Nothing in your cart

Game categories

Explore the pe games database., elf express, snowman blitz, get the latest games delivered to your inbox, subscribe to the #physed newsletter, professional development.

Shopping Cart

No products in the basket.

Teaching physical education – PEdagogical Model: Cooperative learning

Applying effective teaching approaches to the ‘how’ of Physical Education (PE)

In this series, we present six one-page summaries of key Pedagogical Models that should form part of the diet of rich and varied PE delivery.

Each of these models provides a structured framework to guide the teaching and learning process, enhancing the overall effectiveness of physical education programmes.

The benefits of applying PE pedagogical models

Organised and purposeful lesson plans.

Pedagogical models help PE educators create learning material and carefully planned lessons designed to address key learning objectives. They also promote a systematic progression of skills and knowledge to meet intended learning outcomes, facilitating a logical and effective learning journey for students.

Differentiated instruction

Moreover, these models contribute to differentiated instruction, allowing teachers to tailor their approach to meet the diverse needs and abilities of students. By incorporating various and effective teaching strategies and styles, pedagogical models enhance engagement and understanding among students with different learning preferences. Variety is the spice of life and all that!

Incorporation of critical life skills

Additionally, the use of pedagogical models in PE delivery supports the development of critical life skills such as teamwork, communication, creativity and problem-solving. Structured lesson plans enable educators to integrate these skills seamlessly into physical activities, promoting holistic student growth.

Holistic development

It is widely accepted that PE has the potential to develop physical, cognitive, social and affective domains of learning. By using a rich variety of ‘models’ in your practice it can pave the way to move ‘beyond the physical’ to recognise, develop and celebrate wider skill development that is essential to success in PE, in sport, and in life.

Assessment and evaluation

Furthermore, employing pedagogical models assists in the assessment and evaluation of student progress. The models prompt the incorporation of measurable criteria for evaluating individual and collective achievements in PE, aiding in the identification of areas for improvement and adjustment of instructional strategies.

Today’s PEdagogical model: cooperative learning

Cooperative student learning involves students collaboratively working in small groups to achieve shared objectives, fostering enhanced learning experiences, crucial group skills and social skill development. Instead of encouraging competitive or individualistic learning, the model nurtures informal cooperative learning so that group members develop positive interdependence that extends beyond the PE class.

Originating from the emphasis on social learning by American philosopher John Dewey in 1916, the concept gained prominence in the 1960s and 1970s.

The model encourages students to take responsibility for reciprocal learning and peer coaching, which can boost engagement and learning potential. In this approach, the teacher assumes the role of a facilitator, providing guidance and support while allowing flexibility in lesson delivery. Students are typically divided into formal cooperative learning groups of 4 or 5, are assigned specific tasks or activities, which promotes teamwork, communication, and interdependence.

Cooperative learning spans various activities, encompassing team sports, fitness challenges, choreography in gymnastics or dance, and problem-solving games. Integrating physical, cognitive, social, and emotional learning within the same unit makes it a great solution for PE.

- Social and emotional learning gains are maximised

- Build class culture, positive ethos and student enjoyment

- Leadership, teamworking and communication skills developed in an inclusive environment

Disadvantages

- Heterogeneous cooperative learning groups can be challenging to manage

- Students’ own learning often takes longer but it is ‘stickier’

- Social loafing can occur if individuals don’t have clear accountability within their group

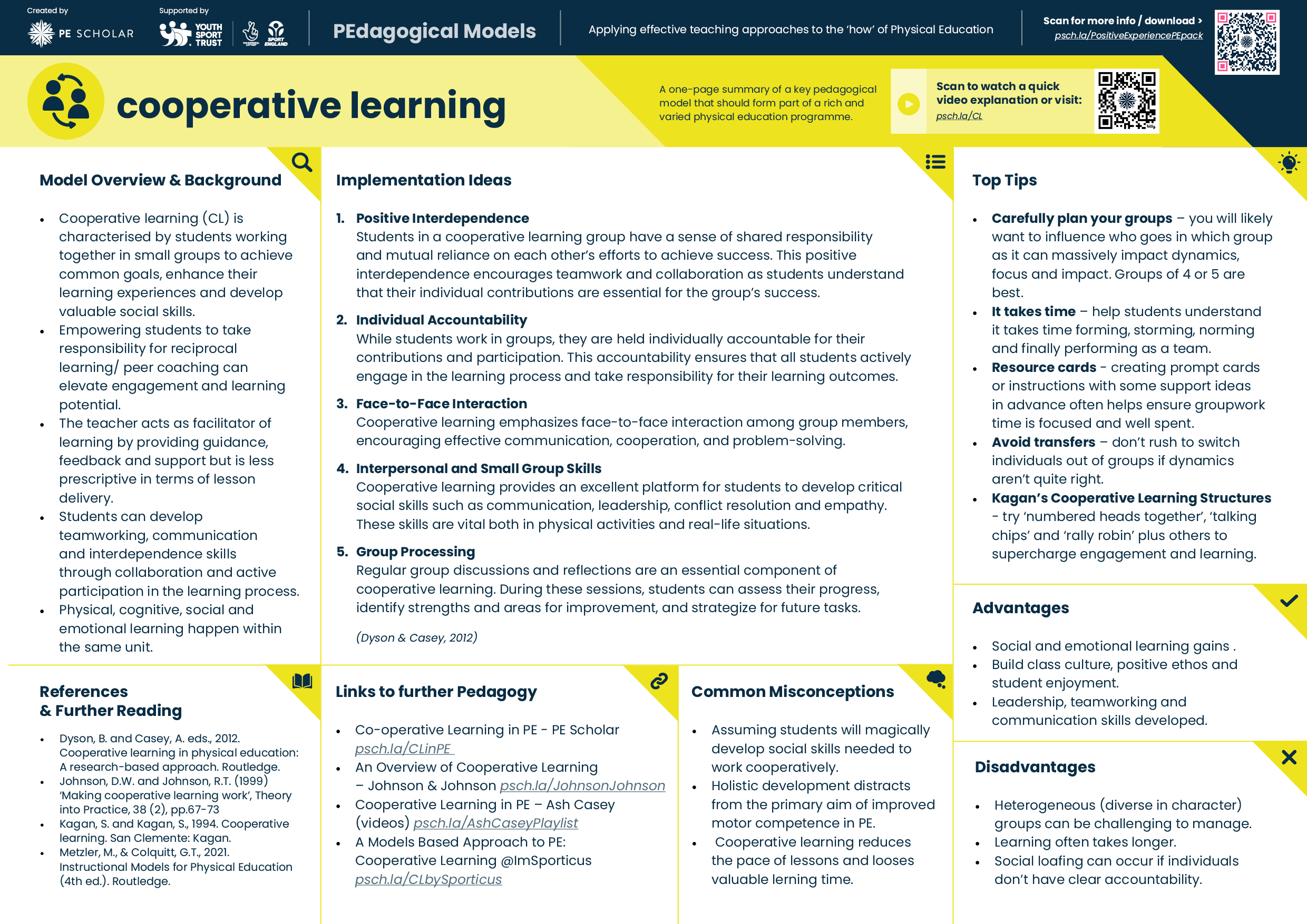

One-page summary – cooperative learning

Download the attached one-page summary for further information on cooperative learning.

Curriculum development: Why not use it to guide a PE department meeting followed by a period of testing and instructional coaching to help develop your repertoire of approaches to teaching.

It includes a short video available via the QR code to bring it to life along with:

Implementation ideas

Common misconceptions, links to further pedagogy.

Coming soon! Next in the series

Look out for the next in our PEdagogical models series:

Games-based approaches

Sport education, health-based pe (hbpe), teaching personal and social responsibility (tpsr), previous pedagogical models in the series.

You can also access the previous post and one page summary on

Direct instruction by clicking here

Further information

This insight provides an extended read on the benefits of cooperative learning along with some examples

Adopting a models based practice for physical educators

Book review

Physical education pedagogies for health

https://www.pescholar.com/courses/

Sorry, you must be a member to view downloads. Join Now. Already a member? Please sign in to view downloads.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Related Resources

Want to initiate more conversations between all staff, their students and wellbeing? This poster has…

Mosston & Ashworth Imagine a framework that presents not one way to teach, but eleven.…

It has always frustrated me how athletics looks in so many schools - a complex…

There was a problem reporting this post.

Effects of Cooperative-Learning Interventions on Physical Education Students’ Intrinsic Motivation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Carlos fernández-espínola.

1 Faculty of Education, Psychology and Sport Sciences, University of Huelva, 21071 Huelva, Spain; [email protected] (C.F.-E.); [email protected] (B.J.A.); [email protected] (E.C.V.); se.uhu@setneufj (F.J.G.F.-G.)

Manuel Tomás Abad Robles

Daniel collado-mateo.

2 Centre for Sport Studies, Rey Juan Carlos University, 28943 Madrid, Spain; moc.liamg@modallocinad

Bartolomé J. Almagro

Estefanía castillo viera, francisco javier giménez fuentes-guerra.

The aim was to review the effects of cooperative learning interventions on intrinsic motivation in physical education students, as well as to conduct a meta-analysis to determinate the overall effect size of these interventions. The PRISMA guidelines were followed to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis. The PEDro Scale was used to assess the risk of bias and the GRADE approach was used to evaluate the quality of the evidence. A total of five studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and they were included in the meta-analysis. Effect size for intrinsic motivation of each study was calculated using the means and standard deviations of the Perceived Locus of Causality Scale (PLOC) before and after the intervention. The overall effect size for intrinsic motivation was 0.38 (95% CI from 0.17 to 0.60) while the heterogeneity was large. Although four of the five studies reported significant within-group improvements in intrinsic motivation, only three studies showed significant between-group differences in favor of the experimental group. The findings showed that program duration and participant age may be relevant factors that must be considered by educators and researchers to conduct future effective interventions. Cooperative learning interventions could be a useful teaching strategy to improve physical education students’ intrinsic motivation. However, given the large heterogeneity and the low quality of the evidence, these findings must be taken with caution.

1. Introduction

Over the last two decades, achievement goal theory [ 1 ] together with the self-determination theory [ 2 , 3 ] and Vallerand’s hierarchical model of motivation [ 4 ] have been effectively complemented to examine physical education students’ motivational process. These last two theories describe a sequence of motivational variables where social factors (i.e., the teacher’s interpersonal style) can influence satisfaction or can thwart basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness). Autonomy can be defined as a person’s need to experience actions of their own choosing. Competence refers to the need to control results and achieve efficiency; relatedness can be defined as the need to be connected to others and the feeling of being accepted [ 3 ]. In this regard, the satisfaction of these needs has been linked to some types of self-determination motivation, such as intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is defined as “spontaneous activity that is sustained by the satisfactions inherent in the activity itself” [ 3 ] (p. 99). Therefore, intrinsic motivation involves people participating freely in activities that they find interesting, that provide novelty, fun and an appropriate challenge [ 2 ]. In consequence, it can help to achieve benefits in the cognitive, affective and psychomotor aspects of physical education students [ 5 , 6 ].

