- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Eco-idealism and staggering wealth meet in 'Birnam Wood'

John Powers

Ever since Ursula K. Le Guin and Edward Abbey lit the fuse back in the 1970s, there's been an ever-growing explosion of political eco-fiction. From Octavia Butler and Richard Powers to Amitav Ghosh and Margaret Atwood , novelists have gotten more and more fascinated with those who fight to save the environment.

One such group occupies the center of Birnam Wood , the whooshingly enjoyable new novel by Eleanor Catton , a New Zealander whose previous book, The Luminaries , made her, at 28, still the youngest person ever to win the Booker Prize. Where that 2013 novel was a wild-and-woolly beast, Birnam Wood — its title comes from Macbeth — is shapelier and more conventional. Filled with utopian hopes, personal betrayals, accidental deaths and profoundly unaccidental murders, this New Zealand-set book is a witty literary thriller about the collision between eco-idealism and staggering wealth.

The story begins by introducing three 20-something members of Birnam Wood, a guerrilla collective that seeks to fight capitalism and ecological devastation by, legally or not, growing things on unplanted land, public and private. There's Mira, the group's willful and charismatic founder. There's her burnt-out sidekick, Shelley, who does the grunt work and secretly wants to quit the group. And then there's Tony, the most radical thinker of the bunch who has returned to the group after several years abroad. He has romantic hopes for himself and Mira — hopes that Shelley quietly hopes to sink.

Mira hears about an unoccupied farm owned by Sir Owen Darvish and his wife Jill, who embody the solidity and complacency of well-off Kiwis. Mira thinks it perfect for a Birnam Wood project. But when she drives there from Christchurch, she discovers that it's been bought by Robert Lemoine, an elusive American billionaire/drone manufacturer who says he plans to build a survivalist bunker. Attracted to Mira, Lemoine offers to help finance Birnam Wood. Because her group badly needs money, she's interested. But will a rich benefactor's money help the group spread its message — or corrupt it?

The Two-Way

Book news: eleanor catton is the youngest-ever booker winner.

While Catton has sympathy for the grand idealism of the Birnam Wood collective, she also sees its fault lines. Indeed, the book's at its best taking us inside the characters' heads to lay bare the illusions, desires and petty motivations that often work against their dreams. For instance, Mira emerges as something of a modern-day version of Jane Austen 's Emma — Catton actually scripted a 2020 film adaptation of that novel. Mira's sense of political righteousness blinds her to her own motivations. The disaffected Shelley accuses her of "rebelling for the sake of it, like she had always done, acting as though the rules that bound the little people were just too tiresome and ordinary to apply to her."

Working in the tradition of the 19th-century novel — one hears echoes of George Eliot as well as Austen — Catton likes to confront her characters with choices and then lay bare the consequences, often unintended, of what they've chosen. There's a great, lacerating scene in which Tony, a world-class mansplainer, falls out of favor with the group by attacking identity politics and intersectionality. Because of this split, he will wind up spying on Lemoine — a move that sends the plot caroming in a wild new direction.

You see, while our heroes in the collective are muddling their way through ordinary human issues, they're faced with a villain from a 21st-century thriller. Lemoine isn't merely an amoral billionaire with all the compassion of one of his drones. He's a high-tech bad guy, complete with NSA-level spyware and mercenaries to do his bidding. Too bad to be true, he's so skillful at wielding his malignancy that, in spite of herself, Catton seems to hold him in a kind of awe.

Normally, it would be an artistic flaw that realistic characters like Mira, Shelley, Tony and the Darvishes must confront such a comic-book baddie, and I guess it is here: What starts off looking like a novel about character winds up in a climax out of a genre novel. Yet the story plays like gangbusters: I devoured all 400-plus pages in two days.

And in showing the collective's encounter with Lemoine, Catton taps into a feeling very much of our moment. We live at a time when many environmentalists feel helpless next to mega-rich forces who seem able to despoil the planet as they wish and to avoid any governmental attempts to check them. In Birnam Wood , we see the consequences of this gap in power, and the results are not pretty.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Eleanor Catton Wants Plot to Matter Again

Toward the end of “Birnam Wood” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), the latest novel from the New Zealand writer Eleanor Catton, Rosie Demarney, an otherwise minor character, gets a moment in the spotlight. She has been presented with a series of facts that seem to add up to a humiliating conclusion: the guy she likes has blown her off to pursue an old flame. Her fears are only confirmed by the embarrassed gaze of her crush’s sister. At home, clinging to her self-respect by a thread, Rosie firmly tells herself that she “was not going to play the role that he had cast her in; she was not going to spend the evening in her sweatpants, getting drunk and stalking him pathetically online.” A beat, a line break, and then the inevitable: “But hell. Nobody was watching.”

By now, if readers of “Birnam Wood” have learned one thing, it’s that someone is always watching. Whether people are being spied on by the modern technologies of surveillance (Google, G.P.S., cell phones, drones, social media) or by the more ancient techniques of intimacy (marriage, friendship, family, gossip), they are never afforded the luxury of a purely private action, or of avoiding the roles that others have written for them.

“Birnam Wood” opens with a seemingly impersonal catastrophe: a landslide in New Zealand kills five people. From this disaster a complex and often shocking sequence of events unfolds. The Darvishes, the owners of a large farm near the accident, withdraw it from sale; this withdrawal comes to the attention of Mira Bunting, “aged twenty-nine, a horticulturalist by training, and the founder of an activist collective known among its members as Birnam Wood.” Mira had previously inquired about the listing under a false identity, and she decides to visit: Birnam Wood illegally plants gardens on unused land, and the farm seems an ideal target for expansion. While trespassing on the grounds, she meets a curt American stranger who knows too much about her, including her name. He is Robert Lemoine, the billionaire co-founder of Autonomo, a drone manufacturer.

He is also, as we quickly learn, though Mira does not, responsible for the landslide. It doesn’t trouble him much. “Five dead, in the scheme of things, was basically no dead at all,” he thinks. Lemoine is in New Zealand pretending to build a covert apocalypse bunker; to this end, he is purchasing the Darvish farm under conditions of total secrecy, so secret that the estate must seem not to be for sale at all. But his actual aims are much darker: Korowai, the national park that sits beside the farm, possesses rare-earth minerals, which if extracted will make Lemoine “the richest person who had ever lived.” In Mira, Lemoine sees a kindred spirit, but also a dupe. He can use Birnam Wood as another smoke screen, a way to launder his presence through a local, eco-friendly organization. He offers Mira access to the farm and a hundred thousand dollars, suspecting, correctly, that she’ll find both the financial security and his shadowy mystique irresistible.

Discover notable new fiction and nonfiction.

Much like the moment in pool when the cue ball breaks up the carefully assembled triangle, this encounter between Mira and Lemoine ends up affecting every other character in the book, even those who have no reason to know one another. The choices they make, to use and to be used, reverberate in ways you might expect only if the image of the five crushed landslide victims lingers as you read. All of the book’s major players get a chance to turn the tide of events in their favor. Shelley Noakes, Mira’s best friend and roommate, is stealthily seeking a way out of the collective, tired of playing the steady foil to her more volatile friend. The Darvishes—Sir Owen and his wife, Lady Darvish—view Lemoine’s incredible wealth with a mixture of disgust, awe, and desire, even as they conduct business with him. And, finally, there’s Tony Gallo, Rosie’s love interest, Mira’s ex- something , and a former member of Birnam Wood, who, in a paroxysm of barely sublimated sexual jealousy, has decided to write an exposé of Lemoine, and in so doing stumbles upon Lemoine’s mining operation.

