Psychological Research Methods: Types and Tips

Categories Research Methods

Psychological research methods are the techniques used by scientists and researchers to study human behavior and mental processes. These methods are used to gather empirical evidence.

The goal of psychological research methods is to obtain objective and verifiable data collected through scientific experimentation and observation.

The research methods that are used in psychology are crucial for understanding how and why people behave the way they do, as well as for developing and testing theories about human behavior.

Table of Contents

Reasons to Learn More About Psychological Research Methods

One of the key goals of psychological research is to make sure that the data collected is reliable and valid.

- Reliability means that the data is consistent and can be replicated

- Validity refers to the accuracy of the data collected

Researchers must take great care to ensure that their research methods are reliable and valid, as this is essential for drawing accurate conclusions and making valid claims about human behavior.

High school and college students who are interested in psychology can benefit greatly from learning about research methods. Understanding how psychologists study human behavior and mental processes can help students develop critical thinking skills and a deeper appreciation for the complexity of human behavior.

Having an understanding of these research methods can prepare students for future coursework in psychology, as well as for potential careers in the field.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Psychological Research Methods

Psychological research methods can be broadly divided into two main types: quantitative and qualitative. These two methods differ in their approach to data collection and analysis.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative research methods involve collecting numerical data through controlled experiments, surveys, and other objective measures.

The goal of quantitative research is to identify patterns and relationships in the data that can be analyzed statistically.

Researchers use statistical methods to test hypotheses, identify significant differences between groups, and make predictions about future behavior.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods, on the other hand, involve collecting non-numerical data through open-ended interviews, observations, and other subjective measures.

Qualitative research aims to understand the subjective experiences and perspectives of individuals and groups.

Researchers use methods such as content analysis and thematic analysis to identify themes and patterns in the data and to develop rich descriptions of the phenomenon under study.

How Quantitative and Qualitative Methods Are Used

While quantitative and qualitative research methods differ in their approach to data collection and analysis, they are often used together to gain a more complete understanding of complex phenomena.

For example, a researcher studying the impact of social media on mental health might use a quantitative survey to gather numerical data on social media use and a qualitative interview to gain insight into participants’ subjective experiences with social media.

Types of Psychological Research Methods

There are several types of research methods used in psychology, including experiments, surveys, case studies, and observational studies. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses, and researchers must choose the most appropriate method based on their research question and the data they hope to collect.

Case Studies

A case study is a research method used in psychology to investigate an individual, group, or event in great detail. In a case study, the researcher gathers information from a variety of sources, including:

- Observation

- Document analysis

These methods allow researchers to gain an in-depth understanding of the case being studied.

Case studies are particularly useful when the phenomenon under investigation is rare or complex, and when it is difficult to replicate in a laboratory setting.

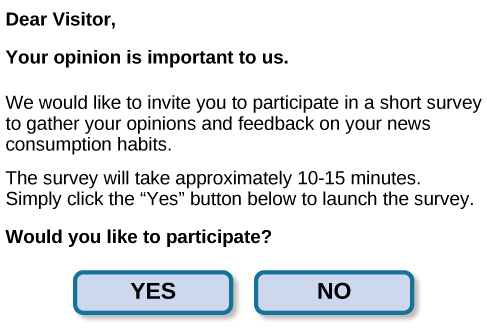

Surveys are a commonly used research method in psychology that involve gathering data from a large number of people about their thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and attitudes.

Surveys can be conducted in a variety of ways, including:

- In-person interviews

- Online questionnaires

- Paper-and-pencil surveys

Surveys are particularly useful when researchers want to study attitudes or behaviors that are difficult to observe directly or when they want to generalize their findings to a larger population.

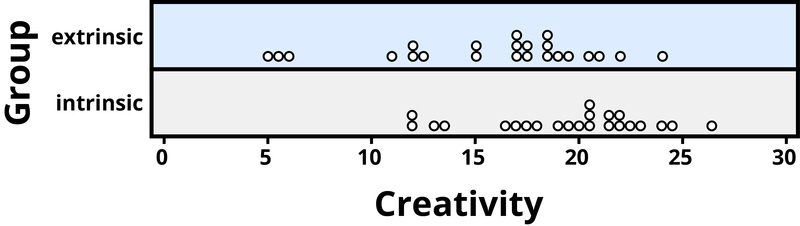

Experimental Psychological Research Methods

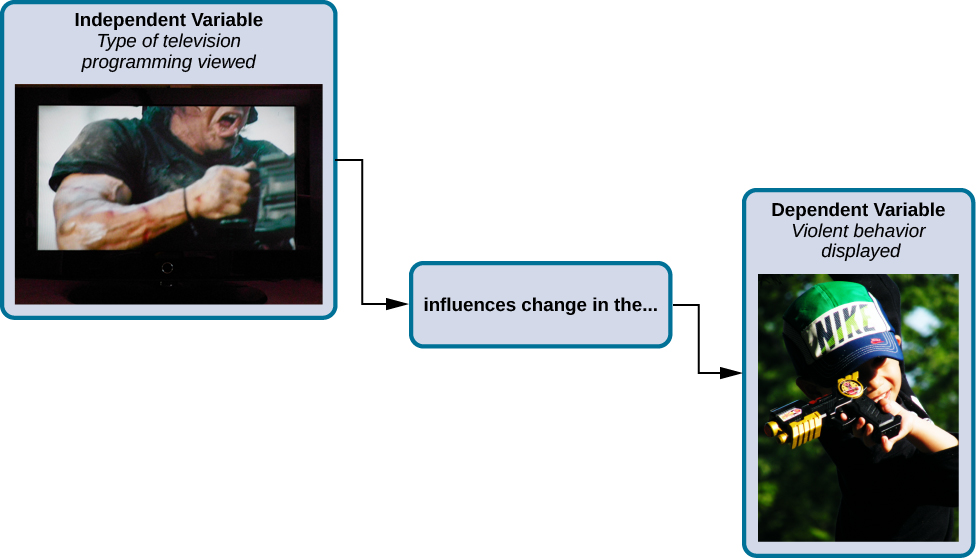

Experimental studies are a research method commonly used in psychology to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. In an experimental study, the researcher manipulates one or more variables to see how they affect another variable, while controlling for other factors that may influence the outcome.

Experimental studies are considered the gold standard for establishing cause-and-effect relationships, as they allow researchers to control for potential confounding variables and to manipulate variables in a systematic way.

Correlational Psychological Research Methods

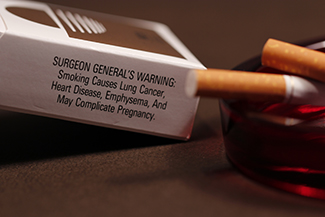

Correlational research is a research method used in psychology to investigate the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them. The goal of correlational research is to determine the extent to which changes in one variable are associated with changes in another variable.

In other words, correlational research aims to establish the direction and strength of the relationship between two or more variables.

Naturalistic Observation

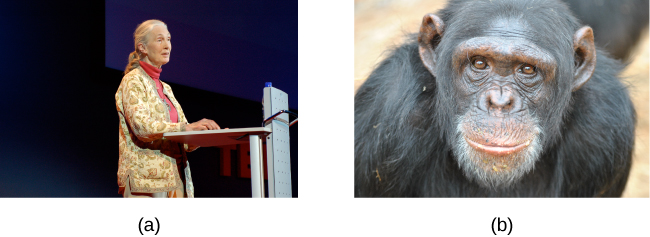

Naturalistic observation is a research method used in psychology to study behavior in natural settings, without any interference or manipulation from the researcher.

The goal of naturalistic observation is to gain insight into how people or animals behave in their natural environment without the influence of laboratory conditions.

