Case Study 1: A 55-Year-Old Woman With Progressive Cognitive, Perceptual, and Motor Impairments

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, case presentation, what are diagnostic considerations based on the history how might a clinical examination help to narrow the differential diagnosis.

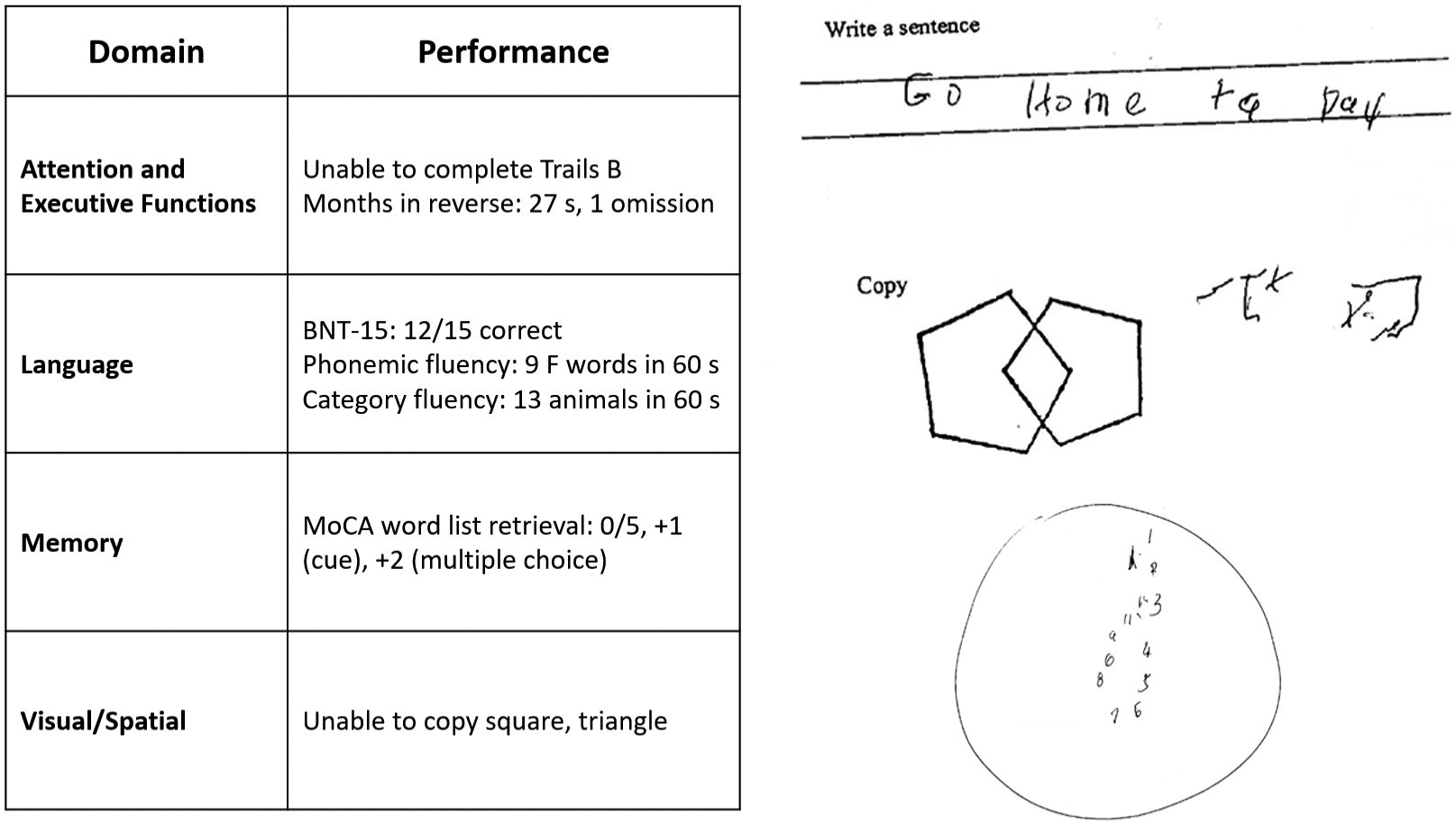

How Does the Examination Contribute to Our Understanding of Diagnostic Considerations? What Additional Tests or Studies Are Indicated?

| Feature | Posterior cortical atrophy | Corticobasal syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive and motor features | Visual-perceptual: space perception deficit, simultanagnosia, object perception deficit, environmental agnosia, alexia, apperceptive prosopagnosia, and homonymous visual field defect | Motor: limb rigidity or akinesia, limb dystonia, and limb myoclonus |

| Visual-motor: constructional dyspraxia, oculomotor apraxia, optic ataxia, and dressing apraxia | ||

| Other: left/right disorientation, acalculia, limb apraxia, agraphia, and finger agnosia | Higher cortical features: limb or orobuccal apraxia, cortical sensory deficit, and alien limb phenomena | |

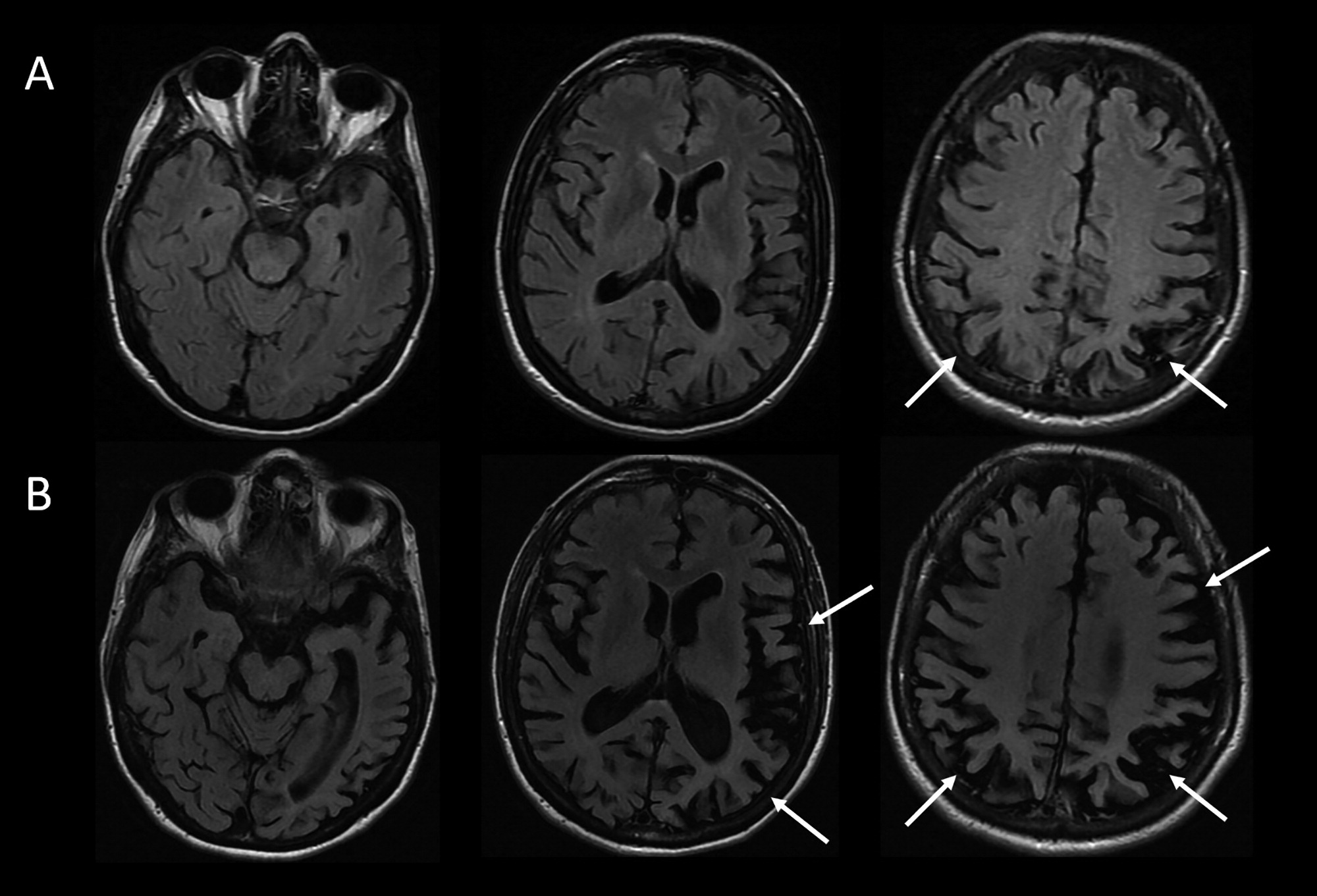

| Imaging features (MRI, FDG-PET, SPECT) | Predominant occipito-parietal or occipito-temporal atrophy, and hypometabolism or hypoperfusion | Asymmetric perirolandic, posterior frontal, parietal atrophy, and hypometabolism or hypoperfusion |

| Neuropathological associations | AD>CBD, LBD, TDP, JCD | CBD>PSP, AD, TDP |

Considering This Additional Data, What Would Be an Appropriate Diagnostic Formulation?

