Attachment Styles and How They Affect Adult Relationships

Stephanie Huang

Project Manager

MED, Human Development and Psychology, Harvard University

Stephanie Huang holds a Master of Education degree from Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her academic interests mainly lie in the fields of developmental psychology, social-emotional learning, and informal education.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Attachment styles refer to patterns of bonding that people learn as children and carry into their adult relationships. They’re typically thought to originate from the type of care one received in their earliest years.

The concept involves one’s confidence in the attachment figure’s availability as a secure base from which one can freely explore the world when not in distress and a safe haven from which one can seek support, protection, and comfort in times of distress.

What are the attachment styles?

- Secure Attachment : Securely attached individuals are comfortable with intimacy and can balance dependence and independence in relationships.

- Preoccupied Attachment (Anxious in Children) : Individuals with this attachment style crave intimacy and can be overly dependent and demanding in relationships.

- Dismissive Attachment (Avoidant in Children) : This style is characterized by a strong sense of self-sufficiency, often to the point of appearing detached. Individuals with dismissive attachment value their independence highly and may seem uninterested in close relationships.

- Fearful Attachment (Disorganized in Children) : Individuals with a fearful attachment style desire close relationships and fear vulnerability. They may behave unpredictably in relationships due to their internal conflict between a desire for intimacy and fear of it.

In humans, the behavioral attachment system does not conclude in infancy or even childhood. Instead, it is active throughout the lifespan, with individuals gaining comfort from physical and mental representations of significant others (Bowlby, 1969).

There appears to be a continuity between early attachment styles and the quality of later adult romantic relationships.

This idea is based on the internal working model , where an infant’s primary attachment forms a model (template) for future relationships.

Attachment Styles

Attachment styles are expectations people develop about relationships with others, and the first attachment is based on the relationship individuals had with their primary caregiver when they were infants.

Attachment styles describe people’s comfort and confidence in close relationships, fear of rejection and yearning for intimacy, and preference for self-sufficiency or interpersonal distance.

Attachment styles comprise cognitions relating to both the self (‘Am I worthy of love’) and others (‘Can I depend on others during times of stress’).

Adult attachment styles derived from past relationship histories are conceptualized as internal working models .

Here, individuals can hold either a positive or negative belief of self and a positive or negative belief of others, thus resulting in one of four possible adult attachment styles.

The model of others can also be conceptualized as the avoidant dimension of attachment, which corresponds to the level of discomfort a person feels regarding psychological intimacy and dependency.

Alternatively, the model of self can be conceptualized as the anxiety dimension of attachment, relating to beliefs about self-worth and whether or not one will be accepted or rejected by others (Collins & Allard, 2001).

Bartholomew and Horowitz proposed four adult attachment styles regarding working models of self and others, including secure, dismissive, preoccupied, and fearful.

Secure Attachment Characteristics

Securely attached adults tend to hold positive self-images and positive images of others, meaning that they have both a sense of worthiness and an expectation that other people are generally accepting and responsive.

As Children

Secure attachment occurs because the mother meets the emotional needs of the infant.

Children with a secure attachment use their mother as a safe base to explore their environment. They are moderately distressed when their mother leaves the room (separation anxiety) and seek contact with their mother when she returns.

They also show moderate stranger anxiety; they show some distress when approached by a stranger.

Adults who demonstrate a secure attachment style value relationships and affirm the impact of relationships on their personalities.

They display a readiness to recall and discuss attachments that suggest much reflection regarding previous relationships.

Secure adults display openness regarding expressing emotions and thoughts with others and are comfortable with depending on others for help while also being comfortable with others depending on them (Cassidy, 1994).

Notably, many secure adults may, in fact, experience negative attachment-related events, yet they can objectively assess people and events and assign a positive value to relationships in general.

Secure lovers characterized their most important romantic relationships as happy and trusting. They can support their partners despite the partners’ faults.

Their relationships also tend to last longer. Secure lovers believe that although romantic feelings may wax and wane, romantic love will never fade.

Through the statistical analysis, secure lovers were found to have had warmer relationships with their parents during childhood.

Preoccupied Attachment Characteristics

Individuals with a preoccupied attachment (called anxious when referring to children) hold a negative self-image and a positive image of others, meaning that they have a sense of unworthiness but generally evaluate others positively.

As such, they strive for self-acceptance by attempting to gain approval and validation from their relationships with significant others. They also require higher levels of contact and intimacy in relationships with others.

Children with this type of attachment are clingy to their mother in a new situation and are not willing to explore – suggesting that they do not have trust in her.

They are extremely distressed when separated from their mother. When the mother returns, they are pleased to see her and go to her for comfort, but they cannot be comforted and may show signs of anger towards her.

This type of attachment style occurs because the mother sometimes meets the infant’s needs and sometimes ignores their emotional needs, i.e., the mother’s behavior is inconsistent.

Such individuals crave intimacy but remain anxious about whether other romantic partners will meet their emotional needs. Autonomy and independence can make them feel anxious.

Additionally, they are preoccupied with dependency on their own parents and still actively struggle to please them.

In addition, they can become distressed should they interpret recognition and value from others as being insincere or failing to meet an appropriate level of responsiveness.

Their attachment system is prone to hyperactivation during times of stress, emotions can become amplified, and overdependence on others is increased (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003).

Preoccupied lovers characterize their most important romantic relationships by obsession, desire for reciprocation and union, emotional highs and lows, and extreme sexual attraction and jealousy.

Preoccupied lovers often believe that it is easy for them to fall in love, yet they also claim that unfading love is difficult to find.

Compared with secure lovers, preoccupied lovers report colder relationships with their parents during childhood.

Anxious attachment is also known as insecure resistant or anxious ambivalent .

Dismissive Attachment Characteristics

Dismissive attachment style is demonstrated by adults with a positive self-image and a negative image of others. Their internal working model is based on an avoidant attachment established during infancy.

Children with an avoidant attachment do not use the mother as a safe base; they are not distressed on separation from their caregiver and are not joyful when the mother returns. They show little stranger anxiety.

This type of attachment occurs because the mother ignores the emotional needs of the infant.

They prefer to avoid close relationships and intimacy with others to maintain a sense of independence and invulnerability. This means they struggle with intimacy and value autonomy and self-reliance (Cassidy, 1994).

Dismissive-avoidant adults deny experiencing distress associated with relationships and downplay the importance of attachment in general, viewing other people as untrustworthy.

According to Dr. Julie Smith, a clinical psychologist, these are the signs of an avoidant attachment style in adult relationships:

- When your partner seeks intimacy with you, the barriers go up. The more they try to get close, the more you pull back.

