CHAPTER 11 Speech Delivery

Jan 02, 2020

210 likes | 443 Views

CHAPTER 11 Speech Delivery. 11.1 Effective Speech Delivery 11.2 Delivery, Rehearsal, and Audience Adaptation. Lesson 11.1 Effective Speech Delivery. GOALS Explain the characteristics of an effective delivery style. Describe how to use your voice effectively when delivering speeches.

Share Presentation

- speech delivery

- speech notes

- nonverbal language

- speech notes effective

- chapter 11 speech delivery

Presentation Transcript

CHAPTER 11Speech Delivery 11.1 Effective Speech Delivery 11.2 Delivery, Rehearsal, and Audience Adaptation

Lesson 11.1Effective Speech Delivery CHAPTER11 GOALS • Explain the characteristics of an effective delivery style. • Describe how to use your voice effectively when delivering speeches. • Define nonverbal communication and discuss different types.

An Effective Delivery Style CHAPTER11 • Speech delivery • Nonverbal language

Conversational Tone CHAPTER11 • Sounds relaxed and informal • Allows you to talk with, not at, the audience • Sounds as if you are thinking about the ideas and the audience

Developing a Conversational Tone CHAPTER11 • Learn the ideas • Don’t memorize • Rehearse

Be Animated CHAPTER11 • Animated delivery • Lively • Energetic • Enthusiastic • Dynamic • Level of animation

Use Your Voice Effectively CHAPTER11 • Speak clearly • Use vocal expressiveness

Speak Clearly CHAPTER11 • Vocal characteristics • Pitch • Volume • Rate • Quality • Articulation and accent • Articulation • Accent

Use Vocal Expressiveness CHAPTER11 • Changing pitch, volume, and rate • Expressing of certain words • Using pauses

Effective Nonverbal Language CHAPTER11 • Facial expressions • Gestures • Movement • Eye contact • Posture • Appearance

Lesson 11.2Delivery, Rehearsal, and Audience Adaptation CHAPTER11 GOALS • Explain three speech delivery methods. • Discuss how to rehearse your speech. • Identify guidelines for adapting to the audience while giving your speech.

Speech Delivery Methods CHAPTER11 • Impromptu speeches • Scripted speeches • Extemporaneous speeches

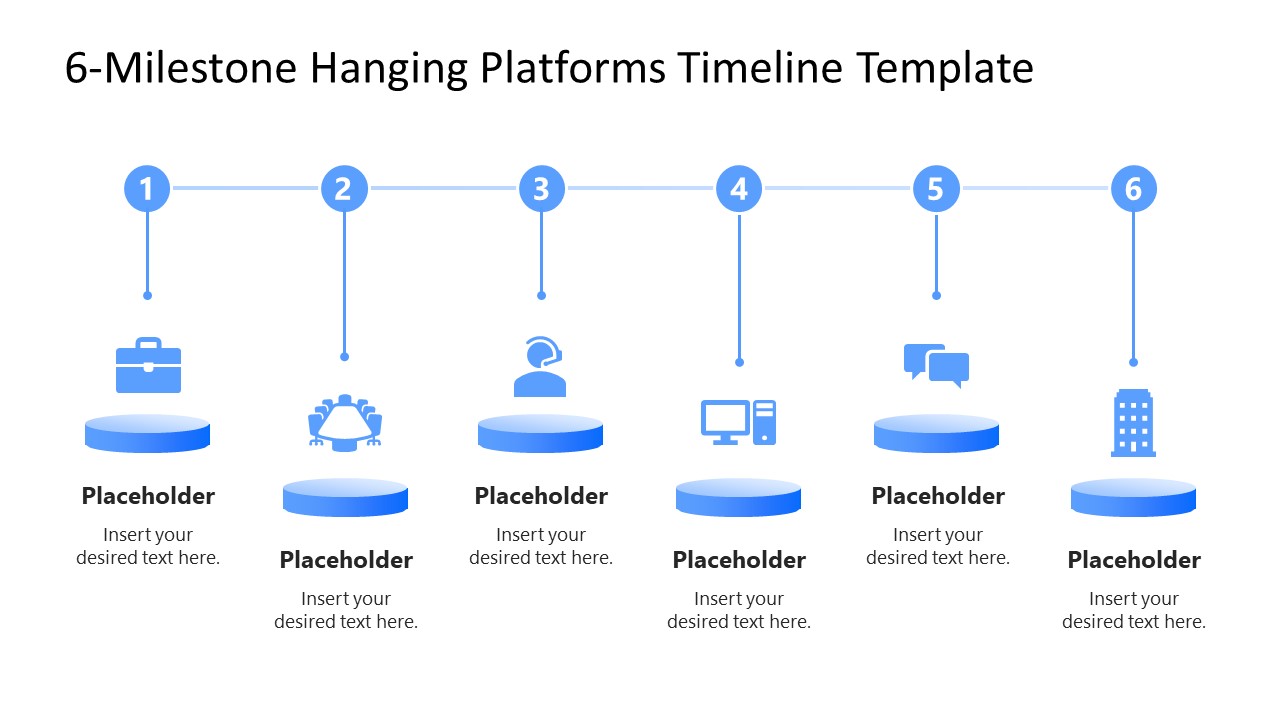

Rehearsal CHAPTER11 • Schedule and conduct rehearsal sessions • Prepare speech notes • Rehearse your speech

Rehearse Your Speech CHAPTER11 1. Practice wording your ideas 2. Practice working with your voice and movements 3. Practice using your presentation aids and speech notes

First Rehearsal CHAPTER11 1. Audiotape or videotape your practice session 2. Read through your complete outline two times to refresh your memory 3. Make the practice as similar to the speech situation as possible 4. Write down the time you begin 5. Begin speaking, and present your entire speech 6. Write down the time you finish

Analysis CHAPTER11 • Did you leave out any key ideas? • Did you talk too long on one point? • Did you devote too little time to one point? • Were your speech notes effective? • How well did you do with your presentation aids?

Second Rehearsal CHAPTER11 • Complete second rehearsal immediately after the first • Repeat the six steps listed for the first rehearsal

Additional Rehearsals CHAPTER11 • Wait several hours or until the next day • Rehearse at least one more time • Practice until you are comfortable

Adapt to Your Audience CHAPTER11 1. Be aware of and respond to the audience’s feedback 2. Be prepared to use alternative material you have developed 3. Correct yourself when you make a mistake 4. Adapt to unexpected events 5. Adapt to unexpected audience reactions 6. Handle questions with respect

- More by User

Speech Delivery

Speech Delivery. What to do! What NOT to do!. Before speaking. Before speaking, make sure you… Dress well (increase confidence) Have the entire speech written out verbatim Have the introduction memorized Take a mouthful or two of water Make sure all your notes are in order

228 views • 6 slides

Chapter 11 Parts of Speech Overview Noun, Pronoun, Adjective

The noun. P. 337Define

445 views • 25 slides

Chapter 7 SPEECH COMMUNICATIONS

Chapter 7 SPEECH COMMUNICATIONS. Speech is an information display in auditory form. Sender and/or receiver may be either human or machine. nature of speech criteria to evaluate speech communtication components of speech communication and intelligibility synthetic speech. I. Speech.

476 views • 19 slides

Chapter 11 Voice and Data Delivery Networks

Chapter 11 Voice and Data Delivery Networks. Introduction. Basic Telephone Systems Dial-up Modem ISDN DSL Cable Modem T1 Leased Line Services Frame Relay ATM CTI & UC. Basic Telephone Systems (I). POTS is the ‘plain old telephone system’ Transmit voice at bandwidth less than 4000 Hz

439 views • 28 slides

Speech Recognition Chapter 3

Speech Recognition Chapter 3. Speech Front-Ends. Linear Prediction Analysis Linear-Prediction Based Processing Cepstral Analysis Auditory signal Processing. Linear Prediction Analysis. Introduction Linear Prediction Model Linear Prediction Coefficients Computation

987 views • 80 slides

Chapter Two Speech Sounds

Chapter Two Speech Sounds. As human beings we are capable of making all kinds of sounds, but only some of these sounds have become units in the language system. We can analyze speech sounds from various perspectives and the two major areas of study are phonetics and phonology . .

1.61k views • 98 slides

Chapter 19: Freedom of Speech Honors Classes, Dec. 11, 2013

Chapter 19: Freedom of Speech Honors Classes, Dec. 11, 2013. The Owner’s Manual says…. … “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech or of the press….”

376 views • 23 slides

DELIVERY BOOTCAMP Driving Delivery April 11, 2014

DELIVERY BOOTCAMP Driving Delivery April 11, 2014. Session Objectives. At the end of this session, you will : Understand the core components and tools of driving delivery Have heard of how routines have been useful in for the Oregon School Turnaround and the Hawai’i Department of Education.

