149 American Revolution Essay Topics & Examples

If you’re looking for American Revolution topics for research paper or essay, you’re in the right place. This article contains everything you might need to write an essay on Revolutionary war

🗽 Top 7 American Revolution Research Topics

✍ american revolution essay: how to write, 🏆 american revolution essay examples, 📌 best american revolution essay topics, 💡 most interesting american revolution topics to write about, ⭐ interesting revolutionary war topics, 📃 american revolution topics for research paper, ❓ american revolution essay questions.

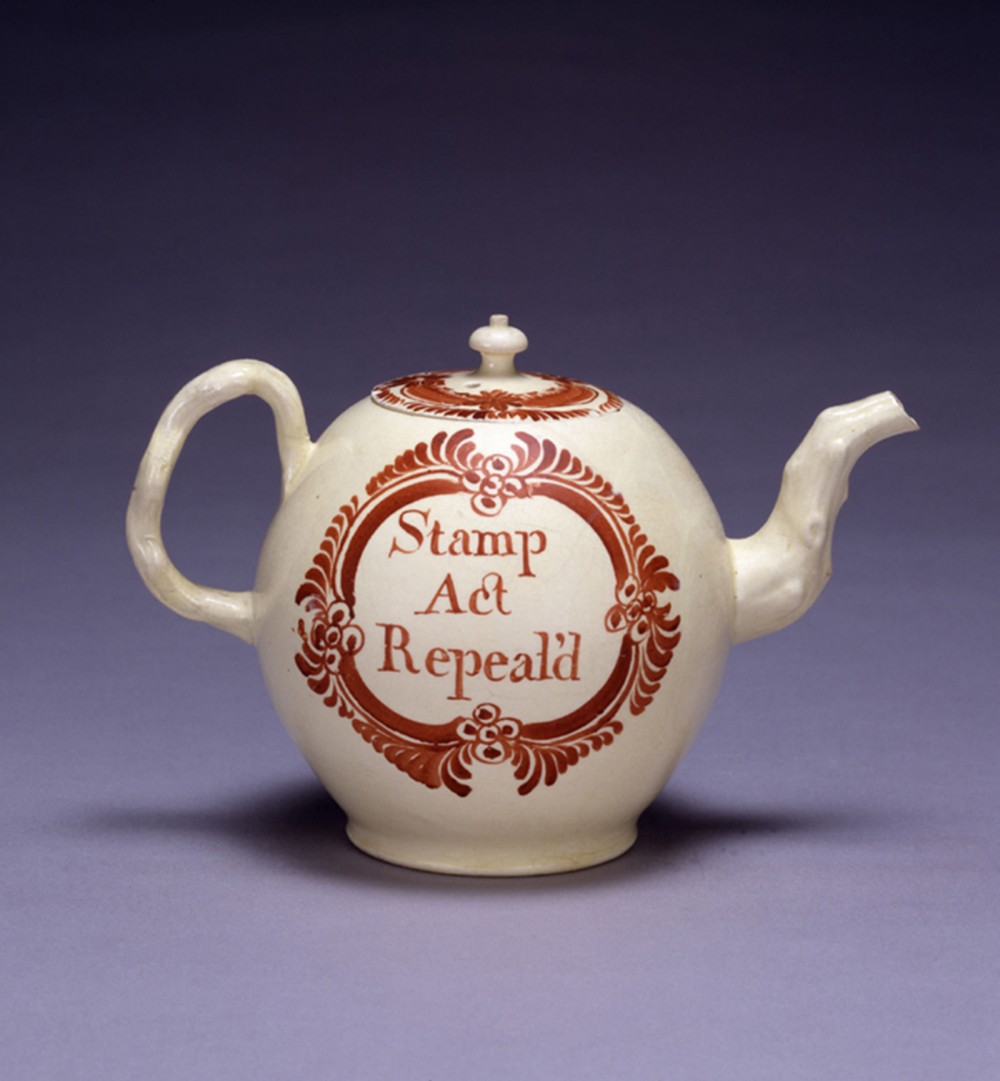

American Revolution, also known as Revolutionary War, occurred in the second half of the 18th century. Among its causes was a series of acts established by the Crown. These acts placed taxes on paint, tea, glass, and paper imported to the colonies. As a result of the war, the thirteen American colonies gained independence from the British Crown, thereby creating the United States of America. Whether you need to write an argumentative, persuasive, or discussion paper on the Revolutionary War, this article will be helpful. It contains American Revolution essay examples, titles, and questions for discussion. Boost your critical thinking with us!

- Townshend Acts and the Tea Act as the causes of the American Revolution

- Ideological roots of the American Revolution

- English government and the American colonies before the Revolutionary war

- Revolutionary War: the main participants

- The American Revolution: creating the new constitutions

- Causes and effects of the American Revolution

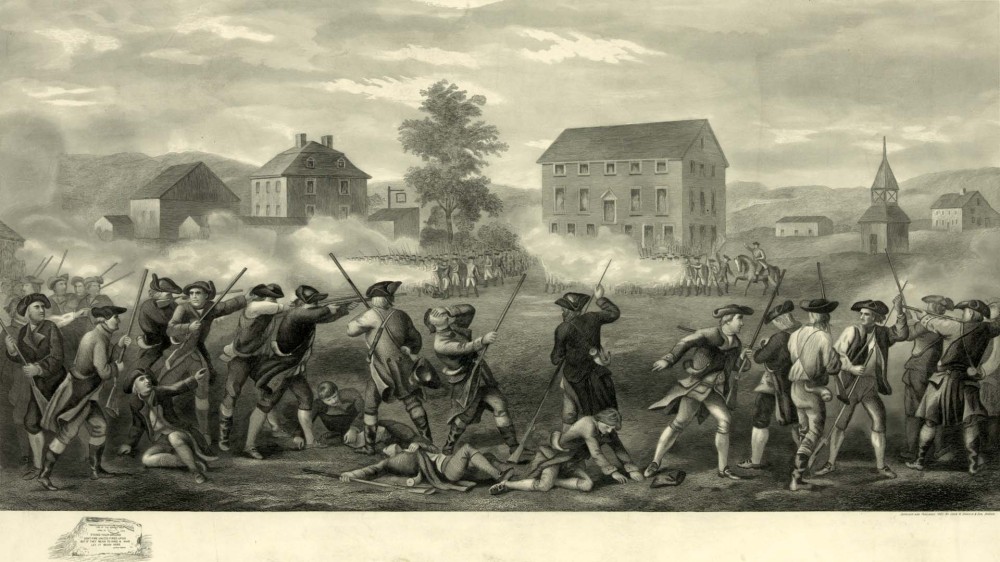

- Revolutionary War: the key battles

Signifying a cornerstone moment for British colonial politics and the creation of a new, fully sovereign nation, the events from 1765 to 1783 were unusual for the 18th century. Thus, reflecting all the crucial moments within a single American Revolution Essay becomes troublesome to achieve. However, if you keep in mind certain historical events, then you may affect the quality of your paper for the better.

