Directness in Speech and Writing

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In speech and writing , directness is the quality of being straightforward and concise : stating a main point early and clearly without embellishments or digressions . Directness contrasts with circumlocution , verbosity , and indirectness .

There are different degrees of directness, which are determined in part by social and cultural conventions. In order to communicate effectively with a particular audience , a speaker or writer needs to maintain a balance between directness and politeness .

Examples and Observations

- "The whole world will tell you, if you care to ask, that your words should be simple & direct . Everybody likes the other fellow's prose plain . It has even been said that we should write as we speak. That is absurd. ... Most speaking is not plain or direct, but vague, clumsy, confused, and wordy. ... What is meant by the advice to write as we speak is to write as we might speak if we spoke extremely well. This means that good writing should not sound stuffy, pompous, highfalutin, totally unlike ourselves, but rather, well—'simple & direct.' "Now, the simple words in the language tend to be the short ones that we assume all speakers know; and if familiar, they are likely to be direct. I say 'tend to be' and 'likely' because there are exceptions. ... "Prefer the short word to the long; the concrete to the abstract; and the familiar to the unfamiliar. But: "Modify these guidelines in the light of the occasion, the full situation, which includes the likely audience for your words." (Jacques Barzun, Simple & Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers , 4th ed. Harper Perennial, 2001)

- Revising for Directness "Academic audiences value directness and intensity. They do not want to struggle through overly wordy phrases and jumbled sentences. ... Examine your draft . Focus specifically on the following issues: 1. Delete the obvious: Consider statements or passages that argue for or detail what you and your peers already assume. ... 2. Intensify the least obvious: Think about your essay as a declaration of new ideas. What is the most uncommon or fresh idea? Even if it's a description of the problem or a slightly different take on solving it, develop it further. Draw more attention to it." (John Mauk and John Metz, The Composition of Everyday Life: A Guide to Writing , 5th ed. Cengage, 2015)

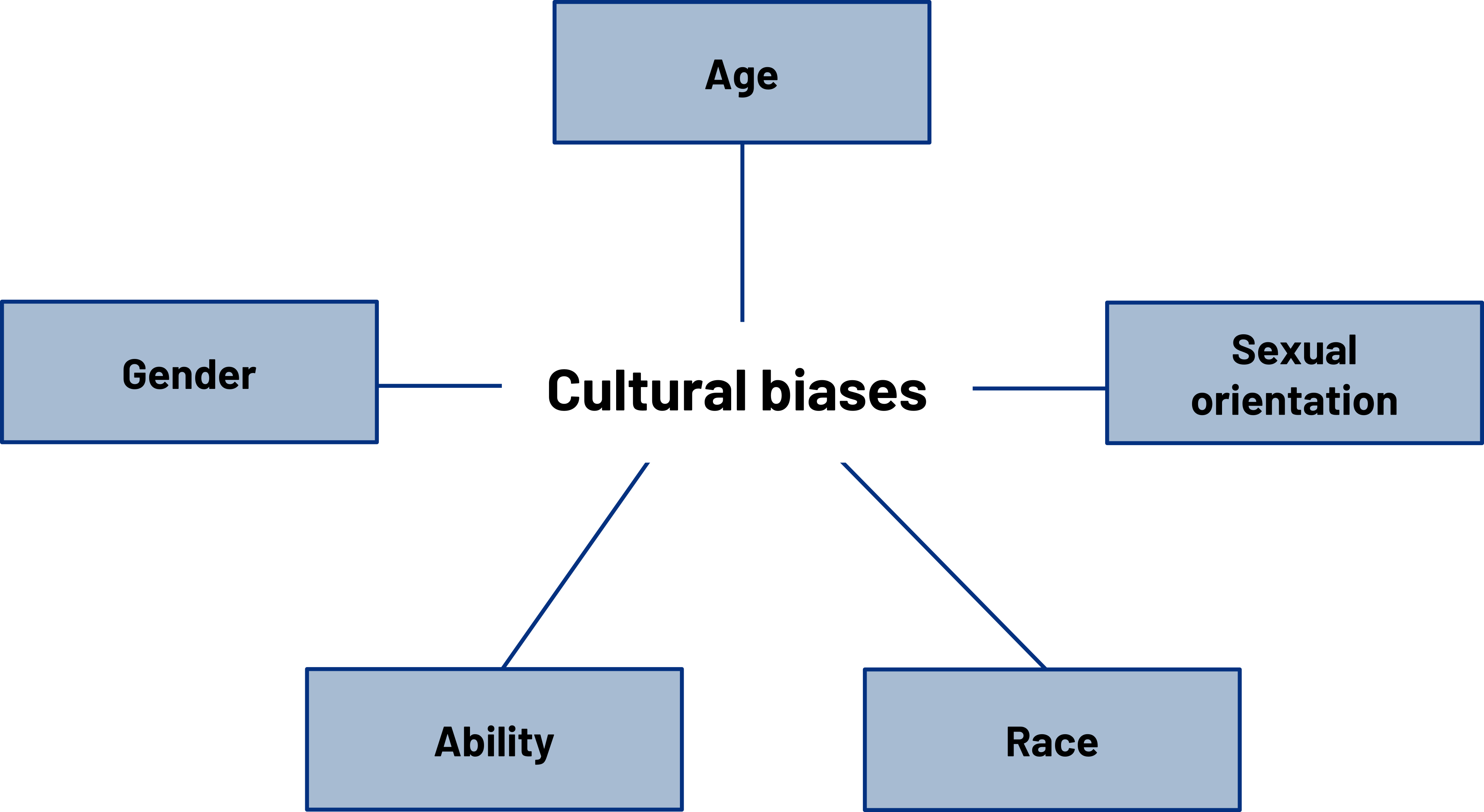

- Degrees of Directness "Statements may be strong and direct or they may be softer and less direct. For example, consider the range of sentences that might be used to direct a person to take out the garbage: Take out the garbage! Can you take out the garbage? Would you mind taking out the garbage? Let's take out the garbage. The garbage sure is piling up. Garbage day is tomorrow. "Each of these sentences may be used to accomplish the goal of getting the person to take out the garbage. However, the sentences show varying degrees of directness, ranging from the direct command at the top of the list to the indirect statement regarding the reason the activity needs to be undertaken at the bottom of the list. The sentences also differ in terms of relative politeness and situational appropriateness. ... "In matters of directness vs. indirectness, gender differences may play a more important role than factors such as ethnicity, social class, or region, although all these factors tend to intersect, often in quite complex ways, in the determination of the 'appropriate' degree of directness or indirectness for any given speech act ." (Walt Wolfram and Natalie Schilling-Estes, American English: Dialects and Variation . Wiley-Blackwell, 2006)

- Directness and Gender "While some of us will think that without the skills of 'good' writing a student cannot truly be empowered, we must be equally aware that the qualities of 'good' writing as they are advocated in textbooks and rhetoric books — directness , assertiveness and persuasiveness , precision and vigor—collide with what social conventions dictate proper femininity to be. Even should a woman succeed at being a 'good' writer she will have to contend with either being considered too masculine because she does not speak 'like a Lady,' or, paradoxically, too feminine and hysterical because she is, after all, a woman. The belief that the qualities that make good writing are somehow 'neutral' conceals the fact their meaning and evaluation changes depending on whether the writer is a man or woman." (Elisabeth Daumer and Sandra Runzo, "Transforming the Composition Classroom." Teaching Writing: Pedagogy, Gender, and Equity , ed. by Cynthia L. Caywood and Gillian R. Overing. State University of New York Press, 1987)

- Directness and Cultural Differences "The U.S. style of directness and forcefulness would be perceived as rude or unfair in, say, Japan, China, Malaysia, or Korea. A hard-sell letter to an Asian reader would be a sign of arrogance, and arrogance suggests inequality for the reader." (Philip C. Kolin, Successful Writing at Work . Cengage, 2009)

Pronunciation: de-REK-ness

- The Top 20 Figures of Speech

- Emma Watson's 2014 Speech on Gender Equality

- Figure of Speech: Definition and Examples

- What Is Attribution in Writing?

- What Is Clarity in Composition?

- Pause (Speech and Writing)

- Technical Writing

- Illocutionary Act

- Verbosity (Composition and Communication)

- Dialogue Definition, Examples and Observations

- How to Teach Reported Speech

- Basic Writing

- Definition of Audience

- Biased Language Definition and Examples

- What is Metadiscourse?

Learn Assertive Communication in 5 Simple Steps

Mia Belle Frothingham

Author, Researcher, Science Communicator

BA with minors in Psychology and Biology, MRes University of Edinburgh

Mia Belle Frothingham is a Harvard University graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Sciences with minors in biology and psychology

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Assertive communication is a style of communication where individuals clearly express their thoughts, feelings, and needs respectfully, confidently, and directly.

