Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 20 March 2024

On the value of food systems research

Nature Food volume 5 , page 183 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1466 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Every study has limitations; the question is whether it moves the field forward and what this entails for each community.

A great deal of research is exclusively assessed in terms of technical quality, a metric that is arguably easier to measure in exact than non-exact sciences and that doesn’t say much about the impact of the research results to society. Its relevance is therefore limited when it comes to food systems research, which involves social and cultural elements and is motivated by grand societal challenges such as the fight against hunger, poverty and climate change. Questions related to food security and the sustainability of food systems, no matter whether they are approached through a nutritional, environmental or socioeconomic lens, tend to involve a great deal of complexity and context specificity.

Given the above, a question we ought to ask when assessing a food systems study is whether it moves the field forward and offers a substantial contribution despite its limitations. Equally important is to ask whether these limitations are transparently laid out. Ideally, the study would have a well-defined analytical framework and discuss the potential implications of its main assumptions, particularly if they are likely to change conclusions in a significant way. The line that marks the divide between ‘substantial’ and ‘non-substantial’ or ‘significant’ and ‘non-significant’, as used above, is to be drawn by the relevant research community — and is bound to change over time, based on that community’s understanding of what is useful or insightful in light of the field’s uncertainties. In the scientific peer-review process, the feedback of reviewers — as representatives of the research community — is key to making such a call.

What makes a piece of research valuable when it comes to food systems isn’t necessarily its degree of technical advance, but rather the conceptual advance it represents and the potential impact associated with it. For instance, the angle through which a problem is addressed and how it is framed can yield arresting and important conclusions, even when calculation methodologies remain unaltered. This point is well illustrated by food-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which were traditionally reported for each sector (transport, energy, industry, and so on) and supply stage (production, processing, distribution, consumption and waste) separately but have been more recently combined under ‘systems emissions’. While their breakdown informs sectoral policies, the sum of all GHG emissions is needed for synergies and trade-offs to be properly identified and accounted for 1 . Besides, the global overview of emissions is crucial for creating awareness around the impact of food choices and catalysing mitigation action. The message that food systems are currently responsible for a third of all current anthropogenic GHG emissions 2 , so widely publicized, was determinant for food systems to be placed at the centre of the climate agenda and to receive due attention from world leaders.

A recently proposed food classification system based on the degree of food processing that has singled out ultra-processed foods (UPFs) 3 provides another interesting case for reflection on how to evaluate research. Some scientists were critical of this new categorization, arguing that processing in itself isn’t what makes a food item good or bad for people and the environment, and highlighting mixed evidence on the impact of UPFs on biochemical risk factors for disease 4 . Others found it extremely useful for eliciting the association between the consumption of UPFs and many of their distinctive characteristics, which are themselves harmful to human health (either directly, like high sugar and/or additive content, or indirectly, through shifts in consumers’ preferences towards impoverished diets) and the environment. Undeniably, this classification has stimulated a healthy debate around modern dietary habits, the intricate factors behind them, and public policies’ sole focus on nutritional characteristics of foods.

As the examples above suggest, two more points deserve attention when thinking of the value — and contribution — of food systems research. The first point is about clarity over what a study can and cannot answer, and consequently what it should be used for. The combined account of food-related GHG emissions sheds light on food systems’ total footprint, underscoring the need for coordinated policies, but doesn’t replace sectoral granularity. Likewise, a food classification system based on UPFs may not say much about processing as a food engineering technique, yet it highlights important issues surrounding these products. The second point refers to the scope of the analysis and the multiplicity of aspects that are considered given the urgency of food systems transformation. Whether that’s done in a meaningful way and to a sufficient extent is for the food community to judge.

Rosenzweig, C. et al. Nat. Food 1 , 94–97 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Crippa, M. et al. Nat. Food 2 , 198–209 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Lawrence, M., Costa Louzada, M. L. & Pereira Machado, P. Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system (FAO, 2019); https://www.fao.org/3/ca5644en/ca5644en.pdf

Gibney, M. J. & Forde, C. G. Nat. Food 3 , 104–109 (2022).

Download references

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

On the value of food systems research. Nat Food 5 , 183 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00960-9

Download citation

Published : 20 March 2024

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00960-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Advanced Energy Technology platform

- Antarctic Science platform

- GNS Science

- Institute of Environmental Science and Research

- Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research

- Plant and Food Research

- Data Science platform

- Cawthron Institute

- NZ Leather & Shoe Research Association

- Infectious Disease research platform

- New Zealand Agricultural Green House Gas Research Centre

- Ngā rākau taketake – combatting kauri dieback and myrtle rust

- Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) Development platform

Plant and Food Research's science platforms

Plant and Food Research receives $42.7 million per year of Strategic Science Investment Fund (SSIF) funding for 2 science platforms – Plant-based food and seafood production and Premium plant-based and seafood products.

On this page

Mbie funding details.

In July 2017, Plant and Food Research received $42.7 million Strategic Science Investment Fund (SSIF) funding per year for 7 years to June 2024 for 2 science platforms - Plant-based food and seafood production, and Premium plant-based and seafood products.

In 2022/2023, they received a further $200,000 SSIF funding to support the provision of urgent science advice before, during, and after North Island Extreme Weather Events.

Extreme weather science response

About the research

Plant–based food and seafood production (receiving $20.9 million of Plant and Food Research’s annual SSIF funding) for deep understanding of the biology and physiology of key economic plant and seafood species, their pests and diseases and interactions with the environment e.g., precision seafood handling and harvesting regimes, fast fruit-fly detection.

Premium plant-based and seafood products (receiving $21.8 million of Plant and Food Research’s annual SSIF funding) for combining genetics, food and consumer science, and postharvest technologies and engineering to create value-added foods, beverages and other premium products e.g. new kiwifruit varieties, protecting consumers from seafood-borne illnesses.

Below is the public statement from our contract with Plant and Food Research.

Read the contract public statement from 2024

Plant & Food Research receives $42.7 million per year SSIF investment for research in 2 Science Platforms. A science platform is a combination of people, facilities, information and knowledge that provides a particular, ongoing science and innovation capability for New Zealand.

Plant-based food and seafood production ($20.9 million per annum)

Description: This platform supports capabilities that contribute to the sustainable production and protection of crops and seafood. By 2026, this platform will have produced a deeper understanding of the biology and physiology of key economic plant and seafood species, their production systems, their pests and diseases and interactions with the environment.

For New Zealand, this will mean:

- Improved and novel growing systems

- Sustainable management of soil and water

- New integrated pest/pathogen management systems

- Climate Change mitigations

- New capability in Digital Horticulture

- New technologies for improved Market Access and Biosecurity

The objective for our portfolio of research investments is to maximise impact for New Zealand using a whole-of-value chain approach, across different sectors and over multiple timeframes. We aim to achieve an appropriate balance of near and longer-term targets to ensure that impact is delivered at regular intervals, and to develop new ideas and capabilities for the future (currently $8.7 million Sector-based; $7.2 million Pan-sector-based; $5 million Future Science).

Premium plant-based and seafood products ($21.8 million per annum)

Description: Premium Plant-based and Seafood products platform supports capabilities that create value-added food and beverages. By 2026, this platform will be combining genetics, food, consumer science and postharvest technologies and engineering to create value-added foods, beverages and other premium products.

For New Zealand this will mean:

- World class breeding programmes utilising the latest technologies

- Future foods and biomaterials

- New postharvest technologies

- Consumer Science-informed food development

- Improved food safety and assurance

- Enhanced data analytics, including bioinformatics

The objective for our portfolio of research investments is to maximise impact for New Zealand using a whole-of-value chain approach, across different sectors and over multiple timeframes. We aim to achieve an appropriate balance of near and longer-term targets to ensure that impact is delivered at regular intervals, and to develop new ideas and capabilities for the future (currently $14.8 million Sector-based; $2 million Pan-sector-based; $5 million Future Science).

