- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

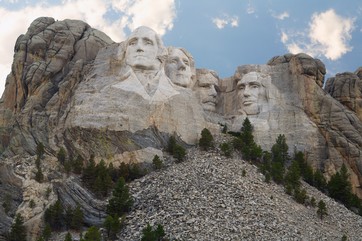

How to Write an Essay About a Famous Person in History

Last Updated: December 13, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a private tutor in San Carlos, California. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 90,326 times.

There are lots of things to think about when writing a paper about a famous person from history. Your teacher may have given you this assignment with exact instructions on who to write about and what information to include, or they may have just asked you to write about someone from history that you admire without telling you exactly what information to include. When writing the essay, take your time and rely on good information that you have collected from books and respected internet resources. Don’t underestimate the time you will need to edit your essay in order to have a final product that you can feel proud of.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- Should you choose your person or has one been assigned?

- Does your teacher want you to use a citation style? For example, they may want you to use the MLA format or maybe they want you to use Chicago Style. [1] X Research source If your teacher says they don't care, then there's nothing to worry about, but make sure that you include a “References” page at the end of your essay. On this page, you should include all of the different websites, books, and/or magazines that you used to write the essay.

- Is there a word limit? Does your teacher require a specific font or font size? Should you double-space the essay? If you're not sure, ask you teacher.

- Try to think about the things you know the person has done. Did they live a pretty normal life, but did one really cool thing? A person who was more or less “normal” could be harder to write about if your teacher wants a ten page essay. For example, although Adolf Hitler was not in any way an admirable human being, writing a historical essay about his life would be pretty easy because he did a lot of different things.

- On the other hand, if there is a historical figure you are really interested in, you will have a good time researching and writing about your person whether they led very busy lives or not. The most important thing is to choose someone you find fascinating. Try making a list of your hobbies and interests and then run a Google search to find famous people who also had one of these hobbies or interests.

- 3 Brainstorm a list of questions. Write down all of the questions you want to answer about your person. If your teacher told you what questions to answer, then use those. If your teacher did not, then this is up to you. Make sure you talk about when and where they were born, whether they had a good childhood or not, what makes them special and interesting, what they accomplished (whether good or bad), and why you find them interesting. [2] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

- Write down anything you find interesting and want to include. At the same time that you do this, write down the source of that information. For example, the name and author of the book or the address of the website.

- If you are having a hard time finding information about your person in the library, ask the librarian to help you search. They’re there to help you, and may have ways of finding information that you hadn’t thought of. Plus, if you find the information through the library, there is a better chance that you will find high quality information.

- Make sure that you understand what is considered an acceptable source of information by your teacher. For example, some teachers may consider it OK to use websites such as Wikipedia, while other teachers may not. If you’re not sure, just ask them.

- Try to include at least one primary source that was written by the person you are researching, such as a letter, journal entry, or speech. This will help you get to know the person better than you would by only using secondary sources, such as articles and textbooks.

- Write your outline so that the information is in the same order that it will be in in the paper. For example, don't put questions about how the person died before the questions about where they were born and who their parents were.

- Don’t plagiarize though! If you copy someone else's work without giving them credit for their work, this is called plagiarism. If you do find something interesting that you want to include, be sure to give credit to that person. Plagiarism is a big deal, so it’s best to learn early that it isn’t worth the risk.

Writing the Essay

- In the body, you will write about all of the information that you found when you were researching. It is the part of the paper where you answer any and all questions you have come up with.

- Your essay will be more clear if you separate different parts of this person’s life into paragraphs. For example, the first paragraph might start out by explaining when, where, and to whom this person was born. In this paragraph you might talk about what kind of childhood this person had, and whether they had any big experiences that made them into the person they were.

- In later paragraphs, you can talk about what the person did that made them famous. You might also want to include interesting things that you found about this person’s personal life. For example, whether or not they got married or whether or not they suffered from any mental disorders.

- Don't write more than one or two paragraphs for your conclusion. It should simply go over what you have written in the body about who this person was and why they were interesting and important.

- For example, you might write, “In summary, Martin Luther King Jr. was a driven man who, although his life was tragically cut short, accomplished amazing things in his life. Though his upbringing presented many challenges, he went on to become a great man who wasn’t afraid to stand up for what he believed in.”

- In the next paragraph, you can summarize what you wrote about why you find him so interesting. For example, “This great man inspires me every time I read about him. I hope that I too can stand up for the right thing if I am ever in a position to do so, even if it is difficult or scary to do so.”

- For example, you can say, “In this essay, I will be discussing a man that nearly everyone has heard of. He was a minister who became famous during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s for standing up for the rights of not only African Americans, but for all human beings.”

- After you introduce your person, you will state what you will be telling your reader about this person. For example, “In this essay, Martin Luther King Jr.’s life will be discussed beginning with his birth in Georgia, to his travels to Germany where he officially began to be known as ‘Martin,’ to his untimely death in 1968.”

- Don’t give everything away in the introduction. Think of the introduction like a movie preview. You want to give enough information to get the reader interested, but not so much information that they will already know everything else written in the essay before they read it.

- Don’t expect the second draft to come out perfectly either. The purpose of the second draft is to fix up any major spelling mistakes or grammar errors, and to see how you feel about the information you’ve written now that it’s all out there.

- A second draft is what you will give to anyone who has offered to proof read your essay, so make sure that it is easy to read. It is best to have this version typed and double-spaced so it will be easy for whoever is helping you to make notes on things you can improve in your final draft.

Editing Your Essay

- For example, a good proofreader might point out to you that your paragraph about the death of your person might be better if you put it before your paragraph which talks about the legacy this person left behind.

- Try asking a classmate to read your essay. It's a win-win for both of you because you can offer to read their essay in return. Meet up a few days after reading to talk about errors and ways to make each of your papers better.

- If the person has done a good job, they may have a lot of things to say about your paper. Try not to take anything bad they say about your paper personally. They're not trying to make you feel bad, they just want to help you get a good grade.

- Give them a physical copy of the paper that is double-spaced. This will make it easy for them to make corrections and write notes on your paper.

- Make notes as you read in a bright colored pen on a physical copy of your paper.

- Read your paper twice. The first time, focus on what you've written, and don't look for spelling mistakes or other grammar errors. While you're reading think about whether it is easy to follow and whether or not it makes sense. This will be the time to consider rearranging any information, adding anything extra, or removing anything that doesn't seem important.

- Read through the article a second time to check for grammar and spelling issues. Mark any misspelled words or typos, and make a note of any awkward sentences that you want to go back and change.

- You should also read the essay out loud. Reading the essay out loud will help you find sentences that sound strange.

- Make sure to follow any instructions your teacher has given you about how to format the document. For example, with regard to font, font size, and line spacing.

- By now, you should feel confident that you have a well-written paper. If you still feel unsure, you can ask a different person to read your essay to reassure yourself that you have caught any mistakes.

- If your teacher said they don’t care about the formatting, then stick to the defaults of your word processing program. Generally, it is a good idea to stick to font size 12 and a standard font such as Times New Roman. To make your paper easier to read, consider changing the line spacing to 1.5 or 2, unless your teacher has said not to do this.

- Your teacher probably expects you to turn in a typed copy of your essay. Unless your teacher has specifically asked for handwritten papers make sure you turn in a neat, typed copy.

Community Q&A

- Don’t put off writing your essay. As soon as you receive the assignment you can start thinking about who you want to write about and begin writing your essay outline. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Keep in mind the due date. Write down the due date in your calendar, and make sure that you hand your paper in on time. Your teacher may not accept it if is late, which means you’ve wasted a lot of time and energy for nothing. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- For some people, it can be helpful to hand write the first draft. If you are having a hard time getting started at the computer, then try switching to paper and pen to get past your initial writer’s block. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Never ever plagiarize or copy someone else’s work without giving them credit for what they have written. Plagiarizing someone else’s work can get you into big trouble at school. If you do find something that someone else wrote and want to include it in your essay, then you can do this, but be sure to cite your sources in the format required by your teacher. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 0

- Don't pay someone to write your paper for you. There are many websites online where you can supposedly pay someone to write your essay for money. Don’t try it. There is a good chance you will get caught and the website may or may not be a scam. If it is a scam you will have wasted your money and still have to write the essay yourself. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 1

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libguides.brown.edu/citations/styles

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/brainstorming/

- ↑ http://history.rutgers.edu/component/content/article?id=106:writing-historical-essays-a-guide-for-undergraduates

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/essay-outline/

- ↑ http://www.slideshare.net/alinaemma/writing-an-effective-essay-or-speech-about-an-outstandng-or-a-famous-person-a-guide-for-speaking-and-writing-exercises-on-speaking-and-writing

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/introductions/

- ↑ https://ualr.edu/writingcenter/tips-for-effective-proofreading/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

- ↑ http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/Proofreading.html

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Search Search

How to Write a Paper on a Historically Significant Person

Researching for a paper is an excellent way to learn because it trains you to gather information, interpret it, and persuasively present an informed opinion. The process teaches you a great deal, but it also equips you to contribute to ongoing discussions on a given topic.

