Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

To Read bell hooks Was to Love Her

bell hooks taught the world two things: how to critique and how to love. Perhaps the two lessons were both sides of the same coin. To read bell hooks is to become initiated into the power and inclusiveness of Black feminism whether you are a Black woman or not. With her wide array of essays of cultural criticism from the 1980s and 1990s, hooks dared to love Blackness and criticize the patriarchy out loud; she was generous and attentive in her analysis of pop culture as a self-proclaimed “bad girl.” Sadly, the announcement of her death this week, at 69 , adds to a too-long list of Black thinkers, artists, and public figures gone too soon. While many of us feel heavy with grief at the loss of hooks and her contributions to arts, letters, and ideas, we are also voraciously reading and rereading both in mourning and celebration of her impact as a critical theorist, a professor, a poet, a lover, and a thinker.

As a professor of Black feminisms at Cornell University, where I often teach classes featuring bell hooks’s work, I see a syllabus as having the potential to be a love letter, a mixtape for revolution. hooks’s voice was daring, cutting, and unapologetic, whether she was taking Beyoncé and Spike Lee to task or celebrating the raunchiness of Lil’ Kim. What hooks accomplished for Black feminism over decades, on and off the page, was having built a movement of inclusively cultivated communities and solidarity across social differences. Quotes and ideas of Black feminist thinkers tend to circulate across the internet as inspirational self-help mantras that can end up being surface-level engagements, but as bell hooks shows us, there has always been a vibrant radical tradition of Black women and femmes unafraid to speak their minds. bell hooks was the prerequisite reading that we are lucky to discover now or to return to as a ceremony of remembrance. Here are nine texts I’d suggest to anyone seeking to acquaint or reacquaint themselves with her work.

Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981)

Publishing over 30 books over the course of her career, perhaps the most well-known is her first, Ain’t I a Woman. Referencing Sojourner Truth’s famous words, hooks drew a direct line between herself and the radical tradition of outspoken Black women demanding freedom. Before Kimberlé Crenshaw coined “intersectionality” in 1991, hooks exemplified the importance of the interlocking nature of Black feminism within freedom movements, weaving together the histories of abolitionism in the United States, women’s suffrage, and the Civil Rights era. She refused to let white feminism or abolitionist men alone define this chapter of America’s past. Finding power and freedom in the margins, she lived a feminist life without apology by centering Black women as historical figures.

Keeping a Hold of Life: Reading Toni Morrison’s Fiction (1983)

To read bell hooks is to become enrolled as a student in her extensive coursework. Keeping a Hold of Life shows us her student writing and another side of her political formation as Black feminist literary theorist. hooks earned her Ph.D. from University of California Santa Cruz in 1983 despite having spent years teaching literature beforehand, and in her dissertation she analyzes two novels by Toni Morrison, The Bluest Eye and Sula, celebrating both books’ depictions of Black femininity and kinship. For those who are students, it may be encouraging to see hooks’s dedication to learning: Before she got her degree, she had already published a field-defining text. But that wasn’t the end of her scholarly journey by a long shot.

Black Looks : Race and Representation (1992)

I love teaching the timeless essay “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” from this collection above all because it is the first one of hers I read as a college sophomore. In it, she reflects on what she overhears as a professor at Yale about so-called ethnic food and interracial dating. In some ways, the through-line of hooks’s writing can be summed up here, in the way she examines what it means to consume and be consumed, especially for women of color. In another essay from the collection, “The Oppositional Gaze,” hooks taught her readers the subversive power of looking , especially looking done by colonized peoples; drawing on the writings of Frantz Fanon, Michel Foucault, and Stuart Hall, she grappled with the power of visual culture and its stakes for domination in the lives of Black women, in particular. (She mentions that she got her start in film criticism after being grossed out by Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It .) Her criticism shaped feminist film theory and continues to be celebrated as a crucial way to understand the politics of looking back.

Teaching to Transgress: Education As the Practice of Freedom (1994)

bell hooks was a diligent student of Black feminism, and she was more than happy to pass along what she learned, having taught at various points during her career at the University of Southern California, the New School, Oberlin College, Yale University, and CUNY’s City College. In turn, she often reflected on what she learned from teaching in her writings. In this volume, hooks contributes to radicalizing education theory in ways that even now have been understated: She understood schooling as a battleground and space of cultivating knowledge, writing that “the classroom remains the most radical space of possibility.” In 2004, she returned to her home state, Kentucky, for her final teaching post at Berea College, where the bell hooks Institute was founded in 2014 and to which she dedicated her papers in 2017.

“ Hardcore Honey: bell hooks Goes on the Down Low With Lil’ Kim ,” Paper Magazine (1997)

In this 1997 interview, hooks vibes with Lil’ Kim and probes the rapper’s politics of desire, sex work. It’s an example of how she was invested in remaining part of the contemporary conversations around Black life and feminine sexuality. Though she described Lil’ Kim’s hyperfemme aesthetic as “boring straight-male porn fantasy” and wondered out loud who was responsible for the styling of her image as a celebrity and part of the Notorious B.I.G.’s Junior M.A.F.I.A. (“the boys in charge”), she defends Lil’ Kim against the puritanical attacks that she notes have been made against Black women time and again: In hooks’s opening question, she tells Lil’ Kim, “Nobody talks about John F. Kennedy being a ho ’cause he fucked around. But the moment a woman talks about sex or is known to be having too much sex, people talk about her as a ho. So I wanted you to talk about that a little bit.”

All About Love: New Visions (2000)

hooks was especially prolific during the 1990s, publishing about a book a year. The early aughts marked a shift in her intellectual focus away from cultural theory and toward love as a radical act. In this book, she details her personal life, drawing on romantic experiences and what she learned from experiences with boyfriends. With words from 20 years ago that remain trenchant to this day, hooks writes, “I feel our nation’s turning away from love … moving into a wilderness of spirit so intense we may never find our way home again. I write of love to bear witness both to the danger in this movement, and to call for a return to love.” For her, love was not a mere sentiment but something deeply revolutionary that should inform all of Black feminist thought.

“ Beyoncé’s Lemonade is capitalist money-making at its best ,” The Guardian (2016)

In bell hooks’s scathing review of Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade , she took issue with what she perceived as the singer’s commodification of Black sexualized femininity as liberatory. She calls out Beyoncé’s branding and links the legacy of the auction block to what hooks sees as a repetition of the valuation of Black women’s sexualized bodies, warning of the dangers of circulating such images as faux sexual liberation, dictated by capitalist marketing dollars. “Even though Beyoncé and her creative collaborators daringly offer multidimensional images of black female life,” hooks wrote, “much of the album stays within a conventional stereotypical framework, where the black woman is always a victim.” (As was to be expected, the Beyhive did not take kindly to the critique, and it remains an ideological fault line for many of the singer’s fans.)

Happy to Be Nappy (2017)

While most likely first encountered the writings of bell hooks in a college seminar on feminism or decolonization, some were introduced to bell hooks in their early years, during bedtime stories. Understanding self-esteem and image for Black children as deeply political and encoded in the way they view their hair, she wrote a children’s book for them, Happy to Be Nappy. Remembering the impact of the Doll Test — the 1940s psychological experiment cited by the NAACP lawyers behind Brown v. Board of Education , where Black children were observed to assign positive qualities to white dolls and negative ones to Black dolls — and how important representation is, writing this book was a radical act of love.

