Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

About half of Americans say public K-12 education is going in the wrong direction

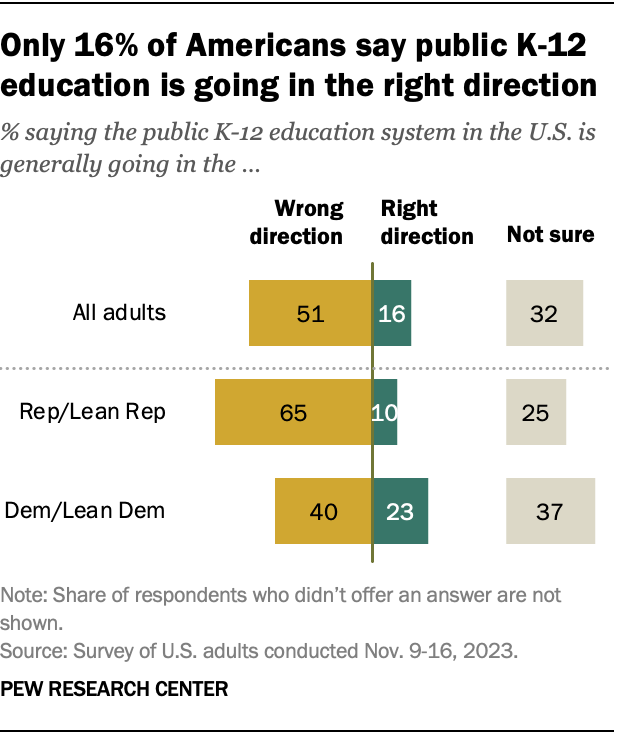

About half of U.S. adults (51%) say the country’s public K-12 education system is generally going in the wrong direction. A far smaller share (16%) say it’s going in the right direction, and about a third (32%) are not sure, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in November 2023.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand how Americans view the K-12 public education system. We surveyed 5,029 U.S. adults from Nov. 9 to Nov. 16, 2023.

The survey was conducted by Ipsos for Pew Research Center on the Ipsos KnowledgePanel Omnibus. The KnowledgePanel is a probability-based web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses. The survey is weighted by gender, age, race, ethnicity, education, income and other categories.

Here are the questions used for this analysis , along with responses, and the survey methodology .

A majority of those who say it’s headed in the wrong direction say a major reason is that schools are not spending enough time on core academic subjects.

These findings come amid debates about what is taught in schools , as well as concerns about school budget cuts and students falling behind academically.

Related: Race and LGBTQ Issues in K-12 Schools

Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say the public K-12 education system is going in the wrong direction. About two-thirds of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (65%) say this, compared with 40% of Democrats and Democratic leaners. In turn, 23% of Democrats and 10% of Republicans say it’s headed in the right direction.

Among Republicans, conservatives are the most likely to say public education is headed in the wrong direction: 75% say this, compared with 52% of moderate or liberal Republicans. There are no significant differences among Democrats by ideology.

Similar shares of K-12 parents and adults who don’t have a child in K-12 schools say the system is going in the wrong direction.

A separate Center survey of public K-12 teachers found that 82% think the overall state of public K-12 education has gotten worse in the past five years. And many teachers are pessimistic about the future.

Related: What’s It Like To Be A Teacher in America Today?

Why do Americans think public K-12 education is going in the wrong direction?

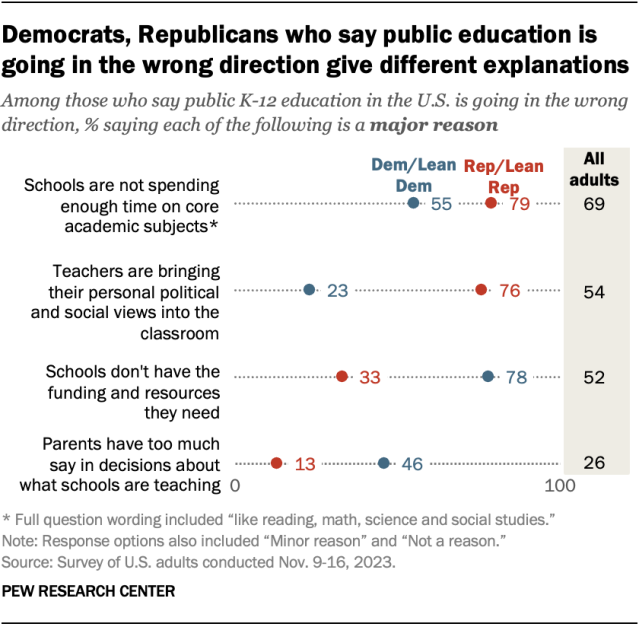

We asked adults who say the public education system is going in the wrong direction why that might be. About half or more say the following are major reasons:

- Schools not spending enough time on core academic subjects, like reading, math, science and social studies (69%)

- Teachers bringing their personal political and social views into the classroom (54%)

- Schools not having the funding and resources they need (52%)

About a quarter (26%) say a major reason is that parents have too much influence in decisions about what schools are teaching.

How views vary by party

Americans in each party point to different reasons why public education is headed in the wrong direction.

Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say major reasons are:

- A lack of focus on core academic subjects (79% vs. 55%)

- Teachers bringing their personal views into the classroom (76% vs. 23%)

In turn, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to point to:

- Insufficient school funding and resources (78% vs. 33%)

- Parents having too much say in what schools are teaching (46% vs. 13%)

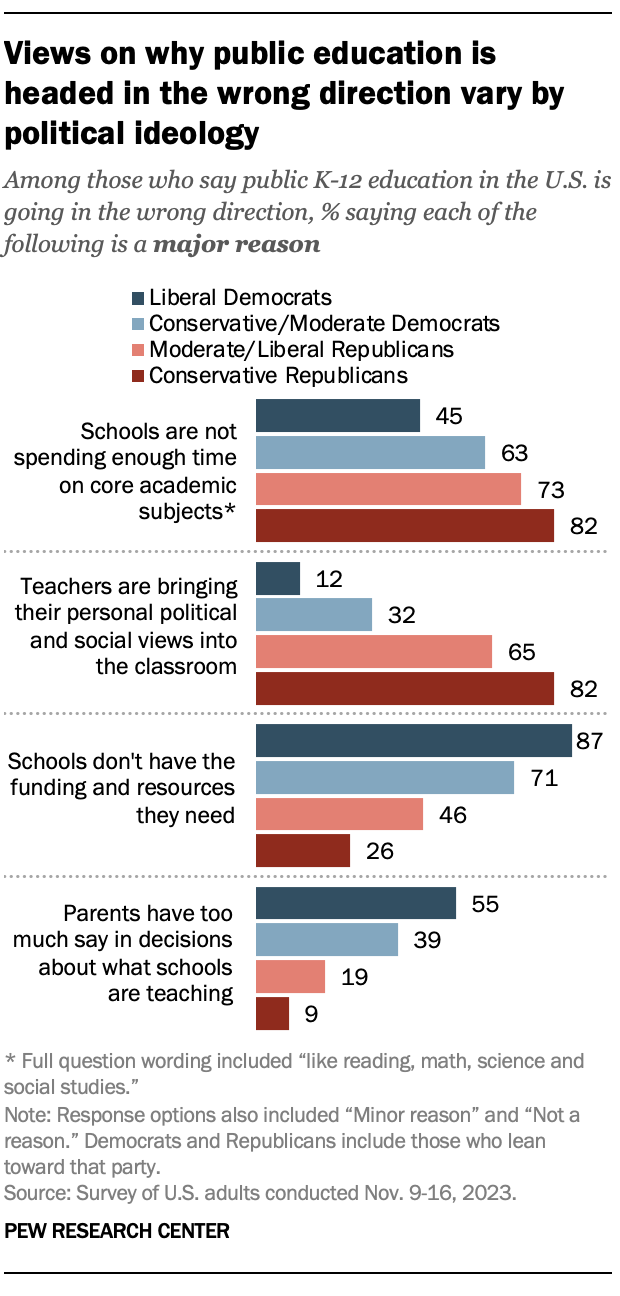

Views also vary within each party by ideology.

