers are: Macbeth shall never be vanquish'd be until Great Birnam wood to high Dunsinane hill Shall come against him. That will never be, Who can impress the forest, bid the trees Unfix his earth-bound root?

“one of the reasons that horticulture held such strong appeal for mira was that it offered her a respite from this habit of relentless interior critique. when she made things grow, she experienced a kind of manifest forgiveness, an abiding moving-on and making-new that she found impossible in almost every other sphere of life.”

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2023

Kirkus Prize finalist

BIRNAM WOOD

by Eleanor Catton ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 7, 2023

This blistering look at the horrors of late capitalism manages to also be a wildly fun read.

An eco-activist group in New Zealand becomes entangled with an American billionaire in Catton's first novel since the Booker Prize–winning The Luminaries (2013).

Mira Bunting is the brainchild behind Birnam Wood, an “activist collective” of guerrilla gardeners who plant on unused land (sometimes with permission) and scavenge (or steal) materials to grow food. Mira is a “self-mythologising rebel” whose passions are tempered only somewhat by Shelley Noakes, who sees herself as Mira’s “sensible, dependable, predictable sidekick.” This role is starting to chafe—as is the lack of money—and Shelley plans to leave Birnam Wood. Just as Shelley’s about to cut ties, Mira makes an announcement: On a recent scouting trip near Korowai National Park, she located a farming property owned by a Kiwi farmer named Owen Darvish, temporarily abandoned due to a recent earthquake. This land is soon to transfer ownership from Darvish to an uber-rich tech CEO looking for a spot to doomstead. When the businessman, Robert Lemoine, catches Mira scouting on the land, he offers to bankroll the group to the tune of $100,000 since the act will help his bid for New Zealand citizenship. What could go wrong? Catton swirls among perspectives, including those of Mira, Shelley, Lemoine, Darvish and his wife, and a former Birnam Wood member called Tony, whose aspirations to fame look within reach as he suspects he’s got a major scoop concerning Lemoine’s real motives. In many ways, the novel is as saturated with moral scrutiny and propulsive plotting as 19th-century greats; it's a twisty thriller via Charles Dickens, only with drones. But where Dickens, say, revels in exposing moral bankruptcy, Catton is more interested in the ways everyone is cloudy-eyed with their own hubris in different ways. The result is a story that’s suspended on a tightrope just above nihilism, and readers will hold their breath until the last page to see whether Catton will fall.

Pub Date: March 7, 2023

ISBN: 9780374110338

Page Count: 432

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Review Posted Online: Dec. 23, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 15, 2023

LITERARY FICTION | THRILLER | PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLER | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | GENERAL FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Eleanor Catton

BOOK REVIEW

by Eleanor Catton

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

by Percival Everett ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 19, 2024

One of the noblest characters in American literature gets a novel worthy of him.

Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as told from the perspective of a more resourceful and contemplative Jim than the one you remember.

This isn’t the first novel to reimagine Twain’s 1885 masterpiece, but the audacious and prolific Everett dives into the very heart of Twain’s epochal odyssey, shifting the central viewpoint from that of the unschooled, often credulous, but basically good-hearted Huck to the more enigmatic and heroic Jim, the Black slave with whom the boy escapes via raft on the Mississippi River. As in the original, the threat of Jim’s being sold “down the river” and separated from his wife and daughter compels him to run away while figuring out what to do next. He's soon joined by Huck, who has faked his own death to get away from an abusive father, ramping up Jim’s panic. “Huck was supposedly murdered and I’d just run away,” Jim thinks. “Who did I think they would suspect of the heinous crime?” That Jim can, as he puts it, “[do] the math” on his predicament suggests how different Everett’s version is from Twain’s. First and foremost, there's the matter of the Black dialect Twain used to depict the speech of Jim and other Black characters—which, for many contemporary readers, hinders their enjoyment of his novel. In Everett’s telling, the dialect is a put-on, a manner of concealment, and a tactic for survival. “White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them,” Jim explains. He also discloses that, in violation of custom and law, he learned to read the books in Judge Thatcher’s library, including Voltaire and John Locke, both of whom, in dreams and delirium, Jim finds himself debating about human rights and his own humanity. With and without Huck, Jim undergoes dangerous tribulations and hairbreadth escapes in an antebellum wilderness that’s much grimmer and bloodier than Twain’s. There’s also a revelation toward the end that, however stunning to devoted readers of the original, makes perfect sense.

Pub Date: March 19, 2024

ISBN: 9780385550369

Page Count: 320

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: Dec. 16, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 15, 2024

LITERARY FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION | GENERAL FICTION

More by Percival Everett

by Percival Everett

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2022

New York Times Bestseller

Pulitzer Prize Winner

DEMON COPPERHEAD

by Barbara Kingsolver ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 18, 2022

An angry, powerful book seething with love and outrage for a community too often stereotyped or ignored.

Inspired by David Copperfield , Kingsolver crafts a 21st-century coming-of-age story set in America’s hard-pressed rural South.