Resembling the teacher’s interpersonal style, the motivational climate generated by a physical education teacher has been studied in the scientific literature as one of the social factors in the motivational sequence described above (social factors → basic psychological needs → types of motivation → consequences). The motivational climate is a construct from the achievement goal theory [ 1 ]. According to this theory, Ames [ 7 ] postulated that social agents (teacher, peers and parents) build two possible motivational climates: a task-oriented climate (where personal growth, effort and skill progression are highlighted); and an ego-oriented climate (where comparison between peers, member rivalry and results are emphasized). The scientific literature has shown that a task-oriented climate is linked to satisfaction of the three needs [ 8 , 9 ] and consequently it is also related to the most self-determined types of motivation [ 10 ].

In relation to achievement goal theory, cooperative learning has been suggested as a teaching strategy that can improve the motivation of young people [ 11 ]. A possible relation among a task-oriented climate and cooperative structure was hypothesized because they both highlight working and effort with others, instead of against others [ 12 ]. In fact, one of the most important instruments used in the scientific literature to measure these two motivational climates in sport and physical education contexts, the Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire-2 by Newton, Duda and Yin [ 13 ], considers that cooperative learning along with effort and role constitute the three subscales that make up the task-oriented climate dimension. This questionnaire has been used in previous studies conducted in different countries and focused on the evaluation of motivation in physical education students [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Cooperative learning is considered a pedagogical model, which can help to achieve learning outcomes of four types: physical, affective, social and cognitive [ 17 ]. For many years, cooperative learning has been used in the context of physical education [ 18 , 19 ]. In these studies, cooperative learning interventions were conducted in different educational settings, reporting positive effects on motor skills, social skills, cognitive understanding and on creating an affective domain for physical education students. In this sense, this pedagogical model could be a useful teaching strategy to improve intrinsic motivation since it could be associated with the satisfaction of basic psychological needs from self-determination theory. This model can help to satisfy the need of relatedness since it can develop good social relations between peers [ 20 ] and can satisfy the need of competence by increasing physical skills [ 21 ]. Precisely, this fact has been analyzed in other school subjects. In the study by Hänze and Berger [ 22 ], cooperative learning improved the expertise of basic needs in physics classes, which determined more intrinsic motivation in students. Accordingly, it is possible to hypothesize that a similar process may happen in the subject of physical education. In fact, a recent systematic review of cooperative learning in physical education [ 23 ] has showed that of the four types of outcomes, social learning has been the most frequently assessed in the last five years, focusing on the relationships between teachers and students and motivation.

Therefore, the main aim of this article was to conduct a systematic review of the scientific literature on the effects of cooperative learning interventions on physical education students’ intrinsic motivation. For this purpose, the effect sizes of cooperative learning interventions on intrinsic motivation were determined through a meta-analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA) guidelines have been followed to carry out the current systematic review [ 24 ].

2.1. Literature Search

The Web of Science (WOS), Scopus and SportDiscus electronic databases were utilized to locate the studies selected in the present systematic review with meta-analysis. The search terms were divided into four groups of keywords as follows: (1) “cooperative learning”, “cooperative games”, “models-based learning”; (2) “intervention”, “experimental”, “quasi-experimental”, “implementation”, “randomized controlled trial”; (3) “motivation”; and (4) “physical education”. The Boolean operator “or” was incorporated between the words included in the first and second groups and the operator “and” was incorporated between each group. The manuscript search was conducted in April 2020.

2.2. Study Selection

The manuscripts were selected if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (a) intervention was based on cooperative learning, (b) physical education students’ intrinsic motivation was measured, (c) the article was written in English or Spanish, (d) the manuscript was an article published or accepted in a peer review journal. No inclusion criteria related to the years of publication of the articles were considered. The study selection process was conducted by two independent authors (C.F.-E., and M.T.A.R.).

2.3. Assessment of Risk of Bias

To assess risk of bias, the PEDro scale was used [ 25 ]. This scale was developed to evaluate the quality of intervention studies, especially randomized controlled trials. The GRADE guidelines, which involves a four-point scale (“very low”, “low”, “moderate” and “high”) was used to assess the quality of evidence [ 26 ]. Table 1 shows the risk of bias results of included articles.

Risk of bias according to the PEDro Scale.

| Study | Response to Each Item Level of Evidence | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total Score | |

| Cecchini et al., 2019 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Fernández-Argüelles and González-González de Mesa, 2018 | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 4 |

| Navarro-Patón et al., 2017 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 5 |

| Fernández-Río et al., 2017 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Fernández-Río et al., 2014 | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

Y: criterion fulfilled; N: criterion not fulfilled; 1: eligibility criteria were defined; 2: the participants were randomly distributed to groups; 3: the assigned was concealed; 4: the groups were similar before the intervention (at baseline); 5: all participants were blinded; 6: therapists (teachers) who conducted the intervention were blinded; 7: there was blinding of all evaluators; 8: the measures of at least one of the fundamental outcomes were attained from more than 85% of the participants initially; 9:” intention to treat” analysis was conducted on all participants who received the control condition or treatment as assigned; 10: the findings of statistical comparisons between groups were reported for at least one fundamental outcome; 11: the study gives variability and punctual measures for at least one fundamental outcome; total score: each satisfied item (except the first) adds 1 point to the total score.

2.4. Data Collection

Firstly, two authors extracted data from the included articles. Subsequently, another author checked the extracted information. In accordance with the recommendations from PRISMA guidelines, the information extracted was as follows: participants, intervention, comparisons, outcomes or results and study design (PICOS) [ 27 ]. Table 2 shows the main characteristics of the different protocols of intervention and the main participants’ characteristics: sex, age, level of education and sample size. Regarding interventions, Table 3 summarizes the following details: duration of the study, number of sessions and type of cooperative intervention program.

Characteristics of the participants and the protocol.

| Study | Characteristics of the Sample | Protocol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size of Groups and Sex | Age (SD) and Education Level | Cooperative Learning Group Treatment | Control Group Treatment | |

| Cecchini et al., 2019 | CLG: 182 (86 females) | 14.20 (2.34) High school | Cooperative learning strategies | Traditional teaching |

| CG: 190 (89 females) | ||||

| Fernández-Argüelles and González-González de Mesa, 2018 | CLG: 16 (6 females) | 8.4 (NR) Primary school | Cooperative games with cooperative learning structures | Traditional teaching based on the competition |

| CG: 15 (9 females) | ||||

| Navarro-Patón et al., 2017 | CLG: 54 (24 females) | 10.29 (0.62) Primary school | Cooperative games | Traditional teaching |

| CG: 50 (21 females) | ||||

| Fernández-Río et al., 2017 | CLG: 137 (71 females) | 13.66 (1.51) High school | Cooperative learning strategies with cooperative learning structures | Traditional teaching |

| CG: 112 (56 females) | ||||

| Fernández-Río et al., 2014 | CLG: 130 (87 females) | 20.39 (NR) University | Cooperative learning strategies with cooperative learning structures | Traditional teaching |

| CG: 134 (89 females) | ||||

Note: CLG = Cooperative Learning Group; CG = Control Group; SD = Standard Deviation; NR = Not Reported.

Characteristics of the interventions (duration and activities).

| Study | Duration of Study | Number of Sessions | Type of Cooperative Intervention Program |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cecchini et al., 2019 | 6 months | NR | Four cooperative learning approaches (conceptual, curricular, structural and complex instruction) were used in the sessions. The program included cooperative learning strategies in sessions of physical expression based on football, volleyball and basketball. |

| Fernández-Argüelles and González-González de Mesa, 2018 | 6 weeks | 12 sessions | Cooperative games and exercises without competition. Learning structures were based on models-based learning as collective scores were used: the class or different groups should conduct a task whereby several points can be achieved during a determined time. Each small group member obtains an individual score, which is added to a total group score. |

| 1 h per session | |||

| Navarro-Patón et al., 2017 | 3 weeks | 6 sessions | Within all the cooperative learning units, each session was structured in the following form: an information phase, an activation phase, a goal achievement phase, a cool down phase and a final reflection. |

| 1 h per session | |||

| Fernández-Río et al., 2017 | 16 weeks | 30 sessions | Within all the Cooperative Learning units, small, heterogeneous working groups were created to capitalize on learning. All units included the five key elements: face-to-face promotive interaction, positive interdependence, individual accountability, interpersonal and small-group skills and group processing. Additionally, five cooperative learning structures were used: (1) Think-Share-Perform: students think, share ideas and negotiate to solve a challenge; (2) Co-op Play: Students should cooperate to solve a challenge; (3) Collective Score: as was explained previously; (4) Learning Teams or learning groups: in groups of four, students divided into different roles (teacher, performer, observer equipment manager) to solve a task or learn a skill; (5) Pairs-Check-Perform: in pairs, students learned a skill divided into two roles: apprentice and teacher. |

| 1 h per session | |||

| Fernández-Río et al., 2014 | 12 weeks | 24 sessions | Eight cooperative learning strategies were used: (1) classroom’s physical layout was reorganized; (2) heterogeneous and small working groups were created, (3) a minimum time (15 min) was given to each session for working in the small groups; (4) a positive classroom climate to encourage students to participate without fear was created; (5) students could use educational material to study the subject contents; (6) a wide variety of teaching-learning activities of a theoretical and practical nature were utilized; (7) different cooperative learning techniques were used, such as Learning Together (promotion of group activities (e.g., debates) and positives attitudes (e.g., respect, effort or help) or Coop-Coop (the unit is divided in subunits, which are distributed into different groups. Afterwards, each small group member investigates a part of the subunit assigned to finally explain it to her/his classmates); and (8) lastly, assessment tools and different procedures of assessment were used. |

| 1 h per session |

Note: NR = Not Reported.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For this meta-analysis, a random-effects model was used to measure the effect of cooperative learning interventions on intrinsic motivation in physical education students. The results of each study on this variable can be seen in Table 3 . The treatment effect was calculated as the difference between the change in the experimental group and the change in the control group. In each study, effect size was calculated using the means and standard deviations before and after treatment [ 28 ]. The magnitude of the Cohen′s d was identified as follows: (a) “large”, for values higher than 0.8, (b) “moderate”, when it was between 0.5 and 0.8, (c) “small”, for values between 0.2 and 0.5, and (d) “no effect” for values below 0.2. Heterogeneity was assessed by calculating the following statistics: (a) Tau 2 , for the calculation of variance between studies, (b) Chi 2 and (c) I 2 , which is a transformation of the H statistic used to determine the percentage of the variation that is caused by the heterogeneity. The most common classification of I 2 considers values higher than 50% as large heterogeneity, values between 25% and 50% as average and lower than 25% as small [ 29 ]. The tool Review Manager 5.3 was used to conduct all analyses [ 30 ].

3.1. Study Selection

The complete process (PRISMA flow diagram) of this review is shown in Figure 1 . A total of 27 records were identified in the electronic databases—WOS (13), Scopus (7) and SportDiscus (7)—12 of which were removed because they were duplicated. Of the remaining 15 records, three were eliminated because they were not an intervention, three because the intervention programs were not based on cooperative learning, three because they did not measure the intrinsic motivation and one because it did not use a control group. Finally, five studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis after an exhaustive selection.

Flow diagram for the systematic review process according with PRISMA statements.

