Short Essay on Bullying

Essay Examples

This is an example of an essay on bullying. It is an expository essay that shows how a large number of children and young people suffer from harassment not only in primary and secondary school but also via the internet.

Title of the essay: “Cyberbullying and its repercussions in real life”

Type of essay: exhibition essay, length: 434 words, topic: bullying.

Bullying has always been present in schools and social circles of different kinds. However, with the emergence of social networks has become a subject that arouses the concern of parents and society in general. This is because cases have already been known that have resulted in fatal consequences, where the affected could not stand the situation anymore. For these reasons, it is important to analyze cyberbullying and its repercussions in real life.

Initially, the term bullying was used to define an extraordinary event, an anomaly that occurred in schools and that sought to be disconnected from the world of adults. But the problem is born of the violence that every human being is capable of manifesting, and that is part of its history. It is something that has been studied by specialists in the field of social sciences, being brought out from the late twentieth century as a recurring behavior. Now that it is recognized and considered inadmissible, the cases arouse great public interest.

Although initially his concept was limited to the school case and consisted of the repetitive harassment and intimidation carried out by the aggressor (s). Currently, the Internet and especially social networks have seen the emergence of cyberbullying. In this way, people of all ages are prey to psychological aggression of different types and this has the ability to deteriorate their health to the full extent, as they represent their humiliation and destroy their self-esteem, affecting their mind that then affects the body.

For the most part, the victims are usually adolescents between the ages of twelve and seventeen. Also, women are the most likely to experience these attacks. They are insults, diatribes, abuse and threats that take the form of text messages, audios, photos, and videos. Causing the suffering of millions of young people from different countries, who tend to develop disorders such as depression, which can then lead to suicide.

Then, the possible repercussions of cyberbullying in real life are alarming. Not only do we bring about a general deterioration in the health of the individual. But it is a reflection of the level of violence that characterizes the current world, and the lack of sensitivity that the new generations have in this regard. In addition, it must become a reason to put aside the hate speech that has always been part of society. Where there is discrimination based on gender, religion, sexual orientation or race.

Share this Post to Help Fellow Students

Related Posts

Short essay on dubai, short essay on apple company, expository essay on emotional intelligence example.

- Write my thesis

- Thesis writers

- Buy thesis papers

- Bachelor thesis

- Master's thesis

- Thesis editing services

- Thesis proofreading services

- Buy a thesis online

- Write my dissertation

- Dissertation proposal help

- Pay for dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help online

- Buy dissertation online

- Cheap dissertation

- Dissertation editing services

- Write my research paper

- Buy research paper online

- Pay for research paper

- Research paper help

- Order research paper

- Custom research paper

- Cheap research paper

- Research papers for sale

- Thesis subjects

- How It Works

What Is a Good Thesis Statement About Bullying?

Unfortunately, bullying is still part of our society despite civilization and technology. But, that does not mean the issue cannot be addressed and fixed. It is the responsibility of parents, teachers, and institutions to find a way to reduce the blow of bullying in our society for everyone to be safe and happy. Are you concerned about bullying and want to be a part of the solution? One of the ways to do this is by writing an interesting essay that educates about bullying and its effects. As a part of the project, you will need a thesis statement for a bullying essay that stands out.

As much as you want to address the nasty effects of bullying, you also need to pass your exams. That is why you need to get a thesis about bullying that will impress your professor. Let us learn more here.

What’s a Bullying Thesis Statement?

- How to Write a Thesis Statement about Bullying?

What Is a Good Thesis Statement For Bullying?

Interesting examples on thesis statement for bullying research paper, straightforward thesis statement for bullying essay examples, exciting thesis statement on cyberbullying homework, our writing services guarantees good thesis statement.

A bullying thesis statement helps you address an issue about bullying. It needs to include the topic of the research paper you are writing about and the claim you have about the bullying topic. Your thesis statement determines whether your paper will stand out.

Which Of The Following Statements About Bullying Is True?

Most people are oblivious to cyberbullying and its effect. So you need first to understand what bullying is to develop a great thesis statement for bullying. Below are four statements that you can read to determine the truth about bullying.

- Bullying is a growing phase that children will grow out of.

- Bullying does not have to be physical; it can also be cyberbullying, verbal, and emotional.

- Bullying is not harmful.

- As children mature, they will learn positive behavior on their own.

What do you think is the correct answer? All the above statements are false except b. Bullying is not limited to the physical like fighting and hitting. Cyberbullying, verbal and emotional abuse are all bullying, and they all have devastating effects on the individual or group of people getting bullied.

How to Write a Thesis Statement About Bullying?

The thesis on bullying should be under the introduction. Most students prefer writing a statement when they complete their introduction. But the best way to write a thesis is by finishing your research.

Note that the thesis statement needs to be a summary of your research. You will have a better idea of what your essay is all about once you have completed your project. Ensure that the subject is exciting and as per your tutor’s instruction.

A good thesis statement on bullying needs to be a great impression so that it can hook your instructor or any other person who will read your thesis statement. It needs to be the hook to your essay and motivate the readers. The bullying essay thesis statement needs to be;

- An interpretation of the subject

- Precise, forceful, and confident

- It should challenge the readers

Bullying Thesis Statement Examples

If you have a hard time creating a thesis statement about bullying that will make your essay stand out, worry no more. Our team of experts has combined a list of thesis statements on cyberbullying you can use in your essay to impress your professors. Here we go!

You can make your essay research paper interesting by choosing the right thesis statement about bullying to use. In case you are not sure, here is a list you can choose from.

- Bullying and its effects on youth, and some possible solutions to the problem it causes.

- There are several ideas and concepts that most institutes have come up with to help stop bullying, but the challenge is the implementation of these policies.

- International progress can be hasted by the eradication of bully in and so government bodies should cultivate solutions to address the matter.

- Corporate bullying could push individuals into isolation, leading to depression and suicide.

- Bullying has been ignored for a long time, even though it has been a problem in the school system; people have only recently started discussing it.

A bullying thesis does not have to be complex. In fact, at times keeping the thesis statement on bullying essay simple could help capture the attention of your tutor and help improve your grade. Here is a look at the straightforward statements about bullying.

- The effects of physical bullying are depression, stress, withdrawal, physical, and emotional problems, which could destroy a child’s life.

- Parents and tutors should always be on the lookout for any bullying so they can fix the problem before it gets out of control.

- Most bullies have emotional or physical abuse, so they turn to bullies to help them feel in a position of power.

- Bullying could affect the mental health of the person being bullied, affecting their everyday life.

- Bullies have a hard time following the regulations, caring for other people, and having self-control.

Cyberbullying is often underestimated, and it makes people feel as though they are not good enough and do not deserve to live. Use these examples in your homework.

- School violence and cyberbullying attacks affect everyone who attends the school and compromise students’ safety.

- Cyberbullying is not new and can be used in many ways to bring individuals or a group down, yet not much is being done to address the issue.

- Proper measures should be implemented to help better predict communication during cyberbullying episodes.