Meta-Analysis

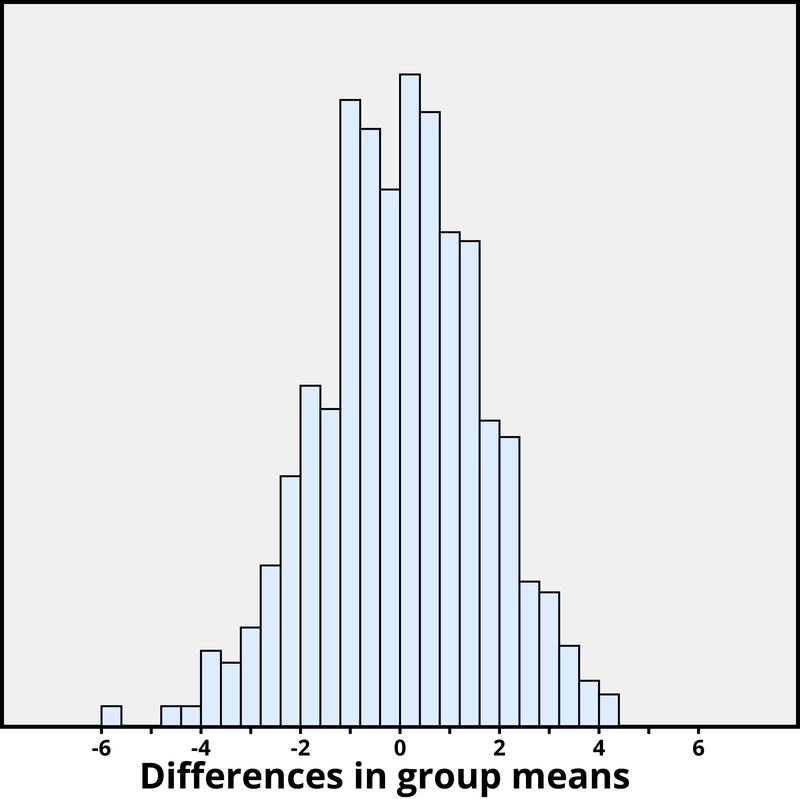

A meta-analysis is a research method commonly used in psychology to combine and analyze the results of multiple studies on a particular topic.

The goal of a meta-analysis is to provide a comprehensive and quantitative summary of the existing research on a topic, in order to identify patterns and relationships that may not be apparent in individual studies.

Tips for Using Psychological Research Methods

Here are some tips for high school and college students who are interested in using psychological research methods:

Understand the different types of research methods:

Before conducting any research, it is important to understand the different types of research methods that are available, such as surveys, case studies, experiments, and naturalistic observation.

Each method has its strengths and limitations, and selecting the appropriate method depends on the research question and variables being investigated.

Develop a clear research question:

A good research question is essential for guiding the research process. It should be specific, clear, and relevant to the field of psychology. It is also important to consider ethical considerations when developing a research question.

Use proper sampling techniques:

Sampling is the process of selecting participants for a study. It is important to use proper sampling techniques to ensure that the sample is representative of the population being studied.

Random sampling is considered the gold standard for sampling, but other techniques, such as convenience sampling, may also be used depending on the research question.

Use reliable and valid measures:

It is important to use reliable and valid measures to ensure the data collected is accurate and meaningful. This may involve using established measures or developing new measures and testing their reliability and validity.

Consider ethical issues:

It is important to consider ethical considerations when conducting psychological research, such as obtaining informed consent from participants, maintaining confidentiality, and minimizing any potential harm to participants.

In many cases, you will need to submit your study proposal to your school’s institutional review board for approval.

Analyze and interpret the data appropriately :

After collecting the data, it is important to analyze and interpret the data appropriately. This may involve using statistical techniques to identify patterns and relationships between variables, and using appropriate software tools for analysis.

Communicate findings clearly:

Finally, it is important to communicate the findings clearly in a way that is understandable to others. This may involve writing a research report, giving a presentation, or publishing a paper in a scholarly journal.

Clear communication is essential for advancing the field of psychology and informing future research.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 5 methods of psychological research.

The five main methods of psychological research are:

- Experimental research : This method involves manipulating one or more independent variables to observe their effect on one or more dependent variables while controlling for other variables. The goal is to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

- Correlational research : This method involves examining the relationship between two or more variables, without manipulating them. The goal is to determine whether there is a relationship between the variables and the strength and direction of that relationship.

- Survey research : This method involves gathering information from a sample of participants using questionnaires or interviews. The goal is to collect data on attitudes, opinions, behaviors, or other variables of interest.

- Case study research : This method involves an in-depth analysis of a single individual, group, or event. The goal is to gain insight into specific behaviors, attitudes, or phenomena.

- Naturalistic observation research : This method involves observing and recording behavior in natural settings without any manipulation or interference from the researcher. The goal is to gain insight into how people or animals behave in their natural environment.

What is the most commonly used psychological research method?

The most common research method used in psychology varies depending on the research question and the variables being investigated. However, correlational research is one of the most frequently used methods in psychology.

This is likely because correlational research is useful in studying a wide range of psychological phenomena, and it can be used to examine the relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled, such as age, gender, and personality traits.

Experimental research is also a widely used method in psychology, particularly in the areas of cognitive psychology , social psychology , and developmental psychology .

Other methods, such as survey research, case study research, and naturalistic observation, are also commonly used in psychology research, depending on the research question and the variables being studied.

How do you know which research method to use?

Deciding which type of research method to use depends on the research question, the variables being studied, and the practical considerations involved. Here are some general guidelines to help students decide which research method to use:

- Identify the research question : The first step is to clearly define the research question. What are you trying to study? What is the hypothesis you want to test? Answering these questions will help you determine which research method is best suited for your study.

- Choose your variables : Identify the independent and dependent variables involved in your research question. This will help you determine whether an experimental or correlational research method is most appropriate.

- Consider your resources : Think about the time, resources, and ethical considerations involved in conducting the research. For example, if you are working on a tight budget, a survey or correlational research method may be more feasible than an experimental study.

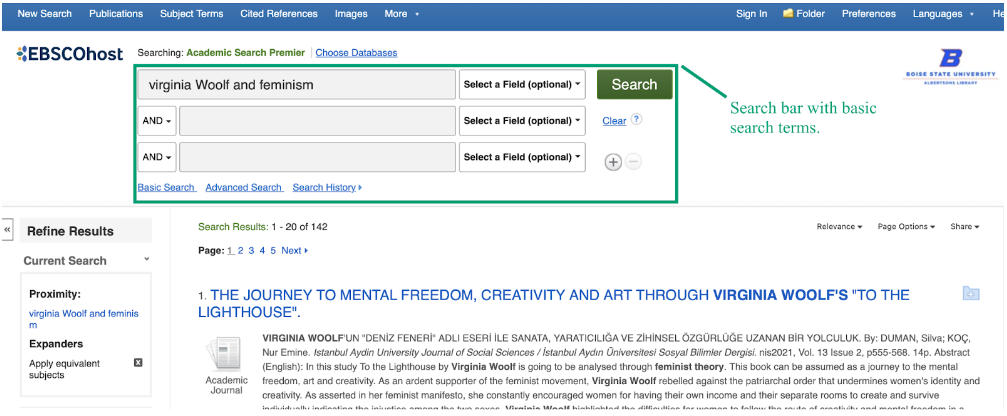

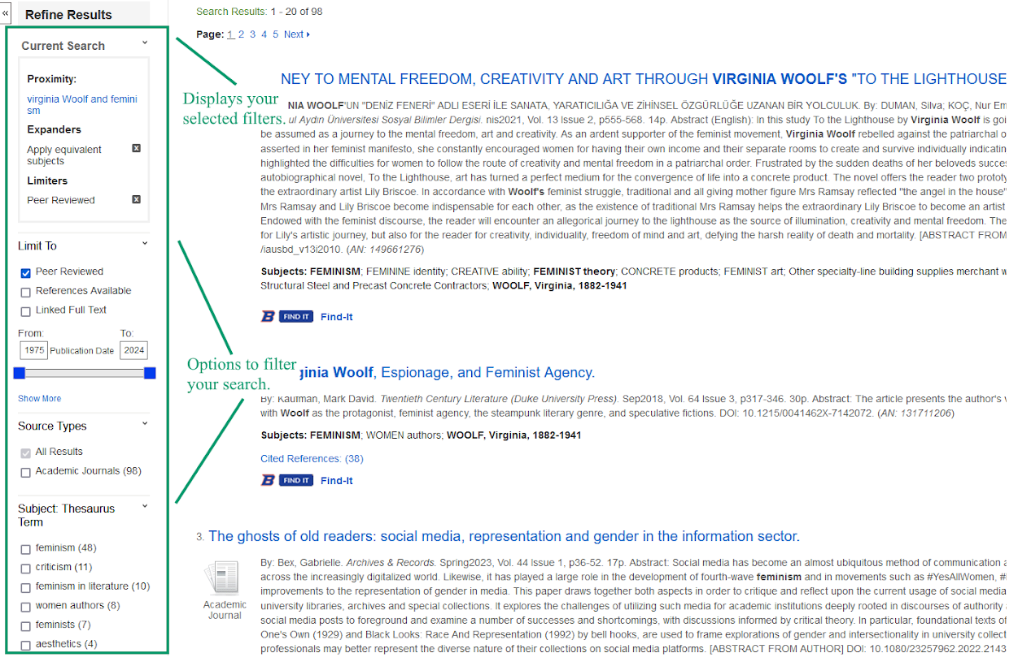

- Review existing literature : Conducting a literature review of previous studies on the topic can help you identify the most appropriate research method. This can also help you identify gaps in the literature that your study can fill.