It emphasizes mutual understanding, respects others’ rights while defending personal boundaries, and promotes open, honest, and constructive dialogue.

Learning to speak assertively enables one to respect everyone’s needs and rights, including one’s own, and to maintain boundaries in relationships while helping others feel respected at the same time.

For instance, instead of saying “I can’t stand it when you’re late,” which might sound accusatory, an assertive communicator might say, “When you arrive late, it disrupts my schedule. Could we work on improving punctuality?”

This approach acknowledges feelings, addresses the issue directly, and suggests a resolution, all while respecting both parties’ perspectives.

5 Steps of Assertive Communication

Communicate your needs or wants directly, avoiding ambiguity, while still respecting the other person’s rights.

- Identify and Understand the Problem : This first step involves recognizing the issue. It could be a behavior, a situation, or an event that’s causing distress or conflict. Critical thinking skills are applied to analyze the problem accurately. Understanding the problem helps avoid assumptions, misconceptions, or biases and gives a solid foundation for assertive communication.

- Describe the Problem Objectively and Accurately : The next step is to clearly articulate the issue. Use specific, concrete language to describe who is involved, what is happening, when and where it’s happening. Tell the person what you think about their behavior without accusing them. It’s crucial not to over-dramatize or pass judgment but to provide a candid description of how the other person’s actions have affected the situation or you. Rather than saying, “You ruined my whole night,” specify the consequences, e.g., “Due to the delay, we now have less time to discuss our important matter.” The key here is to stick to observable facts and avoid judging or blaming language. For instance, instead of saying, “You’re always late,” you might say, “I noticed you’ve arrived late to the past three meetings.” Rather than using emotionally charged language, or applying labels and value judgments to the individual you are addressing, refer to concrete and factual aspects of the behavior that have upset you. For instance, if your friend was late for an important discussion, avoid making derogatory comments. Instead, provide a clear account of the situation, e.g., “We were supposed to meet at 17:30, but it’s now 17:50.” The formula “When you [other’s behavior], then [result of conduct], and I feel [your feelings]” gives a more detailed picture of the situation. For example, “When you override my rules with the children, my parental authority is undermined, and I feel disrespected.” This approach helps articulate your feelings while maintaining a respectful tone.

- Express Your Concerns and How You Feel : Tell them how you feel when they behave a certain way. Tell them how their behavior affects you and your relationship with them. To prevent the other person from feeling attacked, express how their actions have affected you using “I” statements. These help you take ownership of your feelings and communicate them without escalating conflict. Instead of saying, “You must stop!” say, “I would feel better if you didn’t do that.” For instance, “When you arrive late, I feel disrespected and worried because it interrupts our schedule.”

- Ask the Other Person for His/Her Perspective (Then Ask for a Reasonable Change) : Invite the other person to share their perspective. This shows respect for their feelings and thoughts, and can help you understand their point of view. It could require asking more questions, listening more carefully, or getting creative and exploring more prospects. Whatever it is, it is worth one’s time because, in the end, both parties leave feeling good, and no one ends up hurt. The secret to effective communication and forming better relationships is being mindful of what the other individual is trying to say. This requires trying not to bring up issues from the past or let one’s mind get distracted. These actions show disrespect and can cause one to lose focus. Thus, one cannot give a reasonable answer or be assertive. Mindfulness means being present and not thinking about anyone else who is not currently around oneself. Afterward, suggest a reasonable change that could resolve the issue. Make sure this is a specific, realistic action they can take, like, “Could we agree to start our meetings on time?”

- List the Positive Outcomes That Will Occur if the Person Makes the Agreed Upon Change : Explain the benefits of making the change. This encourages cooperation by showing how the change is mutually beneficial. The example above might be, “If we start our meetings on time, we’ll be able to adhere to our schedule and finish our work efficiently, reducing stress for everyone.”

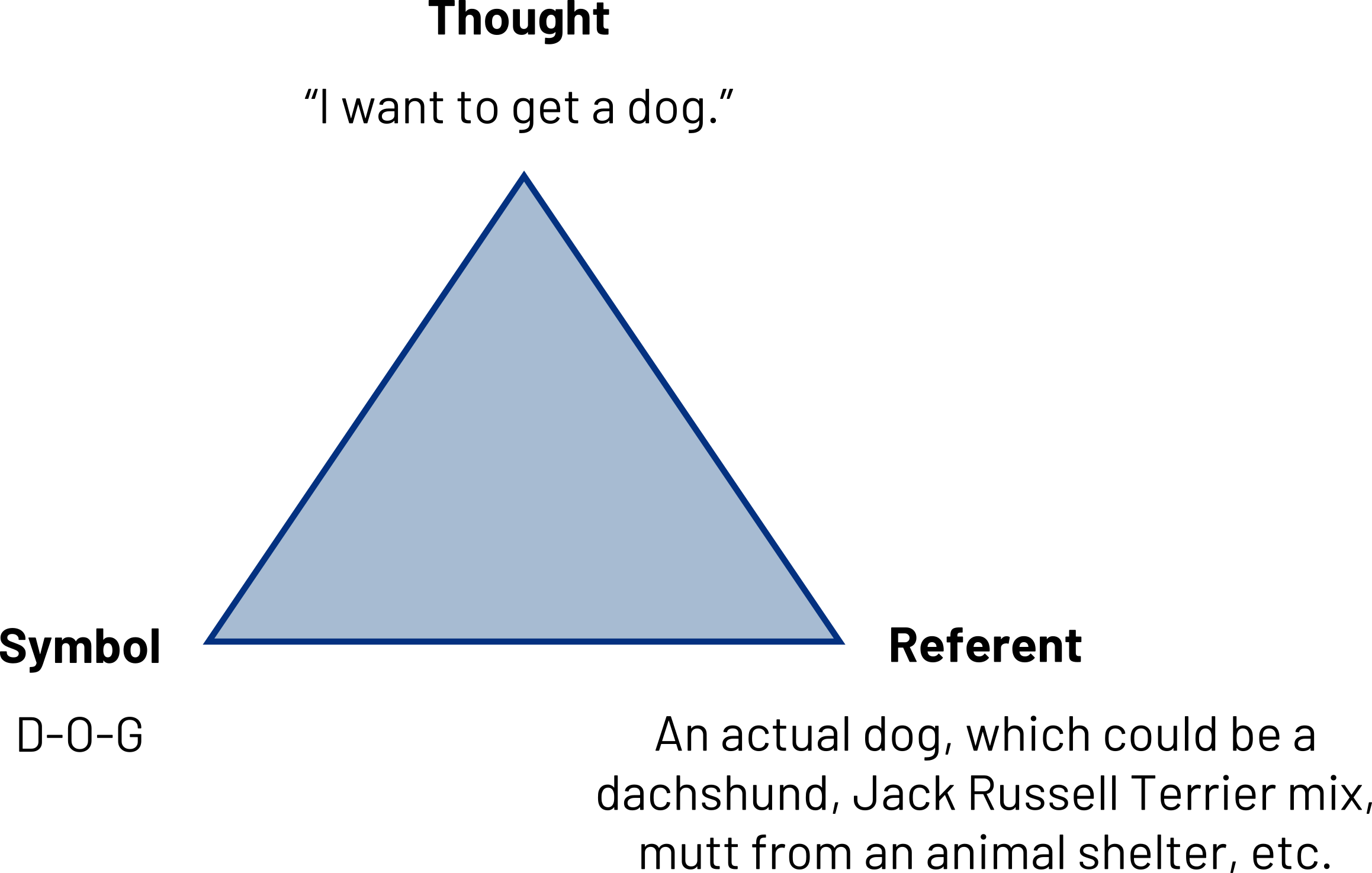

The XYZ* Formula for Assertive Communication

The XYZ formula is a technique for assertive communication that’s designed to help express your thoughts, feelings, or needs more clearly and effectively without causing unnecessary conflict.

The aim of the XYZ formula is to articulate your emotional responses (your internal reality) to the actions of others (the external reality) within certain contexts. You are the sole proprietor of your emotions; others cannot perceive your inner state unless you communicate it to them.

In the same way, you can only interact with and understand the external behaviors of others, not their internal experiences.

This model can be especially useful in tricky conversations, where emotions might be high and it’s important to communicate clearly and respectfully.

It’s also designed to reduce defensiveness in the person you’re speaking to, which can help the conversation be more productive.

| * | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| I feel upset | when you arrive late | for our dinner plans | and I would like you to inform me in advance if you’re running late |

| I feel frustrated | when you interrupt me | during our team meetings | and I would like you to wait until I finish presenting before adding your input |

| I feel ignored | when You check your phone | when we discuss household chores | and I would like you to give our discussions your full attention |

| I feel appreciated | when you cleaned the kitchen and prepared dinner | when I came home late from work | and I would like you to continue helping out when my workload gets heavy |

The benefit of the XYZ model is that it’s clear, non-threatening, and focuses on specific behaviors and the impact of those behaviors, rather than making generalizations about the person’s character.