- As technology advances, teens have become more prone to the internet’s dangers like cyberbullying.

- A look at the similarities and differences between bullying and cyberbullying and the best way to handle both situations.

Are you still wondering what’s a good thesis statement for bullying is? Reach out to our writing service today. We have skilled writers to help you get the best bullying thesis for a research paper. We can also write the research paper for you and ensure you attain the best grades. So get in touch with us today.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Advertisement

Consequences of Childhood Bullying on Mental Health and Relationships for Young Adults

- Original Paper

- Published: 18 July 2018

- Volume 28 , pages 2379–2389, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Ellen W. deLara 1

12k Accesses

33 Citations

44 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

An Author Correction to this article was published on 02 August 2019

This article has been updated

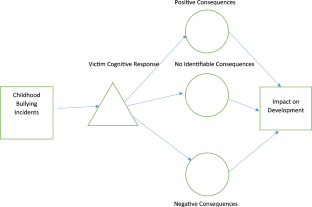

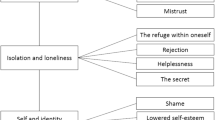

Childhood bullying is a well-known public health problem world-wide. Research has described numerous health and mental health effects on victims, bullies, and bystanders. While there are studies of contemporaneous consequences, there is still much to be discovered in terms of the impact of childhood bullying lasting into adult life. This qualitative inquiry investigated the aftermath of childhood bullying for young adults in terms of their health, mental health, and relationship issues. Further, it asked participants for their definitions of bullying. The study was part of a mixed-methods inquiry. For the qualitative portion, 72 graduate and undergraduate students in the U.S., ages 18 to 29, participated as a purposive sample. The majority of participants were Caucasian and female, though 28% percent represented minority groups. Semi-structured interviews were conducted lasting approximately 1 h each. A participatory action research approach was taken to understand the lived experiences and perceptions of the young adults. Grounded theory was utilized in reviewing the data for thematic responses. Member checks and triangulation were employed to substantiate credibility, authenticity, and coherence of the data. Content analysis revealed lasting consequences in (a) mental and psychological well-being (b) eating disorders, weight, and body image, and (c) relationship and trust issues. Results are indicative of the need for further research on childhood bullying as it affects later adolescent and young adult development. Understanding the aftermath of childhood bullying is important in informing bullying interventions and maintaining a focus on early prevention efforts.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The experience of bullying among adolescents receiving mental health care: an interpretative phenomenological analysis

Marjorie Roques, Solène Spiers, … Fabian Guénolé

Do Research Definitions of Bullying Capture the Experiences and Understandings of Young People? A Qualitative Investigation into the Characteristics of Bullying Behaviour

Jenny Jeffrey & Jaimee Stuart

Why do children and adolescents bully their peers? A critical review of key theoretical frameworks

Hannah J. Thomas, Jason P. Connor & James G. Scott

Change history

02 august 2019.

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Allison, S., Roeger, L., & Reinfeld-Kirkman, N. (2009). Does school bullying affect adult health? Population survey of health-related quality of life and past victimization. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , 43 (12), 1163–1170. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048670903270399prevention .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Arseneault, L., Cannon, M., Fisher, H.L., Polanczyk, G., Moffitt, T.E., & Caspi, A. (2011). Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: a genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry , 168 (1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040567 .

Baumeister, R.F., & Leary, M.R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin , 117 (3), 497 https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 .

Article Google Scholar

Beck, A.T., Davis, D.D. & Freeman, A. (Eds.) (2015). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders . New York, N. Y: Guilford Publications.

Google Scholar

Birkett, M., Espelage, D.L., & Koenig, B. (2009). LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 38 (7), 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bowes, L., Arsenault, L., Maughan, B., Taylor, A., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. (2009). School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’s bullying involvement: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 48 (5), 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017 .

Caracelli, V., & Greene, J. (1997). Crafting mixed-method evaluation designs. New Directions for Evaluation , 74 , 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1069 .

Carlisle, N., & Rofes, E. (2007). School bullying: Do adult survivors perceive long-term effects? Traumatology , 13 (1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765607299911 .

Copeland, W.E., Bulik, C.M., Zucker, N., Wolke, D., Lereya, S.T., & Costello, E.J. (2015). Does childhood bullying predict eating disorder symptoms? A prospective, longitudinal analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 48 (8), 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22459 .

Copeland, W.E., Wolke, D., Angold, A., & Costello, E.J. (2013). Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry , 70 (4), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504 .

Copeland, W.E., Wolke, D., Lereya, S.T., Shanahan, L., Worthman, C., & Costello, E.J. (2014). Childhood bullying involvement predicts low-grade systemic inflammation into adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 111 (21), 7570–7575. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1323641111 .

Cunningham, N.J., Taylor, M., Whitten, M.E., Hardesty, P.H., Eder, K., & DeLaney, N. (2010). The relationship between self‐perception of physical attractiveness and sexual bullying in early adolescence. Aggressive Behavior , 36 (5), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20354 .

de Arellano, M.A.R., Lyman, D.R., Jobe-Shields, L., George, P., Dougherty, R.H., Daniels, A.S., & Delphin-Rittmon, M.E. (2014). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services , 65 (5), 591–602. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300255 .

deLara, E.W. (2008). Developing a philosophy about bullying and sexual harassment: Cognitive coping strategies among high school students. Journal of School Violence , 7 (4), 72–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220801973862 .

deLara, E.W. (2012). Why adolescents don’t disclose incidents of bullying and harassment to adults. Journal of School Violence , 11 (4), 288–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.705931 .

deLara, E.W. (2016). Bullying scars: The impact of childhood bullying on adult life and relationships . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

DeVooght, K., Daily, S., Darling-Churchill, K., Temkin, D., Novak, M., & VanderVen, K. (2015). Bullies in the Block Area . www.ChildTrends.org

Eisenberg, M.E., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & Story, M. (2003). Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents. Archives of pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 157 (8), 733–738. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.157.8.733 .

Espelage, D.L., & De La Rue, L. (2012). School bullying: its nature and ecology. International. Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health , 24 (1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh.2012.002 .

Espelage, D.L., Hong, J.S., & Mebane, S. (2016). Recollections of childhood bullying and multiple forms of victimization: correlates with psychological functioning among college students. Social Psychology of Education , 19 (4), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9352-z .

Fosse, G.K., & Holen, A. (2006). Childhood maltreatment in adult female psychiatric outpatients with eating disorders. Eating Behaviors , 7 (4), 404–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.12.006 .

Gaynor, A.K. (1998). Analyzing problems in schools and school systems: A theoretical approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Gladden, R.M., Vivolo-Kantor, A.M., Hamburger, M.E., & Lumpkin, C.D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements . Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Gladstone, G.L., Parker, G.B., & Malhi, G.S. (2006). Do bullied children become anxious and depressed adults?: A cross-sectional investigation of the correlates of bullying and anxious depression. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 194 (3), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000202491.99719.c3 .

Greenwood, D.J., & Levin, M. (2006). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change, 2nd edn . New York, N. Y: Sage Publications.

