An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Navigating Complex, Ethical Problems in Professional Life: a Guide to Teaching SMART Strategies for Decision-Making

Tristan mcintosh.

1 Bioethics Research Center, Division of General Medical Sciences, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

Alison L. Antes

James m. dubois.

This article demonstrates how instructors of professionalism and ethics training programs can integrate a professional decision-making tool in training curricula. This tool can help trainees understand how to apply professional decision-making strategies to address the threats posed by a variety of psychological and environmental factors when they are faced with complex professional and ethical situations. We begin by highlighting key decision-making frameworks and discussing factors that may undermine the use of professional decision-making strategies. Then, drawing upon findings from past research, we present the “SMART” professional decision-making framework: seeking help, managing emotions, anticipating consequences, recognizing rules and context, and testing assumptions and motives. Next, we present a vignette that poses a complex ethical and professional challenge and illustrate how each professional decision-making strategy could or should be used by characters in the case. To conclude, we review a series of educational practices and pedagogical tools intended to help trainers facilitate trainee learning, retention, and application of “SMART” decision-making strategies.

Our aim is to illustrate how to effectively educate professionals on ways to apply decision-making strategies when they are faced with complex professional and ethical issues. Appropriate and effective application of these strategies is a trainable skill that can be developed in individuals from a range of backgrounds, disciplines, and career stages. We first explore the complexities of professional decision-making in a research context and highlight an innovative compensatory strategy framework. Then, we present a case example of proper and improper application of these strategies when navigating complex professional and ethical situations. We then showcase pedagogical techniques intended to integrate these compensatory strategies into training activities and facilitate retention and application of these strategies. The term “trainees” is used throughout and refers to any individual, regardless of career stage, who learns from and takes part in training on professional decision-making strategies. In sum, the intent of the present effort is to describe how to provide trainees with strategy-based knowledge and skills needed for professional decision-making. These strategies ultimately serve to facilitate better ethical decision-making and professionalism.

Professional Decision-Making Frameworks

Professionals, including those who conduct research, regularly face complex circumstances that require professional decision-making skills. Although professionalism has been defined in multiple ways, for the purposes of the present effort, we define professionalism as integrating ethics and other relevant factors (e.g., competence, collegiality, institutional and departmental culture) needed to ensure public trust and achieve the goals of the profession (e.g., healing in medicine, generating new knowledge in research) ( Stern and Papadakis 2006 ; Swick 2000 ; van Mook et al. 2009 ). Unfortunately, the nature of situations professionals encounter and unconscious self-serving biases all professionals have may undermine the effectiveness of professional decision-making. Therefore, professional decision-making necessitates careful navigation and includes weighing different options to address the issue at hand, forecasting likely implications of actions, and gathering more information from multiple reliable sources ( Antes et al. 2010 ; Stenmark et al. 2011 ).

Two different frameworks of professional decision-making can be useful when professionals are confronted with these challenging circumstances: 1) a rational decision-making framework ( Goodwin et al. 1998 ; Oliveira 2007 ), and 2) a psychological framework ( DuBois et al. 2015a ; Mumford et al. 2008 ). Rational decision-making, also referred to as normative decision-making, is characterized by adherence to a set of established principles that guide decision-making, often in a group setting ( Hoch et al. 2001 ; Oliveira 2007 ). Specifically, rational decision-making involves the identification of key components of a situation and justifying decisions related to this situation when different viewpoints are in conflict with one another ( DuBois 2008b , 2013 ). Moreover, those who engage in rational decision-making analyze a number of possible alternative outcomes prior to making a definitive choice and make their decision based on the most likely and best possible outcome ( Hoch et al., 2001 ). This type of decision-making lends itself well to circumstances when professionals are unsure how to address an ethical dilemma, when a group is trying to establish best policies, or when there is disagreement among stakeholders on issues such as relevant facts and norms ( DuBois 2013 ). As it relates to ethical dilemmas, rational decision-making facilitates identification of key ethical concerns that society acknowledges as integral to rational discussions about ethical issues ( DuBois 2013 ).

The psychological framework related to professional decision-making is characterized by a confluence of situational complexities and self-serving biases that influence the way people frame and approach problems ( Bazerman and Moore 2013 ; Mumford et al. 2008 ). Oftentimes, a “correct” or “best” approach to these problems may not be apparent because of factors such as conflicting interests or needing to address concerns of multiple stakeholders ( Dana and Loewenstein 2003 ; Mumford et al. 2007 ; Weick et al. 2005 ). Being able to make sense of and effectively respond to these problems hinges on one’s ability to manage biases and attend to and utilize relevant information appropriately. This approach to professional decision-making lends itself well to situations in which professionals, when faced with complex ethical dilemmas, intend to take the best course of action but have difficulty doing so due to personal and environmental constraints ( Antes 2013 ). Such constraints may include complexity of social dynamics, heightened emotions, conscious and unconscious biases, uncertainty, and ambiguity.

The present effort will highlight strategies intended to facilitate the psychological framework of professional decision-making, as opposed to rational decision-making, because these strategies enable bias management and quality information integration, application, and synthesis. Moreover, these strategies are beneficial in situations where environmental constraints act to undermine an individual’s intent to take the best possible course of action. These strategies help professionals deal with moral distress, situational limitations (e.g., political tensions, increases in regulations, cultural differences), and internal limitations (e.g., ignoring key elements of a situation, self-centered thinking, unwarranted certainty) ( DuBois et al. 2016 , 2015b ).

In what follows, we will demonstrate the utility of a psychological decision-making framework within the context of the research profession, the SMART professional decision-making framework: s eeking help, m anaging emotions, a nticipating consequences, r ecognizing rules and context, and t esting assumptions and motives. Research provides a useful context for illustrating SMART strategy training because research frequently involves complexity, ambiguity, assumptions, stress, ethical considerations, and conflicts of interest. Further, ethics training is mandated for all federally-funded research trainees and many key personnel on grants involving human or animal subjects. We believe the SMART professional decision-making framework can add value to ethics training programs in research and other professions.

Constraints to Professional Decision-Making

Several factors can interfere with optimal professional decision-making. We discuss four factors that can be effectively addressed through the use of SMART decision-making strategies: Complexity, ambiguity, biases, and unusually high or negative emotions.

Professionals must carefully address and navigate complex and dynamic issues throughout their careers. For researchers, complexity often characterizes data management, mentoring relationships, protection of research participants, institutional hierarchies, and conflicts of interest ( Anderson et al. 2007 ; DuBois 2008a ; Jahnke and Asher 2014 ). These issues oftentimes involve multiple competing goals, guidelines, and stakeholder interests and are not simple to address ( Werhane 2008 ).

For example, a researcher may have competing interests between their funding agency’s research priorities and their own profession’s methodological norms and standards. These conflicting interests and complex relationships between funding agencies and researchers may undermine confidence in the quality of research being conducted if not appropriately managed ( Irwin 2009 ). Researchers are responsible for identifying and navigating conflicts of interest. Navigating conflicts of interest necessitates reconciling conflicting values, perspectives, and agendas of multiple stakeholders at the individual, institutional, governmental, and national levels. Failing to do so may result in public mistrust of research, harm to others, tarnished personal and professional relationships, or ruined careers. Thus, professional decision-making strategies can be applied when attempting to identify, prioritize, and reconcile complex stakeholder interests. The multifaceted nature of ethical and professional situations in a research context has the potential to derail professional decision-making if not handled appropriately.

Uncertainty

It is common for individuals in research fields to be exposed to new and unfamiliar environments and projects where considerable gaps in knowledge may exist. Uncertainty may arise when regulations grow in complexity over time, when a researcher moves into a new research space, or when a researcher moves to a new nation with a different culture or an unfamiliar set of rules and norms ( Antes et al. 2017 ; DuBois et al. 2016 ). Navigating social and professional life in a new culture, with a new language, and with possibly different ethical standards can be challenging and stressful.

