An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Microbiol Biol Educ

- v.19(3); 2018

A Systematic Approach to Teaching Case Studies and Solving Novel Problems †

Carolyn a. meyer.

1 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523

Heather Hall

Natascha heise, karen kaminski.

2 School of Education, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523

Kenneth R. Ivie

Tod r. clapp, associated data.

Both research and practical experience in education support the use of case studies in the classroom to engage students and develop critical thinking skills. In particular, working through case studies in scientific disciplines encourages students to incorporate knowledge from a variety of backgrounds and apply a breadth of information. While it is recognized that critical thinking is important for student success in professional school and future careers, a specific strategy to tackle a novel problem is lacking in student training. We have developed a four-step systematic approach to solving case studies that improves student confidence and provides them with a definitive road map that is useful when solving any novel problem, both in and out of the classroom. This approach encourages students to define unfamiliar terms, create a timeline, describe the systems involved, and identify any unique features. This method allows students to solve complex problems by organizing and applying information in a logical progression. We have incorporated case studies in anatomy and neuroanatomy courses and are confident that this systematic approach will translate well to courses in various scientific disciplines.

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing emphasis in pedagogical research on encouraging critical thinking in the classroom. The specific mental processes and behaviors involved require the individual to engage in reflective and purposeful thinking. Critical thinking encompasses the ability to examine ideas, make decisions, and solve problems ( 1 , 2 ). The skills necessary to think critically are essential for learners to evaluate multiple perspectives and solve novel problems in the classroom and throughout life. Career success in the 21st century requires a complex set of workforce skills. Current labor market assessments indicate that by the year 2020, the majority of occupations will require workers to display cognitive skills such as active listening, critical thinking, and decision making ( 3 , 4 ). In particular, current studies show that the US economy is impacted by a deficit of skilled workers able to solve problems and transfer learning to any unique situation ( 3 ).

The critical thinking skills necessary to tackle novel problems can best be addressed in higher education institutions ( 5 , 6 ). Throughout education, and specifically in college courses, students tend to be required to regurgitate knowledge through a myriad of multiple-choice exams. Breaking this habit and incorporating critical thinking can be difficult for students. While the ability to recite information is helpful for establishing base knowledge, it does not prepare students to tackle novel problems. Ideally, the objective of any course is to encourage students to move beyond recognition of knowledge into its application ( 7 ). Considering this, the importance of critical thinking is widely accepted; however, there has been some debate in educational research regarding how to teach these skills ( 8 ). Research has demonstrated that students show significant improvements in critical thinking as a result of explicit methods of instruction in related skills ( 9 , 10 ). Explicit instruction provides a protocol on how to approach a problem. By establishing the necessary framework to work through unfamiliar details, we enable students to independently solve complex problems.

These skills, which are important in every facet of the workforce, are vital for students in the sciences ( 10 , 11 ). Here, we discuss a specific process that teaches students a systematic approach to solving case studies in the anatomical sciences. Case studies are a popular method to encourage critical thinking and engage students in the learning process ( 12 ). While the examples described here are specifically designed to be implemented in anatomy and neuroanatomy courses, this platform lends itself to teaching critical thinking skills across scientific disciplines. This four-step approach encourages students to work through four separate facets of a problem:

- Define unfamiliar terms

- Create a timeline associated with the problem

- Describe the (anatomical) systems involved

- Identify any unique features associated with the case

Often, students start by trying to plug in memorized facts to answer a complicated question quickly. With the four-step approach, students learn that before “solving” the case study, they must analyze the information presented in the case. The case studies implemented are anatomically-based case studies that emphasize important structural relationships. The case may include terminology with which the students are not familiar. They therefore begin by identifying and defining unfamiliar terms. They then specify the timeline in which the problem occurred. Establishing a timeline and narrowing the focus can be critical when considering the relevant pathology. Students must then describe the anatomical systems involved (e.g., musculoskeletal or circulatory), and finally list any additional unique features of the case (e.g., lateral leg was struck or patient could not abduct the right eye). By dissecting the details along the lines of these four categories, students create a clear roadmap to approach the problem. Case studies with a clinical focus are complex and can be overwhelming for unpracticed students. However, teaching students to follow this systematic approach gives them the tools to begin to carefully dismantle even the most convoluted problem.

Intended audience

This approach to solving case studies has been applied in undergraduate courses, specifically in the sciences. This curriculum is currently utilized in both human gross anatomy and functional neuroanatomy capstone courses. While it is ideal to implement this process in a course that runs in parallel with a lecture-heavy course, it can also be utilized with case studies in a typical lecture class.

Anatomy-based case studies lend themselves well to this problem-solving approach due to the complexities of clinical problems. However, we believe with an appropriately designed case study, this model of teaching critical thinking can easily be expanded to any discipline. This activity encourages critical thinking and engages students in the learning process, which we believe will better prepare them for professional school and careers in the sciences.

Prerequisite student knowledge

Required previous student knowledge only extends to that which students learn through the related course taken previously or concurrently. Application of this approach in different classroom settings only requires that students have a basic understanding of the material needed to solve the case study. As such, the case study problem and questions should be built around current topics being studied in the classroom.

Using unfamiliar words teaches students to identify important information. This encourages integration of information and terminology, which can be critical for understanding anatomy. Simple terms, like superficial or deep, guide discussions about anatomical relationships. While students may be able to recite the definitions of these concepts, applying that information to a case study requires integrating the basic definition with an understanding of the relevant anatomy. Specific prerequisite knowledge for the sample case study is detailed in Appendix 1 .

Learning time

This process needs to be learned and practiced over the course of a semester to ensure long-term retention. With structured and guided attempts, students will be able to implement this approach to solving case studies in one 50-minute class period ( Table 1 ). The course described in this study is a capstone course that meets once weekly. Each 50-minute class period centers around working through a case study. As some class sessions are reserved for other activities, students complete approximately 10 case studies during the semester. Students begin to show increased confidence with this method within a few weeks and ultimately are able to integrate this approach into their critical thinking skillset by the end of the semester. Presentation of the case study, individual or small group work, and class discussion are all achieved in one standard class session ( Table 1 ). The current model does not require student work prior to the class meeting. However, because this course is taken concurrently with a related, content-heavy lecture component, students are expected to be up to date on relevant material. Presenting the case study in class to their peers encourages students to work through the systematic approach we describe here. Each case study is designed to correlate with current topics from the lecture-based course. Following the class period, students are expected to complete a written summary of the discussed case study. The written summary should include a detailed explanation of the approach they utilized to solve the problem, as well as a definitive solution. Written summaries are to be completed two days after the original class period.

Anticipated in-class time to implement this model.

| Activity | ApproximateTime Anticipated |

|---|---|

| Presentation of the case study | 5 minutes |

| Individual or small group work | 15 minutes |

| Class discussion | 30 minutes |

Learning objectives

This model for teaching a systematic approach to solving case studies provides a framework to teach students how to think critically and how to become engaged learners when given a novel problem. By mastering this technique, students will be able to:

- Recognize words and concepts that need to be defined before solving a novel problem

- Recall, interpret, and apply previous knowledge as it relates to larger anatomical concepts

- Construct questions that guide them through which systems are affected, the timeline of the pathologies, and what is unique about the case

- Formulate and justify a hypothesis both verbally and in writing

As a faculty member, it can be challenging to create appropriate case studies when developing this model for use in a specific classroom. There are resources that provide case studies and examples that can be tailored to specific classroom needs. The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (University at Buffalo) can be a useful tool. The ultimate goal of this model is to teach an approach to problem solving, and a properly designed case study is crucial to success. To build an effective case study, faculty must include sufficient information to provide students with enough base knowledge to begin to tackle the problem. This model is ideal in a course that pairs with a lecture-heavy component, utilized in either a supplementary course or during a recitation. The case study should be complex and not quickly solved. An example of a simplified case study utilized in Human Gross Anatomy is detailed in Appendix 1 .