Hawkes, N. (2015). Bullying in childhood may be linked to heart disease risk, study says. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online), 350.

Hill, C., & Kearl, H. (2011). Crossing the line: Sexual harassment at school . 1111 Sixteenth Street NW, Washington, DC20036: American Association of University Women.

Hofmann, S.G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I.J., Sawyer, A.T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research , 36 (5), 427–440.

Hoetger, L.A., Hazen, K.P., & Brank, E.M. (2015). All in the family: A retrospective study comparing sibling bullying and peer bullying. Journal of Family Violence , 30 (1), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9651-0 .

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpelä, M., Rantanen, P., & Rimpelä, A. (2000). Bullying at school—an indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence , 23 (6), 661–674. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0351 .

Knack, J.M., Jensen-Campbell, L.A., & Baum, A. (2011). Worse than sticks and stones? Bullying is associated with altered HPA axis functioning and poorer health. Brain and Cognition , 77 (2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2011.06.011 .

Kosciw, J.G., Greytak, E.A., Bartkiewicz, M.J., Boesen, M.J., & Palmer, N.A. (2012). The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools . 121 West 27th Street Suite 804, New York, NY 10001: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN).

Leary, M.R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 9 (2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221 .

Lehti, V., Sourander, A., Klomek, A., Niemela, S., Sillanmaki, Piha, J., & Almqvist, F. (2011). Childhood bullying as a predictor for becoming a teenage mother in Finland. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 20 (1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-010-0147-z .

McCabe, R.E., Antony, M.M., Summerfeldt, L.J., Liss, A., & Swinson, R.P. (2003). Preliminary examination of the relationship between anxiety disorders in adults and self-reported history of teasing or bullying experiences. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy , 32 (4), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070310005051 .

McDougall, P., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist , 70 (4), 300 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039174 .

Mishna, F., & Alaggia, R. (2005). Weighing the risks: A child’s decision to disclose peer victimization. Children & Schools , 27 (4), 217–226.

Mishna, F., Cook, C., Gadalla, T., Daciuk, J., & Solomon, S. (2010). Cyber bullying behaviors among middle and high school students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry , 80 (3), 362–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01040.x .

Newman, B.M., & Newman, P.R. (2015). Development through life: A psychosocial approach, 12th edn . Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Ouellet-Morin, I., Odgers, C.L., Danese, A., Bowes, L., Shakoor, S., Papadopoulos, A.S., & Arseneault, L. (2011). Blunted cortisol responses to stress signal social and behavioral problems among maltreated/bullied 12-year-old children. Biological Psychiatry , 70 (11), 1016–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.017 .

Patchin, J.W., & Hinduja, S. (2015). Measuring cyberbullying: Implications for research. Aggression and Violent Behavior , 23 , 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.013 .

Puhl, R.M., & Latner, J.D. (2007). Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s children. Psychological Bulletin , 133 (4), 557 https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557 .

Puhl, R.M., Peterson, J.L., & Luedicke, J. (2013). Weight-based victimization: Bullying experiences of weight loss treatment–seeking youth. Pediatrics , 131 (1), e1–e9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1106 .

Robers, S., Kemp, J., Rathbun, A., & Morgan, R.E. (2014). Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2013 (NCES 2014-042/NCJ 243299). Washington, D.C: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Rohner, R.P. (1975). They love me, they love me not: A worldwide study of the effects of parental acceptance and rejection. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press.

Rubin, A., & Babbie, E.R. (2008). Research methods for social work . Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Saldana, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers . 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shetgiri, R., Espelage, D.L., & Carroll, L. (2015). Practical strategies for clinical management of bullying . New York, NY: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Smith, P.K., & Sharp, S. (1994). School bullying: Insights and perspectives. . New York, N. Y: Routledge.

Strauss, J., & Corbin, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . 4th edn, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sweetingham, R., & Waller, G. (2008). Childhood experiences of being bullied and teased in the eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review , 16 , 401–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.839 .

Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry , 171 (7), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401 .

Ttofi, M.M., Farrington, D.P., Lösel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research , 3 (2), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/17596591111132873 .

Van der Kolk, B.A. (2003). Psychological trauma. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishers.

von Bertalaffy, L. (1968). General system theory: Foundations, development, applications (Revised Edition) . New York, NY: George Braziller, Inc.

Wade, TD., Keski‐Rahkonen, A., Hudson, JI. (2011). Epidemiology of eating disorders. In M.T. Tsuang, M. Tohen, P. Jones, (Eds.), Textbook of Psychiatric Epidemiology . (pp. 343–360). New York, N. Y: John Wiley & Sons.

Chapter Google Scholar

Wehrenberg, M., & Prinz, S. (2007). The anxious brain: The neurobiological basis of anxiety disorders and how to effectively treat them. . New York, N. Y: W.W. Norton & Company.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Social Work, White Hall, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, 13244, USA

Ellen W. deLara

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ellen W. deLara .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

deLara, E.W. Consequences of Childhood Bullying on Mental Health and Relationships for Young Adults. J Child Fam Stud 28 , 2379–2389 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1197-y

Download citation

Published : 18 July 2018

Issue Date : 01 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1197-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Eating disorders

- Relationship issues

- Adult development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Children (Basel)

- PMC10137246

A Multilevel Analysis of Factors Influencing School Bullying in 15-Year-Old Students

Yu-jiao wang.

1 School of Education Science, Liupanshui Normal University, Liupanshui 553004, China

2 Chinese Academy of Education Big Data, Qufu Normal University, Qufu 273100, China

Associated Data

The original data of the study can be found in the website https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

Background: School bullying causes serious impacts on adolescents’ physical and mental health. Few studies have explored the various factors influencing bullying by combining different levels of data. Methods: Based on the database of four Chinese provinces and cities of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018, this study used a multilevel analysis model that combined school-level variables and student-level variables to explore the influencing factors of students being bullied. Results: Students’ gender, grade repetition, truancy and arriving late for class, economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS), teacher support, and parent support had significant explanatory power on school bullying on the student-level; on the school-level, school discipline atmosphere and competitive atmosphere among students had significant impacts on school bullying. Conclusions: Boys, students who have repeated grades, truancy and arriving late for class, and students with lower ESCS suffer from more severe school bullying. When developing school bullying interventions, teachers and parents should pay more attention to those students and provide more emotional support and encouragement to them. Meanwhile, students in schools with a lower discipline atmosphere and a higher level of competitive atmosphere experience greater levels of bullying, and schools should create more positive and friendly environments to prevent bullying events.

1. Introduction

In the 1980s, a young Norwegian boy committed suicide after suffering school bullying; since then, school bullying has begun to enter the field of researchers and has become an important research topic [ 1 ]. Nowadays, it is receiving more and more attention from many international organizations. Among the research topics related to school bullying, the primary focuses include the following: What characteristics cause individuals to be more likely to suffer from school bullying? Why are individuals with these characteristics easily bullied by others? What are the factors that cause bullying in schools? These issues have always been topics of great concern to researchers both nationally and worldwide.