- You hold back on starting new relationships because trusting people is so hard.

- You sometimes end relationships to gain a sense of freedom.

- You keep your partner at arm’s length emotionally because it feels safer, but they often accuse you of being distant.

Dismissive lovers are characterized by fear of intimacy, emotional highs and lows, and jealousy. They are often unsure of their feelings toward their romantic partner, believing that romantic love can rarely last and that it is hard for them to fall in love (Hazan & Shaver, 1987).

Proximity seeking is appraised as unlikely to alleviate distress resulting in deliberate deactivation of the attachment system, inhibition of the quest for support, and commitment to handling distress alone, especially distress arising from the failure of the attachment figure to be available and responsive (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003).

Dismissive individuals have learned to suppress their emotions at the behavioral level, although they still experience emotional arousal internally (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005).

This has negative outcomes in terms of cutting themselves off strong feelings, whether their own or others, thus influencing their experiences of romantic relationships.

Fearful Attachment Characteristics

Adults with a fearful-avoidant attachment style (also referred to as disorganized) hold a negative model of self and also a negative model of others, fearing both intimacy and autonomy.

They display attachment behaviors typical of avoidant children, becoming socially withdrawn and untrusting of others.

The behavior of a fearful-avoidant child is very disorganized, hence why it is also known as disorganized attachment.

If the child and caregiver were to be separated for any amount of time, on the reunion, the child would act conflicted. They may initially run towards their caregiver but then seem to change their mind and either run away or act out.

In the eyes of a child with a fearful avoidant attachment, their caregivers are untrustworthy.

Children with a fearful avoidant attachment are at risk of carrying these behaviors into adulthood if they do not receive support to overcome this. They may struggle to feel secure in any relationship if they do not get help for their attachment style.

“Like dismissing avoidant, they often cope with distancing themselves from relationship partners, but unlike dismissing individuals, they continue to experience anxiety and neediness concerning their partner’s love, reliability, and trustworthiness” (Schachner, Shaver & Mikulincer, 2003, p. 248).

A fearful avoidant prefers casual relationships and may stay in the dating stage of the relationship for a prolonged period as this feels more comfortable for them.

This is not always because they want to, but because they fear getting closer to someone.

A study found that those with a fearful avoidant attachment style are likely to have more sexual partners and higher sexual compliance than other attachment styles (Favez & Tissot, 2019).

They may prefer to have more sexual partners as a way to get physically close to someone without having to also be emotionally vulnerable to them – thus meeting their need for closeness.

They could also be more sexually compliant due to having poorer boundaries and learning in childhood that their boundaries do not matter . It is important to remember that this is not the case for all fearful avoidants.

A partner with this attachment style may prefer to keep their partner at a distance so that things do not get too emotionally intense.

They may be reluctant to share too much of themselves to protect themselves from eventual hurt. If the relationship gets too deep or they are asked to share personal stories, the fearful-avoidant may shut down rapidly.

It is common for those with a fearful attachment style to have grown up in a household that is very chaotic and toxic. As such, the fearful-avoidant may expect that their romantic relationships as adults should also be chaotic.

If they are in a relationship with someone secure and calm, they may be suspicious of why this is. They may believe something must be wrong and may challenge their partner or create a problem to make the relationship more unsettled but familiar to them.

They tend to always expect something bad to happen in their relationship and will likely find any reason to damage the relationship so they do not get hurt.

They may blame or accuse their partner of things they have not done, threaten to leave the relationship, or test their partner to see if this makes them jealous. All these strategies may cause their partner to consider ending the relationship.

Continuity Hypothesis

According to John Bowlby (1969), later relationships are likely to be a continuation of early attachment styles (secure and insecure) because the behavior of the infant’s primary attachment figure promotes an internal working model of relationships, which leads the infant to expect the same in later relationships.

In other words, there will be continuity between early attachment experiences and later relationships. This is known as the continuity hypothesis.

According to the continuity hypothesis, experiences with childhood attachment figures are retained over time and used to guide perceptions of the social world and future interactions with others.

The attachment styles we develop as children through interactions with primary caregivers often persist into adulthood and influence our expectations, emotions, and behaviors in romantic relationships. Specifically, secure, anxious, and avoidant attachment styles tend to be continuous from infancy into adulthood romantic attachments.

Romantic Relationships

Attachment theory , developed by Bowlby to explain emotional bonding between infants and caregivers, has implications for understanding romantic relationships.

There appears to be a continuity between early attachment styles and the quality of later adult romantic relationships. This idea is based on the internal working model, where an infant’s primary attachment forms a model (template) for future relationships.

The internal working model influences a person’s expectation of later relationships thus affects his attitudes towards them. In other words there will be continuity between early attachment experiences and later relationships.

Adult relationships are likely to reflect early attachment style because the experience a person has with their caregiver in childhood would lead to the expectation of the same experiences in later relationships.

This is illustrated in Hazan and Shaver’s love quiz experiment. They conducted a study to collect information on participants’ early attachment styles and attitudes toward loving relationships. They found that those securely attached as infants tended to have happy, lasting relationships.

On the other hand, insecurely attached people found adult relationships more difficult, tended to divorce, and believed love was rare. This supports the idea that childhood experiences have a significant impact on people’s attitudes toward later relationships.

The continuity hypothesis is accused of being reductionist because it assumes that people who are insecurely attached as infants would have poor-quality adult relationships. This is not always the case. Researchers found plenty of people having happy relationships despite having insecure attachments. Therefore, the theory might be an oversimplification.

Brennan and Shaver (1995) discovered that there was a strong association between one’s own attachment type and the romantic partner’s attachment type, suggesting that attachment style could impact one’s choice of partners.

To be more specific, the study found that a secure adult was most likely to be paired with another secure adult, while it was least likely for an avoidant adult to be paired with a secure adult; when a secure adult did not pair with a secure partner, he or she was more likely to have an anxious-preoccupied partner instead.

Moreover, whenever an avoidant or anxious adult did not pair with a secure partner, he or she was more likely to end up with an avoidant partner; an anxious adult was unlikely to be paired with another Anxious adult.

Adult attachment style also impacts how one behaves in romantic relationships (jealousy, trust, proximity-seeking, etc.) and how long these relationships can last, as discussed in earlier paragraphs about Hazan and Shaver’s (1987) findings.

These are, in turn, related to overall relationship satisfaction. Brennan and Shaver (1995) found that inclining toward a secure attachment type was positively correlated with one’s relationship satisfaction, whereas being either more avoidant or anxious was negatively associated with one’s relationship satisfaction.

