An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Public Health

- v.110(11); Nov 2020

Impact of Police Violence on Mental Health: A Theoretical Framework

J. DeVylder wrote the original draft of the article. L. Fedina and B. Link contributed substantially to the editing and revision of subsequent drafts of the article. All authors participated in the conceptual development and final editing of the article.

Police violence has increasingly been recognized as a public health concern in the United States, and accumulating evidence has shown police violence exposure to be linked to a broad range of health and mental health outcomes. These associations appear to extend beyond the typical associations between violence and mental health, and to be independent of the effects of co-occurring forms of trauma and violence exposure. However, there is no existing theoretical framework within which we may understand the unique contributions of police violence to mental health and illness.

This article aims to identify potential factors that may distinguish police violence from other forms of violence and trauma exposure, and to explore the possibility that this unique combination of factors distinguishes police violence from related risk exposures. We identify 8 factors that may alter this relationship, including those that increase the likelihood of overall exposure, increase the psychological impact of police violence, and impede the possibility of coping or recovery from such exposures.

On the basis of these factors, we propose a theoretical framework for the further study of police violence from a public mental health perspective.

A new public narrative around the prevalence and effects of police violence has emerged over the past several years in the United States, accompanied recently by a dramatic shift in public opinion following the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Elijah McClain, and the related national civil uprising and protests. Although Black, Latinx, Native American, and sexual and gender minority communities have long perceived a culture of inequitable treatment, it is only with the widespread adaptation of smartphone technology and real-time dissemination of footage through social media that this has become part of the national consciousness. 1 Media attention has primarily focused on individual incidents of police killings rather than on broader population-level health effects and implications. Although death is certainly the most severe health outcome, it is just as certainly not the most common. The mental health effects of police violence may be less visible yet much more pervasive and, potentially, more impactful when considered across an entire community or population.

In this article, we place the emerging literature on the mental health correlates of police violence within the broader context of research on violence, and explore whether the “police” in “police violence” bestows a specific meaning that extends beyond violence itself—is police violence a form of violence just like any other? By describing potential factors that may distinguish police violence from other forms of violence and trauma exposure—either as factors that are unique to police violence or that vary in degree between police violence and other forms of violence—we propose a theoretical framework for the further study of police violence from a public mental health perspective.

RELEVANCE OF POLICE VIOLENCE TO MENTAL HEALTH

Stress has pervasive effects on one’s psychological well-being, straining one’s sense of role or purpose and affecting concepts of self-esteem and mastery, which contributes in turn to mental health difficulties. 2 Although there is not a single unifying theory linking stressful or traumatic social exposures to mental health symptoms, these factors play a prominent etiological role in leading theories on a broad range of disparate mental health conditions, such as the social signal transduction theory of depression 3 or the social defeat theory of psychosis. 4 Although the often-siloed research of each psychological outcome has led to uniquely labeled theories, these theories all point to a pathway in which trauma spurs biological or psychological changes that manifest over time as psychiatric symptoms, particularly when the trauma is sexually or physically violent. 5 Further, although theoretical work on stressful life events has attempted to provide a broader framework for how stress may translate to psychopathology, focusing particularly on the role of uncontrollable stressful events that affect one’s usual activities, goals, and values, this framework has not been directly applied toward understanding police violence. 6

We therefore explore the construct of police violence as a potential etiological factor for mental health conditions, based on the assumptions that (1) violence and trauma are associated with elevated risk for a broad range of mental health symptoms and (2) the contribution to risk may vary not only by severity of exposure, but also by type of exposure. Specifically, we explore whether police violence possesses a unique pattern of characteristics and mechanisms that distinguish it from other forms of violence exposure in its association with mental health symptoms.

For the purposes of this article, we refer generally to “police violence” and “mental health” because there is not yet sufficient research to confidently link specific subtypes of police violence to specific mental health outcomes. We therefore define police violence as acute events of physical, sexual, psychological, or neglectful violence, following the World Health Organization’s guidelines on defining violence and earlier work on the phenomenology of police violence exposure. 7 Mental health is intended to be inclusive of behaviors and psychological symptoms that would be considered indicators of clinical psychopathology, including but not limited to general psychological distress, posttraumatic stress symptoms, suicidal ideation and behavior, psychosis-like experiences, and depression. These definitions may need to be expanded as this literature develops, as currently it typically focuses on acute violent events (rather than chronic or vicarious exposures) and a psychopathology-oriented view of mental health (rather than a focus on functioning or quality of life), but they are being used here as a reflection of the variables typically employed in the literature at this point in time.

MENTAL HEALTH CORRELATES OF POLICE VIOLENCE

Recent public attention directed toward police violence has spurred an emerging literature on the health significance of police violence exposure, 1,8,9 addressing a long-unheeded call to conceptualize police violence as a public health issue in the United States. 7 Cross-sectional studies have consistently found clinically and statistically significant associations between police violence exposure and a range of mental health outcomes, 10-16 and community-level data have likewise demonstrated higher rates of mental health symptoms in neighborhoods or cities in which police abuse (e.g., “stop and frisk” practices, which are primarily used in neighborhoods predominantly composed of people of color) and killings of unarmed civilians are more common. 17,18 These associations have generally been found to remain statistically significant (and of sufficient effect sizes to support public health significance) even with adjustment for closely related forms of violence exposure, such as interpersonal violence or lifetime abuse exposure. 10,14 For example, exposure to assaultive forms of police violence (i.e., physical or sexual) has been found to be associated with 4- to 11-fold greater odds for a suicide attempt among adults across racial/ethnic groups, even with conservative adjustments. 12,14 Although most of this research has been conducted with adults, recent analyses suggest that this problem extends into adolescence as well. 19 A selective overview of recent work on this topic is provided in Table 1 , and has recently been reviewed elsewhere. 21

TABLE 1—

Selective Overview of Recent Studies of Police Violence and Mental Health: United States

Note. DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994); PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

WHY IS POLICE VIOLENCE DIFFERENT?

Overall, accumulated evidence consistently identifies moderate to strong associations between self-reported exposure to police violence and measures of mental health. Additionally, some evidence indicates that these effects operate independently of exposure to other forms of violence. It was this accumulation of evidence that led us to ask whether and to what extent police violence has unique features that lead it to be so impactful for mental health outcomes. Here, we propose 8 factors that may distinguish police violence from other forms of violence, some of which are unique to police violence and others that may vary by degree. Given the complexity of the issue, we see our conceptualization as a step toward a more complete understanding of this important issue, recognizing that it will need further development in the time ahead.

Police Violence Is State Sanctioned

A long tradition in social science theory suggests that the police play a critical role in disciplining the public, not just in terms of offenses and punishments but in the construction and maintenance of an established social order favoring dominant groups. In light of the use of the police in this regard, it follows that exposure to violence emanating from their actions would have distinct and pernicious features. 22,23 Police organizations in the United States are thus authoritative institutions legitimized to apply force—and potentially fatal force—to maintain a particular social and political order. 24 In interactions with civilians, police officers are in positions of relatively greater power because of both the symbolic and state-sanctioned status of their profession, and their immediate legal availability of means (e.g., guns, batons, tasers) to wield force, threat of force, and coercion, at their discretion. This distinguishes police violence from interpersonal forms of violence that are perpetrated by people who are not sanctioned to enact violence, such as caregivers, peers, or intimate partners.

This distinction is made not to downplay the seriousness of other forms of violence—such as child abuse, intimate partner violence, or sexual assault—but to assert that modern-day police violence is embedded in historical state-enforced practices that permitted cruel, unusual, and dehumanizing punishment of individuals deemed to be from threatening or “dangerous classes,” 25 particularly Blacks. Communities of color and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) communities have been historically subjected to racially motivated, discriminatory state-sponsored laws (e.g., Jim Crow laws, sodomy laws) enforced by police that permitted harassment, discrimination, and excessive and fatal force against individuals from these communities. As such, the processes and contexts in which police violence has been historically perpetuated are uniquely distinct from the perpetuation of interpersonal forms of violence by others. Furthermore, police violence is sanctioned not only by institutions in the United States but also by the American public, and is intentionally designed to uphold White supremacy. 26 Members of the dominant society thus contribute to police violence and the lack of police accountability.

The Police Are a Pervasive Presence

A core characteristic of many people’s reaction to violence is avoidance of reminders and triggers—especially of the perpetrators themselves. This common and adaptive response to a harmful situation is not available to people who have been exposed to police violence. It is simply not possible to avoid a system that inflicts racially motivated violence while staying within the country, even if one manages to avoid the specific offending officer, and the stress of this police avoidance has been shown to be directly related to severity of depressive symptoms among adult Black men. 20 Much in the same way that police violence by one officer generalizes to fear of all officers even if most officers do not perpetrate violence, intimate partner violence often generalizes to fear of all romantic partners, particularly of a given gender. However, this process may be exacerbated for victims of police violence and is in some ways different from what transpires when people are exposed to other forms of violence. For example, although victims of intimate partner violence and sexual assault who seek help and legal recourse face enormous barriers and challenges, the US justice system can separate victims from perpetrators through legal protection or restraining orders or through incarceration of the perpetrator. In the case of police violence, the presence of law enforcement in the US context is pervasive, and victims have few or no options to seek help and legal recourse, or to entirely avoid police officers in public places.