All of these people think that, with a little luck, they can manipulate another party to their advantage—even when they know that the others think the same of them, even when they are plotting betrayals on the fly, even when some of their plans are immediate and abject failures. (When Shelley first encounters Tony, she thinks that he presents an easy way to end her friendship with Mira: she will simply seduce him. She does not succeed.) Like Rosie, they have no intention of merely playing a role that somebody else wrote for them. And, like Rosie, they end up doing it anyway.

We do not live in the golden age of plot, at least where literary fiction is concerned. Outside of what we might call high-genre books—the thrillers of Ruth Rendell, say, or the crime novels of Tana French—it’s rare for a literary novel to take its plot seriously. Instead, contemporary literary fiction largely concerns itself with other things: moods, problems, situations. Few people would dream of writing a novel without characters, but a novel without a plot is practically normal. When you speak of what a novel is about, you speak thematically—it’s about surveillance, or displacement, or heterosexuality, or something along these lines.

In a recent interview, Catton commented, somewhat blandly, that “the moral development of people in plotted novels where people make choices is fascinating and important. I’d like to see more books like that.” Her interest in plot as something that arises from human choice, and not just from the context in which those choices take place, means that her own plots take a sideways approach. Just as we are constantly summing up books as types, the characters in “Birnam Wood” are constantly summing up one another, often incorrectly. When Shelley tries to seduce Tony—who, after a sojourn in Mexico, had completely forgotten that she existed—he is overwhelmed by their similarities, “astonished that he could ever have forgotten someone so thoroughly simpatico as Shelley Noakes.” Catton adds, in a rare direct address to the audience:

It never crossed his mind that since she had not forgotten him , the personality that she revealed to him might very easily have been customised, the opinions tailored, the résumé adapted, to suit what she remembered of his interests and his taste; never dreaming that she might be flirting with him, he reflected only that there was something appealingly familiar in her candid warmth and air of frank and ready capability.

One of Catton’s favorite moves is to conclude a scene from one character’s perspective only to start the next scene from the perspective of an adjacent character—someone whom the first character got slightly wrong. Shelley’s frantic musing about how to confess to Mira her desire to leave Birnam Wood is undercut by our realization that Mira has divined this desire weeks earlier. Mira’s perception of their relationship is undercut when, worried that Shelley has already left, she gets out her phone to check a “location tracker app that they had both installed . . . and never used.” But Shelley, we happen to know, uses the app to keep tabs on Mira all the time. They share an understanding of their friendship—that Mira is the top dog and Shelley is the sidekick, and that Shelley is “smothered” by this dynamic—that may not be true at all, or not true in the way they think.

Unlike Donna Tartt, who uses plot as straightforwardly as Dickens, or Sally Rooney, who has remade the marriage plot for a post-marriage era, Catton lets her plots and their attendant stakes emerge from a general situation. Like her characters, we begin without a sense of what matters, and are often pointed in the wrong direction. Initially, “Birnam Wood” seems to have no aspirations beyond an exploration of young, white, left-wing radicalism and its accompanying guilt—the kind of book that is “about” the anxiety of being a good person under capitalism and/or climate change. Mira fantasizes about brutal deaths in order to punish herself for feeling insufficiently bad about them. (“She compelled herself to imagine being crushed and suffocated, holding the thought in her mind’s eye for several seconds.”) Tony wants to argue about identity politics. When Mira allies herself with Lemoine, agreeing, over Tony’s protests, to let him finance Birnam Wood, we think we know how this will go: some hand-wringing, followed by some form of sexual congress, followed by a shrug over the problems of selling out.

We are wrong. “Birnam Wood” ’s biggest twist is not so much a particular event as the realization that this is a book in which everything that people choose to do matters, albeit not in ways they may have anticipated. Catton has a profound command of how perceptions lead to choice, and of how choice, for most of us, is an act of self-definition. Take Mira, whose determination not to be typecast lends her a stubbornness that’s easily mistaken for strength of character. Like some of her friends, Mira assumes that Lemoine’s interest in her is sexual: indeed, she spends time first imagining a scenario in which she’s propositioned and, ice-cold, turns him down, then an alternative, deflationary scenario in which she sleeps with him to prove that she’s not a prude. Her need to be unpredictable makes her easy to manipulate—it wouldn’t be unfair to say that she takes Lemoine’s money to show that she’s more than an idealist. But this choice is not, ultimately, about her. It invites violence, both symbolically—Birnam Wood now runs on “blood money,” as Tony puts it—and, as the book goes on, quite literally. The idea that her choices could affect something other than her internal narrative doesn’t occur to Mira, because it doesn’t often occur to anybody.

Meanwhile, “Birnam Wood” ’s true turns are all carefully set up, as long as you’re focussing on the right details. But none of the characters pay attention to the right things; they all think their snap impressions tell them what they need to know. Even Lemoine’s canny manipulation of others relies on the kind of lie that looks like the truth: a bunker is what people will expect him to be hiding, so that’s what he must be hiding. Discovering that they live in a world of consequence, with stakes bigger than self-image or self-respect, is as much of a shock to the characters as it is to us. Congratulations, Catton seems to say, on being just smart enough to play yourself.

Catton’s own choices are not without their critics. In a review of her second novel, the Booker Prize-winning “The Luminaries,” a critic for the Guardian wrote that the book was “a massive shaggy dog story; a great empty bag; an enormous, wicked, gleeful cheat.” But “The Luminaries” does tell a real story—a story of fated lovers—that it reveals only by inches. This romance, which appears to transcend the limits of space, is so heartfelt as to be, when put in plain view, almost embarrassing. For most of the book, it’s obscured, and we spend the first five or six hundred pages meeting the many characters whose various, complex, and sometimes tragic lives are, in the end, merely secondary. We discover what all of this is about at the same time they do.

Although “The Luminaries” stretches this form of emergent storytelling to the breaking point—it might not be a cheat, but several hundred pages is a long time to spend on misdirection—it’s clear that Catton is trying both to revive plot as a literary mode and to consider what a story line looks like in our real, unplotted life, in which things reveal themselves to have a shape only in retrospect. This project appears in a more subdued form in “The Rehearsal,” Catton’s début novel, which begins with a scandal: a student and a teacher have been discovered in a sexual affair. Everything in “The Rehearsal” takes place in a realm of high artifice, characterized by people who are so exact in their speech that you’re terrified to contemplate what they might not be saying. “A film of soured breast milk clutches at your daughter like a shroud,” a saxophone teacher informs the mother of a student. “Do you hear me, with your mouth like a thin scarlet thread and your deflated bosom and your stale mustard blouse?”

No saxophone teacher, or human being, for that matter, has ever spoken anything even approaching these words, but the arch, direct tone re-creates the unsettling world of adolescence, and the murky nature of adult expectation, more precisely than realism could. We expect the “story” of “The Rehearsal” to be about the fallout from the student-teacher affair. But this is really the backdrop for the novel’s true story, which is how the saxophone teacher tries—and fails—to use her students to reënact the story of her own frustrated love for another woman, with a different, happier ending. She fails because she cannot control the students’ choices any more than she could those of her onetime friend.

This willingness to let characters be mistaken—really, lastingly mistaken—is another quality that emerges from Catton’s privileging of human choice. When Tony uncovers proof of Lemoine’s rare-earth mining, he draws reasonable but slightly incorrect conclusions, assuming that Lemoine must be conspiring with Sir Darvish instead of deceiving him. The only people who would be in a position to correct him don’t—and so he carries on with this not false, but not true, version of events to the end. When Rosie Demarney, alone in her apartment, succumbs to an evening of Internet-stalking Tony, she stumbles across evidence that he could be in danger. In a Dickens novel, a character like Rosie might turn out to be pivotal; she’d connect the dots and save the day. Instead, she leaves the story for good. Would you, after all, go on a wild chase for someone you’d just been drunkenly Googling in your sweatpants? Someone you didn’t really know? Would it even matter if you tried?