Here’s the basic process of writing a paper on a historically significant person, either for a class or for your own personal research:

1. Select a person

Unless you’ve been assigned a person to research, you’re most likely going to begin the process from a position of interest. The person whose life and thought you want to explore will be interesting to you for one reason or another (or maybe for many reasons). But it’s important to discover the particular lens through which you want to view this person. Do you want to see how they fit within their historical context? Do you want to look back at them through the filter of contemporary debates? Do you want to focus on the way they saw the world and how that influenced those who came after them?

Having a lens in mind will help you be aware of the perspective you bring to your studies by default, because the reality is that no one approaches research in a vacuum. We all have particular ways of viewing the world, and attending to those—and being intentional about them—can help us to be intellectually honest and gracious in our assessment of historical figures.

Remember, you don’t have to be an expert on the person you want to research before you begin—that’s what the research process will accomplish. You should, however, have an interest in this person’s life. You can consult your local librarian to help you refine your topic and write a better paper.

If you are writing on a person from the Bible, then check out Logos Workflows . Workflows will help you find biblical passages related to the person’s life, review the key events the person was involved in, look for mentions of the person elsewhere in Scripture, and evaluate the person’s character qualities to discern valuable lessons from that person’s life.

2. Do your research

With a person selected, it’s time to find the resources you’re going to dig into. You may find that one resource offers the best discussion of your chosen individual, but you can’t stop there. Researching well means considering opinions that differ from each other (and probably from your own). It’s in the conversation that emerges from engaging with multiple perspectives that real insight and understanding emerge.

There are four steps to researching a paper: conducting a literature review to build your bibliography, consulting standard resources, consulting peer-reviewed journals, and consulting primary sources.

A. Conduct a literature review and build your bibliography

The process of conducting a literature review and building a bibliography is an iterative process. It’s not a one-time step; rather, it’s a step you’ll return to over and over again as you move through your research.

Essentially, in this step, you’re discovering what resources exist and cataloging them. As you begin to read the resources you discover, you’ll likely find references to other works that you’ll then want to read.

B. Consult standard sources

If the person you want to research was part of church history, then you can find useful information in encyclopedias , commentaries , theological dictionaries , concordances , and other theological reference works . The biggest help these resources will offer you at this stage is their bibliographies. Be sure to check the cross-references often.

C. Consult peer-reviewed journals

Even if you’re focusing in on a particular text by the person you’ve selected (like Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite’s The Divine Names or Augustine’s Confessions ), you need to see what your contemporaries have to say about it in order to situate your research in its context. This means consulting peer-reviewed journals. As you read, you’ll discover where scholars agree and disagree, and how the study of that person has advanced over time.

D. Consult primary sources

After completing all the previous steps, you will likely have become acquainted with the most important books for your chosen individual, both primary and secondary. Primary sources are first-hand historical documents, whereas secondary sources are books and articles that analyze or interpret the primary sources. Reading primary sources, particularly those written by the person you’re researching, is especially important.

3. Construct an outline

This step is incredibly important, but is often overlooked. It’s time to refine your angle of approach based on your research, then arrange your notes and research materials into a clear outline that will guide you as you craft a convincing and coherent argument.

4. Draft your paper

You are now ready to draft your paper. Your initial focus is to expand your outline into paragraph form as straightforwardly as possible. While your outline will be essential as you draft, don’t feel you need to stick to it absolutely. You may discover as you write that a different structure or organization will better advance your argument. Make use of relevant quotations from your research to clarify your points or add support for your arguments.

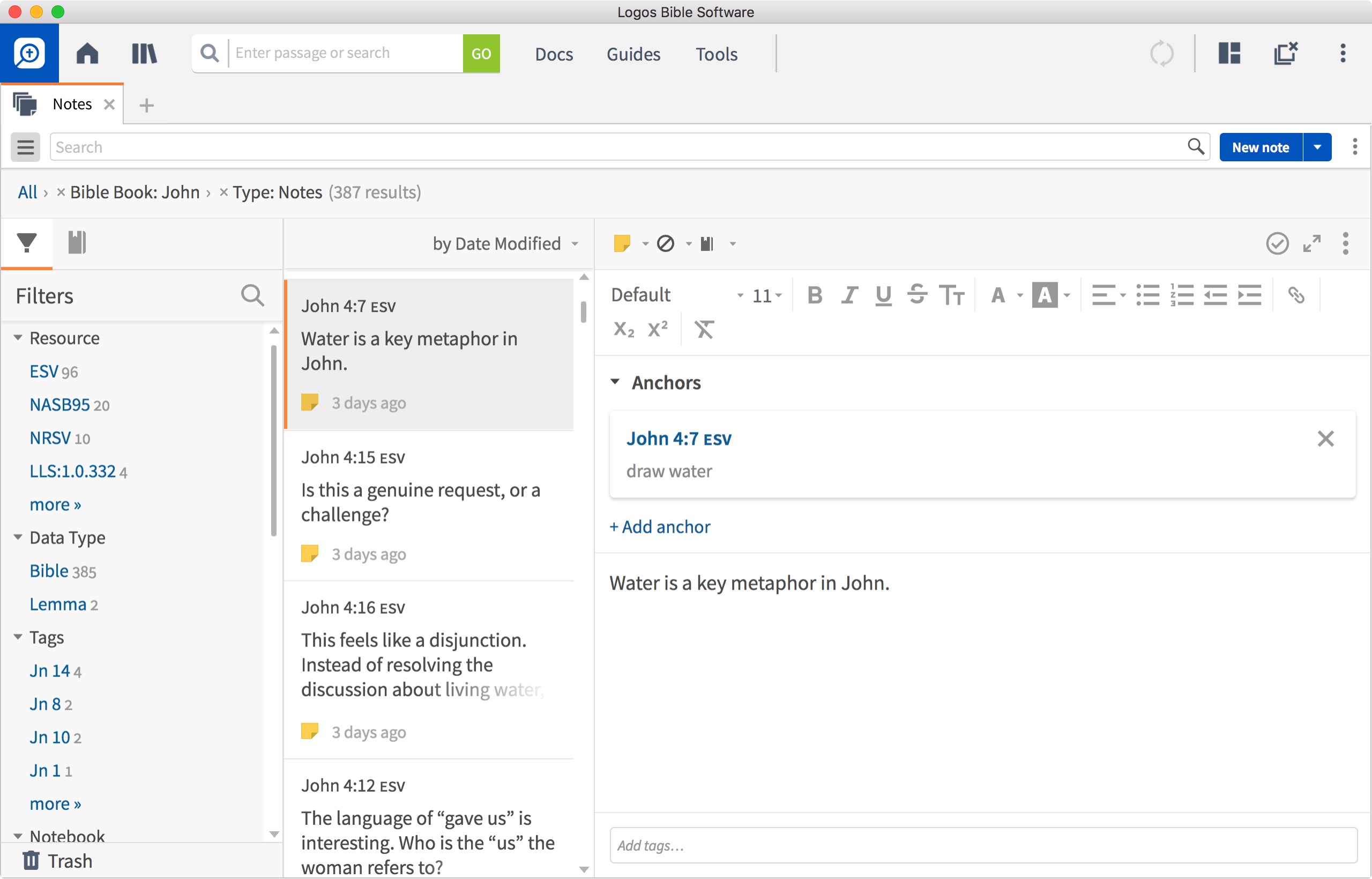

Logos Notes Tool

Use the Notes Tool in Logos to take notes as you research. Capture your thoughts on any passage, and they’ll stick to the sections you’re studying. Pull related research together into notebooks, and even share them with friends. Then, you can easily find powerful quotes to add to your paper. Learn more .

5. Revise and refine

Notice the word “draft” in the previous step. That word is intentionally selected because, arguably, the most important part of the writing process is in your revisions. Drafting gets the ball rolling, but revising is where you refine and revise your previous drafts, ensuring your argument is clear and forceful.

