REVIEW article

Participative leadership: a literature review and prospects for future research.

- 1 School of Economics and Management, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, China

- 2 College of Business Administration, Gachon University, Seongnam, South Korea

- 3 School of Management, Xi’an Polytechnic University, Xi’an, China

Changes in the external market environment put forward objective requirements for the formulation of organizational strategic plans, making it difficult for the organization’s leaders to make the right and effective decisions quickly on their own. As a result, participative leadership, which encourages and supports employees to participate in the decision-making process of organizations, has received increasing attention in both theory and practice. We searched the literature related to participative leadership in databases such as Web of Science, EBSCO, ProQuest, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Based on this, we clarify the concept of participative leadership, propose a definition of participative leadership, summarize measurement scales for this type of leadership, and compare participative leadership with other leadership styles (empowering leadership and directive leadership). We also present a research framework for participative leadership that demonstrates its antecedents; the mechanisms for its development based on social exchange theory, conservation of resources theory, social cognitive theory; social information processing theory, and implicit leadership theory; and outcomes. Finally, we identify five potential research areas: Connotation, antecedents, outcomes, mediators and moderators, and study of participative leadership in China.

Introduction

In the digital age, companies are actively taking accurate decisions such as using advanced technology to enhance their competitive advantage in the marketplace ( Su et al., 2021 ). But where do good measures and perfect solutions come from? The answer comes from the masses. With the dramatic changes in the competitive business environment, it is difficult for organizational leaders to make timely and effective decisions on their own, which has led to the active presence of employees in organizational decision-making today ( Peng et al., 2021 ). At the same time, due to the use of modern information technology such as computer networks and system integration, there is a bottom-up flow of information within the enterprise, and these cross-level, multi-dimensional “employee opinions” play an increasingly important role in leadership decision-making. Improving a company’s competitive advantage, sustainable development goal and performance is increasingly dependent on the active participation of the organization’s employees in decision-making ( Chang et al., 2021 ; Jia et al., 2021 ). In particular, Peter Drucker, the master of manageme, also considered that “encouraging employee involvement” is an important part of effective leadership in his influential study “Management by Objective.” In practice, some well-known companies have gradually started to call for employee participation behaviors in decision-making to varying degrees. For example, leaders in the R&D department of Volvo Cars actively use shared open rights and encourage diversity initiatives to promote employee participation in decision-making to facilitate organizational innovation ( Jing et al., 2017 ). It is easy to see that employee participation, a key component of organizational decision-making, is an important influencing factor for business organizations to adapt to the dynamic business environment and improve the effectiveness and science of leaders’ decisions. Therefore, it is an important issue that leaders need to focus on in real-time, especially in organizations with a high power distance culture, to promote the participation of their subordinates in organizational decision-making ( Huang et al., 2010 ). This requires leaders to adopt a supportive, democratic leadership style, known as participative leadership. A large number of scholars also agree that organizational leaders are increasingly relying on highly engaged employees to meet the challenges of a competitive marketplace, so participative leadership, which seeks to promote behaviors that support employee participation in organizational decision-making, is gaining attention in many organizations ( Huang et al., 2006 ). Participative leadership exists in organizations of any size, of any type and at any stage, where openness and empowerment of employees in the organizational decision-making process are core characteristics that distinguish it from other leadership styles ( Huang et al., 2021 ). When making strategic decisions, participative leaders are able to share decision-making power and fully consult employees to jointly deal with the work problems ( Chan, 2019 ).

In summary, participative leaders encourage and support employees to participate in the decision-making process in order to make effective organizational decisions and to solve work problems together through a range of measures ( Kahai et al., 1997 ). However, there is still much space for theoretical research on participative leadership, and the organizational practice with the current call for “employee participation in decision-making” needs to be optimised and improved, and there is an urgent need to balance the organizational practice and theoretical research on “employee participation” and “scientific decision-making” from the leadership level. In order to accelerate the exploration of participative leadership and promote the research on the effectiveness of participative leadership, we systematically review the literature on participative leadership, summarise and outline its concept, measurement scales and conceptual comparisons, antecedents, mechanisms and outcomes, and present future research perspectives.

Literature Collection

We searched the literature on participative leadership published in databases such as Web of Science, ProQuest, EBSCO, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). To perform the search, we used the keywords “participative leadership,” “participative management,” “participative behavior,” and “participative leader.” We also used a snowballing approach to identify relevant literature by searching the list of references we found in our research. Also, to better examine the similarities and differences in leadership styles in our work, we had collected literature related to directive leadership and empowering leadership in these databases. And we only used the keywords “directive leadership,” and “empowering leadership.”

Literature Processing

Literature was included in our research if it met the following criteria. First, we collected research on the topic of participative leadership, excluding leadership research unrelated to participative management. Second, the literature we collected on participative leadership had to be written in either English or Chinese, excluding relevant research in other languages. Third, the literature included both quantitative and qualitative research and did not impose any restrictions on where the research was conducted or the industry in which it was conducted. Fourth, the information we collected on participative leadership included published journal articles, conference papers, master’s and doctoral dissertations, and so on. In addition, compared to participative leadership, we collected mostly review-based literature on empowering leadership and directive leadership, including some empirical researches, to better understand both types of leadership. Also, the literature must be written in Chinese or English.

The Concept of Participative Leadership

According to literature review, participative leadership is a democratic leadership that involves subordinates in organizational decision-making and management, with the aim of effectively enhancing employees’ sense of ownership and actively integrating their personal goals into organizational goals. Therefore, in the daily leadership process, leaders actively implement “participation management” for their subordinates, such as conveying meaningful values, actively organizing reporting and other flexible promotion strategies ( Jing et al., 2017 ). The American scholar Likert (1961) , after extensive experimental research on democratic leadership, formally introduced the concept of participative leadership in his book “A New Model of Management” and revealed the three main principles of participative leadership theory, including the mutual support principle, the group decision principle and the high standards principle. Since the introduction of participative leadership, it has received much attention from a large number of researchers. Based on previous research, Kahai et al. (1997) redefined it as participative leadership, which refers to a leadership style in which leaders ask employees for their opinions before making decisions, delegate decision-making authority to subordinates in practice, and encourage active participation by employees to make decisions together. The literature also reflects two core characteristics of participative leadership: first, employees are consulted before decisions are made in order to solve problems together; second, employees are given resources to support them in the work process ( Kahai et al., 1997 ; Lam et al., 2015 ; Li et al., 2018 ).

Participative leadership is also characterised in practice by the following features: first, in the process of employee participation in decision-making, leaders and subordinates are on an equal footing and trust each other completely, and organizational issues are resolved through democratic consultation. Second, in general, although participative management involves a wide range of employees in decision-making, the final decision is still made by the leaders. Huang et al. (2010) also explored participative leadership in-depth and argued that participative leadership requires more encouragement and support for employees in the decision-making process and sharing of information and ideas, which has been recognized by many scholars ( Xiang and Long, 2013 ; Lam et al., 2015 ; Li et al., 2018 ). It is easy to see that the core of participative leadership is to encourage employees to participate in organizational decision-making, and the key to the leadership process is to make a series of management tasks such as consulting employees before making decisions ( Benoliel and Somech, 2014 ). Thus, based on many previous studies and practical experience, we consider participative leadership as a set of leadership behaviors that promote subordinates to participate in decision-making by giving them a certain degree of discretionary powers, effective information and other resources, as well as care and encouragement, so that they can be consulted enough before making decisions to solve work problems together( Huang et al., 2010 ; Chan, 2019 ).