Uncertainty may inadvertently lead to the misinterpretation of norms and other social and professional cues integral to making professional and ethical decisions ( Palazzo et al. 2012 ). This is because individuals may lack essential information needed for interpreting a given situation appropriately ( Sonenshein 2007 ), which may result in failure to think of long-term downstream consequences of their actions or failure to consider the entire range of possible courses of action. Moreover, “unknown unknowns” may result in a breakdown of quality professional decision making if help is not sought from other individuals or resources that are able to provide sound guidance on these issues.

For example, a lab manager may task a new postdoctoral fellow with collecting data from participants using a certain technique, but the postdoc may be unfamiliar with the standard procedures for doing so. Tense lab dynamics between the lab manager and other lab members may worsen this uncertainty by making it uncomfortable or difficult for the postdoc to seek help from another lab mate. Similarly, these lab dynamics may signal to the postdoc that limited or hostile communication is the norm in the lab, which may prompt the postdoc to proceed with their work in isolation. Failure to seek help due to social ambiguities may result in costly protocol violations or detrimental outcomes for both the participants and researchers involved. Without proper use of professional decision-making strategies, facing uncertainty or unfamiliar norms may lead to poor decision-making and negative consequences.

Despite even the best intentions to maintain objectivity, professionals may be subject to unconscious biases when processing information ( Hammond et al. 1998 ; Kahneman 2003 ; Palazzo et al. 2012 ). This poses a considerable challenge to professionals who aim to accurately and objectively process available information relevant to a given situation and to make a sensible, unbiased decision ( Bazerman and Moore 2013 ). Many of these judgment errors, or cognitive distortions, are automatic, making it challenging for individuals to fully understand the negative influence of biases on decision-making and information processing ( Kahneman 2003 ; Moore and Loewenstein 2004 ). Biases such as rationalization ( Davis et al. 2007 ; DuBois et al. 2015a ), tunnel vision ( Posavac et al. 2010 ), self-preservation ( Bandura et al. 1996 ; Oreg and Bayazit 2009 ), rigorous adherence to the status-quo ( Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988 ), and diffusion of responsibility ( Voelpel et al. 2008 ) may contribute to flawed decision-making on the part of professionals.

To illustrate, a researcher may cut corners during the informed consent process as they think to themselves, “nobody reads consent forms anyway” (i.e., assuming the worst) ( DuBois et al. 2015a ). In yet another example, a researcher may decide to drop outliers from a dataset without reporting it as they think to themselves, “it’s not like I fabricated any data” (i.e., euphemistic comparison). Both of these examples depict poor professionalism. These biased behaviors may occur subconsciously or be actively justified by an individual as in the cases above ( DuBois et al. 2015a ). Regardless, the characters in these examples failed to utilize professional decision-making strategies that could have helped inoculate against the effects of detrimental self-serving biases.

While professional decision-making requires a certain degree of objective and rational thought in order to be successful, professionals are not always rational and objective in their approach to making decisions ( Kahneman et al. 2011 ; Tenbrunsel et al. 2010 ). It is easy to see how heightened emotions could undermine professional decision-making, for example, when working long hours, applying for intensely competitive grant funding, dealing with a difficult colleague, or trying to impress a world-famous and notably erudite senior faculty member. Stress, negative emotions, or intense emotions left unregulated or unacknowledged have been shown to lessen the cognitive resources needed for effective professional decision-making ( Gino et al. 2011 ; Haidt 2001 ; Mead et al. 2009 ). When cognitive resources are depleted, reasoning is impaired and individuals tend to make hasty, biased decisions ( Angie et al. 2011 ; Bazerman and Moore 2013 ; Gross 2013 ). Professional decision-making strategies can help counteract these effects.

SMART Strategies

Despite obstacles to effective professional decision-making, certain compensatory strategies exist that enable professionals to help offset these obstacles. Taking a structured approach to making these decisions can help professionals effectively apply strategies that guide ethical decision-making, bias management, and quality information processing ( Bornstein and Emler 2001 ; DuBois et al. 2018 ; Thiel et al. 2012 ). Furthermore, this systematized thought process balances the aforementioned constraints that can negatively influence professional decision-making ( DuBois et al. 2015b ).

Building on the sensemaking work of Mumford ( Mumford et al. 2008 ) and the bias reduction work of Gibbs ( Gibbs et al. 1995 ), DuBois and his colleagues ( DuBois 2014 ; DuBois et al. 2015b ) in the Professionalism and Integrity in Research Program (P.I. Program) developed a structured decision-making aid to help professionals remember and recall a comprehensive set of compensatory strategies. Strategy-based training has proven to be effective in developing cognitive skills ( Clapham 1997 ), and has met success in increasing professional decision-making in the P.I. Program ( DuBois et al. 2018 ). These strategies shape professional decision-making and help professionals work through ethical dilemmas. Professional decision-making strategies comprise the acronym “SMART”, and encompass five domains: Seek help, Manage emotions, Anticipate consequences, Recognize rules and context, and Test assumptions and motives. Table 1 depicts key dimensions of each strategy and reflection questions that can be used to apply each strategy. While these strategies have distinct components, they are related to one another and conceptually overlap. Each professional decision-making strategy is described in detail below.

SMART strategies

| Strategy | Dimensions | Reflection Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Help | ||

| your Emotions | ||

| Consequences | ||

| Rules and Context | ||

| your Assumptions and Motives |

Seeking Help

This strategy is characterized by 1) gathering information such as facts, options, and potential outcomes, 2) requesting the mediation of an objective third party, and 3) asking for and welcoming feedback and correction. By deliberately processing context-relevant information and consulting with objective others, it is possible to correct for biases and challenge initial assumptions ( Sonenshein 2007 ). This allows the information that may have been formerly disregarded or misconstrued to be revealed and utilized effectively ( Mumford et al. 2008 ). When attempting to apply this strategy, professionals should reflect on questions such as, “Do I welcome feedback or input from others?”, “Where could I seek additional unbiased, objective information or opinions?”, or “Have I owned up to mistakes and apologized to all involved to move forward?”

Managing Emotions

The strategy of managing stress and emotion is characterized by 1) identifying the emotions being experienced, 2) managing those emotions, and 3) acknowledging both positive and negative emotions such as excitement and anxiety. When attempting to apply this strategy, professionals should ask themselves questions such as, “What are my emotional reactions to this situation?”, “How are my emotions influencing my decision-making?”, “Would taking a timeout or a deep breath help the situation?”

Anticipating Consequences

The strategy of anticipating consequences is characterized by 1) anticipating consequences to both oneself and others, 2) anticipating both long-term and short-term consequences, 3) anticipating both positive and negative consequences, 4) considering formal and informal responses, and 5) managing and mitigating risk. When attempting to apply this strategy, professionals should reflect on questions such as, “What are the likely short- and long-term outcomes of a variety of choices?”, “Who will be affected by my decisions and how?” and “How can risks be minimized and benefits be maximized?”

Recognizing Rules and Context

This strategy is characterized by 1) recognizing formal rules, such as laws and policies, 2) recognizing informal rules, such as social norms, and 3) recognizing the power dynamics of individuals involved in a given situation. Professionals attempting to apply this strategy should ask themselves, “What are the causes of the problem in this situation that I can change?”, “What ethical principles, laws, or regulations apply in this situation?”, and “Who are the decision-makers in this situation?”

Testing Assumptions and Motives

This strategy is characterized by 1) addressing the possibility you might be making faulty assumptions, 2) examining your motives compared to the motives of others, and 3) comparing your assumptions and motives with those of others in an empathetic manner. When attempting to apply this strategy, professionals should reflect on questions such as, “Could I be making faulty assumptions about the intentions of others?”, “What are my motives?”, and “How will others view my choices?”

Not only have compensatory strategies been demonstrated to be a helpful tool for high-quality professional decision-making, but these strategies are also learnable, trainable, and applicable to a wide variety of challenges and situations ( DuBois et al. 2015b ; Kligyte et al. 2008 ). The generalizability of strategies is noteworthy because they apply across contexts (e.g., human subjects research, animal research, translational research) and challenges faced by professionals (e.g., compliance, personnel management, integrity, bias). Moreover, these compensatory strategies, when applied correctly, can facilitate more critical analysis of a problem, improve information gathering and information evaluation, and contribute to better decision-making that leads individuals to make more professional and ethical decisions ( DuBois et al. 2015b ; Thiel et al. 2012 ).