For further information on Plant & Food Research’s SSIF investment contact Richard Newcomb, [email protected] .

Read the contract public statement from 2017

Plant-based food and seafood production ($20.9 million per year)

Supports capabilities that contribute to the sustainable production and protection of crops and seafood.

By 2024, this platform will have produced a deeper understanding of the biology and physiology of key economic plant and seafood species, their production systems, their pests and diseases and interactions with the environment. For New Zealand, this will mean:

- improved and novel growing systems

- sustainable management of soil and water

- new integrated pest/pathogen management systems

- climate Change mitigations

- new capability in Digital Horticulture

- new technologies for improved Market Access and Biosecurity.

Premium plant-based and seafood products ($21.8 million per year)

Supports capabilities that create value-added food and beverages. By 2024, this platform will be combining genetics, food, consumer science and postharvest technologies and engineering to create value-added foods, beverages and other premium products. For New Zealand this will mean:

- world class breeding programmes utilising the latest technologies

- future foods and biomaterials

- new postharvest technologies

- consumer Science-informed food development

- improved food safety and assurance

- enhanced data analytics, including bioinformatics.

Annual updates

Recipients of SSIF funding are required to report yearly on the progress of their work programme. Below are the public updates from Plant and Food Research Institute’s annual reports.

Read the public update from the 2022/23 annual report

Platform 1: Plant-based food and seafood production

This Platform provides research and capabilities in the biology of key economic plant and seafood species, production systems, pests and diseases, and interactions with the environment to support innovation in the sustainable production and protection of crops and seafood.

In 2022 to 2023, $19.1 million was invested in basic-targeted research through the Tuia ki te Whenua Sustainability and Provenance Wins Ngā Pou Rangahau- Growing Futures Direction to deliver research ‘today’ to underpin ‘tomorrow’s’ future growing environments, and in the Digital Horticultural Systems Direction to explore how digital technologies might transform perennial horticulture towards a fully-autonomous future. These investments delivered research on stakeholder perspectives, sensing and imaging, data architecture and visualisation, apple system models, simulated orchard ecosystems, and regenerative food systems. As well, research to support the recovery from the effects of Cyclone Gabrielle and a new tool to evaluate the depth of our huatahi partnerships with Māori were funded through Platform 1.

In this Platform $4 million was invested in Better Border Biosecurity research to reduce the entry and establishment of new plant pests and diseases in Aotearoa New Zealand. In 2022/2023 $12.9 million of research activity was classified as Discovery Science. SSIF investment supported ongoing and new collaborations with leading research organisations in Aotearoa New Zealand and around the world that enable researchers to benchmark science; access new thinking, capabilities, facilities and environments; and ensure Aotearoa New Zealand benefits from relevant science advances. New technologies were also produced to protect horticultural sectors from high impact pests and diseases through our investment in the Better Border Biosecurity collaboration. This year 277 papers were published, our SciMago score was 4.84, and the percentage of collaborative publications was 88%.

Additional information (external link) — Plant & Food Research

Platform 2: Premium plant-based and seafood products

This Platform provides basic-targeted research and capabilities in genetics, food and consumer science, and postharvest technologies and engineering to support premium foods, beverages and other high-value products.

In 2022 to 2023, $23.57 million was invested in 3 Ngā Pou Rangahau - Growing Futures (NPR-GF) Directions: Hua ki te Ao Horticulture Goes Urban, Ngā Tai Hōhonu Open Ocean Aquaculture and Authentic Taonga Foods. These Directions deliver basic-targeted research ‘today’ that underpins longer-term opportunities ‘tomorrow’. NPR-GF investments delivered research on future urban consumers, traits for life indoors, overcoming pollination barriers, environmental plant hacking, Māori growing practices go vertical, performance measurement technologies for aquatic food production systems, fish species selection and assessment, aquafeeds for open ocean aquaculture, and cellular systems to support healthy fish.

Platform 2 also funded an initiative on taonga data that has contributed to a pan-CRI initiative in this area, a collaboration with AgResearch in food material biosciences, and a project on exploring taonga species with Māori partners. This year approximately $21.4 million was invested in Discovery Science. SSIF investment supported collaborations with leading research organisations in Aotearoa New Zealand and around the world. These collaborations enabled researchers to benchmark science; access new thinking, capabilities, facilities and environments; and ensure Aotearoa New Zealand benefits from advances in genetics, food and consumer science, technologies and engineering.

Research outputs described new fish rearing systems, novel technologies for measuring fish performance, aquafeeds, species selection frameworks, use of biofilms, a biobank of fish cell lines, survey tools for assessing consumer perceptions of food systems, plant traits for indoor growing systems, new propagation techniques for woody plants, and genetic control of fruit development. This year 277 peer-reviewed scientific papers were published. Our SciMago score for science excellence is 4.84. Our measure of research collaboration (percentage of peer-reviewed publications) was 88%.

Read the public update from the 2021/22 annual report

Platform 1 provides underpinning research and capabilities in the biology of key economic plant and seafood species, their production systems, pests and diseases, and interactions with the environment to support innovation in the sustainable production and protection of crops and seafood.

In 2021/22, $20.9 M was invested in basic targeted research through the Tuia ki te Whenua Sustainability and Provenance Wins Growing Futures Direction, which is delivering research ‘today’ to underpin ‘tomorrow’s’ future growing environments , and a new Digital Horticultural Systems Direction exploring how digital technologies might transform perennial horticulture towards a fully-autonomous future. New programmes were: `Data Architecture, Analytics and Visualisation’; `Modelling High Performance Apple Systems’; `Simulating Orchard Ecosystems’, and `Smart Sensing and Imaging Systems’. Investments across these two Directions delivered research on regenerative production ecosystems, future supply chains, new models of perennial horticulture and the deployment of digital twins. In this platform $3.9 M was invested in Biosecurity Aotearoa research to reduce the entry and establishment of new plant pests and diseases in New Zealand.

In 2021/22 $12.5 M of research activity was classified as Discovery Science. SSIF investment supported ongoing and new collaborations with leading research organisations in New Zealand and around the world. These collaborations enabled Plant & Food Research to benchmark science; access new thinking, capabilities, facilities and environments; and ensured New Zealand benefits from advances in crop protection and sustainable production science. Research outputs contributed to improved and novel growing systems, sustainable management of soil and water, new integrated pest/pathogen management systems, climate change mitigations, new capability in emerging digital technologies, and new technologies for improved market access and biosecurity. This year 352 peer-reviewed scientific papers were published. Our SciMago score for science excellence is 4.9. Our measure of research collaboration (percentage of scientific peer-reviewed publications) this year is 81%.

Platform 2 provides underpinning basic targeted research and capabilities in genetics, food and consumer science, and postharvest technologies and engineering to support the development of premium foods, beverages and other high-value products. In 2021/22, $21.8 M was invested in sector and pan-sector-aligned programmes and two Growing Futures Directions ‒ Hua ki te Ao Horticulture Goes Urban (HgU) and Ngā Tai Hōhonu Open Ocean Aquaculture (OOA) ‒ delivering basic-targeted research ‘today’ to underpin longer-term opportunities ‘tomorrow’. HgU programmes commenced on `Foods by Design’, `Environmental Plant Hacking’, and `Māori Growing Practices go Vertical’. OOA programmes commenced on `New Open Oceans Ecosystems’ and `Cellular Systems for Fish Health’. Growing Futures investments delivered research on future urban consumers, traits for life indoors, performance measurement technologies for aquatic food production systems, fish species selection and assessment, and aquafeeds for open ocean aquaculture.

This year ~$17.2 M was invested in Discovery Science. SSIF investment supported ongoing and new collaborations with leading research organisations in New Zealand and around the world. These collaborations enabled Plant & Food Research to benchmark science; access new thinking, capabilities, facilities and environments; and ensure New Zealand benefits from advances in genetics, food and consumer science, technologies and engineering. Research outputs enhanced breeding programmes, future foods and biomaterials and growing systems for producing them. This year 352 peer-reviewed scientific papers were published. Our SciMago score for science excellence is 4.9. Our measure of research collaboration (percentage of scientific peer-reviewed publications) this year is 81%.