One of the tragedies that plot brings to light is the degree to which our inner lives and intentions can simply come to nothing—unrealized despite our best efforts, misunderstood and fruitless, as the story we played our part in generating goes on without us. It is only by elevating human choice that we can see how often our choices don’t matter, after all. Or maybe it would be better to say that our choices matter only unpredictably. There’s no way of knowing what will really count until later, and by then it’s too late. Better choose.

In the course of “Birnam Wood,” Lemoine hacks phones, infiltrates e-mail accounts, operates drones with spy cameras, and employs a team of covert operatives. In his relentless surveillance, he is half critic, half author, and, in his own estimation, a kind of god. Like Catton, he tricks people into seeing what they expect to see.

But surveillance isn’t reading, much less writing; it’s data captured without interpretation. Instead of characters, we get types; instead of principles, revealed preferences. “A marketing algorithm doesn’t see you as a human being,” Tony says at one point, having lost his temper with another member of Birnam Wood:

It sees you purely as a matrix of categories: a person who’s female, and heterosexual . . . and white, and university-educated, and employed, who has these kinds of friends and shares these kinds of articles and posts these kinds of pictures and makes these kinds of searches . . . . Identity politics, intersectionality, whatever you call it—it’s the exact same thing.

It must be true that people often are what, on the surface, they seem to be; if it weren’t, algorithms wouldn’t have much use at all. There’s a certain pleasure in being a known type. At one point, Lemoine notes how “being a cliché can be very useful,” as it makes other people “think they’ve seen all there is to see.” Lady Darvish, musing on her marriage, thinks that her husband “took a certain pride in being so predictable . . . for the simple reason that he loved to see her demonstrate how well she understood him.”

Here, though, the implication is that we can read people without reducing them to a type. Owen Darvish loves to watch his wife “take that caricature and refine it, improving the likeness, adding depth and subtlety, shading it in.” Although not an optimistic book, “Birnam Wood” suggests that the greatest spook technology of all remains human love, with all its presumptive qualities, and that no external approximation will ever beat it at its game. There are things you just won’t know about other people, even if you intercept every text and every e-mail, unless you have loved them for a long time. There are gambles you are willing to take, acts of heroism and trust you are willing to commit to, because you know that you know them.

As for whether those acts matter, “Birnam Wood,” like all good books, doesn’t supply an answer. Reading it, I was drawn to the question of who represents Macbeth, the king who would be defeated only when “Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill / Shall come against him.” Macbeth is a character severed from choice. Prophecy, like a mystical surveillance system, keeps him blameless and safe: he is simply the man who is going to be king, and he does what he must do in order to preserve himself. In studying how much this or that person resembled him, I thought about ambition, deceit, paranoia, and unscrupulous ascension to power. I wondered who would be one of the witches, or, for that matter, Macduff. I wondered a lot of things—and yet it didn’t occur to me until the book’s final pages that the most significant attribute Macbeth possesses is something much more straightforward, at least where plot is concerned. Because Macbeth doesn’t understand what he’s told, because he lets prophecy make his choices for him, because he is at heart a cowardly man, when he’s faced with a certain human ingenuity, he loses. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

The hottest restaurant in France is an all-you-can-eat buffet .

How to die in good health .

Was Machiavelli misunderstood ?

A heat shield for the most important ice on Earth .

A major Black novelist made a remarkable début. Why did he disappear ?

Andy Warhol obsessively documented his life, but he also lied constantly, almost recreationally .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

The Spinoff

Books February 9, 2023

Birnam wood review: an astounding analysis of human psychology.

- Share Story

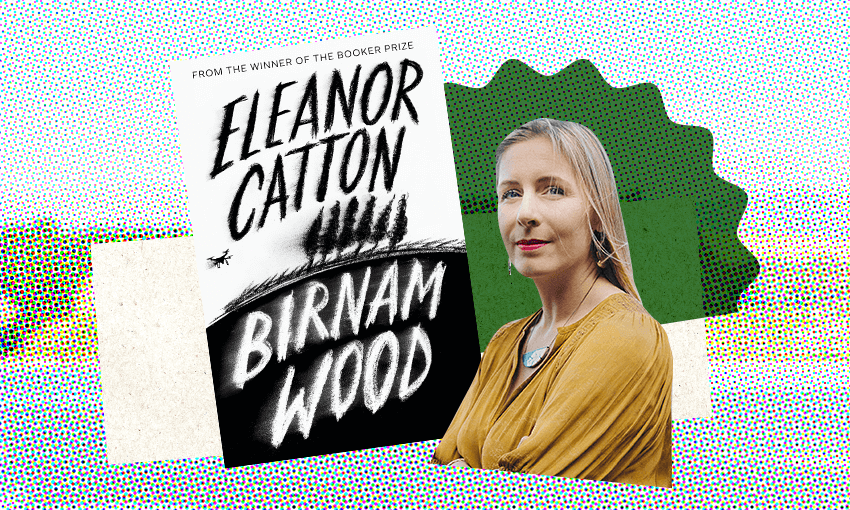

Books editor Claire Mabey reviews Birnam Wood, the long-awaited third novel from Booker Prize-winning Aotearoa writer Eleanor Catton.

Crouching quietly at the heart of Birnam Wood is the real-world plight of a critically endangered New Zealand bird, the fairy tern/tara-iti. At the time of writing this review there are fewer than 40 fairy tern/tara-iti left, and just nine breeding pairs. The survival of the species depends on the sanctity of its breeding grounds, beaches North of Auckland: Mangawhai, Waipu, Pakiri, North Kaipara Head. Hovering over those strips of sand, where the birds employ camouflage to avoid predators and threats, are anxious volunteers and DOC workers: desperate to see chicks survive into adulthood and for the tiny population to swell with each breeding season.

Just north of Mangawhai beach sits the private Tara Iti Golf Course and its adjacent luxury housing development. A 16-minute drive away is Mangawhai Village and chocolatiers Bennett’s , on whose website you can monitor the progress of fairy terns. I passed by the shop recently. It’s hard to miss: large, smart-looking, European in aesthetic, with enormous four-wheel drive car-creatures parked outside. Locals talk about the golf course and how the millionaires who built it also set up the Shorebirds Trust, ostensibly to boost the scrabble to protect the fairy terns, from whom the golf club took its name. A drone’s eye view may observe the golf course and associated properties as a nest: helicopters buzzing in and out, carrying flourishing animals to and fro, bedding in so close to the terns down there, hopelessly oblivious, in the sand. Between the mutterings of locals, the compromises and public-facing exchanges of money, land and grand gesture, the drama becomes complicated to the point of obfuscation: the fairy tern is there but not there.

Catton’s story burrows – enthrallingly, terrifyingly – into this precise entanglement. In her electrifying eco-thriller the New Zealand fairy tern becomes a conservation project that both connects and serves the interests of predatory billionaire Robert Lemoine and beknighted boomer, Thorndike local (via his wife, Jill) Owen Darvish. When their dealings are threatened by the ambitions of middle-class pseudo-activists Mira Bunting, Shelley Noakes and Tony Gallo, the cacophony of ego, ideals, sex, and politics becomes louder than the land upon which it all plays out. In short, Birnam Wood takes Shakespeare’s Macbeth for a tramp through New Zealand’s class and environmental battlegrounds and with those ingredients has produced a breathtaking analysis of human psychology in three acts – personal, political and public. Ultimately it asks whether we have, as a species at large, the survival instincts required to withstand an alarming new breed of technology-fuelled predation; whether we have the instincts to respond adequately to the warnings signs, environmental and political, that fight for our attention every day.

