Distracted students and stressed teachers: What an American school day looks like post-COVID

Pandemic in rearview, schools are full of challenges – and joy. step inside these classrooms to see their reality..

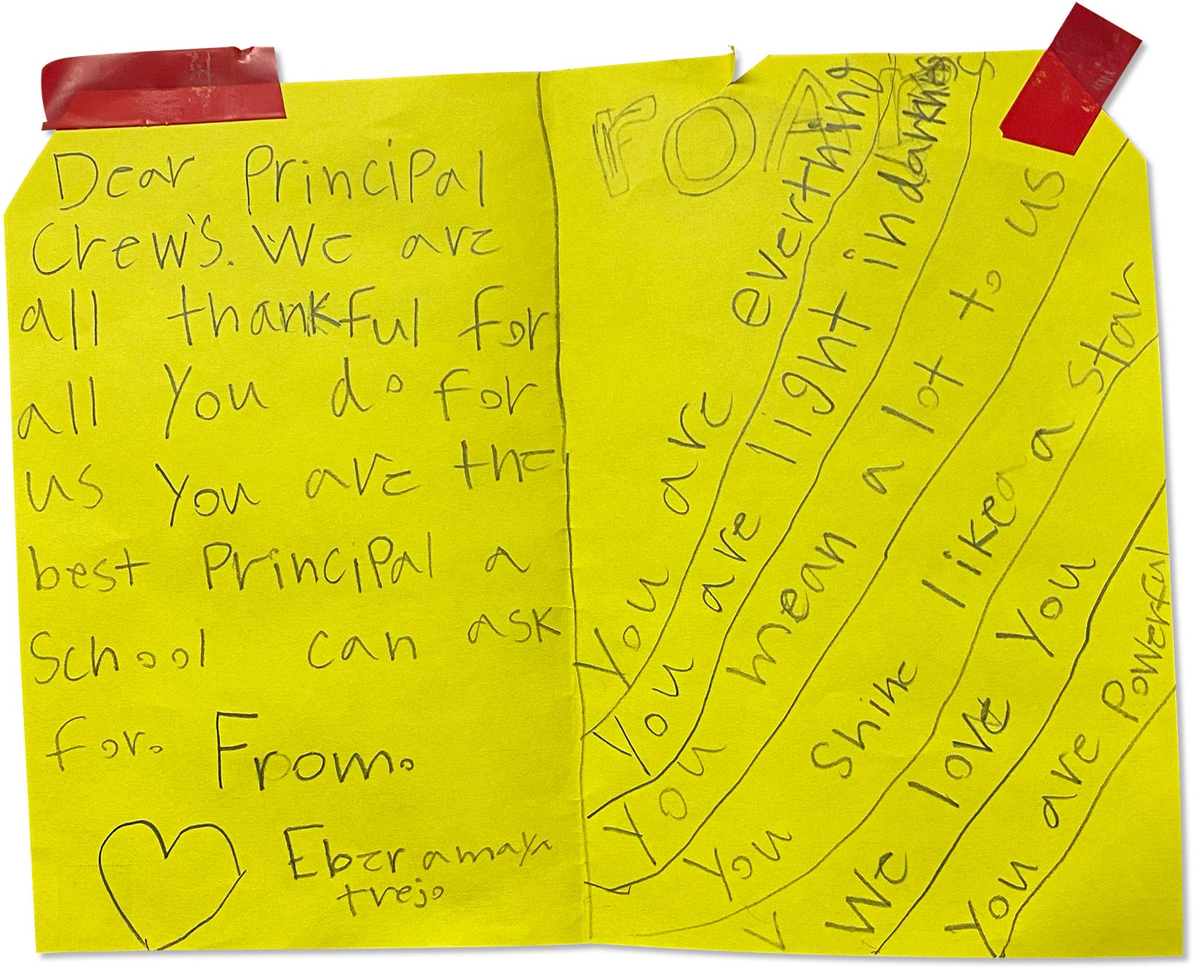

After a day full of math and reading lessons, third grader Ashley Soto struggles to concentrate during a writing exercise. She’s supposed to be crafting an essay on whether schools should serve chocolate milk, but instead she wanders around the classroom. “My brain is about to explode!” she exclaims.

Across the country, fourth grade teacher Rodney LaFleur looks for a student to answer a math question. He reaches into a jar filled with popsicle sticks, each inked with the name of one of his students. The first student’s name he draws is absent. So is the second. And the third.

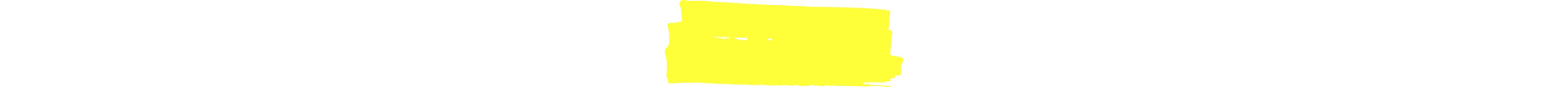

Principal Jasibi Crews goes through her email: She has seven absent employees and too few substitutes to fill in. She texts a plea to a group chat – are any coaches or support staff available to fill in? Dozens of children could be without teachers today if she doesn’t come up with a plan.

![current issues in k12 education April 25, 2023; Alexandria, VA, USA; Ashley Soto, a third grader at Cora Kelly School, observes as another student complete a math problem during after-school instruction Tuesday, April 25, 2023.. Mandatory Credit: Josh Morgan-USA TODAY [Via MerlinFTP Drop]](https://www.gannett-cdn.com/presto/2023/06/01/USAT/d1051995-a8e2-4b67-ac6c-23d6f2d8e49e-ashley_multi.jpg)

These recent moments from public schools thousands of miles apart reveal a troubling fact confronting educators, parents and students: More than three years after the COVID outbreak began, some children are thriving but many others remain severely behind . This reality means recovering from COVID could be more costly, time-consuming and difficult than they anticipated, leaving a generation of young people struggling to catch up.

This isn’t what lawmakers and education leaders had envisioned. Many were hopeful the 2022-23 school year would be the one when things would return to normal – or, at least, closer to what they were like pre-pandemic. Schools were brimming with money to test new ways to accelerate learning and hire more staff. The new hires and the educators who stuck things out were determined to help kids make progress. There was no longer a health emergency.

![current issues in k12 education A student at Downer Elementary in San Pablo, Calif., shares her hopes for the school year: "My goal for this year is to [actually] learn, because I didn't learn last year."](https://www.gannett-cdn.com/presto/2023/06/01/USAT/40d1a38c-3105-4bf9-8b01-8f85c4d58975-CoraKelly_goals.jpg?crop=2329,1840,x0,y247)

USA TODAY education reporters spent six months observing elementary-school students, teachers and principals at four public schools in California and Virginia and asked them to keep journals to better understand the post-COVID education crisis and recovery. Districts in California and Virginia stayed remote for longer than those in many other states. Virginia also had some of the sharpest declines in test scores in the country.

What the reporters observed and data confirms: Kids are missing more class time than before the pandemic because parents’ attitudes about school have changed. Educators encountered students who are severely behind in reading and math yet can hardly sit still after three years of shape-shifting school days. School administrators discovered that a deluge of cash doesn’t go very far in filling jobs too few people are willing to do. Staff shortages and experiments with new curriculum – sometimes intended to cram several years of lessons into one – collided with the everyday problems of many public schools: children and families without enough food or a consistent, safe home life.

To tell this story, USA TODAY reporters cataloged moments they witnessed while visiting schools at different hours and days. What follows is a reconstructed timeline based on reporting that began last fall and an approximation of the challenges schools and students face on any given day.

Teachers find new ways to cope with stress

After rotating through sets of ab saws, leg lifts and battle ropes, a sweaty but grinning Daisy Andonyadis leaves her 6 a.m. high-intensity interval training class early so she can make it to school on time. Equipped with a piece of her mom's homemade Easter bread, Andonyadis – or Ms. A, as students and colleagues call her – is ready to start the school day.

Ms. A, 32, started doing the class more regularly this school year to deal with the stress of teaching. She almost quit when she first started at Cora Kelly School for Math, Science and Technology in Alexandria, Virginia, six years ago, overwhelmed by the pressure to do everything perfectly. “Just being able to breathe – the exercise really helps with that,” she says.