3.2. Risk of Bias

Table 1 shows the risk of bias of the five selected articles according to the PEDro scale. Scores varied from four [ 31 ] to seven [ 32 , 33 ]. Three studies showed a lower risk of bias, as they indicated a score of ≥6 [ 32 , 33 , 34 ]. By contrast, two studies showed a higher risk of bias, as they indicated a score of <6 [ 31 , 35 ]. Regarding the quality of evidence, the GRADE guidelines have been followed. In this sense, the rating start was “low” because the outcomes do not come from randomized controlled trials. Additionally, the quality of evidence was downgraded for reasons of inconsistency due to the degree of heterogeneity. Thus, the quality of evidence according to the GRADE guidelines was “very low”, which was defined as “We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect” [ 26 ] (p. 404).

3.3. Study Characteristics

Table 2 and Table 3 show a summary of the study characteristics. The total sample was 1020. Of these, 518 were distributed in the cooperative learning group (CLG) and 502 belonged to the control group (CG). Two studies were conducted in Primary School, two in High School and another at University level.

3.4. Interventions

Table 2 shows a summary of the cooperative learning interventions in each article: three studies used different cooperative learning structures or techniques such as Coop-Coop, Learning Together, Think-Share-Perform, Team Learning, Collective Score, etc. Only one study did not report information in this sense [ 35 ]. This table also summarizes the interventions of the control group of each article: all studies used traditional teaching methods.

Table 3 summarizes the duration of the programs and the number of sessions in each study. Intervention durations varied between three weeks and six months. The number of sessions ranged between 6 and 30. The study conducted by Cecchini et al. [ 33 ] did not report the number of sessions.

3.5. Outcome Measures

The effects of cooperative learning interventions on physical education students’ intrinsic motivation are shown in Figure 2 . To evaluate motivation levels, all five articles used the Spanish version of Perceived Locus of Causality Scale (PLOC), which is a version of a scale originally written in English by Goudas, Biddle and Fox [ 36 ]. This Scale was translated and validated for the Spanish context by Moreno-Murcia, González-Cutre and Chillón [ 37 ] and it measures five motivation levels (four items for level): Intrinsic motivation (e.g., “because Physical Education is fun”), Identified Regulation (e.g., “because I can learn new skills that I could use in other areas of my life”), Introjected Regulation (e.g., “I would feel bad about myself if I didn’t”), External Regulation (e.g., “because that is what I am supposed to do”), and Amotivation (e.g., “I really feel I’m wasting my time in Physical Education”). The previous sentence of this scale is “I take part in this Physical Education class”. For the answers, a Likert Scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) is used.

Meta-analysis: effect sizes for intrinsic motivation of cooperative learning interventions.

Having used PLOC to measure the physical education students’ intrinsic motivation, four of the five studies reported a significant increase in this variable relative to the baseline caused by cooperative learning intervention. Conversely, the study by Fernández-Argüelles and González-González de Mesa [ 31 ] reported a reduction in intrinsic motivation after the cooperative learning intervention. Nevertheless, the p -value was not reported. Regarding control groups, three studies reported non-significant changes and another study did not report them [ 31 ].

Interestingly, although three studies reported statistically significant improvement in the experimental group relative to baseline, as can be seen in Figure 2 , the studies by Cecchini et al. [ 33 ], by Fernández-Río, Cecchini, and Méndez-Giménez [ 34 ] and by Fernández-Río et al. [ 32 ] showed significant between-group differences in favor of the CLG.

Overall effect size for intrinsic motivation was 0.38 with a 95% CI from 0.17 to 0.60. In accordance with the proposed classification, this effect size was small. The heterogeneity level was high: Tau 2 = 0.05; Chi 2 = 19.72, df = 4 ( p = 0.0006); I 2 = 80%; test for overall effect: Z = 3.55 ( p = 0.0004).

4. Discussion

This systematic review with meta-analysis aimed to analyze the effects of cooperative learning interventions on physical education students’ intrinsic motivation. The main finding according to meta-analysis results was that cooperative learning could improve the intrinsic motivation in physical education students. Figure 2 shows that the effect size in three of five studies was in favor of the experimental group. These findings are in accordance with self-determination theory [ 2 , 3 ] and Vallerand’s hierarchical model of motivation [ 4 ], which described how social factors, where cooperative learning is included, can influence the different forms of motivation, and that this effect is exerted by means of the satisfaction of the basic psychological needs (competence, autonomy and relatedness). This improvement can be considered as small according to the overall effect size (d = 0.38 with a 95% CI from 0.17 to 0.60; p = 0.0004). Due to the low quality of the evidence, the interpretation of this meta-analysis must be done with caution. However, findings from the current meta-analysis could be useful for teachers and educators to improve intrinsic motivation in physical education students.

From the five interventions based on cooperative learning included in this meta-analysis, four studies reported a significant improvement in intrinsic motivation. The duration of these effective interventions varied between three weeks and six months [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. Conversely, in the study by Fernández-Argüelles and González-González [ 31 ] a decrease in intrinsic motivation was observed. Given that the intervention’s duration of that study was six weeks, the program duration does not seem to be the most critical factor. However, Figure 2 shows that the three longest studies [ 32 , 33 , 34 ] reported a higher effect size to the other two studies [ 31 , 35 ]. Therefore, according to this result, cooperative learning interventions should be carried out at least for 12 weeks to achieve a significant and relevant improvement in intrinsic motivation.

An important factor could be the age of the students. The study which reported a reduction in intrinsic motivation had a sample composed of primary school students with a mean age of 8.4 [ 31 ]. As shown in Figure 2 , this article reported a difference in favor of the control group. The remaining four studies (which reported significant improvement in intrinsic motivation) had a sample composed of primary school students with a mean age of 10.29 [ 35 ], high school students with a mean age of 13.66 [ 32 ] and 14.60 [ 33 ] and university students with a mean age of 20.39 [ 34 ]. These results are in line with the findings showed in the study by Hortigüela-Alcalá et al. [ 38 ]; they contrasted the effects of a cooperative learning intervention (without a control group) on factors such as motivation in students in two different educational stages: Primary Education (with a mean age of 11.37) and Secondary Education (with a mean age of 15.42). Motivation increased significantly in both groups. In this meta-analysis, the best results were achieved in the studies by Cecchini et al. [ 33 ] and by Fernández-Río et al. [ 32 , 34 ] Therefore, although the highest effect size was observed in the study by Cecchini et al. [ 33 ], in general, the results show that the effect size was higher in accordance with an increase of the age of participants. Consequently, the lowest effect size was observed in the study by Fernández-Argüelles and González-González de Mesa [ 31 ]. Furthermore, Fernández-Argüelles and González-González de Mesa [ 31 ] reported that an important limitation of their study was the young age of students, which may impair the execution of the program given the complexity of the strategies carried out in the sessions. Cooperative learning requires a high level of autonomy; thus, it would be advisable and interesting for future cooperative learning interventions with school students to conduct a previous program to develop students’ autonomy before the intervention. For this purpose, a second experimental group could be added in future studies with Primary School students.

Regarding the type of cooperative learning techniques or structures (as seen in Table 2 ), Fernández-Río et al. [ 34 ] used two: Learning Together [ 39 ] and Coop-Coop [ 40 ]. More cooperative learning structures can be observed in the study by Fernández-Río et al. [ 32 ], since they used several techniques as: Think-Share-Perform [ 41 ], Co-op Play [ 42 ], Collective Score [ 43 ], Learning Teams [ 41 ]. Learning Groups [ 44 ] and Pairs-Check-Perform [ 41 ]. Collective Score [ 43 ] was also used in the study by Fernández-Argüelles and González-González de Mesa [ 30 ]. Although it seems that this study used more cooperative learning structures during the intervention, the authors did not report more details. Finally, neither cooperative learning structure was found in the study by Navarro-Patón et al. [ 35 ] nor in the study by Cecchini et al. [ 33 ]. Based on the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis and the differences in terms of participants’ age and the program’s duration, it is not possible to determine whether some program types were more appropriate than others. However, an important implication of this study is possibly the inclusion of cooperative learning-based interventions in physical education teacher training programs. In this sense, further studies are needed to know which cooperative learning structures are more effective to improve students’ intrinsic motivation in physical education. In the future, the implementation of high-quality interventions as randomized controlled trials are recommended to obtained results of greater value.

The present systematic review with meta-analysis has various limitations. Firstly, the literature search was limited to two languages: Spanish and English. Therefore, the risk of exclusion of articles written in other languages was high. Secondly, the meta-analysis was conducted with a relatively small sample size, since only five studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria. Thirdly, the meta-analysis shows great heterogeneity and some of the studies analyzed are not of sufficient quality. Therefore, the interpretation of the results from this study must be taken with caution.

5. Conclusions

Cooperative learning interventions could be a useful teaching strategy to improve the physical education student’s intrinsic motivation since the overall effect size was significantly in favor of the experimental group. Program duration and participant’s age are relevant factors that must be considered by educators and researchers to conduct future effective interventions. In this sense, a student’s age may impair their execution of the program, given the complexity of the strategies carried out in the sessions. In addition, in terms of the duration of cooperative learning interventions, it is possible for them to achieve a significant and relevant improvement on intrinsic motivation when they last at least 12 weeks. Nevertheless, it is not possible to determine whether some program types are more appropriate than others. Given the very low quality of evidence and the large heterogeneity, these findings must be taken with caution.

Author Contributions

C.F.-E., M.T.A.R., and F.J.G.F.-G. designed and wrote the manuscript and interpreted the findings. F.J.G.F.-G. and B.J.A. supervised the study; M.T.A.R. and E.C.V. conducted the investigation; D.C.-M. and C.F.-E. analyzed the data; and E.C.V. and B.J.A. reviewed the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Our Content

- Success Stories

- Schedule A Demo

- Login / Register

Cooperative Learning in Physical Education

- Sean Fullerton

- February 15, 2023

Sean Fullerton is a former secondary physical education teacher and current Ph.D. student at the University of New Mexico in the Health, Exercise, and Sports Science Department. In this article, Sean explores a cooperative learning in physical education Be on the lookout for lots of great content from Sean as he helps take the academic angle of physical education best practices.

Organizing the learning environment in physical education (PE) can be a daunting task for teachers, especially with large classes. Physical educators should be prepared to “plan and implement developmentally appropriate learning experiences” and “engage students in meaningful learning experiences through effective pedagogical skills” (SHAPE, 2017; pp. 2-4).

Teaching strategies are ways to organize the learning environment for large group instruction Rink (2013). This article will discuss cooperative learning. Additionally, look at Mosston and Ashworth’s (2002) spectrum teaching styles which describe ten teaching styles from direct instructional strategies (i.e. command, practice) to indirect instructional strategies (i.e. learner initiated, self-teaching).

Teaching Styles for Large Group Instruction

Teaching styles are based on the amount of decision-making responsibility students are given in the learning process. Selecting the most appropriate teaching style and strategy depends on the curricular model, learning objectives, and students’ abilities. The learning environment for large group instruction can be organized in two ways:

1) varying the level of responsibility and engagement of the learner with the content (teaching style)

2) organizing learning activities where the learner and teacher act in different ways (teaching strategy) (Rink, 2013).

What is Cooperative Learning?

Cooperative learning is a learning strategy where students work together in a group to complete a task or project. The cooperative learning strategy emphasizes social interaction with an understanding that valuing diversity and working with others are important in the real world (Rink, 2013). Cooperative learning can stimulate learning as well as personal and social development. Multiple teaching styles can be used within cooperative learning.