It’s not necessary to have read Dickens’ famous novel to appreciate Kingsolver’s absorbing tale, but those who have will savor the tough-minded changes she rings on his Victorian sentimentality while affirming his stinging critique of a heartless society. Our soon-to-be orphaned narrator’s mother is a substance-abusing teenage single mom who checks out via OD on his 11th birthday, and Demon’s cynical, wised-up voice is light-years removed from David Copperfield’s earnest tone. Yet readers also see the yearning for love and wells of compassion hidden beneath his self-protective exterior. Like pretty much everyone else in Lee County, Virginia, hollowed out economically by the coal and tobacco industries, he sees himself as someone with no prospects and little worth. One of Kingsolver’s major themes, hit a little too insistently, is the contempt felt by participants in the modern capitalist economy for those rooted in older ways of life. More nuanced and emotionally engaging is Demon’s fierce attachment to his home ground, a place where he is known and supported, tested to the breaking point as the opiate epidemic engulfs it. Kingsolver’s ferocious indictment of the pharmaceutical industry, angrily stated by a local girl who has become a nurse, is in the best Dickensian tradition, and Demon gives a harrowing account of his descent into addiction with his beloved Dori (as naïve as Dickens’ Dora in her own screwed-up way). Does knowledge offer a way out of this sinkhole? A committed teacher tries to enlighten Demon’s seventh grade class about how the resource-rich countryside was pillaged and abandoned, but Kingsolver doesn’t air-brush his students’ dismissal of this history or the prejudice encountered by this African American outsider and his White wife. She is an art teacher who guides Demon toward self-expression, just as his friend Tommy provokes his dawning understanding of how their world has been shaped by outside forces and what he might be able to do about it.

Pub Date: Oct. 18, 2022

ISBN: 978-0-06-325-1922

Page Count: 560

Publisher: Harper/HarperCollins

Review Posted Online: July 13, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 1, 2022

LITERARY FICTION | GENERAL FICTION

More by Barbara Kingsolver

by Barbara Kingsolver

SEEN & HEARD

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

clock This article was published more than 1 year ago

In Eleanor Catton’s ‘Birnam Wood,’ the end of the world creeps up fast

In the booker winner’s novel, a u.s. billionaire and a band of radical gardeners spin a deadly plan on a remote plot of land in new zealand.

Ten years ago, Eleanor Catton soared up from Down Under to grab the Booker Prize . At 28, the New Zealand author was the youngest-ever winner, and at 832 pages, “ The Luminaries ” was the longest. A notoriously complicated historical mystery about the gold rush involving multiple narrators plotted across astrological charts, “The Luminaries” dazzled — and intimidated — readers around the world.

Fans might assume Catton has spent the last decade concocting something even more gargantuan and byzantine. But her new novel, “ Birnam Wood ,” is a sleek contemporary thriller. Still, it’s not so much a change of tack as a demonstration that Catton is a master at adapting literary forms to her own sly purposes. (Indeed, in 2020, you may have seen her arch adaptation of “Emma,” starring Anya Taylor-Joy .)

“Birnam Wood” opens with “a spate of shallow earthquakes” in a remote part of New Zealand, but by the end those tremors will reverberate across the planet. The title, aside from being a prophetic allusion to “Macbeth,” is the name of an obscure environmental group. The members of Birnam Wood are guerrilla gardeners, who raise vegetables on public land and unattended private property, sometimes with permission, sometimes without. While they might think of themselves as fearless revolutionaries, their antics rarely extend much beyond stealing a hoe from a wealthy neighbor’s garden shed.

Nevertheless, Mira, the de facto leader of this supposedly leaderless collective, dreams of “nothing less than radical, widespread, and lasting social change, which would be entirely achievable, she was convinced, if only people could be made to see how much fertile land was going begging, all around them, every day.” In the words of Mao, “Let a hundred flowers bloom,” but make sure they’re peas, tomatoes and cucumbers.

Review: ‘The Luminaries,’ by Eleanor Catton

As the novel opens, Mira spies a potentially rich new target. A landslide has buried a stretch of highway, almost completely cutting off the town of Thorndike and canceling development of a 375-acre plot abutting a national park. What better place for Mira’s merry band of subversive farmers to till the soil in relative secrecy! If they get arrested, even better: The publicity will amplify their cause.

The only problem is that this land has already caught the attention of Robert Lemoine, an American billionaire. He plans to construct a luxurious bunker here where he can, when the moment arrives, wait out the apocalypse. In her characteristically athletic style, which flexes from fury to parody, Catton describes Lemoine as “a far-sighted, short-selling, risk-embracing kleptocrat, an incarnation of unapologetic zero-sum self-interest, a radical misfit, a ‘builder’ in the Randian sense, a genius, a tyrant, an obsessive, a prophet, a status-symbol survivalist hedging his bets against any number of potential global catastrophes that he himself was doing absolutely nothing to prevent, and might even be taking active measures to encourage if there was a profit to be made, or an advantage to be gained, in the pursuit.”

He’s also a liar.

The moment Lemoine spots Mira snooping around this land, they both begin trying to deceive each other, but it’s not a fair match. Equipped with a vast array of spyware and surveillance drones, Lemoine thinks he can use these scruffy environmentalists, while Mira imagines that his $100,000 donation will finally make Birnam Wood a success — without contaminating the group’s principles.

Clearly, something else, bigger and far more nefarious, is going on.

Deep beneath this rich soil — and layers of deceit — lie a trillion dollars worth of rare-earth elements. Just as the 19th century revolved around fantasies of buried gold, the 21st is obsessed with these valuable minerals. With fantastical names like lanthanides, scandium and yttrium, rare-earth elements play a crucial role in renewable-energy technology, which may be our best hope for avoiding catastrophic global warming. Two of the many essential questions “Birnam Wood” raises are who will control those minerals, and how will they be extracted without inflicting even more environmental damage?