506 views • 39 slides

Speech Delivery Elements

Speech Delivery Elements. An overview. Before We Begin…. What do you think makes a good speech? Or…. What do you think makes a bad speech? . Content is Key but . . . Non-verbal Communication [Paralanguage] plays a HUGE role in the success or failure of a speech

462 views • 22 slides

Assisted Delivery and Cesarean Birth Chapter 11

Assisted Delivery and Cesarean Birth Chapter 11. Objectives. 1. Identify medical indications for induction of labor. 2. Explain methods practitioners use to determine labor readiness. 3. Contrast mechanical methods for hastening cervical readiness with pharmacologic methods.

949 views • 36 slides

Elements Aiding in speech delivery

Elements Aiding in speech delivery. Audio-Visual Aids. 3 days Later Information only told……….. 10% Information only shown-------- 20% Information told and shown-------65% Models chalkboard Maps People Pictures posters charts graphs

217 views • 9 slides

Great Speech Analyses & Delivery

Great Speech Analyses & Delivery. Doris L. W. Chang. Definition of an A Speech (Fletcher). An “A” means superior content, outstanding organization, and distinctive delivery. An A speech

559 views • 37 slides

Chapter 4: Delivery

Hounslow 2013/14: An integrated delivery plan. Chapter 4: Delivery. June, 2012. Progress to date: Delivery QIPP 13/14 plans. ü. Identified areas that are critical to deliver the QIPP plans and that need investment. ü. Identified gaps in current capability and capacity to deliver. ü.

753 views • 59 slides

Speech I – Chapter 13

Speech I – Chapter 13. Presenting Your Speech. Presenting Your Speech. What do you think is the BEST thing to do to make sure you give a great speech?. Methods of Delivery. Impromptu Manuscript Memorized Extemporaneous. Impromptu. Given on the spur of the moment with ZERO preparation.

385 views • 14 slides

The importance of DELIVERY. Speech Delivery. What makes a good speech?. Speak Clearly. Enunciate so the audience can understand what you are saying. Speak slowly and keep a good pace Use emphasis to make your speech more interesting. Enunciation Exercises.

509 views • 12 slides

Chapter 3.2 Speech Communication

Chapter 3.2 Speech Communication. Human Performance Engineering Robert W. Bailey, Ph.D. Third Edition. The Designer’s Responsibility to know:. Where The Frequency and Types Why The Content The Conditions The Consequences. The Speech Communication Chain.

469 views • 19 slides

Chapter 2 Speech Sounds

Chapter 2 Speech Sounds. Phonetics and Phonology Phonetics: the study of sounds The production of speech The sounds of speech The description and classification of speech sounds, words and connected speech, etc. It focuses on chaos.

2.58k views • 28 slides

Chapter 6 Speech

Chapter 6 Speech. By Frankie, K. F. Yip. Sound Waves. The sound waves are longitudinal waves. Period is the time required for one complete cycle. Pressure. Period. amplitude. Time. Wavelength is the distance travelled in one cycle. Pressure. Wavelength. amplitude. Distance.

545 views • 44 slides

Chapter two speech sounds

Chapter two speech sounds. What is phonetics? What is phonology? How phonological study is conducted? Phonological structure=sound patterns. 2.1 how speech sounds are made. 2.1.1 speech organs Speech organs = vocal organs

648 views • 31 slides

Chapter 13: Speech Perception

Chapter 13: Speech Perception. The Acoustic Signal. Produced by air that is pushed up from the lungs through the vocal cords and into the vocal tract Vowels are produced by vibration of the vocal cords and changes in the shape of the vocal tract by moving the articulators.

937 views • 48 slides

Chapter 13: Speech Perception. Overview of Questions. Can computers perceive speech as well as humans? Why does an unfamiliar foreign language often sound like a continuous stream of sound, with no breaks between words?

591 views • 40 slides

Speech Chapter 2

Speech Chapter 2. Oral Language. Key Vocabulary. Denotation Connotation Usage Colloquialisms Syntax Substance Style Clarity Economy Grace Abstract Concrete Dialect Idiom Jargon. Denotation and Connotation. Denotation: Literal meaning, settled by consulting a dictionary

173 views • 8 slides

Module 6: Organizing and Outlining Your Speech

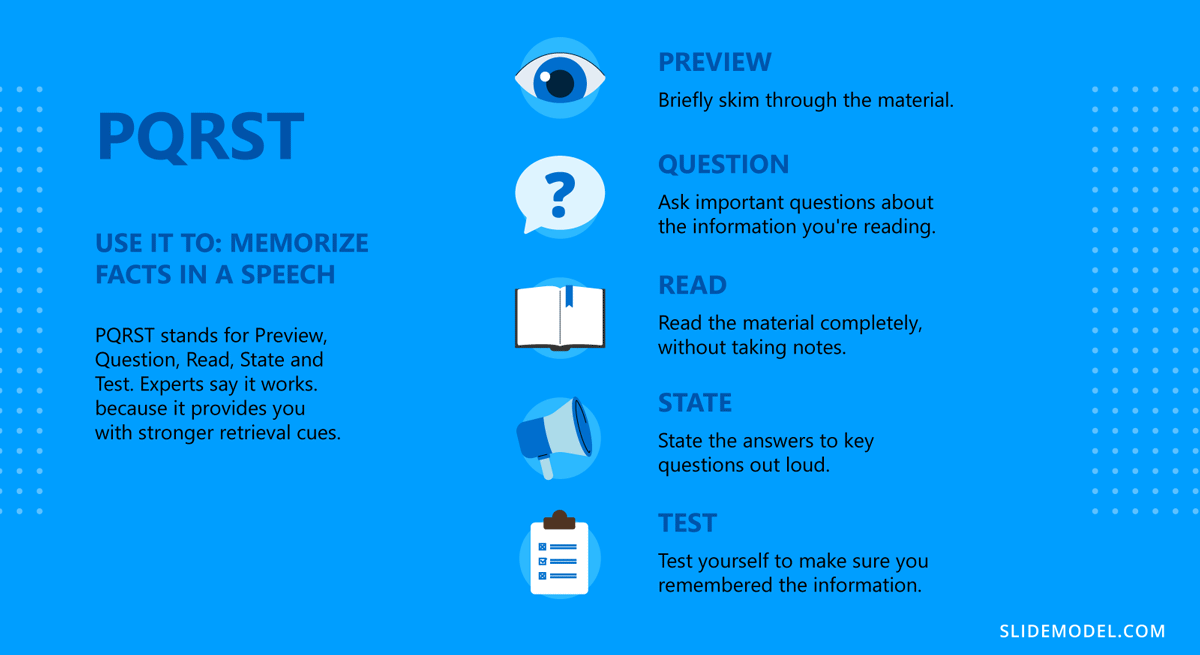

Methods of speech delivery, learning objectives.

Identify the four types of speech delivery methods and when to use them.

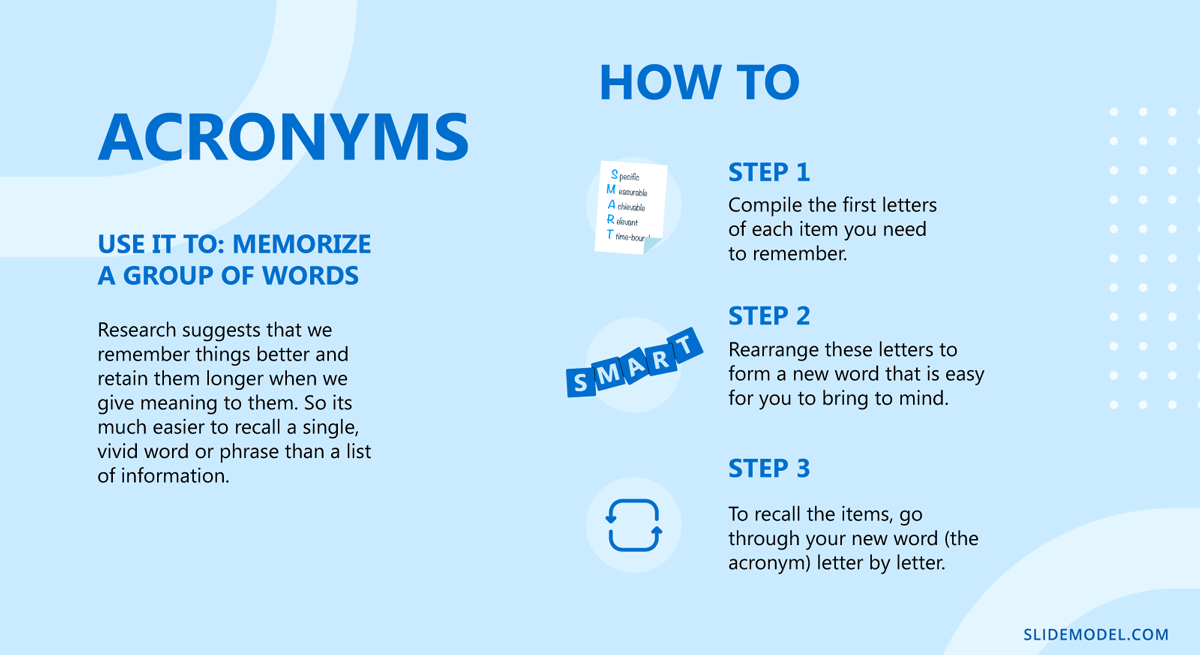

There are four basic methods of speech delivery: manuscript, memorized, impromptu, and extemporaneous. We’ll look at each method and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each.