- Consult with a mentor or advisor : If you are still unsure which research method to use, consult with a mentor or advisor who has experience in conducting research in your area of interest. They can provide guidance and help you make an informed decision.

Scholtz SE, de Klerk W, de Beer LT. The use of research methods in psychological research: A systematised review . Front Res Metr Anal . 2020;5:1. doi:10.3389/frma.2020.00001

Palinkas LA. Qualitative and mixed methods in mental health services and implementation research . J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol . 2014;43(6):851-861. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.910791

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11(1):100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Understanding Methods for Research in Psychology

A Psychology Research Methods Study Guide

Types of Research in Psychology

- Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal Research

- Reliability and Validity

Glossary of Terms

Research in psychology focuses on a variety of topics , ranging from the development of infants to the behavior of social groups. Psychologists use the scientific method to investigate questions both systematically and empirically.

Research in psychology is important because it provides us with valuable information that helps to improve human lives. By learning more about the brain, cognition, behavior, and mental health conditions, researchers are able to solve real-world problems that affect our day-to-day lives.

At a Glance

Knowing more about how research in psychology is conducted can give you a better understanding of what those findings might mean to you. Psychology experiments can range from simple to complex, but there are some basic terms and concepts that all psychology students should understand.

Start your studies by learning more about the different types of research, the basics of experimental design, and the relationships between variables.

Research in Psychology: The Basics

The first step in your review should include a basic introduction to psychology research methods . Psychology research can have a variety of goals. What researchers learn can be used to describe, explain, predict, or change human behavior.

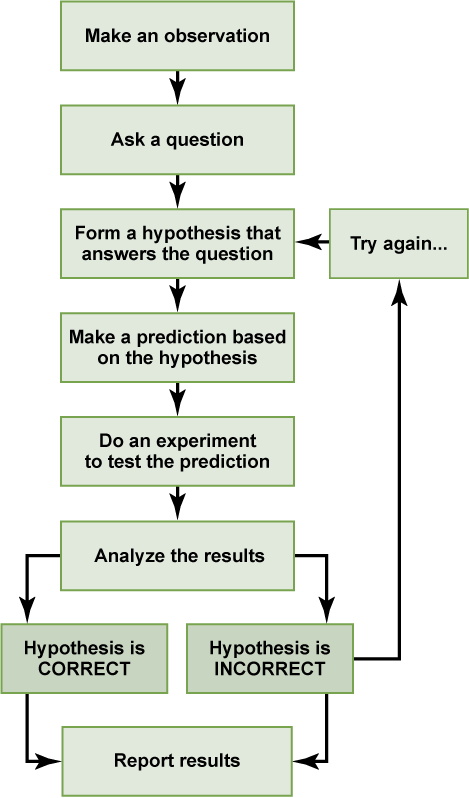

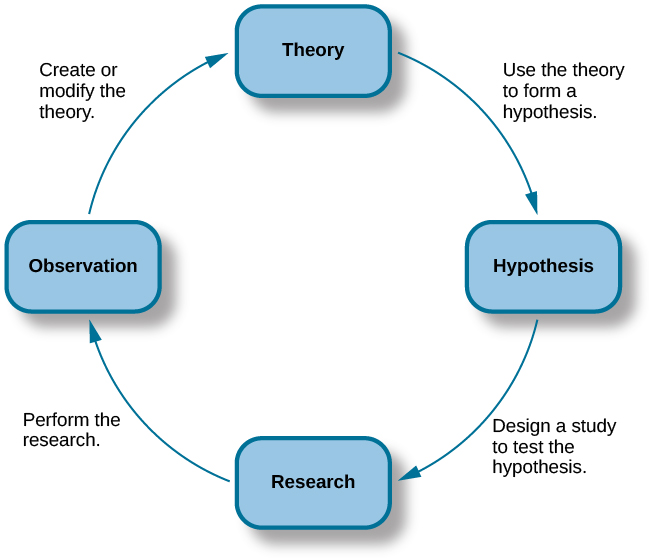

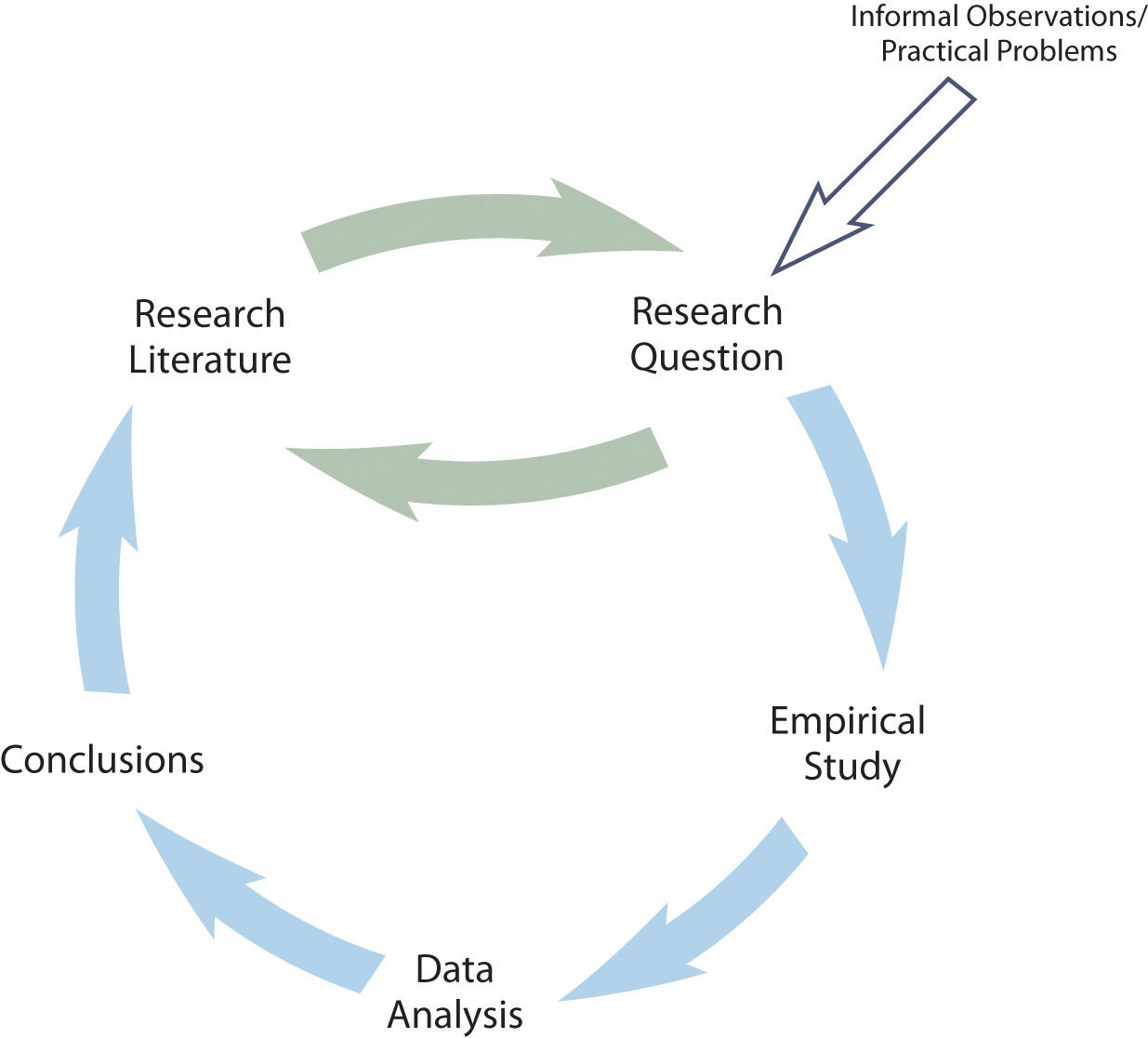

Psychologists use the scientific method to conduct studies and research in psychology. The basic process of conducting psychology research involves asking a question, designing a study, collecting data, analyzing results, reaching conclusions, and sharing the findings.