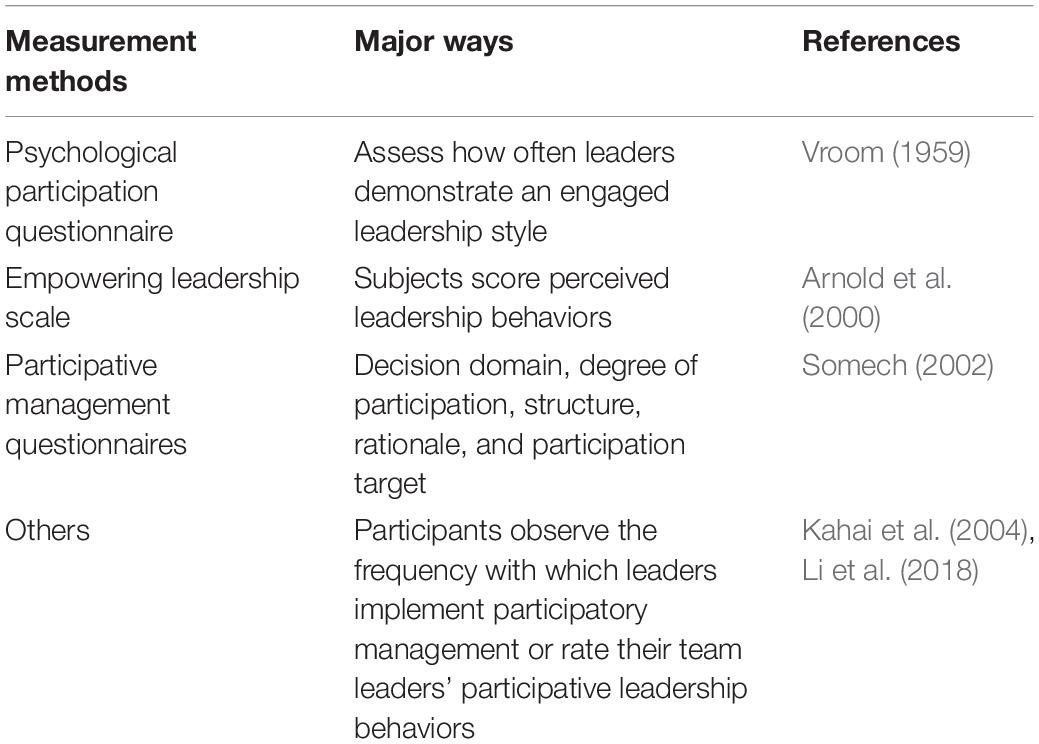

Measurement of Participative Leadership

The current measurement of participative leadership is mainly in the form of questionnaires in quantitative research and consists of the following measurement scales. First, Vroom (1959) psychological participation questionnaire, which evaluates the frequency with which leaders demonstrate a participative leadership style and reflects the overall ability of members to influence decisions and provide input and advice to leaders, consists of four questions (α = 0.63), sample item: “If you had a suggestion to improve your work or change a process in some way, how easy would it be for you to communicate the idea to your leader.”

Second, the empowering leadership scale (ELS) developed by Arnold et al. (2000) in which subjects score perceived leadership behaviors, with several items in the participation in decision-making section becoming a measure of participative leadership (α = 0.86), and is currently recognized by most scholars, with a total of six questions, and a sample item is “Encourages work group members to express ideas/suggestions.” The measurement scale developed by Arnold et al. (2000) has been widely used in empirical research ( Huang et al., 2010 ; Lam et al., 2015 ; Peng et al., 2021 ).

Third, the participative management questionnaires. In research of participative management in education, Somech (2002) designed a participative management scale with a total of thirty-five items, which includes five dimensions: decision domain (10 items; α = 0.83), degree of participation (4 items; α = 0.79), structure (3 items; α = 0.79), rationale (9 items; α = 0.77), and participation target (9 items; α = 0.69). Decision domain refers to determine if, after a decade of explicit attention to and advocacy of enhanced participative leadership, principals prefer to involve teachers not only in the technical domain, but also in the managerial, and a sample item is “Setting and revising the school goals.” Degree of participation refers to differentiating the extent of participation from the degree of participation, and a sample item is “Makes decisions on his or her own.” Structure refers to the extent to which a formal structure for validating decisions exist in the school and their relationship to other dimensions of participation, and a sample item is “To what extent explicit procedures existed at the school concerning who participated in the decision-making process.” Rationale is to determine, through an exploratory method, the main motives that inspired principals to participate in management and their relationship with the degree of participative management, and a sample item is “Encourage teacher’s acceptance of the decision.” Participation target refers to examine principals’ considerations in choosing which teacher to involve in the decision-making process, and a sample item is “The teacher expressed an independent thinking style.” The measurement scale developed by Somech (2002) has been found to have a good use in research ( Benoliel and Somech, 2014 ).

Fourth, some scholars had adapted or developed participative leadership scales by themselves, but the use is limited. For example, Kahai et al. (2004) used group-level responses (3 items) about how frequently participants observed the leader to implement participative management. A sample item is “Incorporating their suggestions into the final decision.” And Li et al. (2018) adapted from Oldham and Cummings (1996) and Kahai’s studies ( Kahai et al., 2004 ), which asked employees to rate their team leaders’ participative leadership behaviors on a four-item scale (α = 0.81), with typical questions such as “Puts suggestions from our group members into the final decision.” The individual responses were aggregated to the team level. Mean r wg was 0.90. And Zhao et al. (2019) developed a five-item scale, with typical questions such as “Leaders encourage team members to be active in suggesting ideas” (α = 0.80). In addition, there are also some studies that utilize the case method in qualitative research. For example, Jing et al. (2017) used an embedded case approach to provide an in-depth analysis of the role played by participative leadership. Finally, we summarize the major ways and references of previous measurements in the form of tables, as shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. Summary of measurements.

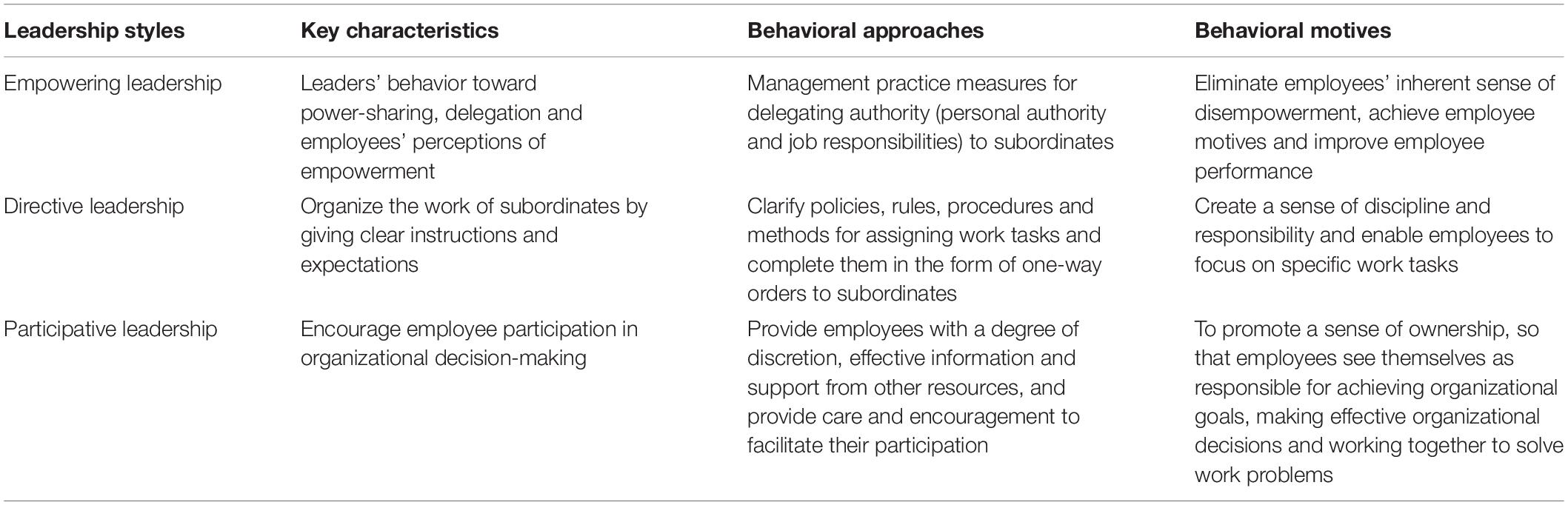

Comparison Between Participative Leadership and Other Leadership Styles

A review of the recent literature reveals that some scholars usually discuss participative leadership together with empowering leadership and directive leadership, but they are only mentioned, without in-depth analysis of the similarities and differences between them ( Lonati, 2020 ; Zou et al., 2020 ). At present, the lack of comprehensive comparative analysis of the three leadership styles. Therefore, we analyze the similarities and differences between participative leadership and empowering leadership and directive leadership to varying degrees and compares them in terms of key characteristics, behavioral approaches and behavioral motives to highlight the unique research value of participative leadership, as shown in Table 2 .

