Playing games: advancing research on online and mobile gaming consumption

Internet Research

ISSN : 1066-2243

Article publication date: 9 April 2019

Issue publication date: 9 April 2019

Seo, Y. , Dolan, R. and Buchanan-Oliver, M. (2019), "Playing games: advancing research on online and mobile gaming consumption", Internet Research , Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 289-292. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-04-2019-542

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Emerald Publishing Limited

Introduction

Computer games consistently generate more revenue than the movie and music industries and have become one of the most ubiquitous symbols of popular culture ( Takahashi, 2018 ). Recent technological developments are changing the ways in which consumers are able to engage with computer games as individuals – adult gamers, parents and children ( Christy and Kuncheva, 2018 ) – and as collectives, such as communities, networks and subcultures ( Hamari and Sjöblom, 2017 ; Seo, 2016 ). In particular, with the proliferation of online and mobile technologies, we have witnessed the emergence of newer forms of both computer games themselves (e.g. advertising games (advergames), virtual and augmented reality games and social media games) ( Rauschnabel et al. , 2017 ) and of gaming practices (e.g. serious gaming, hardcore gaming and eSports) ( Seo, 2016 ).

It is, therefore, not surprising that the issues concerning the ways computer games consumption is changing in light of these technological developments have received much attention across diverse disciplines of social sciences, such as marketing (e.g. Seo et al. , 2015 ), information systems (e.g. Liu et al. , 2013 ), media studies (e.g. Giddings, 2016 ) and internet research (e.g. Hamari and Sjöblom, 2017 ). The purpose of this introductory paper to the special issue “Online and mobile gaming” is to chart future research directions that are relevant to a rapidly changing postmodern digital gaming landscape. In this endeavor, this paper first provides an integrative summary of the six articles that comprise this special issue, and then draws the threads together in order to elicit the agenda for future research.

An integrative summary of the special issue

The six articles that were selected for this special issue advance research into online and mobile gaming in several ways. The opening article by Pappas, Mikalef, Giannakos and Kourouthanassis draws attention to the complex ecosystem of mobile applications in which multiple factors influence consumer behavior in mobile games. Pappas and his colleagues shed light on how price value, game content quality, positive and negative emotions, gender, and gameplay time interact with one another to predict the intention to download mobile games. This study offers useful insights by demonstrating how fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis methodology can be applied to advance research into computer games consumption.

The study by Bae, Kim, Kim and Koo addresses the digital virtual consumption that occurs within computer games. This second paper explores the relationship between in-game items and mood management to determine the affective value of purchasing in-game items. The findings reveal that game users manage their levels of arousal and mood valence through the use of in-game purchases, suggesting that stressed users are more likely to purchase decorative items, whereas bored users tend to purchase functional items. This study offers an informative perspective of how mood management and selective exposure theories can be applied to understand the in-game purchases. Continuing this theme, the third study by Bae, Park and Koo investigates the effect of perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Park and colleagues extend previous research by identifying important motivational mechanisms, such as self-esteem and compassion, which link CSR initiative perceptions with the intentions to purchase in-game items.

The fourth and fifth studies of this special issue draw our attention to the use of avatars and game characters. Liao, Cheng and Teng use social identity and flow theories to construct a novel model that explains how avatar attractiveness and customization impact loyalty among online game consumers. In the fifth study, Choi explores the importance of game character characteristics being congruent with product types in order to make advergames more persuasive.

The final study by Lee and Ko reviews the predictors of game addiction based on loneliness, motivation and inter-personal competence. The findings of these authors suggest that regulatory focus mediates the effect of loneliness on online game addiction, and that inter-personal competence significantly buffers the indirect effect of loneliness on online game addiction. This study advances our knowledge about online game addiction through an investigation of the important role played by loneliness.

Future directions for research

Taken together, our introductory commentary and the six empirical studies that make up this special issue deepen and broaden the current understanding of how online and mobile technologies augment the consumption of computer games. In this final section of our paper, we outline potential directions for future research.

First, this special issue highlights that computer games consumption is a diverse interdisciplinary phenomenon, where important issues range from establishing the factors that determine the adoption of particular computer games to what consumers do within these games; from whether computer games enhance consumer well-being (e.g. Howes et al. , 2017 ), to whether they engender addiction (e.g. Frölich et al. , 2016 ); and from establishing how computer gaming experiences are influenced by internal psychological mechanisms to querying the effects of broader social aspects of consumer lives on computer games consumption ( Kowert et al. , 2015 ). Informed by these findings, we assert that as computer games consumption becomes more complex and interactive, incorporating more technology brought about by the proliferation of online and mobile gaming, it is important that our theorizing follows by tracking the mutual imbrication of consumers, play, technology, culture, well-being and other salient issues.

Computer games consumption is a phenomenon of global significance, which is reflected by the international interest that we have received for this special issue. This prompts us to consider similarities and differences in the ways that computer games are consumed across cultures ( Elmezeny and Wimmer, 2018 ). Many computer games themselves now foster intercultural, multicultural and transcultural experiences ( Cruz et al. , 2018 ) by enabling consumers from different countries and regions to connect and build relationships within the shared virtual space. How do such experiences shape the consumption of computer games? This gap in the literature has been previously noted ( Seo et al. , 2015 ), but it has not been either sufficiently detailed or theorised. Future studies should explore the role of various transcultural experiences and practices within online and mobile games consumption.

Finally, one increasingly promising area for future research is the rise of virtual reality (VR) applications. Although the earliest references to VR date back to the 1990s (e.g. Gigante, 1993 ), it has been only recently that technological developments have allowed VR to evolve from a niche technology into an everyday phenomenon that is readily available to consumers ( Lamkin, 2017 ; Oleksy and Wnuk, 2017 ). Given that VR is an experientially distinct medium, how will it augment computer games consumption experiences and practices? Will it foster more diverse applications of computer games across various aspects of consumer lives (e.g. Tussyadiah et al. , 2018 ), or will it increase computer games addiction (e.g. Chou and Ting, 2003 )? What are the current and future intersections between VR technology, online and mobile games, and how are they likely to develop and affect consumers? We envision that these and many other questions related to the application and proliferation of VR technology in computer games consumption will be an exceptionally fruitful area for future research.

In summary, we hope that this paper and the special issue, with its emphasis on online and mobile gaming, will offer new insights for researchers and practitioners who are interested in the advancement of research on computer games consumption.

Chou , T.J. and Ting , C.C. ( 2003 ), “ The role of flow experience in cyber-game addiction ”, CyberPsychology and Behavior , Vol. 6 No. 6 , pp. 663 - 675 .

Christy , T. and Kuncheva , L.I. ( 2018 ), “ Technological advancements in affective gaming: a historical survey ”, GSTF Journal on Computing , Vol. 3 No. 4 , pp. 32 - 41 .

Cruz , A.G.B. , Seo , Y. and Buchanan-Oliver , M. ( 2018 ), “ Religion as a field of transcultural practices in multicultural marketplaces ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 91 , pp. 317 - 325 .

Elmezeny , A. and Wimmer , J. ( 2018 ), “ Games without frontiers: a framework for analyzing digital game cultures comparatively ”, Media and Communication , Vol. 6 No. 2 , pp. 80 - 89 .

Frölich , J. , Lehmkuhl , G. , Orawa , H. , Bromba , M. , Wolf , K. and Görtz-Dorten , A. ( 2016 ), “ Computer game misuse and addiction of adolescents in a clinically referred study sample ”, Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 55 , pp. 9 - 15 .

Giddings , S. ( 2016 ), “ Pokémon Go as distributed imagination ”, Mobile Media and Communication , Vol. 5 No. 1 , pp. 59 - 62 .

Gigante , M.A. ( 1993 ), “ Virtual reality: definitions, history and applications ”, in Earnshaw , R.A. (Ed.), Virtual Reality Systems , Academic Press , New York, NY , pp. 3 - 14 .

Hamari , J. and Sjöblom , M. ( 2017 ), “ What is eSports and why do people watch it ”, Internet Research , Vol. 27 No. 2 , pp. 211 - 232 .