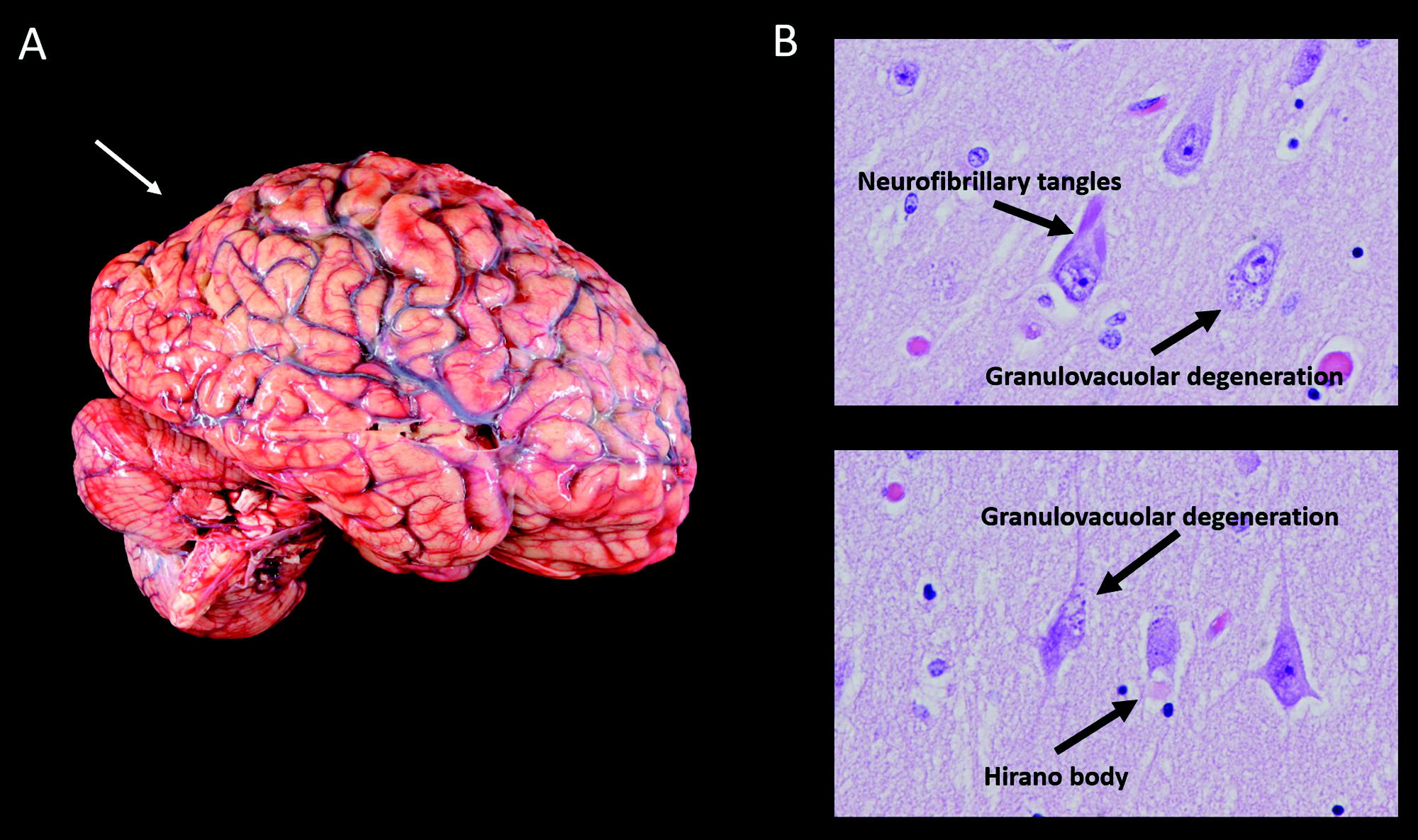

Does information about the longitudinal course of her illness alter the formulation about the most likely underlying neuropathological process, neuropathology.

| Feature | Case of PCA/CBS due to AD | Exemplar case of CBD |

|---|---|---|

| Macroscopic findings | Cortical atrophy: symmetric, mild | Cortical atrophy: often asymmetric, predominantly affecting perirolandic cortex |

| Substantia nigra: appropriately pigmented | Substantia nigra: severely depigmented | |

| Microscopic findings | Tau neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques | Primary tauopathy |

| No tau pathology in white matter | Tau pathology involves white matter | |

| Hirano bodies, granulovacuolar degeneration | Ballooned neurons, astrocytic plaques, and oligodendroglial coiled bodies | |

| (Lewy bodies, limbic) |

Information

Published in.

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Corticobasal Syndrome

- Atypical Alzheimer Disease

- Network Degeneration

Competing Interests

Funding information, export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Purchase Options

Purchase this article to access the full text.

PPV Articles - Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Snapsolve any problem by taking a picture. Try it in the Numerade app?

Winningham's Critical Thinking Cases in Nursing

Barbara a preusser, julie s snyder, mariann m harding, patients with multiple disorders - all with video answers.

Section 136

Name Class/Group Date Group Members INSTRUCTIONS All questions apply to this case study. Your responses should be brief and to the point. When asked to provide several answers, list them in order of priority or significance. Do not assume information that is not provided. Please print or write clearly. If your response is not legible, it will be marked as ? and you will need to rewrite it.

As you perform your initial assessment, you note superficial partial-thickness burns on A.N.'s right anterior leg, left anterior and posterior leg, and anterior torso. Shade the affected areas, then using the “rule of nines,” calculate the extent of A.N.'s burn injury.

Because you are concerned about possible smoke inhalation, what signs will you monitor A.N. for?

Interpret A.N.'s laboratory results.

A.N. is undergoing burn fluid resuscitation using the standard Baxter (Parkland) formula. She was admitted at 0400. She weighs 110 pounds. Calculate her fluid requirements, specify the fluids used in the Baxter (Parkland) formula, specify how much will be given, and indicate what time intervals will be used.

A.N. is in severe pain. What is the drug of choice for pain relief following burn injury, and how should it be given?

Because of her significant burn injury, A.N. is at high risk for infection. What measures will you institute to prevent this?

A.N.'s burns are to be treated by the open method with topical application of silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene). When caring for A.N., which interventions will you perform? (Select all that apply.) a. Maintain the room temperature at 85° F (29.4° C). b. Use clean technique when changing A.N.'s dressings. c. Monitor CBC frequently, particularly the white blood cells. d. Do not allow her to bathe for the initial 72 hours following injury. e. Apply a 1 ?16-inch film of medication, covering entire burn. f. Shave all hair within the wound beds.

A.N. has one area of circumferential burns on her right lower leg. What complication is she in danger of developing, and how will you monitor for it?

What interventions will facilitate maintaining A.N.'s peripheral tissue perfusion?

A special burn diet is ordered for A.N. She has always gained weight easily and is concerned about the size of the portions. What diet-related teaching will you provide?

Describe interventions that you could use to assist in meeting A.N.'s nutrition goals.

Case Examples

Examples of recommended interventions in the treatment of depression across the lifespan.

Children/Adolescents

A 15-year-old Puerto Rican female

The adolescent was previously diagnosed with major depressive disorder and treated intermittently with supportive psychotherapy and antidepressants. Her more recent episodes related to her parents’ marital problems and her academic/social difficulties at school. She was treated using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Chafey, M.I.J., Bernal, G., & Rossello, J. (2009). Clinical Case Study: CBT for Depression in A Puerto Rican Adolescent. Challenges and Variability in Treatment Response. Depression and Anxiety , 26, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20457

Sam, a 15-year-old adolescent

Sam was team captain of his soccer team, but an unexpected fight with another teammate prompted his parents to meet with a clinical psychologist. Sam was diagnosed with major depressive disorder after showing an increase in symptoms over the previous three months. Several recent challenges in his family and romantic life led the therapist to recommend interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A).

Hall, E.B., & Mufson, L. (2009). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A): A Case Illustration. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38 (4), 582-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410902976338

© Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA, https://sccap53.org/, reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA.

General Adults

Mark, a 43-year-old male

Mark had a history of depression and sought treatment after his second marriage ended. His depression was characterized as being “controlled by a pattern of interpersonal avoidance.” The behavior/activation therapist asked Mark to complete an activity record to help steer the treatment sessions.