Appalachian Elegy: Poetry and Place (2012)

From interviews to cultural criticism to academic dissertations, bell hooks did not limit herself to a singular form of writing. She was promiscuous in genre, and her approach was to say whatever needed urgent saying about the interlocking structure of patriarchy, capitalism, and racism — however it needed to be said. Reading one of her final books, a poetry collection, helps us to return with her to Kentucky, where she spent her last years. She loved the expanse of the Black diaspora, but she held close the U.S. South, particularly Black Appalachia. Here, she paints in words the rural landscape and its local ecologies, where stolen land and stolen lives converge, touching on how the landscape of the mountains has been home to people like her, whom she describes as “black, Native American, white, all ‘people of one blood.’” It is a literary homecoming that frames her homegoing. To truly read bell hooks necessitates rereading her again and again, and this act forms its own ritual of elegy, of celebrating the life of someone whose foundational impact cannot be overstated.

- reading list

- section lede

Most Viewed Stories

- The Disappearing of Rose Hanbury

- Cinematrix No. 108: July 12, 2024

- Zach Bryan Hits His Limit

- The 15 Best Movies and TV Shows to Watch This Weekend

- Who Are Claim to Fame ’s Celeb Family Members?

- The Real Housewives of Orange County Premiere Recap: Shannon Storms A-Brewin’

- The Boys Recap: Lee Harvey Oswald

Editor’s Picks

Most Popular

What is your email.

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Perspective

With the death of bell hooks, a generation of feminists lost a foundational figure.

Lisa B. Thompson

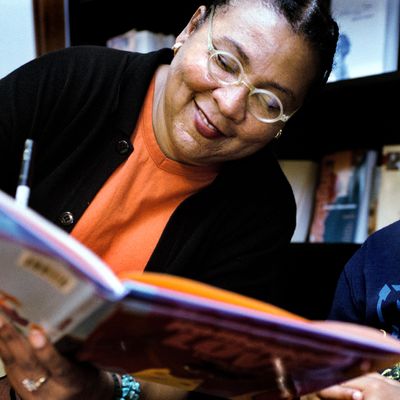

Author and cultural critic bell hooks poses for a portrait on December 16, 1996 in New York City, New York. Karjean Levine/Getty Images hide caption

Author and cultural critic bell hooks poses for a portrait on December 16, 1996 in New York City, New York.

"We black women who advocate feminist ideology, are pioneers. We are clearing a path for ourselves and our sisters. We hope that as they see us reach our goal – no longer victimized, no longer unrecognized, no longer afraid – they will take courage and follow." bell hooks, Ain't I a Woman

Arts & Life

Trailblazing feminist author, critic and activist bell hooks has died at 69.

There are well-worn bell hooks books scattered throughout my library. She's in nearly every section – race, class, film, cultural studies – and, as expected, her books take up an entire shelf in the feminism section. I doubt I would have survived this long without her work, and the work of other Black feminist thinkers of her generation, to guide me. I've retrieved every bell hooks book today, and the unwieldy stack comforts me as I assess the impact of her loss.

If you ever heard hooks speak, it would come as no surprise that she first attended college to study drama, as she recounted in a 1992 essay. In the 1990s she blessed my college campus for a week, and I was mesmerized by lectures that were deliciously brilliant yet full of humor. Her banter with the audience during the Q&A floated easily between thoughtful answers, deep questioning and sly quips that kept us at rapt attention. Her words garner just as much attention on the page. She was a prolific writer, and her intellectual curiosity was boundless.

Discovering bell hooks changed the lives of countless Black women and girls. After picking up one of her many titles – Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center; Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics; Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism – the world suddenly made sense. She reordered the universe by boldly gifting us with the language and theories to understand who we were in an often hostile and alienating society.

She also made clear that, as Black women, we belonged to no one but ourselves. A bad feminist from the start, hooks was clearly uninterested in being safe, respectable or acceptable, and charted a career on her own terms. She implored us to transgress and struggle, but to do so with love and fearlessness. Her brave, bold and beautiful words not only spoke truth to power, but also risked speaking that same truth to and about our beloved icons and culture.

As we traversed hostile spaces in academia, corporate America, the arts, medicine and sometimes our own families, hooks not only taught us how to love ourselves, but also insisted that we seek justice. She helped us to better understand and, if necessary, forgive the women who birthed and raised us. She claimed feminism without apology, and encouraged Black women in particular to embrace feminism, and to do more than simply identify their oppression, but to envision new ways of being in the world. She called on us to honor early pioneers such as Anna Julia Cooper and Mary Church Terrell, who first claimed the mantle of women's rights.

The lower-case name bell hooks published under challenged a system of academic writing that historically belittled and ignored the work of Black scholars. She also used language that was as plain and as clear as her politics. While her writing was deeply personal, often carved from her own experiences, her ideas were relentlessly rigorous and full of citations—even though she eschewed footnotes, another refusal of the academy's standards that endeared her to those of us determined to remake intellectual traditions that denied our very humanity.

Rejecting footnotes seemed to symbolize the fact that the knowledge hooks most valued could not fit into those tiny spaces. Her writing style hinted at the fact that her ideas were always more expansive than even her books could hold. While there were no footnotes, her books were love notes to a people she loved fiercely.

No matter where she taught or lived, bell hooks always kept Kentucky and her family ties close. She frequently claimed her southern Black working-class background and an abiding love for her home. Although she was educated at prestigious schools, she always spoke with the wisdom and wit of our mothers, grandmothers and aunties. Her return to the Bluegrass State and Berea College towards the end of her career has a narrative elegance. A generation of feminists has lost a foundational figure and a beloved icon, but her legacy lives on in her writing, which will provide sustenance for generations to come.

Lisa B. Thompson is a playwright and the Bobby and Sherri Patton Professor of African & African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Follow her @drlisabthompson on Twitter and Instagram .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Revolutionary Writing of bell hooks

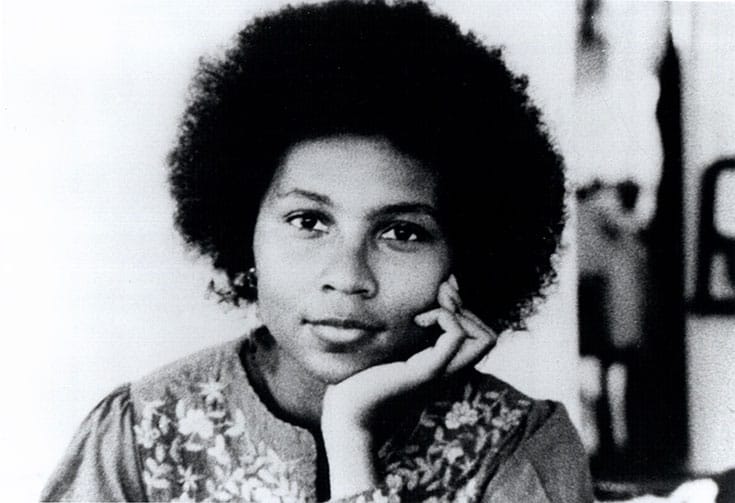

Before she became bell hooks, one of the great cultural critics and writers of the twentieth century, and before she inspired generations of readers—especially Black women—to understand their own axis-tilting power, she was Gloria Jean Watkins, daughter of Rosa Bell and Veodis Watkins. hooks, who died on Wednesday, was raised in Hopkinsville, a small, segregated town in Kentucky. Everything she would become began there. She was born in 1952 and attended segregated schools up until college; it was in the classroom that she, eager to learn, began glimpsing the liberatory possibilities of education. She loved movies, yet the ways in which the theatre made us occasionally captive to small-mindedness and stereotype compelled her to wonder if there were ways to look (and talk) back at the screen’s moving images. Growing up, her father was a janitor and her mother worked as a maid for white families; their work, rife with minor indignities, brought into focus the everyday power of an impolite glare, or rolling your eyes. A new world is born out of such small gestures of resistance—of affirming your rightful space.