A manuscript page from President George W. Bush’s address to the nation on the day of the 9/11 attacks in 2001.

A manuscript speech is when the speaker writes down every word they will speak during the speech. When they deliver the speech, they have each word planned and in front of them on the page, much like a newscaster who reads from a teleprompter.

The advantage of using a manuscript is that the speaker has access to every word they’ve prepared in advance. There is no guesswork or memorization needed. This method comforts some speakers’ nerves as they don’t have to worry about that moment where they might freeze and forget what they’ve planned to say. They also are able to make exact quotes from their source material.

When the exact wording of an idea is crucial, speakers often read from a manuscript, for instance in communicating public statements from a company.

However, the disadvantage with a manuscript is that the speakers have MANY words in front of them on the page. This prohibits one of the most important aspects of delivery, eye contact. When many words are on the page, the speakers will find themselves looking down at those words more frequently because they will need the help. If they do look up at the audience, they often cannot find their place when the eye returns to the page. Also, when nerves come into play, speakers with manuscripts often default to reading from the page and forget that they are not making eye contact or engaging their audience. Therefore, manuscript is a very difficult delivery method and not ideal. Above all, the speakers should remember to rehearse with the script so that they practice looking up often.

Public Speaking in History

The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, owed in large part to a momentary error made by an East German government spokesperson. At a live press conference, Günter Schabowski tried to explain new rules relaxing East Germany’s severe travel restrictions. A reporter asked, “when do these new rules go into effect?” Visibly flustered, Schabowski said, “As far as I know, it takes effect immediately, without delay.” In fact, the new visa application procedure was supposed to begin the following day, and with a lot of bureaucracy and red tape. Instead, thousands of East Berliners arrived within minutes at the border crossings, demanding to pass through immediately. The rest is history.

The outcome of this particular public-relations blunder was welcomed by the vast majority of East and West German citizens, and hastened the collapse of communism in Eastern and Central Europe. It’s probably good, then, that Schabowski ran this particular press conference extemporaneously, rather than reading from a manuscript.

You can view the transcript for “The mistake that toppled the Berlin Wall” here (opens in new window) .

A memorized speech is also fully prepared in advance and one in which the speaker does not use any notes. In the case of an occasion speech like a quick toast, a brief dedication, or a short eulogy, word-for-word memorization might make sense. Usually, though, it doesn’t involve committing each and every word to memory, Memorizing a speech isn’t like memorizing a poem where you need to remember every word exactly as written. Don’t memorize a manuscript! Work with your outline instead. Practice with the outline until you can recall the content and order of your main points without effort. Then it’s just a matter of practicing until you’re able to elaborate on your key points in a natural and seamless manner. Ideally, a memorized speech will sound like an off-the-cuff statement by someone who is a really eloquent speaker and an exceptionally organized thinker!

The advantage of a memorized speech is that the speaker can fully face their audience and make lots of eye contact. The problem with a memorized speech is that speakers may get nervous and forget the parts they’ve memorized. Without any notes to lean on, the speaker may hesitate and leave lots of dead air in the room while trying to recall what was planned. Sometimes, the speaker can’t remember or find his or her place in the speech and are forced to go get the notes or go back to the PowerPoint in some capacity to try to trigger his or her memory. This can be an embarrassing and uncomfortable moment for the speaker and the audience, and is a moment which could be easily avoided by using a different speaking method.

How to: memorize a speech

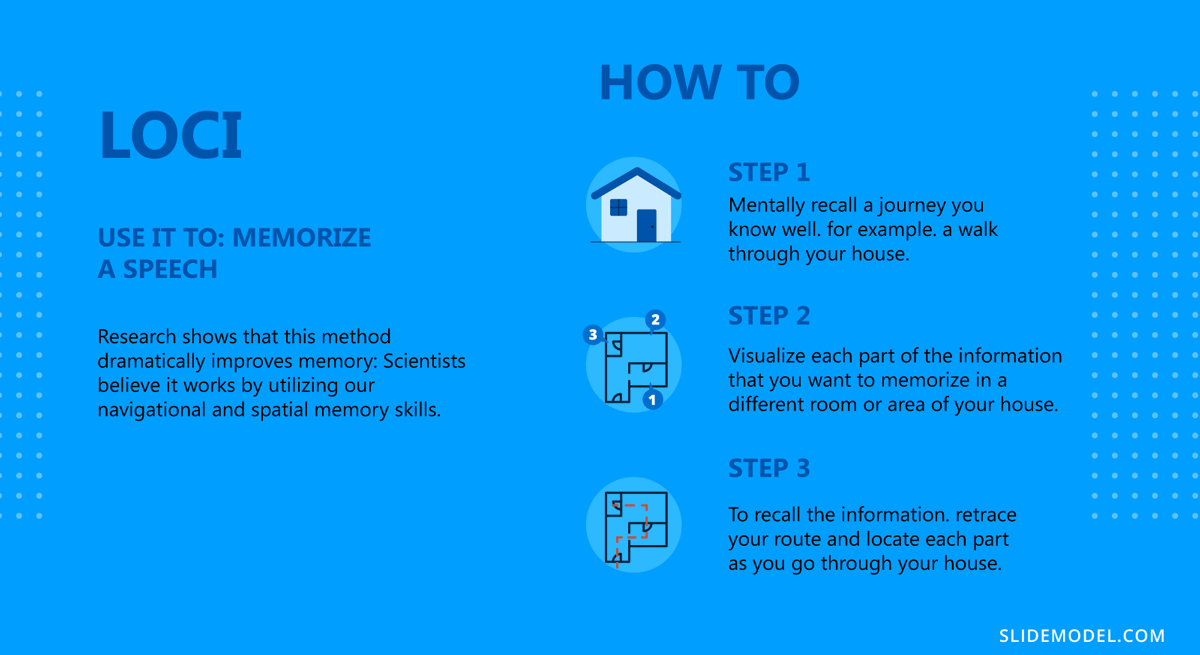

There are lots of tips out there about how to memorize speeches. Here’s one that loosely follows an ancient memorization strategy called the method of loci or “memory palace,” which uses visualizations of familiar spatial environments in order to enhance the recall of information.

You can view the transcript for “How to Memorize a Speech” here (opens in new window) .

An impromptu speech is one for which there is little to no preparation. There is often not a warning even that the person may be asked to speak. For example, your speech teacher may ask you to deliver a speech on your worst pet peeve. You may or may not be given a few minutes to organize your thoughts. What should you do? DO NOT PANIC. Even under pressure, you can create a basic speech that follows the formula of an introduction, body, and conclusion. If you have a few minutes, jot down some notes that fit into each part of the speech. (In fact, the phrase “speaking off the cuff,” which means speaking without preparation, probably refers to the idea that one would jot a few notes on one’s shirt cuff before speaking impromptu.) [1] ) An introduction should include an attention getter, introduction of the topic, speaker credibility, and forecasting of main points. The body should have two or three main points. The conclusion should have a summary, call to action, and final thought. If you can organize your thoughts into those three parts, you will sound like a polished speaker. Even if you only hit two of them, it will still help you to think about the speech in those parts. For example, if a speech is being given on a pet peeve of chewed gum being left under desks in classrooms, it might be organized like this.

- Introduction : Speaker chews gum loudly and then puts it under a desk (attention getter, demonstration). Speaker introduces themselves and the topic and why they’re qualified to speak on it (topic introduction and credibility). “I’m Katie Smith and I’ve been a student at this school for three years and witnessed this gum problem the entire time.”

- Body : Speaker states three main points of why we shouldn’t leave gum on desks: it’s rude, it makes custodians have to work harder, it affects the next student who gets nastiness on their seat (forecast of order). Speaker then discusses those three points

- Conclusion : Speaker summarizes those three points (summary, part 1 of conclusion), calls on the audience to pledge to never do this again (call to action), and gives a quote from Michael Jordan about respecting property (final thought).

While an impromptu speech can be challenging, the advantage is that it can also be thrilling as the speaker thinks off the cuff and says what they’re most passionate about in the moment. A speaker should not be afraid to use notes during an impromptu speech if they were given any time to organize their thoughts.

The disadvantage is that there is no time for preparation, so finding research to support claims such as quotes or facts cannot be included. The lack of preparation makes some speakers more nervous and they may struggle to engage the audience due to their nerves.

Extemporaneous

The last method of delivery we’ll look at is extemporaneous. When speaking extemporaneously, speakers prepare some notes in advance that help trigger their memory of what they planned to say. These notes are often placed on notecards. A 4”x6” notecard or 5”x7” size card works well. This size of notecards can be purchased at any office supply store. Speakers should determine what needs to go on each card by reading through their speech notes and giving themselves phrases to say out loud. These notes are not full sentences, but help the speakers, who turn them into a full sentence when spoken aloud. Note that if a quote is being used, listing that quote verbatim is fine.