Howes , S.C. , Charles , D.K. , Marley , J. , Pedlow , K. and McDonough , S.M. ( 2017 ), “ Gaming for health: systematic review and meta-analysis of the physical and cognitive effects of active computer gaming in older adults ”, Physical Therapy , Vol. 97 No. 12 , pp. 1122 - 1137 .

Kowert , R. , Vogelgesang , J. , Festl , R. and Quandt , T. ( 2015 ), “ Psychosocial causes and consequences of online video game play ”, Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 45 , pp. 51 - 58 .

Lamkin , P. ( 2017 ), “ Virtual reality headset sales hit 1 million ”, available at: www.forbes.com/sites/paullamkin/2017/11/30/virtual-reality-headset-sales-hit-1-million/#241697c42b61/ (accessed October 4, 2018 ).

Liu , D. , Li , X. and Santhanam , R. ( 2013 ), “ Digital games and beyond: what happens when players compete ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 37 No. 1 , pp. 111 - 124 .

Oleksy , T. and Wnuk , A. ( 2017 ), “ Catch them all and increase your place attachment! The role of location-based augmented reality games in changing people–place relations ”, Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 76 , pp. 3 - 8 .

Rauschnabel , P.A. , Rossmann , A. and tom Dieck , M.C. ( 2017 ), “ An adoption framework for mobile augmented reality games: the case of Pokémon Go ”, Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 76 , pp. 276 - 286 .

Seo , Y. ( 2016 ), “ Professionalized consumption and identity transformations in the field of eSports ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 69 No. 1 , pp. 264 - 272 .

Seo , Y. , Buchanan‐Oliver , M. and Fam , K.S. ( 2015 ), “ Advancing research on computer game consumption: a future research agenda ”, Journal of Consumer Behaviour , Vol. 14 No. 6 , pp. 353 - 356 .

Takahashi , D. ( 2018 ), “ Newzoo: games market expected to hit $180.1 billion in revenues in 2021 ”, available at: https://venturebeat.com/2018/04/30/newzoo-global-games-expected-to-hit-180-1-billion-in-revenues-2021/ (accessed October 4, 2018 ).

Tussyadiah , I.P. , Wang , D. , Jung , T.H. and tom Dieck , M.C. ( 2018 ), “ Virtual reality, presence and attitude change: empirical evidence from tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 66 , pp. 140 - 154 .

Acknowledgements

The guest editors would like to offer special thanks to the Editor of Internet Research , Christy Cheung, for supporting the publication of this special issue. The guest editors would also like to thank all of the authors who contributed to this research for the “Online and mobile gaming” special issue. Finally, the guest editors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of reviewers, who generously spent their time in helping to review submissions: Luke Butcher, Curtin University, Australia; Hsiu-Hua Chang, Feng Chia University, Taiwan; I-Cheng Chang, National Dong Hwa University, Taiwan; Chi-Wen Chen, California State University, USA; Zifei Fay Chen, University of San Francisco, USA; Sujeong Choi, Chonnam National University, Korea; Diego Costa Pinto, New University of Lisbon, Portugal; Angela Cruz, Monash University, Australia; Robert Davis, Massey University, New Zealand; Julia Fehrer, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Tony Garry, University of Otago, New Zealand; Tracy Harwood, De Montfort University, UK; Mu Hu, Beihang University, China; Tseng-Lung Huang, Yuan Ze University, Taiwan; Kun-Huang Huang, Feng Chia University, Taiwan; Chelsea Hughes, Virginia Commonwealth University, USA; Euejung Hwang, Otago University, New Zealand; Sang-Uk Jung, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Korea; Kacy Kim, Bryant University, USA; Dong-Mo Koo, Kyungpook National University, Korea; Jun Bum Kwon, University of New South Wales, Australia; Chun-Chia Lee, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan; Jacob Chaeho Lee, Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Korea; Loic Li, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Marcel Martončik, University of Presov, Slovakia; Mike Molesworth, University of Reading, UK; Gavin Northey, University of Auckland, New Zealand; James Richard, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand; Ryan Rogers, University of Pennsylvania, USA; Felix Septianto, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Zhen Shao, Harbin Institute of Technology, China; Kai-Shuan Shen, Fo Guang University, Taiwan; Jungmin Son, Chungnam National University; Korea; Yang Sun, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, China; Eva van Reijmersdal, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands; Ekant Veer, University of Canterbury, New Zealand; John Velez, Indiana University, USA; Wei-Tsong Wang, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan; Ya-Ling Wu, Tamkang University, Taiwan; Sheau-Fen Yap, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand; and Sukki Yoon, Bryant University, USA.

Corresponding author

About the authors.

Yuri Seo is Senior Lecturer at the University of Auckland of Business School, New Zealand. His research interests include digital technology and consumption, cultural branding and multicultural marketplaces.

Rebecca Dolan is Lecturer at the University of Adelaide School of Business, Australia. Her research focuses on understanding, facilitating and optimizing customer relationships, engagement, and online communication strategies. She has a specific interest in the role that digital and social media play in the modern marketing communications environment.

Margo Buchanan-Oliver is Professor in the Department of Marketing and the Co-Director of the Centre of Digital Enterprise (CODE) at the University of Auckland Business School. Her research concerns interdisciplinary consumption discourse and practice, particularly that occurring at the intersection of the digital and physical worlds.

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 December 2020

Effect of internet use and electronic game-play on academic performance of Australian children

- Md Irteja Islam 1 , 2 ,

- Raaj Kishore Biswas 3 &

- Rasheda Khanam 1

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 21727 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

70k Accesses

23 Citations

32 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Risk factors

This study examined the association of internet use, and electronic game-play with academic performance respectively on weekdays and weekends in Australian children. It also assessed whether addiction tendency to internet and game-play is associated with academic performance. Overall, 1704 children of 11–17-year-olds from young minds matter (YMM), a cross-sectional nationwide survey, were analysed. The generalized linear regression models adjusted for survey weights were applied to investigate the association between internet use, and electronic-gaming with academic performance (measured by NAPLAN–National standard score). About 70% of the sample spent > 2 h/day using the internet and nearly 30% played electronic-games for > 2 h/day. Internet users during weekdays (> 4 h/day) were less likely to get higher scores in reading and numeracy, and internet use on weekends (> 2–4 h/day) was positively associated with academic performance. In contrast, 16% of electronic gamers were more likely to get better reading scores on weekdays compared to those who did not. Addiction tendency to internet and electronic-gaming is found to be adversely associated with academic achievement. Further, results indicated the need for parental monitoring and/or self-regulation to limit the timing and duration of internet use/electronic-gaming to overcome the detrimental effects of internet use and electronic game-play on academic achievement.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of digital media on children’s intelligence while controlling for genetic differences in cognition and socioeconomic background

Bruno Sauce, Magnus Liebherr, … Torkel Klingberg

Adaption and implementation of the engage programme within the early childhood curriculum

Dione Healey, Barry Milne & Matthew Healey

The role of game genres and gamers’ communication networks in perceived learning

Chang Won Jung

Introduction

Over the past two decades, with the proliferation of high-tech devices (e.g. Smartphone, tablets and computers), both the internet and electronic games have become increasingly popular with people of all ages, but particularly with children and adolescents 1 , 2 , 3 . Recent estimates have shown that one in three under-18-year-olds across the world uses the Internet, and 75% of adolescents play electronic games daily in developed countries 4 , 5 , 6 . Studies in the United States reported that adolescents are occupied with over 11 h a day with modern electronic media such as computer/Internet and electronic games, which is more than they spend in school or with friends 7 , 8 . In Australia, it is reported that about 98% of children aged 15–17 years are among Internet users and 98% of adolescents play electronic games, which is significantly higher than the USA and Europe 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 .

In recent times, the Internet and electronic games have been regarded as important, not just for better results at school, but also for self-expression, sociability, creativity and entertainment for children and adolescents 13 , 14 . For instance, 88% of 12–17 year-olds in the USA considered the Internet as a useful mechanism for making progress in school 15 , and similarly, electronic gaming in children and adolescents may assist in developing skills such as decision-making, smart-thinking and coordination 3 , 15 .