There Are Limited Options for Recourse

Victims of police violence have little legal recourse or opportunities for seeking help in the criminal justice system. The police have legal sanction to intervene in other crimes of violence (e.g., sexual assault, physical assault), making it much more difficult to prove that the violence was unjustly or excessively delivered. Additionally, the people reviewing disputed cases are often also police officers, and indicted police officers are tried by prosecutors who must otherwise work with police officers. These and other circumstances make contesting the perpetration of violence extremely difficult. Victims of other forms of violence, particularly intimate partner violence, indeed face enormous barriers in seeking help and legal recourse, including stigma in reporting intimate partner violence, poverty and other economic barriers, and other sociocultural and contextual factors. 27 Victims of police violence face many of these same barriers; because they have few if any options for reporting an incident, for legal recourse, or for advocacy services and referrals to mental health treatment, any mental health symptoms they have may worsen over time. 28

Police Culture Deters Internal Accountability

Police violence occurs within a larger, institutional context that is shaped by the organization’s culture. An organizational culture that upholds a “code of silence” surrounding police officers’ abusive behaviors toward civilians allows for the perpetuation of police abuse of power and can prevent police officers, particularly those from lower ranks, from reporting such abuses to their superiors. 29

Given that violence perpetuated through institutions (rather than interpersonal relationships) is supported by an organizational culture condoning harmful behaviors (e.g., harassment, coercion, psychological abuse, physical assault), particularly against those from historically marginalized and disadvantaged communities, experiencing abuse at the hands of police officers who wield such power and authority over civilians may lead to exacerbated mental health consequences. Past research suggests that exposure to sexual assault while serving in the military is associated with psychiatric disorders above and beyond symptoms associated with civilian sexual assault. 30 This suggests that contextual factors related to violence, particularly contexts defined by substantial power and authoritative differentials, may influence associations with mental health symptoms.

Police Violence Alters Deeply Held Beliefs

People feel more secure if they feel safe and protected in their day-to-day activities. Assumptive World Theory proposes that people’s deeply held beliefs about the world and themselves can be shaken by an event that forcefully disconfirms such beliefs. 31 Police violence is particularly likely to provide such disconfirming evidence in that the police represent a societal institution that many, though not all, have come to rely on deeply and implicitly for help when a threat emerges. When police perpetrate violence, this belief is shattered as the police are no longer protectors but rather the central threat that needs to be addressed. Additionally, police violence is normative, rather than an acute or singular event, which has led to the erosion of public trust in the police and favorable views of police seen as protective.

Theories of police legitimacy, which refers to the public’s perceptions and views of police as a legitimate authority that is trustworthy and upholds public safety, propose that legitimacy is in part formed through individual police–citizen interactions. 32 As such, it is plausible that individual and group experiences with police violence influence individual views and beliefs that police are not trustworthy sources of protection and safety. Of course, this sundering of assumptions occurs with other types of violence, such as when a believed-to-be-loving spouse hits a partner or a thought-to-be-protective parent engages in child abuse. However, the police have been described as a “last resort” for people when other remedies have been tried and failed. 33 A spouse might call the police as a last resort when other efforts to stop an abusive partner have failed, or a neighbor might make such a call if polite efforts to address enduring abuse of a child have failed. But to the extent that exposure to police violence intrudes, the “last resort” is gone and one may feel stuck in a brutal and frightening world with no recourse.

Racial and Economic Disparities in Exposure

Because police violence is disproportionately directed toward people of color, many of whom are poor, it can underscore a sense of diminished value within the US racial and class hierarchies. Accordingly, the media narrative around police violence has focused on incidents directed toward Black people, and has at times framed these incidents within the context of the legacy of racism and White supremacy in the United States. Data from the first and second Survey of Police–Public Encounters studies have confirmed that—at least in Baltimore, Maryland; New York City; the District of Columbia; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—police violence is more likely to be directed toward people of color, although it is notable that these studies have found Latinx groups to be at approximately the same level of risk as non-Latinx Blacks. 11,14 Although White respondents were also at some risk of exposure to police violence, the racial disparities were significant, even after adjustment for crime involvement and income. Similarly, the prevalence of police-inflicted shootings is approximately 3.5-fold greater among non-Latinx Black than non-Latinx White residents of the United States. 34 Perceptions of racism have been shown to magnify, and perhaps even overshadow, the effects of violent acts. 35 Given that police violence is perceived to be racially motivated in many cases, 34 it is likely that these same effects carry over to many victims of this form of violence.

Notably, there is insufficient prior data to allow a thorough discussion of police violence and mental health among indigenous populations, although the rate of police killings is extremely high among this group. Other potentially high-risk groups likely include people who identify as sexual or gender minorities, people who are homeless, or those who have a severe mental illness diagnosis, among others. Future research should focus on understudied sociodemographic groups that are disproportionately subject to police violence (e.g., indigenous populations, trans individuals), and the conceptual framework presented in this article will require modification as more data become available.

Police Violence Is Stigmatizing

Victims of violent incidents, such as intimate partner violence and community violence, often seek informal support from friends, family, and other social contacts, which has been shown to have a beneficial impact on mental health. 36 However, exposure to police violence carries the potential of inducing harmful stigma. Although stigma may be mitigated in some circumstances in which people distrust the police, a person may nonetheless face judgments from dominant groups who carry the power to discriminate in critical life domains such as educational opportunities, jobs, and housing. This stigma may in turn limit help-seeking behaviors if mental health problems emerge and if there is a perception that treatment providers may not be able to sufficiently understand the circumstances that led to the mental health problems. 37

The police are highly respected in some US communities, sometimes to the point of exaltation, and are supported by a labor union of more than 100 000 workers as well as significant and well-funded public image and advocacy groups such as Blue Lives Matter (which arose as a countermovement to Black Lives Matter and consequently contributes to rather than alleviates concerns of racism and lack of accountability around police violence). As such, there may be substantial stigma around reporting incidents of police violence to family members, friends, and acquaintances, some of whom may have some personal or ideological connection to the police force. Further, when there are major social movements or protests following prominent incidents of police violence, many in the public, particularly those who benefit from the dominant social order that the police help to maintain, take a “blaming the victim” mentality and highlight infractions by the victim that may have justified their injury or death (e.g., the alleged theft of cigarillos by Michael Brown cited as justification for excessive and fatal force). On a broader societal level, protests in Ferguson, Missouri were blamed for a subsequent supposed “war on cops” in which the rate of civilians killing police officers purportedly increased, although there is no actual evidence for any such increase. 38

Police Are Typically Armed

Unlike front-line police officers in some other countries, police officers patrolling neighborhoods in the United States are typically armed, which makes civilians’ interactions with the police potentially more threatening. As a result of several landmark Supreme Court decisions, police officers in the United States have a great deal of legal latitude in determining when to use force, and even fatal force. Additionally, the militarization of police in the United States, largely as a result of “War on Drugs” and “War on Terror” policies, has equipped police departments with firearms and military-grade equipment and expanded their capacity to use force if officers believe their lives or the lives of others are in danger. 39 Thus, the perceived threat of police victimization in civilians’ interactions with police may lead to unique mental health implications for communities most affected by police violence. Further, in addition to the threat of immediate violence through the use of weapons, police encounters also can lead to a more sustained form of exposure to violence and coercion through imprisonment. This threat may be compounded in geographical (e.g., low-income urban areas) and demographic communities (e.g., Black, Latinx, and Native American) with high rates of incarceration.

PROPOSED CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org ) portrays a conceptual model illustrating points at which the influence of police violence on mental health may be different from processes that produce associations between other types of violence exposure and mental health. Specifically, we highlight the 8 potentially influential factors that were described in the previous section, which provides a valuable starting point from which the construct of police violence can be further explored from a public health standpoint. The assumption that police violence is violence like any other would require that the net effect of all of these 8 factors would sum to zero (i.e., have no total effect on mental health). This assumption is highly unlikely, particularly since some of these pathways are now supported by epidemiological evidence (e.g., stress of police avoidance has been recently linked to depressive symptoms). 20 Many (but not all) of these features are present in other forms of violence, although the unique intersection of these features may make police violence a specific type of violence and one worthy of study as a separate construct, similar to the intersection of common and specific elements as determinants of the health impact of other life events. 6 In fact, the literature on stressful life events may provide a useful framework for determining the potential mental health salience of these various features of police violence. Table 2 outlines the primary dimensions of stressful life events based on work by Dohrenwend, 6 a widely used framework for understanding and interpreting the relationship between uncontrollable stressors and mental health outcomes, and it applies these dimensions to our model of police violence.

TABLE 2—

Police Violence Within the Life Events Dimensions Proposed by Dohrenwend

Source. Dohrenwend. 6

To provide a preliminary framework for subsequent work, we have also developed a more complex hypothetical model that illustrates potential mechanisms through which the discussed factors may influence the pathways from police violence to mental health (Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org ). Although it is speculative because of the limited prior empirical research, we are proposing this model to provide potential conceptual pathways that can be tested in future research. Specifically, 4 of the factors (i.e., access to a weapon, state-sanctioned violence, perceived racial and class biases, and risk of incarceration) are likely to increase the immediate impact of violent incidents and therefore may have the most direct effects on mental health, as they are characteristics of the acute incident itself. Three of the factors (i.e., pervasive presence, lack of recourse, and stigma of reporting police violence) pertain more to the time following an exposure to violence, and therefore may have an effect on mental health by impeding coping and recovery. Finally, police culture, in combination with the proliferation of firearms in the US general population and the American legacy of racism, 24 may have an impact on the overall likelihood or prevalence of police violence. 40 Future studies can confirm whether these pathways provide a feasible explanation for the link between police violence and mental health. It is our intention that this preliminary framework may be modified and updated as research evidence accumulates that may confirm or disconfirm these proposed pathways.

CONCLUSIONS AND NEXT STEPS

In this article, we aimed to determine whether it is reasonable to consider police violence exposure to be a unique risk factor for mental distress, independent and conceptually separable from other forms of violence, or whether such a distinction is unjustified and insufficiently parsimonious. We highlighted several features of police violence that may conceptually distinguish it from other forms of violence. For police violence to be considered effectively similar to other forms of violence exposure, regarding its impact on health, the net effect of these distinguishing features would need to sum to zero, or at least have a clinically insignificant effect. Albeit speculatively, we are confident in stating that this seems highly unlikely. There is now substantial and growing evidence that police violence exposure is associated with a broad range of mental health outcomes, independent of other forms of violence and stress exposure. To test the proposed model, subsequent studies will need to examine the mechanisms underlying this risk and map those mechanisms onto these proposed features of police violence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to Leslie Salas-Hernández for contributing to the selective overview of recent studies on the mental health implications of police violence.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional approval was not required for this conceptual article, which did not directly involve human participants.