The advantage of extemporaneous speaking is that the speakers are able to speak in a more conversational tone by letting the cards guide them, but not dictate every word they say. This method allows for the speakers to make more eye contact with the audience. The shorter note forms also prevent speakers from getting lost in their words. Numbering these cards also helps if one gets out of order. Also, these notes are not ones the teacher sees or collects. While you may be required to turn in your speech outline, your extemporaneous notecards are not seen by anyone but you. Therefore, you can also write yourself notes to speak up, slow down, emphasize a point, go to the next slide, etc.

The disadvantage to extemporaneous is the speakers may forget what else was planned to say or find a card to be out of order. This problem can be avoided through rehearsal and double-checking the note order before speaking.

Many speakers consider the extemporaneous method to be the ideal speaking method because it allows them to be prepared, keeps the audience engaged, and makes the speakers more natural in their delivery. In your public speaking class, most of your speeches will probably be delivered extemporaneously.

- As per the Oxford English Dictionary' s entry for "Off the Cuff." See an extensive discussion at Mark Liberman's Language Log here: https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4130 ↵

- Method of loci definition. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Method_of_loci . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The mistake that toppled the Berlin Wall. Provided by : Vox. Located at : https://youtu.be/Mn4VDwaV-oo . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- How to Memorize a Speech. Authored by : Memorize Academy. Located at : https://youtu.be/rvBw__VNrsc . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Address to the Nation. Provided by : U.S. National Archives. Located at : https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2011/09/06/911-an-address-to-the-nation/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Methods of Speech Delivery. Authored by : Misti Wills with Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

Speak Like a Pro: The Ultimate Guide to Flawless Speech Delivery Techniques Revealed!

Eloquence Everly

Affiliate Disclaimer

As an affiliate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases. We get commissions for purchases made through links on this website from Amazon and other third parties.

Implementing effective speech delivery techniques is essential to captivate and engage your audience. By following these techniques, you can improve your public speaking skills and deliver persuasive and engaging presentations.

Key Takeaways:

- Thoroughly prepare and practice your speech before delivering it.

- Create a distraction-free presentation environment with proper lighting and visibility.

- Pay attention to your personal appearance and maintain good body language during the speech.

- Focus on vocal delivery strategies such as clear enunciation , appropriate loudness and speed , and variations in speed and force .

- Utilize effective body language by maintaining eye contact , using gestures and movement naturally, and avoiding distracting mannerisms.

Preparation for Speech Delivery

Before delivering a speech, thorough preparation is essential. By taking the time to prepare, you can ensure a smooth and confident delivery that captivates your audience . Here are some key aspects to consider:

- Create a Well-Organized Set of Notes: To guide you during your presentation, create a clear and concise set of notes. This will help you stay on track and ensure you cover all your key points. Structure your notes in a logical manner, using headings and bullet points for easy reference.

- Engage in Ample Practice: Practice makes perfect, so dedicate time to rehearse your speech. Familiarize yourself with the content, flow, and timing of your presentation. Practice in front of a mirror, friends, or colleagues to receive feedback and make necessary improvements.

- Prepare the Presentation Environment : The environment in which you deliver your speech can greatly impact its effectiveness. Consider factors such as lighting, visibility, and distractions. Ensure that the room is well-lit and that your audience can see and hear you clearly. Eliminate any distractions or potential interruptions.

- Test and Have a Backup Plan for Audiovisual Equipment : If you will be using audiovisual equipment , such as a microphone or projector, it is crucial to test them beforehand. Check for any technical issues and have a backup plan in case of equipment failure. This will help you avoid any disruptions and allow for a seamless delivery.

By adequately preparing your speech, notes, and the presentation environment , you can set yourself up for success and deliver a confident and impactful presentation to your audience.

Personal Appearance and Body Language

When delivering a speech, your personal appearance and body language significantly impact the impression you make on your audience. Here are some key tips to ensure you project confidence and professionalism:

Dress Appropriately

Choose attire that is suitable for the occasion and reflects your respect for the audience and the topic. Ensure your outfit is clean, well-fitted, and comfortable. Avoid wearing hats or caps that can obstruct your face and hinder your nonverbal communication.

Maintain Good Posture

Stand or sit up straight, with your shoulders back and chin parallel to the ground. This posture exudes confidence and engages your audience . Remember to distribute your weight evenly and avoid excessive shifting or fidgeting.

Eye Contact

Maintaining eye contact is crucial for establishing connection and credibility with your audience. Look directly at individuals while speaking, making an effort to engage different parts of the room. Avoid constantly referring to notes or reading from a script, as this can diminish the impact of your message.

Avoid Distracting Mannerisms

Be mindful of your body language throughout your speech. Minimize excessive hand movements, pacing, or other distracting mannerisms that can detract from your message. Focus on conveying confidence and clarity through calm and composed gestures .

By paying attention to your personal appearance and body language, you can enhance your speech delivery and effectively engage your audience .

| Personal Appearance | Body Language |

|---|---|

| Choose appropriate attire | Maintain good posture |

| Ensure tidy hair | Maintain |

| Avoid obstructions to the face | Avoid distracting mannerisms |

Vocal Delivery Strategies

Your vocal delivery plays a crucial role in how your speech is received by the audience. By implementing effective vocal techniques, you can enhance the impact of your message and maintain audience attention. Let’s explore some strategies to improve your vocal delivery :

Enunciation and Clarity

Clear enunciation is vital for effective communication. Ensure that you pronounce your words distinctly and avoid mumbling or garbling. By articulating each word clearly, you enhance the audience’s understanding and engagement with your speech.

Appropriate Loudness and Speed

Adjusting your volume and speed based on the audience, venue, and topic is crucial for effective vocal delivery. Speak loudly enough to be heard, but avoid being overly loud or shouting. Similarly, vary your speed to maintain audience interest and emphasize key points, but avoid speaking too quickly or too slowly.

Variations in Speed, Inflections, and Force

Utilizing variations in speed, inflections, and force adds depth and meaning to your speech. By emphasizing certain words or phrases, you can convey the significance and emotion behind them. Adjusting the pace of your speech can create anticipation or highlight important information. Use this technique strategically to enhance your message and keep your audience engaged.

Minimize Filler Words

Filler words such as “um,” “uh,” and “like” can detract from the impact and clarity of your delivery. Minimize their use to ensure a smooth and impactful presentation. Pausing briefly instead of using filler words can also add emphasis and facilitate better understanding.

“Clear and confident vocal delivery is essential for engaging your audience. Enunciate your words with clarity, speak at an appropriate loudness and speed , utilize variations in speed and force , and minimize the use of filler words. These strategies will help you captivate your audience and effectively convey your message.”

Now that you have learned about effective vocal delivery strategies, let’s move on to exploring the importance of body language in speech delivery.

| Vocal Delivery Strategies | Description |

|---|---|

| and Clarity | Focus on pronouncing words clearly and avoiding mumbling or garbling. |

| Appropriate | Adjust your volume and speed based on the audience, venue, and topic. |

| Variations in Speed, Inflections, and Force | Utilize variations in speed, inflections, and force to enhance meaning and maintain audience attention. |

| Minimize Filler Words | Avoid using filler words like “um,” “uh,” and “like” to ensure a smooth and impactful delivery. |

Effective Use of Body Language

When delivering a speech, your body language can greatly impact how your message is received by the audience. By mastering the art of body language , you can effectively communicate your ideas and captivate your listeners.

Maintaining Eye Contact

One of the most important aspects of body language is maintaining eye contact with your audience. This establishes a connection between you and your listeners, making them feel engaged and involved in your speech. Avoid excessively reading from notes, as this can hinder eye contact and create a barrier between you and your audience. Instead, glance at your notes discreetly when necessary and focus on making eye contact with individuals throughout the room.

Using Gestures and Movement

“Gestures, in my opinion, are the most powerful tool we have in becoming an effective communicator.” – Andrea Foy

Gestures and movement can add depth and emphasis to your speech. Use them naturally to illustrate concepts, reinforce transitions between ideas, and highlight key points. However, it’s important to be mindful of using gestures in a controlled and purposeful manner. Avoid excessive or distracting movements that can draw attention away from your message. Instead, use gestures and movement to enhance your delivery and engage your audience.

Show Enthusiasm and Commitment

When delivering a speech, it’s vital to demonstrate interest and passion in your topic. Show enthusiasm through your body language, such as by smiling, using facial expressions that reflect your emotions, and maintaining an open and confident posture. This not only captures the audience’s attention but also conveys your commitment to the subject matter, making your speech more compelling and memorable.