Educators’ mental health has significantly worsened since the onset of the pandemic: Nearly 3 in 4 teachers in a survey last year reported frequent job-related stress, compared with a third of working adults overall. More than a quarter of teachers and principals said they were experiencing symptoms of depression.

Later, now showered and nibbling on her bread, Ms. A kicks off the school day as she always does: with a lesson on social and emotional skills. Kids move magnets with their names on them to emoji-like faces representing different emotions. Each classroom at Cora Kelly has one of these posters, and teachers and kids alike reposition their eponymous magnets throughout the day as their moods change. Today, lots of kids put their magnets on “tired.”

There aren’t enough substitute teachers

Principal Jamie Allardice has many items on his day’s to-do list: preparing for state testing, planning for next school year and attending to the varying needs of school staff.

It will all have to wait.

Like Principal Crews, Allardice has trouble finding substitutes at times. So he’ll be filling in for a kindergarten teacher at Nystrom Elementary School in Richmond, California.

Most of the country’s public schools reported last year that more teachers were absent than before the pandemic, and they couldn’t always find substitutes when needed. The substitute teacher shortage predates COVID – and it’s getting worse, particularly at low-income schools .

Allardice anticipates spending the day teaching the school’s youngest kids how to read sentences like “Is the ant on the fan?” and “Is the fat ant in the tin can?”

Everyday reminders of the pandemic’s effects

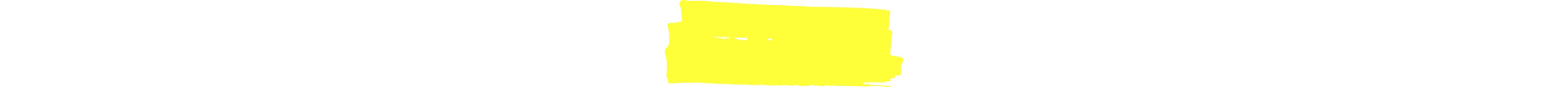

Circles under her eyes, fourth grade teacher Wendy Gonzalez speedwalks into E.M. Downer Elementary in San Pablo, California, ahead of the first bell. The hallways are lined with student work. “My goal for this year is to actully learn,” one sheet reads, with the misspelling, “because I didn’t learn last year.”

Another wall displays photographs Downer sixth graders took during the pandemic as an ever-present reminder of the damage inflicted by the pivot to remote learning. Above pictures of an empty tetherball court, a dog sitting on a stoop and a frog in darkness looking up to light, one student wrote, “We had to go to school at home for about 13 months.”

Ms. G, 45, who has taught for 19 years in the West Contra Costa Unified School District, including three at Downer, is in a hurry to see what condition her class is in after a substitute filled in the two days she was absent last week. She had a ministroke in March, which she blames in part on stress from teaching this year.

In her classroom, her copy of a new Spanish textbook, "Caminos al Conocimiento Esencial,” is on her desk next to a set of Black history flashcards, a San Francisco Giants bobblehead and a can of Sunkist. On top of all the other academic targets her students must meet this year, the principal and literacy coach want her to test new lessons for teaching kids how to read and write in Spanish.

“If I didn’t love my community I would be gone,” says Ms. G says after taking a seat. Notes of thanks and praise are tacked onto a bulletin board next to her.

If I didn’t love my community I would be gone .

Principals have to be ‘there for everyone’

As part of her morning rounds, Principal Crews, 45, stops by a fourth grade classroom in the middle of a lesson on future careers.

She notices a boy’s face is swollen and pulls him to the side. She feels his forehead, asks him if he’s feeling OK, if he was playing out near the poison ivy. He says he was playing there and it feels like a mosquito bit his face. She escorts him to the school nurse.

Crews worked for more than 15 years in Virginia and California schools before becoming principal of Cora Kelly six years ago. She knows every student by name, greeting each one as they arrive at school. She’s also keenly attuned to each child’s individual needs on any given day – whether it’s for clothes or a first-aid kit.

Cora Kelly uses a framework known as a multitiered system of support, which is a fancy way of saying it works to address the core issues, in and out of the classroom, that may be affecting a child’s behavior or academic performance. That can mean home visits if a student misses a lot of school or help from a social worker if a child needs shoes or a screening.

It’s emotionally grueling but gratifying work, Crews says, as is the job of supporting her own staff’s mental health.

“The hardest part of being an administrator has been coming back and making sure (the teachers) were OK so they could be there for the kids,” Crews says. “I wasn’t prepared for the tremendous emotional strain that that’s had on me. I had to be there for everyone, to make sure to take care of them so they could take care of the kids.”’

Rewarding good behavior

Ding. The students in Ms. A’s class are familiar with this chime. It means their teacher has given one of them a point using an app called Class Dojo that tracks their behavior. It has other functions, too, such as managing homework and communicating with parents.

Throughout the day, soft chimes signify when Ms. A has given a student a point. She rewards all kinds of things – being quiet, sitting nicely, getting an answer right, helping a classmate, simply attending. At other times, a different noise erupts when she’s deducting points. Maybe a kid wasn’t listening or following instructions. Maybe two students got into a tiff.

Kids with lots of Dojo points can exchange them for prizes such as a gift card to Chick-fil-a. These incentive systems, Ms. A says, help reinforce the behaviors and habits – from respecting others’ physical space to coming to class on a consistent basis – that many students failed to learn because of remote schooling.

Kids’ attention spans have shrunk

Ashley and her classmates at Cora Kelly are in math class with the other third grade teacher. An assistant is out, the teacher announces, so the kids have to work independently while she consults with small groups.

Today’s lesson is on imperial measuring units for liquids – gallons, quarts, pints, cups – and the teacher says she has a story that will help them memorize valuable information for their upcoming state math tests. The story is called The Kingdom of Gallon, she explains: The kingdom has four queens – in other words, four quarts. Each queen has a prince and a princess – two pints. Each prince or princess has two cats – two cups.

Kids proceed to cut and paste pictures of different items – a gallon of paint, a carton of milk – onto papers with labels for the unit. Many, including Ashley, are distracted. She spins her notebook around a pencil. One of her knees bobbles from left to right. She gets up to tap a pencil on the table, to the projector to wave her hand under the camera. She yawns and plays with her shoe.

Teachers and parents nationwide report kids’ attention spans are even shorter since the pandemic, perhaps in part because it led to unprecedented amounts of screen time among children . Educators strive to make lessons engaging but kids can’t always concentrate, especially when there’s only one adult in the classroom.

Ashley pastes an image of a large water bottle under the wrong label – gallon when it should be quart. She quickly realizes it’s a mistake and tries to unstick the image. Ashley, who in her spare time loves drawing and making jewelry and collecting rocks, is careful to reposition the square so it doesn’t cover the face of a girl displayed on the worksheet.

No multiplication charts allowed

Mr. LaFleur tells the class they'll review skills for a state math exam that will cover multiplying, long division and fractions. Jada Wilson groans when he says they can’t use multiplication charts on the test.

Jada, 10, has improved on fractions and expanded division this year but worries how she’ll do without the aid. She began fourth grade with the skills of a kid halfway through second grade, LaFleur said, but has made up most of that ground.

Jada’s progress is an exception: Other students’ scores moved backward mid-year.

“I really questioned myself and my teaching. It can’t get any worse than that feeling. But it helps to look at students like Jada who’ve grown each time,” LaFleur says.

I really questioned myself and my teaching. It can’t get any worse than that feeling. But it helps to look at students like Jada who’ve grown each time.

Missing class instead of making up for lost time

As Mr. LaFleur’s class begins a reading lesson at Nystrom, several seats are empty. One of them belongs to Jayceon Davis.

Jayceon’s mom, Georgina Medrano, works nights and occasionally gets home at 2 a.m. Sometimes she dozes off after waking her kids, and they don’t make it to school on time. Jayceon said he is sometimes confused doing his homework because he misses the lessons and hasn’t turned much of it in.

For kids who are already behind this school year, every minute of learning this year was critical, but far more for students who missed more school days than before the pandemic. Chronic absenteeism – generally when kids miss more than 10% of the school year – increased in more than 70% of schools nationwide last school year, federal data shows.