For example, in the Sport Education curricular model (Siedentop et al., 2011), the teacher can use both practice and divergent production styles as students plan their practice session within their teams. Divergent production teaching style is when students solve problems posed by the teacher for which there are many correct answers, such as creating practice drills to focus on offensive strategies, or creating warm-up routines before practice or workout sessions. Practice teaching style is when students practice a skill or task, and provide feedback to each other based on skill cues.

Free Professional Development For PE

From full courses to on-demand webinars, tap into the PLT4M classroom for continuing education opportunities for physical education teachers.

Best Practices For Cooperative Learning

For cooperative learning, Rink (2013) recommends that learners are assigned and grouped heterogeneously (of varying abilities, interests, knowledge, etc.). For cooperative learning to work, students must be provided clear expectations regarding roles, expectations, steps, resources, time frame, and assessment process (Rink, 2013).

The student success office at the University of Waterloo provides a tip sheet titled “ Working effectively in groups ” that has tips for organizing group work, suggested roles and responsibilities, and solutions to common challenges. In the Sport Education model, there are roles assigned within the model, such as coach, trainer, referee, score keeper, etc. (Siedentop et al., 2011). UC-Irvine’s Teaching, Learning & Technology Center provides an example group contract including recommendations for instructors when utilizing contracts as a part of group learning. Each curricular model provides recommendations and resources for materials as well.

Depending on the learning style, usually, the teacher selects thet task or project, but students can have a say in deciding the specific goal that they are to achieve (Rink, 2013). It is important that something authentic should be learned and this learning requires cooperation, and the experience is designed to develop the interdependency of the group members (Rink, 2013).

The progression in which the group moves through tasks should be built in, or left to the learners, depending on the task and their ability levels (Rink, 2013). Timelines or checkpoints are suggested when completing long-term projects so that the teacher can provide feedback and the group can move forward in a timely manner (Rink, 2013). The teacher should offer suggestions or alternative strategies if the group is stuck.

Cooperative Learning For Fitness and Wellness Curriculum

Cooperative learning can be used for fitness and wellness curriculum. In which, it may be better to group students homogeneously, based on similar abilities or goals, however, their prior knowledge and experience is likely to vary.

Reciprocal teaching style can be used for students within the group to complete health-related fitness assessment. Reciprocal teaching style is when students work together while one performs a task, and the other provides feedback. In this example, students can select how they want to assess a component of health-related fitness. At the secondary level, students can choose push-ups, the YMCA bench press test, the modified pull-up test, or isometric push-up test to measure muscular endurance and are tasked with applying proper testing procedures.

Technology could be used to provide instructions for assessments. For projects, cooperative learning can be used for students to design, implement, and evaluate a fitness program. Members will be tasked with completing pre-assessments, designing the program, following the program, and monitoring progress, and conducting a post-assessment to evaluate program effectiveness.

Within this project, students can be assigned roles within their group:

- Student 1 can be a “coach”, in charge of proper exercise techniques.

- Student 2 can be a “trainer”, in charge of warm-up and cool down based on the workout.

- Student 3 can be a “Program designer”, in charge of exercise selection, ordering, and periodization, and the application of progressive overload.

- Student 4 can be a “manager” in charge of spotting, safety, and time management. Students should be given clear responsibilities for their roles and provided feedback from peers and their teachers.

It may be appropriate to combine other teaching strategies within a fitness and wellness curriculum that involve interactive teaching (teacher-led), self-instructional strategies (student-led), or peer teaching (student-led, with assistance).

Key Takeaways on Cooperative Learning

Ultimately, the teacher must select the most appropriate teaching strategy to offer the best learning environment for students to accomplish the learning objectives. The curricular model, student abilities, and learning outcomes provide a starting point for selecting the most appropriate teaching strategy.

Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (2002). Teaching physical education (5th ed.). Boston: Benjamin Cummings.

Rink, J. E. (2013). Teaching Physical Education for Learning . McGraw-Hill Education.

SHAPE America – Society of Health and Physical Educators (2017). National Standards For Initial Physical Education Teacher Education.

Siedentop, D., Hastie, P., & Der Mars, V. H. (2011). Complete Guide to Sport Education (Second). Human Kinetics.

More Articles From Sean Fullerton

Personalized System of Instruction in Physical Education

Student Centered Learning Examples Using Technology

5 Tips To Technology Use In Physical Education

Understanding Motivational Theories in Physical Education

Flipped Learning in Physical Education

Share this article:

Recent Posts

Middle School Health Curriculum

How To Improve Mental Health In Schools

Health Education Curriculum

Interested if plt4m can work at your school.

What does your Middle School Health Curriculum look like?

PLT4M's middle school health curriculum can empower students with the knowledge and skills to make healthy choices now and into the future!

“We want students to lift and exercise in high school, but also for the rest of their lives. That means we want to develop lifelong skills that promote health and safety throughout our classes.”

Life Lessons & Lifting - Inside The Waynesville Weight Room

At Waynesville High School, students are working hard, seeing results, and building lifelong physical and mental skills.

In what ways can our schools, specifically PE and Health Departments, mitigate the mental burden our students are currently under?

We explore how to improve mental health in schools using physical education and health classes as a conduit for success.

PE Final Exam. PT and then graphing progress/data in the Athletic Training Facility. @BR_Schools @plt4m

“When we give students more choice, they are more likely to engage. Choice has helped students staying on task, working hard, and seeing health and wellness benefits.”

Paradise PE's Push For Student Choice and Engagement

Paradise High School in Arizona has pushed for student choice in physical education that has led to new levels of student engagement.

Empower kids to say “YES” to a healthy lifestyle and “NO” to underage drinking! PLT4M is proud to now offer easy-to-implement lesson plans from Ask, Listen, Learn: Kids and Alcohol Don’t Mix, a program from http://Responsiblity.org. @AskListenLearn

Underage Drinking Prevention Lesson Plans

Underage drinking prevention lesson plans empower kids to say “YES” to a healthy lifestyle and “NO” to underage drinking.

The leader in quality Physical Education, Athletics, and Fitness equipment for 75 years.

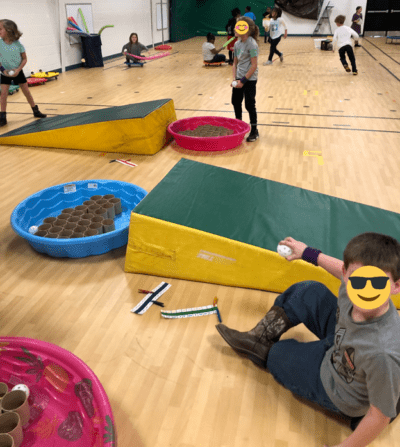

4 Team Building Activities for Students

One of the best ways to start your school year is to get your students active and working together! Team building activities for students, also referred to as cooperative games, can be a great way to see which students work well with everyone, which work well with certain students, and which students struggle to work well with anyone. We all know we have the full range in any given class, so hopefully incorporating some team building activities and games will bring the entire class together.

My Favorite Cooperative Games for PE:

1. island movers.

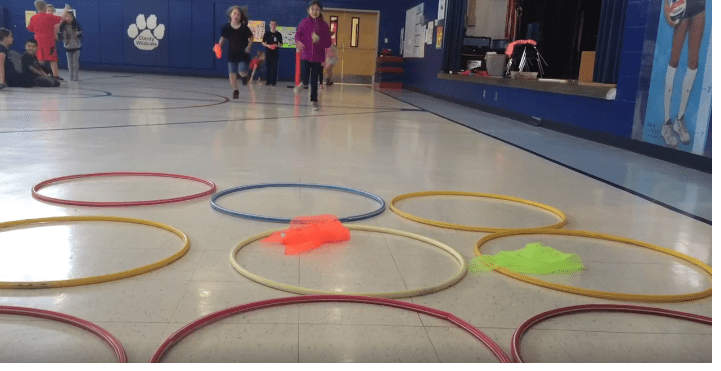

One of my favorite cooperative games to do when I taught elementary students was Island Movers! The game involves as much or as little equipment as you want to allow. The idea of the game is for students to use the equipment you give them to get everyone in their group from one end of the gymnasium to the other without anyone touching the “shark-infested waters,” aka the gym floor! Feel free to play some Jaws -themed music too!

- Split class into small groups of 4 or 5 students each for the first couple of rounds. Then make the groups the larger as you go.

- Start each group with one piece of equipment per person in the group. If they master that, remove a piece of equipment. Examples of equipment: poly spots , carpet squares, cones , jump ropes , scooters , cardboard boxes, etc. Ensure you give each group the same pieces of equipment.

- Allow students to work together to cross the shark-infested waters.

- On the last day of this activity, I make this a class challenge and the entire class must work together to accomplish the task.

- End each round with a quick debriefing. This is a time to ask your students to share what worked and what didn’t. It also allows students to try a different group’s idea.

- This is a team building activity, so make sure that all groups realize this is NOT a race.

- If a group is finished, encourage those students to cheer for the other groups.

- Mix up the groups each round so the students get to work with everyone in the class.

2. Buddy Walking

Another team building activity that I have done is called Buddy Walking. This is a fun activity that I encourage you to record on video the first and last day of the activity to see how far the students’ teamwork skills have grown and improved. Everyone will have a good laugh; and, to be quite honest, being able to laugh together is another great way to bond!

I liked to use the Team Walker Sets from Gopher for this activity. However, if you are low on funds and handy, you can make your own set with some 2×4’s and rope. The idea is to get students to think, communicate, and walk as a group from Point A to Point B. Some students will take charge and lead their group in a cadenced march, while others will struggle to work together. Again, this is why debriefing is crucial! It will allow students to hear success stories!

3. Geacaching

Geocaching or treasure hunting is an activity that can be done in small groups or as a whole class and can be a tremendous amount of fun! You are in control of how complex you would like to make this adventurous lesson. I have never had GPS units in my PE closet, but if you can purchase a couple I would recommend it! The units range in cost and complexity, so pick what you feel comfortable using and teaching! And if you don’t have the funds to purchase GPS units, dig deep into your National Treasure skills and create maps of your own for your students to follow. The great part about creating clues to use is that you can pull classroom concepts into PE class, again this all depends on how elaborate you want to make the lesson/unit. I have done this as a search-and-rescue mission utilizing clues that they must follow to get to a specific destination. Along the way as they get to each clue, I like to add different exercises that they must complete as a group before moving onto the next clue. A word of caution, this is not the best thing to do within the halls of your school, it can be a little loud! Shop Geocaching supplies.

4. Team Cooperative Counting Game

My last suggestion, and I still use this at the high school level, is a counting game. I call it team counting, and I would say this is better for your upper elementary students. There is no equipment necessary and you can use it inside or outside!

If you have a class of 20 students, the idea is for the class to count from 1 to 20, but each student is allowed to call out only one number.

- Students sit or stand in a circle and are not permitted to count straight down the line or around the circle.

- If two students call out a number at the same time, they must start back at 1.

- If there is a long pause, I usually go with 3 or 4 seconds, then they must start over.