Compensatory Strategy Case Application

Below we present a case with an ethical, professional dilemma and discuss how each SMART strategy can be properly applied in this example. We then caution against flawed application of these SMART strategies and highlight potential pitfalls to effective strategy application. It should be noted that, while the main character in the following case is a research assistant, applying the SMART strategies is a skill that can be learned and utilized by individuals across career stages and professions. The dilemma is as follows:

Sara is a new research assistant in the social science lab of Dr Jackson. She recently emigrated from China. Knowing that Sara is great with quantitative data analysis, Dr. Jackson asked her to run some statistics on data gathered by other research assistants on a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant that Dr. Jackson received two years ago. She ran the statistics, but none of Dr. Jackson’s hypotheses were confirmed. She thinks the study was simply under-powered. When she speaks with Dr. Jackson, he tells her she is mistaken and he asks her to run the tests again. She does so with the same results as before. This time, Dr. Jackson is angry, calls her incompetent, and says he will give her one more chance before he hires a new research assistant to run the statistics. Sara is fearful that she will lose her student visa if she loses her funded position. She drops several outliers and changes the data for several subjects and produces results that Dr. Jackson likes very much.

The above illustration is a great teaching case because, at first glance, Sara appears to be a victim: Dr. Jackson did not help her to do good work; rather, he bullied her to get the results he wanted. At the same time, the case perfectly illustrates a failure to use good decision-making strategies in a stressful situation with competing interests where few good options readily present themselves. Sara made a very bad decision: she committed research misconduct through her data falsification, the project was federally-funded, and now she and her institution could be prosecuted for this federal crime. While not every difficult situation requires the use of every one of the SMART strategies, Sara may have benefited from using each of them.

Sara could have asked other research assistants, graduate students, or postdocs for help with addressing problems with analyses and strategies for approaching and communicating with Dr. Jackson. If issues with Dr. Jackson had been persistent overtime, Sara could have sought support from colleagues or other faculty members who could provide advice for navigating the troubling work relationship. Ideally, the environment in the department would allow Sara to feel comfortable approaching another faculty member or others for help. Sara could have referred to objective field standards for conducting the analyses and determining how to proceed after unsuccessful analyses. After conducting the initial analyses, Sara could have asked a member in her lab to re-run the analyses with her in attempt to address any potential mistakes. Doing so may have affirmed her initial findings and assuaged concerns that she had approached the analyses incorrectly. Sara could have involved a mediator, such as a university ombudsperson, to help find a viable solution if she was unable to do so after exhausting the aforementioned options. A more complete picture presents itself after seeking help and additional information, and more ethical and professional courses of action become more apparent.

Because of the threat the situation poses to Sara’s personal and professional goals, emotions run high in this scenario. Sara wishes to be successful in her career and education, maintain her position in the United States, and earn Dr. Jackson’s approval. Sara is also likely aware that Dr. Jackson wishes to maintain a successful reputation in his field, publish interesting findings, and be productive throughout his career. She should introspectively identify her emotional reactions of anxiety, fear, frustration, and stress. When Sara was chastised by Dr. Jackson, she could have taken a “time out” to calm down and acknowledge how her emotions could override taking a more rational approach to addressing the problem instead of hastily reacting to Dr. Jackson’s response. At a broader level, taking time to manage stress each day would help Sara cope with the pressures and day-to-day stressors of her work. By identifying and managing the range of emotions experienced when faced with ethical and professional situations, clearer and more thoughtful judgment is likely to result.

Considering both the long-term and short-term consequences for all possible individuals is central to making a quality professional and ethical decision. Specifically, Sara should consider how falsifying data could end up negatively impacting not only her career trajectory and her immediate ability to work in the United States, but the careers and reputations of Dr. Jackson, her fellow lab mates, and the university where she works. Data falsification also undermines public trust in the field and scientific enterprise more broadly. In addition to attempting to minimize risk, Sara could have also considered how to maximize the benefits of, or make the best of, the situation. Perhaps by addressing the limitations of the analytical approach and bringing the analysis issue to light, a learning opportunity for everyone in the lab could have presented itself, paving the way for smoother management of similar situations in the future. Forecasting downstream consequences for all individuals that could be impacted by a given course of action is essential to maximizing benefits and minimizing harm to oneself and others.

Taking time to identify formal laws and policies and informal professional and social norms will help elucidate the context in which an ethical or professional dilemma unfolds. Sara could have identified the causes of problems and tensions in the situation, including publication pressures, Sara being new to the job, job stressors, and the like. By doing so, she could have more concretely comprehended the factors that limit her choices and could have avoided tunnel vision or narrow-mindedness in approaching the problem. Sara could have taken time to reflect on relevant ethical principles and regulations as they relate to falsifying data. Doing so may have cued her to not manipulate the data to obtain certain findings.

For better or worse, Dr. Jackson is her supervisor, and she must figure out a way to navigate the interpersonal problem in the case: He is upset and has threatened to fire her. Some of the strategies described above under “Seeking Help” might assist her in navigating the political dimension of this situation. Additionally, if these strategies fail, she should recognize that Dr. Jackson’s lab is situated within a larger institutional context. She could have reached out to other individuals within the university (e.g., department chair, research integrity officer) who prioritize responsible research and mentoring after exhausting alternative courses of action. These individuals, in turn, could have provided support and helped Sara navigate a path forward. Realizing the entirety of the context opens up a wider realm of options in navigating this challenging and threatening situation.

Understanding the motives of oneself and others provides the opportunity to consider multiple perspectives and take steps to avoid biased decision-making. While it can be challenging when one feels affronted, it can be helpful to consider the perspective and motives of other parties in the situation. For example, Sara could have considered whether Dr. Jackson was having a stressful day and overreacted when she initially approached him. She could have better managed self-serving and self-protecting biases perpetuated by her fear of not being allowed to work in Dr. Jackson’s lab by acknowledging how they may be distorting her perception of the situation. Sara might have questioned whether her analysis was correct; perhaps she did make an error and the study was not underpowered. That is, Sara should have questioned her assumption that, if she did conduct the analyses correctly, falsifying data was the only available option that would allow her to keep her position. Seldom is professional decision-making served well by engaging in simplistic either-or thinking. It is likely that multiple alternate courses of action would have presented themselves if she had engaged these strategies. Being proactive in managing biases by engaging in self-reflection and considering the perspectives and motives of others is beneficial to quality professional decision-making.

Questioning one’s assumptions is also a classic emotion management strategy used in cognitive behavioral therapy. Sometimes just realizing that we are making assumptions about how others perceive the situation and about our limited options can relieve anxiety.

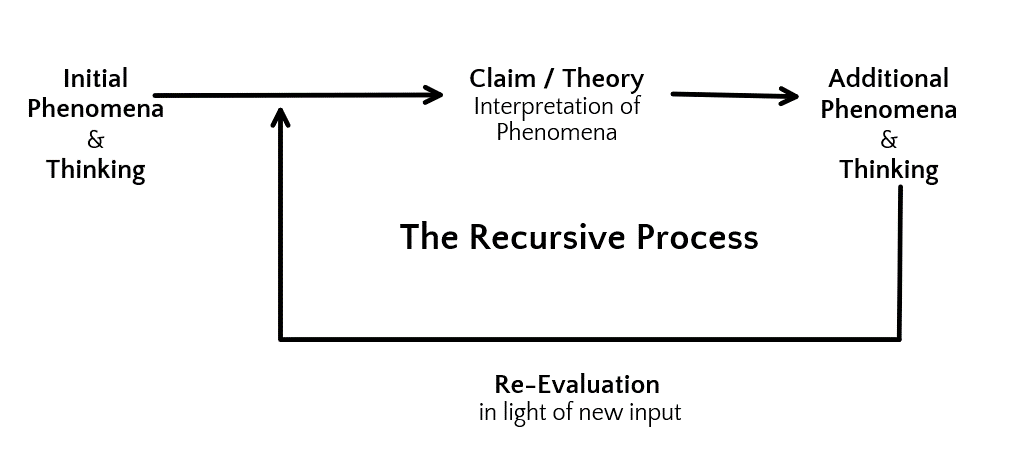

Evaluate and Revise

If one wishes to take these strategies a step further to engage in “SMART-ER” professional decision-making, they can: 1) Evaluate their decision and its outcomes and 2) Revise future behavior in similar situations. By acknowledging what did and did not work well in past situations and attempts at strategy use, modified and improved approaches to professional decision-making can be taken when faced with other professional and ethical challenges in the future.