Before you send your final paper, you’ll want to make sure you’re writing clearly and using the right style. If you are in school, follow the rules of your academic handbook. If not, adopt a common style guide like APA, Turabian, or the SBL Handbook of Style, and consult online guides like EasyBib or the Chicago Manual of Style for help. You can also find helpful writing advice in The Elements of Style .

While this structure is helpful, you may find that some variation of it works better for you. Go with what works because, at the end of the day, a thoroughly-researched and well-written paper is what you’re after.

Further resources

Academic Journal Bundle 4.1 (560+ vols.)

Regular price:

Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity (3 vols.)

Digital list price: $899.99

Save $650.00 (72%)

Price: $249.99

Regular price: $249.99

Writing and Research: A Guide for Theological Students

Price: $23.99

Regular price: $23.99

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, rev. ed.

Digital list price: $150.00

Save $40.01 (26%)

Price: $109.99

Regular price: $109.99

The Elements of Style

Digital list price: $5.99

Save $1.00 (16%)

Price: $4.99

Regular price: $4.99

The SBL Handbook of Style: For Biblical Studies and Related Disciplines, 2nd ed.

Digital list price: $34.99

Save $7.00 (20%)

Price: $27.99

Regular price: $27.99

Saint Augustine: Confessions (The Fathers of the Church)

Digital list price: $39.99

Save $9.00 (22%)

Price: $30.99

Regular price: $30.99

The Works of Dionysius the Areopagite (2 vols.)

Collection value: $14.98

Save $4.99 (33%)

Price: $9.99

Regular price: $9.99

Logos Staff

Logos is the largest developer of tools that empower Christians to go deeper in the Bible.

Related articles

The Spirit of the Lord Is upon Me: How This Prophecy Applies to Jesus

3 Ways to Number the Ten Commandments (& Which Is Right)

2 Trees of Eden & What They Mean: Knowledge of Good & Evil vs. Life

Defiled Defined: What “Defiled” Means in the Old Testament

Your email address has been added

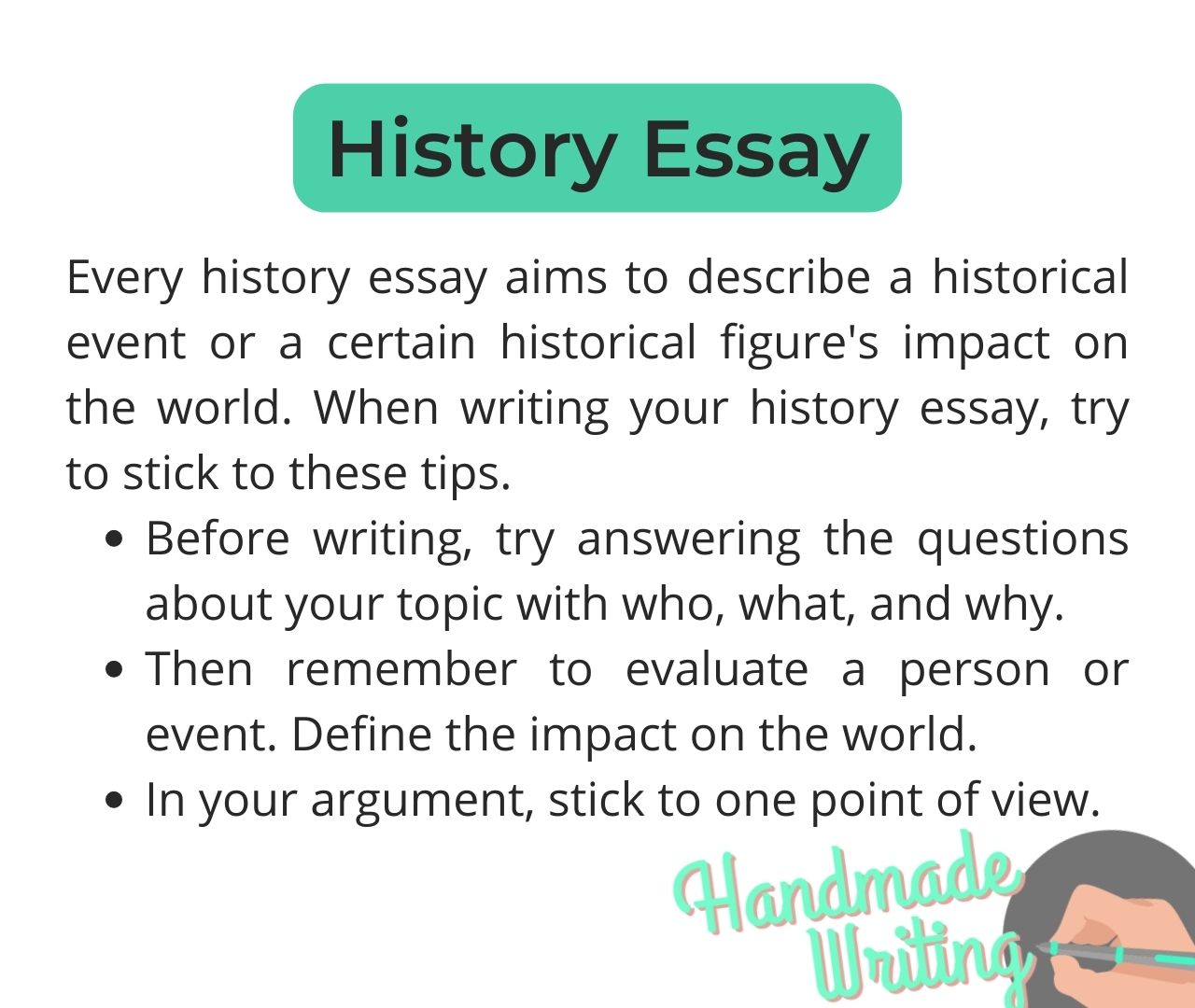

How to Write a History Essay?

04 August, 2020

10 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

There are so many types of essays. It can be hard to know where to start. History papers aren’t just limited to history classes. These tasks can be assigned to examine any important historical event or a person. While they’re more common in history classes, you can find this type of assignment in sociology or political science course syllabus, or just get a history essay task for your scholarship. This is Handmadewriting History Essay Guide - let's start!

Purpose of a History Essay

Wondering how to write a history essay? First of all, it helps to understand its purpose. Secondly, this essay aims to examine the influences that lead to a historical event. Thirdly, it can explore the importance of an individual’s impact on history.

However, the goal isn’t to stay in the past. Specifically, a well-written history essay should discuss the relevance of the event or person to the “now”. After finishing this essay, a reader should have a fuller understanding of the lasting impact of an event or individual.

Need basic essay guidance? Find out what is an essay with this 101 essay guide: What is an Essay?

Elements for Success

Indeed, understanding how to write a history essay is crucial in creating a successful paper. Notably, these essays should never only outline successful historic events or list an individual’s achievements. Instead, they should focus on examining questions beginning with what , how , and why . Here’s a pro tip in how to write a history essay: brainstorm questions. Once you’ve got questions, you have an excellent starting point.

Preparing to Write

Evidently, a typical history essay format requires the writer to provide background on the event or person, examine major influences, and discuss the importance of the forces both then and now. In addition, when preparing to write, it’s helpful to organize the information you need to research into questions. For example:

- Who were the major contributors to this event?

- Who opposed or fought against this event?

- Who gained or lost from this event?

- Who benefits from this event today?

- What factors led up to this event?

- What changes occurred because of this event?

- What lasting impacts occurred locally, nationally, globally due to this event?

- What lessons (if any) were learned?

- Why did this event occur?

- Why did certain populations support it?

- Why did certain populations oppose it?

These questions exist as samples. Therefore, generate questions specific to your topic. Once you have a list of questions, it’s time to evaluate them.

Evaluating the Question

Seasoned writers approach writing history by examining the historic event or individual. Specifically, the goal is to assess the impact then and now. Accordingly, the writer needs to evaluate the importance of the main essay guiding the paper. For example, if the essay’s topic is the rise of American prohibition, a proper question may be “How did societal factors influence the rise of American prohibition during the 1920s? ”

This question is open-ended since it allows for insightful analysis, and limits the research to societal factors. Additionally, work to identify key terms in the question. In the example, key terms would be “societal factors” and “prohibition”.