Jayceon began the year with low test scores in reading and math, unbeknownst to Medrano, who says she’s frustrated no one told her about it at the beginning of the school year. “He reads to me at home, so I don’t understand how he’s behind,” she says.

Medrano says she also knew nothing about Jayceon’s missing assignments until March, when she got a text from LaFleur, who says he tried several times early in the school year to call Jayceon’s mom about the homework with no success. Then he gave up, hoping she would see notes sent through the school’s online messaging system. She, like many parents this year, didn’t have a real sense of how their kids were doing in school.

Reading, writing and riding

Ashley, like many kids in her class, has never ridden a bike without training wheels. Today in P.E. class, she and the other novices learn on a special bike designed without pedals. The purpose: to learn how to balance.

It takes a while, but before the end of class Ashley, her long curls streaming behind her, manages to glide for 10 seconds without touching her feet to the ground. She graduates to the stationary bike.

She’s thrilled.

It may have nothing to do with phonics or probability or photosynthesis, but this learning matters, too. It’s the kind of lesson that was impossible to replicate during the pandemic, and one that students seem to enjoy most.

Turkeys and monkeys

It’s just before recess and lunch in Ms. A’s class. She issues constant reminders to pay attention and be quiet. Yet some students lie on the ground, chit-chatting. Others make animal noises, gobbling like a turkey and grunting like a monkey.

Ms. A moves her magnet on the classroom’s mood chart to “annoyed.”

Eventually she says to the group: “ I think we need to refresh. Everyone’s a little tired. And it’s Fri-Yay! But we are here to learn.”

One boy sneaks out to get a pack of Gushers candy from his backpack hanging near the classroom door. With a smirk, Ms. A orders him to hand the gummies over, saying she doesn’t want him to get a sugar high.

It’s the kind of thing she’s now able to brush off, a skill she didn’t have as a new teacher. She ignores children who are bickering, keeping her voice gentle and smooth as she delivers instructions.

Despite all the distractions, she successfully engages most of the children in a game that quizzes them on their reading skills.

Phonics time

Gathered at a half-moon-shaped table in the back of Lisa Cay's third grade classroom at Sleepy Hollow Elementary in Falls Church, Virginia, four students sound out rhyming words – search and perch, dead and lead – as they review phonics skills ahead of the state's reading tests. It's one of countless intensive phonics sessions these and other elementary schoolers have had this school year amid a renewed push for a more scientific approach to reading instruction partly in response to learning gaps deepened by the pandemic .

Mrs. Cay, 58, then passes each student a copy of “The Wump World,” about creatures who live on an imaginary planet. One by one, they read aloud with the help of Mrs. Cay, who on a small white board, writes words they stumble over – “broad,” for example, and “chief.” After each passage, she reviews the problem word with them. The room is quiet with the exception of this group’s hushed voices, their peers reading independently elsewhere.

Mrs. Cay hopes the district’s greater emphasis on phonics – and its distancing from an approach that focuses on helping kids dissect a text’s meaning without first showing them how to sound out words – helps boost Sleepy Hollow kids’ literacy. But “it’s going to take a few years” before the effects kick in, Mrs. Cay says. The local school district adopted the new phonics program last school year and started requiring it in the fall.

New educators consider leaving

Seated at his desk at lunchtime underneath a pennant of his alma mater, University of California, Berkeley, LaFleur says it could take some students as many as five years to catch up to where they should be. He expects just a fifth of his own students to pass the state math test. LaFleur, 25, came to Nystrom in the 2020-21 school year through Teach for America, an organization that places recent college grads in high-needs classrooms.

“This is the only normal I’ve ever known,” he said.

But LaFleur recently decided he wants out.

Teacher turnover has increased in recent years: More teachers left their jobs in at least eight states after last school year, and educator turnover was at its highest point this year than in the past five years, data shows.

LaFleur hopes he’ll get the new job for which he’s being considered. Otherwise he will return next year to Nystrom, as he wrote in his journal, to face “the same problems, move through the same cycles, and feel the same feelings.”

‘It’s been a long day’

Principal Crews planned an end-of-day assembly for all of Cora Kelly’s students about simple machines such as wheels, levers and pulleys. Given the day’s nonstop rain, which forced kids to have indoor recess, they’re in need of something fun and to channel their energy. But the traveling troupe scheduled to perform at the assembly is running late.

Whipping out her walkie-talkie, she tells school leaders to prepare to pivot if the troupe doesn’t arrive in time before dismissal. Crews then unzips her black fanny pack – filled with Band-Aids and plastic gloves and Cora Kelly-themed play cash – and pulls out a bottle of Excedrin. Crews takes two. “It’s been a long day,” she says.

Catching up on reading time lost

During a class read along of “Esperanza Rising” for the Spanish portion of Ms. G’s class, students erupt in debate about whether Esperanza’s mother should marry for stability. Valeria Escobedo Martinez, 9, shouts “This is like a telenovela!” The scene reminds her of a TV show she watches at home with her mom, she says.

Even though Valeria says Ms. G’s classroom can be too loud, classroom discussion during reading lessons has helped her make up for reading time she and other kids lost out on during the pandemic.

“I think I’m still leveling up,” she says. Ms. G says “she’s close” to meeting expectations for reading in English and may shed her “English learner” designation next year..

Ms. G is familiar with students who are behind on reading. She spends most school mornings teaching fourth, fifth and sixth graders how to read words using phonics, which is new to Downer this year.

Intervention time

It’s time for Ms. A’s students to break out into small classes – enrichment for students who are advanced and intervention for those who are behind. Ashley and about half a dozen of her peers head to reading intervention class, which she spends laughing along with her peers at the teachers’ jokes, earnestly scanning her dictionary and reciting lines from a passage during a group read-aloud. At one point during the read-aloud, she notices the teacher accidentally skipped a paragraph. The teacher commends Ashley for noticing – what if, she asks, I had skipped a paragraph while taking the state reading test?

Later, as kids independently fill out worksheets, Ashley erects her dictionary as a privacy shield. She doesn’t want others to copy her answers.

Ashley wasn’t always this confident. She needs glasses and while she proudly wears a pair of pink frames now, during the pandemic her vision problems went undiagnosed. Schools usually provide vision screenings but they were one of the services that went away with COVID closures. Her inability to see the screen and understand homework left her feeling frustrated and defiant.

‘Never going back to normal’

Maria Bustos picks up her son Erick from Ms. G’s class. Pre-pandemic, Bustos may have spent the afternoon on Downer’s campus, helping her son’s teachers or planning a school event with fellow parents. Now, lingering pandemic restrictions don’t allow for her to be as active in the school community as she used to be.

“I feel like we're never going to go back to normal – and not just in schools but in everything and everywhere,” Bustos says. “We used to do a Halloween parade, and even celebrate kids' birthdays by bringing pizza."

She is optimistic about being able to volunteer next year, though, given she was able to attend Erick’s music performance on campus at the end of the school year and an in-class party three days before the end of school in Ms. G’s classroom.

I feel like we’re never going to go back to normal – and not just in schools but in everything and everywhere.

Leadership turnover creates further challenges

As the new leader of her school, Ruby Gonzalez, 61, is in the midst of two separate video calls in her office: one about the education plan for a student with disabilities and another that includes other school administrators.

She took over when Downer’s longtime principal, Chris Read, found out he had colon cancer. Read began chemotherapy in March and took a six-month leave to avoid other sickness. After Principal Gonzalez filled in, she tapped Ms. G to take over given her past experience as a vice principal. Ms. G lasted for two days before deciding she didn’t want to abandon her fourth graders. “The kids notice when I’m gone,” she says.

She still helps out often.

Two other substitute principals stepped in months before the end of the school year. One quit after a few days. The other comes a few days a week to help out. It’s unclear who will lead next year. Once Read returns from leave, he will have a new job overseeing visual and performing arts education districtwide, a role he’s long wanted.

Recent data shows that more principals last year quit their jobs than early on in the pandemic.

“This has been one of the most difficult years I think; even more than last year,” Ms. G says. “There’s multiple things: Our principal is out and Ruby’s trying to do the best she can. … And there are new things we're all trying to learn. On top of that there's more work and discipline. The kids are feeling it.”

Not enough time

It’s time for kids in Cora Kelly’s after-school tutoring to be dismissed, but Ashley doesn’t want to leave. She’s eager to master the skill of reading an analog clock. She begs her tutor, the same math teacher she had earlier in the day, to stay longer.