Depending on the class, this task can be done quickly or it may take them 10 minutes or they may never get it. I suggest not letting them struggle to the point where they don’t get it, give them some hints. The hint I use is that once a student has secured a number that they called out, they should always be the person to call that number. Again, debriefing with your class at the end is crucial, because you can talk about different strategies and how they as a class worked together to solve a tricky problem. As an extra little bonus, I use this with my track team and they must do wall sits while trying to work together to count from 1 to however many are in my sprinter/hurdler/jumper group.

Final Thoughts

I know the thought is to use team building activities for students at the beginning of the year and I agree it is important, but I would al o gauge your classes throughout the year. I know when I taught elementary school PE, there were times in the year when I pulled these back out because I felt it was necessary to get everyone back together. This is especially true as they get older because hormones kick in, friendships form, and sometimes you can tell classes are excluding some kids. That never leads to anything positive! I also want to point out that these activities are meant to be fun, and if you notice your students getting frustrated just stop and have a debriefing session to talk things out. If your students are extremely frustrated and you don’t help them work through this, you will have accomplished nothing! Good Luck! Shop team building equipment options.

Interested in More Team Building Activities for Students?

- Back-to-School Icebreakers and Team Building Activities by Maria Corte

- Break the Ice! Team Building 101 by Chad Triolet

- Creative Ways to Integrate Fitness with Team Building into PE by Jessica Shawley

Team Building Equipment

About the Author:

Jason Gemberling

2 responses.

Hi buddy, This is a great article! There is definitely some very useful and valuable information in here that I will be keeping for my future resources. Thanks for sharing such a great article!

Thanks for taking the time to read the article! I am glad that you found the information helpful! If you ever have any questions, do not hesitate to send me a message!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The leader in quality Physical Education, Athletics, and Fitness equipment.

Featured Resources

5 ways small sided games make a big impact, author: jessica shawley, a brand new tool for pe you didn’t know you needed, author: brett fuller, 5 skill-based floor hockey games, author: michael beringer, 16 parachute team building activities, author: tim mueller, we're social, motivating unmotivated students, author: dr. robert pangrazi, jessica shawley, and tim mueller, promoting activity and success through adapted pe, author: dr. robert pangrazi, marci pope and maria corte, author: randy spring.

JOIN OUR NEWSLETTER

Sign up to receive the latest physical education resources, activities, and more from educational professionals like you straight to your inbox!

- DOI: 10.4324/9780203132982

- Corpus ID: 141851553

Cooperative Learning in Physical Education : A research based approach

- Ben Dyson , Ashley Casey

- Published 2012

199 Citations

Cooperative learning as formative approach in physical education for all, cooperative learning in physical education encountering dewey’s educational theory, physical education and university: evaluation of a teaching experience through cooperative learning, the implementation of models-based practice in physical education through action research, cooperative learning: a relevant instructional model for physical education pre-service teacher training, research the implementation of models-based practice in physical education through action, the challenges of models-based practice in physical education teacher education: a collaborative self-study, action research in physical education: focusing beyond myself through cooperative learning.

- Highly Influenced

Using Best Practices when Implementing the Cooperative-Learning Theory in Secondary Physical Education Programs

Elements and skills of cooperative learning for student learning in physical education, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The efficiency of cooperative learning in physical education on the learning of action skills and learning motivation.