Among Republicans, conservatives are particularly likely to cite a lack of focus on core academic subjects and teachers bringing their personal views into the classroom.

Among Democrats, liberals are especially likely to cite schools lacking resources and parents having too much say in the curriculum.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis , along with responses, and the survey methodology .

- Partisanship & Issues

- Political Issues

Rachel Minkin is a research associate focusing on social and demographic trends research at Pew Research Center .

72% of U.S. high school teachers say cellphone distraction is a major problem in the classroom

U.s. public, private and charter schools in 5 charts, is college worth it, half of latinas say hispanic women’s situation has improved in the past decade and expect more gains, a quarter of u.s. teachers say ai tools do more harm than good in k-12 education, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Americans Have Given Up on Public Schools. That’s a Mistake.

The current debate over public education underestimates its value—and forgets its purpose.

Public schools have always occupied prime space in the excitable American imagination. For decades, if not centuries, politicians have made hay of their supposed failures and extortions. In 2004, Rod Paige, then George W. Bush’s secretary of education, called the country’s leading teachers union a “terrorist organization.” In his first education speech as president, in 2009, Barack Obama lamented the fact that “despite resources that are unmatched anywhere in the world, we’ve let our grades slip, our schools crumble, our teacher quality fall short, and other nations outpace us.”

Explore the October 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

President Donald Trump used the occasion of his inaugural address to bemoan the way “beautiful” students had been “deprived of all knowledge” by our nation’s cash-guzzling schools. Educators have since recoiled at the Trump administration’s budget proposal detailing more than $9 billion in education cuts, including to after-school programs that serve mostly poor children. These cuts came along with increased funding for school-privatization efforts such as vouchers. Our secretary of education, Betsy DeVos, has repeatedly signaled her support for school choice and privatization, as well as her scorn for public schools, describing them as a “dead end” and claiming that unionized teachers “care more about a system, one that was created in the 1800s, than they care about individual students.”

Few people care more about individual students than public-school teachers do, but what’s really missing in this dystopian narrative is a hearty helping of reality: 21st-century public schools, with their record numbers of graduates and expanded missions, are nothing close to the cesspools portrayed by political hyperbole. This hyperbole was not invented by Trump or DeVos, but their words and proposals have brought to a boil something that’s been simmering for a while—the denigration of our public schools, and a growing neglect of their role as an incubator of citizens.

Americans have in recent decades come to talk about education less as a public good, like a strong military or a noncorrupt judiciary, than as a private consumable. In an address to the Brookings Institution, DeVos described school choice as “a fundamental right.” That sounds appealing. Who wouldn’t want to deploy their tax dollars with greater specificity? Imagine purchasing a gym membership with funds normally allocated to the upkeep of a park.

My point here is not to debate the effect of school choice on individual outcomes: The evidence is mixed, and subject to cherry-picking on all sides. I am more concerned with how the current discussion has ignored public schools’ victories, while also detracting from their civic role. Our public-education system is about much more than personal achievement; it is about preparing people to work together to advance not just themselves but society. Unfortunately, the current debate’s focus on individual rights and choices has distracted many politicians and policy makers from a key stakeholder: our nation as a whole. As a result, a cynicism has taken root that suggests there is no hope for public education. This is demonstrably false. It’s also dangerous.

The idea that popular education might best be achieved privately is nothing new, of course. The Puritans, who saw education as necessary to Christian practice, experimented with the idea, and their experience is telling. In 1642, they passed a law—the first of its kind in North America—requiring that all children in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts receive an education. Puritan legislators assumed, naively, that parents would teach children in their homes; however, many of them proved unable or unwilling to rise to the task. Five years later, the legislators issued a corrective in the form of the Old Deluder Satan Law: “It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures,” the law intoned, “it is therefore ordered … that everie Township [of 100 households or more] in this Jurisdiction” be required to provide a trained teacher and a grammar school, at taxpayer expense.

Almost 400 years later, contempt for our public schools is commonplace. Americans, and especially Republicans, report that they have lost faith in the system, but notably, nearly three-quarters of parents rate their own child’s school highly; it’s other people’s schools they worry about. Meanwhile, Americans tend to exaggerate our system’s former glory. Even in the 1960s, when international science and math tests were first administered, the U.S. was never at the top of the rankings and was often near the bottom.

Not only is the idea that American test scores were once higher a fiction, but in some cases they have actually improved over time, especially among African American students. Since the early 1970s, when the Department of Education began collecting long-term data, average reading and math scores for 9- and 13-year-olds have risen significantly.

These gains have come even as the student body of American public schools has expanded to include students with ever greater challenges. For the first time in recent memory, a majority of U.S. public-school students come from low-income households. The student body includes a larger proportion than ever of students who are still learning to speak English. And it includes many students with disabilities who would have been shut out of public school before passage of the 1975 law now known as the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, which guaranteed all children a “free appropriate public education.”

The fantasy that in some bygone era U.S. test scores were higher has prevented us from acknowledging other possible explanations for America’s technological, scientific, and cultural preeminence. In her 2013 book, Reign of Error , Diane Ravitch—an education historian and former federal education official who originally supported but later became a critic of reforms like No Child Left Behind—cites surprising evidence that a nation’s higher position on an international ranking of test scores actually predicted lower per capita GDP decades later, compared with countries whose test scores ranked worse. Other findings complicate the picture, but at a minimum we can say that there is no clear connection between test scores and a nation’s economic success. Surely it’s reasonable to ask whether some of America’s success might derive not from factors measured by standardized tests, but from other attributes of our educational system. U.S. public schools, at their best, have encouraged a unique mixing of diverse people, and produced an exceptionally innovative and industrious citizenry.

Our lost faith in public education has led us to other false conclusions, including the conviction that teachers unions protect “bad apples.” Thanks to articles and documentaries such as Waiting for “Superman , ” most of us have an image seared into our brain of a slew of know-nothing teachers, removed from the classroom after years of sleeping through class, sitting in state-funded “rubber rooms” while continuing to draw hefty salaries. If it weren’t for those damned unions, or so the logic goes, we could drain the dregs and hire real teachers. I am a public-school-certified teacher whose own children attended public schools, and I’ve occasionally entertained these thoughts myself.

But unions are not the bogeyman we’re looking for. According to “The Myth of Unions’ Overprotection of Bad Teachers,” a well-designed study by Eunice S. Han, an economist at the University of Utah, school districts with strong unions actually do a better job of weeding out bad teachers and retaining good ones than do those with weak unions. This makes sense. If you have to pay more for something, you are more likely to care about its quality; when districts pay higher wages, they have more incentive to employ good teachers (and dispense with bad ones). And indeed, many of the states with the best schools have reached that position in the company of strong unions. We can’t say for sure that unions have a positive impact on student outcomes—the evidence is inconclusive. But findings like Han’s certainly undermine reformers’ claims.

In defending our public schools, I do not mean to say they can’t be improved. But if we are serious about advancing them, we need to stop scapegoating unions and take steps to increase and improve the teaching pool. Teacher shortages are leaving many states in dire straits: The national shortfall is projected to exceed 100,000 teachers by next year.