Previous studies have shown that various types of factors affect students’ exposure to bullying, including individual characteristics, schools, and families [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Ruan examined the influencing factors of student suffering from school bullying through factor analysis and logistic regression [ 2 ]. The results showed that, from the cross-sectional dimension analysis, the ranking of factors was as follows: students’ individual characteristics, schools’ background features, and emotional support.

From a logistic regression of the longitudinal section, among the students’ background characteristics, boys were more likely to suffer from school bullying than girls; senior students were more likely to suffer from bullying than those in lower grades; and students with lower academic performance scores were more likely to suffer from school bullying than those with higher scores [ 2 ]. However, some studies have found different results. Regarding age, for example, Rigby and Slee found that younger children were more likely to experience bullying than older children [ 8 ]. With age increase, bullying tended to stop; the reason for this may be because individuals acquire more social skills that improve self-esteem [ 9 ].

In terms of school background characteristics, Ruan’s analysis showed that, compared with urban schools, students in rural schools suffered more school bullying; students in private schools suffered more school bullying than those in public schools; the more repeating students on a campus, the higher the proportion of school bullying, and the better the school discipline atmosphere, the fewer the bullying incidents [ 2 ]. Lastly, the class size, school size, and teacher–student ratio of a school’s background characteristics had no significant impact on students’ school bullying [ 2 ]. Contrary to Ruan’s results, however, Huang’s study found that school location (urban or rural) and school type (public or private) had no effect on students’ school bullying [ 5 ].

In addition, teacher support plays a very important role in school background characteristics. Effective teacher support greatly reduces the occurrence of school bullying, but if teachers treat students unfairly, it may increase the occurrence [ 5 ]. Regarding the home environments of school bullies and victims, children who perpetrated bullying reported that their parents did not exercise caring and supervisory functions, sometimes even neglecting them [ 7 ]. This is in contrast to the home environments of bullying victims, who had very close relationships with their parents and were, therefore, vulnerable to overprotection. In addition, Fu et al. pointed out that students from families with lower socioeconomic statuses were more likely to be victims of more severe types of bullying, as school is an integral indicator of social stratification [ 10 ]. Parental emotional support was an important family factor affecting students’ suffering from school bullying, and insufficient parental emotional support was an important reason why many young people suffered from school bullying and could not cope effectively [ 5 ].

In conclusion, it can be seen that school bullying is affected by various factors of individuals, families, and schools, but there have been some contradictions among past studies, such as age and school type, which may be related to sampling or research methods. In addition, few studies have explored the various factors influencing bullying by combining different levels of data. When discussing this topic, these influencing factors should be considered comprehensively, but different levels cannot be analyzed at the same level, which leads to analytical bias. When facing these data from different sources, a multilevel analysis method should be used for an accurate analysis.

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which was first implemented by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2000, added a survey of students’ experiences of bullying in schools for the first time in 2015, including three types of bullying: relational bullying, verbal bullying, or physical bullying. In 2018, PISA continued to conduct a school-bullying survey in 75 countries and regions, showing the close concern that educators around the world have toward the problem. School bullying should be a high-priority concern for education policy makers and school administrators. Moreover, the PISA data includes those from both the students and the schools, which meets the requirements of multi-level analysis.

Therefore, based on the survey data of PISA 2018, our study used a multilevel analysis model and combines school-level and student-level variables to jointly explore various factors affecting school bullying and reveal the specific causes behind this phenomenon. Individual level variables included school bullying (including total school bullying, relational bullying, verbal bullying, and physical bullying), students’ gender, grade, education type, grade repetition, truancy and arriving late for class, family economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS), teacher support, and parent support they perceived, some of which were discussed above. School level variables included the describing characteristics of schools, such as school location, school type, school size, or school atmosphere, etc. The purpose of this paper is to investigate whether these factors have impacts on students’ bullying and what the effect of the impact is.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. materials.

The data for this study came from the PISA 2018 survey database of four provinces and cities in mainland China (Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang). First, we downloaded the 2018 global Student questionnaire data file and School questionnaire data file from the PISA website https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/ (accessed on 15 October 2021). For a brief introduction to PISA and descriptions of the questionnaires, see Appendix A . Then, we selected the data for mainland China. The student questionnaire data of mainland China includes 12,058 middle school students aged 15 (from 15 years and 3 months to 16 years and 2 months), and the school questionnaire data includes 361 schools. Finally, after deleting samples with missing data and those unable to meet the statistical criteria, the sample size of this study was 11,497 students from 334 schools (see Appendix A for detailed standards and procedures).

2.2. Research Variables

The variables of our study included individual-level variables of students and environment-level variables of school.

The student-level variables included the following: suffering from school bullying (including total school bullying, relational bullying, verbal bullying, and physical bullying), which was the outcome variable of the study; gender, grade, education type, grade repetition, truancy and arriving late for class, family economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS, teacher support, and parent support, which were predictor variables.

The school-level variables were divided into two categories. One was variables derived from the group level describing the characteristics of the schools, including school location, school type, school size, class size, student–teacher ratio, proportion of boys, proportion of special needs students, proportion of students without graduation certificates, student behaviors that hindered learning, and teacher behaviors that hindered learning. All of the above variables were completed by the principal (or principal representative) of each school. The other type was variables based on shared constructs, in which group characteristics were derived from combinations of group members and contained the attitudes, perceptions, or behaviors of group members. The variables were taken from student questionnaires, but they were aggregated by group, averaged, and then integrated into group variables, including school discipline atmosphere, competitive atmosphere among students, and cooperative atmosphere among students. See Appendix B for question descriptions, original corresponding items, and coding of these variables. Descriptive statistics of the above variables are shown in Table 1 .

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

1 For categorical variables, the Average refers to the percentage of the latter category in each variable. For example, for Gender, 0.521 represents that the proportion of male students is 52.1%; for Grade repetition, 0.063 represents that the proportion of students’ repeating grade is 6.3%; and for School type, 0.140 represents that the proportion of private schools is 14%. Other categorical variables are similarly interpreted.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

The statistical software packages used in this study were SPSS 24 and HLM 6.08. The statistical methods included reliability and validity tests, a regression analysis, and a multilevel model analysis.

In many social science research fields, such as psychology, education, and management, data are often in nested structures (nested data, multilayer data, or multilevel data) where, for example, students are nested under a class, and the class is under the school. The sample data from such nested structures are generally not independent, which violates traditional statistical assumptions (residual independence and a homogeneous regression slope). Using a traditional OLS regression method to analyze nested samples and, thus, ignoring the problem of hierarchical differences can bring about statistical estimation bias. If the conclusions obtained from a high-level data analysis are inferred with lower-level data, it is easy to overestimate the lower-level conclusions, resulting in “ecological fallacy”. Conversely, if the conclusions obtained from a lower-level data analysis are inferred with higher-level data, this leads to “atomistic fallacy” [ 11 ]. Therefore, it is very important to understand the variation caused by different groups using a multilevel analysis method.