This can make it more likely that the other person will be receptive to what you’re saying and be willing to work on a solution.

The 3 C’s of Assertive Communication

Keep your communication brief and to the point. People are more likely to understand and respond to concise messages.

Ensure that the message one wants to portray to another is straightforward to understand. We can take a crazy example like a dance routine – while it may be entertaining, it is not necessarily the most effective way to communicate one’s message.

When one wants to be heard, the messages one sends must be understandable and straightforward.

Most people will try to impress others with big, complicated words or terminology, but we should ask ourselves: does one want to impress the other, or should one be heard and understood?

One has to believe in one’s ability to handle a situation. It can be incredibly frustrating when someone says one thing and then says something different the next day.

Ask yourself: if you’re not convinced what your message is, how can you expect to communicate it effectively?

Over time, inconsistency in the messages one is sending can start to cause distrust in the people one is engaging with.

So in order for one to be taken seriously and earn credibility as a leader and a strong communicator, one has to be consistent in the messages one sends to others.

Before speaking, learn to take a moment and figure out precisely where one stands on the issue.

This will make it easier for other people to understand where they stand concerning their relationship with you.

Assertive communication involves controlling your emotions, tone of voice, and body language. Try to remain calm and composed, even when discussing difficult topics.

Speak in a calm and steady voice, and use non-threatening body language.

Keeping your emotions under control will help keep the conversation productive and prevent it from escalating into an argument.

Examples of Assertive Statements

Scenario : Your teenage daughter is known to get mad every time you attempt to tell her to clean up her room or assist around the house.

Assertive Statement : “I feel overburdened when you do not pitch in and help keep the house clean and tidy. I understand that you do not like having me remind you to clean your room, but it is a task that needs to be done, and everyone needs to do their part.”

Takeaway : Sometimes, we do not express ourselves because we fear how others react. Assertive people understand that they have no accountability for how the other person chooses to respond – that is entirely on them.

A normal human being will know that we all have needs and desires and should be entitled to express them willingly.

Scenario : Your father wants you to come to his house immediately so you can help him sort through things he wants to sell at a garage sale.

However, you had planned to spend the evening relaxing, taking a calming bath, and just lounging around because you had a rough week at work.

Assertive Statement : “I understand you need help, and I would like to help you. Although today, I need to take care of myself because I am very exhausted and overworked. I can better help you tomorrow. Does that work for you?”

Takeaway : Part of being assertive is caring for oneself and valuing one’s needs just as much as the other person’s. An assertive person says, “I am worthy of this. I deserve this.”

Friendships

Scenario : Your friend asks to borrow $1,000, and you doubt she has a history of defaulting on her financial commitments.

Assertive Statement : “My policy is never to lend money to friends or family members.”

Takeaway : Using the term “policy statement” is a great way to express one’s core values and outline what one will and will not do.

Scenario : Your roommate is yelling and complaining that you are not devoting enough time and attention to the household. She launches into a long list of what she perceives to be your character flaws.

Assertive Statement : “I see you are angry. I hear you saying that you think I should spend more time doing ___. However, I am afraid I have to disagree with you, and here’s why.”

Takeaway : Assertive people do not get caught up in anger or strong emotions. They acknowledge the other person’s thoughts and feelings but frankly express their own.

Spouse/Partner

Scenario : You planned to meet up with your boyfriend to have a nice meal at a restaurant. You get there, but he is late – again.

Every time you make plans, he seems to leave you waiting while he shows up 20-30 minutes after the scheduled meeting time.

Assertive Statement : “Did something happen unexpectedly that made you late? I feel hurt when I have to wait constantly because you are frequently late. It makes me feel uneasy and like I am not a priority for you. Is there something I can do to help you fix this problem?”

Takeaway : Assertive people use “I” statements instead of throwing blame or insults at the other person. Offering to support come up with a solution lets the other person know one cares.

Scenario : Every day when you come home from work, your husband ignores you and continues doing whatever they are doing. He does not acknowledge, greet, or ask you how your day was.

Assertive Statement : “I feel sad when I come home, and you do not seem happy to see me or ask how my day was. I feel lonely and not appreciated.”

Takeaway : Assertive people always state the problem instead of assuming that others know what they think, feel, or need.

The Workplace

Scenario : Your boss wants you to do your co-worker’s report because he has fallen behind schedule, and your boss knows you work efficiently. This has happened multiple times this past month.

Assertive Statement : “This is the sixth time this month I have been given extra work because Steve has been behind on his work. I want to be a team player, but I am stressed when I am overburdened. What can we do to ensure this does not occur again?”

Takeaway : Stating the facts and expressing one’s feelings helps avoid making the other person get their defenses up. Offering to help solve the problem expresses one’s concerns.

Scenario : Your co-worker wants you to come in overtime to help her with her portion of work on a project that is due relatively soon, and she has been putting it off. Meanwhile, you have already completed your project share and have plans outside of work.

Assertive Statement : “I understand you need help with your project. However, I already completed my share and I have plans outside of work that I cannot change. I can give you some advice and pointers, but I will not stay overtime.”

Takeaway : Again, stating the facts helps avoid making the other person get their defenses up. Offering to help in any way is also helpful for the other person.

Take Small Steps, but Stand One’s Ground

One should also be aware that if one has not been assertive in the past, one will come up against resistance when one begins taking steps to stand one’s course.

There may be disputes with family members and friends or tension at work, so it is best that one is prepared for various forms of backlash.

For example, if one is discussing with one’s partner and they interrupt, stop them immediately by calmly saying, “please do not interrupt me when I’m speaking.”

Chances are they will get worked up and possibly argumentative, at this point, one can make it clear that one does not interrupt them when they are speaking, and one would like to be granted the same courtesy.

Depending on what kind of individual they are, this could result in tension, but say they are a family member or one’s partner, they will be willing to work things through and grow together.

It is important to remember to not let these situations dissuade oneself. One might need to sit in their room and cry it out, it can be overwhelming when someone who is used to treating one like a doormat, gets put in their place with one’s newfound voice.

Maintain these new boundaries one has firmly in place, and one will find that they will either adapt or walk away.

If this person walks away, they did not work having around in the first place. This risk one will take any time you make a significant life change.

Overall, communication is vital, and it is an excellent idea to sit down and discuss with those closest to you the fact that one is trying to be more assertive and the reasons for doing so.

By asking for and receiving their support and encouragement, one may discover that one has more people on your side than one would likely expect, which will only help to bolster one’s assertiveness and help one’s reach goals.

Here are some critical elements of assertive communication in relationships that you can take away from this article:

- It is direct, firm, positive, and persistent.

- It consists in exercising personal rights.

- It involves standing up for oneself.

- It promotes an equal balance of power.

- It acts in one’s own best interests.

- It does not include denying the rights of others.

- It consists in expressing necessities and feelings openly and comfortably.

By expressing and communicating in a manner that is consistent with the key elements above, people like you are more likely to cherish lasting and fulfilling positive relationships based on mutual respect.

To have these life-long friendships, partnerships, and relationships, expressing who you are and effectively communicating with others is key to attaining a group of people who will love, respect, and adore you!

The Benefits of Being Assertive

Less stress.

To be honest with ourselves, so much stress can be experienced with either aggressive or passive communication. Likely, one or more people involved in these conversations generally wind up feeling humiliated or threatened.

If one stays on the firm side, one might end up regretting putting one’s need to be heard over the other individual’s right to speak.

However, with assertive communication, you are acknowledging the other person’s feelings and wishes. Still, at the same time, you are openly sharing yours and trying to find the best solution for the situation.

The assertive communication style correlates to very little stress.

Trust is crucial in all of one’s relationships, and being assertive helps one arrive there naturally.

Most of the time, passive communication results in others not taking one seriously, while aggressive behavior leads to resentment.

Being trustworthy in one’s communication significantly builds connection.

More Confidence

When one hides their feelings or interacts with others without caring about what they feel or think, one either lowers one’s self-esteem or builds it on the wrong foundation.

While assertive behavior, on the other hand, assertive behavior demonstrates that one is both brave enough to stand up for one’s rights and in control of what one is saying and, more importantly, how one says it).

One can find the balance between clearly stating one’s needs and allowing the other person to do the same and feel equal.

Better Communication

Last but not least, assertive behavior is excellent for everyone involved.

If one communicates wisely, one can get what one wants out of any interaction and leave the other person fulfilled.

Communication Styles

There are three main communication types: passive, aggressive, and assertive.

In every conversation, our communication style makes it easier or harder for the other person to understand what we mean.