“I love, love, love learning,” Ashley says.

But it turns out her school year is ending earlier than she may have liked, too, much to Principal Crews’ frustration. Ashley and her family will be traveling to her mom’s home country of El Salvador a week before the last day of school. Experts say absenteeism remains widespread in elementary schools, whose students’ attendance relies on their parents’ decisions and schedules.

Giving in to a calculator

Jada is stationed in the school cafeteria trying to solve a multiplication problem while she and her younger sister wait for their mother to pick them up from Nystrom’s after school program. She sighs, leans her face on her fist on the cafeteria table and says, “This is too hard!” A few seconds later, she pulls out a calculator to solve the problem.

Despite her growth this year – end-of-year math tests show Jada jumped from having middle-of-second-grade skills to working at a mid-fourth-grade level – she and many classmates are behind where they should be.

Her mom, Michaela Alexander, rushes into the cafeteria to get the girls. Alexander tells Jada she isn’t too worried she’s behind on math: She understands Jada had a very different experience from a lot of kids in elementary school who learned in a classroom setting uninterrupted by a global pandemic. She has faith that the teachers at Nystrom will help her catch up.

‘She’s better than me’

At her small white trailer in a mobile home park in San Pablo, Valeria, her mom, Maira Martinez Perez, and her grandma, who is visiting from Mexico, sit on separate benches next to each other in a tidy combined living room and kitchen. It’s the same home in which Valeria would pull out her Google Chromebook each morning, log onto school and start the day with jumping jacks to loosen up, as instructed by her teacher, when school shifted online.

Just as Downer pivoted to remote learning, Valeria’s mother lost her job cleaning at another school. Now her mother is working again, and though a kid herself, Valeria has taken on some of the care of her younger sister Itzel. Valeria is sometimes interrupted by the 5-year-old when she tries to read at home.

Itzel peeks out from the only bedroom in the home closed off by a sliding door.

At school, “she’s better than me,” Valeria says of her sister.

No pandemic interrupted Itzel’s schooling.

Story editing by Nirvi Shah

U.S. Government Accountability Office

Back to School for K-12 students: Issues Ahead

As students and teachers head back to the classroom this fall, they are likely to face a number of challenges that could impact the 2022-23 school year and learning outcomes.

We’ve reported on these mounting challenges during the last couple years. Today’s WatchBlog post looks at our work on the issues students, educators, and schools are facing including pandemic learning loss, absenteeism, achievement at virtual charter schools, school redistricting, and bullying.

Learning loss and absent students

Some students may be returning to school behind on their education.

For a series of 2022 reports, we surveyed teachers about students’ potential learning loss during the pandemic. They told us that many students struggled to learn during the pandemic because of its disruption.

We found that, in the 2020-21 school year, across all grades and regardless of in-person, remote, or hybrid learning models, nearly two-thirds of teachers (64%) had more students who made less academic progress than in a typical school year. And 45% of teachers reported that at least half of their students ended the year a grade level behind.

While this learning loss was widespread, some students were disproportionately impacted, including students from high poverty households, students learning English, and our youngest K-12 students. As a result, long term, the pandemic may have contributed to growing disparities between student populations.

In addition, some students may not return to school this year at all. We recently found that, during the 2020-21 school year, more than a million teachers reported having students who never showed up for class despite being registered for school.

Students who did not show up came mostly from majority non-White and urban schools and faced obstacles to learning, such as no adult assistance at home. We also found that older students may have missed school because they were caring for family members or working themselves.

Lower student achievement in virtual charter schools

While many families were first introduced to virtual schooling during the pandemic, virtual and hybrid programs are not new. We recently explored challenges for students in virtual charter schools—the largest sector of virtual schools and the fastest growing type of public school in the U.S. For example, students attending virtual charter schools generally showed significantly lower rates of academic proficiency compared to the rest of their public school peers.

Virtual charter schools also reported lower student participation on federally-required state testing—a key measure of academic achievement. Our podcast with K-12 education expert Jackie Nowicki explores our work on virtual charter schools.

Racial/ethnic composition of schools and bullying contribute to equity issues

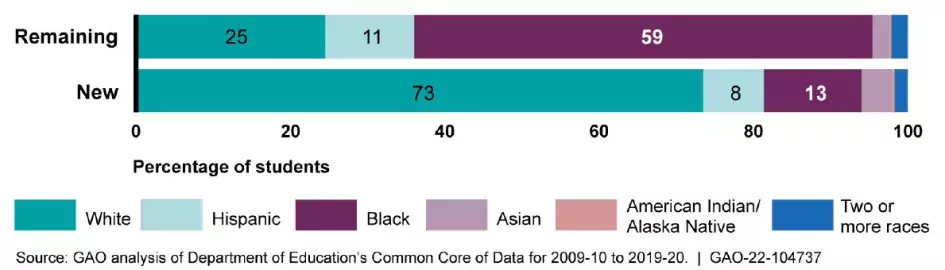

In a July report , we found that while the U.S. student population has become significantly more diverse, many schools remain divided along racial, ethnic, and economic lines.

Our recent analysis of 10 years of the Department of Education’s data on student race and ethnicity also shows that when schools broke away from their school districts, it generally resulted in Whiter and wealthier districts.

Specifically, new districts had half the share of students receiving free or reduced price lunches compared to the remaining districts. They also had far larger shares of White students, and far smaller shares of Hispanic and Black students than the remaining districts.

Racial/Ethnic Composition of New and Remaining Districts One Year after District Secession

Wealth and racial composition of schools matter.

It is widely known that a history of discriminatory practices has contributed to inequities in education, which are intertwined with disparities in wealth, income, and housing. We have previously reported that students who are poor, Black, or Hispanic generally attend schools with fewer resources and lower academic outcomes (about 80% of students attending low-income schools are Black or Hispanic).

Racial and ethnic minority students may face other obstacles in school beyond resources and quality of education. Each year, millions of K-12 students experience hostile behaviors like bullying, hate speech, hate crimes, or assault.

In a report published last November, we found that, during the 2018-19 school year, about 1.3 million students (ages 12 to 18) were bullied for their race, religion, national origin, disability, gender, or sexual orientation.

The Department of Education has resolved complaints about these hostile behaviors more quickly than in the past, largely because it dismissed more complaints than in previous years, and because the number of complaints filed declined overall. Some civil rights experts said they had become reluctant to file complaints because they lost confidence in the department’s ability to address these violations in schools.

To learn more about our findings on bullying, hate crimes, and violence in K-12 schools, check out our podcast:

While students will face significant obstacles this fall, their teachers are confronting burnout and concerns about teacher shortages abound. Our recent discussions with current and former teachers, as well as hiring officials and others involved in all levels of teacher recruitment and retention, will help shed light on the situation and ways to address it.

Keep an eye out for these findings and a report on discipline related to school dress code violations this fall.

- Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact [email protected] .

GAO Contacts

Related Posts

Back to School—Obstacles to Educating K-12 Students Persist

As Cyberattacks Increase on K-12 Schools, Here Is What’s Being Done

The Three Rs of Pandemic Learning: Roadblocks, Resilience, and Resources

Related products, k-12 education: students' experiences with bullying, hate speech, hate crimes, and victimization in schools, product number, k-12 education: student population has significantly diversified, but many schools remain divided along racial, ethnic, and economic lines, k-12 education: an estimated 1.1 million teachers nationwide had at least one student who never showed up for class in the 2020-21 school year [reissued with revisions on apr. 19, 2022].

GAO's mission is to provide Congress with fact-based, nonpartisan information that can help improve federal government performance and ensure accountability for the benefit of the American people. GAO launched its WatchBlog in January, 2014, as part of its continuing effort to reach its audiences—Congress and the American people—where they are currently looking for information.

The blog format allows GAO to provide a little more context about its work than it can offer on its other social media platforms. Posts will tie GAO work to current events and the news; show how GAO’s work is affecting agencies or legislation; highlight reports, testimonies, and issue areas where GAO does work; and provide information about GAO itself, among other things.

Please send any feedback on GAO's WatchBlog to [email protected] .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Why U.S. Schools Are Facing Their Biggest Budget Crunch in Years

Federal pandemic aid helped keep school districts afloat, but that money is coming to an end.