Dimidjian, S., Martell, C.R., Addis, M.E., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2008). Chapter 8: Behavioral activation for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 343-362). New York: Guilford Press.

Reprinted with permission from Guilford Press.

Denise, a 59-year-old widow

Denise is described as having “nonchronic depression” which appeared most recently at the onset of her husband’s diagnosis with brain cancer. Her symptoms were loneliness, difficulty coping with daily life, and sadness. Treatment included filling out a weekly activity log and identifying/reconstructing automatic thoughts.

Young, J.E., Rygh, J.L., Weinberger, A.D., & Beck, A.T. (2008). Chapter 6: Cognitive therapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 278-287). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Nancy, a 25-year-old single, white female

Nancy described herself as being “trapped by her relationships.” Her intake interview confirmed symptoms of major depressive disorder and the clinician recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Persons, J.B., Davidson, J. & Tompkins, M.A. (2001). A Case Example: Nancy. In Essential Components of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy For Depression (pp. 205-242). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10389-007

While APA owns the rights to this text, some exhibits are property of the San Francisco Bay Area Center for Cognitive Therapy, which has granted the APA permission for use.

Luke, a 34-year-old male graduate student

Luke is described as having treatment-resistant depression and while not suicidal, hoped that a fatal illness would take his life or that he would just disappear. His treatment involved mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which helps participants become aware of and recharacterize their overwhelming negative thoughts. It involves regular practice of mindfulness techniques and exercises as one component of therapy.

Sipe, W.E.B., & Eisendrath, S.J. (2014). Chapter 3 — Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy For Treatment-Resistant Depression. In R.A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches (2nd ed., pp. 66-70). San Diego: Academic Press.

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Sara, a 35-year-old married female

Sara was referred to treatment after having a stillbirth. Sara showed symptoms of grief, or complicated bereavement, and was diagnosed with major depression, recurrent. The clinician recommended interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for a duration of 12 weeks.

Bleiberg, K.L., & Markowitz, J.C. (2008). Chapter 7: Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 315-323). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Peggy, a 52-year-old white, Italian-American widow

Peggy had a history of chronic depression, which flared during her husband’s illness and ultimate death. Guilt was a driving factor of her depressive symptoms, which lasted six months after his death. The clinician treated Peggy with psychodynamic therapy over a period of two years.

Bishop, J., & Lane , R.C. (2003). Psychodynamic Treatment of a Case of Grief Superimposed On Melancholia. Clinical Case Studies , 2(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650102239085

Several case examples of supportive therapy

Winston, A., Rosenthal, R.N., & Pinsker, H. (2004). Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing.

Older Adults

Several case examples of interpersonal psychotherapy & pharmacotherapy

Miller, M. D., Wolfson, L., Frank, E., Cornes, C., Silberman, R., Ehrenpreis, L.…Reynolds, C. F., III. (1998). Using Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) in a Combined Psychotherapy/Medication Research Protocol with Depressed Elders: A Descriptive Report With Case Vignettes. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research , 7(1), 47-55.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 27 June 2016

A case series of 223 patients with depersonalization-derealization syndrome

- Matthias Michal 1 ,

- Julia Adler 1 ,

- Jörg Wiltink 1 ,

- Iris Reiner 1 ,

- Regine Tschan 1 ,

- Klaus Wölfling 1 ,

- Sabine Weimert 1 ,

- Inka Tuin 1 ,

- Claudia Subic-Wrana 1 ,

- Manfred E. Beutel 1 &

- Rüdiger Zwerenz 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 16 , Article number: 203 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

41 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Depersonalization-derealization syndrome (DDS) is an underdiagnosed and underresearched clinical phenomenon. In Germany, its administrative prevalence is far below the threshold for orphan diseases, although according to epidemiological surveys the diagnosis should be comparable frequent as anorexia nervosa for instance. Against this background, we carried out a large comprehensive survey of a DDS series in a tertiary mental health center with a specialized depersonalization-derealization clinic. To reveal differential characteristics, we compared the DDS patients, who consulted the specialized depersonalization-derealization clinic, with a group of patients with depressive disorders without comorbid DDS from the regular outpatient clinic of the mental health center.

The sample comprised 223 patients with a diagnosis of depersonalization-derealization-syndrome and 1129 patients with a depressive disorder but without a comorbid diagnosis of DDS. DDS patients were described and compared with depressive outpatients in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, treatment history, treatment wishes, clinical symptomatology, prevailing psychosocial stressors, family history of common mental disorders and history of childhood trauma.

Despite the high comorbidity of DDS patients with depressive disorders and comparable burden with symptoms of depression and anxiety, the clinical picture and course of both patient groups differed strongly. DDS patients were younger, had a significant preponderance of male sex, longer disease duration and an earlier age of onset, a higher education but were more often unemployed. They tended to show more severe functional impairment. They had higher rates of previous or current mental health care utilization. Nearly all DDS patients endorsed the wish for a symptom specific counseling and 70.7 % were interested in the internet-based treatment of their problems. DDS patients had lower levels of self-rated traumatic childhood experiences and current psychosocial stressors. However, they reported a family history of anxiety disorders more often.

In consideration of the selection bias of this study, this case series supports the view that the course of the DDS tends to be long-lasting. DDS patients are severely impaired, utilizing mental health care to a high degree, which nevertheless might not meet their treatment needs, as patients strongly opt for obtaining disorder specific counseling. In view of the size of the problem, more research on the disorder, its course and its optimal treatment is urgently required.

Depersonalization-derealization syndrome as named in the ICD-10 [ 1 ] (or depersonalization-derealization disorder as termed in the DSM-5 [ 2 ] is an underresearched clinical phenomenon [ 3 , 4 ]. Depersonalization-derealization syndrome (DDS) is defined by feeling detached from the own feelings and/or experiences (depersonalization, DP) and/or experiencing objects, people, and/or surroundings as unreal, distant, artificial, and lifeless (derealization, DR) while reality testing remains intact (ICD-10 [ 1 ]). Further, symptoms of depersonalization and derealization are not better explained by another mental disorder or medical condition and the symptoms cause significant impairment (DSM-5 [ 2 ]). The typical DDS patient, reports that the disorder started before age 25, and that the DP/DR symptoms are present all day long since several years [ 5 – 7 ]. Epidemiological surveys suggest that the current prevalence rate of the depersonalization-derealization syndrome is approximately 1 % in the general population [ 5 – 7 ]. However, the disorder is severely underdiagnosed. For example, in the year 2006 the administrative 1-year-prevalence of the ICD-10 diagnosis “depersonalization-derealization syndrome” was as low as 0.007 % according to the registry of a statutory health insurance fund in Germany [ 4 ]. Experts assume this huge diagnostic gap is due to the following reasons: Many clinicians are unfamiliar with the clinical picture and the diagnostic criteria of the disorder. They universally consider symptoms of DP/DR as secondary to a depressive or anxiety disorder, even if these symptoms are all day long present for months and years, or they even misinterpret these symptoms as psychotic although patients are free from any psychotic sings (such as hallucinations, delusions, severe thought disorders, catatonia etc.) [ 3 – 5 , 8 – 10 ]. Moreover, diagnostic awareness is hampered by the patients themselves because many of them are “reluctant to divulge their symptoms out of fears of being thought mad” [ 8 ]. Therefore, it usually takes many years from the initial contact with a mental health service until the right diagnosis is made [ 3 , 4 , 11 ].

The current nosological knowledge about the DDS, as it is reported in the recent version of the DSM-5, is largely based on historic descriptions of the disorder, small case-control studies and two descriptive case series with a total sum of 321 patients from specialized clinics or research units in London (UK) and New York (USA). Concerning the etiology of DDS, it has been found that harm-avoidant temperament was associated with DDS in a cross-sectional study [ 12 ]. Another cross-sectional study comparing healthy controls with 49 DDS patients demonstrated that emotional abuse was associated with severity of DP/DR but not severe forms of childhood maltreatment [ 13 ]. A prospective cohort study found that the only risk factor for severe adult depersonalization at the age of 36 was teacher-estimated childhood anxiety 20 years before. Exposition to environmental risk factors such as socio-economic status, parental death or divorce, and self-reported accidents did not predict later DDS [ 14 ]. From an evolutionary perspective, symptoms of DP/DR are considered as a hard-wired response to severe stress, which is perpetuated according to various disease models of DDS by personality factors such as low capacities of self-regulation (e.g., low self-esteem, low affect tolerance, low cohesiveness of the self) [ 3 , 8 , 15 ]. Previous case series from specialized treatment units in London (UK) and New York (USA) reported a sex ratio of 1:1 or even a slight male preponderance [ 6 ], with an early age of onset usually before age 25, and a high comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders [ 6 , 16 ]. Both case series demonstrated that the condition had a high chronicity and tended to be resistant to pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments [ 6 , 16 ]. To date, there is no approved medication for the treatment of DDS and there is no randomized controlled trial on the psychotherapeutic treatment of DDS [ 3 ].