Therefore, we would suffer the consequences if we did not know which communication style to use. Often, this can lead to accidentally offending people or not conveying the point you are trying to make.

Aggressive communication style is a method of expression where individuals assert their opinions, needs, or feelings in a manner that infringes upon the rights of others.

It can involve speaking in a loud, demanding tone, employing harsh or disrespectful language, ignoring others’ viewpoints, or using non-verbal cues like invading personal space.

While it can help achieve personal goals, it often results in strained relationships due to its lack of respect for others.

Aggressive communication can prevent you from having stable friendships because no one enjoys the company of someone who constantly judges, disputes, disagrees, and does not allow others to share their views.

This style can lead to misunderstanding, resentment, and a lack of personal fulfillment, as it inhibits effective interpersonal exchange and self-advocacy.

On the other hand, passive communication may lead to feelings of being misperceived and misheard. You may feel like no one truly hears you or respects your input.

Passive-Aggressive

A passive-aggressive communication style is characterized by indirect expressions of hostility or negativity. Instead of openly expressing feelings or needs, individuals may use sarcasm, silent treatment, procrastination, or subtle sabotage.

This style can create confusion and conflict as the communication is covertly aggressive, making it hard for others to address the real issues, leading to ineffective resolution and strained relationships.

We should all strive for an assertive communication style because it is the best of both worlds.

You not only meet your needs, but you also meet the needs of the person you are engaging with, so everyone is happy. An assertive communication style is a balance between the other two communication styles.

An awareness of assertive communication can also help one handle complex family, friends, and co-workers more efficiently, decreasing drama and stress.

Ultimately, assertive communication empowers one to draw essential boundaries that allow anyone to meet their needs in relationships without excluding others and letting anger and resentment creep in.

Of course, occasionally, it can be challenging to create this habit and stay away from other, less productive communication styles. There needs to be a healthy amount of self-control.

Fortunately, some innovative and easy ways exist to improve your assertive communication skills.

Before this, let us examine why you should prioritize aiming for a more assertive communication style.

What is the difference between assertive communication and passive communication?

Passive communication is an avoidance style that is considered inefficient, as it does not communicate the person’s sentiments. The person will avoid expressing what they mean to evade conflict.

They will prioritize the needs of others over their own and are often taken advantage of. This avoidance causes inner turmoil to build up and may lead to bursts of anger.

Assertive communication is an effective way to communicate with another person honestly and is the recommended style. An assertive communicator is transparent in their intentions and necessities and is firm without becoming aggressive.

They endorse themselves and remain respectful and empathetic to the other person(s).

What is the difference between assertive communication and aggressive communication?

Aggressive communication is volatile, high-emotion, high-energy communication where the communicator is focused on being right.

The opposite of passive, these communicators are only concerned with their gains and will bully and compel others to “win” the conversation.

These communicators are not compassionate and do not appreciate the boundaries of others in the exchange. Again, assertive communication is transparent in intentions and is firm without becoming aggressive.

Respect and boundaries are maintained with every conversation, and keeping emotions in check.

Are assertive communication and dominating the same thing?

No. People trying to “dominate” the person they are interacting with will speak loudly, use physical force, and frequently interrupt the other person. They will blame and embarrass others, and these communicators get enraged quickly.

Their behavior is discourteous, inappropriate, and alienating. This type of communicator is usually unwilling to make compromises in arguments, looms over the other person, and uses direct, lengthy eye contact.

They will make the discussion one-sided and not listen to the other person. Assertive communicators are engaged listeners and keep a calm voice when talking.

They do not escalate the situation, bully, or use manipulation tactics. This communicator creates relationships and does not allow others to exploit them.

These people make a discussion where others feel comfortable joining.

When should assertive communication be used?

Assertive communication involves transparent, honest statements about your beliefs, needs, and feelings. Considering a healthy compromise between aggressive and passive communication is good.

When you communicate assertively, you share your beliefs without judging others for theirs. You endorse yourself when necessary and do it with courtesy and consideration because assertiveness involves respect for your views and those of others. This communication style helps solve conflict collaboratively.

Whether you have a concern you want to discuss with your partner or need to let a co-worker know you cannot offer assistance with a project, assertive communication allows you to express what you need productively and work with the other person to find the best solution.

- Filipeanu, D., & Cananau, M. (2015). Assertive communication and efficient management in the office. International Journal of Communication Research , 5 (3), 237.

- Kolb, S. M., & Griffith, A. C. S. (2009). “I’ll Repeat Myself, Again?!” Empowering Students through Assertive Communication Strategies. Teaching Exceptional Children , 41 (3), 32-36.

- Omura, M., Maguire, J., Levett-Jones, T., & Stone, T. E. (2017). The effectiveness of assertiveness communication training programs for healthcare professionals and students: A systematic review . International journal of nursing studies , 76 , 120-128.

- Pipas, Maria Daniela, and Mohammad Jaradat. “ Assertive communication skills .” Annales Universitatis Apulensis: Series Oeconomica 12.2 (2010): 649.

- Random Quiz

- Search Sporcle

Adjective Open Honest And Direct In Speech Or Writing Especially When Dealing With Unpalatable Matters Crossword Clue

Report this user.

Report this user for behavior that violates our Community Guidelines .

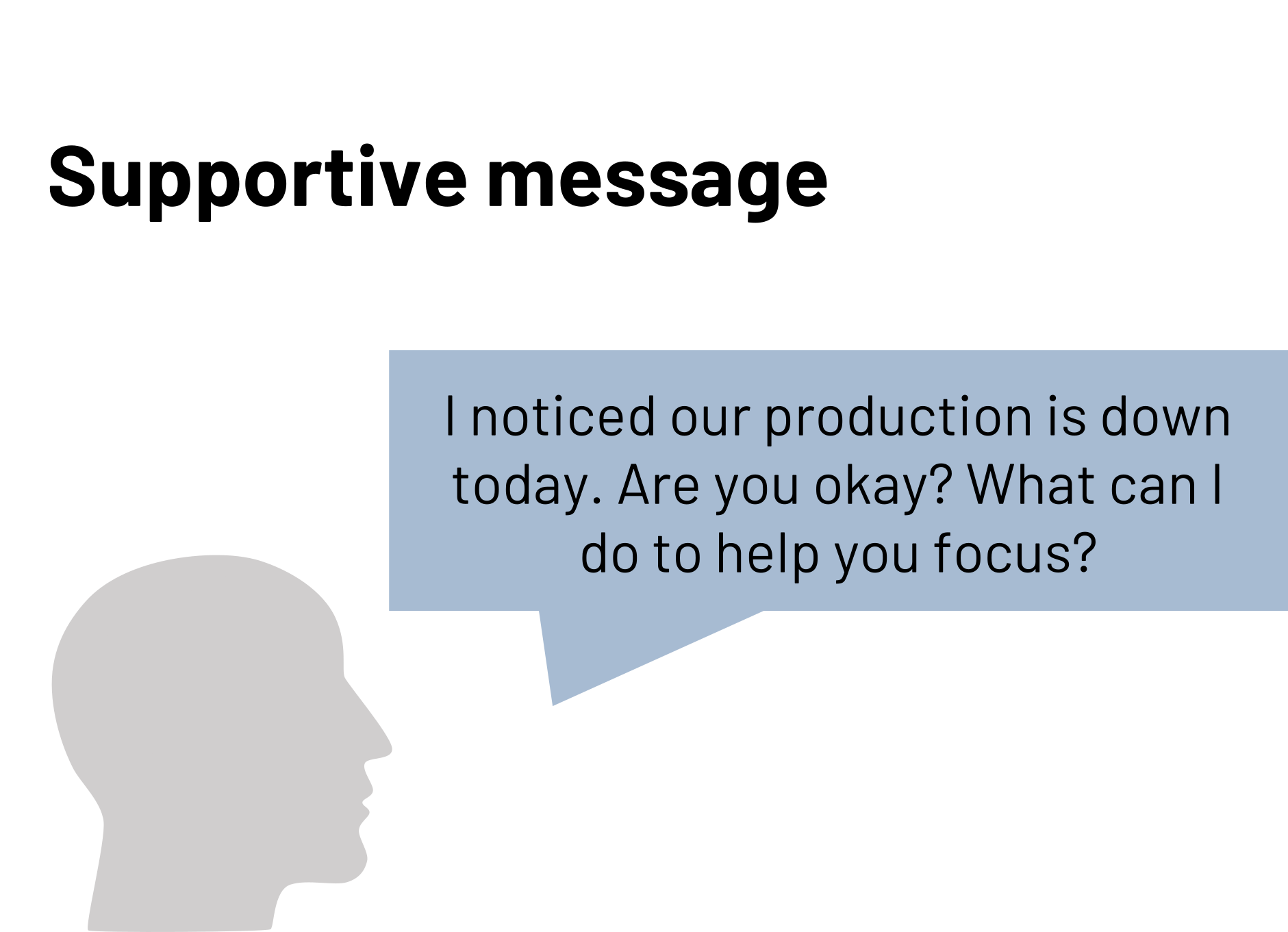

Demonstrating Openness and Honesty

Teaching students openness and honesty provides the skills needed to take on new opportunities, behave with integrity, and build strong, trusting relationships. Openness—the quality of being receptive to new ideas and experiences—is correlated with higher levels of curiosity and increased comfort in new or unfamiliar situations. It is also associated positively with creativity and well-being (“Openness,” 2020).