Catton’s battle ground is the fictional but familiar Korowai National Park and a slice of private farmland that abuts it, on the fringes of the town of Thorndike. Like every great drama, every player harbours a strong desire: Mira Bunting wants her stealthy, radical gardening collective, Birnam Wood, to have a shot at being solvent by extending their operation to growing food on the expansive piece of dormant Darvish farmland; Billionaire drone-making tech-CEO Lemoine wants the Darvish land so that he can camouflage his more sinister money-making intentions in the mineral-rich National Park; Sir Owen and Lady Jill Darvish want to keep their public profile sweet and money offered for the farm by Lemoine means a conservation profile to achieve it. And Tony Gallo, well Tony wants to be Nicky Hager: “Aloud he said, ‘Jesus Christ,’ and then again, ‘Jesus Christ ,’ and then, hushed in wonderment, he said, ‘I am going to be so fucking famous.’”

On the macro level, the loyalties and intentions of the players in Birnam Wood appear obvious, almost archetypal. However, one of the many exquisite thrills of this book is the way the narrator drops in, like a new breed of drone, to surveil with at times horrifying accuracy and precision the inner workings of every character and the contradictions therein. Catton is astounding in her ability to, on one level, turn our attentions to alarms, blaring loud as the witches warning in Macbeth; and on another level, investigate the complex, human preoccupations that blur and dull those glaring signposts like the buffets of a helicopter’s whirr.

Take, for example, this slice of Shelley Noakes, the administrative engine of the collective Birnam Wood, who burns quietly along Mira’s side, the picture of a middle-class millennial stuck between her tentative nature and her desire to transcend it: “For the first few months of their friendship, all that Shelley had known about Mira’s parents had been that they were former hippies who had each stood for their local constituency – her mother for the Green Party, her father for Labour – in subsequent elections, without success; and that Mira’s mother had a son from a previous relationship, Mira’s half-brother Rufus, who was the lead guitarist in a touring rock band and whom Mira’s father apparently adored. They sounded wonderfully enlightened, and the fact that Mira saw them only intermittently Shelley took as further proof of the psychological maturity that Mira found wanting in everybody else. She began to feel embarrassed that her own family convened each week for their parochial Sunday lunch, where invariably the conversation centred on, and was directed at, the dog – and she was even more embarrassed whenever Mira asked to tag along.”

Catton’s gift for interiority is mind-bending. There were many times reading the novel that I felt, with a mix of wonder and pure squirm, that my very outline was being traced with Catton’s subtle knife.

It is important to state at this point that Birnam Wood is working within a Pākehā framework: the characters are educated, middle-class Pākehā with progressive aspirations and the clunky frustrations born from that same thing. There is a particularly potent, soul-shrinking yet hysterically funny scene early in the novel where members of Birnam Wood gather for a meeting. Returning former member Tony Gallo makes himself unwelcome with unstoppered tirades on the many hypocrisies of the progressive left: “‘There’s something so joyless about the left these days,’ Tony continued, ‘so forbidding and self-denying. And policing. No one’s having any fun, we’re all just sitting around scolding each other for doing too much or not enough – and it’s like, what kind of vision for the future is that? Where’s the hope? Where’s the humanity? We’re all aspiring to be monks where we could be aspiring to be lovers.’” The unbridled irritation and mansplaining continues onward to cover polyamory and then eventually identity politics, where Tony says, “‘Everybody here is white. Am I wrong? Everybody here at this ‘hui’ – he put exaggerated quotes around the word – ‘is white and middle class, just like Amber, and just like me.’”

Later in the meeting, Mira (Tony’s love interest as well as lead protagonist) tells the collective that billionaire Robert Lemoine wants to invest in them. Mira does her best to justify the exchange in a familiarly awkward spill of doubt and hope: “There are, like twenty-five red flags. I get it. But again, for what it’s worth, I’ve done a bit of reading about Autonomo online, and it honestly doesn’t seem like they⸺”

It’s Tony of course who interjects with deep disgust and distrust, saying that a billionaire who makes surveillance drones and who is building a bolthole in New Zealand is “literally the opposite of everything we stand for.” The action of Birnam Wood, the real battle, begins here. With a departure from socialist values and the attempt to wed the devil (cold-hearted, calculating, psychopath predator, Lemoine). Tony’s instincts take him down the investigative path alone, tramping through the bush, gathering information. For all his rage, and accurate suspicions, he becomes like the fairy tern, a frail creature who tries to use camouflage to hide from Lemoine’s endlessly resourced weaponry: predatory drones and hired guns.

Camouflage is a crucial motif in the novel. It of course takes its cue from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the famous play about loyalty and guilt, and innocence and ruthless ambition. In the play, the witches tell Macbeth that he can only be killed when Great Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane. Macbeth, considering the movement of a forest impossible, rests easy. In the end, branches from trees in Birnam Wood are used by English soldiers to camouflage their advance, giving them the upper-hand enough to kill the King.

The inability to imagine the worst, to anticipate the twisted ends of human ambition to bend the planet to our will, is the downfall in both epic stories. It would be too much, here, to reveal who falls, and precisely why, in Catton’s tale of misapplied instinct and frail humanity, but I look forward to every reader’s breathless horror as they reach the final chapters in the riveting, racy third act.

Because Catton is an immersion artist. The deftness with which Catton’s third book – coming 10 years after The Luminaries won the Booker Prize – plunges us into the calamitous depths of our nature is freshly astonishing. When I began reading Birnam Wood I started to asterisk sentences that stood out to me as leggy, multi-parenthetic, joyrides of perfection. After the first few pages I realised that the book would soon become a constellation of blazing stars. Catton’s prose brings to mind Austen and Woolf and Mantel. She is among that echelon of literary mastery. Her sentences are the stuff of dreams: of ten-course degustations that give you the satisfaction of home cooking at its finest. In Catton’s hands the descent into character is so complete, so startlingly multi-dimensional, that the ride cannot help but be exhilarating and entirely consuming.

This, from Tony on page 157, is among one of my favourite examples:

“He imagined them spreading tarpaulins in the fields, weighting the middles and staking down the corners so the canvas wouldn’t fly away, perhaps setting out rainwater butts under drainpipes, and fashioning catchments in run-off ditches beside the road, and then piling back into Mira’s van, drenched and laughing, to drive back to the shearing shed where they’d set up their base of operations; he imagined them stringing a clothesline among the ancient wooden huts to hang their wet jackets up to dry, and he conjured in his mind a lofted space beyond the chutes where, in a happy hubbub of cross-pollinating chatter, they would all gather round to help prepare the evening meal, chopping vegetables for curry, and washing rice, and rolling out chapatis with an empty wine bottle dusted with flour, and someone would be strumming a guitar, or reading out Listener crossword clues, or narrating the gist of some recent article that had done the rounds online, and someone would be making an inventory of their progress to date, or delegating tasks for the coming day, or labelling seed sets for planting, and someone would be knitting, and someone would be poking irrigation holes in the bottoms of empty yogurt pots with a heated needle, and from time to time a snatch of melody from the guitar would cut through their conversation and they would all sing along in unison for a phrase or two – and then dissolve into embarrassed laughter, for at Birnam Wood such instances of unprompted and unaffected concord were always followed, Tony remembered, by a discomfiting, self-consciousness, for a moment everybody feeling, squeamishly, just a tiny bit like members of a cult.”