On the other hand, evidence points to the fact that the use of the Internet and electronic games is found to have detrimental effects such as reduced sleeping time, behavioural problems (e.g. low self-esteem, anxiety, depression), attention problems and poor academic performance in adolescents 1 , 5 , 12 , 16 . In addition, excessive Internet usage and increased electronic gaming are found to be addictive and may cause serious functional impairment in the daily life of children and adolescents 1 , 12 , 13 , 16 . For example, the AU Kids Online survey 17 reported that 50% of Australian children were more likely to experience behavioural problems associated with Internet use compared to children from 25 European countries (29%) surveyed in the EU Kids Online study 18 , which is alarming 12 . These mixed results require an urgent need of understanding the effect of the Internet use and electronic gaming on the development of children and adolescents, particularly on their academic performance.

Despite many international studies and a smaller number in Australia 12 , several systematic limitations remain in the existing literature, particularly regarding the association of academic performance with the use of Internet and electronic games in children and adolescents 13 , 16 , 19 . First, the majority of the earlier studies have either relied on school grades or children’s self assessments—which contain an innate subjectivity by the assessor; and have not considered the standardized tests of academic performance 16 , 20 , 21 , 22 . Second, most previous studies have tested the hypothesis in the school-based settings instead of canvassing the whole community, and cannot therefore adjust for sociodemographic confounders 9 , 16 . Third, most studies have been typically limited to smaller sample sizes, which might have reduced the reliability of the results 9 , 16 , 23 .

By considering these issues, this study aimed to investigate the association of internet usage and electronic gaming on a standardized test of academic performance—NAPLAN (The National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy) among Australian adolescents aged 11–17 years using nationally representative data from the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing—Young Minds Matter (YMM). It is hypothesized that the findings of this study will provide a population-wide, contextual view of excessive Internet use and electronic games played separately on weekdays and weekends by Australian adolescents, which may be beneficial for evidence-based policies.

Subject demographics

Respondents who attended gave NAPLAN in 2008 (N = 4) and 2009 (N = 29) were removed from the sample due to smaller sample size, as later years (2010–2015) had over 100 samples yearly. The NAPLAN scores from 2008 might not align with a survey conducted in 2013. Further missing cases were deleted with the assumption that data were missing at random for unbiased estimates, which is common for large-scale surveys 24 . From the initial survey of 2967 samples, 1704 adolescents were sampled for this study.

The sample characteristics were displayed in Table 1 . For example, distribution of daily average internet use was checked, showing that over 50% of the sampled adolescents spent 2–4 h on internet (Table 1 ). Although all respondents in the survey used internet, nearly 21% of them did not play any electronic games in a day and almost one in every three (33%) adolescents played electronic games beyond the recommended time of 2 h per day. Girls had more addictive tendency to internet/game-play in compare to boys.

The mean scores for the three NAPLAN tests scores (reading, writing and numeracy) ranged from 520 to 600. A gradual decline in average NAPLAN tests scores (reading, writing and numeracy) scores were observed for internet use over 4 h during weekdays, and over 3 h during weekends (Table 2 ). Table 2 also shows that adolescents who played no electronic games at all have better scores in writing compared to those who play electronic games. Moreover, Table 2 shows no particular pattern between time spent on gaming and NAPLAN reading and numeracy scores. Among the survey samples, 308 adolescents were below the national standard average.

Internet use and academic performance

Our results show that internet (non-academic use) use during weekdays, especially more than 4 h, is negatively associated with academic performance (Table 3 ). For internet use during weekdays, all three models showed a significant negative association between time spent on internet and NAPLAN reading and numeracy scores. For example, in Model 1, adolescents who spent over 4 h on internet during weekdays are 15% and 17% less likely to get higher reading and numeracy scores respectively compared to those who spend less than 2 h. Similar results were found in Model 2 and 3 (Table 3 ), when we adjusted other confounders. The variable addiction tendency to internet was found to be negatively associated with NAPLAN results. The adolescents who had internet addiction were 17% less and 14% less likely to score higher in reading and numeracy respectively than those without such problematic behaviour.

Internet use during weekends showed a positive association with academic performance (Table 4 ). For example, Model 1 in Table 4 shows that internet use during weekends was significant for reading, writing and national standard scores. Youths who spend around 2–4 h and over 4 h on the internet during weekends were 21% and 15% more likely to get a higher reading scores respectively compared to those who spend less than 2 h (Model 1, Table 4 ). Similarly, in model 3, where the internet addiction of adolescents was adjusted, adolescents who spent 2–4 h on internet were 1.59 times more likely to score above the national standard. All three models of Table 4 confirmed that adolescents who spent 2–4 h on the internet during weekends are more likely to achieve better reading and writing scores and be at or above national standard compared to those who used the internet for less than 2 h. Numeracy scores were unlikely to be affected by internet use. The results obtained from Model 3 should be treated as robust, as this is the most comprehensive model that accounts for unobserved characteristics. The addiction tendency to internet/game-play variable showed a negative association with academic performance, but this is only significant for numeracy scores.

Electronic gaming and academic performance

Time spent on electronic gaming during weekdays had no effect on the academic performance of writing and language but had significant association with reading scores (Model 2, Table 5 ). Model 2 of Table 5 shows that adolescents who spent 1–2 h on gaming during weekdays were 13% more likely to get higher reading scores compared to those who did not play at all. It was an interesting result that while electronic gaming during weekdays tended to show a positive effect on reading scores, internet use during weekdays showed a negative effect. Addiction tendency to internet/game-play had a negative effect; the adolescents who were addicted to the internet were 14% less likely to score more highly in reading than those without any such behaviour.

All three models from Table 6 confirm that time spent on electronic gaming over 2 h during weekends had a positive effect on readings scores. For example, the results of Model 3 (Table 6 ) showed that adolescents who spent more than 2 h on electronic gaming during weekdays were 16% more likely to have better reading scores compared to adolescents who did not play games at all. Playing electronic games during weekends was not found to be statistically significant for writing and numeracy scores and national standard scores, although the odds ratios were positive. The results from all tables confirm that addiction tendency to internet/gaming is negatively associated with academic performance, although the variable is not always statistically significant.

Building on past research on the effect of the internet use and electronic gaming in adolescents, this study examined whether Internet use and playing electronic games were associated with academic performance (i.e. reading, writing and numeracy) using a standardized test of academic performance (i.e. NAPLAN) in a nationally representative dataset in Australia. The findings of this study question the conventional belief 9 , 25 that academic performance is negatively associated with internet use and electronic games, particularly when the internet is used for non-academic purpose.

In the current hi-tech world, many developed countries (e.g. the USA, Canada and Australia) have recommended that 5–17 year-olds limit electronic media (e.g. internet, electronic games) to 2 h per day for entertainment purposes, with concerns about the possible negative consequences of excessive use of electronic media 14 , 26 . However, previous research has often reported that children and adolescents spent more than the recommended time 26 . The present study also found similar results, that is, that about 70% of the sampled adolescents aged 11–17 spent more than 2 h per day on the Internet and nearly 30% spent more than 2-h on electronic gaming in a day. This could be attributed to the increased availability of computers/smart-phones and the internet among under-18s 12 . For instance, 97% of Australian households with children aged less than 15 years accessed internet at home in 2016–2017 10 ; as a result, policymakers recommended that parents restrict access to screens (e.g. Internet and electronic games) in children’s bedrooms, monitor children using screens, share screen hours with their children, and to act as role models by reducing their own screen time 14 .

This research has drawn attention to the fact that the average time spent using the internet, which is often more than 4 h during weekdays tends to be negatively associated with academic performance, especially a lower reading and numeracy score, while internet use of more than 2 h during weekends is positively associated with academic performance, particularly having a better reading and writing score and above national standard score. By dividing internet use and gaming by weekdays and weekends, this study find an answer to the mixed evidence found in previous literature 9 . The results of this study clearly show that the non-academic use of internet during weekdays, particularly, spending more than 4 h on internet is harmful for academic performance, whereas, internet use on the weekends is likely to incur a positive effect on academic performance. This result is consistent with a USA study that reported that internet use is positively associated with improved reading skills and higher scores on standardized tests 13 , 27 . It is also reported in the literature that academic performance is better among moderate users of the internet compared to non-users or high level users 13 , 27 , which was in line with the findings of this study. This may be due to the fact that the internet is predominantly a text-based format in which the internet users need to type and read to access most websites effectively 13 . The results of this study indicated that internet use is not harmful to academic performance if it is used moderately, especially, if ensuring very limited use on weekdays. The results of this study further confirmed that timing (weekdays or weekends) of internet use is a factor that needs to be considered.