See also Alang, p. 1597 .

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

Protesters take a knee in front of New York City police officers during a solidarity rally for George Floyd, June 4, 2020.

AP Photo/Frank Franklin II

Solving racial disparities in policing

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Experts say approach must be comprehensive as roots are embedded in culture

“ Unequal ” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. The first part explores the experience of people of color with the criminal justice legal system in America.

It seems there’s no end to them. They are the recent videos and reports of Black and brown people beaten or killed by law enforcement officers, and they have fueled a national outcry over the disproportionate use of excessive, and often lethal, force against people of color, and galvanized demands for police reform.

This is not the first time in recent decades that high-profile police violence — from the 1991 beating of Rodney King to the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 — ignited calls for change. But this time appears different. The police killings of Breonna Taylor in March, George Floyd in May, and a string of others triggered historic, widespread marches and rallies across the nation, from small towns to major cities, drawing protesters of unprecedented diversity in race, gender, and age.

According to historians and other scholars, the problem is embedded in the story of the nation and its culture. Rooted in slavery, racial disparities in policing and police violence, they say, are sustained by systemic exclusion and discrimination, and fueled by implicit and explicit bias. Any solution clearly will require myriad new approaches to law enforcement, courts, and community involvement, and comprehensive social change driven from the bottom up and the top down.

While police reform has become a major focus, the current moment of national reckoning has widened the lens on systemic racism for many Americans. The range of issues, though less familiar to some, is well known to scholars and activists. Across Harvard, for instance, faculty members have long explored the ways inequality permeates every aspect of American life. Their research and scholarship sits at the heart of a new Gazette series starting today aimed at finding ways forward in the areas of democracy; wealth and opportunity; environment and health; and education. It begins with this first on policing.

Harvard Kennedy School Professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people.

Photo by Martha Stewart

The history of racialized policing

Like many scholars, Khalil Gibran Muhammad , professor of history, race, and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School , traces the history of policing in America to “slave patrols” in the antebellum South, in which white citizens were expected to help supervise the movements of enslaved Black people. This legacy, he believes, can still be seen in policing today. “The surveillance, the deputization essentially of all white men to be police officers or, in this case, slave patrollers, and then to dispense corporal punishment on the scene are all baked in from the very beginning,” he told NPR last year.

Slave patrols, and the slave codes they enforced, ended after the Civil War and the passage of the 13th amendment, which formally ended slavery “except as a punishment for crime.” But Muhammad notes that former Confederate states quickly used that exception to justify new restrictions. Known as the Black codes, the various rules limited the kinds of jobs African Americans could hold, their rights to buy and own property, and even their movements.

“The genius of the former Confederate states was to say, ‘Oh, well, if all we need to do is make them criminals and they can be put back in slavery, well, then that’s what we’ll do.’ And that’s exactly what the Black codes set out to do. The Black codes, for all intents and purposes, criminalized every form of African American freedom and mobility, political power, economic power, except the one thing it didn’t criminalize was the right to work for a white man on a white man’s terms.” In particular, he said the Ku Klux Klan “took about the business of terrorizing, policing, surveilling, and controlling Black people. … The Klan totally dominates the machinery of justice in the South.”

When, during what became known as the Great Migration, millions of African Americans fled the still largely agrarian South for opportunities in the thriving manufacturing centers of the North, they discovered that metropolitan police departments tended to enforce the law along racial and ethnic lines, with newcomers overseen by those who came before. “There was an early emphasis on people whose status was just a tiny notch better than the folks whom they were focused on policing,” Muhammad said. “And so the Anglo-Saxons are policing the Irish or the Germans are policing the Irish. The Irish are policing the Poles.” And then arrived a wave of Black Southerners looking for a better life.

In his groundbreaking work, “ The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America ,” Muhammad argues that an essential turning point came in the early 1900s amid efforts to professionalize police forces across the nation, in part by using crime statistics to guide law enforcement efforts. For the first time, Americans with European roots were grouped into one broad category, white, and set apart from the other category, Black.

Citing Muhammad’s research, Harvard historian Jill Lepore has summarized the consequences this way : “Police patrolled Black neighborhoods and arrested Black people disproportionately; prosecutors indicted Black people disproportionately; juries found Black people guilty disproportionately; judges gave Black people disproportionately long sentences; and, then, after all this, social scientists, observing the number of Black people in jail, decided that, as a matter of biology, Black people were disproportionately inclined to criminality.”

“History shows that crime data was never objective in any meaningful sense,” Muhammad wrote. Instead, crime statistics were “weaponized” to justify racial profiling, police brutality, and ever more policing of Black people.

This phenomenon, he believes, has continued well into this century and is exemplified by William J. Bratton, one of the most famous police leaders in recent America history. Known as “America’s Top Cop,” Bratton led police departments in his native Boston, Los Angeles, and twice in New York, finally retiring in 2016.

Bratton rejected notions that crime was a result of social and economic forces, such as poverty, unemployment, police practices, and racism. Instead, he said in a 2017 speech, “It is about behavior.” Through most of his career, he was a proponent of statistically-based “predictive” policing — essentially placing forces in areas where crime numbers were highest, focused on the groups found there.

Bratton argued that the technology eliminated the problem of prejudice in policing, without ever questioning potential bias in the data or algorithms themselves — a significant issue given the fact that Black Americans are arrested and convicted of crimes at disproportionately higher rates than whites. This approach has led to widely discredited practices such as racial profiling and “stop-and-frisk.” And, Muhammad notes, “There is no research consensus on whether or how much violence dropped in cities due to policing.”

Gathering numbers

In 2015 The Washington Post began tracking every fatal shooting by an on-duty officer, using news stories, social media posts, and police reports in the wake of the fatal police shooting of Brown, a Black teenager in Ferguson, Mo. According to the newspaper, Black Americans are killed by police at twice the rate of white Americans, and Hispanic Americans are also killed by police at a disproportionate rate.

Such efforts have proved useful for researchers such as economist Rajiv Sethi .

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute , Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers, a difficult task given that data from such encounters is largely unavailable from police departments. Instead, Sethi and his team of researchers have turned to information collected by websites and news organizations including The Washington Post and The Guardian, merged with data from other sources such as the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Census, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A Joy Foundation Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Rajiv Sethi is investigating the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers,

Courtesy photo

They have found that exposure to deadly force is highest in the Mountain West and Pacific regions relative to the mid-Atlantic and northeastern states, and that racial disparities in relation to deadly force are even greater than the national numbers imply. “In the country as a whole, you’re about two to three times more likely to face deadly force if you’re Black than if you are white” said Sethi. “But if you look at individual cities separately, disparities in exposure are much higher.”

Examining the characteristics associated with police departments that experience high numbers of lethal encounters is one way to better understand and address racial disparities in policing and the use of violence, Sethi said, but it’s a massive undertaking given the decentralized nature of policing in America. There are roughly 18,000 police departments in the country, and more than 3,000 sheriff’s offices, each with its own approaches to training and selection.

“They behave in very different ways, and what we’re finding in our current research is that they are very different in the degree to which they use deadly force,” said Sethi. To make real change, “You really need to focus on the agency level where organizational culture lies, where selection and training protocols have an effect, and where leadership can make a difference.”

Sethi pointed to the example of Camden, N.J., which disbanded and replaced its police force in 2013, initially in response to a budget crisis, but eventually resulting in an effort to fundamentally change the way the police engaged with the community. While there have been improvements, including greater witness cooperation, lower crime, and fewer abuse complaints, the Camden case doesn’t fit any particular narrative, said Sethi, noting that the number of officers actually increased as part of the reform. While the city is still faced with its share of problems, Sethi called its efforts to rethink policing “important models from which we can learn.”

Fighting vs. preventing crime

For many analysts, the real problem with policing in America is the fact that there is simply too much of it. “We’ve seen since the mid-1970s a dramatic increase in expenditures that are associated with expanding the criminal legal system, including personnel and the tasks we ask police to do,” said Sandra Susan Smith , Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice at HKS, and the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. “And at the same time we see dramatic declines in resources devoted to social welfare programs.”

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson, but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work,” said Brandon Terry, assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies.

Kris Snibble/Harvard file photo

Smith’s comment highlights a key argument embraced by many activists and experts calling for dramatic police reform: diverting resources from the police to better support community services including health care, housing, and education, and stronger economic and job opportunities. They argue that broader support for such measures will decrease the need for policing, and in turn reduce violent confrontations, particularly in over-policed, economically disadvantaged communities, and communities of color.

For Brandon Terry , that tension took the form of an ice container during his Baltimore high school chemistry final. The frozen cubes were placed in the middle of the classroom to help keep the students cool as a heat wave sent temperatures soaring. “That was their solution to the building’s lack of air conditioning,” said Terry, a Harvard assistant professor of African and African American Studies and social studies. “Just grab an ice cube.”

Terry’s story is the kind many researchers cite to show the negative impact of underinvesting in children who will make up the future population, and instead devoting resources toward policing tactics that embrace armored vehicles, automatic weapons, and spy planes. Terry’s is also the kind of tale promoted by activists eager to defund the police, a movement begun in the late 1960s that has again gained momentum as the death toll from violent encounters mounts. A scholar of Martin Luther King Jr., Terry said the Civil Rights leader’s views on the Vietnam War are echoed in the calls of activists today who are pressing to redistribute police resources.

“King thought that the idea of spending many orders of magnitude more for an unjust war than we did for the abolition of poverty and the abolition of ghettoization was a moral travesty, and it reflected a kind of sickness at the core of our society,” said Terry. “And part of what the defund model is based upon is a similar moral criticism, that these budgets reflect priorities that we have, and our priorities are broken.”