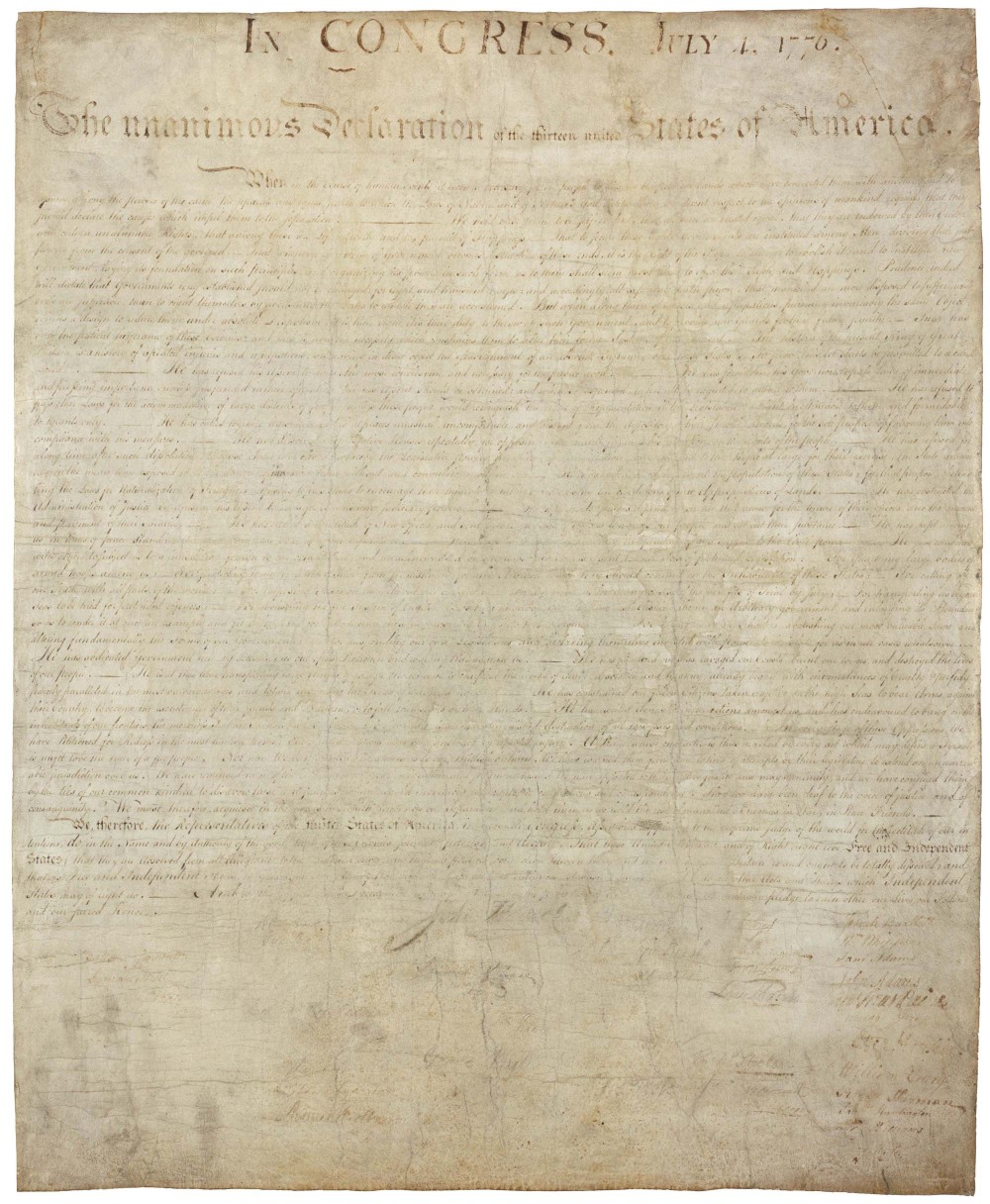

All American Revolution essay topics confine themselves to the situation and its effects. Make sure that you understand the chronology by searching for a timeline, or even create one yourself! Doing so should help you easily trace what date is relevant to which event and, thus, allow you to stay in touch with historical occurrences. Furthermore, understand the continuity of the topic, from the creation of the American colony until the Declaration of Independence. Creating a smooth flowing narrative that takes into consideration both the road to revolution and its aftereffects will demonstrate your comprehensive understanding of the issue.

When writing about the pre-history of the Revolution, pay special attention to ongoing background mechanisms of the time. The surge of patriotism, a strong desire for self-governed democracy, and “Identity American” all did not come into existence at the Boston Tea Party but merely demonstrated themselves most clearly at that time. Linking events together will become more manageable if you can understand the central motivation behind them.

Your structure is another essential aspect of essay writing, with a traditional outline following the events in chronological order, appropriately overviewing them when necessary. Thus, an excellent structure requires that your introduction should include:

- An American Revolution essay hook, which will pique your readers’ interest and make them want to read your work further. Writing in unexpected facts or giving a quote from a contemporary actor of the events, such as one of the founding fathers, are good hook examples because they grab your readers’ attention.

- A brief overview of the circumstances. It should be both in-depth enough to get your readers on the same level of knowledge as you, the writer, and short enough to engage them in your presented ideas.

- An American Revolution essay thesis that will guide your paper from introduction to conclusion. Between overviewing historical information and interest-piquing hooks, your thesis statement should be on-point and summarize the goal of your essay. When writing, you should often return to it, assessing whether the topics you are addressing are reflective of your paper’s goals.

Whatever issues you raise in your introduction and develop in your main body, you should bring them all together in your conclusion. Summarize your findings and compare them against your thesis statement. Doing so will help you carry out a proper verdict regarding the problem and its implications.

The research you have carried out and the resulting compiled bibliography titles will help you build your essay’s credibility. However, apart from reading up on the problem you are addressing, you should think about reading other sample essays. These may not only help you get inspired but also give excellent American Revolution essay titles and structure lessons. Nevertheless, remember that plagiarizing from these papers, or anywhere else, is not advisable! Avoid committing academic crimes and let your own ideas be representative of your academism.

Want to sample some essays to get your essay started? Kick-start your writing process with IvyPanda and its ideas!

- The American Revolution and Its Effects It is an acknowledgeable fact that the American Revolution was not a social revolution like the ones that were experienced in France, Russia or China, but it was a social revolution that was aimed at […]

- The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution: Book Analysis Even these facts from the author’s biography make “The Shoemaker and the Tea Party” a reliable source of the knowledge on the American past.”The Shoemaker and the Tea Party” is based on the story of […]

- Summary of “Abraham Lincoln” and “The Second American Revolution” by James M. McPherson According to McPherson, the war, that is, the Civil War, was aimed at bringing about liberty and ensuring the extension of protection to the citizenry which he had a clue of the fact that the […]

- Sex During the American Revolution American Revolution is one of the most prominent and groundbreaking events in the history of the United States of America. One of the most interesting facts from the video was the usage of clothing and […]

- The Heroes of the American Revolution However, their role was forgotten by the emergence of heroes such as Washington and Adams, white men who reformed the country.

- American Revolution: Principles and Consequences One expanded the number of lands of the young country due to the confiscation of territories that were under the possession of the English government and loyalists, that is, people supporting the crown.

- The American Revolution’s Goals and Achievements The Patriots’ goals in the War, as well as the achievements of the revolution and the first Constitution in relation to different groups of population will be discussed in this essay.

- Haudenosaunee’s Role in the American Revolution They also signed treaties in relation to the support needed by the Americans and the Indians to avoid the conflicts that arose between the nations.

- Causes and Foundations of the American Revolution Speaking about what led to the revolution in the United States – the Boston Massacre, the Tea Party, or the Stamp Act – the most rational reason seems to be the result of all these […]

- The American Revolution: Role of the French The revolutionary war became the fundamental event in the history of the USA. For this reason, the rebellion in America became a chance to undermine the power of the British Empire and restore the balance […]

- The Unknown American Revolution: Book Review In his book, Gary unveiled that the American Revolution’s chaos was through the power of Native Americans, enslaved people, and African Americans, not the people in power. The book boldly explains the origins of the […]

- Causes of the American Revolution: Proclamation & Declaration Acts The Proclamation was initially well-received among the American colonists because of the emancipation of the land and the cessation of hostilities.

- The American Revolution and Its Leading Causes Two acts passed by the British Parliament on British North America include the Stamp Act and the Townshend Act, which caused the Boston Massacre.

- A Woman’s Role During the American Revolution Doing so, in the opinion of the author, is a form of retribution to the people long gone, the ones who sacrificed their lives in honor of the ideals that, in their lifetime, promised a […]

- The Battles of the American Revolution The initial cause of the battle is the desire of the British to take over the harbors in Massachusetts. The battle of Bunker Hill marked the end of the peaceful rebellions and protests and became […]

- American Revolution’s Domestic and Worldwide Effects The American Revolution was a world war against one of the world’s most powerful empires, Great Britain, and a civil war between the American Patriots and the pro-British Loyalists. The main domestic effects of the […]

- Changes Leading to the Colonies to Work Together During the American Revolution Ideally, the two settlements formed the basis of the significant social, political, and economic differences between the northern and southern colonies in British North America.

- American Revolution: Seven Years War in 1763 As a result of the passing the Tea Act in 1773 British East India company was allowed to sell tea directly to the colonist, by passing the colonists middlemen.

- The History of American Revolution and Slavery At the same time, the elites became wary of indentured servants’ claim to the land. The American colonies were dissatisfied with the Royal Proclamation of 1763 it limited their ability to invade new territories and […]

- The Experience of the American Revolution One of such events was the American Revolution, which lasted from 1775 to 1783; it created the independent country of the United States, changed the lives of thousands of people, and gave them the real […]

- Causes of the American Revolution Whereas we cannot point to one particular action as the real cause of the American Revolution, the war was ignited by the way Great Britain treated the thirteen united colonies in comparison to the treatment […]

- American Revolution Rise: Utopian Views Therefore, the problem is that “the dedication to human liberty and dignity exhibited by the leaders of the American Revolution” was impossible because American society “…developed and maintained a system of labor that denied human […]

- Impact of American Revolution on the French One After the success of the American Revolution, there was a lot of literature both in praise and criticism of the war which found its way to the French people.