Sign up for the Book World newsletter

The billionaire and the gardeners would seem to be moral opposites, but Catton writes with a satiric edge that leaves no survivors. In fact, she’s most incisive when it comes to the members of the Birnam Wood co-op. As a narrator, she demonstrates a kind of vicious sympathy, hitching a ride along with their thoughts while poking a stick in their spokes. Mira and her friends are intimately drawn portraits of liberal narcissism and naivete. “Like all self-mythologising rebels,” Catton writes, “Mira preferred enemies to rivals, and often turned her rivals into enemies, the better to disdain them as secret agents of the status quo.” Along with vegetables, these privileged young people find plenty of time to sow their own anxieties and reap a bumper crop of conflicts within their pious group of recyclers and scavengers.

Catton has somewhat less success bringing that level of verisimilitude to Lemoine, although she’s wonderfully attentive to the atmospheric disturbance created around her brash billionaire. Perhaps the truly super-rich are so unfettered by reality that the dimensions of ordinary life aren’t relevant, but Lemoine comes off at times more like a swaggering cartoon villain than a man enmeshed in the infinite details of a vast financial empire. He’s the kind of character who says things like, “I’m a billionaire. Money is not an issue for me,” a line so silly that it momentarily shifts these pages into primary colors.

But that feels like a minor distraction in a novel that dramatizes political, technical and environmental crises with such delicious wit. And once an accidental death upsets everyone’s competing machinations, readers are unlikely to notice anything except the story’s acceleration toward ever more toil and trouble. With terrifying intensity, Catton propels these characters to a finale that prefigures the very apocalypse they’re all trying to forestall. It’s a wry indictment of all the poor players who strut and fret their hours upon this stage and then are heard no more.

Ron Charles reviews books and writes the Book Club newsletter for The Washington Post.

Birnam Wood

By Eleanor Catton

Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 432 pp. $28

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Eleanor Catton Wants Plot to Matter Again

By B. D. McClay

Toward the end of “Birnam Wood” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), the latest novel from the New Zealand writer Eleanor Catton, Rosie Demarney, an otherwise minor character, gets a moment in the spotlight. She has been presented with a series of facts that seem to add up to a humiliating conclusion: the guy she likes has blown her off to pursue an old flame. Her fears are only confirmed by the embarrassed gaze of her crush’s sister. At home, clinging to her self-respect by a thread, Rosie firmly tells herself that she “was not going to play the role that he had cast her in; she was not going to spend the evening in her sweatpants, getting drunk and stalking him pathetically online.” A beat, a line break, and then the inevitable: “But hell. Nobody was watching.”

By now, if readers of “Birnam Wood” have learned one thing, it’s that someone is always watching. Whether people are being spied on by the modern technologies of surveillance (Google, G.P.S., cell phones, drones, social media) or by the more ancient techniques of intimacy (marriage, friendship, family, gossip), they are never afforded the luxury of a purely private action, or of avoiding the roles that others have written for them.

“Birnam Wood” opens with a seemingly impersonal catastrophe: a landslide in New Zealand kills five people. From this disaster a complex and often shocking sequence of events unfolds. The Darvishes, the owners of a large farm near the accident, withdraw it from sale; this withdrawal comes to the attention of Mira Bunting, “aged twenty-nine, a horticulturalist by training, and the founder of an activist collective known among its members as Birnam Wood.” Mira had previously inquired about the listing under a false identity, and she decides to visit: Birnam Wood illegally plants gardens on unused land, and the farm seems an ideal target for expansion. While trespassing on the grounds, she meets a curt American stranger who knows too much about her, including her name. He is Robert Lemoine, the billionaire co-founder of Autonomo, a drone manufacturer.

He is also, as we quickly learn, though Mira does not, responsible for the landslide. It doesn’t trouble him much. “Five dead, in the scheme of things, was basically no dead at all,” he thinks. Lemoine is in New Zealand pretending to build a covert apocalypse bunker; to this end, he is purchasing the Darvish farm under conditions of total secrecy, so secret that the estate must seem not to be for sale at all. But his actual aims are much darker: Korowai, the national park that sits beside the farm, possesses rare-earth minerals, which if extracted will make Lemoine “the richest person who had ever lived.” In Mira, Lemoine sees a kindred spirit, but also a dupe. He can use Birnam Wood as another smoke screen, a way to launder his presence through a local, eco-friendly organization. He offers Mira access to the farm and a hundred thousand dollars, suspecting, correctly, that she’ll find both the financial security and his shadowy mystique irresistible.

Discover notable new fiction and nonfiction.

Much like the moment in pool when the cue ball breaks up the carefully assembled triangle, this encounter between Mira and Lemoine ends up affecting every other character in the book, even those who have no reason to know one another. The choices they make, to use and to be used, reverberate in ways you might expect only if the image of the five crushed landslide victims lingers as you read. All of the book’s major players get a chance to turn the tide of events in their favor. Shelley Noakes, Mira’s best friend and roommate, is stealthily seeking a way out of the collective, tired of playing the steady foil to her more volatile friend. The Darvishes—Sir Owen and his wife, Lady Darvish—view Lemoine’s incredible wealth with a mixture of disgust, awe, and desire, even as they conduct business with him. And, finally, there’s Tony Gallo, Rosie’s love interest, Mira’s ex- something , and a former member of Birnam Wood, who, in a paroxysm of barely sublimated sexual jealousy, has decided to write an exposé of Lemoine, and in so doing stumbles upon Lemoine’s mining operation.