This particular case study encourages students to think through the anatomy of the lateral knee, relevant structures in this area, and which muscle compartments may be affected based on movement disabilities within the case. While more complex case studies can certainly be developed for the Neuroanatomy course through Clinical Case Studies, this case study provides a good example of a problem to which students cannot immediately provide the answer. They must think critically through the four-step process to identify the “diagnosis” for this patient.

This approach to solving case studies can be integrated into the classroom with no special materials. However, we use a Power-Point presentation and personal whiteboards (2.5’ × 2’) to both improve delivery of the case study and facilitate small group discussion, respectively. The Power-Point presentation is utilized by faculty to assist in leading the classroom discussion, prompting student responses and projecting relevant images. As the faculty member is presenting the case study during the first five minutes of class ( Table 1 ), the wording of the case study can be displayed on the PowerPoint slide as a reference while students take notes.

Faculty instructions

It is helpful to first present an overview of the approach and to solve a case study together as a class. We recommend giving students a lecture describing the benefits of a systematic approach to case studies and emphasizing the four-step approach outlined in this paper. Following this lecture, it is imperative that faculty walk the students through the first case study. This helps to familiarize students with the approach and lays out expectations on how to break down the individual components of the case. During the initial case study, faculty must heavily moderate the discussion, leading students through each step of the approach using the provided Case Study Handout ( Appendix 2 ). In subsequent weeks, students can be expected to show increasing independence.

Following initial presentation of the case study in class, students begin work that is largely independent or done in small groups. This discussion has no grades assigned. However, following the in-class discussion and small group work, students are asked to detail their approach to solving the case study and their efforts are graded according to a set rubric ( Appendix 3 ). This written report should document each step of their thought process and detail the questions they asked to reach the final answer, providing students with a chance for continual self-evaluation on their mastery of the method.

Implementing this model in the classroom should focus not only on the individual student approach, but also on creating an encouraging classroom environment and promoting student participation. Student questions may prompt other student questions, leading to an engaging discussion-based presentation of the case study, which is crucial to increasing confidence among students, as has been seen with the data represented in this paper. When moderating the discussion, it is important that faculty emphasize to students that the most critical goal of the exercise is to learn how to ask the next most appropriate question. The questions should begin with broad concepts and evolve to discussing specific details. Efforts to quickly arrive at the answer should be discouraged.

Students should be randomly assigned to groups of two to three individuals as faculty members moderate small group discussion during class. Randomly assigning students to different groups each week encourages interaction between all students in the class and promotes a collaborative environment. Within their small groups, students should work through the systematic four-step process for solving a novel problem. Students are not assigned specific roles within the group. However, all group members are expected to contribute equally. During this process, it can be beneficial to provide students with a template to follow ( Appendix 2 ). This template guides their discussion and encourages them to use the four-step process. Additionally, each small group is given a white board that they can use to facilitate their small group discussions. Specifically, asking students to write down details of each of the four facets of the problem (definitions, timeline, systems involved, unique features) and how they arrived at these encourages them to commit to their answers. This also ensures they have concrete evidence to support their “diagnosis” and that they have confidence in presenting it to the class. Two or three small groups are chosen randomly each week to present their hypothesis to the class using their whiteboard.

Suggestions for determining student learning

The cadence of the in-class discussion can provide an informal gauge of how students are progressing with their ability to apply the systematic approach. The discussion for the initial case studies should be largely faculty led. Then, as the semester progresses, faculty should step back into a facilitator role, allowing the dialogue to be carried by the students.

Additionally, requiring students to write a detailed summary of their approach to the problem provides a strong measure of student learning. While it is important for students to document their final “diagnosis” or solution to the problem, the focus of this assignment is primarily on the process and the series of relevant questions the student used to arrive at the answer. These assignments are graded according to a set rubric ( Appendix 3 ).

Sample data

The following excerpt is from a student who showed marked improvement over the course of the semester in implementing this approach to solving case studies. The initial submission for the case study write-up was rudimentary, did not document the thought process through appropriate questions, and lacked an in-depth explanation to demonstrate any critical thinking. By the end of the semester, this student documented a logical thought progression through this four-step approach to solving the case study. This student, additionally, detailed the questions that led each stage of critical thinking until a “diagnosis” was reached (complete sample data are available in Appendix 4 ).

Initial sample

“Given loss of sensory and motor input to left lower limb, right anterior cerebral artery ischemia caused the sensory and motor cortices of the contralateral (left) lower limb to be without blood flow for a short amount of time (last night). The lack of flow led to a fast onset of motor and sensory paresis to limb.”

Final sample

“…the left vestibular nuclei which explains the nystagmus, and the left cerebellar peduncles which carry information that aids in coordinating intention movements. My next question was where in the brainstem are all of these components located together? I narrowed this to the left caudal pons. Finally, I asked which artery supplies the area that was damaged by the lesion? This would be the left anterior inferior cerebellar artery.”

Safety issues

There are no known safety issues associated with implementing this approach to solving case studies.

The primary goal of the model discussed here is to give students a method that uses critical reasoning and helps them incorporate facts into a complete story to solve case studies. We believe that this model addresses the need for teaching the specific skill set necessary to develop critical thinking and engage students in the learning process. By encouraging critical thinking, we begin to redirect the tendency to simply recite a memorized answer. This four-step approach to solving case studies is ideal for the college classroom, as it is easily implemented, requires minimal resources, and is simple enough that students demonstrate mastery within one semester. While it was designed to be used in anatomy and neuroanatomy courses, this platform can be used across scientific disciplines. Outside of the classroom, in professional school and future careers, this approach can help students to break down the details, ask appropriate questions, and ultimately solve any complex, novel problem.

Field testing

This model has been implemented in several courses in both undergraduate and graduate settings. The data and approach detailed here are specific to an undergraduate senior capstone course with approximately 25 students. The lecture-based course, which is required to be taken concurrently or as a prerequisite, provides a strong base of information from which faculty can develop complex case studies.

Evidence of student learning

Student performance on written case study summaries improved over approximately ten weeks of practicing the systematic four-step approach ( Fig. 1 ). As indicated by the data, scores improve and begin to plateau around five weeks, indicating a mastery of the approach. In the spring 2016 semester, a marked drop in scores was observed at week 8. We believe that this reflects a particularly difficult case study that was assigned that week. After observing the overall trend in scores, instructional format was adjusted to provide students with more guidance as they worked through this particular case study.

Grade performance in case study written summaries as measured with the grading rubric throughout the semester. A) Mean (with SD) grade performance in case study write-ups in the spring semester of 2016. B) Mean (with SD) grade performance in case study write-ups in the spring semester of 2017. Overall grade performance in case study written summaries improved throughout the 10 weeks in which this method was implemented in the classroom. Written summaries are graded based on a set rubric ( Appendix 3 ) that assigned a score between 0 and 1 for five different categories. Data represent the mean of students’ scores and the associated standard deviation. Improved student performance throughout the semester indicates progress in successful incorporation of this method to solve a complex novel problem.

After the class session, students were asked to provide a written summary of their findings. A set rubric ( Appendix 3 ) was used to assess students on their ability to apply basic anatomical knowledge as it relates to the timeline, systems involved, and what is unique in each case study. Students were also asked to describe the questions that they had asked in order to reach a diagnosis for the case study. The questions formulated by students indicate their ability to bring together previous knowledge to larger anatomical concepts. In this written summary, students were also required to justify the answer they arrived at in each step of the process. In addition to these four steps, students were assessed on the organization of their paper and whether their diagnosis is well supported.