Table 2. Contrast of different leadership styles.

Empowering Leadership

The situational empowerment perspective emphasizes the practice of empowerment in organizational situations and defines empowering leadership as a series of management practices that empower subordinates. The psychological empowerment perspective emphasizes the psychological experience of empowerment and defines it as a motivational tool to eliminate employees’ internal feelings of disempowerment by raising their level of motive. And the integration of situational perspective and psychological perspective emphasizes the leaders’ behavior toward power sharing and employees’ perceptions of empowerment, illustrating the process of achieving power sharing between leaders and employees ( Tang et al., 2012 ). It is easy to see that both empowering leadership and participative leadership denote the delegation of leadership authority, but the focus are different. Specifically, participative leadership refers to the sharing and delegation of decision-making power, which means that subordinates are able to participate in the leaders’ decisions and express their views, while empowered leadership is more concerned with the delegation of personal authority and job responsibilities, so that subordinates have a certain degree of autonomy in deciding how to work, in order to achieve self-motive ( Amundsen and Martinsen, 2014 ). In addition, empowering leaders have a certain degree of positivity when they delegate their power, but they also tend to make employees feel that the leader is not willing to manage, which reduces the effectiveness of leadership. However, the participative leaders only share decision-making power with subordinates, retaining the authority and responsibility for leadership work and effectively avoiding employees’ perceptions of laissez-faire management. Thus, participative leadership is unique in that it not only achieves performance goals but also reduces the corresponding negative impacts ( Zou et al., 2020 ).

Directive Leadership

Directive leadership is about providing specific instructions to employees and clarifying policies, rules and procedures designed to organize the work of subordinates by providing obvious instructions and expectations regarding compliance with instructions ( Li et al., 2018 ; Lonati, 2020 ). In short, directive leadership is the use of leadership authority to tell subordinates what to do by way of orders, instructions, etc., in order to successfully achieve organizational goals. In other words, directive leadership is the procedure and method by which the leader assigns organizational tasks to subordinates and accomplishes them by means of one-way communication, and there is a relationship of command and obedience, instruction and execution between the leader and subordinates. Not only that, organizations with directive leadership are more likely to have normalized work processes, and employees are likely to obey the precise orders of the leader, allowing themselves to be fully focused on completing specific work tasks ( Lorinkova et al., 2013 ). Consequently, social messages such as clear work objectives, specific work procedures and supervision by organizational leaders create a sense of rules and responsibility among subordinates, but undermine employee creativity. Participative leaders, however, actively engage in interpersonal interaction with their employees in order to make decisions together. And, participative leadership, characterised by autonomy, collaboration and openness, encourages the employees to work innovatively by providing creative ideas and solutions that lead to the best decisions ( Lam et al., 2015 ). Therefore, participative leadership is more effective in stimulating employee creativity than directive leadership.

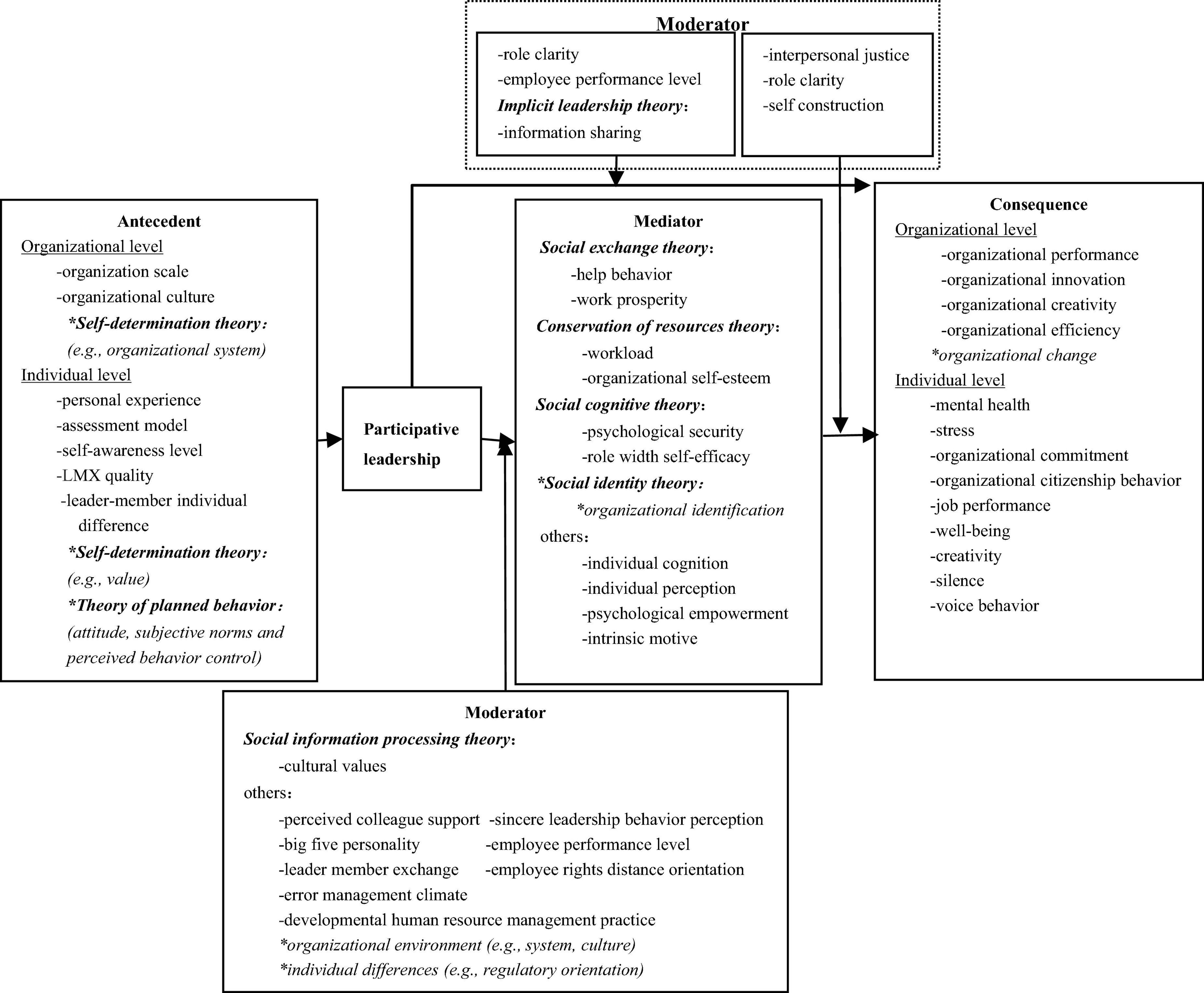

Research Framework for Participative Leadership

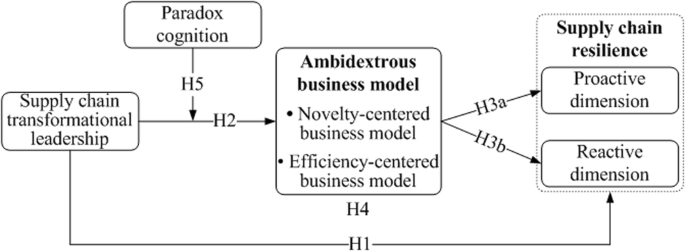

Changes in the external marketplace put forward objective demands on the development of the organization’s strategic solutions, making it difficult for the organization’s leaders to make the right and effective decisions quickly on their own ( Li et al., 2018 ; Zhao et al., 2019 ). Based on a review of previous research, we develop a research framework for participative leadership (shown in Figure 1 ) including the antecedents, mechanisms (mediator and moderator), and consequences of this type of leadership, with a view to clearly showing the lineage of empirical research on participative leadership for scholars’ subsequent exploration.

Figure 1. Empirical research on participative leadership. Data sources were reviewed according to relevant literature; “-”represents the existing research path and variables; “*”represents the path and variables proposed in future research.