Summarizing the Argument

The argument should answer the question. Use the thesis statement to clarify the argument and outline how you plan to make your case. In other words. the thesis should be sharp, clear, and multi-faceted. Consider the following tips when summarizing the case:

- The thesis should be a single sentence

- It should include a concise argument and a roadmap

- It’s always okay to revise the thesis as the paper develops

- Conduct a bit of research to ensure you have enough support for the ideas within the paper

Outlining a History Essay Plan

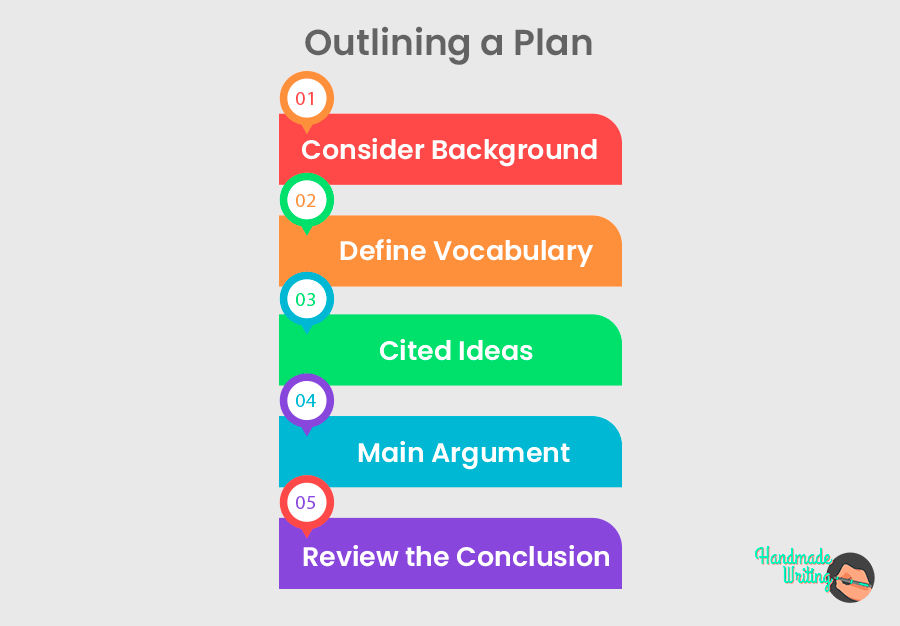

Once you’ve refined your argument, it’s time to outline. Notably, many skip this step to regret it then. Nonetheless, the outline is a map that shows where you need to arrive historically and when. Specifically, taking the time to plan, placing the strongest argument last, and identifying your sources of research is a good use of time. When you’re ready to outline, do the following:

- Consider the necessary background the reader should know in the introduction paragraph

- Define any important terms and vocabulary

- Determine which ideas will need the cited support

- Identify how each idea supports the main argument

- Brainstorm key points to review in the conclusion

Gathering Sources

As a rule, history essays require both primary and secondary sources . Primary resources are those that were created during the historical period being analyzed. Secondary resources are those created by historians and scholars about the topic. It’s a good idea to know if the professor requires a specific number of sources, and what kind he or she prefers. Specifically, most tutors prefer primary over secondary sources.

Where to find sources? Great question! Check out bibliographies included in required class readings. In addition, ask a campus Librarian. Peruse online journal databases; In addition, most colleges provide students with free access. When in doubt, make an appointment and ask the professor for guidance.

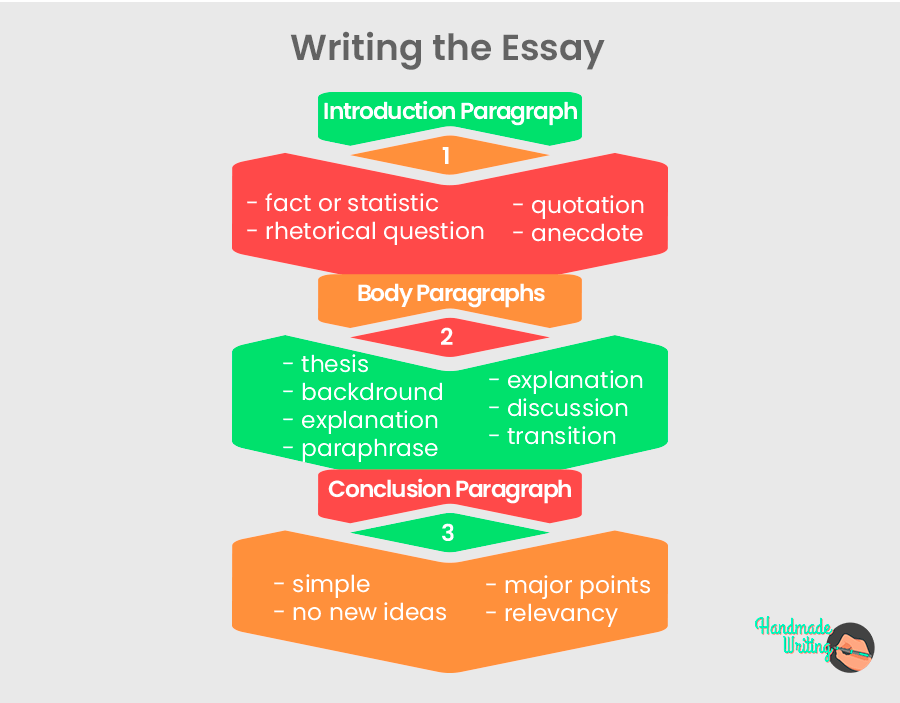

Writing the Essay

Now that you have prepared your questions, ideas, and arguments; composed the outline ; and gathered sources – it’s time to write your first draft. In particular, each section of your history essay must serve its purpose. Here is what you should include in essay paragraphs.

Introduction Paragraph

Unsure of how to start a history essay? Well, like most essays, the introduction should include an attention-getter (or hook):

- Relevant fact or statistic

- Rhetorical Question

- Interesting quotation

- Application anecdote if appropriate

Once you’ve captured the reader’s interest, introduce the topic. Similarly, present critical historic context. Namely, it is necessary to introduce any key individuals or events that will be discussed later in the essay. At last, end with a strong thesis which acts as a transition to the first argument.

Body Paragraphs

Indeed, each body paragraph should offer a single idea to support the argument. Then, after writing a strong topic sentence, the topic should be supported with correctly cited research. Consequently, a typical body paragraph is arranged as follows:

- Topic sentence linking to the thesis

- Background of the topic

- Research quotation or paraphrase #1

- Explanation and analysis of research

- Research quotation or paraphrase #2

- Transition to the next paragraph

Equally, the point of body paragraphs is to build the argument. Hence, present the weakest support first and end with the strongest. Admittedly, doing so leaves the reader with the best possible evidence.

Conclusion Paragraph

You’re almost there! Eventually, conclusion paragraphs should review the most important points in the paper. In them, you should prove that you’ve supported the argument proposed in the thesis. When writing a conclusion paragraph keep these tips in mind:

- Keep it simple

- Avoid introducing new information

- Review major points

- Discuss the relevance to today

Problems with writing Your History essay ? Try our Essay Writer Service!

Proofreading Your Essay

Once the draft is ready and polished, it’s time to proceed to final editing. What does this process imply? Specifically, it’s about removing impurities and making the essay look just perfect. Here’s what you need to do to improve the quality of your paper:

- Double check the content. In the first place, it’s recommended to get rid of long sentences, correct vague words. Also, make sure that all your paragrahps contain accurate sentences with transparent meaning.

- Pay attention to style. To make the process of digesting your essay easier, focus on crafting a paper with readable style, the one that is known to readers. Above all, the main mission here is to facilitate the perception of your essay. So, don’t forget about style accuracy.

- Practice reading the essay. Of course, the best practice before passing the paper is to read it out loud. Hence, this exercise will help you notice fragments that require rewriting or a complete removal.

History Essay Example

Did you want a history essay example? Take a look at one of our history essay papers.

Make it Shine

An A-level essay takes planning and revision, but it’s achievable. Firstly, avoid procrastination and start early. Secondly, leave yourself plenty of time to brainstorm, outline, research and write. Finally, follow these five tips to make your history essay shine:

- Write a substantial introduction. Particularly, it’s the first impression the professor will have of the paper.

- State a clear thesis. A strong thesis is easier to support.

- Incorporate evidence critically. If while researching you find opposing arguments, include them and discuss their flaws.

- Cite all the research. Whether direct quotations or paraphrases, citing evidence is crucial to avoiding plagiarism, which can have serious academic consequences.