As the current disease knowledge of DDS has only a small empirical basis, at least as compared to mental disorders with similar prevalence rates and mental health impact, the principle aim of our study was to support and extend the knowledge about the clinical features of the DDS. For that purpose, we examined a large consecutive outpatient sample of DDS patients from the depersonalization-derealization clinic of our department, which has been established in 2005. Patients usually become aware of the clinic by online research about their main complaints (e.g. “feeling unreal”), they are usually self-referred and they typically seek a second opinion regarding their diagnoses and treatment options.

With our study we aimed to address two main questions. Firstly, we sought to describe the typical clinical features and demographic characteristics of patients with DDS as depicted in our clinical standard assessment. Although our case series study is primarily meant as a descriptive study, we included a comparison group form our outpatient clinic in order to bring out the putative differential characteristics of the DDS patients more clearly. For the latter purpose we used a large comparison group of patients suffering from depression without comorbid DDS. We compared both groups in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, treatment history, treatment wishes, clinical symptomatology, level of disability, prevailing psychosocial stressors, family history of common mental disorders, and severity of childhood trauma. We choose a sample of depressed patients for comparison for several reasons: First, this diagnostic entity represents the largest diagnostic group in our department. Second, depression is the most prevalent comorbid condition of DDS patients [ 6 ]. Third, depression is a well described and popular disorder thus making it easier for clinicians to acknowledge the similar and differential features of the two groups.

We expected that our case series will constitute an important confirmation and extension of the two previous case series and that it will stimulate further studies on the course, mechanisms and treatment of the disorder.

We consecutively included outpatients between January 2010 and December 2013, who consulted the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy of the University Medical Center Mainz (Germany). In Germany, Departments of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, usually established at most of all University Medical Centers, are mainly treating patients with depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders and eating disorders. All patients received a routine psychometric assessment and a clinical interview.

DDS patients who consulted the depersonalization-derealization clinic usually become aware of the clinic by internet research, that is to say, almost all were self-referred. The website of the clinic gives a vivid description of the symptoms and the clinical picture of the disorder. Further, all patients had a short telephone interview with M.M. prior to their consultation, to ensure that they suffer from severe depersonalization/derealization (e.g. as opposed to DP/DR attacks in the context of panic disorder) and to inform them about the focus of the consultation and the therapeutic options of the clinic. Patients from all over Germany were consulting the specialized clinic.

Patients from the comparison group were either self-referred or referred by local physicians and psychotherapist to receive a psychotherapeutic evaluation and treatment recommendations (usually regarding outpatient psychotherapy, inpatient or day clinic psychotherapy). The catchment area of the department is the Rhine-Main-area.

Patients who were treated in the context of the consultation and liaison service (e.g. cancer patients in cancer care units), or who were below age 18 or who had no standardized assessment, or who had no depressive disorder or DDS were excluded.

The sample comprised 223 patients with a definite diagnosis of depersonalization-derealization-syndrome (ICD-10: F48.1 [ 1 ]) and 1129 patients with a depressive disorder (dysthymia F34.1, or unipolar depression F32.x, or F33.x [ 1 ]) but without a comorbid diagnosis of DDS. The latter group will be indicated below as the “Only-Depressed-Group” (ODG). A total of 197 of the 223 patients diagnosed with DDS consulted the depersonalization-derealization clinic of the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy of the University Medical Center Mainz, the remaining 26 patients were diagnosed and treated in the general outpatient unit.

Clinical interview

All patients received a full clinical interview of at least 50 min duration by a psychological or medical psychotherapist. Clinical diagnoses of mental disorders were based on the diagnostic criteria for research of the ICD-10 [ 1 ]. The focus of the clinical interview was on the primary presenting problems of the patients and symptom diagnoses. The diagnosis of depersonalization-derealization syndrome was only given, if symptoms of DP/DR were persistent and lasted continuously for at least 1 month and if these symptoms were not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., unipolar depression, dissociative disorder, anxiety disorder, PTSD) or a medical condition (e.g., seizure disorder). Although the diagnostic criteria of the DDS do not demand specifications about the duration of the symptoms, most clinicians agree that the diagnosis should be only given if the symptoms persist for at least 1 month [ 3 ] (see Additional file 1 for comprehensive information about the diagnostic procedure).

Due to the peculiarities of the clinical interview, personality disorders were underreported in our medical records. This was mainly due to the time restriction of the clinical interview. As each patient received a written report about the diagnostic findings, each diagnosis in the record had to be explained to the patient in advance. The diagnosis of personality disorders was rarely made, as most clinicians believed that informing adequately about the diagnosis of a personality disorder requires more time. Because of this bias of underdiagnosing personality disorders in our records, we did not consider personality disorders in this paper.

Further, clinicians rated the social, occupational, and psychological functioning level of psychological functioning by means of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale [ 17 , 18 ]. Lower scores indicate lower levels of functioning. Scores in the range of 51–60 indicate moderate impairment due to symptoms (e.g., flat affect and circumlocutory speech, occasional panic attacks) or moderate difficulty in social, occupational, or school functioning (e.g., few friends, conflicts with peers or co-workers). In Germany, patients with indication for inpatient psychotherapy usually have a current functional level below GAF 50 [ 19 ].

Severity of DP/DR was assessed with the CDS-2, the two-item version of the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale (CDS [ 20 , 21 ]). The CDS-2 comprises the following two items of the CDS [ 22 ]: “My surroundings feel detached or unreal, as if there was a veil between me and the outside world” and “Out of the blue, I feel strange, as if I were not real or as if I were cut off from the world”. The response format of the CDS-2 was adopted from the Patient Health Questionnaire (“Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?/Not at all = 0/Several days = 1/More than half the days = 2/Nearly every day = 3”). The CDS-2 showed high reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.92) and was able to differentiate patients with clinically significant DP well from other groups (cut-off of CDS-2 ≥ 3, sensitivity = 78.9 %, specificity = 85.7 %). The CDS-2 sum score (range 0–6) correlated strongly ( r = 0.77 [ 22 ]) with depersonalization severity according to a structured clinical interview of depersonalization severity [ 23 ]. Immediately after the CDS-2 items, the patient questionnaire presented the following two questions with a yes/no response: Have you ever consulted a doctor or psychotherapist because of the above symptoms? Do you wish counseling about the above symptoms of depersonalization and derealization?

Severity of depression was measured with the depression module PHQ-9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire [ 24 ]. PHQ-9 scores ≥ 10 identified depressive disorders with a sensitivity of 81 % and a specificity of 82 %. Severity of anxiety was measured with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). The GAD-7 has seven items depicting various signs of generalized and other anxiety disorders (e.g. PTSD, panic disorder). GAD-7 scores range from 0 to 21, with scores of ≥5, ≥10, and ≥15 representing mild, moderate, and severe anxiety symptom levels [ 25 , 26 ]. The Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-Spin; [ 27 ]) was used for the measurement of social anxiety. The Mini-Spin has three items, which are rated on a 5-point-Likert scale from 0 = “not at all” to 4 = “extremely”. A cut-off score of 6 (range 0–12) separates individuals with social anxiety disorder from controls with good sensitivity (89 %) and specificity (90 %). Somatic symptoms severity was assessed with the 15 items of the PHQ-15. Scores range between 0–30. Scores above 15 identify individuals with high levels of somatic symptom severity respectively somatization severity [ 28 ]. The overall mental distress level was measured by the Global Severity Index (GSI) of the German version of the short Symptom Check List (SCL-9) [ 29 ]. The range of the GSI is 0 to 4 with higher values reflecting more dysfunction. The ten most common psychosocial stressors (e.g., financial status, family relationships, work, health) were assessed by the corresponding PHQ module on a three-point scale (not bothered = 0, bothered a little =1, bothered a lot =2) [ 30 , 31 ]. We also calculated the sum score of psychosocial stressors (possible range from 0 to 20). Further, we dichotomized the items (“not bothered” or “little bothered” = 0 versus bothered “a lot” = 1) for the use in a regression analysis. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) is a 28-item self-report inventory for the assessment of the extent of traumatic childhood experiences. The CTQ has a global score and scores for the subscales emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect and minimization [ 32 ]. For determining clinically significant levels of traumatization critically cut-points for the subscales have been determined [ 33 , 34 ]: emotional neglect (≥15), sexual abuse (≥8), physical abuse (≥8), physical neglect (≥10), emotional abuse (≥10). Further, patients gave written information about their socioeconomic details, their treatment history and family history.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, or age and sex adjusted mean, standard error and 95 % confidence interval, or numbers (n) and percentage. Continuous distributed scores were compared by students T -test. Categorical variables were compared by Chi-square tests. Associations of continuous data were tested by Pearson correlations. Correlations coefficients of the two groups were compared by the Fisher r-to-z transformation, which controls the correlation coefficients for the effect of different sample sizes. In order to control group differences for the effects of age and sex, we applied logistic regression analyses for binary variables and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for continuous variables. In order to evaluate the distinctiveness of the symptom dimensions depression, anxiety, social anxiety and DP/DR we performed a principal component analysis with varimax rotation on the pooled items of the CDS-2, PHQ-9, GAD-7 and Mini-Spin. Tests were considered to be significant at a p < 0.05, and all significance tests were two-tailed. Due to the large sample size, the interpretation of the results should focus on effect-sizes rather than p -values. SPSS 22.0 was used for the main statistical analysis and VassarStats for the Fisher r-to-z transformation ( http://vassarstats.net ).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. The group of DDS patients was of younger age and more often male than the “Only-Depressed-Group” (ODG). There was a significant preponderance of men in the DDS group with a female-to-male ratio of 98 to 125 (≈2 : 3). The DDS patients were living less often in a current partnership, were more often still living with their parents, more often holder of the German citizenship, had a higher educational level, but were more often unemployed.