- The Leadership in Book ‘Towards an American Revolution’ by J. Fresia It’s an indication of the misuse of the people by the leaders in a bid to bar them from enlightenment and also keep them in manipulative positions.

- American Revolution Information People in the colonies were enslaved in tyranny of churches as well as monarchies, and Benjamin, believed that with proper undertaking of education, the colonies would arise to their freedom and Independence.

- American Revolution: An Impact on the Nation The American Revolution can be characterized as one of the milestone events in American history which led to the formation of the state and the nation.

- Benjamin Franklin and the American Revolution Radical interpretations of the Revolution were refracted through a unique understanding of American society and its location in the imperial community.

- The American Revolution U.S. History But at the end the pride of the English King as well as the desperation of the English monarchy forced the hand of the settlers to draw the sword.

- The American Revolution From 1763 to 1777 In America 1763 marked the end of a seven-year war which was known as the India and French war and also marked the beginning of the strained as well as acrimonious relations between the Americans […]

- The History of American Revolution The American Revolution refers to a period between1763 and 1784 when the events in the 13th American colonies culminated in independence from the British colonial rule.

- American Revolution: Causes and Conservative Movement To ease workplace stress, managers must be able to recognize the effects of stress on employees and to determine the cause.

- Figures of the American Revolution in «The Shoemaker and the Tea Party» The book The Shoemaker and the Tea Party by Alfred Young is a biographical essay describing events of the 18th century and life one of the most prominent figures of the American Revolution, George Robert […]

- The American Revolution Causes: English and American Views The American Revolution was brought about by the transformations in the American government and society. The taxes were not welcome at all since they brought about a lot of losses to the colonies.

- American Revolution and Its Historical Stages The following paragraphs are devoted to the description of the stages that contributed to a rise of the revolution against British rule.

- The American Revolution and Political Legitimacy Evolution At the beginning of the article, the Anderson highlights Forbes magazine comments where they stated that the businesses that would continue to feature in the future Forbes directory are the ones that head the activists’ […]

- American Revolution: Perspective of a Soldier Revolution became the event that radically changed the American society of that period and, at the same time, contributed to its unification.

- American Revolution and the Current Issues: Course The understanding of the critical issues in the history of the American Revolution will make the students intellectually understand the subsequent wars in American History and the events that may occur later.

- American Revolution in the United States’ History Americans had a very strong desire to be free and form their own government that would offer the kind of governance they wanted.

- Vietnam War and American Revolution Comparison Consequently, the presence of these matters explains the linkage of the United States’ war in Vietnam and the American Revolution to Mao’s stages of the insurgency.

- American Revolution in Historical Misrepresentation Narrating the good side of history at the expense of the bad side passes the wrong information to the students of history.

- American Revolution Against British Power They considered the fashions and customs of the British to be the best in the world; they sent their children to London for education, and they were very proud of the constitutional monarchy that governed […]

- The American Revolution as a People’s Revolution An idealized conception of a revolution leads to the conclusion that the American Revolution was not a representation of a “people’s revolution”.

- Battle of Brandywine in the American Revolution The Squad’s mission is to reconnoiter the location of the enemy during the night before the battle and prevent the possible unexpected attack of the enemy by enhancing the Principles of War.

- African Americans in the American Revolution Both the slave masters and the British colonizers sought the help of the African Americans during the American Revolution. The revolutionary nature of the American Revolution did not resonate with both the free and enslaved […]

- Post American Revolution Period: Washington Presidency The formation of the National Government during the years of 1789-1815 was associated with many challenging situations, and it was characterized by the opposition of the Federalists and Republicans, among which the important roles were […]

- American Revolution: Reclaiming Rights and Powers As a result, British Government Pursued policies of the kind embodied in the proclamation of the 1763 and the Quebec act that gave Quebec the right to many Indian lands claimed by the American colonists […]

- Women Status after the American Revolution This revolution enabled women to show men that females could participate in the social life of the society. Clearly, in the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century women were given only […]

- American Revolution of 1774 First of all, one of the main causes of the conflict and the following confrontation between the British power and the colonies was the disagreement about the way these colonies should be treated and viewed.

- Impact of Rebellion on the American Revolution The rebellion was retrogressive to the cause of the American Revolution because it facilitated the spread of the ruling class and further hardened the position of the ruling class regarding the hierarchical arrangement of slavery.

- Liberty! The American Revolution The thirteen colonies were not strangers to the oppressions and intolerable acts of the British parliament. The oppressions of the colonies by the British became a regular occurrence and the people sought a solution.

- Was the American Revolution Really Revolutionary? The nature of the American Revolution is considered to be better understandable relying on the ideas offered by Wood because one of the main purposes which should be achieved are connected with an idea of […]

- The American Struggle for Rights and Equal Treatment To begin with, the Americans had been under the rule of the British for a very long time. On the same note, the British concentrated on taxing various establishments and forgot to read the mood […]

- African American Soldier in American Revolution It was revealed that the blacks were behind the American’s liberation from the British colonial rule, and this was witnessed with Ned Hector’s brevity to salvage his army at the battle of Brandywine.

- The Revolutionary War Changes in American Society The Revolution was started by the breakaway of the 13 American Colonies from the British Crown. A significant consequence of the American Revolution is that it led to the drafting of the Declaration of Independence […]

- American Revolution and the Crisis of the Constitution of the USA In whole, the American people paving the way to independence have to face challenges in the form of restricted provisions of Constitution, wrong interpretation and understanding of the American Revolution, and false representation of conservative […]

- American Revolutionary War: Causes and Outcomes The colonists vehemently objected to all the taxes, and claimed that Parliament had no right to impose taxes on the colonies since the colonists were not represented in the House of Commons.

- Effects of the American Revolution on Society In order for the women to fulfill, the role they needed to be educated first thus the emphasis of education for them in what came to be known as Republican Motherhood. Women faced limitations in […]

- The Ideas of Freedom and Slavery in Relation to the American Revolution Although many Founders discussed the phenomenon of slavery as violating the appeals for freedom and liberty for the Americans, the concepts of slavery and freedom could develop side by side because the Founders did not […]

- French and Indian War, the American Revolution, and the War of 1812 In the course of the war, a peace treaty was signed in 1763 where the Britons acquired most of the territory that belonged to the French.

- The American Revolution and Independence Day Celebration This article will help us understand the American Revolution and determine whether Americans have a reason to celebrate Independency Day every Fourth of July or not, whether all American supported the war, and whether the […]

- American Women and the American Revolution Women’s standing, as much as they, in point of fact, turned out to be narrower and inflexibly defined subsequent to the war, was enhanced.

- Abigail Adams in American Revolution The presidency is a highly celebrated position and in her husband’s capacity, she was elevated to the eyes of the whole nation.

- The American War of Independence The American Revolution denotes the social, political and intellectual developments in the American states, which were characterized by political upheaval and war. The move by the colonizers seemed unpopular to the colonists and a violation […]

- Domestic and Foreign Effects of the American Revolution

- Reasons for English Colonization and American Revolution

- Native Americans During the American Revolution

- The American Revolution: The Most Important Event in Canadian History

- Women’s Rights After the American Revolution

- Philosophical, Economic, Political and Social Causes of the American Revolution

- American Revolution: The Result of Taxation, Military Occupation in the Colonies and the Negligence of the British

- The American Revolution and Women’s Freedom

- Reasons for the American Revolution – Tax, Military Presence, Merca

- Colonial Independence and the American Revolution

- The History, Transformative Quality, and Morality of the American Revolution

- Political and Economic Cause of the American Revolution

- American Revolution and Mexican Independence

- American Revolution: The Result of the French and Indian War

- Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution

- Battles That Changed the Outcome of the American Revolution

- After the American Revolution: Conflicts Between the North and South

- The Reasons Why People Chose to Be Loyalist During the American Revolution

- Identity: American Revolution and Colonies

- The Expansion and Sectionalism of the American Revolution

- The Relationship Between Nova Scotia and the American Revolution

- World Events That Coincided With the American Revolution

- The American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence

- The Republican Ideology and the American Revolution

- The Men Who Started the American Revolution

- Slavery and the American Revolution

- Economic and Political Causes for the American Revolution

- Ideas, Movements, and Leaders in the American Revolution

- American Revolution and the American Civil War

- Cultural Differences, the Ineffectiveness of England’s Colonial Policy, and the Effects of the French and Indian War as the Causes of the American Revolution

- American Democracy, Freedom, and the American Revolution

- Benjamin and William Franklin and the American Revolution

- The Major Factors That Led to the American Revolution

- Labor During the American Revolution

- Finding Stability After the American Revolution

- Autonomy, Responsibility and the American Revolution

- George Washington and the American Revolution

- African Americans and the American Revolution

- British and American Strengths in the American Revolution

- American Revolution and How the Colonists Achieved Victory

- What Was The Catalyst Of The American Revolution?