The Scientific Method in Psychology Research

The steps of the scientific method in psychology research are:

- Make an observation

- Ask a research question and make predictions about what you expect to find

- Test your hypothesis and gather data

- Examine the results and form conclusions

- Report your findings

Research in psychology can take several different forms. It can describe a phenomenon, explore the causes of a phenomenon, or look at relationships between one or more variables. Three of the main types of psychological research focus on:

Descriptive Studies

This type of research can tell us more about what is happening in a specific population. It relies on techniques such as observation, surveys, and case studies.

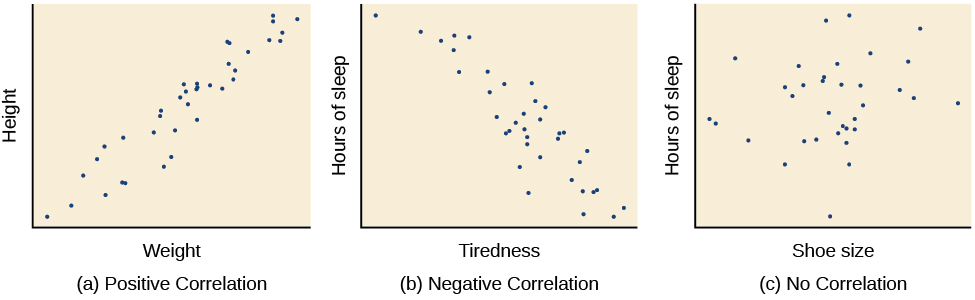

Correlational Studies

Correlational research is frequently used in psychology to look for relationships between variables. While research look at how variables are related, they do not manipulate any of the variables.

While correlational studies can suggest a relationship between two variables, finding a correlation does not prove that one variable causes a change in another. In other words, correlation does not equal causation.

Experimental Research Methods

Experiments are a research method that can look at whether changes in one variable cause changes in another. The simple experiment is one of the most basic methods of determining if there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

A simple experiment utilizes a control group of participants who receive no treatment and an experimental group of participants who receive the treatment.

Experimenters then compare the results of the two groups to determine if the treatment had an effect.

Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal Research in Psychology

Research in psychology can also involve collecting data at a single point in time, or gathering information at several points over a period of time.

Cross-Sectional Research

In a cross-sectional study , researchers collect data from participants at a single point in time. These are descriptive type of research and cannot be used to determine cause and effect because researchers do not manipulate the independent variables.

However, cross-sectional research does allow researchers to look at the characteristics of the population and explore relationships between different variables at a single point in time.

Longitudinal Research

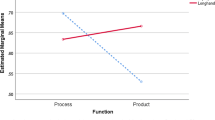

A longitudinal study is a type of research in psychology that involves looking at the same group of participants over a period of time. Researchers start by collecting initial data that serves as a baseline, and then collect follow-up data at certain intervals. These studies can last days, months, or years.

The longest longitudinal study in psychology was started in 1921 and the study is planned to continue until the last participant dies or withdraws. As of 2003, more than 200 of the partipants were still alive.

The Reliability and Validity of Research in Psychology

Reliability and validity are two concepts that are also critical in psychology research. In order to trust the results, we need to know if the findings are consistent (reliability) and that we are actually measuring what we think we are measuring (validity).

Reliability

Reliability is a vital component of a valid psychological test. What is reliability? How do we measure it? Simply put, reliability refers to the consistency of a measure. A test is considered reliable if we get the same result repeatedly.

When determining the merits of a psychological test, validity is one of the most important factors to consider. What exactly is validity? One of the greatest concerns when creating a psychological test is whether or not it actually measures what we think it is measuring.

For example, a test might be designed to measure a stable personality trait but instead measures transitory emotions generated by situational or environmental conditions. A valid test ensures that the results accurately reflect the dimension undergoing assessment.

Review some of the key terms that you should know and understand about psychology research methods. Spend some time studying these terms and definitions before your exam. Some key terms that you should know include:

- Correlation

- Demand characteristic

- Dependent variable

- Hawthorne effect

- Independent variable

- Naturalistic observation

- Placebo effect

- Random assignment

- Replication

- Selective attrition

Erol A. How to conduct scientific research ? Noro Psikiyatr Ars . 2017;54(2):97-98. doi:10.5152/npa.2017.0120102

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Curtis EA, Comiskey C, Dempsey O. Importance and use of correlational research . Nurse Res . 2016;23(6):20-25. doi:10.7748/nr.2016.e1382

Wang X, Cheng Z. Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations . Chest . 2020;158(1S):S65-S71. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012

Caruana EJ, Roman M, Hernández-Sánchez J, Solli P. Longitudinal studies . J Thorac Dis . 2015;7(11):E537-E540. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.63

Stanford Magazine. The vexing legacy of Lewis Terman .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Res Metr Anal

The Use of Research Methods in Psychological Research: A Systematised Review

Salomé elizabeth scholtz.

1 Community Psychosocial Research (COMPRES), School of Psychosocial Health, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Werner de Klerk

Leon t. de beer.

2 WorkWell Research Institute, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Research methods play an imperative role in research quality as well as educating young researchers, however, the application thereof is unclear which can be detrimental to the field of psychology. Therefore, this systematised review aimed to determine what research methods are being used, how these methods are being used and for what topics in the field. Our review of 999 articles from five journals over a period of 5 years indicated that psychology research is conducted in 10 topics via predominantly quantitative research methods. Of these 10 topics, social psychology was the most popular. The remainder of the conducted methodology is described. It was also found that articles lacked rigour and transparency in the used methodology which has implications for replicability. In conclusion this article, provides an overview of all reported methodologies used in a sample of psychology journals. It highlights the popularity and application of methods and designs throughout the article sample as well as an unexpected lack of rigour with regard to most aspects of methodology. Possible sample bias should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. It is recommended that future research should utilise the results of this study to determine the possible impact on the field of psychology as a science and to further investigation into the use of research methods. Results should prompt the following future research into: a lack or rigour and its implication on replication, the use of certain methods above others, publication bias and choice of sampling method.

Introduction

Psychology is an ever-growing and popular field (Gough and Lyons, 2016 ; Clay, 2017 ). Due to this growth and the need for science-based research to base health decisions on (Perestelo-Pérez, 2013 ), the use of research methods in the broad field of psychology is an essential point of investigation (Stangor, 2011 ; Aanstoos, 2014 ). Research methods are therefore viewed as important tools used by researchers to collect data (Nieuwenhuis, 2016 ) and include the following: quantitative, qualitative, mixed method and multi method (Maree, 2016 ). Additionally, researchers also employ various types of literature reviews to address research questions (Grant and Booth, 2009 ). According to literature, what research method is used and why a certain research method is used is complex as it depends on various factors that may include paradigm (O'Neil and Koekemoer, 2016 ), research question (Grix, 2002 ), or the skill and exposure of the researcher (Nind et al., 2015 ). How these research methods are employed is also difficult to discern as research methods are often depicted as having fixed boundaries that are continuously crossed in research (Johnson et al., 2001 ; Sandelowski, 2011 ). Examples of this crossing include adding quantitative aspects to qualitative studies (Sandelowski et al., 2009 ), or stating that a study used a mixed-method design without the study having any characteristics of this design (Truscott et al., 2010 ).

The inappropriate use of research methods affects how students and researchers improve and utilise their research skills (Scott Jones and Goldring, 2015 ), how theories are developed (Ngulube, 2013 ), and the credibility of research results (Levitt et al., 2017 ). This, in turn, can be detrimental to the field (Nind et al., 2015 ), journal publication (Ketchen et al., 2008 ; Ezeh et al., 2010 ), and attempts to address public social issues through psychological research (Dweck, 2017 ). This is especially important given the now well-known replication crisis the field is facing (Earp and Trafimow, 2015 ; Hengartner, 2018 ).