Regarding attachment-related behaviors within relationships, being inclined to seek proximity and trust others was positively correlated with one’s relationship satisfaction.

Being self-reliant, ambivalent, jealous, clingy, easily frustrated towards one’s partner, or insecure is generally negatively correlated with one’s relationship satisfaction.

The attachment style and related behaviors of one’s partners were also found to impact one’s relationship satisfaction. Not surprisingly, having a Secure partner increases one’s relationship satisfaction.

However, an avoidant partner was the only type of partner that seemed to contribute negatively towards one’s relationship satisfaction, while an Anxious partner had no significant impact in this aspect.

The partner’s inclination to seek proximity and trust others increased one’s satisfaction, while one’s partner’s ambivalence and frustration towards oneself decreased one’s satisfaction.

Parenting Style

There is evidence that attachment styles may be transmitted between generations.

Research indicates an intergenerational continuity between adult attachment types and their children, including children adopting the parenting styles of their parents. People tend to base their parenting style on the internal working model, so the attachment type tends to be passed on through generations of a family.

Main, Kaplan, and Cassidy (1985) found a strong association between the security of the adults’ working model of attachment and that of their infants’, with a particularly strong correlation between mothers and infants (vs. fathers and infants).

Additionally, the same study also found that dismissive adults were often parents to avoidant infants. In contrast, preoccupied adults were often parents to resistant/ambivalent infants, suggesting that how adults conceptualized attachment relationships had a direct impact on how their infants attached to them.

An alternative explanation for continuity in relationships is the temperament hypothesis which argues that an infant’s temperament affects how a parent responds and so may be a determining factor in infant attachment type. The infant’s temperament may explain their issues (good or bad) with relationships in later life.

Mental Health

A new study published in the British Journal of Clinical Psychology sheds light on how our attachment styles affect our mental health and behaviors during difficult times like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Using advanced statistical techniques, researchers found that people with insecure attachment styles (especially anxious and fearful-avoidant attachments) suffered more depression, anxiety, and loneliness than their securely attached peers.

The researchers surveyed over 1300 UK adults at two time points between April and August 2020 to understand connections between attachment styles, adherence to social distancing guidelines, and mental health. They used cutting-edge causal modeling methods to estimate the likely causal effects.

The results showed that anxious and fearful-avoidant participants had around 5-6% higher depression and anxiety, and were 17-18% lonelier than secure individuals.

Over time, they maintained these elevated mental health symptoms while secure participants’ levels decreased. Greater loneliness explains the poorer mental health of insecure groups.

Avoidant participants were less likely to follow social distancing rules than secure individuals, although the effect size was small. Attachment style did not predict mental health changes from timepoints 1 to 2.

The takeaway?

Our attachment style is a risk factor for worse mental health crises during difficult collective experiences like lockdowns. Insecure individuals are more prone to loneliness driving their anxiety and depression.

The study highlights the need for targeted interventions to alleviate loneliness and promote security.

A limitation is the use of categorical attachment measures, but the advanced statistics provide compelling evidence attachment causally influences our mental health and behaviors during COVID-19 .

Internal Working Models

- The social and emotional responses of the primary caregiver (usually a parent) provide the infant with information about the world and other people and how they view themselves as individuals.

- For example, the extent to which an individual perceives himself/herself as worthy of love and care and information regarding the availability and reliability of others.

- John Bowlby (1969) referred to this knowledge as an internal working model , which begins as a mental and emotional representation of the infant’s first attachment relationship and forms the basis of an individual’s attachment style.

- The attachment continuity hypothesis states that the attachment style formed in infancy between child and caregiver remains relatively stable over time and continues to influence attachment behaviors in future close relationships.

- Romantic relationships are likely to reflect early attachment style because the experience a person has with their caregiver in childhood would lead to the expectation of the same experiences in later relationships, such as parents, friends, and romantic partners (Bartholomew and Horowitz, 1991).

- However, there is evidence that attachment styles are fluid and demonstrate fluctuations across the lifespan (Waters, Weinfield, & Hamilton, 2000).

- Other researchers have proposed that rather than a single internal working model, which is generalized across relationships, each type of relationship comprises a different working model. This means a person could be securely attached to their parents but insecurely attached in romantic relationships.

Researchers have proposed that working models are interconnected within a complex hierarchical structure (Collins & Read, 1994).

For example, the highest-level model comprises beliefs and expectations across all types of relationships, and lower-level models hold general rules about specific relations, such as romantic or parental, underpinned by models specific to events within a relationship with a single person.

How Attachment Style Is Measured

Children: ainsworth’s strange situation.

Ainsworth proposed the ‘sensitivity hypothesis,’ which states that the more responsive the mother is to the infant during their early months, the more secure their attachment will be.

To test this, she designed the ‘Strange Situation’ to observe attachment security in children within the context of caregiver relationships.

The child and mother experience a range of scenarios in an unfamiliar room. The procedure involves a series of eight episodes lasting approximately 3 minutes each, whereby a mother, child, and stranger are introduced, separated, and reunited.

Mary Ainsworth classified infants into one of three attachment styles; insecure avoidant (‘A’), secure (‘B’), or insecure ambivalent (‘C’).

A fourth attachment style, disorganized , was later identified (Main & Solomon, 1990).

Each type of attachment style comprises a set of attachment behavioral strategies used to achieve proximity with the caregiver and a feeling of security.

From an evolutionary perspective, an infant’s attachment classification (A, B, or C) is an adaptive response to the characteristics of the caregiving environment.

Ainsworth’s maternal sensitivity hypothesis argues that a child’s attachment style depends on their mother’s behavior towards them.

- ‘Sensitive’ mothers are responsive to the child’s needs and respond to their moods and feelings correctly. Sensitive mothers are more likely to have securely attached children.

- In contrast, mothers who are less sensitive towards their child, for example, those who respond to the child’s needs incorrectly or who are impatient or ignore the child, are likely to have insecurely attached children.

Adult Attachment Interview

Mary Main and her colleagues developed the Adult Attachment Interview that asked for descriptions of early attachment-related events and for the adults’ sense of how these relationships and events had affected adult personalities (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1984).

It is noteworthy that the Adult Attachment Interview assessed “the security of the self in relation to attachment in its generality rather than in relation to any particular present or past relationship” (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985).

For example, the general state of mind regarding attachment rather than how one is attached to another specific individual.