Although class participation was not formally assessed, the improvements demonstrated in the written assignments were mirrored in student discussions in the classroom. While it is difficult to accurately assess how well students think critically, students demonstrated success in learning this module, which provides the necessary framework for approaching and solving a novel problem.

Student perceptions

Students were asked to answer the open response question, “Describe the process you use to figure out a novel problem or case study.” Responses were anonymized, then coded based on frequency of responses. Responses were collected at the start of the semester, prior to any instruction in the described systematic approach, and again at the end of the semester ( Figs. 2 and and3). 3 ). Overall, student comments indicated that mastering this four-step approach greatly increased their confidence in tackling a novel problem. Below are some sample student responses.

Student responses to a survey regarding their approach to solving a novel problem. Data were collected prior to and following the completion of the spring semester of 2016. A) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the beginning of the semester. B) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the end of the semester. Student responses indicate that following a semester of training in using this method, students prefer to use this four-step systematic approach to solve a novel problem.

Student responses to a survey regarding their approach to solving a novel problem. Data were collected prior to and following the completion of spring semester of 2017. A) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the beginning of the semester. B) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the end of the semester. Student responses indicate that students overwhelmingly utilize this systematic approach when solving a novel problem.

“Rather than being intimidated with a set of symptoms I can’t explain, I’m now able to break them down into simpler questions that will lead me down a path of understanding and accurate explanation.” “I now know how to address an exam question or life problem by considering what is needed to solve it. This knowledge will help me to address each problem efficiently and calmly. As a future nurse, I will benefit from developing a logical and stereotypical approach to solving problems. I have learned to assess my thinking and questioning and modify my approach to problem-solving. While the problems may be different in the future, I am confident that I will be able to efficiently learn from my successes and setbacks and continually improve.” “I’m sure I’ll use this approach when I’m faced with any other novel problem, whether it’s scientific or not. Stepping back and establishing what I know and what I need to find out makes difficult problems a lot more approachable.” “Before, I would look at all the information presented and try to find things that I recognized. Then I would simply ask myself if I knew the answer. Even if I did actually know the answer, I had no formula to make the information understandable, cohesive, or approachable. I now feel far more confident when dealing with novel problems and do not become immediately overwhelmed.”

This approach encourages students to quickly sort through a large amount of information and think critically. Although students can find the novel nature of this method cumbersome in the initial implementation in the classroom, once they become familiar with the approach, it provides a valuable platform for attacking any novel problem in the future. The ability to apply this approach to critical thinking in any discipline was also demonstrated, as is evidenced by the two following student responses.

“When I first thought about this question and when solving case studies I tried to find the answer immediately. I’m good at memorizing information and spitting it back out but not working through an issue and having a method. I definitely have a more successful way to think through complex problems and being patient and coming up with an answer.” “I already use it in many of my other classes and life cases. When I take an exam that is asking a complicated question or is in a long format, I work to break it down like I did in this class and try to find the base question and what the answer may be. It has actually helped significantly.”

Possible modifications

Currently, students are randomly assigned to groups each week. In future semesters, we could improve small group work by utilizing software that helps to identify individual student strengths and assign groups accordingly. Additionally, while students are given flexibility within their small groups, if groups struggle with equality of workload we could assign specific roles and tasks.

We are also using this model in a large class (100 students) and assessing understanding of the case study through instant student response questions (ICLICKER). While this model does not allow for the valuable in-depth classroom discussions, it still presents the approach to students and allows them to begin to implement it in solving complex problems. Preliminary data from these large classes indicate that students initially find the method difficult and cumbersome. Further development and testing of this model in a large classroom will improve its use for future semesters.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Appendix 1: sample case study, appendix 2: case study handout, appendix 3: case study grading rubric, appendix 4: student writing sample, acknowledgments.

Use of anonymized student data and student responses to surveys was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Colorado State University. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

† Supplemental materials available at http://asmscience.org/jmbe

New Model for Solving Novel Problems Uses Mental Map

Summary: The cognitive map allows people to compute on the fly with limited information to solve abstract problems.

Source: UC Davis

How do we make decisions about a situation we have not encountered before? New work from the Center for Mind and Brain at the University of California, Davis, shows that we can solve abstract problems in the same way that we can find a novel route between two known locations — by using an internal cognitive map.

The work is published Aug. 31 in the journal Nature Neuroscience .

Humans and animals have a great ability to solve novel problems by generalizing from existing knowledge and inferring new solutions from limited data. This is much harder to achieve with artificial intelligence.

Animals (including humans) navigate by creating a representative map of the outside world in their head as they move around. Once we know two locations are close to each other, we can infer that there is a shortcut between them even if we haven’t been there. These maps make use of a network of “grid cells” and “place cells” in parts of the brain.

In earlier work, Professor Erie Boorman, postdoctoral researcher Seongmin (Alex) Park, Douglas Miller and colleagues showed that human volunteers could construct a similar cognitive map for abstract information. The volunteers were given limited information about people in a two-dimensional social network, ranked by relative competence and popularity. The researchers found that the volunteers could mentally reconstruct this network, represented as a grid, without seeing the original.

The new work takes the research further by testing if people can actually use such a map to find the answers to novel problems.

Matchmaking entrepreneurs

As before, volunteers learned about 16 people they were told were entrepreneurs, ranked on axes of competence and popularity. They never saw the complete grid, only comparisons between pairs.

They were then asked to select business partners for individual entrepreneurs that would maximize growth potential for a business they started together. The assumption was that an entrepreneur scoring high in competence but low on popularity would be complemented by one with a higher popularity score.

“For example, would Mark Zuckerberg be better off collaborating with Bill Gates or Richard Branson?” Boorman said. (The actual experiment did not use real people.)

While the volunteers were performing the decision task, the researchers scanned their brains with functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI.

If the volunteers were using the grid cells inside their head to infer the answer, that should be measurable with a tailored analysis approach applied to the fMRI signal, Boorman said.

“It turns out the system in the brain does show the signature of these trajectories being computed on the fly,” he said. “It looks like they are leveraging the cognitive map.”

Computing solutions on the fly

In other words, we can take in loosely connected or fragmentary information, assemble it into a mental map, and use it to infer solutions to new problems.

Scientists have considered that the brain makes decisions by computing the value of each choice into a common currency, which allows them to be compared in a single dimension, Park said. For example, people might typically choose wine A over wine B based on price, but we know that our preference can be changed by the food you will pair with the wine.

“Our study suggests that the human brain does not have a wine list with fixed values, but locates wines in an abstract multidimensional space, which allows for computing new decision values flexibly according to the current demand,” he said.

The cognitive map allows for computation on the fly with limited information, Boorman said.

“It’s useful when the decisions are novel,” he said. “It’s a totally new framework for understanding decision making.”

The navigational map in rodents is located in the entorhinal cortex, an “early” part of the brain. The cognitive map in humans expands into other parts of the brain including the prefrontal cortex and posterior medial cortex. These brain areas are part of the default mode network, a large “always on” brain network involved in autobiographical memory, imagination, planning and the theory of mind.

Funding: The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

About this cognition research news

Author: Andy Fell Source: UC Davis Contact: Andy Fell – UC Davis Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Closed access. “ Inferences on a multidimensional social hierarchy use a grid-like code ” by Seongmin A. Park, Douglas S. Miller & Erie D. Boorman. Nature Neuroscience

Inferences on a multidimensional social hierarchy use a grid-like code

Generalizing experiences to guide decision-making in novel situations is a hallmark of flexible behavior. Cognitive maps of an environment or task can theoretically afford such flexibility, but direct evidence has proven elusive.