Honesty—speaking the truth and acting truthfully—can help students communicate ideas sincerely and respectfully, set and recognize boundaries, and build strong relationships. By maintaining openness and honesty, and applying learned social-emotional skills, students and educators will be able to navigate this current situation of distance learning and stay-at-home rules in a positive, healthy manner.

Although being open to new ideas and speaking honestly can be uncomfortable or difficult, engaging in open and honest conversations is more rewarding and socially fulfilling than one might think (Jones, 2018). Honesty connects people more deeply, even when sharing potentially negative information or feedback, and allows space for more openness and a better understanding of what someone is feeling. As children and adults address the recent unprecedented changes in their daily lives, fostering openness and honesty is of critical importance in learning and in relationships. Using their social-emotional skills and encouraging openness and honesty can help students handle unforeseen changes and transitions with a sense of curiosity and ease, and create an honest environment that allows big emotions and anxieties to be named, validated, and properly managed.

Keep in mind the following to help students and families develop openness and honesty.

- Make classrooms and homes “intellectual safe spaces,” that is, where all opinions are heard and respected. Allow children to practice speaking honestly and also to practice respectfully listening to all opinions, even those they may not agree with (Barbour, 2018).

- Teach students to listen and repeat. Have them summarize what the other person says in their own words to show that they are actively listening and understand what was said.

- Demonstrate open body lan-guage. Uncrossed arms, eye contact, and nonverbal af-firmations such as nodding your head show engagement and help facilitate open com-munication. Open body lan-guage also keeps students checked in, remain in the present, and actively listen to what the other person is saying (Gatens, 2020).

Using their social-emotional skills and encouraging openness and honesty can help students handle unforeseen changes and transitions with a sense of curiosity and ease.

Developing openness and honesty instills an intrinsic sense of integrity within students and provides them with the skills necessary to thrive in diverse, dynamic environments. Given the current circumstances in our daily lives, openness and honesty will allow students, their families, and educators to meet these challenges in a positive and healthy way.

References:

- Barbour, B. (2018, August 28). Guiding students to be open to new ideas. Edutopia. Retrieved March 20, 2020, from https://www. edutopia.org/article/guiding-students-be-open-new-ideas

- Gatens, B. (2020). Openness to ideas, perspective and change yields trust in the classroom. Share to Learn. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://blog.sharetolearn.com/curriculum-teaching-strategies/openness-yields-trust-in-classroom/

- Jones, S. M. (2018, September 21). People can afford to be more honest than they think. UChicago News. Retrieved March 20, 2020, from https://news.uchicago.edu/story/people-can-afford-be-more-honest-they-think

- Openness. (2020, March 20). Psychology Today. Retrieved March 20, 2020, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/openness

More From Forbes

Why and how to cultivate honest, expressive communication on your team.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Hasnain Raza is the Vice President of Marketing at Market One , Canada's largest marketing agency for public companies.

It’s no secret that communication is key to a team’s productivity. It’s a core function that managers should master to help keep their teams motivated and happy.

Traditionally, and in an attempt to appear professional and in control, leaders often communicated in a way that sounded premeditated and manufactured.

A new era of internal communication may be emerging. While showing emotion and honesty in the workplace was once seen as a weakness, I believe incorporating genuine emotion into a team’s internal communications could very well be a leader’s secret weapon.

In fact, many studies show that emotions have a significant impact on how people perform, engage and make decisions within their organizations.

In a 16-month study of a long-term care facility published in Administrative Science Quarterly and discussed in the Harvard Business Review (paywall), researchers found that those who worked in units with a strong culture of "companionate love" had lower absenteeism, decreased burnout and increased job satisfaction compared to colleagues in other units. These units also had more satisfied patients.

But how do you create a positive emotional culture? It starts from the top.

Emotions are contagious and, once established, can easily trickle down throughout the company. Being open and transparent at work might seem daunting at first, but I've found that it's integral to building strong relationships and synergy on a team. Here are three things you can do to cultivate honest and expressive communication with your team:

RNC Day 4: Trump Blasts Biden And ‘Crazy Nancy Pelosi’—Despite Promised ‘Unity’ Theme

Google confirms play store app deletion—now just 6 weeks away, every big name urging biden to drop out: second senator goes public.

Create Clear Boundaries

Have you noticed that your team is lacking momentum? Are they feeling burnt out?

This may be due to a lack of boundary-setting. I've found that a failure to create and communicate boundaries can easily lead to feelings of resentment and, ultimately, a decrease in productivity.

It also signals an opportunity to be transparent about your boundaries and allow your team to communicate openly in response. As a leader, it’s your responsibility to share your own personal boundaries with your team and create a space where they feel safe enough to do the same.

Boundaries can exist in many different forms, like boundaries between personal and professional relationships, around work-life balance, or around asking for favors. By making your boundaries known, you are also setting an example and encouraging frequent conversations around boundary-setting, which could decrease the risk of burnout, miscommunication and resentment.

Develop A Structure

There’s a running joke in corporate culture about meetings that “could have been emails.”

Unproductive meetings are a common issue and can often leave teams feeling frustrated or disengaged. If you find yourself in meetings that seem to run on forever, it could be due to a lack of clear structure.

So, how can you change that? Before setting a meeting, think about what you want the meeting to accomplish and make that clear to your attendees. With everyone on the same page, you’ll likely reduce the chances of a meeting getting derailed or spinning out of your control.

If things aren’t panning out the way you were envisioning, don’t be afraid to take a step back and be honest with your team members. Creating that open line of communication will allow you to build more sincere and productive relationships with your colleagues.

Find Your Style

Every person, regardless of the organization they are in, utilizes different communication styles.

As a leader, you need to not only learn how to mitigate conflicts between these different styles but also relay your own communication needs.

Do you tend to give vague directives? Do you like to check in with your employees daily? Do you prefer to give them the freedom to make their own choices?

Once you’re aware of how you like to communicate, you can then learn what expectations you need to set with your team. Setting clear expectations will help you avoid pent-up frustration due to misunderstandings.

At the end of the day, regardless of your communication style, being honest with yourself and your team is the first step to building a strong foundation of trust. When you show honest emotion, your team can get a better understanding of where you are coming from and why you communicate the way you do. It will also likely inspire them to do the same.

Conclusion

You might have heard this before, but: when in doubt, over-communicate . According to a 2019 study commissioned by Dynamic Signal and conducted by Survata ( via GlobalNewswire ), 80% of the U.S. workforce feels stress due to ineffective company communication. Setting communication expectations is the first step to cultivating a transparent workplace with a positive emotional culture.

Transparency and emotional communication may not always be easy conversations to cultivate, but creating an environment in which open communication is encouraged can certainly benefit your team in the long run.

Forbes Communications Council is an invitation-only community for executives in successful public relations, media strategy, creative and advertising agencies. Do I qualify?

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Our content is reader-supported. Things you buy through links on our site may earn us a commission

Join our newsletter

Never miss out on well-researched articles in your field of interest with our weekly newsletter.

- Project Management

- Starting a business

Get the latest Business News

How to foster communication that is honest, clear and direct.

- Pay attention to your communication for a few days, and listen for hedging with understatement, misdirection, or apology. If you hear these behaviors, you might be too soft. If you hear accusations, forceful tone or language, or lots of “you” messages, you might be too tough. To find and maintain that middle ground that is honest, direct, and clear (but short on aggression) consider the following before you speak.

- Consider your intent. What is the purpose of this communication? Is it small talk with peers? Is it corrective in nature? Is it brainstorming? What do you want to get out of this communication? A disciplined but intimidated direct report? Or better understanding and cooperation within your team? Setting your intention ahead of the conversion is a powerful tool for driving your communication behavior.

- Master your timing. If your direct report comes in late, or makes a mistake, you might be tempted to address it immediately. But should you? Who else—customers or coworkers—will overhear your criticism? Better wait for a private moment. Also, what about your emotions? If you are frustrated, that will impair your ability to speak in a fair, impartial way. However, if you tend to be “too nice” or postpone uncomfortable conversations, you might want to make a rule for yourself to deal with issues within the same business day.