- Include primary and secondary resources. While primary resources may be harder to find, the professor will expect them—this is, after all, a history essay.

History Essay Sample

Ready to tackle the history essay format? Great! Check out this history essay sample from an upper-level history class. While the essay isn’t perfect, the professor points out its many strengths.

Remember: start early and revise, revise, revise . We can’t revise history, but you can revise your ideas until they’re perfect.

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

How to Write a History Essay

How to write a history essay.

Written by Kalyn McCall

Writing a historical paper can seem daunting. How can you possibly capture everything about a historical moment?

I’ve got good news: you can’t.

No piece of historical work can be entirely comprehensive or encompass all aspects of a historical period, event, or figure. Instead, an effective history paper begins with a question, carefully selects evidence, and uses it to make a clear statement.

Is it possible to know everything about the past? Nope, unless you have a time machine. Historical evidence exists in fragments and is recorded from various perspectives. It’s your job to put evidence together in a way that makes sense, and it’s okay for there to be varying perspectives among your sources. So, when will you know that you have the “right” answer? That’s probably the wrong question. Rather than looking for the “right” answer, reveal the one your evidence guided you to and explain how you got there. In other words, writing history isn’t about choosing sides, but these SIDES can assist you in arriving at a clear, well-supported perspective on your topic.

This guide is meant to help students begin the process of writing history and serve as a resource for those who want to see if they’re on the right track. History assignments vary widely—so always remember to follow your instructor’s instructions. Use this guide to go from summary to analysis, beginning with careful selection of sources to effectively present their arguments, no matter what kind of historical paper assignment you have.

So, where should you start? Here:

Table of Contents:

Investigate

Strategize: Do you understand the assignment?

To start, once you get the assignment, make sure you know what your prompt is asking. What are the parameters? How does your teacher want you to respond?

We have a whole guide that explains how to unpack a prompt, but common types of historical essays include:

Narrative: an explanation of events.

Analytical: what happened, but also how and why it happened.

Comparative: compare the advantages and disadvantages of two sides or viewpoints.

Historiographical: discuss how people study history, write it, and understand it.

Creative: using art to interpret the past.

Before you write, study the central question posed by your assignment (or your research question). This will help you determine your answer and guide your research.

Investigate: What are your sources and where did you find them?

Once you identify your question, begin your research and evaluate your sources. Primary and secondary sources will serve as the backbone of the essay and provide the evidence to support your analysis. Items produced in the time period being examined are primary sources (e.g., letters, diaries, reports, clothing, artifacts, newspapers, etc.). Secondary sources are created after the period in question and provide their own analysis (e.g. scholarly articles, journals, and books).

When looking for sources, don’t just jump to Wikipedia (though if you must refer to that website, scroll to the bottom of the page to look at the article’s sources—those can possibly point you in a useful direction). Instead, utilize your local and school libraries, online databases like JSTOR or Gilder Lehrman , government websites, archives, museums, and, of course, your instructors to find quality, credible sources. For some assignments, your teacher may also provide an approved list of sources for you to choose from.

Draft: Make your case by analyzing the evidence

Complicated questions require convincing answers. Now is the time to compile your research to present a clear and concise argument. Here is an overview of how your argument can come together:

Before you write the essay, take the time to make an outline. Consider the structure of your essay. How can you organize your research so that the evidence clearly conveys an argument? Think of your main theme, the goal of the essay, and how you can present your findings. Each part should flow into the next, beginning with your main argument presented in your thesis statement.

A logical outline makes the essay easier for you to write and helps you assess its organization, logic, and cohesion. Bear in mind that while your outline will help guide your draft, it isn’t set in stone. You can (and generally should) make adjustments to its content and organization as your ideas evolve.

Introduction and Thesis

The introduction should make a bold statement that introduces your topic and compels the reader to keep going. Set the scene and tone for your paper’s topic, but don’t overgeneralize. For example, “There are many wars, and the Civil War was one of them” seems … a bit too broad. Instead, try something like, “The devastation of the Civil War shed light on America’s past while casting a shadow on its future.” To understand what this statement means, the reader must keep going. Follow the hook with an explanation, culminating in your position (i.e., your thesis). Your thesis will provide your reader with a roadmap to your paper and reveal its focus.

A general (meaning weaker) thesis might read, “The Civil War changed the course of history.” A stronger thesis would be more specific and nuanced, and might look like, “Because of emancipation, the Civil War forever changed America’s economy, attitude toward labor, and stances on citizenship.” Through a clear thesis, a reader should be able to gather where your argument is headed. As you develop your argument, be aware of possible counterarguments, so that you can acknowledge, respond to and, hopefully, refute them. For more detailed guidance on crafting a strong thesis , check out that guide.

Analyze, Don’t Summarize

As your reader makes their way through the points of your argument, they are likely to respond with, “Where’s the proof?” As a general rule, assume your reader is willing to be convinced, but won’t simply agree with you or take your word for it. It’s your job to provide readers with the information they need to understand your argument, so for every claim you make, back it up with concrete information that substantiates your position and deepens the reader’s understanding.

Primary and secondary sources will be the basis of your evidence and analysis. They are the raw materials you will weave together to make a historical argument. As such, be sure to go beyond summarizing events, dates, and tidbits of information. Instead, what information from your research helps provide evidence to support your argument, and how does it do so? Read your sources closely, and ask yourself these questions to determine what information might be most pertinent to your argument:

Who made this source, what is their background, and how does that information shape their perspective?

When was this made, where, and why?

Who is the original or intended audience of the piece? How does that shape our understanding?

How does this source compare to others of the time? Is it representative, or an outlier?

The success of an essay depends not just on how many sources you use, but how well you use them. For more guidance on how to effectively utilize sources, check out “Writing from Sources.”

Action list for more effective writing

Every type of writing has conventions and best practices that writers should follow. That said, there is no one way to write a history paper. Use your own voice, follow your teacher’s directions, and respond to each part of the prompt to show what you know.

As you critically engage with your sources, keep some things in mind:

Write in the past tense when discussing history. If a historical event took place in the past, write about it in the past.

Be precise. Focus on your thesis and only provide information that is needed to support or develop your argument.

Be formal. Try not to use casual language, and avoid using phrases like “I think.” You don’t need to pull out a thesaurus for every sentence, but do go beyond everyday conversation.

Be concise. There is power in clear, direct language.

Provide citations. Give credit where credit is due and be sure to follow formal guidelines (APA, Chicago, MLA, etc.) depending on what your professor requires. Whatever style you use, be consistent.

Avoid generalizations and cliches. Specificity is important.

Avoid presentism and anachronism. Leave the past in the past instead of connecting everything to the present (unless the prompt specifically asks for that).

Mind your chronology and keep events in order.

Place things in context. Analyze evidence in the appropriate historical setting.

Use your voice. Weave in your primary and secondary sources (see link above). Instead of letting quotations make your argument, paraphrase when possible and only quote if you must.

With a plan in place and an outline to guide you, the writing process should feel more structured. Be sure to refer back to your prompt, and check in with your instructor if you are unsure if you are on the right track.

Edit: Did you miss anything?

You will want to reread and revise your drafts multiple times to ensure your paper is logical, well organized, and polished—as a general rule, most of good writing is revising. And revising. If possible, ask your teacher or a friend to give you feedback and recommendations. This process takes time but is worth it. Once you are happy with your paper’s organization and content, you can focus on local edits by proofreading. You can also use the revision and proofreading stages of the writing process to make sure you addressed each element of the assignment. Here is a checklist that can support your editing process:

Make sure the essay responds to the prompt (especially if the prompt contains several questions). Each part of the prompt can help you assess the subject and structure of the essay.

Check the flow of the paper. Is the information presented logically? Does it follow or improve upon the outline? (Try to read your own writing from a stranger’s perspective.)

Check your dates and other specific historical details. While the essay needs to do much more than recite facts and dates, it is still important to get the evidence and historical context correct.

Review your citations. Avoid plagiarism, cite when necessary, and follow the proper citation format.

Proofread for errors in punctuation, spelling, grammar, capitalization, and the like.

If you need additional editing guidance, check out our more comprehensive guide to editing college-level papers here.

Submit: Your paper is history

Congratulations. You are done and can submit your historical paper!

One great thing about history is that there is no “right” or “wrong” answer. Much of what your essay will be judged on is the merit of your evidence and whether or not you have presented readers with believable, well-organized proof.

So have fun diving into exploring and analyzing.