Catton has set her novel in 2017: the year that marked the beginning of Jacinda Ardern’s term as prime minister; when severe flooding affected the South Island’s West Coast; when wildfires tore through the Port Hills in Christchurch. There were a number of reported deaths that year too. Among them prominent men in business and philanthropy, honoured with groups of capital letters and titles from the Crown; and Paddles, Ardern’s cat. All of this to say that, looking back, the patchwork of events is familiar, even ordinary, despite the collection of disasters and the oddities of what we chose to mark down as important – on the Internet, in our media, sealed there for collective memory.

This, to me, is what Birnam Wood is getting at. The earth is moving around us all the time. We are approaching Dunsinane, inevitably: Forests are shifting, land is slipping, water is flooding. Predators are moving, camouflaged in plain sight. What is it that is tying so many of us in knots, rendering us incapable of doing anything about it? At the end of the novel there is a rip-roaring, last-gasp plea for attention. The question that remains is who will respond and what will be done? Is there a chance for the collective to move against the new Kings of this world? Or, as in the case of the fairy tern, does it feel uncomfortably like too little, too late?

Apparently, the Shorebirds Trust has invested $300,000 in the conservation of the fairy tern (the most recent figure I could find was from this NZ Geographic article , 2020). The amount required to become a member of the Tara Iti Golf Club is not disclosed, though membership is invitation only and is said to require six-figures. I’m dazzled by Catton’s brilliance. And terrified too. This is fiction that rubs very close to the bone.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $50, hardback) can be purchased from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland .

The Spinoff Review of Books is proudly brought to you by Unity Books and Creative New Zealand. Visit Unity Books online today.

Advertisement

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Eleanor Catton on ‘Birnam Wood’

The new zealand writer, who won the man booker prize in 2013 for her novel “the luminaries,” discusses her latest book..

- Share full article

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | How to Listen

Eleanor Catton’s new novel, “ Birnam Wood ,” is a rollicking eco-thriller that juggles a lot of heady themes with a big plot and a heedless sense of play — no surprise, really, from a writer who won Britain’s prestigious Man Booker Prize for her previous novel, “The Luminaries,” and promptly established herself as a leading light in New Zealand’s literary community.

On this week’s podcast, Catton tells the host Gilbert Cruz how that early success affected her writing life (not much) as well as her life outside of writing (her marriage made local headlines, for one thing). She also discusses her aims for the new book and grapples with the slippery nature of New Zealand’s national identity.

“You very often hear New Zealanders defining their country in the negative rather than in the positive,” she says. “If you ask somebody about New Zealand culture, they’ll begin by describing something overseas and then they’ll just say, Oh, well, we’re just not like that. … I think that that’s solidified over time into this kind of very odd sense of supremacy, actually. It’s born out of an inferiority complex, but like many inferiority complexes, it manifests as a superiority complex.”

A word of warning, for listeners who care about plot spoilers: Toward the end of their conversation, Catton and Cruz talk about the novel’s climactic scene and some of the questions it raises. So if you’re a reader who prefers to be taken by surprise, you may want to finish “Birnam Wood” before you finish this episode.

We would love to hear your thoughts about this episode, and about the Book Review’s podcast in general. You can send them to [email protected] .

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

The Best Fiction Books » Thrillers (Books)

Birnam wood: a novel, by eleanor catton & saskia maarleveld (narrator).

☆ Shortlisted for the 2023 Orwell Prize for Political Fiction

🏆 An AudioFile Best Mystery/Suspense Audiobook of 2023

Recommendations from our site

“One of the biggest books of the season must be Eleanor Catton’s hotly anticipated third novel Birnam Wood . Pitched (somewhat unexpectedly) as a psychological thriller, it follows the members of a guerilla gardening group as they take over an abandoned farm in cautious partnership with a paranoid American billionaire with plans to build his own survivalist bunker.” Read more...

The Notable Novels of Spring 2023

Cal Flyn , Five Books Editor

“Eleanor Catton won the Booker Prize for her novel, The Luminaries . This is very different. It’s also set in her native New Zealand, but it’s a kind of environmentalist thriller. It’s extremely witty, extremely pacey, and incredibly well crafted. It’s about the fight over a particular patch of threatened ground in rural New Zealand. A group of guerrilla gardeners wants to use it for their organic ecological project but it’s also in the sights of miners and developers. The clash between them is executed with incredible panache, wit, surprise and suspense.

This is a book which on its back cover has an endorsement from none other than Stephen King , which I think tells you about the narrative drive that Eleanor Catton achieves here. It’s enormously enjoyable and, of course, it raises all of these profound questions about who should control the land and how it can be protected from environmental degradation.”

Best Political Novels of 2023, recommended by Boyd Tonkin

Other books by Eleanor Catton and Saskia Maarleveld (narrator)

First lie wins by ashley elston & saskia maarleveld (narrator), our most recommended books, the talented mr ripley by patricia highsmith, eye of the needle by ken follett, fatherland by robert harris, the day of the jackal by frederick forsyth, the thirty-nine steps by john buchan, rebecca by daphne du maurier.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

A New Zealand Eco-Thriller Where No One Gets Off Scot-Free

Eleanor catton, the youngest-ever booker winner, confirms her promise with the taut, satirical birnam wood..

The Luminaries, Eleanor Catton’s breakthrough, was a clockwork marvel, a pastiche of the Victorian sensation novel set in the gold fields of 19 th -century New Zealand and elaborately patterned after the astrological configuration of the time—while at the same time a credible replication of the pleasure of reading Wilkie Collins. The book was dazzling enough to make her the youngest winner of the Booker Prize in 2013, and the fame it brought caused her quite a bit of grief at home, after she criticized New Zealand’s ruling class for being “neoliberal, profit-obsessed, very shallow, very money-hungry politicians.”

Birnam Wood , Catton’s long-awaited follow-up, is set in the present day and expands upon that concern for the fate of her nation. The novel is a tightly plotted thriller enriched with tartly satirical depictions of an assortment of elements that outsiders casually associate with New Zealand: natural splendor, earnestly decent white people carefully borrowing ideas from Māori culture, environmental threats, and creepy American tech billionaires setting up boltholes in which to ride out the apocalypse they’re doing nothing to prevent. The title comes from the name of a guerrilla gardening collective that reclaims unused land to grow food, which in turn is named after the Scottish forest that figures in the witches’ prophecy to Macbeth that he shall go unvanquished until its trees come to Dunsinane.

Birnam Wood

By Eleanor Catton. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Mira Bunting, the charismatic 29-year-old founder of Birnam Wood, learns of an abandoned plan to subdivide a former sheep farm near a national park on the South Island. A landslide has buried part of the main highway and scuttled the project; to Mira, this sounds like the perfect site to expand her illicit farming operation. It doesn’t hurt that the land’s boomer owner, Owen Darvish, deeply annoys her because of his prominent involvement with conservation projects. It irks her that “anyone of this man’s age, race, gender, wealth, and associated privilege should have used his power—allegedly—for good, should have built his business—allegedly—up from the ground, from nothing, and should possess—allegedly—the very kind of rural authenticity that she herself most envied and pursued.”

As the novel moves smoothly through a half-dozen points of view—Darvish himself is revealed to have only a cosmetic interest in environmentalism and is absurdly pleased to receive a knighthood for his work—Catton nevertheless reserves her sharpest darts for a certain flavor of lefty activism whose foibles are both peculiar to Mira’s generation and not. Anyone who’s belonged to a group like Birnam Wood will instantly recognize some familiar figures: the member who quietly does all the work (Mira’s best friend, Shelley), the guy who angrily expounds on the failures of the contemporary left to live up to the precepts of socialism (an aspiring journalist named Tony, with whom Mira had a one-night stand years ago), and the inevitable woman everyone has to tiptoe around because she’s a “walking list of grievances.” The latter two get into a big and painfully spot-on argument at the beginning of the novel. All he can do is lecture and all she can do is take offense.