- Weigh your words. Words like “always” and “never” beg to be argued with. Critical words like “careless” or “incompetent” will raise defensiveness. Consider searching for wording that is truthful yet neutral. And if you tend to be too nice and indirect, consider—and rehearse if needed—direct words such as, “this report needs to be corrected today.”

- Be aware of your body language. Watch for incongruent body language. If you are a person who smiles all the time, people may find it hard to take you seriously. Conversely, if your face or body language often looks angry or disapproving, your words may be taken as more negative than you mean them to. Strive for a neutral tone, face and body language.

- Tune into listening skills. If you want to build communication rather than just bark out orders, it would be helpful to hone and employ your best listening skills. Ask open-ended questions to hear the other person’s point of view. Listen to what they have to say, how they say it, and what they don’t say.

- Maintain consistency. If you want your communication brand to be “honest and direct,” you will need to continually think before you speak, choose direct words, and tell the truth. Doing these things now and then won’t build your brand, but may just confuse those you deal with, since they don’t know from day to day what to expect from you.

Gail Zack Anderson

How Much Does It Cost To Advertise On Google?

Is your business considering advertising on Google, but you need clarification on the costs? How much should you budget for a successful Google Ads campaign? In this comprehensive guide, we delve into the factors that influence the cost of Google Ads, provide industry-specific cost insights, and offer expert tips on budgeting, bidding, and optimizing your …

All About Advertising and Promotions

© Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD, Authenticity Consulting, LLC. Before you learn more about advertising and promotions, you should get a basic impression of what advertising is. See What’s “Advertising, Marketing, Promotion, Public Relations and Publicity, and Sales?”. Advertising is specifically part of the “outbound” marketing activities, or activities geared to communicate out to the …

Defining the Categories of Marketing

The Categories of Marketing: Advertising, Marketing, and Sales Defined Entered by Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD Also, consider Related Library Topics It’s easy to become confused about categories of marketing terms: advertising, marketing, promotion, public relations and publicity, and sales. The terms are often used interchangeably. However, they refer to different — but similar activities. Some …

Managing Marketing and Public Relations Committees

Effective Management Strategies for Marketing and Public Relations Committees © Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD, Authenticity Consulting, LLC. The vast majority of content on this topic applies to for-profits and nonprofits. This book also covers this topic. Marketing Committees Committees The purpose of the Board Marketing Committee is to ensure ongoing, high-quality marketing. “Marketing” is …

Managing Reputation: Public and Media Relations

Reputation Management 101: Public and Media Relations Strategies © Copyright Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD, Authenticity Consulting, LLC. Public relations activities aim to cultivate a strong, positive image of the organization among its stakeholders. Similar to effective advertising and promotions, effective public relations often depends on designing and implementing a well-designed public relations plan. The plan …

Becoming A Technical Writer-Communicator Review

I am seeing there is still a great interest in people wanting to become Technical Writers. For that reason, I am going to review some steps to become one. If you are currently employed: • write about your job and what the requirements are for that position. • write about all your daily tasks and …

Creating A Knowledge Community

A Technical Writer needs to create a Knowledge Community. How and why we need a Knowledge Community you ask? Being a Technical Writer can be difficult when trying to obtain knowledge. Whom do you consider for contacting, where do you look. How do you decide if you should gather knowledge verbally face-to-face or in meetings, …

Tips for Handling Technical Writer Stress

Everyone gets stressed out at work no matter what your job function. As a Technical Writer, you too will probably have situations at one time or other where you get stressed out as well. In order to avoid communicating less or ineffectively, take a break or slow down for a while. Here are a few …

Likeminded Communication

Trying to communicate technical information to various cultures is not as simple as others may think. For a technical communicator, it requires more than just training, because being moderately acquainted with cultural differences is just not enough. Likeminded A previous post that I had written on communicating globally, noted that ‘Individuals need to understand the …

A Technical Writer Is Different From Other Writers

‘Why?’ The role of Technical Writers possesses a lot of technical knowledge such as in software and data skills, including investigating, researching, and being a middleman between the target audience, management, technical personnel (I.e., programmers, engineers), and others. Being a Technical Writer means being able to gather, communicate, and translate essential and necessary technical information …

Involve and Engage Your Audience 20 Ways

Not long ago I worked with an energetic, creative group who, while focusing on presentation skills, wondered how to best engage their audiences. I asked them what engagement strategies they appreciated when they were in the audience. They had plenty of ideas about engagement techniques that I think any speaker could benefit from. These are …

Tips On Documenting Processes

Numerous types of processes (i.e., business processes) exist in many organizations. Processes specifically involve defining and outlining a sequence of events or systematic movements that are to be followed. These processes need to be documented and identified by the Technical Writer. Benefits Documenting processes • ensures that everyone understands the overall picture of what the …

Communicating Technical Writing Review

It is always good to do a review as some of us might have forgotten the essentials of how to create a document full of technical information for your audience. Another acronym for technical writing could be informational writing or knowledge writing or even instructional writing. Let us start at the beginning. Basics • Build …

Communicating Via Visual Designs

We don’t always realize it, but sometimes we are being told what to do visually. Take these as examples: • A zebra crosswalk on the road – we know to walk within the zebra crossing. • A sign of a bicycle – we know the lane is a bicycle path. • A light switch- we …

Special Tips for Laptop Presentations

If you are presenting, odds are you are using your laptop either to walk the listeners through content in a small group, or projected on a screen to a larger group, or online when speaking with a virtual group. It’s just how we present these days. But so many people stumble over the technology, which …

Privacy Overview

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics Training

- Ethics Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- IFCN Grants

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

How to write with honesty in the plain style

It’s a middle ground between an ornate high style and a low style that gravitates toward slang. write in it when you want your audience to comprehend..

I know how to tell you the truth in a sentence so dense and complicated and filled with jargon that you will not be able to comprehend. I also know — using my clearest and most engaging prose — how to tell you a vicious lie.

This dual reality — that seemingly virtuous plainness can be used for ill intent — lies at the heart of the ethics and practice of public writing.

The author who revealed this problem most persuasively was a scholar named Hugh Kenner, and he introduced it most cogently in an essay entitled “The Politics of the Plain Style.” Originally published in The New York Times Book Review in 1985, Kenner included it with 63 other essays in a book called “Mazes.”

When I began reading the essay, I thought it would confirm my longstanding bias that in a democracy, the plain style is most worthy, especially when used by public writers in the public interest.

A good case can be made for the civic virtues of the plain style, but Kenner, in a sophisticated argument, has persuaded me that some fleas, big fleas, come with the dog.

A disappointing truth is that an undecorated, straightforward writing style is a favorite of liars, including liars in high places. Make that liars, propagandists and conspiracy theorists. We have had enough of those in the 21st century to make citing examples unnecessary. And the last thing I would want to do is to republish pernicious texts, even for the purpose of condemning them.

When rank and file citizens receive messages written in the high style — full of abstractions, fancy effects, and abstractions — their BS detector tends to kick in. That nice term, often attributed to Ernest Hemingway, describes a form of skepticism that many of us need to sense when we are being fooled or lied to. So alerted, you can then dismiss me as a blowhard or a pointy-headed intellectual who works at the Poynter Institute!

If I tell it to you straight, you will look me in the eye and pat me on the back, a person of the people, one of you.

Literary styles and standards shift with the centuries, including the lines between fiction and nonfiction. Among the so-called liars cited by Kenner are famous authors such as Daniel Defoe and George Orwell. Both, he argues, wrote fiction that posed as nonfiction. The way they persuaded us that Robinson Crusoe actually lived or that Orwell actually shot an elephant or witnessed a hanging was to write it straight. That is, to make it sound truthful.

If public writers are to embrace a plain style in an honest way, they must understand what makes it work. Kenner argues:

- That the plain style is a style, even though it reads as plain, undecorated.

- That it is rarely mastered and expressed as literature, except by the likes of Jonathan Swift, H.L. Mencken and Orwell.

- That it is a contrivance, an artifice, something made up to create a particular effect.

- That it exists in ambiguity, being the perfect form of transmission for democratic practices, but also for fictions, fabrications and hoaxes.

- That it makes the writer sound truthful, even when he or she is not.

If you aspire to write in an honest plain style, what are its central components? Let’s give Kenner the floor:

Plain style is a populist style. … Homely diction (common language) is its hallmark, also one-two-three syntax (subject, verb, object), the show of candor and the artifice of seeming to be grounded outside language in what is called fact — the domain where a condemned man can be observed as he silently avoids a puddle and your prose will report the observation and no one will doubt it.

Kenner alludes here to Orwell’s essay in which he observes a hanging and watched the oddity of the condemned man not wanting to get his feet wet as he prepares to climb the steps to the gallows. “Such prose simulates the words anyone who was there and awake might later have spoken spontaneously. On a written page, as we’ve seen, the spontaneous can only be a contrivance.”