By Sarah Mervosh and Madeleine Ngo

After several cash-flush pandemic years, school districts across the country are facing budget shortfalls, with pressure closing in on multiple fronts.

A flow of federal dollars — $122 billion meant to help schools recover from the pandemic — is running dry in September, leaving schools with less money for tutors, summer school and other supports that have funded pandemic recovery efforts over the last three years.

At the same time, declining student enrollment — a consequence of lower birthrates and a growing school choice movement — is catching up to some districts.

The result: Districts across the country must make tough decisions about cuts that will affect millions of families as soon as the next school year. The cuts, which many districts put off during the pandemic, could interrupt the recovery of U.S. students, who by and large have not made up their pandemic losses .

“I’m concerned that too many state and district leaders had their heads in the sand about the coming fiscal cliff, and now they are being confronted with really painful decisions,” said Thomas S. Dee, a Stanford University professor who has studied student enrollment trends.

The cutbacks span districts rich and poor. In the Edmonds, Wash., school district, an upper-middle income area north of Seattle, music classes were a target of district slashes , mobilizing a local foundation to raise more than $200,000 to try to save them. In Montgomery County, Md., an upscale suburb, the district is slightly increasing class sizes to save money.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Transforming K–12 education for the better

August 26, 2023 K–12 schools have dealt with many challenges over the past few years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic put many existing problems into much sharper focus. Even so, there are many bright spots to point to as children head back into the classroom this fall. Some districts are rolling out new mental health interventions to support their students’ needs and others are seeing accelerated rates of learning recovery after adopting new instructional materials, according to McKinsey senior partner Jimmy Sarakatsannis , partner Jake Bryant , and colleagues. Read the full report to see how these combined interventions can create better learning experiences for all, and explore the rest of our recent education insights about how schools can transform for the better.

What it would take for US schools to fully recover from COVID-19

Author Talks: How educators can avoid burnout and embrace self-care

K–12 teachers are quitting. What would make them stay?

Advancing racial equity in US pre-K–12 education

Expanding publicly funded pre-K: How to do it and do it well

Lessons in leadership: Transforming struggling US K–12 schools

Author Talks: To nurture true potential, reimagine intelligence

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

Almost everyone is concerned about K-12 students’ academic progress

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, anna saavedra , anna saavedra behavioral scientist - usc dornsife center for economic and social research @annasaavedra19 morgan polikoff , morgan polikoff associate professor of education - usc rossier school of education @mpolikoff dan silver , and dan silver ph.d. student - usc rossier school of education @dans1lver amie rapaport amie rapaport director of research - gibson consulting.

March 23, 2021

Concern about our nation’s children is currently at the center of intense public debate. While the pandemic caused virtually all schools nationwide to close by April 2020—keeping almost all K-12 students home for the remainder of the 2019-20 school year—children’s mode of learning (fully in-person, fully remote, or a hybrid mix of the two) in 2020-21 has been highly variable .

Yet with vaccinations accelerating, COVID-19 rates falling, and money flowing, there is clear momentum behind offering in-person instruction. As schools begin to reopen, attention is turning to the deep changes necessary to reverse the learning opportunity disparities that are ingrained in U.S. education.

As educators consider possible changes, adults’ beliefs about the impacts of the pandemic on children’s academic progress—overall and for specific student subgroups—matter. These subjective opinions are important because they indicate political support, or lack thereof, for investment in education. Long-needed, fundamental, and sustained investments in and improvements to K-12 education—especially for underserved low-income and racial minority students—will need broad support. Beyond parents of elementary and secondary children and Democrats—those traditionally most supportive of investments in K-12 education—but from older and Republican voters, and from affluent as well as economically struggling voters.

To learn perspectives on children’s academic progress from adults with K-12 children in the household and from adults as a whole, we used data collected between Dec. 16, 2020, and Feb. 7, 2021, from a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults through the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research’s Understanding America Study . We asked how concerned adults were that today’s generation of K-12 students may not make as much academic progress this year as they would during a typical academic year. In addition to asking about concern for K-12 students overall, we asked separately about concern for students from lower-income households, students of color, elementary students, and middle/high school students.

The results were clear and overwhelming: Almost three-fourths (71%) of US adults are concerned about K-12 students’ current academic progress. Very few economic, political, or social concerns share this level of agreement in the population, implying policies and programs designed to address the negative impacts of the pandemic on schools could have broad support.

Given low-income communities and communities of color have been especially hard hit by the pandemic, schools in these neighborhoods will need even greater levels of resource and policy attention. We find even higher levels of concern for students in these groups: 81% of adults were concerned about lower-income children, and 77% about children of color.

Not only did we find levels of concern were high across the board, but we also found more advantaged groups were often more concerned about students’ academic progress (even when statistically controlling for an adult’s age, whether they have a K-12 child living in their household, adult race/ethnicity, household income, adult education level, and partisanship).

For instance, we found higher-income and more educated adults are more concerned—both overall and specifically about low-income students and students of color—than are low-income and less-educated adults. Seventy-four percent of adults in households making less than $25,000 are concerned about low-income children—lower than the corresponding rates for adults in households making $25,000-$150,000 (81-83% concerned about low-income children), and households making more than $150,000 (88%). As another example, greater proportions of adults aged 65 and older expressed greater levels of concern for low-income students and students of color, with 86% and 85% of adults over 65 concerned for each respective subgroup, compared to 77% and 72% concerned about these two student subgroups among adults aged 18-34. This is a promising pattern from an education policy perspective, as the unfortunate reality is that power to enact meaningful political change tends to be concentrated among the wealthiest and older individuals. These results suggest that those who tend to hold power may also have a will to enact meaningful, equity-based education policy in the wake of the pandemic.

We did not find racial differences. Regardless of their own race, adult Americans are equally concerned about the impacts of the pandemic for K-12 children.

Notably, too, we found high levels of bipartisan concern. Republicans (77%) and Democrats (70%) are concerned about K-12 children’s academic progress. Over 80% of Republicans and Democrats are concerned about lower-income children (81% Republicans, 84% Democrats) and close to 80% of each political group are concerned about children of color (76% Republicans, 82% Democrats). In other words, despite Congress’s partisan voting on the American Rescue Plan, there is widespread agreement that the effects of the pandemic on children are concerning.

In contrast, in 2019, relevant national survey results reflected much larger partisan differences on public education issues. For example, while 76% of Democrats thought education should be a top federal policy priority , 58% of Republicans felt the same. Also in 2019, 67% of Democrats supported or strongly supported basing part of teachers’ salaries on whether they teach in schools with many disadvantaged students , compared to 52% of Republicans.

What does this all mean? There may never have been more widespread, bipartisan concern about K-12 children’s educational progress, especially among adults without a K-12 child in the home. Unjust as it may be, political will to mobilize change often rests with more affluent and more educated groups. It also typically requires at least some degree of bipartisan agreement. The vast majority of affluent adults, and those from both sides of the political aisle, are concerned for K-12 children—particularly those who have been underserved. As districts and schools reopen, with leaders designing and rolling out new initiatives, they will likely find widespread encouragement.

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation Grants No.2037179 and 2120194. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The authors are also grateful to Marshall Garland, Shira Korn Haderlein, and the UAS administration team for their contributions to this work.

Related Content

Daphna Bassok, Lauren Bauer, Stephanie Riegg Cellini, Helen Shwe Hadani, Michael Hansen, Douglas N. Harris, Brad Olsen, Richard V. Reeves, Jon Valant, Kenneth K. Wong

March 12, 2021

Bruce Fuller

March 4, 2021

K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Sofoklis Goulas

June 27, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon, Kelsey Rappe

June 14, 2024

Jon Valant, Nicolas Zerbino

June 13, 2024

Multiple Choices: Weighing Updates to State Summative Assessments

Michelle Croft | Bonnie O’Keefe | Marisa Mission | Juliet Squire

Charting a Course

Juliet Squire | Marisa Mission | Paul Beach

The Edge of Seventeen: What Does It Mean To Be a Young Adult in America in 2024?