More information

Learn more about Plant and Food Research (external link) — Plant & Food Research

Crown copyright © 2024

https://www.mbie.govt.nz/science-and-technology/science-and-innovation/funding-information-and-opportunities/investment-funds/strategic-science-investment-fund/ssif-funded-programmes/crown-research-institute-platforms/plant-and-food-research Please note: This content will change over time and can go out of date.

share this!

August 17, 2023

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

The power of plants and how they are changing the way we eat and live

by Megan Borders, University of New Mexico

Plant-based eating and veganism have been around for decades, but more people are choosing plant-based diets than ever before. Plant-based eating means eating more fruits, vegetables, nuts, grains and beans while eating less or no meat, dairy or animal products. A UNM business school researcher has studied the reasons behind this trend.

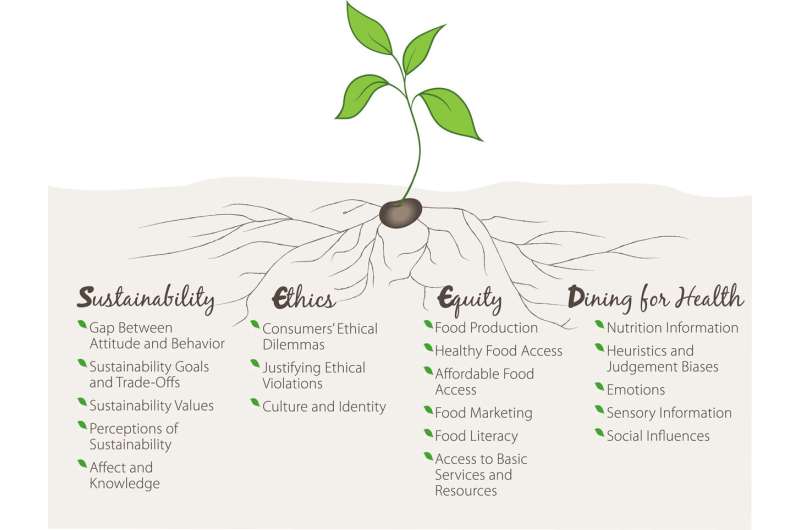

Lama Lteif, an assistant professor of marketing at the UNM Anderson School of Management, in her 2023 article, "Plant Power: SEEDing our Future with Plant-based Eating," shared a new way to look at why people are choosing plant-based diets and the benefits of this shift. She built on data from the 2021 Rockefeller Foundation report to explain people's food choices. Her work features a framework showing the values that drive consumers toward plant-based eating. The framework is called SEED: Sustainability, Ethics, Equity and Dining for Health.

Plant Power is the first research article of its kind, "because it is at the intersection of consumer health and the climate crisis. Understanding the reasons that drive consumers to choose a plant-based diet is good for people and the environment," said Lteif.

The SEED Framework

As more people relate to the values in the SEED framework, they are changing their food habits to reflect these beliefs.

"By understanding how these values influence decision-making, individuals and marketers alike can make better choices for themselves, inform their marketing strategies , and give more attention to the issues that mean the most to them," Lteif explained.

Those who relate to the Sustainability value have growing concerns about animal farming and its role in climate change. People have learned that eating less meat can reduce their carbon footprint and help ease the effects of global warming.

Next, Lteif explained that a person's belief system, or code of Ethics, can also affect their eating choices. Within this group is a growing concern for animal safety and well-being during meat and dairy production. Animal handling practices can include cramped living conditions, overcrowding or inhumane treatment. By not eating these foods, those holding this value hope to show their concern and support better animal treatment.

Food Equity refers to offering all people affordable access to food and the ability to cook and store the food that allows them to thrive. There is a growing awareness that many people do not have access to plant-based food or the means to keep it fresh. More so, underserved communities, including communities of color, often have less access to healthy, affordable, plant-based foods. Improving access can improve people's health and well-being by eating more healthy foods and allowing them to make choices that reflect their values.

Lastly, the Dining for Health value supports the connection between food and health. A plant-based diet is rich in fiber, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants, which help improve gut health and absorbing of nutrients that support the immune system. Because of this, a diet that is rich in fruits and vegetables can help reduce the risk of certain cancers, type 2 diabetes, heart disease and more.

Plant-based eating and its impact on the future

Lteif, a former nutritionist, combines her passion for helping others make healthy food choices with a curiosity about the drivers behind people's eating choices. She likens these value-based choices to a seed's root system, where the "SEED values connect and as a group can influence a person's eating habits. If embraced by society as a whole, these values can transform systems to be more friendly to our environment, more fair and more nourishing."

Lteif explained that Gen Z, those aged 35 and younger, are leading the way with alternative food choices due to their concerns about climate change and the environment. She believes learning more about the other value groups and the reasons keeping others from making healthy food choices is important. She would also like to explore ways to encourage more people to adopt a plant-based diet.

A great benefit of eating more fruits and vegetables is more demand for restaurants, grocery stores and eateries that offer vegan-friendly options. This increase in offerings makes it easier for people to make healthier choices today than ever before.

The work is published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology .

Journal information: Journal of Consumer Psychology

Provided by University of New Mexico

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Mature forests are vital in frontline fight against climate change, research reveals

Align or die: Revealing unknown mechanism essential for bacterial cell division

Study unveils limits on the extent to which quantum errors can be 'undone' in large systems

22 hours ago

Mars and Jupiter get chummy in the night sky. The planets won't get this close again until 2033

Aug 11, 2024

Saturday Citations: A rare misstep for Boeing; mouse jocks and calorie restriction; human brains in sync

Aug 10, 2024

Flood of 'junk': How AI is changing scientific publishing

135-million-year-old marine crocodile sheds light on Cretaceous life

Aug 9, 2024

Researchers discover new material for optically-controlled magnetic memory

A new mechanism for shaping animal tissues

NASA tests deployment of Roman Space Telescope's 'visor'

Relevant physicsforums posts, cover songs versus the original track, which ones are better.

4 hours ago

Why are ABBA so popular?

12 hours ago

Favorite songs (cont.)

20 hours ago

Talent Worthy of Wider Recognition

Who is your favorite jazz musician and what is your favorite song, biographies, history, personal accounts.

More from Art, Music, History, and Linguistics

Related Stories

Vegan diet has just 30% of the environmental impact of a high-meat diet, major study finds

Jul 24, 2023

70% of Americans rarely discuss the environmental impact of their food

Feb 13, 2020

Study shows climate impact labels on food sold in fast food restaurants can change buying habits

Dec 28, 2022

Three ways to unlock the power of food to promote heart health

Mar 20, 2023

The Mediterranean diet: Good for your health and your wallet, says study

May 24, 2023

Not everyone is aware that sustainable diets are about helping the planet

Dec 13, 2022

Recommended for you

Exploring the evolution of social norms with a supercomputer

Study reveals how the Global North drives inequality in international trade

Study shows people associate kindness with religious belief

Research demonstrates genetically diverse crowds are wiser

Aug 8, 2024

Dutch survey study links air ventilation and other factors to work-from-home success

Aug 7, 2024

TikToks—even neutral ones—harm women's body image, but diet videos had the worst effect, study finds

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Scientists Keep Finding Heavy Metals in Dark Chocolate. Should You Worry?

New research adds to the evidence that certain cocoa products contain lead and cadmium.

By Dani Blum

New research published Wednesday found heavy metals in dark chocolate, the latest in a string of studies to raise concerns about toxins in cocoa products.

The researchers tested 72 dark chocolate bars, cocoa powders and nibs to see if they were contaminated with heavy metals in concentrations higher than those deemed safe by California’s Proposition 65, one of the nation’s strictest chemical regulations.

