Home Blog Design How to Design a Winning Poster Presentation: Quick Guide with Examples & Templates

How to Design a Winning Poster Presentation: Quick Guide with Examples & Templates

How are research posters like High School science fair projects? Quite similar, in fact.

Both are visual representations of a research project shared with peers, colleagues and academic faculty. But there’s a big difference: it’s all in professionalism and attention to detail. You can be sure that the students that thrived in science fairs are now creating fantastic research posters, but what is that extra element most people miss when designing a poster presentation?

This guide will teach tips and tricks for creating poster presentations for conferences, symposia, and more. Learn in-depth poster structure and design techniques to help create academic posters that have a lasting impact.

Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

- What is a Research Poster?

Why are Poster Presentations important?

Overall dimensions and orientation, separation into columns and sections, scientific, academic, or something else, a handout with supplemental and contact information, cohesiveness, design and readability, storytelling.

- Font Characteristics

- Color Pairing

- Data Visualization Dimensions

- Alignment, Margins, and White Space

Scientific/Academic Conference Poster Presentation

Digital research poster presentations, slidemodel poster presentation templates, how to make a research poster presentation step-by-step, considerations for printing poster presentations, how to present a research poster presentation, final words, what is a research poster .

Research posters are visual overviews of the most relevant information extracted from a research paper or analysis. They are essential communication formats for sharing findings with peers and interested people in the field. Research posters can also effectively present material for other areas besides the sciences and STEM—for example, business and law.

You’ll be creating research posters regularly as an academic researcher, scientist, or grad student. You’ll have to present them at numerous functions and events. For example:

- Conference presentations

- Informational events

- Community centers

The research poster presentation is a comprehensive way to share data, information, and research results. Before the pandemic, the majority of research events were in person. During lockdown and beyond, virtual conferences and summits became the norm. Many researchers now create poster presentations that work in printed and digital formats.

Let’s look at why it’s crucial to spend time creating poster presentations for your research projects, research, analysis, and study papers.

Research posters represent you and your sponsor’s research

Research papers and accompanying poster presentations are potent tools for representation and communication in your field of study. Well-performing poster presentations help scientists, researchers, and analysts grow their careers through grants and sponsorships.

When presenting a poster presentation for a sponsored research project, you’re representing the company that sponsored you. Your professionalism, demeanor, and capacity for creating impactful poster presentations call attention to other interested sponsors, spreading your impact in the field.

Research posters demonstrate expertise and growth

Presenting research posters at conferences, summits, and graduate grading events shows your expertise and knowledge in your field of study. The way your poster presentation looks and delivers, plus your performance while presenting the work, is judged by your viewers regardless of whether it’s an officially judged panel.

Recurring visitors to research conferences and symposia will see you and your poster presentations evolve. Improve your impact by creating a great poster presentation every time by paying attention to detail in the poster design and in your oral presentation. Practice your public speaking skills alongside the design techniques for even more impact.

Poster presentations create and maintain collaborations

Every time you participate in a research poster conference, you create meaningful connections with people in your field, industry or community. Not only do research posters showcase information about current data in different areas, but they also bring people together with similar interests. Countless collaboration projects between different research teams started after discussing poster details during coffee breaks.

An effective research poster template deepens your peer’s understanding of a topic by highlighting research, data, and conclusions. This information can help other researchers and analysts with their work. As a research poster presenter, you’re given the opportunity for both teaching and learning while sharing ideas with peers and colleagues.

Anatomy of a Winning Poster Presentation

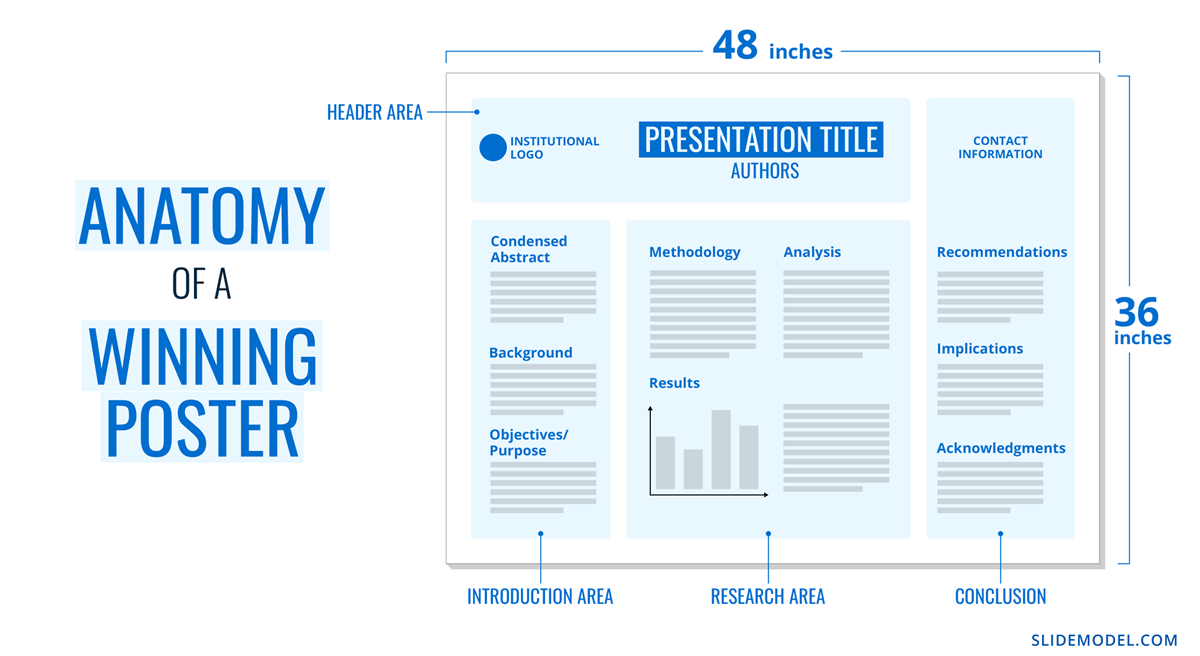

Do you want your research poster to perform well? Following the standard layout and adding a few personal touches will help attendees know how to read your poster and get the most out of your information.

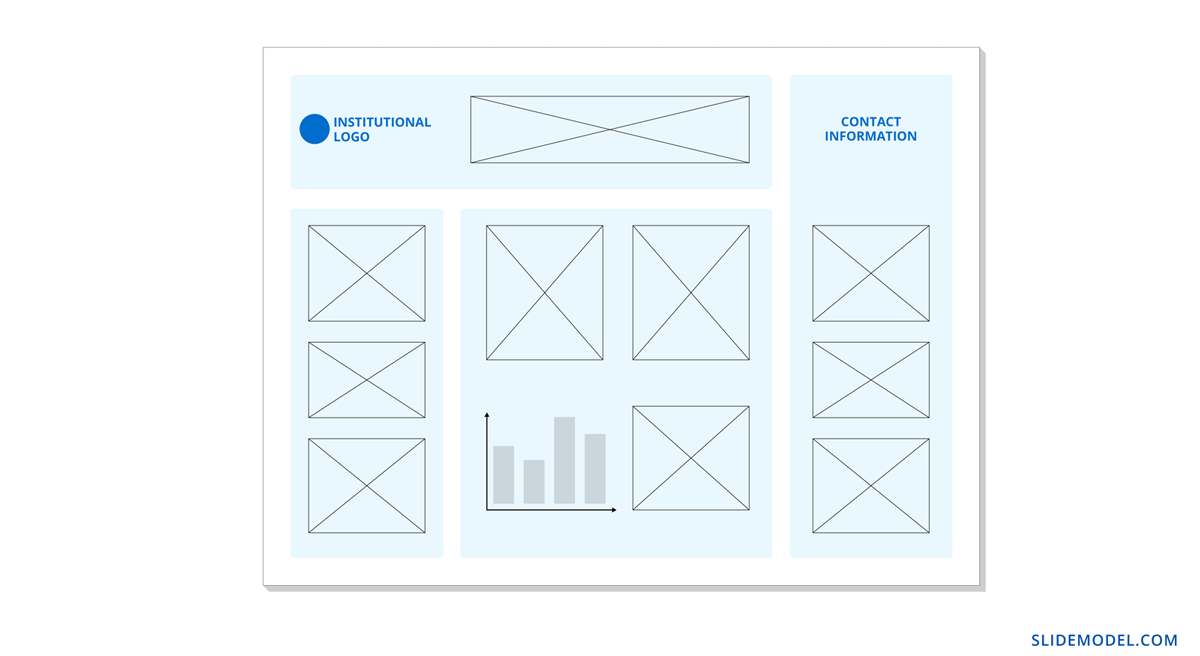

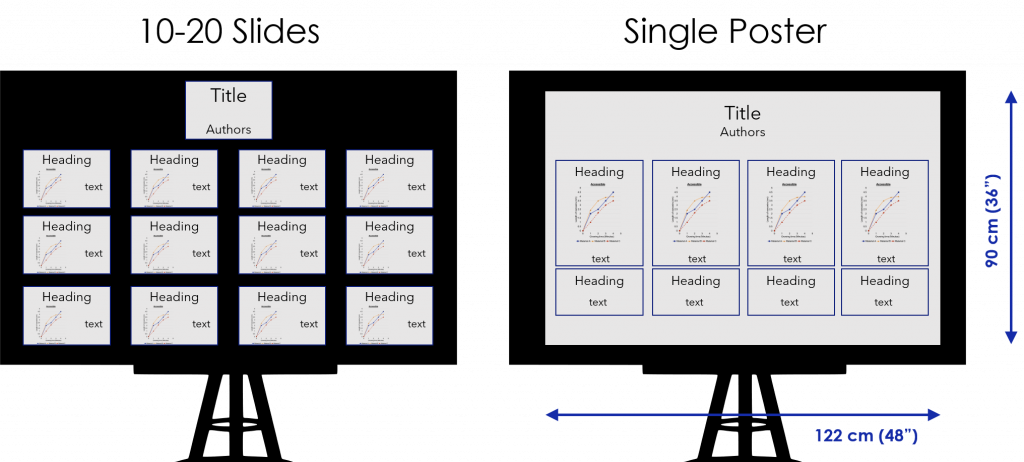

The overall size of your research poster ultimately depends on the dimensions of the provided space at the conference or research poster gallery. The poster orientation can be horizontal or vertical, with horizontal being the most common. In general, research posters measure 48 x 36 inches or are an A0 paper size.

A virtual poster can be the same proportions as the printed research poster, but you have more leeway regarding the dimensions. Virtual research posters should fit on a screen with no need to scroll, with 1080p resolution as a standard these days. A horizontal presentation size is ideal for that.