Due to this lack of clarity on method use and the potential impact of inept use of research methods, the aim of this study was to explore the use of research methods in the field of psychology through a review of journal publications. Chaichanasakul et al. ( 2011 ) identify reviewing articles as the opportunity to examine the development, growth and progress of a research area and overall quality of a journal. Studies such as Lee et al. ( 1999 ) as well as Bluhm et al. ( 2011 ) review of qualitative methods has attempted to synthesis the use of research methods and indicated the growth of qualitative research in American and European journals. Research has also focused on the use of research methods in specific sub-disciplines of psychology, for example, in the field of Industrial and Organisational psychology Coetzee and Van Zyl ( 2014 ) found that South African publications tend to consist of cross-sectional quantitative research methods with underrepresented longitudinal studies. Qualitative studies were found to make up 21% of the articles published from 1995 to 2015 in a similar study by O'Neil and Koekemoer ( 2016 ). Other methods in health psychology, such as Mixed methods research have also been reportedly growing in popularity (O'Cathain, 2009 ).

A broad overview of the use of research methods in the field of psychology as a whole is however, not available in the literature. Therefore, our research focused on answering what research methods are being used, how these methods are being used and for what topics in practice (i.e., journal publications) in order to provide a general perspective of method used in psychology publication. We synthesised the collected data into the following format: research topic [areas of scientific discourse in a field or the current needs of a population (Bittermann and Fischer, 2018 )], method [data-gathering tools (Nieuwenhuis, 2016 )], sampling [elements chosen from a population to partake in research (Ritchie et al., 2009 )], data collection [techniques and research strategy (Maree, 2016 )], and data analysis [discovering information by examining bodies of data (Ktepi, 2016 )]. A systematised review of recent articles (2013 to 2017) collected from five different journals in the field of psychological research was conducted.

Grant and Booth ( 2009 ) describe systematised reviews as the review of choice for post-graduate studies, which is employed using some elements of a systematic review and seldom more than one or two databases to catalogue studies after a comprehensive literature search. The aspects used in this systematised review that are similar to that of a systematic review were a full search within the chosen database and data produced in tabular form (Grant and Booth, 2009 ).

Sample sizes and timelines vary in systematised reviews (see Lowe and Moore, 2014 ; Pericall and Taylor, 2014 ; Barr-Walker, 2017 ). With no clear parameters identified in the literature (see Grant and Booth, 2009 ), the sample size of this study was determined by the purpose of the sample (Strydom, 2011 ), and time and cost constraints (Maree and Pietersen, 2016 ). Thus, a non-probability purposive sample (Ritchie et al., 2009 ) of the top five psychology journals from 2013 to 2017 was included in this research study. Per Lee ( 2015 ) American Psychological Association (APA) recommends the use of the most up-to-date sources for data collection with consideration of the context of the research study. As this research study focused on the most recent trends in research methods used in the broad field of psychology, the identified time frame was deemed appropriate.

Psychology journals were only included if they formed part of the top five English journals in the miscellaneous psychology domain of the Scimago Journal and Country Rank (Scimago Journal & Country Rank, 2017 ). The Scimago Journal and Country Rank provides a yearly updated list of publicly accessible journal and country-specific indicators derived from the Scopus® database (Scopus, 2017b ) by means of the Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) indicator developed by Scimago from the algorithm Google PageRank™ (Scimago Journal & Country Rank, 2017 ). Scopus is the largest global database of abstracts and citations from peer-reviewed journals (Scopus, 2017a ). Reasons for the development of the Scimago Journal and Country Rank list was to allow researchers to assess scientific domains, compare country rankings, and compare and analyse journals (Scimago Journal & Country Rank, 2017 ), which supported the aim of this research study. Additionally, the goals of the journals had to focus on topics in psychology in general with no preference to specific research methods and have full-text access to articles.

The following list of top five journals in 2018 fell within the abovementioned inclusion criteria (1) Australian Journal of Psychology, (2) British Journal of Psychology, (3) Europe's Journal of Psychology, (4) International Journal of Psychology and lastly the (5) Journal of Psychology Applied and Interdisciplinary.

Journals were excluded from this systematised review if no full-text versions of their articles were available, if journals explicitly stated a publication preference for certain research methods, or if the journal only published articles in a specific discipline of psychological research (for example, industrial psychology, clinical psychology etc.).

The researchers followed a procedure (see Figure 1 ) adapted from that of Ferreira et al. ( 2016 ) for systematised reviews. Data collection and categorisation commenced on 4 December 2017 and continued until 30 June 2019. All the data was systematically collected and coded manually (Grant and Booth, 2009 ) with an independent person acting as co-coder. Codes of interest included the research topic, method used, the design used, sampling method, and methodology (the method used for data collection and data analysis). These codes were derived from the wording in each article. Themes were created based on the derived codes and checked by the co-coder. Lastly, these themes were catalogued into a table as per the systematised review design.

Systematised review procedure.

According to Johnston et al. ( 2019 ), “literature screening, selection, and data extraction/analyses” (p. 7) are specifically tailored to the aim of a review. Therefore, the steps followed in a systematic review must be reported in a comprehensive and transparent manner. The chosen systematised design adhered to the rigour expected from systematic reviews with regard to full search and data produced in tabular form (Grant and Booth, 2009 ). The rigorous application of the systematic review is, therefore discussed in relation to these two elements.

Firstly, to ensure a comprehensive search, this research study promoted review transparency by following a clear protocol outlined according to each review stage before collecting data (Johnston et al., 2019 ). This protocol was similar to that of Ferreira et al. ( 2016 ) and approved by three research committees/stakeholders and the researchers (Johnston et al., 2019 ). The eligibility criteria for article inclusion was based on the research question and clearly stated, and the process of inclusion was recorded on an electronic spreadsheet to create an evidence trail (Bandara et al., 2015 ; Johnston et al., 2019 ). Microsoft Excel spreadsheets are a popular tool for review studies and can increase the rigour of the review process (Bandara et al., 2015 ). Screening for appropriate articles for inclusion forms an integral part of a systematic review process (Johnston et al., 2019 ). This step was applied to two aspects of this research study: the choice of eligible journals and articles to be included. Suitable journals were selected by the first author and reviewed by the second and third authors. Initially, all articles from the chosen journals were included. Then, by process of elimination, those irrelevant to the research aim, i.e., interview articles or discussions etc., were excluded.

To ensure rigourous data extraction, data was first extracted by one reviewer, and an independent person verified the results for completeness and accuracy (Johnston et al., 2019 ). The research question served as a guide for efficient, organised data extraction (Johnston et al., 2019 ). Data was categorised according to the codes of interest, along with article identifiers for audit trails such as authors, title and aims of articles. The categorised data was based on the aim of the review (Johnston et al., 2019 ) and synthesised in tabular form under methods used, how these methods were used, and for what topics in the field of psychology.

The initial search produced a total of 1,145 articles from the 5 journals identified. Inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in a final sample of 999 articles ( Figure 2 ). Articles were co-coded into 84 codes, from which 10 themes were derived ( Table 1 ).

Journal article frequency.

