The Human Person: Nature, Ethical and Theological Viewpoints

Philosophical meaning of Person . The Person as a living concrete reality: its origin and constitutive elements. Logical, ethical and social consequences. Theological implications .

————————

The concept of Person needs to be clearly established by philosophical considerations that go farther than the merely measurable parameters of the physical sciences. We use the term in everyday life and we seem to be clear about its meaning, even if we do not define it explicitly: a person is not a thing in the wide sense that includes mostly inanimate objects, but a living reality, thus implying a source of activity that is self-originated and that shows a spontaneity not found in the physical laws by themselves.

But this is just the first step. Nobody thinks of microbes, insects, fish or even other larger and marvelous living things as persons. While there is a common tendency to describe some animals –mostly in mythological or poetic terms- as fictional characters speaking and acting as we do, we do not take this seriously, except –perhaps- when regarding house pets or primates as basically so similar to ourselves that we uncritically attribute to them our own vices and virtues.

In our experience and common language we encounter persons, and describe them as such, only when we consider human beings. Something new is present in the way Man acts that is the common root of self-appreciation, culture (both in the sciences, the humanities, the different religions) and of the structure of society at all levels. This basic and universal root we call human rationality and thus we define Man as a Rational Animal .

A Person is thus defined by an activity in which ends are freely sought after being known as concepts (containing information that goes past the data of the senses), and valued as good. Rationality is expressed and realized in the search for Truth, Beauty and Goodness, a multiple activity that corresponds to the two powers of the human spirit: intelligence and free will, to know and to love. Knowledge in this case is not a mere reaction to an external stimulus (this is the first source of our acquaintance with the world, through sense impressions), but a process where the data are consciously analyzed to obtain ideas of universal value, and inferences or deductions that apply to them well beyond the direct experience.The person is conscious of multiple possibilities, both of representing reality and of acting, and looks for the best explanation of facts and for the consequences of various courses of action, either as ends in themselves or as means to other ends. This leads to value judgments that embody purpose and free choice . Thus we apply to the person’s activity the categories of truth-error and of suitability and “goodness” that presuppose ends and means in acordance with the nature of things.

The philosophical concept of nature expresses the essence of a given reality in so far as it is the sufficient reason for its activities: acting should be tied to what the agent is. This is applied in science when we define matter –at any level- precisely by its form of interacting with other matter, including our laboratory instruments. An unnatural behavior has the connotation of error, it is something wrong and inappropriate, that is never found in the simple processes of the inanimate world, but that can be due -in the case of a person- to a free decision. In such a case we speak of right and wrong, the basis or moral judgments and of the concepts of rights and duties both at the personal level and also in the context of society.

Only Man, in our known Universe, has the power to know and choose in this way. While animals exhibit wonderful behavior, their acting cannot be attributed to a free choice arising from the conscious and free selection of alternative paths. A genetic program, coupled with conditioned responses from experience, rules animal activity. Consequently, no animal is bound by “duties” nor can it be the subject of corresponding rights, but we can be bound by duties towards animals even those that are not considered property of another human person.

Summing up : t he human animal is “Person” because human activity includes new concerns , due to intellectual powers and free will. By itself, intelligence is not a new way of acting but of knowing, and it is this new knowledge that should direct the free actions of the subject. Because the activity is not automatically predetermined, Man is held accountable for those free acts and is judged ethically good or evil. But the coexistence of biological conditioning and personal traits makes the human animal a profound mystery, frequently expressed in the terms of “the Mind-Body problem”, where the findings of different sciences have to be brought together into a satisfactory synthesis. We need to look at rationality –personhood- from different viewpoints to inquire about its origin and consequences, at the individual and the social level.

Inputs from the fields of Biology, Metaphyics, Ethics, Theology and History, will lead to a better understanding of how the concept of Person has been incorporated in different cultures, in codes of Law and in patterns of behavior. From Biology we should clarify the role of bodily structures, of genetic programming and conditioning,, of possible malfunctions at the organic level that will influence human behavior. From physical and metaphysical considerations we have to establish a logically sufficient reason for the traits that define a person, thus providing a basis for the concepts of rights and duties (human dignity and responsibility).

This will be clarified and extended by the theological ideas of personal relationships with a Creator who is also personal in nature, and both the first source of being and the final end that constitutes our eternal destiny. How these ideas have in fact appeared in different cultures through human history should be taken into account as well, not to make our reasoning depend upon a kind of democratic consensus, but rather to see the limitations and even errors of restricted ways of thinking in merely natural terms. It is obvious that a complete development of this outline would require a very extensive treatment by different experts in all those fields, something clearly not possible within the limits of this essay.

SOURCES OF PERSONAL ACTIVITY – THE ORIGIN OF MAN

We are part of the panoply of life forms at the animal level here on planet Earth, the only place where we have data and where scientific studies are possible. It is well established from biology that there is an intimate relationship among all living beings in the sense that all use the same set of aminoacids with the same chirality, the same cell size, the same basic chemistry in a liquid medium (carbon compounds in water). From the first cells of 3500 million years ago an unbroken process of development can be traced up to the present variety of orders, genres and species, culminating in the primate level that includes Man. Even if five great extinction events (some of astronomical origin) have eliminated perhaps 90% of all previous living forms, there are no indications of multiple starts from inanimate matter. The tree of life has lost many branches and has sprouted new ones, but there is only one trunk. Both the geological record and comparative anatomy support this view of a common origin and progressive development (evolution), even if many details have to be worked out to establish genetic descent and the concrete steps that led to each species.

The two key questions that cannot be answered in a scientific way by the available data concern the steps from inorganic material to the first living cell and from non-intelligent primates to Man. We are interested at this point in the second one: what is there that explains the difference between instinctive behavior (no matter how wonderful) and the new way of knowing that leads to purposeful and responsible acts, thus establishing the personal character of the human animal. Is it logically possible to say that organic evolution suffices to expect the emergence of intelligence and free will as the natural outcome of brain development and other anatomical changes? This is the hotly debated problem of Body and Mind, that we can clarify by accurately defining both terms with the methodology of the physical sciences and our own subjective experience.

The study of the material world begins with our sense reactions to external stimuli that impinge upon our sense organs. This implies a form of energy , understanding this term as the capacity to change in some way the state of a recipient (doing work). In fact, all of physics –from astronomy to chemistry and atomic theory- is the study of interactions ruled by conservation laws , the most basic of them being that in any material process there is never a creation from nothing nor a reduction to nothing, but only some change of a previous reality of the material world. The effect of material activity can only be found in something that will have material properties and that will be able, in turn, to cause further material interactions: from matter, one can only expect to obtain matter.

Modern science attributes all interactions to 4 “forces”: gravitational, electromagnetic, strong nuclear and weak nuclear. They have different intensities, ranges and outcomes, as well as the possibility of affecting only specific types of particles under concrete conditions. A common view that makes science possible as an objective description of the material world is stated as the “Cosmological Principle”: matter is the same everywhere in the Universe and it follows the same ways of acting under the same circumstances, so that the “Laws of Nature” are applicable everywhere and at all times. No cultural or personal conditionings or preferences will change the outcome of an experiment: human psychology has no influence outside the human person when we study the physical world. Scientific methodology requires that all processes be reproducible by any scientist using the correct experimental technique.