The Antecedents of Participative Leadership

The antecedents of participative leadership can provide positive guidance for the development of this leadership research. Currently, the antecedents of participative leadership can be divided into individual-level antecedents and organizational-level antecedents. A lot of studies on antecedents focus on the individual level, such as individual experience, assessment model and leader-member individual difference ( Somech, 2002 ; Li et al., 2018 ). These factors promote leaders to show more participative management behaviors. In contrast, greater organizational control over participative behaviors tends to push leaders to highlight the significance of employee participation in organizational decision-making. As proof, organizational culture and organizational size have great influence on leaders’ participative management behaviors.

Individual-Level Antecedents

Some scholars pointed out that the implementation of participative management is related to personal factors. For example, experienced leaders may be more inclined to engage in participative management ( Somech, 2002 ). Among the specific research on individual influences, the influence of personality tendencies on leadership style has become a key theoretical concern. In particular, based on the regulatory model theory, Li et al. (2018) found that the assessment model refers to the fact that individuals are more concerned with obtaining the best solution during self-regulation, and it is more likely to develop a participative leadership style, while the locomotion model is more concerned with state change and more likely to develop a directive leadership style. At the same time, the leader’s awareness of participative management is key to influencing his or her participative management style and is seen as a determinant of participative leadership. For example, in a research on leaders in business and government, Black (2020) showed that leaders’ self-awareness has a significant impact on their leadership style, and the higher the level of self-reported individual awareness, the more pronounced the participative leadership style. In addition, Somech’s (2003) research (2003), in conjunction with the leader-member exchange model, suggests that individual differences between leaders and subordinates also influence leadership style, the greater the differences, the less likely the leader is to implement participative management. In other words, the quality of the relationship between the leaders and the subordinates may influence the leaders’ management style. On this basis, Chen and Tjosvold (2006) also confirmed the idea that leader-member exchange quality is a key influence on participative management. The study further points out that cooperation, compared with competitiveness and independence, is an important basis for high-quality leader-member exchange, and the resulting leader-member relationships improve individual confidence and overcome cross-cultural differences, thus effectively enhancing participative management.

Organizational-Level Antecedents

Based on existing research, it is easy to understand the important role that personal factors play in predicting leadership styles in managerial roles. However, there can be significant differences in the way individuals lead in different contexts, as individuals in different situational organizations actively socialize by choosing to behave in a way that matches the context in which they are placed. There is no doubt that organizational context becomes a key factor in influencing leadership behaviors and styles ( Schneider, 1983 ). For example, leaders in small-scale societies living in primitive nomadic, hunter-gatherer societies were particularly focused on participative decision-making management, whereas in the era of intensive agricultural societies, as group size increased, participative decision-making management in small-scale societies often became ineffective, while increased social complexity and distortions in the distribution of power made organizational leaders rarely demonstrate participative management and instead gave rise to directive leadership ( Lonati, 2020 ). At the same time, an organizational culture that is acceptable and supportive of participative management in the workplace is also key to the development of participative leadership ( Huang et al., 2011 ). Bullough and De (2015) also analysed this in-depth and state that the social environment significantly increases the effectiveness of participative leadership based on the implicit leadership theory of cultural identity.

Mechanisms of Participative Leadership

We find that participative leadership, based on different theories from the social sciences, has significantly different effects on organizational employees through different mechanisms (mediators and moderators). First, based on social exchange theory, participative leadership influences employees by promoting their job prosperity and mutual help behavior ( Usman et al., 2021 ). Second, conservation of resources theory suggests that participative leadership would change employee behaviors in two different ways, increasing employee workload and improving organizational self-esteem ( Peng et al., 2021 ). Third, research based on social cognitive theory confirms that participative leadership increases employees’ self-efficacy and psychological security, which in turn affects employees’ innovation and performance ( Zou et al., 2020 ). Fourth, social information processing theory implies that the process of participative leadership affecting employee behaviors may be influenced by cultural values and other aspects ( Zhang et al., 2011 ). Fifth, drawing on implicit leadership theory, leaders’ information-sharing behaviors can moderate the relationship between participative leadership and employee performance ( Lam et al., 2015 ).

Social Exchange Theory

Social exchange theory has become an essential theory in researching the relationship between leaders and subordinates’ work attitudes and behaviors ( Miao et al., 2014 ). Some scholars had pointed out that Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) is to some extent reciprocal, and that supportive behaviors by the leader in an exchange relationship makes the subordinate feel obliged to reciprocate with positive attitudes and behaviors. In this way, social exchange theory, to a certain extent, provides a powerful explanation for participative leadership research. Because participative leaders encourage employees to express their personal views and opinions, actively give them the power to make decisions about their work, more respect and information resources to facilitate their participation in organizational decision-making, these signals of concern and support lead employees to perceive favors from their leaders, which in turn leads them to adopt a series of behaviors in return for their leaders ( Xiang and Long, 2013 ). Despite the uncertainty of social exchange, most subordinates will respond positively to the participative management behaviors of their leaders based on the normative principle of reciprocity. Because the process of leaders consulting employees before making decisions makes a positive social exchange relationship, employees tend to perform better at work. Based on social exchange theory, Usman et al. (2021) also confirmed that employees encouraged by participative leadership behaviors performed better in terms of job prosperity and took the initiative to offer help to others.

Conservation of Resources Theory

COR recognizes that individuals have limited resources and that personal resources must be acquired, preserved and maintained on an ongoing basis. “Resources” is a broad term that includes not only the objects (e.g., pay), conditions (e.g., organizational status) and energy that individuals value in achieving their goals, but also individual characteristics. Of these, individual characteristics are seen as important resources that further influence how employees deal with other changes in their resources ( Hobfoll and Shirom, 2001 ). For example, participative management may lead to higher performance goals for highly committed employees and less effort for less committed employees to conserve resources ( Benoliel and Somech, 2014 ). That is, different individuals hold different amounts and types of available resources and respond differently to the problems they face in work. It is important to note that, according to resource conservation theory, individuals are naturally motivated to acquire and maintain the resources that are more important to them. And as a result of this motive, individual resources may undergo two distinct changes in resource gain or resource loss, where resource gain indicates that the initial resource gainer is more capable of acquiring the resource, and resource loss refers to an initial threat to the resource that tends to lead to increased resource loss ( Halbesleben et al., 2014 ). Therefore, Peng et al. (2021) specifically highlighted that, according to resource conservation theory, participative leaders may have different impacts on employee resources through the two pathways described above. First, participative management provides employees with certain resources, resulting in various degrees of increase in employees’ sense of value and self-esteem, thus triggering resource gains. Second, participative management adds extra workloads to employees, thus triggering resource losses. In conclusion, resource conservation theory reasonably explain the effect of participative leadership on subordinates’ work behaviors.

Social Cognitive Theory

Social cognitive theory has found that the external environment, cognitive factors and individual behavior interact with each other, and individuals adjust their cognition according to the information they receive from the external environment, so as to display and maintain behavior patterns that match their own cognition ( Bandura, 1978 ). That is, people can learn indirectly by observing, accurately perceiving the behavior of others and extracting information from it. And in leadership research, employee behavior is a product of perceptions of the environment. As a specific external environment, the messages conveyed by participative leadership style are an important part of employees’ daily contact in the workplace, and by observing and interpreting such messages, employees would change their perceptions of their own abilities and thus adopt behaviors that are consistent with them ( Zou et al., 2020 ). For example, research by Fatima et al. (2017) based on social cognitive theory finds that participative leadership, as one of the important environmental factors, is easier for employees with higher achievement needs to access environmental information and to apply and transform it during the influence of participative leadership on the creativity of their subordinates. Furthermore, within the research framework of the environment-cognition-behavior, participative leadership has been found to be effective in enhancing employees’ self-efficacy (perceptions of self-efficacy) and psychological security (perceptions of the interpersonal environment), contributing significantly to employees’ innovation and performance ( Zou et al., 2020 ). There is no doubt that social cognitive theory provides a new theoretical perspective and research framework for understanding the influence of participative leadership on employee behavior.