Regarding electronic gaming, interestingly, the study found that the average time of gaming either in weekdays or weekends is positively associated with academic performance especially for reading scores. These results contradicted previous literatures 1 , 13 , 19 , 27 that have reported negative correlation between electronic games and educational performance in high-school children. The results of this study were consistent with studies conducted in the USA, Europe and other countries that claimed a positive correlation between gaming and academic performance, especially in numeracy and reading skills 28 , 29 . This is may be due to the fact that the instructions for playing most of the electronic games are text-heavy and many electronic games require gamers to solve puzzles 9 , 30 . The literature also found that playing electronic games develops cognitive skills (e.g. mental rotation abilities, dexterity), which can be attributable to better academic achievement 31 , 32 .

Consistent with previous research findings 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , the study also found that adolescents who had addiction tendency to internet usage and/or electronic gaming were less likely to achieve higher scores in reading and numeracy compared to those who had not problematic behaviour. Addiction tendency to Internet/gaming among adolescents was found to be negatively associated with overall academic performance compared to those who were not having addiction tendency, although the variables were not always statistically significant. This is mainly because adolescents’ skipped school and missed classes and tuitions, and provide less effort to do homework due to addictive internet usage and electronic gaming 19 , 35 . The results of this study indicated that parental monitoring and/ or self-regulation (by the users) regarding the timing and intensity of internet use/gaming are essential to outweigh any negative effect of internet use and gaming on academic performance.

Although the present study uses a large nationally representative sample and advances prior research on the academic performance among adolescents who reported using the internet and playing electronic games, the findings of this study also have some limitations that need to be addressed. Firstly, adolescents who reported on the internet use and electronic games relied on self-reported child data without any screening tests or any external validation and thus, results may be overestimated or underestimated. Second, the study primarily addresses the internet use and electronic games as distinct behaviours, as the YMM survey gathered information only on the amount of time spent on internet use and electronic gaming, and included only a few questions related to addiction due to resources and time constraints and did not provide enough information to medically diagnose internet/gaming addiction. Finally, the cross-sectional research design of the data outlawed evaluation of causality and temporality of the observed association of internet use and electronic gaming with the academic performance in adolescents.

This study found that the average time spent on the internet on weekends and electronic gaming (both in weekdays and weekends) is positively associated with academic performance (measured by NAPLAN) of Australian adolescents. However, it confirmed a negative association between addiction tendency (internet use or electronic gaming) and academic performance; nonetheless, most of the adolescents used the internet and played electronic games more than the recommended 2-h limit per day. The study also revealed that further research is required on the development and implementation of interventions aimed at improving parental monitoring and fostering users’ self-regulation to restrict the daily usage of the internet and/or electronic games.

Data description

Young minds matter (YMM) was an Australian nationwide cross-sectional survey, on children aged 4–17 years conducted in 2013–2014 37 . Out of the initial 76,606 households approached, a total of 6,310 parents/caregivers (eligible household response rate 55%) of 4–17 year-old children completed a structured questionnaire via face to face interview and 2967 children aged 11–17 years (eligible children response rate 89%) completed a computer-based self-reported questionnaire privately at home 37 .

Area based sampling was used for the survey. A total of 225 Statistical Area 1 (defined by Australian Bureau of Statistics) areas were selected based on the 2011 Census of Population and Housing. They were stratified by state/territory and by metropolitan versus non-metropolitan (rural/regional) to ensure proportional representation of geographic areas across Australia 38 . However, a small number of samples were excluded, based on most remote areas, homeless children, institutional care and children living in households where interviews could not be conducted in English. The details of the survey and methodology used in the survey can be found in Lawrence et al. 37 .

Following informed consent (both written and verbal) from the primary carers (parents/caregivers), information on the National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) of the children and adolescents were also added to the YMM dataset. The YMM survey is ethically approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia and by the Australian Government Department of Health. In addition, the authors of this study obtained a written approval from Australian Data Archive (ADA) Dataverse to access the YMM dataset. All the researches were done in accordance with relevant ADA Dataverse guidelines and policy/regulations in using YMM datasets.

Outcome variables

The NAPLAN, conducted annually since 2008, is a nationwide standardized test of academic performance for all Australian students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 to assess their skills in reading, writing numeracy, grammar and spelling 39 , 40 . NAPLAN scores from 2010 to 2015, reported by YMM, were used as outcome variables in the models; while NAPLAN data of 2008 (N = 4) and 2009 (N = 29) were excluded for this study in order to reduce the time lag between YMM survey and the NAPLAN test. The NAPLAN gives point-in-time standardized scores, which provide the scope to compare children’s academic performance over time 40 , 41 . The NAPLAN tests are one component of the evaluation and grading phase of each school, and do not substitute for the comprehensive, consistent evaluations provided by teachers on the performance of each student 39 , 41 . All four domains—reading, writing, numeracy and language conventions (grammar and spelling) are in continuous scales in the dataset. The scores are given based on a series of tests; details can be found in 42 . The current study uses only reading, writing and numeracy scores to measure academic performance.

In this study, the National standard score is a combination of three variables: whether the student meets the national standard in reading, writing and numeracy. Based on national average score, a binary outcome variable is also generated. One category is ‘below standard’ if a child scores at least one standard deviation (one below scores) from the national standard in reading, writing and numeracy, and the rest is ‘at/above standard’.

Independent variables

Internet use and electronic gaming.

In the YMM survey, owing to the scope of the survey itself, an extensive set of questions about internet usage and electronic gaming could not be included. Internet usage omitted the time spent in academic purposes and/or related activities. Playing electronic games included playing games on a gaming console (e.g. PlayStation, Xbox, or similar console ) online or using a computer, or mobile phone, or a handled device 12 . The primary independent covariates were average internet use per day and average electronic game-play in hours per day. A combination of hours on weekdays and weekends was separately used in the models. These variables were based on a self-assessed questionnaire where the youths were asked questions regarding daily time spent on the Internet and electronic game-play, specifically on either weekends or weekdays. Since, internet use/game-play for a maximum of 2 h/day is recommended for children and adolescents aged between 5 and 17 years in many developed countries including Australia 14 , 26 ; therefore, to be consistent with the recommended time we preferred to categorize both the time variables of internet use and gaming into three groups with an interval of 2 h each. Internet use was categorized into three groups: (a) ≤ 2 h), (b) 2–4 h, and (c) > 4 h. Similar questions were asked for game-play h. The sample distribution for electronic game-play was skewed; therefore, this variable was categorized into three groups: (a) no game-play (0 h), (b) 1–2 h, and (c) > 2 h.

Other covariates

Family structure and several sociodemographic variables were used in the models to adjust for the differences in individual characteristics, parental inputs and tastes, household characteristics and place of residence. Individual characteristics included age (continuous) and sex of the child (boys, girls) and addiction tendency to internet use and/or game-play of the adolescent. Addiction tendency to internet/game-play was a binary independent variable. It was a combination of five behavioural questions relating to: whether the respondent avoided eating/sleeping due to internet use or game-play; feels bothered when s/he cannot access internet or play electronic games; keeps using internet or playing electronic games even when s/he is not really interested; spends less time with family/friends or on school works due to internet use or game-play; and unsuccessfully tries to spend less time on the internet or playing electronic games. There were four options for each question: never/almost never; not very often; fairly often; and very often. A binary covariate was simulated, where if any four out of five behaviours were reported as for example, fairly often or very often, then it was considered that the respondent had addictive tendency.