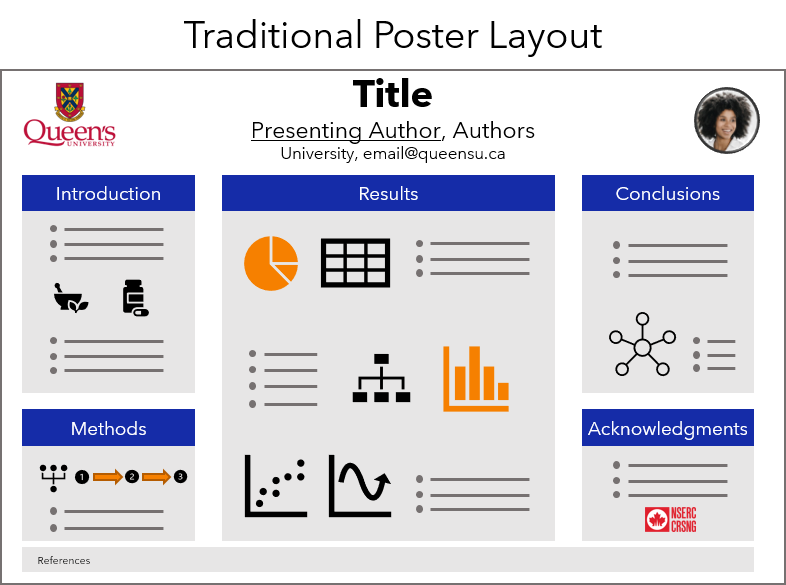

A research poster presentation has a standard layout of 2–5 columns with 2–3 sections each. Typical structures say to separate the content into four sections; 1. A horizontal header 2. Introduction column, 3. Research/Work/Data column, and 4. Conclusion column. Each unit includes topics that relate to your poster’s objective. Here’s a generalized outline for a poster presentation:

- Condensed Abstract

- Objectives/Purpose

- Methodology

- Recommendations

- Implications

- Acknowledgments

- Contact Information

The overview content you include in the units depends on your poster presentations’ theme, topic, industry, or field of research. A scientific or academic poster will include sections like hypothesis, methodology, and materials. A marketing analysis poster will include performance metrics and competitor analysis results.

There’s no way a poster can hold all the information included in your research paper or analysis report. The poster is an overview that invites the audience to want to find out more. That’s where supplement material comes in. Create a printed PDF handout or card with a QR code (created using a QR code generator ). Send the audience to the best online location for reading or downloading the complete paper.

What Makes a Poster Presentation Good and Effective?

For your poster presentation to be effective and well-received, it needs to cover all the bases and be inviting to find out more. Stick to the standard layout suggestions and give it a unique look and feel. We’ve put together some of the most critical research poster-creation tips in the list below. Your poster presentation will perform as long as you check all the boxes.

The information you choose to include in the sections of your poster presentation needs to be cohesive. Train your editing eye and do a few revisions before presenting. The best way to look at it is to think of The Big Picture. Don’t get stuck on the details; your attendees won’t always know the background behind your research topic or why it’s important.

Be cohesive in how you word the titles, the length of the sections, the highlighting of the most important data, and how your oral presentation complements the printed—or virtual—poster.

The most important characteristic of your poster presentation is its readability and clarity. You need a poster presentation with a balanced design that’s easy to read at a distance of 1.5 meters or 4 feet. The font size and spacing must be clear and neat. All the content must suggest a visual flow for the viewer to follow.

That said, you don’t need to be a designer to add something special to your poster presentation. Once you have the standard—and recognized—columns and sections, add your special touch. These can be anything from colorful boxes for the section titles to an interesting but subtle background, images that catch the eye, and charts that inspire a more extended look.

Storytelling is a presenting technique involving writing techniques to make information flow. Firstly, storytelling helps give your poster presentation a great introduction and an impactful conclusion.

Think of storytelling as the invitation to listen or read more, as the glue that connects sections, making them flow from one to another. Storytelling is using stories in the oral presentation, for example, what your lab partner said when you discovered something interesting. If it makes your audience smile and nod, you’ve hit the mark. Storytelling is like giving a research presentation a dose of your personality, and it can help turning your data into opening stories .

Design Tips For Creating an Effective Research Poster Presentation

The section above briefly mentioned how important design is to your poster presentation’s effectiveness. We’ll look deeper into what you need to know when designing a poster presentation.

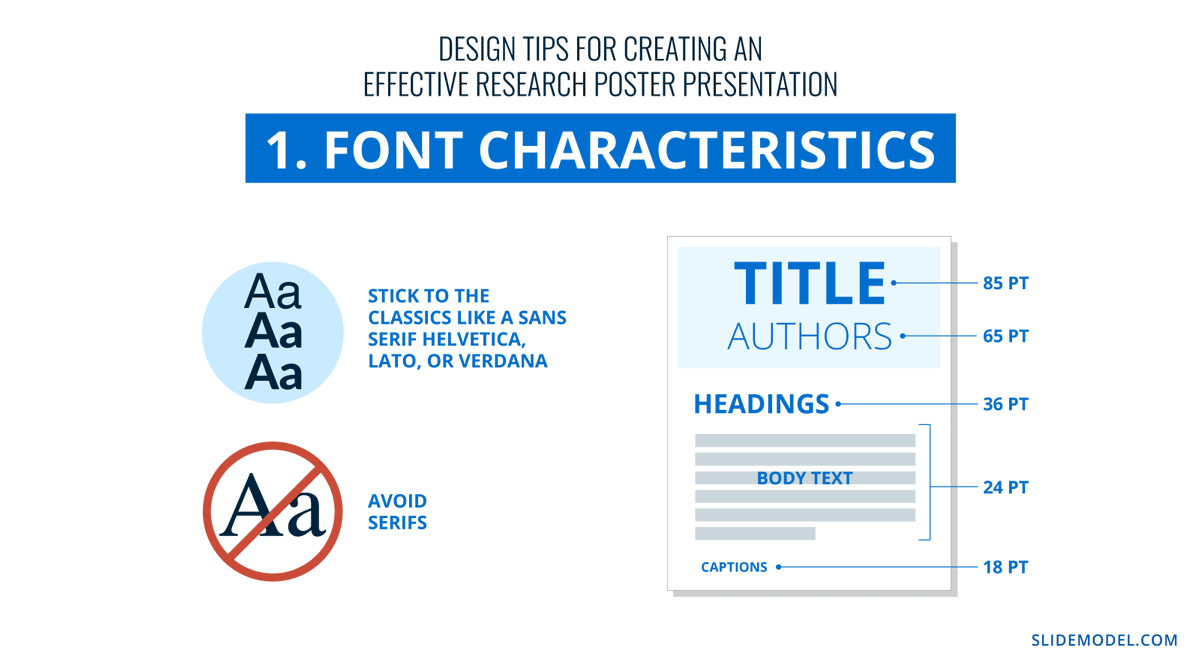

1. Font Characteristics

The typeface and size you choose are of great importance. Not only does the text need to be readable from two meters away, but it also needs to look and sit well on the poster. Stay away from calligraphic script typefaces, novelty typefaces, or typefaces with uniquely shaped letters.

Stick to the classics like a sans serif Helvetica, Lato, Open Sans, or Verdana. Avoid serif typefaces as they can be difficult to read from far away. Here are some standard text sizes to have on hand.

- Title: 85 pt

- Authors: 65 pt

- Headings: 36 pt

- Body Text: 24 pt

- Captions: 18 pt

If you feel too prone to use serif typefaces, work with a font pairing tool that helps you find a suitable solution – and intend those serif fonts for heading sections only. As a rule, never use more than 3 different typefaces in your design. To make it more dynamic, you can work with the same font using light, bold, and italic weights to put emphasis on the required areas.

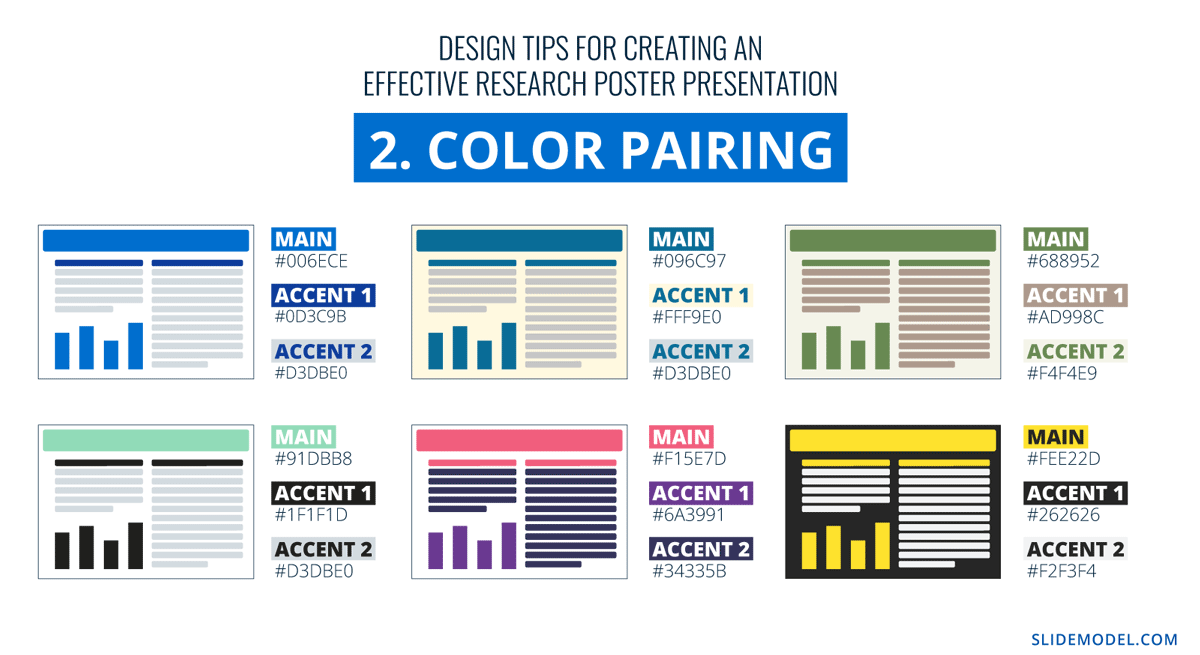

2. Color Pairing

Using colors in your poster presentation design is a great way to grab the viewer’s attention. A color’s purpose is to help the viewer follow the data flow in your presentation, not distract. Don’t let the color take more importance than the information on your poster.

Choose one main color for the title and headlines and a similar color for the data visualizations. If you want to use more than one color, don’t create too much contrast between them. Try different tonalities of the same color and keep things balanced visually. Your color palette should have at most one main color and two accent colors.

Black text over a white background is standard practice for printed poster presentations, but for virtual presentations, try a very light gray instead of white and a very dark gray instead of black. Additionally, use variations of light color backgrounds and dark color text. Make sure it’s easy to read from two meters away or on a screen, depending on the context. We recommend ditching full white or full black tone usage as it hurts eyesight in the long term due to its intense contrast difference with the light ambiance.