That many top college graduates hesitate to join a profession with low wages is no great surprise. For many years, talented women had few career alternatives to nursing and teaching; this kept teacher quality artificially high. Now that women have more options, if we want to attract strong teachers, we need to pay competitive salaries. As one observer put it, if you cannot find someone to sell you a Lexus for a few dollars, that doesn’t mean there is a car shortage.

Oddly, the idea of addressing our supply-and-demand problem the old-fashioned American way, with a market-based approach, has been largely unappealing to otherwise free-market thinkers. And yet raising salaries would have cascading benefits beyond easing the teacher shortage. Because salaries are associated with teacher quality, raising pay would likely improve student outcomes. Massachusetts and Connecticut have attracted capable people to the field with competitive pay, and neither has an overall teacher shortage.

Apart from raising teacher pay, we should expand the use of other strategies to attract talent, such as forgivable tuition loans, service fellowships, hardship pay for the most-challenging settings (an approach that works well in the military and the foreign service), and housing and child-care subsidies for teachers, many of whom can’t afford to live in the communities in which they teach. We can also get more serious about de-larding a bureaucracy that critics are right to denounce: American public schools are bloated at the top of the organizational pyramid, with too many administrators and not enough high-quality teachers in the classroom.

Where schools are struggling today, collectively speaking, is less in their transmission of mathematical principles or writing skills, and more in their inculcation of what it means to be an American. The Founding Fathers understood the educational prerequisites on which our democracy was based (having themselves designed it), and they had far grander plans than, say, beating the Soviets to the moon, or ensuring a literate workforce.

Thomas Jefferson, among other historical titans, understood that a functioning democracy required an educated citizenry, and crucially, he saw education as a public good to be included in the “articles of public care,” despite his preference for the private sector in most matters. John Adams, another proponent of public schooling, urged, “There should not be a district of one mile square, without a school in it, not founded by a charitable individual, but maintained at the expense of the people themselves.”

In the centuries since, the courts have regularly affirmed the special status of public schools as a cornerstone of the American democratic project. In its vigorous defenses of students’ civil liberties—to protest the Vietnam War, for example, or not to salute the flag—the Supreme Court has repeatedly held public schools to an especially high standard precisely because they play a unique role in fostering citizens.

This role isn’t limited to civics instruction; public schools also provide students with crucial exposure to people of different backgrounds and perspectives. Americans have a closer relationship with the public-school system than with any other shared institution. (Those on the right who disparagingly refer to public schools as “government schools” have obviously never been to a school-board meeting, one of the clearest examples anywhere of direct democracy in action.) Ravitch writes that “one of the greatest glories of the public school was its success in Americanizing immigrants.” At their best, public schools did even more than that, integrating both immigrants and American-born students from a range of backgrounds into one citizenry.

At a moment when our media preferences, political affiliations, and cultural tastes seem wider apart than ever, abandoning this amalgamating function is a bona fide threat to our future. And yet we seem to be headed in just that direction. The story of American public education has generally been one of continuing progress, as girls, children of color, and children with disabilities (among others) have redeemed their constitutional right to push through the schoolhouse gate. But in the past few decades, we have allowed schools to grow more segregated, racially and socioeconomically. (Charter schools, far from a solution to this problem, are even more racially segregated than traditional public schools.)

Simultaneously, we have neglected instruction on democracy. Until the 1960s, U.S. high schools commonly offered three classes to prepare students for their roles as citizens: Government, Civics (which concerned the rights and responsibilities of citizens), and Problems of Democracy (which included discussions of policy issues and current events). Today, schools are more likely to offer a single course. Civics education has fallen out of favor partly as a result of changing political sentiment. Some liberals have come to see instruction in American values—such as freedom of speech and religion, and the idea of a “melting pot”—as reactionary. Some conservatives, meanwhile, have complained of a progressive bias in civics education.

Especially since the passage of No Child Left Behind, the class time devoted to social studies has declined steeply. Most state assessments don’t cover civics material, and in too many cases, if it isn’t tested, it isn’t taught. At the elementary-school level, less than 40 percent of fourth-grade teachers say they regularly emphasize topics related to civics education.

So what happens when we neglect the public purpose of our publicly funded schools? The discussion of vouchers and charter schools, in its focus on individual rights, has failed to take into account American society at large. The costs of abandoning an institution designed to bind, not divide, our citizenry are high.

Already, some experts have noted a conspicuous link between the decline of civics education and young adults’ dismal voting rates. Civics knowledge is in an alarming state: Three-quarters of Americans can’t identify the three branches of government. Public-opinion polls, meanwhile, show a new tolerance for authoritarianism, and rising levels of antidemocratic and illiberal thinking. These views are found all over the ideological map, from President Trump, who recently urged the nation’s police officers to rough up criminal suspects, to, ironically, the protesters who tried to block DeVos from entering a Washington, D.C., public school in February.

We ignore public schools’ civic and integrative functions at our peril. To revive them will require good faith across the political spectrum. Those who are suspicious of public displays of national unity may need to rethink their aversion. When we neglect schools’ nation-binding role, it grows hard to explain why we need public schools at all. Liberals must also work to better understand the appeal of school choice, especially for families in poor areas where teacher quality and attrition are serious problems. Conservatives and libertarians, for their part, need to muster more generosity toward the institutions that have educated our workforce and fueled our success for centuries.

The political theorist Benjamin Barber warned in 2004 that “America as a commercial society of individual consumers may survive the destruction of public schooling. America as a democratic republic cannot.” In this era of growing fragmentation, we urgently need a renewed commitment to the idea that public education is a worthy investment, one that pays dividends not only to individual families but to our society as a whole.

How much does the government spend on education? What percentage of people are college educated? How are kids doing in reading and math?

Table of Contents

What is the current state of education in the us.

How much does the US spend per student?

Public school spending per student

Average teacher salary.

How educated are Americans?

People with a bachelor's degree

Educational attainment by race and ethnicity.

How are kids doing in reading and math?

Proficiency in math and reading

What is the role of the government in education?

Spending on the education system

Agencies and elected officials.

The education system in America is made up of different public and private programs that cover preschool, all the way up to colleges and universities. These programs cater to many students in both urban and rural areas. Get data on how students are faring by grade and subject, college graduation rates, and what federal, state, and local governments spending per student. The information comes from various government agencies including the National Center for Education Statistics and Census Bureau.

During the 2019-2020 school year, there was $15,810 spent on K-12 public education for every student in the US.

Education spending per k-12 public school students has nearly doubled since the 1970s..

This estimate of spending on education is produced by the National Center for Education Statistics. Instruction accounts for most of the spending, though about a third includes support services including administration, maintenance, and transportation. Spending per student varies across states and school districts. During the 2019-2020 school year, New York spends the most per student ($29,597) and Idaho spends the least ($9,690).

During the 2021-2022 school year , the average public school teacher salary in the US was $66,397 .

Instruction is the largest category of public school spending, according to data from the National Center for Educational Statistics. Adjusting for inflation, average teacher pay is down since 2010.

In 2021 , 35% of people 25 and over had at least a bachelor’s degree.

Over the last decade women have become more educated than men..

Educational attainment is defined as the highest level of formal education a person has completed. The concept can be applied to a person, a demographic group, or a geographic area. Data on educational attainment is produced by the Census Bureau in multiple surveys, which may produce different data. Data from the American Community Survey is shown here to allow for geographic comparisons.

In 2021 , 61% of the Asian 25+ population had completed at least four years of college.

Educational attainment data from the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey allows for demographic comparisons across the US.

In 2022, proficiency in math for eighth graders was 26.5% .

Proficiency in reading in 8th grade was 30.8% ., based on a nationwide assessment, reading and math scores declined during the pandemic..