In this study, we found that discretely sampled abstract relationships between entities in an unseen two-dimensional social hierarchy are reconstructed into a unitary two-dimensional cognitive map in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex.

We further show that humans use a grid-like code in entorhinal cortex and medial prefrontal cortex for inferred direct trajectories between entities in the reconstructed abstract space during discrete decisions. These grid-like representations in the entorhinal cortex are associated with decision value computations in the medial prefrontal cortex and temporoparietal junction.

Collectively, these findings show that grid-like representations are used by the human brain to infer novel solutions, even in abstract and discrete problems, and suggest a general mechanism underpinning flexible decision-making and generalization.

Dogs Using Soundboard Buttons Understand Words

How We Recognize Words in Real-Time

Marmoset Monkeys Use Unique Calls to Name Each Other

Study Links Gene Variations to Brain Changes in Essential Tremor

NTRS - NASA Technical Reports Server

Available downloads, related records.

1st Edition

Unlocking Creativity in Solving Novel Mathematics Problems Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Perspectives and Approaches

- Taylor & Francis eBooks (Institutional Purchase) Opens in new tab or window

Description

Unlocking Creativity in Solving Novel Mathematics Problems delivers a fascinating insight into thinking and feeling approaches used in creative problem solving and explores whether attending to ‘feeling’ makes any difference to solving novel problems successfully. With a focus on research throughout, this book reveals ways of identifying, describing and measuring ‘feeling’ (or ‘intuition’) in problem-solving processes. It details construction of a new creative problem-solving conceptual framework using cognitive and non-cognitive elements, including the brain’s visuo-spatial and linguistic circuits, conscious and non-conscious mental activity, and the generation of feeling in listening to the self, identified from verbal data. This framework becomes the process model for developing a comprehensive quantitative model of creative problem solving incorporating the Person, Product, Process and Environment dimensions of creativity. In a world constantly seeking new ideas and new approaches to solving complex problems, the application of this book’s findings will revolutionize the way students, teachers, businesses and industries approach novel problem solving, and mathematics learning and teaching.

Table of Contents

Carol R. Aldous , BSc (Hons) developmental genetics, PhD (mathematics education and creative problem solving) is a senior lecturer in science and mathematics education at Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia. She leads a South Australian government-funded STEM industry engagement project and passionately researches the role of creativity in problem solving.

About VitalSource eBooks

VitalSource is a leading provider of eBooks.

- Access your materials anywhere, at anytime.

- Customer preferences like text size, font type, page color and more.

- Take annotations in line as you read.

Multiple eBook Copies

This eBook is already in your shopping cart. If you would like to replace it with a different purchasing option please remove the current eBook option from your cart.

Book Preview

The country you have selected will result in the following:

- Product pricing will be adjusted to match the corresponding currency.

- The title Perception will be removed from your cart because it is not available in this region.

40 problem-solving techniques and processes

All teams and organizations encounter challenges. Approaching those challenges without a structured problem solving process can end up making things worse.

Proven problem solving techniques such as those outlined below can guide your group through a process of identifying problems and challenges , ideating on possible solutions , and then evaluating and implementing the most suitable .

In this post, you'll find problem-solving tools you can use to develop effective solutions. You'll also find some tips for facilitating the problem solving process and solving complex problems.

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, 54 great online tools for workshops and meetings, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps.

- 18 Free Facilitation Resources We Think You’ll Love

What is problem solving?

Problem solving is a process of finding and implementing a solution to a challenge or obstacle. In most contexts, this means going through a problem solving process that begins with identifying the issue, exploring its root causes, ideating and refining possible solutions before implementing and measuring the impact of that solution.

For simple or small problems, it can be tempting to skip straight to implementing what you believe is the right solution. The danger with this approach is that without exploring the true causes of the issue, it might just occur again or your chosen solution may cause other issues.

Particularly in the world of work, good problem solving means using data to back up each step of the process, bringing in new perspectives and effectively measuring the impact of your solution.

Effective problem solving can help ensure that your team or organization is well positioned to overcome challenges, be resilient to change and create innovation. In my experience, problem solving is a combination of skillset, mindset and process, and it’s especially vital for leaders to cultivate this skill.

What is the seven step problem solving process?

A problem solving process is a step-by-step framework from going from discovering a problem all the way through to implementing a solution.

With practice, this framework can become intuitive, and innovative companies tend to have a consistent and ongoing ability to discover and tackle challenges when they come up.

You might see everything from a four step problem solving process through to seven steps. While all these processes cover roughly the same ground, I’ve found a seven step problem solving process is helpful for making all key steps legible.

We’ll outline that process here and then follow with techniques you can use to explore and work on that step of the problem solving process with a group.

The seven-step problem solving process is:

1. Problem identification

The first stage of any problem solving process is to identify the problem(s) you need to solve. This often looks like using group discussions and activities to help a group surface and effectively articulate the challenges they’re facing and wish to resolve.

Be sure to align with your team on the exact definition and nature of the problem you’re solving. An effective process is one where everyone is pulling in the same direction – ensure clarity and alignment now to help avoid misunderstandings later.

2. Problem analysis and refinement

The process of problem analysis means ensuring that the problem you are seeking to solve is the right problem . Choosing the right problem to solve means you are on the right path to creating the right solution.

At this stage, you may look deeper at the problem you identified to try and discover the root cause at the level of people or process. You may also spend some time sourcing data, consulting relevant parties and creating and refining a problem statement.

Problem refinement means adjusting scope or focus of the problem you will be aiming to solve based on what comes up during your analysis. As you analyze data sources, you might discover that the root cause means you need to adjust your problem statement. Alternatively, you might find that your original problem statement is too big to be meaningful approached within your current project.

Remember that the goal of any problem refinement is to help set the stage for effective solution development and deployment. Set the right focus and get buy-in from your team here and you’ll be well positioned to move forward with confidence.

3. Solution generation

Once your group has nailed down the particulars of the problem you wish to solve, you want to encourage a free flow of ideas connecting to solving that problem. This can take the form of problem solving games that encourage creative thinking or techniquess designed to produce working prototypes of possible solutions.

The key to ensuring the success of this stage of the problem solving process is to encourage quick, creative thinking and create an open space where all ideas are considered. The best solutions can often come from unlikely places and by using problem solving techniques that celebrate invention, you might come up with solution gold.

4. Solution development

No solution is perfect right out of the gate. It’s important to discuss and develop the solutions your group has come up with over the course of following the previous problem solving steps in order to arrive at the best possible solution. Problem solving games used in this stage involve lots of critical thinking, measuring potential effort and impact, and looking at possible solutions analytically.

During this stage, you will often ask your team to iterate and improve upon your front-running solutions and develop them further. Remember that problem solving strategies always benefit from a multitude of voices and opinions, and not to let ego get involved when it comes to choosing which solutions to develop and take further.

Finding the best solution is the goal of all problem solving workshops and here is the place to ensure that your solution is well thought out, sufficiently robust and fit for purpose.

5. Decision making and planning

Nearly there! Once you’ve got a set of possible, you’ll need to make a decision on which to implement. This can be a consensus-based group decision or it might be for a leader or major stakeholder to decide. You’ll find a set of effective decision making methods below.

Once your group has reached consensus and selected a solution, there are some additional actions that also need to be decided upon. You’ll want to work on allocating ownership of the project, figure out who will do what, how the success of the solution will be measured and decide the next course of action.

Set clear accountabilities, actions, timeframes, and follow-ups for your chosen solution. Make these decisions and set clear next-steps in the problem solving workshop so that everyone is aligned and you can move forward effectively as a group.

Ensuring that you plan for the roll-out of a solution is one of the most important problem solving steps. Without adequate planning or oversight, it can prove impossible to measure success or iterate further if the problem was not solved.