Comorbid conditions, symptom burden and clinical course

DDS patients had a very high comorbidity with depressive disorders (84.8 %). As compared with ODG, DDS patients had a higher comorbidity with anxiety disorders, whereas somatoform disorders and PTSD were more prevalent in the ODG. The DDS group had more clinical Axis-I disorders than the controls (2.8 ± 1.0 versus 2.3 ± 1.1, T = 6.920, p < 0.0001). Only 21 from 223 DDS-patients (9.4 %) had no comorbid Axis-I disorder. DDS patients had an earlier age of onset and longer disease duration as the ODG (Table 2 ). DDS had its onset in 63.7 % ≤ age 25, in 17.9 % between age 26 and ≤ 40 and in 4.9 % > 40. There was no valid information about the age of onset for 20 DDS patients.

Table 3 shows that after adjustment for age and sex, DDS patients were comparably bothered like the ODG by symptoms of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7), and they had a similar global severity index (GSI). They had a lower burden with somatic symptoms (PHQ-15) and a slightly lower severity of social anxiety (Mini-Spin). However, severity of depersonalization (CDS-2) strongly separated both patient groups.

In order to evaluate the distinctiveness of the scales we performed a principal component analysis with varimax rotation on the pooled items of the CDS-2, PHQ-9, GAD-7 and Mini-Spin. The Factors were retained in the model based on inspection of the screeplot and eigenvalues > 1. Five factors were identified explaining 61 % of the variance. The items of the CDS-2 were clearly separated from the other scales (data not presented, see Additional file 2 ). Regarding the association of DP/DR with other symptom dimensions we found that the correlation coefficients of the severity of depersonalization (CDS-2) with anxiety (GAD-7, Mini-Spin), depression, general distress (GSI) and somatization were significantly weaker in the DDS group (Table 4 ).

Functional impairment

Both patient groups were markedly impaired by their symptoms (Table 5 ). After adjustment for age and sex, DDS patients endorsed that their symptoms disrupted their work and social life more strongly than ODG, while the impairment of home life was comparable. These differences were in the range of small to medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d 0.24 to 0.28). Clinicians rated the current and 1-year global level of functioning (GAF) of DDS patients significantly lower than those of the ODG. The difference of GAF was in the range of large effect sizes (Cohen’s d 0.54 to 0.67). Overall, the mean GAF of both groups was in the range of serious to moderate impairment of psychological, social and occupational functioning (GAF 50-60). In the DDS group, 35.2 % had a GAF below 50 which, in Germany, is considered as a criterion for inpatient psychotherapy.

Current psychosocial stressors

Overall, DDS patients endorsed being less bothered by psychosocial stressors than the ODG (Table 6 ). In the sex and age adjusted logistic regression model the following stressors were inversely associated with DDS: weight or appearance worries, difficulties with partners, stress at work or school, financial worries, having no one to turn to, as well as recent or past bad events. The same picture emerged regarding the total burden with psychosocial stressors (i.e. the sum score of the scale): 7.7 ± 3.6 in the DDS group versus 9.7 ± 4.0 in the ODG (T = 7.34, p < 0.0001). In the DDS group, there was no correlation between the severity of psychosocial stressors with severity of depersonalization (Pearson correlation between the psychosocial stressor sum score and CDS-2: r = 0.06, p = 0.39). In the ODG, however, CDS-2 correlated significantly with the sum of psychosocial stressors ( r = 0.31, p < 0.0001). The correlations coefficients differed significantly (Fisher r-to-z transformation: z = 3.53, p = 0.0004).

Family history and childhood adversities

In the age and sex adjusted regression analysis, only a FH of any anxiety disorder was significantly associated with DDS (Table 7 ). Regarding childhood adversities, DDS patients showed a similar level of traumatic childhood experiences; only, they endorsed slightly lower levels of physical and sexual abuse than ODG in the age and sex adjusted ANCOVA. Overall, the mean level of traumatic childhood experiences was in the range of minimal to low levels of traumatic childhood experiences (Table 8 ). Based on the critical cut-points of the CTQ [ 33 , 34 ], DDS patients reported the following rates of clinically significant levels of traumatization: Emotional abuse 44.7 %, emotional neglect 35.8 %, physical abuse 12.3 %, physical neglect 15.1 %, and sexual abuse 6.1 %. Altogether, 57.8 % of the DDS patients reported at least one significant traumatic childhood experience and 42.2 % none. In the DDS group, there was no association between severity of childhood traumatic experiences with severity of depersonalization (Pearson correlation of the CTQ total score with CDS-2: r = 0.05, p = 0.44). In the ODG, although weakly, CDS-2 correlated with the CTQ total score ( r = 0.20, p < 0.0001). The correlations coefficients of the two groups differed significantly (Fisher r-to-z transformation, z = 2.07, p = 0.0385).

Treatment history and health care wishes

Overall, DDS had a high treatment rate (Table 9 ). In the age and sex adjusted regression analysis, previous psychiatric inpatient treatment was much more likely in DDS patients than in the comparison group. The vast majority of the DDS patients endorsed firstly that they had previously consulted a doctor or psychotherapist because of DP/DR symptoms (92.7 % ( n = 202) versus 25.3 % ( n = 494)), and secondly that they were interested in DP/DR specific counseling (97.3 % ( n = 213) versus 35.0 % ( n = 446)). Those individuals of the ODG, who endorsed the wish for a DP/DR specific counseling, had higher CDS-2 scores than those denying this question (3.1 ± 1.9 versus 0.9 ± 1.3, T = 20.2, p < 0.0001). Further, DDS patients more often used the internet for searching information about their symptoms and specialists and were much more interested in internet-based treatment approaches.

We investigated a consecutive sample of 223 DDS-patients, who consulted a specialized depersonalization-derealization clinic and compared these patients with a large group of patients with depressive disorders. At the time of the consultation, DDS patients were of younger age, had a significant preponderance of male sex, longer disease duration, an earlier age of onset, and a higher education but they were more often unemployed. Their burden with symptoms of depression and anxiety was comparable, however, they tended to show more severe functional impairment, especially at work/school and in social life. Concerning health care utilization, DDS patients had extraordinary high rates of previous inpatient treatments during the last 12 months (25.6 %) and ongoing outpatient psychotherapy (40.4 %). Despite their high health care utilization, nearly all DDS patients endorsed the wish for a symptom specific counseling (92.7 %) and 70.7 % were interested in an internet-based treatment approach of their problems. With regard to risk factors, DDS patients tended to report lower levels of self-rated traumatic childhood experiences and current psychosocial stressors. However, they more often reported a family history of anxiety disorders. These findings both enhance and extend those of two earlier case series from other countries and health care systems reported by Simeon et al. ([ 16 ]) and Baker et al. ([ 6 ]).

Very similar to the London case series by Baker et al. ([ 6 ]), we found a preponderance of men (125 men to 98 women; Baker et al.: 112 men to 92 women [ 6 ]) and almost the same mean age of onset of 22.9 ± 9.7 years (22.8 ± 11.9 years [ 6 ]). A similar preponderance of male sex has been recently found for clinically significant DP/DR in a representative questionnaire based survey of pupils in the age of 12 to 18 after adjustment for general distress [ 35 ]. The determinants of this putative sex difference in the etiology of DDS warrant further research.