Social Information Processing Theory

SIP is concerned with the influence of the work environment on individual behaviors and work outcomes. It aims to reveal that individuals in organizations with a high degree of environmental adaptability actively or passively acquire information from the internal environment and process it according to certain rules to control their own attitudes and behaviors ( Gao et al., 2021 ). And SIP effectively explains individual behavioral change and provides a solid theoretical basis for describing participative leaders’ implementation of participative management. For example, research based on social information processing theory emphases that subordinates’ perceptions, beliefs and attitudes are influenced by information about their surroundings, such as values, norms and expectations from society ( Zhang et al., 2011 ). Leaders, in turn, are a key source of information for employees to access, and this information will collectively shape employees’ beliefs. That is, from a social information processing perspective, repeated observations of the leader’s style can enable employees to construct participative decision-making behaviors that the leader appreciates and encourages ( Odoardi et al., 2019 ). Further, research on this theory has found that participative decision-making not only informs employees about the occurrence of behaviors, but even facilitates the transformation of attitudes toward work ( Somech, 2010 ). It is important to note, however, that when cultural values differ, individuals may weigh information that encourages participation in decision-making and thus increase or decrease the impact of such information on their work ( Zhang et al., 2011 ). In particular, the impact that participative management by leaders may have on employees is particularly significant in large-power-distance cultures. It is easy to see that participative management messages originating from the leader are likely to be socially constructed among group members so that employees will agree on the process of working in a particular domain environment and thus adopt organizationally supported behaviors ( Odoardi et al., 2019 ).

Implicit Leadership Theory

The implicit leadership theory, derived from cognitive psychology, emphasizes the expectations and beliefs of employees about the competencies that leaders should possess, and is an “internal label” that distinguishes leaders from non-leaders, effective leaders from ineffective leaders ( Lu et al., 2008 ). In summary, leadership effectiveness in the study of implicit leadership theory does not emphasis the outcome of leadership behavior or focus on the control of situations, but exists in the minds of subordinates as a schema of their perceptions of the leader. Furthermore, if the participative leadership does not send out strong enough signals to stimulate employees to participate in decision-making in line with expectations of participative management, this can prevent the activation of the “participation model” in subordinates. In such cases, employees are more inclined to stick with the status quo and do not respond positively to the participative leader until they perceive that the leader’s participative behaviors have reached a certain threshold level ( Lam et al., 2015 ). It has also been suggested that organizational culture is likely to change the effectiveness of participative leadership, as individuals influenced by their environment shape leader’s expectations, while research based on implicit leadership theory provides insight into how individual perceptions influence effective leader’s behaviors ( Bullough and De, 2015 ). This not only reflects the important role of the theory in participative leadership research, but also provides a sound framework for a better understanding the cross-cultural organizational behavior ( Huang et al., 2011 ).

The Consequences of Participative Leadership

Compared to the antecedents of participative leadership, the consequences can also be divided into the individual level and the organizational level. A lot of studies have focused on employee organizational commitment and voice behavior and so on at an individual level ( Miao et al., 2014 ). In particular, some scholars had found that the participative leadership is positively related to employee mental health, voice behavior, and creativity ( Somech, 2010 ; Fatima et al., 2017 ; Usman et al., 2021 ). In addition, the participative leadership improves performance and innovation at the organizational levels ( Kahai et al., 2004 ; Yan, 2011 ).

Individual-Level Outcomes

The impact of participative leadership on subordinates stems from the leader’s empowerment and the consequent changes in psychology, attitudes, behaviors and outcomes of employees. First, on the psychological front, numerous studies have shown that participative leadership is beneficial to the psychological well-being of an organization’s employees. However, over-reliance on participative management by leaders can also have a negative impact on employees to some extent. In particular, the increased work challenges and responsibilities associated with participative management at work can be more or less burdensome for some employees, resulting in psychological stress ( Benoliel and Somech, 2014 ). Second, in terms of attitude, because participative leadership makes subordinates feel psychologically empowered, it increases the organizational commitment of some employees and even shows complete emotional trust in the leader ( Miao et al., 2014 ). However, it is essential to note that participative leadership has no significant role in influencing employees’ perceived trust. Then, in terms of behavior, Sagnak (2016) noted that leaders who implement participative management significantly increase employees’ change-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors by motivating their subordinates, such as helpfulness among employees at work ( Usman et al., 2021 ). In addition, participative leadership has been a significant contributor to the organizational focus on employee innovation and voice building, and has been supported by numerous scholars ( Xiang and Long, 2013 ). Finally, in terms of outcomes, existing research suggests that participative leadership plays an important role in both the increase in employee performance and the improvement of individual competencies. In terms of current research on job performance, there has been a great deal of scholarly attention paid to subordinate work outcomes and indirectly related job prosperity ( Somech, 2010 ; Usman et al., 2021 ). And on individual employee competencies, creativity has become the focus of the work of some scholars in participative leadership research ( Fatima et al., 2017 ).

Organizational-Level Outcomes

Overall, participative management is gradually becoming an important management initiative for current organizational management practitioners, and participative leadership is undoubtedly a key leadership style that cannot be ignored in leadership research. And most scholars agree that participative leadership has a catalytic effect on organizations. For example, some scholars had analyzed that participative leadership significantly improves organizational performance and innovation ( Kahai et al., 2004 ; Yan, 2011 ). Further, and this is confirmed by Somech’s (2010) research (2010) based on the education sector, participative management has a clear driving effect on the organizational performance in higher education. However, the positive effects of participative leadership are inevitably accompanied by some negative effects ( Peng et al., 2021 ). In this regard, Li et al. (2018) argued, by comparing research on directive leadership, that while participative leadership has a positive impact on organizational creativity, it reduces organizational effectiveness to a certain extent. It is easy to see that the impact of participative leadership style on the organizational level is somewhat unique and complicated. In addition, numerous studies have shown that there may be a series of mediating or interacting effects of participative leadership on organizational performance and corporate capabilities ( Kahai et al., 2004 ; Yan, 2011 ). Among the various research on the effects of participative leadership, it’s particularly critical to emphasize that the fact that participative leadership affects organizations by influencing employees at the individual level has become a consensus in current theoretical research and has prompted a large number of scholars to conduct in-depth studies on the subject ( Kim and Schachter, 2015 ).

Future Research

At present, whether in management practice or theoretical research, there is still a large research space for participative leadership, which needs to be further explored by scholars. Therefore, we prospecte and incorporate some views into the analysis framework (shown in Figure 1 ).

First, most of the existing literature on this leadership style is based on some of the questions in research on empowered leadership, and is still in use today ( Arnold et al., 2000 ). However, the measurement of participative leadership is rather general, focusing on characteristics and behaviors, and lacks a deeper exploration of the psychological dimension ( Arnold et al., 2000 ). With the development of the information technology and the continuous changes in leadership practice, the existing research has not formed a new understanding of the content of the participative leadership style, either in terms of the form of participative leadership or its measurement, so that the development of the theory is difficult to match the current leadership management practice, and some scholars had even appeared to be critical of participative leadership ( Gwele, 2008 ). In other words, previous interpretations of participative leadership have hindered the future research and application of this theory. It is easy to see that the conceptual content of participative leadership theory still has a lot of space to be added and optimised, and that subsequent research needs to take a more comprehensive view of the theory. Therefore, there is an urgent need for theoretical research on participative leadership to be further summarised through more scientific and rigorous analytical methods, such as experimental methods, in order to effectively classify the dimensions of participative leadership according to its modern manifestations and to develop a more mature scale for the measurement of constructs.

Second, previous research suggests that participative leadership might be seen as a rational response by leaders to organizational decisions and employee needs ( Zhao et al., 2019 ). However, participative leaders may also be subject to both internal and external pressures to implement participative management. As research in self-determination theory has shown, individual motivation is divided into autonomous motivation and controlled motivation. Whereas autonomous motivation refers to the individual’s action as a result of matching the activity with his or her values, goals, etc., control motivation emphasizes the behavioral activities that the individual is forced to take as a result of external pressures ( Gagné and Deci, 2005 ). Therefore, the antecedents of participative leadership can be studied in detail in the future based on self-determination theory. On the one hand, the influence of individual values, goals and interests on their own management behaviors is analyzed in the light of autonomous motivation; on the other hand, the dual pressure of the internal environment (e.g., professional managerial system) and the external environment (e.g., market uncertainty) places high demands on the scientific and accurate decision-making of leaders, which undoubtedly increases their motivation to control and thus to take part in management in order to avoid the risk of dictatorship that could lead to major risks or losses. At the same time, the theory of planned behavior suggests that individual behavior is determined by their own intentions and perceptual behavioral control ( McEachan et al., 2011 ). Some scholars have found that individual behavioral intentions are positively influenced by their behavioral attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, respectively. That is, they are more likely to engage in participative management if leaders maintain an optimistic attitude toward it, have the support of their employees and believe they can successfully implement it. This suggests that the theory of planned behavior also plays a key role in the antecedents of participative leadership research.