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is the only nationally representative data that measures student achievement. NAEP is Congressionally mandated. Tests are given in a sample of schools based on student demographics in a given school district, state, or the US overall. Testing covers a variety of subjects, most frequently math, reading, science, and writing.

In fiscal year 2020, governments spent a combined total of $1.3 trillion on education.

That comes out to $4,010 per person..

USAFacts categorizes government budget data to allocate spending appropriately and to arrive at the estimate presented here. Most government spending on education occurs at the state and local levels rather than the federal.

Government revenue and expenditures are based on data from the Office of Management and Budget, the Census Bureau, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Each is published annually, although due to collection times, state and local government data are not as current as federal data. Thus, when combining federal, state, and local revenues and expenditures, the most recent year for a combined number may be delayed.

| Early childhood education | ||

| Aid for education | ||

| Researches and regulates schools |

| Early childhood education |

| K-12 education |

| Higher education |

| Aid for education |

| Researches and regulates schools |

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

Policy Dialogue: The Meaning and Purpose of Public Education

From the History of Education quarterly (Volume 64, Issue 1), published by Cambridge University Press , a thoughtful, in-depth conversation about public education between Carol Burris and Johann Neem.

Carol Burris : If you ask one hundred Americans, “What is the purpose of public education?” you’re probably going to get at least ten different answers. There’ll be some similarities, but some answers will be quite different. In the beginning, the purpose was to create a literate American citizenry to be able to participate in democracy. Our founders realized that if they were going to give citizens the ability to actually shape government through elections, they had to have some knowledge base on which to make decisions. Academic achievement has also always been a big part of the purpose of public education. There have been other purposes as well, such as job training, which is once again becoming very popular. And there has even been the custodial function of schools, which we saw very clearly during COVID-19. When schools closed, education did not stop, but lots of parents were quite upset because they were dependent on the public education system to take care of their kids while they worked.

How has public schooling changed over the years? At its beginning, formal education was reserved for the elite. In 1892, the Committee of Ten decreed that education was for college preparation, mostly for white, male Protestant citizens. When the influx of European immigrants began, schools started to take on different functions: training in language, training in Americanism—learning what it is to be an American—and job training, from which emerged systems of tracking and ability grouping. Around the 1950s, the comprehensive high school predominated and we tried to create schools that were all things for all people. Then, in the early 2000s, there was a serious move to make schools more rigorous, focusing on college for all. And now the pendulum is swinging back to job training. So, there’s never been one purpose. And I don’t think there ever will be.

Johann Neem : I think you’re right about a lot of that. I think the question, then, is: What is it, at a moment like this, that justifies the common school model, the public school model? And I think, going back, as you said, to the founding, the preparation of citizens was one of the primary arguments to justify the expansion of public schooling. And the other public one, which is worth talking about, is socialization, or as you put it, learning to be an American. And I think that was also one of schools’ public functions in a diverse society. How do you bring people together in common institutions so they see themselves as members of the same people? After all, it wasn’t just in the United States that the expansion of public schooling and the formation of nation-states went hand in hand. And so those are two fundamental public purposes. I think you’re right. The civic purposes are threatened by the focus on work preparation and things like that. But I think even the socialization function is something we’re fighting over today. A lot of people in the education world are a little bit uncomfortable with the idea that part of their job is to take a diverse society and forge a common nation. So, both public purposes are threatened from different places. And I think we need those public purposes, they’re really important. I agree with you.

One of the things I found interesting about the nineteenth century is that, from the very beginning, the public schools took off, not because everybody wanted to create educated citizens, or everybody wanted to create a common American nation, but because there was a kind of overlapping consensus among a diverse set of stakeholders. There was an overlapping consensus that everybody benefits from these schools in different ways. Parents may have one set of goals. Students may have another. Teachers and educators may have a set of goals. Policymakers may have a set of goals. But there was enough overlap to sustain new institutions and build a very large number of stakeholders. And I think that’s the secret to why public schools have been so successful. The overlapping consensus between all these different stakeholders is that schools really matter to helping us get what we want. We’re all invested in them.

Carol Burris : I agree. And that’s what’s being threatened. That’s what upsets me the most. And it’s by design. Take Neal McCluskey, the education freedom director of the libertarian Cato Institute—the argument he makes for school choice is that we need it because we are so diverse. He argues that we will have wars within our schools if we don’t allow people to choose schools that reflect their values and their values alone. And I find that incredibly frightening because what it creates is Balkanization. Look at all of the major conflicts that we see now in Israel and Palestine, Iraq, and in the past in Northern Ireland. They happen when one faction or religion declares, “Here is my group; this is my set of beliefs, and I want nothing to do with that group and their set of beliefs.”

I led a high school for years that I loved. It was a very special place because it was diverse. It was diverse in terms of race. It was also diverse in terms of religion and socioeconomic status, and it was well funded. And in that school, kids got to know each other well, and when we eliminated tracking in the school, so that every classroom was a microcosm of the school, amazing things started to happen socially and intellectually for the children. What worries me so much about the school choice movement is that sense of shared community, of getting to know “the other” well, is exactly what we’re losing when school becomes a preferred commodity. You’re shopping for a school that aligns with your beliefs and aligns with your preferences and culture. You lose it all.

Johann Neem : That’s exactly right. One of the arguments that advocates of privatization make is just that: we’re too diverse to be a nation so we should be able to choose schools based on parents’ values. And one of the things I truly believe is that in a democracy as diverse as ours, common institutions that have an integrative function are essential. People must see each other as fellow citizens and empathize with each other.

This is the great danger of school choice, but the same danger also comes from progressive channels within the public schools, where I think a lot of educators are uncomfortable talking about the “we” in Americans. So, you’ll find statements like, “This holiday belongs to these people,” or “This is a white thing,” or “This is a Latino thing,” and so on. I have two concerns about that. One is that it threatens our capacity to tolerate, respect, and celebrate our diversity while also seeing ourselves as one people with shared traditions and rituals—and even books. The other thing I worry about is that it weakens the argument you just made when it’s coming from within the schools. In a sense, this discourse within the public schools creates the same outcomes that the parents’ rights advocates and privatizers are seeking to create in the school choice movement. Instead, I really think that we need to revive language about the commonness of the common schools, not at the expense of respecting diversity, but with the goal of becoming comfortable again with the fact that the schools are also important in forging a common Americanness. We are a diverse society, but we also need to share some things to be a people.

Carol Burris : I 100 percent agree. And it’s interesting that you said that. My granddaughter is in New York City, where she attends New York City public schools. They presently have school choice at the high school level within the public school system. And it’s a nightmare to navigate. You can’t just go to your neighborhood school anymore. So, now you’re talking about children as young as thirteen traveling. Most are schools based on interest. A school that’s for kids who want to be airplane pilots. A school for kids who want to be ferry captains and scuba divers. And the schools have different themes, or philosophies, much as you described. One school in the city has very progressive values on the website, talking more about social-emotional learning than about academics, stating that they’re against profit. My granddaughter wants a typical comprehensive high school not too far away, and in the world of choice, that is hard to find. Then you have to contend with admission preferences and lotteries in order to get in.

At the end of the day, the real outcome of “school choice” is that the parents really don’t have all that much choice. There are lotteries. There are themes. There are admission preferences. There’s screening and testing. It’s not as though they say, “Okay, this is your choice. And this is the choice of three hundred families who didn’t get the school. We’re going to open up three hundred new seats.” They don’t do that. The market system, whether it is public, charter, portfolio, voucher, just pushes kids around. The idea of a neighborhood high school where all kids of all interests, of all political backgrounds, of all religious backgrounds are welcome—it’s starting to disappear.

