- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is Down Syndrome?

Causes and risk factors, living with down syndrome.

- Complications

- Next in Down Syndrome Guide Down Syndrome: Symptoms and Intellectual and Physical Traits

Down syndrome is a lifelong genetic condition that begins to have effects before birth and can significantly impact many aspects of a person’s life.

People who have Down syndrome can experience physical effects as well as cognitive challenges. However, the severity of the condition varies from person to person, and many people living with Down syndrome can lead happy, productive, and healthy lives.

This article describes the types of Down syndrome, its causes, risk factors, symptoms, screening tests, and long-term outlook.

manonallard / Getty Images

Types of Down Syndrome

Down syndrome is congenital, which means that it is present at birth. In fact, Down syndrome is present at conception. The condition occurs when a fertilized egg has an extra copy of chromosome 21. Down syndrome is also called trisomy 21.

The types of Down syndrome differ based on chromosomal patterns, as follows:

- Trisomy 21 : This is the most common type of Down syndrome. It occurs when a person has three copies of chromosome 21 in each cell of their body. A person's typical number of chromosomes is 46 (in 23 pairs). A person with Down syndrome has 47 chromosomes if all other chromosome pairs are typical.

- Mosaic Down syndrome : This type of Down syndrome occurs when there is a mixture of some cells in the body with trisomy 21 and some cells in the body without an extra chromosome 21. The symptoms can be similar to symptoms of full trisomy 21, but sometimes the effects are milder. It is seen in about 2% of people diagnosed with Down syndrome.

- Translocation : This type occurs when a person has extra chromosome 21 genetic material attached to another chromosome. With this type of Down syndrome, the person may have 46 chromosomes in their cells. About 3% of people diagnosed with Down syndrome have this type.

The extra genetic material from the third copy of chromosome 21 causes the body to develop differently. This occurs whether a person has full trisomy 21, mosaic Down syndrome, or translocation.

This produces changes in the developing fetus's physical features. Many of the changes are present at birth, and some can develop as the child grows into adolescence and adulthood.

Risk factors for Down syndrome include:

- Advanced age of the parents, especially females age 35 and older at the time of conception. It's important to understand that if the genetic parents are in an at-risk age, a surrogate who is below the at risk age does not reduce the risk.

- A family history of Down syndrome or another chromosomal disorder in a parent or sibling

Down Syndrome and Genetics

The genetic pattern of Down syndrome occurs due to the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21 in the parents' egg cell or sperm cell. A child should normally receive only one copy of each chromosome from each parent—resulting in two copies of each chromosome in every one of the child’s cells.

When cells from either parent have two copies of any chromosome, this results in trisomy (the presence of a third copy) in all of the growing baby’s cells throughout their life. Trisomy cannot be repaired with any type of medical intervention.

The process that causes an egg cell or a sperm cell to have an extra copy of a chromosome is called nondisjunction. It occurs during the formation of the egg and the sperm cell, prior to the embryo's conception.

Down syndrome is not usually inherited—most people who have Down syndrome are the first in the family to have it, and their parents do not have the condition. However, it can be passed from parent to child if a person who has Down syndrome becomes pregnant or impregnates someone.

How Common Is Down Syndrome?

Down syndrome affects approximately 1 out of every 675 live births.

What Are the Symptoms of Down Syndrome?

Several characteristic physical changes and symptoms occur due to Down syndrome. These changes are often recognizable at birth, but some children might not have obvious features until early childhood.

Many of the physical features—short stature, heavy build, and prominent eyelids—might resemble other family members who do not have Down syndrome, potentially making the condition less recognizable.

Effects of Down syndrome include:

- Skeletal differences

- Short stature

- Heart malformations

- Abnormal lung development

- Intestinal malformations

- Learning difficulties

- Weak immune system

- Hypothyroidism (low function of the thyroid gland)

People who have Down syndrome have a higher-than-average risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia later in life. Sometimes people who have Down syndrome have blood cell abnormalities affecting white blood cells and red blood cells.

Screening for Down Syndrome During Pregnancy

It is possible to identify Down syndrome during pregnancy. Testing and screening are not a standard part of prenatal care, but they can be done at the pregnant person's request.

Sometimes people who are at risk of having a baby with Down syndrome may request a screening test during pregnancy. But some people do not want to screen, even if they know that their baby is at high risk. And some people may ask for a screening test even when they do not have an elevated risk.

First Trimester

A pregnant person can have a quad screen early in pregnancy. This blood test measures hormones in the pregnant person’s blood that might be abnormal if the growing baby has Down syndrome or other congenital problems. The test cannot rule in or rule out Down syndrome.

Second Trimester

Ultrasound testing can examine the fetus’s physical features, potentially identifying some characteristics that can occur with Down syndrome—such as heart malformations. This test can reliably identify developmental differences, but it does not rule in or rule out Down syndrome.

A chromosomal examination can be done with amniocentesis or chorionic villi sampling. These minimally invasive procedures involve collecting a sample of cells that are genetically identical to the baby’s cells. The cells are collected with a needle using ultrasound guidance.

This test can definitively diagnose Down syndrome and specifically identify the type of Down syndrome.

Living with Down syndrome is a challenge for the whole family. Accommodations are often necessary to achieve learning goals and physical development during the toddler and school-age years. Many school districts offer accommodations for people who are living with Down syndrome,

Additionally, parents should seek the assistance of a multidisciplinary healthcare team to get the testing, therapy, and assistive devices needed to optimize quality of life.

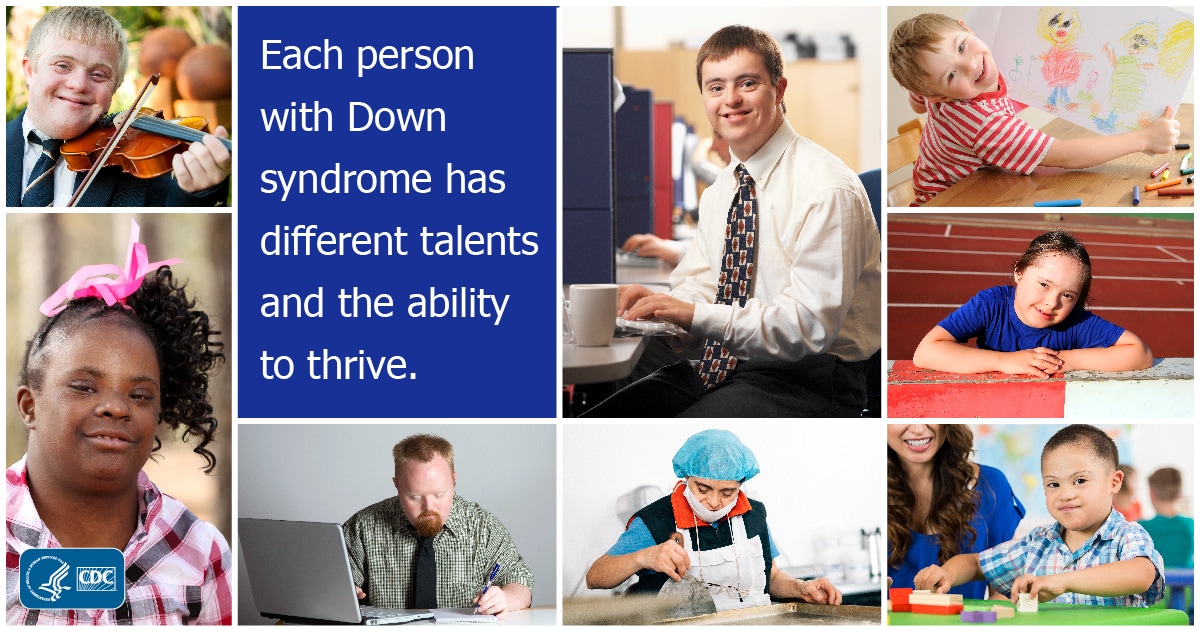

Socializing is possible for people who have Down syndrome. Many people with Down syndrome can develop friendships and a supportive community.