Third, throughout the current research on the results of participative leadership, many scholars have paid attention on the effects at the individual level, such as happiness at work, employee performance, etc. ( Chen and Tjosvold, 2006 ). And there is still more room for research on the analysis of results relative to the organizational level, especially on aspects such as organizational change. As a particular form of group decision-making, participative leadership may have a beneficial effect on smaller organizational changes. However, when faced with large organizational changes, employees may be concerned about career risks and may be a deterrent to smooth organizational change in the process of participation in decision-making. Moreover, much of existing research has focused on the positive effects of participative leadership. However, the too-much-of-a-good-thing effect (TMGTE) also plays a key role in organizational leadership research and cannot be ignored. This effect suggests that over-implementation of a behavior is likely to have potentially negative influences. From this perspective, leaders who practice high levels of participative leadership and over-empower employees to participate in organizational decision-making can lead to the TMGTE. In particular, the dual-task processing effect, whereby participative leaders delegate more power or tasks to subordinates in organizational decision-making, significantly increases the amount and variety of work performed by employees, and reduces employee well-being ( Peng et al., 2021 ). Therefore, a deeper analysis of the formation mechanism of the negative effects of participative leadership can be carried out, and a theoretical framework on the motives, concrete manifestations and path mechanisms of its behavior can be systematically constructed, with a view to providing strategies and suggestions for leaders to make scientific and practical decisions.

Fourth, both management practice and academic studies suggest that participative leaders’ management may be more likely to attract individuals with higher motivation and values to join the organization and, by effectively enhancing the identity of the organization’s members, to successfully implement participative management initiatives, which in turn may evolve into a more integrated and holistic decision-making mechanism covering all employees of the organization ( Odoardi et al., 2019 ). Thus, future research could analyze the mediating effect of organizational identity in the relationship between participative leadership and influence effects based on social identity theory, and further explore other aspects of mediation mechanisms. It’s also worth noting that the relationship between participative leadership and subordinates’ behavioral performance is also influenced by a number of variables, in particular the organizational context (e.g., systems and culture) and individual differences (e.g., subordinates’ regulatory orientation characteristics). As most organizations are now actively building workplaces that attract and retain employees, and as organizations flatten, the culture and systems are more participative, the idea of employee participation in organizational decision-making is being accelerated at all levels of the organization ( Somech, 2010 ; Lythreatis et al., 2019 ). In addition, if employees exhibit promotion focus (prevention focus), they may maintain a positive (negative) attitude toward the leader’s participative management, which also affects to a certain extent the effectiveness of the leadership participative management when implemented. In conclusion, the exploration of the intrinsic mediating mechanisms and boundary conditions of the effects of participative leadership is conducive to revealing the operational mechanisms and mechanisms of action of participative management, promoting the integration of relevant factors into a more unified framework and enriching the theoretical research of participative leadership.

Finally, as a type of democratic leadership style, although participative management has attracted the attention of some Chinese scholars. However, influenced by China’s thousands of years of history and culture, long-term authoritarian rule has caused individuals to lack a sense of independence, and employees have shown dependence and submissiveness to their leaders. Therefore, participative leadership has not received much attention from Chinese scholars. However, as the new generation of employees, such as the post-90s generation and post-00s generation, is flooding into various positions in enterprises and institutions, more and more employees are showing strong values of independence and freedom. The practice has also shown that the new generation of employees is active, receptive to information and innovative, and that participation in management not only helps to avoid the negative emotions of employees due to the dictatorship of the leader, but also facilitates the absorption of new ideas and information by the leader, and produces innovative results, which proves the urgent need for participation in leadership in the Chinese society. This is an important signal for Chinese scholars to localize the researches of participative leadership in the context of Chinese society, as western thought is constantly impacting on traditional Chinese culture and organizations in western countries are placing more emphasis on participation in decision-making than China, and are actively taking several measures to this end. Although empirical research on participative leadership has started to gradually increase in recent years, there is still more room for development ( Zou et al., 2020 ). For example, research related to differential leadership based on the question of whether there are differences in the rights of participative leaders to involve different subordinates in organizational decision-making. In particular, leaders who have long been influenced by traditional Chinese culture are prone to self-perception based on closeness of relationships and classify subordinates as insiders and outsiders, resulting in significant differences in access to decision-making authority for different employees.

As the market becomes increasingly competitive, it is difficult for leaders to make effective decisions independently. As a result, participative leadership is becoming an important element in leadership research. Scholars are also aware of the need to implement participative management in organizational decision-making. In terms of current theoretical research, there are elements of participative leadership that can be further developed and explored. From the perspective of management decisions in practice, participative leadership has dramatically improved the effectiveness of leadership decisions. This study systematically sorts out the concept and measurement of participative leadership and compare it with empowering leadership and directive leadership. We not only discuss the antecedents and outcomes of participative leadership, but also provide an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms by which participative leadership influences employees based on social exchange theory, social cognitive theory, resource conservation theory, implicit leadership theory, and social information processing theory. Finally, we propose a framework for future research on participative leadership that encompasses five potential research areas, including connotation, antecedents, outcomes, mediators and moderators, and study of participative leadership in China.

Through a systematic review of research related to participative leadership, this study makes several contributions to the development of participative leadership as follows. First, we clarify the concept, measurement, antecedents, theoretical foundations, and results of participative leadership to lay the foundation for subsequent participative leadership research. Second, we systematically compare participative leadership with directive and empowering leadership, distinguish the similarities and differences among the three, and clarify the unique research value of participative leadership. Third, by reviewing previous research on participative leadership and taking into account current leadership trends, we propose several future research perspectives, thus exploring what is currently neglected by scholars.

Author Contributions

QW mainly made important contributions in clarifying the idea of the article, selecting the research method, literature collection, and article writing. HH made substantial contributions to literature collection, article revision, and optimization. ZL mainly played a crucial role in literature collection. All authors made outstanding contributions to this research.

This research was supported by the State Key Program of National Social Science of China (Project Number # 20AZD095).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Amundsen, S., and Martinsen, O. L. (2014). Empowering leadership: construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. Leadersh. Q. 25, 487–511. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.009

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arnold, J. A., Arad, S., and Drasgow, F. (2000). The empowering leadership questionnaire: the construction and validation of a new scale for measuring leader behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 21, 249–269. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200005)21:3<249::AID-JOB10>3.0.CO;2-\#

Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv. Behav. Res. Ther. 1, 139–161. doi: 10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

Benoliel, P., and Somech, A. (2014). The health and performance effects of participative leadership: exploring the moderating role of the big five personality dimensions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 23, 277–294. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2012.717689

Black, G. (2020). The Vital Connection of Self-Awareness to Ethical and Participative Leadership:in the Decision Making Processes. San Diego: Alliant International University.

Google Scholar

Bullough, A., and De, L. M. S. (2015). Women’s participation in entrepreneurial and political leadership: the importance of culturally endorsed implicit leadership theories. Leadersh 11, 36–56. doi: 10.1177/1742715013504427

Chan, S. (2019). Participative leadership and job satisfaction: the mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of fun experienced at work. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 40, 319–333. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-06-2018-0215

Chang, Y. Y., Chang, C. Y., Chen, Y. C. K., Seih, Y. T., and Chang, S. Y. (2021). Participative leadership and unit performance: evidence for intermediate linkages. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 19, 355–369. doi: 10.1080/14778238.2020.1755208

Chen, Y. F., and Tjosvold, D. (2006). Participative leadership by American and Chinese managers in china:the role of relationships. J. Manage. Stud. 43, 1727–1752. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00657.x

Fatima, T., Safdar, S., and Jahanzeb, S. (2017). Participative leadership and employee creativity: moderating role of need for achievement. NUML Int. J. Bus. Manage. 12, 1–14.