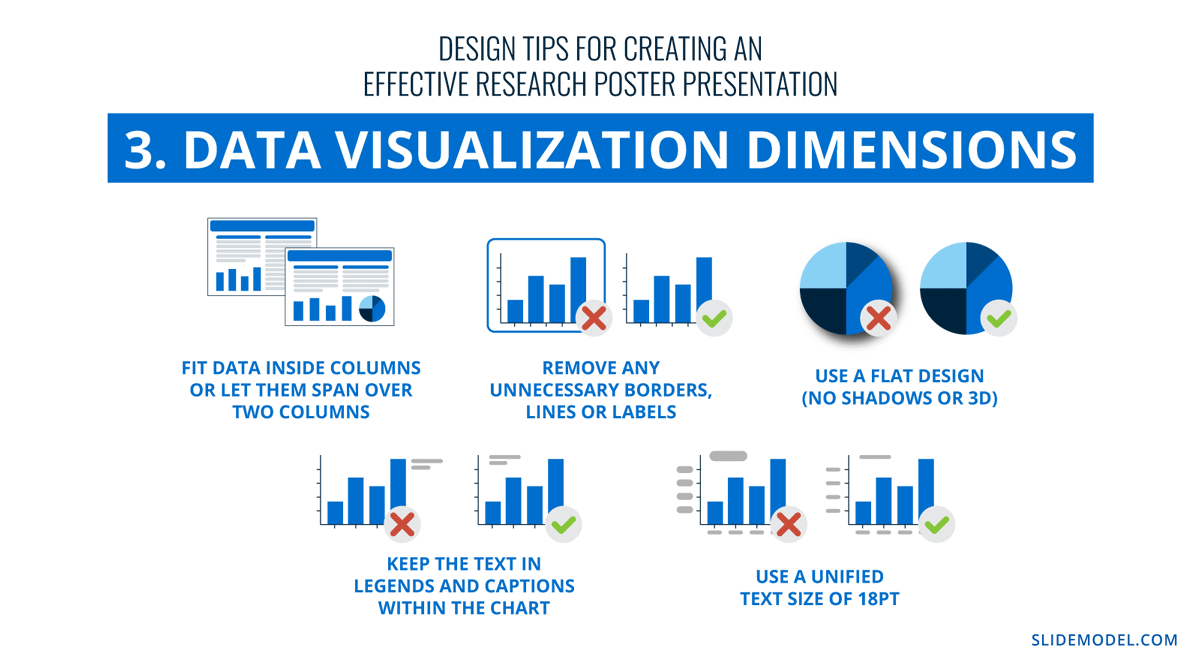

3. Data Visualization Dimensions

Just like the text, your charts, graphs, and data visualizations must be easy to read and understand. Generally, if a person is interested in your research and has already read some of the text from two meters away, they’ll come closer to look at the charts and graphs.

Fit data visualizations inside columns or let them span over two columns. Remove any unnecessary borders, lines, or labels to make them easier to read at a glance. Use a flat design without shadows or 3D characteristics. The text in legends and captions should stay within the chart size and not overflow into the margins. Use a unified text size of 18px for all your data visualizations.

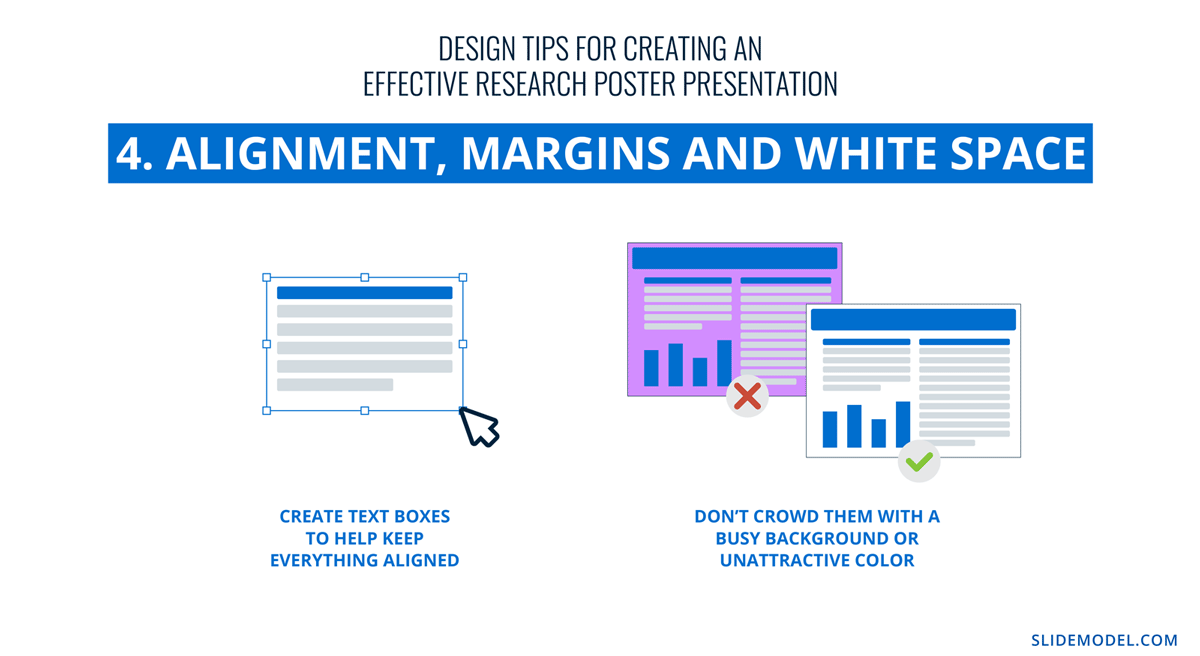

4. Alignment, Margins, and White Space

Finally, the last design tip for creating an impressive and memorable poster presentation is to be mindful of the layout’s alignment, margins, and white space. Create text boxes to help keep everything aligned. They allow you to resize, adapt, and align the content along a margin or grid.

Take advantage of the white space created by borders and margins between sections. Don’t crowd them with a busy background or unattractive color.

Calculate margins considering a print format. It is a good practice in case the poster presentation ends up becoming in physical format, as you won’t need to downscale your entire design (affecting text readability in the process) to preserve information.

There are different tools that you can use to make a poster presentation. Presenters who are familiar with Microsoft Office prefer to use PowerPoint. You can learn how to make a poster in PowerPoint here.

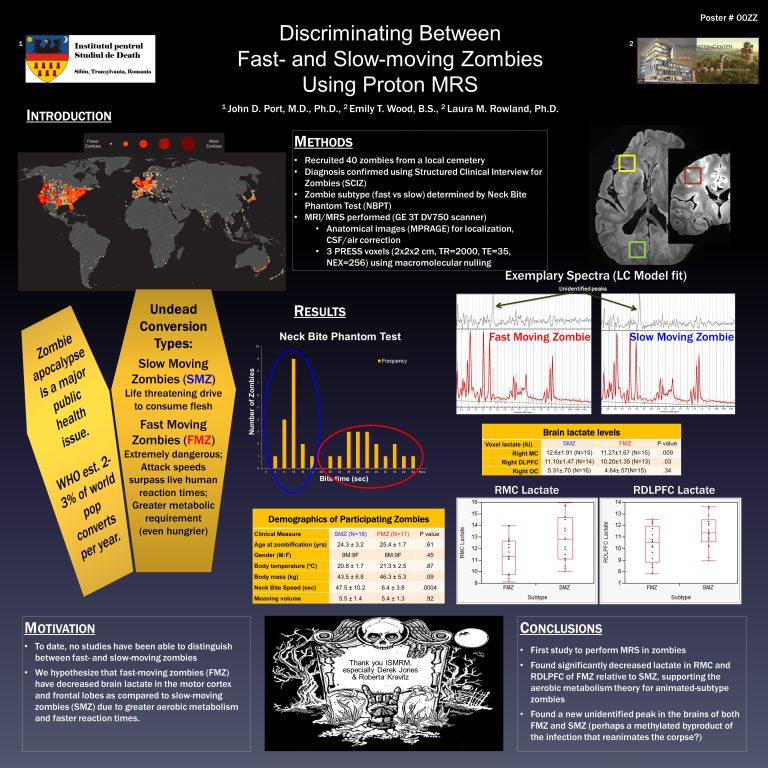

Poster Presentation Examples

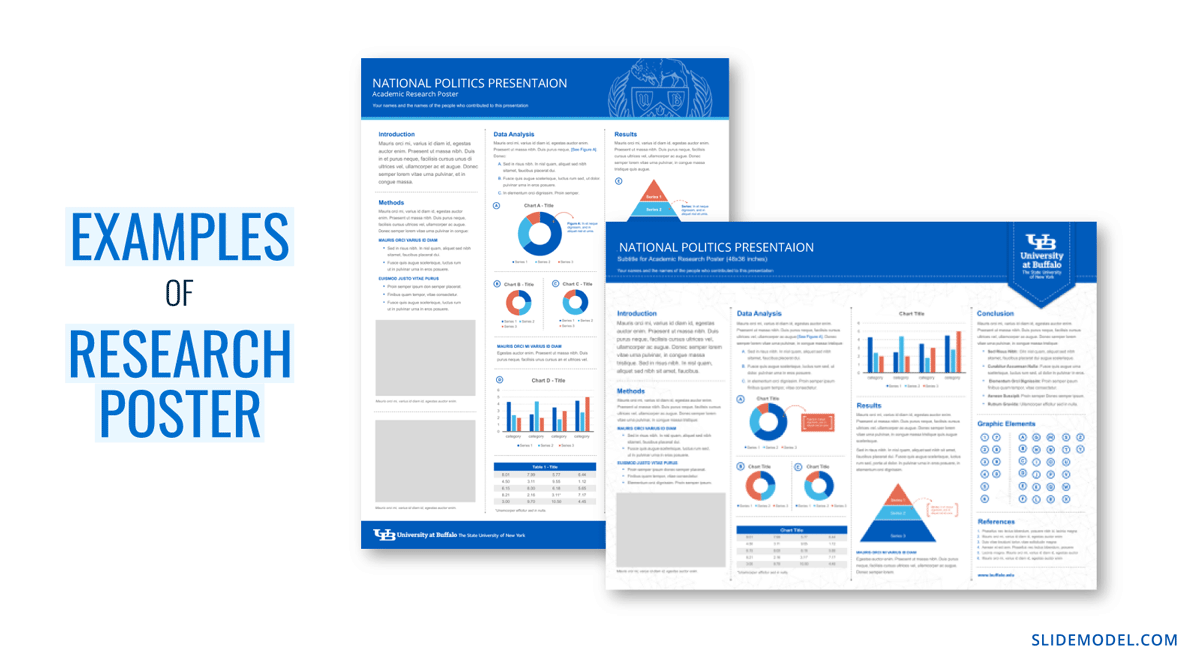

Before you start creating a poster presentation, look at some examples of real research posters. Get inspired and get creative.

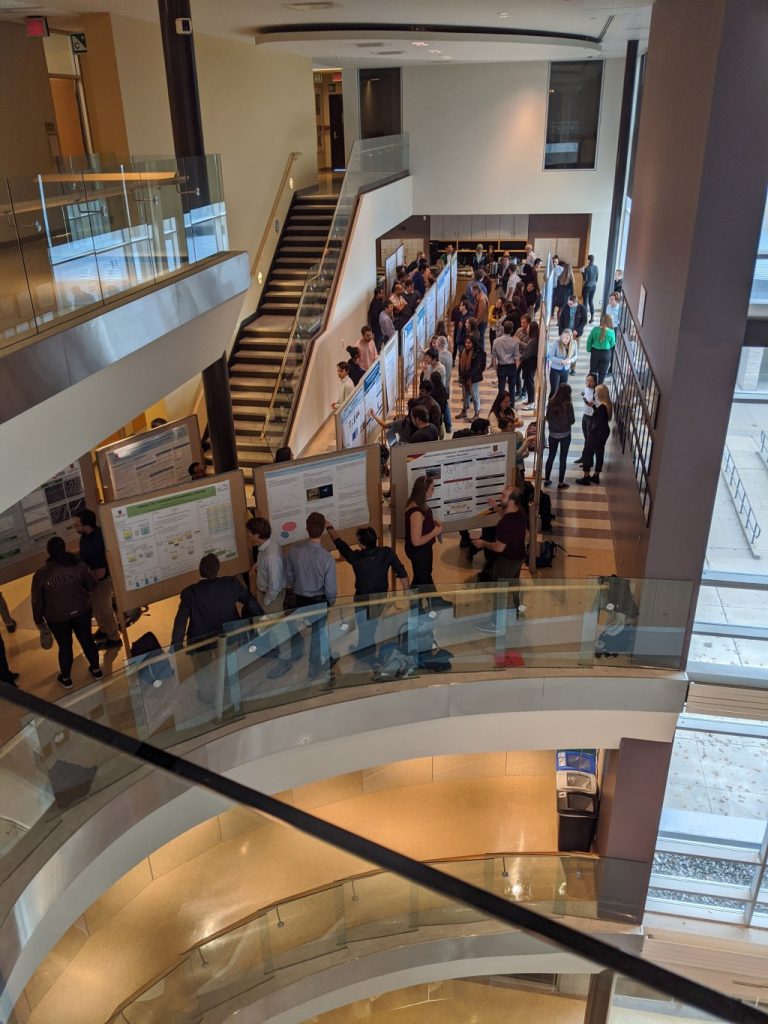

Research poster presentations printed and mounted on a board look like the one in the image below. The presenter stands to the side, ready to share the information with visitors as they walk up to the panels.