People with Down syndrome can enjoy hobbies and other interests and often pursue those interests with lessons or classes. Many people with Down syndrome also have talents that they work to improve, such as art, music, acting, and more.

Complications of Down Syndrome

Several complications can occur as a result of having Down syndrome. These are not caused directly by the chromosomal abnormality, but they can develop due to the physical changes that occur as a result of the chromosomal abnormality.

Examples of complications include:

- Scoliosis : This abnormal curve of the spine can develop due to spine differences and altered body positioning.

- Heart failure : The heart does not pump enough blood to meet the body's needs. Can be a result of heart defects, high body weight, and low physical activity

- Bowel obstruction : A blockage of the intestine can occur due to intestinal malformation and dietary factors.

- Lung aspiration : Drawing foreign substances into the lungs may occur due to contributing factors such as lung disease, scoliosis, and general weakness.

- Depression : This mood disorder can occur as a result of the impact of coping with physical and cognitive limitations.

- Infections : People who have Down syndrome can have a higher risk of infections, including severe effects of COVID-19 .

Long-Term Outlook for Down Syndrome

In general, many people with Down syndrome can live long and healthy lives. The life expectancy is improving and is now over age 55.

Many people with Down syndrome can work in a job compatible with their physical and cognitive abilities. Support groups and advocacy organizations can often help find resources for job placement, recreational activities, transportation, and financial aid.

In general, people with Down syndrome are not able to live independently. Some may live with their families. Others may live in a group home or assisted living facility equipped to support their limitations and provide appropriate day-to-day help.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about Down syndrome .

National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. Who is at risk for Down syndrome?

Antonarakis SE, Skotko BG, Rafii MS, et al. Down syndrome . Nat Rev Dis Primers . 2020;6(1):9. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-01437

Hendrix JA, Amon A, Abbeduto L, et al. Opportunities, barriers, and recommendations in down syndrome research . Transl Sci Rare Dis . 2021;5(3-4):99-129. doi:10.3233/trd-200090

Chicoine B, Rivelli A, Fitzpatrick V, Chicoine L, Jia G, Rzhetsky A. Prevalence of common disease conditions in a large cohort of individuals with Down syndrome in the United States . J Patient Cent Res Rev . 2021;8(2):86-97. doi:10.17294/2330-0698.1824

Hamaguchi Y, Kondoh T, Fukuda M, et al. Leukopenia, macrocytosis, and thrombocytopenia occur in young adults with Down syndrome . Gene. 2022;835:146663. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2022.146663

Nikjoo S, Rezapour A, Moradi N, Nassiri S, Kabir A. Willingness to pay for Down syndrome screening: a systematics review . Med J Islam Repub Iran . 2022;36:149. doi:10.47176/mjiri.36.149

Lemoine L, Benoît Schneider. Family support for (increasingly) older adults with Down syndrome: factors affecting siblings' involvement . J Intellect Disabil. 2022:17446295221082725. doi:10.1177/17446295221082725

By Heidi Moawad, MD Dr. Moawad is a neurologist and expert in brain health. She regularly writes and edits health content for medical books and publications.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Down syndrome

- The genetic basis of Down syndrome

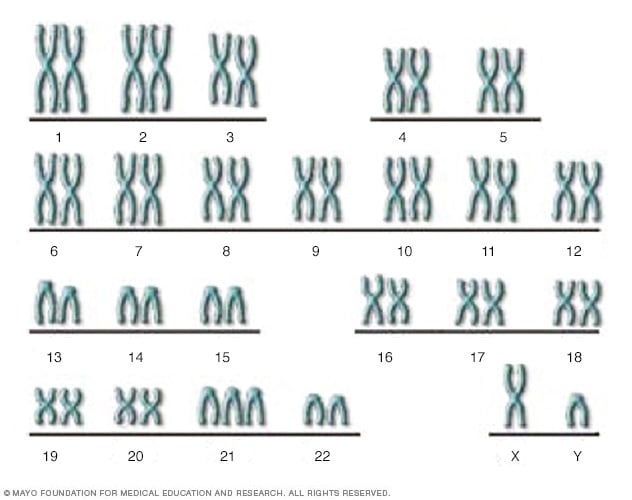

There are 23 pairs of chromosomes, for a total of 46. Half the chromosomes come from the egg (the mother) and half come from the sperm (the father). This XY chromosome pair includes the X chromosome from the egg and the Y chromosome from the sperm. In Down syndrome, there is an additional copy of chromosome 21, resulting in three copies instead of the normal two copies.

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder caused when abnormal cell division results in an extra full or partial copy of chromosome 21. This extra genetic material causes the developmental changes and physical features of Down syndrome.

Down syndrome varies in severity among individuals, causing lifelong intellectual disability and developmental delays. It's the most common genetic chromosomal disorder and cause of learning disabilities in children. It also commonly causes other medical abnormalities, including heart and gastrointestinal disorders.

Better understanding of Down syndrome and early interventions can greatly increase the quality of life for children and adults with this disorder and help them live fulfilling lives.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Each person with Down syndrome is an individual — intellectual and developmental problems may be mild, moderate or severe. Some people are healthy while others have significant health problems such as serious heart defects.

Children and adults with Down syndrome have distinct facial features. Though not all people with Down syndrome have the same features, some of the more common features include:

- Flattened face

- Protruding tongue

- Upward slanting eye lids (palpebral fissures)

- Unusually shaped or small ears

- Poor muscle tone

- Broad, short hands with a single crease in the palm

- Relatively short fingers and small hands and feet

- Excessive flexibility

- Tiny white spots on the colored part (iris) of the eye called Brushfield's spots

- Short height

Infants with Down syndrome may be average size, but typically they grow slowly and remain shorter than other children the same age.

Intellectual disabilities

Most children with Down syndrome have mild to moderate cognitive impairment. Language is delayed, and both short and long-term memory is affected.

When to see a doctor

Children with Down syndrome usually are diagnosed before or at birth. However, if you have any questions regarding your pregnancy or your child's growth and development, talk with your doctor.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Human cells normally contain 23 pairs of chromosomes. One chromosome in each pair comes from your father, the other from your mother.

Down syndrome results when abnormal cell division involving chromosome 21 occurs. These cell division abnormalities result in an extra partial or full chromosome 21. This extra genetic material is responsible for the characteristic features and developmental problems of Down syndrome. Any one of three genetic variations can cause Down syndrome:

- Trisomy 21. About 95 percent of the time, Down syndrome is caused by trisomy 21 — the person has three copies of chromosome 21, instead of the usual two copies, in all cells. This is caused by abnormal cell division during the development of the sperm cell or the egg cell.

- Mosaic Down syndrome. In this rare form of Down syndrome, a person has only some cells with an extra copy of chromosome 21. This mosaic of normal and abnormal cells is caused by abnormal cell division after fertilization.

- Translocation Down syndrome. Down syndrome can also occur when a portion of chromosome 21 becomes attached (translocated) onto another chromosome, before or at conception. These children have the usual two copies of chromosome 21, but they also have additional genetic material from chromosome 21 attached to another chromosome.

There are no known behavioral or environmental factors that cause Down syndrome.

Is it inherited?

Most of the time, Down syndrome isn't inherited. It's caused by a mistake in cell division during early development of the fetus.

Translocation Down syndrome can be passed from parent to child. However, only about 3 to 4 percent of children with Down syndrome have translocation and only some of them inherited it from one of their parents.

When balanced translocations are inherited, the mother or father has some rearranged genetic material from chromosome 21 on another chromosome, but no extra genetic material. This means he or she has no signs or symptoms of Down syndrome, but can pass an unbalanced translocation on to children, causing Down syndrome in the children.