In 1973, Watkins graduated from Stanford; as a nineteen-year-old undergraduate, she had already completed a draft of a visionary history of Black feminism and womanhood. During the seventies, she pursued graduate work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of California, Santa Cruz. In the late seventies, she began publishing poetry under the pen name bell hooks—a tribute to her great-grandmother, Bell Blair Hooks. (The lowercase was meant to distinguish her from her great-grandmother, and to suggest that what mattered was the substance of the work, not the author’s name.) In 1981, as hooks, she published the scholarship she began at Stanford, “ Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism ,” a landmark book that was at once a history of slavery’s legacy and the ongoing dehumanization of Black women as well as a critique of the revolutionary politics which had arisen in response to this maltreatment—and which, nonetheless, centered the male psyche. True liberation, she believed, needed to reckon with how class, race, and gender are facets of our identities that are inextricably linked. We are all of these things at once.

In the eighties and nineties, hooks taught at Yale University, Oberlin College, and the City College of New York. She was a prolific scholar and writer, publishing nearly forty books and hundreds of articles for magazines, journals, and newspapers. Among her most influential ideas was that of the “oppositional gaze.” Power relations are encoded in how we look at one another; enslaved people were once punished for merely looking at their white owners. hooks’s notion of a confrontational, rebellious way of looking sought to short-circuit the male gaze or the white gaze, which wanted to render Black female spectators as passive or somehow “other.” She appreciated the power of critiquing or making art from this defiantly Black perspective.

I came to her work in the mid-nineties, during a fertile era of Black cultural studies, when it felt like your typical alternative weekly or independent magazine was as rigorous as an academic monograph. For hooks, writing in the public sphere was just an application of her mind to a more immediate concern, whether her subject was Madonna, Spike Lee, or, in one memorably withering piece, Larry Clark’s “Kids.” She was writing at a time when the serious study of culture—mining for subtexts, sifting for clues—was still a scrappy undertaking. As an Asian American reader, I was enamored with how critics like hooks drew on their own backgrounds and friendships, not to flatten their lives into something relatably universal but to remind us how we all index a vast, often contradictory array of tastes and experiences. Her criticism suggested a pulsing, tireless brain trying to make sense of how a work of art made her feel. She modelled an intellect: following the distant echoes of white supremacy and Black resistance over time and pinpointing their legacies in the works of Quentin Tarantino or Forest Whitaker’s “Waiting to Exhale.”

Yet her work—books such as “ Reel to Real ” or “ Art on My Mind ,” which have survived decades of rereadings and underlinings—also modelled how to simply live and breathe in the world. She was zealous in her praise—especially when it came to Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust,” a film referenced countless times in her work—and she never lost grasp of how it feels to be awestruck while standing before a stirring work of art. She couldn’t deny the excitement as the lights dim and we prepare to surrender to the performance. But she made demands on the world. She believed criticism came from a place of love, a desire for things worthy of losing ourselves to.

She reached people, and that’s what a generation of us wanted to do with our intellectual work. She wrote children’s books ; she wrote essays that people read in college classrooms and prisons alike. Picking up “Reel to Real” made me rethink what a book could be. It was a collection of her film essays, astute dissections of “Paris Is Burning” or “Leaving Las Vegas.” But the middle portion consists of interviews with filmmakers like Wayne Wang and Arthur Jafa, where you encounter a different dimension of hooks’s critical persona—curious, empathetic, searching for comrades. “Representation matters” is a hollow phrase nowadays, and it’s easy to forget that even in the eighties and nineties nobody felt that this was enough. She was at her sharpest in resisting the banal, market-ready refractions of Blackness or womanhood that represent easy, meagre progress. (One of her most famous, recent works was a 2016 essay on Beyoncé’s self-commodification , which provoked the ire of the singer’s fans. Yet, if the essay is understood within the broader context of hooks’s life and intellectual project, there are probably few pieces on Beyoncé filled with as much admiration and love.)

This has been a particularly trying time for critics who came of age in the eighties and nineties, as giants like hooks, Greg Tate , and Dave Hickey have passed. hooks was a brilliant, tough critic—no doubt her death will inspire many revisitations of works like “Ain’t I a Woman,” “ Black Looks ,” or “ Outlaw Culture .” Yet she was also a dazzling memoirist and poet. In 1982, she published a poem titled “in the matter of the egyptians” in Hambone , a journal she worked on with her then partner, Nathaniel Mackey . It reads:

ancestral bodies buried in sand sun treasured flowers press in a memory book they pass through loss and come to this still tenderness swept clean by scarce winds surfacing in the watery passage beyond death

In 2004, hooks returned to Kentucky to teach at Berea College, where she also founded the bell hooks Institute. Over the past two decades, hooks’s published criticism turned from film and literature to relationships, love, sexuality, the ways in which members of a community remain accountable for one another. Living together was always a theme in hooks’s work, though now intimacy became the subject, not the context. Much like the late Asian American activist and organizer Grace Lee Boggs , who turned to community gardening in later years, hooks’s twenty-first-century writings about love as “an action, a participatory emotion,” and companionship were prophetic, a return to the basis for all that is meaningful. The social and political systems around us are designed to obstruct our sense of esteem and make us feel small. Yet revolution starts within each of us—in the demands we take up against the world, in the daily fight against nihilism.

“If I were really asked to define myself,” she told a Buddhist magazine in the early nineties, “I wouldn’t start with race; I wouldn’t start with blackness; I wouldn’t start with gender; I wouldn’t start with feminism. I would start with stripping down to what fundamentally informs my life, which is that I’m a seeker on the path. I think of feminism, and I think of anti-racist struggles as part of it. But where I stand spiritually is, steadfastly, on a path about love.”

New Yorker Favorites

- Some people have more energy than we do, and plenty have less. What accounts for the difference ?

- How coronavirus pills could change the pandemic.

- The cult of Jerry Seinfeld and his flip side, Howard Stern.

- Thirty films that expand the art of the movie musical .

- The secretive prisons that keep migrants out of Europe .

- Mikhail Baryshnikov reflects on how ballet saved him.

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

bell hooks – Ideas for Social Justice

By Commons Volunteer Librarian , E. T. Smith

bell hooks made significant contributions to the theory and practice of social justice. This article summarises three key concepts and provides a guide to her many writings as well as videos and audio of presentations and interviews.