Special thanks to Kalyn McCall for writing this post and contributing to other College Writing Center resources

Kalyn McCall graduated with a B.A in History, B.A. in African and African American Studies, and M.A. in Sociology from Stanford University, before pursuing her PhD in History from Harvard University. Throughout her academic pursuits, Kalyn has enjoyed working with and mentoring students in various capacities, from tutoring and academic coaching to counseling and application advising. Kalyn is particularly interested in helping first-generation and Black college students reach their potential and find their own paths. When not working, she can be found reading, playing with her dogs, or taking a nap.

Literary Analysis—How To

A Sophomore or Junior’s Guide to the Senior Thesis

College Writing Center

First-Year Writing Essentials

College-Level Writing

Unpacking Academic Writing Prompts

What Makes a Good Argument?

How to Use Sources in College Essays

Evaluating Sources: A Guide for the Online Generation

What Are Citations?

Avoiding Plagiarism

US Academic Writing for College: 10 Features of Style

Applying Writing Feedback

How to Edit a College Essay

Asking for Help in College & Using Your Resources

What Is Academic Research + How To Do It

How to Write a Literature Review

Subject or Context Specific Guides

Literary Analysis–How To

How to Write A History Essay

How to Write a History Essay, According to a History Professor

Editor & Writer

www.bestcolleges.com is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Turn Your Dreams Into Reality

Take our quiz and we'll do the homework for you! Compare your school matches and apply to your top choice today.

- History classes almost always include an essay assignment.

- Focus your paper by asking a historical question and then answering it.

- Your introduction can make or break your essay.

- When in doubt, reach out to your history professor for guidance.

In nearly every history class, you'll need to write an essay . But what if you've never written a history paper? Or what if you're a history major who struggles with essay questions?

I've written over 100 history papers between my undergraduate education and grad school — and I've graded more than 1,500 history essays, supervised over 100 capstone research papers, and sat on more than 10 graduate thesis committees.

Here's my best advice on how to write a history paper.

How to Write a History Essay in 6 Simple Steps

You have the prompt or assignment ready to go, but you're stuck thinking, "How do I start a history essay?" Before you start typing, take a few steps to make the process easier.

Whether you're writing a three-page source analysis or a 15-page research paper , understanding how to start a history essay can set you up for success.

Step 1: Understand the History Paper Format

You may be assigned one of several types of history papers. The most common are persuasive essays and research papers. History professors might also ask you to write an analytical paper focused on a particular source or an essay that reviews secondary sources.

Spend some time reading the assignment. If it's unclear what type of history paper format your professor wants, ask.

Regardless of the type of paper you're writing, it will need an argument. A strong argument can save a mediocre paper — and a weak argument can harm an otherwise solid paper.

Your paper will also need an introduction that sets up the topic and argument, body paragraphs that present your evidence, and a conclusion .

Step 2: Choose a History Paper Topic

If you're lucky, the professor will give you a list of history paper topics for your essay. If not, you'll need to come up with your own.

What's the best way to choose a topic? Start by asking your professor for recommendations. They'll have the best ideas, and doing this can save you a lot of time.

Alternatively, start with your sources. Most history papers require a solid group of primary sources. Decide which sources you want to use and craft a topic around the sources.

Finally, consider starting with a debate. Is there a pressing question your paper can address?

Before continuing, run your topic by your professor for feedback. Most students either choose a topic so broad it could be a doctoral dissertation or so narrow it won't hit the page limit. Your professor can help you craft a focused, successful topic. This step can also save you a ton of time later on.

Step 3: Write Your History Essay Outline

It's time to start writing, right? Not yet. You'll want to create a history essay outline before you jump into the first draft.

You might have learned how to outline an essay back in high school. If that format works for you, use it. I found it easier to draft outlines based on the primary source quotations I planned to incorporate in my paper. As a result, my outlines looked more like a list of quotes, organized roughly into sections.

As you work on your outline, think about your argument. You don't need your finished argument yet — that might wait until revisions. But consider your perspective on the sources and topic.

Jot down general thoughts about the topic, and formulate a central question your paper will answer. This planning step can also help to ensure you aren't leaving out key material.

Step 4: Start Your Rough Draft

It's finally time to start drafting! Some students prefer starting with the body paragraphs of their essay, while others like writing the introduction first. Find what works best for you.

Use your outline to incorporate quotes into the body paragraphs, and make sure you analyze the quotes as well.

When drafting, think of your history essay as a lawyer would a case: The introduction is your opening statement, the body paragraphs are your evidence, and the conclusion is your closing statement.

When writing a conclusion for a history essay, make sure to tie the evidence back to your central argument, or thesis statement .

Don't stress too much about finding the perfect words for your first draft — you'll have time later to polish it during revisions. Some people call this draft the "sloppy copy."

Step 5: Revise, Revise, Revise

Once you have a first draft, begin working on the second draft. Revising your paper will make it much stronger and more engaging to read.

During revisions, look for any errors or incomplete sentences. Track down missing footnotes, and pay attention to your argument and evidence. This is the time to make sure all your body paragraphs have topic sentences and that your paper meets the requirements of the assignment.

If you have time, take a day off from the paper and come back to it with fresh eyes. Then, keep revising.

Step 6: Spend Extra Time on the Introduction

No matter the length of your paper, one paragraph will determine your final grade: the introduction.

The intro sets up the scope of your paper, the central question you'll answer, your approach, and your argument.

In a short paper, the intro might only be a single paragraph. In a longer paper, it's usually several paragraphs. The introduction for my doctoral dissertation, for example, was 28 pages!

Use your introduction wisely. Make a strong statement of your argument. Then, write and rewrite your argument until it's as clear as possible.

If you're struggling, consider this approach: Figure out the central question your paper addresses and write a one-sentence answer to the question. In a typical 3-to-5-page paper, my shortcut argument was to say "X happened because of A, B, and C." Then, use body paragraphs to discuss and analyze A, B, and C.

Tips for Taking Your History Essay to the Next Level

You've gone through every step of how to write a history essay and, somehow, you still have time before the due date. How can you take your essay to the next level? Here are some tips.

- Talk to Your Professor: Each professor looks for something different in papers. Some prioritize the argument, while others want to see engagement with the sources. Ask your professor what elements they prioritize. Also, get feedback on your topic, your argument, or a draft. If your professor will read a draft, take them up on the offer.

- Write a Question — and Answer It: A strong history essay starts with a question. "Why did Rome fall?" "What caused the Protestant Reformation?" "What factors shaped the civil rights movement?" Your question can be broad, but work on narrowing it. Some examples: "What role did the Vandal invasions play in the fall of Rome?" "How did the Lollard movement influence the Reformation?" "How successful was the NAACP legal strategy?"

- Hone Your Argument: In a history paper, the argument is generally about why or how historical events (or historical changes) took place. Your argument should state your answer to a historical question. How do you know if you have a strong argument? A reasonable person should be able to disagree. Your goal is to persuade the reader that your interpretation has the strongest evidence.

- Address Counterarguments: Every argument has holes — and every history paper has counterarguments. Is there evidence that doesn't fit your argument? Address it. Your professor knows the counterarguments, so it's better to address them head-on. Take your typical five-paragraph essay and add a paragraph before the conclusion that addresses these counterarguments.

- Ask Someone to Read Your Essay: If you have time, asking a friend or peer to read your essay can help tremendously, especially when you can ask someone in the class. Ask your reader to point out anything that doesn't make sense, and get feedback on your argument. See whether they notice any counterarguments you don't address. You can later repay the favor by reading one of their papers.

Congratulations — you finished your history essay! When your professor hands back your paper, be sure to read their comments closely. Pay attention to the strengths and weaknesses in your paper. And use this experience to write an even stronger essay next time.

Explore More College Resources

How to write a research paper: 11-step guide.

Ask a Professor: How to Ask for an Extension on a Paper

The value of a history degree.

BestColleges.com is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Compare Your School Options

View the most relevant schools for your interests and compare them by tuition, programs, acceptance rate, and other factors important to finding your college home.

Historical Figures Essay Examples and Topics

Tips for writing a historical figures essay.

If you’re working on a paper about a famous historical figure who inspires you, essay writing should start with thorough research. Conduct a study on this person’s biography with a focus on them and their life. Make sure you not only cover their life but also evaluate it, demonstrating your understanding of the historical figure essay format.

And keep in mind these few tricks below! They will help you achieve better structure and give you more ideas for your inspirational people and historical figures essay.

When writing essays on biographical studies, you should be using many types of sources.