Risk factors

Some parents have a greater risk of having a baby with Down syndrome. Risk factors include:

- Advancing maternal age. A woman's chances of giving birth to a child with Down syndrome increase with age because older eggs have a greater risk of improper chromosome division. A woman's risk of conceiving a child with Down syndrome increases after 35 years of age. However, most children with Down syndrome are born to women under age 35 because younger women have far more babies.

- Being carriers of the genetic translocation for Down syndrome. Both men and women can pass the genetic translocation for Down syndrome on to their children.

- Having had one child with Down syndrome. Parents who have one child with Down syndrome and parents who have a translocation themselves are at an increased risk of having another child with Down syndrome. A genetic counselor can help parents assess the risk of having a second child with Down syndrome.

Complications

People with Down syndrome can have a variety of complications, some of which become more prominent as they get older. These complications can include:

- Heart defects. About half the children with Down syndrome are born with some type of congenital heart defect. These heart problems can be life-threatening and may require surgery in early infancy.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) defects. GI abnormalities occur in some children with Down syndrome and may include abnormalities of the intestines, esophagus, trachea and anus. The risk of developing digestive problems, such as GI blockage, heartburn (gastroesophageal reflux) or celiac disease, may be increased.

- Immune disorders. Because of abnormalities in their immune systems, people with Down syndrome are at increased risk of developing autoimmune disorders, some forms of cancer, and infectious diseases, such as pneumonia.

- Sleep apnea. Because of soft tissue and skeletal changes that lead to the obstruction of their airways, children and adults with Down syndrome are at greater risk of obstructive sleep apnea.

- Obesity. People with Down syndrome have a greater tendency to be obese compared with the general population.

- Spinal problems. Some people with Down syndrome may have a misalignment of the top two vertebrae in the neck (atlantoaxial instability). This condition puts them at risk of serious injury to the spinal cord from overextension of the neck.

- Leukemia. Young children with Down syndrome have an increased risk of leukemia.

- Dementia. People with Down syndrome have a greatly increased risk of dementia — signs and symptoms may begin around age 50. Having Down syndrome also increases the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

- Other problems. Down syndrome may also be associated with other health conditions, including endocrine problems, dental problems, seizures, ear infections, and hearing and vision problems.

For people with Down syndrome, getting routine medical care and treating issues when needed can help with maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Life expectancy

Life spans have increased dramatically for people with Down syndrome. Today, someone with Down syndrome can expect to live more than 60 years, depending on the severity of health problems.

There's no way to prevent Down syndrome. If you're at high risk of having a child with Down syndrome or you already have one child with Down syndrome, you may want to consult a genetic counselor before becoming pregnant.

A genetic counselor can help you understand your chances of having a child with Down syndrome. He or she can also explain the prenatal tests that are available and help explain the pros and cons of testing.

- What is Down syndrome? National Down Syndrome Society. http://www.ndss.org/down-syndrome/what-is-down-syndrome/. Accessed Dec. 16, 2016.

- Down syndrome fact sheet. National Down Syndrome Society. http://www.ndss.org/Down-Syndrome/Down-Syndrome-Facts/. Accessed Dec. 16, 2016.

- Messerlian GM, et al. Down syndrome: Overview of prenatal screening. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed Dec. 16, 2016.

- National Library of Medicine. Down syndrome. Genetics Home Reference. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/down-syndrome. Accessed Dec. 16, 2016.

- Facts about Down syndrome. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/downsyndrome.html. Accessed Dec. 16, 2016.

- Down syndrome. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/down/conditioninfo/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed Dec. 16, 2016.

- Frequently asked questions. Prenatal genetic diagnostic tests. FAQ164. Pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/-/media/For-Patients/faq164.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20161216T1208042192. Accessed Dec. 16, 2016.

- Ostermaier KK. Down syndrome: Management. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed Dec. 22, 2016.

- Ostermaier KK. Down syndrome: Clinical features and diagnosis. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed Jan. 10, 2017.

- Gabbe SG, et al., eds. Genetic screening and prenatal genetic diagnosis. In: Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders Elsevier; 2017.

- Rink BD, et al. Screening for fetal aneuploidy. Seminars in Perinatology. 2016;40:35.

- Bunt CW, et al. The role of the family physician in the care of children with Down syndrome. American Family Physician. 2014;90:851.

- Butler Tobah YS (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Jan. 26, 2017.

Associated Procedures

- Amniocentesis

- Genetic testing

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Facts about Down Syndrome

Down syndrome is a condition in which a person has an extra chromosome.

What is Down Syndrome?

Down syndrome is a condition in which a person has an extra chromosome. Chromosomes are small “packages” of genes in the body. They determine how a baby’s body forms and functions as it grows during pregnancy and after birth. Typically, a baby is born with 46 chromosomes. Babies with Down syndrome have an extra copy of one of these chromosomes, chromosome 21. A medical term for having an extra copy of a chromosome is ‘trisomy.’ Down syndrome is also referred to as Trisomy 21. This extra copy changes how the baby’s body and brain develop, which can cause both mental and physical challenges for the baby.

People with Down syndrome usually have an IQ (a measure of intelligence) in the mildly-to-moderately low range and are slower to speak than other children.

Some common physical features of Down syndrome include:

- A flattened face, especially the bridge of the nose

- Almond-shaped eyes that slant up

- A short neck

- A tongue that tends to stick out of the mouth

- Tiny white spots on the iris (colored part) of the eye

- Small hands and feet

- A single line across the palm of the hand (palmar crease)

- Small pinky fingers that sometimes curve toward the thumb

- Poor muscle tone or loose joints

- Shorter in height as children and adults

How Many Babies are Born with Down Syndrome?

Down syndrome remains the most common chromosomal condition diagnosed in the United States. Each year, about 6,000 babies born in the United States have Down syndrome. This means that Down syndrome occurs in about 1 in every 700 babies. 1

Types of Down Syndrome

There are three types of Down syndrome. People often can’t tell the difference between each type without looking at the chromosomes because the physical features and behaviors are similar.

- Trisomy 21: About 95% of people with Down syndrome have Trisomy 21. 2 With this type of Down syndrome, each cell in the body has 3 separate copies of chromosome 21 instead of the usual 2 copies.

- Translocation Down syndrome: This type accounts for a small percentage of people with Down syndrome (about 3%). 2 This occurs when an extra part or a whole extra chromosome 21 is present, but it is attached or “trans-located” to a different chromosome rather than being a separate chromosome 21.

- Mosaic Down syndrome: This type affects about 2% of the people with Down syndrome. 2 Mosaic means mixture or combination. For children with mosaic Down syndrome, some of their cells have 3 copies of chromosome 21, but other cells have the typical two copies of chromosome 21. Children with mosaic Down syndrome may have the same features as other children with Down syndrome. However, they may have fewer features of the condition due to the presence of some (or many) cells with a typical number of chromosomes.

Causes and Risk Factors

- The extra chromosome 21 leads to the physical features and developmental challenges that can occur among people with Down syndrome. Researchers know that Down syndrome is caused by an extra chromosome, but no one knows for sure why Down syndrome occurs or how many different factors play a role.

- One factor that increases the risk for having a baby with Down syndrome is the mother’s age. Women who are 35 years or older when they become pregnant are more likely to have a pregnancy affected by Down syndrome than women who become pregnant at a younger age. 3-5 However, the majority of babies with Down syndrome are born to mothers less than 35 years old, because there are many more births among younger women. 6,7

There are two basic types of tests available to detect Down syndrome during pregnancy: screening tests and diagnostic tests. A screening test can tell a woman and her healthcare provider whether her pregnancy has a lower or higher chance of having Down syndrome. Screening tests do not provide an absolute diagnosis, but they are safer for the mother and the developing baby. Diagnostic tests can typically detect whether or not a baby will have Down syndrome, but they can be more risky for the mother and developing baby. Neither screening nor diagnostic tests can predict the full impact of Down syndrome on a baby; no one can predict this.