With more and more conferences staying virtual or hybrid, the digital poster presentation is here to stay. Take a look at examples from a poster session at the OHSU School of Medicine .

Use SlideModel templates to help you create a winning poster presentation with PowerPoint and Google Slides. These poster PPT templates will get you off on the right foot. Mix and match tables and data visualizations from other poster slide templates to create your ideal layout according to the standard guidelines.

If you need a quick method to create a presentation deck to talk about your research poster at conferences, check out our Slides AI presentation maker. A tool in which you add the topic, curate the outline, select a design, and let AI do the work for you.

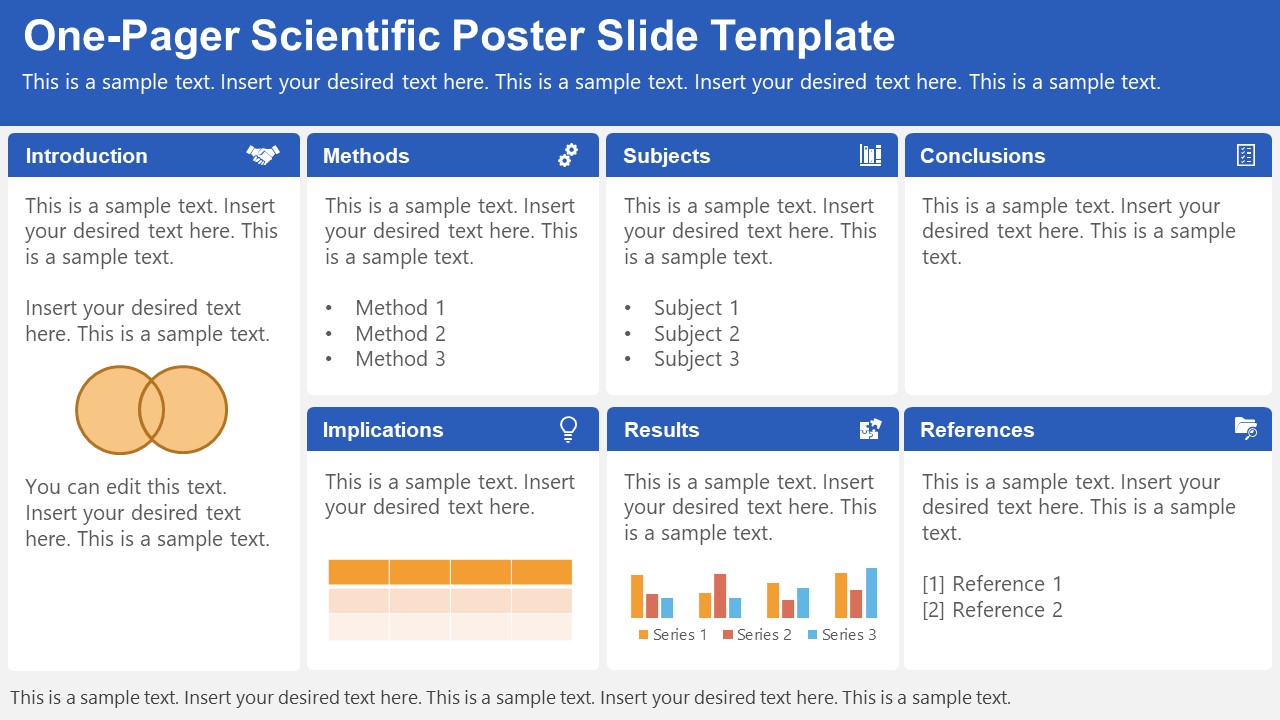

1. One-pager Scientific Poster Template for PowerPoint

A PowerPoint template tailored to make your poster presentations an easy-to-craft process. Meet our One-Pager Scientific Poster Slide Template, entirely editable to your preferences and with ample room to accommodate graphs, data charts, and much more.

Use This Template

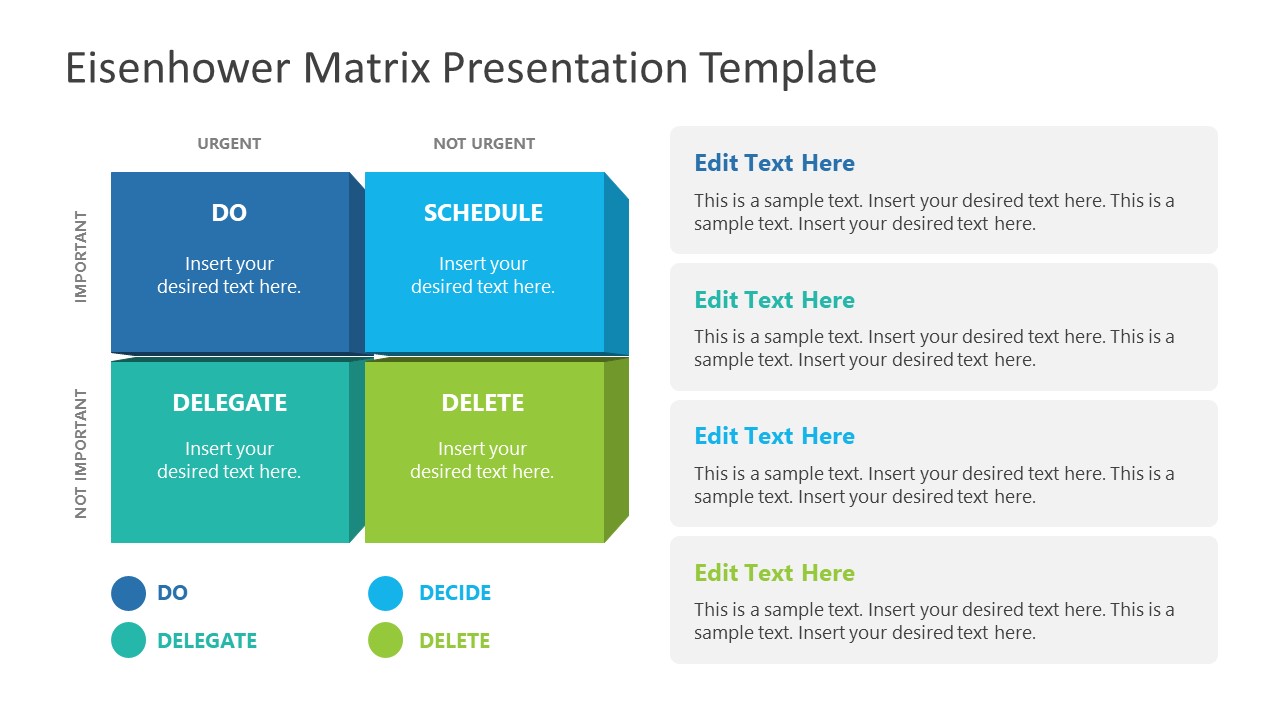

2. Eisenhower Matrix Slides Template for PowerPoint

An Eisenhower Matrix is a powerful tool to represent priorities, classifying work according to urgency and importance. Presenters can use this 2×2 matrix in poster presentations to expose the effort required for the research process, as it also helps to communicate strategy planning.

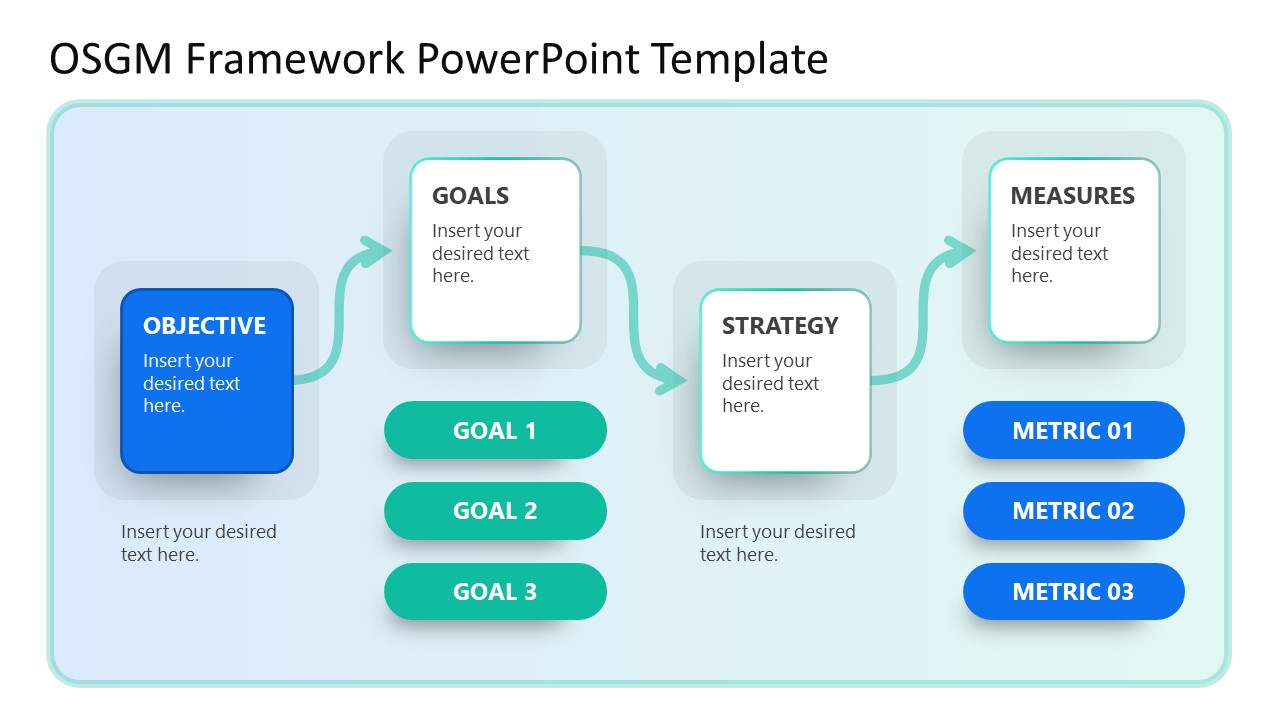

3. OSMG Framework PowerPoint Template

Finally, we recommend presenters check our OSMG Framework PowerPoint template, as it is an ideal tool for representing a business plan: its goals, strategies, and measures for success. Expose complex processes in a simplified manner by adding this template to your poster presentation.

