- Share full article

Advertisement

The Morning

What’s going on with the u.s. economy.

The economic picture is simpler than the swirl of economic indicators sometimes suggests.

By David Leonhardt

The economy is probably headed toward a recession. No, it’s actually booming again.

Inflation is plummeting. No, it has started rising again.

If you find the cacophony of economic indicators to be confusing, don’t feel bad. It is confusing. Some numbers point in one direction, while others point in the opposite. Partisans from both political parties have an interest in promoting one type of news and downplaying the other.

Yesterday’s inflation report added to the muddle. Inflation — a major concern for many families and already a 2024 campaign issue — has been falling for the past year and half. Americans’ economic mood has improved slightly as a result . But the numbers released yesterday showed inflation to be higher than forecasters had expected. In response, the S&P 500 index fell 1.4 percent , its second-biggest daily decline this year.

In today’s newsletter, I’ll give you a framework for thinking about the state of the U.S. economy by describing the four main phases of the past several years. I can’t tell you what will happen next, but I do think the picture is simpler than the swirl of economic indicators sometimes suggests.

1. The pre-Covid boom

The American economy has been disappointing for much of the past half-century. Income and wealth growth has been slow for most families, and inequality has soared. Perhaps the starkest sign of the problems: Life expectancy in the U.S. is now lower than in any other high-income country, and it isn’t especially close .

Still, there have been a few brief periods when the economy has boomed. One of them began late in Barack Obama’s presidency and continued during Donald Trump’s term. The country finally emerged from its hangover after the housing crash, as businesses expanded and consumers spent more.

The unemployment rate fell below 5 percent in 2016 and below 4 percent in 2018. The tight labor market — combined with increases in the minimum wage in many states — raised income for all income groups.

Change in median weekly income

Compared with two years earlier, adjusted for inflation

By early 2020, the U.S. economy’s short-term performance was as healthy as it had been since the dot-com boom two decades earlier.

2. The Covid crash

Then the pandemic arrived.

People stayed home and cut back on spending. Businesses laid off workers, and the unemployment rate exceeded 10 percent. Experts understandably worried that the economy could fall into a vicious cycle, in which companies went out of business, families couldn’t make loan payments and banks went under.

Many economists believed that the federal government had been too timid with stimulus after the early-2000s housing crash. During the pandemic, members of Congress vowed not to repeat the mistake and passed huge stimulus bills, which both Trump and President Biden signed.

3. The too-hot recovery

Those stimulus programs worked — a bit too well.

For all the misery that Covid caused, it ended up being less economically destructive than the housing crash. The unemployment surge was temporary. And thanks to the stimulus, the typical American family’s finances improved during the pandemic — a very different situation than the aftermath of the housing crash.

In effect, Washington overlearned the lesson of the previous crisis. It pumped so much money into the economy during the pandemic that families were able to go on a spending spree. Businesses, in response, raised prices.

The pandemic’s supply-chain disruptions played a big role, too. This combination — high demand and low supply — led to sharp price increases.

Year-over-year change in Consumer Price Index

excluding food

in Jan. 2024

4. The healthier recovery

Once inflation rises, it can remain high for years (as it did from the late 1960s to the early 1980s). Workers demand bigger raises, and businesses, facing higher costs, raise prices even more. The dynamic is reinforcing.

When inflation soared in 2021, some economists thought the pattern was repeating. They predicted that only a deep recession would bring a return to normalcy. These dark predictions turned out to be wrong , though. Instead, inflation started falling rapidly in 2022. The end of the stimulus programs, combined with the end of most supply-chain problems, was enough to reduce price increases.

For the past several months, the economy has again looked healthy, with both employment and wages growing nicely. Yesterday’s report doesn’t change that: Annual inflation fell to 3.1 percent in January, from 3.4 percent in December. It’s just that forecasters had expected it to fall more than it did.

Why didn’t it? Maybe last month’s number was just a statistical blip. But maybe it is a sign that the economy has again become too strong for inflation to keep falling.

“Hiring picked up in January, wage growth was solid, and consumers continue to spend,” as my colleague Jeanna Smialek explains. “Some analysts have suggested that in an economy this hot, wrestling inflation the rest of the way to normal will prove more difficult than the progress so far.” Economists generally consider the ideal inflation rate to be around 2 percent.

By almost any measure, the economy is in better shape today than most forecasters predicted even a year ago. Still, it hasn’t fully recovered from the pandemic.

Related: The American economy has seen a burst of productivity recently. Read more about economists’ views on whether it will continue.

THE LATEST NEWS

Alejandro mayorkas.

House Republicans impeached Alejandro Mayorkas , Biden’s homeland security secretary, despite no evidence that he had committed impeachable offenses.

He is the first sitting cabinet member to be impeached. Read what could happen next .

The number of migrants illegally crossing into the U.S. from Mexico has dropped by half in the past month.

More on Politics

Tom Suozzi, a Democratic former congressman, won a special House election to replace George Santos in a Queens and Long Island district. Suozzi’s strategy offers a playbook for other Democrats .

Biden criticized Trump for suggesting that he would let Russia attack NATO countries that don’t spend enough on defense. “It’s dumb, it’s shameful, it’s dangerous, it’s un-American,” Biden said.

Biden urged Speaker Mike Johnson to let the House vote on a bill to aid Ukraine and Israel. If Johnson refuses, House members may use a procedural trick — a discharge petition — to go around him.

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has been released from hospital after his admission for a bladder issue.

A diamond ring and a “James Bond” phone: Court filings revealed new details in Senator Robert Menendez’s bribery case .

Top Senate Republicans endorsed Kari Lake for Senate in Arizona. Lake refused to admit her loss in the state’s 2022 governor’s race.

Israel-Hamas War

Arab governments are privately discussing a new vision for governing Gaza, according to a senior adviser . Their idea includes an independent Palestinian leader and an Arab peacekeeping force.

Negotiations in Cairo over a pause in fighting in Gaza have been extended by three days, according to Egyptian officials.

Hezbollah fired missiles into northern Israel , injuring at least two people.

Two Michigan students have opposing views on the war. Read about their civil, if awkward, conversation on campus .

After a crackdown on drunken driving, motorbikes are filling impound lots in Vietnam.

A South Korean court found three former police officers guilty of destroying evidence tied to a Halloween crowd crush that killed nearly 160 people in Seoul in 2022.

Two major parties in Pakistan agreed to form a coalition government. They withheld power from candidates aligned with former Prime Minister Imran Khan, even though his allies recently won the most seats.

Myanmar’s junta said it would impose a military draft to replenish forces that have been depleted fighting pro-democracy rebels.

China, faced with declining foreign investment, is trying to soften its image abroad. One Communist Party official has played a prominent role.

Other Big Stories

The East Coast is sinking , research has found. A major culprit: overpumping of groundwater.

Better memory: OpenAI is releasing a new version of ChatGPT . It will store what users write and apply the information to future chats.

A vehicle crashed into a hospital emergency room in Austin, Texas, killing at least one person and injuring five others.

As artificial intelligence takes over technical tasks, the human side of work — collaboration, empathy, communication — will become more valuable , Aneesh Raman and Maria Flynn argue.

Don’t buy flowers for your valentine . There are more environmentally friendly ways to show love, Margaret Renkl says.

Here are columns by Ross Douthat on inflation and Thomas Edsall on isolationism .

MORNING READS

Anti-Valentine’s Day: Single, anti-consumerist or just not a romantic? There’s a market for you, too .

Small acts: Times readers shared the little things they do to show affection all year long.

Your brain on love: Roses are red, violets are blue. This is how romance can mess with you .

Modern Love podcast: Hear how a couple navigated getting “un-married” while staying together .

New gig: Grover, the furry blue Muppet from “Sesame Street,” is becoming a reporter. Journalists aren’t optimistic .

Lives Lived: Bob Moore leveraged his grandfatherly image to turn the artisanal grain company Bob’s Red Mill into a $100 million-a-year business. He died at 94 .

N.F.L. draft: Read about the top 100 prospects in this year’s class.

N.B.A.: The Knicks are said to be filing a protest to dispute their 105-103 loss to the Rockets .

No. 32: The Orlando Magic retired Shaquille O’Neal’s jersey , making him the second player in N.B.A. history to have a jersey retired by three different franchises.

ARTS AND IDEAS

The closer: When the comedian Taylor Tomlinson began her tour, she was happy with everything in her set except for her closing joke. So, over months of live shows, she refined it, adding punchlines and tweaking details. A new story by the Times comedy critic Jason Zinoman follows her through the process, showing how small changes led to big laughs .

More on culture

Meghan Markle has found a new podcast partner . Markle and Prince Harry’s deal with Spotify ended after they delivered just one show, Variety reports.

The creators of “Six,” about the six wives of Henry VIII, announced that their second musical , “Why Am I So Single?,” will premiere in London in August.

Paramount, which owns Nickelodeon and MTV, is laying off hundreds of employees as it moves away from traditional television.

Late-night hosts discussed Trump recommending Lara Trump for co-chair of the R.N.C.

THE MORNING RECOMMENDS …

Combine just a few ingredients to make a simple, romantic spaghetti carbonara .

Listen to love songs about crushes .

Shop more sustainably .

Clean your blankets .

Here is today’s Spelling Bee . Yesterday’s pangrams were applicable and clippable .

Celebrate Valentine’s Day with this month’s bonus crossword puzzle , which has a rom-com theme.

And here are today’s Mini Crossword , Wordle , Sudoku and Connections .

Thanks for spending part of your morning with The Times. See you tomorrow. — David

Sign up here to get this newsletter in your inbox . Reach our team at [email protected] .

David Leonhardt runs The Morning , The Times’s flagship daily newsletter. Since joining The Times in 1999, he has been an economics columnist, opinion columnist, head of the Washington bureau and founding editor of the Upshot section, among other roles. More about David Leonhardt

Ten facts about COVID-19 and the U.S. economy

Subscribe to the economic studies bulletin, lauren bauer , lauren bauer fellow - economic studies , associate director - the hamilton project @laurenlbauer kristen broady , kristen broady nonresident senior fellow - brookings metro @kebroady wendy edelberg , and wendy edelberg director - the hamilton project , senior fellow - economic studies @wendyedelberg jimmy o’donnell jimmy o’donnell former senior research assistant - the hamilton project @jfodonnell13.

September 17, 2020

- 31 min read

The coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic has created both a public health crisis and an economic crisis in the United States. The pandemic has disrupted lives, pushed the hospital system to its capacity, and created a global economic slowdown. As of September 15, 2020 there have been more than 6.5 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and more than 195,000 deaths in the United States (Johns Hopkins University n.d.). To put these numbers into context, the pandemic has now claimed more than three times the American lives that were lost in the Vietnam War (Ducharme 2020; authors’ calculations). The economic crisis is unprecedented in its scale: the pandemic has created a demand shock, a supply shock, and a financial shock all at once (Triggs and Kharas 2020).

On the public health front, the spread of the virus has exhibited clear geographic trends, starting in the densely populated urban centers and then spreading to more-rural parts of the country (Desjardins 2020). Figure A shows the weekly number of deaths caused by COVID-19 in each U.S. region from late February to late August 2020. Early on, COVID-19 cases were concentrated in coastal population centers, particularly in the Northeast, with cases in New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts peaking in April (Desjardins 2020). By April 9 there had been more COVID-19–related deaths in New York and New Jersey than in the rest of the United States combined (New York Times 2020). COVID-19–related deaths then peaked in the New England and Rocky Mountain regions during the third week of April, followed by the Great Lakes region in the fourth week of April, and the Mideast (excluding New York and New Jersey) and the Plains regions during the first week of May. The Southeast, Southwest, and Far West regions all experienced their peaks at the end of July and first week of August.

The COVID-19 crisis has also had differential impacts among various racial and ethnic groups. Inequities in the social determinants of health—income and wealth, health-care access and utilization, education, occupation, discrimination, and housing—are interrelated and put some racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2020c). Inequities in infectious disease outcomes are the byproduct of decades of government policies that have systematically disadvantaged Black, Hispanic, and Native American communities (Cowger et al. 2020). For example, as a result of policies that have helped to determine the location, quality, and residential density for people of color, Black and Hispanic people are clustered in the same high-density, urban locations that were most affected in the first months of the pandemic (Cowger et al. 2020; Hardy and Logan 2020). In addition, Black people and Native American people disproportionately use public transit, which has been associated with higher COVID-19 contraction rates (McLaren 2020).

Relatedly, those demographic groups came into the crisis with a higher incidence of preexisting comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease, which also increase one’s risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 (Yancy 2020; Ray 2020). Compared to white, non-Hispanic Americans, Black Americans are 2.6 times more likely to contract COVID-19, 4.7 times more likely to be hospitalized as a result of contracting the virus, and 2.1 times more likely to die from COVID-19–related health issues (CDC 2020b). While non-Hispanic white people are dying in the largest numbers (CDC 2020a), Black and Hispanic people are dying at much higher rates relative to their share of the U.S. population (see figure B1); moreover, this disparity is true for every age group (figure B2).

While voluntary social distancing and lockdowns that took effect in March 2020 worked initially to isolate and drive down infections, those actions precipitated a severe economic downturn. The demand shock resulting from quarantine, unemployment, and business closures dealt a blow to consumer services (Bartik, Bertrand, Cullen, et al. 2020). Lockdown measures and social distancing reduced the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services (Brinca, Duarte, and Faria-e-Castro 2020; Gupta, Simon, and Wing 2020).

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) determined that a peak in monthly economic activity occurred in the U.S. economy in February 2020, marking the end of the longest recorded U.S. expansion, which began in June 2009 (NBER n.d.). Figure C shows the percent difference in real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) from the peak of a business cycle through the quarter when GDP returned to the level of the previous business cycle peak for recent recessions. From the most recent peak in the fourth quarter of 2019, the United States experienced two consecutive quarters of declines in GDP; it even recorded its steepest quarterly drop in economic output on record, a decrease of 9.1 percent in the second quarter of 2020 (Bureau of Economic Analysis [BEA] 2020a; authors’ calculations). To put this contraction into historical context, quarterly GDP had never experienced a drop greater than 3 percent (at a quarterly, nonannualized rate) since record keeping began in 1947 (Routley 2020).