Screening Tests

Screening tests often include a combination of a blood test, which measures the amount of various substances in the mother’s blood (e.g., MS-AFP, Triple Screen, Quad-screen), and an ultrasound, which creates a picture of the baby. During an ultrasound, one of the things the technician looks at is the fluid behind the baby’s neck. Extra fluid in this region could indicate a genetic problem. These screening tests can help determine the baby’s risk of Down syndrome. Rarely, screening tests can give an abnormal result even when there is nothing wrong with the baby. Sometimes, the test results are normal and yet they miss a problem that does exist.

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic tests are usually performed after a positive screening test in order to confirm a Down syndrome diagnosis. Types of diagnostic tests include:

- Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)—examines material from the placenta

- Amniocentesis—examines the amniotic fluid (the fluid from the sac surrounding the baby)

- Percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS)—examines blood from the umbilical cord

These tests look for changes in the chromosomes that would indicate a Down syndrome diagnosis.

Other Health Problems

Many people with Down syndrome have the common facial features and no other major birth defects. However, some people with Down syndrome might have one or more major birth defects or other medical problems. Some of the more common health problems among children with Down syndrome are listed below. 8

- Hearing loss

- Obstructive sleep apnea, which is a condition where the person’s breathing temporarily stops while asleep

- Ear infections

- Eye diseases

- Heart defects present at birth

Health care providers routinely monitor children with Down syndrome for these conditions.

Down syndrome is a lifelong condition. Services early in life will often help babies and children with Down syndrome to improve their physical and intellectual abilities. Most of these services focus on helping children with Down syndrome develop to their full potential. These services include speech, occupational, and physical therapy, and they are typically offered through early intervention programs in each state. Children with Down syndrome may also need extra help or attention in school, although many children are included in regular classes.

Other Resources

The views of these organizations are their own and do not reflect the official position of CDC.

- Down Syndrome Research Foundation (DSRF) DSRF initiates research studies to better understand the learning styles of those with Down syndrome.

- GiGi’s Playhouse GiGi’s Playhouse provides free educational, therapeutic-based, and career development programs for individuals with Down syndrome, their families, and the community, through a replicable playhouse model.

- Global Down Syndrome Foundation This foundation is dedicated to significantly improving the lives of people with Down syndrome through research, medical care, education and advocacy.

- National Association for Down Syndrome The National Association for Down Syndrome supports all persons with Down syndrome in achieving their full potential. They seek to help families, educate the public, address social issues and challenges, and facilitate active participation.

- National Down Syndrome Society (NDSS) NDSS seeks to increase awareness and acceptance of those with Down syndrome.

- Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, Meyer RE, Correa A, Alverson CJ, Lupo PJ, Riehle‐Colarusso T, Cho SJ, Aggarwal D, Kirby RS. National population‐based estimates for major birth defects, 2010–2014. Birth Defects Research. 2019; 111(18): 1420-1435.

- Shin M, Siffel C, Correa A. Survival of children with mosaic Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:800-1.

- Allen EG, Freeman SB, Druschel C, et al. Maternal age and risk for trisomy 21 assessed by the origin of chromosome nondisjunction: a report from the Atlanta and National Down Syndrome Projects. Hum Genet. 2009 Feb;125(1):41-52.

- Ghosh S, Feingold E, Dey SK. Etiology of Down syndrome: Evidence for consistent association among altered meiotic recombination, nondisjunction, and maternal age across populations. Am J Med Genet A. 2009 Jul;149A(7):1415-20.

- Sherman SL, Allen EG, Bean LH, Freeman SB. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(3):221-7.

- Adams MM, Erickson JD, Layde PM, Oakley GP. Down’s syndrome. Recent trends in the United States. JAMA. 1981 Aug 14;246(7):758-60.

- Olsen CL, Cross PK, Gensburg LJ, Hughes JP. The effects of prenatal diagnosis, population ageing, and changing fertility rates on the live birth prevalence of Down syndrome in New York State, 1983-1992. Prenat Diagn. 1996 Nov;16(11):991-1002.

- Bull MJ, the Committee on Genetics. Health supervision for children with Down syndrome. Pediatrics. 2011;128:393-406.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Mol Cell Med

- v.5(3); Summer 2016

Down Syndrome: Current Status, Challenges and Future Perspectives

Mohammad kazemi.

1 Department of Genetics and Molecular Biology, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

2 Medical Genetic Center of Genome, Isfahan, Iran.

3 Pediatric Inherited Diseases Research Center, Research Institute for Primordial Prevention of Non-communicable Disease, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Mansoor Salehi

Majid kheirollahi.

Down syndrome (DS) is a birth defect with huge medical and social costs, caused by trisomy of whole or part of chromosome 21. It is the most prevalent genetic disease worldwide and the common genetic cause of intellectual disabilities appearing in about 1 in 400-1500 newborns. Although the syndrome had been described thousands of years before, it was named after John Langdon Down who described its clinical description in 1866. Scientists have identified candidate genes that are involved in the formation of specific DS features. These advances in turn may help to develop targeted therapy for persons with trisomy 21. Screening for DS is an important part of routine prenatal care. Until recently, noninvasive screening for aneuploidy depends on the measurement of maternal serum analytes and ultrasonography. More recent progress has resulted in the development of noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS) test using cell-free fetal DNA sequences isolated from a maternal blood sample. A review on those achievements is discussed.

Down syndrome (DS) is the most frequently occurring chromosomal abnormality in humans and affecting between 1 in 400-1500 babies born in different populations, depending on maternal age, and prenatal screening schedules ( 1 - 6 ). DS is the common genetic cause of intellectual disabilities worldwide and large numbers of patients throughout the world encounter various additional health issues, including heart defects, hematopoietic disorders and early-onset Alzheimer disease ( 7 - 9 ). The syndrome is due to trisomy of the whole or part of chromosome 21 in all or some cells of the body and the subsequent increase in expression due to gene dosage of the trisomic genes ( 10 ). It is coupled with mental retardation, congenital heart defects, gastrointestinal anomalies, weak neuromuscular tone, dysmorphic features of the head, neck and airways, audiovestibular and visual impairment, characteristic facial and physical features, hematopoietic disorders and a higher incidence of other medical disorders. The incidence of births of children with DS increases with the age of the mother. However, due to higher fertility rates in younger women, the probability of having a child with DS increases with the age of the mother and more than 80% of children with DS are born to women under 35 years of age ( 7 , 11 ).

Historical background

Approximately 2500 years ago, Bernal and Briceno thought that certain sculptures represented individuals with trisomy 21, making these potteries the first empirical indication for the existence of the disease ( Figure 1 ). Martinez-Frias identified the syndrome in 500 patients with Alzheimer disease in which the facial features of trisomy 21 are clearly displayed. Different scientists described evident illustration of the syndrome in 15 th and 16 th century paintings. Esquirol wrote phenotypic description of trisomy 21 in 1838. English physician, John Langdon Down explained the phenotype of children with common features noticeable from other children with mental retardation. He referred them “Mongoloids” because these children looked like people from Mongolia ( 12 - 15 ).

Down syndrome statue representing individual with trisomy 21 related to almost 2500 years ago (16)

This disease was named “Down Syndrome” in honor of John Langdon Down, the doctor who first recognized the syndrome in 1866 but until the middle of the 20 th century, the cause of DS remained unknown. The probability that trisomy 21 might be a result of a chromosomal abnormality was suggested in 1932 by Waardenburg and Davenport ( 12 , 17 ). A revolution finally took place in 1956, when Joe Hin Tjio and Albert Levan described a set of experimental situations that allowed them to precisely characterize the number of human chromosomes as 46. During the three years of the publication of this revolutionary work, Jerome Lejeune in France and Patricia Jacobs in the United States were able to identify an extra copy of chromosome 21 in karyotypes prepared from DS patients. Then, in the 1959, researchers finally determined that presence of an additional copy of chromosome 21 (referred to trisomy 21) is the cause of DS ( 1 , 18 ).