All of these people think that, with a little luck, they can manipulate another party to their advantage—even when they know that the others think the same of them, even when they are plotting betrayals on the fly, even when some of their plans are immediate and abject failures. (When Shelley first encounters Tony, she thinks that he presents an easy way to end her friendship with Mira: she will simply seduce him. She does not succeed.) Like Rosie, they have no intention of merely playing a role that somebody else wrote for them. And, like Rosie, they end up doing it anyway.

We do not live in the golden age of plot, at least where literary fiction is concerned. Outside of what we might call high-genre books—the thrillers of Ruth Rendell, say, or the crime novels of Tana French—it’s rare for a literary novel to take its plot seriously. Instead, contemporary literary fiction largely concerns itself with other things: moods, problems, situations. Few people would dream of writing a novel without characters, but a novel without a plot is practically normal. When you speak of what a novel is about, you speak thematically—it’s about surveillance, or displacement, or heterosexuality, or something along these lines.

In a recent interview, Catton commented, somewhat blandly, that “the moral development of people in plotted novels where people make choices is fascinating and important. I’d like to see more books like that.” Her interest in plot as something that arises from human choice, and not just from the context in which those choices take place, means that her own plots take a sideways approach. Just as we are constantly summing up books as types, the characters in “Birnam Wood” are constantly summing up one another, often incorrectly. When Shelley tries to seduce Tony—who, after a sojourn in Mexico, had completely forgotten that she existed—he is overwhelmed by their similarities, “astonished that he could ever have forgotten someone so thoroughly simpatico as Shelley Noakes.” Catton adds, in a rare direct address to the audience:

It never crossed his mind that since she had not forgotten him , the personality that she revealed to him might very easily have been customised, the opinions tailored, the résumé adapted, to suit what she remembered of his interests and his taste; never dreaming that she might be flirting with him, he reflected only that there was something appealingly familiar in her candid warmth and air of frank and ready capability.

One of Catton’s favorite moves is to conclude a scene from one character’s perspective only to start the next scene from the perspective of an adjacent character—someone whom the first character got slightly wrong. Shelley’s frantic musing about how to confess to Mira her desire to leave Birnam Wood is undercut by our realization that Mira has divined this desire weeks earlier. Mira’s perception of their relationship is undercut when, worried that Shelley has already left, she gets out her phone to check a “location tracker app that they had both installed . . . and never used.” But Shelley, we happen to know, uses the app to keep tabs on Mira all the time. They share an understanding of their friendship—that Mira is the top dog and Shelley is the sidekick, and that Shelley is “smothered” by this dynamic—that may not be true at all, or not true in the way they think.

Unlike Donna Tartt, who uses plot as straightforwardly as Dickens, or Sally Rooney, who has remade the marriage plot for a post-marriage era, Catton lets her plots and their attendant stakes emerge from a general situation. Like her characters, we begin without a sense of what matters, and are often pointed in the wrong direction. Initially, “Birnam Wood” seems to have no aspirations beyond an exploration of young, white, left-wing radicalism and its accompanying guilt—the kind of book that is “about” the anxiety of being a good person under capitalism and/or climate change. Mira fantasizes about brutal deaths in order to punish herself for feeling insufficiently bad about them. (“She compelled herself to imagine being crushed and suffocated, holding the thought in her mind’s eye for several seconds.”) Tony wants to argue about identity politics. When Mira allies herself with Lemoine, agreeing, over Tony’s protests, to let him finance Birnam Wood, we think we know how this will go: some hand-wringing, followed by some form of sexual congress, followed by a shrug over the problems of selling out.

We are wrong. “Birnam Wood” ’s biggest twist is not so much a particular event as the realization that this is a book in which everything that people choose to do matters, albeit not in ways they may have anticipated. Catton has a profound command of how perceptions lead to choice, and of how choice, for most of us, is an act of self-definition. Take Mira, whose determination not to be typecast lends her a stubbornness that’s easily mistaken for strength of character. Like some of her friends, Mira assumes that Lemoine’s interest in her is sexual: indeed, she spends time first imagining a scenario in which she’s propositioned and, ice-cold, turns him down, then an alternative, deflationary scenario in which she sleeps with him to prove that she’s not a prude. Her need to be unpredictable makes her easy to manipulate—it wouldn’t be unfair to say that she takes Lemoine’s money to show that she’s more than an idealist. But this choice is not, ultimately, about her. It invites violence, both symbolically—Birnam Wood now runs on “blood money,” as Tony puts it—and, as the book goes on, quite literally. The idea that her choices could affect something other than her internal narrative doesn’t occur to Mira, because it doesn’t often occur to anybody.

Meanwhile, “Birnam Wood” ’s true turns are all carefully set up, as long as you’re focussing on the right details. But none of the characters pay attention to the right things; they all think their snap impressions tell them what they need to know. Even Lemoine’s canny manipulation of others relies on the kind of lie that looks like the truth: a bunker is what people will expect him to be hiding, so that’s what he must be hiding. Discovering that they live in a world of consequence, with stakes bigger than self-image or self-respect, is as much of a shock to the characters as it is to us. Congratulations, Catton seems to say, on being just smart enough to play yourself.