Codes used to form themes (research topics).

| Social Psychology | 31 | Aggression SP, Attitude SP, Belief SP, Child abuse SP, Conflict SP, Culture SP, Discrimination SP, Economic, Family illness, Family, Group, Help, Immigration, Intergeneration, Judgement, Law, Leadership, Marriage SP, Media, Optimism, Organisational and Social justice, Parenting SP, Politics, Prejudice, Relationships, Religion, Romantic Relationships SP, Sex and attraction, Stereotype, Violence, Work |

| Experimental Psychology | 17 | Anxiety, stress and PTSD, Coping, Depression, Emotion, Empathy, Facial research, Fear and threat, Happiness, Humor, Mindfulness, Mortality, Motivation and Achievement, Perception, Rumination, Self, Self-efficacy |

| Cognitive Psychology | 12 | Attention, Cognition, Decision making, Impulse, Intelligence, Language, Math, Memory, Mental, Number, Problem solving, Reading |

| Health Psychology | 7 | Addiction, Body, Burnout, Health, Illness (Health Psychology), Sleep (Health Psychology), Suicide and Self-harm |

| Physiological Psychology | 6 | Gender, Health (Physiological psychology), Illness (Physiological psychology), Mood disorders, Sleep (Physiological psychology), Visual research |

| Developmental Psychology | 3 | Attachment, Development, Old age |

| Personality | 3 | Machiavellian, Narcissism, Personality |

| Psychological Psychology | 3 | Programme, Psychology practice, Theory |

| Education and Learning | 1 | Education and Learning |

| Psychometrics | 1 | Measure |

| Code Total | 84 |

These 10 themes represent the topic section of our research question ( Figure 3 ). All these topics except, for the final one, psychological practice , were found to concur with the research areas in psychology as identified by Weiten ( 2010 ). These research areas were chosen to represent the derived codes as they provided broad definitions that allowed for clear, concise categorisation of the vast amount of data. Article codes were categorised under particular themes/topics if they adhered to the research area definitions created by Weiten ( 2010 ). It is important to note that these areas of research do not refer to specific disciplines in psychology, such as industrial psychology; but to broader fields that may encompass sub-interests of these disciplines.

Topic frequency (international sample).

In the case of developmental psychology , researchers conduct research into human development from childhood to old age. Social psychology includes research on behaviour governed by social drivers. Researchers in the field of educational psychology study how people learn and the best way to teach them. Health psychology aims to determine the effect of psychological factors on physiological health. Physiological psychology , on the other hand, looks at the influence of physiological aspects on behaviour. Experimental psychology is not the only theme that uses experimental research and focuses on the traditional core topics of psychology (for example, sensation). Cognitive psychology studies the higher mental processes. Psychometrics is concerned with measuring capacity or behaviour. Personality research aims to assess and describe consistency in human behaviour (Weiten, 2010 ). The final theme of psychological practice refers to the experiences, techniques, and interventions employed by practitioners, researchers, and academia in the field of psychology.

Articles under these themes were further subdivided into methodologies: method, sampling, design, data collection, and data analysis. The categorisation was based on information stated in the articles and not inferred by the researchers. Data were compiled into two sets of results presented in this article. The first set addresses the aim of this study from the perspective of the topics identified. The second set of results represents a broad overview of the results from the perspective of the methodology employed. The second set of results are discussed in this article, while the first set is presented in table format. The discussion thus provides a broad overview of methods use in psychology (across all themes), while the table format provides readers with in-depth insight into methods used in the individual themes identified. We believe that presenting the data from both perspectives allow readers a broad understanding of the results. Due a large amount of information that made up our results, we followed Cichocka and Jost ( 2014 ) in simplifying our results. Please note that the numbers indicated in the table in terms of methodology differ from the total number of articles. Some articles employed more than one method/sampling technique/design/data collection method/data analysis in their studies.

What follows is the results for what methods are used, how these methods are used, and which topics in psychology they are applied to . Percentages are reported to the second decimal in order to highlight small differences in the occurrence of methodology.

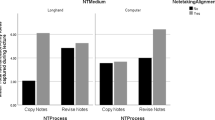

Firstly, with regard to the research methods used, our results show that researchers are more likely to use quantitative research methods (90.22%) compared to all other research methods. Qualitative research was the second most common research method but only made up about 4.79% of the general method usage. Reviews occurred almost as much as qualitative studies (3.91%), as the third most popular method. Mixed-methods research studies (0.98%) occurred across most themes, whereas multi-method research was indicated in only one study and amounted to 0.10% of the methods identified. The specific use of each method in the topics identified is shown in Table 2 and Figure 4 .

Research methods in psychology.

| Quantitative | 401 | 162 | 69 | 60 | 52 | 52 | 48 | 28 | 38 | 13 |

| Qualitative | 28 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Review | 11 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 1 |

| Mixed Methods | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Multi-method | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 447 | 171 | 72 | 60 | 61 | 58 | 53 | 47 | 39 | 15 |

Research method frequency in topics.

Secondly, in the case of how these research methods are employed , our study indicated the following.

Sampling −78.34% of the studies in the collected articles did not specify a sampling method. From the remainder of the studies, 13 types of sampling methods were identified. These sampling methods included broad categorisation of a sample as, for example, a probability or non-probability sample. General samples of convenience were the methods most likely to be applied (10.34%), followed by random sampling (3.51%), snowball sampling (2.73%), and purposive (1.37%) and cluster sampling (1.27%). The remainder of the sampling methods occurred to a more limited extent (0–1.0%). See Table 3 and Figure 5 for sampling methods employed in each topic.

Sampling use in the field of psychology.

| Not stated | 331 | 153 | 45 | 57 | 49 | 43 | 43 | 38 | 31 | 14 |

| Convenience sampling | 55 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| Random sampling | 15 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Snowball sampling | 14 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Purposive sampling | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Cluster sampling | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stratified sampling | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-probability sampling | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Probability sampling | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quota sampling | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Criterion sampling | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-selection sampling | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unsystematic sampling | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 443 | 172 | 76 | 60 | 60 | 58 | 52 | 48 | 40 | 16 |

Sampling method frequency in topics.

Designs were categorised based on the articles' statement thereof. Therefore, it is important to note that, in the case of quantitative studies, non-experimental designs (25.55%) were often indicated due to a lack of experiments and any other indication of design, which, according to Laher ( 2016 ), is a reasonable categorisation. Non-experimental designs should thus be compared with experimental designs only in the description of data, as it could include the use of correlational/cross-sectional designs, which were not overtly stated by the authors. For the remainder of the research methods, “not stated” (7.12%) was assigned to articles without design types indicated.

From the 36 identified designs the most popular designs were cross-sectional (23.17%) and experimental (25.64%), which concurred with the high number of quantitative studies. Longitudinal studies (3.80%), the third most popular design, was used in both quantitative and qualitative studies. Qualitative designs consisted of ethnography (0.38%), interpretative phenomenological designs/phenomenology (0.28%), as well as narrative designs (0.28%). Studies that employed the review method were mostly categorised as “not stated,” with the most often stated review designs being systematic reviews (0.57%). The few mixed method studies employed exploratory, explanatory (0.09%), and concurrent designs (0.19%), with some studies referring to separate designs for the qualitative and quantitative methods. The one study that identified itself as a multi-method study used a longitudinal design. Please see how these designs were employed in each specific topic in Table 4 , Figure 6 .

Design use in the field of psychology.

| Experimental design | 82 | 82 | 3 | 60 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Non-experimental design | 115 | 30 | 51 | 0 | 13 | 17 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 3 |

| Cross-sectional design | 123 | 31 | 12 | 1 | 19 | 17 | 21 | 5 | 13 | 2 |

| Correlational design | 56 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Not stated | 37 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 3 |

| Longitudinal design | 21 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Quasi-experimental design | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Systematic review | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cross-cultural design | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Descriptive design | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethnography | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Literature review | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Narrative design | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Case-control research design | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Concurrent data collection design | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grounded Theory | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Narrative review | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Auto-ethnography | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case series evaluation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Case study | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Comprehensive review | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Descriptive-inferential | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Explanatory sequential design | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exploratory mixed-method | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Grounded ethnographic design | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Historical cohort design | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Historical research | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| interpretivist approach | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Meta-review | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Prospective design | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Qualitative review | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Qualitative systematic review | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Short-term prospective design | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 461 | 175 | 74 | 63 | 63 | 58 | 56 | 48 | 39 | 16 |

Design frequency in topics.

Data collection and analysis —data collection included 30 methods, with the data collection method most often employed being questionnaires (57.84%). The experimental task (16.56%) was the second most preferred collection method, which included established or unique tasks designed by the researchers. Cognitive ability tests (6.84%) were also regularly used along with various forms of interviewing (7.66%). Table 5 and Figure 7 represent data collection use in the various topics. Data analysis consisted of 3,857 occurrences of data analysis categorised into ±188 various data analysis techniques shown in Table 6 and Figures 1 – 7 . Descriptive statistics were the most commonly used (23.49%) along with correlational analysis (17.19%). When using a qualitative method, researchers generally employed thematic analysis (0.52%) or different forms of analysis that led to coding and the creation of themes. Review studies presented few data analysis methods, with most studies categorising their results. Mixed method and multi-method studies followed the analysis methods identified for the qualitative and quantitative studies included.