Andrew J. Rotherham | Chad Aldeman | Lynne Graziano | Andy Jacob

Leveling the Landscape: An Analysis of K-12 Funding Inequities Within Metro Areas

Alex Spurrier | Bonnie O’Keefe | Biko McMillan

The Evolution of Learning: How Education is Transforming for Future Generations

We are experiencing a monumental shift in education, and the progress that has been made in recent years has the potential to shape how students learn for generations to come. While these changes have also come with challenges for teachers, parents, and students alike, we cannot deny that we are moving toward a bright future for the world of education.

Some recent eye-catching headlines about education included topics such as artificial intelligence (AI) in the classroom, game-based learning, and a parent’s right to choose a school for their child. Let’s do a recap of these topics, how they changed education in past years, and what we can expect from them in the future.

AI in the Classroom

It should come as no surprise that the use of AI in the classroom is a controversial topic. As schools began implementing AI tools to assist teachers, many parents and even teachers expressed concern that this could depersonalize learning. And yet, it has proven to do the opposite. Here’s how:

Lessons and learning materials can be adapted to each student’s personal learning needs and pace. If a student is not quite grasping a concept, more time or information can be provided automatically to that student.

Using a set of grading guidelines, also known as a rubric, AI can grade and provide detailed feedback for assignments and tests. Teachers have full authority over final grades and feedback, but this can help reduce the time spent grading, and thus allowing for more one-to-one interactions between teachers and students.

Teachers can view classroom analytics that detail student performance and learning trends, providing helpful insights for future lesson plans and assignments.

Looking toward the future, we should expect more finetuning of these tools whether that means advancement in what’s currently available or revolutionary technology. For example, a report by the Department of Education from May 2023 explains that context is an important next step. AI relies on patterns to automate decisions, rather than situational judgment. Researchers are working to address context sensitivity and develop platforms that are responsive to individual characteristics and situations. Other experts say that AI will be used to determine whether a typical school day and classroom lessons should be restructured as the global economy rapidly evolves.

Playing to Learn

There is an inherent human tendency to be motivated by challenges, rewards, and competition. So, it makes sense that games can effectively capture a student’s attention and fuel their motivation . In fact, research shows that games can be a powerful teaching tool that increases participation and promotes social-emotional skills.

That’s why schools like K12-powered online schools have incorporated exclusive Minecraft Education game-based lessons in their classes. Through these games, history comes to life for students who can explore historical settings like Ancient Rome or Egypt in a virtual universe where they interact with their surroundings.

Virtual or augmented reality is another increasingly popular tool for immersive learning. Through platforms such as IXR Labs, medical students can stand inside of the human heart and see how each part functions, while aerospace engineering students can gain hands-on experience designing and constructing a jet engine.

While game-based learning is not new to education (think back to games like Math Blaster or Oregon Trailer on a large PC in your school), it’s rapidly evolving and growing in popularity, and we should expect this movement to gain momentum as technology advances and offers more options for learning resources. Career prep and training is one field that is expected to benefit from game-based learning in the future, while others say that students will soon have the opportunity to be completely immersed in a fully formed universe, zooming through space from one planet to another.

Parental School Choice

In 2023, nearly half of all parents surveyed across the United States reported that they were actively seeking a new school for the 2023-24 school year. The National School Choice Week survey, which took place in May 2023, explored whether parents were satisfied with their child’s school experiences. And while nearly 45 percent of parents reported that the current school year was better than a previous year and 34.4 percent said it was relatively the same, only 54 percent of parents planned to keep their child enrolled in their current school.

As the school choice movement grew in 2023, it’s clear that the status quo simply isn’t working for many families. And this is just the beginning of a massive shift in education. A heavier focus has been placed on meeting students where they are, taking into consideration their individual characteristics, experiences, and learning styles.

This is why the online classroom has become an increasingly popular option. Online school offers flexibility and personalized elements that are not typically found in a traditional classroom. And many parents and their children are eager to explore these different avenues for learning to find the right fit.

Looking toward the future, we can expect the school choice movement to continue making headlines as parents take control of their children’s education, finding the right learning environment that can truly complement each child’s individual needs and goals.

Looking Forward

Education is changing. Schools are finding new ways to engage children and incorporate elements like games and AI that can help keep them actively participating and interested in content. While parents are seeing the possibilities in different school options to help their children reach their fullest potential. It’s an exciting time to be involved in academics, and we can expect to see progress and advancements by leaps and bounds in the coming years.

To learn more about online school and its benefits, go to K12.com .

Related Articles

5 Ways to Start the School Year with Confidence

July 8 2024

Top Four Reasons Families Are Choosing Online School in the Upcoming Year

Tips for Scheduling Your Online School Day

July 2 2024

Life After High School: Online School Prepares Your Child For The Future

The Ultimate Back-to-School List for Online and Traditional School

July 1 2024

Nurturing Digital Literacy in Today’s Kids: A Parent’s Guide

June 25 2024

What Public Schools Can Do About Special Education Teacher Shortages

June 24 2024

Audiobooks for Kids: Benefits, Free Downloads, and More

7 Fun Outdoor Summer Activities for Kids

June 18 2024

Beat the Summer Slide: Tips for Keeping Young Minds Active

June 11 2024

How to Encourage Your Child To Pursue a Career

Easy Science Experiments For Kids To Do At Home This Summer

May 31 2024

4 Ways to Get Healthcare Experience in High School

May 29 2024

5 Strategies for Keeping Students Engaged in Online Learning

May 21 2024

How Parents Can Prevent Isolation and Loneliness During Summer Break

May 14 2024

The Ultimate Guide to Gift Ideas for Teachers

How to Thank a Teacher: Heartfelt Gestures They Won’t Forget

Six Ways Online Schools Can Support Military Families

7 Things Teachers Should Know About Your Child

April 30 2024

Countdown to Graduation: How to Prepare for the Big Day

April 23 2024

How am I Going to Pay for College?

April 16 2024

5 Major Benefits of Summer School

April 12 2024

Inspiring an Appreciation for Poetry in Kids

April 9 2024

A Parent’s Guide to Tough Conversations

April 2 2024

The Importance of Reading to Children and Its Enhancements to Their Development

March 26 2024

5 Steps to Master College-Level Reading

March 19 2024

10 Timeless Stories to Inspire Your Reader: Elementary, Middle, and High Schoolers

March 15 2024

From Books to Tech: Why Libraries Are Still Important in the Digital Age

March 13 2024

March 11 2024

The Ultimate Guide to Reading Month: 4 Top Reading Activities for Kids

March 1 2024

Make Learning Fun: The 10 Best Educational YouTube Channels for Kids

February 27 2024

The Value of Soft Skills for Students in the Age of AI

February 20 2024

Why Arts Education is Important in School

February 14 2024

30 Questions to Ask at Your Next Parent-Teacher Conference

February 6 2024

Smart Classrooms, Smart Kids: How AI is Changing Education

January 31 2024

Four Life Skills to Teach Teenagers for Strong Resumes

January 25 2024

Exploring the Social Side of Online School: Fun Activities and Social Opportunities Await

January 9 2024

Is Your Child Ready for Advanced Learning? Discover Your Options.

January 8 2024

Online School Reviews: What People Are Saying About Online School

January 5 2024

Your Ultimate Guide to Holiday Fun and Activities

December 18 2023

Free Printable Holiday Coloring Pages to Inspire Your Child’s Inner Artist

December 12 2023

Five Reasons to Switch Schools Midyear

December 5 2023

A Parent’s Guide to Switching Schools Midyear

November 29 2023

Building Strong Study Habits: Back-to-School Edition

November 17 2023

Turn Up the Music: The Benefits of Music in Classrooms

November 7 2023

A Parent’s Guide to Robotics for Kids

November 6 2023

Six Ways Online Learning Transforms the Academic Journey

October 31 2023

How to Get Ahead of Cyberbullying

October 30 2023

Bullying’s Effect on Students and How to Help

October 25 2023

Can You Spot the Warning Signs of Bullying?

October 16 2023

Could the Online Classroom Be the Solution to Bullying?

October 11 2023

Bullying Prevention Starts With Parents

October 9 2023

Join Us in Celebrating National Online Learning Day

August 22 2016

Dispelling the Top 5 Myths about Online Education

January 30 2022

How Online School Can Transform Learning Wait Time

September 21 2022

Virtual Learning and Socializing

March 22 2010

Join our community

Sign up to participate in America’s premier community focused on helping students reach their full potential.