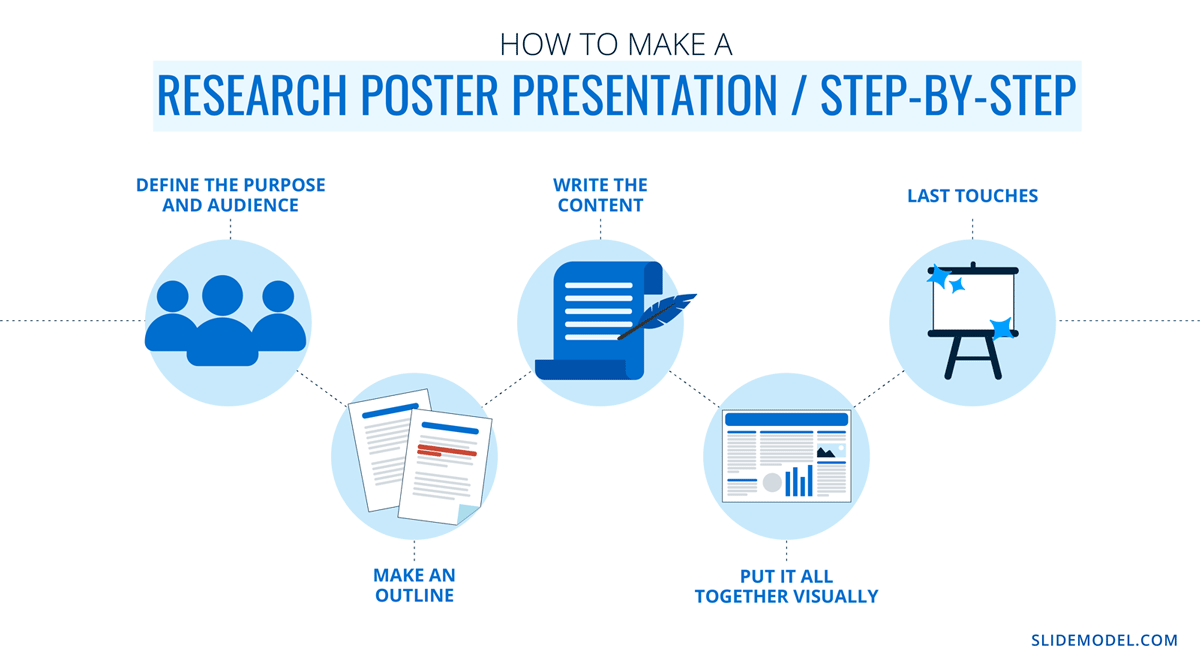

Remember these three words when making your research poster presentation: develop, design, and present. These are the three main actions toward a successful poster presentation.

The section below will take you on a step-by-step journey to create your next poster presentation.

Step 1: Define the purpose and audience of your poster presentation

Before making a poster presentation design, you’ll need to plan first. Here are some questions to answer at this point:

- Are they in your field?

- Do they know about your research topic?

- What can they get from your research?

- Will you print it?

- Is it for a virtual conference?

Step 2: Make an outline

With a clear purpose and strategy, it’s time to collect the most important information from your research paper, analysis, or documentation. Make a content dump and then select the most interesting information. Use the content to draft an outline.

Outlines help formulate the overall structure better than going straight into designing the poster. Mimic the standard poster structure in your outline using section headlines as separators. Go further and separate the content into the columns they’ll be placed in.

Step 3: Write the content

Write or rewrite the content for the sections in your poster presentation. Use the text in your research paper as a base, but summarize it to be more succinct in what you share.

Don’t forget to write a catchy title that presents the problem and your findings in a clear way. Likewise, craft the headlines for the sections in a similar tone as the title, creating consistency in the message. Include subtle transitions between sections to help follow the flow of information in order.

Avoid copying/pasting entire sections of the research paper on which the poster is based. Opt for the storytelling approach, so the delivered message results are interesting for your audience.

Step 4: Put it all together visually

This entire guide on how to design a research poster presentation is the perfect resource to help you with this step. Follow all the tips and guidelines and have an unforgettable poster presentation.

Moving on, here’s how to design a research poster presentation with PowerPoint Templates . Open a new project and size it to the standard 48 x 36 inches. Using the outline, map out the sections on the empty canvas. Add a text box for each title, headline, and body text. Piece by piece, add the content into their corresponding text box.

Transform the text information visually, make bullet points, and place the content in tables and timelines. Make your text visual to avoid chunky text blocks that no one will have time to read. Make sure all text sizes are coherent for all headings, body texts, image captions, etc. Double-check for spacing and text box formatting.

Next, add or create data visualizations, images, or diagrams. Align everything into columns and sections, making sure there’s no overflow. Add captions and legends to the visualizations, and check the color contrast with colleagues and friends. Ask for feedback and progress to the last step.

Step 5: Last touches

Time to check the final touches on your poster presentation design. Here’s a checklist to help finalize your research poster before sending it to printers or the virtual summit rep.

- Check the resolution of all visual elements in your poster design. Zoom to 100 or 200% to see if the images pixelate. Avoid this problem by using vector design elements and high-resolution images.

- Ensure that charts and graphs are easy to read and don’t look crowded.

- Analyze the visual hierarchy. Is there a visual flow through the title, introduction, data, and conclusion?

- Take a step back and check if it’s legible from a distance. Is there enough white space for the content to breathe?

- Does the design look inviting and interesting?

An often neglected topic arises when we need to print our designs for any exhibition purpose. Since A0 is a hard-to-manage format for most printers, these poster presentations result in heftier charges for the user. Instead, you can opt to work your design in two A1 sheets, which also becomes more manageable for transportation. Create seamless borders for the section on which the poster sheets should meet, or work with a white background.

Paper weight options should be over 200 gsm to avoid unwanted damage during the printing process due to heavy ink usage. If possible, laminate your print or stick it to photographic paper – this shall protect your work from spills.

Finally, always run a test print. Gray tints may not be printed as clearly as you see them on screen (this is due to the RGB to CMYK conversion process). Other differences can be appreciated when working with ink jet plotters vs. laser printers. Give yourself enough room to maneuver last-minute design changes.

Presenting a research poster is a big step in the poster presentation cycle. Your poster presentation might or might not be judged by faculty or peers. But knowing what judges look for will help you prepare for the design and oral presentation, regardless of whether you receive a grade for your work or if it’s business related. Likewise, the same principles apply when presenting at an in-person or virtual summit.

The opening statement

Part of presenting a research poster is welcoming the viewer to your small personal area in the sea of poster presentations. You’ll need an opening statement to pitch your research poster and get the viewers’ attention.

Draft a 2 to 3-sentence pitch that covers the most important points:

- What the research is

- Why was it conducted

- What the results say

From that opening statement, you’re ready to continue with the oral presentation for the benefit of your attendees.

The oral presentation

During the oral presentation, share the information on the poster while conversing with the interested public. Practice many times before the event. Structure the oral presentation as conversation points, and use the poster’s visual flow as support. Make eye contact with your audience as you speak, but don’t make them uncomfortable.

Pro Tip: In a conference or summit, if people show up to your poster area after you’ve started presenting it to another group, finish and then address the new visitors.

QA Sessions

When you’ve finished the oral presentation, offer the audience a chance to ask questions. You can tell them before starting the presentation that you’ll be holding a QA session at the end. Doing so will prevent interruptions as you’re speaking.

If presenting to one or two people, be flexible and answer questions as you review all the sections on your poster.

Supplemental Material

If your audience is interested in learning more, you can offer another content type, further imprinting the information in their minds. Some ideas include; printed copies of your research paper, links to a website, a digital experience of your poster, a thesis PDF, or data spreadsheets.

Your audience will want to contact you for further conversations; include contact details in your supplemental material. If you don’t offer anything else, at least have business cards.

Even though conferences have changed, the research poster’s importance hasn’t diminished. Now, instead of simply creating a printed poster presentation, you can also make it for digital platforms. The final output will depend on the conference and its requirements.

This guide covered all the essential information you need to know for creating impactful poster presentations, from design, structure and layout tips to oral presentation techniques to engage your audience better .

Before your next poster session, bookmark and review this guide to help you design a winning poster presentation every time.

Like this article? Please share

Cool Presentation Ideas, Design, Design Inspiration Filed under Design

Related Articles

Filed under Design • January 11th, 2024

How to Use Figma for Presentations

The powerful UI/UX prototyping software can also help us to craft high-end presentation slides. Learn how to use Figma as a presentation software here!

Filed under Design • December 28th, 2023

Multimedia Presentation: Insights & Techniques to Maximize Engagement

Harnessing the power of multimedia presentation is vital for speakers nowadays. Join us to discover how you can utilize these strategies in your work.

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • December 15th, 2023

How to Delete a Text Box in Google Slides

Discover how to delete a text box in Google Slides in just a couple of clicks. Step-by-step guide with images.

Leave a Reply

Customize Your Path

Filters Applied

Customize Your Experience.

Utilize the "Customize Your Path" feature to refine the information displayed in myRESEARCHpath based on your role, project inclusions, sponsor or funding, and management center.

Poster and oral presentations

Need assistance with poster presentations?

Get help with poster presentations.

Contact the Research Navigators:

- Email: [email protected]

Poster and oral presentations are typically delivered to academic colleagues at conferences or congresses. Here are some best practices and resources to help develop the content and visuals for a high-impact poster, and plan and practice memorable oral presentations.

The "Related Resources" on this page can be used to tap into Duke’s hub of templates, guides, and services to support researchers developing their presentations.

The Duke Medical Center Library has tips for things to keep in mind before working through the development of a poster presentation, and the Duke University Libraries' Center for Data and Visualization Sciences recorded a talk on preparing effective academic posters .

- Just like with any other publication, the specifications from the conference should be read and understood – there are often size limits or font requirements to keep in mind.

- A good title is critical for posters since presenters get just a few seconds to attract conference goers who are passing by. Make sure the title briefly and memorably portrays the most interesting or central finding of the work.

- Energy should be focused on a solid abstract, as the poster is simply a blown-up visualization of that summary.

- Less is more in poster design. Rather than shrinking fonts to fit the commentary, the commentary should be shrunk to fit the space on the poster, while retaining a readable font and plenty of white space.

The Thompson Writing Program has great general guidance on oral presentations, summarized throughout this page. There are several training opportunities listed in this page's "Related Resources" that can help researchers at all stages to hone their presentation skills.

- Preparing for an oral presentation will take the majority of a researcher's time. The goal of the talk should be fully understood as typically no more than 3-5 key points will be covered in a presentation; the audience and the time allotted should be carefully considered.

- Consideration of “guideposts” for the audience should be given. It is especially important in oral deliveries that information is organized in to meaningful blocks for the audience. Transitions should be emphasized during the presentation.

- Rather than creating a word-for-word speech, researchers should create a plan for each section, idea or point. By reading written points, delivery can be kept fresh.

- To engage audiences, it is a good idea to make strongest points first, and in a memorable way. While background and introduction sections are common in academic presentations, they are often already known to the audience.