Avoiding Distracting Mannerisms

While gestures and movement are important, it’s crucial to avoid distracting or aimless mannerisms that can detract from your message. Be aware of any nervous habits, such as fidgeting, excessive hand movements, or aimless shifting of weight. These mannerisms can undermine your credibility and divert the audience’s attention from your speech. Practice self-awareness and aim for body language that is purposeful, controlled, and complementary to your message.

| Effective Use of Body Language | Tips |

|---|---|

| Maintain eye contact | Establishes connection and engagement |

| Use gestures and naturally | Illustrate concepts and emphasize key points |

| Show enthusiasm and commitment | Captivate the audience and enhance delivery |

| Avoid distracting mannerisms | Stay focused and maintain credibility |

Improving Verbal Delivery

When delivering a speech, your verbal delivery plays a crucial role in engaging your audience. To ensure your message reaches every corner of the room, focus on the following aspects:

- Projection : Speak with enough volume to reach people in the back of the room. This will ensure clear communication and prevent your words from getting lost in the space.

- Comfortable Rate : Speak at a pace that allows your audience to comprehend and absorb your message. Pausing occasionally not only helps you catch your breath but also gives the listeners time to process the information.

- Clear Articulation : Enunciate your words clearly to facilitate understanding. Avoid mumbling or rushing through your sentences, as this can make it difficult for your audience to follow along.

- Vocal Habits : Pay attention to any vocal habits that may distract your listeners. Eliminate vocalized pauses like “um” or “uh” and work on maintaining a steady volume throughout your speech. Avoid speaking more softly at the end of sentences, as it can diminish the impact of your message.

Sample Table: Comparing Verbal Delivery Techniques

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Ensures clear communication Reaches all audience members | May require practice to master Risk of being perceived as overly loud | |

| Facilitates audience comprehension Gives time for information processing | Requires conscious effort May need adjusting for different audience sizes | |

| Enhances understanding of message Conveys professionalism | May require practice and feedback Risk of sounding unnatural if overemphasized | |

| Reduces distractions Maintains consistent delivery | Challenging to identify and correct Requires self-awareness and practice |

By focusing on projection , comfortable rate , clear articulation , and eliminating distracting vocal habits , you can deliver a speech that captivates your audience and ensures effective communication.

Enhancing Nonverbal Delivery

Nonverbal delivery plays a crucial role in enhancing your overall speech delivery and making a lasting impact on your audience. By utilizing effective eye contact, movement , gestures, and an unobtrusive use of notes , you can captivate and engage your listeners. These nonverbal elements add depth and authenticity to your speech, helping to convey your message effectively.

Eye Contact: Making eye contact with individuals in your audience establishes a connection and shows that you are genuinely interested in their presence. Avoid excessive reading from notes, as it can break the eye contact and lessen your impact. Instead, actively engage with your audience, scanning the room and making meaningful eye contact with different individuals throughout your speech.

Movement: Movement on stage or in front of your audience can help you control nervousness and create visual interest. Utilize the space around you, taking purposeful steps and making slight changes in position to capture the attention of your listeners. Movement should be natural and deliberate, enhancing your message rather than distracting from it.

Gestures: Gestures and arm movements can add emphasis and clarify your spoken words. Use them to reinforce key points, illustrate concepts, and enhance the overall impact of your speech. Effective gestures appear natural and are synchronized with the rhythm and flow of your speech, engaging your audience on a visual level and reinforcing the meaning of your words.

Unobtrusive Use of Notes: While it is common to use notes during a speech to stay on track and remember important points, it is essential to use them unobtrusively. Ensure that your notes are legible and well-organized, allowing you to find the information you need without causing distractions. Place your notes discreetly or use a small podium or lectern to hold them, allowing for seamless transitions and maintaining the focus on your delivery.

Avoid any distracting mannerisms or gestures that detract from your communication. Practice incorporating these nonverbal elements into your delivery to create a powerful and engaging speech that leaves a lasting impression on your audience.

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Eye Contact | Establishes connection and engagement with the audience; avoids excessive reading from notes. |

| Movement | Controls nervousness and creates visual interest; uses purposeful steps and slight changes in position. |

| Gestures | Adds emphasis and clarifies spoken words; reinforces key points and engages the audience on a visual level. |

| Allows for staying on track and remembering important points without causing distractions; ensures legibility and organization. |

Managing Nervousness and Overcoming Challenges

Nervousness is a common experience when delivering a speech. However, it’s important to remember that you are not alone in feeling this way. Chances are, many members of your audience are also experiencing nerves. The good news is that most signs of nervousness are invisible to the audience, so you can stay calm and composed even if you’re feeling a bit jittery.

Embrace nervousness as it can actually be a valuable tool in enhancing your speech delivery. It can make you more alert, animated, and enthusiastic about your topic. Instead of trying to suppress it, harness that nervous energy and channel it into your presentation. When you embrace your nerves, you can turn them into a positive force that adds authenticity and passion to your speech.

Handling mistakes is another important aspect of managing nervousness . It’s natural to feel flustered if you make a mistake or lose your place during your speech. However, it’s crucial to remember that these slip-ups happen to everyone at some point. Instead of panicking, take a moment to collect yourself, take a deep breath, and calmly continue from where you left off. Most importantly, don’t dwell on the mistake or draw attention to it. Keep your focus on delivering your message effectively.

By embracing and managing nervousness , you can transform it from a potential obstacle into a catalyst for a powerful and engaging presentation. Embrace the nerves, handle mistakes gracefully, and let your genuine enthusiasm shine through.

Mastering effective speech delivery techniques is essential for becoming a confident and persuasive speaker. By implementing these techniques, such as thorough preparation, proper personal appearance, and effective vocal and nonverbal delivery strategies, you can captivate your audience and deliver impactful presentations.

Preparing well before your speech, organizing your notes, and creating a suitable environment are all crucial steps in ensuring an effective delivery. Your personal appearance and body language contribute greatly to the overall impression you make on your audience. Maintaining eye contact, using gestures and movement, and speaking with clear articulation and appropriate variations in speed and force all enhance your communication.

While it is natural to feel nervous before delivering a speech, embracing this nervousness can actually help enhance your delivery. Remember, you are not alone in experiencing nerves, and most signs of nervousness are invisible to the audience. Embrace the energy that nerves bring and use it to your advantage, channeling it into a more animated and enthusiastic performance.

By following these effective speech delivery techniques, you can confidently communicate your ideas and engage your audience in a persuasive and impactful manner. Remember to always strive for clear and effective communication, and never hesitate to seek further opportunities for growth and improvement in your public speaking skills .

What are some effective speech delivery techniques?

Implementing effective speech delivery techniques involves thorough preparation, proper personal appearance, vocal and nonverbal delivery strategies, and managing nervousness .

How important is speech preparation for effective delivery?

Speech preparation is crucial for effective delivery. Creating well-organized notes, practicing, and preparing the presentation environment and audiovisual equipment are essential steps.

How does personal appearance and body language impact speech delivery?

Personal appearance, such as appropriate dressing and tidy hair, and positive body language help to engage the audience. Standing or sitting up straight, making eye contact, and avoiding distracting mannerisms are key aspects.

What are some vocal delivery strategies for effective speech delivery?

Enunciating clearly, speaking with appropriate loudness and speed, using variations in speed and inflections, and minimizing filler words are important strategies for vocal delivery.

How can body language enhance speech delivery?

Maintaining eye contact, using gestures and movement naturally, and displaying enthusiasm through body language can enhance the impact of your speech.

What are some tips for improving verbal delivery in a speech?

Projecting your voice, speaking at a comfortable rate, articulating words clearly, and eliminating vocal habits are key tips to improve verbal delivery.

How can nonverbal delivery support speech delivery?

Making eye contact with the audience, using movement and gestures, and using notes unobtrusively can make your speech more engaging and effective.

How can one manage nervousness during speech delivery?

Managing nervousness can be achieved by realizing that it’s common, remaining calm and composed, using nervous energy to enhance your delivery, and embracing mistakes as learning opportunities.

What are the key takeaways for effective speech delivery?

By implementing effective speech delivery techniques , one can become a confident and persuasive speaker. Thorough preparation, proper personal appearance, vocal and nonverbal delivery strategies, and managing nervousness are key components.

Written By Eloquence Everly

We may earn a commission if you click on the links within this article. Learn more.

Latest Posts

What is the future of AI in communication?

The Worldcom Confidence Index (WCI) tells us AI is big in business conversations. It’s listed in the top four topics that get the most attention from top executives around the world. However, by January 2024, confidence in AI technology had […]

How Will We Communicate in 2050? Future Communication

Children and adults in Britain are predicting big changes in how we talk. By 2049, most people might be using body implants, holograms. A YouGov survey discovered that only 13% of kids and teens believe we’ll keep sending letters. I […]

The Future of Communication Technology: What to Expect

Digital communication is changing fast because of how people interact and their preferences. With the rise of in-app messaging, its use is getting bigger. Even though in-app messaging is becoming more popular than SMS, virtual reality is slower to catch […]

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: Presenting Your Speech Module

Techniques for Effective Delivery

Use of your body.