Terry also thinks the policing debate needs to be expanded to embrace a fuller understanding of what it means for people to feel truly safe in their communities. He highlights the work of sociologist Chris Muller and Harvard’s Robert Sampson, who have studied racial disparities in exposures to lead and the connections between a child’s early exposure to the toxic metal and antisocial behavior. Various studies have shown that lead exposure in children can contribute to cognitive impairment and behavioral problems, including heightened aggression.

“You can have all the armored personnel carriers you want in Ferguson,” said Terry, “but public safety is more likely to come from redressing environmental pollution, poor education, and unfair work.”

Policing and criminal justice system

Alexandra Natapoff , Lee S. Kreindler Professor of Law, sees policing as inexorably linked to the country’s criminal justice system and its long ties to racism.

“Policing does not stand alone or apart from how we charge people with crimes, or how we convict them, or how we treat them once they’ve been convicted,” she said. “That entire bundle of official practices is a central part of how we govern, and in particular, how we have historically governed Black people and other people of color, and economically and socially disadvantaged populations.”

Unpacking such a complicated issue requires voices from a variety of different backgrounds, experiences, and fields of expertise who can shine light on the problem and possible solutions, said Natapoff, who co-founded a new lecture series with HLS Professor Andrew Crespo titled “ Policing in America .”

In recent weeks the pair have hosted Zoom discussions on topics ranging from qualified immunity to the Black Lives Matter movement to police unions to the broad contours of the American penal system. The series reflects the important work being done around the country, said Natapoff, and offers people the chance to further “engage in dialogue over these over these rich, complicated, controversial issues around race and policing, and governance and democracy.”

Courts and mass incarceration

Much of Natapoff’s recent work emphasizes the hidden dangers of the nation’s misdemeanor system. In her book “ Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal ,” Natapoff shows how the practice of stopping, arresting, and charging people with low-level offenses often sends them down a devastating path.

“This is how most people encounter the criminal apparatus, and it’s the first step of mass incarceration, the initial net that sweeps people of color disproportionately into the criminal system,” said Natapoff. “It is also the locus that overexposes Black people to police violence. The implications of this enormous net of police and prosecutorial authority around minor conduct is central to understanding many of the worst dysfunctions of our criminal system.”

One consequence is that Black and brown people are incarcerated at much higher rates than white people. America has approximately 2.3 million people in federal, state, and local prisons and jails, according to a 2020 report from the nonprofit the Prison Policy Initiative. According to a 2018 report from the Sentencing Project, Black men are 5.9 times as likely to be incarcerated as white men and Hispanic men are 3.1 times as likely.

Reducing mass incarceration requires shrinking the misdemeanor net “along all of its axes” said Natapoff, who supports a range of reforms including training police officers to both confront and arrest people less for low-level offenses, and the policies of forward-thinking prosecutors willing to “charge fewer of those offenses when police do make arrests.”

She praises the efforts of Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins in Massachusetts and George Gascón, the district attorney in Los Angeles County, Calif., who have pledged to stop prosecuting a range of misdemeanor crimes such as resisting arrest, loitering, trespassing, and drug possession. “If cities and towns across the country committed to that kind of reform, that would be a profoundly meaningful change,” said Natapoff, “and it would be a big step toward shrinking our entire criminal apparatus.”

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner cites the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Sentencing reform

Another contributing factor in mass incarceration is sentencing disparities.

A recent Harvard Law School study found that, as is true nationally, people of color are “drastically overrepresented in Massachusetts state prisons.” But the report also noted that Black and Latinx people were less likely to have their cases resolved through pretrial probation — a way to dismiss charges if the accused meet certain conditions — and receive much longer sentences than their white counterparts.

Retired U.S. Judge Nancy Gertner also notes the need to reform federal sentencing guidelines, arguing that all too often they have been proven to be biased and to result in packing the nation’s jails and prisons. She points to the way the 1994 Crime Bill (legislation sponsored by then-Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware) ushered in much harsher drug penalties for crack than for powder cocaine. This tied the hands of judges issuing sentences and disproportionately punished people of color in the process. “The disparity in the treatment of crack and cocaine really was backed up by anecdote and stereotype, not by data,” said Gertner, a lecturer at HLS. “There was no data suggesting that crack was infinitely more dangerous than cocaine. It was the young Black predator narrative.”

The First Step Act, a bipartisan prison reform bill aimed at reducing racial disparities in drug sentencing and signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2018, is just what its name implies, said Gertner.

“It reduces sentences to the merely inhumane rather than the grotesque. We still throw people in jail more than anybody else. We still resort to imprisonment, rather than thinking of other alternatives. We still resort to punishment rather than other models. None of that has really changed. I don’t deny the significance of somebody getting out of prison a year or two early, but no one should think that that’s reform.”

Not just bad apples

Reform has long been a goal for federal leaders. Many heralded Obama-era changes aimed at eliminating racial disparities in policing and outlined in the report by The President’s Task Force on 21st Century policing. But HKS’s Smith saw them as largely symbolic. “It’s a nod to reform. But most of the reforms that are implemented in this country tend to be reforms that nibble around the edges and don’t really make much of a difference.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Smith, who cites studies suggesting a majority of Americans hold negative biases against Black and brown people, and that unconscious prejudices and stereotypes are difficult to erase.

“Experiments show that you can, in the context of a day, get people to think about race differently, and maybe even behave differently. But if you follow up, say, a week, or two weeks later, those effects are gone. We don’t know how to produce effects that are long-lasting. We invest huge amounts to implement such police reforms, but most often there’s no empirical evidence to support their efficacy.”

Even the early studies around the effectiveness of body cameras suggest the devices do little to change “officers’ patterns of behavior,” said Smith, though she cautions that researchers are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data.

And though police body cameras have caught officers in unjust violence, much of the general public views the problem as anomalous.

“Despite what many people in low-income communities of color think about police officers, the broader society has a lot of respect for police and thinks if you just get rid of the bad apples, everything will be fine,” Smith added. “The problem, of course, is this is not just an issue of bad apples.”

Efforts such as diversifying police forces and implicit bias training do little to change behaviors and reduce violent conduct against people of color, said Sandra Susan Smith, a professor of criminal justice Harvard Kennedy School.

Community-based ways forward

Still Smith sees reason for hope and possible ways forward involving a range of community-based approaches. As part of the effort to explore meaningful change, Smith, along with Christopher Winship , Diker-Tishman Professor of Sociology at Harvard University and a member of the senior faculty at HKS, have organized “ Reimagining Community Safety: A Program in Criminal Justice Speaker Series ” to better understand the perspectives of practitioners, policymakers, community leaders, activists, and academics engaged in public safety reform.

Some community-based safety models have yielded important results. Smith singles out the Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets program (known as CAHOOTS ) in Eugene, Ore., which supplements police with a community-based public safety program. When callers dial 911 they are often diverted to teams of workers trained in crisis resolution, mental health, and emergency medicine, who are better equipped to handle non-life-threatening situations. The numbers support her case. In 2017 the program received 25,000 calls, only 250 of which required police assistance. Training similar teams of specialists who don’t carry weapons to handle all traffic stops could go a long way toward ending violent police encounters, she said.

“Imagine you have those kinds of services in play,” said Smith, paired with community-based anti-violence program such as Cure Violence , which aims to stop violence in targeted neighborhoods by using approaches health experts take to control disease, such as identifying and treating individuals and changing social norms. Together, she said, these programs “could make a huge difference.”

At Harvard Law School, students have been studying how an alternate 911-response team might function in Boston. “We were trying to move from thinking about a 911-response system as an opportunity to intervene in an acute moment, to thinking about what it would look like to have a system that is trying to help reweave some of the threads of community, a system that is more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” said HLS Professor Rachel Viscomi, who directs the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program and oversaw the research.

The forthcoming report, compiled by two students in the HLS clinic, Billy Roberts and Anna Vande Velde, will offer officials a range of ideas for how to think about community safety that builds on existing efforts in Boston and other cities, said Viscomi.

But Smith, like others, knows community-based interventions are only part of the solution. She applauds the Justice Department’s investigation into the Ferguson Police Department after the shooting of Brown. The 102-page report shed light on the department’s discriminatory policing practices, including the ways police disproportionately targeted Black residents for tickets and fines to help balance the city’s budget. To fix such entrenched problems, state governments need to rethink their spending priorities and tax systems so they can provide cities and towns the financial support they need to remain debt-free, said Smith.

Rethinking the 911-response system to being one that is “more focused on healing than just on stopping harm” is part of the student-led research under the direction of Law School Professor Rachel Viscomi, who heads up the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

“Part of the solution has to be a discussion about how government is funded and how a city like Ferguson got to a place where government had so few resources that they resorted to extortion of their residents, in particular residents of color, in order to make ends meet,” she said. “We’ve learned since that Ferguson is hardly the only municipality that has struggled with funding issues and sought to address them through the oppression and repression of their politically, socially, and economically marginalized Black and Latino residents.”

Police contracts, she said, also need to be reexamined. The daughter of a “union man,” Smith said she firmly supports officers’ rights to union representation to secure fair wages, health care, and safe working conditions. But the power unions hold to structure police contracts in ways that protect officers from being disciplined for “illegal and unethical behavior” needs to be challenged, she said.

“I think it’s incredibly important for individuals to be held accountable and for those institutions in which they are embedded to hold them to account. But we routinely find that union contracts buffer individual officers from having to be accountable. We see this at the level of the Supreme Court as well, whose rulings around qualified immunity have protected law enforcement from civil suits. That needs to change.”

Other Harvard experts agree. In an opinion piece in The Boston Globe last June, Tomiko Brown-Nagin , dean of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute and the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at HLS, pointed out the Court’s “expansive interpretation of qualified immunity” and called for reform that would “promote accountability.”

“This nation is devoted to freedom, to combating racial discrimination, and to making government accountable to the people,” wrote Brown-Nagin. “Legislators today, like those who passed landmark Civil Rights legislation more than 50 years ago, must take a stand for equal justice under law. Shielding police misconduct offends our fundamental values and cannot be tolerated.”