The only logical basis for this view is that human thought and free will cannot be considered as matter, endowed with the energies that cause the 4 interactions previously mentioned. This is also underlined by the obvious fact that neither can be measured in any experiment, since there are no parameters of mass, electrical charge, spin, wavelength, or anything else that physics uses to describe the components of matter. And if we deal with a new reality that is immaterial , we have to admit a source for it that is also immaterial: a human spirit that cannot be the result of organic evolution, even if it is found after matter has evolved to the highest degree of structure and complexity in the human brain.

A new spiritual element in Man needs a creating Spirit, a Creator who with a free act determines when and where the first Man appears on Earth after evolution has prepared the suitable organic structure. We can infer the presence of this new element in the life chain from evidence of rationality in the assembly of complex tools, the decoration of instruments and caves, the burials that include offerings for a mysterious life beyond the grave. Once the organic basis is sufficiently developed to be joined to the spirit, it is out of the realm of science to decide if the first Man had to be only one or several, at one point on Earth or many. The biological compatibility of all humans presently on Earth is a persuasive argument towards the acceptance of a single origin, geographically and in time. We are thus led to the statement that all human beings on Earth share the same nature, belong to the same species, have the same basic abilities and are subjects of the same rights and duties. They are Persons in the full sense of the word, without distinction of color, race, or culture.

Our conscious identity implies the unity of subject for all processes, material and intellectual, so that body and soul –matter and spirit- form a single unit in a mysterious but undeniable whole, excluding any accidental dualism. The human Person has to include the totality of Man, with mutual conditioning between matter and spirit, but with end-products of two clearly distinct levels. Any attempt to reduce Man to just spirit or just matter is unacceptable when applied to our total experience. Since our reasoning leads to a non-material (spiritual) reality as the source of thought and free will , we have the required reason for considering Man as a Person.

One rarely finds a denial of our body, but in some environments it seems logical to say that intelligence and free will can be explained in terms of electrical currents in the brain or quantum-mechanical effects in cellular structures. This is to reduce the real problem of sufficient reason to ways of detecting the presence of mental activity or of purposeful behavior. One cannot attribute the informational content of a TV show (interesting or boring) to the properties of the electrical currents in the receiver, or the poetic meaning of a literary work to the cellulose and ink of a book. The simple bending of an arm when I want is more important than the release of energy in the muscles and the leverage exerted by tendons and bones. The dependence upon a free decision excludes the deterministic process of simple physical forces, and the obvious fact that our will is not random but purposeful makes its operations incompatible with the probabilistic fluctuations of quantum-mechanical systems.

We know ourselves, and the world, by experience, by reasoning from sense inputs, and by acquiring knowledge from others. We first become aware of our thinking and of bodily changes from interactions between sense organs and “forces” in our surroundings. When the senses perceive and quantify inputs beyond their normal range of responses –with the help of instruments- we enter into the methodology of “science”, as applied to the properties and interactions of matter.

Intelligence looks for relations of cause, order (Beauty) and desirability (Goodness) in the data. This implies the use of the principles of identity, non contradiction and sufficient reason , that necessarily underlie all aspects of rational thought, be it in the development of science or in philosophy or theology. From the principle of identity we derive the constancy of behavior in non-living matter: things are what they are, and their properties determine their activity, thus supporting the objectivity and constancy of the laws of nature. The principle of non-contradiction requires self-consistency and the absence of absurd consequences in any reasoning process, so that in pure Math the only criterion of correct deductions is that they do not lead to a contradiction in their development or necessary consequences.

The search for a sufficient reason leads to hypothesis that should be examined in their theoretical sources, their logical consequences, and in the actual experimental checks when these are possible. We never accept as a sufficient reason a “just because” that doesn’t satisfy even a small child. This is frequently the real meaning of attributing to “chance” a physical result for which we have no known cause, as is the case when we try to establish a relationship between events that really have no logical connection. We should remember that chance is not experimentally measurable, it is not a parameter of any elementary particle or material structure, it can never be the cause of any event, and still less of order at any level.

The innate desire to find order in our knowledge is expressed in the search for patterns –physical or conceptual- where one finds the special satisfaction that we express with the general word beauty or harmony . It can be the simplicity and power of a mathematical expression or a generalized understanding of diverse aspects of nature previously unconnected in our experience: we can appreciate the beauty of the Law of Gravitation, applying to common objects, to planets and galaxies, and expressed with a simple equation by Newton. It is not uncommon for scientists to judge a hypothesis or theory in terms of its beauty: it introduces nothing superfluous or contrived or, on the contrary, seems cumbersome and arbitrary.

The same is true in the world of nature or art: combinations of shapes, volumes, lines and colors can give the pleasure of balance, proportion, contrast, gradual development, even just marvelous complexity at the microscopic level or overwhelming majesty in the grandeur of the heavens. It has been said that science develops from the sense of wonder that the thinking person cannot avoid feeling when studying nature at all levels. And it is well known that cave Man left paintings of great skill and beauty, as well as carvings and even primitive musical instruments: activities that have no relationship with mere survival or other practical concerns. They might have been considered of some magical value, but this is precisely the new “spiritual” aspect of human activity that includes symbols and concepts that are not found in any other species in the living world.

The search for Goodness is due to a value judgment regarding the suitability of some action to obtain a desirable end. Anything that is consonant with our needs, either at the biological or spiritual level, constitutes a good, from survival (which includes food, shelter, rest) to the fulfillment of our desire for affection, companionship and even knowledge and beauty, can be classified as a good that attracts and leads to activities ordered to obtain it. Whether those activities are consonant with human dignity –of the subject and of others- or opposed to it, determines the ethical value of an action.

ETHICAL CONSEQUENCES

Since the human person has some activities of a private order, while others impinge upon other members of the human family, the way human activity is subjected to norms and value judgments will address the question of what is consonant with human nature at both levels.

The development of rationality requires the constant search for Truth: no responsible decision can be based on wrong knowledge. This implies rights and duties concerning education, beginning with the family and continued at higher levels, made possible by society, not to impose any “brain washing” but to open all legitimate avenues of learning. Professional activities require competence that has to be acquired by learning in the proper institutions, and that then implies the right to compensation for services in any field.

The right to the necessary sustenance, to health care, to housing and work opportunities, will also be a consequence of the need to develop the individual, both physically and culturally. Society needs laws that ensure that this is the case for all citizens. International bodies are legitimately entitled to regulate commerce, travel, exchange of information, in order to achieve equal opportunities for everybody. Echoing Pope John Paul II at the UN, “society is for the individual, not the other way around”.

This is stated in the Declaration of Human Rights signed by members of the UN in 1948. These rights are not due to some concession by any kind of government, and they cannot be legitimally abrogated or conculcated. Because those rights are rooted on the very nature of the human person, they have to be respected at any stage of natural life , from conception to death, even if age, sickness or genetic disabilities make the full use of intelligence and free will impossible in some cases or circumstances.

The Person can never be reduced to the level of a “thing” to be manipulated or disposed of for economic or scientific reasons. This is especially relevant in the fields of Medicine or Biology: no treatment can be allowed for any other purpose than the good of the patient. Laws that ignore this norm cannot be legally binding, but must be resisted and repelled.