Considerations for Applying SMART Strategies

While the SMART strategies are an excellent tool for professional decision-making, it is equally important to recognize the several important considerations when utilizing this approach. While a five-part decision-making aid has the opportunity to be highly useful for navigating complex, ambiguous professional situations, it is not a perfect algorithm or panacea for all ethical and professional conundrums. Given situational limitations and available contextual information, it may not always be possible to use each strategy fully, and challenges navigating the problem will still exist. Not all strategies will be equally applicable across all situations and may not be applied in the same order in all situations. However, SMART strategies are generalizable to myriad contexts, professions, and dilemmas and are not limited to major ethical transgressions such as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism.

An additional consideration for using SMART strategies is that people may have a preference for or tendency to use one strategy over the others. While the SMART strategies are interrelated, over-attending to one strategy may result in biased or incomplete information gathering and information processing and, ultimately, sub-optimal professional decisions. When individuals face emotional, stressful, or ethically-charged situations, it is important that they consider and use multiple strategies to inform well-rounded decision-making. When educating trainees on SMART strategies, educators should encourage trainees to use a balanced approach and consider multiple strategies.

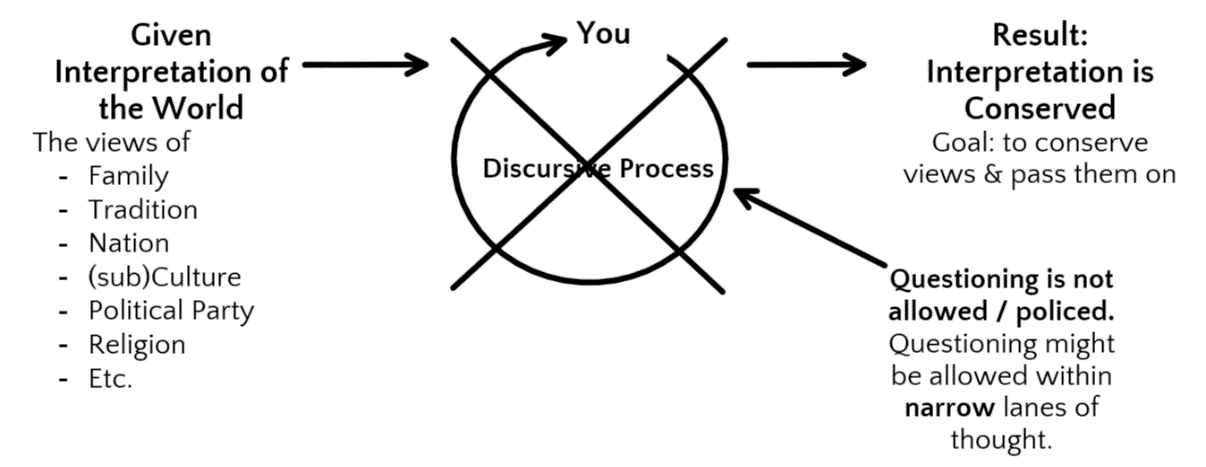

Perhaps one of the most considerable challenges educators may encounter is motivating trainees to use these compensatory strategies regularly. Simply teaching the strategies does not guarantee constructive application of strategies. In situations where individuals are overconfident or rushed to solve a problem that needs to be resolved quickly, immediately turning to the SMART strategies is unlikely to be an automatic course of action. Furthermore, if individuals engage in cognitive distortions in such a way that disengages from compliance or harms quality professional decision-making, they may fail to see the need or utility of SMART strategies ( DuBois et al. 2015a ). Educators should make professionals aware of how they might fall prey to these pitfalls.

A final consideration is that other mechanisms exist aside from training professionals to use SMART strategies that reinforce the recall and application of professional decision-making strategies. Such mechanisms include creating ethical and supportive organizational and departmental cultures, developing and enacting ethical leadership and management practices, and establishing institutional policies and procedures that reinforce the use of professional decision-making strategies.

Training SMART Strategies

Below, we examine practices that are useful in conducting professional decision-making training programs and creating pedagogical tools that can be implemented by a research ethics or professionalism course instructor. We focus on training practices designed for adult learners that support their professional growth and advancement ( Knowles et al. 2012 ). This is not an exhaustive list of considerations for designing and planning for an ethics or professionalism training program, and a systematic approach should be taken when developing any instructional program ( Antes 2014 ; Antes and DuBois 2014 ). Rather, the pedagogical practices described below were selected because of their implications for the transfer of complex skills, such as professional decision-making, to the workplace after training has occurred. That is, facilitating trainee learning, retention, and application of the content learned during training is essential to improving professional decision-making and making the training successful ( Noe 2013 ).

SMART Training Program Practices

Establish learning objectives.

Prior to presenting training content, provide trainees with stated objectives of the training program that define the expected outcomes of training and what it is they will be expected to accomplish as a result of completing the training ( Moore et al. 2008 ). Doing so alerts trainees to what is important and helps consolidate learning. Learning objectives have three components: 1) a statement of expected performance standard or outcome, 2) a statement of the quality or level of expected performance, and 3) a statement of the conditions when a trainee is expected to perform the skill learned in training ( Mager 1997 ). An example learning objective for a professional decision-making, or “SMART” strategies-focused, training is: Trainees will be able to apply professional decision-making strategies when they are faced with uncertain, complex, and high-stakes professional and ethical decisions in the workplace.

Create Meaningful Content

Explaining to trainees how a SMART strategies-focused training will directly benefit them and describing how training content is specifically linked to experiences in their profession will help garner buy-in from trainees ( Smith-Jentsch et al. 1996 ). Trainee dedication to achieving learning objectives is essential for learning and retention to occur and for transferring knowledge and skills to the work environment ( Goldstein and Ford 2002 ; Slavin 1990 ). To demonstrate the benefits of training, the content of training needs to be practically useful and applicable. This includes presenting content that is relevant to trainees’ professions and that addresses ethical and professional issues they have faced or are likely to face in their careers. Discussing a case or critical incident that the trainees have encountered, or something similar to what they have encountered, is an effective way to get them engaged with and derive meaning from training content.

Engage Multiple Pedagogical Activities

Pedagogical activities that occur during training reinforce key training concepts, help trainees derive meaning from training content, and facilitate active learning of professional decision-making skills. How trainees learn is equally as important as what trainees learn during training. Integrating case studies, individual reflection activities, think-pair-share exercises, and role plays into training fosters learning more than a traditional lecture format ( Bransford et al. 1999 ; DuBois 2013 ; Handelsman et al. 2004 ). These pedagogical activities vary in terms of their complexity and length, resulting in dynamic training content. Engaging trainees with these activities provides them with the opportunity to examine and connect their existing knowledge, experiences, and perspectives to the learning material. Table 2 provides a brief overview of how to implement various pedagogical activities, along with estimated level of complexity and duration.