Gagné, M., and Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 26, 331–362. doi: 10.1002/job.322

Gao, P., Xue, P., and Xie, Y. (2021). Influence of self-monitoring personality on innovation performance from information processing perspective. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 38, 151–160. doi: 10.6049/kjjbydc.2020040203

Gwele, N. S. (2008). Participative leadership in managing a faculty strategy. South Afr. J. Higher Educ. 22, 322–332. doi: 10.4314/sajhe.v22i2.25788

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., and Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “cor”: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 40, 1334–1364. doi: 10.1177/0149206314527130

Hobfoll, S. E., and Shirom, A. (2001). Conservation of resources theory: applications to stress and management in the workplac. Public Policy Adm. 87, 57–80.

Huang, S. Y. B., Li, M. W., and Chang, T. W. (2021). Transformational leadership, ethical leadership, and participative leadership in predicting counterproductive work behaviors: evidence from financial technology firms. Front. Psychol. 12:658727. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.658727

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huang, X., Iun, J., Liu, A., and Gong, Y. (2010). Does participative leadership enhance work performance by inducing empowerment or trust? the differential effects on managerial and non-managerial subordinates. J. Organ. Behav. 31, 122–143. doi: 10.1002/job.636

Huang, X., Rode, J. C., and Schroeder, R. G. (2011). Organizational structure and continuous improvement and learning: moderating effects of cultural endorsement of participative leadership. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 42, 1103–1120. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2011.33

Huang, X., Shi, K., Zhang, Z., and Cheung, Y. L. (2006). The impact of participative leadership behavior on psychological empowerment and organizational commitment in Chinese state-owned enterprises: The moderating role of organizational tenure. Asia. Pac. J. Manage. 23, 345–367. doi: 10.1007/s10490-006-9006-3

Jia, S., Qiu, Y., and Yang, C. (2021). Sustainable development goals, financial inclusion, and grain security efficiency. Agron 11:2542. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11122542

Jing, Z., Jianshi, G., Jinlian, L., and Yao, T. (2017). A case study of the promoting strategies for innovation contest within a company. Sci. Res. Manage. 38, 57–65. doi: 10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2017.11.007

Kahai, S. S., Sosik, J. J., and Avolio, B. J. (1997). Effects of leadership style and problem structure on work group process and outcomes in an electronic meeting system environment. Pers. Psychol. 50, 121–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb00903.x

Kahai, S. S., Sosik, J. J., and Avolio, B. J. (2004). Effects of participative and directive leadership in electronic groups. Group Organ. Manage. 29, 67–105. doi: 10.1177/1059601103252100

Kim, C., and Schachter, H. L. (2015). Exploring followership in a public setting: is it a missing link between participative leadership and organizational performance? Am. Rev. Public. Adm. 45, 436–457. doi: 10.1177/0275074013508219

Lam, C. K., Huang, X., and Chan, S. C. H. (2015). The threshold effect of participative leadership and the role of leader information sharing. Acad. Manage. J. 58, 836–855. doi: 10.5465/amj.2013.0427

Li, G., Liu, H., and Luo, Y. (2018). Directive versus participative leadership: dispositional antecedents and team consequences. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 91, 645–664. doi: 10.1111/joop.12213

Likert, R. (1961). New Patterns of Management. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Book Company.

Lonati, S. (2020). What explains cultural differences in leadership styles? on the agricultural origins of participative and directive leadership. Leadersh. Q. 31:101305. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.07.003

Lorinkova, N. M., Pearsall, M. J., and Matthew, J. (2013). Examining the differential longitudinal performance of directive versus empowering leadership in teams. Acad. Manage. J. 56, 573–596. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0132

Lu, H. Z., Liu, Y. F., and Xu, K. (2008). Implicit leadership theory: a new development of cognitive revolution in leadership research. Psychol. Sci. 31, 242–244. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2008.01.058

Lythreatis, S., Mostafa, A. M. S., and Wang, X. (2019). Participative leadership and organizational identification in smes in the mena region: testing the roles of csr perceptions and pride in membership. J. Bus. Eth. 156, 635–650. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3557-8

McEachan, R. R. C., Conner, M., Taylor, N. J., and Lawton, R. J. (2011). Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 5, 97–144. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2010.521684

Miao, Q., Newman, A., and Huang, X. (2014). The impact of participative leadership on job performance and organizational citizenship behavior: distinguishing between the mediating effects of affective and cognitive trust. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 25, 2796–2810. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.934890

Odoardi, C., Battistelli, A., Montani, F., and Peiró, J. M. (2019). Affective commitment, participative leadership, and employee innovation: a multilevel investigation. Rev. Psicol. Trabajo. Organ. 35, 103–113. doi: 10.5093/jwop2019a12

Oldham, G. R., and Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: personal and contextual factors at work. Acad. Manage. J. 39, 607–634. doi: 10.2307/256657

Peng, J., Zou, Y. C., Kang, Y. J., and Zhang, X. (2021). Participative leadership and employee job well-being: perceived co-worker support as a boundary condition. J. Psychol. Sci. 44, 873–880. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20210415

Sagnak, M. (2016). Participative leadership and change-oriented organizational citizenship: the mediating effect of intrinsic motivation. Egit. Arast. 103, 717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.002

Schneider, B. (1983). Interactional psychology and organizational behavior. Res. Organ. Behav. 5, 1–31. doi: 10.21236/ada113432

Somech, A. (2002). Explicating the complexity of participative management: an investigation of multiple dimensions. Educ. Admin. Q. 38, 341–371. doi: 10.1177/00161X02038003004

Somech, A. (2003). Relationships of participative leadership with relational demography variables: a multi-level perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 24, 1003–1018. doi: 10.1002/job.225

Somech, A. (2010). Participative decision making in schools:a mediating-moderating analytical framework for understanding school and teacher outcomes. Educ. Admin. Q. 46, 174–209. doi: 10.1177/1094670510361745

Su, Y., Li, Z., and Yang, C. (2021). Spatial interaction spillover effects between digital financial technology and urban ecological efficiency in China: an empirical study based on spatial simultaneous equations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:8535. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168535

Tang, G. Y., Li, P. C., and Li, J. (2012). A review of frontier research of foreign empowering leadership and future prospects. For. Econ. Manage. 34, 73–80. doi: 10.16538/j.cnki.fem.2012.09.010

Usman, M., Ghani, U., Cheng, J., Farid, T., and Iqbal, S. (2021). Does participative leadership matters in employees’ outcomes during COVID-19? role of leader behavioral integrity. Front. Psychol. 2021:646442. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646442

Vroom, V. H. (1959). Some personality determinants of the effects of participation. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 59, 322–327. doi: 10.1037/h0049057

Xiang, C. R., and Long, L. R. (2013). Participative leadership and voice: the mediating role of assertive impression management motive. Manage. Rev. 25, 156–166. doi: 10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2013.07.009

Yan, J. (2011). An empirical examination of the interactive effects of goal orientation, participative leadership and task conflict on innovation in small business. J. Dev. Entrep. 16, 393–408. doi: 10.1142/S1084946711001896

Zhang, Z., Wang, M., and Fleenor, J. W. (2011). Effects of participative leadership: the moderating role of cultural values. Acad. Manage. Proc. 30, 1–6. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2011.65869732

Zhao, C., Tang, C. Y., Zhang, Y. S., and Niu, C. H. (2019). Task conflict and talent aggregation effect in scientific teams: the moderating effects of participative leadership. Sci. Manage. Res. 37, 56–60. doi: 10.19445/j.cnki.15-1103/g3.2019.05.010

Zou, Y. C., Peng, J., and Hou, N. (2020). Participative leadership and creative performance: a moderated dual path model. J. Manage. Sci. 33, 39–51. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0334.2020.03.004

Keywords : participative leadership, employee, participation, leadership, organization, decision, effectiveness

Citation: Wang Q, Hou H and Li Z (2022) Participative Leadership: A Literature Review and Prospects for Future Research. Front. Psychol. 13:924357. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.924357

Received: 20 April 2022; Accepted: 11 May 2022; Published: 03 June 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Hou and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hong Hou, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Leadership: A Comprehensive Review of Literature, Research and Theoretical Framework

2020, Leadership: A Comprehensive Review of Literature, Research and Theoretical Framework. In: Journal of Economics and Business, Vol.3, No.1, 44-64.