Among the products tested, 43 percent contained higher levels of lead than the law considers safe, and 35 percent had higher concentrations of cadmium. Both metals are considered toxic and have been associated with a range of health issues. The study did not name specific brands, but found that organic products were more likely to have higher concentrations. Products certified as “fair trade” did not have lower levels of heavy metals.

But on the whole, the levels were not so high that the average consumer should be concerned about eating dark chocolate in moderation, said Jacob Hands, the lead author on the paper and a medical student at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Nearly all of the chocolates contained less than the Food and Drug Administration’s reference limits for lead, which are less stringent than the California requirement. And while both cadmium and lead can carry significant health risks, it’s not clear at this point that eating a few squares of dark chocolate poses a risk to most healthy adults.

“Just the fact that it exists doesn’t necessarily mean immediately there’s going to be some terrible health consequence,” said Laura Corlin, an associate professor of public health and community medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine who was not involved in the study.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Consumer Preference Segments for Plant-Based Foods: The Role of Product Category

Armand v. cardello.

1 A.V. Cardello Consulting and Editing Services, Framingham, MA 01701, USA

Fabien Llobell

2 Addinsoft, XLSTAT, 75018 Paris, France

Davide Giacalone

3 SDU Innovation & Design Engineering, Department of Technology and Innovation, University of Southern Denmark, 5230 Odense, Denmark

Sok L. Chheang

4 The New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research Limited, Mt Albert Research Centre, Private Bag 92169, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Sara R. Jaeger

Associated data.

Data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the authors.

A survey of willingness to consume (WTC) 5 types of plant-based (PB) food was conducted in USA, Australia, Singapore and India ( n = 2494). In addition to WTC, emotional, conceptual and situational use characterizations were obtained. Results showed a number of distinct clusters of consumers with different patterns of WTC for PB foods within different food categories. A large group of consumers did not discriminate among PB foods across the various food categories. Six smaller, but distinct clusters of consumers had specific patterns of WTC across the examined food categories. In general, PB Milk and, to a much lesser extent, PB Cheese had highest WTC ratings. PB Fish had the lowest WTC, and two PB meat products had intermediate WTC. Emotional, conceptual and situational use characterizations exerted significant lifts/penalties on WTC. No penalty or lifts were imparted on WTC by the situational use of ‘moving my diet in a sustainable direction’, whereas uses related to ‘when I want something I like’ and ‘when I want something healthy’ generally imparted WTC lifts across clusters and food categories. The importance of this research for the study of PB foods is its demonstration that consumers are not monolithic in their willingness to consume these foods and that WTC is often a function of the food category of the PB food.

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, it has become increasingly clear that the consumption of animal products has had unsustainable effects on the environment through high demand on land, water, feed, housing and the production of greenhouse gases [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. In addition, excess consumption of animal products is known to have harmful effects on human health, including cancer, cardiovascular disease and obesity [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. In response to these known detrimental effects of animal protein consumption on the environment and human health, global food policy has shifted to place greater emphasis on more sustainable farming practices and protein sources [ 1 , 16 , 17 ]. Leading this trend has been the emphasis on plant-based protein consumption [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. This trend has resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of plant-based foods, beverages, product extenders and/or meat alternatives now available globally. It is estimated that the plant-based food market will further grow from approximately $US 30 billion in 2020 to $US 160 billion by 2030 [ 21 ]. In addition to plant-based proteins, a variety of other alternative proteins are now being investigated for their potential to replace animal protein in foods, e.g., algae, insects, and cultured meat [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ].

1.1. Factors Influencing Acceptance of Plant-Based and Other Alternative Proteins

With the rapid growth in the alternative protein food market, research into the factors that drive consumer choice, purchase, acceptance and consumption of foods containing these proteins has grown correspondingly. Among the many factors that influence consumer acceptance and choice behavior toward these products are their sensory properties, e.g., taste, odor, texture, appearance [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ], their familiarity [ 23 , 25 , 26 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ], price/brand [ 37 , 45 , 46 , 47 ] and how appropriate the alternative protein is within the meal or its context of use [ 37 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ].

Other important factors relate more specifically to the individual. These include the health concerns of individuals and the perceived benefits attributed to the alternative protein [ 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ], the consumers’ attitudes [ 36 , 44 , 55 , 61 , 62 ], their values and cultural norms [ 3 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 ] and their neophobic tendencies [ 25 , 28 , 32 , 38 , 40 , 44 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 ].

Due to the important impact of individual factors in alternative protein acceptance, several studies have searched for distinct segments of consumers with different preferences for alternative proteins. Thus, de Boer et al. [ 29 ] examined consumer involvement with food and its influence on the acceptance of alternative proteins. These researchers identified ‘trendsetters’ who sought more authentic proteins, like lentils and seaweeds, but eschewed hybrid products like meat extended with plant proteins [ 29 ]. Van der Zanden et al. [ 74 ] examined preference segments among elderly consumers and found that the type of carrier (food type) for the protein was an important differentiator among different clusters of consumers, as was the meal type (meal component vs. snack). Health-orientation was another important variable differentiating a majority of consumer segments in a study of seaweed protein consumption by Palmieri and Forleo [ 75 ], as well as in a study by Possidónio et al. [ 76 ] who identified 3 segments of alternative protein consumers; (1) hedonically motivated meat eaters uninterested in meat substitutes, (2) health-oriented meat eaters open to some meat substitutes, and (3) ethically conscious meat avoiders positive toward protein alternatives to meat. Finally, in a study by Aschemann-Witzel and Peschel [ 34 ], individuals who previously purchased or consumed vegetarian products had more differentiated associations to different protein types, suggesting that different segments of consumers may respond differentially to plant proteins depending on the category of food.

Despite the environmental and health reasons that support consumption of alternative protein foods, research has shown that consumer acceptance and choice behavior toward these products is lower than for their animal counterparts [ 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 ]. Despite the need to identify alternative proteins with the greatest potential for acceptance by consumers, most research has examined consumer attitudes and acceptance within the context of a single protein source, e.g., plants, pulses, algae, seaweed, insects, etc., and relatively fewer have studied multiple alternative proteins [ 80 ]. Among studies comparing multiple proteins, results have generally shown that plant-based proteins are more acceptable to consumers than other protein sources, e.g., seaweed and cultured meat, and that insect protein is the least preferred [ 47 , 53 , 76 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 ]. Nevertheless, a recent review of the literature on alternative proteins found that the vast majority of published research studies focused on insect protein and far fewer examined plant proteins [ 80 ].

1.2. Role of Food Product and Food Category

Although several studies have examined different alternative proteins or protein mixes within the same product, e.g., hamburger, milk alternatives, lasagna [ 47 , 48 , 82 , 85 , 86 ], relatively few have examined differences in acceptance/willingness to consume as a function of product type, in spite of the fact that in their review of the area, Hartmann and Siegrist [ 77 ] found that acceptance of alternative proteins varies by product and that “it is of little value to ask consumers about abstract concepts (e.g., are you willing to eat insects?”). Still fewer studies have compared consumer reactions to alternative proteins based on differences in the target food group or category (e.g., milk, cheese, meat, fish, etc.). This, too, in spite of the fact that the food category to which a product belongs has been shown to have a strong influence on consumer responses to alternative proteins.