Figure D shows the percent change in employment relative to business cycle peaks. COVID-19–related job losses wiped out 113 straight months of job growth, with total nonfarm employment falling by 20.5 million jobs in April (BLS 2020b; authors’ calculations). The COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic shutdown created a crisis for all workers, but the impact was greater for women, non-white workers, lower-wage earners, and those with less education (Stevenson 2020). In December 2019 women held more nonfarm payroll jobs than men for the first time during a period of job growth; by May 2020 that relationship was reversed, in part reflecting job losses in the leisure and hospitality industry, where women account for 53 percent of workers (Stevenson 2020).

The COVID-19 crisis also led to dramatic swings in household spending. Retail sales, which primarily tracks sales of consumer goods, declined 8.7 percent from February to March 2020, the largest month-to-month decrease since the Census Bureau started tracking the data (U.S. Census Bureau 2020a). Although some areas (e.g., grocery stores, pharmacies, and non-store retailers) saw increases in demand as lockdown measures began, others (e.g., clothing stores, furniture and appliances stores, food services and drinking places, sporting and hobby stores, and gasoline stations) saw declines. In early May, as some states lifted social distancing restrictions, sales began to recover in most goods sectors (U.S. Census Bureau 2020a). Overall, U.S. retail sales increased 17.7 percent from April to May, the largest monthly jump on record, recouping 63 percent of March and April’s losses (U.S. Census Bureau 2020a). Growth in retail sales continued through the summer: by August, retail sales were 2.6 percent above their August 2019 level (U.S. Census Bureau 2020a).To help put those swings in such spending into historical context, figure E shows the percent change in real advance retail and food sales from the peak of a business cycle during recessions between 1980 and 2020.

In addition to consumer spending, the COVID-19 crisis has damaged the nation’s industrial production (i.e., output in the manufacturing, mining, and utility sectors). As shown in figure F, U.S. industrial production dropped sharply in March and has since only partially rebounded. This decline poses a host of challenges for the U.S. manufacturing sector, which employs nearly 13 million workers (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis [FRED] 2020a), especially those that depend on workers whose jobs cannot be carried out remotely.

The effects of the crisis vary by industry subsector, with the construction machinery subsector having experienced less-severe effects than it faced during the 2007–09 financial crisis due to expected government infrastructure stimuli and an increase in e-commerce, while companies in the machine tools, plastics machinery, and steel production equipment sectors have been more negatively affected (Kronenwett 2020). In addition, the partial rebound in industrial production was boosted by a 107 percent increase in auto production in June 2020 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2020, table 1).

Six months into the COVID-19 crisis, we present 10 facts about the state of the U.S. economy. We highlight effects that COVID-19 has had on businesses, the labor market, and households. We conclude by considering how policy has supported businesses and families since March 2020. Taken together, these facts describe a joint economic and public health crisis of a scale and at a speed unprecedented in the history of the United States.

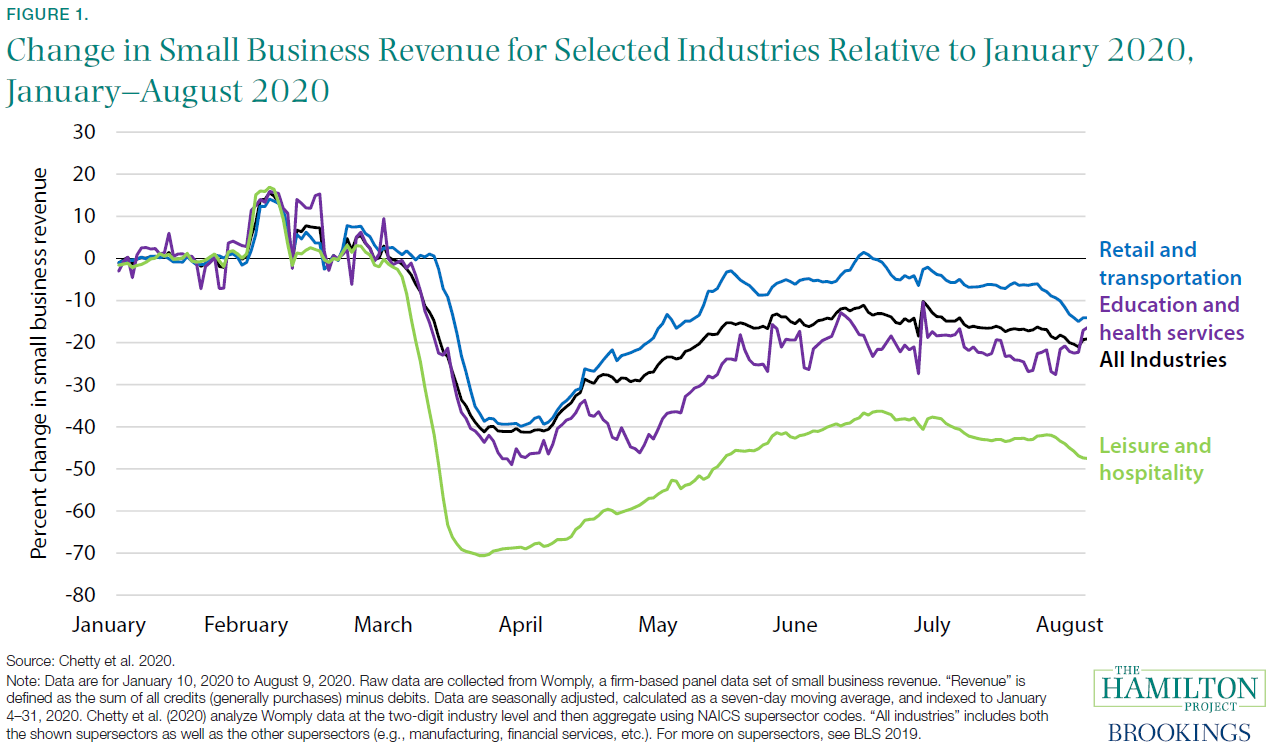

Fact 1: Small business revenue is down 20 percent since January.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly damaging for small businesses, which represent the majority of businesses in the United States and employ nearly half of all private sector workers (Bartik, Bertrand, Cullen, et al. 2020; Small Business Administration 2012). Figure 1 shows how the different small business sectors have been affected by this downturn, highlighting severe declines in revenue among the leisure and hospitality as well as education and health services sectors. Compared to January 2020, average daily revenue as of August 9 was down by 47.5 percent in the leisure and hospitality sector, 16.4 percent in the education and health services sector, and 14.1 percent in the retail and transportation sector; aggregate small business revenue across all industries had fallen by 19.1 percent

Some sectors where employees could not work remotely and where businesses were not deemed essential to be open fared particularly poorly (Papanikolau and Schmidt 2020). Notably, some of these sectors, after partially rebounding, have begun to see revenue declines again starting in August. For example, the percent reduction in revenue fell by more than 5 percentage points in the first 10 days of August in the retail and transportation sector as well as in the leisure and hospitality sector.

In line with these declines in revenue, significant declines in employment at the beginning of the recession were seen in small businesses. Between March and April, employment in firms with fewer than 20 employees fell more than 16 percent; for firms with between 20 and 49 employees, the decline was 22 percent (Wilmoth 2020). Between August 30 and September 5, 50 percent of respondents had not rehired any employees, 5 percent of respondents had rehired at least one employee and 55 percent of respondents had not furloughed or laid off any employees (Small Business Pulse 2020).

There is, of course, substantial uncertainty in these calculations. A major source of uncertainty is the extent of climate change over the next several decades, which depends largely on future policy choices and economic developments—both of which affect the level of total carbon emissions. As noted earlier, this uncertainty justifies more aggressive action to limit emissions and thereby help insure against the worst potential outcomes.

Stabilizing business revenue is crucial—not only to avoid costly layoffs and firm closures, but also because reduced revenue will result in diminished investment, which can compound the future output and income damages of a recession (Boushey et al. 2019); for example, following declines in revenue during the Great Recession, real private nonresidential fixed investment fell 16 percent (FRED 2020c). For a Hamilton Project proposal on how to provide small businesses with relief in this crisis, see Hamilton (2020).

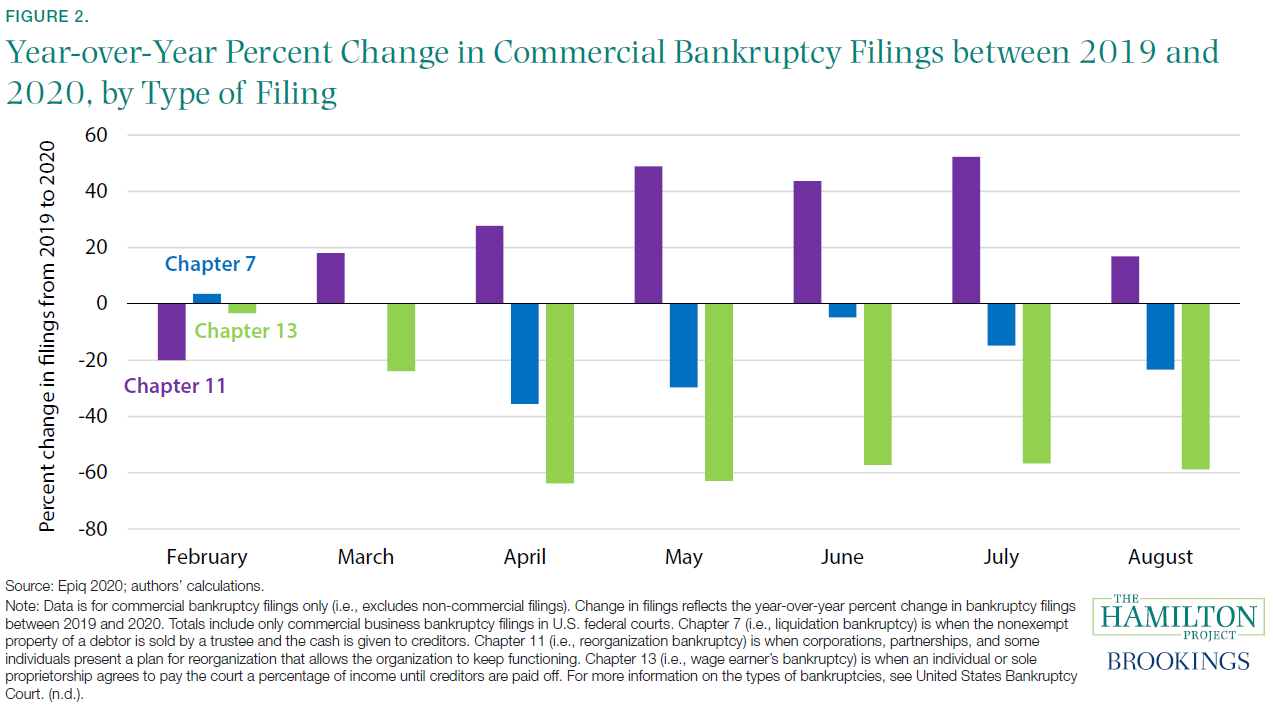

Fact 2: So far, only Chapter 11 bankruptcies have increased relative to last year.

The decline in business revenue has caused many firms to become insolvent. Hamilton (2020) estimates that by July nearly 420,000 small businesses had failed since the start of the pandemic, the number of failures typically seen in an entire year. Nevertheless, Wang et al. (2020) find that total bankruptcies are down 27 percent year-over-year between January and August. Breaking it out by type of filing, figure 2 shows how the filing of bankruptcies has changed since February 2020 from the same month last year. Chapter 11 bankruptcies—in which a plan for reorganization is negotiated—were down in February when the economy was relatively strong. Since March, such bankruptcies have regularly been between 15 percent and 50 percent higher than in the same month last year. Although larger firms benefit from entering into Chapter 11 bankruptcy in order to reorganize their operations, many smaller businesses opt for outright closures. Chapter 7 bankruptcies—in which the assets of the debtor are liquidated and used to pay creditors—decreased sharply from the same time last year in April and May and have remained below their 2019 levels through August. Finally, Chapter 13 bankruptcies—for individuals or sole proprietors who agree to pay a percentage of their income until creditors are paid off—have been down by about 60 percent from the same month in the previous year since April.

Court closures resulting from the virus have had significant effects on bankruptcy filings, with many negotiation meetings cancelled, court proceedings delayed, and lawyers holding off on bringing large cases (Church 2020). 1 In addition to logistical challenges that have likely delayed bankruptcies, many owners of businesses that are closed or suffering large reductions in revenue are likely waiting to file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. Firms that rely on financial institutions and markets for financing face curtailed access to credit (Federal Reserve Bank 2020). The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis finds that firms under those conditions during the Great Recession were more likely to declare bankruptcy. In all, conditions point to a coming wave of bankruptcies (Famiglietti and Leibovici 2020).

Firm closures can sometimes be the result of efficient market reallocation (Barrero, Bloom, and Davis 2020). Indeed, Bartik, Bertrand, Lin, et al. (2020) show that small businesses that were struggling in 2019 were the most likely to close early in the pandemic and the least likely to reopen. Nonetheless, this crisis will no doubt lead to the failure of viable, productive businesses; letting these businesses fail is costly to the economy (Hamilton 2020).