Household characteristics included household income (low, medium, high), family type (original, step, blended, sole parent/primary carer, other) 43 and remoteness (major cities, inner regional, outer regional, remote/very remote). Parental inputs and taste included education of primary carer (bachelor, diploma, year 10/11), primary carer’s likelihood of serious mental illness (K6 score -likely; not likely); primary carer’s smoking status (no, yes); and risk of alcoholic related harm by the primary carer (risky, none).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the sample and distributions of the outcome variables were initially assessed. Based on these distributions, the categorization of outcome variables was conducted, as mentioned above. For formal analysis, generalized linear regression models (GLMs) 44 were used, adjusting for the survey weights, which allowed for generalization of the findings. As NAPLAN scores of three areas—reading, writing and numeracy—were continuous variables, linear models were fitted to daily average internet time and electronic game play time. The scores were standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1) for model fitness. The binary logistic model was fitted for the dichotomized national standard outcome variable. Separate models were estimated for internet and electronic gaming on weekends and weekdays.

We estimated three different models, where models varied based on covariates used to adjust the GLMs. Model 1 was adjusted for common sociodemographic factors including age and sex of the child, household income, education of primary carer’s and family type 43 . However, the results of this model did not account for some unobserved household characteristics (e.g. taste, preferences) that are unobserved to the researcher and are arguably correlated with potential outcomes. The effects of unobserved characteristics were reduced by using a comprehensive set of observable characteristics 45 , 46 that were available in YMM data. The issue of unobserved characteristics was addressed by estimating two additional models that include variables by including household characteristics such as parental taste, preference and inputs, and child characteristics in the model. In addition to the variables in Model 1, Model 2 included remoteness, primary carer’s mental health status, smoking status and risk of alcoholic related harm by the primary carer. Model 3 further included internet/game addiction of the adolescent in addition to all the covariates in Model 2. Model 3 was expected to account for a child’s level of unobserved characteristics as the children who were addicted to internet/games were different from others. The model will further show how academic performance is affected by internet/game addiction. The correlation among the variables ‘internet/game addiction’ and ‘internet use’ and ‘gaming’ (during weekdays and weekends) were also assessed, and they were less than 0.5. Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), which was under 5 for all models, suggesting no multicollinearity 47 .

p value below the threshold of 0.05 was considered the threshold of significance. All analysis was conducted in R (version 3.6.1). R-package survey (version 3.37) was used for modelling which is suited for complex survey samples 48 .

Data availability

The authors declare that they do not have permission to share dataset. However, the datasets of Young Minds Matter (YMM) survey data is available at the Australian Data Archive (ADA) Dataverse on request ( https://doi.org/10.4225/87/LCVEU3 ).

Wang, C. -W., Chan, C. L., Mak, K. -K., Ho, S. -Y., Wong, P. W. & Ho, R. T. Prevalence and correlates of video and Internet gaming addiction among Hong Kong adolescents: a pilot study. Sci. World J . 2014 (2014).

Anderson, E. L., Steen, E. & Stavropoulos, V. Internet use and problematic internet use: a systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 22 , 430–454 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Oliveira, M. P. MTd. et al. Use of internet and electronic games by adolescents at high social risk. Trends Psychol. 25 , 1167–1183 (2017).

Google Scholar

UNICEF. Children in a digital world. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2017)

King, D. L. et al. The impact of prolonged violent video-gaming on adolescent sleep: an experimental study. J. Sleep Res. 22 , 137–143 (2013).

Byrne, J. & Burton, P. Children as Internet users: how can evidence better inform policy debate?. J. Cyber Policy. 2 , 39–52 (2017).

Council, O. Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 132 , 958 (2013).

Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., Von Gontard, A. & Popow, C. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 60 , 645–659 (2018).

Posso, A. Internet usage and educational outcomes among 15-year old Australian students. Int J Commun 10 , 26 (2016).

ABS. 8146.0—Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2016–2017 (2018).

Brand, J. E. Digital Australia 2018 (Interactive Games & Entertainment Association (IGEA), Eveleigh, 2017).

Rikkers, W., Lawrence, D., Hafekost, J. & Zubrick, S. R. Internet use and electronic gaming by children and adolescents with emotional and behavioural problems in Australia–results from the second Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. BMC Public Health 16 , 399 (2016).

Jackson, L. A., Von Eye, A., Witt, E. A., Zhao, Y. & Fitzgerald, H. E. A longitudinal study of the effects of Internet use and videogame playing on academic performance and the roles of gender, race and income in these relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27 , 228–239 (2011).

Yu, M. & Baxter, J. Australian children’s screen time and participation in extracurricular activities. Ann. Stat. Rep. 2016 , 99 (2015).

Rainie, L. & Horrigan, J. A decade of adoption: How the Internet has woven itself into American life. Pew Internet and American Life Project . 25 (2005).

Drummond, A. & Sauer, J. D. Video-games do not negatively impact adolescent academic performance in science, mathematics or reading. PLoS ONE 9 , e87943 (2014).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Green, L., Olafsson, K., Brady, D. & Smahel, D. Excessive Internet use among Australian children (2012).

Livingstone, S. EU kids online. The international encyclopedia of media literacy . 1–17 (2019).

Wright, J. The effects of video game play on academic performance. Mod. Psychol. Stud. 17 , 6 (2011).

Gentile, D. A., Lynch, P. J., Linder, J. R. & Walsh, D. A. The effects of violent video game habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors, and school performance. J. Adolesc. 27 , 5–22 (2004).

Rosenthal, R. & Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev. 3 , 16–20 (1968).

Willoughby, T. A short-term longitudinal study of Internet and computer game use by adolescent boys and girls: prevalence, frequency of use, and psychosocial predictors. Dev. Psychol. 44 , 195 (2008).

Weis, R. & Cerankosky, B. C. Effects of video-game ownership on young boys’ academic and behavioral functioning: a randomized, controlled study. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 463–470 (2010).

Howell, D. C. The treatment of missing data. The Sage handbook of social science methodology . 208–224 (2007).

Terry, M. and Malik, A. Video gaming as a factor that affects academic performance in grade nine. Online Submission (2018).

Houghton, S. et al. Virtually impossible: limiting Australian children and adolescents daily screen based media use. BMC Public Health. 15 , 5 (2015).

Jackson, L. A., Von Eye, A., Fitzgerald, H. E., Witt, E. A. & Zhao, Y. Internet use, videogame playing and cell phone use as predictors of children’s body mass index (BMI), body weight, academic performance, and social and overall self-esteem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27 , 599–604 (2011).

Bowers, A. J. & Berland, M. Does recreational computer use affect high school achievement?. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 61 , 51–69 (2013).

Wittwer, J. & Senkbeil, M. Is students’ computer use at home related to their mathematical performance at school?. Comput. Educ. 50 , 1558–1571 (2008).

Jackson, L. A. et al. Does home internet use influence the academic performance of low-income children?. Dev. Psychol. 42 , 429 (2006).

Barlett, C. P., Anderson, C. A. & Swing, E. L. Video game effects—confirmed, suspected, and speculative: a review of the evidence. Simul. Gaming 40 , 377–403 (2009).

Suziedelyte, A. Can video games affect children's cognitive and non-cognitive skills? UNSW Australian School of Business Research Paper (2012).

Chiu, S.-I., Lee, J.-Z. & Huang, D.-H. Video game addiction in children and teenagers in Taiwan. CyberPsychol. Behav. 7 , 571–581 (2004).

Skoric, M. M., Teo, L. L. C. & Neo, R. L. Children and video games: addiction, engagement, and scholastic achievement. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 12 , 567–572 (2009).

Leung, L. & Lee, P. S. Impact of internet literacy, internet addiction symptoms, and internet activities on academic performance. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 30 , 403–418 (2012).

Xin, M. et al. Online activities, prevalence of Internet addiction and risk factors related to family and school among adolescents in China. Addict. Behav. Rep. 7 , 14–18 (2018).

PubMed Google Scholar

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., et al. The mental health of children and adolescents: report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing (2015).

Hafekost, J. et al. Methodology of young minds matter: the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 50 , 866–875 (2016).

Australian Curriculum ARAA. National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy: Achievement in Reading, Persuasive Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2011 . Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (2011).

Daraganova, G., Edwards, B. & Sipthorp, M. Using National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) Data in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) . Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2013).

NAP. NAPLAN (2016).