Main, Kaplan, and Cassidy (1985) analyzed adults’ responses to the Adult Attachment Interview and observed three major patterns in the way adults recounted and interpreted childhood attachment experiences and relationships in general:

- Secure (Autonomous)

- Dismissive-Avoidant Attachment

- Preoccupied (Anxious) Attachment

Can Your Attachment Style Change?

In the world of attachment studies, a big question is whether our ideas about relationships are kind of like a one-size-fits-all thing, working the same way across all relationships, or if they’re specific to particular relationships. Some experts, like Kobak (1994), have explored this.

So, one way to look at it is as an “individual difference.” This means that our attachment styles, our inner guides for how we connect with people, stay pretty much the same over time.

These styles are based on our experiences with people we’re close to, like parents, friends, and romantic partners. Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) think that how we act in relationships tends to be consistent, no matter who we’re with.

On the flip side, some folks believe that our attachment styles can change depending on the type of relationship. So, instead of one all-encompassing inner model for relationships, we might have different models for different types of connections. This means that you could be feeling secure with your parents but insecure in your romantic relationships.

A study with young adults showed that people have different attachment styles for various types of relationships, like with parents, friends, and romantic partners (Caron et al., 2012).

Researchers have suggested that these inner models are like a set of Russian dolls, with a big one that covers all types of relationships and smaller ones for specific types, like romance or family. These smaller ones are built on even smaller models, like beliefs about things that happen within one relationship.

There’s evidence supporting the idea that we have multiple internal working models because people can have a lot of different thoughts and feelings about themselves and others. And, while these specific relationship models are related to our overall generalized inner models, the connection isn’t super strong.

It means that our beliefs about ourselves and our partners in one type of relationship are somewhat separate from our broader views (Cozzarelli, Hoekstra, & Bylsma, 2000).

So, in a nutshell, our general ideas about relationships cover a wide range, while our specific thoughts about certain relationships are just a piece of the bigger picture.

Additionally, it is also noteworthy that one’s attachment style may alter over time as well.

Another interesting thing is that your attachment style can change over time . In different studies, about 70% of people had relatively stable attachment styles, while the other 30% were more flexible.

Baldwin and Fehr (1995) discovered that 30% of adults changed their attachment styles fairly quickly, sometimes in as little as a week or a few months. People who initially identified as anxious-ambivalent were the most likely to change.

In a 20-year longitudinal study , Waters et al. (2000) conducted the Adult Attachment Interview with young adults who had participated in the Strange Situation experiment 20 years ago. They found that 72% of the participants received the same secure vs. insecure attachment classification s as they did during infancy.

The remaining participants did change in terms of attachment patterns, with the majority – though not all – of them having experienced major negative life events.

Such findings suggest that attachment style assessments should be interpreted more prudently; furthermore, there is always the possibility for change – and it need not be related to negative events, either.

Bowlby’s (1969) theory holds that internal working models can become more resistant to change over time in a stable environment, but change is still possible over development. Attachment security and insecurity can be seen as diverging pathways – the further one progresses down one path, the harder it is to switch to the other.

Further Information

- How To Know If Your Date Has A Secure Attachment Style

- How To Move From Anxious Attachment To Secure

- BPS Article- Overrated: The predictive power of attachment

- Scoring for the Strange Situation

- A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship

- Cross-cultural Patterns of Attachment: A Meta-Analysis of the Strange Situation

- How Attachment Style Changes Through Multiple Decades Of Life

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . Lawrence Erlbaum.

Baldwin, M.W., & Fehr, B. (1995). On the instability of attachment style ratings. Personal Relationships, 2, 247-261.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L.M. (1991). Attachment Styles Among Young Adults: A Test of a Four-Category Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 (2), 226–244.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume I. Attachment . London: Hogarth Press.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (p. 46–76). The Guilford Press.

Brennan, K. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1995). Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 (3), 267–283.

Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (1999). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications . Rough Guides.

Caron, A., Lafontaine, M., Bureau, J., Levesque, C., and Johnson, S.M. (2012). Comparisons of Close Relationships: An Evaluation of Relationship Quality and Patterns of Attachment to Parents, Friends, and Romantic Partners in Young Adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 44 (4), 245-256.

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1994). Cognitive representations of adult attachment: The structure and function of working models. In K. Bartholomew & D. Perlman (Eds.) Advances in personal relationships, Vol. 5: Attachment processes in adulthood (pp. 53-90). London: Jessica Kingsley.

George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1984). The Adult Attachment Interview. Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley.

Harlow, H. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13 , 573-685.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511–524.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50 (1-2), 66-104.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy . Ablex Publishing.

Vowels, L. M., Vowels, M. J., Carnelley, K. B., Millings, A., & Gibson‐Miller, J. (2023). Toward a causal link between attachment styles and mental health during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Clinical Psychology .

Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 71 (3), 684-689.

Waters, E., Weinfield, N. S., & Hamilton, C. E. (2000). The stability of attachment security from infancy to adolescence and early adulthood: General discussion. Child Development, 71 (3), 703-706.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Attachment Theory?

The Importance of Early Emotional Bonds

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

- Attachment Theory

- Stages of Attachment

Attachment Styles

Attachment theory focuses on relationships and bonds (particularly long-term) between people, including those between a parent and child and between romantic partners. It is a psychological explanation for the emotional bonds and relationships between people.

This theory suggests that people are born with a need to forge bonds with caregivers as children. These early bonds may continue to have an influence on attachments throughout life.

History of the Attachment Theory

British psychologist John Bowlby was the first attachment theorist. He described attachment as a "lasting psychological connectedness between human beings." Bowlby was interested in understanding the anxiety and distress that children experience when separated from their primary caregivers.

Thinkers like Freud suggested that infants become attached to the source of pleasure. Infants, who are in the oral stage of development, become attached to their mothers because she fulfills their oral needs.

Some of the earliest behavioral theories suggested that attachment was simply a learned behavior. These theories proposed that attachment was merely the result of the feeding relationship between the child and the caregiver. Because the caregiver feeds the child and provides nourishment, the child becomes attached.

Bowlby observed that feedings did not diminish separation anxiety. Instead, he found that attachment was characterized by clear behavioral and motivation patterns. When children are frightened, they seek proximity from their primary caregiver in order to receive both comfort and care.

Understanding Attachment

Attachment is an emotional bond with another person. Bowlby believed that the earliest bonds formed by children with their caregivers have a tremendous impact that continues throughout life. He suggested that attachment also serves to keep the infant close to the mother, thus improving the child's chances of survival.