Catton’s own choices are not without their critics. In a review of her second novel, the Booker Prize-winning “The Luminaries,” a critic for the Guardian wrote that the book was “a massive shaggy dog story; a great empty bag; an enormous, wicked, gleeful cheat.” But “The Luminaries” does tell a real story—a story of fated lovers—that it reveals only by inches. This romance, which appears to transcend the limits of space, is so heartfelt as to be, when put in plain view, almost embarrassing. For most of the book, it’s obscured, and we spend the first five or six hundred pages meeting the many characters whose various, complex, and sometimes tragic lives are, in the end, merely secondary. We discover what all of this is about at the same time they do.

Although “The Luminaries” stretches this form of emergent storytelling to the breaking point—it might not be a cheat, but several hundred pages is a long time to spend on misdirection—it’s clear that Catton is trying both to revive plot as a literary mode and to consider what a story line looks like in our real, unplotted life, in which things reveal themselves to have a shape only in retrospect. This project appears in a more subdued form in “The Rehearsal,” Catton’s début novel, which begins with a scandal: a student and a teacher have been discovered in a sexual affair. Everything in “The Rehearsal” takes place in a realm of high artifice, characterized by people who are so exact in their speech that you’re terrified to contemplate what they might not be saying. “A film of soured breast milk clutches at your daughter like a shroud,” a saxophone teacher informs the mother of a student. “Do you hear me, with your mouth like a thin scarlet thread and your deflated bosom and your stale mustard blouse?”

No saxophone teacher, or human being, for that matter, has ever spoken anything even approaching these words, but the arch, direct tone re-creates the unsettling world of adolescence, and the murky nature of adult expectation, more precisely than realism could. We expect the “story” of “The Rehearsal” to be about the fallout from the student-teacher affair. But this is really the backdrop for the novel’s true story, which is how the saxophone teacher tries—and fails—to use her students to reënact the story of her own frustrated love for another woman, with a different, happier ending. She fails because she cannot control the students’ choices any more than she could those of her onetime friend.

This willingness to let characters be mistaken—really, lastingly mistaken—is another quality that emerges from Catton’s privileging of human choice. When Tony uncovers proof of Lemoine’s rare-earth mining, he draws reasonable but slightly incorrect conclusions, assuming that Lemoine must be conspiring with Sir Darvish instead of deceiving him. The only people who would be in a position to correct him don’t—and so he carries on with this not false, but not true, version of events to the end. When Rosie Demarney, alone in her apartment, succumbs to an evening of Internet-stalking Tony, she stumbles across evidence that he could be in danger. In a Dickens novel, a character like Rosie might turn out to be pivotal; she’d connect the dots and save the day. Instead, she leaves the story for good. Would you, after all, go on a wild chase for someone you’d just been drunkenly Googling in your sweatpants? Someone you didn’t really know? Would it even matter if you tried?

One of the tragedies that plot brings to light is the degree to which our inner lives and intentions can simply come to nothing—unrealized despite our best efforts, misunderstood and fruitless, as the story we played our part in generating goes on without us. It is only by elevating human choice that we can see how often our choices don’t matter, after all. Or maybe it would be better to say that our choices matter only unpredictably. There’s no way of knowing what will really count until later, and by then it’s too late. Better choose.

In the course of “Birnam Wood,” Lemoine hacks phones, infiltrates e-mail accounts, operates drones with spy cameras, and employs a team of covert operatives. In his relentless surveillance, he is half critic, half author, and, in his own estimation, a kind of god. Like Catton, he tricks people into seeing what they expect to see.

But surveillance isn’t reading, much less writing; it’s data captured without interpretation. Instead of characters, we get types; instead of principles, revealed preferences. “A marketing algorithm doesn’t see you as a human being,” Tony says at one point, having lost his temper with another member of Birnam Wood:

It sees you purely as a matrix of categories: a person who’s female, and heterosexual . . . and white, and university-educated, and employed, who has these kinds of friends and shares these kinds of articles and posts these kinds of pictures and makes these kinds of searches . . . . Identity politics, intersectionality, whatever you call it—it’s the exact same thing.

It must be true that people often are what, on the surface, they seem to be; if it weren’t, algorithms wouldn’t have much use at all. There’s a certain pleasure in being a known type. At one point, Lemoine notes how “being a cliché can be very useful,” as it makes other people “think they’ve seen all there is to see.” Lady Darvish, musing on her marriage, thinks that her husband “took a certain pride in being so predictable . . . for the simple reason that he loved to see her demonstrate how well she understood him.”

Here, though, the implication is that we can read people without reducing them to a type. Owen Darvish loves to watch his wife “take that caricature and refine it, improving the likeness, adding depth and subtlety, shading it in.” Although not an optimistic book, “Birnam Wood” suggests that the greatest spook technology of all remains human love, with all its presumptive qualities, and that no external approximation will ever beat it at its game. There are things you just won’t know about other people, even if you intercept every text and every e-mail, unless you have loved them for a long time. There are gambles you are willing to take, acts of heroism and trust you are willing to commit to, because you know that you know them.