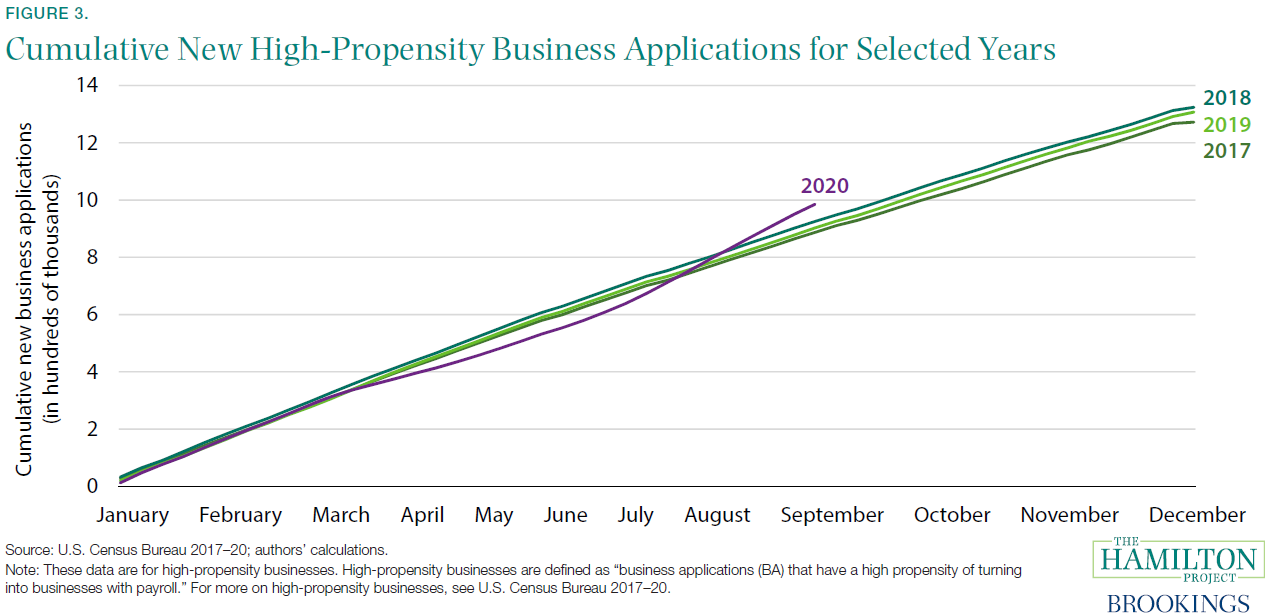

Fact 3: New business formations fell off in the spring, but are on track to outpace recent years.

At the same time that business closures spiked in the spring, business formations lagged behind pre-crisis levels in the early months of the pandemic. More recently, business formations have begun to increase. Figure 3 shows how many new high-propensity businesses (i.e., those new businesses that are most likely to become employers) filed applications in recent years. By early June 2020 cumulative high-propensity business formations were 4.4 percent lower than they were at the same time in 2019; however, by mid-August there were actually 56 percent more new business applications than in mid-August 2019.

Business formations tend to decline during recessions (Boushey et al. 2019); in the current recession, public health conditions worked to depress business formation as well. For example, Sedláček and Sterk (2020) find that states with a larger number of COVID-19 deaths tended to have fewer high-propensity business applications

Since mid-summer, high-propensity business applications have rebounded. The Economic Innovation Group (EIG) offers three potential explanations for this recent increase: (1) there could have been a backlog in the processing of new business applications as a result of the same court closures discussed in fact 2, (2) newly unemployed persons might be starting their own businesses, and (3) some entrepreneurs could be trying to capitalize on potential reallocation or other opportunities occurring in the market (EIG 2020). There is some evidence that business creation has been boosted by demand for new kinds of goods: our analysis shows that many states with heavy manufacturing bases have seen the fastest rebounds (not shown). At the same time, 14 states still trail last year’s pace of business formation (Business Formation Statistics 2020; authors’ calculations).

Continuity in business formation is critical for long-term growth. Sedláček (2020) finds that the “lost generation” of firms during the Great Recession led to significant output loss: if firm entry had remained constant instead of falling, the economy would have recovered four to six years earlier and the unemployment rate would have been 0.5 percentage point lower even 10 years after the trough. Long term, a 1 standard deviation shock to the number of start-ups (resulting in an initial decrease in start-ups of about 10 percent) results in a 1–1.5 percent drop in real GDP that can last 10 years or longer (Guorio, Messer, and Siemer 2016). For more on the significance of entrepreneurship and innovation in the U.S. economy, see prior Hamilton Project work (e.g., Shambaugh et al. 2018).

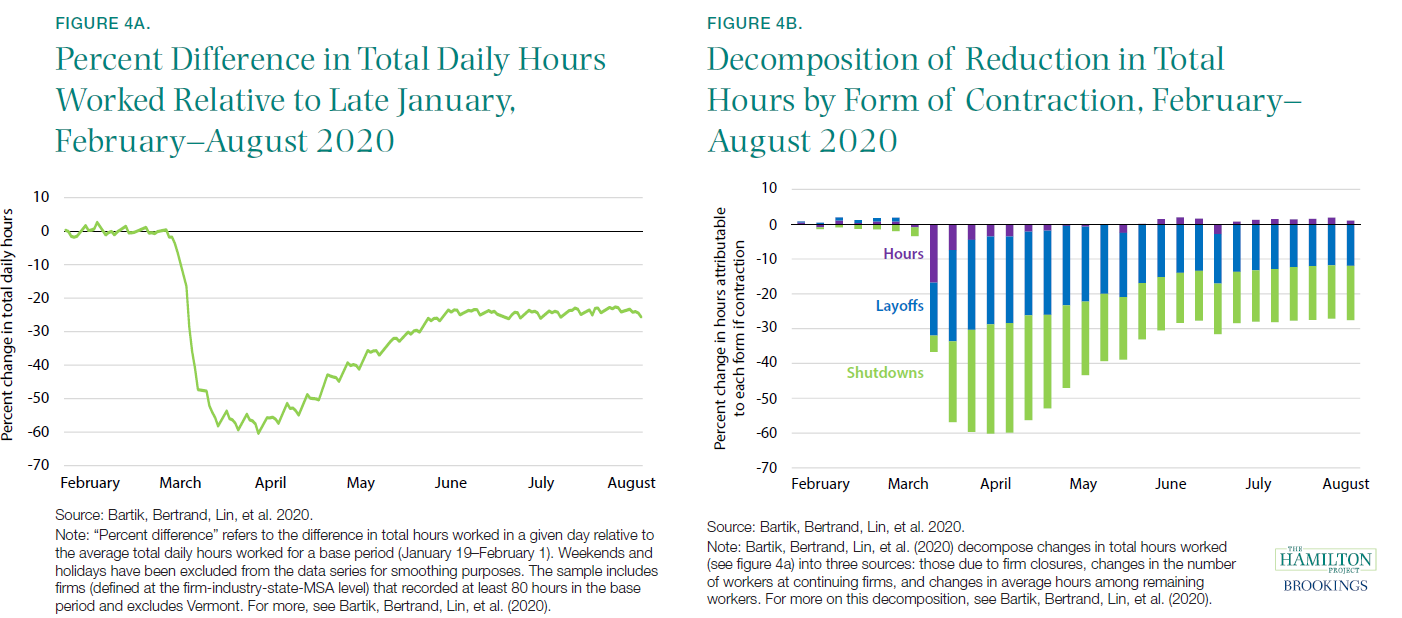

Fact 4: Layoffs and shutdowns—and not reduced average hours—are driving in total hours worked.

The labor market devastation caused by this pandemic has been the quickest and most severe in recent U.S. history. Many firms reacted to the COVID-19 pandemic by reducing their operations. Figure 4a shows the decline in total hours worked using data from Homebase, a firm that provides scheduling and time clock software to service-sector clients (e.g., food services, retail). 2 Figure 4a shows the daily change in total hours worked from February through July, relative to a base period (January 19–February 1). The total number of hours worked fell by about 60 percent in March. While the number of daily hours began to rise again in mid-April, they leveled off at around 25 percent below baseline in June. Since then, aggregate hours have remained at between 25 and 30 percent of their baseline level.

Figure 4b shows Bartik, Bertrand, Lin, et al.’s (2020) decomposition of the reduction in total hours from figure 4a into (1) average hours worked by a worker, (2) layoffs, and (3) establishment or firm shutdowns. Their analysis shows that, beginning in late March, the reduction in total hours was primarily driven by layoffs and establishment shutdowns. That is, the observed reduction in hours has not been driven by cutting hours among workers, but by reduced employment and temporary furloughs. Relatedly, worker recall is where much of the gain in hours has come since the April nadir. Cajner et al. (2020) find that the reopening businesses, especially small firms like those observed in the Homebase data, were major contributors to post-April employment gains.

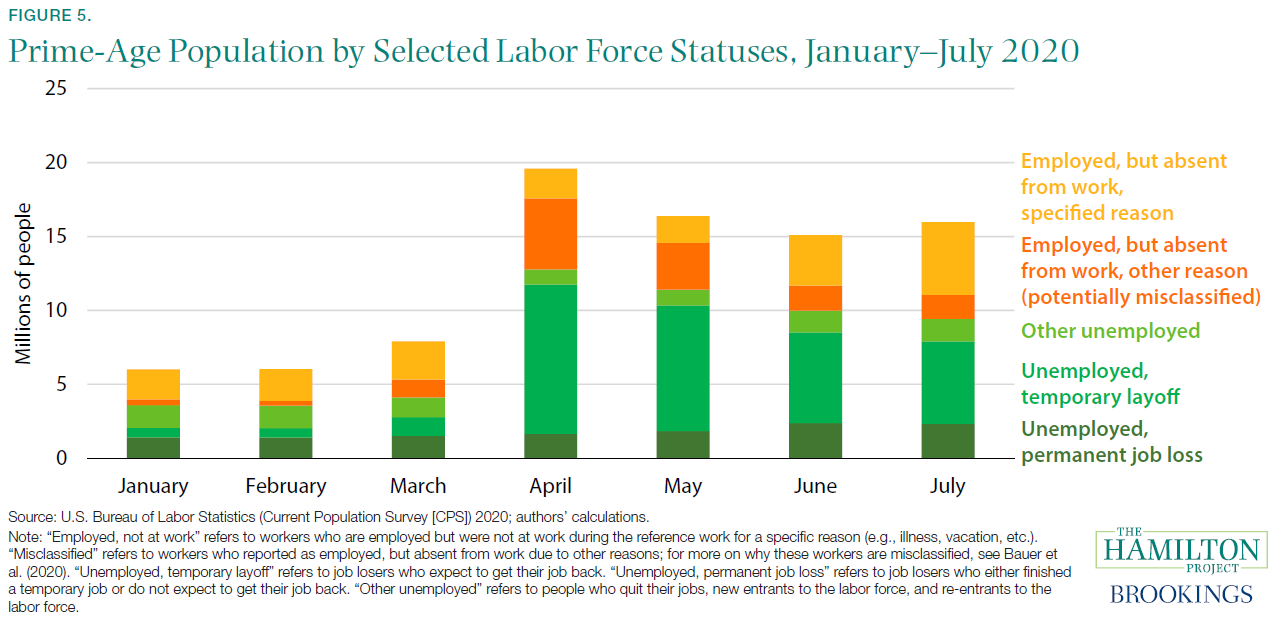

Fact 5: The number of labor force participants not at work quadrupled from January to April.

During economic contractions, the share of the population that is employed declines. Figure 5 shows the number of workers in selected labor force statuses from January to July. From March to April, the number of prime-age people participating in the labor force but not working (i.e., either unemployed or employed but not at work) rose from 7.9 million to 19.6 million. That increase was largely driven by a 10.3 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate (FRED 2020d).

As shown in figure 5, an unusual phenomenon in April and May was the surge in labor force participants that were counted as employed but not at work. These workers were either absent from work for a reason (e.g., vacation, child care) or absent from work for “other” reasons; recent research has suggested that this latter group largely misclassified themselves as being employed, suggesting an even higher share of the population was out of work (Bauer et al. 2020).

Early in the recession, the majority of those who were not at work—either those who were unemployed or those employed but not at work—described their circumstances as temporary. Temporary layoffs are less damaging then permanent layoffs because they represent a much higher chance of reemployment since the employer–employee relationship is maintained (Fujita and Moscarini 2017; Nunn and Parsons 2020). In April, 10.1 million were unemployed on temporary layoff, 4.8 million were potentially misclassified as employed but absent from work for “other” reason, and 2.0 million were employed and absent from work for a specific reason. Altogether, these people represented 86.3 percent of prime-age labor force participants not at work in April.

In May, June, and July, these three categories accounted for a smaller share of labor force participants who were not at work. Instead, a rising number of people not at work have classified themselves as being on permanent layoff. In April, the number who were unemployed due to a permanent job loss was 1.6 million, up only modestly from the number prior to the recession and representing 6.5 percent of those unemployed or employed but not at work. In July, 2.3 million were unemployed due to permanent layoff, which was 11.8 percent of those either unemployed or employed and not at work.

More permanent layoffs suggest more people being unemployed for longer periods. Chodorow-Reich and Coglianese (2020) project that, by February 2021, 4.5 million individuals will have been unemployed for more than 26 weeks, and almost 2 million individuals will have been unemployed for more than 46 weeks. Long-term unemployment can lead to lower future earnings and reduced rates of homeownership (Cooper 2013).

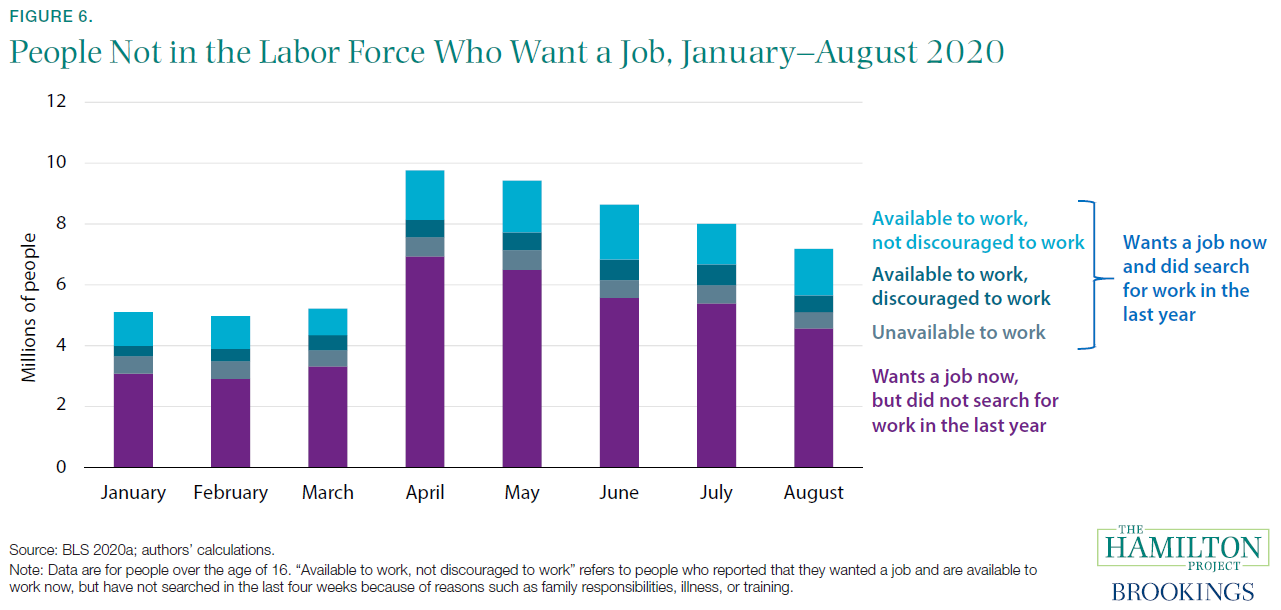

Fact 6: The number of people not in the labor force who want a job spiked by 4.5 million in April and has remained elevated.