This requirement means that your paper should reference books, autobiographical evidence, and maybe even paintings and voice recordings. Having supporting information on the history of the period that you are studying is also essential.

Sources of a personal nature, such as a person’s letters, memoirs, and diaries, are valuable, and you should use them in your essay. However, you must also be aware that they may be biased, portraying the person writing them in a much better light.

Do not be afraid to be critical of what you read and, if other trusted authors support your concerns, voice them in your essay. An excellent example of a biography essay is one that does not mindlessly praise their subject.

Covering biographical studies topics requires using sources that may give your subject a negative evaluation. Having titles in your bibliography that oppose the character you are writing about makes your essay well rounded and comprehensive.

Taking the many personalities of the female suffrage movement in the USA as a sample topic, you could use books on both sides of the votes for women argument.

Find more ideas for writing better essays on Biographical Studies on our website!

531 Best Essay Examples on Historical Figures

Michael jackson: his life and career.

- Words: 2773

The Rise of Hitler to Power

- Words: 1680

Leonardo Da Vinci

- Words: 1355

Exploring Transitional Life Events Through Thematic Analysis

- Words: 1923

Napoleon: A Child and Destroyer of the Revolution

Cleopatra and her influence on the ptolemaic dynasty.

- Words: 1456

The Comparison of the Speeches by Martin Luther King and Alicia Garza

Compare and contrast: w.e.b. dubois and booker t. washington, mahatma gandhi’s leadership.

- Words: 2039

Khalid Ibn Al Walid

- Words: 1551

Personality of Julius Caesar and His Effect on Rome

- Words: 1455

Role Model: Nelson Mandela

- Words: 1652

Martin Luther King Jr. vs. Nelson Mandela

Pablo escobar is a robin hood or a villain.

- Words: 3536

Comparing Sheikha Hind bint Maktoum bin Juma Al Maktoum and Princess Haya bint al Hussein

A closer look at the life of princess diana.

- Words: 3000

Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist

- Words: 1161

Historical Interview with William Shakespeare

- Words: 1431

Carl Friedrich Gauss: The Greatest Mathematician

- Words: 1262

Queen Elizabeth I as the Greatest Monarch in England

- Words: 1011

Indira Gandhi: Autocratic Leader of India

- Words: 1428

Alfred Marshall and His Contribution to Economics

- Words: 1107

Moshweshewe: Letter to Sir George Grey

Napoleon bonaparte and its revolutions, julius caesar an iconic roman.

- Words: 1507

Angelina Jolie, Her Life and Behavior

- Words: 1513

Fidel Castro: The Cult of Personality

- Words: 2796

“Long Walk to Freedom” by Nelson Mandela

Napoleon: leadership style, bill gates: life and contributions.

- Words: 2253

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Role in the French Revolution

- Words: 1956

Political Impacts of Julius Caesar

- Words: 1619

Comparison of Gandhi’s and Hitler’s Leadership

Sam houston: character traits and personality, the life of shaykh abd al-aziz bin baz.

- Words: 2022

Sojourner Truth

- Words: 1377

Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson Comparison

Heroes – nelson mandela, man and monster: the life of adolf hitler.

- Words: 1371

Sonni Ali: The King of the Songhai Empire

Joseph haydn’s contract with the esterhazy court, steve jobs’ impacts on the world.

- Words: 2968

Self-immolation of Thich Quang Duc and Its Impact

Julius caesar’ desire for power.

- Words: 2535

Diogenes and Alexander

What made pericles an outstanding leader in athens.

- Words: 1511

Muhammad Ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi

Why julius caesar was assassinated.

- Words: 2156

Malcolm X and Frederick Douglass’ Comparison

- Words: 1488

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Legacy

- Words: 1883

World War 2 Leaders Comparison: Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler

- Words: 2756

Mohandas Gandhi’s “Hind Swaraj”

Fatima bint muhammad, the daughter of a prophet.

- Words: 1258

Victoria, the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain

- Words: 1413

George Appo’s Autobiography

- Words: 1403

Who was Pedro Calosa?

Researching of mark zuckerberg’s creativity.

- Words: 1173

Patty Smith Hill and Her Contribution to Education

The life and legacy of john wesley.

- Words: 1769

Hatshepsut’s Leadership and Accomplishments

The egyptian pharaoh vs. us president comparison, george washington carver, his life and research, the life of imam al-bukhari.

- Words: 1451

Friederich Engels: Industrial Manchester, 1844

- Words: 1131

Stephen Hawking: A Prominent Scientist

Clara campoamor rodríguez: biography and key achivements, amelia earhart: contributing to the aviation development, the life of idi amin and his dictatorship.

- Words: 2329

The Elusive Jack the Ripper: A Hero or Villain?

- Words: 2259

Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan

- Words: 4077

Yusuf ibn-Ayyub Salah-al-Din

- Words: 1410

Albert Einstein: The Life of a Genius

- Words: 2763

Jamie Oliver and Leadership in the Food Industry

- Words: 3249

Hitler’s Speech in Reaction to the Treaty of Versailles

John brown and his beliefs about slavery.

- Words: 1311

Hitler: A Study in Tyranny by Alan Bullock

- Words: 1399

Nelson Mandela: Analysis of Personality

The probable cause of marilyn monroe’s death.

- Words: 1916

Mandela’s Leadership

- Words: 2108

Genghis Khan in The Secret History of the Mongols and The History of the World Conquer

- Words: 1171

Otto von Bismarck: Life and Significance

- Words: 2748

The Life of John Pierpont Morgan

- Words: 1098

Jackson’s and Jefferson’s Presidency: Comparative Analysis

Jeff bezos: the richest man in modern history, martin luther king and winston churchill’s leadership styles.

- Words: 2829

The Life and Work of André Rieu

- Words: 1220

John Pierpont Morgan: The Man Who Financed America

- Words: 1640

The Life of Benjamin Franklin

The life and music of frederic chopin.

- Words: 1069

Napoleon Bonaparte: His Successes and Failures

The life of zora neale hurston.

- Words: 2499

Last Night I dreamed of Peace

- Words: 1054

Cleopatra’s Life, From Her Ascension to the Throne to Solemn Death

Why abigail williams is blamed for the salem witch trials, women who changed the world: marie curie.

- Words: 1705

Ali ibn Abi Talib: Biography

Historical figure in social work: jane addams, elizabeth bloomer ford’s leadership development, franklin roosevelt and adolf hitler: leaders ways, hiram fong: political and life history.

- Words: 1121

Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1988 UN Speech

Nelson mandela’s biography and influence, muhammad ibn musa al-khwarizmi’s science contributions.

- Words: 1603

Eli Whitney Life and Influence

“nelson mandela, autobiography” book.

- Words: 1132

Abbas ibn Firnas, a Berber Andalusian Polymath

The life of harold cardinal.

- Words: 1118

Mao Zedong: A Blessing or Curse for the Chinese People

- Words: 2300

Analysis of Christopher Columbus Voyage

- Words: 1275

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis: Life and Legacy

- Words: 1350

Omar Khayyam: Life and Contributions

Steve jobs: the life and times of the great entrepreneur.

- Words: 1653

“Women’s Rights Are Human Rights” by Hillary Clinton

- Words: 1084

Johannes Junius: Accusation of Witchcraft

Benito mussolini, the key figure of italian fascism.

- Words: 1186

“Common Sense and Related Writings” by Thomas Slaughter

Guglielmo marconi: the inventor of the telegraph.

- Words: 1359

Mao Zedong’s Impact on the World

Ralph waldo emerson, an american essayist, maggie l. walker national historic site.

- Words: 1103

A guide to writing history essays

This guide has been prepared for students at all undergraduate university levels. Some points are specifically aimed at 100-level students, and may seem basic to those in upper levels. Similarly, some of the advice is aimed at upper-level students, and new arrivals should not be put off by it.

The key point is that learning to write good essays is a long process. We hope that students will refer to this guide frequently, whatever their level of study.

Why do history students write essays?

Essays are an essential educational tool in disciplines like history because they help you to develop your research skills, critical thinking, and writing abilities. The best essays are based on strong research, in-depth analysis, and are logically structured and well written.

An essay should answer a question with a clear, persuasive argument. In a history essay, this will inevitably involve a degree of narrative (storytelling), but this should be kept to the minimum necessary to support the argument – do your best to avoid the trap of substituting narrative for analytical argument. Instead, focus on the key elements of your argument, making sure they are well supported by evidence. As a historian, this evidence will come from your sources, whether primary and secondary.