6. Solution implementation

This is what we were waiting for! All problem solving processes have the end goal of implementing an effective and impactful solution that your group has confidence in.

Project management and communication skills are key here – your solution may need to adjust when out in the wild or you might discover new challenges along the way. For some solutions, you might also implement a test with a small group and monitor results before rolling it out to an entire company.

You should have a clear owner for your solution who will oversee the plans you made together and help ensure they’re put into place. This person will often coordinate the implementation team and set-up processes to measure the efficacy of your solution too.

7. Solution evaluation

So you and your team developed a great solution to a problem and have a gut feeling it’s been solved. Work done, right? Wrong. All problem solving strategies benefit from evaluation, consideration, and feedback.

You might find that the solution does not work for everyone, might create new problems, or is potentially so successful that you will want to roll it out to larger teams or as part of other initiatives.

None of that is possible without taking the time to evaluate the success of the solution you developed in your problem solving model and adjust if necessary.

Remember that the problem solving process is often iterative and it can be common to not solve complex issues on the first try. Even when this is the case, you and your team will have generated learning that will be important for future problem solving workshops or in other parts of the organization.

It’s also worth underlining how important record keeping is throughout the problem solving process. If a solution didn’t work, you need to have the data and records to see why that was the case. If you go back to the drawing board, notes from the previous workshop can help save time.

What does an effective problem solving process look like?

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . In our experience, a well-structured problem solving workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

The format of a workshop ensures that you can get buy-in from your group, encourage free-thinking and solution exploration before making a decision on what to implement following the session.