As for whether those acts matter, “Birnam Wood,” like all good books, doesn’t supply an answer. Reading it, I was drawn to the question of who represents Macbeth, the king who would be defeated only when “Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill / Shall come against him.” Macbeth is a character severed from choice. Prophecy, like a mystical surveillance system, keeps him blameless and safe: he is simply the man who is going to be king, and he does what he must do in order to preserve himself. In studying how much this or that person resembled him, I thought about ambition, deceit, paranoia, and unscrupulous ascension to power. I wondered who would be one of the witches, or, for that matter, Macduff. I wondered a lot of things—and yet it didn’t occur to me until the book’s final pages that the most significant attribute Macbeth possesses is something much more straightforward, at least where plot is concerned. Because Macbeth doesn’t understand what he’s told, because he lets prophecy make his choices for him, because he is at heart a cowardly man, when he’s faced with a certain human ingenuity, he loses. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

Why facts don’t change our minds .

The tricks rich people use to avoid taxes .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

How did polyamory get so popular ?

The ghostwriter who regrets working for Donald Trump .

Snoozers are, in fact, losers .

Fiction by Jamaica Kincaid: “Girl”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Gideon Lewis-Kraus

By Louis Menand

By Elizabeth Kolbert

A Biting Satire About the Idealistic Left

Eleanor Catton’s new novel, Birnam Wood , pokes at the pieties of those who want to change the world.

Ask me how much time and money I have devoted, in my adult life, to conscious efforts to be a good person, and I would struggle to quantify it. Of course, I would also struggle to tell you what “being good” means. My ideas seem to change constantly, which means the target shifts. Besides, the world I inhabit does not make goodness easy, for me or anyone else. I put clothes I no longer wear in giveaway bins run by a profoundly inefficient nonprofit ; I assiduously recycle despite reports that my plastic is likely “ headed to landfills, or worse ”; I sign up for shifts at a food bank, then cancel because I have to work. If I were giving away more money, or more of my time, my efforts would surely be wobblier or more questionable still.

Birnam Wood , the third novel by the New Zealand writer Eleanor Catton, picks up on the instability of trying to be good, a pursuit the book views quite bleakly. Loosely about the idealistic antics of a guerrilla gardening group, it has no hero but rather an ensemble of antiheroes whose foibles Catton uses to poke, quite hard, at the dreams and pieties of people who believe they can change the world. Such an impulse is a major shift from Catton’s Man Booker Prize–winning second novel, The Luminaries , an intricate, glowing love story set during New Zealand’s gold rush. Birnam Wood , in contrast, is dark in both its outlook and its omnipresent humor.

Catton is especially sharp in her portrayal of Mira Bunting, Birnam Wood’s charismatic founder. Day to day, the group plants legal gardens in donated yards and illegal ones on unmonitored land across New Zealand. Mira feels sure this project will someday generate “radical, widespread, and lasting social change” by showing people “how much fertile land was going begging, all around them, every day … and how arbitrary and absurdly prejudicial the entire concept of land ownership, when divorced from use or habitation, really was!” She is so confident, in fact, that when an American billionaire—who, to the reader, is plainly menacing—offers her a major donation and access to a large swath of land to cultivate, she barely blinks before making the executive decision that the group should accept.

Catton swiftly reveals Robert Lemoine, the billionaire in question, to be a James Bond–style bad guy, a 100-percent-evil evildoer who supports Birnam Wood only because he can use its garden to help conceal his scheme to illegally mine rare-earth minerals from a protected nature reserve next to land he has recently, secretly bought. Simply by linking Birnam Wood to him, Mira puts herself and the group in great danger. Catton draws Lemoine in great detail, but he is less a three-dimensional character than a wall for her to project her other characters against. His static, reliable badness allows—and occasionally causes—everyone else’s degree of goodness to flicker and change.

That concept of goodness gets put to the test first with the group’s debates over whether it’s right to take Lemoine’s money. Before long, though, the novel begins questioning the nature of do-gooding in a compromised and compromising world. It gradually transforms into a sincere interrogation of the relationship between morality and the ability to bring about positive change. Birnam Wood wants to know if a person has to be good to do good—and how to identify what goodness is in the first place.

If Birnam Wood is an exploration of idealism, its characters are the different lenses through which Catton wants us to consider it. Mira is a classic founder, charismatic and self-confident to the point of rashness. She attracts rapt audiences, which means that no one questions her Lemoine plan but Tony, a Bernie-bro type whose strident opposition has the effect of actually pushing the group toward accepting the billionaire’s money. Mira’s loyal sidekick, Shelley, is reliable and slightly gullible in the way that the unimaginative sometimes are. As the two lead a ragtag group of volunteers to camp on Lemoine’s land, their dynamic underscores the extent to which different sorts of idealists, acting in concert, can create chaos instead of change.

Mira cares only for dramatic transformation. Indeed, her minor impulses are not good at all. On the solo trip that leads to her first encounter with Lemoine, she pitches her tent at a campsite with “an honesty box for camp fees that Mira pretended not to see.” Pretended is key here: Alone, Mira has no motivation to do the little right thing; indeed, she feels herself to be above it. Meanwhile, Shelley, who would never walk by an honesty box, feels that she could do more overall good if she could be more like Mira. In this contrast, Catton captures a broader tension: between minor purists like Shelley, unable to compromise on the small stuff yet glad to go along with Mira on bigger decisions, and leaders like Mira, whose ambition leads her far past pragmatism into a dangerous dirtying of her hands.