Data collection in the field of psychology.

| Questionnaire | 364 | 113 | 65 | 42 | 40 | 51 | 39 | 24 | 37 | 11 |

| Experimental task | 68 | 66 | 3 | 52 | 9 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Cognitive ability test | 9 | 57 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Physiological measure | 3 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Interview | 19 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Online scholarly literature | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Open-ended questions | 15 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Semi-structured interviews | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Observation | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Documents | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Focus group | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not stated | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Public data | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Drawing task | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| In-depth interview | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Structured interview | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Writing task | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Questionnaire interviews | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-experimental task | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tests | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group accounts | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Open-ended prompts | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Field notes | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Open-ended interview | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Qualitative questions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Social media | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Assessment procedure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Closed-ended questions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Open discussions | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Qualitative descriptions | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 551 | 273 | 75 | 116 | 79 | 73 | 65 | 60 | 50 | 17 |

Data collection frequency in topics.

Data analysis in the field of psychology.

| Not stated | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) | 17 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | 112 | 60 | 16 | 29 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| Auto-regressive path coefficients | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Average variance extracted (AVE) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bartholomew's classification system | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bayesian analysis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bibliometric analysis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Binary logistic regression | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Binary multilevel regression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Binomial and Bernoulli regression models | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Binomial mixed effects model | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bivariate Correlations | 32 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bivariate logistic correlations | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bootstrapping | 39 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Canonical correlations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Cartesian diagram | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case-wise diagnostics | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Casual network analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Categorisation | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Categorisation of responses | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Category codes | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cattell's scree-test | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chi-square tests | 52 | 20 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Classic Parallel Analysis (PA) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cluster analysis | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Coded | 15 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Cohen d effect size | 14 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Common method variance (CMV) | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Confidence Interval (CI) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) | 57 | 13 | 40 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Content analysis | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Convergent validity | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cook's distance | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Correlated-trait-correlated-method minus one model | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Correlational analysis | 259 | 85 | 44 | 18 | 27 | 31 | 34 | 8 | 33 | 8 |

| Covariance matrix | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Covariance modelling | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Covariance structure analyses | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cronbach's alpha | 61 | 14 | 18 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| Cross-validation | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cross-lagged analyses | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dependent t-test | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Descriptive statistics | 324 | 132 | 43 | 49 | 41 | 43 | 36 | 28 | 29 | 10 |

| Differentiated analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Discriminate analysis | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Discursive psychology | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dominance analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Expectation maximisation | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Exploratory data Analysis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) | 14 | 5 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Factor analysis | 12 | 4 | 16 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Measurement invariance testing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Four-way mixed ANOVA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Frequency rate | 20 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Friedman test | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Games-Howell | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General linear model analysis | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Greenhouse-Geisser correction | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Grounded theory method | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Grounded theory methodology using open and axial coding | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Guttman split-half | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Harman's one-factor test | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Herman's criteria of experience categorisation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hierarchical CFA (HCFA) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hierarchical cluster analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hierarchical Linear Modelling (HLM) | 76 | 22 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Huynh-Felt correction | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Identified themes | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Independent samples t-test | 38 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Inductive open coding | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inferential statistics | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interclass correlation | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Internal consistency | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interpreted and defined | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Item fit analysis | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| K-means clustering | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Kaiser-meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Kendall's coefficients | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov test | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Lagged-effects multilevel modelling | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latent class differentiation (LCD) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latent cluster analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latent growth curve modelling (LGCM) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Latent means | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Linear regressions | 69 | 19 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 0 |

| Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Listwise deletion method | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Log-likelihood ratios | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Logistic mixed-effects model | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Logistic regression analyses | 17 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Loglinear Model | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mahalanobis distances | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mann-Whitney U tests | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Mauchly's test | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Maximum likelihood method | 11 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Maximum-likelihood factor analysis with promax rotation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Measurement invariance testing | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mediation analysis | 29 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Meta-analysis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Microanalysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Minimum significant difference (MSD) comparison | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed ANOVAs | 19 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Mixed linear model | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed-design ANCOVA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed-effects multiple regression models | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderated hierarchical regression model | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderated regression analysis | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Monte Carlo Markov Chains | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multi-group analysis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multidimensional Random Coefficient Multinomial Logit (MRCML) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multidimensional Scaling | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MGCFA) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multilevel latent class analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multilevel modelling | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Multilevel Structural Equation Modelling (MSEM) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multinominal logistic regression (MLR) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multinominal regression analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple mediation analysis | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple regression | 34 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| Multivariate analysis of co-variance (MANCOVA) | 12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) | 38 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Multivariate hierarchical linear regression | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multivariate linear regression | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multivariate logistic regression analyses | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multivariate regressions | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nagelkerke's R square | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Narrative analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative binominal regression with log link | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Newman-Keuls | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nomological Validity Analysis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| One sample t-test | 8 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ordinary Least-Square regression (OLS) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pairwise deletion method | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pairwise parameter comparison | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parametric Analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Partial Least Squares regression method (PLS) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Path analysis | 21 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Path-analytic model test | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phenomenological analysis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Polynomial regression analyses | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fisher LSD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Principal axis factoring | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Principal component analysis (PCA) | 8 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Pseudo-panel regression | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quantitative content analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Relative weight analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Repeated measures analyses of variances (rANOVA) | 18 | 22 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ryan-Einot-Gabriel-Welsch multiple F test | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square statistic | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scheffe's test | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sequential multiple mediation analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shapiro-Wilk test | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sobel Test | 13 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Squared multiple correlations | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Squared semi-partial correlations (sr2) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stepwise regression analysis | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) | 56 | 22 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| Structure analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subsequent t-test | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Systematic coding- Gemeinschaft-oriented | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Task analysis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thematic analysis | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Three (condition)-way ANOVA | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Three-way hierarchical loglinear analysis | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tukey-Kramer corrections | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Two-paired sample t-test | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Two-tailed related t-test | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unadjusted Logistic regression analysis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Univariate generalized linear models (GLM) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Variance inflation factor (VIF) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Variance-covariance matrix | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Wald test | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ward's hierarchical cluster method | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Weighted least squares with corrections to means and variances (WLSMV) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Welch and Brown-Forsythe F-ratios | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Wilks' Lamba | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Word analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Word Association Analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| scores | 5 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1738 | 635 | 329 | 192 | 198 | 237 | 225 | 117 | 152 | 55 |

Results of the topics researched in psychology can be seen in the tables, as previously stated in this article. It is noteworthy that, of the 10 topics, social psychology accounted for 43.54% of the studies, with cognitive psychology the second most popular research topic at 16.92%. The remainder of the topics only occurred in 4.0–7.0% of the articles considered. A list of the included 999 articles is available under the section “View Articles” on the following website: https://methodgarden.xtrapolate.io/ . This website was created by Scholtz et al. ( 2019 ) to visually present a research framework based on this Article's results.

This systematised review categorised full-length articles from five international journals across the span of 5 years to provide insight into the use of research methods in the field of psychology. Results indicated what methods are used how these methods are being used and for what topics (why) in the included sample of articles. The results should be seen as providing insight into method use and by no means a comprehensive representation of the aforementioned aim due to the limited sample. To our knowledge, this is the first research study to address this topic in this manner. Our discussion attempts to promote a productive way forward in terms of the key results for method use in psychology, especially in the field of academia (Holloway, 2008 ).

With regard to the methods used, our data stayed true to literature, finding only common research methods (Grant and Booth, 2009 ; Maree, 2016 ) that varied in the degree to which they were employed. Quantitative research was found to be the most popular method, as indicated by literature (Breen and Darlaston-Jones, 2010 ; Counsell and Harlow, 2017 ) and previous studies in specific areas of psychology (see Coetzee and Van Zyl, 2014 ). Its long history as the first research method (Leech et al., 2007 ) in the field of psychology as well as researchers' current application of mathematical approaches in their studies (Toomela, 2010 ) might contribute to its popularity today. Whatever the case may be, our results show that, despite the growth in qualitative research (Demuth, 2015 ; Smith and McGannon, 2018 ), quantitative research remains the first choice for article publication in these journals. Despite the included journals indicating openness to articles that apply any research methods. This finding may be due to qualitative research still being seen as a new method (Burman and Whelan, 2011 ) or reviewers' standards being higher for qualitative studies (Bluhm et al., 2011 ). Future research is encouraged into the possible biasness in publication of research methods, additionally further investigation with a different sample into the proclaimed growth of qualitative research may also provide different results.