Because ethical considerations flow necessarily from the sense of dignity and responsibility of an intelligent subject, this aspect of human life must be present from the very moment that Man appears on Earth. Primitive burials are a clear sign of the conviction that other humans are different from animals and that somehow their existence after death must be helped by rites and objects that must accompany the deceased. The evidence of protracted care for the sick (for instance, when people subjected to a trepanning of the skull lived long enough for the bone to heal and close the opening) is another indication of family and social ties that imply a common feeling of dependence and duties for those unable to survive by themselves.

Still, in a primitive world where small groups lived in almost total isolation from other tribes, ethical norms developed in many different ways. Science, philosophy, art and ethical norms, form human culture , that is not inherited genetically, but transmitted by signs, endowed -arbitrarily and freely- with meaning : sounds (speech), visible forms (writing, comprehensible images) or gestures that convey information, a new category not found by any experiment. Because cultures evolved independently, different places and times gave rise to codes of ethics and laws that –in many cases- contradicted each other.

We can simply mention how all over the world we find indications of past slavery,, caste systems, denials of rights to women and children, human sacrifices, war as the common state of confrontation with nearby groups. But this kind of behavior is akin to the modern control of the individual by totalitarian regimes (Nazi Germany, Communist societies) and it is necessary to state that a significant number of signatories of the UN “Declaration of Human Rights” still fail to comply with the solemn compromise accepted in 1948. In those the human Person is rather considered only as a productive element for the impersonal State, and it is subjected to a control that restricts even the most basic rights of education, work, marriage and free movement, the practice of religion and association for legitimate ends.

In modern times, where the constant exchange of information and world-wide travel tend to create a uniform way of life, the final outcome of such contacts might lead to a common “culture” where the individual is led to think that whatever others do is correct for everybody. An implicit “relativism” will finally deny that there are ethical norms that arise from human nature itself and that anything that is not forbidden by law is morally acceptable. This is the underlying justification for abortion, euthanasia, genetic manipulation: instances where the person is degraded to the level of laboratory guinea pigs, useful as “things” to be manipulated for the benefit of others or destroyed when they become cumbersome and unprofitable for society.

A common statement that expresses this attitude is that “all cultures are equally to be respected”. If the word “culture” is not defined, the statement is meaningless: it can mean the way a group builds homes or entertains their citizens with music and dances. The most basic meaning should rather be the “system of common ideas that structure a given society”. Those ideas should determine personal and social behavior, thus being incorporated into codes of law, administrative and practical structures, rules of personal behavior. Over the course of time, the “way of life” transmitted from one generation to another within a human group, can also be termed a “culture” in so far as it incorporates commonly held values and concerns.

But the appreciation of a culture cannot simply rest upon its existence through a short or long time. If the culture leads to the denial of human rights to any kind of member of the group, or it incorporates a negative and hostile attitude toward other groups, the culture has no right to be respected and preserved. We must remember again and again that the human person is the subject of rights and duties by the dignity that is rooted upon the unique power to think and act freely. No external imposition can legitimately deprive a single person of what nature implies. Even civil disobedience might become a moral duty, no matter what the consequences, when moral good and evil are concerned.

One should also mention that the right of every person to have access to education, health care, modern developments of a kind that improves substantially human life, should take precedence upon considerations of an egotistical nature even if they seem to be justified by the desire to maintain primitive tribes in their original state to allow for their scientific study. To deny to a sick child the life saving attention that it needs and the opportunity to learn and develop fully as a human being is not acceptable from the moral viewpoint, either in a slum of a modern city or in the jungle of the heart of Africa. We might be unable to provide that help everywhere, but it should be our impossibility and nor a false respect for a primitive culture the deciding factor.

Governments everywhere have the duty to eradicate every type of exploitation of the weak and poor, be it through some kind of slave labor or its equivalent, or the demeaning traffic of drugs and prostitution, or racial and religious intolerance. The human person –every person- is the highest value we find on Earth.

Global concerns –about climate, overpopulation, famine, migration – are clearly in need of ethical rules that should look at the good of the persons affected, now and in the future, but destroying lives or condemning undeveloped nations to hunger and ignorance cannot be an option. The resources of our planet are more than sufficient to give every human being a level of nutrition, housing, education and medical care suitable for human dignity.

THEOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The human spirit, created by a Personal Creator, intelligent and free, appears as the apex of the development of the Universe. The Anthropic coincidences, at the very first instant of the Big Bang, can only be explained by a purposeful plan of the Creator to establish a meaningful relationship with personal beings. To invoke for their existence either a childish ”just because”, or to have recourse to chance within an unverifiable multitude of universes, is unscientific and totally empty of explanatory power. On the other hand, an intelligent and infinite Creator will not act without a purpose, and this cannot be an empty desire to watch how stars burn or lizards scurry over a planet. A Person is not satisfied with anything less than other persons.

This means that the “deistic” God accepted by some scientists as the final reason “why there is something instead of nothing” ends up by being absurd. Such a Supreme Creator would create a marvelous Universe just as a banal exercise of omnipotence, without caring for the persons who are able to reason to a First Cause and to be grateful for their existence. This is still more absurd if we extrapolate the evolution of the Universe to remote future ages when all the stars will be dead cinders and no life can survive anywhere.

In some Eastern philosophies, the final state implies the dissolution of individual persons into an undiferentiated “something”, not truly divine in a transcendent sense, where personal identity is lost. This is philosophically untenable and incompatible with the true idea of a Creator who is always infinitely superior and different from any creature: one cannot take seriously the proposal that finite and infinite will become an undifferentiated mixture and that the very notion of person will no longer be applicable. The same can be said of the recycling of human beings through reincarnations where the distinction between persons and animals is erased. And the final state, after the supposed purification attained in those reincarnations is described once more as the cessation of personal existence and activity.

In the Christian Creed, God is confessed as a Trinity, where the concept of Person surpasses our philosophical intuitions by presenting a unique Nature realized in three distinct Persons, with only one intelligence and will, so necessarily related that no single Person can exist or be described without reference to the other two. Thus the unicity of the Divinity is insisted upon, while stressing the divine life as a total and necessary communication of the entire nature from the Father to the Son and from both to the Holy Spirit. We cannot understand this, but we cannot understand matter either, when we try to reconcile the particle-wave duality into a single picture of elementary units of everyday matter.

No human philosophy or poetic effort could have imagined the Trinity, and we can only accept it through a Revelation that was not present in the Old Testament books of the Bible but that was gradually uncovered in the teachings of the New Testament. As we develop Theology –the effort to understand the revealed truths- we come to appreciate the depth of this mystery where the most intimate nature of the Godhead, while still incomprehensible, appears as the logical source of God’s relationship to humankind. If in the creation of finite spirits (angels) God can be said to seek living images of the divine nature, endowed with intelligence and free will and existing without constraints of space and time, their perfectly simple nature is so completely indivisible and self-contained that the communication of life –the very essence of the Trinity- cannot be shared by the created beings. They are incomplete images of the living God in that respect.

The creation of matter does provide the possibility of finding complex structures that can give part of themselves as a seed for new members of the species. But matter cannot have intelligence and free will, thus precluding the existence of Persons within the realm of pure matter. Without those attributes, there can be no meaningful relationship with the Creator.