This paper provides a comprehensive literature review on the research and theoretical framework of leadership. The author illuminates the historical foundation of leadership theories and then clarifies modern leadership approaches. After a brief introduction on leadership and its definition, the paper mentions the trait theories, summarizes the still predominant behavioral approaches, gives insights about the contingency theories and finally touches the latest contemporary leadership theories. The overall aim of the paper is to give a brief understanding of how effective leadership can be achieved throughout the organization by exploring many different theories of leadership, and to present leadership as a basic way of achieving individual and organizational goals. The paper is hoped to be an important resource for the academics and researchers who would like to study on the leadership field.

Related Papers

Sonali Sharma

Shanlax International Journal of Commerce

vivek deshwal

Journal of Leadership and Management; 2391-6087

Betina Wolfgang Rennison

The theoretical field of leadership is enormous-there is a need for an overview. This article maps out a selection of the more fundamental perspectives on leadership found in the management literature. It presents six perspectives: personal, functional, institutional, situational, relational and positional perspectives. By mapping out these perspectives and thus creating a theoretical cartography, the article sheds light on the complex contours of the leadership terrain. That is essential, not least because one of the most important leadership skills today is not merely to master a particular management theory or method but to be able to step in and out of various perspectives and competently juggle the many possible interpretations through which leadership is formed and transformed.

Fila Bertrand, Ph.D.

Leadership and the numerous concepts on leadership styles have been subjects of both study and debate for years. Every leader approaches challenges differently, and his or her personality traits and life experiences greatly influence his or her leadership style and the organizations they lead. Furthermore, leadership is a notion resulting from the interaction between a leader and followers, and not a position or title within the organization. This essay examines some of the contemporary theories of leadership, the leadership qualities and traits necessary to be successful in today's competitive environment, the impact of leadership to the organization, and the importance of moral leadership in today's world.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE

Vivian A . Ariguzo , Michael okoro

Diverse views have emerged on leadership definitions, theories, and classification in academic discourse. The debate and conscious efforts made to clarify leadership actively has generated socio-cultural and organizational research on its styles and behaviours. This study seeks to identify the theoretical views of various academic scholars on some of the main theories that emerged during the 20 th century include: the Thomas Carlyle's Great Man theory, Gordon Allport's Trait theory, Fred Fiedler's Contingency theory, Hersey and Blanchard Situational Theory, Max Weber's Transactional theory, MacGregor Burns' Transformational theory, Robert Houses' Path-goal theory, and Vroom and Yetton's Participative theory. Empirical discourse that revealed findings of academic scholars have enshrined the import of leadership in organizations. Various academic literature that already have been subject to validity and reliability tests were reviewed and used to arrive at the findings. The study postulated the Mystical-man theory after a rich discourse and recommended it as the ideal theory for all Christian leaders to adopt as it is assumed to provide above average performance at all times, irrespective of followership behaviour.

Neil D . Walshe

The three topics of this volume—leadership, change, and organization development (OD)—can be viewed as three separate and distinct organizational topics or they can be understood as three distinct lenses viewing a common psycho-organizational process. We begin the volume with a comprehensive treatment of leadership primarily because we view leadership as the fulcrum or crucible for any significant change in human behavior at the individual, team, or organizational level. Leaders must apply their understanding of how to effect change at behavioral, procedural, and structural levels in enacting leadership efforts. In many cases, these efforts are quite purposeful, planned, and conscious. In others, leadership behavior may stem from less-conscious understandings and forces. The chapters in Part I: Leadership provide a comprehensive view of what we know and what we don’t know about leadership. Alimo-Metcalfe (Chapter 2) provides a comprehensive view of theories and measures of leadershi...

Transylvanian review of administrative sciences

Cornelia Macarie

The paper endeavors to offer an overview of the major theories on leadership and the way in which it influences the management of contemporary organizations. Numerous scholars highlight that there are numerous overlaps between the concepts of management and leadership. This is the reason why the first section of the paper focuses on providing an extensive overview of the literature regarding the meaning of the two aforementioned concepts. The second section addresses more in depth the concept of leadership and managerial leadership and focuses on the ideal profile of the leader. The last section of the paper critically discusses various types of leadership and more specifically modern approaches to the concept and practices of leadership.

An organization constitute of a diverse group of individuals, working together towards a specified common goal. A robust organizational framework is based upon specified values, believes and positive culture accompanied by effective leaders and managers that are expected to understand their roles and responsibilities towards both the employees and the management of the organization. Culture is recognized as "the glue" that binds a group of people together (Martin and Meyerson, 1988). Therefore, organizational culture entails intelligent and great leaders who value and believe in nurturing employees and appreciate their active participation in the progression of the company (Balain & Sparrow 2009). With that said, management is also one of the crucial organisational activities that is necessary to ensure the coordination of individual efforts as well as the organization's resources and activities. Lastly, leadership in itself is a vital bond that connects effective management and splendid organizational culture. However, for a long time, there has been a disconnect and inconsistency on what entails leadership and management. We identify with scholars who questioned the overlying issues regarding the significant concepts of leadership and management (Schedlitzki & Edwards,2014). It is therefore paramount to understand how leadership and management play critical roles in shaping up contemporary organizations, fundamentally appreciating the applicability that arises with the various leadership styles and management theories while apprehending their link to organization culture.

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development

Prof. Dr. Satya Subrahmanyam

This research article was motivated by the premise that no corporate grows further without effective corporate leaders. The purpose of this theoretical debate is to examine the wider context of corporate leadership theories and its effectiveness towards improving corporate leadership in the corporate world. Evolution of corporate leadership theories is a comprehensive study of leadership trends over the years and in various contexts and theoretical foundations. This research article presents the history of dominant corporate leadership theories and research, beginning with Great Man thesis and Trait theory to Decision process theory to various leadership characteristics. This article also offers a convenient way to utilize theoretical knowledge to the practical corporate situation.

Public Administration Review

Montgomery Van Wart

RELATED PAPERS

Juan Martinez

Zurab Bragvadze

Experiências em Ensino de Ciências

Ticiane Dias

Eduardo Henrique Baltrusch de Gois

Trilogía Ciencia Tecnología Sociedad

María Verónica Alderete

Jurnal Online Mahasiswa Bidang Pertanian

Siti Julaiha

IMIB Journal of Innovation and Management

Journal of Medical Internet Research

Satish Joshi

Pensamiento. Revista de investigación e información filosófica

Obdulio Banda

jayapal subramaniam

Gabriela Smarrelli

Anttoni Kervinen

Tourism & Management Studies

Regina Leite

SSRN Electronic Journal

Frank Pasquale

Gestão e Desenvolvimento

Luis Farinha

mandeep Chadha

Swapnajeet Das

Pediatric Research

Peggy McCardle

Numerical Methods and Applications

Zarif Sharipov

Lecture Notes in Computer Science

Carmem Hara

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 15 May 2024

Supply chain transformational leadership and resilience: the mediating role of ambidextrous business model

- Taiwen Feng 1 na1 ,

- Zhihui Si 1 na1 ,

- Wenbo Jiang 2 &

- Jianyu Tan 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 628 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

220 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

The global prevalence of COVID-19 has caused many supply chain disruptions, which calls for firms to build resilient supply chains. Prior research primarily examined the effects of firm resources or capabilities on supply chain resilience (SCR), with limited attention given to the critical role of supply chain transformational leadership (SCTL). Based on social learning theory, we explore how SCTL impacts SCR via an ambidextrous business model and the moderating role of paradox cognition. We employ hierarchical regression analysis to verify the hypotheses with data from 317 Chinese firms. The results show that SCTL has a positive impact on proactive and reactive SCR, and the ambidextrous business model mediates this relationship. Furthermore, paradox cognition strengthens the effect of SCTL on the ambidextrous business model. This study contributes to literature and practices in the field of transformational leadership and SCR by providing unique insights into how to improve SCR from a leadership perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration

The environmental price of fast fashion

Introduction.