Compared with previous case series, we had a higher proportion of DDS patients reporting an age of onset > 25 years (22.8 %). This finding needs replication, because previous reports assumed that an onset after age of 25 is very rare (less than 5 %) [ 6 , 16 ]. The larger proportion of DDS patients with a late age of onset in our sample may reflect the increasing use of the internet for health research since 2003, as nearly all DDS patients were referred by themselves or “Dr. Google” respectively.

Similar to Simeon et al. ([ 16 ]) and Baker et al. ([ 6 ]) the main comorbid conditions were depressive and anxiety disorders. In the current sample only 9.4 % of the DDS in the current sample had no comorbid Axis-I disorder which is very close to 11 % in the case series of Simeon et al. [ 16 ]. Despite their high comorbidity and equal symptom burden with symptoms of depression and anxiety, the clinical picture and course of both patient groups differed strongly regarding sociodemographic variables, treatment history and treatment wishes, and risk factors. Again, a principal component analysis substantiated clearly the distinctiveness of DP/DR symptoms from anxiety and depression [ 36 ], thus contradicting a commonly held view that symptoms of DP/DR are only a negligible variant of depression and anxiety. The low correlation coefficients of depression or anxiety with DP/DR severity in the DDS group are pointing in the same direction. The much stronger correlation coefficients in the group of the only depressed patients might constitute one reason why many clinicians generally tend to lump together DP/DR symptoms with depression and anxiety. Concerning somatic symptoms severity, DDS patients endorsed significantly less somatic symptoms as compared to the controls. This is in accordance with a recent study, which found that DDS patients endorsed less bodily symptoms of anxiety than pure anxiety patients [ 37 ]. The lower burden by bodily symptoms may reflect DDS patients’ detachment from their body.

Although 57.8 % of the DDS patients reported at least one clinically significant traumatic childhood experience, the overall rate of childhood adversities was rather low among DDS patients and even lower than in the comparison group. In line with previous studies [ 6 , 13 , 14 ] this finding makes it unlikely that traumatic childhood experiences play a crucial role in the etiology of DDS. This highlights an apparent contradiction: Although symptoms of DP/DR are typically reactions to severe stress and trauma (e.g. in the case of PTSD [ 38 ]), DDS is usually not associated with severe forms of childhood traumatization or recent traumatic events. This suggests that for the development of DDS other factors play a superior role as compared to the exposition to severe traumatic events.

There was a high rate of a parental history of anxiety disorders in the DDS group. Akin to the findings of Baker et al. ([ 6 ]), DDS patients had a high rate of psychiatric disorders in a first degree relative (Baker et al.: 30 %; 35.8 % in this sample). This may point to an increased genetic vulnerability of the DDS group on the one hand and on the other hand to an increased environmental risk of being exposed to parents with anxiety disorders [ 39 ].

DDS patients endorsed that they were significantly less bothered by current psychosocial stressors than only depressed patients. This either indicates that they have less psychosocial stressors or that they tend to be less aware how psychosocial factors affect them. The latter interpretation would correspond to our clinical experience. Similar to patients with somatoform disorders, DDS patients initially are often unable to consider psychological problems and interpersonal conflicts as relevant causes, and they are convinced by a physical causation of their symptoms [ 3 ]. Frequently patients assume a brain tumor, an eye disease or drug induced brain damage as the cause of their symptoms and thus initially consult neurologists, ophthalmologists and other somatic specialists before visiting a mental health specialist [ 5 , 40 ]. The lack of any correlation between the severity of DP/DR symptoms with the level of current or past stressors might be interpreted in the same way. Severe depersonalization may constitute a “ceiling” effect, which prevents the patients from seeing relations between stressors and their maladaptive stress-response in form of DP/DR. This reminds strongly to a recent study of 291 DDS patients, which found that despite comparable high levels of anxiety, depersonalization and anxiety correlated only in patients with less severe symptoms of DP/DR but not in patients with very high levels of DP/DR [ 41 ]. That is to say, therapeutic progress would implicate that patients become aware how the DP/DR symptoms wax and wane depending on the level of the mobilized anxieties [ 3 ]. However, in order to test this hypothesis, a longitudinal investigation of these relationships would be necessary.

Making the above considerations, the following major limitations have to be kept in mind. First, our approach implicated a strong selection bias: The DDS-patients were mostly referred by themselves after they have searched the internet for their main complaints, while the comparison group represents patients largely from the near catchment area. This limits the generalizability of our results. For example, we cannot rule out that only DDS patients with a chronic course, poor satisfaction with their current treatment and poor treatment response consulted the depersonalization-derealization clinic of our department. A further bias may constitute the high educational level of the DDS patients. This high educational level could explain the high rate of self-referral among DDS patients coming to a specialized DDS clinic. Highly educated persons may have lower barriers to use the internet for information about health issues. However, the findings concerning chronicity and the high rate of previous health care utilization corresponded well with previous reports from the specialized units in London [ 6 ] and New York [ 16 ]. Secondly, the diagnoses were based on clinical interviews and not on structured clinical interviews as applied in research settings, thus limiting the validity of our diagnoses. However, diagnoses were enhanced by using the diagnostic research criteria of the ICD-10 and by the correlation of the findings with validated rating scales. Thirdly, family history of mental disorders and history of previous treatments was questionnaire based and not corroborated by independent sources.

Conclusions

Keeping the above limitations in mind, we found that DDS patients are severely impaired, are utilizing mental health care to a high degree, which nevertheless might not meet their treatment needs, as the patients are taking strong efforts for obtaining symptom specific counseling. This all may reflect the fact that many clinicians are not familiar with the diagnostic features of DDS and its treatment [ 3 ]. In Germany, a first step towards the improvement of DDS care may constitute the implementation of the guideline recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the depersonalization-derealization syndrome, which have been recently published by the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany [ 42 ]. In view of the size of the problem, much more research on the disorder, its course and its optimal treatment is urgently required.

Abbreviations

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CDS-2, 2-item scale of the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DDS, Depersonalization-derealization syndrome; DP, depersonalization; DR, derealization; DSM-5, 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; FH, family history; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; GSI, Global Severity Index; Mini-Spin, Mini-Social Phobia Inventory; OGD, Only-Depressed-Group; OR, odds ratio; PHQ-15, Somatic symptom scale from Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ-9, depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; SD, standard deviation; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; SE, standard error.

WHO. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Simeon D: Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder. In Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders . 5th edition. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; 2014: 459-469.

Michal M, Beutel M, Grobe T. Wie oft wird die Depersonalisations-Derealisationsstörung (ICD-10: F48.1) in der ambulanten Versorgung diagnostiziert? Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2010;56:74–83.

PubMed Google Scholar

Simeon D, Abugel J. Feeling Unreal: Depersonalization Disorder and the Loss of the Self. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Baker D, Hunter E, Lawrence E, Medford N, Patel M, Senior C, Sierra M, Lambert MV, Phillips ML, David AS. Depersonalisation disorder: clinical features of 204 cases. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:428–33.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Medford N, Sierra M, Baker D, David AS. Understanding and treating depersonalisation disorder. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005;11:92–100.

Article Google Scholar

Sierra M. Depersonalization: A New Look at a Neglected Syndrome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Michal M, Tavlaridou I, Subic-Wrana C, Beutel ME. Fear of going mad - differentiating between neurotic depersonalization-derealization-syndrome and paranoid schizophrenia. Nervenheilkunde. 2012;31:934–7.

Simon AE, Umbricht D, Lang UE, Borgwardt S. Declining transition rates to psychosis: the role of diagnostic spectra and symptom overlaps in individuals with attenuated psychosis syndrome. Schizophr Res. 2014;159:292–8.

Hunter EC, Phillips ML, Chalder T, Sierra M, David AS. Depersonalisation disorder: a cognitive-behavioural conceptualisation. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1451–67.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Knutelska M, Schmeidler J. Personality factors associated with dissociation: temperament, defenses, and cognitive schemata. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:489–91.

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J, Sirof B, Knutelska M. The role of childhood interpersonal trauma in depersonalization disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1027–33.

Lee WE, Kwok CH, Hunter EC, Richards M, David AS. Prevalence and childhood antecedents of depersonalization syndrome in a UK birth cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:253–61.

Michal M, Kaufhold J, Overbeck G, Grabhorn R. Narcissistic regulation of the self and interpersonal problems in depersonalized patients. Psychopathology. 2006;39:192–8.

Simeon D, Knutelska M, Nelson D, Guralnik O. Feeling unreal: a depersonalization disorder update of 117 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:990–7.

Saß H, Wittchen H, Zaudig M. Diagnostisches und Statistisches Manual psychischer Störungen: DSM- IV. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1996.

Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, Baumann BD, Baity MR, Smith SR, et al. Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1858–63.

Huber D, Brandl T, Henrich G, Klug G. Ambulant oder stationär? Psychotherapeut. 2002;47:16–23.