Genetic basis

Chromosome 21 is the smallest human autosome with 48 million nucleotides and depicts almost 1–1.5% of the human genome. The length of 21q is 33.5 Mb and 21 p is 5–15 Mb. More than 400 genes are estimated to be on chromosome 21 ( Table 1 ). Chromosome 21 has 40.06% repeat content comprising short interspersed repeatitive elements (SINEs), long interspersed repeatitive elements (LINEs), and long terminal repeats (LTRs) ( 3 , 11 , 19 ). The most acceptable theory for the pathogenesis of trisomy 21 is the gene-dosage hypothesis, which declares that all changes are due to the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21 ( 12 ). Although it is difficult to select candidate genes for these phenotypes, data from transgenic mice suggest that only some genes on chromosome 21 may be involved in the phenotypes of DS and some gene products may be more sensitive to gene dosage imbalance than others. These gene products include morphogens, cell adhesion molecules, components of multi-subunit proteins, ligands and their receptors, transcription regulators and transporters. A “critical region” within 21q22 was thought to be responsible for several DS phenotypes including craniofacial abnormalities, congenital heart defects, clinodactyly of the fifth finger, mental retardation and several other features ( 3 , 11 ).

Candidate dosage sensitive genes on chromosome 21causing DS phenotype ( 11 , 23 , 24 )

DS is usually caused by an error in cell division named "nondisjunction" that leads to an embryo with three copies of chromosome 21. This type of DS is called trisomy 21 and accepted to be the major cause of DS, accounting for about 95% of cases ( 20 , 21 ). Since the late 1950s, scientists have also determined that a smaller number of DS cases (nearly 3-4%) are caused by chromosomal translocations. Because the translocations responsible for DS can be inherited, this form of the disease is sometimes named as familial DS. In these cases, a segment of chromosome 21 is transferred to another chromosome, usually chromosome 14 or 15. When the translocated chromosome with the extra piece of chromosome 21 is inherited together with two common copies of chromosome 21, DS will occur. For couples who have had one child with DS due to translocation trisomy 21, there may be an increased likelihood of DS in future pregnancies. This is because one of the parents may be a balanced carrier of the translocation. The chance of passing the translocation depends on the sex of the parent who carries the rearranged chromosome 21. If the father is the carrier, the risk is around 3 percent, while with the mother as the carrier, the risk is about 12 percent. This difference is due to the fact that it seems to be a selection against chromosomal abnormalities in sperm production which means men would produce fewer sperm with the wrong amount of DNA. Translocation and gonadal mosaicism are types of DS known to have a hereditary component and one third of them (or 1% of all cases of DS) are hereditary ( 1 , 22 ). The third form of disease named mosaicism, is a rare form (less than 2% of cases) of DS. While similar to simple trisomy 21, the difference is that the third copy of chromosome 21 is present in some, but not all cells. This type of DS is caused by abnormal cell division after fertilization. In cellular mosaicism, the mixture can be seen in different cells of the similar type; while with mosaicism, one set of cells may have normal chromosomes and another type may have trisomy 21 ( 1 , 22 )

Screening methods

Screening for DS is an important part of routine prenatal care. The most common screening method contains the measurement of a combination of factors: advanced maternal age, multiple second trimester serum markers, and second trimester ultrasonography ( Table 2 ) ( 25 - 26 ).

Detection rates and false positive rates of different Down syndrome screening tests ( 43 , 44 )

DR: detection rate; FPR: false-positive rate; NT: nuchal translucency; PAPP-A: pregnancy-associated plasma protein- A; β-hCG: chorionic gonadotropin; AFP: alpha-fetoprotein

The first method available for aneuploidy screening was maternal age. Advanced maternal age predisposes to DS and other fetal chromosomal abnormalities based on nondisjunction. In fact, the advanced maternal age was defined as age 35 years or older at delivery, because her risk of having a fetus with aneuploidy was equivalent to or more than the estimated risk for pregnancy loss caused by an amniocentesis. The extra chromosome 21 is the result of nondisjunction throughout meiosis in the egg or the sperm (standard trisomy 21) in almost 95% of individuals ( 27 - 29 ).

Trisomy 21 is coupled with a propensity for brachycephaly, duodenal atresia, cardiac defects, mild ventriculomegaly, nasal hypoplasia, echogenic bowel, mild hydronephrosis, shortening of the femur and sandal gap and clinodactyly or middle phalanx hypoplasia of the fifth finger. The first reported marker associated with DS was the thickening of the neck area ( 30 , 31 ). 40-50 percent of affected fetuses have a thickened nuchal fold measuring ≥ 6 mm in the second-trimester ( 32 , 33 ). After using of screening by nuchal translucency (NT), about 83% of trisomy 21 pregnancies were identified in the first trimester. Later, it was revealed that screening by a combination of maternal age, NT and bi-test [pregnancy-associated plasma protein (PAPP-A) with second trimester free β chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG)] or tri-test [alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), estriol and free β-hCG] has a potential sensitivity of 94% for a 5% false-positive rate ( 34 - 36 ).

NT is a physiological process ‘marker’ in the fetus that reflects the fetal lymphatic and vascular development in the head and neck area. NT measurement was primarily used as a stand-alone test for aneuploidy screening. Later, maternal age was added, and finally, NT became part of a combined first trimester aneuploidy screening test (NT, maternal age and the maternal serum markers, PAPP-A and β-hCG) ( 35 ).

Pyelectasis which refers to a diameter of the renal pelvis measuring ≥ 4 mm, is another second trimester marker; in fact, renal dilatation has a higher occurrence among fetuses with DS. However, pyelectasis remains a minor marker as the sensitivity is about 17%-25%, with a false-positive rate of 2%-3% ( 37 ).

Another important soft marker that has been effectively combined into fetal abnormality screening is the nasal bone. The absence of nasal bone in fetus at the 11-14 weeks scan is related to DS. This marker, initially, was found in 73% of trisomy 21 fetuses and in only 0.5% of chromosomally normal fetuses ( 38 , 39 ) and, subsequently, it was estimated that the combination of maternal age, NT, maternal serum biochemical screening (by bi- test or tri- test) and examination of nasal bone could increase the detection rate to 97% ( 40 ). After the completion of further confirmation studies, it is generally accepted that fetal nasal bone is a worthy sonographic marker, even if there are racial differences in the length of this bone ( 41 - 42 ).

Noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS)

One of the major innovations in obstetrical care was the introduction of prenatal genetic diagnosis, primarily by amniocentesis in the second trimester of pregnancy. Later, chorionic villus sampling during the first trimester allowed for earlier diagnosis. However, the potential risk of fetal loss due to an invasive procedure has urged the search for noninvasive approaches for genetic screening and diagnosis ( 45 ). More recent advances in genomics and related technologies have resulted in the development of a noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS) test using cell-free fetal DNA sequences isolated from a maternal blood sample. Almost 4-10% of DNA in maternal serum is of fetal origin. Fetal trisomy detection by cfDNA from maternal blood has been done using massively parallel shotgun sequencing (MPSS). By next generation sequencing platforms, millions of amplified genetic fragments can be sequenced in parallel. MPSS detects higher relative amounts of DNA in maternal plasma from the fetal trisomic chromosome compared with reference chromo-somes. Platforms differ according to whether amplified regions throughout the genome, chromosome-specific regions, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the targets for sequencing ( 1 , 45 , 46 ).

Another approach named digital analysis of selected regions (DANSR) selectively sequences loci only from target chromosomes by including a targeted amplification step. This method represents a considerable increase in sequencing efficiency. Recently, a new method has described selectively the sequences SNPs and ascertain copy number by comparing fetal to maternal SNP ratios between target and reference chromosomes. The use of SNPs may alleviate chromosome- to -chromosome amplification variability; however, the need for a reference chromosome partly negates this advantage ( 47 - 50 ).