Introduction

bell hooks (1952-2021) chose this name, and styled it in lower-case, in an effort to focus attention on the substantive ideas within her writing, rather than her identity as an isolated individual. To situate those ideas, bell hooks drew on academic scholarship and popular culture as well as her relevant personal perspectives: especially as a Black woman living in America; as an educator and activist; and as the first in her family to gain a university education.

Many of the ideas articulated by bell hooks have resonated widely. Of these, my reflection focuses on her contributions to three concepts that have been influential in social justice movements:

Intersecting structures of power

- Practising love, a verb, is a pathway to justice

Teaching/learning as activism

To help contextualise the broader impact of these and other ideas within bell hooks’ 40+ books and other writings, I’ve included a selection of additional resources, sorted by type:

Resource collections featuring bell hooks

Presentations, interviews, & conversations, additional references.

But first, a sample of memorials to honour the range and depth of appreciation for bell hooks’ contributions to social justice movements:

- Tributes flow for ‘giant, no nonsense’ feminist author, educator, activist and poet bell hooks, ABC News (Australia), 2021

- Remembering bell hooks & Her Critique of “Imperialist White Supremacist Heteropatriarchy” video report by Democracy Now , 2021

- We’ll Never Be Done Learning From bell hooks , article for The Cut by Bindu Bansinath, 2021

- For bell hooks, beloved scholar , remembrance article for the Gay City News by Nicholas Boston, 2021

- Memorial notice for bell hooks in the Daily Nous , 2021

- bell hooks passes, leaving legacy of activism and progress , article for ArtCritque by Brandon Lorimer, 2021

- The Revolutionary Writing of bell hooks , article in The New Yorker by Hua Hsu, 2021

- What bell hooks taught us , the Giro , 2021

- bell hooks, We Will Always Rage On With You , article for Truthout by George Yancy, 2021

- In case it helps – bell hooks asé , blog post by adrianne maree brown, 2021

Exploring bell hooks’ contributions to three social justice concepts

bell hooks often wrote about how race, class, capitalism, and gender function together as interdependent power-structures. This included developing an influential analysis of how these interlocking power structures converge to produce and perpetuate the dominance of imperialist-white-supremacist-capitalist-heteropatriarchy .

Fundamentally, if we are only committed to an improvement in that politic of domination that we feel leads directly to our individual exploitation or oppression, we not only remain attached to the status quo but act in complicity with it, nurturing and maintaining those very systems of domination. Until we are all able to accept the interlocking, interdependent nature of systems of domination and recognize specific ways each system is maintained, we will continue to act in ways that undermine our individual quest for freedom and collective liberation struggle. – Love as the Practice of Freedom , in Outlaw Culture , 1994

As part of this approach, bell hooks challenged assumptions within second-wave feminism (~1960s – 1980s) that focused on patriarchy as isolated from, or as a foundation for, other forms of oppression. In doing so, she helped create space to explore the challenges of navigating power structures that are relational depending on where we are each located within the dynamic matrix of class, race, and gender.

Imagine living in a world where we can all be who we are, a world of peace and possibility. Feminist revolution alone will not create such a world; we need to end racism, class elitism, imperialism. – Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center , 2000

This approach was influential, with many of the ideas she articulated further developed by those examining, and agitating against, interdependent oppressive structures – debates that paved the way for intersectional feminism . For instance, bell hooks frequently detailed examples of overlapping identities uniquely impacted by multiple systems of oppression in ways that resemble the concept of intersectionality as articulated by Kimberlé Crenshaw .

Meanwhile, bell hooks also drew attention to the historical contingencies of instances of oppressive structures in specific local situations. This approach highlights our collective responsibility for challenging the interconnected structures of power these local instances each perpetuate. Building on bell hooks ideas offers avenues for accepting this responsibility and helping to build new pathways forward.

For examples of bell hooks writings that explore these interconnected structures of power, see:

- Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism , 1981 (2nd edition, 2015 )

- Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center , 1984 (2nd edition, 2000 ; 3rd edition, 2014 )

- Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black , 1989 (2nd edition, 2015 )

- Where We Stand: Class Matters , 2000

- Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice , 2013

For additional reflections on this aspect of bell hooks’ contributions, see:

- How Do You Practice Intersectionalism? An Interview with bell hooks , an interview by Randy Lowens, 2009; re-published in 2019 for Black Rose – Anarchist Federation

- How bell hooks Paved the Way for Intersectional Feminism , article for them by Elyssa Goodman, 2019

Practising love, as a verb, is a pathway to justice

bell hooks also helped to articulate the notion of love as a verb — a concept that shifts attention away from love as an abstract sentiment and onto the concrete manifestation of will demonstrated by intentional actions (such as care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust).

For bell hooks, love is an act of a transformative labour that offers an important pathway for communities surviving and challenging the imperialist-white-supremacist-capitalist-heteropatriarchy systems of oppression.

Acknowledging the truth of our reality, both individual and collective, is a necessary stage for personal and political growth. This is usually the most painful stage in the process of learning to love. – Love as the Practice of Freedom , in Outlaw Culture , 1994

This approach presents love as an act of communion with the world rather than between individuals alone. Drawing inspiration from Martin Luther King and others, bell hooks rejected the comodification of love as the passive indulgences of isolated romances.

To love well is the task in all meaningful relationships, not just romantic bonds. – All About Love: New Visions , 1999

Building on this, bell hooks helped to articulate how the work of cultivating love can be transformative for both individuals and communities. With this insistent theorising of love, bell hooks helped resist the dismissal of love as ‘too soft’ a topic for serious scholars – opening up space to examine the central role of love in almost every political question.

bell hooks exploration of the transformative power of love for communities has been particularly influential within social justice movements. For instance, her ideas are frequently referenced within activist resource lists, such as in efforts to develop transformative justice practices and community-led design .

For examples of bell hooks explorations of the concept of love as a verb, see:

- Sisters of the Yam 1993

- Love as the Practice of Freedom – in Outlaw Culture , 1994 ; (2nd edition, 2006 )

- Homemade Love – one of bell hooks’ children books, illustrated by Shane W Evans, 2017

- All About Love 2000

- Salvation: Black People and Love , 2001

For some additional reflections on bell hooks’ account of love as a pathway to justice, see:

- How bell hooks Theorised Love , article on Live Wire by Stuti Roy 2021

- Loving Ourselves Free: Radical Acceptance in bell hooks’ ‘All About Love: New Visions’ , article for Arts Help by Shakeelah Ismail, 2021

According to bell hooks, teaching should be an engaged practice that empowers critical thinking and enhances community connection.

Viewed in this way, teaching and learning become revolutionary acts that position classrooms as sites of mutual participation that cultivates joyful transformations (for students and teachers alike).

As a classroom community, our capacity to generate excitement is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence. – Teaching to Transgress , 1994

While initially focusing on tertiary education, bell hooks’ explorations of the activist potential of teaching practices extended to all educational activities – not just those occurring within educational institutions, but also teaching/learning within our communities more broadly. Combined with her ideas on love as a pathway to justice, this view positions teaching/learning an important way of contributing to our collective liberation from intersecting oppressive systems.

Along with others, such as Paolo Freire, Frantz Fanon, and Audre Lorde, bell hooks’ ideas about the transformative potential of engaged teaching helped to establish the field of radical pedagogy – which, in turn, contributed to respectfully engaged teaching practices, variously known as participatory teaching, active learning, progressive education , etc.