The Duke Medical Center Library has tutorials, best practices for general design, and strategies for a high-impact poster presentations. Bass Connections also provides guidance on poster design.

Some important things to keep in mind are:

- Keeping posters simple and focusing on two things: Strong visualizations and small blocks of supporting text. Remember the audience; they will be standing a few feet away. Make sure the content is visible from afar.

- Follow brand guidelines from Duke or Duke School of Medicine . When representing Duke at a conference, it is best practice to align the presentation with institutional standards, including appropriate logos and color schemes.

- Avoid violating copyright protections. Include only images created specifically for this purpose, or use stock photography provided by Duke or other vendors.

- Visualizing data tells the story. The Center for Data and Visualization Sciences has workshops, consultations and other resources to ensure that graphical representations of data are effective.

- Poster presentations can be designed using a variety of software (PowerPoint, Illustrator, Keynote, Inkscape), and templates. When choosing software or templates, consideration should be given to accessibility and understanding by everyone involved in creating the presentation.

- Contact information, citations and acknowledgements: On posters, key articles may be noted or images needing references included. For oral and poster presentations, key contributors should be recognized. Funding sources should also be mentioned on posters and in oral presentations.

- A link or QR code should be included for supplemental materials, citations, movies, etc.

- Before a poster is printed, someone with fresh eyes should review it! Reprinting posters is costly and can take time. There are many options for printing, some on paper and some on fabric, with production times varying. The Medical Center Library has some local options to suggest.

- Practicing in a space that is similar to the actual presentation is a good idea, and doing so within the allotted time. Finishing early to allow good Q&A is also a good idea.

- Family, trusted friends, or colleagues can be great test audiences, and can provide valuable feedback.

- Preparation and practice should be started early and repeated often.

- If it is an important address, researchers may want to videotape a rehearsal run to review and improve performance.

- If a presentation is being digitized, release or permission forms may be needed. Duke has resources available via Scholarworks.

- Once a poster session or oral presentation has been completed, researchers should be sure to add it to their CV or biosketch.

University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Research Posters : Oral Presentations

- Elements of a poster

- Step by step

- Visualizations & images

- Illinois logo

- Archiving - Grad Students

- More Resources

- Oral Presentations

- 2024 Undergraduate Research Symposium This link opens in a new window

TIPS FOR ORAL PRESENTATIONS

- How to give a great oral presentation

- Ten Simple Rules for Making Good Oral Presentations

- Top 15 tips to give a good oral presentation

- Designing PowerPoint Slides for a Scientific Presentation

The Speaking Center

The Library offers speaking consultation and practice at the The Speaking Center . Schedule an appointment with us and practice giving your presentation.

CONSIDERING YOUR CONTENT

I have been accepted to present an oral presentation at the Symposium; how do I upload my talk? All oral presentation rooms are equipped with PC laptops (no Apple Mac's) so be sure the format of your presentation is compatible with PCs. In general, we recommend that students save their presentations in two formats: the first being a .PPT (Microsoft PowerPoint) file, and the back-up being a .PDF (Adobe Acrobat) file. Please bring these files on a portable drive (flash drive, etc.) to your oral presentation panel and be sure to show up early to allow enough time to download it to the computer prior to the start of the session.

- Think of, or research, an attention grabber: a story, fact or statistic, or other interesting piece of information that will help draw in the audience right away and frame the talk in a minute or less.

- Focus only on the 3 most important points. Introduce them at the beginning, and repeat them at the very end.

- Have 2-3 specifics/particular points that fall within each of the three categories, and, if possible, also have a brief story or example to illustrate each main point.

- Write out transitions between major points and examples (and practice them) so your speech will flow better. Example: “So far we’ve discussed [x], but on the other end of the spectrum is this other important aspect, [y].”

- Be gender neutral. Even though it may not technically be grammatically correct, today it is acceptable in formal presentations in most contexts to use “they” and “them” instead of she/he, him/her.

- Try, if you can, to incorporate a bit of tasteful humor. It shouldn’t be forced; it needs to fit in with the rest of the speech and feel natural to be funny. Don’t be afraid to improvise during your talk, if you can do so comfortably.

- Have someone else read your speech, or alternately, practice your presentation in front of them – so they can critique the content and delivery.

PRESENTATION DELIVERY

1. Practice and prepare. Practice in front of a mirror. Take a video or audio recording of yourself. Rehearse the presentation in your head when you are unable to rehearse it aloud. With the right amount of practice and preparation, the words will flow more easily on presentation day. Don’t strive for absolute perfection, though: too much rehearsal may make you come across stiff and stifled, not natural.

2. When practicing, pay attention to your voice inflections, including which words and syllables you will emphasize. Be deliberate. Your voice inflections and emphases will affect your audience members’ interpretation, comprehension, and retention of the material.

3. Know how you are going to stand, gesture, and move your body. Practice walking around a bit – moving toward your audience and back towards the screen/lectern, for example. Try to face your audience at all times, and look around the room at individual audience members as much as possible. Make the audience feel like you are directly addressing them. While some movement is fine and can complement your style, be careful not to walk or pace too much; this can be distracting.

4. Wear comfortable professional clothing and comfortable shoes. You will not want to be distracted because you are uncomfortable.

5. Be early. If you are running late, you will be more nervous and have less time to prepare yourself mentally.

6. On the day of the talk, take 10-15 minutes before your presentation to relax, do some deep breathing, and keep your mind off of the presentation for a bit. You want to be relaxed during your presentation.

7. Be confident! Be passionate! Be energetic! You’ve got this. Don’t expect to be perfect, but if you have practiced and you are confident, it will show and make for a great presentation.

- << Previous: More Resources

- Next: 2024 Undergraduate Research Symposium >>

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 12:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/poster

Preparing oral and poster presentations for conferences

As a PhD student, attending conferences is an exciting part of academic life. Conferences are a chance to share your research findings, learn novel ideas or techniques and travel, whether that is locally, further afield or even internationally. A crucial aspect to conference attending is conveying your research to the wider scientific community, through either a poster or oral presentation.

Preparing your research to present at a conference is a balance. You need to include the same details as you would put in a paper or report, but make it concise to fit reasonably in a poster format, or within a specific talk length, such as 10 minutes. When writing a talk or poster for a specific conference, investigating the style and content of previous years abstracts may help to peg yours at a suitable level. Before you start, check the conference guidelines on oral presentation outlines, poster size, and orientation. Although most conferences allow A0 portrait posters, some are different and it’s advisable to check this before writing.

Preparing your poster

Generally, posters follow a bullet point style divided into four main sections:

- Introduction or Background

- Discussion or Conclusions.

However, there are some other areas of the poster that need attention too.

Firstly, a snappy title is a must. The title must cover the basic outline of the study, yet be intriguing, making the viewer want to read on. The title must be considered during abstract preparation, as whatever you name your abstract will be your poster title. Author names and affiliations sit below the title; the order of this can be important but must be agreed by your research group before poster publication.

The introduction covers the background details of the research involved, using current literature and references. The aims and objectives of the research must be in the introduction, and generally sits well at the end just before the method section to give a sense of flow.

Methods covers obviously what you did to achieve your results. It’s good to be aware of any ethical approval gained for the study, and noting participant numbers, genders and ages, statistical methods used and any chemical in their full unabbreviated names initially, with subsequent references to the ingredients by the standard abbreviations. If the method is tricky to explain, a diagram or photo may help to illustrate, and it is not necessary to repeat the methods in words.

The results section needs to cover all relevant findings. Tables or figures can really help show data, so be imaginative! You’ll need to include statistical p-values to show significances. Finally, the discussion or conclusion section highlights the key findings from your results in punchy language as a ‘take home message’. These need to be clear and concise, covering the exact findings and if possible the relevance of findings to the study and scientific community as a whole.

Oral presentations

For oral presentations the same headings should be followed, with clear simple slides. Keep the number of slides to a minimum to keep the length of the talk on track. A good guideline is around one slide per minute. Set the scene with a clear introduction to the work, indicating the relevance of the study to the general scientific community. Highlight the study aims and objectives, and unlike a poster, you may want to include a hypothesis for further clarity. Diagrams may also help to describe methodology, and helps to keep audience attention as they must listen to you fully to understand the technique.

Results can also be shown on graphs and figures; be careful with tables, as these can appear daunting to the viewer, unless you clearly highlight the numbers or significances of importance to your work. Throughout the results section explain what each experiment or figure means, what is the finding? This will help you lead directly into the conclusions, and you can repeat the key findings already covered in the results, and give a clear take home message to your audience.

And finally...

Whether you’re giving a poster or a talk at a conference, be confident. Who knows your work better than you? This will help you tackle any questions and comments posed, and give you a chance to meet fellow researchers and possible future collaborators. Project your voice, face your audience and above all enjoy yourself!

Dr Caroline Withers

Poster Presentations

Poster presentations (pdf), considering the audience.

As with any presentation, you should consider who is likely to be listening. In some cases, your audience is going to be people who know a fair bit about your topic or discipline. In other cases, such as a poster session for a family weekend, you are likely to get some people who know the topic, but also many more people who are just curious about the research that is going on. You should plan to adapt based on the person with whom you are interacting. Ask yourself: what does this person likely know and what will they want to know?

Preparing a Pitch

You should plan for having a short (about 2 minutes) summary overview of the project that can give a listener a taste of what you did. You can use that time to answer three big questions:

- What is the topic?

- What did you find? Or What are the results?

- Why is this important?

People will ask follow-up questions if they are interested in learning more or if they are confused about something you said. Think of this pitch as an appetizer: you want to whet someone’s appetite to learn more about your topic, but that small bite may be sufficient for some people.

When thinking about the pitch, keep in mind that you do not need to verbally address every component of the poster in your first remarks. You should, however, be prepared to talk about each component if asked. You should never read directly from the poster to the audience!

Posters with a Partner

If you worked on your project with another person, you should both be prepared to give the basic pitch. You may have parts of the project that each of you is more comfortable talking about in detail, but each of you should know the fundamentals in case you are asked. Then, you can pass off a question to the other person if necessary.

Preparing for Questions

You should anticipate questions from the people who view your poster. One part of your preparation can be brainstorming the likely questions and then practicing answering those questions. If you are presenting your poster at a professional meeting with other people from the discipline, you can expect more technical or content questions than if you are presenting to a more general audience. Some likely general questions you may get are:

- What made you interested in this topic?

- Why was this approach/tool/theory the most appropriate for your project?

- Where do you go from here with this research?

- What was the most interesting/surprising/challenging part of this project?

- How does this project relate to other work you are doing?

Regardless of the question, it’s ok to take a breath and focus before you start to answer. Your response should be focused and succinct as well as appropriate for the audience. If you aren’t sure what someone is asking, ask for clarification!

Ideally, the poster session will give you an opportunity to engage in a dialogue about your work. In fact, that’s one of the main draws of posters as a way to disseminate research findings.

Interacting with Your Poster

You and your poster are a team, working together to present your ideas. Once your poster is mounted, you should position yourself so that you are close to your poster but not blocking it from passersby, especially the title. Additionally:

- You should feel free to move as necessary to show different parts of the poster.

- Gesture to the relevant parts of the poster. You should use your whole hand to point toward something rather than just pointing a finger. Graphs and other data are excellent parts of a poster for gesturing. Avoid turning your back on your audience to gesture. Use the arm closest to the poster to gesture so you are not gesturing across your body or turning.