Although studies are hopeful and exhibit high sensitivity and specificity with low false- positive rates, there are drawbacks to NIPS. Specificity and sensitivity are not consistent for all chromosomes; this is due to different content of cytosine and guanine nucleotide pairs. False- positive screening results take place and because the sequences derived from NIPS are derived from the placenta, like in chorionic villus sampling (CVS), they may not reflect the true fetal karyotype. Therefore, currently invasive testing is recommended for confirmation of a positive screening test and should remain an option for patients seeking a definitive diagnosis ( 35 , 45 , 51 ).

NIPS for fetal aneuploidy was presented into clinical practice in November 2011. Obstetricians have rapidly accepted this testing, and patients have welcomed this option due to its lack of fetal morbidity and mortality ( 52 ). At first, NIPS began as a screen for only trisomy 21 (T21) and was rapidly developed to include other common aneuploidies for chromosomes 13 (T13), 18 (T18), X, and Y ( 53 ).

Notwithstanding improvement in sensitivity, approaches using cfDNA are not diagnostic tests as false positive and false negative results are still generated, although at very low rates than the previous maternal screening tests. A significant source of a discrepant result comes from the fact that the fetal fraction of cfDNA originates pre-dominantly from apoptosis of the trophoblast layer of the chorionic villi and not the fetus. Thus, inva-sive diagnostic testing such as CVS or amnio-centesis, is recommended after a positive cfDNA fetal aneuploidy screening test. Because cfDNA testing is normally presented in the first trimester, CVS is often the choice invasive method applied. If mosaicism is recognized on CVS, confirmatory amniocentesis is recommended ( 54 - 56 ).

Although NIPS is not a diagnostic test, it offers a considerably developed screen for fetal aneuploidy compared to the earlier screening tests that depend on maternal serum markers ( Table3 ). Patients with positive screen results should take suitable genetic counseling to persuade that follow-up testing is necessary before making a decision as to whether or not to continue a pregnancy because of concern over a positive NIPS result. However, patients with negative test results need to know that there is still a chance that their fetus may have a chromosome abnormality due to a false negative result ( 52 ).

Detection rates and false positive rates of major aneuploidies using NIPT ( 51 , 57 , 58 )

CI: confidence interval.

Diagnostic methods

Amniocentesis is the most conventional invasive prenatal diagnostic method accepted in the world. Amniocenteses are mostly performed to acquire amniotic fluid for karyotyping from 15 weeks onwards. Amniocentesis performed before 15 weeks of pregnancy is referred to as early amniocentesis. CVS is usually performed between 11 and 13 (13+6) weeks of gestation and includes aspiration or biopsy of placental villi. Amniocentesis and CVS are quite reliable but increase the risk of miscarriage up to 0.5 to 1% compared with the background risk ( 59 - 60 ).

There is no medical cure for DS. However, children with DS would benefit from early medical support and developmental interventions initiation during childhood. Children with DS may benefit from speech therapy, physical therapy and work-related therapy. They may receive special education and assistance in school. Life expectancy for people with DS has improved noticeably in recent decades ( 61 ). Nowadays, cardiac surgery, vaccinations, antibiotics, thyroid hormones, leukemia therapies, and anticonvulsive drugs (e.g, vigabatrin) have significantly improved the quality of life of individuals with DS. Actually, life expectancy that was hardly 30 years in the 1960s is now increasing more than 60 years of age ( 3 , 62 - 63 ).

X inactivation is the mammalian dosage compensation mechanism that ensures that all cells in males and females have one active X chromoso-me (Xa) for a diploid set of autosomes. This is achieved by silencing one of the two X chromoso-mes in female cells. The X chromosome silencing is effected by Xist non-coding RNA and is associated with chromatin modification ( 64 ). Recently, resear-chers have applied this model of transcriptional silencing to the problem of additional gene expre-ssion in DS. In induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells derived from a patient with DS, the researchers used zinc-finger nucleases to insert inducible X inactive specific transcript (non–protein-encoding) (XIST) into chromosome 21. The mechanism of transcriptional silencing due to the Xist transgene appears to involve covering chromosome 21 with Xist RNA that results in stable modification of heterochromatin. In the iPS cells, induction of the newly inserted transgene resulted in expression of XIST noncoding RNA that coated chromosome 21 and triggered chromosome inactivation ( 65 - 66 ).

In summary, DS is a birth defect with huge medical and social costs and at this time there is no medical cure for DS. So, it is necessary to screen all pregnant women for DS. NIPS for fetal aneuploidy which was presented into clinical practice since November 2011 has not been yet considered as diagnostic test as false positive and false negative test results are still generated. Thus, invasive diagnostic testing such as CVS or amniocentesis, is recommended after a positive cfDNA fetal aneuploidy screening test.

The described performance of screening for trisomy 21 by the cffDNA test, with a diagnostic rate of more than 99% and false positive rate less than 0.1%, is preferable to other screening methods. Despite the test is obtaining common acceptability, the high cost restricts its application to all patients, identified as such by another traditional first-line method of screening. In the screening with cffDNA testing, the nuchal scan is considered to be the most appropriate first-line method of screening.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Other Diseases & Conditions — Down Syndrome

Essay Examples on Down Syndrome

Down syndrome essay topics and outline examples, essay title 1: embracing diversity: understanding down syndrome, its causes, and challenges.

Thesis Statement: This essay aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of Down syndrome, including its genetic causes, associated health challenges, and the importance of inclusion and support for individuals with Down syndrome.

- Introduction

- Defining Down Syndrome: An Overview of Trisomy 21

- Genetic Causes: Understanding the Extra Chromosome 21

- Health Challenges: Physical and Intellectual Characteristics of Down Syndrome

- Early Intervention and Education: Strategies for Optimal Development

- Inclusive Society: The Importance of Acceptance and Equal Opportunities

- Supportive Networks: Families, Advocacy Groups, and Healthcare

- Conclusion: Celebrating the Abilities and Contributions of Individuals with Down Syndrome

Essay Title 2: Breaking Stereotypes: Achievements, Success Stories, and Opportunities for People with Down Syndrome

Thesis Statement: This essay explores the accomplishments and potential of individuals with Down syndrome, highlighting success stories, educational achievements, and the broader societal impact of challenging stereotypes.

- Historical Perspectives: Changing Attitudes Towards Down Syndrome

- Education and Employment: Navigating Opportunities and Challenges

- Success Stories: Remarkable Achievements of Individuals with Down Syndrome

- Fostering Independence: Life Skills and Empowerment Programs

- Family Perspectives: The Role of Supportive Parents and Siblings

- Changing Perceptions: The Impact of Advocacy and Awareness Campaigns

- Conclusion: Redefining What's Possible for People with Down Syndrome

Essay Title 3: Advances in Down Syndrome Research: Genetics, Therapies, and Future Prospects

Thesis Statement: This essay delves into the realm of Down syndrome research, highlighting recent developments in genetics, therapeutic approaches, and the potential future directions that hold promise for improving the quality of life for individuals with Down syndrome.

- Genetic Insights: Discoveries in Trisomy 21 Research

- Therapeutic Strategies: Speech, Occupational, and Physical Therapies

- Cognitive Development: Enhancing Learning and Communication

- Early Intervention: The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Support

- Future Directions: Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research Areas

- Global Collaboration: International Efforts to Improve Down Syndrome Care

- Conclusion: The Promising Path Towards Enhanced Quality of Life for Individuals with Down Syndrome

Down Syndrome: Causes, Symptoms, and Support

The causes and physical and mental effects of down syndrome, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Speech and Language Deficits of Children with Down Syndrome

Case study on corrective surgical procedure, paternal age: the considerable confounding risk factor in chromosomal aneuploidies, why cosmetic surgery is not an answer to down syndrome, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Relevant topics

- Atherosclerosis

- Sickle Cell Anemia

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What's it like to have Down Syndrome?

I Have Down Syndrome—Know Me Before You Judge Me

When I first started to work on this story, I thought maybe I shouldn’t do it. I thought you might see that I have Down syndrome, and that you wouldn’t like me.