The further step of joining matter and spirit in Man does achieve the complete image of God as a reality endowed with intelligence, free will and the ability to communicate life. Thus we find the description of the origin of Man in the poetic language of Genesis. Everything leads to the masterpiece of divine power, an Image and Likeness of the Creator, destined to share the divine happiness in a final state of intimate knowledge and love, outside the limits of space and time.

The Incarnation adds another mystery regarding the concept of Person, while underlining the infinite love of God and the dignity of Man. Christ, as God-Man, is adored as God, while being true Man, with soul and body on a par with ours. But we profess only one Person, divine, as the ultimate subject of activity and attribution, so that human activities are attributed to God and divine activities to the Man Jesus. Again, we cannot truly understand the mystery, but we can say that God has entered the human family, and that no greater glory can be imagined for any possible created being than to have God as brother.

It is true that we cannot do more than to accept a mystery that has baffled the best minds through the centuries, giving rise to all kinds of efforts to avoid the true divinity of Christ or to attribute to his humanity a nature that ultimately would deny his common descent from other human members of our race. Councils and Church Fathers were adamant in their insistence on the dual nature of Christ in the unity of a divine Person. Only thus could the reality of the Incarnation and Redemption be truly maintained.

Christ’s Resurrection is the final act of the saving and transforming plan of God for all mankind. A divine Person, with a body taken from the ashes of stars that formed our Earth and with a human mind and will, encompasses all levels of existence and carries our human nature to the intimate essence of the Godhead as the first fruits of the new kind of life that God wants for all of us. As individual persons, we are destined to exist forever, attaining the fullness of life with unlimited knowledge satisfying our minds and infinite love giving us the happiness proper of God in an unchanging eternity. The incredible variety of each human being through all of history will be a galaxy of lights, each different in a unique way of reflecting the perfection of the Creator, thus expressing as persons the multiple ways of sharing in the generosity of the Father from whom all good things come.

In terms of physical laws, the future of the Universe, with its predictable final state of emptiness, darkness and cold, seems to make its existence pointless, and the fact of the creation by God so that human persons will appear would no longer seem its sufficient reason. The only answer to the apparent absurd could be found in the immortality of the human spirit, not tied to the laws of physics by its very nature. But Theology goes farther, asserting for the human Person, body and soul, this new life inchoated by Christ’s resurrection and promised to all those who are joined to Him in a new kind of activity that is proper to God alone and that will be shared outside the limits of space and time.

Only in Christian Theology, based upon clear concepts of God and Man, of matter and spirit, is the unique dignity of each Person conserved.

Share this:

What It Means to Be a Human Person

It is time we get clear about the ontology of personhood..

Posted December 10, 2021 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- Christian Smith's excellent book, "What is a Person?," clearly spells out an ontology of human persons for sociology.

- The Unified Theory gives a clear ontology of the mental that directly aligns with Smith's view of human persons.

- There is now a clear bridge from psychology into sociology that clarifies the ontology of both mental behavior and human persons.

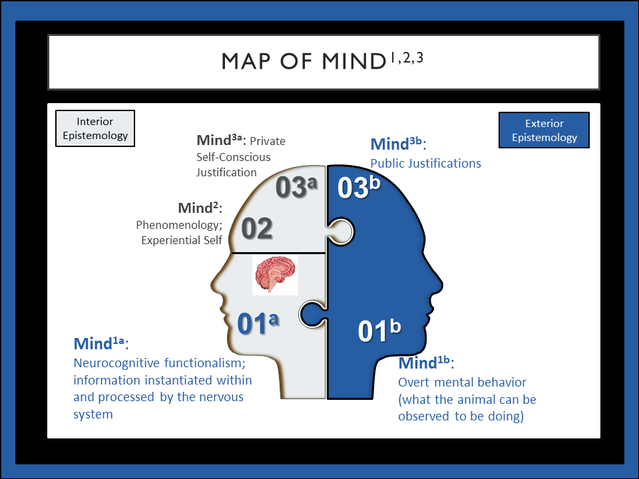

A central feature of the Unified Theory of Knowledge (UTOK) is that it affords us a way to scientifically frame the ontology of the mental (see here for this argument in detail). Via the Tree of Knowledge System, it shows how "mental evolution" began with the evolution of animals with nervous systems and complex active bodies during the Cambrian Explosion approximately 550,000,000 years ago. In addition, it clearly defines the mental behaviors of "minded animals" as consisting of sensory-motor looping functions that allow animals to develop paths of behavior investment via recursive relevance realization that produce a functional effect on the animal-environment relationship. Moreover, via the Map of Mind 1,2,3 , UTOK specifies why there are three domains of mental behavioral processes that must be differentiated, both ontologically and epistemologically.

The domain of Mind 1 refers to the domain of covert neurocognitive processes (Mind 1a ) that regulate the overt mental behavioral activities that are observable to others (Mind 1b ). Mind 2 refers to the subjective conscious experience of being in the world and it is only directly observable from the inside, that is from the subjective perspective of the animal. Mind 3 is present in human persons and refers to the self-conscious justification processes that take place within the individual's subjective field of experience (Mind 3a ) or between people in the form of verbal expressions to others (Mind 3b ).

Getting clear about the ontology of the mental is necessary to solve the problem of psychology. And this is a necessary step to link psychology to the social sciences. Indeed, it is at the intersection between psychology and the social sciences (as well as humanities and philosophy ) that we find one of the most central problems in the academy, which pertains to the question of what is a person? This question is directly taken up in Professor Christian Smith’s excellent work, What Is a Person? Rethinking Humanity, Social Life and the Moral Good From the Person Up .

Smith tackles this perspective from the vantage point of critical realism and personalism. Critical realism is the philosophy of science developed by the visionary Roy Bhaskar It can be thought of as developing a synthetic, " metamodern " philosophical position that effectively bridges between modernist scientific traditions that emphasize analytic truth claims and postmodern critical positions that emphasize the social construction of knowledge. That is, critical realism effectively works to clarify both the process by which humans socially construct knowledge (i.e., epistemology) and the scientific reality of nature as stratified levels of complexity (i.e., ontology). Smith combines this with personalism, which he acknowledges is less easy to summarize as a clear statement. He characterized personalism as a broad school of thought and collection of thinkers that enables us to emphasize the reality of human lived experience and human dignity. Smith puts the issue as follows:

The central idea in personalism that is relevant for my argument is deceptively simple. This is the belief that human beings are persons.

At first, this might sound silly as it seems self-evident and thus might appear to be akin to saying something like dogs are canines. But it is not. In fact, it is very consequential because persons are a particular kind of thing . Indeed, a central insight from UTOK’s analysis of the mental and the difference between animal-mental behavior and human mental behavior is the conclusion that humans are both primates and persons.

The question thus emerges regarding what Christian means by a person. Through a long series of detailed and powerful arguments, Christian delineates how personhood has emerged in evolutionary and social history and consists of a long list of intersecting capacities. Ultimately, he comes to define persons as follows:

By person I mean a conscious, reflective, embodied, self-transcending center of subjective experience, durable identity , moral commitment, and social communication who—as the efficient cause of his or her own responsible actions and interactions—exercises complex capacities for agency and intersubjectivity in order to develop and sustain his or her own communicable self in loving relationships with other personal selves and the nonpersonal world.