Bowlby viewed attachment as a product of evolutionary processes. While the behavioral theories of attachment suggested that attachment was a learned process, Bowlby and others proposed that children are born with an innate drive to form attachments with caregivers.

Throughout history, children who maintained proximity to an attachment figure were more likely to receive comfort and protection, and therefore more likely to survive to adulthood. Through the process of natural selection, a motivational system designed to regulate attachment emerged.

The central theme of attachment theory is that primary caregivers who are available and responsive to an infant's needs allow the child to develop a sense of security. The infant learns that the caregiver is dependable, which creates a secure base for the child to then explore the world.

So what determines successful attachment? Behaviorists suggest that it was food that led to forming this attachment behavior, but Bowlby and others demonstrated that nurturance and responsiveness were the primary determinants of attachment.

Ainsworth's "Strange Situation"

In her research in the 1970s, psychologist Mary Ainsworth expanded greatly upon Bowlby's original work. Her groundbreaking "strange situation" study revealed the profound effects of attachment on behavior. In the study, researchers observed children between the ages of 12 and 18 months as they responded to a situation in which they were briefly left alone and then reunited with their mothers.

Based on the responses the researchers observed, Ainsworth described three major styles of attachment: secure attachment, ambivalent-insecure attachment, and avoidant-insecure attachment. Later, researchers Main and Solomon (1986) added a fourth attachment style called disorganized-insecure attachment based on their own research.

A number of studies since that time have supported Ainsworth's attachment styles and have indicated that attachment styles also have an impact on behaviors later in life.

Maternal Deprivation Studies

Harry Harlow's infamous studies on maternal deprivation and social isolation during the 1950s and 1960s also explored early bonds. In a series of experiments, Harlow demonstrated how such bonds emerge and the powerful impact they have on behavior and functioning.

In one version of his experiment, newborn rhesus monkeys were separated from their birth mothers and reared by surrogate mothers. The infant monkeys were placed in cages with two wire-monkey mothers. One of the wire monkeys held a bottle from which the infant monkey could obtain nourishment, while the other wire monkey was covered with a soft terry cloth.

While the infant monkeys would go to the wire mother to obtain food, they spent most of their days with the soft cloth mother. When frightened, the baby monkeys would turn to their cloth-covered mother for comfort and security.

Harlow's work also demonstrated that early attachments were the result of receiving comfort and care from a caregiver rather than simply the result of being fed.

The Stages of Attachment

Researchers Rudolph Schaffer and Peggy Emerson analyzed the number of attachment relationships that infants form in a longitudinal study with 60 infants. The infants were observed every four weeks during the first year of life, and then once again at 18 months.

Based on their observations, Schaffer and Emerson outlined four distinct phases of attachment, including:

Pre-Attachment Stage

From birth to 3 months, infants do not show any particular attachment to a specific caregiver. The infant's signals, such as crying and fussing, naturally attract the attention of the caregiver and the baby's positive responses encourage the caregiver to remain close.

Indiscriminate Attachment

Between 6 weeks of age to 7 months, infants begin to show preferences for primary and secondary caregivers. Infants develop trust that the caregiver will respond to their needs. While they still accept care from others, infants start distinguishing between familiar and unfamiliar people, responding more positively to the primary caregiver.

Discriminate Attachment

At this point, from about 7 to 11 months of age, infants show a strong attachment and preference for one specific individual. They will protest when separated from the primary attachment figure (separation anxiety), and begin to display anxiety around strangers (stranger anxiety).

Multiple Attachments

After approximately 9 months of age, children begin to form strong emotional bonds with other caregivers beyond the primary attachment figure. This often includes a second parent, older siblings, and grandparents.

Factors That Influence Attachment

While this process may seem straightforward, there are some factors that can influence how and when attachments develop, including:

- Opportunity for attachment : Children who do not have a primary care figure, such as those raised in orphanages, may fail to develop the sense of trust needed to form an attachment.

- Quality caregiving : When caregivers respond quickly and consistently, children learn that they can depend on the people who are responsible for their care, which is the essential foundation for attachment. This is a vital factor.

There are four patterns of attachment, including:

- Ambivalent attachment : These children become very distressed when a parent leaves. Ambivalent attachment style is considered uncommon, affecting an estimated 7% to 15% of U.S. children. As a result of poor parental availability, these children cannot depend on their primary caregiver to be there when they need them.

- Avoidant attachment : Children with an avoidant attachment tend to avoid parents or caregivers, showing no preference between a caregiver and a complete stranger. This attachment style might be a result of abusive or neglectful caregivers. Children who are punished for relying on a caregiver will learn to avoid seeking help in the future.

- Disorganized attachment : These children display a confusing mix of behavior, seeming disoriented, dazed, or confused. They may avoid or resist the parent. Lack of a clear attachment pattern is likely linked to inconsistent caregiver behavior. In such cases, parents may serve as both a source of comfort and fear, leading to disorganized behavior.

- Secure attachment : Children who can depend on their caregivers show distress when separated and joy when reunited. Although the child may be upset, they feel assured that the caregiver will return. When frightened, securely attached children are comfortable seeking reassurance from caregivers. This is the most common attachment style.

The Lasting Impact of Early Attachment

Children who are securely attached as infants tend to develop stronger self-esteem and better self-reliance as they grow older. These children also tend to be more independent, perform better in school, have successful social relationships, and experience less depression and anxiety.

Research suggests that failure to form secure attachments early in life can have a negative impact on behavior in later childhood and throughout life.

Children diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) frequently display attachment problems, possibly due to early abuse, neglect, or trauma. Children adopted after the age of 6 months may have a higher risk of attachment problems.

Attachment Disorders

In some cases, children may also develop attachment disorders. There are two attachment disorders that may occur: reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED).

- Reactive attachment disorder occurs when children do not form healthy bonds with caregivers. This is often the result of early childhood neglect or abuse and results in problems with emotional management and patterns of withdrawal from caregivers.

- Disinhibited social engagement disorder affects a child's ability to form bonds with others and often results from trauma, abandonment, abuse, or neglect. It is characterized by a lack of inhibition around strangers, often leading to excessively familiar behaviors around people they don't know and a lack of social boundaries.

Adult Attachments

Although attachment styles displayed in adulthood are not necessarily the same as those seen in infancy, early attachments can have a serious impact on later relationships. Adults who were securely attached in childhood tend to have good self-esteem, strong romantic relationships, and the ability to self-disclose to others.

A Word From Verywell

Our understanding of attachment theory is heavily influenced by the early work of researchers such as John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Today, researchers recognize that the early relationships children have with their caregivers play a critical role in healthy development.