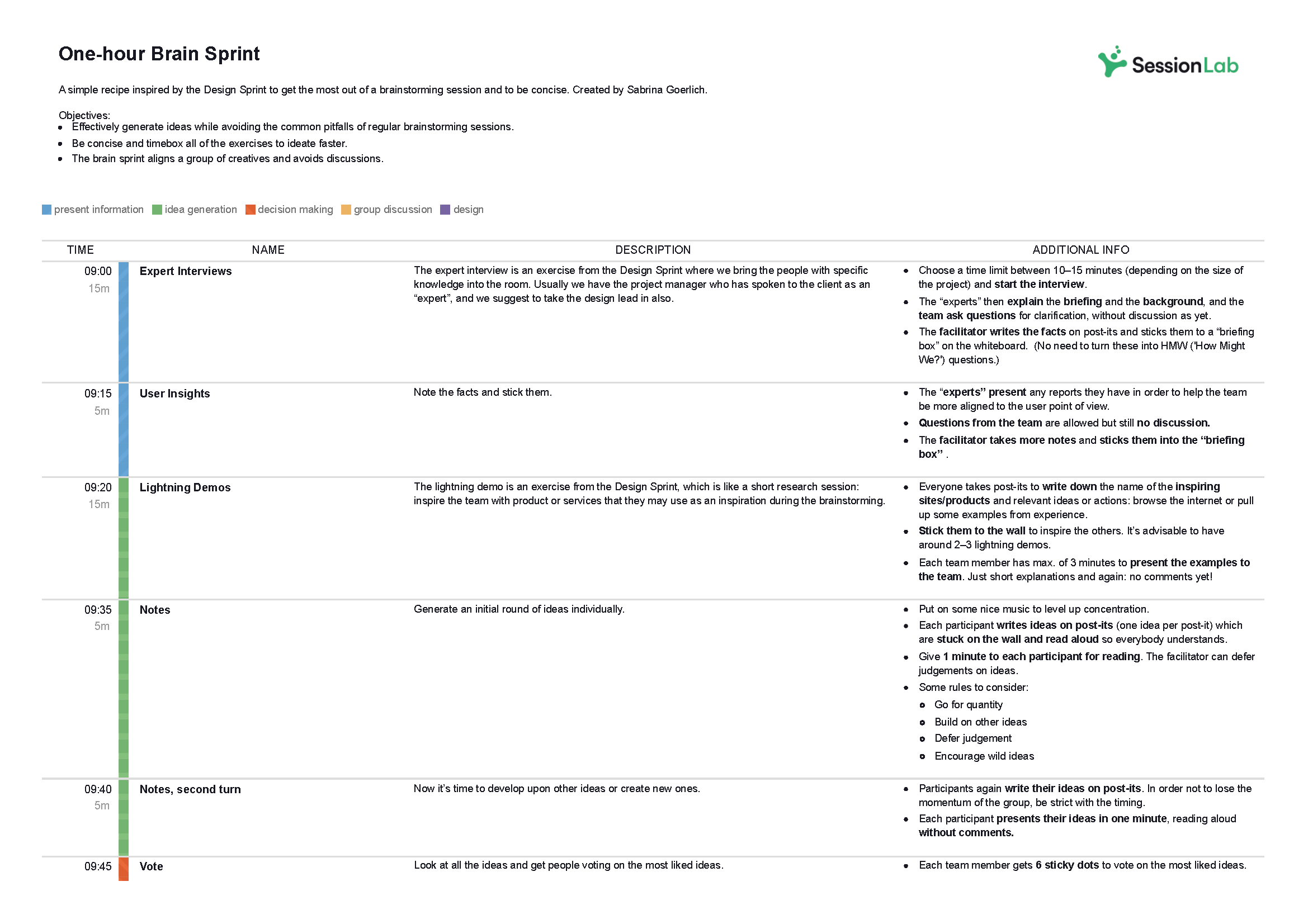

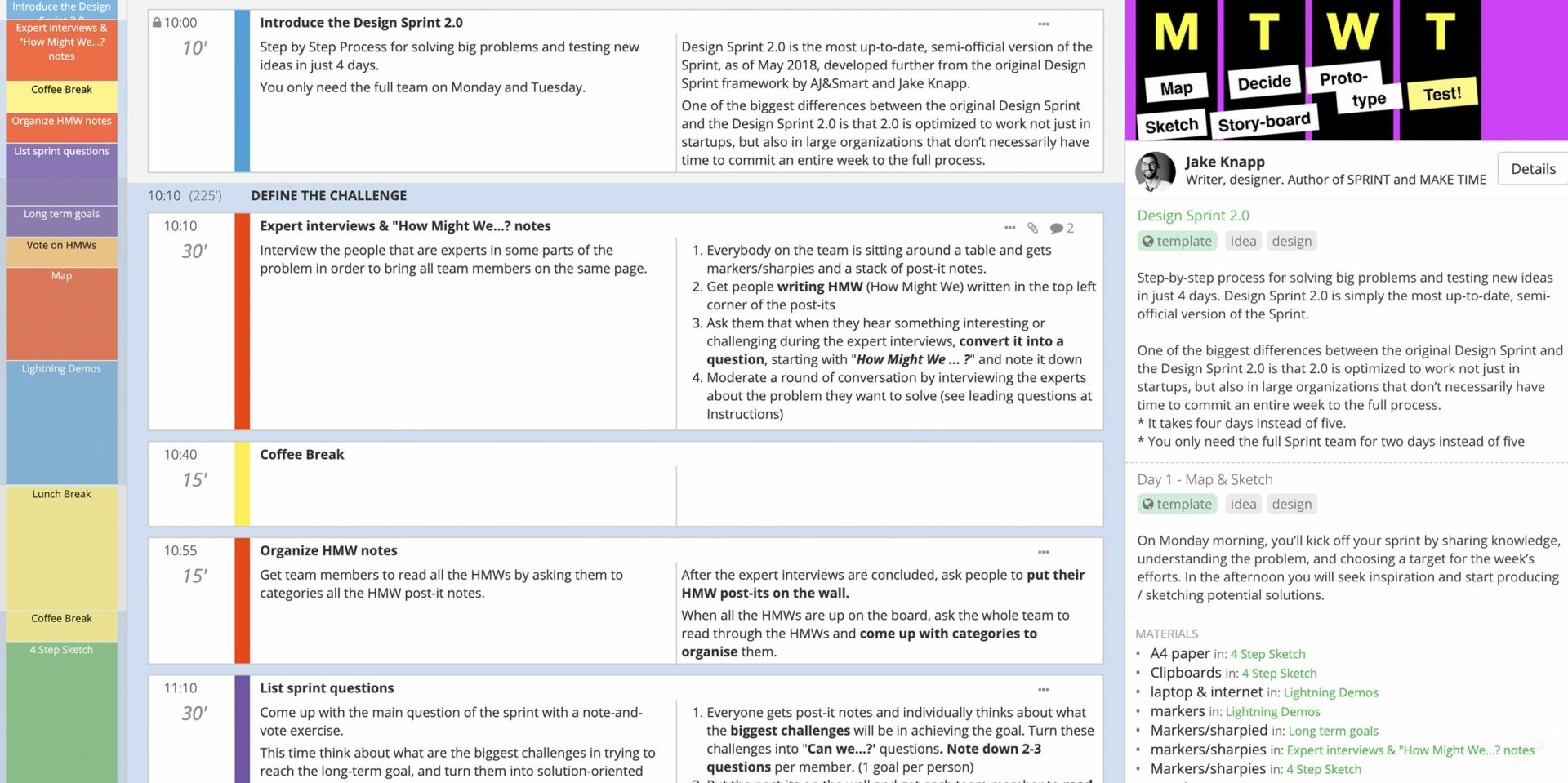

This Design Sprint 2.0 template is an effective problem solving process from top agency AJ&Smart. It’s a great format for the entire problem solving process, with four-days of workshops designed to surface issues, explore solutions and even test a solution.

Check it for an example of how you might structure and run a problem solving process and feel free to copy and adjust it your needs!

For a shorter process you can run in a single afternoon, this remote problem solving agenda will guide you effectively in just a couple of hours.

Whatever the length of your workshop, by using SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Complete problem-solving methods

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.

Like all problem-solving frameworks, Six Thinking Hats is effective at helping teams remove roadblocks from a conversation or discussion and come to terms with all the aspects necessary to solve complex problems.

The Six Thinking Hats #creative thinking #meeting facilitation #problem solving #issue resolution #idea generation #conflict resolution The Six Thinking Hats are used by individuals and groups to separate out conflicting styles of thinking. They enable and encourage a group of people to think constructively together in exploring and implementing change, rather than using argument to fight over who is right and who is wrong.

Lightning Decision Jam

Featured courtesy of Jonathan Courtney of AJ&Smart Berlin, Lightning Decision Jam is one of those strategies that should be in every facilitation toolbox. Exploring problems and finding solutions is often creative in nature, though as with any creative process, there is the potential to lose focus and get lost.

Unstructured discussions might get you there in the end, but it’s much more effective to use a method that creates a clear process and team focus.

In Lightning Decision Jam, participants are invited to begin by writing challenges, concerns, or mistakes on post-its without discussing them before then being invited by the moderator to present them to the group.

From there, the team vote on which problems to solve and are guided through steps that will allow them to reframe those problems, create solutions and then decide what to execute on.

By deciding the problems that need to be solved as a team before moving on, this group process is great for ensuring the whole team is aligned and can take ownership over the next stages.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly It doesn’t matter where you work and what your job role is, if you work with other people together as a team, you will always encounter the same challenges: Unclear goals and miscommunication that cause busy work and overtime Unstructured meetings that leave attendants tired, confused and without clear outcomes. Frustration builds up because internal challenges to productivity are not addressed Sudden changes in priorities lead to a loss of focus and momentum Muddled compromise takes the place of clear decision- making, leaving everybody to come up with their own interpretation. In short, a lack of structure leads to a waste of time and effort, projects that drag on for too long and frustrated, burnt out teams. AJ&Smart has worked with some of the most innovative, productive companies in the world. What sets their teams apart from others is not better tools, bigger talent or more beautiful offices. The secret sauce to becoming a more productive, more creative and happier team is simple: Replace all open discussion or brainstorming with a structured process that leads to more ideas, clearer decisions and better outcomes. When a good process provides guardrails and a clear path to follow, it becomes easier to come up with ideas, make decisions and solve problems. This is why AJ&Smart created Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ). It’s a simple and short, but powerful group exercise that can be run either in-person, in the same room, or remotely with distributed teams.

Problem Definition Process

While problems can be complex, the problem-solving methods you use to identify and solve those problems can often be simple in design.

By taking the time to truly identify and define a problem before asking the group to reframe the challenge as an opportunity, this method is a great way to enable change.

Begin by identifying a focus question and exploring the ways in which it manifests before splitting into five teams who will each consider the problem using a different method: escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion or wishful. Teams develop a problem objective and create ideas in line with their method before then feeding them back to the group.

This method is great for enabling in-depth discussions while also creating space for finding creative solutions too!

Problem Definition #problem solving #idea generation #creativity #online #remote-friendly A problem solving technique to define a problem, challenge or opportunity and to generate ideas.

The 5 Whys

Sometimes, a group needs to go further with their strategies and analyze the root cause at the heart of organizational issues. An RCA or root cause analysis is the process of identifying what is at the heart of business problems or recurring challenges.

The 5 Whys is a simple and effective method of helping a group go find the root cause of any problem or challenge and conduct analysis that will deliver results.

By beginning with the creation of a problem statement and going through five stages to refine it, The 5 Whys provides everything you need to truly discover the cause of an issue.

The 5 Whys #hyperisland #innovation This simple and powerful method is useful for getting to the core of a problem or challenge. As the title suggests, the group defines a problems, then asks the question “why” five times, often using the resulting explanation as a starting point for creative problem solving.

World Cafe is a simple but powerful facilitation technique to help bigger groups to focus their energy and attention on solving complex problems.

World Cafe enables this approach by creating a relaxed atmosphere where participants are able to self-organize and explore topics relevant and important to them which are themed around a central problem-solving purpose. Create the right atmosphere by modeling your space after a cafe and after guiding the group through the method, let them take the lead!

Making problem-solving a part of your organization’s culture in the long term can be a difficult undertaking. More approachable formats like World Cafe can be especially effective in bringing people unfamiliar with workshops into the fold.

World Cafe #hyperisland #innovation #issue analysis World Café is a simple yet powerful method, originated by Juanita Brown, for enabling meaningful conversations driven completely by participants and the topics that are relevant and important to them. Facilitators create a cafe-style space and provide simple guidelines. Participants then self-organize and explore a set of relevant topics or questions for conversation.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

One of the best approaches is to create a safe space for a group to share and discover practices and behaviors that can help them find their own solutions.

With DAD, you can help a group choose which problems they wish to solve and which approaches they will take to do so. It’s great at helping remove resistance to change and can help get buy-in at every level too!

This process of enabling frontline ownership is great in ensuring follow-through and is one of the methods you will want in your toolbox as a facilitator.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD) #idea generation #liberating structures #action #issue analysis #remote-friendly DADs make it easy for a group or community to discover practices and behaviors that enable some individuals (without access to special resources and facing the same constraints) to find better solutions than their peers to common problems. These are called positive deviant (PD) behaviors and practices. DADs make it possible for people in the group, unit, or community to discover by themselves these PD practices. DADs also create favorable conditions for stimulating participants’ creativity in spaces where they can feel safe to invent new and more effective practices. Resistance to change evaporates as participants are unleashed to choose freely which practices they will adopt or try and which problems they will tackle. DADs make it possible to achieve frontline ownership of solutions.