In one series of studies, Elzerman et al. [ 49 , 50 , 87 ] showed that alternative proteins differ in acceptance depending upon the food (or food category) in which they are incorporated. For example, consumers were found to have a greater willingness to accept meat substitutes when served with spaghetti than as part of a soup. Similarly, Michel et al. [ 37 ] observed significant interactions between protein type (meat vs. non-meat) and product groups in the cognitive associations to different test products (e.g., nuggets, sausages). In still another study on alternative plant proteins, Aschemann-Witzel and Peschel [ 34 ] found differences in consumer perceptions of these products depending on food category. In their study, consumers were shown ingredient lists that accompanied sketches of two different products identified as being in the food categories of “protein drink” or “sorbets.” The ingredient list for each product category was varied to include either the term ‘protein’, ‘vegetable protein’, ‘soy protein’, ‘pea protein’ or ‘potato protein’. Results showed that the product category evoked specific associations for the protein(s), e.g., ‘nutrition’ for protein drinks and ‘functional’ for sorbets, and that more positive associations accrued to the protein drinks and more negative associations to the sorbets. Further, the nature of the protein evoked different associations depending on the food category in which it appeared. Functional roles, e.g., serving as a cohesive ingredient, were evoked for the potato and pea proteins, but only within the sorbet category.

The food category to which a specific food belongs is an important factor influencing consumer behavior toward it, because it serves a variety of purposes and needs for the consumer [ 34 ]. Primary among these is that food categories establish the context within which the product is conceptualized by the consumer. For example, ‘salmon’, as a product, is conceptually a member of the food category ‘fish’ and, thereby, accrues a variety of cognitive, emotional and situational use associations and expectations that are shared by all types of fish, e.g., specific sensory (odor, texture) expectations, expectations related to preparation, cooking, etc. Similarly, for insect proteins, although, ants, beetles, and mealworms all have different sensory attributes, consumers react to these products in a similar way, simply because they are all members of the ‘insect food’ category, which evokes both generalized neophobic and disgust responses in many individuals [ 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 ]. Even in routine CLT tests on familiar products, it has been shown that over 75% of consumers, when asked after the test whether they rated their liking of that food within the context of ‘this kind of food’ or ‘all foods’, reported that their ratings were made within the context of ‘this kind of food’ [ 48 ].

To our knowledge, it has not previously been shown across a range of possible food categories that consumers hold distinct PB food category preferences or that (for example) a high WTC for one PB food category is an unreliable predictor of WTC (and preferences) for other PB food categories. However, if true, this finding would have implications for the promotion of PB diets, since it could imply that promotional campaigns, if category generic, may resonate with fewer people than a more category-targeted campaign. Thus, one goal of the present research is to explore the degree to which WTC for PB foods is dependent on the food category to which the PB food belongs.

1.3. Objectives and Overview of the Empirical Approach

Building on the above research threads, the specific objectives of the present research were: (1) to examine consumers’ willingness to consume plant-based protein within a number of distinct food categories, (2) to determine if there are different segments of consumers who have different patterns of their willingness to consume plant-based proteins, and to (3) assess differences in the identified segments of consumers in terms of their emotional, cognitive or situational use characterizations of the different plant-based categories of food and the impact of these variables on their judgments of willingness to consume these products. The latter objective is aimed at filling the literature gap identified by Onwezen et al. [ 94 ] in which it was noted that, with minor exceptions [ 37 , 82 , 94 ] few studies have examined either the role of emotions or other affective variables on acceptance of alternative proteins or the physical or social environment in which consuming such proteins is most appropriate or contextually acceptable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. participants.

Consumer insights for a global challenge like sustainable food production are more comprehensive when research is conducted in multiple countries. For this reason, participants in the present research came from the United States of America (US, n = 629), the Commonwealth of Australia (AU, n = 623), the Republic of Singapore (SG, n = 627), and the Republic of India (IN, n = 615). These countries differed on several dimensions including geographical location, population size, national cultures [ 95 ], importance of F&B sectors in national economies [ 96 ], sustainable energy [ 97 ], proportion of people following a vegetarian/vegan diet [ 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 ], growth rates of plant-based foods in retail [ 102 ], as well as the regulatory and legal policies regarding the labeling of PB foods. Country selection was also informed by a desire to lessen the dominance of Sensory-Consumer research taking place in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) and especially Anglocentric countries [ 103 ].

Participants had self-registered on a database managed by a web panel provider with ISO 20252:2019 accreditation (ISO: International Organization for Standardization [ 104 ]). A quota sampling strategy was imposed by country with interlocking quota for men (50%) and women (50%) across two age groups (18–45 y.o. (50%), 46–69 y.o. (50%)). The samples were not nationally representative, but diverse across a range of characteristics such as living location, educational attainment, marital status, etc. ( Table 1 ) ( Part S1 of Supplementary Materials has country specific details). High proficiency in English and regular participation household grocery shopping and food preparation (more than once a week) were imposed as eligibility criteria.

Participant characteristics for aggregate sample and by consumer segments based on willingness to consume (WTC) for plant-based (PB) food categories.

| Aggregate | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2494 | 1382 | 127 | 214 | 296 | 150 | 143 | 182 |

| Country (%) | ||||||||

| Australia | 25 | 27.6 | 11.8 | 18.7 | 13.5 | 34.7 | 22.3 | 34 |

| India | 24.7 | 17.2 | 63.8 | 26.2 | 44.6 | 30 | 25.9 | 14.3 |

| Singapore | 25.1 | 28.4 | 14.2 | 25.7 | 25.7 | 15.3 | 18.9 | 19.8 |

| United States | 25.2 | 26.8 | 10.2 | 29.4 | 16.2 | 20 | 32.9 | 31.9 |

| Biological sex (%) | ||||||||

| Female | 50 | 49.1 | 52.8 | 54.2 | 46.6 | 59.3 | 59.4 | 40.7 |

| Male | 50 | 50.9 | 47.2 | 45.8 | 53.4 | 40.7 | 40.6 | 59.3 |

| Age group (%) | ||||||||

| 18–45 y.o. | 49.5 | 47.8 | 47.2 | 54.2 | 51 | 45.3 | 55.2 | 55.5 |

| 46–69 y.o. | 50.5 | 52.2 | 52.8 | 45.8 | 49 | 54.7 | 45.8 | 44.5 |

| Education (%) | ||||||||

| High school, vocational or short graduate | 36.8 | 41.2 | 19.7 | 32.7 | 29.7 | 37.3 | 25.2 | 40.1 |

| University education (Bachelor or higher) | 62.8 | 58.4 | 80.3 | 66.8 | 70.3 | 62 | 74.8 | 58.8 |

| Prefer to not answer | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.1 |

| Dietary preference (%) | ||||||||

| Flexitarian | 33.9 | 29.2 | 35.4 | 35.5 | 45.9 | 38 | 48.3 | 32.4 |

| Omnivore | 59.7 | 68 | 35.4 | 60.3 | 41.9 | 52 | 35.7 | 66.5 |

| Vegetarian | 6.5 | 2.8 | 29.1 | 4.2 | 12.2 | 10 | 16.1 | 1.1 |

| Food Neophobia | 36.8 | 37.4 | 37.8 | 35.1 | 37.2 | 35.1 | 35.4 | 35.7 |

| [M (SD)] | (10.2) | (10.6) | (8.7) | (9.1) | (9.0) | (11.9) | (9.4) | (10.5) |

| Food Technology Neophobia | 56.3 | 57.5 | 55.6 | 54.4 | 53.7 | 57.6 | 53.2 | 55.1 |

| [M (SD)] | (11.6) | (11.9) | (11.2) | (10.7) | (11.1) | (11.0) | (11.0) | (10.0) |

| Environmental concern | 62.4 | 60 | 67.1 | 64.3 | 64.6 | 64.3 | 66.1 | 62.4 |

| [M (SD)] | (12.4) | (11.9) | (11.7) | (11.0) | (10.7) | (11.0) | (12.6) | (11.1) |

Food Neophobia (FN) scores could range between 10 and 70, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of FN. Values are mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). Food Technology Neophobia (FTN) scores could range between 13 and 91, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of FTN. Values are mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). Environmental concern (ENV) scores could range between 12 and 84, with higher scores reflecting more positive attitude toward the environment. Values are mean (M) and standard deviation (SD).

Human Ethics Statement

The study was covered by a general approval for sensory and consumer research from the Human Ethics Committee at the New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research Limited. Participants gave voluntary consent and were assured that their responses would remain confidential. They were informed that they could end their participation at any time. As compensation, participants received reward points which could be redeemed for online purchases.