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Six receive honorary degrees

Harvard recognizes educator, conductor, theoretical physicist, advocate for elderly, writer, and Nobel laureate

Everything counts!

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Bridging social distance, embracing uncertainty, fighting for equity

Student Commencement speeches to tap into themes faced by Class of 2024

June 4, 2020

A Civil Rights Expert Explains the Social Science of Police Racism

Columbia University attorney Alexis J. Hoag discusses the history of how we got to this point and the ways that researchers can help reduce bias against black Americans throughout the legal system

By Lydia Denworth

Protester holds sign during a demonstration in honor of George Floyd on June 2, 2020, in Marin City, Calif.

Justin Sullivan Getty Images

In a now infamous event captured on video, on May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was killed by a Minneapolis police officer outside of a corner store. Derek Chauvin kneeled on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds while two other officers helped to hold him down and a third stood guard nearby. Nearly a year later, in April 2021, a jury convicted Chauvin of second-degree murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. He could face decades in prison (sentencing was expected on June 25). In a highly unusual development, other police officers, including the Minneapolis chief of police, testified against Chauvin.

The three other officers involved, Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao, were indicted on a range of state and federal charges, including violating Floyd’s constitutional rights, failing to intervene to stop Chauvin, and aiding and abetting second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Their trial is scheduled for March 2022.

The 2014 shooting death of Black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., sparked a renewed emphasis on racism and police brutality in the U.S.’s political and cultural conversation. In the past few years many names have been added to the list of Black people killed by police. Despite some efforts to acknowledge and grapple with systemic racism in American institutions, anger and distrust between law enforcement and Black Americans have remained high. But Floyd’s death sparked a new level of outrage. Protests erupted in hundreds of cities around the U.S. in the summer of 2020. Most demonstrations were peaceful. But some turned violent, with police using force against protesters and a small percentage of people setting fire to police cars, looting stores, and defacing or damaging buildings. By July the demonstrations were thought to be the largest protest movement in American history, with some 15 million to 26 million people estimated to have taken part.

In addition to the criminal charges against the officers, Floyd’s death has prompted U.S. Justice Department investigations into the practices of the Minneapolis Police Department. And Democrats in Congress are hoping to pass criminal justice reform legislation named for Floyd. Both reflect the interests of the new administration since Joe Biden took office in January 2021.

In June 2020, at the height of the protests, Scientific American spoke with civil rights attorney Alexis J. Hoag. Hoag is the inaugural practitioner in residence at the Eric H. Holder, Jr., Initiative for Civil and Political Rights at Columbia University. She works with both undergraduates and law school students at Columbia to introduce them to civil rights fieldwork (which she describes as “real issues, real clients, real cases”). Hoag was previously a senior counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Scientific American asked her to share her perspective on the history that has brought the U.S. to a breaking point—and her ideas for how to make substantive improvements in how law enforcement and courts treat Black people in the country.

Why are we seeing this level of protest now?

I think it’s a combination of things. COVID-19 [has had a] disproportionate impact on Black people because of long-standing structural inequalities. Black people are more likely to live in hypersegregated low-income areas that are underresourced. And Black people are more prone to the very preexisting conditions that make people vulnerable to COVID-19 because of structural inequality and lack of access to health care. We’ve all been cooped up for 10 to 11 weeks. Forty million people [in the U.S.] are unemployed. And there was something egregious about the video that circulated of George Floyd being executed for the suspicion of tendering a counterfeit $20 bill. And I want to stress “suspicion” because we still don’t know. That became a death sentence for him.

The violence that has been rendered against Black bodies has gone on for centuries. Now it’s out there for everyone to see. And the response, which is hopeful and heartening to me, is that people—not just Black Americans—in this country are really disturbed and appropriately so.

What are the important historical factors that have led up to this point?

I lean so heavily on the unique history of this country and the fact that we enslaved people, Black people. To hold people in bondage as property, you had to look at them as less than human. You see that continuing to happen today in [what] I refer to as the criminal legal system, not the justice system, because it is not just. We are not there yet. As an appellate attorney, I read a lot of transcripts of trials. And the level of dehumanization that prosecutors use to refer to Black criminal defendants is striking. It’s the verbiage used, that the defendant was “circling” and “hunting” the victim. What hunts and circles? Animals. When you can dehumanize an individual, of course, you can put the person away for a long time, you can sentence him or her to death. And of course, you can put your knee on somebody’s neck for nine minutes because you see them as less than human. It’s a combination of the dehumanization of Black people with the presumption of dangerousness and criminality.

Is racism getting worse? Or has the ubiquity of cell phones and video recordings simply made us more aware of it?

These issues are getting amplified; they’re getting recorded. I think back to the early 1990s and Rodney King’s videotaped beating. That really galvanized people around this issue—an issue that many Black Americans were intimately aware of already—and put it out there for the world to see. Then the response after those officers were acquitted was public demonstrations in 1992 in Los Angeles. I think people would not have been as engaged if we didn’t have that image. Now we walk around with [cameras] in our pockets.

How does the seeming increase in white nationalism fit in?

I don’t know that I would call it an increase. White nationalists, known earlier as white supremacists, first rallied [more than] 150 years ago to violently limit the freedom of newly emancipated Black Americans. Despite federal legislation extending the benefits of citizenship to Black people, white supremacists passed state laws codifying inequality and used violence and intimidation to curtail any Black exercise of freedom. What’s happening now [in June 2020] is that we have [a presidential] administration that welcomes and encourages white nationalist views and activities.

Have events in Ferguson and other cities, and the Black Lives Matter movement as a whole, had any effect on policing?

Ferguson was a massive wake-up call. There was a brief glimmer of hope. There was a mechanism in place: the Law Enforcement Misconduct [Statute]. It [is] a federal law the Department of Justice could rely on to investigate Ferguson, to investigate police misconduct in Baltimore [where Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old Black man, died while being transported in a police vehicle in what was ruled to be a homicide]. That law was grossly underutilized by Attorney General William Barr. Who the administration is and who the chief law-enforcement officer of this country is—the attorney general of the U.S.—makes a difference. We’ve seen a massive rollback in the responsiveness of the [Trump] administration [in taking] a hard look at injustice and at rampant police misconduct.

The other step back that the country has taken is to characterize officers involved in misconduct as “a few bad apples.” I think we all need to admit that it’s not a few bad apples; it’s a rotten apple tree. The history of policing in the South [was driven in part by] slave patrols that were monitoring the movement of Black bodies. And in the North, law enforcement was privately funded [and often involved protecting property and goods]. The police got started targeting poor people and Black people.

What would you like to see happen now?

I think there needs to be a really hard conversation nationally and within law enforcement. To use force, police officers have to reasonably believe that their lives are in danger. What is it about Black skin that makes law enforcement feel threatened for their lives? In addition, there are legal mechanisms that need to be examined. “Qualified immunity” as a defense to police misconduct was judicially created in 1982. It shields government officials from being sued for discretionary actions that are performed within their official capacities unless the action violates clearly established federal law. Somebody who is suing an officer for tasing someone while they’re handcuffed has to find a case from the U.S. Supreme Court or the highest court of appeals in their jurisdiction that says that exact act—being handcuffed and tased—is unconstitutional. This is a massive hurdle for a plaintiff.

What are social scientists and researchers doing to help?

Data are currency. We can create a national database of officer misconduct. You have officers such as Derek Chauvin, who had 18 complaints against him and [was] still allowed to operate within the [Minneapolis Police] Department.

The data collection that happens within police departments enabled experts in the stop-and-frisk litigation [against] the [New York City Police Department] to shine a spotlight on gross disparities: the rate of stops and searches of Black and brown men and boys [coupled with] the low rate of actually acquiring contraband. They found that the rate of securing contraband from white individuals who had been stopped and frisked was so much higher because the police were actually using discretion.

There’s powerful data collection that happens in our criminal courts. Studies show that, all factors being equal, judges are rendering longer and harsher sentences for Black defendants. These judges are setting higher bail. You can isolate all these other factors, but race is the difference. That’s very powerful—to be able to document and publish those findings.

There has also been some really good social science research on implicit bias and the way that it operates. We could all take [implicit association tests] on our computers. You could do a training with your employees. To start with, there is this recognition, this acknowledgment, that we all have implicit bias.

And how do we use that information and not just let people off the hook?

Let’s talk about it. Social science research shows that when there’s recognition that we harbor implicit bias, that awareness can help mitigate [such] bias impacting our daily interactions and decisions.

What about people’s decision to protest during the pandemic? Are you worried that protesters will get sick and spread COVID-19?

Of course. I worry that there will be a second wave of infections. But I think that also speaks to how pressing the issue is and how strongly people feel about it—that they are risking their lives to bring attention to the rampant and lethal mistreatment of Black and brown bodies at the hands of law enforcement.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

10 things we know about race and policing in the U.S.

Days of protests across the United States in the wake of George Floyd’s death in the custody of Minneapolis police have brought new attention to questions about police officers’ attitudes toward black Americans, protesters and others. The public’s views of the police, in turn, are also in the spotlight. Here’s a roundup of Pew Research Center survey findings from the past few years about the intersection of race and law enforcement.

How we did this

Most of the findings in this post were drawn from two previous Pew Research Center reports: one on police officers and policing issues published in January 2017, and one on the state of race relations in the United States published in April 2019. We also drew from a September 2016 report on how black and white Americans view police in their communities. (The questions asked for these reports, as well as their responses, can be found in the reports’ accompanying “topline” file or files.)

The 2017 police report was based on two surveys. One was of 7,917 law enforcement officers from 54 police and sheriff’s departments across the U.S., designed and weighted to represent the population of officers who work in agencies that employ at least 100 full-time sworn law enforcement officers with general arrest powers, and conducted between May and August 2016. The other survey, of the general public, was conducted via the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) in August and September 2016 among 4,538 respondents. (The 2016 report on how blacks and whites view police in their communities also was based on that survey.) More information on methodology is available here .