- Was the American Revolution a Conservative Movement?

- How Inevitable Was the American Revolution?

- Was the American Revolution Inevitable?

- Was the American Civil War and Reconstruction a Second American Revolution?

- How did the French and Indian War shape the American Revolution?

- What Were the Origins of the American Revolution?

- Why Did Tensions Between Great Britain and their North American Colonies Escalate so Quickly in the Wake of the French and Indian War?

- How the American Revolution Changed American Society?

- Was the American Revolution About Freedom and Political Liberty, or Just About Paying Fewer Taxes?

- Why Was American Revolution Unjust?

- How America and Great Britain Benefited from the American Revolution?

- Was The American Revolution A British Loss or An American Victory?

- How Did the American Revolution Impact Concordians, and Americans, not just Physically but Emotionally and Politically?

- Was the American Revolution Moderate or Radical?

- How Radical Was the American Revolution?

- Did the American Revolution Follow the Broad Pattern of Revolutions?

- How Did The American Revolution Affect Slaves And Women?

- How Did the American Revolution Get Started?

- How England Instigated the American Revolution?

- Who Benefited Most from the American Revolution?

- How Did People Contribute to the Political and Grassroots Areas to Gain Support of the American Revolution?

- Was the American Revolution the Fault of the United States or England?

- Was the American Revolution a Genuine Revolution?

- How Did Labor Change After The American Revolution?

- Did The American Revolution Help Spur The French Revolution?

- How Freemasonry Steered the American Revolution and the Revolutionary War?

- How Outrageous Taxation Lead to the American Revolution?

- How American Revolution Affect Natives?

- Is British Oppression: The Cause of the American Revolution?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 27). 149 American Revolution Essay Topics & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/american-revolution-essay-examples/

"149 American Revolution Essay Topics & Examples." IvyPanda , 27 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/american-revolution-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '149 American Revolution Essay Topics & Examples'. 27 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "149 American Revolution Essay Topics & Examples." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/american-revolution-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "149 American Revolution Essay Topics & Examples." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/american-revolution-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "149 American Revolution Essay Topics & Examples." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/american-revolution-essay-examples/.

- US History Topics

- Revolution Essay Topics

- Imperialism Questions

- British Empire Ideas

- Colonialism Essay Ideas

- Social Democracy Essay Titles

- French Revolution Paper Topics

- Globalization Essay Topics

- Industrial Revolution Research Ideas

- Civil Rights Movement Questions

- Industrialization Topics

- Cuban Revolution Ideas

- Revolutionary War Essay Ideas

- American Politics Paper Topics

- Civil War Titles

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Women and politics in the era of the american revolution.

- Sheila L. Skemp Sheila L. Skemp Department of History, The University of Mississippi

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.216

- Published online: 09 June 2016

Historians once assumed that, because women in the era of the American Revolution could not vote and showed very little interest in attaining the franchise, they were essentially apolitical beings. Scholars now recognize that women were actively engaged in the debates that accompanied the movement toward independence, and that after the war many sought a more expansive political role for themselves. Moreover, men welcomed women’s support for the war effort. If they saw women as especially fit for domestic duties, many continued to seek women’s political guidance and help even after the war ended.

Granted, those women who wanted a more active and unmediated relationship to the body politic faced severe legal and ideological obstacles. The common law system of coverture gave married women no control over their bodies or to property, and thus accorded them no formal venue to express their political opinions. Religious convention had it that women, the “weaker sex,” were the authors of original sin. The ideology associated with “republicanism” argued that the attributes of independence, self-reliance, physical strength, and bravery were exclusively masculine virtues. Many observers characterized women as essentially selfish and frivolous creatures who hungered after luxuries and could not contain their carnal appetites. Nevertheless, some women carved out political roles for themselves.

In the lead up to the war, many women played active, even essential roles in various non-consumption movements, promising to refrain from purchasing English goods, and attacking those merchants who refused to boycott prohibited goods. Some took to the streets, participating in riots that periodically disturbed the tranquility of colonial cities. A few published plays and poems proclaiming their patriotic views. Those women, who would become loyalists, were also active, never reluctant, to express their disapproval of the protest movement.

During the war, many women demonstrated their loyalty to the patriot cause by shouldering the burdens of absent husbands. They managed farms and businesses. First in Philadelphia, and then in other cities, women went from door to door collecting money for the Continental Army. Some accompanied husbands to the battlefront, where they tended to the material needs of soldiers. A very few disguised themselves as men and joined the army, exposing as a lie the notion that only men had the capacity to sacrifice their lives for the good of the country. Loyalist women continued to express their political views, even though doing so brought them little more than physical suffering and emotional pain. African American women took advantage of wartime chaos to run away from their masters and forge new, independent lives for themselves.

After the war, women marched in parades, lobbied and petitioned legislators, attended sessions of Congress, and participated in political rallies—lending their support to particular candidates or factions. Elite women published novels, poems, and plays. Some hosted salons where men and women gathered to discuss political issues. In New Jersey, single property-owning women voted.

By the end of the century, however, proponents of women’s political rights lost ground, in part because new “scientific” notions of gender difference prepared the way for the concept of “separate spheres.” Politics became more organized, leaving little room for women to express their views “out of doors,” even as judges and legislators defined women as naturally dependent. Still, white, middle class women in particular took advantage of better educational opportunities, finding ways to influence the public sphere without demanding formal political rights. They read, wrote, and organized benevolent societies, laying the groundwork for the antebellum reform movements of the mid-19th century.

- American Revolution

- Deborah Sampson

- republicanism

- Abigail Adams

- Mercy Otis Warren

- citizenship

- Mary Wollstonecraft

The Meaning of Political Activity

Until recently, historians equated political activity with the right to vote, and thus characterized American women as having no political voice until the mid-19th century, when a few brave souls demanded (among other things) the franchise. Politics, citizenship, and voting were so linked in the minds of then modern Americans that few imagined disfranchised women as political actors. The Declaration of Independence may have proclaimed that “all men are created equal,” but few scholars suggested that women believed Jefferson’s soaring rhetoric applied to them. Beginning in the 1980s, however, historians began to re-examine their understanding of what it meant to be a political person, or, in the era of the American Revolution, to be a patriot or a loyalist. Instead of simply assuming that views of political activity were the same in the 18th century as they are modern times, scholars looked at the past anew, defining political activity within a distinctly historical context. The results of that endeavor—which remain open ended and contested—introduced historians to a world that was profoundly different from their own.

No one denies that women before, during, and after the Revolution faced severe limits to their ability to act as political beings. Nor does anyone deny that even the most self-consciously public-spirited women defined their relationship to the state in ways that differed from the experiences of men. Indeed, white women were actually losing political power throughout the 18th century. In the 17th century, social standing, not gender identity, was the key determinant for the distribution of political rights. In England, under certain circumstances, aristocratic women could vote and hold office. In America, no one questioned the right of an elite woman to express her opinions on political issues and to exercise authority over lower class men. By the 18th century, gender had become more important than status. Any woman, however well born, was deemed “naturally” unfit for the public or political realm. In virtually every arena, women, simply by virtue of their sex, were excluded from formal—and even informal—political activity. 1

Legally, married women were enmeshed in the system of “coverture,” a common law doctrine that denied them any independent civic identity. The husband represented his wife to the outside world. He controlled her work and her body, made all political decisions, and controlled any property his wife brought to the marriage. Because the ownership of property was the prime requisite for political rights at the time, if a woman had no property, she had no political existence. A wife’s loyalty was to her husband, not to the state. He might exercise his power with a light hand, discussing politics with his wife and even listening to her views, but the decision to do so was his alone. Legally speaking, at least, women had only one right, the right to choose a spouse. Having “freely” made that choice, they were subject to the benevolence of their husbands.