2.2. Plant-Based Food Stimuli

The research focused on 5 plant-based (PB) foods (abbreviations for figures and tables in brackets):

- Milk—from 100% plant-based ingredients ( PB Milk )

- Cheese—from 100% plant-based ingredients ( PB Cheese )

- Meat—blend containing 33% plant-based ingredients ( PB Meat 33%)

- Meat—from 100% plant-based ingredients ( PB Meat )

- Fish—from 100% plant-based ingredients ( PB Fish )

Milk and cheese were chosen because they are both familiar but quite different sub-categories within the overall dairy category and have quite different levels of availability and consumer acceptance (milk—readily available, well accepted; cheese—less readily available, lower acceptance). Meat (100% and 33% plant-based) were chosen because meat protein is the most highly targeted protein for replacement, but percentage replacement can influence acceptance and willingness to consume. Meat hybrids like PB Meat 33% offer a more sustainable food alternative for consumers who consider meat to be an essential and integral element of their daily diet [ 105 ]. Lastly, fish was chosen as it is a more novel food category for plant-based products and identified as a niche for PB food innovations by Alcorta et al. [ 106 ].

To provide a common frame of reference, participants read a short text (written by authors SRJ and DG) before answering questions about the focal foods. It read: “Our current approaches to food production and our consumption levels are global problems because they drive climate change and environmental degradation. Animal farming is particularly damaging for the environment, and to reduce environmental impacts we must change the way we eat—increasing our consumption of plant foods while substantially limiting our intake from animal sources. To support this transition, interest has centered on those plant foods that are good sources of proteins—soybeans, nuts, peas, and some grains—and can provide a nutritionally sound alternative to foods from animals, while also being suitable for the growing number of people who do not, or cannot, eat certain animal-sourced foods (e.g., vegetarians/vegans, people who have a dairy allergy or are lactose intolerant). In the past decade, more and more of these 100% plant-based foods have become available in the [United States/Australia/Singapore/India]. PB “milks” made from, for example, soy, almonds, oats, and even cashew nuts are fairly familiar now, and plant-based “yoghurt” and “cheese” are no longer uncommon. PB “meat”, “fish”, and “seafood” are much more novel. Besides replacing foods from animals with plant-based foods, or creating blends of animal-plant foods, there is also considerable interest in developing alternative sources of animal-derived proteins. These include insects.”

The text continued to describe other novel types of foods/food technologies ( Part S2 of Supplementary Materials has the text in full). The reason was to provide background information for other foods/food technologies also included in the survey but not relevant for the present research ( Part S2 of Supplementary Materials lists these other foods).

2.3. Empirical Procedures

2.3.1. stimulus evaluation.

Stimulus evaluation proceeded in two parts. First, the plant-based food names were assessed using two check-all-that-apply (CATA) question [ 107 ], pertaining to (i) emotional and cognitive product perceptions, and (ii) situational use product perceptions. This evaluation proceeded sequentially and both CATA questions were completed before the next food name appeared. Randomization of stimuli and terms were used within CATA questions and across participants.

Drawing on a general vocabulary [ 108 ], the CATA question relating to emotional and cognitive product conceptualizations included 16 terms: ‘adventurous’, ‘boring’, ‘classy’, ‘comforting’, ‘dissatisfied’, ‘easygoing’, ‘energetic’, ‘enthusiastic’, ‘feminine’, ‘happy’, ‘inspiring’, ‘nervous’, ‘passive’, ‘powerful’, ‘pretentious’, ‘sophisticated’, ‘tense’, ‘uninspired’, ‘unique’, and ‘youthful’. The CATA question relating to situational use included 8 terms: ‘When I want something I like’, ‘When I feel like trying something new’, ‘To move my diet in a more sustainable direction’, ‘When I want something healthy’, ‘As part of meals that I post on social media’, ‘To set a good example to those around me’, ‘As a regular part of my diet’, and ‘As part of easy and convenient meals’. These were developed to address aspects of pleasure, health, environmental concern, social status, fit to diet and convenience, and drew in part on extant literature [ 109 ]. The suitability of CATA questions for measuring perceived situational appropriateness was previously demonstrated, for example, by Jaeger et al. [ 110 ]. When answering each of these CATA questions, participants were instructed to “Please think about this [stimulus name]. Select all the words that apply.”

The second part of the stimulus evaluation obtained stated willingness to consume, which was measured using the question: “How often would you consume the following foods and beverages?” and a fully labelled 9-pt category scale with anchors: 1 = ‘Never or less than once yearly’, 2 = ‘2–3 times a year’, 3 = ‘Every 2–3 months’, 4 = ‘Once every month’, 5 = ‘1–3 times per month’, 6 = ‘Once every week’, 7 = ‘2–4 times per week’, 8 = ‘5–6 times per week’, and 9 = ‘Once daily or more often’ [ 109 , 111 ]. Stimulus presentation order was randomized.

2.3.2. Psychographic Variables and Dietary Habit

Responses to psychographic variables were obtained after stimulus evaluation. The scales included in all countries were Food Neophobia (FN) [ 112 ], Food Technology Neophobia (FTN) [ 113 , 114 ] and environmental concern (ENV) [ 115 ]. The 10-item food neophobia scale is widely used to capture consumers’ stable propensity to avoid novel and unfamiliar foods (e.g., ‘I don’t trust new foods’). Across 13 items, FTN measured consumers’ fears of novel food technologies (e.g., ‘new food technologies are something I am uncertain about’ and ‘it can be risky to switch to new food technologies too quickly’). Based on a recent review of scales to measure concern for the environment, a composite scale was created combining four items from each of three existing scales [ 116 , 117 , 118 ] seeking to mitigate criticisms of existing scales. The constructed scale included 12 items (e.g., ‘If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe’, ‘I am worried about future children’s chance of living in a clean environment’, and ‘We shouldn’t worry about environmental problems because science and technology will solve them before very long), which are given in full in Part S3 of Supplementary Materials .

All responses were obtained on fully labelled 7-point Likert scales with anchors: ‘Disagree strongly’ (1), ‘Disagree moderately’ (2), ‘Disagree slightly’ (3), ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ (4), ‘Agree slightly’ (5), ‘Agree moderately’ (6), and ‘Agree strongly’ (7). Participants were instructed to indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with each of the statements. Within the psychographic scales, statement order was randomized across participants.

Dietary habit was categorized using a question from De Backer and Hudders [ 119 ] with nine available options. Participants were classified as Omnivores (no limitation on consumption of meat and fish), Flexitarians (consciously limits quantity of either all types or specific types of meat) or Vegetarians (who completely avoid the consumption of meat and fish).

2.3.3. Data Collection

The survey was conducted in English and was appropriate given the status of this language as lingua franca in all four countries. High proficiency in English as an eligibility criterion further ensured that participants had the necessary language skills to complete the survey.

Demographic and socio-economic information was obtained either at the start of the survey (for quota sampling purposes) or at the end of the survey.

Data collection took place in December 2021 and January 2022, following careful revision of test links and evaluation of responses from ~10% of the total sample in each country to ensure that the survey performed as expected.

The data were obtained as part of a survey that also included other questions, which are not described further due to lack of relevance for the present research. Participants completed the task from a location of their own choosing, using a desktop or laptop computer.

Drawing on Jaeger and Cardello [ 120 ] who identify factors affecting data quality in online questionnaires, data-driven exclusion criteria were implemented relating to completion time and straight-line responding (see Part S4 of Supplementary Materials for details).

2.4. Data Analysis

All analyses were performed in XLSTAT [ 121 ], using a 5% significance level for inference tests.

2.4.1. Willingness to Consume

As directed by Obj. 1 and the exploration of consumers’ WTC for PB foods, an ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons was performed with WTC ratings as the dependent variable and PB food category as the explanatory variable. In a second step, violin plots [ 122 ] were drawn to show the heterogeneity of the distributions of WTC ratings between PB food categories.