Johann Neem : I think that’s right. I find it interesting how you framed it, because, even as you were talking, I was thinking about how fortunate I feel to live in a town small enough that you just send your children to your neighborhood school, and you don’t have the agony of choice. The choice regime in New York, as you’ve described it, forces parents to start thinking about schooling as a private good for their child. The choice process privatizes education internally, because if I had to choose the school my child attended, I’d be doing things to game the system. I’d be doing all sorts of things to figure out the best way to move my child ahead. And as a parent, that’s totally natural. In fact, one of the things we parents ought to do is be our children’s advocates. But with losing the sense of the common school comes a loss of balance. I worry that the moment we liberate ourselves from that common framework, we will see new forms of inequality, as well as the kind of segregation you’re talking about. Not just by race, but class, party, ideology, religion, and more. I find my neighborhood school wonderful in certain ways and imperfect in other ways. But as a parent I’m invested in that neighborhood school, and through my investment, I’m invested in the other people who live around me. And this is what makes it a public good.

Carol Burris : For sure. And it also has an effect on the schools themselves. I was a high school principal for many years, and what I concentrated on was the improvement of the school and taking care of the kids. But in the world of school choice, you also have to be a marketer, right? Because now, as anybody who’s ever run a school knows, the quality markers of the school—whether they be test scores, college acceptance rates, or suspension rates—all of those different quality markers are also a reflection of who is attending your school and how many high-needs kids you have. So now, as a principal, you’re also trying to come up with ways to kind of game the system. How am I going to be more attractive to more involved families? To families that are maybe a little bit more affluent and can donate money to my underfunded school? To the parents of higher-achieving children that will raise overall test scores? And to many parents, it feels like The Hunger Games . They’re trying their best to get their child into a good school, whether it be a charter school, or a private school, or a public school. What are the admissions criteria? What can I do to get my child to go to the school that I think is the best fit? And what that does to the system over time is that parents become less invested in local school improvement and more invested in school choice.

Our kids grew up on Long Island, and the particular school district we lived in was not the best by far. But it was okay. So I became invested in that school district and its improvement. I got involved in the PTA. I ran for the school board. I served as school board president, and along with other parents, we did everything we could to make the school better. Now, looking back, if somebody had come to me back then and said, “Hey, listen, here’s school choice. You don’t have to work so hard to improve your local school. You can send your child to this district or that district or this private school, and we’ll pay for it.” As a young mom and a busy mom, I might have taken the chance. But what are the long-term effects of choice systems? Now, we’ve created this system where people think of public schools as a large, leaky boat, and pundits are shouting, “Oh, the boat is sinking!” So we start throwing out these life rafts, be they online schools, charter schools, voucher schools, and the emphasis is no longer on trying to right the ship, but to escape it.

Johann Neem : Yes, yes! And you’ve hit on two key points that are really important to me. When I was writing Democracy’s Schools , I came across a quote from Horace Mann, who basically said, if you allow parents to start to opt out, particularly parents of means, then you’re going to end up with pauper schools. You’re going to end up with schools where the public option becomes a charity model. And if you look around at certain parts of the world, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere, you’ll find that families that are middle-class or above basically opt out of the public system. As a result, the public system cannot rival these private schools. And it seems weird to me that people want to import that model to the US, where we have such a robust public system.

The thing you said about stakeholders is really important, because I don’t think public schools took off in the nineteenth century because people heard Thomas Jefferson, or Horace Mann, or Catharine Beecher and said, “Ah! I want to do what they said!” I think they wanted to send their own kids to the public schools because they saw benefits accruing to their neighbors’ kids. And as more children went to the public schools, people became more supportive of paying taxes. People became stakeholders because they went through the schools alongside their neighbors, and their children and grandchildren followed them. So, they wanted to reinvest in those schools.

One of the things I’ve realized is we think commitment to public education is a given, but our commitment to public education in America is as fragile as our commitment to almost any other public good. And what the privatizers are slowly doing in places like Arizona is they’re offering people those life rafts you’ve described and are trying to create stakeholders in the alternative system. The moment enough people have vouchers, or access to schools outside the public system, the common schools will start to wither. We’ll all be in life rafts, and the ship will go down. Supporters of privatization know that as long as the majority of Americans are invested in the public school system, they can’t shake it. But if they attract enough potential stakeholders who are interested in an alternative system, a different kind of regime, those stakeholders will begin investing in the school choice system. And then they can start to finally take down the public schools, which had been too popular to challenge for generations.

Carol Burris : You’re absolutely right! That is the intent, and they’re not hiding it. And as all of these different groups, like Moms for Liberty, create all of these storms, dustups, and crises that really don’t exist, the intent is to undermine public schools. Arizona is a prime example, and it’s becoming more and more difficult to sustain the public school system there. A few years ago, I went down to Arizona. This was even before the real expansion of the voucher system, but they had a huge charter school sector, a lot of it run by for-profit schools. I met with a superintendent who was doing everything he could to keep the integrity of his public schools. He told me about a conversation that he had had with a local politician, a member of the legislature. He wouldn’t give me the name, but I have absolutely no reason to doubt the quote that he shared with me. He asked the legislator, “Do you even see a purpose for public schools?” And the legislator looked at him and said with a straight face, “Well, somebody has to take out the garbage.” Now, that is a chilling quote that I’ve never forgotten. I think about that quote. Was he saying that the public schools take out the garbage? In other words, that their purpose is to deal with kids that no one wants? Or did he see the role of the public schools as raising the children who will take out the garbage? Perhaps he meant both. It shows the incredible cynicism and the disdain of some school choice advocates, the absolute disdain for the public school system.

Johann Neem : When I think about privatizers, they’re not all one group. There are capitalists trying to make money by getting access to public funds. There are honest pluralists, even if I disagree with them, who in some ways are echoing the arguments of pluralists on the political left. They’re echoing advocates of multiculturalism, but they’re using radical pluralism to push school choice rather than trying to achieve diverse communities within the public system. And then there are those who don’t think well of public institutions, as your quote suggests. They think we only need public institutions to deal with the so-called remainders. And they believe anybody, any family worth their salt, should be able to buy all other goods on the market. The idea that education is such a fundamental public good that no matter who you are in terms of wealth or color, or religion, or anything, you belong in these institutions with other people—that idea doesn’t even compute. And if you don’t believe that public goods are things everyone should share, and they’re just for those who can’t afford to buy them on the market, that’s a really scary proposition. It really flies in the face of the postrevolutionary ideals with which we started our conversation—that public schools offer public goods and everybody should be participating and contributing and benefiting from them.

Carol Burris : Yeah. You kind of wonder what the endgame is, too. When I try to figure it out, I often look back to the writings of Milton Friedman, who, in many ways, started this movement along with the segregationists. He didn’t believe that the public should even be paying for public education. When you listen carefully to Betsy DeVos and the libertarians who have been pushing this school choice system, they’re also pushing what they call “backpack funding,” or “money follows the child.” The concept works like this: here’s a figurative backpack, and we’re going to put money in it to educate your child. Now, parent, you go and shop. Think about some of the people that are pushing this idea. They are not people who are fond of paying taxes—just the opposite. So, one of my greatest fears is that over time, we will begin to view the real endgame: when we move to a fully school-choice system, then politicians who are very tax adverse, as many on the right are, will vote to reduce the funding that is in that backpack until we have a K-12 system that will be similar to college. Some will be able to afford it; some won’t. And I worry for the poorest kids, for the kids that nobody wants, for the kids with behavior issues, the kids with special needs; they will be left in a broken public school system. And that public school system will look like a very large room with kids staring at computers and somebody standing by the door with their arms crossed, preventing them from getting out.