Smith’s analysis of the ontology of human persons is remarkably consistent with UTOK’s analysis of the ontology of the mental, from the animal into the human, and then into the emergence of the Culture-Person plane of existence. Indeed, I have argued repeatedly that the key to understanding humans from a scientific perspective grounded in a coherent ontology is to see them as primates that are organized by the two metatheories of Behavioral Investment Theory and the Influence Matrix and as persons, which is framed by Justification Systems Theory. Justification Systems Theory provides a framework for understanding the emergence of the domain of Mind 3 and the Culture-Person plane of existence. It aligns remarkably well with Smith’s analysis.

Importantly, Smith is a sociologist, not a psychologist. Indeed, his book has almost no psychology in it at all. Rather the book positions his argument for the ontology of human persons in relationship to other traditions in sociology, such as social constructionist traditions, network structuralist positions, and variable aggregate analyses. As such, we have a strong, independent, convergent argument, when the two positions are placed side by side.

According to the UTOK, the Enlightenment failed to produce a clear framework for understanding the proper relationships between matter and mind and science and social knowledge. This is called the Enlightenment Gap . It resides at that center of our modern state of chaotic fragmented pluralism. This gap means that we cannot go from our relatively coherent knowledge in the physical and biological sciences into the psychological and social sciences. Although he did not directly call it as such, the gap was nevertheless very well seen by Edward O. Wilson in his important book, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge . He described it as follows (p. 126):

We know that virtually all of human behavior is transmitted by culture. We also know that biology has an important effect on the origin of culture and its transmission. The question remaining is how biology and culture interact, and in particular how they interact across all societies to create the commonalities of human nature. What, in the final analysis, joins the deep, mostly genetic history of the species as a whole to the more recent cultural histories of far-flung societies? That, in my opinion, is the nub of the relationship between the two cultures. It can be stated as a problem to be solved, the central problem of the social sciences and the humanities, and simultaneously one of the great remaining problems of the natural sciences. At present time no one has a solution. But in the sense that no one in 1842 knew the true cause of evolution and in 1952 no one knew the nature of the genetic code, the way to solve the problem may lie within our grasp.

Another way of saying this is that the Enlightenment left us with a gap in scientifically understanding the ontological evolution of the animal mental into human persons and modern societies. This is why we cannot clearly trace the ontological trail from biology into the animal mind into a clear map of human mental behavior and the assemblages of societies.

UTOK’s frame affords us a way to bridge and resolve the Enlightenment Gap. Most importantly, it affords a coherent naturalistic ontology for the animal-mental into the culture-person plane of existence. Put differently, via its unified theory of psychology, UTOK bridges the gap from ethology and cognitive-behavioral neuroscience into human psychology. This "human psychology" sits at the base of the social sciences and frames human mental behavior.

What is so encouraging about Christian Smith’s work is that it shows how we can pick up the baton of understanding from human psychology and place it directly at the base of sociology, and from there advance into the social sciences that study large-scale social systems. Success in this means that the stage is being set for our capacity to resolve the Enlightenment Gap. This will enable us to start moving toward a second Enlightenment that gives rise to a scientific understanding of a coherent naturalistic ontology that is well situated to revitalize the human soul and spirit in the 21st century.

Gregg Henriques, Ph.D. , is a professor of psychology at James Madison University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Question of the Month

What is a person, each answer below receives a book. apologies to the entrants not included..

One of the most fundamental questions of anthropology is that of personhood. We might also consider it the starting point for all philosophy. Indeed, it was Martin Heidegger who most forcefully underlined the connection between anthropology and ‘the apprehension of Being’, that is, metaphysics. For him, only the human person might hope to find meaning in the world around them. Hinging on this dilemma of how to define the person are all of the perennial issues of philosophy, of ethics, and of sociology.

To define it succinctly: a person is a being endowed with imagination . A person is able to think abstractly, to project themself into imaginary situations, to plan for the future, and to reflect on the past. In other words, a person acts in the present moment not bound by mere instinct, but usually able to transcend the limits of the animal mind. A person is also inherently social. In order to flourish, a person should exist in communion with other persons, and in sovereignty over its inanimate surroundings. Its faculty of imagination is constructed of accumulated experience, and thereby continually works in relation to the world and to other beings inhabiting it.

This definition covers many possibilities. It seems likely that our Homo erectus ancestors would qualify for personhood. It also seems plausible that future artificial intelligence could hit the mark. Perhaps certain animal species might exist on this spectrum, at the lower scale. But what happens when we pass through the spectrum of personhood onto something greater ? Why should consciousness end with personhood? Might there be other levels of consciousness superior to that which the person enjoys? Such a state would pass beyond both instinct and imagination to something more. Might this be what the Scholastic philosophers termed ‘Perfect Knowledge’? Such knowledge would go beyond instinct and imagination in the way we apprehend them, ignorant as we are. In a certain sense, then, personhood is constrained only by Plato’s cave of illusion, and by our bodily limitations. This might not be a bad thing. It is our cave after all, our world, and our social playground.

Anthony MacIsaac, Institut Catholique de Paris

The question of what a person is, isn’t exclusive to philosophy. Consequently, there are many answers. In a physiological and biological context, a person is a human with certain essential physiological and biological characteristics. Legally, the answer is broader. According to the law, a person is anyone or anything that can initiate and be subject to legal proceedings. By this conception, any adult, corporation, or institution is a person, but a minor is not a person, a foetus is not a person, and a humanoid robot like Hansen Robotics’ ‘Sophia’ is not a person. This highlights that legal personhood is dependent solely on legal recognition. In this sense a legal person is similar to a political person. A political person is anyone who has citizenship. The robot Sophia has been granted citizenship in Saudi Arabia, which demonstrates the contingency of political personhood. Moreover, there is no shortage of people who have had their citizenship stripped, whose political personhood is therefore non-existent.

In philosophy, morally, a being is a person if they’re a moral agent, making moral judgements and taking moral actions. Metaphysically, the set of criteria for personhood include rationality or logical reasoning, consciousness, self-consciousness, use of language, ability to initiate action, moral agency (again) and intelligence. Robot Sophia, a young child, and even an alien may meet sufficient criteria here. Even a foetus would potentially meet the criteria.

In practice, however, only legal and political personhood are of significance, and these are contingent on recognition by political or legal institutions. However, metaphysical and moral personhood provide an intellectual foundation upon which to discuss legal and political personhood. Therefore I suggest that a person in its full sense – both theoretically and practically – is a metaphysical and moral being with legal and political recognition . The latter is sufficient for practical personhood, the former for theoretical personhood, and both are necessary for full personhood.

Diogo Joao Baptista Gomes, Brachtenbach, Luxembourg

The answer is deceptively simple at face value. I am a person. You are a person. Every relative, friend, colleague, and acquaintance in your life is a person. Perhaps then you are tempted to say that a person is a human being. However, ‘human being’ evokes the human animal, whilst ‘person’ is something more esoteric, linked with one’s personality or intelligence, for example.

Boethius agreed. In his Theological Tractates he defined ‘person’ as ‘an individual substance of a rational nature’. Boethius used the etymology of the word to help him to form his definition. I find this interesting because ‘ persona ’ in Greek was a theatrical mask. So is personhood a mere façade? Are we all just animals masquerading as something more? And if we are all lowly beasts with overblown egos, is it possible that other species fit the criteria for personhood better than we do?