Read: What we gain from a good-enough life

Tony is another sort of purist entirely. He cares about purity on a big scale, and he’s more than willing to fight for it. While the group builds hoop houses and plants seedlings, and Shelley, in the “stout belief that there was nothing more beneficial to group harmony than to ensure the food was plentiful and good,” spends too much of Lemoine’s donation on “cured meats, and hard cheeses, and decent coffee, and kombucha cultures,” Tony marches into the nature reserve near Birnam Wood’s new project, having declared himself an investigative journalist—he has a blog—and decided to expose the Bad Thing he feels sure Lemoine is up to.

Catton balances constantly on the razor’s edge between writing Tony as a comic pest and making him so irritating that he is nearly unreadable. Often, he is redeemed by the fact that he is correct. Tony worships “intellectual rigour;” his signature insult is “You’re not being rational here.” But as he tramps around the reserve, he begins to see that reason is not the only lens for viewing the world, even as his rational powers tell him that Lemoine (whose illegal mining, by this stage in the novel, is well under way) cannot possibly mean either Birnam Wood or the nation of New Zealand well. Tony’s willingness to take on a Goliath such as Lemoine makes him the novel’s only character with a prayer of actually changing things in a major sort of way—unlike Mira, whose attraction to power undoes many of her dreams.

Part of what seems to intrigue Catton is the question of whether it is better to aspire to what could be called Big Good—for Tony, exposing Lemoine’s mining scheme; for Mira and her volunteers, shifting public opinion on land ownership—or Small Good. Before Lemoine came on the scene, Birnam Wood did quite a lot of the latter by growing vegetables on fallow land and donating a large chunk of their yield to the hungry. Mira, plainly, was never content with this work: She wouldn’t even accept Shelley’s repeated suggestion that they launch a community-supported agriculture program, which would have given the group more financial and logistical stability and allowed them to expand their good works. Stability is undramatic, and to a person who sees herself as a mover and shaker, drama is inherently desirable. For much of Birnam Wood , it is tempting to wish Mira had stuck to her small gardens—but Tony is as big a drama lover as Mira, and Catton pushes the reader to hope against hope that he will pull his exposé off.

Tony is not a fun character to root for. Birnam Wood would be, in some sense, a more enjoyable book if Catton made it possible to imagine that Mira and Shelley could somehow band together to prevent the ecological destruction Lemoine’s mining plan will wreak, and then grow the greatest garden of all time. But from the moment the group sets up camp near the reserve, it is clear that Mira is too taken with Lemoine—or, worse still, with the oblique and exaggerated reflection of herself that she sees in him—to resist him in any way. Her infatuation and Shelley’s credulity undermine the usefulness of Birnam Wood’s work and send the novel skidding toward tragedy and disaster.

Ultimately, Birnam Wood suggests that usefulness is the only reliable metric for either Big or Small Good, imperfect though it may be. It would be useful for Tony to expose Lemoine; it is useful for Birnam Wood to feed the hungry. Quite often, Catton seems to be searching among her flawed protagonists for the bits of usefulness they produce, and to take those bits of value seriously without ignoring the ways that each character’s flaws prevent them from doing better. But she also suggests that in the face of badness—or, frankly, in the quotidian, compromising situations that do-gooders less flamboyant than Mira still find themselves in every day—caution grows more necessary, not less. As Mira never quite learns, you get nowhere by going too fast.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- Australia edition

- International edition

- Europe edition

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton review – hippies v billionaires

The Booker winner captures our collective despair in a thrillerish novel about climate crisis

I n a literary marketplace that sometimes seems oversupplied with novels about brittle intellectuals feeling alienated from their emotions, or twentysomethings grinding axes about their exes, there is the wonder of Eleanor Catton: a novelist of lavish technical gifts who addresses herself to the world, broadly and richly conceived.

Catton’s first novel, 2008’s The Rehearsal , was a small miracle. Leaping acrobatically between fictional and metafictional modes, it tells the story of a secondary-school scandal (male teacher, female student) restaged by trainees at a local drama school. There is something almost Brechtian about the way it shocks you out of familiar fictional comfort zones, and something almost Wildean in the way it lobs its arch perceptions, like glittering little hand grenades, at all sorts of social and artistic pieties.

Catton’s second novel, 2013’s The Luminaries , was a large miracle (it won her the Booker). Running to 821 pages, and set among the gold fields of 1860s New Zealand, The Luminaries is structured around two highly artificial conceits. At one level it spins an intricate pastiche-Victorian mystery revolving around gold, opium and changed identities. At another, its structure follows elaborate astrological rules – a prefatory “Character Chart” notes which characters are “Stellar” and which “Planetary”, and so forth. It is brilliant; a virtuoso performance. But, like most virtuoso performances, it does leave you with the nagging suspicion that virtuosity itself is the point.

Take the novel’s characters, each one carefully painted but nonetheless in thrall to Catton’s great determining structures. The luminaries have personalities but not really that much in the way of life. Catton’s marvellously imagined 19th-century world revolves, and the astrologically directed people go about their tricksy business, but it is difficult not to feel that the machinery underneath it all is the real star of the show. As with certain CGI blockbusters, you marvel at the spectacle and wonder about the vision.

Birnam Wood, Catton’s third novel, raises the question of vision once again. Technically speaking, it’s another virtuoso performance: elaborately plotted, richly conceived, enormously readable. It might seem like cavilling to suggest that what it lacks is an original or surprising sense of our riven world. But without this kind of vision – without insight that reaches beyond good and evil – you risk creating only a superbly polished mirror, one that shows us the world as we already know it.