My mom thinks that’s silly. “Have you ever met anyone who didn’t like you because you have Down syndrome?” she asks me. She’s right, of course. (She usually is!)

When people ask me what Down syndrome is, I tell them it’s an extra chromosome. A doctor would tell you the extra chromosome causes an intellectual disability that makes it harder for me to learn things. (For instance, some of my classes are in a “resource room,” where kids with many kinds of learning disabilities are taught at a different pace.)

When my mom first told me I had Down syndrome, I worried that people might think I wasn’t as smart as they were, or that I talked or looked different.

I just want to be like everyone else, so sometimes I wish I could give back the extra chromosome. But having Down syndrome is what makes me “me.” And I’m proud of who I am. I’m a hard worker, a good person, and I care about my friends.

Melissa Riggio shares her thoughts about Down syndrome.

A Lot Like You

Even though I have Down syndrome, my life is a lot like yours. I read books and watch TV. I listen to music with my friends. I’m on the swim team and in chorus at school. I think about the future, like who I’ll marry. And I get along with my sisters—except when they take my CDs without asking!

Some of my classes are with typical kids, and some are with kids with learning disabilities. I have an aide who goes with me to my harder classes, like math and biology. She helps me take notes and gives me tips on how I should study for tests. It really helps, but I also challenge myself to do well. For instance, my goal was to be in a typical English class by 12th grade. That’s exactly what happened this year!

But sometimes it’s hard being with typical kids. For instance, I don’t drive, but a lot of kids in my school do. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to, and that’s hard to accept.

Dream Job: Singer

I try not to let things like that upset me and just think of all the good things in my life. Like that I’ve published two songs. One of my favorite things to do is write poetry, and this singer my dad knows recorded some of my poems as singles.

Right now someone else is singing my songs, but someday, I want to be the one singing. I know it’s going to happen, because I’ve seen it. One day I looked in the mirror, and I saw someone in my head, a famous person or someone who was somebody, and I just knew: I will be a singer.

It’s true that I don’t learn some things as fast as other people. But that won’t stop me from trying. I just know that if I work really hard and be myself, I can do almost anything.

But I still have to remind myself all the time that it really is OK to just be myself. Sometimes all I see—all I think other people see—is the outside of me, not the inside. And I really want people to go in there and see what I’m all about.

Maybe that’s why I write poetry—so people can find out who I really am. My poems are all about my feelings: when I hope, when I hurt. I’m not sure where the ideas come from—I just look them up in my head. It’s like I have this gut feeling that comes out of me and onto the paper.

I can’t change that I have Down syndrome, but one thing I would change is how people think of me. I’d tell them: Judge me as a whole person, not just the person you see. Treat me with respect, and accept me for who I am. Most important, just be my friend.

After all, I would do the same for you.

Bonding over cookies!

My sisters are always there for me, even when just having fun.

My sisters, Christina (left) and Laura, are two of the most important people in my life.

Horseback riding helps relax me.

What Is Down Syndrome?

Down syndrome is an intellectual disability that about 5,000 babies in the United States are born with each year. A person with Down syndrome has 47 chromosomes, microscopic structures that carry genetic information to determine almost everything about a person. Most people have only 46 chromosomes. It’s the extra chromosome that can cause certain physical characteristics (such as short stature and an upward slant to the eyes) and speech and developmental delays. Still, people with Down syndrome are a lot like you: They are unique people with strengths and talents.

By Melissa Riggio, as told to Rachel Buchholz

Photographs by Annie Griffiths Belt

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

An Overview of Down syndrome

What is Down syndrome? What causes Down syndrome? How is Down syndrome diagnosed? We cover your questions and more in this overview!

As I entered the hospital, my chest tightened. I marched down the long white hallway, flanked on either side by my grandparents and two younger sisters, and braced myself for what was ahead. My eyes were puffy, but I was determined that I was not going to cry again. Instead, I plastered a smile on my face and entered the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), ready to meet my baby brother.

Immediately following his birth, Benjamin had been transferred to the NICU. Instead of the anticipated joy and excitement, his birth had brought me and my family worry and confusion. That week, I saw my dad cry for the first time. I did not see my mom at all. I was desperate to know what was going on and I hungrily latched onto whatever information my grandparents could tell me, which was not much. Slowly, I pieced what I could together. I learned that Benjamin had a hole in his heart and that he needed surgery. I learned that he could not breathe on his own and that he needed an oxygen tank to perform even this most basic function. Finally, I learned that Benjamin had Down syndrome.

When my grandma told me this, I sprinted up the stairs and into my room. I then collapsed onto my bedroom floor and, surrounded by piles of laundry, broke down in tears. I had no idea what Down syndrome was, but it didn’t sound good. And if this week was any indication, it was bad. It sounded painful and hard. I thought that it meant my baby brother wasn’t normal.

My reaction to my brother’s diagnosis, which could be dismissed as an overblown response from a fifth grade drama queen, is, in fact, not uncommon. In a study examining the social stigma surrounding Down syndrome, Dr. Renu Jain, from the Department of Pediatrics and Medical Humanities at the Loyola University Medical Center, found feelings of anger and grief to be very common among families who have just learned their infant has Down syndrome. In fact, Dr. Jain found that “upon the diagnosis of a [Down syndrome] fetus or infant, the parents go through a mourning process no less severe than the mourning of a death of an infant” (Jain). Parents who find out the diagnosis of Down syndrome before birth, through prenatal testing, terminate the pregnancy at a rate of 92%, an exceptionally high rate that is significantly higher than if the parents had learned of a physical disability (Lawson). These findings point to a very bleak view of the life of a person with Down syndrome. They suggest that the diagnosis of Down syndrome is comparable to death, that an individual with Down syndrome cannot live a good life, that this individual is inherently less than another without the same disability.

In a stark contrast to these views, a survey conducted by Dr. Brian G. Sokto, a doctor in the Division of Genetics at the Children’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, found that individuals with Down syndrome report that “they are living happy and fulfilling lives” (Skotko). In a similar study, Melissa Scott, a researcher in the School of Exercise and Health Sciences at the Edith Cowan University, found that individuals with Down syndrome have a positive perspective on life and hold the general consensus “I have a good life” (Scott). They have desires similar to their peers, “including the rights to the same life opportunities” (Scott). They “like who they are and how they look” (Skotko). They love their families. This data points to a very different view of life than suggested earlier. What is the reason for this contradiction? If individuals with Down syndrome say that they have good lives, why are their voices not heard? Why is there such a strong prevailing social stigma against them?

Many researchers in this field suggest that this strong social stigma is, in part, a result of the lack of public knowledge and awareness of Down syndrome. Many people have never met or interacted with an individual with Down syndrome. Some do not know what Down syndrome is. Before my brother was born, I did not either.

Down syndrome is “a genetic disorder caused when abnormal cell division results in an extra full or partial copy of chromosome 21” (Mayo Clinic). The average human has 46 chromosomes, while those with Down syndrome have 47. This extra chromosome can cause both developmental and physical changes. In the United States, the Center for Disease Control estimates that there are 6,000 children born with Down Syndrome each year, making it the most commonly occurring chromosomal disability and learning disability.

While all individuals with Down syndrome have an extra chromosome 21 and share many of the same physical characteristics, Down syndrome does not affect all individuals in the same way. As the Mayo Clinic states, “Each person with Down syndrome is an individual — intellectual and developmental problems may be mild, moderate or severe” (Mayo Clinic). Down syndrome does not mean the same thing for every person.

In fact, many of the qualities previously associated with Down syndrome are no longer connected to the disability. In recent years, many of the perceived attributes of Down syndrome were found to be situational, rather than a result of the disability itself. As recently as 1980, the life expectancy for a person with Down syndrome was just 28 years (Global Down Syndrome Foundation). At this time, many individuals with Down syndrome were institutionalized and denied access to proper medical care and education. This institutionalization put individuals in an environment that facilitated “the rapid spread of infections between patients” (Bittles). Thus, poor health came hand in hand with Down syndrome, but sometimes as a result of the environment individuals were in, or their lack of access to even basic medical care.