It was not the law alone that relegated white women—even if they were single—to a non-political status. Convention questioned women’s ability to participate in the political process on a variety of fronts. Many continued to use the story of Eve to prove that women were enslaved to their passions and their sexual desires. They were fickle and frivolous, and above all irrational, and thus not suited to make the decisions that a healthy polity required. “Republican” ideology emphasized propertied independence, self-reliance, physical strength, and bravery—all framed as manly characteristics, as “virtue”—as the essential requisites for political rights. At least some men could sacrifice their own interests to support the public good. But virtually all women, many insisted, “naturally” spent too much on luxuries, driving their husbands into debt, and weakening the entire social fabric. How then could women call themselves patriots if they were too weak to resist their penchant for luxuries, even when the national interest demanded it?

The evidence nevertheless indicates that, despite the limitations they faced, women seldom ignored the political issues of the day. This was especially true in the era of the American Revolution. But in what ways were women “political”? In what sorts of political activities did they engage? What activities remained closed to them? What, if anything, changed? Did women’s understanding of their relationship to the state alter in some fundamental way as a result of a movement founded upon profoundly egalitarian principles?

Clearly the answers to those questions vary. Elite, white women (like their male counterparts) were more likely to reap the benefits of revolutionary change than were lower class white or African American women, especially in terms of their ability to influence the male political world. Urban women had more options than their counterparts in rural America. Quakers accorded women more authority than did other denominations. New England women were, as a whole, more literate and had more access to education than did their southern sisters.

Scholars who focus on women’s formal political activity have good reason to argue that the American Revolution did not alter women’s roles in any meaningful way. The vast majority still could not vote. Those few who were enfranchised quickly lost that right. Nor were women able to hold political office, even at the local level. Nevertheless, they were never divorced from the world outside the home, and they often expressed their views publicly. Even post-war women who had no interest in politics defined themselves as members of the republic, as rights-bearing citizens who were proud to be patriotic actors.

It is possible, moreover, to broaden the definition of “the political,” to view the social and sexual in political terms. If, as one scholar argues, “the family, in its patriarchal structure and values is a microcosmic representation of ‘the state’,” domestic concerns are the purview of political historians. 2 Women applied revolutionary rhetoric to their own circumstances. Some declared their independence from abusive husbands, pursuing their own versions of happiness. Others took control of their bodies, limiting the number of children they brought into the world. White, middle class girls attended the growing number of female academies, asserting that they were rational beings who were able to make reasoned political decisions. They read, they wrote, they published, they formed literary societies, improving their own lives as well as the lives of less fortunate members of society. Elite women hosted salons where they discussed the political issues of the day, creating a sociable environment that softened the rough edges of cantankerous politicians. If, as feminists in the 1970s argued, “the personal is political,” then these women were acting politically. Whether they cared about “high” politics, saw themselves as “republican mothers or wives,” laid claim to “domestic citizenship” or membership in “civil society,” these women’s lives were profoundly affected by the American Revolution. 3

The Coming of the Revolution

Men and women alike were engaged in the debate over America’s relationship to England in the decade preceding the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Colonial women surely cared about public affairs. They had opinions about the Great Awakening, the French and Indian War, and the political quarrels that erupted over local issues in individual provinces. They were interested, as wives, mothers, daughters, even as humans, in the world outside the home. But this time it was somewhat different. This time, a political structure controlled by men appealed directly to women for support, giving them a role to play in the drama that led to the American Revolution. Some women supported the protest movements that led ultimately to independence. Others opposed those same movements, remaining loyal to the King, fearing the chaos and disruption they believed would result if the ties binding the Empire together were broken. In either case, many women were becoming engaged in the public issues of the day.

Granted, nothing in the run-up to independence altered women’s political, social, or legal status. Nevertheless, once colonial leaders decided to employ non-consumption as the best device for securing their ends, they realized that they needed women’s support. Women made most household purchases. Thus they had to be persuaded to refrain from indulging in English luxury items and depend instead on their own spinning and weaving to produce homespun for their families. They would not, of course, engage in formal political activity, but the choices they made in the domestic realm would, by definition, become political.

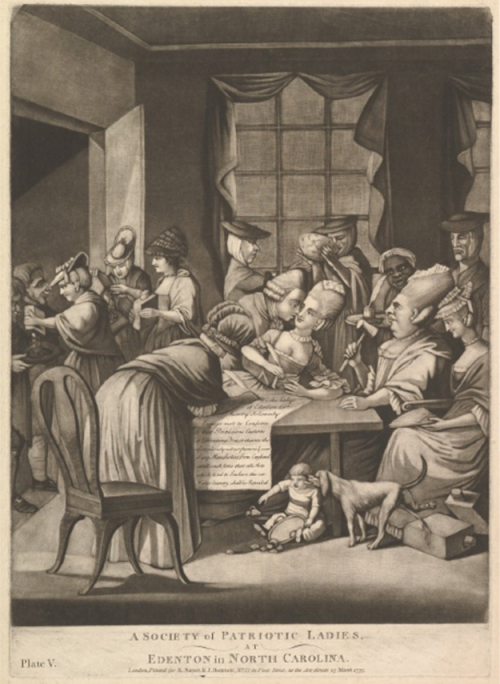

Women responded to the challenge. Especially in New England, those who supported the protest movement gathered in public to take part in spinning bees, proudly exhibiting their womanly talents, feeling, as one young participant noted, “Nationly” into the bargain. 4 Throughout the colonies, women of every social status signed non-consumption agreements. In 1774 , fifty-one women in Edenton, North Carolina went even further, signing such an agreement, specifically claiming to do so in the name of the public good, thus declaring that they understood and cared about the implications of the political debates swirling about them.

Single women acted still more forcefully. In 1765 , five Philadelphia women shopkeepers signed a non-importation agreement, signaling their opposition to the Stamp Act. As single property owners they were legally able to act politically—not as producers of cloth or consumers of manufactured goods, but as members of the mercantile community. A few already had some political authority. If none could vote at the colony level, in Philadelphia, they were “freemen,” who could help elect council members. They also could lobby lawmakers and could sign the same petitions and make the same political decisions made by their male counterparts. 5

Other women, perhaps more circumspect, perhaps simply putting their talents to good use, entered the public realm by becoming a part of the republic of letters. Quaker poet Hannah Griffits supported the boycott in defiance of the Townshend Duties in 1768 , saying,

And tho’ we’ve no Voice, but a negative here, The use of the Taxables, let us forbear, Then Merchants import till yr. Traffick be dull, Stand firmly resolved bid Grenville to see That rather than Freedom, we’ll part with our Tea. 6

Women might not be able to vote, but they did have a “negative.” And they could use it whenever merchants refused to do their patriotic duty.

Mercy Otis Warren, sister of James Otis and wife of James Warren, also picked up her pen to support the patriot cause. Her first published play, The Adulateur , ( 1772 ) viciously attacked Massachusetts’s governor, Thomas Hutchinson, portraying him as a tyrant bent upon destroying the liberties of innocent Americans. The play urged colonists to be on their guard against a leader who would stop at nothing to achieve his ends.

Not every woman signed a petition, wrote a poem, or spun cloth for the good of the “nation.” Even those women who did express themselves politically did not challenge traditional gender norms. No one denied that a married woman’s obligations were to her family, or demanded the franchise for women. Nevertheless, if many women were—like their male counterparts—indifferent to the issues dividing England and America, many others began to think politically. Some disdained the movement toward independence, refusing to sign non-consumption agreements, defiantly drinking British tea, and declaring their continued loyalty to the Crown. Others made sacrifices for the rights of colonial Americans, even if they did not seem to recognize that their own rights were very limited.

According to Republican ideology, willingness to sacrifice one’s life for the public good proved one’s patriotism. If citizens were to demand rights, they had to perform the duties that accompanied those rights. From this perspective, women were excluded from any claims to citizenship, for no one expected a woman to pick up a musket to fight for the King or to defend American liberties. Nothing divided men from women more than the onset of war. War reinforced gender differences, reminding everyone that the battlefield was a male preserve, an arena in which men risked everything and thereby earned the adulation of their countrymen.

Women, too, made sacrifices throughout the war, but their sacrifices were taken for granted and seldom noticed. They lost husbands and brothers, fathers and sons. They fended for themselves when men left home to fight. White, middle class women, in particular, made ends meet at a time when inflation put the barest necessities out of reach. They struggled to manage family businesses and farms, fending off creditors, disciplining recalcitrant slaves or servants, and making financial decisions. Many floundered, failed, and ended up living off the charity of family or friends. Even those, like Abigail Adams, who discovered a talent for business, longed for a time when life would return to “normal.” 7 Still, at least, some women grew more confident in their ability to handle traditionally male affairs, as they made independent decisions that were every bit as rational as those their husbands would have made.