As you stand before an audience, be confident and be yourself. Remember, you planned for this speech, you prepared well, and you practiced so that you know the material you will present. You are probably the expert in the room on this subject. If not, why are you the one making the presentation?

You need to consider not only what you say, but also how your body will support you and your words. When your actions are wedded to your words, the impact of your speech will be strengthened. If your platform behavior includes mannerisms unrelated to your spoken message, those actions will call attention to themselves and away from your speech.

Here are five areas on which to focus as you plan, practice, and present:

- Gripping or leaning on the lectern

- Finger tapping

- Lip biting or licking

- Toying with a pen or jewelry

- Adjusting hair or clothing

- Chewing gum

- Head wagging

These all have two things in common: They are physical manifestations of simple nervousness and they are performed unconsciously. When you make a verbal mistake, you can easily correct it, because you can hear your own words. However, you cannot see yourself, so most distracting mannerisms go uncorrected. You cannot eliminate distractions unless you know they exist.

The first step in self-improvement is to learn what you want to change. In speech preparation, nothing is as revealing as a video of your self. The first step in eliminating any superfluous behavior is to obtain an accurate picture of your body’s image while speaking. This should include:

- Body movement

- Facial expressions

- Eye contact

- 2. Build Self-Confidence by Being Yourself: The most important rule for making your body communicate effectively is to be yourself. The emphasis should be on the sharing of ideas, not on the performance. Strive to be as genuine and natural as you are when you speak to family members and friends.Many people say, “I’m okay in a small group, but when I get in front of a larger group I freeze. ” The only difference between speaking to a small informal group and to a sizable audience is the number of listeners. To compensate for this, you need only to amplify your natural behavior. Be authentically yourself, but amplify your movements and expressions just enough so that the audience can see them.

- 4. Build Self-confidence through Preparation: Nothing influences a speaker’s mental attitude more than the knowledge that s/he is thoroughly prepared. This knowledge leads to self- confidence, which is a vital ingredient of effective public speaking.How many of us have ever experienced a situation in which we had not prepared well for a presentation? How did we come across? On the other hand, think of those presentations that did go well. These are the ones for which we were properly prepared.

Facial Expressions

Leave that deadpan expression to poker players. A speaker realizes that appropriate facial expressions are an important part of effective communication. In fact, facial expressions are often the key determinant of the meaning behind the message. People watch a speaker’s face during a presentation. When you speak, your face -more clearly than any other part of your body -communicates to others your attitudes, feelings, and emotions.

Remove expressions that do not belong on your face. Inappropriate expressions include distracting mannerisms or unconscious expressions not rooted in your feelings, attitudes, and emotions. In much the same way that some speakers perform random, distracting gestures and body movements, nervous speakers often release excess energy and tension by unconsciously moving their facial muscles (e.g., licking lips, tightening the jaw).

One type of unconscious facial movement which is less apt to be read clearly by an audience is involuntary frowning. This type of frowning occurs when a speaker attempts to deliver a memorized speech. There are no rules governing the use of specific expressions. If you relax your inhibitions and allow yourself to respond naturally to your thoughts, attitudes, and emotions, your facial expressions will be appropriate and will project sincerity, conviction, and credibility.

Eye Contact

Eye contact is the cement that binds together speakers and their audiences. When you speak, your eyes involve your listeners in your presentation. Jan Costagnaro says, “When you maintain eye contact, you present an air of confidence in yourself and what you are communicating. People who are listening to what you are saying will take you more seriously, and will take what you say as important. If you lose eye contact or focus on everything else but the person(s) you are speaking to, you may not be taken seriously and the truth in your points may be lost. ” There is no surer way to break a communication bond between you and the audience than by failing to look at your listeners. No matter how large your audience may be, each listener wants to feel that you are speaking directly to him/her.

The adage, “The eyes are the mirror of the soul, ” underlines the need for you to convince people with your eyes, as well as your words. Only by looking at your listeners as individuals can you convince them that you are sincere and are interested in them and that you care whether they accept your message. When you speak, your eyes also function as a control device you can use to ensure the audience’s attentiveness and concentration.

Eye contact can also help to overcome nervousness by making your audience a known quantity. Effective eye contact is an important feedback device that makes the speaking situation a two-way communication process. By looking at your audience, you can determine how they are reacting.

When you develop the ability to gauge the audience’s reactions and adjust your presentation accordingly, you will be a much more effective speaker. The following supporting tips will help you be more confident and improve your ability to make eye contact:

Know your material. Know the material so well that you do not have to devote your mental energy to the task of remembering the sequence of ideas and words.

Prepare well and rehearse enough so that you do not have to depend too heavily on notes. Many speakers, no matter how well prepared, need at least a few notes to deliver their message. If you can speak effectively without notes, by all means do so. But if you choose to use notes, they should be only a delivery outline, using key words. Notes are not a substitute for preparation and practice.

Establish a personal bond with listeners. Begin by selecting one person and talking to him/ her personally. Maintain eye contact with that person long enough to establish a visual bond (about five to ten seconds). This is usually the equivalent of a sentence or a thought. Then shift your gaze to another person. In a small group, this is relatively easy to do. But, if you are addressing hundreds or thousands of people, it is impossible. What you can do is pick out one or two individuals in each section of the room and establish personal bonds. Then, each listener will get the impression you are talking directly to him/her.

Monitor visual feedback. While you are talking, your listeners are responding with their own nonverbal messages. Use your eyes to actively seek out this valuable feedback. If individuals aren’t looking at you, they may not be listening either. Make sure they can hear you. Then work to actively engage them.

Your Appearance Matters

Multiple studies have has shown that appearance influences everything from employment to social status. Whether we like to admit it or not, ours is a culture obsessed with appearance. Attractive people are more likely to get the job, get the promotion, and get the girl (or guy). Bonnie Berry’s 2008 research on physical appearance also shows that communicator attractiveness influences how an audience perceives the credibility of the speaker. Overall, more attractive speakers were thought to be more credible (51).

So what does that mean for you as you prepare for a speech? Bottom line: Make an effort. If your listeners will have on suits and dresses, wear your best suit or dress -the outfit that brings you the most compliments. Make sure that every item of clothing is clean and well tailored. Certainly a speaker who appears unkempt gives the impression to the audience that s/he doesn’t really care, and that’s not the first impression that you want to send to your listeners.

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

Complete Guide for Effective Presentations, with Examples

July 9, 2018 - Dom Barnard

During a presentation you aim to look confident, enthusiastic and natural. You’ll need more than good words and content to achieve this – your delivery plays a significant part. In this article, we discuss various techniques that can be used to deliver an effective presentation.

Effective presentations

Think about if you were in the audience, what would:

- Get you to focus and listen

- Make you understand

- Activate your imagination

- Persuade you

Providing the audience with interesting information is not enough to achieve these aims – you need to ensure that the way you present is stimulating and engaging. If it’s not, you’ll lose the audience’s interest and they’ll stop listening.

Tips for an Effective Presentation

Professional public speakers spend hours creating and practicing presentations. These are the delivery techniques they consider:

Keep it simple

You shouldn’t overwhelm your audience with information – ensure that you’re clear, concise and that you get to the point so they can understand your message.

Have a maximum of three main points and state them at the beginning, before you explain them in more depth, and then state them at the end so the audience will at least remember these points.

If some of your content doesn’t contribute to your key message then cut it out. Also avoid using too many statistics and technical terminology.

Connect with your audience

One of the greatest difficulties when delivering a presentation is connecting with the audience. If you don’t connect with them it will seem as though you’re talking to an empty room.

Trying to make contact with the audience makes them feel like they’re part of the presentation which encourages them to listen and it shows that you want to speak to them.

Eye contact and smile

Avoiding eye contact is uncomfortable because it make you look insecure. When you maintain eye contact the audience feels like you’re speaking to them personally. If this is something you struggle with, try looking at people’s foreheads as it gives the impression of making eye contact.

Try to cover all sections of the audience and don’t move on to the next person too quickly as you will look nervous.

Smiling also helps with rapport and it reduces your nerves because you’ll feel less like you’re talking to group of faceless people. Make sure you don’t turn the lights down too much before your presentation so you can all clearly see each other.

Body language

Be aware of your body language and use it to connect:

- Keep your arms uncrossed so your body language is more open .

- Match your facial expressions with what you’re saying.

- Avoid fidgeting and displaying nervous habits, such as, rocking on your feet.

- You may need to glance at the computer slide or a visual aid but make sure you predominantly face the audience.

- Emphasise points by using hand gestures but use them sparingly – too little and they’ll awkwardly sit at your side, too much and you’ll be distracting and look nervous.

- Vary your gestures so you don’t look robotic.

- Maintain a straight posture.

- Be aware of cultural differences .

Move around

Avoid standing behind the lectern or computer because you need to reduce the distance and barriers between yourself and the audience. Use movement to increase the audience’s interest and make it easier to follow your presentation.

A common technique for incorporating movement into your presentation is to:

- Start your introduction by standing in the centre of the stage.

- For your first point you stand on the left side of the stage.