Design Sprint 2.0

Want to see how a team can solve big problems and move forward with prototyping and testing solutions in a few days? The Design Sprint 2.0 template from Jake Knapp, author of Sprint, is a complete agenda for a with proven results.

Developing the right agenda can involve difficult but necessary planning. Ensuring all the correct steps are followed can also be stressful or time-consuming depending on your level of experience.

Use this complete 4-day workshop template if you are finding there is no obvious solution to your challenge and want to focus your team around a specific problem that might require a shortcut to launching a minimum viable product or waiting for the organization-wide implementation of a solution.

Open space technology

Open space technology- developed by Harrison Owen – creates a space where large groups are invited to take ownership of their problem solving and lead individual sessions. Open space technology is a great format when you have a great deal of expertise and insight in the room and want to allow for different takes and approaches on a particular theme or problem you need to be solved.

Start by bringing your participants together to align around a central theme and focus their efforts. Explain the ground rules to help guide the problem-solving process and then invite members to identify any issue connecting to the central theme that they are interested in and are prepared to take responsibility for.

Once participants have decided on their approach to the core theme, they write their issue on a piece of paper, announce it to the group, pick a session time and place, and post the paper on the wall. As the wall fills up with sessions, the group is then invited to join the sessions that interest them the most and which they can contribute to, then you’re ready to begin!

Everyone joins the problem-solving group they’ve signed up to, record the discussion and if appropriate, findings can then be shared with the rest of the group afterward.

Open Space Technology #action plan #idea generation #problem solving #issue analysis #large group #online #remote-friendly Open Space is a methodology for large groups to create their agenda discerning important topics for discussion, suitable for conferences, community gatherings and whole system facilitation

Techniques to identify and analyze problems

Using a problem-solving method to help a team identify and analyze a problem can be a quick and effective addition to any workshop or meeting.

While further actions are always necessary, you can generate momentum and alignment easily, and these activities are a great place to get started.

We’ve put together this list of techniques to help you and your team with problem identification, analysis, and discussion that sets the foundation for developing effective solutions.

Let’s take a look!

Fishbone Analysis

Organizational or team challenges are rarely simple, and it’s important to remember that one problem can be an indication of something that goes deeper and may require further consideration to be solved.

Fishbone Analysis helps groups to dig deeper and understand the origins of a problem. It’s a great example of a root cause analysis method that is simple for everyone on a team to get their head around.

Participants in this activity are asked to annotate a diagram of a fish, first adding the problem or issue to be worked on at the head of a fish before then brainstorming the root causes of the problem and adding them as bones on the fish.

Using abstractions such as a diagram of a fish can really help a team break out of their regular thinking and develop a creative approach.

Fishbone Analysis #problem solving ##root cause analysis #decision making #online facilitation A process to help identify and understand the origins of problems, issues or observations.

Problem Tree

Encouraging visual thinking can be an essential part of many strategies. By simply reframing and clarifying problems, a group can move towards developing a problem solving model that works for them.

In Problem Tree, groups are asked to first brainstorm a list of problems – these can be design problems, team problems or larger business problems – and then organize them into a hierarchy. The hierarchy could be from most important to least important or abstract to practical, though the key thing with problem solving games that involve this aspect is that your group has some way of managing and sorting all the issues that are raised.

Once you have a list of problems that need to be solved and have organized them accordingly, you’re then well-positioned for the next problem solving steps.

Problem tree #define intentions #create #design #issue analysis A problem tree is a tool to clarify the hierarchy of problems addressed by the team within a design project; it represents high level problems or related sublevel problems.

SWOT Analysis

Chances are you’ve heard of the SWOT Analysis before. This problem-solving method focuses on identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats is a tried and tested method for both individuals and teams.

Start by creating a desired end state or outcome and bare this in mind – any process solving model is made more effective by knowing what you are moving towards. Create a quadrant made up of the four categories of a SWOT analysis and ask participants to generate ideas based on each of those quadrants.

Once you have those ideas assembled in their quadrants, cluster them together based on their affinity with other ideas. These clusters are then used to facilitate group conversations and move things forward.

SWOT analysis #gamestorming #problem solving #action #meeting facilitation The SWOT Analysis is a long-standing technique of looking at what we have, with respect to the desired end state, as well as what we could improve on. It gives us an opportunity to gauge approaching opportunities and dangers, and assess the seriousness of the conditions that affect our future. When we understand those conditions, we can influence what comes next.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix

Not every problem-solving approach is right for every challenge, and deciding on the right method for the challenge at hand is a key part of being an effective team.

The Agreement Certainty matrix helps teams align on the nature of the challenges facing them. By sorting problems from simple to chaotic, your team can understand what methods are suitable for each problem and what they can do to ensure effective results.

If you are already using Liberating Structures techniques as part of your problem-solving strategy, the Agreement-Certainty Matrix can be an invaluable addition to your process. We’ve found it particularly if you are having issues with recurring problems in your organization and want to go deeper in understanding the root cause.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix #issue analysis #liberating structures #problem solving You can help individuals or groups avoid the frequent mistake of trying to solve a problem with methods that are not adapted to the nature of their challenge. The combination of two questions makes it possible to easily sort challenges into four categories: simple, complicated, complex , and chaotic . A problem is simple when it can be solved reliably with practices that are easy to duplicate. It is complicated when experts are required to devise a sophisticated solution that will yield the desired results predictably. A problem is complex when there are several valid ways to proceed but outcomes are not predictable in detail. Chaotic is when the context is too turbulent to identify a path forward. A loose analogy may be used to describe these differences: simple is like following a recipe, complicated like sending a rocket to the moon, complex like raising a child, and chaotic is like the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.” The Liberating Structures Matching Matrix in Chapter 5 can be used as the first step to clarify the nature of a challenge and avoid the mismatches between problems and solutions that are frequently at the root of chronic, recurring problems.

Organizing and charting a team’s progress can be important in ensuring its success. SQUID (Sequential Question and Insight Diagram) is a great model that allows a team to effectively switch between giving questions and answers and develop the skills they need to stay on track throughout the process.

Begin with two different colored sticky notes – one for questions and one for answers – and with your central topic (the head of the squid) on the board. Ask the group to first come up with a series of questions connected to their best guess of how to approach the topic. Ask the group to come up with answers to those questions, fix them to the board and connect them with a line. After some discussion, go back to question mode by responding to the generated answers or other points on the board.

It’s rewarding to see a diagram grow throughout the exercise, and a completed SQUID can provide a visual resource for future effort and as an example for other teams.

SQUID #gamestorming #project planning #issue analysis #problem solving When exploring an information space, it’s important for a group to know where they are at any given time. By using SQUID, a group charts out the territory as they go and can navigate accordingly. SQUID stands for Sequential Question and Insight Diagram.

To continue with our nautical theme, Speed Boat is a short and sweet activity that can help a team quickly identify what employees, clients or service users might have a problem with and analyze what might be standing in the way of achieving a solution.

Methods that allow for a group to make observations, have insights and obtain those eureka moments quickly are invaluable when trying to solve complex problems.

In Speed Boat, the approach is to first consider what anchors and challenges might be holding an organization (or boat) back. Bonus points if you are able to identify any sharks in the water and develop ideas that can also deal with competitors!

Speed Boat #gamestorming #problem solving #action Speedboat is a short and sweet way to identify what your employees or clients don’t like about your product/service or what’s standing in the way of a desired goal.

The Journalistic Six

Some of the most effective ways of solving problems is by encouraging teams to be more inclusive and diverse in their thinking.

Based on the six key questions journalism students are taught to answer in articles and news stories, The Journalistic Six helps create teams to see the whole picture. By using who, what, when, where, why, and how to facilitate the conversation and encourage creative thinking, your team can make sure that the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the are covered exhaustively and thoughtfully. Reporter’s notebook and dictaphone optional.