Today, those with Down syndrome are not forcibly institutionalized. The life expectancy of an individual with Down syndrome is 60 years old, with some people living to their 80s and 90s. The medical community has made huge strides in addressing and treating some of the more negative effects of Down syndrome. There are now integrated school programs in which individuals with Down syndrome are able to attend school and learn alongside other children their age. There are better resources in place, especially for young children, to ensure they are cared for and stimulated in their early years (Jain). Maternal and familial support groups can be found in almost every area of the country, offering a fountain of encouragement, support, and advice for new families. In the United States, there are governmental financial entitlements available to families with a member who has Down syndrome. The diagnosis of Down syndrome is no longer a sentence to a short life with many barriers to success.

When my brother was born, I was unaware of all of this. All that was staring me in the face was the inside of the NICU. All I could hear was the puffing of the oxygen tank Benjamin had to be connected to at all times. My family, however, was surrounded by support. The doctors and nurses at the hospital were unwavering in their care and encouragement. Families who had children with Down syndrome reached out to us and shared their stories. This network of people assured us that everything was going to be more than okay, that it was going to be good.

The support we received, however, has not been found to be a shared experience. Families with members who have Down syndrome “have consistently reported that the initial information received from their healthcare providers was often inaccurate, incomplete, or offensive'' (Sokto). In medical literature, professionals tend “to present negative reports of Down syndrome” (Alderson). While these attitudes are not common to all medical professionals, those that do exist can spread misinformation and further stigmatize the disability.

Dr. Jain argues that “it is time for professionals to move from the medical to the psycho-educational field” (Jain). He says that “health professionals have the responsibility to help make public attitudes more accepting of [Down syndrome]” (Jain). If doctors are to do so, they must start with their own perceptions of Down syndrome first. A diagnosis of Down syndrome does not have to be something that is mourned. As seen in the move from institutionalization in the 1980s to today, the assistance of medical professionals has been crucial in improving the quality of life of those with Down syndrome. A shift in medical attitude can make a world of difference in countless lives. One key way this shift can occur, which is surprisingly lacking in both the medical field and wider literature, is hearing from the voices of people with Down syndrome themselves.

On finding out that a child has Down syndrome, questions that first come are ones such as, “What does it mean to have [Down syndrome]? Will my baby with [Down syndrome] be happy? Will my baby have a good life?” (Skotko). These are questions that can be best answered by individuals with Down syndrome themselves. And, as noted earlier, the response is a resounding “Yes.” Yes, they can be happy. Yes, they can have a good life.

In a moving speech to the United States Senate on Capitol Hill, Frank Stephens, a man with Down syndrome, petitioned for more research concerning Down syndrome. This speech came in response to the recent shift away from research into Down syndrome and advancements that can improve them, to research in how to detect and prevent Down syndrome, primarily through termination. Stephens addressed the Senate saying, “I am a man with Down Syndrome and my life is worth living.” He went on to say that not only was his life worth living, but that “we are an unusually powerful source of happiness: a Harvard-based study has discovered that people with Down Syndrome, as well as their parents and siblings, are happier than society at large. Surely happiness is worth something?” He asked the Senate for “answers, not ‘final solutions.’”

Stephens’s words mirrored those of other individuals with Down syndrome and their families on their happiness. In Skotko’s study, when individuals were asked, “What would you like to tell doctors about your life with Down syndrome?”, the top two responses were “Life is good/I’m happy to be alive/positive” and “Please take care of our medical needs.” These two appeals cut to the heart of the matter. Down syndrome is not a death sentence. Those with Down syndrome can live a happy and fulfilling life; their disability does not undercut this. Their medical needs should have as much of a voice as anyone else’s. They, too, deserve supportive doctors who want to help. They deserve doctors who do not see their lives as less. This recognition is the start of changing the social stigma against Down syndrome.

Another frequent response to Skotko’s survey was the simple statement that “It’s okay to have special needs.” These individuals who responded embraced what society as a whole has yet been unable to, the message that it’s okay to be different. As Rhonda Faragher, a professor at the School of Education at The University of Queensland puts it, “Those of us in the disability sector...have learned to value human diversity.” Different doesn't mean unhappy. Different doesn't mean better off dead.

Many of those with Down syndrome do not factor ability into their happiness. Skotko found in his study that different functional abilities in fact had no bearing on self-esteem and reported happiness. In her study, Scott found that in their descriptions of their lives, not one of the individuals mentioned “impairments of body functions and structures.” Instead, in both groups, individuals pointed to struggles and hopes very similar to those of their peers. Some of these included the desire for independence, a relationship, and education.

In interviews with parents, researchers have found that their perceptions of their child with Down syndrome change over time as well. By spending time with the child and interacting, many parents found their initial perception to change completely. Lawson and Walls-Ingram, two researchers at the University of Saskatchewan, conducted a study in which they found that “personal contact with individuals with [Down syndrome] was associated with more favorable attitudes toward [Down syndrome].” The more time and awareness that is devoted towards looking at people with Down syndrome as just that, people, not as problems, can disprove many of the stereotypes and misconceptions surrounding the disability.

In one month, Benjamin will turn eight years old. He is enrolled in a nearby public school’s special ed program and is close to completing second grade. He loves swimming, drawing, and Taylor Swift. He is also one of the happiest kids I know. His birth did change my life, but not in the ways that I thought it would. For me, Benjamin has been a constant source of joy and love.

This is not to say that Benjamin has not presented a set of difficulties; he has, just like all my other siblings. His are of a different variety and are sometimes more extreme. Through all of this, however, I have never questioned if his life is worth living, worth as much as mine, or if he is happy. The answers to these questions are all the same. Yes, of course. If I could tell my fifth grade self anything, it would be that Benjamin is an unbelievable gift, from top to bottom. There is no need for worry or fear.

Works Cited

Alderson, Priscilla. “Down's Syndrome: Cost, Quality and Value of Life.” Social Science & Medicine , vol. 53, no. 5, Elsevier Ltd, 2001, pp. 627–38, doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00365-8.

Bittles, Ah, and Ej Glasson. “Clinical, Social, and Ethical Implications of Changing Life Expectancy in Down Syndrome.” Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology , vol. 46, no. 04, 2004, doi:10.1017/s0012162204000441.

“Down Syndrome.” Mayo Clinic , Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 8 Mar. 2018, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/down-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20355977.

Faragher, Rhonda. “Research in the Field of Down Syndrome: Impact, Continuing Need, and Possible Risks from the New Eugenics.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities , vol. 16, no. 2, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2019, pp. 130–33, doi:10.1111/jppi.12305.

Friedersdorf, Conor. “'I Am a Man With Down Syndrome and My Life Is Worth Living'.” The Atlantic , Atlantic Media Company, 31 Oct. 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/po...

Jain, Renu C., et al. “Down Syndrome: Still a Social Stigma.” American Journal of Perinatology , vol. 19, no. 2, Copyright © 2002 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001, USA. Tel.: +1(212) 584-4662, 2002, pp. 099–108, doi:10.1055/s-2002-23553.

Scott, Melissa, et al. “"I Have a Good Life": The Meaning of Well-Being from the Perspective of Young Adults with Down Syndrome.” Disability and Rehabilitation , vol. 36, no. 15, Taylor & Francis, 2014, pp. 1290–98, doi:10.3109/09638288.2013.854843.

Skotko, Brian G., et al. “Self-Perceptions from People with Down Syndrome.” American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A , vol. 155, no. 10, 2011, pp. 2360–69, doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.34235.

“What Is Down Syndrome?: National Down Syndrome Society.” NDSS , National Down Syndrome Society, www.ndss.org/about-down-syndrome/down-syndrome/.

Take a look at the fourth paragraph. How does Barrett transition from her personal narrative to an academic source?