Many African American women seized upon wartime activity to declare their own independence, running away from their masters, fleeing either to the British army, to Canada, or to American cities where they could blend in with the free black population. They were clearly taken by the language of liberty and equality that white patriots used in their fight against the British, using that language for their own purposes. Phillis Wheatley, an African American slave from Massachusetts, published poems that explicitly used white Americans’ demands for their own liberty to challenge the institution of slavery.

Women took an active part in the Revolutionary struggle, whether they wanted to or not. A war fought in America, where the lines between the “battlefront” and the “home front” were blurred or non-existent, disrupted the lives of many women at one time or another. Some, especially those who lived along the coast, fled to the interior, where they hoped to be safe from marauding Redcoats. Benjamin Franklin’s sister, Jane Mecom, was one of thousands of women who abandoned Boston in 1775 , living a peripatetic existence for years as she sought refuge from the ravages of war. 8 Others did not, or could not, leave their homes. South Carolina’s Eliza Wilkinson, for example, endured more than one “day of terror” at the hands of British soldiers who entered her home, confiscated her clothes and her jewelry, and implicitly threatened her life. 9 Loyalist women endured even more traumatic hardships because of their political views. Ostracized by their neighbors, they watched as the families’ property was confiscated by the state, and they were often forced into exile.

Some white women, especially those of lower status, had little choice but to accompany their husbands to the battlefront, where their services to the Army were invaluable. They washed clothes and bedding, cooked and sewed, tended to the sick and wounded, and occasionally picked up a musket and fired at the enemy. 10 These women never won much praise, even when they put their lives in danger, challenging the assumption that men were brave and public spirited, while women were weak and selfish.

Women usually performed their patriotic duties as wives and mothers. Few, even those who accompanied their husbands to war, abandoned their domestic role. Some, however, took a more active and less “womanly” approach. In 1780 , for instance, Esther DeBerdt Reed of Philadelphia published a broadside, The Sentiments of an American Woman , to argue that America’s female patriots should act as citizens, not simply as women, in the service of their country. She urged women to sell their jewels and ornaments and to donate the proceeds to the Continental Army. Thirty-six Philadelphia women—all elite—responded. Not only did they sell their own luxury items, but they also went door-to-door, collecting money from strangers and friends, from rich and poor. Such “unfeminine” activity was shocking to some, admired by others. In Philadelphia alone, they amassed over $7,000 in specie. Significantly, the Philadelphia women organized their counterparts in other cities, proving that women were capable of unmediated patriotism.

Women were also spies, often employing gender stereotypes to their own ends, convincing the enemy that a “mere woman” knew nothing about war or politics. A few defied gender conventions altogether, joining the Continental Army disguised as men. None was more successful in this regard than Deborah Sampson, who enlisted after the Battle of Yorktown and kept her identity secret for seventeen months. The response to the revelation that “Robert Shurtliff” was indeed Deborah Sampson is revealing. The New York Gazette praised Sampson for her “virtue” as a “ female soldier ,” emphasizing her “chastity,” her aversion to liquor, and her patriotism. Apparently a woman could be a “patriot” even as she maintained her purity and gentility. In fact, Sampson probably enlisted so that she could get the bounty offered to all volunteers. Still, if some observers believed that a woman was capable of military virtue, they were implicitly admitting that the lines dividing humans along gender lines were becoming blurred. 11

Women of the Republic

At war’s end, Americans faced a world where, at least temporarily, the old verities seemed open to question. The traditional order did not collapse. Racial slavery survived the Revolution, even if it began to disappear in some parts of the country. Men with no property remained disenfranchised, although the link between property and the vote was becoming obsolete. Some Americans began to question traditional definitions of gender, participating in a transatlantic conversation about gender identities and roles, as they wondered how Americans could justify the legal, economic, and social dependence of women in a nation founded upon the premise of equality. Granted, none of the men who signed the Declaration of Independence intended to relinquish their domestic authority, nor did they envision a world where women would be truly equal or independent. Still, arguments about women’s political rights filled the air. Now that the new nation was composed of citizens instead of subjects, some questioned the relationship of white women to the state. Could women be citizens? And if so, did they experience citizenship in the same way that men did? The answers to those questions varied, but they did reveal that gender definitions were in flux.

Female Politicians

Many patriot women came out of the Revolution with a sense of worth and political importance. They had been praised for their patriotism in the days leading up to the war; they had sacrificed for the cause. Some had run businesses, operated farms, and taken care of their families, proving that they need not be dependent upon their husbands. They had followed the political debates before and during the war, and continued to do so at war’s end. Thus they could be excused for assuming that they were citizens who might not be equal to or the same as men, but who nevertheless had some political rights.

Nor did all men disagree. Men praised women for their loyalty. A few even admitted that there was no rationale for excluding property-owning women from the vote. Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee, for instance, had no answer to his widowed sister when she complained that she was being taxed without representation. While he thought women did not really need to vote, he promised he “would at any time give my consent to establish their right” to do so. 12 In New Jersey, single women worth fifty pounds actually voted between 1776 and 1807 . Some scholars argue that the decision to enfranchise women was neither an accident nor an anomaly. Rather, they insist, New Jersey “simply stood at the cutting edge of the political continuum, and its laws represented the furthest reach of possibilities for female citizenship,” taking “Revolutionary doctrine to its furthest—but logical—extreme, at least for white women.” 13 The state’s lawmakers accepted the implications of revolutionary rhetoric, welcoming white, property-owning women into the body politic, even courting them at election time. They withdrew their support only when the men in power began to see women’s votes as a liability rather than an asset.

If most women did not vote, few saw women’s exclusion from the franchise in exclusively gendered terms. Many white men, even those who had served in the Continental Army, did not meet the property qualifications for voting. Increasingly, however, with the expansion of the franchise to all white men, it became apparent that women could not vote simply because they were women. Even single, property-owning women were seen as dependents at a time when independence was accorded the highest value, and dependence was framed in pejorative terms. 14

That never meant that women were not citizens. The Constitution made it clear that, while slaves were only three fifths of a person, white women were fully counted in the census, thus helping determine how many representatives each state would have in Congress. As one historian points out, “In some clear, if unspecified way, women were members of political society in ways that slaves simply were not.” 15 Women, moreover, expected to enjoy many of the same rights as men. They were not excluded from the protections offered by the Bill of Rights, and they assumed that their property was protected under the law.

Post-war women were not simply passive recipients of the government’s protection. They expressed their views on the political issues of the day in a variety of ways. Lower class women could be found in the streets, participating in celebratory rituals that gave patriotic meaning to their connection to the new nation. They marched in parades, attended public festivals, and marked election days with demonstrations for their favorite candidates. Independence Day commemorations were especially inclusive. Many towns even called upon women to make speeches to “promiscuous” audiences in honor of the nation’s birthday. 16

Women of the middling sort and the elite also participated in these celebrations. Others performed their political roles more circumspectly, remaining at home, but imbuing their ordinary domestic duties with political meaning. Some saw themselves as “republican mothers,” who raised their sons to be virtuous citizens, thus doing their part to keep the new nation from sliding into decay. 17 Others emphasized their roles as “republican wives,” whose influence on their husbands was essential to the survival of the republic. 18 In either case, women used their newfound importance to demand more and better education for their daughters. Young women throughout the country attended the growing number of women’s academies, gaining confidence in their ability to think rationally and to express their opinions on public affairs.