Australian Curriculum ARAA. National report on schooling in Australia 2009. Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth… (2009).

Vu, X.-B.B., Biswas, R. K., Khanam, R. & Rahman, M. Mental health service use in Australia: the role of family structure and socio-economic status. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 93 , 378–389 (2018).

McCullagh, P. Generalized Linear Models (Routledge, Abingdon, 2019).

Book Google Scholar

Gregg, P., Washbrook, E., Propper, C. & Burgess, S. The effects of a mother’s return to work decision on child development in the UK. Econ. J. 115 , F48–F80 (2005).

Khanam, R. & Nghiem, S. Family income and child cognitive and noncognitive development in Australia: does money matter?. Demography 53 , 597–621 (2016).

Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., Neter, J. & Li, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models (McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York, 2005).

Lumley T. Package ‘survey’. 3 , 30–33 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Western Australia, Roy Morgan Research, the Australian Government Department of Health for conducting the survey, and the Australian Data Archive for giving access to the YMM survey dataset. The authors also would like to thank Dr Barbara Harmes for proofreading the manuscript.

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Health Research and School of Commerce, University of Southern Queensland, Workstation 15, Room T450, Block T, Toowoomba, QLD, 4350, Australia

Md Irteja Islam & Rasheda Khanam

Maternal and Child Health Division, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), Mohakhali, Dhaka, 1212, Bangladesh

Md Irteja Islam

Transport and Road Safety (TARS) Research Centre, School of Aviation, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052, Australia

Raaj Kishore Biswas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.I.I.: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. R.K.B.: Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original draft preparation. R.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Md Irteja Islam .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Islam, M.I., Biswas, R.K. & Khanam, R. Effect of internet use and electronic game-play on academic performance of Australian children. Sci Rep 10 , 21727 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78916-9

Download citation

Received : 28 August 2020

Accepted : 02 December 2020

Published : 10 December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78916-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

I want to play a game: examining sex differences in the effects of pathological gaming, academic self-efficacy, and academic initiative on academic performance in adolescence.

- Sara Madeleine Kristensen

- Magnus Jørgensen

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Measurement Invariance of the Lemmens Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-9 Across Age, Gender, and Respondents

- Iulia Maria Coșa

- Anca Dobrean

- Robert Balazsi

Psychiatric Quarterly (2024)

Academic and Social Behaviour Profile of the Primary School Students who Possess and Play Video Games

- E. Vázquez-Cano

- J. M. Ramírez-Hurtado

- C. Pascual-Moscoso

Child Indicators Research (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Massively multiplayer online games and well-being: a systematic literature review.

- 1 School of Health and Behavioural Sciences, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, QLD, Australia

- 2 Institute of Health and Sports, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3 School of Psychology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 4 Thompson Institute, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, QLD, Australia

Background: Massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) evolve online, whilst engaging large numbers of participants who play concurrently. Their online socialization component is a primary reason for their high popularity. Interestingly, the adverse effects of MMOs have attracted significant attention compared to their potential benefits.

Methods: To address this deficit, employing PRISMA guidelines, this systematic review aimed to summarize empirical evidence regarding a range of interpersonal and intrapersonal MMO well-being outcomes for those older than 13.

Results: Three databases identified 18 relevant English language studies, 13 quantitative, 4 qualitative and 1 mixed method published between January 2012 and August 2020. A narrative synthesis methodology was employed, whilst validated tools appraised risk of bias and study quality.

Conclusions: A significant positive relationship between playing MMOs and social well-being was concluded, irrespective of one's age and/or their casual or immersed gaming patterns. This finding should be considered in the light of the limited: (a) game platforms investigated; (b) well-being constructs identified; and (c) research quality (i.e., modest). Nonetheless, conclusions are of relevance for game developers and health professionals, who should be cognizant of the significant MMOs-well-being association(s). Future research should focus on broadening the well-being constructs investigated, whilst enhancing the applied methodologies.

Introduction

Internet gaming is a popular activity enjoyed by people around the globe, and across ages and gender ( Internet World Stats, 2020 ). With the addition of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Health Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ) as a condition requiring further study, followed by the introduction of Gaming Disorder (GD) as a formal diagnostic classification in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2019 ), research concerning the associated adverse effects of gaming has increased ( Kircaburun et al., 2020 ; Teng et al., 2020 ). Accordingly, a series of potentially harmful aspects of internet gaming, such as reduced social skills, aggression, reduced family connection, interruptions to one's work and education have been cited ( Pontes et al., 2020 ).

Despite such likely aversive connotations, the uptake of internet gaming continues to increase. Recent statistics suggest that 64% of adults in the United States (U.S.) are gamers, 59% of those being male, with the average age range situated between 34 to 45 ( Entertainment Software Association, 2020 ). Of note is that 65% of those gamers are playing with others online or in person and they spend an average of 6.6 h playing per week with others online. Similarly, a survey of 801 New Zealand households (2,225 individuals) revealed that two-thirds play video games, with 34 years being the average age ( Brand et al., 2019 ).

Such high levels of game involvement have been interwoven with high reports of potential well-being benefits in the U.S. sample, including 80% for mental stimulation, 63% for problem solving, 55% for connecting with friends, 79% for relaxation and stress relief, 57% for enjoyment, and 50% for accommodating family quality time ( Entertainment Software Association, 2020 ). Interestingly, 30% of U.S. gamers met a good friend, spouse, or significant other through gaming ( Entertainment Software Association, 2020 ). Thus, video gaming does offer benefits, especially for one's socialization; indeed, gaming can simultaneously engage multiple online players ( Pierre-Louis, 2020 ; Pontes et al., 2020 ).

Multiplayer online games involve a broad genre of internet games, which entail participants playing with others in teams or competing within online virtual worlds ( Barnett and Coulson, 2010 ). A 2017 report of 1,234 Australian households (3,135 individuals) found 67% regularly played video games on computers, tablets, mobile phones, handheld devices, and gaming consoles, with 92% of those playing online with others ( Brand et al., 2017 ). When the “multiple-players” component allows the concurrent inclusion of large numbers (i.e., masses) of gamers, games are referred as massively multiplayer online games (MMOs; Stavropoulos et al., 2019 ). Such games employ the internet to simultaneously host millions of users globally. Participants tend to be organized in groups/teams/alliances competing with each other in the context of game worlds with progressively higher demands and challenges ( Adams et al., 2019 ). Massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) expand on this format of play with the introduction of role-playing characteristics through the creation of an avatar. This involves the player establishing their own customizable character for their gameplay, providing an opportunity for gamers to experiment with their own identity in a safe environment ( Stavropoulos et al., 2020 ). Thus, MMORPGs constitute a distinct subgenre of MMOs.

A preponderance of recent research on MMOs has focused specifically on the negative effects of problematic gaming or IGD ( Kircaburun et al., 2020 ; Pontes et al., 2020 ). For instance, a systematic review conducted by Männikkö et al. (2017) focused on health-related outcomes of problematic gaming behavior. This review aligns with prior research that looked at the risk factors and adverse health outcomes of excessive internet usage, particularly among adolescents ( Lam, 2014 ; Goh et al., 2019 ). Despite these efforts, Sublette and Mullan (2012) suggested that the evidence regarding the negative health consequences of gaming is inconclusive (e.g., overall health, sleep, aggression). As Internet games, and especially MMOs, may be also played moderately, they can accommodate a series of beneficial effects for the users such as socialization, a sense of achievement, and positive emotion ( Halbrook et al., 2019 ; Zhonggen, 2019 ; Colder Carras et al., 2020 ). Accordingly, the systematic literature review of Scott and Porter-Armstrong (2013) aimed to offer a more balanced view of the whole range of the positive and the negative effects of participation in MMORPGs, including on the psychosocial well-being of adolescents and young adults. They studied six research articles, where both negative and positive outcomes were identified; for instance, they concluded that problematic/pathological gaming associated with the negative outcomes such as depression, disrupted sleep, and avoidance of unpleasant thoughts. However, they also suggested that the MMORPG context could often provide a refuge from real-world issues, where new friendships and cooperative play could provide enjoyment. Correspondingly, a review of videogame use and flourishing mental health employing Seligman's 2011 positive psychology model of well-being (i.e., positive emotion; engagement; relationships; meaning and purpose; and accomplishment) reported that moderate levels of play was associated with improved mood and emotional regulation, decreased stress and emotional distress, and relaxation. Decisively, Jones and colleagues ( Jones et al., 2014 ) asserted that “videogame research must move beyond a “good-bad” dichotomy and develop a more nuanced understanding about videogame play” (p. 7).