- You discuss your second point from the centre again.

- You stand on the right side of the stage for your third point.

- The conclusion occurs in the centre.

Watch 3 examples of good and bad movement while presenting

Example: Movement while presenting

Your movement at the front of the class and amongst the listeners can help with engagement. Think about which of these three speakers maintains the attention of their audience for longer, and what they are doing differently to each other.

Speak with the audience

You can conduct polls using your audience or ask questions to make them think and feel invested in your presentation. There are three different types of questions:

Direct questions require an answer: “What would you do in this situation?” These are mentally stimulating for the audience. You can pass a microphone around and let the audience come to your desired solution.

Rhetorical questions do not require answers, they are often used to emphasises an idea or point: “Is the Pope catholic?

Loaded questions contain an unjustified assumption made to prompt the audience into providing a particular answer which you can then correct to support your point: You may ask “Why does your wonderful company have such a low incidence of mental health problems?” The audience will generally answer that they’re happy.

After receiving the answers you could then say “Actually it’s because people are still unwilling and too embarrassed to seek help for mental health issues at work etc.”

Be specific with your language

Make the audience feel as though you are speaking to each member individually by using “you” and “your.”

For example: asking “Do you want to lose weight without feeling hungry?” would be more effective than asking “Does anyone here want to lost weight without feeling hungry?” when delivering your presentation. You can also increase solidarity by using “we”, “us” etc – it makes the audience think “we’re in this together”.

Be flexible

Be prepared to adapt to the situation at the time, for example, if the audience seems bored you can omit details and go through the material faster, if they are confused then you will need to come up with more examples on the spot for clarification. This doesn’t mean that you weren’t prepared because you can’t predict everything.

Vocal variety

How you say something is just as is important as the content of your speech – arguably, more so.

For example, if an individual presented on a topic very enthusiastically the audience would probably enjoy this compared to someone who covered more points but mumbled into their notes.

- Adapt your voice depending on what are you’re saying – if you want to highlight something then raise your voice or lower it for intensity. Communicate emotion by using your voice.

- Avoid speaking in monotone as you will look uninterested and the audience will lose interest.

- Take time to pronounce every word carefully.

- Raise your pitch when asking questions and lower it when you want to sound severe.

- Sound enthusiastic – the more you sound like you care about the topic, the more the audience will listen. Smiling and pace can help with this.

- Speak loudly and clearly – think about projecting your voice to the back of the room.

- Speak at a pace that’s easy to follow . If you’re too fast or too slow it will be difficult for the audience to understand what you’re saying and it’s also frustrating. Subtly fasten the pace to show enthusiasm and slow down for emphasis, thoughtfulness or caution.

Prior to the presentation, ensure that you prepare your vocal chords :

- You could read aloud a book that requires vocal variety, such as, a children’s book.

- Avoid dairy and eating or drinking anything too sugary beforehand as mucus can build-up leading to frequent throat clearing.

- Don’t drink anything too cold before you present as this can constrict your throat which affects vocal quality.

- Some people suggest a warm cup of tea beforehand to relax the throat.

Practice Presentation Skills

Improve your public speaking and presentation skills by practicing them in realistic environments, with automated feedback on performance. Learn More

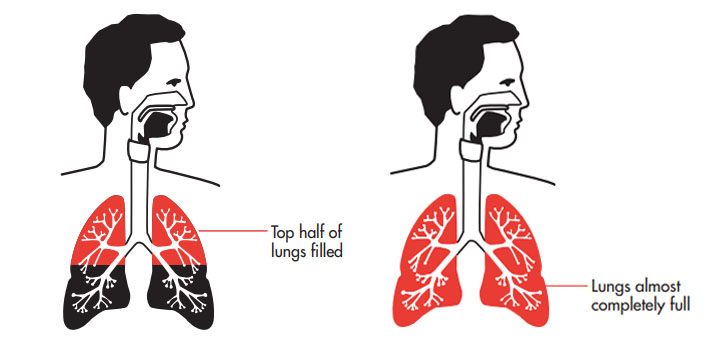

Pause to breathe

When you’re anxious your breathing will become quick and shallow which will affect the control you have on your voice. This can consequently make you feel more nervous. You want to breathe steadily and deeply so before you start speaking take some deep breaths or implement controlled breathing.

Controlled breathing is a common technique that helps slow down your breathing to normal thus reducing your anxiety. If you think this may be useful practice with these steps:

- Sit down in an upright position as it easier for your lungs to fill with air

- Breathe in through your nose and into your abdomen for four seconds

- Hold this breathe for two seconds

- Breathe out through your nose for six seconds

- Wait a few seconds before inhaling and repeating the cycle

It takes practice to master this technique but once you get used to it you may want to implement it directly before your presentation.

Completely filling your lungs during a pause will ensure you reach a greater vocal range.

During the presentation delivery, if you notice that you’re speaking too quickly then pause and breathe. This won’t look strange – it will appear as though you’re giving thought to what you’re saying. You can also strategically plan some of your pauses, such as after questions and at the end of sections, because this will give you a chance to calm down and it will also give the audience an opportunity to think and reflect.

Pausing will also help you avoid filler words , such as, “um” as well which can make you sound unsure.

- 10 Effective Ways to use Pauses in your Speech

Strong opening

The first five minutes are vital to engage the audience and get them listening to you. You could start with a story to highlight why your topic is significant.

For example, if the topic is on the benefits of pets on physical and psychological health, you could present a story or a study about an individual whose quality of life significantly improved after being given a dog. The audience is more likely to respond better to this and remember this story than a list of facts.

Example: Which presentation intro keeps you engaged?

Watch 5 different presentation introductions, from both virtual and in-person events. Notice how it can only take a few seconds to decide if you want to keep listening or switch off. For the good introductions, what about them keeps you engaged?

More experienced and confident public speakers use humour in their presentations. The audience will be incredibly engaged if you make them laugh but caution must be exercised when using humour because a joke can be misinterpreted and even offend the audience.

Only use jokes if you’re confident with this technique, it has been successful in the past and it’s suitable for the situation.

Stories and anecdotes

Use stories whenever you can and judge whether you can tell a story about yourself because the audience are even more interested in seeing the human side of you.

Consider telling a story about a mistake you made, for example, perhaps you froze up during an important presentation when you were 25, or maybe life wasn’t going well for you in the past – if relevant to your presentation’s aim. People will relate to this as we have all experienced mistakes and failures. The more the audience relates to you, the more likely they will remain engaged.

These stories can also be told in a humorous way if it makes you feel more comfortable and because you’re disclosing a personal story there is less chance of misinterpretation compared to telling a joke.

Anecdotes are especially valuable for your introduction and between different sections of the presentation because they engage the audience. Ensure that you plan the stories thoroughly beforehand and that they are not too long.

Focus on the audience’s needs

Even though your aim is to persuade the audience, they must also get something helpful from the presentation. Provide the audience with value by giving them useful information, tactics, tips etc. They’re more likely to warm to you and trust you if you’re sharing valuable information with them.

You could also highlight their pain point. For example, you might ask “Have you found it difficult to stick to a healthy diet?” The audience will now want to remain engaged because they want to know the solution and the opportunities that you’re offering.

Use visual aids

Visual aids are items of a visual manner, such as graphs, photographs, video clips etc used in addition to spoken information. Visual aids are chosen depending on their purpose, for example, you may want to:

- Summarise information.

- Reduce the amount of spoken words, for example, you may show a graph of your results rather than reading them out.

- Clarify and show examples.

- Create more of an impact. You must consider what type of impact you want to make beforehand – do you want the audience to be sad, happy, angry etc?

- Emphasise what you’re saying.

- Make a point memorable.

- Enhance your credibility.

- Engage the audience and maintain their interest.

- Make something easier for the audience to understand.

Some general tips for using visual aids :

- Think about how can a visual aid can support your message. What do you want the audience to do?

- Ensure that your visual aid follows what you’re saying or this will confuse the audience.

- Avoid cluttering the image as it may look messy and unclear.

- Visual aids must be clear, concise and of a high quality.

- Keep the style consistent, such as, the same font, colours, positions etc

- Use graphs and charts to present data.

- The audience should not be trying to read and listen at the same time – use visual aids to highlight your points.

- One message per visual aid, for example, on a slide there should only be one key point.

- Use visual aids in moderation – they are additions meant to emphasise and support main points.

- Ensure that your presentation still works without your visual aids in case of technical problems.

10-20-30 slideshow rule

Slideshows are widely used for presentations because it’s easy to create attractive and professional presentations using them. Guy Kawasaki, an entrepreneur and author, suggests that slideshows should follow a 10-20-30 rule :

- There should be a maximum of 10 slides – people rarely remember more than one concept afterwards so there’s no point overwhelming them with unnecessary information.

- The presentation should last no longer than 20 minutes as this will leave time for questions and discussion.

- The font size should be a minimum of 30pt because the audience reads faster than you talk so less information on the slides means that there is less chance of the audience being distracted.