Welcome! Join Learning Liftoff to participate in America’s premier community focused on helping students reach their full potential.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

More students with disabilities are facing discrimination in schools

Jonaki Mehta

The Department of Education has received a record number of discrimination complaints, including from families of students with disabilities. Some families are waiting months, even years, for help.

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What’s It Like To Be a Teacher in America Today?

4. challenges in the classroom, table of contents.

- Problems students are facing

- A look inside the classroom

- How teachers are experiencing their jobs

- How teachers view the education system

- Satisfaction with specific aspects of the job

- Do teachers feel trusted to do their job well?

- Likelihood that teachers will change jobs

- Would teachers recommend teaching as a profession?

- Reasons it’s so hard to get everything done during the workday

- Staffing issues

- Balancing work and personal life

- How teachers experience their jobs

- Lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Major problems at school

- Discipline practices

- Policies around cellphone use

- Verbal abuse and physical violence from students

- Addressing behavioral and mental health challenges

- Teachers’ interactions with parents

- K-12 education and political parties

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

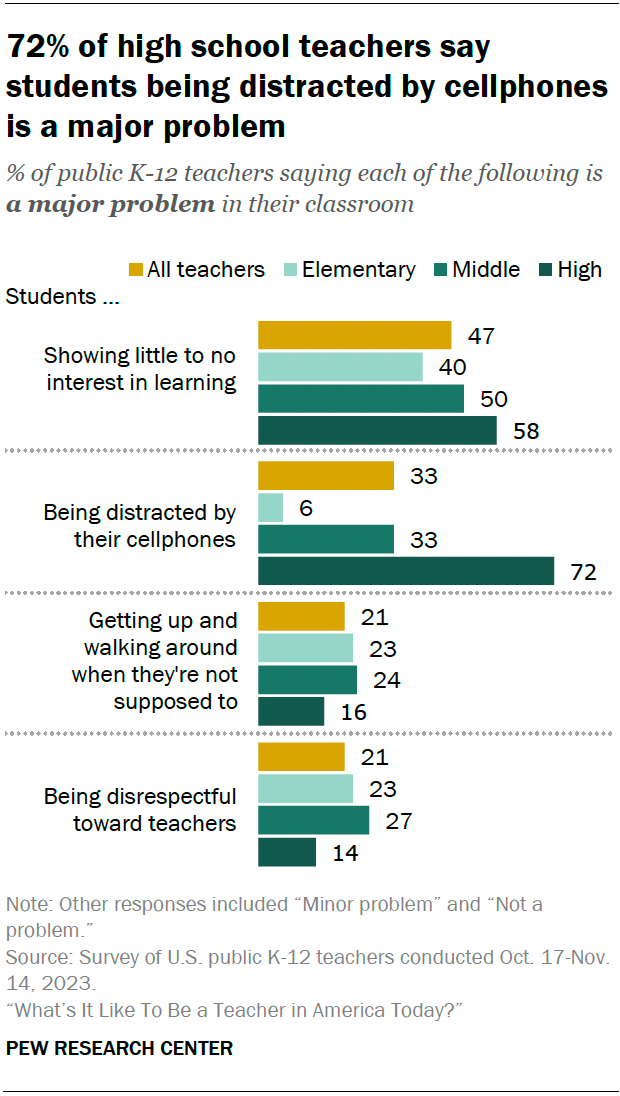

In addition to asking public K-12 teachers about issues they see at their school, we asked how much each of the following is a problem among students in their classroom :

- Showing little to no interest in learning (47% say this is a major problem)

- Being distracted by their cellphones (33%)

- Getting up and walking around when they’re not supposed to (21%)

- Being disrespectful toward the teacher (21%)

Some challenges are more common among high school teachers, while others are more common among those who teach elementary or middle school.

- Cellphones: 72% of high school teachers say students being distracted by their cellphones in the classroom is a major problem. A third of middle school teachers and just 6% of elementary school teachers say the same.

- Little to no interest in learning: A majority of high school teachers (58%) say students showing little to no interest in learning is a major problem. This compares with half of middle school teachers and 40% of elementary school teachers.

- Getting up and walking around: 23% of elementary school teachers and 24% of middle school teachers see students getting up and walking around when they’re not supposed to as a major problem. A smaller share of high school teachers (16%) say the same.

- Being disrespectful: 23% of elementary school teachers and 27% of middle school teachers say students being disrespectful toward them is a major problem. Just 14% of high school teachers say this.

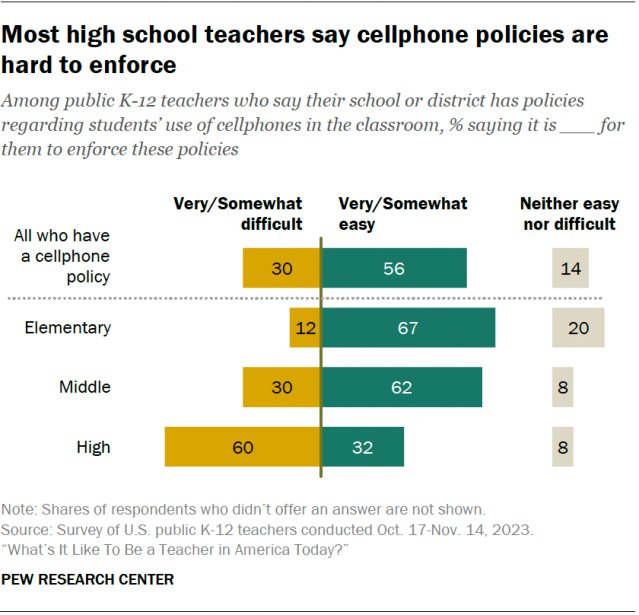

About eight-in-ten teachers (82%) say their school or district has policies regarding students’ use of cellphones in the classroom. Of those, 56% say these policies are at least somewhat easy to enforce, 30% say they’re difficult to enforce, and 14% say they’re neither easy nor difficult to enforce.

High school teachers are the least likely to say their school or district has policies regarding students’ use of cellphones in the classroom (71% vs. 84% of elementary school teachers and 94% of middle school teachers).

Among those who say there are such policies at their school, high school teachers are the most likely to say these are very or somewhat difficult to enforce. Six-in-ten high school teachers say this, compared with 30% of middle school teachers and 12% of elementary school teachers.

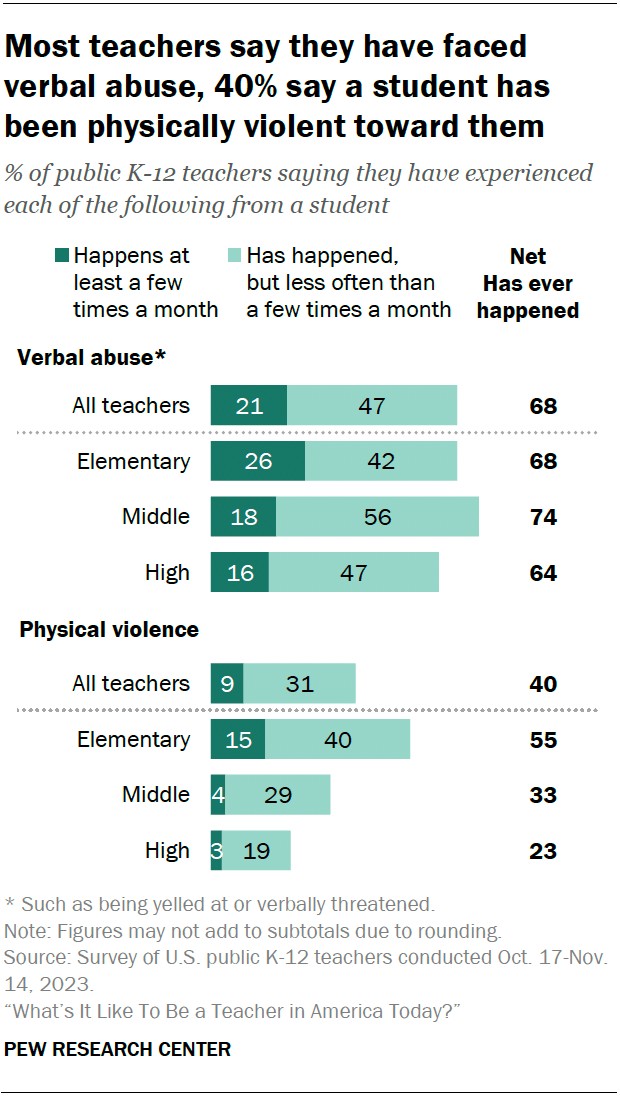

Most teachers (68%) say they have experienced verbal abuse from their students, such as being yelled at or verbally threatened. About one-in-five (21%) say this happens at least a few times a month.