The 2019 race report was based on a survey conducted in January and February 2019. A total of 6,637 people responded, out of 9,402 who were sampled, for a response rate of 71%. The respondents included 5,599 from the ATP and oversamples of 530 non-Hispanic black and 508 Hispanic respondents sampled from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. More information on methodology is available here .

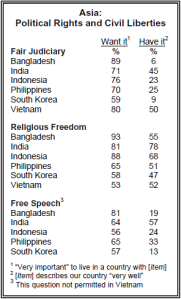

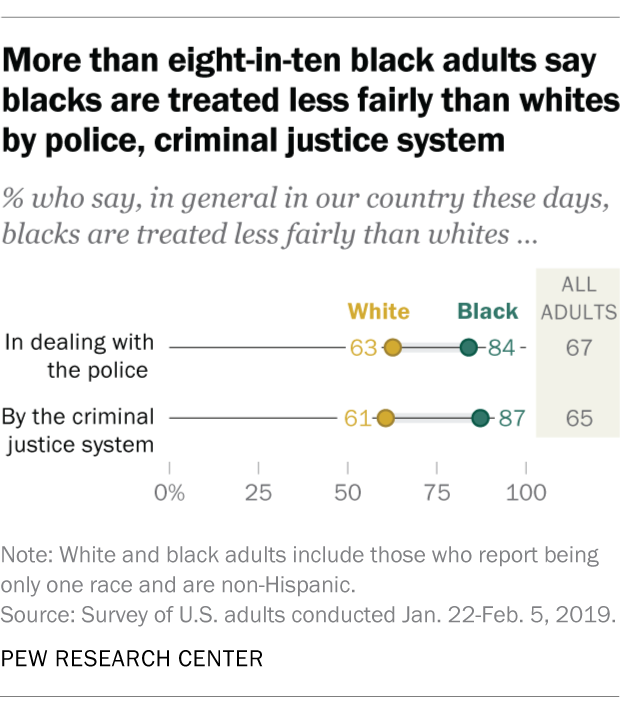

Majorities of both black and white Americans say black people are treated less fairly than whites in dealing with the police and by the criminal justice system as a whole. In a 2019 Center survey , 84% of black adults said that, in dealing with police, blacks are generally treated less fairly than whites; 63% of whites said the same. Similarly, 87% of blacks and 61% of whites said the U.S. criminal justice system treats black people less fairly.

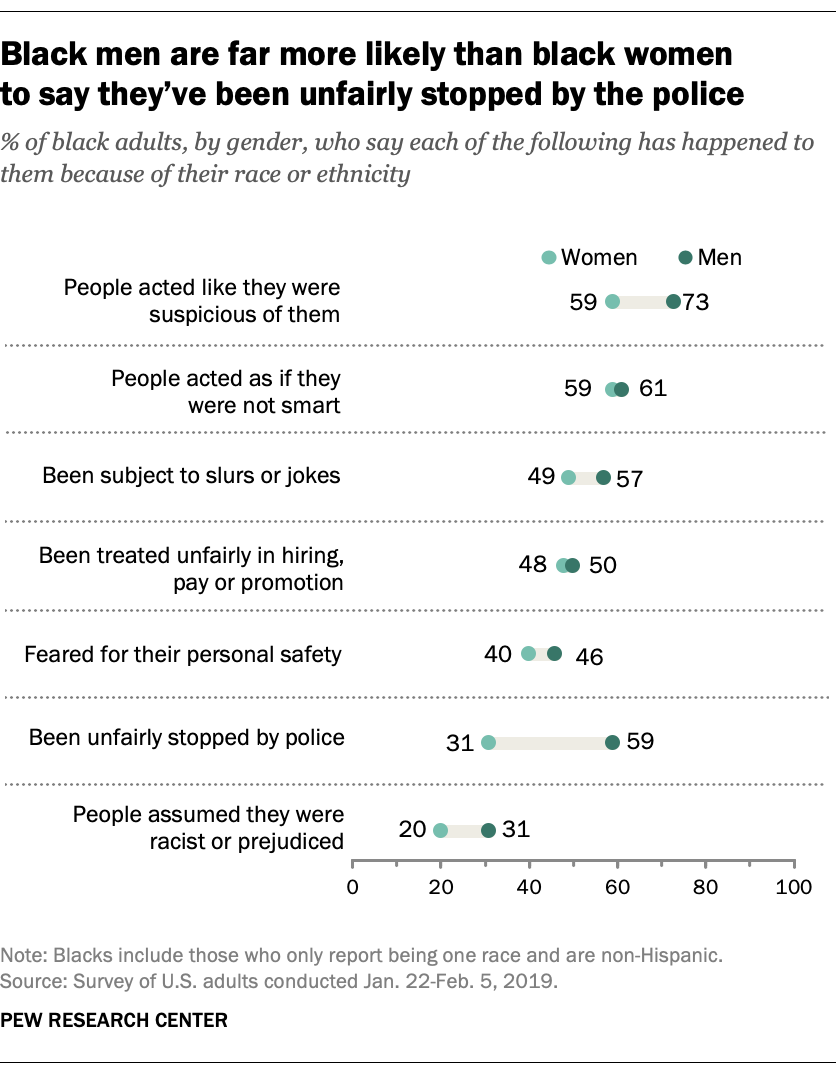

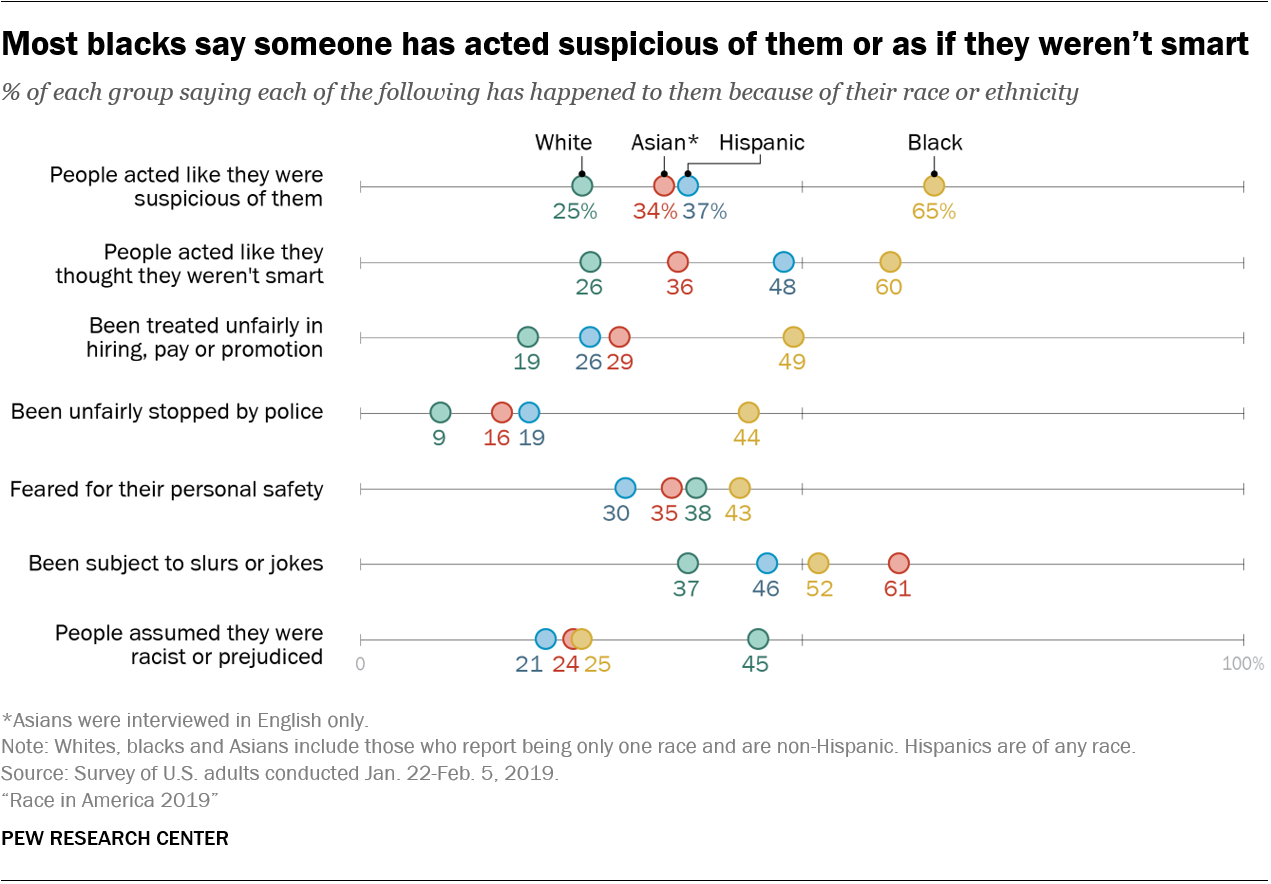

Black adults are about five times as likely as whites to say they’ve been unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity (44% vs. 9%), according to the same survey. Black men are especially likely to say this : 59% say they’ve been unfairly stopped, versus 31% of black women.