If you want to give the audience more information you can provide them with partially completed handouts or give them the handouts after you’ve delivered the presentation.

Keep a drink nearby

Have something to drink when you’re on stage, preferably water at room temperature. This will help maintain your vocal quality and having a sip is a subtle way of introducing pauses.

Practice, practice, practice

If you are very familiar with the content of your presentation, your audience will perceive you as confident and you’ll be more persuasive.

- Don’t just read the presentation through – practice everything, including your transitions and using your visual aids.

- Stand up and speak it aloud, in an engaging manner, as though you were presenting to an audience.

- Ensure that you practice your body language and gesturing.

- Use VR to practice in a realistic environment .

- Practice in front of others and get their feedback.

- Freely improvise so you’ll sound more natural on the day. Don’t learn your presentation verbatim because you will sound uninterested and if you lose focus then you may forget everything.

- Create cards to use as cues – one card should be used for one key idea. Write down brief notes or key words and ensure that the cards are physically connected so the order cannot be lost. Visual prompts can also be used as cues.

This video shows how you can practice presentations in virtual reality. See our VR training courses .

Two courses where you can practice your presentations in interactive exercises:

- Essential Public Speaking

- How to Present over Video

Try these different presentation delivery methods to see which ones you prefer and which need to be improved. The most important factor is to feel comfortable during the presentation as the delivery is likely to be better.

Remember that the audience are generally on your side – they want you to do well so present with confidence.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

14.4 Practicing for Successful Speech Delivery

Learning objectives.

- Explain why having a strong conversational quality is important for effective public speaking.

- Explain the importance of eye contact in public speaking.

- Define vocalics and differentiate among the different factors of vocalics.

- Explain effective physical manipulation during a speech.

- Understand how to practice effectively for good speech delivery.

Christian Pierret – Speech – CC BY 2.0.

There is no foolproof recipe for good delivery. Each of us is unique, and we each embody different experiences and interests. This means each person has an approach, or a style, that is effective for her or him. This further means that anxiety can accompany even the most carefully researched and interesting message. Even when we know our messages are strong and well-articulated on paper, it is difficult to know for sure that our presentation will also be good.

We are still obligated to do our best out of respect for the audience and their needs. Fortunately, there are some tools that can be helpful to you even the very first time you present a speech. You will continue developing your skills each time you put them to use and can experiment to find out which combination of delivery elements is most effective for you.

What Is Good Delivery?

The more you care about your topic, the greater your motivation to present it well. Good delivery is a process of presenting a clear, coherent message in an interesting way. Communication scholar Stephen E. Lucas tells us:

Good delivery…conveys the speaker’s ideas clearly, interestingly, and without distracting the audience. Most audiences prefer delivery that combines a certain degree of formality with the best attributes of good conversation—directness, spontaneity, animation, vocal and facial expressiveness, and a lively sense of communication (Lucas, 2009).

Many writers on the nonverbal aspects of delivery have cited the findings of psychologist Albert Mehrabian, asserting that the bulk of an audience’s understanding of your message is based on nonverbal communication. Specifically, Mehrabian is often credited with finding that when audiences decoded a speaker’s meaning, the speaker’s face conveyed 55 percent of the information, the vocalics conveyed 38 percent, and the words conveyed just 7 percent (Mehrabian, 1972). Although numerous scholars, including Mehrabian himself, have stated that his findings are often misinterpreted (Mitchell), scholars and speech instructors do agree that nonverbal communication and speech delivery are extremely important to effective public speaking.

In this section of the chapter, we will explain six elements of good delivery: conversational style, conversational quality, eye contact, vocalics, physical manipulation, and variety. And since delivery is only as good as the practice that goes into it, we conclude with some tips for effective use of your practice time.

Conversational Style

Conversational style is a speaker’s ability to sound expressive and to be perceived by the audience as natural. It’s a style that approaches the way you normally express yourself in a much smaller group than your classroom audience. This means that you want to avoid having your presentation come across as didactic or overly exaggerated. You might not feel natural while you’re using a conversational style, but for the sake of audience preference and receptiveness, you should do your best to appear natural. It might be helpful to remember that the two most important elements of the speech are the message and the audience. You are the conduit with the important role of putting the two together in an effective way. Your audience should be thinking about the message, not the delivery.

Stephen E. Lucas defines conversational quality as the idea that “no matter how many times a speech has been rehearsed, it still sounds spontaneous” [emphasis in original] (Lucas, 2009). No one wants to hear a speech that is so well rehearsed that it sounds fake or robotic. One of the hardest parts of public speaking is rehearsing to the point where it can appear to your audience that the thoughts are magically coming to you while you’re speaking, but in reality you’ve spent a great deal of time thinking through each idea. When you can sound conversational, people pay attention.

Eye Contact

Eye contact is a speaker’s ability to have visual contact with everyone in the audience. Your audience should feel that you’re speaking to them, not simply uttering main and supporting points. If you are new to public speaking, you may find it intimidating to look audience members in the eye, but if you think about speakers you have seen who did not maintain eye contact, you’ll realize why this aspect of speech delivery is important. Without eye contact, the audience begins to feel invisible and unimportant, as if the speaker is just speaking to hear her or his own voice. Eye contact lets your audience feel that your attention is on them, not solely on the cards in front of you.

Sustained eye contact with your audience is one of the most important tools toward effective delivery. O’Hair, Stewart, and Rubenstein note that eye contact is mandatory for speakers to establish a good relationship with an audience (O’Hair, Stewart, & Rubenstein, 2001). Whether a speaker is speaking before a group of five or five hundred, the appearance of eye contact is an important way to bring an audience into your speech.

Eye contact can be a powerful tool. It is not simply a sign of sincerity, a sign of being well prepared and knowledgeable, or a sign of confidence; it also has the power to convey meanings. Arthur Koch tells us that all facial expressions “can communicate a wide range of emotions, including sadness, compassion, concern, anger, annoyance, fear, joy, and happiness” (Koch, 2010).

If you find the gaze of your audience too intimidating, you might feel tempted to resort to “faking” eye contact with them by looking at the wall just above their heads or by sweeping your gaze around the room instead of making actual eye contact with individuals in your audience until it becomes easier to provide real contact. The problem with fake eye contact is that it tends to look mechanical. Another problem with fake attention is that you lose the opportunity to assess the audience’s understanding of your message. Still, fake eye contact is somewhat better than gripping your cards and staring at them and only occasionally glancing quickly and shallowly at the audience.

This is not to say that you may never look at your notecards. On the contrary, one of the skills in extemporaneous speaking is the ability to alternate one’s gaze between the audience and one’s notes. Rehearsing your presentation in front of a few friends should help you develop the ability to maintain eye contact with your audience while referring to your notes. When you are giving a speech that is well prepared and well rehearsed, you will only need to look at your notes occasionally. This is an ability that will develop even further with practice. Your public speaking course is your best chance to get that practice.

Effective Use of Vocalics

Vocalics , also known as paralanguage, is the subfield of nonverbal communication that examines how we use our voices to communicate orally. This means that you speak loudly enough for all audience members (even those in the back of the room) to hear you clearly, and that you enunciate clearly enough to be understood by all audience members (even those who may have a hearing impairment or who may be English-language learners). If you tend to be soft-spoken, you will need to practice using a louder volume level that may feel unnatural to you at first. For all speakers, good vocalic technique is best achieved by facing the audience with your chin up and your eyes away from your notecards and by setting your voice at a moderate speed. Effective use of vocalics also means that you make use of appropriate pitch, pauses, vocal variety, and correct pronunciation.

If you are an English-language learner and feel apprehensive about giving a speech in English, there are two things to remember: first, you can meet with a reference librarian to learn the correct pronunciations of any English words you are unsure of; and second, the fact that you have an accent means you speak more languages than most Americans, which is an accomplishment to be proud of.

If you are one of the many people with a stutter or other speech challenge, you undoubtedly already know that there are numerous techniques for reducing stuttering and improving speech fluency and that there is no one agreed-upon “cure.” The Academy Award–winning movie The King’s Speech did much to increase public awareness of what a person with a stutter goes through when it comes to public speaking. It also prompted some well-known individuals who stutter, such as television news reporter John Stossel, to go public about their stuttering (Stossel, 2011). If you have decided to study public speaking in spite of a speech challenge, we commend you for your efforts and encourage you to work with your speech instructor to make whatever adaptations work best for you.

Volume refers to the loudness or softness of a speaker’s voice. As mentioned, public speakers need to speak loudly enough to be heard by everyone in the audience. In addition, volume is often needed to overcome ambient noise, such as the hum of an air conditioner or the dull roar of traffic passing by. In addition, you can use volume strategically to emphasize the most important points in your speech. Select these points carefully; if you emphasize everything, nothing will seem important. You also want to be sure to adjust your volume to the physical setting of the presentation. If you are in a large auditorium and your audience is several yards away, you will need to speak louder. If you are in a smaller space, with the audience a few feet away, you want to avoid overwhelming your audience with shouting or speaking too loudly.