An analysis for nested data has been gradually developed, and finally in the 1990s, a complete and systematic theory and method was developed, namely the multilevel model analysis or multilevel analysis (HLM); in addition, HLM software was designed for multilevel analyses. Using the multilevel analysis method enables the analysis of multilevel data in one model at the same time, reducing the statistical errors mentioned above, and it can analyze the possible interactions between different levels’ data, describing the characteristics of a phenomenon more objectively. In this study, using HLM software, we combined school-level variables and student-level variables to explore the influencing factors that affected school bullying and attempted to reveal the specific causes behind this phenomenon.

A structure diagram of this study is shown in Figure 1 .

The structure of the study.

As suggested by Bryk and Raudenbush [ 12 ], a multilevel analysis should include the implementation of four sub-models: Null Model, Random Coefficient Model, Intercepts as Outcomes Model, and Slopes as Outcomes Model. Since our study did not specifically explore the moderating effects of the school-level contextual variable group, Slopes as Outcomes Model was not performed. Therefore, this study analyzed three multilevel models (see Table 2 for total school bullying): Model I (Null Model) was used to test the proportion of group variation to the overall variance in student suffering from school bullying and to three different types of bullying (that is, the contextual effect between different schools), which provided a reasonable basis for a subsequent multilevel analysis to confirm the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of the dependent variable, and the between-group variation component could meet the requirements for performing a multilevel model analysis. Model II (Random Coefficient Model) was used to test the direct impacts of student-level variables on school bullying. Model III (Intercepts as Outcomes Model) was used for testing the direct impacts of school-level variables on school bullying. Model III was the full model for this study.

Multilevel analysis results of the influencing factors of students suffering from school bullying.

3.1. Model I: Null Model

No explanatory variables were included in the Null Model; instead, it only contained the result variables, and the corresponding formula is shown in Appendix C .

As shown in the results of Table 2 , the between-group variation component (τ 00 ) of suffering from school bullying was significantly different from 0 (χ 2 = 444.065, p < 0.001), indicating that the degree of student suffering from school bullying in the same school was similar, but there were significant differences in different schools. Similarly, as shown in Table A1 , Table A2 and Table A3 (these three tables can be seen in Appendix C ), the between-group variance components (τ 00 ) of relational bullying (χ 2 = 409.931, p = 0.003), verbal bullying (χ 2 = 387.921, p = 0.020), and physical bullying (χ 2 = 470.758, p < 0.001) were also significantly different from 0. These results illustrate that the variation between groups could not be ignored. In order to avoid biased interpretation of the results, it was necessary to use the multilevel model for data analysis.

3.2. Model II: Random Coefficient Model

In this model, the student-level variables are not uncentered, with the exception of grades, teacher support, and parent support, which were generally grand-centered. Kreft pointed out that categorical variables must not be mean centered [ 13 ]. If a continuous variable is meaningful for 0, it does not need to be centered because, whether it is centered or not, it has no effect on the estimated value and significance but only affects the interpretation of the results. To make an interpretation meaningful, it needed to be mean-centered in both Level 1 (student-level) and Level 2 (school-level) and always use grand-centered variables which is equivalent to the original data, while group-centered variables are not equivalent to the original data [ 13 ]. The corresponding formula is shown in Appendix C .

From the results in Table 2 , it can be seen that, in addition to grade and education type, gender, grade repetition, and truancy and arriving late for class at the individual level all had significant positive explanatory powers on students’ total school bullying. Both teacher support and parent support have significant negative explanatory powers on students’ total school bullying.

Similarly, relational bullying, verbal bullying, and physical bullying showed the same effects, as shown in Table A1 , Table A2 and Table A3 (these three tables can be seen in Appendix C ). When teacher support increased by 1, total school bullying decreased by 0.562, relational bullying decreased by 0.195, verbal bullying decreased by 0.180, and physical bullying decreased by 0.188. When parent support increased by 1, total school bullying decreased by 0.391, relational bullying decreased by 0.142, verbal bullying decreased by 0.133, and physical bullying decreased by 0.117. Lastly, ESCS only had a significant negative explanatory power on students suffering from total school bullying and physical bullying but had no significant effect on relational bullying and verbal bullying. When family ESCS increased by 1, total school bullying decreased by 0.066, and physical bullying decreased by 0.042.

The above results indicate that boys suffered from a greater degree of school bullying than girls (including total school bullying and three types of bullying), and students who repeated grades, were truant, and arrived late in the past two weeks were more severely bullied than those who had not. The lower the student family ESCS is, the higher the levels of school bullying and physical bullying are. The lower students perceived teacher support and parent support, the more severe the school bullying.

3.3. Model III: Intercepts as Outcomes Model

In this model, with the exception of the variables of school location, school type, proportion of special needs students, and proportion of students without graduation certificates being uncentered, all the other variables were grand-centered.

The results in Table 2 and Table A1 , Table A2 and Table A3 (these three tables can be seen in Appendix C ) show that only the two variables of school discipline atmosphere and competitive atmosphere among students had a significant impact on student suffering from total school bullying and three other types of bullying. The variable of school discipline atmosphere had a significant negative explanatory power on the degree of student suffering from bullying, while the variable of competitive atmosphere among students had a significant positive explanatory power on the degree of student suffering from bullying. The analysis results of Model III show that, when the school discipline atmosphere increased by 1, school bullying decreased by 0.572, relational bullying decreased by 0.198, verbal bullying decreased by 0.143, and physical bullying decreased by 0.231. However, when the variable of competitive atmosphere among students increased by 1, school bullying increased by 0.806, relational bullying increased by 0.263, verbal bullying increased by 0.289, and physical bullying increased by 0.245.

These results indicate that the worse a school’s discipline atmosphere is, the more severe the level of school bullying students experienced is, i.e., students in schools with poor discipline atmospheres experienced a greater degree of school bullying than those in schools with better discipline atmospheres. However, the higher the competitive atmosphere among students is, the higher the level of school bullying students experienced is, i.e., students in schools with high inter-student competition atmospheres experienced greater levels of bullying than those in schools with low inter-student competition atmospheres.

The remaining variables of school background characteristics all did not have significant impacts on students’ suffering from school bullying or the three other types of bullying.

4. Discussion

4.1. influence of student-level variables on students being bullied.

According to the results in Model II, in addition to grade and education type, the student-level variables of gender, grade repetition, and truancy and arriving late for class all have significant positive effects on total school bullying and the three types of bullying, while teacher support and parents’ support both have significant negative explanatory power on students’ total school bullying and the three types of bullying. ESCS only negatively affects students’ total school bullying and physical bullying but not relational bullying and verbal bullying. The results above show that boys suffer from a greater degree of school bullying than girls, and students who have repeated grades, who are truant, and who have been late for class in the past two weeks are more severely bullied than those who have not. The lower the family’s ESCS is, the higher the level of total school bullying and physical bullying are. The lower the perceived teacher support and parents support are, the more severe the school bullying is. The above results are discussed further below.