Such bonds can also have an influence on romantic relationships in adulthood. Understanding your attachment style may help you look for ways to become more secure in your relationships.

Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss . Basic Books.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect . Am J Orthopsychiatry . 1982;52(4):664-678. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

Draper P, Belsky J. Personality development in the evolutionary perspective . J Pers. 1990;58(1):141-61. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00911.x

Ainsworth MD, Bell SM. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation . Child Dev . 1970;41(1):49-67. doi:10.2307/1127388

Main M, Solomon J. Discovery of a new, insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In: Brazelton TB, Yogman M, eds., Affective Development in Infancy. Ablex.

Harlow HF. The nature of love . American Psychologist. 1958;13(12):673-685. doi:10.1037/h0047884

Schaffer HR, Emerson PE. The development of social attachments in infancy . Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1964;29:1-77. doi:10.2307/1165727

Lyons-Ruth K. Attachment relationships among children with aggressive behavior problems: The role of disorganized early attachment patterns . J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):64-73. doi:https:10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.64

Young ES, Simpson JA, Griskevicius V, Huelsnitz CO, Fleck C. Childhood attachment and adult personality: A life history perspective . Self and Identity . 2019;18:1:22-38. doi:10.1080/15298868.2017.1353540

Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation . Erlbaum.

Ainsworth MDS. Attachments and other affectional bonds across the life cycle. In: Attachment Across the Life Cycle . Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P, eds. Routledge.

Bowlby J. The nature of the child's tie to his mother . Int J Psychoanal . 1958;39:350-371.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Attachment Theory and Emotion Experience in Life Essay

Introduction, the attachment theory and life experiences, works cited.

This paper reports on the attachment theory and how life experience affects one’s emotional attachment to others. Attachment theory advanced by John Bowlby in the early 1950s, seeks to explain how early life relations affects an individual’s emotional bonding in future Hutchison (89).

The theory gives an understanding of the different personalities as relates to emotional relationships. The theory was first focused on the relationship between children and their parents, but was later expanded to look at the whole lifespan. The theory looks at ones attachment as being influenced by both psychological conditions and the social environment.

According to the proponents of the attachment theory, children develop a bond with their caregivers, which grow into an emotional bond. Further research on the theory indicates that life experiences in childhood direct the course of one’s personality as well as the social and emotional development throughout his or her life.

Besides the explanation advanced by the theory regarding the connection between a baby and its mother or a care giver, the theory also seeks to explain the attachment between adults Hutchison (43). Among adults, an emotional attachment is felt more especially during bereavement or separation of spouses. Babies are born without the ability to move or feed themselves.

They depend on care givers to for these needs; they however have pre-programmed set of behavior that comes into action due to the environmental stimuli. Environmental stimuli may trigger a sense of fear or distress in the baby making it cry for help from the mother or the care giver. The protection or comfort offered to the baby makes it develop a stronger emotional bond with the mother and others who are closer to it.

Children grow to relate comfort from distress to the people who are close to them during their early stages of development. The nature of the environment a child grows in, together with the “psychological framework builds up a child’s internal working model” Hutchison (52).

The internal working model comprises of the development of expectations that an individual perceives in social interactions. The theory explains the effect of challenging parenting such as; neglect or abuse. Parents and caregivers should endeavor to develop an environment that makes children feel secure and comfortable.

The type of relationship parents establish with their children at their early stages of development determines the type of emotional attachment a child develops with them. A child who grows up in a loving and sensitive environment develops secure relationships in with others.

Such a child grows to recognize others as being caring, loving and reliable. They also develop high self esteem and learn to deal with negative feelings. Research indicates that people who grow up in secure attachment relationships are able to demonstrate good social aptitude throughout their life.

On the contrary, children brought up in unsecure environment develop an avoidant attachment. An unsecure environment to children is often characterized by fear, anxiety and rejection. This type of environment makes a child make children to downplay their emotional feelings.

There is a group of children who grow up with care givers that are not consistent in responding to their emotional needs. Their care givers are sometimes sensitive, and sometimes insensitive to their feelings. Such children develop “an attachment seeking habit as they try to conquer the insensitivity of their caregivers” Hutchison (34).

This sort of behavior by children is referred to as ambivalent attachment, where the children seek to compensate for the inconsistent responsiveness by the caregiver. Such a child tries to manage other people’s attention through behavior sets such as; seduction, bullying rage and necessity.

Hutchison, Elizabeth . Dimensions of human behavior: The changing life course. 4th Ed . Thousand oaks, CA: Sage publications, 2011. Print

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 24). Attachment Theory and Emotion Experience in Life. https://ivypanda.com/essays/attachment-theory/

"Attachment Theory and Emotion Experience in Life." IvyPanda , 24 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/attachment-theory/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Attachment Theory and Emotion Experience in Life'. 24 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Attachment Theory and Emotion Experience in Life." November 24, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/attachment-theory/.

1. IvyPanda . "Attachment Theory and Emotion Experience in Life." November 24, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/attachment-theory/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Attachment Theory and Emotion Experience in Life." November 24, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/attachment-theory/.

- Is There a Particular Attachment Style Linked With Conduct Disordered Children

- Political Parties: Texas Politics and Local Government

- The Impact of Mobile Devices on Cybersecurity

- Literacy Through iPads in Early Education

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Formative Years and Education

- Dimensions of Human Behavior

- Three Mobile Company Review

- American Revolution in Historical Misrepresentation

- Telstra Corporation: Situation Analysis

- The Lottery Literary Analysis – Summary & Analytical Essay

- Development Theories in Child Development

- The Theory of Human Change and Growth

- Compare and Contrast Child Developmental Theories

- Self Efficacy, Stress & Coping, and Headspace Program

- Definition and Theories of Environmental Psychology

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Attachment style predicts affect, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning in daily life.