John Locke argued that a person is something that ‘can conceive itself as itself’. By that definition, it isn’t just human beings who qualify for personhood – great apes, elephants, and dolphins would qualify too. Philippa Brakes published an article titled ‘Are Orcas non-human persons?’ Orcas are self-aware, intelligent, and emotional beings. Their paralimbic (brain’s emotional) system is highly developed, even when compared to those of humans, and their insula cortex (which is linked to compassion, empathy, self-awareness, and sociability) is the most elaborate in the world.

No doubt some will reject this. Orcas can’t be people . They are infamously brutal killers: they’re even colloquially known as ‘killer whales’. A recent paper by John Totterdell described a coordinated, gruesome orca attack against a blue whale, in which the orcas stripped the creature of its blubber and fed off it whilst the whale was still alive. Surely this can’t be the behaviour of a person? Yet this response ignores the innumerable atrocities committed by human hands.

It scares us to think that other creatures could match, or perhaps exceed, our own intellectual and emotional understanding. But perhaps it is time to broaden our minds beyond the anthropocentric definition of personhood.

Rebecca McHugh, Ellesmere Port, Cheshire

In the first place, to be a person is to be human. Humans are animals, but they are animals who know . All animals can be said to ‘know’ in limited ways, largely defined by their bodies and their physical needs: they recognize what is good for them and they pursue it. This is not to say that we humans are not limited or defined by our physical bodies and needs: indeed we are! Every human person has a body, lives and grows in and as that body. But we can know in a way that extends far beyond the physical. We can abstract and define realities: we do not just see a rabbit and chase it; we know it as a rabbit. I can know myself as myself. We grow in self-knowledge and in knowledge of the world around us. Why ? and What ? are favourite questions. We become aware of the self-evident principles of life. I remember an occasion when I was looking after some small nieces and their even smaller brother. I bought them ice-creams; and because the boy was so small, I offered him half an ice-cream. But no! He was already aware that ‘whole’ is more – and more desireable – than half!

We are aware of and conscious of ‘myself’, but we are also know others as ‘not me’, and in our relationships with others our self-identity, our personality , develops. It is of course possible for the development of personality in a child to be, as it were, smothered by too much attention from already-formed personalities. Ideally, and normally, a child develops as a person as their knowledge of the world grows, relationships flourish, and choices are made and lived. For with knowledge we have free will, just because, unlike the rest of the animal world, our choice is not determined beforehand by the physical – by our bodies. Although the physical necessarily plays a large part in our development, nevertheless, the human, the person, is equipped freely to choose what he or she knows to be good.

Sr. M. Valery Walker OP, Stone, Staffordshire

Perhaps being a person requires some kind of psychological continuity involving memory and self-awareness. Yet, even if Uncle Rob has serious dementia we will continue to treat him as if he is a person. It is as though the term ‘person’ is not really descriptive , more evaluative . We continue to care for him and continue to feel compassion and love for him. Could not one therefore argue that a person is a being that is capable of being an object for care, compassion and love ?

It may be thought that this is irrational and sentimental. After all, we might care for our goldfish but be unconvinced that the goldfish is a person. We might love our teddy bear, which is clearly not a person. But the relationship we have to Uncle Rob is different to those we have to a goldfish or teddy bear. How we treat Uncle Rob is related to our wider vision of human life, including such fundamental factors as the powerful human intimacies that bind us to him, and the suffering and death that comes to all families. Curiously, in this marvellous yet horrendous nexus, Uncle Rob’s lack of cognitive capacity, far from disqualifying him from personhood, becomes one of the facts that reminds us that he is a person. While diminished cognitively, he yet remains an undiminished person . He remains fully the object of the kind of concern we can only direct at persons.

Such a view of persons partly explains our discomfort at regarding computers as persons, despite their cognitive capacities. Even a figure as complex as the Terminator does not strike us as fully a person. We feel that we are dealing rather with a cognitively sophisticated other . This also reflects the fact that the term person , because it is partly evaluative, does not pick out a metaphysical category, but expresses a relationship of concern we have for certain beings.

Robert Griffiths, Enton, Godalming

In a rush to bring order to the perceptual chaos that is our environment, the human brain tends to use rules of thumb, which, by their very nature, promote generalization based on information from prior experiences. In a way, the brain is constantly playing connect-the-dots by making predictions about how the dots are supposed to be connected. Personhood, in essence, is a cognitive construct – a mental picture of an individual drawn by connecting the dots, which are the perceptual features or physical characteristics of the individual. Unlike ‘human’ – a concept grounded in the biological reality of neurons, tissues, and bones – a ‘person’ exists purely within the mind, and thereby is influenced by cognitive schemas of one’s own or with whom one interacts.

This view implies that you can play host to multiple persons, where you are at least partially in control of the kind of person you are, constantly changing and modifying it in response to feedback from your surroundings. That, in turn, affects others’ perception of you, and elicits a similar feedback loop within them, which then changes your surroundings again. You connect the dots of your personhood in a particular way based on your beliefs, while others do it per their own beliefs. The resulting pictures are quite different. Making things even more chaotic, the constant back-and-forth between individuals and their surroundings means the dots keep moving while the lines are being drawn.

We can see evidence for this view of personhood in colloquialisms like ‘He became a completely different person’ or ‘You’re not the same person I fell in love with’. Interestingly, such sentiments are usually not observed when an individual changes their gender or radically alters their features through surgical means. That again suggests that a person is not a physical object but a mental concept, an effort by our brains to construct coherent narratives from the multiplicity of sensory experiences. An individual is a lot like a complex number. The equivalent of the real part is the physical, mechanical structure of a body, while anchored to it is a mental part that contributes to the behaviour and nature of the whole. That mental part is the person.

Rudradeep Guha, Vadodara, India

“Well! I’ve often seen a cat without a grin’, thought Alice;’but a grin without a cat! It is the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!” – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

The inner world of the human being is surprisingly similar to the grin of the Cheshire Cat: the ‘psyche’ (consciousness, perception, needs and motives) seem to be there, but the ‘owner’ is not visible. To see the owner behind the grin is to answer the question ‘What is a person?’

We are each ultimately unknowable to other people, but we also need other people to come to know ourselves. We are dependent on the perceptions of people outside ourselves. According to the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975), another person can be revealed only in a dialogue, in the process of mutual understanding in which “the activity of the knower is combined with the activity of the discoverer.” A person then is the mutual co-existence of ‘I’ and the ‘other’ and as such cannot be an ‘object of study’: it can only become a subject in a dialogue, for whom the other is not ‘he’, ‘she’, or ‘I’, but a completely developed ‘you’. Therefore, the self is not an individual psychological phenomenon, but a decentred, dynamic and permeable social entity in which consciousness is not the property of the individual but a shared social phenomenon. Consciousness is always a product of responsive interactions, and cannot exist in isolation. Even hermits are still in dialogue, with their ecological surroundings, or with multiple inner voices.

Bakhtin noted that a person has no internal sovereign territory, but is wholly and always on the boundary; looking inside himself, he looks into the eyes of another with the eyes of another. So the ‘owner’ behind the grin is a being for another and through the other, for oneself.