Pedagogical activities

| Activity | Activity implementation | Complexity level | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Studies | Moderate complexity | Moderate to long (5 to 30 min) | |

| Individual Reflection | Low complexity | Short (1 to 5 min) | |

| Think-pair-share | Moderate complexity | Moderate (5 to 10 min) | |

| Role Plays | High complexity | Moderate to long (5 to 30 min) |

Case Studies

Applied to professionalism and research, case-based learning consists of using factual or fictional scenarios to illustrate examples of complex and ambiguous ethical and professional situations researchers may face ( Bagdasarov et al. 2013 ; Johnson et al. 2012 ; Kolodner 1992 ). Case-based learning helps trainees link course concepts to realistic, real-world scenarios by immersing themselves in these scenarios and exploring how to apply professional decision-making strategies ( Miller and Tanner 2015 ). The positive effects of case-based learning are magnified when trainees work together in small groups to collectively seek out important information, ask relevant questions, and find solutions to the problem ( Allen and Tanner 2002a ). This enables greater breadth and depth of understanding of decision-making strategies that can be used to address issues related to the case. Trainees can also use what they learned during this practice when applying these decision-making skills to a situation in the future that is similar. That is, trainees can draw upon their case-based knowledge to make sense of future professional and ethical situations and navigate these situations when they arise ( Kolodner et al. 2004 ).

Individual Reflection

Because of the personal and interpersonal nature of ethical and professional problems, reflecting on personal experiences and processing cases individually reinforces the knowledge base that influences ethical and professional decision-making ( Antes et al. 2012 ). Moreover, when professionals are confronted with ethical dilemmas, they are likely to draw upon personal experiences to make sense of the dilemma and generate solutions ( Mumford et al. 2000 ; Scott et al. 2005 ; Thiel et al. 2012 ). Drawing on past experiences allows professionals to consider important aspects of these past experiences such as causes and outcomes, which are essential for effective professional decision-making ( Stenmark et al. 2010 ).

Think-Pair-Share

Think-pair-share activities consist of having students initially think about a solution to a problem individually, then pairing with a neighboring student to exchange ideas, and finally reporting out to the larger group key points from their discussion ( Allen and Tanner 2002b ). Discussion between peers enhances understanding of complex subject matter even when both trainees are uncertain initially ( Smith et al. 2009 ). This may be due to the cognitive reasoning and communication skills needed to relay and justify perspectives about complex subject matter to others. Conversely, similar evaluative skills are needed to appraise the viewpoints of the other and determine if their explanation and rationale make sense in context.

Role plays are training activities where trainees take on the role of someone in a hypothetical scenario and model what it is like to have the perspective of that character ( Thiagarajan 1996 ). For example, trainees in a role play can model social interactions between characters faced with an ethical or professional dilemma regarding authorship, human subjects protections, mentor-trainee relationships, or data management ( DuBois 2013 ). Role plays enable trainees to learn how to identify, analyze, and resolve these dilemmas because they provide trainees with the opportunity to practice navigating these situations ( Chan 2012 ; DuBois 2013 ). This technique is particularly effective in trainings that involve exploration and acquisition of complex social skills, such as professional decision-making ( Noe 2013 ). Role play activities have been shown to be effective in ethics instruction ( Mumford et al. 2008 ). They can involve a select few volunteers who perform for the class while the remainder of trainees observe, or involve all trainees divided into small groups of two or three where all trainees take part in the role play activity. Role play activities have been shown to promote a deep understanding of the complexities involved with ethical and professional dilemmas ( Brummel et al. 2010 ).

In order to be effective, however, certain activities must take place before, during, and after the role play ( Noe 2013 ; Thiagarajan 1996 ). Specifically, before the role play, trainees should be provided with background information that gives context for the role play and a script with adequate detail for trainees to understand their role. During the role play, actors and observers should be able to hear and see one another, and trainees should be provided with a handout detailing the key issues of the role play scenario. After the role play has commenced, both actors and observers should debrief on their experience, how the role play relates to the concepts being taught in training, and key takeaways. Trainees should also be provided with feedback in order to reinforce what was learned during the role play experience ( Jackson and Back 2011 ).

Provide Practice Opportunities

Trainees will need multiple opportunities to practice applying the professional decision-making skills they are learning. Practice opportunities can take the form of the various pedagogical tools, as discussed above, including case studies, individual reflection, and role-play activities. These tools promote active learning and create a safe mechanism for trainees to experiment with SMART strategy application ( Bell and Kozlowski 2008 ). Instructors should also have trainees periodically recall the SMART strategies throughout training. This active recall will increase the likelihood of strategy use beyond practice during training.

Give Feedback

Immediately after each practice activity, instructors should provide feedback to trainees by noting what was done well and where there are opportunities for change or improvement. Feedback should be specific and frequent in order to convey to trainees what resulted in poor professional decision-making performance and good professional decision-making performance ( Gagné and Medsker 1996 ). Carefully guiding feedback-oriented discussions can further enhance learning, retention, and application of SMART strategies.

Professionals across various fields, especially in research contexts, encounter complex situations involving multiple stakeholders that necessitate professional decision-making skills. Fortunately, these skills are trainable, and the SMART strategies decision tool helps facilitate professional decision-making skill retention and application. In the present effort, we approach professional decision-making using a compensatory strategy framework and showcase how each of the SMART strategies could be applied to a scenario involving a professional dilemma. We also discuss how to maximize the effects of a SMART strategy-oriented training program and highlight pedagogical tools to guide SMART strategy education.

This paper provides a guide for educators and institutions with the goal of integrating training on professional decision-making skills into their curriculum. We provide educators with a robust understanding of the steps involved in mitigating negative effects of self-serving biases and making sense of complex professional dilemmas. Additionally, we discuss the individual-level and environmental-level constraints that influence the way problems are framed and approached, and the strategies that individuals can use to counteract the negative effects of these constraints on decision-making. Educators can take this understanding, along with the knowledge of effective training and pedagogical practices, to create training content that prepares its trainees to effectively navigate multifaceted professional issues they may face in their careers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank John Gibbs, John Chibnall, Raymond Tait, Michael Mumford, Shane Connelly, and Lynn Devenport for their insight and prior work that led to many of the ideas discussed in this manuscript.

Funding/Support This paper was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR002345). The development of the Professionalism and Integrity in Research Program (PI) was funded by a supplement to the Washington University Clinical and Translational Science award (UL1 TR000448). The U.S. Office of Research Integrity provided funding to conduct outcome assessment of the PI Program (ORIIR140007). The effort of ALA was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (K01HG008990).

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

- Allen D, & Tanner K (2002a). Answers worth waiting for: One second is hardly enough . Cell Biology Education , 1 , 3–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen D, & Tanner K (2002b). Approaches to cell biology teaching: Questions about questions . Cell Biology Education , 1 , 63–67. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson MS, Horn AS, Risbey KR, Ronning EA, De Vries R, & Martinson BC (2007). What do mentoring and training in the responsible conduct of research have to do with scientists' misbehavior? Findings from a National Survey of NIH-funded scientists . Academic Medicine: Journal of The Association of American Medical Colleges , 82 , 853–860. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31812f764c. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Angie AD, Connelly S, Waples EP, & Kligyte V (2011). The influence of discrete emotions on judgement and decision-making: A meta-analytic review . Cognition & Emotion , 25 , 1393–1422. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antes AL (2013). An ethics instructor’s guide to sensemaking as a framework for case-based learning (Vol. 1 ): Office of Research Integrity. [ Google Scholar ]