2.4.2. Emotional, Conceptual and Situational Use Terms

Extending the analyses linked to Obj. 1, consumer-derived profiling of the PB food categories was explored. Upon confirming that each CATA term was discriminant via Cochran’s Q tests, Correspondence Analysis was applied on the PB category x term contingency tables [ 123 ].

To determine the effect of each term on the WTC ratings, penalty/lift analysis was performed [ 123 ]. The purpose is to determine for each of the PB food categories which terms positively or negatively affect WTC. The change in WTC for each PB food is calculated and a student’s test between the average WTC when the term is checked and when the term is unchecked to establish if this difference is significantly different from zero.

2.4.3. Consumer Segmentation

To perform consumer segmentation (Obj. 2), an agglomerative hierarchical clustering based on the WTC scores across the 5 PB food categories was used. This cluster analysis was computed with the Euclidean distance and Ward’s criterion [ 124 ]. To build clusters that discriminated between the PB food categories, a centering of the WTC scores by subject was carried out beforehand. The number of clusters to retain was determined by visual inspection of the dendrogram, where a significant change of within-cluster variation highlighted a merge of two heterogeneous clusters.

To visualize differences in the WTC patterns between the clusters, the matrix of clusters x PB foods centers of gravity was calculated and submitted to a PCA based on the covariance matrix. Cluster confidence ellipses (95%) were computed by bootstrapping [ 125 ].

An ANOVA measuring the PB food category effect on the WTC scores was performed for each cluster separately. As the sample size differed greatly between clusters, effect sizes (η 2 ) were used in addition to p -values as indicators of degree of product discrimination within each cluster. ANOVAs to measure the cluster effect on each of the PB food categories separately, as well as on the category means were also computed and followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons.

Per Obj. 3, the final step was to perform penalty/lift analysis within each of the retained clusters to determine the impact on average WTC scores on CATA term selection for each of the 5 PB food categories. Within clusters, the analysis was performed in the same manner as described in Section 2.4.2 .

2.4.4. Psychographic and Socio-Demographic Variables

For trait scales (FN, FTN) and ENV concern, summed scores for each participant were calculated across all scale items (following reverse coding as needed). Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded the 0.7 threshold for internal reliability [ 126 ].

To investigate whether the clusters were influenced by psychographic and/or socio-demographic characteristics, an analysis of the proportions of presence of different variables was performed: country, age, gender, education, and dietary preferences.

3.1. Aggregate Level Findings

3.1.1. willingness to consume.

The first objective of the present research was to examine consumers’ willingness to consume plant-based protein within a number of distinct food categories (Obj. 1). Across all countries and PB food categories, slightly more than one-third of all willingness to consume (WTC) ratings (37.3%) were for the response option ‘never or less than once yearly’ (see also Figure 1 A), while 9.6% were for the two response options indicating willingness to consume most frequently (‘5–6 times per week’ and ‘once daily or more often’). Figure 1 B shows the mean WTC ratings by PB food category for all participants across countries. The PB Milk category had the highest WTC (between ‘once every month’ and ‘1–3 times per month’) followed, in order, by PB Cheese , PB Meat and PB Meat 33% . The food category for which there was, on average, the lowest WTC was PB Fish (all between ‘every 2–3 months’ and ‘once every month’). Part S5 of Supplementary Materials shows that similar preference ordering was obtained when summarizing and analyzing the data non-parametrically.

Mean willingness to consume (WTC) ratings for aggregate sample across 2494 consumers in USA, Australia, Singapore and India shown for the five plant-based (PB) food categories included in the research. ( A ) Violin plot of WTC ratings for PB food categories, with median and interquartile range; ( B ) Mean WTC ratings, with standard error. WTC was measured on a 9-point scale (1 = ’Never or less than once yearly’, 5 = ‘1–3 times per month’, 9 = ‘Once daily or more’). In ( B ), PB food categories with different letters following Tukey’s post hoc test are significantly different at the 5% level of significance.

Heterogeneity in WTC ratings for PB food categories was revealed in Figure 1 A which shows violin plots for each of the PB food categories. It was particularly obvious that WTC ratings with notably higher than the mean and median values were provided by a modest proportion of participants. This pointed to heterogeneity in consumers’ WTC ratings and paved the way for the second objective of the present research (Obj. 2).

3.1.2. Emotional and Conceptual Product Associations

According to Cochran’s Q tests, the five PB food categories were significantly differentiated ( p < 0.05) on all emotional and conceptual terms except ‘passive’ ( p = 0.21). Overall, the most frequently used terms were ‘sophisticated’ (22%) and ‘happy’ (20%), while ‘tense’ (6%) and ’energetic’ (7%) were least frequently used ( Part S6 of Supplementary Materials has full details). Figure 2 A shows a biplot of the two first dimensions after CA, with a dominating first dimension (87.7%) ( Part S7 of Supplementary Materials shows the average stimulus positions with 95% confidence intervals). PB Milk was separated from the other PB food categories on the first dimension and most strongly associated with ‘energetic’ and ‘powerful’, and least strongly associated with ‘sophisticated’. The second dimension (8.7%) separated PB Cheese from PB Fish , with the former being significantly more frequently associated with ‘feminine’ and ‘classy’, while negative emotions – ‘dissatisfied’, ‘tense’ and ‘nervous’ were dominant for PB Fish . The associations for PM Meat and PM Meat 33% were very similar.

Results linked to emotional and conceptual product associations for aggregate sample across 2494 consumers in USA, Australia, Singapore and India shown for aggregate sample the five plant-based (PB) food categories included in the research. ( A ) Plot of the first two dimensions following Correspondence Analysis; ( B ) Impact on average willingness to consume (WTC) based on Penalty/Lift analysis. In ( A ), PB food categories are shown in bold and italic font. In ( B ), grey font used for terms where change in WTC is not significantly different from zero at the 5% level of significance.

Penalty/Lift analysis was used to identify the relationships between stimulus characterization and WTC, with Figure 2 B showing that selection of ‘happy, ‘comforting’ and ‘energetic’ was associated with a positive change in WTC of more than one scale point, and that selection of ‘boring’, ‘uninspired’ and ‘dissatisfied’ was associated with a negative change in WTC of more than one scale point. Smaller positive WTC changes (0.5 to 1 scale point) were observed for many positive and conceptual terms, while negative WTC change of a similar magnitude was associated with ‘nervous’.

3.1.3. Situational Use Product Associations

For situational use associations, the PB food categories were significantly differentiated ( p < 0.05) according to Cochran’s Q tests (except for ‘as part of meals that I post on social media’, p = 0.18). Across all stimuli, the most frequent situational use associations were ‘when I feel like trying something new’ (43%) and When I want something healthy’ (33%), while the least frequent association was ‘as part of meals that I post on social media’ (12%). Figure 3 A shows a biplot of the two first dimensions after CA, with a dominating first dimension (82.5%) ( Part S7 of Supplementary Materials shows the average stimulus positions with 95% confidence intervals). PB Milk was separated from the other four PB food categories on Dimension 1 and was the PB category most strongly associated with ‘as a regular part of my diet’ and least frequently associated with ‘when I feel like trying something new’. The second dimension (12.7%) separated PB Meat and PB Cheese , and the former was significantly more frequently associated with ‘to set a good example to those around me’ and significantly less associated with ‘when I want something I like’.

Results linked to situational use product associations for aggregate sample across 2494 consumers in USA, Australia, Singapore and India shown for the five plant-based (PB) food categories included in the research. ( A ) Plot of the first two dimensions following Correspondence Analysis; ( B ) Impact on average willingness to consume (WTC) based on Penalty/Lift analysis. In ( A ), PB food categories are shown in bold and italic font. In ( B ), change in WTC is significantly different from zero ( p < 0.05) for all terms.