- 1 Departament de Psicologia Clínica i de la Salut, Facultat de Psicologia, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 2 Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, USA

- 3 Sant Pere Claver – Fundació Sanitària, Barcelona, Spain

- 4 Centre for Biomedical Research Network on Mental Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain

- 5 Red de Excelencia PROMOSAM (PSI2014-56303-REDT), MINECO, Spain

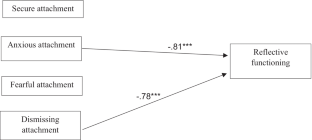

The way in which attachment styles are expressed in the moment as individuals navigate their real-life settings has remained an area largely untapped by attachment research. The present study examined how adult attachment styles are expressed in daily life using experience sampling methodology (ESM) in a sample of 206 Spanish young adults. Participants were administered the Attachment Style Interview (ASI) and received personal digital assistants that signaled them randomly eight times per day for 1 week to complete questionnaires about their current experiences and social context. As hypothesized, participants’ momentary affective states, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning varied in meaningful ways as a function of their attachment style. Individuals with an anxious attachment, as compared with securely attached individuals, endorsed experiences that were congruent with hyperactivating tendencies, such as higher negative affect, stress, and perceived social rejection. By contrast, individuals with an avoidant attachment, relative to individuals with a secure attachment, endorsed experiences that were consistent with deactivating tendencies, such as decreased positive states and a decreased desire to be with others when alone. Furthermore, the expression of attachment styles in social contexts was shown to be dependent upon the subjective appraisal of the closeness of social contacts, and not merely upon the presence of social interactions. The findings support the ecological validity of the ASI and the person-by-situation character of attachment theory. Moreover, they highlight the utility of ESM for investigating how the predictions derived from attachment theory play out in the natural flow of real life.

Introduction

Attachment theory ( Bowlby, 1973 , 1980 , 1982 ), along with its theoretical and empirical extensions (e.g., Main, 1990 ; Schore, 1994 ; Mikulincer and Shaver, 2003 ), is a useful and influential framework for understanding personality development, relational processes, and the regulation of affect. Over the past two decades, an increasing body of research has accrued on the origins and correlates of individual differences in adult attachment styles ( Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007 ). However, an important limitation of previous studies is that many failed to take into account the effect of context on the expression of attachment styles. This is surprising given that attachment theory is in essence a “person by situation” interactionist theoretical framework ( Campbell and Marshall, 2011 ; Simpson and Winterheld, 2012 ), and possibly derives from the scarcity of methods allowing for such a dynamic approach. Although significant insights have been obtained by focusing on individual differences in retrospective reports of the expression of attachment, at present there is scant knowledge regarding how attachment styles are expressed in the moment and how they play out in real-world settings ( Torquati and Raffaelli, 2004 ). The current study extends previous work by employing experience sampling methodology (ESM), a time-sampling procedure, to examine the daily life expression of adult attachment styles in a non-clinical sample of young adults.

Attachment theory is a lifespan approach that postulates that people are born with an innate motivational system (termed the attachment behavioral system) that becomes activated during times of actual or symbolic threat, prompting the individual to seek proximity to particular others with the goal of alleviating distress and obtaining a sense of security ( Bowlby, 1982 ). A cornerstone of the theory is that individuals build cognitive-affective representations, or “internal working models” of the self and others, based on their cumulative history of interactions with attachment figures ( Bowlby, 1973 ; Bartholomew and Horowitz, 1991 ). These models guide how information from the social world is appraised and play an essential role in the process of affect regulation throughout the lifespan ( Kobak and Sceery, 1988 ; Collins et al., 2004 ).

The majority of research on adult attachment has centered on attachment styles and their measurement (for a review, see Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007 ). In broad terms, attachment styles may be conceptualized in terms of security vs. insecurity. Repeated interactions with emotionally accessible and sensitively responsive attachment figures promote the formation of a secure attachment style, characterized by positive internal working models and effective strategies for coping with distress. Conversely, repeated interactions with unresponsive or inconsistent figures result in the risk of developing insecure attachment styles, characterized by negative internal working models of the self and/or others and the use of less optimal affect regulation strategies ( Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007 ).

Although there is a wide range of conceptualizations and measures of attachment insecurity, these are generally defined by high levels of anxiety and/or avoidance in close relationships. Attachment anxiety reflects a desire for closeness and a worry of being rejected by or separated from significant others, whereas attachment avoidance reflects a strong preference for self-reliance, as well as discomfort with closeness and intimacy with others ( Brennan et al., 1998 ; Bifulco and Thomas, 2013 ). These styles involve distinct secondary attachment strategies for regulating distress – individuals with attachment anxiety tend to use a hyperactivating (or maximizing) strategy, while individuals with attachment avoidance tend to rely on a deactivating (or minimizing) strategy ( Cassidy and Kobak, 1988 ; Main, 1990 ; Mikulincer and Shaver, 2003 , 2008 ). Indeed, previous empirical studies indicate that attachment anxiety is associated with increased negative emotional responses, heightened detection of threats in the environment, and negative views of the self ( Griffin and Bartholomew, 1994 ; Mikulincer and Orbach, 1995 ; Fraley et al., 2006 ; Ein-Dor et al., 2011 ). By contrast, attachment avoidance is associated with emotional inhibition or suppression, the dismissal of threatening events, and inflation of self-conceptions ( Fraley and Shaver, 1997 ; Gjerde et al., 2004 ; Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007 ).

Relatively few studies have examined attachment styles in the context of everyday life. Most of these studies have used event-contingent sampling techniques, such as the Rochester Interaction Record (RIR; Reis and Wheeler, 1991 ), and have primarily focused on assessing how individual differences in self-reported attachment are related to responses to social interactions in general and/or to specific social interactions (e.g., with acquaintances, friends, family members, close others, same- and opposite-sex peers). Despite various methodological and attachment classification differences that complicate direct comparison of these findings, this body of research has shown that compared to secure attachment, anxious (or preoccupied) attachment is associated with more variability in terms of positive emotions and promotive interactions (a composite measure of disclosure and support; Tidwell et al., 1996 ), lower self-esteem ( Pietromonaco and Barrett, 1997 ), greater feelings of anxiety and rejection, as well as perceiving more negative emotions in others ( Kafetsios and Nezlek, 2002 ). In contrast, compared to secure attachment, avoidant (or dismissing) attachment has been associated with lower levels of happiness and self-disclosure ( Kafetsios and Nezlek, 2002 ), lower perceived quality of interactions with romantic partners ( Sibley and Liu, 2006 ), a tendency to differentiate less between close and non-close others in terms of disclosure ( Pietromonaco and Barrett, 1997 ), and higher negative affect along with lower positive affect, intimacy, and enjoyment, predominantly in opposite-sex interactions ( Tidwell et al., 1996 ).

Studies using event-contingent methods such as the RIR have shed light on how varying social encounters trigger differential responses as a function of attachment style; however, since the focus is on objectively defined interactional phenomena (e.g., interactions lasting 10 min or longer), these types of paradigms are unable to capture the wide range of naturally occurring subjective states and appraisals that take place as individuals navigate through their daily life. Unlike previous research, the current study used ESM, a within-day self-assessment technique in which participants are prompted at random or predetermined intervals to answer brief questionnaires about their current experiences. ESM offers several advantages compared to traditional laboratory or clinic-based assessment procedures (e.g., deVries, 1992 ; Hektner et al., 2007 ; Conner et al., 2009 ). These include: (1) ESM repeatedly assesses participants in their daily environment, thereby enhancing ecological validity, (2) it captures information at the time of the signal, thus minimizing retrospective recall bias, and (3) it allows for investigating the context of participants’ experiences.