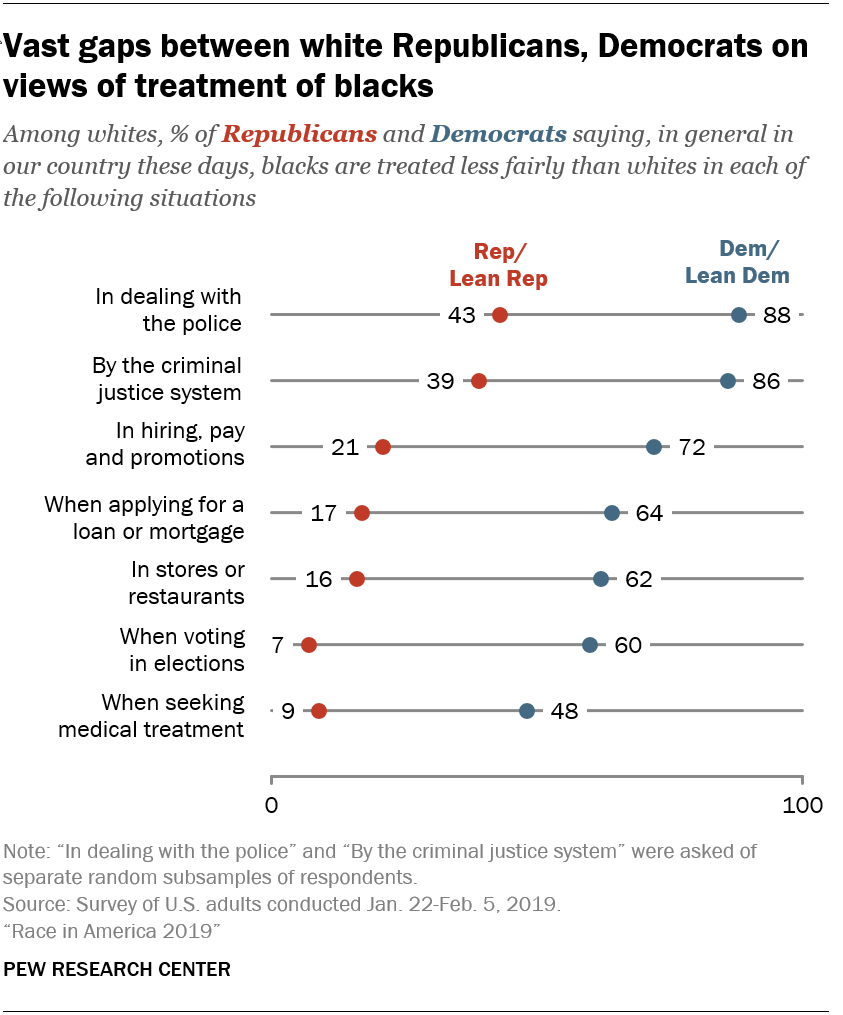

White Democrats and white Republicans have vastly different views of how black people are treated by police and the wider justice system. Overwhelming majorities of white Democrats say black people are treated less fairly than whites by the police (88%) and the criminal justice system (86%), according to the 2019 poll. About four-in-ten white Republicans agree (43% and 39%, respectively).

Nearly two-thirds of black adults (65%) say they’ve been in situations where people acted as if they were suspicious of them because of their race or ethnicity, while only a quarter of white adults say that’s happened to them. Roughly a third of both Asian and Hispanic adults (34% and 37%, respectively) say they’ve been in such situations, the 2019 survey found.

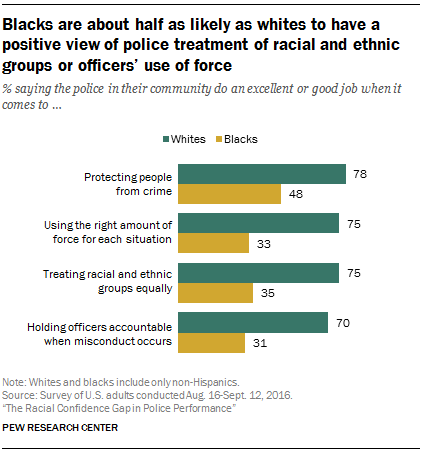

Black Americans are far less likely than whites to give police high marks for the way they do their jobs . In a 2016 survey, only about a third of black adults said that police in their community did an “excellent” or “good” job in using the right amount of force (33%, compared with 75% of whites), treating racial and ethnic groups equally (35% vs. 75%), and holding officers accountable for misconduct (31% vs. 70%).

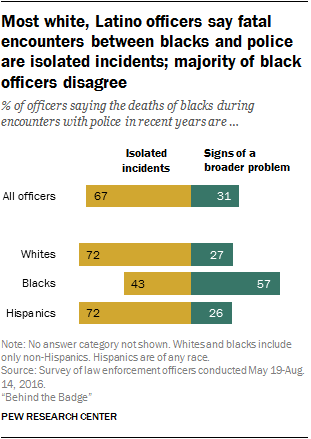

In the past, police officers and the general public have tended to view fatal encounters between black people and police very differently. In a 2016 survey of nearly 8,000 policemen and women from departments with at least 100 officers, two-thirds said most such encounters are isolated incidents and not signs of broader problems between police and the black community. In a companion survey of more than 4,500 U.S. adults, 60% of the public called such incidents signs of broader problems between police and black people. But the views given by police themselves were sharply differentiated by race: A majority of black officers (57%) said that such incidents were evidence of a broader problem, but only 27% of white officers and 26% of Hispanic officers said so.

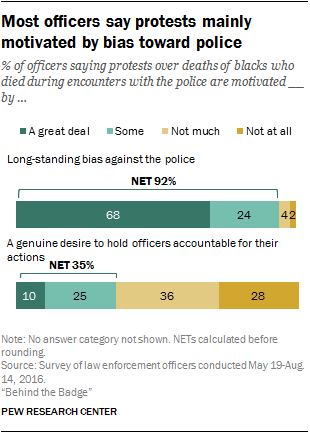

Around two-thirds of police officers (68%) said in 2016 that the demonstrations over the deaths of black people during encounters with law enforcement were motivated to a great extent by anti-police bias; only 10% said (in a separate question) that protesters were primarily motivated by a genuine desire to hold police accountable for their actions. Here as elsewhere, police officers’ views differed by race: Only about a quarter of white officers (27%) but around six-in-ten of their black colleagues (57%) said such protests were motivated at least to some extent by a genuine desire to hold police accountable.

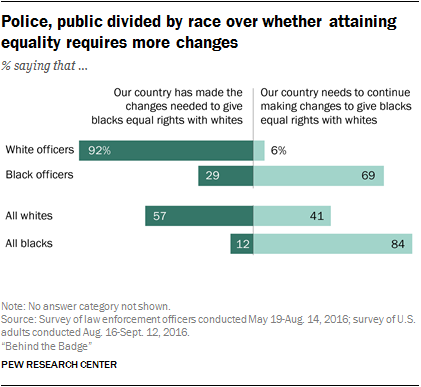

White police officers and their black colleagues have starkly different views on fundamental questions regarding the situation of blacks in American society, the 2016 survey found. For example, nearly all white officers (92%) – but only 29% of their black colleagues – said the U.S. had made the changes needed to assure equal rights for blacks.

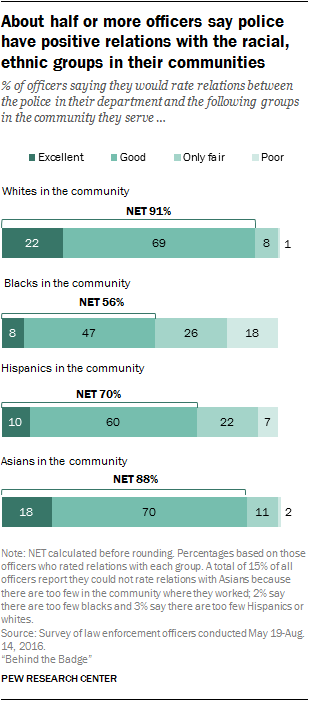

A majority of officers said in 2016 that relations between the police in their department and black people in the community they serve were “excellent” (8%) or “good” (47%). However, far higher shares saw excellent or good community relations with whites (91%), Asians (88%) and Hispanics (70%). About a quarter of police officers (26%) said relations between police and black people in their community were “only fair,” while nearly one-in-five (18%) said they were “poor” – with black officers far more likely than others to say so. (These percentages are based on only those officers who offered a rating.)

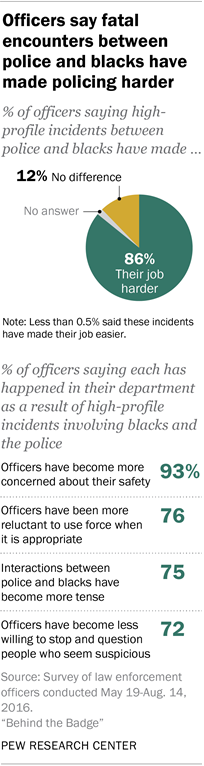

An overwhelming majority of police officers (86%) said in 2016 that high-profile fatal encounters between black people and police officers had made their jobs harder . Sizable majorities also said such incidents had made their colleagues more worried about safety (93%), heightened tensions between police and blacks (75%), and left many officers reluctant to use force when appropriate (76%) or to question people who seemed suspicious (72%).

- Criminal Justice

- Discrimination & Prejudice

- Racial Bias & Discrimination

Drew DeSilver is a senior writer at Pew Research Center .

Michael Lipka is an associate director focusing on news and information research at Pew Research Center .

Dalia Fahmy is a senior writer/editor focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

What the data says about crime in the U.S.