The plain style feigns a candid observer. Such is its great advantage for persuading. From behind its mask of calm candor, the writer with political intentions can appeal, in seeming disinterest, to people whose pride is their no-nonsense connoisseurship of fact. And such is the trickiness of language that he may find he must deceive them to enlighten them. Whether Orwell ever witnessed a hanging or not, we’re in no doubt what he means us to think of the custom.

Orwell has been a literary hero of mine from the time I read “Animal Farm” as a child. I jumped from his overt fiction, such as “1984,” to his essays on politics and language, paying only occasional attention to his nonfiction books and narrative essays. I always assumed that Orwell shot an elephant and that he witnessed a hanging, because, well, I wanted to believe it, and assumed a social contract between writer and reader, that if a writer of nonfiction writes a scene where two brothers are arguing in a restaurant, then it was not two sisters laughing in a discotheque.

As to whether Orwell wrote from experience in these cases, I can’t be sure, but he always admitted that he wrote from a political motive, through which he might justify what is sometimes called poetic license.

Writing to reach a “higher truth,” of course, is part of a literary and religious tradition that goes back centuries. When Christian authors of an earlier age wrote the life and death stories of the saints — hagiography — they cared less about the literal truth of the story than a kind of allegorical truth: That the martyrdom of St. Agnes of Rome was an echo of the suffering of Jesus on the cross, and, therefore, a pathway to eternal life.

I write this as a lifelong Catholic without disrespect or irony. Such writing was a form of propaganda and is where we get the word: a propagation of the faith.

Orwell’s faith was in democratic institutions, threatened in the 20th century by tyrannies of the right and the left — fascism and communism. Seeing British imperialism as a corruption, he felt a moral obligation to tell stories in which that system looked bad, including one where, as a member of the imperial police in Burma, he found himself having to kill an elephant, an act he came to regret. Using the plain style, Orwell makes his essay so real that I believe it. In my professional life, I have argued against this idea of the “higher truth,” which does not respect fact, knowing how slippery that fact can be. But Orwell knew whether he shot that elephant or not, so there is no equivocating.

By the onset of the digital age, a writer’s fabrications — even those made with good intent — are often easily exposed, leading to a loss of authority and credibility that can injure a worthy cause. With Holocaust deniers abounding, why would you fabricate a story about the Holocaust when there are still so many factual stories to tell?

There is a powerful lesson here for all public writers: That if I can imagine a powerful plot and compelling characters, I do not have to fabricate a story and sell it as nonfiction. I can write it as a novel and sell it as a screenplay! I have yet to hear an argument that “Sophie’s Choice” is unworthy because it was imagined rather than reported.

I am saying that all forms of writing and communication fall potentially under the rubric of public writing. That includes, fiction, poetry, film, even the music lyrics, labeled as such: “Tell it like it is,” says the song, “Don’t be afraid. Let your conscience be your guide.”

In the end, we need reports we can trust, and even in the age of disinformation and fake news, those are best delivered in the plain style — with honesty as its backbone. Writing in the plain style is a strategy; civic clarity and credibility are the effects.

Here are the lessons:

- When you are writing reports, when you want your audience to comprehend, write in the plain style — a kind of middle ground between an ornate high style and a low style that gravitates toward slang

- The plain style requires exacting work. Plain does not mean simple. Prefer the straightforward over the technical: shorter words, sentences, paragraphs at the points of greatest complexity.

- Keep subjects and verbs in the main clause together. Put the main clause first.

- More common words work better.

- Easy on the literary effects; use only the most transparent metaphors, nothing that stops the reader and calls attention to itself.

- Remember 1-2-3 syntax, subject/verb/object: “Public writers prefer the plain style.”

Want to read more about public writing? Check out Roy Peter Clark’s latest book, “ Tell It Like It Is: A Guide to Clear and Honest Writing ,” available April 11 from Little, Brown.

Trump shooting fuels reflection for journalists who covered Gabby Giffords shooting

‘You don’t report anything unless you know what you’re talking about.’

Opinion | Where’s the official report of Trump’s injuries?

There’s been no statement, release, press conference or medical report. Voters deserve to know how he’s doing, one columnist argues.

Six years later: A retired meteorologist’s reflection on a storm he won’t forget

In 2018, as a series of tornadoes ripped across Iowa, Kurtis Gertz got to work on coverage that likely saved many lives.

RNC fact-check: What Trump VP pick JD Vance got right and wrong in his speech

PolitiFact fact-checked five of Vance’s statements from his 2024 Republican National Convention speech in Milwaukee

Technology has fundamentally changed how reporters cover political conventions — for the better

Technology may not have been an unalloyed good in other areas, but for covering the RNC and DNC, it has been our friend.

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

- Books by Nat Russo

- Recommended Books

- Series Articles

- Blog Awards

Honesty In Writing

Nat Russo August 14, 2014 How-To , Voice , Writing 40 Comments

There are many bits of common writerly wisdom that I tweet on a regular basis using the #writetip hashtag. Some of these nuggets are mine and others are parroting the masters. Most are widely held to be axiomatic, but some are confusing or enigmatic. Such is the limitation of 140 characters.

One of the more confusing writetips deals with honesty in writing .

Above all else, be honest in your writing. Readers sense fakes a mile away. #writetip

Whenever this one comes up in the rotation, I get a flood of questions. I get some heated, sarcastic answers as well, but that’s to be expected from time to time. In general, there’s an overwhelming confusion among aspiring authors about just what it means to “be honest” in one’s writing. I understand this confusion. I once shared it.

It is at once the most simple and most elusive quality to attain. But attaining it is a must! For once you have it, you’ll write with a confidence you’ve never known before. Take this quote from Mark Twain:

About Nat Russo

Nat Russo is the Amazon #1 Bestselling Fantasy author of Necromancer Awakening and Necromancer Falling. Nat was born in New York, raised in Arizona, and has lived just about everywhere in-between. He’s gone from pizza maker, to radio DJ, to Catholic seminarian (in a Benedictine monastery, of all places), to police officer, to software engineer. His career has taken him from central Texas to central Germany, where he worked as a defense contractor for Northrop Grumman. He's spent most of his adult life developing software, playing video games, running a Cub Scout den, gaining/losing weight, and listening to every kind of music under the sun. Along the way he managed to earn a degree in Philosophy and a black belt in Tang Soo Do. He currently makes his home in central Texas with his wife, teenager, mischievous beagle, and goofy boxador.

- More Posts(149)

- Share on Tumblr

Comments 40

Thank you for that insight. I’ve just finished my first novel (it’s with my beta readers now) and I’ve been agonising over what I wrote, ever since I sent it away. My agony has been more extremes, than just about honesty. It has been one question – is this crap or not?

What your article reassured me was that whatever the reaction to my efforts, it is ok…because I wrote it honestly, from inside of me.

My first novel has been like an affirmation of what I always wanted to do but were too scared to actually try, and many of your tips have helped me along the way.

Where do you find the time do so much, on top of writing?

Congratulations on your enormous success. I’ll be honest and admit that initially you used to piss me off with all your news about how well your novel was doing, and then it hit me…I would be absolutely the same if mine took off…WELL DONE THAT MAN!

Cheers Nat.

Thank you so much, Grant! I’m glad you enjoyed the article. And sorry I pissed you off before. 🙂 Haha!

It’s absolutely true that if you’ve written your work honestly, your story will eventually find its audience. It may take time, but it will. People are attracted to brutally honest writers like moths to flame.

Loved the blog Nat, especially the point about self reflection, that really spoke to me as I had a similar revelation not too long ago. It’s something I do more and more the older I get and helps you get to the heart of any matter. And if you can get to the heart of your story (and this is where the honesty comes in as well), you’re well on your way to cracking it! Great stuff.

Thanks, Lee! The more time I spend writing, the more I’m convinced that reflection is one of the ingredients of the “secret sauce”.

I agree in particular about you have to reflected on yourself to be a good writer. I struggle with that sometimes but the truth is you have to be vulnerable if you want to write stories that have an impact on people.

Exactly, Heather. You have to open yourself up and be vulnerable, or else you’ll always pull back right at the point where going forward would have created magic.

This is an amazing post, and probably cuts to the heart of what distinguishes mediocre writing from the good.

I’m really struggling with aspects of several of these right now. I’m writing historical fantasy based on a particularly awful conflict and find myself shying away from violence- not even anything very graphic.

I’m also finding it difficult to put my favorite characters through any significant pain , or have them behave in any way that’s unsavory. It seems I’m trying to avoid going to any and all dark places.

I know it’s because I’m afraid of what I’ll find, but there is no point in trying to tell this story if I insist on leaving out any ugliness.

So true, Christina! You have to dig down and find the strength to explore that darkness.