Education as the practice of freedom affirms healthy self esteem in students as it promotes their capacity to be aware and live consciously. It teaches them to reflect and act in ways that further self-actualization, rather than conformity to the status quo. – Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope , 2003

The following books offer some of bell hook’s explorations into the details of how and why the practice of teaching can, and should , be treated as a form of activism.

- Theory as Liberatory Practice , 1991

- Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom , 1994

- Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope , 2003

- Teaching Critical Thinking , 2009

For some further reflections on bell hooks’ ideas about teaching, see:

- Teaching to Transgress Today: Theory and Practice In and Outside the Classroom – video recording of a lecture by Imani Perry, followed by a discussion with bell hooks, Karlyn Crowley, Zillah Eisenstein, and Shannon Winnubst, 2014

- To bell hooks & not being happy till we are all free , reflection by Folúkẹ́ Adébísí, 2021

Contextualising bell hooks’ contributions

- A list of bell hooks’ books, by Shippenburg University Library, 1981 – 2021

- The catalogue of bell hook’s 13 appearances on the C-SPAN network , 1995 – 2005

- IMBD – bell hooks , list of appearances and credits for documentaries, 1994 – 2017

- A play list of the 22 videos collected from bell hooks’ lectures and conversations at The New School, New York City , 2013 – 2015

- Nothing Never Happens: A Radical Pedagogy Podcast – bell hooks archive , 2017 – 2018

- List of article authored by bell hooks for the Buddhist publication Lion’s Roar , 1998 – 2021

- bell hooks – tagged writings in the adrianne maree brown’s blog , 2014-2021

- To Read bell hooks Was to Love Her , a Vulture Media Network reading list by Tao Leigh Goffe, 2021

- Guide to Source Material for Anti-Racist Activists and Thinkers – bell hooks , by Shippenburg University Library, 2021

- Black History Month Library

- Video recording of an interview for the release of All About Love: New Visions by John Seigenthaler, broadcast by Word on Words, 1990

- Tender Hooks — Author bell hooks wonders what’s so funny about peace, love, and understanding , interview by Lisa Jervis at Bitch Media, 2000; re-published in 2021 as Remembering bell hooks in Her Own Words

- A Conversation with bell hooks , video recording of the 2004-05 Danz Lecture Series by University of Washington. This talk focuses on concepts of ‘family values’, heterosexism, and the distinction between patriarchal masculinity and masculinity; talk includes bell hooks reading two of her children’s books and is followed by a question and answer session with the audience.

- Challenging Capitalism & Patriarchy , an interview with bell hooks by Third World Viewpoint, 2007

- bell hooks in dialogue with john a. powell , a video recording of the keynote event for the Othering & Belonging Conference, 2015

- Building a Community of Love: bell hooks and Thich Nhat Hanh , 2017

- Archive of bell hooks’ Papers , held at Berea College, including correspondence, writings, academic work, and video recordings

- Encyclopaedia of feminist icons: The Essential bell hooks , introductory article by Stephanie Newman published on the blog Writing on Glass

- Big Thinker: bell hooks , article for the Ethics Center by Kate Prendergast, 2019

- bell hooks speaks up , article in The Sandspur (Vol 112 Issue 17, pp.1-2) quoting bell hooks, by Heather Williams, 2013

- Critical Perspectives on Bell Hooks , collection of academic articles edited by George Yancy, and Maria del Guadalupe Davidson, 2009

- The Teaching Philosophy of Bell Hooks: The Classroom as a Site for Passionate Interrogation , academic text by K.O. Lanier, 2001

- Communities_Community building / engagement

- Critical thinking

- Gender studies

- Intersectionality

- Social justice

- Theory of change

- Women activists

- Author: Commons Volunteer Librarian , E. T. Smith

- Location: Australia / Wurundjeri Country

- Release Date: 2022

Contact a Commons librarian if you would like to connect with the author

- Arts & Creativity

- Campaign Strategy

- Coalition Building

- Communications & Media

- Digital Campaigning

- First Nations Resources

- Fundraising

- Justice, Diversity & Inclusion

- Lobbying & Advocacy

- Nonviolent Direct Action

- Research & Archiving

- Theories of Change

- Working in Groups

Pin It on Pinterest

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Who were some early feminist thinkers and activists?

- What is intersectional feminism?

- How have feminist politics changed the world?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Official Site of Bell hooks Books

- BlackPast.org - Biography of Bell Hooks

- BFI - Bell hooks on cinema: a remembrance

- Black History in America - Bell Hooks

- NPR - Trailblazing feminist author, critic and activist bell hooks has died at 69

- Academia - Bell Hooks and Feminism

bell hooks (born September 25, 1952, Hopkinsville , Kentucky , U.S.—died December 15, 2021, Berea , Kentucky) was an American scholar and activist whose work examined the connections between race, gender , and class. She often explored the varied perceptions of Black women and Black women writers and the development of feminist identities.

Watkins grew up in a segregated community of the American South. At age 19 she began writing what would become her first full-length book, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism , which was published in 1981. She studied English literature at Stanford University (B.A., 1973), the University of Wisconsin (M.A., 1976), and the University of California , Santa Cruz (Ph.D., 1983).

Hooks assumed her pseudonym, the name of her great-grandmother, to honour female legacies; she preferred to spell it in all lowercase letters to focus attention on her message rather than herself. She taught English and ethnic studies at the University of Southern California from the mid-1970s, African and Afro-American studies at Yale University during the ’80s, women’s studies at Oberlin College and English at the City College of New York during the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2004 she became a professor in residence at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky. The bell hooks Institute was founded at the college in 2014.

In the 1980s hooks established a support group for Black women called the Sisters of the Yam, which she later used as the title of a book, published in 1993, celebrating Black sisterhood. Her other writings included Feminist Theory from Margin to Center (1984), Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (1989), Black Looks: Race and Representation (1992), Killing Rage: Ending Racism (1995), Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies (1996), Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work (1999), Where We Stand: Class Matters (2000), Communion: The Female Search for Love (2002), and the companion books We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity (2003) and The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love (2004). Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice was published in 2012. She also wrote a number of autobiographical works, such as Bone Black: Memories of Girlhood (1996) and Wounds of Passion: A Writing Life (1997).

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Understanding Patriarchy

Audio with external links item preview.