First, in our study, we found that boys suffered more severe bullying than girls, both for total school bullying and for the three different types of bullying, which is partly consistent with previous studies. Previous studies have confirmed that boys are at greater risk of school bullying than girls [ 8 , 14 ]. In terms of different types of bullying, previous studies have found that girls are more susceptible to relational bullying [ 15 ], and data from OECD countries also show that girls are more likely to be exposed to “spreading rumors by other students” [ 16 ], while boys are more likely to suffer from physical bullying [ 17 ]. Based on the data analysis of PISA 2015, Huang found that boys were more prone to physical bullying than girls [ 5 ], such as physical hitting or pushing. In addition, boys were also more likely to experience verbal bullying than girls, such as being teased by others. In summary, boys are at greater risk of bullying than girls. The reason for this may be that boys are more prone to agitation and conflict than girls, which makes boys significantly more likely than girls to be bullied or to bully others. Therefore, we should pay more attention to the male group and give them more help related to the phenomenon of bullying.

Second, our study found that students who repeated grades, had absenteeism, and were late to class within the last two weeks were more likely to be bullied at school. In addition to poor academic performance, repeat-grade students may also have difficulties with the development of social and emotional skills. When these older students study and live with new, younger classmates, they may be very easily discriminated against, laughed at, or teased by other students and may even be socially excluded [ 18 ], which may, in turn, lead to bullying incidents [ 19 ]; this is similar for students with absenteeism and lateness. According to previous studies, disciplinary violations such as those for truancy, skipping class, and lateness may be external manifestations of students rejecting learning. If students are unwilling to enter a classroom, or even skip class, it is naturally difficult for them to achieve good academic performances [ 20 ], while students with poor academic performances are more likely to be bullied, which has been confirmed by previous research [ 10 , 21 ]. On the other hand, those who are bullied protect themselves by avoiding school or being truant, and then these truant students have more difficulties keeping up with teaching or are unable to obtain help from the school due to not showing up to school on time. This also weakens the connection between students and the school environment, leading to poor academic achievement [ 22 , 23 ]. Therefore, there may be a mutual causal relationship between truancy, absenteeism, lateness, and other disciplinary violations and students being bullied on campus. To reduce bullying on campus, educators can start with the strict management of students’ disciplinary violations to ensure that students can attend school on time because this is a premise to ensure quality of learning. In this way, it is possible to improve their academic achievements and help them establish a close relationship with the school, making it easier to seek help from teachers and classmates, which is conducive to reducing the occurrence of bullying.

Furthermore, the results show that students’ ESCS had a significant negative impact on students’ total school bullying and physical bullying, which meant that the lower a student’s family economic sociocultural status is, the higher the degrees of overall school and physical bullying is. This result is consistent with the results of Huang and Zhao [ 23 ], as well as empirical research from the Netherlands, which showed that adolescents with lower social status had a higher proportion of physical and psychological symptoms, which were more likely to be aggression by peers [ 24 ]. Therefore, schools and teachers should pay more attention to students from disadvantaged backgrounds and carry out targeted psychological counseling and assistance to reduce the risk of bullying for these students.

Finally, this study found that the higher the levels of teacher support and parent support perceived by students are, the lower the level of suffered school bullying is. A close parent–child relationship can help students obtain more help when they suffer from school bullying, and parents who care about and support their children emotionally can not only help their children decrease school bullying but can also relieve children’s psychological pressure and pain after students are bullied [ 25 ]. In terms of teacher–student relationships, teachers’ actions of supporting, caring about students’ academic progress, and expecting students’ success make students feel accepted, respected, and cared for. On the one hand, students can better seek help from teachers; on the other hand, closeness and harmony of teacher–student relationships greatly reduces the chance of negative interpersonal behaviors, such as bullying [ 26 ]. Thus, both families and schools are key forces to fight against school bullying, and home–school cooperation can better build antibullying barriers in students’ lives and learning.

In conclusion, when developing school bullying interventions, more attention should be paid to male students, students who repeat grades, are late, or are absent from class, and students with lower ESCS. For example, physical bullying of male students should be paid concern. Pushing, beating, and other similar behaviors should be stopped in time. As for students with low academic performance, parents should encourage and support their children rather than criticize and blame them. Teachers should also pay more attention to students who are often late, absent, or from lower backgrounds and should strengthen their ability to recognize bullying incidents, especially the two types of relationship bullying and verbal bullying, because they will not cause obvious physical harm, making it very difficult to identify. In addition, teachers can pay close attention to the way students make friends and interact with each other. They can observe whether a particular student is excluded or isolated in group activities, PE class, and after class. Once they find signs of bullying, appropriate treatment should be provided the first time to prevent the occurrence of the event. Finally, teachers should consult more professional counselors, attend seminars on school bullying cases, and flexibly use effective ways to deal with bullying cases to reduce the harm caused by bullying.

4.2. Influence of School-Level Variables on Students Being Bullied

The results of Model III show that only the school discipline atmosphere and the competitive atmosphere among students of the school environment level variables have significant impacts on the total school bullying and the three types of bullying. School discipline atmosphere has a significant negative explanatory power on school bullying, while the competitive atmosphere among students has a significant positive explanatory power on students being bullied, indicating that students in schools with a worse discipline atmosphere experience greater levels of bullying than students in schools with a better one; students in schools with a high level of inter-student competition are more likely to experience higher levels of school bullying than those in schools with a lower level. A good school discipline atmosphere helps protect students and make them less vulnerable to school bullying [ 23 ], but the competitive atmosphere among students may make some students feel jealous or hate other classmates, which in turn increases the chances of students being bullied at school.

First, the negative correlation between school disciplinary atmosphere and students suffering from bullying has been confirmed by some studies [ 2 , 18 , 27 ]. A good school discipline atmosphere helps to protect students and make them less vulnerable to school bullying [ 23 ]. The reason for this may be because when students learn and interact in a well-ordered environment, they are often more willing to engage in it because they feel safe, and the trigger factors for student aggressive behavior are greatly reduced [ 28 ]. Therefore, when formulating plans to prevent school bullying at the school level, more consideration should be given to the important role of school disciplinary atmosphere, which is not only an invisible school culture but also can be reflected in the implementation of school rules and discipline. In addition, this is also consistent with strengthening the management of skipping class, truancy, lateness, and other disciplinary violations mentioned above.

Second, atmospheres of competition and cooperation among students in schools are important aspects of the school climate [ 29 ]. This is the first time that this topic has appeared in the PISA questionnaire survey. The results show that competitive atmosphere had a significant positive explanation for the degree of school bullying. However, cooperative atmosphere did not have a significant impact on student suffering from school bullying. This is an interesting result, suggesting that competitive and cooperative atmospheres at the school level may not be two opposing aspects, and they may have their own working principles.