- 1 Department of Physical Education, Dongguan Polytechnic, Dongguan, China

- 2 Department of Computing Engineering, Dongguan Polytechnic, Dongguan, China

- 3 Department of Logistics Engineering, Dongguan Polytechnic, Dongguan, China

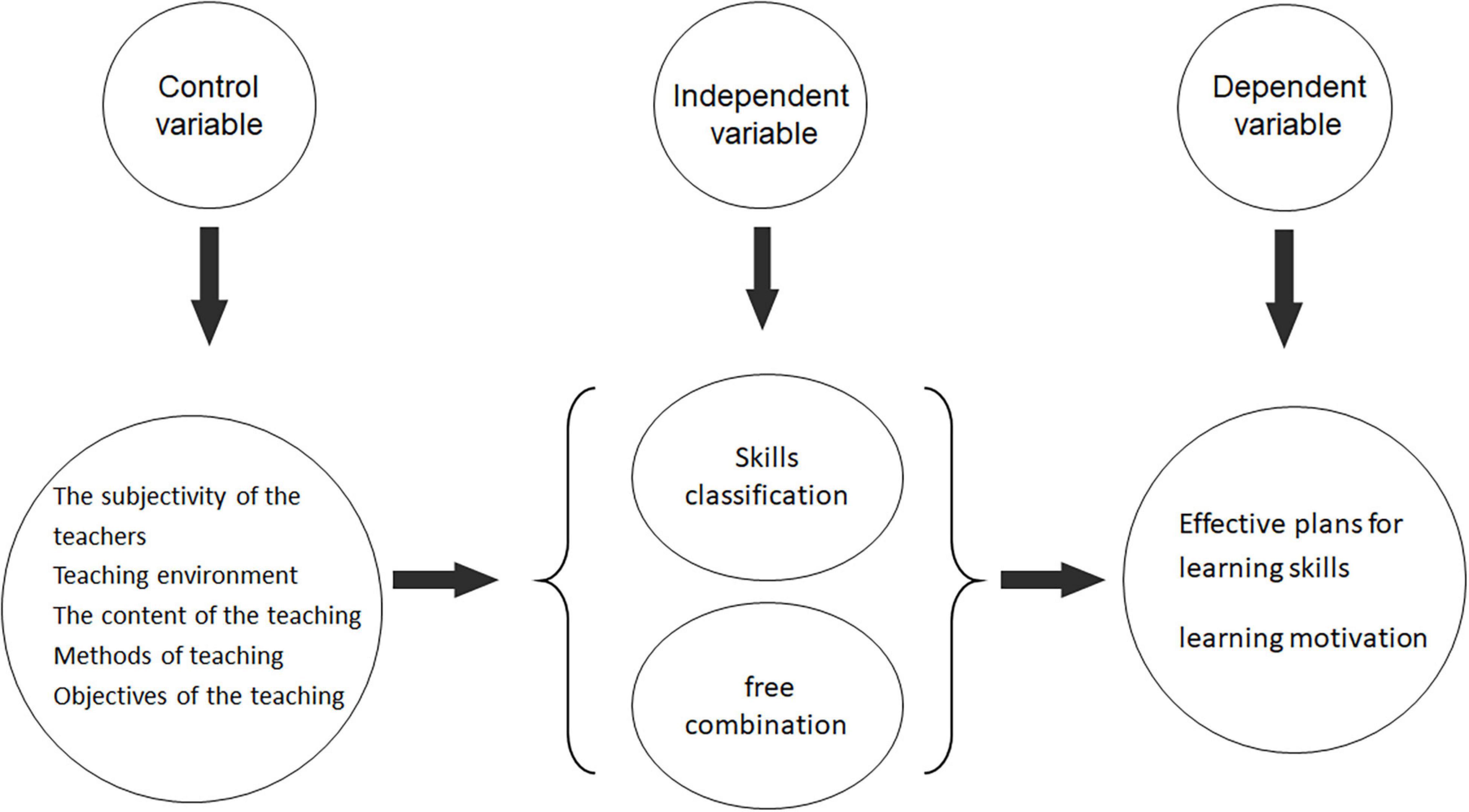

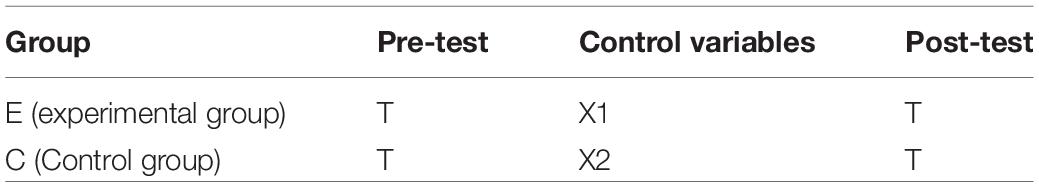

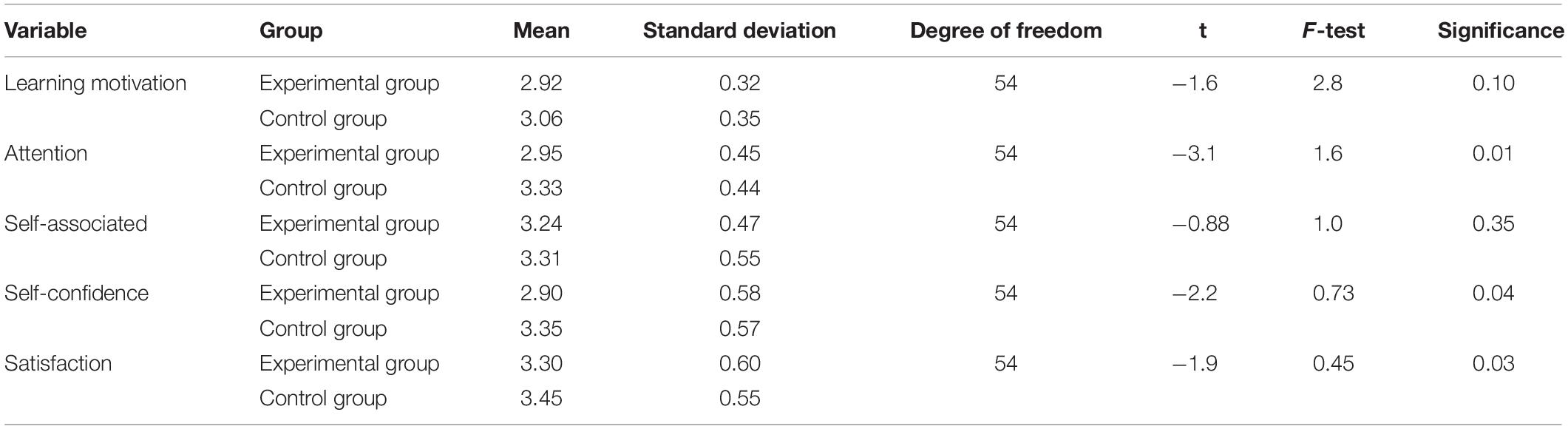

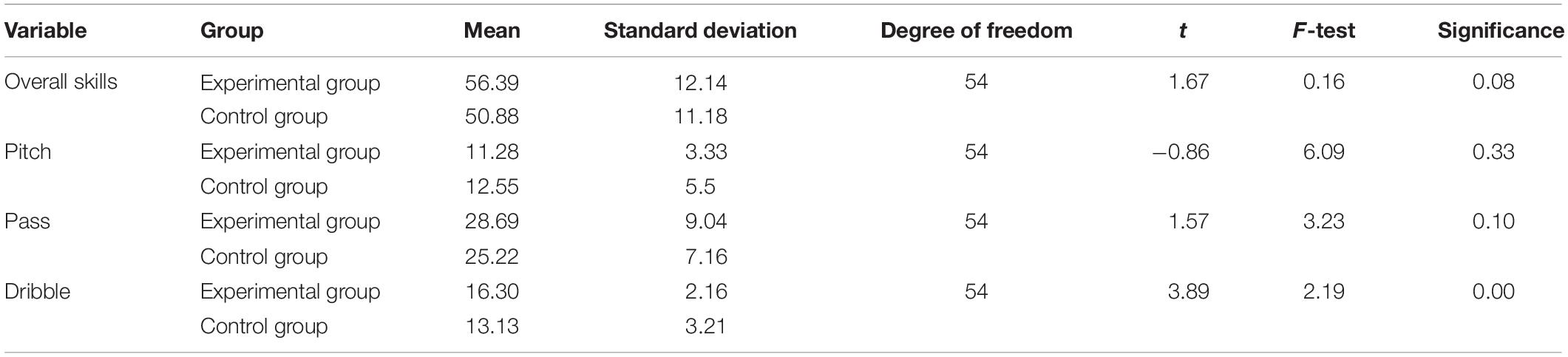

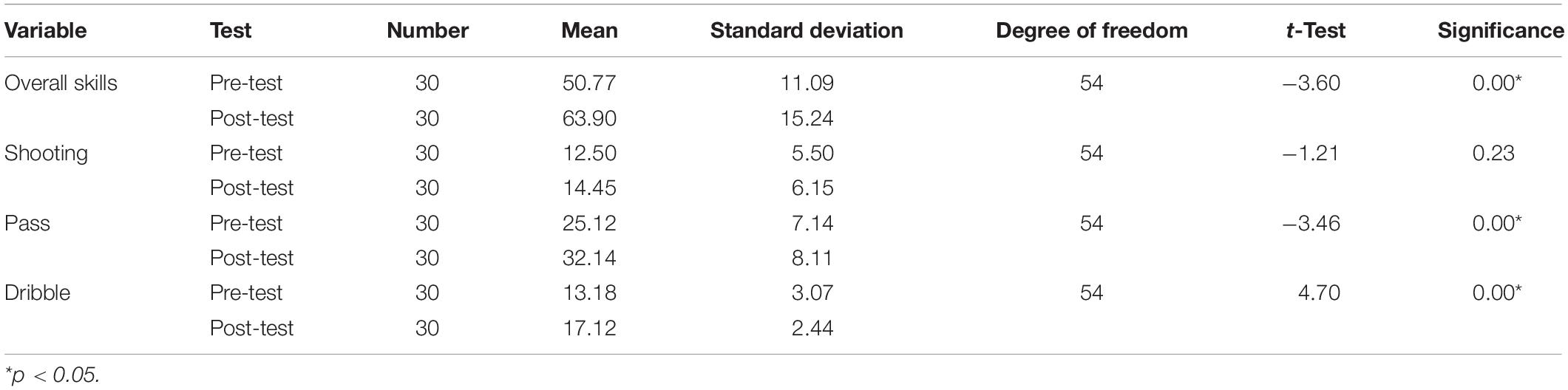

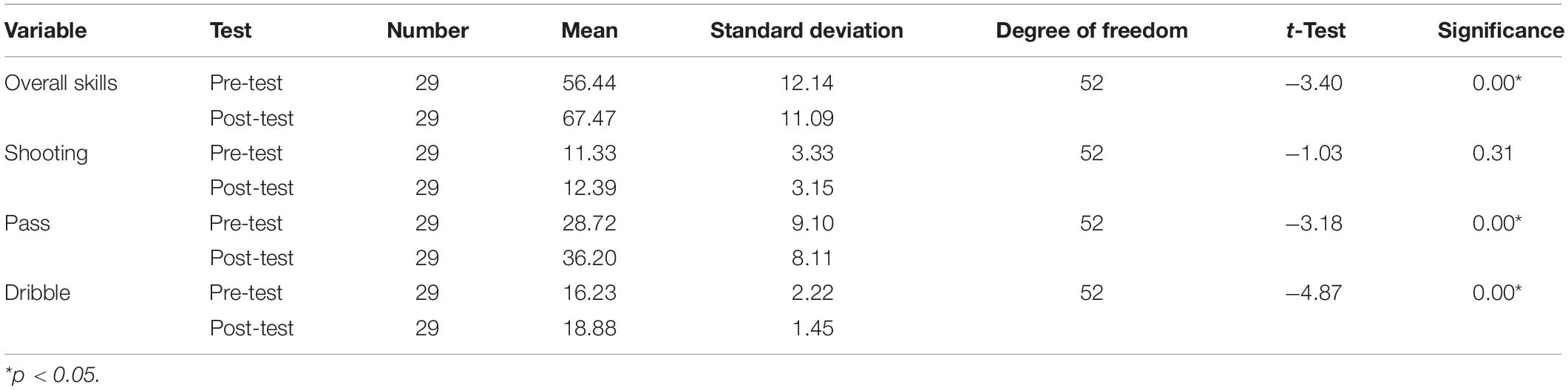

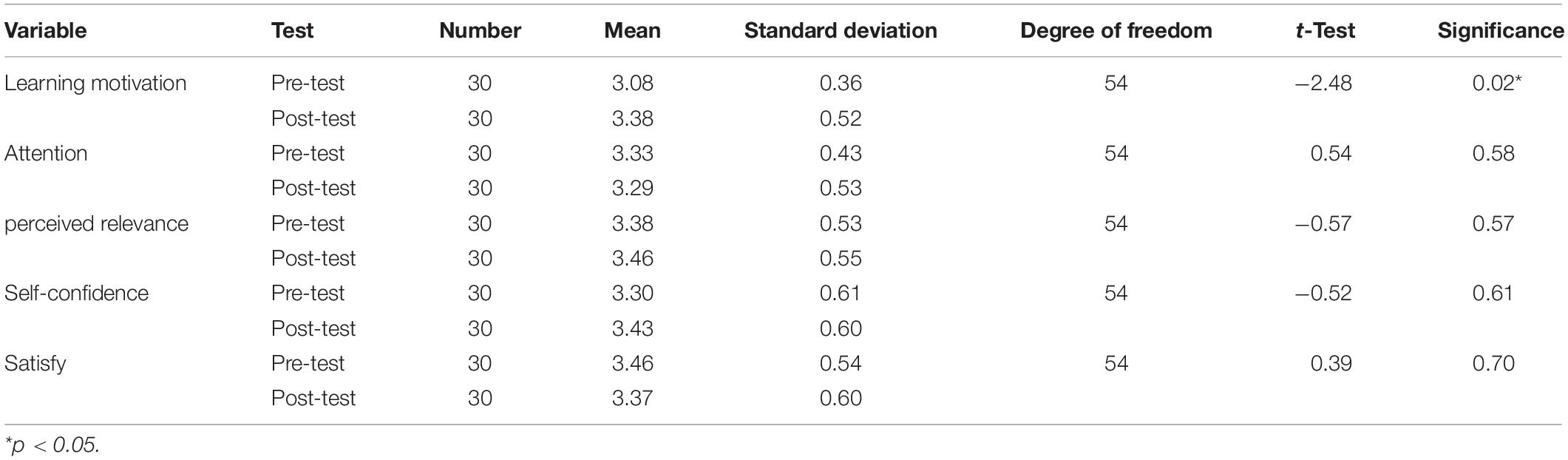

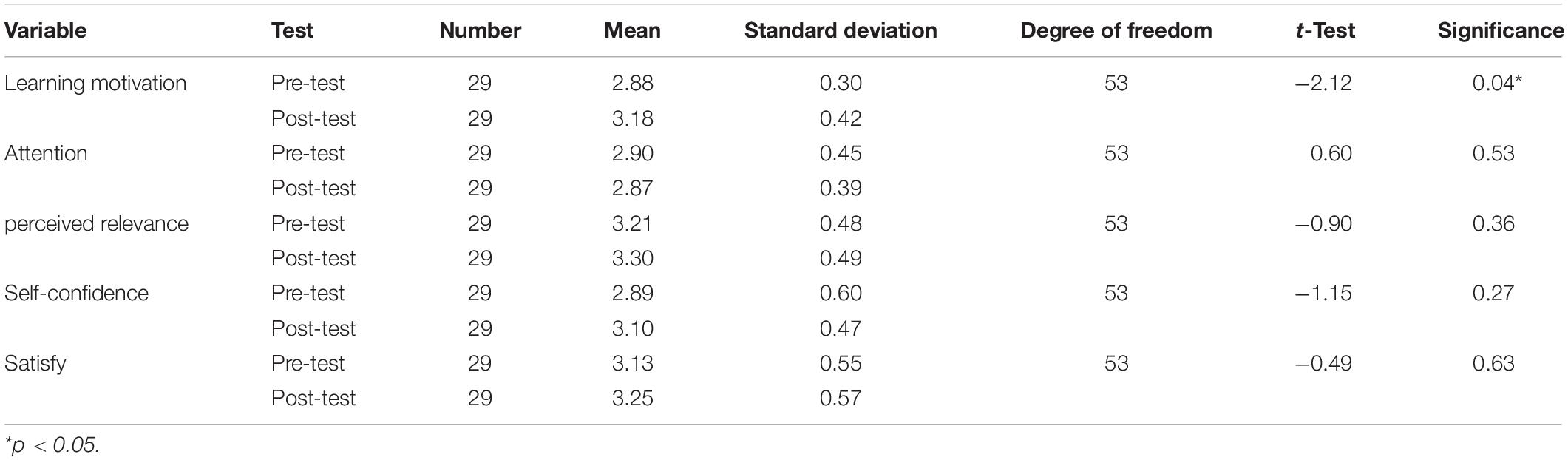

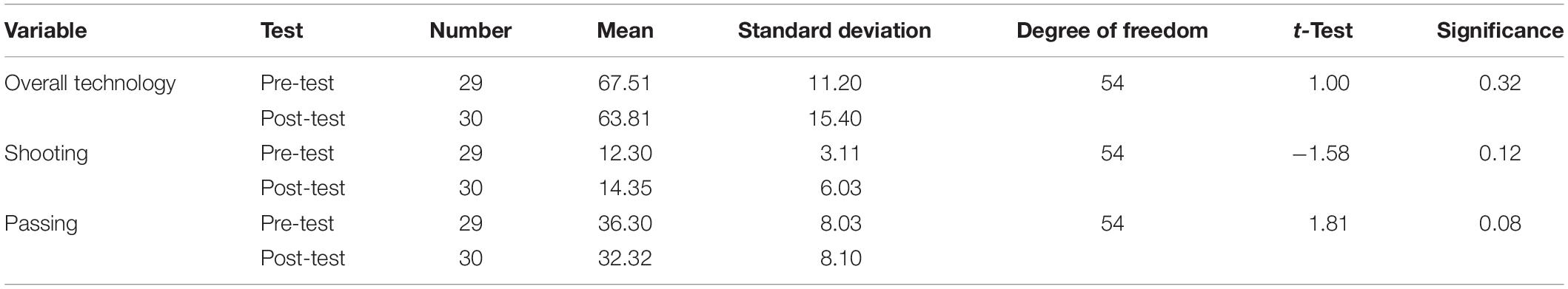

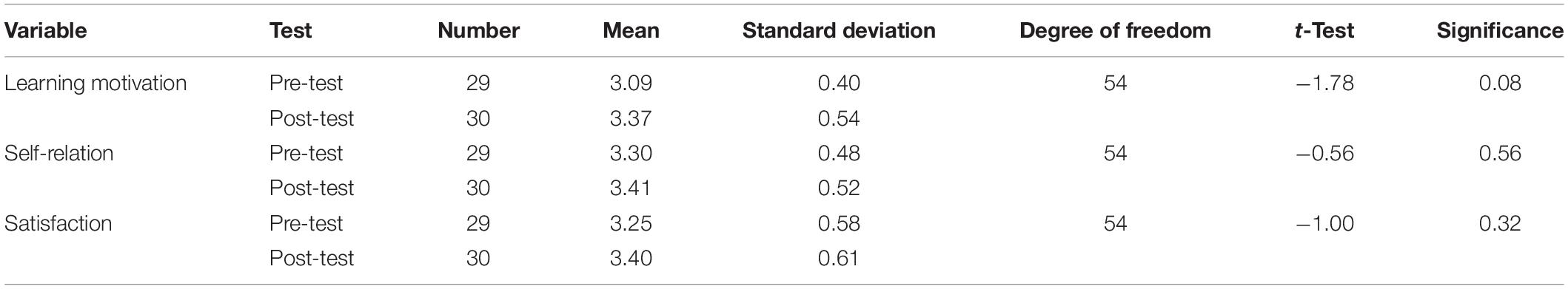

- 4 Department of Computer Science and Information Management, Soochow University, Taipei, China