- Antes AL (2014). A systematic approach to instruction in research ethics . Accountability in Research: Policies and Quality Assurance , 21 , 50–67. 10.1080/08989621.2013.822269. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antes AL, & DuBois JM (2014). Aligning objectives and assessment in responsible conduct of research instruction . Journal Of Microbiology & Biology Education , 15 , 108–116. 10.1128/jmbe.v15i2.852. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antes AL, Wang X, Mumford MD, Brown RP, Connelly S, & Devenport L (2010). Evaluating the effects that existing instruction on responsible conduct of research has on ethical decision making . Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges , 85 , 519–526. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antes AL, Thiel CE, Martin LE, Stenmark CK, Connelly S, Devenport LD, & Mumford MD (2012). Applying cases to solve ethical problems: The significance of positive and process-oriented reflection . Ethics & Behavior , 22 , 113–130. 10.1080/10508422.2012.655646. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antes AL, English T, Baldwin KA, & DuBois JM (2017). The role of culture and acculturation in researchers' perceptions of rules in science . Science and Engineering Ethics , 24 , 1–31. 10.1007/s11948-017-9876-4. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bagdasarov Z, Thiel CE, Johnson JF, Connelly S, Harkrider LN, Devenport LD, & Mumford MD (2013). Case-based ethics instruction: The influence of contextual and individual factors in case content on ethical decision-making . Science and Engineering Ethics , 19 , 1305–1322. 10.1007/s11948-012-9414-3. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, & Caprara GV (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 71 , 364–374. 10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.125. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bazerman MH, & Moore DA (2013). Judgment in managerial decision making (8th ed.). New York: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bell BS, & Kozlowski SW (2008). Active learning: Effects of core training design elements on self-regulatory processes, learning, and adaptability . Journal of Applied Psychology , 93 , 296–316. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bornstein BH, & Emler AC (2001). Rationality in medical decision making: A review of the literature on doctors’ decision-making biases . Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice , 7 , 97–107. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bransford JD, Brown A, & Cocking R (1999). How people learn: Mind, brain, experience, and school . Washington, DC: National Research Council. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brummel BJ, Gunsalus C, Anderson KL, & Loui MC (2010). Development of role-play scenarios for teaching responsible conduct of research . Science and Engineering Ethics , 16 , 573–589. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chan ZC (2012). Role-playing in the problem-based learning class . Nurse Education in Practice , 12 , 21–27. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clapham MM (1997). Ideational skills training: A key element in creativity training programs . Creativity Research Journal , 10 , 33–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dana J, & Loewenstein G (2003). A social science perspective on gifts to physicians from industry . Journal of the American Medical Association , 290 , 252–255. 10.1001/jama.290.2.252. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis MS, Riske-Morris M, & Diaz SR (2007). Causal factors implicated in research misconduct: Evidence from ORI case files . Science and Engineering Ethics , 13 , 395–414. 10.1007/s11948-007-9045-2. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DuBois JM (2008a). Identifying and managing conflicts of interest. In Ethics in mental health research: Principles, guidance, and cases (1st ed., pp. 202–224). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- DuBois JM (2008b). Solving ethical problems: Analyzing ethics cases and justifying decisions : New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- DuBois JM (2013). ORI casebook: Stories about researchers worth discussing .

- DuBois JM (2014). Strategies for professional decision making: The SMART approach . St. Louis: Professionalism and Integrity in Research Progra. [ Google Scholar ]

- DuBois JM, Chibnall JT, & Gibbs JC (2015a). Compliance disengagement in research: Development and validation of a new measure . Science and Engineering Ethics , 22 , 965–988. 10.1007/s11948-015-9681-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DuBois JM, Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Vander Wal JS, Baldwin KA, Antes AL, & Mumford MD (2015b). Professional decision-making in research (PDR): The validity of a new measure . Science and Engineering Ethics , 22 , 391–416. 10.1007/s11948-015-9667-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DuBois JM, Chibnall JT, Tait RC, & Vander Wal JS (2016). Lessons from researcher rehab . Nature , 534 , 173–175. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DuBois JM, Chibnall JT, Tait RC, & Vander Wal JS (2018). The professionalism and integrity in research program: Description and preliminary outcomes . Academic Medicine , 93 , 586–592. 10.1097/acm.0000000000001804. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gagné RM, & Medsker KL (1996). The conditions of learning: Training applications . Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt-Brace. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibbs JC, Potter G, & Goldstein A (1995). The EQUIP program: Teaching youth to think and act responsibly . Champaign, IL: Research Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gino F, Schweitzer ME, Mead NL, & Ariely D (2011). Unable to resist temptation: How self-control depletion promotes unethical behavior . Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 115 , 191–203. 10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.03.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldstein IL, & Ford KJ (2002). Training in organizations: Needs assessment, development, and evaluation (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodwin P, Wright G, & Phillips LD (1998). Decision analysis for management judgment . Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gross JJ (2013). Emotion regulation: Taking stock and moving forward . Emotion , 13 , 359–365. 10.1037/a0032135. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haidt J (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment . Psychological Review , 108 , 814–834. 10.1037//0033-295x.108.4.814. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hammond JS, Keeney RL, & Raiffa H (1998). The hidden traps in decision making . Harvard Business Review , 76 , 47–58. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Handelsman J, Ebert-May D, Beichner R, Bruns P, Chang A, DeHaan R, Gentile J, Lauffer S, Stewart J, Tilghman S, & Wood W (2004). Scientific teaching . Science , 304 , 521–522. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoch, Kunreuther H, & Gunther R (2001). Wharton on making decisions . New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. [ Google Scholar ]

- Irwin RS (2009). The role of conflict of interest in reporting of scientific information . Chest , 136 , 253–259. 10.1378/chest.09-0890. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jackson VA,& Back AL (2011). Teaching communication skills using role-play: An experience-based guide for educators . Journal of Palliative Medicine , 14 , 775–780. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jahnke LM, & Asher A (2014). The problem of data: Data management and curation practices among university researchers . In Council on Library and Information Resources Retrieved from http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub154/problem-of-data . [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson JF, Bagdasarov Z, Connelly S, Harkrider LN, Devenport LD, Mumford MD, & Thiel CE (2012). Case-based ethics education: The impact of cause complexity and outcome favorability on ethicality . Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics , 7 , 63–77. 10.1525/jer.2012.7.3.63. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahneman D (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice - mapping bounded rationality . American Psychologist , 58 , 697–720.i 10.1037/0003-066x.58.9.697. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahneman D, Lovallo D, & Sibony O (2011). Before You Make That Big Decision … Harvard Business Review , 89 , 50–60. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000290694700034. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kligyte V, Marcy RT, Waples EP, Sevier ST, Godfrey ES, Mumford MD, & Hougen DF (2008). Application of a sensemaking approach to ethics training in the physical sciences and engineering . Science and Engineering Ethics , 14 , 251–278. 10.1007/s11948-007-9048-z. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Knowles MS, Holton III EF, & Swanson RA (2012). The adult learner (7th ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kolodner JL (1992). An introduction to case-based reasoning . Artificial Intelligence Review , 6 , 3–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kolodner JL, Owensby JN, & Guzdial M (2004). Case-based learning aids . Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology , 2 , 829–861. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mager RF (1997). Preparing instructional objectives (5th ed. ed.). Belmont: Lake Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mead NL, Baumeister RF, Gino F, Schweitzer ME, & Ariely D (2009). Too tired to tell the truth: Self-control resource depletion and dishonesty . Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 45 , 594–597. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller S, & Tanner KD (2015). A portal into biology education: An annotated list of commonly encountered terms . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 14 , fe2. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore DA, & Loewenstein G (2004). Self-interest, automaticity, and the psychology of conflict of interest . Social Justice Research , 17 , 189–202. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore S, Ellsworth JB, & Kaufman R (2008). Objectives—Are they useful? A quick assessment . Performance Improvement Quarterly , 47 , 41–47. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mumford MD, Zaccaro SJ, Harding FD, Jacobs TO, & Fleishman EA (2000). Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems . The Leadership Quarterly , 11 , 11–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mumford MD, Friedrich TL, Caughron JJ, & Byrne CL (2007). Leader cognition in real-world settings: How do leaders think about crises? The Leadership Quarterly , 18 , 515–543. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mumford MD, Connelly S, Brown RP, Murphy ST, Hill JH, Antes AL, Waples EP, & Devenport LD (2008). A sensemaking approach to ethics training for scientists: Preliminary evidence of training effectiveness . Ethics & Behavior , 18 , 315–339. 10.1080/10508420802487815. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Noe RA (2013). Employee training and development (6th ed.): McGraw-Hill. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oliveira A (2007). A discussion of rational and psychological decision-making theories and models: The search for a cultural-ethical decision-making model . Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies , 12 , 12–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oreg S, & Bayazit M (2009). Prone to bias: Development of a bias taxonomy from an individual differences perspective . Review of General Psychology , 13 , 175–193. [ Google Scholar ]