The Journalistic Six – Who What When Where Why How #idea generation #issue analysis #problem solving #online #creative thinking #remote-friendly A questioning method for generating, explaining, investigating ideas.

Individual and group perspectives are incredibly important, but what happens if people are set in their minds and need a change of perspective in order to approach a problem more effectively?

Flip It is a method we love because it is both simple to understand and run, and allows groups to understand how their perspectives and biases are formed.

Participants in Flip It are first invited to consider concerns, issues, or problems from a perspective of fear and write them on a flip chart. Then, the group is asked to consider those same issues from a perspective of hope and flip their understanding.

No problem and solution is free from existing bias and by changing perspectives with Flip It, you can then develop a problem solving model quickly and effectively.

Flip It! #gamestorming #problem solving #action Often, a change in a problem or situation comes simply from a change in our perspectives. Flip It! is a quick game designed to show players that perspectives are made, not born.

LEGO Challenge

Now for an activity that is a little out of the (toy) box. LEGO Serious Play is a facilitation methodology that can be used to improve creative thinking and problem-solving skills.

The LEGO Challenge includes giving each member of the team an assignment that is hidden from the rest of the group while they create a structure without speaking.

What the LEGO challenge brings to the table is a fun working example of working with stakeholders who might not be on the same page to solve problems. Also, it’s LEGO! Who doesn’t love LEGO!

LEGO Challenge #hyperisland #team A team-building activity in which groups must work together to build a structure out of LEGO, but each individual has a secret “assignment” which makes the collaborative process more challenging. It emphasizes group communication, leadership dynamics, conflict, cooperation, patience and problem solving strategy.

What, So What, Now What?

If not carefully managed, the problem identification and problem analysis stages of the problem-solving process can actually create more problems and misunderstandings.

The What, So What, Now What? problem-solving activity is designed to help collect insights and move forward while also eliminating the possibility of disagreement when it comes to identifying, clarifying, and analyzing organizational or work problems.

Facilitation is all about bringing groups together so that might work on a shared goal and the best problem-solving strategies ensure that teams are aligned in purpose, if not initially in opinion or insight.

Throughout the three steps of this game, you give everyone on a team to reflect on a problem by asking what happened, why it is important, and what actions should then be taken.

This can be a great activity for bringing our individual perceptions about a problem or challenge and contextualizing it in a larger group setting. This is one of the most important problem-solving skills you can bring to your organization.

W³ – What, So What, Now What? #issue analysis #innovation #liberating structures You can help groups reflect on a shared experience in a way that builds understanding and spurs coordinated action while avoiding unproductive conflict. It is possible for every voice to be heard while simultaneously sifting for insights and shaping new direction. Progressing in stages makes this practical—from collecting facts about What Happened to making sense of these facts with So What and finally to what actions logically follow with Now What . The shared progression eliminates most of the misunderstandings that otherwise fuel disagreements about what to do. Voila!

Journalists

Problem analysis can be one of the most important and decisive stages of all problem-solving tools. Sometimes, a team can become bogged down in the details and are unable to move forward.

Journalists is an activity that can avoid a group from getting stuck in the problem identification or problem analysis stages of the process.

In Journalists, the group is invited to draft the front page of a fictional newspaper and figure out what stories deserve to be on the cover and what headlines those stories will have. By reframing how your problems and challenges are approached, you can help a team move productively through the process and be better prepared for the steps to follow.

Journalists #vision #big picture #issue analysis #remote-friendly This is an exercise to use when the group gets stuck in details and struggles to see the big picture. Also good for defining a vision.

Problem-solving techniques for brainstorming solutions

Now you have the context and background of the problem you are trying to solving, now comes the time to start ideating and thinking about how you’ll solve the issue.

Here, you’ll want to encourage creative, free thinking and speed. Get as many ideas out as possible and explore different perspectives so you have the raw material for the next step.

Looking at a problem from a new angle can be one of the most effective ways of creating an effective solution. TRIZ is a problem-solving tool that asks the group to consider what they must not do in order to solve a challenge.

By reversing the discussion, new topics and taboo subjects often emerge, allowing the group to think more deeply and create ideas that confront the status quo in a safe and meaningful way. If you’re working on a problem that you’ve tried to solve before, TRIZ is a great problem-solving method to help your team get unblocked.

Making Space with TRIZ #issue analysis #liberating structures #issue resolution You can clear space for innovation by helping a group let go of what it knows (but rarely admits) limits its success and by inviting creative destruction. TRIZ makes it possible to challenge sacred cows safely and encourages heretical thinking. The question “What must we stop doing to make progress on our deepest purpose?” induces seriously fun yet very courageous conversations. Since laughter often erupts, issues that are otherwise taboo get a chance to be aired and confronted. With creative destruction come opportunities for renewal as local action and innovation rush in to fill the vacuum. Whoosh!

Mindspin

Brainstorming is part of the bread and butter of the problem-solving process and all problem-solving strategies benefit from getting ideas out and challenging a team to generate solutions quickly.

With Mindspin, participants are encouraged not only to generate ideas but to do so under time constraints and by slamming down cards and passing them on. By doing multiple rounds, your team can begin with a free generation of possible solutions before moving on to developing those solutions and encouraging further ideation.

This is one of our favorite problem-solving activities and can be great for keeping the energy up throughout the workshop. Remember the importance of helping people become engaged in the process – energizing problem-solving techniques like Mindspin can help ensure your team stays engaged and happy, even when the problems they’re coming together to solve are complex.

MindSpin #teampedia #idea generation #problem solving #action A fast and loud method to enhance brainstorming within a team. Since this activity has more than round ideas that are repetitive can be ruled out leaving more creative and innovative answers to the challenge.

The Creativity Dice

One of the most useful problem solving skills you can teach your team is of approaching challenges with creativity, flexibility, and openness. Games like The Creativity Dice allow teams to overcome the potential hurdle of too much linear thinking and approach the process with a sense of fun and speed.

In The Creativity Dice, participants are organized around a topic and roll a dice to determine what they will work on for a period of 3 minutes at a time. They might roll a 3 and work on investigating factual information on the chosen topic. They might roll a 1 and work on identifying the specific goals, standards, or criteria for the session.

Encouraging rapid work and iteration while asking participants to be flexible are great skills to cultivate. Having a stage for idea incubation in this game is also important. Moments of pause can help ensure the ideas that are put forward are the most suitable.

The Creativity Dice #creativity #problem solving #thiagi #issue analysis Too much linear thinking is hazardous to creative problem solving. To be creative, you should approach the problem (or the opportunity) from different points of view. You should leave a thought hanging in mid-air and move to another. This skipping around prevents premature closure and lets your brain incubate one line of thought while you consciously pursue another.

Idea and Concept Development

Brainstorming without structure can quickly become chaotic or frustrating. In a problem-solving context, having an ideation framework to follow can help ensure your team is both creative and disciplined.

In this method, you’ll find an idea generation process that encourages your group to brainstorm effectively before developing their ideas and begin clustering them together. By using concepts such as Yes and…, more is more and postponing judgement, you can create the ideal conditions for brainstorming with ease.

Idea & Concept Development #hyperisland #innovation #idea generation Ideation and Concept Development is a process for groups to work creatively and collaboratively to generate creative ideas. It’s a general approach that can be adapted and customized to suit many different scenarios. It includes basic principles for idea generation and several steps for groups to work with. It also includes steps for idea selection and development.

Problem-solving techniques for developing and refining solutions

The success of any problem-solving process can be measured by the solutions it produces. After you’ve defined the issue, explored existing ideas, and ideated, it’s time to develop and refine your ideas in order to bring them closer to a solution that actually solves the problem.