Johann Neem : Yeah—rather than this American institution where everybody goes. In fact, for many Americans, one of the few things we still share is the experience of going to public school. And for those who don’t have the resources or the support, it offers civic inclusion rather than charity. No, I’m with you. I do wonder: what do we do at this moment? Your work, which advocates public schools and criticizes false claims about the success of alternative models, is one of the answers to that question. And I’m so grateful for that. But I also worry that we’re in a moment when trust in almost all American institutions has been declining for decades. So, one thing to be careful about is saying this is all about public schools, when it’s also about corporations. It’s also about universities. It’s also about government. It’s also about any institution that has seen declining trust across the board. How do you build that trust?

One of my fears is that the public schools themselves are not the best at doing that these days, and one of the reasons, I think, is that they have become more partisan. I worry about the public schools being identified with a party—the Democratic Party—rather than being viewed as common institutions that Democrats and Republicans generally agree on, even when they disagree on many other things. Both parties used to rally people around local public institutions: “Let’s support our public schools. Let’s support our public school teachers. Let’s support the local team. Let’s support the local club. Let’s support these things.” Now there’s a wedge. And I don’t think it’s just caused by Republicans. I think we have seen a kind of leftward turn among education schools and public school teachers that in some ways provides evidence that the schools are becoming more tied to a party. That is very dangerous, because one of the things I think that sustained schools was that they were not partisan institutions—they were these institutions in which everyone had an investment. So, what do we do about that? That’s an honest question.

Carol Burris : It’s something that troubles me as well. I do think that some of it, though, is regional. For example, if you go into rural areas, Republican rural areas, there’s still strong support for public schools. And I tend to think that, if anything, the politics of the schools probably are more conservative than progressive. But I also agree. I cited that example before about a New York City public high school whose values align with those of the political left. And it may be the only high school in the city that has those values, but eventually, that school will show up in the New York Post . Then it’s going to show up on Fox News. And then suddenly, here’s what will wind up happening: it will be taken up by people like Corey DeAngelis, or Betsy DeVos, and then all public schools will be painted in that way. And it’s interesting, I remember sharing this particular school’s website with a friend who is quite committed to public schools, and her remark was, “We are so good at handing people the rocks to throw at us.”

Maybe it’s a reflection of my age, or reflection of my experience, but I do think that every public school should be a place that welcomes every child. That means that it welcomes all children, not only based on ability, race, and ethnicity, but also on values. And there should be a place, in the social studies classes of a public school, to debate, right? To debate capitalism versus socialism, progressivism versus conservatism. But when a school’s website only shows one sliver of that, that becomes problematic. I do think that it would be helpful for public schools to sometimes take a deep breath and reflect on the fact that their parents come from all different places, that their faculty may hold various political opinions, and work hard to make sure that everyone, no matter their belief system, can comfortably send their child to the school, and not feel as though anybody is trying to push them one way or the other. That’s what we want for learners: to be critical thinkers, to be exposed to different ideas, and then to come up with their own conclusions.

Johann Neem : Where do we go next? We’ve covered a lot of ground.

Carol Burris : Well, there’s one thing we haven’t really touched upon, and that is the voucher system in the United States. I find it fascinating that it is so incredibly irresponsible. There are other countries that do have public funding for private schools. I’m going make a contrast now with Ireland. I have relatives who live there, as well as friends, and the Irish system is a very unusual system. It emerged as religious schooling, and most Irish schools today are run by religious organizations. You could think of it almost like a massive voucher system where the government is giving money, but education is being delivered by religious institutions. But here’s one of the critical pieces that is so lacking in the new voucher systems that we’re seeing popping up everywhere in the US: in Ireland, the government’s Department of Education controls the curriculum. They determine what the curriculum is; they determine the standards. They determine the testing. There are laws that protect students’ rights to enroll in these schools. They’re not allowed to discriminate. Even if it’s a Catholic school, you can’t just discriminate based on race, on wealth, on learning ability, on religion, or LGBTQ status.

And in other countries, where they do have a voucher system and they’re giving money to private schools, the schools themselves are more public. The strings that are attached are designed to not exclude students. The schools themselves are inspected. They’re regulated. The teachers are certified. And as for the financing of homeschooling, I don’t know of any other country that is even beginning to entertain that. So, when the voucher proponents in the US implement these systems, and then point to other places in the world where there are vouchers, what they’re not saying is how regulated those systems are, and how many guardrails are in place.

In contrast, when you take a look at the systems that are being pushed in the US now, the ESA systems—the Education Savings Account and the Education Scholarship Account—they are systems without guardrails. They are systems with no real comparative testing and evaluation measures. Not that I’m a big fan of standardized testing, but if you are going to require it of public and charter schools, why not voucher schools? There are now systems where parents receive the money and the parents are buying trampolines or going to theme parks. Now micro-schools are popping up—schools in people’s homes—it is just this incredibly loose, unregulated system that has no comparison anyplace in the world. To me, it is absolutely frightening, because I think we are going to find a sizable proportion of children presumably being educated who are not actually being educated at all. And as money flows into some of these micro-schools and homeschools, it’s going to be more and more difficult to even ascertain whether these children are being properly cared for. Because I can tell you, as a former principal, one of the functions of a public educator is that of a mandated reporter. Child abuse exists, and when you start to create systems where parents can grab money and then keep their kids home, you’re inviting all kinds of possible problems, in some cases not only educational neglect, but also physical and psychological abuse and neglect.

Once the system starts loose, it becomes very difficult to tighten and regulate. Look at charter schools. There is a difference between the original intent of the charter school movement, and what the movement became. And as people fight for regulations for charter schools, they encounter stiff resistance. You cannot just put in these ESA Programs willy-nilly, and then go back later and try to put in guardrails, especially given the vested interests that we talked about before. You’re not going to be able to do it, and I think it’s incredibly frightening.

Johann Neem : Oh, I agree. This is the irony. There are some advocates of school choice and voucher programs who recognize what you are saying about the importance of putting in guardrails, but that is certainly not happening in parts of the country where the presumption is that you need government out of the way.

As a citizen in a democracy, I have a right to have a role in shaping a curriculum through local representation in my school board or through my state representative, and I want to know that the public part of public schooling is happening in all of these schools that receive funding from tax monies. I want to know, not just about the quality of learning, but also that students are learning certain subjects, that we’re graduating people who understand science, who understand history. I want to know that about all schools, and I wouldn’t want to know any less about schools funded by a voucher system. But knowing these things would require, in a sense, more centralization than exists in the system we’ve built, from the local neighborhood school on up. It’s an interesting question about whether that kind of system could produce a more centralized bureaucracy than we have now. But you’re right, we have an obligation as a public to ensure that all children in the United States are getting a good quality education, an education that prepares them to participate in our common life regardless of where they go to school. And that’s a real challenge given American diversity, and given the inequalities. It’s going to become an even bigger challenge in a system where you have rampant school choice.

Carol Burris : Yes. Take the original ESA program in Arizona. I looked at it a few years back—I was absolutely appalled. Parents did not have to provide any evidence of learning, no evidence at all. All they had to do to get the money for the next year was to spend the money that they had received the year before. Parents are issuing high school diplomas in these systems. Are they competent to do it? Some of them probably are, but others probably not.

Think about the libertarians who were advocating for school choice years ago. They were romanticizing what education looked like at the very beginning of our country, when there were charity church schools, when kids were educated at home or weren’t being educated at all. They saw that as the model. And it’s amazing to me that rather than moving our society forward, we’re trying to return to seventeenth-century structures when it comes to schooling.