Fewer than 1% of federal criminal defendants were acquitted in 2022, before release of video showing tyre nichols’ beating, public views of police conduct had improved modestly, black americans differ from other u.s. adults over whether individual or structural racism is a bigger problem, violent crime is a key midterm voting issue, but what does the data say, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 07 February 2024

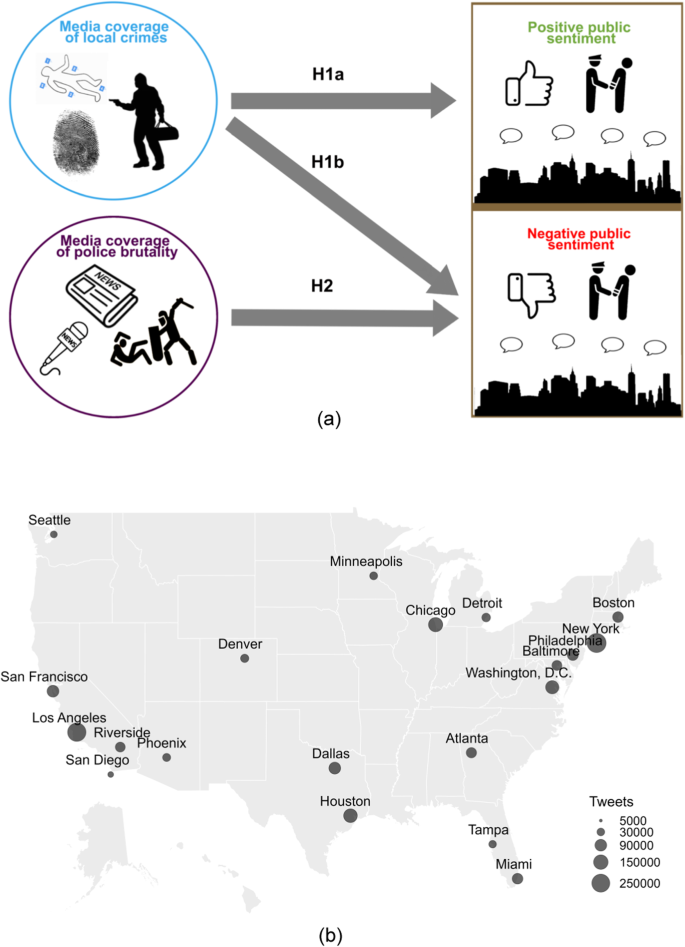

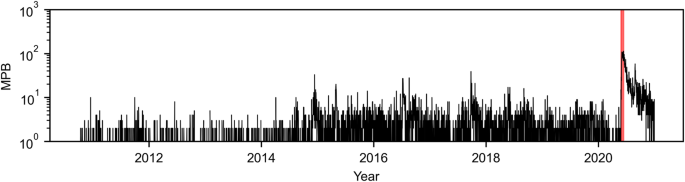

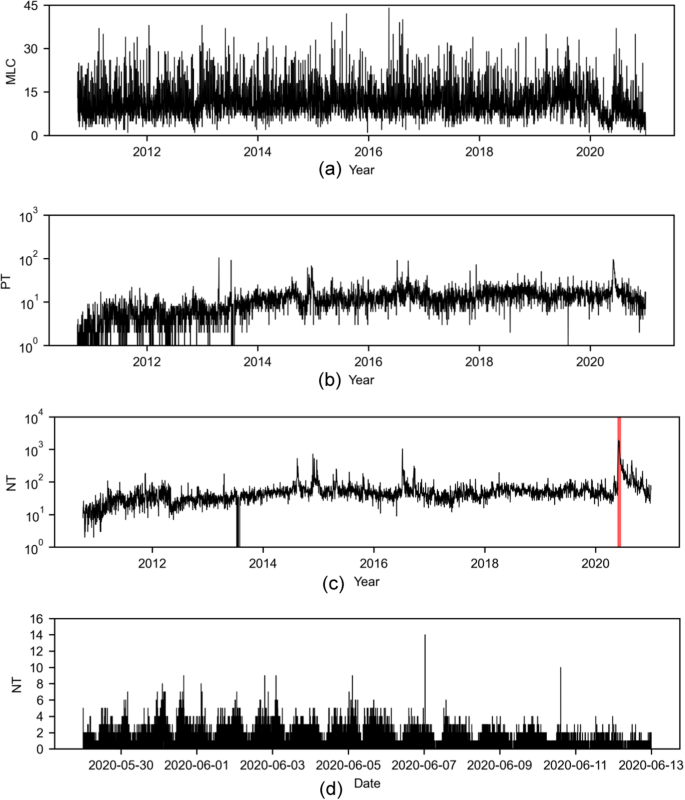

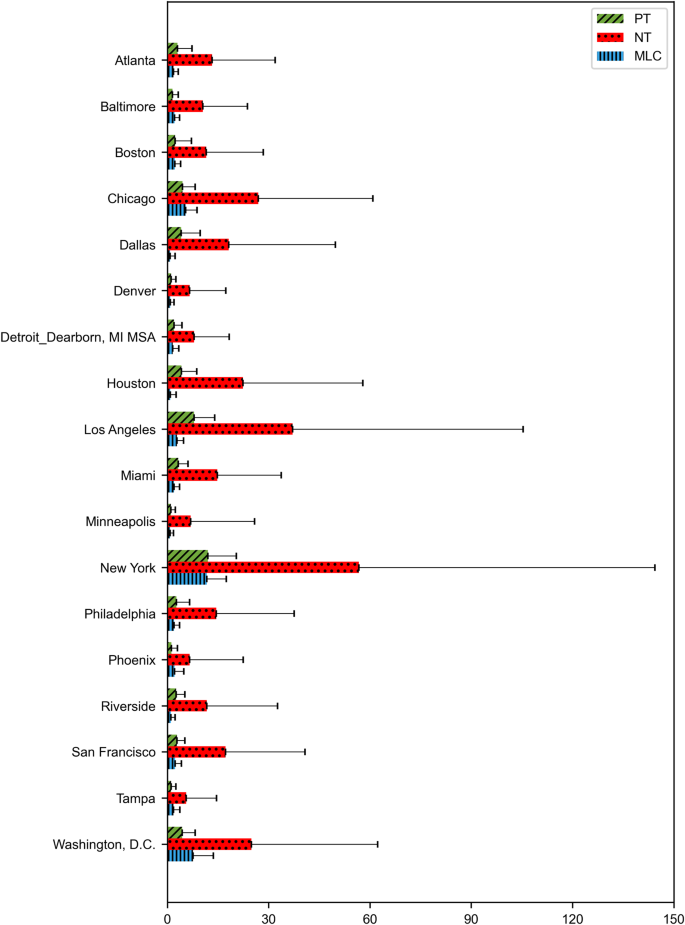

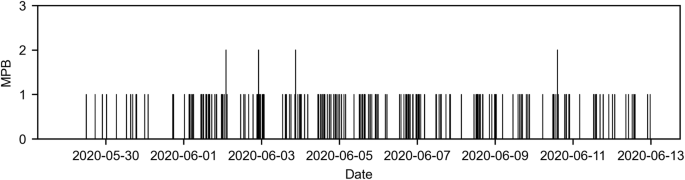

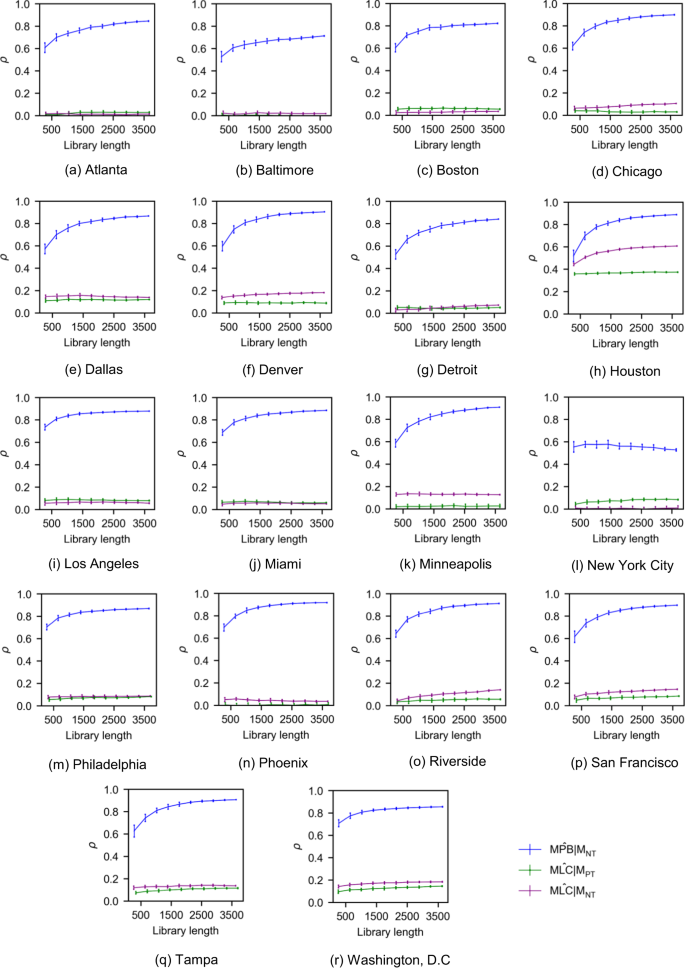

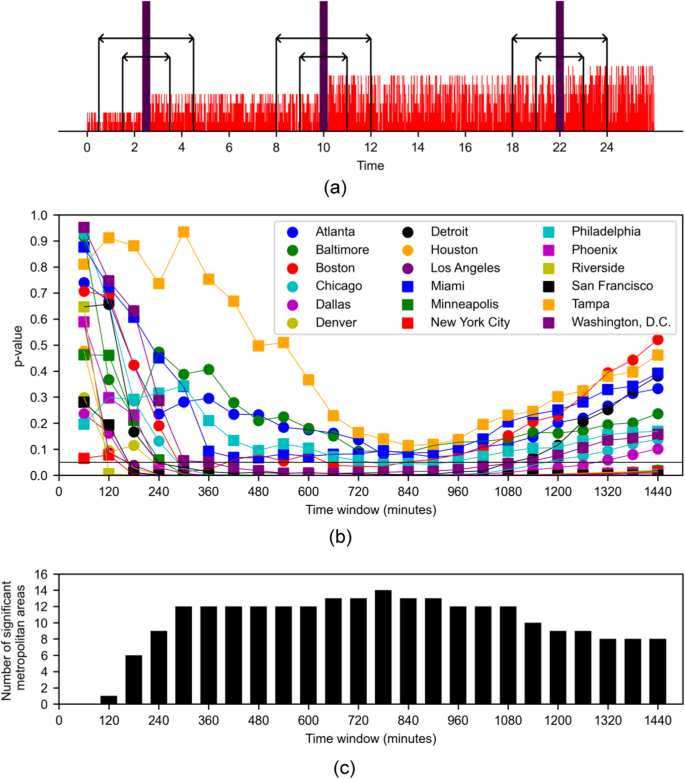

Understanding the role of media in the formation of public sentiment towards the police