While many of the millions of people who are no longer employed are counted as unemployed (as highlighted in fact 5), a significant portion have dropped out of the labor force altogether. Figure 6 shows the number of persons not in the labor force but who say they want a job. The size of that group grew by 4.5 million in April, as the group includes those who lost their jobs in March and did not look for work in April (and thus were classified as not in the labor force). Within the group of people out of the labor force but who want a job, 6.0 percent reported being discouraged by their labor market prospects and 16.7 percent reported having another reason for not looking for work. The increase between March and April in those not in the labor force but who want a job was particularly large among adults of prime working age (25-54): 2.5 million (BLS 2020a; authors’ calculations). These numbers have remained elevated since April. To put this into context, the unemployment rate in August was 8.4 percent; however, using an alternative measure of unemployment that also includes people not in the labor force who want a job and are available to work—both discouraged and not discouraged workers (i.e., U-5)—the rate was 9.6 percent in August.

Many of those reporting being out of the labor force but wanting a job have not been looking for work because of reasons that include child-care responsibilities, issues with transportation, or illness. The size of that group has risen steadily, from 867,000 in March to 1.8 million in June, but then fell slightly to 1.5 million in August. As highlighted in Stevenson (2020), disruptions in child care have led many working parents to drop out the labor force, a development that (without significant policy intervention) could have long-lasting negative effects on labor market outcomes for years to come.

As was true before the pandemic, the majority of those not in the labor force do not want a job; not shown in figure 6 are the roughly 90 million Americans who said they did not want a job (BLS 2020a). This group, which consists largely of students, family caretakers, retirees, and people with illnesses, became larger in April and May, with some evidence suggesting that the pandemic pushed workers over the age of 54 into retirement. For example, among people who were employed in January but out of the labor force in April, 28 percent who offered a reason why they had left the labor force said they were retired (Coiboin, Gorodnichenko, Weber 2020).

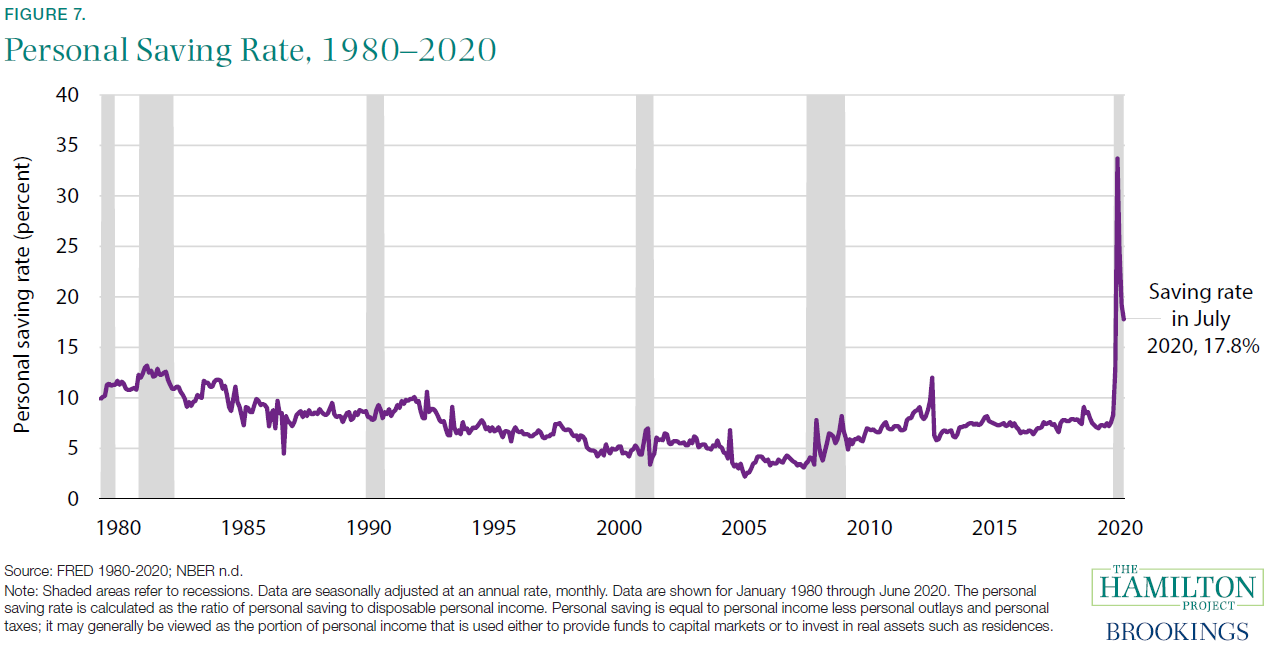

Fact 7: In April 2020 the U.S. personal savings rate reached its highest recorded level.

One of the immediate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic was a sharp decline in aggregate spending and a sharp increase in savings. Figure 7 shows the personal saving rate, which is the ratio of personal saving to disposable personal income. The personal saving rate peaked at 34 percent in April, its highest level in recorded history. It has decreased since then but remains significantly elevated. That increase has been the result of both lower spending and greater federal transfer payments.

Just as it did across the world (Andersen et al. 2020; Bounie, Camara, and Galbraith 2020; Carvalho et al. 2020), spending in the United States dropped following COVID-19–related shutdowns (Coiboin, Gorodnichenko, Weber 2020). Spending on many types of goods and services fell immediately as the pandemic emerged. Nevertheless, some categories of goods spending saw initial increases and most categories of goods spending have rebounded since March; for example, spending on groceries was strong early in the pandemic, with women, households with children, and older households stockpiling more supplies (Baker al. 2020). Although goods spending has recovered to pre-pandemic levels, spending on services remains sharply down through July (BEA 2020c).

Through July, the saving rate was also boosted by stimulus payments to households, including unemployment insurance benefits and other federal transfers to households. As a result of those payments, even as millions of workers have lost their jobs, disposable personal income from March to July exceeded pre-pandemic levels (FRED 2020b). Although evidence suggests that many low-income households spent their stimulus checks immediately, other income groups said they planned to save the money (Baker et al. 2020; Chetty et al. 2020;), and low-income households were more likely to save their overall monthly income relative to prior periods (Bachas et al. 2020; Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Weber 2020). Furthermore, Bachas et al. (2020) find evidence of sizeable growth in liquid asset balances for many households whom the federal support reached, suggesting the importance of the initial stimulus and insurance programs in limiting the effects of labor market disruptions on households’ financial positions. For low-income households whom the federal support has not reached, financial circumstances have been dire.

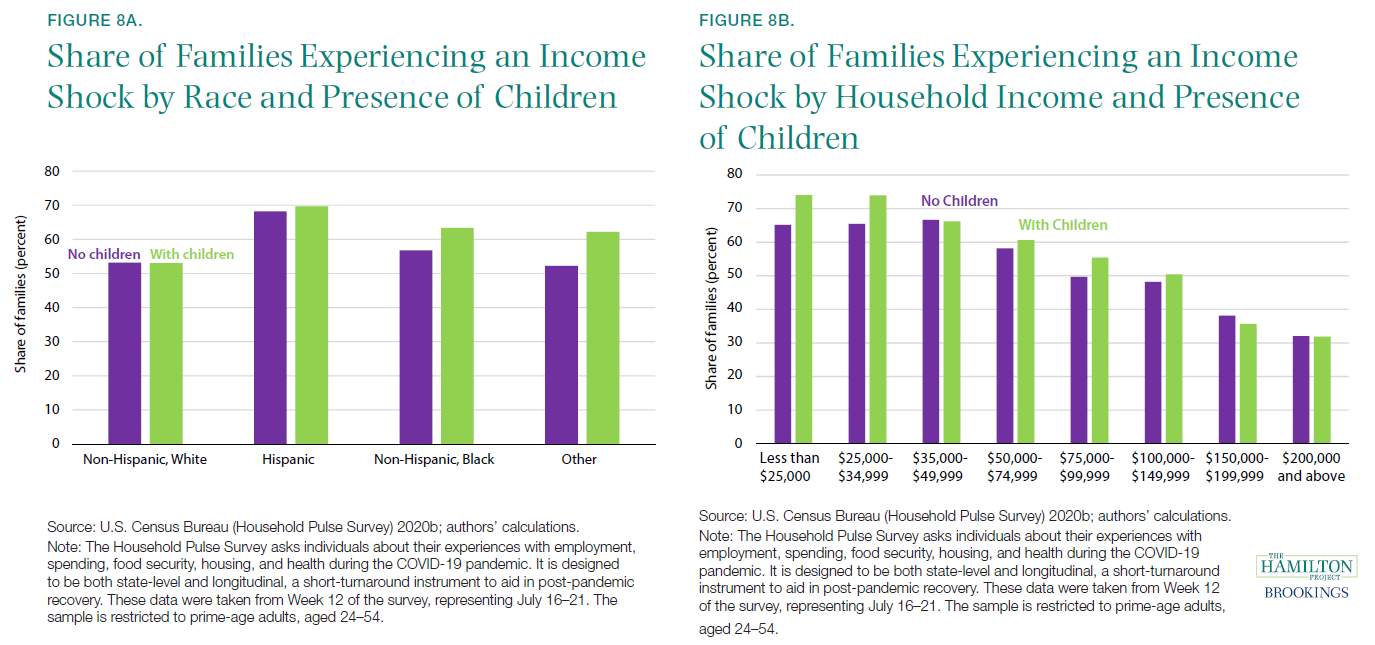

Fact 8: Low-income families with children were most likely to experience an income shock.

During the COVID-19 recession, job loss and labor income loss have not been experienced equally. Since March, low3-income households, non-white households, and households with children were most likely to experience an income shock (Monte 2020). Figures 8a and 8b shows these patterns in late July.

About half of Black and Hispanic households experienced an income shock recently (see figure 8a). Hispanic families with and without children are most likely to experience an income shock. Lopez, Rainie, and Budimen (2020) found that 61 percent of Hispanic adults said in April that they or someone in their house had experienced a job or wage loss. Ganong et al. (2020) examine the racial gaps in consumption smoothing following an income shock, and find that the welfare cost of income volatility (i.e., how much a household cuts consumption following an income shock) is 50 percent higher for Black households and 20 percent higher for Hispanic households than it is for white households.

More than three out of five low-income households with children reported that they had experienced an income shock due to COVID-19 (figure 8b; authors’ calculations). Income losses related to COVID-19 are associated with a host of material hardships, including food insecurity and difficulty paying bills (Despard et al. 2020). Families with children are also vulnerable to falling behind on obligations: each additional child in a household increases the likelihood of a serious delinquency (being at least two months behind on a current loan obligation) by 17 percent (Ricketts and Boshara 2020).

Fact 9: In 26 states, more than one in five households was behind on rent in July.

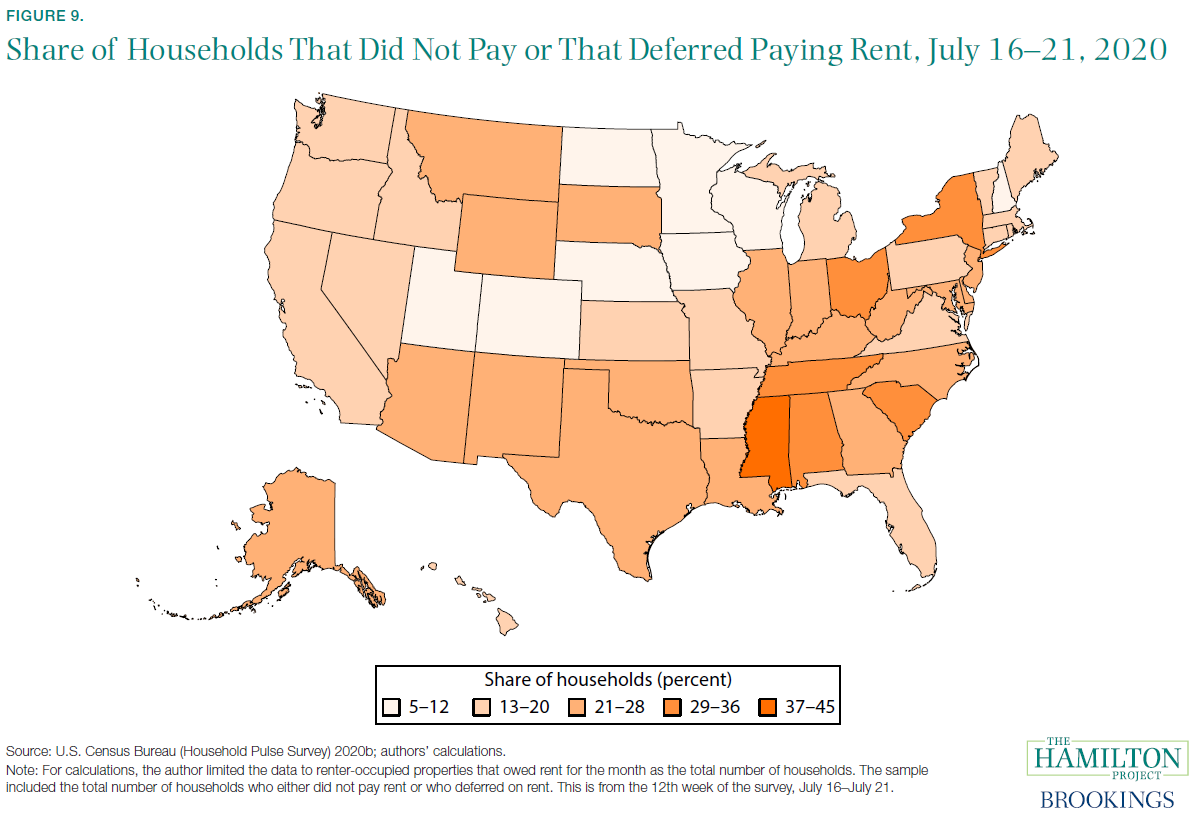

Although the increase in federal payments to households and unemployed workers has been relatively generous, it has not been able to cover all expenses for struggling households. Focusing on renters surveyed in late July, figure 9 shows that in 26 states more than one-fifth of renting households had not yet paid their rent for June, and that in five of those states (including New York) one-third of households had not yet paid their rent.