- Avoid standing with your arms crossed or otherwise looking defensive both while talking and while waiting for an audience. Closed off body language makes you appear less welcoming for someone to approach.

- Don’t forget to smile. Even if you are feeling nervous, you can “fake it ‘til you make it” by adopting a smile and acting confident.

Office / Department Name

Oral Communication Center

Contact Name

Amy Gaffney

Oral Communication Center Director

Help us provide an accessible education, offer innovative resources and programs, and foster intellectual exploration.

Site Search

Posters & Oral Presentations

Good scientific research involves a sound methodology and a novel idea that can be tested simply and repeatedly to give valid, trustworthy results. However, even the most clinically significant research is useless if it is not communicated successfully. Scientific ideas are novel, sometimes simple in theory, but most always complex in technique. These attributes of research make it necessary to use all available means of presentation. The most common media for scientists to communicate with the general public is primary journal articles. However, posters and oral presentations are also affective because they allow scientists to be in direct contact with their audience. This provides both parties an opportunity to ask pertinent questions to add clarity to the work being presented.

A poster is an exciting way for scientists to present their research. It, just as a primary research article, includes all aspects of the scientific method. A title that is brief, but specific, an abstract, an introduction, material and methods, results, and a conclusion are some headings that can appear on a poster. Also, references and acknowledgments are sometimes are included. A poster is different from a written manuscript or an oral presentation because it is mostly graphical. As such, it is important to design a poster that is visually pleasing by focusing on charts, graphs, and pictures and minimizing lengthy introductions and discussions. Highlighting all significant information with the use of bullets is essential because if further explanation is needed the audience will simply ask for it.

Oral presentations are yet another avenue for scientists to share their findings with the world. Although it can be challenging to present years of works within fifteen minutes, oral presentations can be a rewarding experience because you are the only one front of an audience whose attention you know have. Of course this emphasizes the need to speak clearly and concisely with choice words that engross the audience. Again, just as with written manuscript and posters the format of oral presentations can also vary, but essentially it must include logical, easy-to-understand events that are presented in a matter with respect to the scientific method.

Electronic Resources

Poster Presentation http://www.ncsu.edu/project/posters

This is an excellent site that covers all aspects of a poster presentation from creating a poster to presenting one. It also provides several examples with critiques for each sample. Lastly, it has a quick reference page with helpful tips for delivering a successful poster presentation.

Oral Presentation http://www.kumc.edu/SAH/OTEd/jradel/Preparing_talks/103.html

This site is cited by the NIH and is quite useful when designing an oral presentation. It addresses all aspects of a scientific talk from planning and preparing to practicing and presenting. It is brief and easy to follow with helpful tips on how to prepare for the question/answer session.

Document Resources

Scientific Poster: Tips, Significance, Design, Templates and Presentation

This document provides tips and temples for designing a poster presentation. It also discusses the significance of a poster presentation and includes a section that gives advice on how to present successfully.

Oral Presentations: Tips, Significance, Design, Guidelines & Presentation

This document provides tips and guidelines for designing an oral presentation. It also discusses the significance of an oral presentation and includes a section that gives advice on how to present successfully.

- Interlibrary Loan and Scan & Deliver

- Course Reserves

- Purchase Request

- Collection Development & Maintenance

- Current Negotiations

- Ask a Librarian

- Instructor Support

- Library How-To

- Research Guides

- Research Support

- Study Rooms

- Research Rooms

- Partner Spaces

- Loanable Equipment

- Print, Scan, Copy

- 3D Printers

- Poster Printing

- OSULP Leadership

- Strategic Plan

Research Posters and Presentations

- Poster Sections

- Day of Presentation

Science Librarian

1. Think of, or research, an attention grabber: a story, fact or statistic, or other interesting piece of information that will help draw in the audience right away and frame the talk in a minute or less.

2. Focus only on the 3 most important points. Introduce them at the beginning, and repeat them at the very end.

3. Have 2-3 specifics/particular points that fall within each of the three categories, and, if possible, also have a brief story or example to illustrate each main point.

4. Write out transitions between major points and examples (and practice them) so your speech will flow better. Example: “So far we’ve discussed [x], but on the other end of the spectrum is this other important aspect, [y].”

5. Be gender neutral. Even though it may not technically be grammatically correct, today it is acceptable in formal presentations in most contexts to use “they” and “them” instead of she/he, him/her.

6. Try, if you can, to incorporate a bit of tasteful humor. It shouldn’t be forced; it needs to fit in with the rest of the speech and feel natural to be funny. Don’t be afraid to improvise during your talk, if you can do so comfortably.

7. Have someone else read your speech, or alternately, practice your presentation in front of them – so they can critique the content and delivery.

1. Practice and prepare. Practice in front of a mirror. Take a video or audio recording of yourself. Rehearse the presentation in your head when you are unable to rehearse it aloud. With the right amount of practice and preparation, the words will flow more easily on presentation day. Don’t strive for absolute perfection, though: too much rehearsal may make you come across stiff and stifled, not natural.

2. When practicing, pay attention to your voice inflections, including which words and syllables you will emphasize. Be deliberate. Your voice inflections and emphases will affect your audience members’ interpretation, comprehension, and retention of the material.

3. Know how you are going to stand, gesture, and move your body. Practice walking around a bit – moving toward your audience and back towards the screen/lectern, for example. Try to face your audience at all times, and look around the room at individual audience members as much as possible. Make the audience feel like you are directly addressing them. While some movement is fine and can complement your style, be careful not to walk or pace too much; this can be distracting.

4. Wear comfortable professional clothing and comfortable shoes. You will not want to be distracted because you are uncomfortable.

5. Be early. If you are running late, you will be more nervous and have less time to prepare yourself mentally.

6. On the day of the talk, take 10-15 minutes before your presentation to relax, do some deep breathing, and keep your mind off of the presentation for a bit. You want to be relaxed during your presentation.

7. Be confident! Be passionate! Be energetic! You’ve got this. Don’t expect to be perfect, but if you have practiced and you are confident, it will show and make for a great presentation.

- << Previous: Design

- Next: Day of Presentation >>

- Last Updated: Oct 19, 2022 1:34 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.oregonstate.edu/researchposters

Contact Info

121 The Valley Library Corvallis OR 97331–4501

Phone: 541-737-3331

Services for Persons with Disabilities

In the Valley Library

- Oregon State University Press

- Special Collections and Archives Research Center

- Undergrad Research & Writing Studio

- Graduate Student Commons

- Tutoring Services

- Northwest Art Collection

Digital Projects

- Oregon Explorer

- Oregon Digital

- ScholarsArchive@OSU

- Digital Publishing Initiatives

- Atlas of the Pacific Northwest

- Marilyn Potts Guin Library

- Cascades Campus Library

- McDowell Library of Vet Medicine

An Emergency Physician’s Path pp 551–555 Cite as

Preparing Oral and Poster Presentations

- Kimberly M. Rathbun 5

- First Online: 02 March 2024

A poster or oral presentation is a great way to share your research project and get feedback. Designing a poster or preparing an oral presentation should be done within the guidelines set forth by the conference. Traditional posters and oral presentations convey the same information in different formats. When presenting your study, you should know all the details of the project and be able to field any questions from the audience.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Suggested Readings

Barker E, Phillips V. Creating conference posters: structure, form and content. J Perioper Pract. 2021;31(7–8):296–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gundogan B, Koshy K, Kurar L, Whitehurst K. How to make an academic poster. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2016;11:69–71.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Naegle KM. Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17(12):e1009554.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Emergency Medicine, AU/UGA Medical Partnership, Athens, GA, USA

Kimberly M. Rathbun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kimberly M. Rathbun .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Emergency Medicine, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA, USA

Robert P. Olympia

Elizabeth Barrall Werley

Jeffrey S. Lubin

MD Anderson Cancer Center at Cooper, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ, USA

Kahyun Yoon-Flannery

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Rathbun, K.M. (2023). Preparing Oral and Poster Presentations. In: Olympia, R.P., Werley, E.B., Lubin, J.S., Yoon-Flannery, K. (eds) An Emergency Physician’s Path. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47873-4_79

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47873-4_79

Published : 02 March 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-47872-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-47873-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Poster Presentations

Read time: 8 minutes

This section will outline how to communicate your scientific research in the format of a poster presentation, and provide guidance on designing your poster.

Sections in this chapter

Environment and audience, poster vs. talk, verbal aspect, poster design, virtual posters.

Many conferences have poster presentation sessions along with oral presentations. The poster presentation is a format introduced into the American Chemical Society meetings in the 1970s. This format allows more people the opportunity to present their work since many posters can be scheduled for the same time period and in one large room.

The format of a poster presentation allows for a one-on-one and in-depth discussion between the presenter and viewer. For this reason, poster sessions are often combined with social mixers, where people can walk around and browse the posters.

Theoretically, the poster audience is more broad and diverse, since many disciplines present in one large room. For this reason, your poster should be readable or understandable in less than 5 minutes by someone not in your field, who has only general knowledge of the research area. People browse posters and look for something that interests them, and on average spend around 90 seconds viewing a single poster. However, the people who actually attend your poster will likely be those who are interested in your work or work in a similar area.

Attaching business cards and one-page copies of your poster allow viewers to contact you later and get the information without having to take notes.

Table 21.1. Differences between posters and oral presentations (talks)

Posters are mostly non-verbal and visual, so most of this chapter will discuss poster design. However, the verbal aspect of the poster presentation is where many presenters struggle! The most common mistake is for presenters to launch into a detailed overview of the slides, starting at the introduction and working their way through the poster all the way to the acknowledgements. Even a 5-minute overview is too long at a poster! The issue with this approach is that the viewer cannot listen to you and think critically at the same time, and they lose the autonomy of exploring your visuals at their own pace. Follow these tips for a successful poster presentation:

- If someone shows interest in your poster, smile and introduce yourself, then wait.

- If they start to intently view your poster, let them do this silently without interruption.

- If they turn to you, ask if they would like a short overview of your work.

- Start with the key finding, from your conclusion, and state it in a single sentence.

- Then move on to your motivation and methods and details about the results.

- Make sure to pause and make eye contact, which will let viewers ask questions.

- Ask your viewer questions to gauge their interest and background, and encourage discussion

- Point to relevant things on your poster as you present.

There are some aspects of etiquette to giving poster presentations. First of all, you should be at your poster during the specified times. Socializing with friends should be a lower priority, so if your lab members are hanging around your poster you can politely ask them to give you some space. Stay tuned to social cues from your viewer, and let them view the poster silently if they seem to want that. Lastly, consider waiting until after the presentation for drinks.

Format and Size

Posters should be concise, organized, and self-explanatory: the best way to achieve this is to have a central and obvious message. Beyond that, a poster should be easy to view from 1-2 meters away, which means you should limit text to short paragraphs (<20 lines) or bullet points. Remember that you are not writing a full paper! Any text should be in a simple Sans-Serif typeface ( e.g., Arial, Verdana, Calibri) with adequate spacing, and large enough to easily read. Consider using a different font style for the title and headings than the main text. Follow this guide for minimum text sizes:

Title 100 pt (Verdana, bold)

Authors 36 pt (Arial, bold)

Headings 54 pt (Verdana, bold)

Main text 32 pt (Arial)

References 28 point (Arial)

Instead of text, use figures, graphs, and charts to visually communicate of your work. Make sure the text labels and axes are large enough to easily read, following the guide above.