Share or Embed This Item

Flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

7,943 Views

14 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by resonanceananarchistaudiodistro on December 17, 2016

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Volume 52 Issue 13

bell hooks: A voice of love, activism, and intersectionality

- by Victoria A. Brownworth, Special to the SGN

- Friday October 28, 2022

When bell hooks died on December 15, 2021, it was a gut punch. There was no time when her extraordinary writing and feminist and Lesbian theorizing was not part of the Queer community. There was no time when the community imagined that hooks' voice would not always be in the forefront of our collective consciousness on intersectionality and Queer theory and praxis. Intersectionality has become a political and cultural buzzword recently, yet few have read the intersectional essays of hooks or Kimberlé Crenshaw, who invented that concept and wrote (and continues to write) about it exhaustively and, as Audre Lorde would say, deliberately. Intersectionality describes and explores how race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, and class might intersect with one another and overlap. The extraordinary breadth of hooks' writing and the thematic structures of her books, essays, and poetry all build on each other. She wrote so much of love, so compellingly of emotional and romantic commitment and what it means, that it was stunning when hooks revealed she spent the last two decades of her life unpartnered and celibate. In an interview for Shondaland in 2017, hooks (who lowercased her name) told Abigail Bereola, "I don't have a partner. I've been celibate for 17 years. I would love to have a partner, but I don't think my life is less meaningful. I always tell people my life is a pie, and there's a slice of the pie that's missing, but there's so much pie left over — do I really want to spend my time looking at that empty piece and judging myself by that?" In that same interview, hooks delved deeply into one of her pivotal topics: self-love and what it means for women to love themselves and recognize that they are worthy of commitment and that they do not deserve violence or other oppressive acts in a relationship. As hooks told Essence magazine in another interview, "I think the revolution needs to be one of self-esteem, because I feel we are all assaulted on all sides... I think Black people need to take self-esteem seriously." In the era of white/MAGA/GOP grievance, the fear of losing the prioritization of whiteness and cis-het maleness has subsumed much of our political discourse, which makes hooks' work more crucial than ever and her recent death all the more painful a loss. Centering Black women Born Gloria Jean Watkins on September 25, 1952, hooks began using her maternal great-grandmother's name as her pen name in 1976. She lowercased her name to signify that she wanted people to focus on her books, not "who I am," as she explained in a talk at Rollins College in 2013. Over the four decades of her writing, hooks wrote continually about Black women, feminism, the oppressive nature of patriarchy, and how Black men had embraced that even as they decried white imperialism. In her 1981 feminist classic, "Ain't I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism," hooks deconstructed a panoply of issues from slavery to the devaluation of Black women and Black womanhood. She wrote declaratively that "no other group in America has so had their identity socialized out of existence as have Black women... When Black people are talked about, the focus tends to be on Black men; and when women are talked about, the focus tends to be on white women." She wrote, "A devaluation of Black womanhood occurred as a result of the sexual exploitation of Black women during slavery that has not altered in the course of hundreds of years." Later, in "Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work," hooks expanded that discourse, noting, "No Black woman writer in this culture can write 'too much.' Indeed, no woman writer can write 'too much' ... No woman has ever written enough." Prescient ideas and theories True to her advice, hooks was always writing more and building on her previous ideas and theories. There is no disengaging of historical and cultural events in her work. She sees everything through a prism of contexts that each impact each other — hence the violence of nationalism cannot be divorced from domestic violence. She could see these links so clearly and write about them with such clarity, precision, and accessibility, that the reader was left convinced and educated. In a 1995 conversation with digital activist and lyricist John Perry Barlow, hooks said, "I have been thinking about the notion of perfect love as being without fear, and what that means for us in a world that's becoming increasingly xenophobic, tortured by fundamentalism and nationalism." We are in that time now, where the MAGA GOP has combined fundamentalism and nationalism and added a soupçon of xenophobia. The prescience of hooks' readings of the zeitgeist and the moment was a critical aspect of her oeuvre as a writer and theorist. Queer-pas-gay This was true even of her own identity. Though many people referred to hooks as a Lesbian or Gay, she preferred Queer. In describing herself as "queer-pas-gay," hooks inserted the French word for not — pas — and said that she chose that term because being Queer is "not who you're having sex with but about being at odds with everything around it." In an event on May 6, 2014, titled, "a conversation with bell hooks," the then-scholar-in-residence at Eugene Lang College for Liberal Arts at the New School spoke at length about this issue. She said, "As the essence of queer, I think of Tim Dean's [the British queer theorist] work on being queer and queer not as being about who you're having sex with — that can be a dimension of it — but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it, and it has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live." Background The details of hooks' life helped build her perspective and her feminist and Queer theory. She was born and died in Kentucky and often wrote about living in Appalachia (a region often associated with whiteness), but she lived most of her adult life elsewhere. She had several degrees: a BA from Stanford University, an MA from the University of Wisconsin—Madison, and a PhD from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She also worked across the country as a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz; San Francisco State University; Yale; Oberlin College; and the City College of New York. Among the issues hooks wrote about in her books was the confluence of health, mental well-being, and racism. True to another of her sayings — "I will not have my life narrowed down. I will not bow down to somebody else's whim or to someone else's ignorance" — hooks published prolifically: over 30 books and dozens of chapters and essays in books by others. Her publications included the iconic Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984), All About Love: New Visions (2000), Feminism is for everybody: passionate politics (2000), We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity (2004), Soul Sister: Women, Friendship, and Fulfillment (2005), and Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice (2013). She also wrote several children's books, including Homemade Love (2002). In the last decade of her life, struggling with the renal disease that ultimately killed her, she moved back to Kentucky. On her return to her birthplace, hooks compared her journey to that of author Wendell Berry. "Our trajectories are very similar," hooks told PBS, "because he went out to California, New York, the places that I too went, and then felt that urge, that call to home, that it's time to come back." There are so many things to be said about hooks' life and work, so many visionary concepts she developed and nurtured and expanded upon. But at her core, she was always writing a paean to love. She wanted love to equilibrate the world, to mitigate violence, to assuage the pain of racism, misogyny, homophobia, classism. In Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations , hooks wrote, "The moment we choose to love, we begin to move against domination, against oppression. The moment we choose to love, we begin to move towards freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others." Victoria A. Brownworth is a Pulitzer Prize—nominated, award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Baltimore Sun, DAME, The Advocate, and Curve, among other publications. She is the Bay Area Reporter 's television columnist. She was among the OUT 100 and is the author and editor of more than 20 books, including the Lambda Award—winning Coming Out of Cancer: Writings from the Lesbian Cancer Epidemic, Ordinary Mayhem: A Novel , and Too Queer: Essays from a Radical Life. This article was originally published in the Philadelphia Gay News. Reprinted with permission through the SGN 's partnership with the National LGBT Media Association.

Homeplace (A Site of Resistance)

This essay, by bell hooks, was first published in 1990 in Y earning: Race, gender, and cultural politics . Boston, MA: South End Press. Chicago

Historically, African-American people believed that the construction of a home-place, however fragile and tenuous (the slave hut, the wooden shack), had a radical dimension, one’s homeplace was the one site where one could freely construct the issue of humanization, where one could resist. Black women resisted by making homes where all black people could strive to be subjects, not objects, where we could be affirmed in our minds and hearts despite poverty, hardship, and deprivation, where we could restore to ourselves the dignity denied us on the outside in the public world.

Related content

“Ironies of the saint” Malcolm X, black women, and the price of protection - Farah Griffin

We are not all like that: the monster bares its fangs.

Is intersectionality just another form of identity politics? - Feminist Fightback

Identity, politics, and anti-politics: a critical perspective

Here to stay, here to fight - Kenan Malik

Caribbean women and the black community.

- Our Mission

The Best of bell hooks: Life, Writings, Quotes, and Books

Renowned author, feminist theorist, and cultural critic bell hooks passed away on Dec. 15 at the age of 69. Read about her remarkable life and and work, alongside a selection of pieces by and conversations with hooks published in the pages of Lion’s Roar.