Nella Leontieva, Sydney, N.S.W.

Person’ is an important word. Since a 1973 U.S. Supreme Court ruling on abortion, Americans have bitterly argued whether a baby in the womb is a person. If it is, it has moral and legal rights, such as the right to life, and thus it shouldn’t be killed. Note that I said ‘baby in the womb’ and ‘killed’. Those favoring unrestricted abortions would replace ‘baby’ with ‘fetus’, which is a mass of cells that can be aborted instead of ‘killed’. Words matter. However, whatever terms you use, the issue is the same: ‘Is the baby/fetus growing in the womb a person?’

Is the issue a metaphysical one or a moral one? One of being, or one of status in the moral order? At first it seems to be the former, but I believe it is the latter. The biology is comparatively straightforward; everyone can agree on the biological situation, but not whether it is a person. The real issue is, ‘What rights (moral and legal) shall we say that the baby/fetus has?’

It would be wonderful if we could definitely say what a person is so that all the world would agree. But we cannot. Attributes commonly describing a person are consciousness, self-awareness and personal identity, individuality, rationality, feelings (pain and pleasure, love and hatred, fear of death, etc), ability to choose (free will), set long term goals, and experience humor and beauty. I am inclined to think all of these attributes are necessary to the concept of personhood. Unfortunately, each of these attributes seems to allow gradation. Also, the marginal cases, such as newborn babies and comatose individuals on life support systems, lack one or more of the ‘required’ attributes. These considerations imply a scale of personhood. This is disturbing, for in the past such thinking has justified oppression and slavery. Most of us demand that a newborn baby and the comatose patient be considered persons, because we care for them as persons. Our pets have feelings and we have feelings for them, and so in some respects they deserve that we treat them as persons. And we do, but not fully so. As for aliens and robots, I think they can wait until we have a better grasp of the issue here and now.

John Talley, Rutherfordton, NC

Who am I? The crying child asked the father. When am I? The heart beseeched the absent lover. Why am I? Existence sighed under the sullen sky. Where am I? The mind questioned the tired body. What am I? The man whispered unto himself.

“You are stars stirred with consciousness” The mirror whispered to the man. “You dwell in purpose, promise, dream and future plan” The body told the broken mind. “You are nothing beyond the will to be” As the spinning heavens rained its light on me. “You bleed when nothing else matters” The lover nursed her broken heart. “For you are a window, a forest, a reason, a door, Life’s memory of what came before, Because you are a person” The father held the crying child. “Man unbeknownst to himself Being unreconciled Nothing less, my love, And nothing forevermore.”

Bianca Laleh, Totnes, Devon

Next Question of the Month

The next question is: How Do You Change Someone’s Mind? Please give and justify your answer in less than 400 words. The prize is a semi-random book from our book mountain. Subject lines should be marked ‘Question of the Month’, and must be received by 13th June 2022. If you want a chance of getting a book, please include your physical address.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

The Human Person

What Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas Offer Modern Psychology

- © 2019

- Thomas L. Spalding 0 ,

- James M. Stedman 1 ,

- Christina L. Gagné 2 ,

- Matthew Kostelecky 3

Department of Psychology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, USA

St. joseph’s college at the university of alberta, edmonton, canada.

Discusses the Aristotelian-Thomistic view of the human person

Reviews the ways in which the Aristotelian-Thomistic view can provide a philosophically sound foundation for modern psychology

Offers an interdisciplinary and integrative approach to theoretical psychology and cognitive science

Represents the first attempt to apply classical realism to all or most areas of modern psychology

5099 Accesses

8 Citations

9 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (8 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

- Thomas L. Spalding, James M. Stedman, Christina L. Gagné, Matthew Kostelecky

The Metaphysical Foundations of the Human Person

Human and non-human cognition, embodied and humanistic views of cognition, emotion and cognition, human flourishing, the human in society, summary and conclusions, back matter.

- Cognitive Science

- Linguistics

- Thomas Aquinas

- Theoretical Psychology

- Embodied Cognition

- Flourishing

- Human and Non-Human Animal Cognition

- Concepts and Categorization

About this book

This book introduces the Aristotelian-Thomistic view of the human person to a contemporary audience, and reviews the ways in which this view could provide a philosophically sound foundation for modern psychology. The book presents the current state of psychology and offers critiques of the current philosophical foundations. In its presentation of the fundamental metaphysical commitments of the Aristotelian-Thomistic view, it places the human being within the broader understanding of the world.

Chapters discuss the Aristotelian-Thomistic view of human and non-human cognition as well as the relationship between cognition and emotion. In addition, the book discusses the Aristotelian-Thomistic conception of human growth and development, including how the virtue theory relates to current psychological approaches to normal human development, the development of character problems that lead to psychopathology, current conceptions of positive psychology, and the place of the individual in the social world. The book ends with a summary of how Aristotelian-Thomistic theory relates to science in general and psychology in particular.

Authors and Affiliations

Thomas L. Spalding, Christina L. Gagné

James M. Stedman

Matthew Kostelecky

About the authors

Thomas L. Spalding is a Professor in the Department of Psychology and the Associate Dean Graduate Studies in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Alberta. His research focuses on the psychology of concepts and the relation between the human conceptual and language systems and has been funded by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), as well as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). He is the author of over 65 journal articles and book chapters and over 100 conference presentations and invited talks.

James M. Stedman is a Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas, Health Science Center at San Antonio. He has written on an array of topics in psychology, including child clinical pathology and treatment, education in clinical and counseling psychology, and application of Aristotelian Thomistic philosophy to modern psychology.

Christina L. Gagné is a Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Alberta. Her work focuses on the human conceptual system and compositionality/productivity within the conceptual system and language system. Dr. Gagné’s research is funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and she has been the author on over 70 book chapters and journal articles and over 100 conference presentations and invited talks. She has served on several editorial boards and is an associate editor of The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Morphology.

Matthew Kostelecky is an Associate Professor, Philosophy, at St. Joseph’s College at the University of Alberta. He works on the history of philosophy with a particular focus on medieval metaphysics and cognitive theory. He is the author of multiple articles on the metaphysics of Thomas Aquinas, his sources, and his larger context. Additionally, he is the author of Thomas Aquinas’s Summa contra gentiles: a mirror of human nature , a monograph that disentangles the role and method of metaphysics from the other sciences in Thomas Aquinas’s thought, while simultaneously presenting his account of human nature.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : The Human Person

Book Subtitle : What Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas Offer Modern Psychology

Authors : Thomas L. Spalding, James M. Stedman, Christina L. Gagné, Matthew Kostelecky

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33912-8

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology , Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-33911-1 Published: 19 December 2019

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-33914-2 Published: 19 December 2020

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-33912-8 Published: 13 December 2019

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIII, 172

Number of Illustrations : 1 b/w illustrations

Topics : Cognitive Psychology , Philosophy of Mind , Personality and Social Psychology , History of Psychology , Ontology

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Berkley Center

Human persons and human dignity: implications for dialogue and action.

By: Thomas Banchoff

August 19, 2013

" Contending Modernities ," August 19, 2013

What is the human person? As human beings, we are biological as well as social creatures; we inhabit both physical and cultural space. What distinguishes us as persons , and not just as organisms, is a culture of human dignity – the shared idea that, as human beings, we are entitled to respect and recognition from one another.