This exchange (“Um, just so I’m clear … you’re saying that intersectionality is bullshit ?”) takes place at a “hui”—the Māori word for meeting—at which Mira announces that Robert Lemoine, an American billionaire in the process of buying the farmland from Darvish, has offered to invest handsomely in the collective. The money will be enough to let Birnam Wood “break good” and become a full-fledged, self-sustaining nonprofit. Yes, Lemoine made his fortune in drones and surveillance technology, but “not the military kind,” Mira assures the other members. Tony objects—“Mass surveillance is totalitarian and oppressive. The billionaire class undermines solidarity by its very existence”—but he has so alienated the rest of the collective that his points don’t register.

Birnam Wood is an enjoyably piquant blend of fictional modes. Early on, there’s plenty of Sally Rooney-esque dissections of the intricacies of millennial relationships. Shelley, who wants to leave Birnam Wood but can’t quite summon the nerve to do so outright, contemplates sleeping with Tony because she knows that this will force a break with Mira, who still carries a torch for him. When the novel swerves to Lemoine’s point of view, it plunges the reader into a thrillerish world of intrigue for its own sake as well as for profit. Lemoine’s persona is a series of poses designed to play to other people’s fondness for stereotypes and lull them into underestimating him. With every twist of the plot, he swiftly and ruthlessly recalculates his tactics to maximize his own advantage and minimize his liability. “Are you a psychopath?” Mira asks Lemoine outright when he catches her during her reconnaissance trip to the farm. “Now, how would a psychopath respond?” is his coy reply.

Is Lemoine a bit of a Bond villain? Well, yes. But in his manipulation of the other characters, his ability to arrange them like chessmen to act out the scenarios of his choosing, he’s also a lot like a novelist. Observing his endless, ingenious calculations is one of the many pleasures of Birnam Wood. He’s also not completely pragmatic. Lemoine’s interest in Mira is spurred not by her idealism but by her transgression—trespassing, using false identities to get the goods on possible farming sites, and other gambits that make her a “little criminal,” in his eyes. Inviting Mira and her posse of do-gooders to the farm may not further the smooth functioning of Lemoine’s covert operation, but it appeals to the billionaire’s imp of the perverse. It also sets the novel’s story in motion.

Almost all of the pieces of Birnam Wood fit together as intricately and operate as pleasingly as Lemoine’s stratagems, with the notable exception of the group’s name, which is never properly explained. Why would such an earnest lefty Kiwi group pick a moniker from a Shakespeare play? (Tentatively, Shelley suggests a Māori alternative.) Here, Catton tips her hand. She has a penchant for schema herself, and with Birnam Wood , as with The Luminaries , she began the project not with a plot but with a chart . Every character is, in his or her way, Macbeth; every character is susceptible to ambition in one way or another, and therefore temptable. Darvish has a provincial’s desire to impress the American big shot. Mira wants Birnam Wood to achieve “nothing less than radical, widespread, and lasting social change.” When Tony, an impressive bushwhacker, takes to the bush and discovers the secret behind Lemoine’s interest in the South Island, his first thought is “I am going to be so fucking famous.” Even the diabolical Lemoine falls afoul of his own delight in playing the puppet master.

Macbeth is a tragedy, which hints that Birnam Wood will not end as reassuringly as the typical thriller. If Catton has a weakness as a novelist—and she doesn’t have many—it’s that her fondness for comprehensive patterning is not very novelistic. In essence, the novel is about individuals, how they feel and think and change and in doing so shape the world they live in, even if they only do so in small ways. But Catton’s characters resemble the figures in Greek tragedy, people enmeshed in systems whose attempts to commandeer their own fates inevitably end in tears and blood. It may upset readers who were certain they knew what kind of resolution was coming, but that is surely Catton’s point. Hubris will always get you in the end.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton: A big, brash cerebral snapshot of the modern world

Catton blends literary and commercial fiction in her latest masterful display of storytelling and character set in new zealand.

How do you follow a novel that made you the youngest winner in the history of the Booker Prize? Answer: with another exceptional read. Eleanor Catton’s latest book, Birnam Wood, is literary fiction with the propulsive pace of a thriller, a masterful display of omniscient storytelling, a cautionary tale of friendship soured, a shrewd take on environmental activism and the global existentialist threat, and undoubtedly one of the books of the year.

Everything about Birnam Wood is taut and tightly wound, from the title and epigraph that reference Macbeth, to the carefully curated list of characters, to a plot that unfolds over a relatively short timeframe, to the chosen setting in an isolated region of New Zealand’s south island, the fictional Korowai Pass, where a landslide has closed the roads, meaning that “the town was now contained in all directions but one”. Catton takes such hallmarks of the suspense genre and makes them her own in a story that never flags in over 400 pages, buoyed along by the author’s gift for narrative tension and her fluid, elegant prose.

Birnam Wood opens with an establishing, panoramic shot of the region, like a classic 19th-century novel, before tapering to the perspective of Mira Bunting, head of the anarchist gardening collective Birnam Wood. After the landslide, Mira plans to occupy an abandoned farm – owned by wealthy local couple Sir Owen and Lady Darvish (another nod to Macbeth) – but unbeknown to her, an American billionaire, Robert Lemoine, has got there before her, making a bid for the land under the pretense of building a survivalist bunker to see out the apocalypse. What follows is a tense, thrilling story that puts a small cast of highly contemporary characters under extreme pressure to explosive results.

[ Eleanor Catton: a luminous new star in the literary constellation Opens in new window ]

The omniscient third perspective suits this type of narrative. Catton deploys the authorial voice with aplomb, allowing the reader to see more than the characters’ limited viewpoints, to appreciate their weaknesses, to anticipate how such traits might be exploited. It also leaves room for plenty of sharp comic asides. Birnam Wood is a tragedy, but like all good tragedies, it contains bitter flashes of humour.

‘I learned about Irish time. People arrive late and think they are on time’

Bishop Casey’s Buried Secrets review: ‘He had no fear of being caught’

Nightmare concerts: Nicki Minaj put on one of Ireland’s most disappointing gigs. Here are nine more disasters

13 ways to boost the health benefits of a holiday

Mira and her second-in-command, Shelley, have bonded over Shelley’s mother’s reticence about their work: “At Birnam Wood ‘Shelley’s mum’ had become a kind of shorthand for the many evils of the baby-boomer generation.” Elsewhere, returning traveller Tony gives a PhD-length summary of his backpacking adventures. Billionaire Robert thinks about replying “unsubscribe” to the long-winded emails of a colleague. A wonderful set piece around a homemade bowl of soup sees two equally correct, and equally annoying, factions of the collective get into an argument about identity politics. Throughout these brightly evocative scenes, Catton is busy setting up more twists, tightening the screws.

Tony, for all his self-mythologising, turns out to be a great foil to Robert’s machinations. Each of the main characters – Mira, Shelley, Tony, Robert, Lady Darvish – are intelligent, enterprising and physically strong, which raises the stakes considerably. There is the sense that anyone could win in the end. Unusually for a literary novel, the book is action-packed, which is to say full of compelling events and conflicts, but also in the literal sense of how the characters act, the choices they make when under pressure, the consequences of these choices at once surprising and fateful.

[ History Keeps Me Awake at Night: A voice-led debut about the trials of modern life Opens in new window ]

Catton is the author of The Luminaries, winner of the 2013 Man Booker Prize and a global bestseller. Her debut novel, The Rehearsal, won the Betty Trask Prize, was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award and the Dylan Thomas Prize, and longlisted for the Orange Prize. As a screenwriter, she has adapted The Luminaries for television, and Jane Austen’s Emma for feature film. Born in 1985 in Canada and raised in New Zealand, she now lives in Cambridge.