Sierra M, Berrios GE. The Cambridge Depersonalization Scale: a new instrument for the measurement of depersonalization. Psychiatry Res. 2000;93:153–64.

Michal M, Sann U, Niebecker M, Lazanowsky C, Kernhof K, Aurich S, Overbeck G, Sierra M, Berrios GE. Die Erfassung des Depersonalisations-Derealisations-Syndroms mit der Deutschen Version der Cambridge Depersonalisation Scale (CDS). Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2004;54:367–74.

Michal M, Zwerenz R, Tschan R, Edinger J, Lichy M, Knebel A, Tuin I, Beutel M. Screening for depersonalization-derealization with two items of the cambridge depersonalization scale. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2010;60:175–9.

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J. Development of a depersonalization severity scale. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14:341–9.

Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord. 2004;81:61–6.

Löwe B, Decker O, Muller S, Brahler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46:266–74.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7.

Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, Katzelnick D, Davidson JR. Mini-SPIN: A brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14:137–40.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–59.

Prinz U, Nutzinger DO, Schulz H, Petermann F, Braukhaus C, Andreas S. Comparative psychometric analyses of the SCL-90-R and its short versions in patients with affective disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:104.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Klapow J, Kroenke K, Horton T, Schmidt S, Spitzer R, Williams JB. Psychological disorders and distress in older primary care patients: a comparison of older and younger samples. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:635–43.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44.

Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1998.

Walker EA, Unutzer J, Rutter C, Gelfand A, Saunders K, VonKorff M, Koss MP, Katon W. Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:609–13.

Subic-Wrana C, Tschan R, Michal M, Zwerenz R, Beutel M, Wiltink J. Kindheitstraumatisierungen, psychische Beschwerden und Diagnosen bei Patienten in einer psychosomatischen Universitätsambulanz [Childhood trauma and its relation to diagnoses and psychic complaints in patients of an psychosomatic university ambulance]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2011;61:54–61.

Michal M, Duven E, Giralt S, Dreier M, Müller K, Adler J, Beutel M, Wölfling K. Prevalence and correlates of depersonalization in students aged 12–18 years in Germany. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:995–1003.

Michal M, Wiltink J, Till Y, Wild PS, Blettner M, Beutel ME. Distinctiveness and overlap of depersonalization with anxiety and depression in a community sample: results from the Gutenberg Heart Study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188:264–8.

Nestler S, Jay EL, Sierra M, David AS. Symptom Profiles in Depersonalization and Anxiety Disorders: An Analysis of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Psychopathology. 2015;48:84–90.

Lanius RA. Trauma-related dissociation and altered states of consciousness: a call for clinical, treatment, and neuroscience research. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015;6:27905.

Rutter M, Quinton D. Parental psychiatric disorder: effects on children. Psychol Med. 1984;14:853–80.

Michal M, Lüchtenberg M, Overbeck G, Fronius M. Gestörte visuelle Wahrnehmung beim Depersonalisations-Derealisationssyndrom [Visual Distortions and Depersonalization-Derealization Syndrome]. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2006;223:279–84.

Sierra M, Medford N, Wyatt G, David AS. Depersonalization disorder and anxiety: a special relationship? Psychiatry Res. 2012;197:123–7.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Medizin und Ärztliche Psychotherapie (DGPM), Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische-Medizin-(DKPM), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN), Deutsche Psychoanalytische Vereinigung (DPV), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verhaltenstherapie (DGVT), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie (DGPs): Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Behandlung des Depersonalisations-Derealisationssyndroms, Version 1.0 September 2014. AWMF Registernummer 051 - 030. Access http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051-030.html . Accessed 1 Feb 2015.

Download references

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Jasmin Schlax for her help with drafting the revisions of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Availability of the data and materials

The authors confirm that, for approved reasons, access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. Due to ethical restrictions, the data cannot be made publicly available (approval of the Ethics Committee of the State Board of Physicians of Rhineland-Palatinate, Mainz, Germany ((837.191.16 (10510)).

Authors’ contributions

MM wrote the first version of the Manuscript; MM, RZ, JW, SW, MEB made the statistical analysis, MM, JA, JW, IR, RT, KW, IT, CS-W, MEB, RZ were involved in the clinical assessment of the patients, all authors contributed substantially to the conception of the study; all authors revised the manuscript critically and all authors gave their approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Board of Physicians of Rhineland-Palatinate, Mainz, Germany ((837.191.16 (10510)). According to the approval of the Ethics Committee, there was no need for written consent because the study analyzed clinical data obtained by clinical standard assessment (i.e., not within the context of an epidemiological or clinical study).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center Mainz, Mainz, Germany

Matthias Michal, Julia Adler, Jörg Wiltink, Iris Reiner, Regine Tschan, Klaus Wölfling, Sabine Weimert, Inka Tuin, Claudia Subic-Wrana, Manfred E. Beutel & Rüdiger Zwerenz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Matthias Michal .

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Additional information about the diagnostic procedure. (DOC 37 kb)

Additional file 2:

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation of the items of the CDS-2, PHQ-9, GAD-7 and Mini-Spin. (DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Michal, M., Adler, J., Wiltink, J. et al. A case series of 223 patients with depersonalization-derealization syndrome. BMC Psychiatry 16 , 203 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0908-4

Download citation

Received : 26 February 2015

Accepted : 20 June 2016

Published : 27 June 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0908-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Depersonalization

- Derealization

- Health care utilization

- Childhood trauma

- Parental history of mental disorders

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- ASH Foundation

- Log in or create an account

- Publications

- Diversity Equity and Inclusion

- Global Initiatives

- Resources for Hematology Fellows

- American Society of Hematology

- Hematopoiesis Case Studies

Case Study: A 78-Year-Old Man With Elevated Leukocytes and Anemia

- Agenda for Nematology Research

- Precision Medicine

- Genome Editing and Gene Therapy

- Immunologic Treatment

- Research Support and Funding

The following case study focuses on finding the optimal treatment for a 78-year-old man. Test your knowledge by reading the question below and making the proper selection.

A 78-year-old man presents with a three-year history of an elevated leukocyte count with recent fatigue and anemia. He has received two red blood cell transfusions in the past two months. His past medical history includes coronary artery disease and hypertension. His physical examination is unremarkable. The patient’s white blood cell (WBC) count is 75,000/uL, hemoglobin is 9.3 g/dL, and platelet count is 71,000/uL with a WBC differential including 60 percent neutrophils, 19 percent lymphocytes, 15 percent monocytes, and 6 percent eosinophils. His bone marrow aspirate shows mild erythroid dysplasia, 1 percent blasts with an increase in monocytes (14 percent) and eosinophils (7 percent). Chromosomal analysis demonstrates 46XY, t(5;12)(q33;p13)[16]; 46,XY[4]. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing for the BCR-ABL translocation and quantitative RT-PCR for the BCR-ABL transcript were both negative. What is the optimal treatment for this patient?

- Decitabine (Dacogen) 20 mg/m 2 daily x five days per month for three months and then re-examine the bone marrow

- Continued observation until further disease progression

- Imatinib (Gleevec) 400 mg once daily

- Standard induction chemotherapy with daunorubicin (50 mg/m 2 daily x three days) and Ara-C (100 mg/m 2 continuous infusion x seven days)

Explanation

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is considered to be a clonal myeloid stem cell disorder. 1-3 In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified CMML as a myelodysplastic-myeloproliferative disease with diagnostic criteria including: 1) persistent peripheral blood (PB) monocyte count >1X109/L; 2) absence of the Philadelphia chromosome; 3) < 20 percent blasts in the PB or bone marrow (BM); and 4) dysplasia in one or more hematopoietic cell lineages. 2,3 The subcategory of CMML with eosinophilia was also established and is characterized by a PB eosinophilia of >1500 cells/uL.

Translocation (5;12)(q31-q33;p12-p13) is a recurring cytogenetic abnormality reported in patients with CMML, in particular those with eosinophilia. 4 The t(5;12) translocation results in the fusion of the transmembrane and tyrosine kinase domains of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-B ( PDGFR-B ) gene on chromosome 5 with the amino-terminal domain of the TEL/ETV6 gene of chromosome 12, a member of the ETS family of transcription factors. 5,6 The resultant aberrant tyrosine kinase activity of this hybrid protein is potentially the transforming event in these cases of CMML. 7-9 The overall incidence of t(5;12) in CMML is unknown but is presumed to be relatively rare. A retrospective analysis by Gunby, et al. demonstrated the translocation in only 1/27 patients with CMML. 10 Others have indicated only 40 to 50 known cases of CMML involving t(5;12) or similar chromosomal abnormalities involving the PDGFR-B loci. 11

Imatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with potent activity against BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia. Imatinib also inhibits a number of additional tyrosine kinases including PDGFRA, PDGFRB, and c-kit, providing the basis for its use in CMML involving the t(5;12) translocation. 12-14 Recently, Han, et al. reviewed 13 cases from the literature of myeloproliferative diseases with evidence of PGDFR-B translocations treated with imatinib. 11 An impressive number of complete responses were noted, encouraging further study of this agent in this CMML subgroup.