You start to wonder sometimes, because so many of the people who are so in favor of this unregulated, willy-nilly school choice system are also people who didn’t respect the last election. Although you and I might say that we want a well-educated citizenry for a well-functioning democracy, these systems are being pushed by people who perhaps don’t want people to be well-educated at all. You remember Trump’s famous quote: “I love the undereducated.”

Johann Neem : But I think we have to remember that trust in a democracy has to be earned. This is where, to the extent that I am critical of the education establishment, I’m critical because I think, like you said, that educators too often give their opponents the rocks to throw. I think we, and that includes professors, have to earn the trust of citizens. I think Trump wasn’t so much saying to voters, “I love the poorly educated,” as “I know that you don’t trust the educated to take care of your values, to take care of your economic interests, to take care of your country.” And for public schools to make it, we who are advocates of public schools and think they’re fundamental institutions, need to show that we do deserve that trust.

We can show that public schools are effective. There are lots of studies to show they’re more effective than private schools when you correct for socioeconomic status. But we also have to show that they’re not going to be places that, as we talked about earlier, are overly partisan or unwelcoming to certain groups; we have to show that everybody belongs and that these are mainstream institutions. And I think political partisanship is intentional in some of the ways teachers are professionalized today in schools of education, where they are learning to see their schools, and themselves, as remaking America along progressive lines. So I think we must be aware that there is a tension there. Mainstream Americanism doesn’t mean racism. But it also may not mean always being “anti-racist.” It means embracing a world where there are complex issues and the school doesn’t have one position on everything, as you said earlier. Because I worry that the schools are generating distrust in a world that’s already distrustful and polarized. And the public schools are so important that anything that starts to tip the scales towards privatization frightens me.

Carol Burris : I don’t disagree with you. But how do you do that? I was once on a group call that was discussing the reopening of schools near the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. The group was making the argument that we shouldn’t reopen schools until an extensive list of other social issues were addressed, and as a former principal, I was thinking, “I’ve got to get off this call, because we need to reopen schools and get children back in.” So, how do you convince people who are committed to all of those causes to say, “Hey, public education is in trouble.” We’re going to lose it. We need to all keep our eye on the prize, which is keeping the American public invested in public schools. How do we do that?

Johann Neem : Well, first, we say what you just said. I mean it. I agree that it’s a real challenge. It’s a challenge when educators don’t see the distinction between partisan values and the political values of a democracy, including the broadly political purposes of public education, the preparation of citizens for critical thinking, the cultivation of a shared national identity, the promotion of equality, respect for diversity. And I think that what has happened on the left and the right is eerily similar, where if you don’t agree with my left-leaning partisan values, you must be opposed to social justice. Or you must be a racist. And the right has its own version with its reaction to libraries, where if you don’t agree with my list of books to ban, you must not care about religion or family values. It’s not just a one-sided problem.

We need to find a way to promote the broad political purposes of public education. That is what holds us together. And there’s no reason why you can’t have a conservative history teacher or a liberal history teacher. Those are not the criteria. There is a lot of shared ground among Americans of all backgrounds. When you poll Americans on questions of history and politics, they are not really that far apart.

We need a sense of moderation and balance. I do find that when you look at education school curricula, or the admissions criteria, student teachers almost have to agree with a set of partisan ideas to be considered a good teacher. We need to pull back on that and say that the work of public schools is broadly political, so we have to be careful about the difference between broadly political ideas and partisanship on both sides. To have a common school, we don’t want education coming from the right any more than from the left. And it is hard, because we’ve created a dynamic where sometimes we don’t see the right’s responses as reflecting anything that’s real. I think we have to be honest that sometimes they are. Even if their responses may not seem appropriate in the light of our own values, it’s not because they have no facts on their side—they do observe things that make them lose trust. They’re not reacting to nothing—the reactions are coming from something. And if our goal is the protection of public schools, we have to start by acknowledging that not all criticism is in bad faith, that people are often responding to deeply felt concerns. There are a lot of bad-faith actors out there. So why not respond to those who are responding to something with some good faith?

Carol Burris : Yes, I think you’re right, and I think it’s an incredibly sensible response. Unfortunately, sensible solutions don’t seem to be winning the day. What I would say to people who believe that the school should be the place to teach very progressive ideals is if in doing that, you wind up losing many families who are politically conservative, you’re never going to achieve your goal. You want them in the tent. You want their children to hear this. It’s part of the reason you see these Christian nationalist academies popping up—and they are, along with charter schools. It’s like the old song, “How Ya Gonna Keep’em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree?)” You have groups of parents that don’t want their kids to see “Paree.” They only want them exposed to one set of values—their values. Young people, they’re so open. They are just naturally liberal. They are naturally progressive. And if all of the kids in your community who come from conservative homes are now in religious schools or in homeschools or in right-wing charter schools, they’re never going to be exposed to more progressive ideals that you might have in your public school.

You need to keep that tent open so that kids have an opportunity to become tolerant of others and their point of view.. Our middle daughter attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She was appalled by the anti-Semitic attitudes that she encountered there from kids whom she considered to be friends. And when she would talk to them about it, what she found was that they were never exposed to Jewish families. So they believed all of these stereotypes that they had heard. If we make our public schools places that conservative parents and parents on the right feel they need to avoid, their children will never be exposed to different cultures, to different religions and races, and they’ll not have that opportunity to grow as accepting and tolerant Americans.

Johann Neem : I think that’s right. So, it brings us full circle. The only thing I would add is that it goes both ways. As a professor, and someone who works in education circles, I’ve often been around progressives who have stereotypical images of conservatives in general, and they don’t interact with conservatives often. And their stereotypes of what people are like don’t always hold true. So I have two worries. One is that the public school system will come to an end if conservative families feel they need to withdraw, because their departure would represent a significant loss of stakeholders. The other worry is that if the schools truly do become bastions of progressivism, it’s not just the conservatives who won’t be exposed to progressive ideas—we’ll all become more Balkanized, as you put it earlier. Both progressives and conservatives will end up in echo chambers of their own. And that is not preparation for living in a diverse democracy, where it is important to respect people who come from all walks of life. We’d lose the capacity to teach that respect, which I think is a shared value between progressives and conservatives alike. So it affects everyone.

Carol Burris : It does cut both ways. I don’t disagree at all.

Johann Neem : I didn’t think you would.

Carol Burris : You know, we’re at this Humpty Dumpty moment for public schools, and if we don’t recognize it, and keep Humpty up on the wall, we’re not going to be able to put the pieces back together again—just like the system in Chile and some other places that have followed this model and seen dramatic declines in public school enrollments, stagnant test scores in literacy and mathematics, and widening achievement gaps between children from higher- and lower-income families. And we’re getting very, very close to that tipping point. So, I think a lot of honest conversations have to be had.

Johann Neem : That’s also a great name for a book: Keep Humpty on the Wall.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

Report | Budget, Taxes, and Public Investment

Public education funding in the U.S. needs an overhaul : How a larger federal role would boost equity and shield children from disinvestment during downturns

Report • By Sylvia Allegretto , Emma García , and Elaine Weiss • July 12, 2022

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

Summary

Education funding in the United States relies primarily on state and local resources, with just a tiny share of total revenues allotted by the federal government. Most analyses of the primary school finance metrics—equity, adequacy, effort, and sufficiency—raise serious questions about whether the existing system is living up to the ideal of providing a sound education equitably to all children at all times. Districts in high-poverty areas, which serve larger shares of students of color, get less funding per student than districts in low-poverty areas, which predominantly serve white students, highlighting the system’s inequity. School districts in general—but especially those in high-poverty areas—are not spending enough to achieve national average test scores, which is an established benchmark for assessing adequacy. Efforts states make to invest in education vary significantly. And the system is ill-prepared to adapt to unexpected emergencies.