Some elite women were political actors in more rarified ways. If they lived close to the center of government—in New York, Philadelphia, or ultimately in Washington City—they hosted or attended salons, where men and women gathered to discuss political issues. Martha Washington held regular levees in New York, serving as a broker between formal politics and the domestic realm. New Jersey’s Annis Boudinot Stockton and Philadelphia’s Anne Willing Bingham were only two of those women who helped bridge the division between public and private, providing an informal setting for political conversations. Their contributions were accepted because women emphasized their traditionally feminine attributes as sociable human beings who were adept at cultivating civility and reforming the manners of the men who in fact ruled the world. Moreover, they could “speak to power, but they could not exercise it.” 19 Still, they saw themselves as political beings. In Washington, they attended sessions of Congress and arguments before the Supreme Court. 20 To be sure, they mattered only because of their relationships to powerful men. They were simply engaged in the “family business—in this case, however, the family business was politics.” 21 Some, like Margaret Bayard Smith, privately resented the “‘limited circle which it is prescribed for women to tread’” and longed for the “‘unlimited sphere of man.’” Even if women did not demand the vote, many envisioned an active role for themselves in the new republic. 22

Women of Letters

Some women used their pens to directly challenge the gender conventions of the day. In their own minds, they were acting politically, even as they maintained their respectability. They wrote in the privacy of their own homes, yet they were part of the “public sphere,” that fictive space between the formal world of politics and the domestic realm. They were disembodied voices speaking to a disembodied audience. Actress, novelist, and playwright Susanna Rowson was a partial exception to that rule. Not only did she write plays extolling women’s virtues, but she also appeared on stage, forthrightly exhibiting her sexualized body to the audience. At the conclusion of her play, Slaves in Algiers , she stood before the audience proclaiming:

Women were born for universal sway; Men to adore, be silent, and obey. 23

Most women writers were not so bold—or so desperate to make money. They carefully guarded their reputations, even as they argued that women were reasonable creatures who had a political role. Many combed the history books, seeking examples of political women in the past, to make their case. They often wrote about queens, not because they saw monarchs as representative women, but because queens provided examples of real women who had successfully exercised political power. They studied educated women for the same reason, pointing out that women could be as rational and erudite as any man. They looked, above all, to the classics—especially to the Roman Empire, for examples of women who were both virtuous and patriotic. They extolled the “Roman Matron” who influenced public events through connections to their husbands. They admired the women of Sparta, who bore strong sons and prepared them for the battlefield. 24

Massachusetts’s Judith Sargent Murray was especially adept at using history to support the argument for women’s political rights. Proud to proclaim her affinity for English feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, Murray was at the forefront of those who claimed that women were intellectually equal to men. In “Observations on Female Abilities,” which appeared in her three-volume “miscellany” The Gleaner ( 1798 ), she argued that women were naturally rational, intelligent, brave, and patriotic. History proved, she insisted, that women were capable of leading armies, ruling kingdoms, and contributing to the intellectual life of the nation. If they failed to do so, their environment, not their nature, was at fault. According to Murray, women were “circumscribed in their education within very narrow limits, and constantly depressed by their occupations.” She insisted, “ The idea of the incapability of women is, we conceive, in this enlightened age , totally inadmissible .” Given half a chance, she cried, the “daughters of Columbia” could soar to the loftiest heights. 25

Even Murray pulled her punches. She never asked for the vote. Although she longed to be taken seriously, she desired influence, not power. Consequently, while she argued that women could hold office or lead armies, she did not believe they should do so, unless they had no other choice. Nevertheless, she made a case for women’s political abilities that could probably not have been made in pre-Revolutionary America.

Murray’s argument was based on her belief that men and women were essentially the same, at least where important (intellectual) matters were concerned. She claimed that “the mind has no sex,” and thus she sought to blur gender differences. Mercy Otis Warren, who published her History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution in 1805 , justified her entry into the republic of letters on quite different grounds. She did not deny that women were different from men. Rather, she argued that because women were different they had a “valuable perspective” on political matters that the new nation would ignore at its peril. Women, she said were especially religious and morally perceptive, nor were they so wedded to military values as men were. Women, in essence, could be political because of their unique characteristics, not in spite of them. In essence, Warren was helping to prepare the way for the notion of “separate spheres.” 26

Toward Separate Spheres

Judith Sargent Murray was by no means the only person in the late 18th century—male or female—who thought that men and women were intellectually alike. Few challenged coverture directly, but neither did many people automatically dismiss the notion that women could be patriotic citizens with views of their own. Nevertheless, fears of “disorderly women” always lurked just beneath the surface. The French Revolution exacerbated those fears, leading many on both sides of the Atlantic, to adopt the language of a new scientific discourse linking women’s bodily and emotional traits. They argued that men and women were not only different, but opposites. Because women were naturally—essentially—weak, emotional, and irrational, they belonged in the home. Their involvement in the increasingly vituperative and dirty business of politics would undermine the nation. While some argued that women remained equal, even if they occupied a separate sphere, others sensed that the egalitarian promise of the Revolution was disappearing. 27

Mary Wollstonecraft’s fall from grace was both a symptom and a cause of the growing hostility toward women’s political rights. Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman ( 1792 ) received a largely positive response when it first appeared on American bookshelves. Not everyone viewed the work with approbation, but many women saw Wollstonecraft as a kindred spirit. All that changed in 1798 . Wollstonecraft died in childbirth, and her husband, William Godwin, rushed his Memoirs , a tribute to his wife, into print. Godwin described Wollstonecraft’s three-year affair with Gilbert Imlay, portraying his wife as a passionate being who followed her heart rather than submitting to the strictures of convention. Overnight, Wollstonecraft’s detractors used her story as proof of the dangers of what passed for feminism in the 18th century. The equality of women, which had once been open to debate, was now characterized as “unnatural.”

Less than ten years later, New Jersey women lost their right to vote. If the actual motive for that loss had everything to do with partisan politics, the rationale for the decision partook of the rhetoric of gender difference. Thus, men argued that even single, property-owning women, were, by definition, “persons who do not even pretend to any judgment.” The mere idea of women voting, said one New Jersey observer, was “disgusting” and contrary to “the nature of things.” 28

Courts throughout the nation reinforced the notion that all women were dependents, incapable of making their own political decisions. In Massachusetts, James Martin appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court, demanding the return of properties confiscated from his mother’s estate. Anna, James’s mother, had married a British soldier, and had accompanied him when he fled to New York during the war. The state viewed husband and wife as loyalists, and confiscated their property. Throughout the war, political leaders had told women to act politically, even to “rebel” against their husbands if those husbands chose the “wrong” side. They had assumed, in other words, that women had an independent voice and could—indeed should—use that voice to support the Revolution. In 1801 , the Massachusetts court decided differently. It maintained that a wife had no choice but to follow her husband’s wishes. Indeed, for a woman to rebel against her husband would be unnatural, and destructive of all social order. Women, claimed Judge Theodore Sedgewick, had no political relationship to the state. In effect, the court “chose common law over natural law,” indicating that the doctrine of coverture had survived the Revolution unscathed. 29

Everywhere the signs of a backlash against women’s political activity became apparent. In Philadelphia, sexual behavior that had once been tolerated became criminalized and racialized. 30 Also in Philadelphia, single, property-owning women were increasingly viewed as anomalous—even though their numbers actually increased. Tax officials “wrote women out of the polity,” either assessing them at lower rates than they should have paid, or excusing them altogether. 31 When Congress passed the Embargo Act during the Jefferson administration, and Americans were once again urged to forego English goods, no one asked women to spin, to weave, to be good patriots. The Embargo act was controversial, but the controversy was played out in a male political arena. Women’s views were irrelevant. Only the opinions of men mattered. 32 As politics became more organized, politicians had less need to turn to the “people out of doors,” where men and women could make their views known in informal and porous settings, thus closing off yet another venue for women to express their opinions. Ironically, the more white men’s power expanded, the more egalitarian male society became, and the more white women were marginalized. As Andrew Cayton points out, white men, often as not, used their power “to deny citizenship to millions on the basis of an essential identity created by the nature of their bodies. An American citizen in the early republic was a white man remarkably uninterested in the liberty of anyone but himself.” 33

Granted, as some historians have pointed out, women continued to be interested in the world outside the home. White, middle class women organized same-sex benevolent clubs and literary societies, employing their skills to improve society without venturing into the formal political arena. If they generally exercised their power over other women—the poor, the orphaned, the sexually deviant—they were nevertheless preparing the way for the reform movements of the antebellum era. 34 If the premise of the Revolution was not realized for women, neither did it go completely unfulfilled.

Discussion of the Literature

Until 1980 , historians generally viewed early American women as apolitical. Women did not vote (everyone ignored the single women of New Jersey who briefly exercised the franchise), and thus they had no political rights. Two path-breaking books, Mary Beth Norton’s Liberty’s Daughters and Linda Kerber’s Women of the Republic laid that perspective to rest. Norton documented the many ways that women engaged in political debates throughout the Revolutionary era. Less optimistically, Kerber emphasized the challenges that women continued to face, even as she pointed out that the Revolution did lead some to struggle with the contradiction between the Revolution’s egalitarian ideals and the reality of women’s lives. Since 1980 , historians have mined the sources, examining women’s political engagement during the last half of the 18th century.