Where does the dignity of the human person come from? Broadly speaking, one can distinguish secular-scientific and religious foundations.

From a secular and scientific angle, we have dignity and should respect and recognize one another because of our common humanity. Some emphasize our shared capacity for independent thought; in line with Immanuel Kant, they see autonomy and rationality as a foundation for human dignity. Others focus more on our ability to identify and sympathize with others, an approach related to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s concept of “pitié” and Adam Smith’s “moral sentiments.”

Recent advances in evolutionary biology and neuroscience have deepened our understanding of this latter, relational approach to the foundations of human dignity. In the long run, evolution appears to have favored the development of ecological sensitivity, group identification and solidarity, and cooperation in the acquisition and shared use of resources. In the here and now, new developments in neuroscience suggest that our brains are much more than autonomous information processors; they change and grow through our interactions and relationships with others and with our external environments.

Interestingly, scientific methods that do not begin with the concept of human dignity are increasingly leading to a conclusion compatible with it — that we have good evolutionary and biological reasons to acknowledge one another as fellow human beings worthy of respect and recognition and therefore endowed with an intrinsic dignity.

For Catholicism and Islam, the focus of the Contending Modernities project , the dignity of the human person has divine foundations. Because God created each of us and cares for each of us, each individual person has an intrinsic and inviolable dignity. The moral theology of the person is most developed in Christianity; it is connected with the mystery of the Trinity (one God in three persons), and in the Incarnation (God becoming a human being.) But the idea of the person, as a creature of an all powerful and merciful God, also plays an important role in Islam. God reveals his law to humankind and calls us to live as His co-regents on earth, honoring one another with recognition and respect.

There is, of course, a fundamental asymmetry between the secular-scientific and the religious understandings of the human person. The non-believer will reject the idea that the dignity of the human person has divine origins, while the believer will typically assert that human dignity has both divine and natural foundations.

Yet this asymmetry need not be a barrier to dialogue. In our contemporary era, even those who reject the idea of human dignity as fuzzy and unscientific generally affirm the importance of according basic respect and recognition to all human beings. The basic idea of the human person and of universal human dignity is shared, even as terminology differs. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which emerged out of decades of contestation within and across secular and religious traditions – and in revulsion against the horrors of two world wars and the Holocaust – remains the clearest and most powerful expression of this far-reaching consensus.

In practice we know that this broad contemporary convergence around the idea of the human person and human dignity, across the secular-religious divide, coexists with fierce disagreement on a range of ethical and policy questions. Is the human embryo or fetus a human person deserving of protection? Are primates or other non-human animals to be considered persons with intrinsic dignity or rights? Should governments work to secure equality of opportunity for their citizens and provide a minimum standard of living for all? Should governments and citizens share their wealth with those in need outside, as well as inside, a nation’s borders? Questions relating to the human person and human dignity can be multiplied across economic, social, cultural, and foreign policy domains (even if, in the United States, they tend to center on bioethics).

A key challenge in such ethical and policy debates, within and across secular-scientific and religious communities, is to keep the ideas of the human person and of human dignity in the foreground. That means asking what is at stake for particular people and their livelihoods in particular contexts, as well as thinking through the ethical implications of our individual and collective decisions for global humanity, at a time when the rapid advance of technology and of globalization in all its dimensions is rendering those decisions more complex and consequential.

A focus on the human person has a further implication, perhaps the most challenging of all – that in all these ethical and policy controversies, we should acknowledge the humanity and dignity of our interlocutors, no matter how much we may disagree.

This article was originally published on the University of Notre Dame blog " Contending Modernities ."

What Makes Us Human?

- Philosophical Theories & Ideas

- Major Philosophers

There are multiple theories about what makes us human—several that are related or interconnected. The topic of human existence has been pondered for thousands of years. Ancient Greek philosophers Socrates , Plato , and Aristotle all theorized about the nature of human existence as have countless philosophers since. With the discovery of fossils and scientific evidence, scientists have developed theories as well. While there may be no single conclusion, there is no doubt that humans are, indeed, unique. In fact, the very act of contemplating what makes us human is unique among animal species.

Most species that have existed on planet Earth are extinct, including a number of early human species. Evolutionary biology and scientific evidence tell us that all humans evolved from apelike ancestors more than 6 million years ago in Africa. Information obtained from early-human fossils and archaeological remains suggests that there were 15 to 20 different species of early humans several million years ago. These species, called hominins , migrated into Asia around 2 million years ago, then into Europe and the rest of the world much later. Although different branches of humans died out, the branch leading to the modern human, Homo sapiens , continued to evolve.

Humans have much in common with other mammals on Earth in terms of physiology but are most like two other living primate species in terms of genetics and morphology: the chimpanzee and bonobo, with whom we spent the most time on the phylogenetic tree. However, as much like the chimpanzee and bonobo as we are, the differences are vast.

Apart from our obvious intellectual capabilities that distinguish us as a species, humans have several unique physical, social, biological, and emotional traits. Although we can't know precisely what is in the minds of other animals, scientists can make inferences through studies of animal behavior that inform our understanding.

Thomas Suddendorf, professor of psychology at the University of Queensland, Australia, and author of " The Gap: The Science of What Separates Us From Other Animals ," says that "by establishing the presence and absence of mental traits in various animals, we can create a better understanding of the evolution of mind. The distribution of a trait across related species can shed light on when and on what branch or branches of the family tree the trait is most likely to have evolved."

As close as humans are to other primates, theories from different fields of study, including biology, psychology, and paleoanthropology, postulate that certain traits are uniquely human. It is particularly challenging to name all of the distinctly human traits or reach an absolute definition of "what makes us human" for a species as complex as ours.

The Larynx (Voice Box)

normaals / Getty Images

Dr. Philip Lieberman of Brown University explained on NPR's "The Human Edge" that after humans diverged from an early-ape ancestor more than 100,000 years ago, the shape of the mouth and vocal tract changed, with the tongue and larynx, or voice box, moving further down the tract.

The tongue became more flexible and independent and was able to be controlled more precisely. The tongue is attached to the hyoid bone, which is not attached to any other bones in the body. Meanwhile, the human neck grew longer to accommodate the tongue and larynx, and the human mouth grew smaller.

The larynx is lower in the throats of humans than it is in chimpanzees, which, along with the increased flexibility of the mouth, tongue, and lips, is what enables humans to speak as well as to change pitch and sing. The ability to speak and develop language was an enormous advantage for humans. The disadvantage of this evolutionary development is that this flexibility comes with an increased risk of food going down the wrong tract and causing choking.

The Shoulder

jqbaker / Getty Images

Human shoulders have evolved in such a way that, according to David Green, an anthropologist at George Washington University, "the whole joint angles out horizontally from the neck, like a coat hanger." This is in contrast to the ape shoulder, which is pointed more vertically. The ape shoulder is better suited for hanging from trees, whereas the human shoulder is better for throwing and hunting, giving humans invaluable survival skills. The human shoulder joint has a wide range of motion and is very mobile, affording the potential for great leverage and accuracy in throwing.

The Hand and Opposable Thumbs

Rita Melo / EyeEm / Getty Images