The positive association between perceived competitive atmosphere and school bullying has been supported by some studies. Volk proposed that a competitive atmosphere may make some students feel jealous or hateful toward other classmates, which in turn increases the chances of students being bullied at school [ 30 ]. Wang’s research showed that both academic competition and social competition perceived by primary and secondary school students were significantly positively correlated with school bullying [ 31 ]. In another research project, Wang proposed that a vicious, competitive atmosphere formed among students not only led to campus bullying [ 32 ] but also generated countless indifferent bystanders who saw the campus bullying but were unwilling to lend a helping hand. Therefore, when intervening in bullying in schools, students should be consciously guided to engage in positive and benign competition and to avoid vicious competition. In this way, good peer relationships in the school environment form, and the occurrence of bullying is reduced.

Finally, a surprising result in our study is that student behaviors and teacher behaviors that hinder learning in schools both had no effect on students’ experiences of school bullying. A previous study regarded these two variables as a measure of school spirit [ 33 ]. Through a multilevel analysis based on PISA 2015 data from four provinces and cities in China, the study found that student and teacher behaviors that hindered learning had significant negative impacts on students’ scientific literacy without controlling for student and school ESCS values; however, when controlling for them, the effects were smaller and no longer significant. Due to the large number of control variables involved in our study and different combinations of control variables producing various different results, this part may therefore need to be further explored in future studies.

Here are some suggestions on the results. Students spend a lot of time in school. As an important place of education, school plays a decisive role in the formation of students’ personality and behavior. When the school atmosphere is positive and friendly, bullying can be reduced. Schools should instruct students to learn ways to protect themselves, identify bullying in schools, and seek help from teachers and classmates to better protect themselves. Schools should strengthen the moral education of students and cultivate students’ good sense of justice and moral sense, making students brave enough to stop school bullying or report bullying to teachers.

The psychological counseling institution of schools should play an active role in school bullying and treat every bullying case as a major campus crisis. In addition to isolation, placement, and counseling, it is important to continuously observe and follow up the development of physical and mental status of the cases, both of the perpetrator and the victim, making sure they are physically and mentally healthy. In addition, schools should strengthen students’ interpersonal communication and life education. Students must learn to respect each other’s lives and cherish their own. They must understand that certain behaviors should not be allowed, such as making fun of each other’s sexual orientation and physical characteristics. It must be made clear that students’ bullying behavior may directly or indirectly kill their classmates. When students are aware that bullying can have such serious consequences, it may be effective in reducing the incidence of school bullying.

At last, bullying should not be seen as a problem of a few but as one of society’s problems. The whole society should work together to create a friendly campus environment. Education authorities should integrate schools, neighboring communities, police and government organs, social welfare organizations, mental health units and other relevant social resources, and professional assistance to provide students with the most appropriate treatment. In order to prevent bullying, teachers and schools are encouraged to make more use of social resources. A variety of professional teams, including school principals, directors, tutors, psychological consultants, students, parents, juvenile police officers, social workers of welfare organizations, and other experts should work together to investigate, evaluate, and formulate counselling programs to effectively reduce bullying incidents in schools.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Because the selected variables were all obtained from the PISA test and were limited by the scope of the database, our study may not contain all the factors that affect students’ experiences of school bullying. In follow-up research, other methods, such as using other databases or questionnaires made by the researchers themselves, should be used to include more influence factors to analyze this topic. In addition, some factors in our study were not obviously related to school bullying, such as grade and education type of student-level, student behaviors and teacher behaviors that hindered learning, and cooperative atmosphere among students of school-level, so more rigorous field investigations may be needed [ 34 ].

Furthermore, regarding the multilevel analysis model, the analysis method of a multi-level mediation model can also be considered to further elaborate the specific operation paths of these influencing factors [ 35 ]. A multilevel mediation model can set the possible influence paths for factors that were found to have significant explanatory power based on the existing research so that all the independent variables can be included in the model at one time. It can provide more specific reference information for educational administrators and can broaden the scope of related research topics, providing more theoretical significance.

5. Conclusions

Based on the PISA 2018 survey data (including student data and school data) and using a multilevel analysis model, this study explored the impacting factors that affected school bullying. While the results are consistent with some previous studies, there are some new developments.

In the student-level variables, boys, students who have repeated grades, who are truant, and who have been late for the class in the past two weeks, and students whose economic, social, and cultural status is lower suffer from more severe school bullying. Furthermore, students who have perceived lower teacher support and parents support are more severely bullied than those who have not. Thus, when developing school bullying interventions, more attention should be paid to these students. Teachers and parents should give more emotional support to them. Additionally, school administrators, consulting teachers, and other relevant personnel should pay more attention to students. Once they find signs of bullying, appropriate treatment should be provided the first time to prevent the occurrence of the event.

In the school-level variables, students in schools with a worse discipline atmosphere and a higher level of inter-student competitive atmosphere experience greater levels of bullying. Therefore, when formulating plans to prevent school bullying at the school level, more consideration should be given to the important role of strengthening school disciplinary atmosphere and reducing the competitive atmosphere. A safe, well-ordered, positive, and friendly school environment helps protect students and make them less vulnerable to school bullying, and the establishment of such a campus environment needs the efforts of the whole society.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the open access data provided by the PISA tests administered by OECD. We would also like to take this opportunity to express heartfelt gratitude to three anonymous reviewers for their positive suggestions and constructive comments which were very helpful in making appropriate corrections and modifications. Additionally, we appreciate the time and detail provided by each editor.

Appendix A.1. The Introduction to PISA and Descriptions of Student and School Questionnaires

The data materials of this study come from the PISA 2018 survey database. The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), implemented by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), mainly tests the levels of reading, math, and science of 15-year-old middle school students to evaluate the degree of their knowledge and skills which are necessary to fully participate in modern social and economic life. This assessment not only confirms whether students can replicate knowledge but also the extent to which they can extrapolate from what they have learned and apply it to unfamiliar situations in and outside of school, i.e., their abilities to use these knowledge and skills to deal with real-life challenges.

The first PISA test was conducted in 2000 and has been conducted every three years. In each round of PISA, students are tested in detail in one of the three core school subjects of reading, math, and science. According to this schedule, a comprehensive performance analysis is conducted every nine years for each of the three core themes. The latest data are the seventh assessment of 2018, which should be conducted in 2021, but because of the influence of COVID-19, “OECD member countries and Associates decided to postpone the PISA 2021 assessment to 2022 and the PISA 2024 assessment to 2025 to reflect post-COVID difficulties ( https://www.oecd.org/pisa ) (accessed on 15 October 2021)”. Due to the time of the implementation process, the most recent data available for analysis are still from 2018.

In addition to the tests in reading, math, and science, students also fill in a background questionnaire that collects their family background and school information, including their attitudes, personalities, and beliefs and their family, school, and learning experiences. Many issues of public concern have also been added to the survey of this project in recent years. In 2015, the survey of school bullying was added to the questionnaire. In 2018, the school bullying survey was continued, and attitudes towards school bullying was added.

Furthermore, the students’ parents, teachers, and school principals or leaders they studied are also included in the program. The school principal or leader completed a questionnaire covering the school’s management, organization, and learning environment. Therefore, the content of PISA is very broad. Since its first implementation in 2000, it has attracted the participation of more than 90 countries. A total of more than 3 million students worldwide have participated in the program which has very comprehensive educational data of students worldwide.