With each of her novels to date, Catton has been preternaturally good at finding the sweet spot between literary and commercial fiction, an heir to writers like Donna Tarrt and Jeffrey Eugenides. Her insight into character is similarly astute, the judgments swiftly rendered: “[Mira] preferred the company of men. Her favoured style of conversation was impassioned argument that bordered on seduction, and although it was distasteful, not to mention tactically unwise, to admit that one enjoyed flirtation, she never felt freer, or funnier, or more imaginatively potent than when she was the only woman in the room.”

Ultimately though, this is an unapologetically political novel, more concerned with the abuses of power of government and elite societies than the navel-gazing of any particular character. Catton has said that she wanted to explore the contemporary political moment without being partisan. She has more than achieved this with Birnam Wood, a big, brash cerebral novel of multiple perspectives, a snapshot of the modern world, to paraphrase Macbeth’s witches, where fair is foul and foul is fair.

Sarah Gilmartin

Sarah Gilmartin is a contributor to The Irish Times focusing on books and the wider arts

IN THIS SECTION

Fiction in translation: works from palestine, catalonia, france, germany and sweden, donald trump told nephew to let his disabled son die, book says, mother naked: dazzling work of speculative fiction set in 15th century, secrets and lies: memoirs that unlock ireland’s past, the coin by yasmin zaher: mad, brilliant novel about a palestinian woman in new york, co westmeath farmer ‘shocked’ when bronze age axe heads found on his land, look inside the most expensive house sold in dublin so far this year, ‘move it to the south side’: dubliners mortified by antics at capital’s transatlantic portal, ‘a gross betrayal’: taxi driver raymond shorten jailed for 17 years for rape of two young passengers, rip-off ireland how overseas tourists rate ireland on value for money, latest stories, olympic rugby sevens live updates: ireland face all blacks in final pool game, immigration is both essential and impossible, ireland just as vulnerable to security threats as neighbours despite neutrality, defence review concludes, sixth man convicted over murder of man in kerry graveyard, the ‘iron lady’ of venezuela threatens to unseat maduro.

Sign up to the Irish Times books newsletter for features, podcasts and more

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Information

- Cookie Settings

- Community Standards

StarTribune

Review: 'birnam wood,' by eleanor catton.

I'll start my review with the headline: Eleanor Catton's "Birnam Wood" is one of 2023's most sophisticated, stylish and searching literary works, a full-on triumph from a generational talent. Catton is best known for her Booker Prize-winning "The Luminaries," published a decade ago; at age 28 she was (and remains) the youngest laureate. Her new novel, titled after a ragtag team of ecological leftists, employs the thriller form to magnificent effect.

Set on New Zealand's rugged South Island before the pandemic, "Birnam Wood" follows Birnam Wood as they plant crops and flowers along highway medians and abandoned urban lots. Mira, their self-possessed, 20-something leader, pushes a rigid agenda, aided by her confidante Shelley, who sulks in the shadow of her friend.

After a landslide near the postcard-perfect town of Thorndike, abutting Kurowai, a national park, Mira scouts a former sheep station now owned by Owen Darvish, who has jetted off to London for a knighthood. While trespassing, Mira encounters a macho American billionaire, Robert Lemoine, who flies a private plane to and from Lord and Lady Darvish's airstrip. Mid-40s, he's deep into a secretive business deal with the couple. He visits their property frequently, for reasons that he's careful to hide.

Lemoine is the archetype of a sexy, sinister plutocrat. His swagger seduces Mira. In turn he's captivated by her assertiveness and guile: he offers her group fields and tools to farm. This strange-bedfellows partnership raises red flags for Tony, Mira's ex-boyfriend, who has just returned to New Zealand after a stint abroad. An aspiring journalist, Tony also stakes out the Darvish acreage, even slipping into Kurowai park, where he discovers a phalanx of drones and a creepy testing site. Something's amiss in the bush.

Till Birnam wood remove to Dunsinane / I cannot taint with fear. The author casts Lemoine as the egomaniacal, self-deluded Thane of Cawdor and Mira as Lady Macbeth, she of questionable ethics and Out-damned-spot fame.

Catton writes languid sentences that fold back on themselves amid a lift of conjunctions and prepositional phrases, much like Lemoine's cockpit skills: "Nothing in the world compared to the liquid thrill of piloting a craft through three axes of movement, feeling the vertical, the lateral and the longitudinal as divergent possibilities curving away from him through air that was tactile and elastic and textured with a warp and a woof."

Climate crisis, late-stage capitalism, and male predation: "Birnam Wood" traverses narrative territory similar to Stephen Markley's "The Deluge" and Rebecca Makkai's "I Have Some Questions for You."

But in its scope and execution it moves beyond these novels just as smoothly as Lemoine's plane glides upward. Catton deftly fleshes out her characters' back stories; as a child Lemoine taught himself chess, archvillain as embryo: "His goal had been to become so ambidextrous when it came to action and reaction, move and countermove, that he would reach the point where half the games he played were won by white, and half by black: only then, he'd told himself, could he really call himself a master." He can't control each piece on the board, though, and the author keeps us guessing until the startling crescendo.

I'll end my review with the headline: Eleanor Catton's "Birnam Wood" is one of this year's most sophisticated, stylish, and searching works, a full-on triumph from a once-in-a-generation talent.

Hamilton Cain reviews fiction and nonfiction for a range of venues, including the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. He lives in Brooklyn.

Birnam Wood By: Eleanor Catton. Publisher: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 432 pages, $28.

- Project 2025 platform proposal aims to allow mining in Boundary Waters watershed

- Blaine parents react to 'shockingly wicked' abuse case involving three infants at day care center

- Toddler bitten by pit bulls in Brooklyn Park not expected to survive, according to family

- Hope, limbo, despair: Mexican family living in Mpls. is deported after asylum bid denied

- Biden delivers solemn call to defend democracy as he lays out his reasons for quitting race

- A sneak peek at Yia Vang's dream restaurant Vinai

Scene Maker Q+A: Country stalwart Sherwin Linton shares stories of Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan

The olympics are coming to the capital of fashion. expect uniforms befitting a paris runway, publisher plans massive 'hillbilly elegy' reprints to meet demand for vp candidate jd vance's book, it's a college football player's paradise, where dreams and reality meet in new ea sports video game, saquon barkley wants to move on from 'hard knocks' giants life to fresh start with eagles.

- Southwest Airlines to abandon open seating and offer new upgrades 41 minutes ago

- Project 2025 platform proposal aims to allow mining in Boundary Waters watershed 7:37am

- Minnesota authors blaze trails with children's books that address gender • Books

- Big names Kate DiCamillo, Louise Erdrich, Edwidge Danticat and Alice Hoffman are Talking Volumes guests • Books

- Read these 8 books set in Minnesota exactly where they take place • Books

- New book looks back at 1982, when "E.T.," "Blade Runner" and "The Thing" revolutionized how we see movies. • Books

- 24 books you'll want to take to the cabin, the beach or your favorite chair this summer • Books

© 2024 StarTribune. All rights reserved.

A Biting Satire About the Idealistic Left

Eleanor Catton’s new novel, Birnam Wood , pokes at the pieties of those who want to change the world.

Ask me how much time and money I have devoted, in my adult life, to conscious efforts to be a good person, and I would struggle to quantify it. Of course, I would also struggle to tell you what “being good” means. My ideas seem to change constantly, which means the target shifts. Besides, the world I inhabit does not make goodness easy, for me or anyone else. I put clothes I no longer wear in giveaway bins run by a profoundly inefficient nonprofit ; I assiduously recycle despite reports that my plastic is likely “ headed to landfills, or worse ”; I sign up for shifts at a food bank, then cancel because I have to work. If I were giving away more money, or more of my time, my efforts would surely be wobblier or more questionable still.