Review studies were found to surpass that of multi-method and mixed method studies. To this effect Grant and Booth ( 2009 ), state that the increased awareness, journal contribution calls as well as its efficiency in procuring research funds all promote the popularity of reviews. The low frequency of mixed method studies contradicts the view in literature that it's the third most utilised research method (Tashakkori and Teddlie's, 2003 ). Its' low occurrence in this sample could be due to opposing views on mixing methods (Gunasekare, 2015 ) or that authors prefer publishing in mixed method journals, when using this method, or its relative novelty (Ivankova et al., 2016 ). Despite its low occurrence, the application of the mixed methods design in articles was methodologically clear in all cases which were not the case for the remainder of research methods.

Additionally, a substantial number of studies used a combination of methodologies that are not mixed or multi-method studies. Perceived fixed boundaries are according to literature often set aside, as confirmed by this result, in order to investigate the aim of a study, which could create a new and helpful way of understanding the world (Gunasekare, 2015 ). According to Toomela ( 2010 ), this is not unheard of and could be considered a form of “structural systemic science,” as in the case of qualitative methodology (observation) applied in quantitative studies (experimental design) for example. Based on this result, further research into this phenomenon as well as its implications for research methods such as multi and mixed methods is recommended.

Discerning how these research methods were applied, presented some difficulty. In the case of sampling, most studies—regardless of method—did mention some form of inclusion and exclusion criteria, but no definite sampling method. This result, along with the fact that samples often consisted of students from the researchers' own academic institutions, can contribute to literature and debates among academics (Peterson and Merunka, 2014 ; Laher, 2016 ). Samples of convenience and students as participants especially raise questions about the generalisability and applicability of results (Peterson and Merunka, 2014 ). This is because attention to sampling is important as inappropriate sampling can debilitate the legitimacy of interpretations (Onwuegbuzie and Collins, 2017 ). Future investigation into the possible implications of this reported popular use of convenience samples for the field of psychology as well as the reason for this use could provide interesting insight, and is encouraged by this study.

Additionally, and this is indicated in Table 6 , articles seldom report the research designs used, which highlights the pressing aspect of the lack of rigour in the included sample. Rigour with regards to the applied empirical method is imperative in promoting psychology as a science (American Psychological Association, 2020 ). Omitting parts of the research process in publication when it could have been used to inform others' research skills should be questioned, and the influence on the process of replicating results should be considered. Publications are often rejected due to a lack of rigour in the applied method and designs (Fonseca, 2013 ; Laher, 2016 ), calling for increased clarity and knowledge of method application. Replication is a critical part of any field of scientific research and requires the “complete articulation” of the study methods used (Drotar, 2010 , p. 804). The lack of thorough description could be explained by the requirements of certain journals to only report on certain aspects of a research process, especially with regard to the applied design (Laher, 20). However, naming aspects such as sampling and designs, is a requirement according to the APA's Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS-Quant) (Appelbaum et al., 2018 ). With very little information on how a study was conducted, authors lose a valuable opportunity to enhance research validity, enrich the knowledge of others, and contribute to the growth of psychology and methodology as a whole. In the case of this research study, it also restricted our results to only reported samples and designs, which indicated a preference for certain designs, such as cross-sectional designs for quantitative studies.

Data collection and analysis were for the most part clearly stated. A key result was the versatile use of questionnaires. Researchers would apply a questionnaire in various ways, for example in questionnaire interviews, online surveys, and written questionnaires across most research methods. This may highlight a trend for future research.

With regard to the topics these methods were employed for, our research study found a new field named “psychological practice.” This result may show the growing consciousness of researchers as part of the research process (Denzin and Lincoln, 2003 ), psychological practice, and knowledge generation. The most popular of these topics was social psychology, which is generously covered in journals and by learning societies, as testaments of the institutional support and richness social psychology has in the field of psychology (Chryssochoou, 2015 ). The APA's perspective on 2018 trends in psychology also identifies an increased amount of psychology focus on how social determinants are influencing people's health (Deangelis, 2017 ).

This study was not without limitations and the following should be taken into account. Firstly, this study used a sample of five specific journals to address the aim of the research study, despite general journal aims (as stated on journal websites), this inclusion signified a bias towards the research methods published in these specific journals only and limited generalisability. A broader sample of journals over a different period of time, or a single journal over a longer period of time might provide different results. A second limitation is the use of Excel spreadsheets and an electronic system to log articles, which was a manual process and therefore left room for error (Bandara et al., 2015 ). To address this potential issue, co-coding was performed to reduce error. Lastly, this article categorised data based on the information presented in the article sample; there was no interpretation of what methodology could have been applied or whether the methods stated adhered to the criteria for the methods used. Thus, a large number of articles that did not clearly indicate a research method or design could influence the results of this review. However, this in itself was also a noteworthy result. Future research could review research methods of a broader sample of journals with an interpretive review tool that increases rigour. Additionally, the authors also encourage the future use of systematised review designs as a way to promote a concise procedure in applying this design.

Our research study presented the use of research methods for published articles in the field of psychology as well as recommendations for future research based on these results. Insight into the complex questions identified in literature, regarding what methods are used how these methods are being used and for what topics (why) was gained. This sample preferred quantitative methods, used convenience sampling and presented a lack of rigorous accounts for the remaining methodologies. All methodologies that were clearly indicated in the sample were tabulated to allow researchers insight into the general use of methods and not only the most frequently used methods. The lack of rigorous account of research methods in articles was represented in-depth for each step in the research process and can be of vital importance to address the current replication crisis within the field of psychology. Recommendations for future research aimed to motivate research into the practical implications of the results for psychology, for example, publication bias and the use of convenience samples.

Ethics Statement

This study was cleared by the North-West University Health Research Ethics Committee: NWU-00115-17-S1.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Aanstoos C. M. (2014). Psychology . Available online at: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/eds/detail/detail?sid=18de6c5c-2b03-4eac-94890145eb01bc70%40sessionmgr4006&vid$=$1&hid$=$4113&bdata$=$JnNpdGU9ZWRzL~WxpdmU%3d#AN$=$93871882&db$=$ers

- American Psychological Association (2020). Science of Psychology . Available online at: https://www.apa.org/action/science/

- Appelbaum M., Cooper H., Kline R. B., Mayo-Wilson E., Nezu A. M., Rao S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: the APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . Am. Psychol. 73 :3. 10.1037/amp0000191 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandara W., Furtmueller E., Gorbacheva E., Miskon S., Beekhuyzen J. (2015). Achieving rigor in literature reviews: insights from qualitative data analysis and tool-support . Commun. Ass. Inform. Syst. 37 , 154–204. 10.17705/1CAIS.03708 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barr-Walker J. (2017). Evidence-based information needs of public health workers: a systematized review . J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 105 , 69–79. 10.5195/JMLA.2017.109 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bittermann A., Fischer A. (2018). How to identify hot topics in psychology using topic modeling . Z. Psychol. 226 , 3–13. 10.1027/2151-2604/a000318 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bluhm D. J., Harman W., Lee T. W., Mitchell T. R. (2011). Qualitative research in management: a decade of progress . J. Manage. Stud. 48 , 1866–1891. 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00972.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Breen L. J., Darlaston-Jones D. (2010). Moving beyond the enduring dominance of positivism in psychological research: implications for psychology in Australia . Aust. Psychol. 45 , 67–76. 10.1080/00050060903127481 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burman E., Whelan P. (2011). Problems in / of Qualitative Research . Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw Hill. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chaichanasakul A., He Y., Chen H., Allen G. E. K., Khairallah T. S., Ramos K. (2011). Journal of Career Development: a 36-year content analysis (1972–2007) . J. Career. Dev. 38 , 440–455. 10.1177/0894845310380223 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chryssochoou X. (2015). Social Psychology . Inter. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 22 , 532–537. 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24095-6 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]