This paper proposes a cooperative learning method for use in physical education, involving two different grouping methods: S-type heterogeneous grouping and “free” grouping. Cooperative learning was found to enhance the effectiveness of basketball skills learning and learning motivation. A comparison was made of the differences between action skills grouping (the control group) and “free” grouping (the experimental group). The ARCS Motivation Scale and Basketball Action Skills Test were used to measure results, and SPSS statistical analysis software was used for relevant statistical processing (with α set to.05). The results showed that overall skills, dribbling and passing among the action skills groups and “free” groupings significantly improved, but results for shooting were not significant; motivation levels for the two grouping methods significantly improved overall, and no significant differences in learning motivation and learning effectiveness were found between the different grouping methods. It is clear that teachers should first establish a good relationship between and with students, and free grouping methods can be used to good effect. Teachers using cooperative learning should intervene in a timely manner and choose suitable grouping methods according to the teaching goals.

Introduction

Physical education is based on physical activity and focuses on training physical fitness and improving health. In the past, physical education in schools was often regarded as marginalized or was not considered a suitable subject to study at higher education level, compared with other subjects. However, Spencer pointed out in the life preparation theory that the purpose of education is to prepare young people for a fulfilling and successful life in the future. Physical health and self-discipline are therefore highly important and are directly related to survival. The representative indirectly pointed out that the most valuable courses are those in the fields of health and physical education. In addition, many scholars have pointed out that in physical education, students can experience the fun of sports through sporting activities, and they can develop their sports skills along with personal and social skills. Sporting activities can help establish harmonious interpersonal relationships and enable individuals to develop appropriate ethical (sportsmanlike) and team behaviors, and they are an effective way to build self-confidence. Furthermore, exercise has the following benefits: it stimulates the brainstem and helps regulate neurotransmitters in the brain; it helps reduce anxiety and relieve stress; it improves strength; it can improve memory, learning ability and concentration; and it can promote feelings of well-being. The importance of physical education is therefore clear to see ( Chen et al., 2019a ; Bai et al., 2020 ).

Health has long been a topic of concern for people, and it has the most direct relationship with survival. In holistic terms, five elements of health and well-being are recognized: physical fitness, emotional fitness, social fitness, spiritual fitness and cultural fitness. Social fitness emphasizes active interaction with others and the ability to develop friendships. Ten basic abilities have been identified, associated with physical education, including respect, care and teamwork. The 12-year national education curriculum has developed the concept of “spontaneous,” “interactive,” and “shared good” in the nine years since its introduction, and the importance of this for children’s learning has been actively promoted in recent years.

The concept of teamwork and cooperation has always been valued, and the importance of cooperation has been mentioned many times in the major domains of education, and is reflected in fitness ability indicators. It can be seen that physical education can create an ideal context for cooperative learning. Acquisition of action skills in physical education is not something that happens automatically as children grow and mature, but it can be enhanced by external factors such as practice, guidance and encouragement. Cooperative learning provides these opportunities and is an effective teaching method that is advocated by experts and scholars. It can shape teamwork situations, and students can develop the ability to communicate, cooperate and coordinate with others in the process. Social skills can be enhanced at the same time, through mutual encouragement, teaching, explanation and other interactions between peers. Cooperative learning can stimulate individuals’ inner motivation, improve attitudes to learning, improve learning effectiveness and help young people achieve key learning goals. Many studies in the past have pointed out that cooperative learning can not only improve the effectiveness of learning but also make learning more enjoyable ( Chen et al., 2015 , 2021e , 2019b ).

In addition, cooperative learning is also effective in promoting subject knowledge and problem-solving abilities. Assessing the effectiveness of learning has always been an important aspect of physical education (as with other subject areas), enabling teaching and learning outcomes to be evaluated and improvements and next steps to be explored further. Various factors will affect the effectiveness of learning. Studies of heterogeneous grouping have found that it helps to promote interaction between students, cultivate social skills, increase learning effectiveness and improve learning motivation. Cooperative learning almost equates with heterogeneous grouping. In physical education, the heterogeneous grouping method mostly involves skill-performance grouping, and most studies have pointed out that such a heterogeneous grouping method is beneficial to the learning of all group members. Better performing individuals can assist those with poorer skills so that the latter can obtain feedback on their performance and improve, and those with better skills can reorganize and improve their own performance by teaching other team members.

In this research, cooperative learning was applied to physical education classes in order to explore the impact of different grouping methods on learning effectiveness and learning motivation ( Chen et al., 2020 ). Based on the research background and motivation, the aim of this study was to explore the impact of different cooperative learning grouping methods in relation to action skills learning and learning motivation. Quasi-experimental research methods were used so that the results could serve as a reference for physical education and future research.

Research Questions

The following research questions were formulated:

(1) What differences can be seen (before and after testing) between action skills groups and “free” groupings in relation to the effectiveness of cooperative learning?

(2) What differences can be seen (before and after testing) between action skills groups and “free” groupings in relation to motivation in cooperative learning?

(3) What differences can be seen between action skills groups and “free” groupings in relation to performance of action skills in cooperative learning?

(4) What differences can be seen (pre- and post-test) between action skills groups and “free” groupings in relation to learning motivation in cooperative learning?

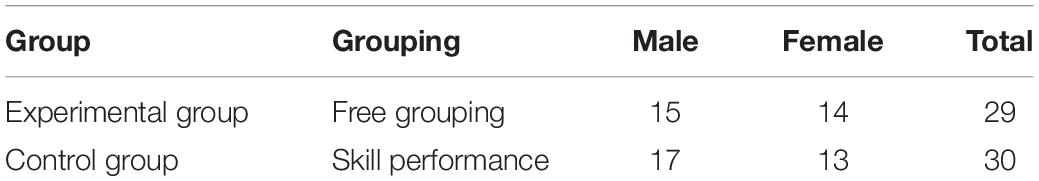

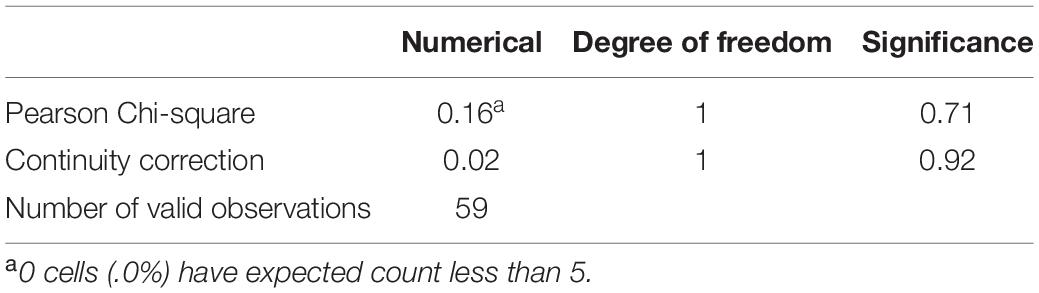

Research Participants

(1) Research participants: Intentional sampling was used in this study. Two classes of students were selected as the research participants (59 participants in total). There were 29 students in class A (15 males and 14 females). Free grouping was adopted, and this was the experimental group in the research. Class B comprised 30 students (17 males and 13 females), grouped according to S-type heterogeneous action skills, and this was the control group.

(2) Research time: The implementation time for this research was from March 2019 to May 2020, a period of six weeks. There was a total of 12 lessons. One physical education lesson took place (45 min per class) every Monday and Thursday afternoon throughout the study period. The teaching strategy of cooperative learning was used to carry out physical education basketball teaching.

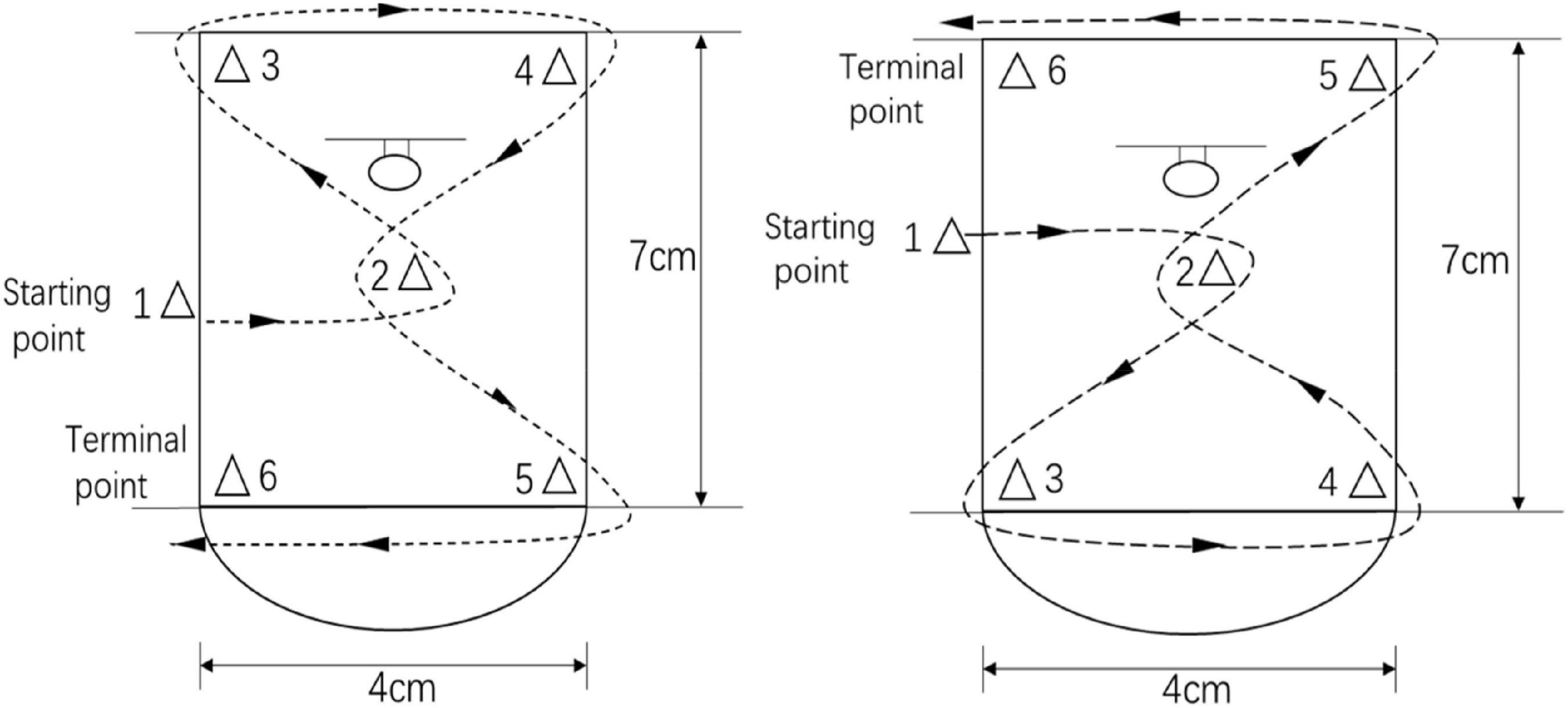

(3) Teaching content: In this study, a self-designed cooperative-learning teaching strategy was integrated into the basketball unit. The teaching content included basic basketball passing, dribbling and shooting.