These challenges are magnified during and after recessions. Following the Great Recession that began in December 2007, per-student education revenues plummeted and did not return to pre-recession levels for about eight years. The recovery in per-student revenues was even slower in high-poverty districts. This report combines new data on funding for states and for districts by school district poverty level, and over time, with evidence documenting the positive impacts of increasing investment in education to make a case for overhauling the school finance system. It calls for reforms that would ensure a larger role for the federal government to establish a robust, stable, and consistent school funding plan that channels sufficient additional resources to less affluent students in good times and bad. Furthermore, spending on public education should be retooled as an economic stabilizer, with increases automatically kicking in during recessions. Such a program would greatly mitigate cuts to public education as budgets are depleted, and also spur aggregate demand to give the economy a needed boost.

Following are key findings from the report:

Our current system for funding public schools shortchanges students, particularly low-income students. Education funding generally is inadequate and inequitable; It relies too heavily on state and local resources (particularly property tax revenues); the federal government plays a small and an insufficient role; funding levels vary widely across states; and high-poverty districts get less funding per student than low-poverty districts.

Those problems are magnified during and after recessions. Funding inadequacies and inequities tend to be aggravated when there is an economic downturn, which typically translates into problems that persist well after recovery is underway. After the 2007 onset of the Great Recession, for example, funding fell, and it took until 2015–2016, on average, to return to their pre-recession per-student revenue and spending levels. For high-poverty school districts, it took even longer—until 2016–2017—to rebound to their pre-recession revenue levels. And even after catching up with pre-recession levels, revenue levels in high-poverty districts lag behind the per-student funding in low-poverty districts. The general, long-standing funding inadequacies and inequities combined with the worsening of these problems during and in the aftermath of recessions have both short- and long-term repercussions that are costly for the students as well as for the country.

Increased federal spending on education after recessions helps mitigate funding shortfalls and inequities. Without increased federal education spending after recessions, school districts would suffer from an even greater decline in funding and even wider gaps between funding flowing to low-poverty and high-poverty districts.

Increased spending on education could help boost economic recovery. While Congress has enacted one-time education spending increases in difficult economic times, spending on public education should be considered one of the automatic stabilizers in our economic policy toolkit, designed to automatically increase and thus spur aggregate demand when private spending falls. Deployed this way, education spending becomes part of a set of large, broadly distributed programs that are countercyclical, i.e., designed to kick in when the economy overall is contracting and thus stave off or lessen the severity of a downturn. Along with other automatic stabilizers such as unemployment insurance, education spending thus would provide a stimulus to boost economic recovery.

We need an overhaul of the school finance system, with reforms ensuring a larger role for the federal government. In light of the concerns outlined in this report, policymakers must think differently both about school funding overall and about school funding during recessions. Public education is a public good, and as noted in this report, one that helps to stabilize the entire economy at critical points. Therefore, public spending on education should be treated as the public investment it is. While we leave it to policymakers to design specific reforms, we recommend an increased role for the federal government grounded in substantial, well targeted, consistent investment in the children who are our future, the professionals who help these children attain that future, and the environments in which they work. To establish a robust, stable, and consistent school funding plan that supports all children, investments need to be proportional to the size of the problems and to the societal and economic importance of the sector.

Introduction

The hope for the public education system in the United States is to provide a sound education equitably to all children regardless of where they live or into which families they are born. However, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed four interrelated, long-standing realities of U.S. public education funding that have long made that excellent, equitable education system impossible to achieve. First, inadequate levels of funding leave too many students unable to reach established performance benchmarks. Second, school funding is inequitable, with low-income students often and communities of color consistently lacking resources they need to meet their needs. Third, the level of funding reflects an overall underinvestment in education—that is, the U.S. is not spending as much as it could afford to spend in normal times. Fourth, given that educational investments are not sufficient across many districts even during normal times, schools are unable to make preparations to cope with emergencies or other unexpected circumstances. An added, less known feature is that economic downturns make all four of these problems worse. Downturns exacerbate funding inadequacies, inequities, underinvestment, and unpreparedness, causing cumulative harm to students, communities, and the public education system, and clawing back any prior progress. The severity of these problems varies widely across states and districts, as do the strength of states’ and localities’ economic and social protection systems, which may either compensate for or compound the problems.

The pandemic-led recession made these four major financial barriers to an excellent, equitable education system more visible, leading to serious questions about the U.S. education-funding model, which relies heavily on local and state revenues and draws only a small share of funding from the federal government. While public education is one of our greatest ideals and achievements—a free, quality education for every child regardless of means and background—the U.S. educational system is in need of significant improvements.

As the report will show, the core barriers to delivering universally excellent U.S. public education for all children—funding inadequacies and inequities that are exacerbated during tough economic times—were present in the system from the very start. They are the outcomes of a funding system that is shaped by many layers of policies and legal decisions at the local, state, and federal levels, creating widespread disparities in school finance realities across the thousands of districts across the country in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This complex funding puzzle speaks to the need for a funding overhaul to attain meaningful and widely shared improvements.

In this report, we first provide an overview of the characteristics of the U.S. education funding system. We present data analyses on school finance indicators, such as equity, adequacy, and effort, that expose the shortcomings of funding policies and decisions across the country. We also discuss factors behind some of these shortcomings, such as the heavy reliance on local and state sources of funding.

Second, we illustrate that recessions exacerbate the funding challenges schools face. We parse a multitude of data to present trends in school finance indicators both during and after the Great Recession, demonstrating that the immediate effects of federally targeted funds helped schools navigate recession-induced budget cuts. We also look at the shortfalls and inequitable nature of those investments. We explore how increased federal investments—in good economic times and bad—could help address these long-standing problems. We argue that public education funding is not only an investment in our societal present and future, but also is a ready-made mechanism for countering economic downturns. Economic theory and evidence both demonstrate that large, broadly distributed programs providing public support serve as cushions during economic downturns: they spur overall spending and thus aggregate demand when private spending falls. As we note, there are strong arguments for placing public education spending within the broader category of effective fiscal responses to recessions that are countercyclical—designed to increase spending when spending in the economy overall is contracting and thus stave off or lessen the severity of a downturn. Increases in public education spending during downturns work as automatic stabilizers for schools and provide stimulus to boost economic recovery. We review existing research on the consequences of funding in general and of funding changes—evidence that supports a larger role for the federal government.

Third, we discuss the benefits of rethinking public education funding, along with the societal and economic advantages of a robust, stable, and consistent U.S. school funding plan, both generally and as a countercyclical policy. We show that federal investment that sustains school funding throughout recessions and recoveries would provide three major advantages: It would help boost educational instruction and standards, it would provide continued high-quality instruction for students and employment to the public education workforce, and it would stimulate economic recovery. Education funding, in particular, would blanket the country while also targeting areas with the most need, making the recovery more equitable.

We conclude the report with final thoughts and next steps.

This paper uses several terms to refer to investments in education and to define the U.S. school finance system. Below, we explain how these terms are used in the report:

Revenue indicates the dollar amounts that have been raised through various sources (at the local, state, and federal levels) to support elementary and secondary education. We distinguish between federal, state, and local revenue. Local revenue, in some of our charts, is further divided into local revenue from property taxes and from other sources.

Spending or expenditures indicates the dollar amount devoted to elementary and secondary education. Expenditures are typically divided by function and object (instruction, support services , and noninstructional education activities). We rely on data on current expenditures (instead of total expenditures; see footnotes 2 and 30).