- Share on Facebook

- Email this Page

When we drop fear, we can draw nearer to people, we can draw nearer to the earth, we can draw nearer to all the heavenly creatures that surround us. —bell hooks

Writer, feminist theorist, and cultural critic bell hooks has played a vital role in twenty-first-century activism. Her expansive life’s work of writing and lecturing has explored the historical function of race and gender in America.

hooks’ writing is deeply personal and educational, drawing on her own painful experiences of racism and sexism in an effort to educate us on how to combat them. hooks also plays a part in the Buddhist community, drawing inspiration from Buddhist practice in her life and her work. Her conversations with a number of important Buddhist leaders have been published on Lion’s Roar , along with her reflections on spirituality, race, feminism, and life.

Read on to learn more about bell hooks’ life and work, and to read some favorite pieces by and conversations with her.

The life of bell hooks

Early life and education.

bell hooks was born Gloria Jean Watkins in the fall of 1952 in Hopkinsville, Kentucky to a family of seven children. As a child, she enjoyed writing poetry, and developed a reverence for nature in the Kentucky hills, a landscape she has called a place of “magic and possibility.” Growing up in the south during the 1950s, hooks began her education in racially segregated schools. When schools in the south became desegregated in the 1960s, hooks faced painful challenges among a predominantly white staff and student population. These would inspire and shape her life’s work fighting sexism and racism to come.

After graduating high school, hooks studied at Stanford University, receiving a B.A. in English in 1973. It was at Stanford, in her Women’s Studies classes, that hooks began to notice a significant absence of black women from feminist literature. She began the writing of her book Ain’t I A Woman during her English studies, and also worked as a telephone operator. In 1976, she earned her M.A. in English from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and later received her doctorate in literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1983.

Writing and Career

In 1976, hooks began teaching as an English professor and lecturer in Ethnic Studies at the University of Southern California. During this time, she published a book of poems, And There We Wept , under the pen name “bell hooks” — her great-grandmother’s name, and a woman who, hooks has said, was known for speaking her mind. hooks chose not to capitalize any letters in her first and last name to emphasize focus on her message, and not herself or her identity.

hooks went on to teach at several post-secondary institutions, and in 1981, published Ain’t I A Woman , which examined the history of black women’s involvement in feminism, focusing on the nature of black womanhood, the civil rights movement, and the historical impact of sexism towards Black women during slavery. Ain’t I A Woman went on to gain worldwide recognition as an important contribution to the feminist movement, and is still a popular work studied in many academic courses.

To date, hooks has published more than thirty books, including four children’s books, exploring topics of gender, race, class, spirituality, and their various intersections. In 2014, she founded the bell hooks Institute , in Berea, Kentucky, which celebrates and documents her life and work, and aims to “bring together academics with local community members to study, learn, and engage in critical dialogue.” Visitors to the Institute are able to explore artifacts, images, and manuscripts written and talked about in her work.

Today, hooks continues to write and lecture to an ever-growing audience. In recent years, she has undertaken three scholar-in-residences at The New School in New York City, where she has engaged in pubic dialogues with other influential figures such as Gloria Steinem and Laurie Anderson. Last year, hooks sat down with actress Emma Watson for an inspiring conversation on feminism for Paper Magazine .

bell hooks and Buddhism

bell hooks was exposed to Buddhism due to her love and exploration of Beat poetry — most notably Beat poets Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder. At the age of 18, she met Snyder, a Zen practitioner, who invited her to the Ring of Bone Zendo in Nevada City, California, for a May Day celebration. She has engaged in various forms of what she calls a “Buddhist Christian practice” ever since.

hooks speaks and writes of her spirituality often, and has met in conversation with many influential Buddhist teachers, including Thich Nhat Hanh , Pema Chödrön , and Sharon Salzberg . In a 2015 interview with The New York Times , philosopher George Yancy asked hooks “How are your Buddhist practices and your feminist practices mutually reinforcing?” She responded:

Well, I would have to say my Buddhist Christian practice challenges me, as does feminism. Buddhism continues to inspire me because there is such an emphasis on practice. What are you doing? Right livelihood, right action. We are back to that self-interrogation that is so crucial. It’s funny that you would link Buddhism and feminism, because I think one of the things that I’m grappling with at this stage of my life is how much of the core grounding in ethical-spiritual values has been the solid ground on which I stood. That ground is from both Buddhism and Christianity, and then feminism that helped me as a young woman to find and appreciate that ground…

Feminism does not ground me. It is the discipline that comes from spiritual practice that is the foundation of my life. If we talk about what a disciplined writer I have been and hope to continue to be, that discipline starts with a spiritual practice. It’s just every day, every day, every day.

bell hooks in Conversation

Strike! Rise! Dance! – bell hooks & Eve Ensler

“Where does the trust come between dominator and dominated? Between those who have privilege and those who don’t have privilege? Trust is part of what humanizes the dehumanizing relationship, because trust grows and takes place in the context of mutuality. How do we get that when we have profound differences and separations?”

Eve Ensler and bell hooks discuss fighting domination and finding love.

Building a Community of Love: bell hooks and Thich Nhat Hanh

“In our own Buddhist sangha, community is the core of everything. The sangha is a community where there should be harmony and peace and understanding. That is something created by our daily life together. If love is there in the community, if we’ve been nourished by the harmony in the community, then we will never move away from love.”

bell hooks meets with Thich Nhat Hanh to ask him the question “How do we build a community of love?”

Pema Chödrön & bell hooks on cultivating openness when life falls apart

“The source of all wakefulness, the source of all kindness and compassion, the source of all wisdom, is in each second of time. Anything that has us looking ahead is missing the point.”

In this conversation from 1997, bell hooks talks to Pema Chödrön about how to open your heart to life’s most difficult challenges.

“There’s No Place to Go But Up” — bell hooks and Maya Angelou in conversation

“In my work I constantly say, this is how I fell and this is how I was able to rise. It may be important that you fall. Life is not over. Just don’t let defeat defeat you. See where you are, and then forgive yourself, and get up.”

A classic 1998 conversation between Maya Angelou and bell hooks, moderated by Lion’s Roar editor-in-chief Melvin McLeod.

bell hooks on Sex, Love, and Feminism

Toward a worldwide culture of love.

“Imagine all that would change for the better if every community in our nation had a center (a sangha) that would focus on the practice of love, of loving-kindness.”

The practice of love, says bell hooks, is the most powerful antidote to the politics of domination. She traces her thirty-year meditation on love, power, and Buddhism, and concludes it is only love that transforms our personal relationships and heals the wounds of oppression.

Ain’t She Still a Woman?

“It is easier for mainstream society to support the idea of benevolent black male domination in family life than to support the cultural revolutions that would ensure an end to race, gender and class exploitation.”

Increasingly, patriarchy is offered as the solution to the crisis black people face. Black women face a culture where practically everyone wants us to stay in our place.

When Men Were Men

“On one hand it’s amazing how much sexist thinking has been challenged and has changed. And it’s equally troubling that with all these revolutions in thought and action, patriarchal thinking remains intact.”

The message is, says bell hooks, that it’s fine for women to stray from sexist roles and play around with life on the other side, as long as we come back to our senses and stay happily-ever-after in our place.