- Palazzo G, Krings F, & Hoffrage U (2012). Ethical blindness . Journal of Business Ethics , 109 , 323–338. 10.1007/s10551-011-1130-4. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Posavac SS, Kardes FR, & Brakus JJ (2010). Focus induced tunnel vision in managerial judgment and decision making: The peril and the antidote . Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 113 , 102–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- Samuelson W, & Zeckhauser R (1988). Status quo bias in decision making . Journal of Risk and Uncertainty , 1 , 7–59. [ Google Scholar ]

- Scott GM, Lonergan DC, & Mumford MD (2005). Conceptual combination: Alternative knowledge structures, alternative heuristics . Creativity Research Journal , 17 , 79–98. [ Google Scholar ]

- Slavin RE (1990). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith MK, Wood WB, Adams WK, Wieman C, Knight JK, Guild N, & Su TT (2009). Why peer discussion improves student performance on in-class concept questions . Science , 323 , 122–124. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith-Jentsch KA, Jentsch FG, Payne SC, & Salas E (1996). Can pretraining experiences explain individual differences in learning? Journal of Applied Psychology , 81 , 110–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sonenshein S (2007). The role of construction, intuition, and justification in responding to ethical issues at work: The sensemaking-intuition model . Academy of Management Review , 32 , 1022–1040. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stenmark CK, Antes AL, Wang X, Caughron JJ, Thiel CE, & Mumford MD (2010). Strategies in forecasting outcomes in ethical decision-making: Identifying and analyzing the causes of the problem . Ethics & Behavior , 20 , 110–127. doi:Pii 920034165. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stenmark CK, Antes AL, Thiel CE, Caughron JJ, Wang XQ, & Mumford MD (2011). Consequences identification in forecasting and ethical decision-making . Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics , 6 , 25–32. 10.1525/jer.2011.6.1.25. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stern DT, & Papadakis M (2006). The developing physician—Becoming a professional . New England Journal of Medicine , 355 , 1794–1799. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Swick HM (2000). Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism . Academic Medicine , 75 , 612–616. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tenbrunsel AE, Diekmann KA, Wade-Benzoni KA, & Bazerman MH (2010). The ethical mirage: A temporal explanation as to why we are not as ethical as we think we are . Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews , 30 , 153–173. 10.1016/j.riob.2010.08.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thiagarajan S (1996). Instructional games, simulations, and role-plays. In Craig R (Ed.), The ASTD training and development handbook (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thiel CE, Bagdasarov Z, Harkrider LN, Johnson JF, & Mumford MD (2012). Leader ethical decision-making in organizations: Strategies for sensemaking . Journal of Business Ethics , 107 , 49–64. 10.1007/s10551-012-1299-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van Mook WNKA, van Luijk SJ, O'Sullivan H, Wass V, Harm Zwaveling J, Schuwirth LW, & van der Vleuten CP (2009). The concepts of professionalism and professional behaviour: Conflicts in both definition and learning outcomes . European Journal of International Medicine , 20 , e85–e89. 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Voelpel SC, Eckhoff RA, & Förster J (2008). David against goliath? Group size and bystander effects in virtual knowledge sharing . Human Relations , 61 , 271–295. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM, & Obstfeld D (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking . Organization Science , 16 , 409–421. 10.1287/orsc.1050.0133. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Werhane PH (2008). Mental models, moral imagination and system thinking in the age of globalization . Journal of Business Ethics , 78 , 463–474. [ Google Scholar ]

A Framework for Ethical Decision Making

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Ethics Resources

This document is designed as an introduction to thinking ethically. Read more about what the framework can (and cannot) do .

We all have an image of our better selves—of how we are when we act ethically or are “at our best.” We probably also have an image of what an ethical community, an ethical business, an ethical government, or an ethical society should be. Ethics really has to do with all these levels—acting ethically as individuals, creating ethical organizations and governments, and making our society as a whole more ethical in the way it treats everyone.

What is Ethics?

Ethics refers to standards and practices that tell us how human beings ought to act in the many situations in which they find themselves—as friends, parents, children, citizens, businesspeople, professionals, and so on. Ethics is also concerned with our character. It requires knowledge, skills, and habits.

It is helpful to identify what ethics is NOT:

- Ethics is not the same as feelings . Feelings do provide important information for our ethical choices. However, while some people have highly developed habits that make them feel bad when they do something wrong, others feel good even though they are doing something wrong. And, often, our feelings will tell us that it is uncomfortable to do the right thing if it is difficult.

- Ethics is not the same as religion . Many people are not religious but act ethically, and some religious people act unethically. Religious traditions can, however, develop and advocate for high ethical standards, such as the Golden Rule.

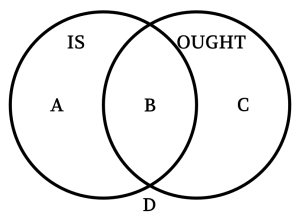

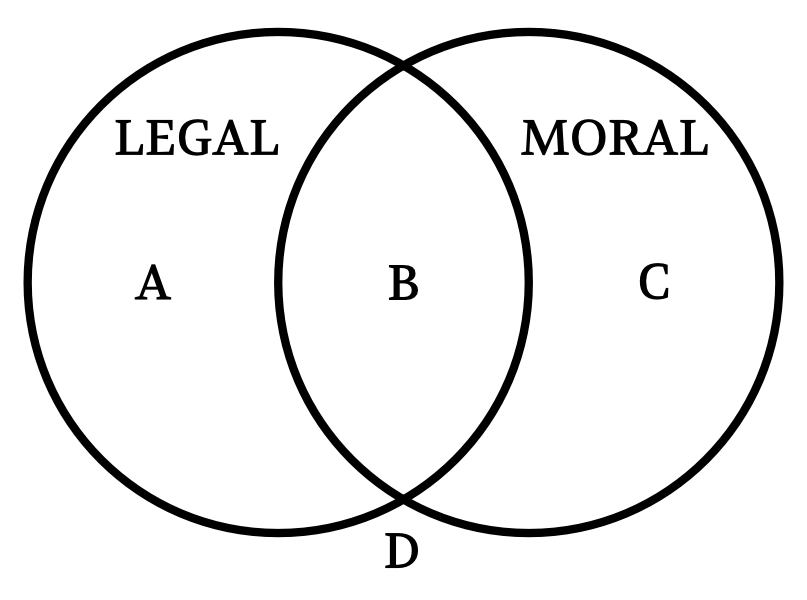

- Ethics is not the same thing as following the law. A good system of law does incorporate many ethical standards, but law can deviate from what is ethical. Law can become ethically corrupt—a function of power alone and designed to serve the interests of narrow groups. Law may also have a difficult time designing or enforcing standards in some important areas and may be slow to address new problems.

- Ethics is not the same as following culturally accepted norms . Cultures can include both ethical and unethical customs, expectations, and behaviors. While assessing norms, it is important to recognize how one’s ethical views can be limited by one’s own cultural perspective or background, alongside being culturally sensitive to others.

- Ethics is not science . Social and natural science can provide important data to help us make better and more informed ethical choices. But science alone does not tell us what we ought to do. Some things may be scientifically or technologically possible and yet unethical to develop and deploy.

Six Ethical Lenses

If our ethical decision-making is not solely based on feelings, religion, law, accepted social practice, or science, then on what basis can we decide between right and wrong, good and bad? Many philosophers, ethicists, and theologians have helped us answer this critical question. They have suggested a variety of different lenses that help us perceive ethical dimensions. Here are six of them:

The Rights Lens

Some suggest that the ethical action is the one that best protects and respects the moral rights of those affected. This approach starts from the belief that humans have a dignity based on their human nature per se or on their ability to choose freely what they do with their lives. On the basis of such dignity, they have a right to be treated as ends in themselves and not merely as means to other ends. The list of moral rights—including the rights to make one's own choices about what kind of life to lead, to be told the truth, not to be injured, to a degree of privacy, and so on—is widely debated; some argue that non-humans have rights, too. Rights are also often understood as implying duties—in particular, the duty to respect others' rights and dignity.