According to a survey by Apartment List, missed payments were concentrated among young and low-income households as well as residents of densely populated urban areas. With late fees added on, households who miss a rent payment in a given month may be more likely to be unable to afford their next housing payment, creating a vicious circle of delinquency and putting households at risk for eviction (Adamcyk 2020). In addition, renters (as compared to home owners) are less likely to receive federal support for housing costs (Amherst Market Commentary 2020).

For many households, unemployment coincided with having less than two month’s income in liquid assets and having high debt-to-income ratios (Kolomatsky 2020). In an April 2020 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, 73 percent of Black adults and 70 percent of Hispanic adults indicated that they did not have emergency funds to cover three months of expenses, compared to 47 percent of white adults (Lopez, Rainie, and Budimen 2020). Furthermore, Black and Hispanic respondents also said they would not be able to cover these expenses by borrowing money, using savings, or selling assets (Lopez, Rainie, and Budimen 2020).

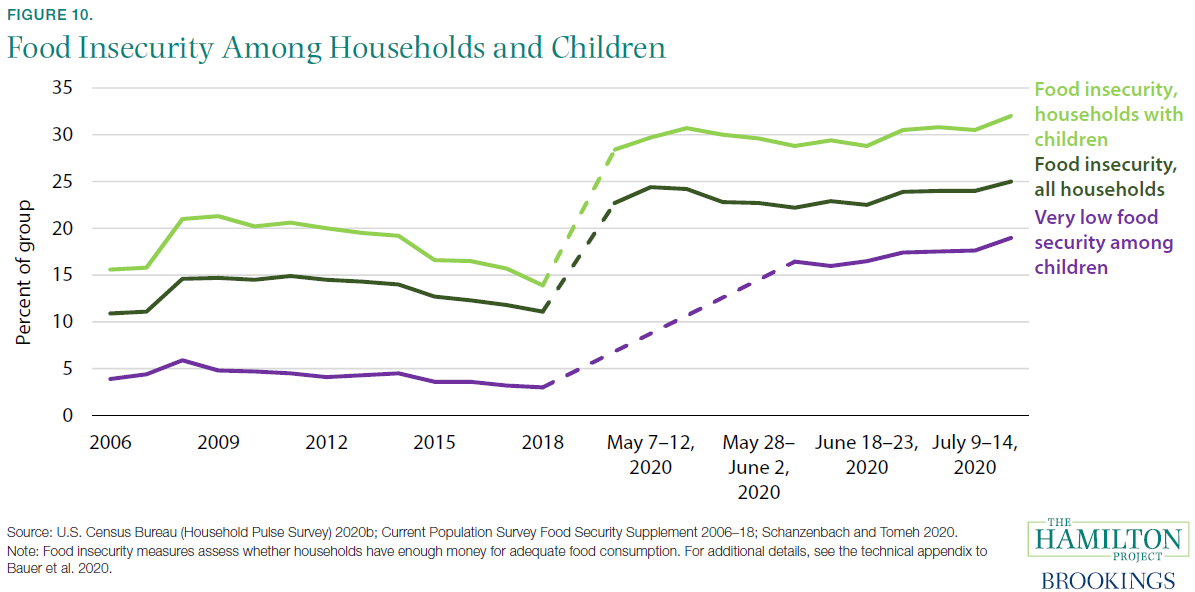

Fact 10: From 2018 to mid-2020, the rate of food insecurity doubled for households with children.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of food insecurity and of very low food security among households with children have increased (see figure 10). Food insecurity occurs when a household does not have sufficient food for its members to maintain healthy and active lives and lacks the resources to obtain more food. Very low food security is akin to hunger and captures whether there is a significant or consistent disruption in food consumption. Notably, the current levels of food insecurity are above their Great Recession peaks.

Food insecurity is particularly high among households with children. In fact, it has doubled since before the pandemic, growing from roughly 14 percent in 2018 to about 32 percent of households in July 2020 (see figure 10). These rates are even higher for Black and Hispanic households (Schanzenbach and Pitts 2020), and Black and Hispanic households with children (Bauer 2020).

Typically, families experiencing food insecurity are able to nonetheless maintain food security for their children; but this does not seem to be the case today (Coleman-Jenson et al. 2020). In June and July, rates of very low food security among children worsened, increasing from 16.4 percent in the first week in June to 19.0 percent by the third week of July.

Several policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have supported households’ food security. Pandemic EBT, a disaster response program that provided the value of lost school meals to eligible households as a grocery voucher, reduced very low food security among children by 30 percent (Bauer et al. 2020). Unemployment Insurance receipt and SNAP emergency allotments also reduced food insecurity (Bitler, Hoynes, and Schanzenbach 2020; Raifman, Bor, and Venkataramani 2020).

We conclude this set of economic facts with a discussion of the federal policy response to COVID-19. The fiscal policy response to the pandemic has taken two primary tacks: (1) aid to business, and (2) aid to households and unemployed workers. A series of laws—notably The Families First Act and The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) Act—authorized hundreds of billions of dollars in direct support to firms and to families.

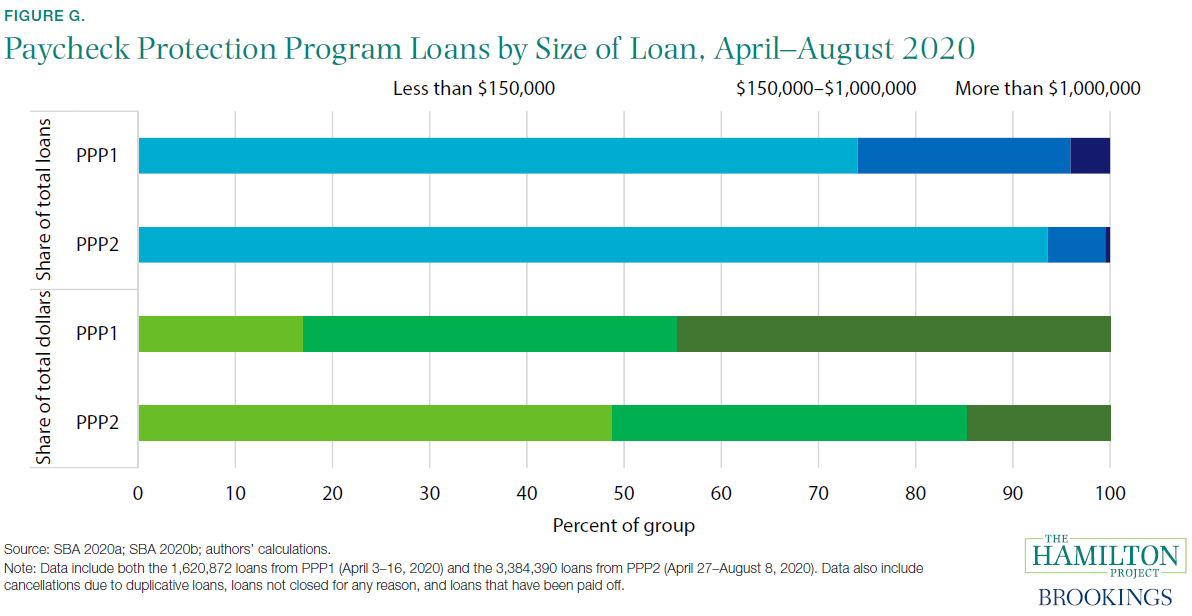

The major program in the CARES Act providing relief to small businesses is the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). According to the Small Business Pulse Survey, 73.5 percent of small businesses surveyed requested financial assistance from the PPP; 25.6 percent requested economic injury disaster loans; and 13 percent requested small business administration loan forgiveness between March 13 and September 5. As described in Hamilton (2020), the PPP was initially allocated $349 billion to offer loans to small businesses, with such loans being forgiven if businesses retained workers and maintained payroll. The program was significantly oversubscribed at first, and larger businesses—who requested larger loans—disproportionately received funding. In particular, although loans for over $1 million only represented 4 percent of all loans processed in the first round of PPP, they represented 45 percent of all dollars disbursed (figure G). As a result, an additional $310 billion was allocated to the PPP, nearly half of which had been disbursed by early August; this second round resulted in a greater number of smaller loans to smaller businesses: as shown in figure G, in the second round of PPP loans under $150,000 accounted for 94 percent of all loans processed and 49 percent of all dollars disbursed.

Empirical evidence on the effect of the PPP in maintaining employment has been mixed, although the range of results generally show a positive effect. For example, about 50 percent of recipients reported retaining between one and five jobs as a result of the program, whereas about 10 percent reported retaining no jobs (SBA 2020; authors’ calculations). One study examining a broad range of firms estimated that the PPP led to 2.3 million jobs being maintained through early June, or for about eight weeks (Autor et al. 2020). Another study examining firms with relatively low wages found no employment effect (Chetty et al. 2020), and attributed the lack of effect to the fact that firms that offer professional, scientific, and technical services received a greater share of loans than firms providing food services.

PPP loans increased business’s expected survival probability by between 14 and 30 percentage points (Bartik, Bertrand, Cullen, et al. 2020). While administering the loans via private banks allowed for rapid disbursement of funds, it meant that businesses with pre-existing connections with banks were more likely to benefit from the program (Bartik, Bertrand, Cullen, et al. 2020). Humphries, Neilson, and Ulyssea (2020) found that of businesses that applied for the PPP, smaller businesses applied later, faced longer processing times, and were less likely to have their applications approved. Relatedly, Granja et al. (2020) found that PPP funds went disproportionately to areas less affected by the pandemic: 15 percent of establishments in the most-affected areas received loans while 30 percent of those in the least-affected areas received them. These issues together with PPP’s “firstcome, first-served” design disadvantaged small businesses.

As Hamilton (2020) makes clear, while the PPP supported many small businesses in the spring and early summer, the support was temporary. It was not sufficient to keep small businesses viable through the pandemic. Small businesses are now in dire straits and in need of further assistance.

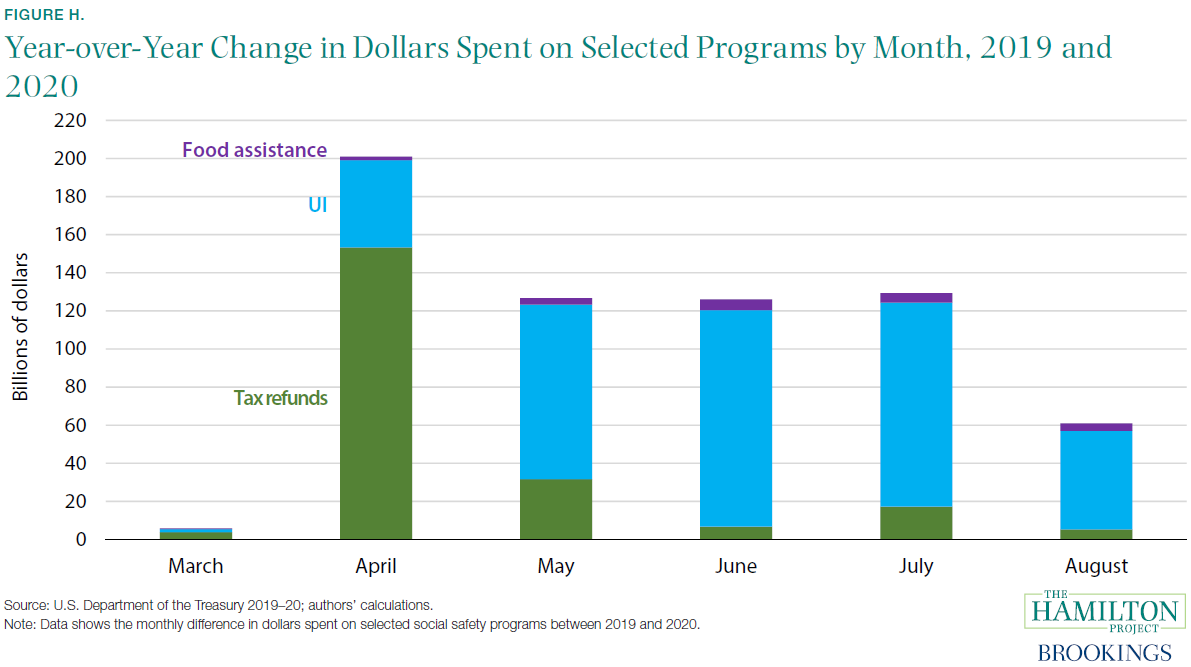

Initially, there was an unprecedented level of federal resources provided to households, largely through one-time stimulus payments and expanded unemployment insurance (UI) payments. As a result of those payments, disposable personal income was nearly 10 percent higher in the second quarter of 2020 relative to the first quarter, even though employee compensation fell almost 7 percent (BEA 2020b).

The Families First Act and CARES Act included stimulus payments for households based on income, expanded UI eligibility, an increase of $600 in UI payments to recipients, increases in SNAP benefits to those households not receiving the maximum benefit, and direct payments to families with children eligible for free or reduced-price school meals to make up for missed school meals.