The following guide is designed to help you research and write your essays, and you will almost certainly earn better grades if you can follow this advice. You should also look at the essay-marking criteria set out in your course guide, as this will give you a more specific idea of what the person marking your work is looking for.

Where to start

First, take time to understand the question. Underline the key words and consider very carefully what you need to do to provide a persuasive answer. For example, if the question asks you to compare and contrast two or more things, you need to do more than define these things – what are the similarities and differences between them? If a question asks you to 'assess' or 'explore', it is calling for you to weigh up an issue by considering the evidence put forward by scholars, then present your argument on the matter in hand.

A history essay must be based on research. If the topic is covered by lectures, you might begin with lecture and tutorial notes and readings. However, the lecturer does not want you simply to echo or reproduce the lecture content or point of view, nor use their lectures as sources in your footnotes. They want you to develop your own argument. To do this you will need to look closely at secondary sources, such as academic books and journal articles, to find out what other scholars have written about the topic. Often your lecturer will have suggested some key texts, and these are usually listed near the essay questions in your course guide. But you should not rely solely on these suggestions.

Tip : Start the research with more general works to get an overview of your topic, then move on to look at more specialised work.

Crafting a strong essay

Before you begin writing, make an essay plan. Identify the two-to-four key points you want to make. Organize your ideas into an argument which flows logically and coherently. Work out which examples you will use to make the strongest case. You may need to use an initial paragraph (or two) to bring in some context or to define key terms and events, or provide brief identifying detail about key people – but avoid simply telling the story.

An essay is really a series of paragraphs that advance an argument and build towards your conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on one central idea. Introduce this idea at the start of the paragraph with a 'topic sentence', then expand on it with evidence or examples from your research. Some paragraphs should finish with a concluding sentence that reiterates a main point or links your argument back to the essay question.

A good length for a paragraph is 150-200 words. When you want to move to a new idea or angle, start a new paragraph. While each paragraph deals with its own idea, paragraphs should flow logically, and work together as a greater whole. Try using linking phrases at the start of your paragraphs, such as 'An additional factor that explains', 'Further', or 'Similarly'.

We discourage using subheadings for a history essay (unless they are over 5000 words in length). Instead, throughout your essay use 'signposts'. This means clearly explaining what your essay will cover, how an example demonstrates your point, or reiterating what a particular section has added to your overall argument.

Remember that a history essay isn't necessarily about getting the 'right' answer – it's about putting forward a strong case that is well supported by evidence from academic sources. You don't have to cover everything – focus on your key points.

In your introduction or opening paragraph you could indicate that while there are a number of other explanations or factors that apply to your topic, you have chosen to focus on the selected ones (and say why). This demonstrates to your marker that while your argument will focus on selected elements, you do understand the bigger picture.

The classic sections of an essay

Introduction.

- Establishes what your argument will be, and outlines how the essay will develop it

- A good formula to follow is to lay out about 3 key reasons that support the answer you plan to give (these points will provide a road-map for your essay and will become the ideas behind each paragraph)

- If you are focusing on selected aspects of a topic or particular sources and case studies, you should state that in your introduction

- Define any key terms that are essential to your argument

- Keep your introduction relatively concise – aim for about 10% of the word count

- Consists of a series of paragraphs that systematically develop the argument outlined in your introduction

- Each paragraph should focus on one central idea, building towards your conclusion

- Paragraphs should flow logically. Tie them together with 'bridge' sentences – e.g. you might use a word or words from the end of the previous paragraph and build it into the opening sentence of the next, to form a bridge

- Also be sure to link each paragraph to the question/topic/argument in some way (e.g. use a key word from the question or your introductory points) so the reader does not lose the thread of your argument

- Ties up the main points of your discussion

- Should link back to the essay question, and clearly summarise your answer to that question

- May draw out or reflect on any greater themes or observations, but you should avoid introducing new material

- If you have suggested several explanations, evaluate which one is strongest

Using scholarly sources: books, journal articles, chapters from edited volumes

Try to read critically: do not take what you read as the only truth, and try to weigh up the arguments presented by scholars. Read several books, chapters, or articles, so that you understand the historical debates about your topic before deciding which viewpoint you support. The best sources for your history essays are those written by experts, and may include books, journal articles, and chapters in edited volumes. The marking criteria in your course guide may state a minimum number of academic sources you should consult when writing your essay. A good essay considers a range of evidence, so aim to use more than this minimum number of sources.

Tip : Pick one of the books or journal articles suggested in your course guide and look at the author's first few footnotes – these will direct you to other prominent sources on this topic.

Don't overlook journal articles as a source. They contain the most in-depth research on a particular topic. Often the first pages will summarise the prior research into this topic, so articles can be a good way to familiarise yourself with what else has 'been done'.

Edited volumes can also be a useful source. These are books on a particular theme, topic or question, with each chapter written by a different expert.

One way to assess the reliability of a source is to check the footnotes or endnotes. When the author makes a claim, is this supported by primary or secondary sources? If there are very few footnotes, then this may not be a credible scholarly source. Also check the date of publication, and prioritise more recent scholarship. Aim to use a variety of sources, but focus most of your attention on academic books and journal articles.

Paraphrasing and quotations

A good essay is about your ability to interpret and analyse sources, and to establish your own informed opinion with a persuasive argument that uses sources as supporting evidence. You should express most of your ideas and arguments in your own words. Cutting and pasting together the words of other scholars, or simply changing a few words in quotations taken from the work of others, will prevent you from getting a good grade, and may be regarded as academic dishonesty (see more below).

Direct quotations can be useful tools if they provide authority and colour. For maximum effect though, use direct quotations sparingly – where possible, paraphrase most material into your own words. Save direct quotations for phrases that are interesting, contentious, or especially well-phrased.

A good writing practice is to introduce and follow up every direct quotation you use with one or two sentences of your own words, clearly explaining the relevance of the quote, and putting it in context with the rest of your paragraph. Tell the reader who you are quoting, why this quote is here, and what it demonstrates. Avoid simply plonking a quotation into the middle of your own prose. This can be quite off-putting for a reader.

- Only include punctuation in your quote if it was in the original text. Otherwise, punctuation should come after the quotation marks. If you cut out words from a quotation, put in three dots (an ellipsis [ . . .]) to indicate where material has been cut

- If your quote is longer than 50 words, it should be indented and does not need quotation marks. This is called a block quote (use these sparingly: remember you have a limited word count and it is your analysis that is most significant)

- Quotations should not be italicised

Referencing, plagiarism and Turnitin

When writing essays or assignments, it is very important to acknowledge the sources you have used. You risk the charge of academic dishonesty (or plagiarism) if you copy or paraphrase words written by another person without providing a proper acknowledgment (a 'reference'). In your essay, whenever you refer to ideas from elsewhere, statistics, direct quotations, or information from primary source material, you must give details of where this information has come from in footnotes and a bibliography.

Your assignment may be checked through Turnitin, a type of plagiarism-detecting software which checks assignments for evidence of copied material. If you have used a wide variety of primary and secondary sources, you may receive a high Turnitin percentage score. This is nothing to be alarmed about if you have referenced those sources. Any matches with other written material that are not referenced may be interpreted as plagiarism – for which there are penalties. You can find full information about all of this in the History Programme's Quick Guide Referencing Guide contained in all course booklets.

Final suggestions

Remember that the easier it is to read your essay, the more likely you are to get full credit for your ideas and work. If the person marking your work has difficulty reading it, either because of poor writing or poor presentation, they will find it harder to grasp your points. Try reading your work aloud, or to a friend/flatmate. This should expose any issues with flow or structure, which you can then rectify.

Make sure that major and controversial points in your argument are clearly stated and well- supported by evidence and footnotes. Aspire to understand – rather than judge – the past. A historian's job is to think about people, patterns, and events in the context of the time, though you can also reflect on changing perceptions of these over time.

Things to remember

- Write history essays in the past tense

- Generally, avoid sub-headings in your essays

- Avoid using the word 'bias' or 'biased' too freely when discussing your research materials. Almost any text could be said to be 'biased'. Your task is to attempt to explain why an author might argue or interpret the past as they do, and what the potential limitations of their conclusions might be

- Use the passive voice judiciously. Active sentences are better!

- Be cautious about using websites as sources of information. The internet has its uses, particularly for primary sources, but the best sources are academic books and articles. You may use websites maintained by legitimate academic and government authorities, such as those with domain suffixes like .gov .govt .ac or .edu