Given this patient’s age and absence of blastic transformation, intensive induction chemotherapy regimens such as daunorubicin and cytarabine would not be optimal. Such therapies can lead to significant treatment-related mortality in the elderly. The alternative plan of observation alone, while always an option for patients, would not be preferable for this symptomatic patient who has transfusion dependency and fatigue. Finally, hypomethylating agents, including decitabine have recently been evaluated in patients with CMML. 15,16 Overall response rates of 25 percent to 70 percent have been reported, with complete response rates ranging from 12 percent to greater than 60 percent. Although this is a treatment option, given the identification of the t(5;12) translocation, oral imatinib, which is generally well tolerated even in the elderly, is a rational treatment option for this patient.

In summary, CMML associated with t(5;12) translocation is a relatively rare disorder. Responses to imatinib are variable, but this agent offers a unique treatment alternative in a disease with relatively few curative options in the elderly population. Therefore, identifying this translocation, especially in CMML patients presenting with eosinophilia, should be a priority.

- Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. The chronic myeloid leukaemias: guidelines for distinguishing chronic granulocytic, atypical chronic myeloid, and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Proposals by the French-American-British Cooperative Leukaemia Group . Br J Haematol. 1994;87:746-54.

- Elliott MA. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: WHO defined . Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19:571-93.

- Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms . Blood. 2002;100:2292-302.

- Baranger L, Szapiro N, Gardais J, et al. Translocation t(5;12)(q31-q33;p12-p13): a non-random translocation associated with a myeloid disorder with eosinophilia . Br J Haematol. 1994;88:343-7.

- Golub TR, Barker GF, Lovett M, Gilliland DG. Fusion of PDGF receptor beta to a novel ets-like gene, tel, in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with t(5;12) chromosomal translocation . Cell. 1994;77:307-16.

- Wlodarska I, Mecucci C, Marynen P, et al. TEL gene is involved in myelodysplastic syndromes with either the typical t(5;12)(q33;p13) translocation or its variant t(10;12)(q24;p13) . Blood. 1995;85:2848-52.

- Carroll M, Tomasson MH, Barker GF, et al. The TEL/platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor (PDGF beta R) fusion in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia is a transforming protein that self-associates and activates PDGF beta R kinase-dependent signaling pathways . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14845-50.

- Jousset C, Carron C, Boureux A, et al. A domain of TEL conserved in a subset of ETS proteins defines a specific oligomerization interface essential to the mitogenic properties of the TEL-PDGFR beta oncoprotein . Embo J. 1997;16:69-82.

- Ritchie KA, Aprikyan AA, Bowen-Pope DF, et al. The Tel-PDGFRbeta fusion gene produces a chronic myeloproliferative syndrome in transgenic mice . Leukemia. 1999;13:1790-803.

- Gunby RH, Cazzaniga G, Tassi E, et al. Sensitivity to imatinib but low frequency of the TEL/PDGFRbeta fusion protein in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia . Haematologica. 2003;88:408-15.

- Han X, Medeiros LJ, Abruzzo LV, et al. Chronic myeloproliferative diseases with the t(5;12)(q33;p13): clonal evolution is associated with blast crisis . Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:49-56.

- Magnusson MK, Meade KE, Nakamura R, Barrett J, Dunbar CE. Activity of STI571 in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with a platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor fusion oncogene . Blood. 2002;100:1088-91.

- Carroll M, Ohno-Jones S, Tamura S, et al. CGP 57148, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibits the growth of cells expressing BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL, and TEL-PDGFR fusion proteins . Blood. 1997;90:4947-52.

- Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Mett H, et al. Inhibition of the Abl protein-tyrosine kinase in vitro and in vivo by a 2-phenylaminopyrimidine derivative . Cancer Res. 1996;56:100-4.

- Aribi A, Borthakur G, Ravandi F, et al. Activity of decitabine, a hypomethylating agent, in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia . Cancer. 2007;109:713-7.

- Wijermans PW, Rüter B, Baer MR, et al. Efficacy of decitabine in the treatment of patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) . Leuk Res. 2008;32:587-91.

Additional Resources

- Han X, Medeiros J, et al. Chronic myeloproliferative diseases with the t(5;12)(q33;p13) . American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2006;125(1):49-56.

- Elliot M. Chronic neutrophilic leukemia and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: WHO defined . Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology. 2006;19(3):571-593.

Case study submitted by Dale Bixby, MD, PhD, of the University of Michigan.

American Society of Hematology. (1). Case Study: A 78-Year-Old Man With Elevated Leukocytes and Anemia. Retrieved from https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/male-elevated-leukocytes-and-anemia .

American Society of Hematology. "Case Study: A 78-Year-Old Man With Elevated Leukocytes and Anemia." Hematology.org. https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/male-elevated-leukocytes-and-anemia (label-accessed September 13, 2024).

"American Society of Hematology." Case Study: A 78-Year-Old Man With Elevated Leukocytes and Anemia, 13 Sep. 2024 , https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/male-elevated-leukocytes-and-anemia .

Citation Manager Formats

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Descriptive Research and Case Studies

Learning objectives.

- Explain the importance and uses of descriptive research, especially case studies, in studying abnormal behavior

Types of Research Methods

There are many research methods available to psychologists in their efforts to understand, describe, and explain behavior and the cognitive and biological processes that underlie it. Some methods rely on observational techniques. Other approaches involve interactions between the researcher and the individuals who are being studied—ranging from a series of simple questions; to extensive, in-depth interviews; to well-controlled experiments.

The three main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research. Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive, or qualitative, studies . These studies are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured. In the early stages of research, it might be difficult to form a hypothesis, especially when there is not any existing literature in the area. In these situations designing an experiment would be premature, as the question of interest is not yet clearly defined as a hypothesis. Often a researcher will begin with a non-experimental approach, such as a descriptive study, to gather more information about the topic before designing an experiment or correlational study to address a specific hypothesis. Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research , in which psychologists formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables. Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior. It aims to determine if one variable directly impacts and causes another. Correlational and experimental research both typically use hypothesis testing, whereas descriptive research does not.

Each of these research methods has unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While surveys allow results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While existing records can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control on how or what kind of data was collected.

Correlational research can find a relationship between two variables, but the only way a researcher can claim that the relationship between the variables is cause and effect is to perform an experiment. In experimental research, which will be discussed later, there is a tremendous amount of control over variables of interest. While performing an experiment is a powerful approach, experiments are often conducted in very artificial settings, which calls into question the validity of experimental findings with regard to how they would apply in real-world settings. In addition, many of the questions that psychologists would like to answer cannot be pursued through experimental research because of ethical concerns.

The three main types of descriptive studies are case studies, naturalistic observation, and surveys.

Clinical or Case Studies

Psychologists can use a detailed description of one person or a small group based on careful observation. Case studies are intensive studies of individuals and have commonly been seen as a fruitful way to come up with hypotheses and generate theories. Case studies add descriptive richness. Case studies are also useful for formulating concepts, which are an important aspect of theory construction. Through fine-grained knowledge and description, case studies can fully specify the causal mechanisms in a way that may be harder in a large study.

Sigmund Freud developed many theories from case studies (Anna O., Little Hans, Wolf Man, Dora, etc.). F or example, he conducted a case study of a man, nicknamed “Rat Man,” in which he claimed that this patient had been cured by psychoanalysis. T he nickname derives from the fact that among the patient’s many compulsions, he had an obsession with nightmarish fantasies about rats.

Today, more commonly, case studies reflect an up-close, in-depth, and detailed examination of an individual’s course of treatment. Case studies typically include a complete history of the subject’s background and response to treatment. From the particular client’s experience in therapy, the therapist’s goal is to provide information that may help other therapists who treat similar clients.

Case studies are generally a single-case design, but can also be a multiple-case design, where replication instead of sampling is the criterion for inclusion. Like other research methodologies within psychology, the case study must produce valid and reliable results in order to be useful for the development of future research. Distinct advantages and disadvantages are associated with the case study in psychology.

A commonly described limit of case studies is that they do not lend themselves to generalizability . The other issue is that the case study is subject to the bias of the researcher in terms of how the case is written, and that cases are chosen because they are consistent with the researcher’s preconceived notions, resulting in biased research. Another common problem in case study research is that of reconciling conflicting interpretations of the same case history.