Figure H highlights the increase in new federal outlays from these three sets of disbursements to households by month from March to August by subtracting 2019 outlays for these categories from 2020. As shown in figure H, there was an increase in tax refunds and other IRS payments to households of more than $140 billion in April, with additional increases in later months for households whose stimulus payments were delayed. (It is also likely that the increase in July reflects the delay in the tax filing date.) In addition, UI payments totaled nearly $46 billion in April, and then averaged $104 billion from May through July. In August, UI payments fell sharply, to $52 billion, as the additional $600 weekly payment to recipients expired. The combination of higher SNAP participation, SNAP emergency allotments, and PandemicEBT resulted in total spending on food assistance averaging around $3.4 billion per month. Other temporary measures in the CARES Act that supported households included student loan forbearance and prohibitions on most foreclosures and evictions.

Mounting empirical evidence shows that the extraordinary support for households and unemployed people supported spending and economic growth in recent months (Casado et al. 2020). According to an economic analysis by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, for every dollar of stimulus, households increased spending by 25–35 cents (Robbins 2020).

Going forward, the expiration of the $600 weekly payment to UI recipients will be a drag on consumer spending (even as some recipients became eligible for a temporary increase in payments of $300 a week). In addition, recent evidence suggests the generous UI benefits through July did not constrain the supply of labor and so the expiration of those benefits did not provide a boost to labor supply and employment (Altonji et al. 2020; Marinescu, Skandalis, and Zhao 2020). With wages and salaries down 5 percent from February to July, households continue to need substantial federal support (Bitler, Hoynes, and Schanzenbach 2020).

Indeed, the abrupt lapse in support for firms, households, the unemployed, and families with children threatens a nascent and fragile economic recovery and stands to do long-term and permanent damage. The greater the economic damage during the pandemic, the more protracted the recovery will be once the pandemic is over. Given the cost to life and livelihood of a weak economy and labor market, policymakers must continue to use the fiscal, monetary, and public health tools at their disposal to end the COVID-19 pandemic and hasten a self-sustaining economic recovery.

Fiscal support to firms and families flowed promptly, with notable exceptions. Black applicants faced significant delays in receiving UI, and the smallest businesses without preexisting relationships with banks struggled to receive PPP (Schanzenbach et al. 2016; Grooms, Ortega, and Rubalcaba 2020). And while existing automatic stabilizers have sprung into action given the speed of the economic collapse, much more could be done to extend augmented countercyclical fiscal policy forward in time to help sustain the recovery (Boushey, Nunn, and Shambaugh 2019). The federal government’s failure to act since March—to suppress the spread of COVID-19, to improve automatic stabilizers, to extend fiscal relief—is to our collective detriment. The Hamilton Project’s mission is to provide evidence and policy proposals based on the judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering economic growth and broad participation in that growth. Federal fiscal policy can and should do more—urgently—to support those goals.

1. While many courts reopened in May, they began to cancel jury trials and in-person proceedings again in June as cases surged (United States Courts 2020). 2. Bartik, Bertrand, Lin, et al. (2020), who also rely on Homebase data, show that, despite Homebase’s concentrated clientele, the data are broadly representative of the sectors most acutely affected by the pandemic (i.e., industries that rely on in-person interaction and cannot easily transition to remote work).

Economic Studies

The Hamilton Project

Michael J. Ahn

May 13, 2024

Jenny Schuetz, Gary Geiler, Adrianna Pita

Brookings Institution, Washington DC

9:00 am - 1:15 pm EDT

The History of the American Economy: From Zero to One of the Largest Economies in the World Essay

Introduction, current economic situation, republicans, works cited.

Economy is defined as the activities surrounding the production and distribution of goods and services in a given geographical area. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the measuring index for economies. Under this measure, the United States of America is the single largest country economy and is about a quarter of the world’s economy according to the CIA World Fact book. Although the democrats and the republican are differently opinionated over decisions on the economy, they both ultimately aim to improve it and the differences are just politics.

Right from the formation the first federal government of the George Washington in the late 1700s, divisions on how to best run the economy emerged. Prominent differences were between the then Secretary of treasury Alexander Hamilton, a republican federalist, and Secretary of state Thomas Jefferson a democratic federalist.

Hamilton made several proposals to Congress to curtail the financial strain and to boost the struggling economy. Although these were passed, they were opposed by the Jefferson’s group. To begin with, all debts from issuing of bonds to both foreign and domestic holders were paid off. The federal government then assumed individual state debts. In so doing, creditors were now required to deal with the national government. This move was intended to increase the individual state’s obligations to the federal government. Hamilton further proposed to Congress that the Bank of the United States be created. This is what is today referred to as the Federal Reserve (Oates et al. 109). During that period, Congress had no constitutional authority to ratify a charter for the establishment of a bank. It however had authority to do anything “necessary and proper” to carry out its delegated duties (Berkin et al. 218). The constitution therefore implied Congress could establish a bank (Billington, 94). Jefferson opposed this on the grounds that it was unconstitutional and therefore illegal with support from James Madison, a prominent democrat. The banks’ purpose was to handle repository of national assets, issue paper money based on assets and source investment capital (Hofstadter 56).

The current controversy over the U.S economy within the political cycles is the U.S budget. Issues around it include the bail out packages that were handed out in the midst of the financial meltdown, and the proposed taxation methods. Differences also emerge in the priority of expenditure. The democrats and the republicans, like on many other issues such as health and foreign policies, have taken different stands on the economy. It all started with the crash of the housing markets. Like the great depression, over speculation by financial institutions on high risk loans after decades of relative stability finally collapsed. These loans were invested mainly in real estate and in the stock market due to the high returns. When no one bought stocks and the houses anymore, the banks simply had no money to lend out or give the customers who had deposited it. The customers lost, businesses were affected and the entire economy went down. Several measures to improve the situation have been differed on by the democrats and republicans, but either way implemented by the current government. As it stands the economic situation is at odds with historical conventional suppositions of recession and boom. The stock market still shakily fluctuates from the recent crushes it has faced. Consumer confidence is low although unemployment figures are beginning to skew positively. Retirement funds are jeopardized although the economy does not seem to be shrinking. The government is facing large budgetary deficits yet it must allocate huge amounts for both the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. A wish to lower income taxes by Americans is a welcome to stimulate the economy, but the overwhelming deficit should be reduced in order to have a healthier economy.

It is worth mentioning that, the government is currently run by the democrats and the republicans are in opposition. Also that, the current economic crisis started when the republicans were in the government and the democrats in opposition. Now, the two groups take different views on how the economic situation should be handled.

As outlined by the Republican National Committee (2008, Economic section, para. 2-15) in the party’s official website, the republicans take on the economy in a nutshell is to save every government penny available. It is on the basis of saving all you have to improve economically. They have discuss a number of measures to achieve this.

The republicans propose lowering of taxes paid by everyone so that people can keep more of the salary they earn. These include taxes on internet access and on new cell phones. They also propose scrapping off of the federal death tax while supporting tax credits on healthcare and medical expenses. In addition, republicans seek to do away with the Alternative Minimum Tax which is argued to be a burden on large families. All this is perceived by republicans to enhance individual savings improving their economy and the nation’s economy as a whole.

The republican do propose increase of small businesses through out the nation. This they hope to achieve by reducing the energy costs through better delivery structures and improved efficiency in the energy sector operations. The tax reduction aforementioned increases savings and hence availability of capital for starting the small businesses. They also propose increased marketing of American products to foreign markets enhancing growth of the small scale businesses. The republicans want improved regulation of small businesses. Instituting legal reforms that protect small businesses from frivolous law suits is another strategy of improving this.

Other ways the republicans suggest for improving the economy include: improving technology and innovation, developing a flexible and innovative workforce. This they view will keep America ahead and attract professional expertise. Protecting union workers and reforming the civil justice system is another of the ways enhancing economic performance.

The democrats’ view of solving the economic problem is to spend what they have in order to make the situation better now while embarking on the long term improvements. In the Democratic Party website by the Democratic National Committee (2010, Economic section, para. 1-14), they propose several measures under economic stewardship aimed at attaining a healthy U.S economy. The key component in this roadmap is the economic stimulus package. It is an effort by the government to inject money into the economy and encourage consumers to spend so that growth can be achieved.

As discussed in the New York Times (2010, Business section, para. 2-5), the $787 billion stimulus package approved by Congress on February 11, 2009 has so far been spent on several institutions in different sectors of the economy. No republican voted for the bill in the house and only three did in the Senate. The money bailed out: Lehman brothers and Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch and Freddie Mac, AIG, GM, Chevrolet and Ford Motors among other financial and industrial institutions. The reason behind the expenditure by democrats is that, the economic repercussions of such institutions failing are more severe. While by November of last year several people agreed that the stimulus package was working, unemployment rates continued to increase. A further $15 billion bill of payroll tax exemption was passed to help reduce this figure. This kind of spending by the democrats has gone on in different sectors of the U.S economy in an attempt to revive it.

Other areas through which the democrats hope to improve the economy include increasing tax on people with higher income but not those with low income. Investing in alternative energy that is cheap and environmentally friendly is another means of attaining this. The democrats propose reforms on health care that they believe will make it less costly. In so doing they ease the average citizens’ economic burden and thus improve their economic standard. The bill is still in the house. There are long term plans to lower the cost of college education to have a more skilled workforce. There are also plans of increasing international trade to benefit U.S firms and focusing on innovation and technology.

Both the democrats and the republicans focus on the same subjects in the quest for strategies of improving the economy. These include taxes, energy, spending strategies, international trade among others. In both cases the strategies would work each with its pros and cons and culminates into an improved economy. The current economic situation the United States is facing is a glimpse to the scarcity of resources it possesses like any other country and the fact that no decision occurs without a component cost. Politics therefore creates the differences on which way to take in improving the economy. Had the republicans or the independents been elected to power, the economy would have still improved as it is doing now.

Billington, Ray A. American History Before 1877 . Maryland: Littlefields, 1965. Print.

Berkin, Carol, et al. Making of America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995. Print.

Democratic National Committee. ‘’ Economy’’ American Dream. Aug. 2009. Web.

Hofstadter, Richard. The American Political Tradition: and the Men Who Made It. Canada: McClelland, 1948. Print.

Oates, Stephen, et al. Portrait of America. Connecticut: Wadsworth, 2007. Print.

Republican National Committee. ‘’ Economy’’. 2008 Republican Platform . Web.

The New York Times. ‘’ Economic Stimulus’’. Times Topics. 2010. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 9). The History of the American Economy: From Zero to One of the Largest Economies in the World. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-history-of-american-economy/

"The History of the American Economy: From Zero to One of the Largest Economies in the World." IvyPanda , 9 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-history-of-american-economy/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The History of the American Economy: From Zero to One of the Largest Economies in the World'. 9 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The History of the American Economy: From Zero to One of the Largest Economies in the World." December 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-history-of-american-economy/.

1. IvyPanda . "The History of the American Economy: From Zero to One of the Largest Economies in the World." December 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-history-of-american-economy/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The History of the American Economy: From Zero to One of the Largest Economies in the World." December 9, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-history-of-american-economy/.

- The Hamilton (Disney-Plus) Performance Critique

- The Vision of America: Hamilton v. Jefferson

- A. Hamilton as the Most Notable Person of His Time

- The Future of American Economy

- Development Strategies for Advanced Countries

- "Out of the Traps" Economist Article Analysis

- “Visiting Grandchildren: Economic Development in the Maritimes” by Savoie

- Business in Developing Countries: India

An official website of the United States government

U.S. Economy at a Glance

Perspective from the bea accounts.

BEA produces some of the most closely watched economic statistics that influence decisions of government officials, business people, and individuals. These statistics provide a comprehensive, up-to-date picture of the U.S. economy. The data on this page are drawn from featured BEA economic accounts.

National Economic Accounts

Gross domestic product, first quarter 2024 (advance estimate).

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 1.6 percent in the first quarter of 2024, according to the “advance” estimate. In the fourth quarter of 2023, real GDP increased 3.4 percent. The increase in the first quarter primarily reflected increases in consumer spending and housing investment that were partly offset by a decrease in inventory investment. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased.

- Current release: April 25, 2024

- Next release: May 30, 2024

Gross Domestic Product, First Quarter 2024 (Advance Estimate) CHART - HP

Personal Income and Outlays, March 2024

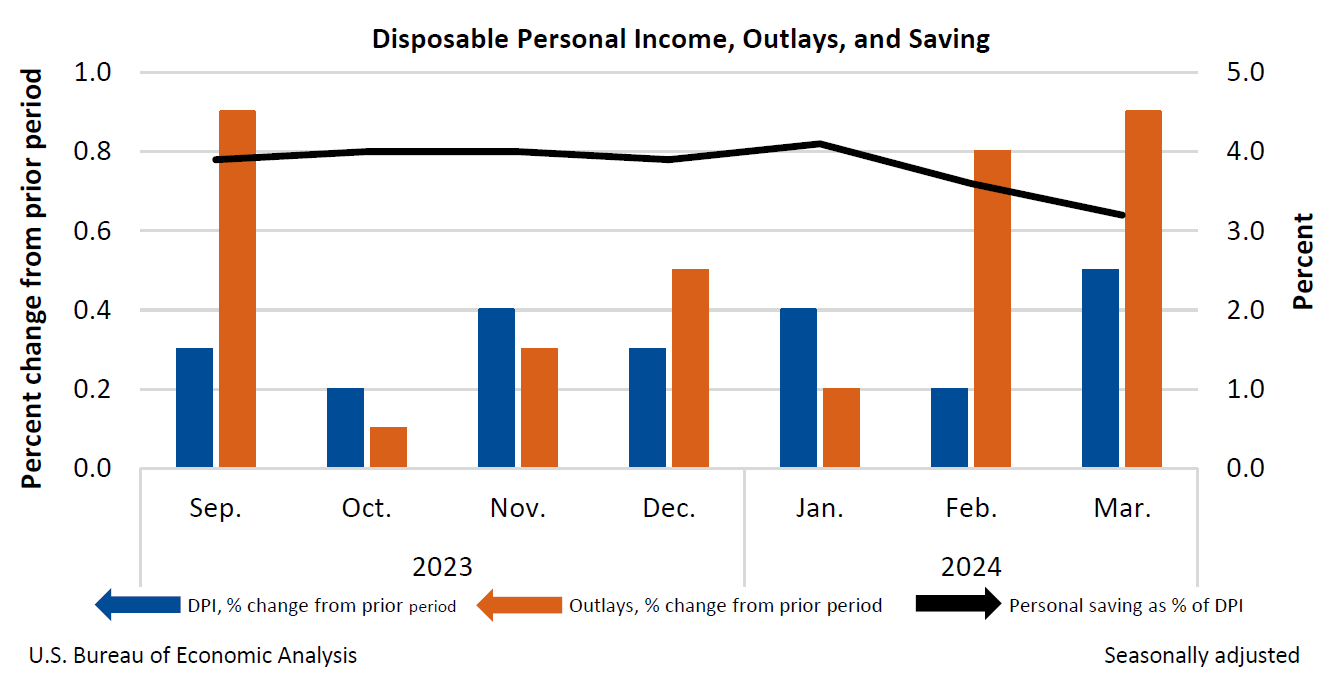

Personal income increased $122.0 billion (0.5 percent at a monthly rate) in March. Disposable personal income (DPI)—personal income less personal current taxes—increased $104.0 billion (0.5 percent). Personal outlays—the sum of personal consumption expenditures (PCE), personal interest payments, and personal current transfer payments—increased $172.1 billion (0.9 percent) and consumer spending increased $160.9 billion (0.8 percent). Personal saving was $671.0 billion and the personal saving rate—personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income—was 3.2 percent in March.