( For further elaboration on the rights lens, please see our essay, “Rights.” )

The Justice Lens

Justice is the idea that each person should be given their due, and what people are due is often interpreted as fair or equal treatment. Equal treatment implies that people should be treated as equals according to some defensible standard such as merit or need, but not necessarily that everyone should be treated in the exact same way in every respect. There are different types of justice that address what people are due in various contexts. These include social justice (structuring the basic institutions of society), distributive justice (distributing benefits and burdens), corrective justice (repairing past injustices), retributive justice (determining how to appropriately punish wrongdoers), and restorative or transformational justice (restoring relationships or transforming social structures as an alternative to criminal punishment).

( For further elaboration on the justice lens, please see our essay, “Justice and Fairness.” )

The Utilitarian Lens

Some ethicists begin by asking, “How will this action impact everyone affected?”—emphasizing the consequences of our actions. Utilitarianism, a results-based approach, says that the ethical action is the one that produces the greatest balance of good over harm for as many stakeholders as possible. It requires an accurate determination of the likelihood of a particular result and its impact. For example, the ethical corporate action, then, is the one that produces the greatest good and does the least harm for all who are affected—customers, employees, shareholders, the community, and the environment. Cost/benefit analysis is another consequentialist approach.

( For further elaboration on the utilitarian lens, please see our essay, “Calculating Consequences.” )

The Common Good Lens

According to the common good approach, life in community is a good in itself and our actions should contribute to that life. This approach suggests that the interlocking relationships of society are the basis of ethical reasoning and that respect and compassion for all others—especially the vulnerable—are requirements of such reasoning. This approach also calls attention to the common conditions that are important to the welfare of everyone—such as clean air and water, a system of laws, effective police and fire departments, health care, a public educational system, or even public recreational areas. Unlike the utilitarian lens, which sums up and aggregates goods for every individual, the common good lens highlights mutual concern for the shared interests of all members of a community.

( For further elaboration on the common good lens, please see our essay, “The Common Good.” )

The Virtue Lens

A very ancient approach to ethics argues that ethical actions ought to be consistent with certain ideal virtues that provide for the full development of our humanity. These virtues are dispositions and habits that enable us to act according to the highest potential of our character and on behalf of values like truth and beauty. Honesty, courage, compassion, generosity, tolerance, love, fidelity, integrity, fairness, self-control, and prudence are all examples of virtues. Virtue ethics asks of any action, “What kind of person will I become if I do this?” or “Is this action consistent with my acting at my best?”

( For further elaboration on the virtue lens, please see our essay, “Ethics and Virtue.” )

The Care Ethics Lens

Care ethics is rooted in relationships and in the need to listen and respond to individuals in their specific circumstances, rather than merely following rules or calculating utility. It privileges the flourishing of embodied individuals in their relationships and values interdependence, not just independence. It relies on empathy to gain a deep appreciation of the interest, feelings, and viewpoints of each stakeholder, employing care, kindness, compassion, generosity, and a concern for others to resolve ethical conflicts. Care ethics holds that options for resolution must account for the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders. Focusing on connecting intimate interpersonal duties to societal duties, an ethics of care might counsel, for example, a more holistic approach to public health policy that considers food security, transportation access, fair wages, housing support, and environmental protection alongside physical health.

( For further elaboration on the care ethics lens, please see our essay, “Care Ethics.” )

Using the Lenses

Each of the lenses introduced above helps us determine what standards of behavior and character traits can be considered right and good. There are still problems to be solved, however.

The first problem is that we may not agree on the content of some of these specific lenses. For example, we may not all agree on the same set of human and civil rights. We may not agree on what constitutes the common good. We may not even agree on what is a good and what is a harm.

The second problem is that the different lenses may lead to different answers to the question “What is ethical?” Nonetheless, each one gives us important insights in the process of deciding what is ethical in a particular circumstance.

Making Decisions

Making good ethical decisions requires a trained sensitivity to ethical issues and a practiced method for exploring the ethical aspects of a decision and weighing the considerations that should impact our choice of a course of action. Having a method for ethical decision-making is essential. When practiced regularly, the method becomes so familiar that we work through it automatically without consulting the specific steps.

The more novel and difficult the ethical choice we face, the more we need to rely on discussion and dialogue with others about the dilemma. Only by careful exploration of the problem, aided by the insights and different perspectives of others, can we make good ethical choices in such situations.

The following framework for ethical decision-making is intended to serve as a practical tool for exploring ethical dilemmas and identifying ethical courses of action.

Identify the Ethical Issues

- Could this decision or situation be damaging to someone or to some group, or unevenly beneficial to people? Does this decision involve a choice between a good and bad alternative, or perhaps between two “goods” or between two “bads”?

- Is this issue about more than solely what is legal or what is most efficient? If so, how?

Get the Facts

- What are the relevant facts of the case? What facts are not known? Can I learn more about the situation? Do I know enough to make a decision?

- What individuals and groups have an important stake in the outcome? Are the concerns of some of those individuals or groups more important? Why?

- What are the options for acting? Have all the relevant persons and groups been consulted? Have I identified creative options?

Evaluate Alternative Actions

- Evaluate the options by asking the following questions:

- Which option best respects the rights of all who have a stake? (The Rights Lens)

- Which option treats people fairly, giving them each what they are due? (The Justice Lens)

- Which option will produce the most good and do the least harm for as many stakeholders as possible? (The Utilitarian Lens)

- Which option best serves the community as a whole, not just some members? (The Common Good Lens)

- Which option leads me to act as the sort of person I want to be? (The Virtue Lens)

- Which option appropriately takes into account the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders? (The Care Ethics Lens)

Choose an Option for Action and Test It

- After an evaluation using all of these lenses, which option best addresses the situation?

- If I told someone I respect (or a public audience) which option I have chosen, what would they say?

- How can my decision be implemented with the greatest care and attention to the concerns of all stakeholders?

Implement Your Decision and Reflect on the Outcome

- How did my decision turn out, and what have I learned from this specific situation? What (if any) follow-up actions should I take?

This framework for thinking ethically is the product of dialogue and debate at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Primary contributors include Manuel Velasquez, Dennis Moberg, Michael J. Meyer, Thomas Shanks, Margaret R. McLean, David DeCosse, Claire André, Kirk O. Hanson, Irina Raicu, and Jonathan Kwan. It was last revised on November 5, 2021.

Navigating the Ethical Decision Making Process: A Guide for Ethical Dilemmas

Navigating Ethics in the Workplace

In our complex and interconnected world, individuals and organizations often face ethical dilemmas that require careful consideration and decision-making. The ethical decision making process is that involves analyzing and evaluating various options to make choices that align with moral principles and values. It serves as a moral compass, guiding us towards actions deemed right or good while helping us navigate challenging ethical situations.

Table of Contents

Understanding Ethical Dilemmas

Ethical dilemmas are situations where individuals or organizations face conflicting moral principles or values, making it difficult to determine the right course of action. These dilemmas often arise when there is a clash between different ethical considerations or when no clear-cut solution fully satisfies all parties involved.

Ethical dilemmas can emerge in various contexts, including personal relationships, professional settings, and societal issues. They can range from straightforward decisions with relatively low stakes to complex, morally ambiguous scenarios with far-reaching consequences.

To better understand ethical dilemmas, let’s explore some key aspects:

1. Conflicting Values: Ethical dilemmas often involve conflicting values or principles. For example, a healthcare professional may face a dilemma when the principle of patient autonomy conflicts with the duty to protect patient confidentiality.

2. Limited Resources: A scarcity of resources can give rise to ethical dilemmas. When resources are limited, individuals or organizations may face difficult choices in allocating those resources, leading to moral conflicts and challenges.

3. Multiple Stakeholders: Ethical dilemmas frequently involve multiple stakeholders with interests and perspectives. Balancing these interests and finding a solution that satisfies everyone can be extremely challenging.

4. Uncertainty and Complexity : Ethical dilemmas can arise when there is a lack of clear information, or the consequences of different choices are uncertain. The complexity of the situation further complicates the decision-making process.