Check the conference website for instructions on the acceptable dimensions for posters. The typically allowed dimensions are 90 cm (36”) high x 122 cm (48”) wide. There are two ways to create your poster (Figure 21.1): 1) print 12-20 regular slides on 8.5″ x 11″ pieces of paper, and arrange them; 2) create a single large poster sheet, either printed on paper or fabric, to fill the whole space.

Posters have all the components of a paper, organized into sections. These sections are not always separate on your poster (see below ‘Layout’), but they should be present in one way or another. See Table 21.2. for a list of sections and their descriptions.

Table 21.2. Poster sections

Sections in your poster are outlined by headings. Instead of using section titles like “Introduction”, use descriptive headings that tell the viewer the key message of the section (Table 21.3).

Table 21.3. Replacing poster headings with descriptive headings

Layout & design.

A thoughtful layout will provide a natural flow that guides people through your poster. It is best to arrange your poster in blocks of columns, so that the audience reads from left to right, top to bottom using “reader’s gravity”. You can number each section block or heading to help the reader to follow the flow of the material.

Posters with symmetric layouts and plenty of ‘white space’ are more visually pleasing, and can also help with flow. Also, place graphics and text to create a symmetrical balance.

Instead of headings like “Introduction”, use descriptive headings to clearly communicate your main points. A lack of headings, plus an asymmetric layout of the material, makes it difficult for the viewer to follow the flow or find a particular section of the poster.

A popular traditional poster format (see Figure 21.2) has a landscape layout and three columns: 1) Introduction and Methods, 25% width; 2) Results arena, 50% Width; 3) Conclusions and Acknowledgements, 25% width. A more modern landscape layout (Figure 21.3) was designed by Mike Morrison , [1] which features a large takeaway sidebar with the key message, and a QR code that links to the paper or a website. This modern poster format also works well in a portrait format (Figure 21.4).

Stick to a theme of 2 or 3 colours, using an accessible colour scheme , and be consistent with the use of colours that have meaning (e.g., in legends). Don’t be afraid to use b right colours to attract attention, but if you overuse them you will wear out readers’ eyes. For the body of your poster, use a light coloured background and dark coloured text. Dark backgrounds with light letters can become tiring to read but are often used for headings.

Don’t start from scratch

There are many poster templates available online! Here are some PowerPoint templates and guides:

BetterPosters.blogspot.com landscape template

BetterPosters.blogspot.com portrait template

BetterPosters.blogspot.com Twitter template

Queen’s Chemistry Landscape Poster Template

Queen’s Chemistry Portrait Poster Template

Online conferences and symposia are becoming more common, including virtual poster sessions. Virtual posters can have animations, videos, and audio narration. These posters can take many formats, but one common format is for the RSC Poster Day on Twitter. They published this guide to creating a version of your poster on Twitter, and how to identify your work using the right hashtag ( e.g., #RSCOrganic, #RSCAnalytical).

Here are some links to the 2020 winners of #RSCPoster Day.

Super excited to share my research on the use of electrochemistry as a tool for drug detection in complex matrices as a #comicsforscience for my first #RSCPoster #RSCAnalytical #RSCPhys #electrochem @DennanyChem @PamelaAllanChem @CarnegieUni @StrathChem @StrathForensics pic.twitter.com/ISzJ55Hbqh — Kelly Brown (@kellybrown_94) March 3, 2020

Excited to share my first #RSCPoster and looking forward to interact with all the #chemtweeps to discuss magnetic photocatalysis 🧲💡 #RSCCat #RSCNano #RSCMat pic.twitter.com/XzwxnIYJyh — Julio Terra, Ph.D. (@_julioterra) March 3, 2020

Here we go again! NEON can deny, oops I mean no-one can deny Hydrogen's BRIGHT future for renewable energy! Here is my fun twist on my LIGHT weight hydrogen storage for mobile fuel cell applications research at @lborouniversity @LboroScience #RSCEnergy #RSCPoster pic.twitter.com/8DzRUHobiA — Lizzie Ashton (@LizzieRAshton) March 3, 2020

- " Critique: The Morrison billboard poster ", Zen Faulkes, April 11, 2019, Better Posters. Accessed 2020-08-31 ↵

Principles of Scientific Communication Copyright © 2020 by Amanda Bongers and Donal Macartney is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Argonne National Laboratory

Planning your oral/poster presentation.

STEM experts routinely present posters and deliver oral presentations at various points throughout their careers. Presentations give researchers a chance to share their work with different groups of people, which increases the visibility of their work and can also inspire collaboration and constructive feedback.

One advantage that presentations have over written communication is that they allow communication to happen as a direct, two-way exchange. During a presentation, the audience is right there in front of you. You can ask audience members questions, visually gauge their level of understanding/interest, and get feedback from them.

But with these benefits comes a new set of challenges, the foremost being time constraints. As a speaker, you are limited by the time allotted for your presentation and by the limited attention span of your audience. And just as you can see your audience, your audience now can see you. This means that you, the speaker, must pay special attention to the additional visual information that audiences now have access to, such as your appearance, your tone of voice, and visual aids like PowerPoint slides.

Presentations, like reports, require careful planning and attention to detail. Brainstorming, the spontaneous process of generating ideas, is often the first step in planning a presentation. After brainstorming ideas, and writing them down, you should review these ideas and filter out extraneous ones until you are left with those that are most important. Ideas are relevant if they: (1) explain the purpose of your presentation, (2) make sense to your audience, and (3) explain or support your goals.

After brainstorming and identifying the ideas that are most relevant to your presentation goals, these ideas must then be organized in a logical pattern. We do this by creating an outline. The main purpose of an outline is to organize your ideas within a structure that gives your audience easy access to them.

As with a science report, a presentation outline can take on various formats, including a traditional bulleted outline, a diagram, a storyboard, or even a grid of sticky notes that you can rearrange. Regardless of how you choose to craft your outline, in the end, all outlines should include the key takeaway messages and evidence to support them, all organized within a logical structure. You should also make note of the tables and/or figures you would want to include in your presentation, as well as any external references.

You can adapt parts of your science report or project report to suit your presentation outline; however the presentation outline should NOT mirror your report or report outline. Due to time constraints, presenters must be more selective in their presentations than in their reports when deciding which details to include.

Review Your Ideas

During or following your brainstorming session, review the ideas you have come up with and select those that best: (1) explain the purpose of your presentation, (2) are pertinent to your audience, and (3) define or support your goals.

Your purpose

The reason for the presentation. Are you trying to summarize, analyze, evaluate, argue/persuade, etc.? Use this information to define the layout of your poster or slide presentation.

Your audience

Consider what your audience would find most interesting about your research project, what they already know about your topic and what they may not know. This information will tell you where to start your presentation and what attention-grabbing opening statement to use on your audience (also see Engaging your Audience ).

Decide on your message(s). What are the 2–3 main points that you want your audience to remember? Focus your presentation around these takeaways.

- Research & Faculty

- Offices & Services

- Information for:

- Faculty & Staff

- News & Events

- Contact & Visit

- Quick Facts

- Survey Summary

- Gender Neutral Restrooms

- Undergraduate Study

- Biomedical Engineering (BS)

- ABET Objectives & Outcomes

- Combined BS/MS Program

- Career Resources

- Research Opportunities

- Summer Research Grants in BME

- Special Programs

- Student Awards

- Student Organizations and Professional Societies

- Graduate Study

- Biomedical Engineering (MS)

- Curriculum & Requirements

- Biomedical Engineering (PhD)

- PhD Timeline

- Courses Collapse Courses Submenu

- Biomechanics

- Biomaterials and Regenerative Engineering

- Cell and Molecular Engineering

- Imaging and Biophotonics

- Medical Devices and Instrumentation

- Neural Engineering

- Research Areas

- Affiliate Centers & Institutes

- Faculty Start-ups

- Core Faculty

- Administrative Faculty

- Courtesy Faculty

- Teaching Faculty

- Adjunct Faculty

- Advisory Board

- News Archive

- BME Seminar Series

- Past Seminar Speakers Collapse Past Seminar Speakers Submenu

- Careers in the Department

- Faculty Openings

- Other Opportunities

- Student Resources

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Purchasing Procedures

- Reserve a Room

- Templates for Oral and Poster Presentations

- Travel Reimbursement Procedure

- Visitor Travel Reimbursement Procedure

- Northwestern Engineering

Resources Templates for Oral and Poster Presentations

Oral presentation template

Poster presentation template

More in this section

- Engineering Home

- BME Department

Contact Info

Department of Biomedical Engineering M c Cormick School of Engineering and Applied Science 2145 Sheridan Road Evanston, IL 60208 Phone: 847-467-1213 Fax: 847-491-4928 Email Department

Customer Reviews

Free research poster powerpoint templates.

About our free research poster templates

Easy to use and customize.

▪ Change colors with one click ▪ Most standard US and international poster sizes. ▪ Support for all PowerPoint versions ▪ Only basic PowerPoint skills required ▪ Fully customizable ▪ Instructions included with the poster templates. ▪ Online video tutorials ▪ Configured to print professionally ▪ Additional layouts included in each template

40 color schemes built-in to every research poster template

Five reasons to print your poster with us >, professionally designed research poster templates.

QUICK FIND POSTER TEMPLATES American standard poster sizes (inches) 30x40 | 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual International common poster sizes (centimeters) 91x122 | 70x100 | 100x140 | 100x100 | 100x200 | A0 | A1 | Virtual IMPORTANT Check the requirements of your conference before you download and work on a poster template. If you need further assistance, our phone support is available and free. We are here to provide the best service you can ask for.

Step-by-Step Tutorials

This series of short videos and animated tutorials will walk you through the research poster-making process, answering the most common questions along the way.

Need further poster template assistance? 510.649.3001

Free powerpoint poster templates for research poster presentations.

Poster template design: Aragon Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Beaumont Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Newfield Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Winchester Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Lockwood Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Kensington Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Stone A new, simplified concept for better poster design Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download A0 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Marquee Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Winston Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download A0 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Chamberlain Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

Poster template design: Forrest Standard poster sizes in inches (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 36x48 | 36x56 | 36x60 | 36x72 | 36x96 | 42x60 | 42x72 | 42x90 | 44x44 | 30x40 | 48x48 | 48x72 | 48x96 | Trifold | Virtual - Standard Screen (4:3 Ratio) | Virtual - Wide Screen (16:9 Ratio) Standard poster sizes in centimeters (Height x Width) - Click on a size to download 122x91 | 100x70 | 140x100 | 100x100 | 200x100 | A0 | A1 ► View Samples ► Learn how to customize the template colors

DIGITAL POSTER PRESENTATION HANDOUTS

Free with a printed poster order.

A feature-packed alternative to traditional paper poster handouts

Instant QR Code Generator

Add functionality to your poster! Share a link to a page, your email or additional info on the web. It's easy, free and further connects your audience!

Professional Trifold Poster Boards

Ready to use out of the box. Great solution for tabletop 36x48 Trifold poster presentations. Price includes printing, mounting and free Ground FedEx shipping.

Poster Font Size Checker

A convenient way to visualize what size the text will be on your printed poster. Wondering how big the fonts will be on your poster? Download and print this PDF on your desktop printer.

Quick access to ALT code symbols

Click here to choose from over 350 easy to copy and use ALT code symbols.

Fabric Research Posters