Despite the progress made, no systematic literature to date has synthesized the state of the empirical evidence considering the well-being influences of MMOs. This is important for three reasons: (a) MMOs have had significant advancements in the last 5 years, which may have radically altered their well-being potential (i.e., audio, visual, and augmented reality effects; Alha et al., 2019 ; Semanová, 2020 ); (b) the MMO players community has significantly expanded ( Statista, 2021 ) and; (c) growing empirical evidence has widened the available knowledge of the effects of multiplayer gaming ( Sourmelis et al., 2017 ; Cole et al., 2020 ). Consequently, this present systematic review will contribute to the niche research area referring to the MMOs and well-being association. To address this purpose, the notion of psychosocial well-being and its operationalization needs to be clarified. Scott and Porter-Armstrong (2013) conceived one's level of well-being as expressed through an individual's interpersonal and intrapersonal functioning. In that context, the complexity related to the assessment of one's well-being is acknowledged ( Burns, 2015 ; Linton et al., 2016 ). On that basis, this review utilized the six broad well-being themes as delineated by Linton et al. (2016) to inform the theoretical framework of synthesizing MMO well-being related effects and evidence. The six themes are: (a) mental well-being (e.g., a person's thoughts and emotions); (b) social well-being (e.g., interactions and relationships with others, social support); (c) activities and functioning (e.g., daily activities and behavior); (d) physical well-being (e.g., person's physical functioning and capacity); (e) spiritual well-being (e.g., connection to something greater, faith) and; (f) personal circumstances (e.g., environmental factors; Linton et al., 2016 ).

To enhance the utility of findings, the present review will focus on the most prevalent age range of MMO gamers. The entertainment software association reported that of those playing video games, 21% are under the age of 18 years, 38% between 18 and 34, 26% between 35 and 54 and 15% 55 and over ( Pierre-Louis, 2020 ). In addition, the currently most popular MMOs were identified and targeted. According to the entertainment software association, these involve World of Warcraft, RuneScape, and Guild Wars 2 among gamers older than 13 years ( BeStreamer, 2020 ; Entertainment Software Association, 2020 ). All the available empirical evidence derived by randomized, controlled trials, cross-sectional studies, and case studies with n > 1 that identified any MMOs linked well-being outcomes was included and examined across the six well-being domains identified (see Linton et al., 2016 ). Thus, all the range of interpersonal and intrapersonal well-being outcomes for MMO players over the age of 13 were considered. The ultimate aim of this review is to contribute to balancing the available knowledge surrounding the impact of the popular MMO genre, whilst concurrently illustrating directions for gamer-centered and beneficial future research and mental health practice initiatives.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review followed the methodology suggested in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009 ; Shamseer et al., 2015 ). Research team discussion and perusal of related published reviews assisted the development of the initial research eligibility, search strategy, and related terms. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were further refined at the selection process stage, after exposure and familiarity with the research area; this review was limited to research obtained from database searches.

Eligibility Criteria

All research investigating massively multiplayer online gaming were eligible for review. The initial search eligibility criteria were (i) a publication date between 2012 to 2020; (ii) written in or translated into English language; and (iii) full-text, peer-reviewed primary research.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

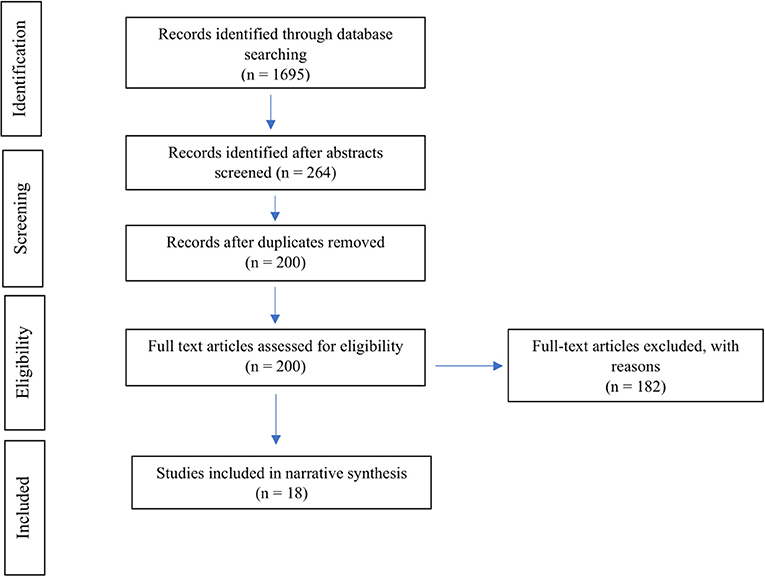

Searches were conducted in August 2020 using online databases, JB searched PsycNET (APA), and PUBMED; whereas, LR searched Scopus (see Figure 1 ). In each case, the following search terms and protocol were used (massively multiplayer online OR multiplayer online OR MMORPG OR MMOG) to search abstracts and/or titles. Searches were limited by publication date, 2012 to the present. No specific terms for well-being outcomes were prescribed to ensure that the literature search remained expansive. Accordingly, potential well-being effects were assessed at the screening stage.

Figure 1 . PRISMA flow diagram for the present study.

Selection Process and Data Management

After the title search, abstracts were independently screened by two investigators (JB & LR) for positive outcome measures, fitting within the identified well-being parameters (i.e., Linton et al., 2016 ). Example terms included, but were not limited to, “well-being,” “quality of life,” “social support,” “belonging,” “positive affect,” and “cognitive ability.” Where abstracts contained insufficient/unclear information, the full-text was reviewed for accurate evaluation. The resultant items/studies/records were pooled, and duplicates were removed. The remaining, potentially relevant studies were divided equally between LR and JB, and the full studies were subsequently (and independently) assessed. Where uncertainty of inclusion was noted, articles were screened by the alternate investigator (i.e., JB or LR). Then, if uncertainty regarding inclusion still remained, investigator LK was the final arbitrator (see Figure 1 ).

This detailed screening process utilized the following inclusion criteria: (i) qualitative or quantitative research of any design; (ii) written in or translated into English language; (iii) a primary study aim was psychological well-being (or a component of psychological well-being; Linton et al., 2016 ); and (iv) it was clearly indicated that participants were aged 13 years or over [according to Entertainment Software Association (2020) age ranges of high gaming prevalence]. Studies were excluded if: (i) they were single case studies, reviews of any kind (e.g., systematic reviews or meta-analyses), dissertations or theses, or opinions or discussion papers; (ii) the focus was IGD, problematic gaming or addiction; (iii) they involved online gambling, sexual foci (e.g., cybersex), exergaming, or e-sports; (iv) the game was not generally available to the wider community or was an educational tool; (v) they focused on motivations for engaging in online gaming or on learning English language; or (vi) gaming was not played on computers. Once articles were pooled, each reviewer independently recorded the reasons for excluding the articles in a shared file.