The Penalty/Lift analysis ( Figure 3 B) revealed that a positive WTC change greater than one scale point was only found for ‘As a regular part of my diet’. Smaller positive, but still significant ( p < 0.05) changes in WTC were found for all other situational use situations. The exception was ‘When I feel like trying something new’. On average, selection of this use situation reduced WTC by about 0.2 WTC scale points.

3.2. Consumer Segmentation Based on Willingness to Consume

Directed by Objective 2, hierarchical cluster analysis of WTC ratings was performed on the total sample of 2494 people across the four countries. Based on the dendrogram ( Part S8 of Supplementary Materials ), a 7-cluster solution was retained. With the way of constructing the clusters being ascending, the dendrogram showed that the first notable “jump” in within-cluster variation took place between a 7-cluster and a 6-cluster solution. Moreover, the number of participants in each of the retained clusters was greater than 100, which ensured that the clusters were both homogeneous and large.

Among the 7 retained clusters there was one large cluster (1382 people; 55.4% of total sample) which could be described as PB category non-discriminators. Additionally, there was six smaller clusters (127 to 296 people per cluster; 44.6% of total sample) with distinct patterns of WTC ratings for the different PB food categories. Because the individual clusters had nuanced and complex WTC profiles for PB food category, arbitrary cluster naming (Cluster 1 to Cluster 7) was used to simplify the presentation of results and retain focus on the existence of multiple minor clusters rather than their specific individual WTC profiles.

The demographic profiles of the 7 clusters are summarized in Table 1 . There were few between-cluster differences in relation to biological sex, age group or level of education. Participants from India were notably overrepresented in Cluster 2 (63.8%), and to a lesser degree in Cluster 4 (44.6%). Other country differences among clusters were minor, with the percentage distributions ranging between 10% and 34% (relative to 25% for even distributions by country). When considering self-declared dietary preferences, omnivores were overrepresented in Clusters 1, 3 and 7 (60–68%). Flexitarians were more evenly distributed, but with a tendency to higher representation in Clusters 4 and 6 (46–48%). Compared to the overall sample, vegans were strongly overrepresented in Cluster 2 (29%), which is likely attributable to the high percentage of consumers from India falling into Cluster 2. Cluster differences for FN, FTN and environmental concern were minor and not clearly related to WTC for PB food categories.

3.2.1. PB Category Non-Discriminators: Cluster 1

In the retained solution, there was one large group of consumers (55.4%, n = 1382) whose WTC responses revealed these people to be PB category non-discriminators. While significantly different, the average WTC ratings for the five PB food categories in this cluster were very similar and the effect size was ‘nil’ (Cluster 1, Table 2 ).

Mean willingness to consume (WTC) ratings by plant-based (PB) food category for the 7-cluster solution based on the aggregate sample ( n = 2494).

| Cluster | PB Foods (Average) | PB Milk | PB Cheese | PB Fish | PB Meat | PB Meat 33% | -Value (by Cluster) | Effect Size (by Cluster) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (55.4%) | 3.2 C | 3.1 B | 3.0 B | 3.2 AB | 3.4 A | 3.2 AB | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| 2 (5.1%) | 4.1 B | 7.3 A | 6.4 B | 2.2 CD | 1.9 D | 2.6 C | <0.0001 | 0.68 |

| 3 (8.6%) | 4.7 AB | 6.6 A | 3.4 D | 4.3 C | 4.1 C | 4.9 B | <0.0001 | 0.19 |

| 4 (11.9%) | 4.4 AB | 5.1 B | 5.8 A | 3.9 C | 3.7 C | 3.6 C | <0.0001 | 0.14 |

| 5 (6.0%) | 3.0 C | 7.6 A | 2.3 B | 1.7 C | 1.7 C | 1.9 BC | <0.0001 | 0.72 |

| 6 (5.7%) | 4.9 A | 6.9 A | 5.1 C | 3.9 D | 6.1 B | 2.5 E | <0.0001 | 0.37 |

| 7 (7.3%) | 4.1 B | 3.9 B | 4.9 A | 2.4 C | 3.9 B | 5.5 A | <0.0001 | 0.20 |

WTC was measured on a 9-point scale (1 = ’Never or less than once yearly’, 5 = ‘1–3 times per month’, 9 = ‘Once daily or more’). Cluster sizes are given as % of the total sample ( n = 2494). Standard errors around WTC means were between 0.1 and 0.2 for all clusters and all PB food categories). The last two columns show p -value and effect size (η 2 ) following analysis of variance within clusters. Results from Tukey’s post hoc tests are shown, and within rows, PB food categories with same capital letters are not significant at the 5% level of significance.

A follow-up cluster analysis identified three sub-groups of consumers within Cluster 1 ( Part S9 of Supplementary Materials includes a dendrogram and a plot of WTC means). Although each of these three sub-groups were non-discriminating among food categories, they differed significantly in the magnitude of their stated WTC. The largest group ( n = 865, 34.7% of total sample) gave low WTC ratings to all five PB food categories (between ‘2–3 times a year’ and ‘never or less than once a year’). The smallest group ( n = 203, 8.1% of total sample) gave higher WTC ratings across food categories (between ‘once every month’ and ‘every 2–3 months’), while the third group ( n = 314, 12.6% of total sample) gave high WTC ratings to all PB food categories (around ‘2–4 times a week’).

Part S10 of Supplementary Materials has the demographic profiles for the Cluster 1 sub-groups and it fits that Group 2 which had the lowest average WTC across the five PB food categories (between ‘never or less than once yearly’ and ‘2–3 times a year’) comprised more older people (60%), more people with lower educational attainment (46.5%), was dominated by self-declared omnivores (73.4%) and was most food neophobic (38.4) and food technology neophobic (60.2). This was contrasted with Group 3 where average WTC was highest. In this group, people from the younger age group (18 to 45 years old) were in the majority (65.3%), as were those who had higher educational attainment (70.7%). Consumers from India were also relatively overrepresented (39.2%) in this latter group.

3.2.2. PB Category Discriminators: Clusters 2 to 7

Each of the 6 smaller segments had distinct WTC patterns by PB food category, and based on effect size, the PB category differences were largest in Cluster 5 (η 2 = 0.72) and Cluster 2 (η 2 = 0.68) ( Table 2 ). In Cluster 5 ( n = 150, 6.0% of total sample), average WTC ratings were high for PB Milk (between ‘2–4 times per week’ and ‘5–6 times per week’) and much lower for all other PB food categories. Among these consumers, PB Cheese had the highest WTC, followed by PB Meat 33% and then 100% PB Meat and PB Fish . In Cluster 2 ( n = 127, 5.1% of total sample), the high average WTC for PB Milk was similar to Cluster 5. Furthermore, in this cluster WTC for PB Cheese was also high (between ‘once every week’ and ‘2–4 times every week’). In a further parallel to Cluster 5, PB Meat 33% was the PB food category with the third highest average WTC rating (between ‘every 2–3 months’ and ‘2–3 times a year’). PB Meat and PB Fish had the lowest average WTC (around ‘2–3 times a year’). These distinct WTC profiles are seen in Figure 4 which presents two-dimensional biplots following Principal Components Analysis of mean WTC ratings by PB product category across the six category discriminating clusters ( Figure 4 A plots PC1 vs. PC2; Figure 4 B plots PC1 vs. PC3). Briefly, PC1 and PC2 separated, respectively, PB Milk and PB Cheese from the other PB food categories, while PC3 separated the two variants of PB Meat .

Two-dimensional biplots following Principal Components Analysis of mean willingness to consume (WTC) ratings for PB food categories in the six PB category discriminating clusters (Cluster 2 to Cluster 7). Confidence ellipses (95%) around average cluster positions were obtained by bootstrapping. ( A ) PC1 vs. PC2; ( B ) PC1 vs. PC3. ( A , B ), PB food categories are shown in bold and italic font.