I have a particularly gruesome scene in Necromancer Awakening, where I put my main character through…well…Hell, really. By the end of it, he’s literally asking for death. That was a difficult one to write. I found that the emotional darkness of my past allowed me to imbue the physical reality of the scene with all the pain I was feeling.

The past can be a treasure trove of emotional expression, if we’re brave enough to go digging in the dirt and explore its depths.

I agree wholeheartedly – but a curious thing happened to me. I decided to re-publish my first two (linked) historical novels from c1990, and began to reflect on that time. So many odd coincidences had occurred in connection with research, writing and publication of same, I thought it would make an interesting memoir. Oh boy! What a revelation to yours truly – that was when I was able to see where those novels had really come from. Yes – from me. As much from my experience of life as my research. They became bestsellers back in the day – and I guess its the emotional honesty as much as the story-line that appealed to people. It was scary though – so much so, I didn’t publish the memoir for fear I’d never write another novel! But like you, I’ve been saying the similar things to aspiring writers. That honesty in the writing is what lifts a story above the mundane.

Ann, thank you so much for sharing that!

When I read over old stories I’ve written, the content I find never ceases to amaze me. Even though we research topics that are story related, we tend to do so with a focus that comes from our life experiences. And when we later inject that research into our story, it’s done so in a way that channels whatever we’ve got going on at the time. 🙂

I’ve noticed even in works-in-progress that my subconscious mind is alive and well. As much of a craft as writing is (and I’m a firm believer we can learn and improve), there is still so much mystery. But I suppose that’s part of what keeps us coming back to the keyboard.

At least I can say it sure isn’t the money… 🙂 Haha!

A wonderful post, managing the impossible: breaking down what honesty means to professional liars! 😀

As you say, it all starts with us being true to ourselves. Whenever we start censoring ourselves, we weaken our voice and betray our readers and our story.

Thank you for another great post!

Haha! We are definitely professional liars! 🙂

I struggled with this one for a while, because “honesty in writing” is one of those ephemeral things that we just sort of know when we see it. I worried over trying to define it, but so many aspiring authors were asking about it, that I had to give it a shot!

Pingback: Writing Links…8/18/14 | TraciKenworth's Blog

Great, great, post. I hear you.

I’ve been yanked to the woodshed and had my ass set straight. Not much else I can say except thanks for taking time to put your thoughts and experience on the page here.

Spot-on, my man.

Thanks, Terry! I’ve been to that woodshed a few times myself. I always came out better for it. 🙂

NAILED IT! This is the single best blog post on writing I’ve ever read. I’ve felt so often that a lot of published books fell shy of the mark because the author was holding back. Thank you for writing this, Nat! Definitely sharing.

Thank you so much for those kind words, Danielle. And thank you for sharing the article!

Absolutely brilliant post! Great tips here, some I definitely need to remember when it comes to writing my next project! 🙂

Thank you, Mishka!

There are doors I don’t feel comfortable (yet) in opening with my writing. My journal even scares me off occasionally. I’m working on it. Good to know I’m not alone. Kat

You’re definitely not alone, Kat! Keep at it!

Hi Nat, we met on twitter. I’m a fellow writer, and I found this article to be very helpful. I agree a reader can tell if the author is not being honest with their writing. It’s something that I will make sure to keep in mind as I am writing my first novel. I’ve also linked this article to my facebook author page, and given you credit for it 🙂 hope it helps other writers out there!

My Twitter is @qamrosh_khan By the way 🙂

Thanks so much, Qamrosh! I’m glad you found the article helpful!

I completely agree with you here. I’ve only recently tried my hand at the ‘writing for money’ thing, but even I like those stories less than my true stories. I have always written just for me, after I was inspired by a performance or just stories that came from within me. Over the last year I’ve read a lot about how other people make money writing and selling erotica. So I tried it as well. To me, these stories just don’t work. They’re not true, the characters are too flat and they don’t make me any money. The only stories that I do sell are those that were true from within, even though they’re not about billionaires or bikers or fairy tales. It is funny to read stories that I have written a long time ago. It makes me wonder what I was writing or doing at the time, because my language is so different. And even though I am aware of it, even I need to remember to make life harder for my characters. They do not need to be in bed by midnight. Instead of something happening the next day around lunch time, it can happen at 3 am in the morning, no matter how inconvenient and tiresome that would be. It is something I need to be aware of and I need to take distance from now and then. Thank you for your article.

Thanks for stopping by, Liz!

You hit the nail on the head. If you’re writing something you’re not passionate about, the readers will know. Everything you write will feel lifeless because there’s no part of you in it.

Just to add a note to Jumping on the Bandwagon… I think it’s important to respect the genre you’re writing in. If you don’t read and enjoy YA/SF/romance/etc. then DON’T try to write it. You will be wasting your time.

Good point, Nicole. I think a writer has a responsibility to do some due diligence when it comes to research. Without at least some knowledge of the genre, you’ll never know which tropes work, which are overused, etc.

Thank you for this post! It was right on point. Honesty in writing is something I strive to accomplish in my own stories! 🙂

It can be a difficult thing to achieve for many, but I think it’s because the subject can be so hard to nail down. I’m glad you enjoyed the article!

It was great advice. Thanks for posting 🙂

Hey Nat…I came upon this post while researching how to be more honest in my songwriting. I’ve attempted to write longer and do very well with short stories, anything more than that though I just loose steam. I’ve been writing songs for about 20 years or so. I write a lot so can put together a pretty good story when I’ve finished one. People like the story aspect to it, the narrative, but I find that most of my songs have a hint of cheese to them. A guy like Tom Waits for instance, his writing rings true. It sounds like it comes from a place full of broken glass and lopped off fingers, real pain. He does it though without leaving you feel like you want to actually kill yourself, there is a certain optimism to it. Its like even though there’s all this crap out there, he’s going to machine right through because he doesn’t give a shit and thats whats cool about it. HST wrote like that too. Dylan writes like that. I’d like to write like that but when I make that attempt to speak that kind of truth it comes out as bad cheese. Like you said its about finding your truth and not trying to emulate some else’s. I journal just about every day and thats where its all truth, but you can’t put that down into a song… isn’t it too personal and really does anyone give a shit about my issues? Isn’t that what FB is for? Tripe indeed. Anyway i’m sure i’ll find my truth and get down to the depths of my being and bring something up that doesn’t stink, but I haven’t gotten there yet. Thanks for the thoughts though, they all apply to writing lyrics as well. Cheers.

Thanks, Joe!

The way I look at is that I represent a statistically significant portion of the population. So, *I* am my target audience. Turning this around on your songwriting, *you* are your target audience. The best advice I ever received was “be vulnerable”. I imagine that’s even more true for songwriters, because music touches the soul in a way that few other art forms do.

Thank you for an important piece in this big puzzle I’m trying to solve! 😉

While I was reading your post, I was clinging for that last point about emotions! I totally get why you saved it for the end. A couple of weeks ago I had an insight that gave me the creeps. I realized that the process of feeling (actively! consciously!), and to explore one’s own world of feelings might belong to the most underestimated aspects in the lives of so many human beings. I also spent years in my head trying to figure out so many things – and yes, it can be a blessing today, and a curse tomorrow. But there’s a lot more to it. Many people spend way too much time thinking, pondering, instead of trying to establish a stronger connection between their perception/actions/behavior and their feelings! It’s as if the mind is trapped in between, always trying to make sense of the world as an intermediary, with us being trapped in it! Besides, feelings are never constant, there’s always ups and downs, but compared with thoughts, which can be thought and communicated, feelings can be felt and expressed!

Greetings from Germany, keep up the good work!

Thanks so much for stopping by, Stevie! I lived in Germany (Viernheim) from 2003 – 2006 working as a contractor for the US Army in Heidelberg. I miss it so much! I’d move back in a heartbeat. Such a beautiful country!

It is so true about the power of reflection being underestimated. I was fortunate to pick up the regular practice while in the seminary. The Benedictine monks were definitely a reflective group of individuals!

I’m glad you enjoyed the article!

Nat, I attended the first session of a memoir writing workshop the other day and when I read a short piece I wrote about an incident in my childhood where I got caught making mischief. It was not particularly traumatic, just a memory of one of the first times I recall feeling guilty. The workshop leader said “Your writing is brilliant. It’s the kind of writing that sells. But it’s not honest. You have to make yourself vulnerable.” A few others in the group nodded, so I asked, “What do you mean by ‘not honest’?” Nobody spoke up except the leader, who said, “You need to put yourself in a dark room and light candles. Meditate.” Which was insulting since I’ve done that for years, and I keep a journal, and I blog. I’m not a dunce when it comes to self-reflection and I felt belittled. Now I’m not sure if I belong in the workshop. Your article is great but I don’t see myself in it, so now what? And how can my writing be “brilliant” or “the kind…that sells” if it’s “not honest”? Help!