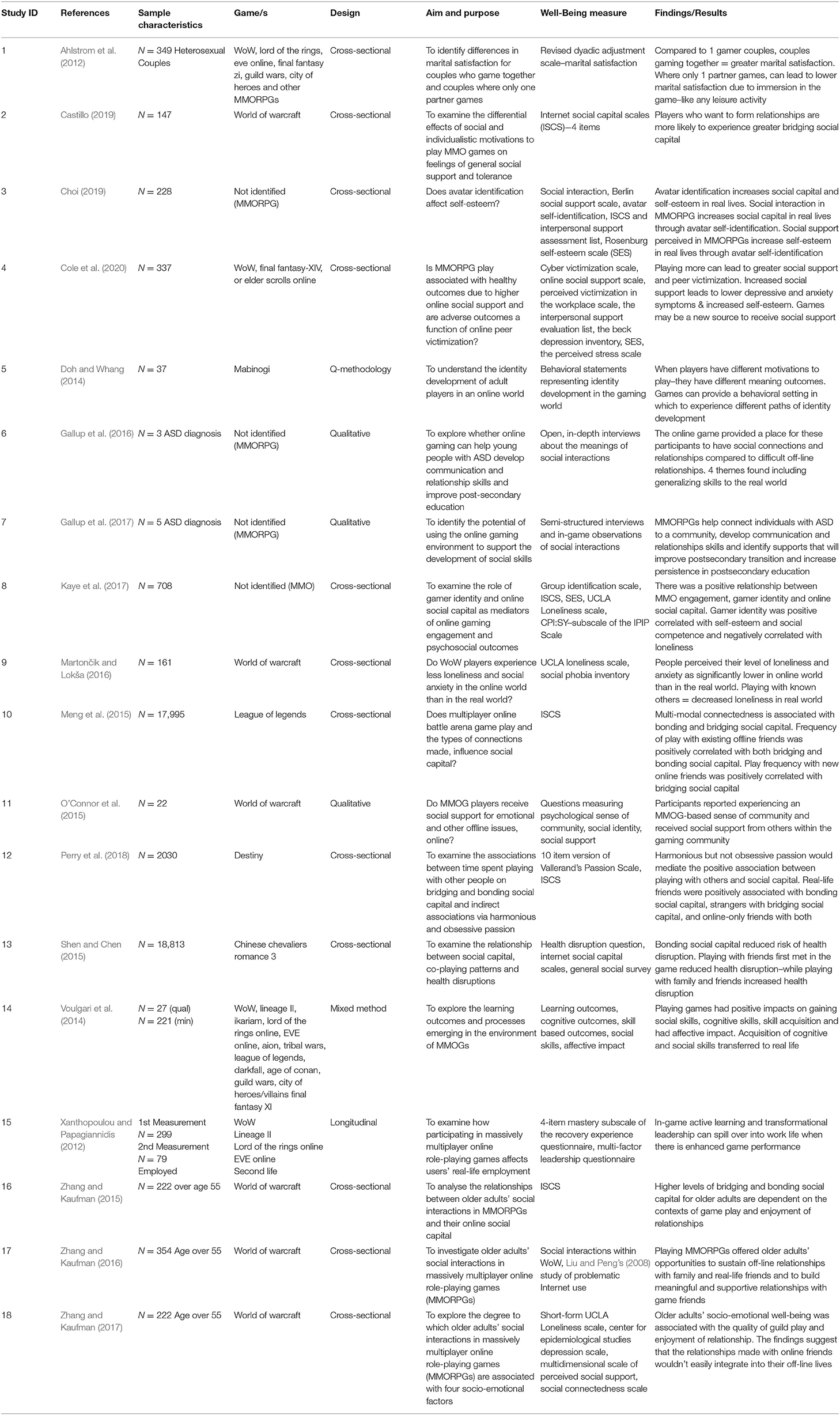

Data Extraction Process

The final studies were summarized according to the following characteristics: (1) study design (e.g., cross-sectional survey); (2) sample characteristics (i.e., size, source of recruitment); (3) the specific MMORPG(s) emphasized; (4) variables (i.e., types of social capital, types of networks); (5) instruments for assessing key variables (e.g., time in game, social capital); (6) the type of analysis used; (7) main findings in relation to well-being (e.g., relationship between game and well-being or with belongingness); and (8) limitations. Investigators SR and LR each independently reviewed half of the studies, with joint discussion to resolve any uncertainties. Table 1 summarizes the reviewed studies.

Table 1 . Main characteristics of reviewed studies ( N = 18).

Data Analysis Procedures and Quality

Given the diversity of study objectives and well-being outcomes reviewed, meta-analysis was not plausible. Therefore, a narrative synthesis methodology was adopted, as it involves a textual summation and explanation of the data which was considered appropriate considering the focus of this review ( Greenhalgh et al., 2005 ; Popay et al., 2006 ). Following the goals of this review, the analysis aimed to identify the key positive or well-being outcomes of playing MMORPGs. Consequently, comparable studies/results were grouped together categorizing the data into themes (and subthemes) that drew on the six well-being themes identified by Linton et al. (2016) . A narrative account of these results is presented under relevant thematic headings, along with any pertinent moderating factors ( Greenhalgh et al., 2005 ).

Risk of bias and quality of evidence evaluations were undertaken using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies ( Downes et al., 2016 ) for the quantitative studies, and the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research ( Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020 ) for the studies that used a qualitative methodology. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool ( Hong et al., 2018 ) was used by JB and LR to conduct their independent appraisals of each study. These were then compared and discussed across each item/study/record to conclude agreement.

Study Selection

As per the flow of information and studies is shown in Figure 1 , a total of 1695 studies (PsycNET n = 524, PubMed n = 500, Scopus n = 671) were identified through the initial search. After abstracts were reviewed, 1,431 studies were excluded due to not being suitable for the present review. A further 64 studies were removed for duplication. A full-text review was done on the remaining 200 studies. Of these 182 studies were excluded due to age of participants ( n = 8), focus on IGD or addiction ( n = 32), focus on motivations/predictors of play ( n = 24), not being in English ( n = 4), not being primary research ( n = 30), focused on education ( n = 16), full-text unable to be accessed ( n = 4), not exclusively MMO ( n = 8), only measuring in-game behaviors ( n = 29), or not meeting well-being criteria ( n = 27). Following this screening process, 18 studies were included in the final narrative synthesis (see Figure 1 ).

Study Characteristics

The main characteristics, including the aims and purpose of each study, the well-being measures used, and the results of each of the final 18 studies are noted Table 1 . For those studies which reported the gender of their participants, males accounted for the majority, ranging from 65 to 100% [the latter being the case in the qualitative study of Gallup et al. (2016) ]. One study was equally represented gender-wise ( Cole et al., 2020 ) and one had slightly more females (51%) than males ( Doh and Whang, 2014 ). Participants were from North America, China, Korea, Greece, and Australia. For those studies that reported the game platform, World of Warcraft was the most common ( n = 10). Twelve studies measured time spent gaming with variable time measures, such as hours weekly, per week-day, and weekend. Averages of hours per week ranged from 11 to 36.7, while daily hours were estimated to vary between 2 and 5.

Risk of Bias and Quality of Studies

Quality of reporting, study design quality and risk of bias was assessed for each of the 13 cross-sectional studies. All the cross-sectional studies had a moderate level of risk of bias [studies: 1–4, 8–10, 12, 13, 15-18]. This included sample issues [studies, 1-4, 8-10, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18]. Only one study provided information to justify their sample size, and this was through pragmatic rather than statistical reasons ( Zhang and Kaufman, 2015 ). Although seven studies [studies, 1, 4, 8, 10, 12, 13, 17] had sample sizes over 300, sample size was deemed to be an issue of concern given the millions of MMOG players globally ( Internet World Stats, 2020 ). Sampling methods raised concerns regarding risk of bias and study design quality, as most studies relied on self-selection, and one MMOG was the primary data collection source [six studies used this MMOG alone (studies 2, 9, 11, 16–18), while four studies (studies 1, 4, 14, 15) included this MMOG], although conclusions were often made with reference to MMOGs as a whole. Only six studies [studies, 2, 3, 10, 13, 15, 16] acknowledged or raised concerns regarding response rates, but did not provide clear information on this or expected response rates due to the impossibility of determining sampling frames. Furthermore, due to participant self-selection, the majority of studies did not compare responders and non-responders. Of the two studies [4, 15] that did consider response bias, one ( Cole et al., 2020 ) found no difference between non-completers and completers, while the other ( Xanthopoulou and Papagiannidis, 2012 ) found differences on four demographic characteristics (age, gender, occupational, and marital status). Considering the quality of design, the majority of the 13 cross-sectional studies were deemed to fall into a fair category, with a major concern being the omission of whether ethical approval or participant consent was obtained [studies 2, 3, 8–10, 12, 13, 15] and only three studies reporting that there were no funding or other conflicts [studies 2, 12, 17].