Birnam Wood , the third novel by the New Zealand writer Eleanor Catton, picks up on the instability of trying to be good, a pursuit the book views quite bleakly. Loosely about the idealistic antics of a guerrilla gardening group, it has no hero but rather an ensemble of antiheroes whose foibles Catton uses to poke, quite hard, at the dreams and pieties of people who believe they can change the world. Such an impulse is a major shift from Catton’s Man Booker Prize–winning second novel, The Luminaries , an intricate, glowing love story set during New Zealand’s gold rush. Birnam Wood , in contrast, is dark in both its outlook and its omnipresent humor.

Catton is especially sharp in her portrayal of Mira Bunting, Birnam Wood’s charismatic founder. Day to day, the group plants legal gardens in donated yards and illegal ones on unmonitored land across New Zealand. Mira feels sure this project will someday generate “radical, widespread, and lasting social change” by showing people “how much fertile land was going begging, all around them, every day … and how arbitrary and absurdly prejudicial the entire concept of land ownership, when divorced from use or habitation, really was!” She is so confident, in fact, that when an American billionaire—who, to the reader, is plainly menacing—offers her a major donation and access to a large swath of land to cultivate, she barely blinks before making the executive decision that the group should accept.

Catton swiftly reveals Robert Lemoine, the billionaire in question, to be a James Bond–style bad guy, a 100-percent-evil evildoer who supports Birnam Wood only because he can use its garden to help conceal his scheme to illegally mine rare-earth minerals from a protected nature reserve next to land he has recently, secretly bought. Simply by linking Birnam Wood to him, Mira puts herself and the group in great danger. Catton draws Lemoine in great detail, but he is less a three-dimensional character than a wall for her to project her other characters against. His static, reliable badness allows—and occasionally causes—everyone else’s degree of goodness to flicker and change.

That concept of goodness gets put to the test first with the group’s debates over whether it’s right to take Lemoine’s money. Before long, though, the novel begins questioning the nature of do-gooding in a compromised and compromising world. It gradually transforms into a sincere interrogation of the relationship between morality and the ability to bring about positive change. Birnam Wood wants to know if a person has to be good to do good—and how to identify what goodness is in the first place.

If Birnam Wood is an exploration of idealism, its characters are the different lenses through which Catton wants us to consider it. Mira is a classic founder, charismatic and self-confident to the point of rashness. She attracts rapt audiences, which means that no one questions her Lemoine plan but Tony, a Bernie-bro type whose strident opposition has the effect of actually pushing the group toward accepting the billionaire’s money. Mira’s loyal sidekick, Shelley, is reliable and slightly gullible in the way that the unimaginative sometimes are. As the two lead a ragtag group of volunteers to camp on Lemoine’s land, their dynamic underscores the extent to which different sorts of idealists, acting in concert, can create chaos instead of change.

Mira cares only for dramatic transformation. Indeed, her minor impulses are not good at all. On the solo trip that leads to her first encounter with Lemoine, she pitches her tent at a campsite with “an honesty box for camp fees that Mira pretended not to see.” Pretended is key here: Alone, Mira has no motivation to do the little right thing; indeed, she feels herself to be above it. Meanwhile, Shelley, who would never walk by an honesty box, feels that she could do more overall good if she could be more like Mira. In this contrast, Catton captures a broader tension: between minor purists like Shelley, unable to compromise on the small stuff yet glad to go along with Mira on bigger decisions, and leaders like Mira, whose ambition leads her far past pragmatism into a dangerous dirtying of her hands.

Read: What we gain from a good-enough life

Tony is another sort of purist entirely. He cares about purity on a big scale, and he’s more than willing to fight for it. While the group builds hoop houses and plants seedlings, and Shelley, in the “stout belief that there was nothing more beneficial to group harmony than to ensure the food was plentiful and good,” spends too much of Lemoine’s donation on “cured meats, and hard cheeses, and decent coffee, and kombucha cultures,” Tony marches into the nature reserve near Birnam Wood’s new project, having declared himself an investigative journalist—he has a blog—and decided to expose the Bad Thing he feels sure Lemoine is up to.

Catton balances constantly on the razor’s edge between writing Tony as a comic pest and making him so irritating that he is nearly unreadable. Often, he is redeemed by the fact that he is correct. Tony worships “intellectual rigour;” his signature insult is “You’re not being rational here.” But as he tramps around the reserve, he begins to see that reason is not the only lens for viewing the world, even as his rational powers tell him that Lemoine (whose illegal mining, by this stage in the novel, is well under way) cannot possibly mean either Birnam Wood or the nation of New Zealand well. Tony’s willingness to take on a Goliath such as Lemoine makes him the novel’s only character with a prayer of actually changing things in a major sort of way—unlike Mira, whose attraction to power undoes many of her dreams.

Part of what seems to intrigue Catton is the question of whether it is better to aspire to what could be called Big Good—for Tony, exposing Lemoine’s mining scheme; for Mira and her volunteers, shifting public opinion on land ownership—or Small Good. Before Lemoine came on the scene, Birnam Wood did quite a lot of the latter by growing vegetables on fallow land and donating a large chunk of their yield to the hungry. Mira, plainly, was never content with this work: She wouldn’t even accept Shelley’s repeated suggestion that they launch a community-supported agriculture program, which would have given the group more financial and logistical stability and allowed them to expand their good works. Stability is undramatic, and to a person who sees herself as a mover and shaker, drama is inherently desirable. For much of Birnam Wood , it is tempting to wish Mira had stuck to her small gardens—but Tony is as big a drama lover as Mira, and Catton pushes the reader to hope against hope that he will pull his exposé off.

Tony is not a fun character to root for. Birnam Wood would be, in some sense, a more enjoyable book if Catton made it possible to imagine that Mira and Shelley could somehow band together to prevent the ecological destruction Lemoine’s mining plan will wreak, and then grow the greatest garden of all time. But from the moment the group sets up camp near the reserve, it is clear that Mira is too taken with Lemoine—or, worse still, with the oblique and exaggerated reflection of herself that she sees in him—to resist him in any way. Her infatuation and Shelley’s credulity undermine the usefulness of Birnam Wood’s work and send the novel skidding toward tragedy and disaster.

Ultimately, Birnam Wood suggests that usefulness is the only reliable metric for either Big or Small Good, imperfect though it may be. It would be useful for Tony to expose Lemoine; it is useful for Birnam Wood to feed the hungry. Quite often, Catton seems to be searching among her flawed protagonists for the bits of usefulness they produce, and to take those bits of value seriously without ignoring the ways that each character’s flaws prevent them from doing better. But she also suggests that in the face of badness—or, frankly, in the quotidian, compromising situations that do-gooders less flamboyant than Mira still find themselves in every day—caution grows more necessary, not less. As Mira never quite learns, you get nowhere by going too fast.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

About the Author

More Stories

The Woman Who Made America Take Cookbooks Seriously

When Your Every Decision Feels Torturous

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

- Get a Free Issue of our Ezine! Claim

BookBrowse Reviews Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Birnam Wood

- BookBrowse Review:

- Critics' Consensus:

- Readers' Rating:

- First Published:

- Mar 7, 2023

- Publication Information

- Write a Review

- Buy This Book

About This Book

- Reading Guide

- Media Reviews

- Reader Reviews

In Birnam Wood , her first novel since the Booker Prize-winning The Luminaries , Eleanor Catton delivers a literary thriller that's also a blistering rebuttal of late-stage capitalism.