Some historians remain skeptical about claims that the Revolution fundamentally changed women’s lives. Joan Hoff Wilson insists that women were actually worse off after the Revolution, and that the decline in women’s economic and political position was not a direct result of the Revolution, but rather the consequence of trends long in the making. Women, she claims, were so far removed from political affairs, so lacking in anything approaching a consciousness of themselves as women, that for them, the Revolution was simply irrelevant. A few asked for privileges, not rights. Even they “could not conceive of a society whose standards were not set by male, patriarchal institutions.” 35 Elaine Foreman Crane points out that demands for women’s educational opportunities, and notions of “republican motherhood” and “companionate marriage” had intellectual roots stretching back to the 17th century and beyond. 36 Joan Gundersen argues that women declined in political importance after the Revolution. Before the war, “dependence” was the lot of virtually everyone—men as well as women. After the war, however, independence took on a new importance, while dependence acquired a pejorative, and gendered meaning. 37 Laurel Thatcher Ulrich maintains that those New England spinning bees that made one young woman feel “Nationly” were often conducted to support churches and ministers, not the non-importation movements. 38

Nevertheless, other historians continue to emphasize the way in which the Revolution allowed women a political voice they had not previously enjoyed. They have approached the subject in two general ways. Some have emphasized the explicitly political, even partisan, role women embraced after the Revolution. Rosemarie Zagarri has spearheaded that approach, offering compelling evidence that women imbibed the “rights talk” pervading America in the wake of the Revolution. 39

Alternatively, scholars have taken their cue from Jurgen Habermas—significantly modifying his original analysis—pointing to new ways to look at women’s political activities. 40 They talk in terms of a “public sphere” that was neither formally political nor exclusively domestic. In particular, they have analyzed the world of print and the creation of a salon culture in terms of the ways in which at least some—white, elite—women behaved politically without transgressing the strictures of gentility. Arguing that a “republican court,” similar to the salon culture of late 18th-century France, existed in post-Revolutionary America, historians such as David S. Shields and Fredrika J. Teute have led the way in blurring the lines between public and private, political and domestic in the New Republic. 41

While historians have advanced the study of early American women in ways that scholars in the early 1980s could scarcely have imagined, much remains to be done. A cursory glance at the biographies of individual women says a great deal in this regard. These monographs have focused on elite, white, women. Very few historians have analyzed the experiences of “ordinary” women. Alfred F. Young’s story of Deborah Sampson, Ulrich’s depiction of Martha Ballard, and David Waldstreicher’s study of African American poet Phillis Wheatley are fine exceptions to this rule. 42 Significantly, these historians do not focus directly on the relationship between gender and the Revolution. Sampson is more interested in monetary reward than politics or patriotism. Martha Ballard seems to ignore politics altogether. Wheatley’s focus is on the institution of slavery rather than on women’s rights.

Nevertheless, these monographs indicate that it is possible to bring the lives of lower class and minority women into the political narrative. Young’s brief comments in his “Afterward” to Beyond the Revolution offer historians an excellent place to start. 43 Susan Klepp and Clare Lyons have mapped out an alternative approach, expanding the meaning of the political for ordinary women. They suggest that women’s willingness to divorce their husbands, bear fewer children, and challenge patriarchy in any way expressed a new political consciousness that can be traced to the egalitarian rhetoric of the Revolution. 44

Further exploring the meaning of the “political,” expanding the purview of historical debate beyond white, elite women, and linking the Revolution explicitly to changes in women’s lives in the late 18th and early 19th centuries remain to be done.

Primary Sources

There are no historical societies or libraries that focus specifically on women’s history. The diligent scholar will have to do a great deal of digging to find useful sources, and will no doubt visit many institutions and go on many fishing expeditions to find the bits and pieces they will need to complete their work. In effect, there are no “must reads” as far as primary sources are concerned. The Massachusetts Historical Society, the American Antiquarian Society, the American Philosophical Society, the New York Historical Society, the University of Virginia Library, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and the Library Company are all fine venues, housing a wide variety of sources. Not quite so rich, but nevertheless useful, are historical societies in Virginia, Maryland, and North and South Carolina. Both the Boston Public Library and the New York Public Library have surprisingly useful collections. Scholars interested in social history should consult the court records of each colony or state. The Library of Congress Manuscript Division has numerous relevant collections, as does the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. Scholars focusing on loyalist women should consult the Loyalist Claims files at the National Archives in London. Transcripts are available at the New York Public Library.

For historians interested in literary women, possibilities are quite promising. The post-war period was known for the proliferation of journals, most of them short-lived, some of them actively encouraging women readers and writers. Most can be found on line, or attained on microfilm via interlibrary loan. A by-no-means-exhaustive list would include the Massachusetts Magazine, Gentleman and Lady’s Town and Country Magazine, The Boston Magazine, The New York Magazine , the Port Folio , and the Philadelphia Repository . Early American newspapers also grew exponentially in the post-war era, even though many died after just a few issues. They often included poems and essays that commented—positively or negatively—on women’s political activity. A thorough list of available newspapers can be found on the Library of Congress website, and again, many are available on line.

Educated people in the 18th and 19th centuries wrote letters, and while those letters were often performative, and thus not always “true,” they can be very revealing, nevertheless. Judith Sargent Murray kept copies of most of the letters she sent. The originals are available at the Mississippi Archives, in Jackson, Mississippi. They are also available on microfilm. Other elite women whose private writing is accessible include Mercy Otis Warren, Abigail Adams, Deborah Franklin, and Elizabeth Drinker. The Massachusetts Historical Society holds the originals of the Mercy Otis Warren Papers, which are also available on microfilm. Susanna Rowson’s papers are in the Waller Barrett Library of American Literature, Special Collections, at the University of Virginia Library. Elizabeth Drinker’s Diary is available in a beautifully edited print edition. 45 Virtually all of Abigail Adams’s letters are in print, either in books devoted to Abigail, herself, or in the Adams Papers, available on microfilm at the Massachusetts Historical Society. 46 Similarly, Deborah Franklin’s letters to her husband are in the Franklin Papers . 47

Women also wrote for public consumption. Their novels, in particular, are easily accessible. See in particular, Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple , Hanna Foster’s Coquette , and Tabitha Tenney’s Female Quixotism . 48

Further Reading

- Applewhite, Harriet B. , and Darlene G. Levy , eds. Women and Politics in the Age of the Democratic Revolution . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1993.

- Armstrong, Nancy . Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel . New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Bloch, Ruth H. “The Gendered Meanings of Virtue in Revolutionary America.” Signs 13 (1987): 37–58.

- Buel, Joy Day , and Richard Buel . The Way of Duty: A Woman and her Family in Revolutionary America . New York: Norton, 1984.

- Cayton, Andrew . Love in the Time of the Revolution: Transatlantic Literary Radicalism and Historical Change, 1793–1818 . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Davidson, Cathy N. The Revolution and the Word: The Rise of the Novel in America . New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Davies, Kate . Catherine Macaulay and Mercy Otis Warren: The Revolutionary Atlantic and the Politics of Gender . New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Eastman, Carolyn . A Nation of Speechifiers: Making an American Public after the Revolution . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Good, Cassandra . Founding Friendships: Friendships Between Men and Women in the Early Republic . New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Haulman, Kate . The Politics of Fashion in Eighteenth-Century America . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

- Hicks, Philip . “Portia and Marcia: Female Political Identity and the Historical Imagination, 1770–1800.” William and Mary Quarterly 62.2 (2005): 265–294.

- Juster, Susan . “Disorderly Women”: Sexual Politics and Evangelicalism in Revolutionary New England . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Kerber, Linda K. No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship . New York: Hill and Wang, 1998.

- Kerrison, Catherine . Claiming the Pen: Women and Intellectual Life in the Early American South . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006.

- Lewis, Charlene M. Boyer . Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte: An American Aristocrat in the Early Republic . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

- McMahan, Lucia . The Paradox of Educated Women in the Early American Republic . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012.

- Ousterhout, Anne . The Most Learned Woman in America: A Life of Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson . University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004.

- Rust, Marion . Prodigal Daughters: Susanna Rowson’s Early American Women . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

- Schiebinger, Londa . The Mind Has No Sex? Women in the Origins of Modern Science . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Shields, David S. Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Skemp, Sheila L. First Lady of Letters: Judith Sargent Murray and the Struggle for Female Independence . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

- Smith, Barbara Clark . “Food Rioters and the American Revolution.” William and Mary Quarterly 51.1 (1994): 3–38.

- Smith, Bonnie G. The Gender of History: Men, Women and Historical Practice . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.