Appendix A.2. The Procedure of Data Collection

The PISA 2018 data comes from 75 countries and economies around the world and is aimed at 15-year-old students in grade 7 and above in educational institutions. The sampling design used for the PISA assessment is a two-stage stratified sample design.

The sampling unit of the first stage is schools with 15-year-old students. Schools were sampled systematically from a comprehensive national list of all PISA-eligible, known as the school sampling frame. This type of sampling is known as systematic probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling. Prior to their selection, schools in the sampling frame were assigned to mutually exclusive groups based on school characteristics called explicit strata. These methods were developed to improve the accuracy of sample-based estimates.

The sampling unit of the second stage is students in the sampled schools. Once schools have been selected for the sample, a full list of 15-year-olds from each school sampled will be prepared. Each country/economy participating in computer-based assessment (CBA) and Global Competency (GC) must set a target cluster size (TCS) of 42 students. Countries/economies participating in the paper-based assessment (PBA) and CBA countries/economies without GC set a TCS of 35. For lists with fewer than the target number of students, all students on the list were selected.

At least 150 schools are selected from each country, but if a participating country has fewer than 150 schools, then all schools were selected to participate. In each participating school, a predetermined number of students—the target cluster size defined earlier—were randomly selected with the same probability. In schools with a small number of students matching the target cluster size, all students are selected. Overall, a minimum of 6300 students will be required for computer-based countries and 5250 students for paper-based countries and computer-based countries.

Appendix A.3. The Statistical Criteria and Procedure of Deleting Data

In order to meet the criteria of multi-level analysis, the following two steps were carried out for the data used:

Firstly, to conduct multi-level model analysis on data, at least two levels of variables should be included, and our study contains two categories of variables: individual-level variables of students and environment-level variables of school. Different researchers proposed different sample number requirements for the variable analysis of two levels. Kreft proposed the 30/30 rule; that is, there should be at least 30 groups, and each group should have at least 30 subjects or observed values [ 36 ]. Hox suggested that there should be a minimum ratio of 50/20 as to test cross-layer interactions [ 37 ], i.e., there should be at least 50 groups with at least 20 subjects or observations in each group, and the minimum ratio of random effects is 100/10; that is, there should be at least 100 groups with at least 10 subjects or observations in each group. There are 361 groups (361 schools) in our study, most of which have about 35 students, meeting the above criteria. Then, in order to make the analysis criteria, the groups with less than 30 students (that is, the number of students in each school) are deleted (school numbers: 97500019, 97500024, 97500027, 97500074, 97500077, 97500094, 97500118, 97500147, 97500165, 97500168, 97500186, 97500204, 97500217, 97500220, 97500249, 97500253, 97500273, 97500274, 97500275, 97500280, 97500332).

Secondly, the variables of the school-level used in the study are classified into two categories [ 38 ]. One is variables based on Global Constructs, which are derived from the group levels and describe group features, such as the location and scale of the school. The other is variables based on Shared Constructs, of which group features are derived from the group members. The attitudes, perceptions, or behaviors of the group members are summarized and averaged based on groups and then integrated into group variables, such as the school discipline atmosphere perceived by the students. According to Zohar [ 39 ], in order to integrate variables at a lower level into variables at a higher level, the interrater agreement indicator Rwg(j) must be greater than 0.7, and the higher Rwg(j) is, the more appropriate it is. Therefore, after calculating the Rwg(j) of each group of each variable at the school level, delete the group with Rwg(j) less than 0.7 (school numbers: 97500043, 97500360, 97500361, 97500362). Then delete the group with missing values (school number: 975000299) (in the analysis of multilevel analysis, Level 1 is allowed to have missing values, but Level 2 cannot). Finally, a total of 11,497 student-level data and 334 school-level data were included in the final data analysis.

The code for calculating Rwg is as follows:

Appendix B.1. Outcome Variables (Y)

The outcome variables of this study are students “suffering from school bullying”, “suffering from relational bullying”, “suffering from verbal bullying”, and “suffering from physical bullying”, which are student-level variables. The PISA 2018 background questionnaire surveyed students’ experiences of bullying-related behaviors in school and measured three different types of bullying: physical bullying, relational bullying, and verbal bullying [ 40 ]. PISA 2018 asked students “During the past 12 months, how often have you had the following experiences in school? (Some experiences can also happen in social media.):

- “Other students left me out of things on purpose.” (Relational bullying),

- “Other students made fun of me.” (Verbal bullying),

- “I was threatened by other students.” (Verbal bullying),

- “Other students took away or destroyed things that belonged to me.” (Physical bullying),

- “I got hit or pushed around by other students. “ (Physical bullying),

- “Other students spread nasty rumors about me.” (Relational bullying).

If a student chooses “Never or almost never” they receive 1 score, “A few times a year” receives 2 scores, “A few times a month” receives 3 scores, and “once a week or more” receives 4 scores. Add up the scores of six items to obtain the “suffering from school bullying” variable. The score ranges from 6 to 24 scores. Similarly, add the scores of questions 1 and 6, the scores of questions 2 and 3, and the scores of questions 4 and 5, respectively, to obtain the variables of relational bullying, verbal bullying, and physical bullying. The higher the scores are, the more serious the bullying is.

Since there is not necessarily a high correlation between the six measurement items of school bullying (for example, students may be suffering from relational bullying but not physical bullying), the measurement of school bullying should be a Formative Indicator. There is still no comprehensive way to test the reliability and validity of the formative indicators now, but most scholars believe that there should not be serious multi-collinearity problems among the combined indicators, which will reduce the reliability and validity of the measurement model [ 41 , 42 ]. Based on this, we carried out the multi-collinearity test of these six items. The result showed that the VIF values reflecting the severity of the collinearity problem were between 1.552 and 2.041, which met the standard of less than 3.3, indicating that there was no multi-collinearity problem among the 6 items. It means that the reliability and validity can be guaranteed. Similarly, the VIF values of relational bullying, verbal bullying, and physical bullying were 1.484, 1.203, and 1.270, respectively, none of which was greater than 3.3, indicating that there were no multicollinearity problems for the items in these 3 different types of bullying variables. Additionally, the reliability and validity can be guaranteed.

Appendix B.2. Predictor Variables (X)

The predictors at the student-level of students are as follows:

- Gender. In this study, gender is a binary dummy variable, female = 0, male = 1. Studies found that the number of male students who suffered from school bullying was significantly higher than that of female students [ 8 , 14 ], so gender is an important factor that affects a student’s suffering from school bullying.

- Grade (continuous variable). Students are all in grades 7 to 12. Research showed that the amount of school bullying decreases with the grades increasing [ 8 , 9 , 43 ].

- Education Type (two-category dummy variable), general education = 0, vocational education = 1;

- Grade repetition (two-category dummy variable), no grade repetition = 0, grade repetition = 1;

- Truancy (two-category dummy variable), no truancy = 0, truancy = 1;

- Arriving late for class (two-category dummy variable), no lateness = 0, lateness = 1;