Literary novels, as opposed to the sort of thriller that pitches goodies against baddies without much moral shading, ideally do more than this. And, in fairness, Catton’s publisher is calling Birnam Wood “a gripping psychological thriller”. Political thriller might be more accurate, since it is really about the schemas and deadlocks of our contemporary politics. Birnam Wood – the forest that moves to Dunsinane Hill to herald the fall of Macbeth – is the name chosen, semi-ironically, by an “activist collective” based in Christchurch, New Zealand. Birnam Wood’s founder, Mira Bunting, hopes for “nothing less than radical, widespread, and lasting social change”; her group’s contribution to this change takes the form of guerrilla gardening projects, reclaiming waste public and private land to grow food crops.

Is Mira Macbeth? She might be; she enters into a deal with the novel’s villain, billionaire Robert Lemoine, a Peter Thiel -resembling “doomsteader” who seems to be buying up a tract of rural New Zealand so he can build a luxury bunker and ride out the apocalypse. Then again, Lemoine himself might be Macbeth. His doomsteading project, we quickly learn, is a front. Secretly, he is extracting rare-earth minerals from Korowai national park. He toys with Mira and invests in Birnam Wood largely for the hell of it – because he is, as the novel exhaustively, and at points hilariously, makes clear, a total psychopath. Birnam Wood moves its operations to Lemoine’s doomsteader tract. Will this herald his fall?

It’s hippies versus billionaires: a scenario full of comic potential, of course. To spike the mixture, Catton throws in a righteous young aspiring journalist, Tony Gallo, and a recently knighted New Zealand business maven, Sir Owen Darvish, and his loving wife, Lady Darvish (as with Sir Owen’s fictional predecessor, Sir William Lucas in Pride and Prejudice, “The distinction had perhaps been felt too strongly”).

The first half of the novel, setting all this up, is hugely entertaining. Catton, you think, can do anything fiction requires: she can write funny social satire; she can stage a convincingly self-defeating fight among leftist radicals; she can notice “the hash of oily streaks and fingerprints” on a locked phone screen. You keep waiting for her to do something astonishing with her setup – to give us a novel that doesn’t just crash dishevelled goodies (Birnam Wood) into a suave baddie (Robert Lemoine).

after newsletter promotion

But instead of ushering us into a world of surprising insights, Birnam Wood relies – no spoilers – on a finely spun web of misunderstandings and coincidences to drive its increasingly thrillerish second half. The fictional craftsmanship is above reproach. But it’s hard not to feel a bit disappointed that such a beautifully built novel just tells us the same old, same old: billionaires bad! Leftwing radicals good, if sometimes misguided and hapless!

Then again, Birnam Wood does efficiently dramatise a specifically contemporary pessimism: its theme is our collective despair about the locked social geology that prevents meaningful action on climate change. It’s an important subject. And maybe we should expect our schematically unequal world to produce schematic fiction – stories about goodies and baddies, poor people and billionaires, peasants and kings. Catton is not wrong; she is certainly showing us the world we know. But our culture is already rife with calls for moral simplicity. Isn’t it the duty of the literary novel to go deeper?

- Eleanor Catton

- Book of the day

Most viewed

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton: youngest-ever Booker winner returns with a satirical thriller

The Luminaries novelist is back after ten years, casting her mischievous comic eye on a group of millennial eco-warriors

In 2013, aged 28, Eleanor Catton sprang to instant literary fame with The Luminaries . Set in the 19th-century goldfields of her native New Zealand, it provided a pitch-perfect impersonation of an 800-page Victorian novel, complete with such elements as long-lost siblings, a scarred villain, a consumptive wife, a mad wife and an opium den.

Yet, for my money, this was precisely the problem. While there was no doubting the skill involved, one awkward question wouldn’t go away: what was the point? Wasn’t this just an effortful, somewhat airless simulacrum of a great novel rather than the real thing? Weirdly, though, the world didn’t seem to agree with me. The Luminaries not only won the Booker Prize, but it also broke two Booker records – the longest-ever winning novel and the youngest-ever winning author. So, how do you follow that?

Ten years later, we have our unexpected answer: with a wildly exciting contemporary thriller that also casts a winningly satirical eye on millennials and their paradoxical taste for self-satisfied angst.

The Birnam Wood of the title is a group of New Zealand eco-activists who plant crops on neglected patches of land so as to show how much land is wasted. Their founder is Mira Bunting, who, in a less cunning (and more boring) novel might be a straightforward goodie. After all, she says – and probably even believes – all the correct Left-wing things. She’s willing to take on powerful people, including Sir Owen Darvish, whose swathes of rural farmland are lying unused while he’s at his Wellington pied-à-terre raking in the money from his pest-control business. Surely, Mira suggests to the group, they should invade his farm with as many seeds as they can muster.

But already the book is casting a beady comic eye on Mira and her fellow “self-mythologising rebels”. As Catton sees it, the trouble is not that they’re wrong to have the concerns they do, just that the supposed altruism is not always distinguishable from egotism. They also take a distinct pleasure in the sense of piety and martyrdom that comes with “feeling oneself and one’s entire generation to have been wronged by those in power”.

On a more sympathetic (but still mischievously comic) note, Catton shows, too, how ferociously these people police each other – and themselves. Poor Mira, for example, is “a remorseless critic of her own emotions”, which sadly fail to match the impossibly high standards she imagines she should be living by. (One of her dark secrets is that, despite her feminism, “she preferred the company of men”.)