Physical violence is far less common, but about one-in-ten teachers (9%) say a student is physically violent toward them at least a few times a month. Four-in-ten say this has ever happened to them.

Differences by school level

Elementary school teachers (26%) are more likely than middle and high school teachers (18% and 16%) to say they experience verbal abuse from students a few times a month or more often.

And while relatively small shares across school levels say students are physically violent toward them a few times a month or more often, elementary school teachers (55%) are more likely than middle and high school teachers (33% and 23%) to say this has ever happened to them.

Differences by poverty level

Among teachers in high-poverty schools, 27% say they experience verbal abuse from students at least a few times a month. This is larger than the shares of teachers in medium- and low-poverty schools (19% and 18%) who say the same.

Experiences with physical violence don’t differ as much based on school poverty level.

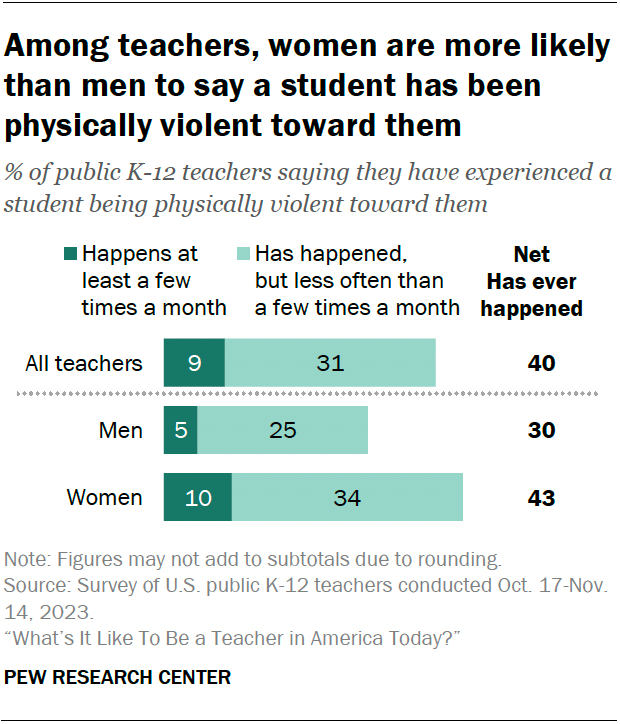

Differences by gender

Teachers who are women are more likely than those who are men to say a student has been physically violent toward them. Some 43% of women teachers say this, compared with 30% of men.

There is also a gender difference in the shares of teachers who say they’ve experienced verbal abuse from students. But this difference is accounted for by the fact that women teachers are more likely than men to work in elementary schools.

Eight-in-ten teachers say they have to address students’ behavioral issues at least a few times a week, with 58% saying this happens every day .

A majority of teachers (57%) also say they help students with mental health challenges at least a few times a week, with 28% saying this happens daily.

Some teachers are more likely than others to say they have to address students’ behavior and mental health challenges on a daily basis. These include:

- Women: 62% of women teachers say they have to address behavior issues daily, compared with 43% of those who are men. And while 29% of women teachers say they have to help students with mental health challenges every day, a smaller share of men (19%) say the same.

- Elementary and middle school teachers: 68% each among elementary and middle school teachers say they have to deal with behavior issues daily, compared with 39% of high school teachers. A third of elementary and 29% of middle school teachers say they have to help students with mental health every day, compared with 19% of high school teachers.

- Teachers in high-poverty schools: 67% of teachers in schools with high levels of poverty say they have to address behavior issues on a daily basis. Smaller majorities of those in schools with medium or low levels of poverty say the same (56% and 54%). A third of teachers in high-poverty schools say they have to help students with mental health challenges every day, compared with about a quarter of those in medium- or low-poverty schools who say they have this experience (26% and 24%).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Education & Politics

72% of U.S. high school teachers say cellphone distraction is a major problem in the classroom

U.s. public, private and charter schools in 5 charts, is college worth it, half of latinas say hispanic women’s situation has improved in the past decade and expect more gains, a quarter of u.s. teachers say ai tools do more harm than good in k-12 education, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Trade Schools, Colleges and Universities

Join Over 1.5 Million People We've Introduced to Awesome Schools Since 2001

Trade Schools Home > Articles > Issues in Education

Major Issues in Education: 20 Hot Topics (From Grade School to College)

By Publisher | Last Updated August 1, 2023

In America, issues in education are big topics of discussion, both in the news media and among the general public. The current education system is beset by a wide range of challenges, from cuts in government funding to changes in disciplinary policies—and much more. Everyone agrees that providing high-quality education for our citizens is a worthy ideal. However, there are many diverse viewpoints about how that should be accomplished. And that leads to highly charged debates, with passionate advocates on both sides.

Understanding education issues is important for students, parents, and taxpayers. By being well-informed, you can contribute valuable input to the discussion. You can also make better decisions about what causes you will support or what plans you will make for your future.

This article provides detailed information on many of today's most relevant primary, secondary, and post-secondary education issues. It also outlines four emerging trends that have the potential to shake up the education sector. You'll learn about:

- 13 major issues in education at the K-12 level

- 7 big issues in higher education

- 5 emerging trends in education

13 Major Issues in Education at the K-12 Level

1. Government funding for education

School funding is a primary concern when discussing current issues in education. The American public education system, which includes both primary and secondary schools, is primarily funded by tax revenues. For the 2021 school year, state and local governments provided over 89 percent of the funding for public K-12 schools. After the Great Recession, most states reduced their school funding. This reduction makes sense, considering most state funding is sourced from sales and income taxes, which tend to decrease during economic downturns.

However, many states are still giving schools less cash now than they did before the Great Recession. A 2022 article from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) notes that K-12 education is set to receive the largest-ever one-time federal investment. However, the CBPP also predicts this historic funding might fall short due to pandemic-induced education costs. The formulas that states use to fund schools have come under fire in recent years and have even been the subjects of lawsuits. For example, in 2017, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that the legislature's formula for financing schools was unconstitutional because it didn't adequately fund education.

Less funding means that smaller staff, fewer programs, and diminished resources for students are common school problems. In some cases, schools are unable to pay for essential maintenance. A 2021 report noted that close to a quarter of all U.S. public schools are in fair or poor condition and that 53 percent of schools need renovations and repairs. Plus, a 2021 survey discovered that teachers spent an average of $750 of their own money on classroom supplies.

The issue reached a tipping point in 2018, with teachers in Arizona, Colorado, and other states walking off the job to demand additional educational funding. Some of the protests resulted in modest funding increases, but many educators believe that more must be done.

2. School safety

Over the past several years, a string of high-profile mass shootings in U.S. schools have resulted in dozens of deaths and led to debates about the best ways to keep students safe. After 17 people were killed in a shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida in 2018, 57 percent of teenagers said they were worried about the possibility of gun violence at their school.

Figuring out how to prevent such attacks and save students and school personnel's lives are problems faced by teachers all across America.

Former President Trump and other lawmakers suggested that allowing specially trained teachers and other school staff to carry concealed weapons would make schools safer. The idea was that adult volunteers who were already proficient with a firearm could undergo specialized training to deal with an active shooter situation until law enforcement could arrive. Proponents argued that armed staff could intervene to end the threat and save lives. Also, potential attackers might be less likely to target a school if they knew that the school's personnel were carrying weapons.

Critics argue that more guns in schools will lead to more accidents, injuries, and fear. They contend that there is scant evidence supporting the idea that armed school officials would effectively counter attacks. Some data suggests that the opposite may be true: An FBI analysis of active shooter situations between 2000 and 2013 noted that law enforcement personnel who engaged the shooter suffered casualties in 21 out of 45 incidents. And those were highly trained professionals whose primary purpose was to maintain law and order. It's highly unlikely that teachers, whose focus should be on educating children, would do any better in such situations.