- Current release: April 26, 2024

- Next release: May 31, 2024

Personal Income and Outlays, March 2024 CHART

Industry Economic Accounts

International economic accounts, u.s. international transactions, 4th quarter and year 2023.

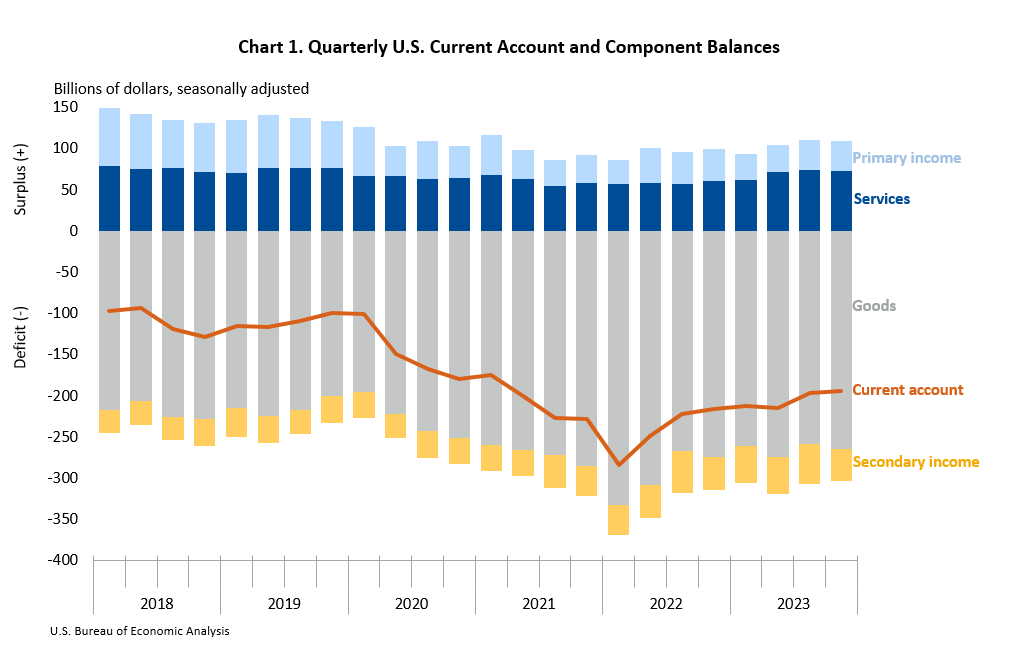

The U.S. current-account deficit narrowed by $1.6 billion, or 0.8 percent, to $194.8 billion in the fourth quarter of 2023, according to statistics released today by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The revised third-quarter deficit was $196.4 billion. The fourth-quarter deficit was 2.8 percent of current-dollar gross domestic product, down less than 0.1 percent from the third quarter.

- Current Release: March 21, 2024

- Next Release: June 20, 2024

U.S. International Transactions 4th Quarter, '23 Chart 1

U.S. International Investment Position, 4th Quarter and Year 2023

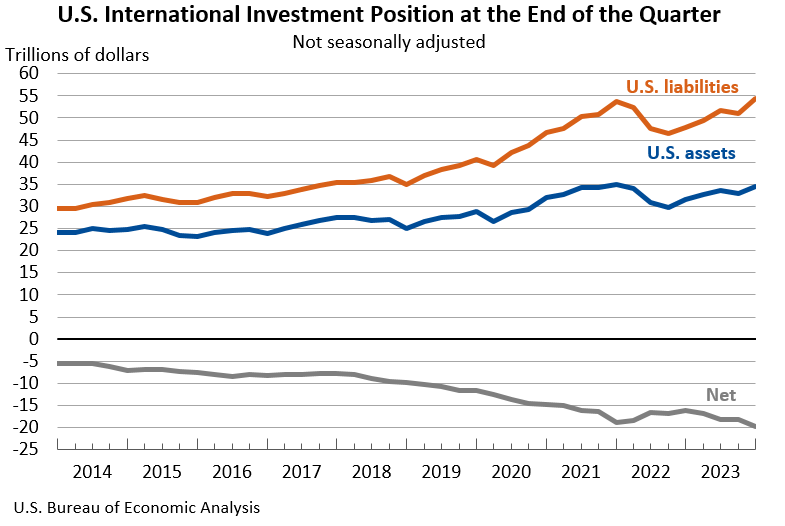

The U.S. net international investment position, the difference between U.S. residents’ foreign financial assets and liabilities, was -$19.77 trillion at the end of the fourth quarter of 2023, according to statistics released today by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Assets totaled $34.54 trillion, and liabilities were $54.31 trillion. At the end of the third quarter, the net investment position was -$18.11 trillion (revised).

- Current Release: March 27, 2024

- Next Release: June 26, 2024

U.S. International Investment Position, 4th Quarter and year '23 CHART

U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, March 2024

The U.S. goods and services trade deficit decreased in March 2024 according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and the U.S. Census Bureau. The deficit decreased from $69.5 billion in February (revised) to $69.4 billion in March, as imports decreased more than exports. The goods deficit increased $0.8 billion in March to $92.5 billion. The services surplus increased $0.9 billion in March to $23.1 billion.

- Current Release: May 2, 2024

- Next release: June 6, 2024

U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, March 2024 CHART

New Foreign Direct Investment in the United States, 2022

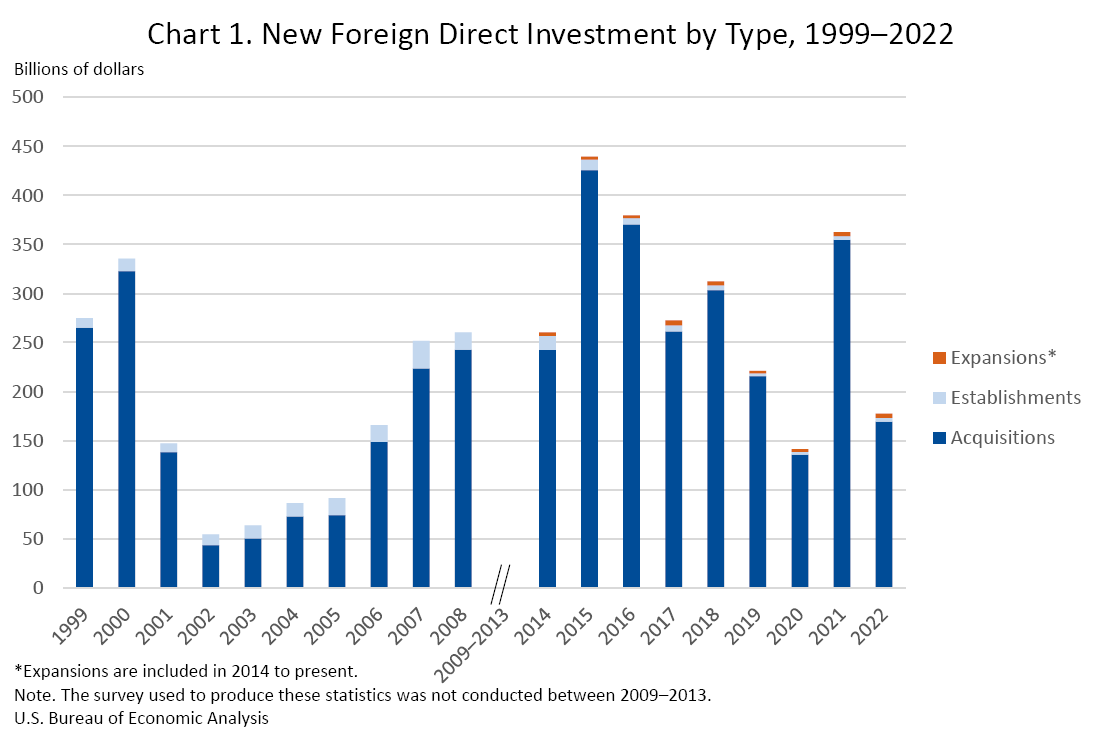

Expenditures by foreign direct investors to acquire, establish, or expand U.S. businesses totaled $177.5 billion in 2022, down $185.1 billion from $362.6 billion in 2021.

- Current release: July 10, 2023

- Next release: July 2024

New Foreign Direct Investment Expenditures by Type, '99-'22 Chart

Regional Economic Accounts

Gross domestic product by state and personal income by state, 4th quarter 2023 and preliminary 2023.

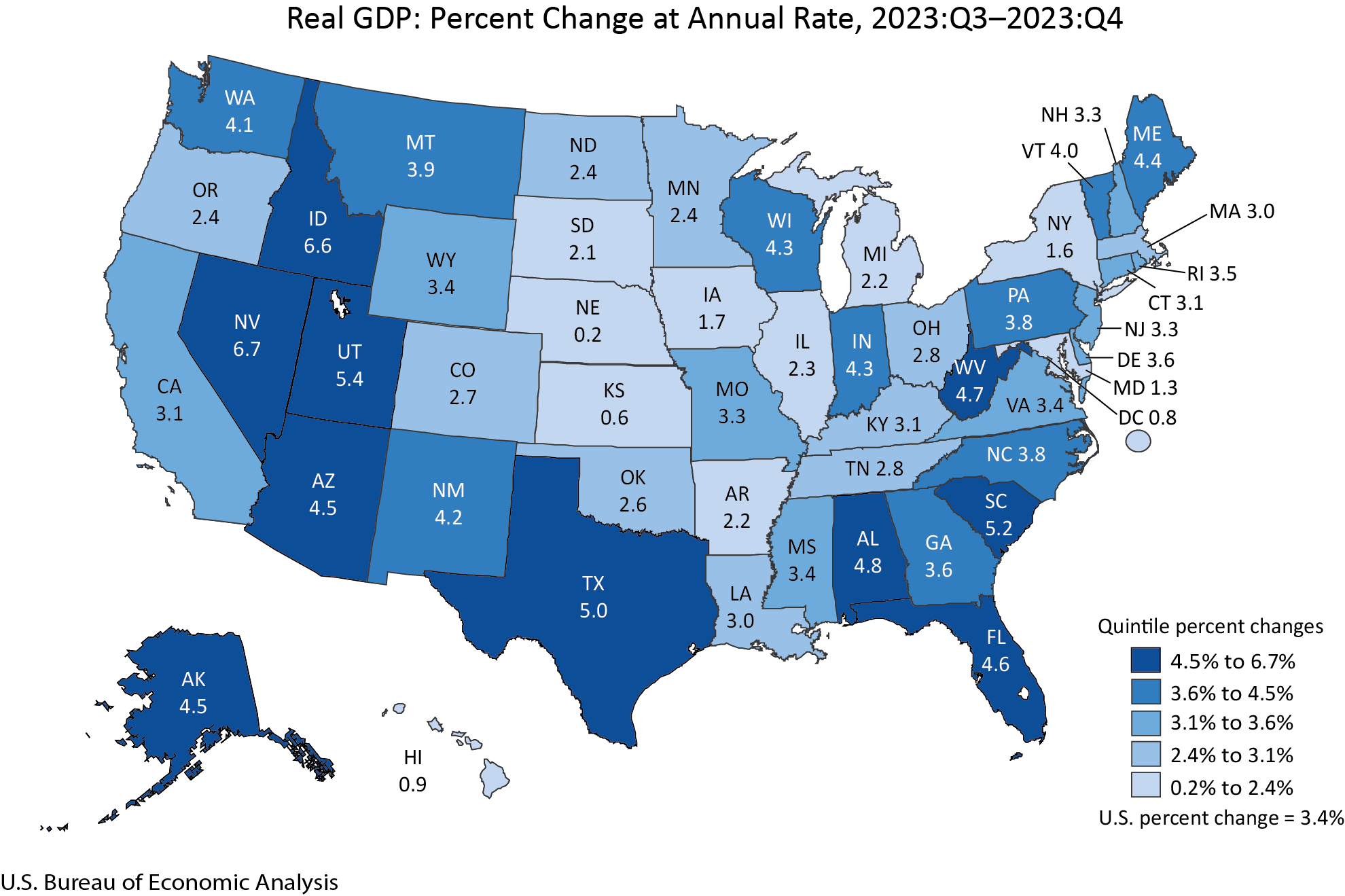

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased in all 50 states and the District of Columbia in the fourth quarter of 2023, with the percent change ranging from 6.7 percent in Nevada to 0.2 percent in Nebraska

- Current Release: March 29, 2024

- Next Release: June 28, 2024

Gross Domestic Product by State and Personal Income by State, 4th Quarter '23 and Preliminary '23 - CHART