(4) Research test restrictions: The ARCS Motivation Scale and the Basketball Action Skills Test were used in the pre- and post-tests of the study. Therefore, the pre-tests may have affected the post-tests.

Interpretation of Terms

(1) cooperative learning.

This is a structured and systematic teaching strategy to promote group learning. Group members participate in the learning together, and peers have a mutual relationship of success or failure and help one another to achieve the learning goal. For this research, two types of student group achievement differentiation (STAD) were used, and group game competition (TGT) to design teaching plans.

(2) Action Skills

In this research, the action skills consisted of dribbling, passing and shooting in basketball. Dribbling refers to the speed of the dribbling movement using the left and right hands; passing refers to the accuracy and speed of passing and receiving the ball bounced against the wall; shooting refers to the ability to shoot and pick up the ball (from the same distance) and shoot the ball into the basket.

(3) Different Grouping Methods

The different grouping methods in this study refer to free grouping within the limit set for the number of members and S-type heterogeneous grouping according to the performance of action skills. Participants were divided into five groups, with five to six people in each group. Once the groups had been set, they stayed as they were until the end of the study. The terms used for groups are defined separately as follows:

“Free” Grouping

Students could group themselves according to their own wishes, with at least five people in each group and a maximum of six people.

S-Type Heterogeneous Grouping of Action Skills

Action skills were defined as described above. The basketball skills test developed for the study was used as the test method. The pre-test scores obtained were ranked from high to low and were used as the basis for dividing the participants into five groups, each containing five to six people: 1∼5, 6∼10, 11∼15, 16∼20. The scores for the first group were 1, 10, 11, 20, 21, and 30. The scores for the second group were 2, 9, 12, 19, 22, and 29. From less to more, more to less, and so on.

Effectiveness of Action Skills Learning

Learning effectiveness is critical to teaching and learning outcomes. Learning effectiveness refers to the degree to which students achieve particular teaching goals. However, there may be a range of these, e.g., the main learning, auxiliary learning, cognition, motivation and skills. The action skills learning effect referred to in this research refers to the passing, dribbling and shooting scores obtained by students after the cooperative basketball lessons.

Literature Review

The connotations of cooperative learning.

Cooperative learning is a type of teaching. It means that two or more learners become a learning unit. Through the interaction of group members and the sharing of responsibilities, learners can achieve common learning goals. In this process, each learner must take responsibility for team members. This kind of teaching is learner-centered and can provide students with opportunities for active thinking and more interactive communication. Cooperative learning is a learning activity that establishes a common goal between group members, who then work together toward this, cooperate and support one another. Through the cooperation of peers, the effectiveness of individual learning is improved, and group goals can be achieved. For learning to be fully cooperative, it needs to have the following three key elements: promotion of positive interdependence; personal performance responsibility; face-to-face interaction. Cooperative learning is a structured and systematic teaching strategy, which is less subject to the restrictions of subjects and grades. Teachers can help meet the needs of students of different genders, abilities, socioeconomic backgrounds, races, etc.

After getting into groups, the whole group establishes a common goal. All group members are responsible for themselves and for the others. They encourage and assist one another in order to achieve the learning goals. Teachers arrange suitable cooperative learning situations and group students in a heterogeneous manner, providing guidance to students to help them cooperate, learn from one another, share resources and achieve learning goals together, which not only contributes to learning achievement but also to motivation levels. Cooperative learning is a systematic and structured teaching strategy, which supports learning outcomes and also students’ communication and social skills ( Chettaoui et al., 2020 ; Chen et al., 2021d , e ).

Cooperative Teaching Methods

Teachers can choose appropriate teaching methods to apply in the classroom according to teaching goals, student characteristics and the characteristics of the subject being taught. Cooperative learning methods are divided into three categories, according to the teaching situation. The first type is communication, which focuses on sharing (and discussion) of ideas among group members; the second type is that of proficiency, which focuses on the content of the course; and the third type is inquiry, which focuses on guiding groups as they explore set tasks and solve problems. Below, five other methods commonly used in physical education will be introduced, along with the student group achievement differentiation (STAD) method used in this research.

Students’ Team Achievement Differentiation Method

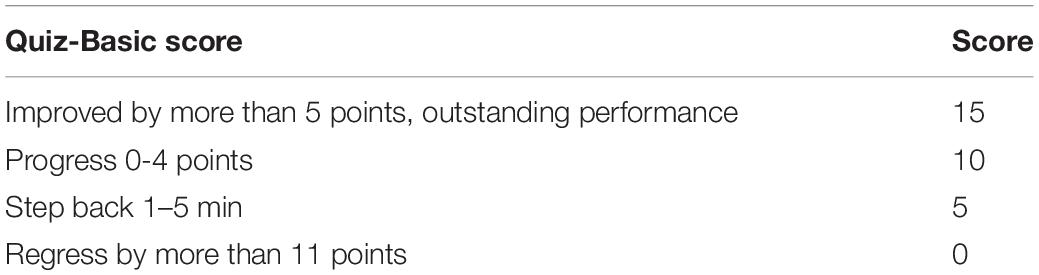

The student group achievement differentiation method is the most straightforward and easy-to-implement cooperative learning method. This implementation and evaluation method is similar to traditional teaching methods, but it also has other special benefits, such as group rewards, individual responsibilities and equalization. The test method ascertains the progress scores of each group member and the entire group, meaning that the effort and achievement of all students can be recognized and celebrated. Progress scores are used to confirm the extent to which teaching goals are achieved. The STAD process may involve whole-class teaching, group study, quizzes and calculation of personal progress scores. For the purposes of this study, participants’ individual scores (before cooperative learning) were calculated for each group member, and the detailed score comparison is shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. Personal progress score conversion table.

Research Relating to Cooperative Learning

Cooperative learning began to develop after establishment of the Cooperative Learning Centre. Many experts and scholars have successively proposed cooperative learning-related teaching strategies and methods, and related research has also continued to develop. The research objects range from kindergartens to colleges and universities. In the field of sports, colleges and universities are the main users. A meta-analysis of relevant literature on cooperative learning showed that 80% of the results indicate that cooperative learning can have a positive impact on learning effectiveness; 13% of the results showed that there is no difference between cooperative learning and general teaching methods; 12% of the results showed use of the one-class teaching method, which has better learning results than cooperative learning. From the above meta-analysis, it was found that not all cooperative learning has positive effects. This research explored the relationship between cooperative learning and physical education. From previous literature, it was found that cooperative learning can be used in different projects and different stages of learning, and it can be combined with other teaching methods so that students’ cognition, skills and motivation can be enhanced ( Chou et al., 2015 ; Chiang and Yang, 2017 ; D’Aniello et al., 2020 ; Ding et al., 2020 ).

Not all results support the positive impact of cooperative learning in physical education classes, but few studies have found there to be no positive impact. Most of the results show that cooperative learning is a highly feasible teaching method and can be used not only in team sports such as baseball, football and volleyball but also in activities involving a small number of people or individual sports such as tennis, badminton, billiards and gymnastics. Outcomes are not dependent on the learning stage, and cooperative learning is suitable for all ages of students, including college students.

In the past, related research variables applied to physical education classes included learning effectiveness, learning motivation, interactive behavior, critical thinking, physical activity, etc. Among these, learning effectiveness has received the most attention. Not only has the learning effectiveness of action skills been found to improve but also interpersonal, communication and social skills. Furthermore, personal motivation is stimulated during interaction ( Dyson, 2001 , 2002 ).

Studies have shown that cooperative learning can improve learning effectiveness, physical activity and learning motivation more than traditional independent learning methods. Previous research into application of cooperative learning in physical education classes has yielded promising results, showing that cooperative learning is more efficient than learning in isolation or competitively. Cooperative learning is a well-established teaching method, and it is a common strategy in the field of research and teaching. Since most studies show the positive impact of cooperative learning, how to bring the greatest positive impact using this learning strategy is worthy of in-depth discussion ( Dyson et al., 2004 ; Chen et al., 2021a ).

ARCS Motivation Scale

ARCS learning motivation theory is based on comprehensive integration of different forms of learning motivation and related theories in the United States, such as cognitive school attribution theory, behavior school reinforcement theory and other theories proposed by the motivation model. This theory is based on the premise that learners’ internal psychological factors, teachers’ teaching designs and learning effectiveness are closely related. These are important factors affecting the effectiveness of learning. It is believed that traditional teaching designs have, in the past, ignored learners’ motivation for learning. If learners are not interested or are unable to focus on learning, the effect of learning will be greatly reduced. The ARCS motivation model provides teachers with a better understanding of students’ motivational needs, so that they can design courses based on learners’ needs in order to stimulate learning motivation and enhance learning effectiveness. ARCS constitutes a relatively complete set of motivational factors. It is not restricted by age and is applicable to all learning stages. Therefore, the ARCS Motivation Scale is often used to investigate student learning motivation. ARCS stands for “Attention,” “Relevance,” “Confidence,” and “Satisfaction,” which are key to learning that stimulates motivational levels and attracts the attention of learners ( Fu et al., 2018 ).

Students’ interest is linked to the perceived “relevance” for them personally and to feelings of “self-confidence” in terms of students’ perceived ability to achieve their goals. Finally, it is important for students to feel a sense of “satisfaction” from the learning process. ARCS emphasizes that in order to arouse students’ learning motivation, the above four elements must be provided for in order for teaching to be effective.

Grouping Method for Physical Education Classes

An important step before implementation of teaching in cooperative learning is to group students. It is important to group students appropriately so that they will not resist psychologically and to ensure that there is a good interactive relationship between group members, with all group members willing to work together for the group. The goal is to work hard to achieve the desired learning outcomes, so how to organize groups is a major issue in cooperative learning. For middle-school children, the distribution method normally used is to divide up classes, so groups will be uneven, with large differences. In this situation, cooperative learning usually involves heterogeneous grouping, so that students with different characteristics are allocated to each group. This can serve to even out individual shortcomings, so that each group will have its own merits, while also reducing the adverse effects caused by individual differences. As “free” grouping is very straightforward, there is no need to do any preparatory work, and students can stay with their friends. Therefore, the method of letting students select their own group members is frequently used on campus. In cooperative learning, the members of the group will be affected by the way the group is formed. A good grouping method can make the team work harder toward the common goal and significantly improve learning ( Gillies, 2004 ; Goodyear et al., 2014 ).