Penis Passion

“When we finally gave ourselves permission to say whatever we wanted to say about the male body—about male sexuality—we were either silent or merely echoed narratives that were already in place.

bell hooks argues that our erotic lives are enhanced when men and women can celebrate the penis in ways that don’t uphold macho stereotypes.

bell hooks on Life and Faith

Voices and visions.

“When the spirit moves into writing, shaping its direction, that is a moment of pure mystery. It is a visitation of the sacred that I cannot call forth at will.”

bell hooks on the mystery of what calls her to write.

A Beacon of Light: bell hooks on Thich Nhat Hanh

“When I think of Thay now, I am amazed by his awesome gentleness of spirit. Through the years, it’s always been clear that he’s a teacher of tremendous integrity; there has been constant congruence between what he thinks, says, and does.”

The leading cultural critic and thinker bell hooks shares what Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh means to people of color.

When the Spirit Moves You

““Everywhere I turned in nature I could see and feel the mystery — the wonder of that which could not be accounted for by human reason.”

bell hooks shares her experiences of encountering the divine in nature and the written word.

Design: A Happening Life

“When life is happening, design has meaning, and every design we encounter strengthens our recognition of the value of being alive, of being able to experience joy and peace.”

bell hooks Quotes

Living simply makes loving simple..

There is no change without contemplation. The whole image of Buddha under the Bodhi tree says here is an action taking place that may not appear to be a meaningful action.

A generous heart is always open, always ready to receive our going and coming. in the midst of such love we need never fear abandonment. this is the most precious gift true love offers – the experience of knowing we always belong., it’s in the act of having to do things that you don’t want to that you learn something about moving past the self. past the ego., books by bell hooks, in the temple of love: the female buddha.

bad baby bell books In the Temple of Love is a collection of poetry by bell hooks. hooks draws on Buddhist themes of compassion, and puts a particular focus on the female bodhisttva, Tara on the 30 poems in this collection.

Belonging: A Culture of Place

“What does it mean to call a place home? How do we create community? When can we say that we truly belong?” asks bell hooks in Belonging . This book follows hooks’ life journey, and what she learned moving from place to place, from country to city, and finally landing back home in Kentucky. hooks explores the “geography of the heart,” touching on issues of race, gender, class, and the roles they play in our sense of community and belonging. hooks takes the reader back to her childhood in the Kentucky hills, where she first developed a deep love of nature, and shows the important role geography can play in developing our spiritual connections and worldviews.

All About Love: New Visions

Harper Perennial

In All About Love , hooks draws from personal experience, and explores the concept and meaning of love through a psychological and philosophical view. She looks closely at the difference between love as a noun, and a verb, examining the flawed idea of love society has created. Drawing on her own childhood and life’s experience, as well as words from influential figures throughout history, hooks investigates the question “What is love?” She unpacks the meaning of love in modern American life, urging us to let go of our obsessions with power and domination in order to truly awaken to love.

Salvation: Black People and Love

Here, hooks looks at love in African American communities, urging that we see love as a force for change. She looks at love through both a religious and social lens, again drawing on personal experience, and reflecting on the messages on love displayed in literature, film, and music. hooks also explores cultivating self-love as an African American woman as well as learning to love black masculinity, and embracing heterosexual love. When it comes to seeking justice, and healing historical and modern wounds in the world, and African American communities, “Love,” hooks concludes, “is our hope and salvation.”

The Will to Change: Men, masculinity, and love

In The Will to Change , bell hooks explores men’s most intimate questions about love, exploring the skewed way patriarchal society has taught men to know love, and know themselves. Though well-known for her feminist thinking, hooks works to include men in the discussion, as she believes men must be involved in feminist resistance. The Will to Change offers a feminist focus on men, doing away with radical feminist labeling of “all men as oppressors and all women as victims.” Many men, says hooks, are afraid to change, and have not been taught how to be in touch with their own feelings — The Will to Change offers a deeply intelligent roadmap to doing just that.

Lion’s Roar

Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance

Eating the other: desire and resistance lyrics.

This is theory’s acute dilemma: that desire expresses itself most fully where only those absorbed in its delights and torments are present, that it triumphs most completely over other human preoccupations in places sheltered from view. Thus it is paradoxically in hiding that the secrets of desire come to light, that hegemonic impositions and their reversals, evasions, and subversions are at their most honest and active, and that the identities and disjunctures between felt passion and established culture place themselves on most vivid display.

– Joan Cocks, The Oppositional Imagination Within current debates about race and difference, mass culture is the contemporary location that both publicly declares and perpetuates the idea that there is pleasure to be found in the acknowledgment and enjoyment of racial difference. The commodification of Otherness has been so successful because it is offered as a new delight, more intense, more satisfying than normal ways of doing and feeling. Within commodity culture , ethnicity becomes spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture. Cultural taboos around sexuality and desire are transgressed and made explicit as the media bombards folks with a message of difference no longer based on the white supremacist assumption that “blondes have more fun.” The “real fun” is to be had by bringing to the surface all those “nasty” unconscious fantasies and longings about contact with the Other embedded in the secret (not so secret) deep structure of white supremacy. In many ways it is a contemporary revival of interest in the “primitive,” with a distinctly postmodern slant. As Marianna Torgovnick argues in Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives :

What is clear now is that the West’s fascination with the primitive has to do with its own crises in identity, with its own need to clearly demarcate subject and object even while flirting with other ways of experiencing the universe.

Certainly from the standpoint of white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, the hope is that desires for the “primitive” or fantasies about the Other can be continually exploited, and that such exploitation will occur in a manner that reinscribes and maintains the status quo. Whether or not desire for contact with the Other, for connection rooted in the longing for pleasure, can act as a critical intervention challenging and subverting racist domination, inviting and enabling critical resistance, is an unrealized political possibility. Exploring how desire for the Other is expressed, manipulated, and transformed by encounters with difference and the different is a critical terrain that can indicate whether these potentially revolutionary longings are ever fulfilled. Contemporary working-class British slang playfully converges the discourse of desire, sexuality, and the Other, evoking the phrase getting “a bit of the Other” as a way to speak about sexual encounter. Fucking is the Other. Displacing the notion of Otherness from race, ethnicity, skin-color, the body emerges as a site of contestation where sexuality is the metaphoric Other that threatens to take over, consume, transform via the experience of pleasure. Desired and sought after, sexual pleasure alters the consenting subject, deconstructing notions of will, control, coercive domination. Commodity culture in the United States exploits conventional thinking about race, gender, and sexual desire by “working” both the idea that racial difference marks one as Other and the assumption that sexual agency expressed within the context of racialized sexual encounter is a conversion experience that alters one’s place and participation in contemporary cultural politics. The seductive promise of this encounter is that it will counter the terrorizing force of the status quo that makes identity fixed, static, a condition of containment and death . And that it is this willingness to transgress racial boundaries within the realm of the sexual that eradicates the fear that one must always conform to the norm to remain “safe.” Difference can seduce precisely because the mainstream imposition of sameness is a provocation that terrorizes. And as Jean Baudrillard suggests in Fatal Strategies :

Provocation – unlike seduction, which allows things to come into play and appear in secret, dual and ambiguous – does not leave you free to be; it calls on you to reveal yourself as you are. It is always blackmail by identity (and thus a symbolic murder, since you are never that, except precisely by being condemned to it).