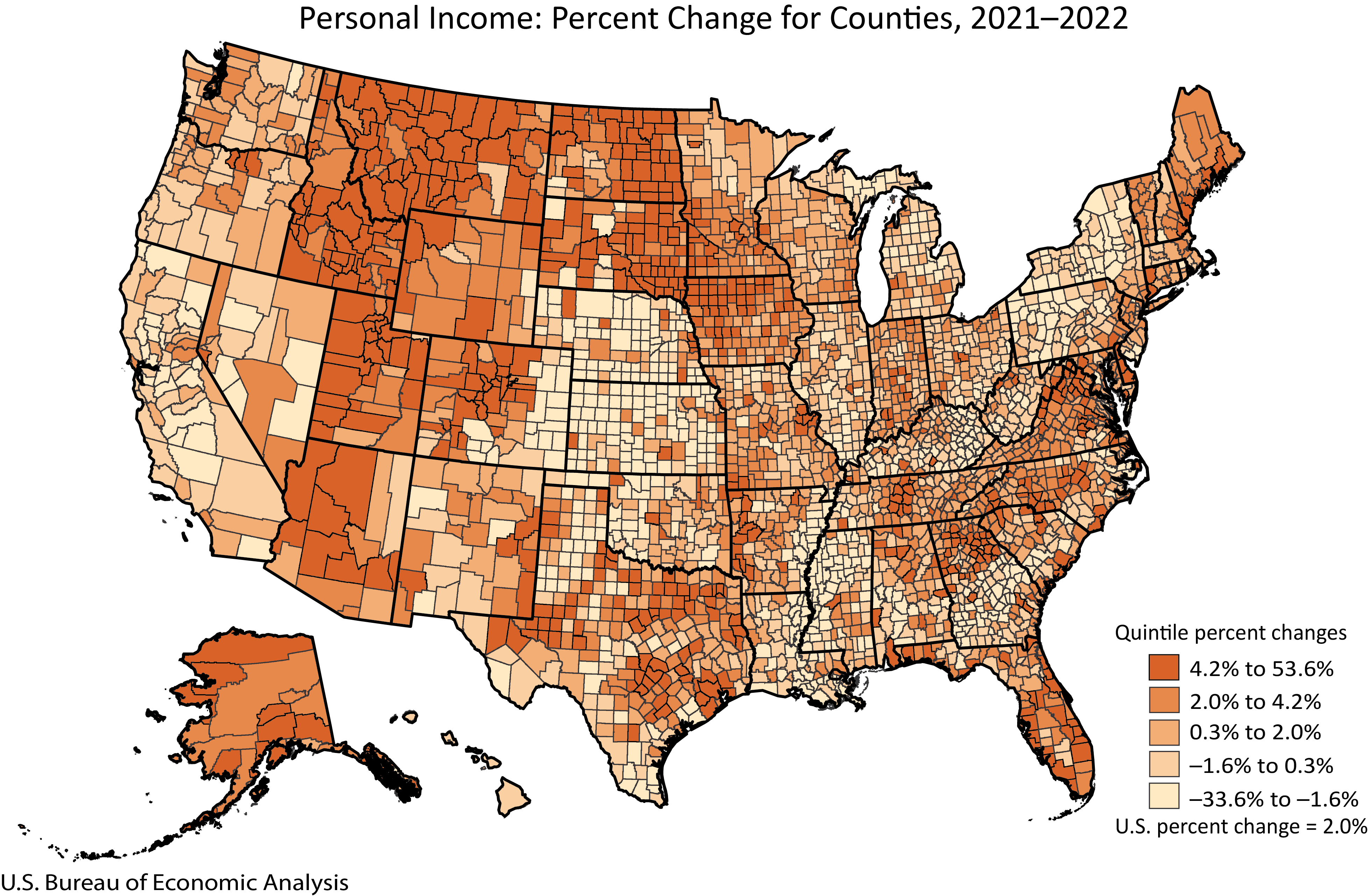

Personal Income by County and Metropolitan Area, 2022

In 2022, personal income, in current dollars, increased in 1,964 counties, decreased in 1,107, and was unchanged in 43. Personal income increased 2.1 percent in the metropolitan portion of the United States and 1.3 percent in the nonmetropolitan portion.

- Current Release: November 16, 2023

- Next Release: November 14, 2024

Personal Income by County and Metropolitan Area, 2022 CHART

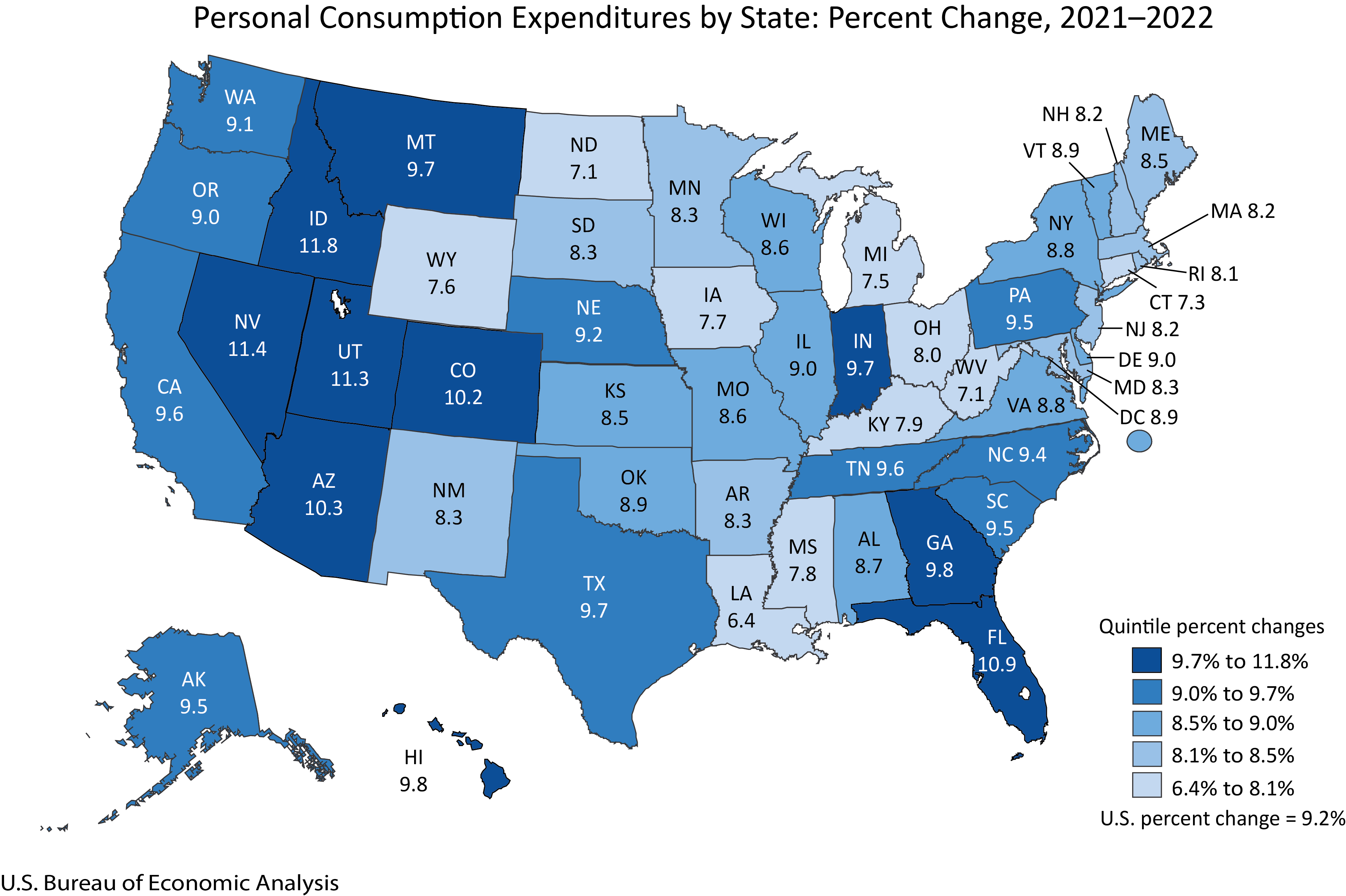

Personal Consumption Expenditures by State, 2022

Nationally, personal consumption expenditures (PCE), in current dollars, increased 9.2 percent in 2022 after increasing 12.9 percent in 2021. PCE increased in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, with the percent change ranging from 11.8 percent in Idaho to 6.4 percent in Louisiana.

- Current Release: October 4, 2023

- Next release: October 3, 2024

Personal Consumption Expenditures by State: Percent Change, '21-'22

136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Many Americans Believe the Economy Is Rigged

Guest essay in the new york times.

When asked what drives the economy, many Americans have a simple, single answer that comes to mind immediately: “greed.” They believe the rich and powerful have designed the economy to benefit themselves and have left others with too little or with nothing at all.

We know Americans feel this way because we asked them. Over the past two years, as part of a project with the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, we and a team of people conducted over 30 small-group conversations with Americans from almost every corner of the country. While national indicators may suggest that the economy is strong, the Americans we listened to are mostly not thriving. They do not see the economy as nourishing or supporting them. Instead, they tend to see it as an obstacle, a set of external forces out of their control that nonetheless seems to hold sway over their lives.

Take the perceived prevalence of greed. This is hardly a new feeling, but it has been exacerbated recently by inflation and higher housing costs. Americans experience these phenomena not as abstract concepts or political talking points but rather as grocery stores and landlords demanding more money.

Income inequality has been in decline over the last few years. But try explaining that to someone struggling to pay the rent. “I just feel like the underdog can’t get ahead, and it’s all about greed and profit,” one Kentucky participant noted. It is not necessarily the actual distribution of wealth that troubles people. It is the feeling that the economy is rigged against them. . . .

Commission on Reimagining Our Economy

The Commission seeks to reimagine the nation’s political economy, rethink the values that drive economic policy making, and advance recommendations that help individuals, communities, and the nation flourish.

Advancing a People-First Economy

New york times essay features academy work.

Why The American Economy Is Suddenly Exceptional

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Indie Studios LLC/getty images

The U.S. was known as the “cleanest dirty shirt” during the financial crisis, the one place you could safely put your money if you had to put it somewhere. Now it is being called exceptional.

A funny thing happened on the way to the U.S. recession of 2024: the irrepressible American economy refused to play along.

At the start of the year, investors around the world were looking for as many as six quarter-point interest rate cuts from the Federal Reserve to protect economic growth and fight inflation. But inflation has stayed stubbornly above the central bank’s 2% target and the economy keeps growing despite an overnight interest rate target range of 5.25-5.5%, the most among the Group of Seven industrial countries.

By early February those six rate cuts had become three , and on Wednesday, Fed Chair Jerome Powell gave the world the idea that there might not be any. In the circumspect language of a central banker, he said, “We do not expect that it will be appropriate to reduce the target range for the federal funds rate until we have gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2%. So far this year, the data have not given us that greater confidence.”

The central bank did throw the market a bone in the form of slowing sales of bonds from its own portfolio more sharply than had been expected, and Powell said he did not think inflation was so strong that the Fed is likely to want to raise rates. Treasury bond prices rose, a sign of relief that the interest-rate news was not worse, and stocks and the dollar held firm.

In the normal course of events, you could expect a tight monetary policy to curb economic growth and put a lid on stock gains. But Wall Street keeps rising and the dollar remains strong and investors keep financing Washington’s budget deficits. At the heart of this apparent conundrum is the idea that there is something special about the United States and its economy, an old idea that has been gaining popularity for more than a decade.

“The exceptional performance of the U.S. economy, both in absolute terms and relative to other countries, reflects the powerful combination of existing attributes and steps taken to invest in the engine of tomorrow’s growth,” says Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic advisor to the Munich-based insurer Allianz as well as president of Queens’ College at Cambridge University.

OPENING UP A LEAD

Five-year dollar-adjusted performances of major stock-market indexes in percent.

I n 2010, just off the depths of the Great Financial Crisis, El-Erian was co-chief executive officer of Pacific Investment Management, a subsidiary of Allianz. In a television interview that year he began referring to the U.S. as the “cleanest dirty shirt” among major economies, and the description was echoed by Bill Gross , his co-CIO at Pimco. At the time, America remained insulated from economic turmoil in Greece that was souring the outlook for its partners in the European Union, its financial markets benefiting from a flight to perceived quality.

People still use the phrase to compare the U.S. to its industrialized peers, but as the dollar and Wall Street have soared in recent months, it has been rebranded as American exceptionalism. That idea, which has been kicking around in politics since before the Revolution , is that the United States is unique among nations, based on factors that include its size, history, culture and geography. More recently, it is being used to explain world-leading results for U.S. stocks and the resilience of the American economy in the years since the financial crisis. The concept that America is more than a bolt-hole during times of stress is gaining notice. Consider these recent headlines:

American exceptionalism is real—in the stock market –Fortune, February 3

Why the US economy is doing so much better than the rest of the world –CNN, January 26

Tech-led U.S. 'exceptionalism' underlined –Reuters, February 15

Since the trough of the financial crisis, U.S. equities handily surpassed major rivals, rising at an annual rate of 16% over the 14 years through 2023, according to research from Goldman Sachs Goldman Sachs . By contrast, stocks in other developed countries were up 10% in that period, emerging markets 8% and China just 6%. Gains have slowed this year, but the Standard & Poor’s 500 index is up 5.2%, better in dollar terms than any other major broad-market gauge except Italy’s MIB, which has gained 7.9%. The U.S. advance came despite issues that include a snowballing budget deficit–it has grown by a daily average of $4.7 billion this year–a divided government, an immigration crisis and instances of social unrest. They raise the question of how much geographic diversity investors really need.

With the economy still expanding, the Fed can afford to concentrate on its fight against inflation. Consumer prices are rising at an annual rate of more than 3% and almost 4% when volatile food and energy prices are stripped out. The Fed’s favored inflation metric, based on personal consumption expenditures, is closer to the central bank’s 2% target—2.7% overall and 2.8% on a core basis—but the recent data can be misleading because the index surged by 16.6% from the end of 2019 through 2023.

Many investors seemed to have been looking past those sharp price hikes at the start of this year, when they believed U.S. central bankers would cut their overnight interest rate target to a range of 3.75-4%.

One clear advantage that the United States has is that its workers are more productive than those of any other major economy. At an estimated $85,373 of output per person, according to the International Monetary Fund , the U.S. is only surpassed by five countries: four offshore finance centers and oil-producing Norway. The next member of the Group of Seven industrialized nations on the list is Canada, at $54,866. Additionally, America has by far the largest economy (more than $28 trillion of annual gross domestic product) and stock and bond markets (worth about $90 trillion combined).