To our knowledge, the work of Torquati and Raffaelli (2004) is the only ESM study that has assessed how daily life experiences of emotion differed as a function of attachment category (secure vs. insecure) and context (being alone or in the presence of familiar intimates). In a sample of undergraduate students, they found that both when in the presence of familiar intimates and when alone, the secure group reported higher levels of emotions relating to energy and connection than the insecure group. Additionally, when alone, securely attached individuals reported greater levels of positive affect than insecurely attached individuals. Moreover, although the two groups did not differ in the variability of their emotional states, participants with a secure style endorsed more extreme positive emotional states across all social contexts, whereas those with insecure styles endorsed more extreme negative emotional states, particularly when they were alone. Their results supported the notion that attachment styles exert a broad influence on affective experiences; nevertheless, an important limitation of this study was that it only reported findings comparing secure vs. insecure participants, and thus it did not provide information on how the subtypes of insecure attachment differ from the secure style. Therefore, further empirical research is needed to examine how attachment styles are expressed in the flow of daily life and whether the interplay between attachment styles and the features of the environment gives rise to different patterns of experiences in the moment. Demonstrating that attachment styles exhibit meaningful associations with real-world experiences in the domains that are theoretically influenced by an individual’s attachment style would provide evidence of the validity of the attachment style construct in the immediate context in which the person is embedded. Moreover, identifying attachment-style variations in how the social context relates to momentary experiences would enhance our understanding of how attachment styles operate in the immediate social milieu.

The Current Study

The present study examines the expression of secure, anxious, and avoidant attachment styles in daily life using ESM. It extends previous research in several ways. First, the current study employs an interview, rather than a self-report measure, to assess attachment styles. The Attachment Style Interview (ASI; Bifulco et al., 2002 ) is a semi-structured interview that belongs to the social psychology approach to attachment research and has the strength of utilizing contextualized narrative and objective examples to determine the individual’s current attachment style. Second, this study examines the expression of attachment styles at random time points across participants’ daily life, not just during particular events such as social interactions, and thus captures a more extensive profile of person-environment transactions. Third, this study examines the impact of two aspects of the social context on the expression of attachment styles in the moment: social contact and perceived social closeness when with others. None of the previous diary studies have examined attachment style differences in the effects of social contact and social closeness on participants’ subjective appraisals of themselves (e.g., their coping capabilities), their current situation (e.g., how stressful it is), or their social functioning (e.g., preference for being alone).

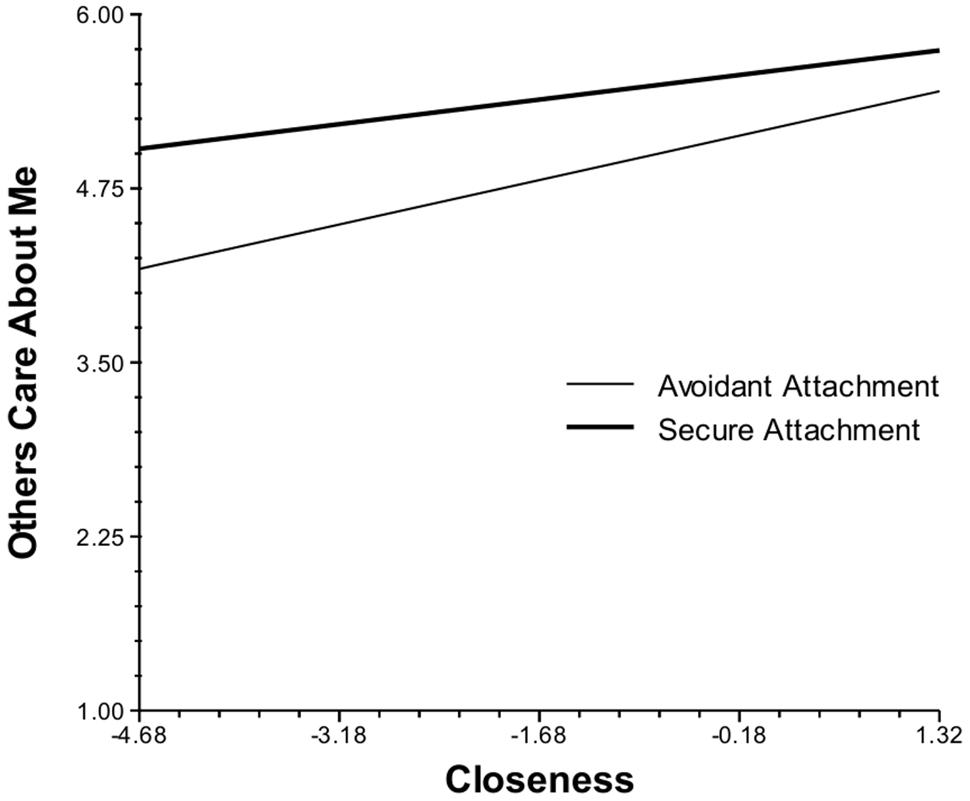

The first aim of this study was to examine the associations between attachment styles and measures of affect, cognitive appraisals (about the self, others, and the situation), and social functioning as they occur in daily life. Following attachment theory, it was hypothesized that compared to both insecure attachment groups, secure attachment would be associated with higher ratings of positive affect, self-esteem, feeling cared for, as well as with experiencing more closeness in social interactions. In terms of insecure attachment, a different pattern was predicted for the anxious and avoidant styles. We hypothesized that compared to securely attached participants, those with anxious attachment would endorse higher levels of negative affect, affect instability, subjective stress, feeling unable to cope, and perceived social rejection. We predicted that avoidant attachment, as compared with the secure style, would be associated with lower ratings of positive affect, a decreased desire to be with others when alone, and an increased preference for being alone when with others. In essence, this would provide evidence of ecological construct validity of the attachment styles.

The second aim of the current study was to investigate whether attachment styles moderate the associations of social contact and social closeness with momentary affect, appraisals, and social functioning. Given the lack of engagement and emotional distance that characterizes avoidant attachment, it was hypothesized that social contact would elicit less positive affect in avoidant participants as compared to their secure peers. Additionally, given that one of the most salient features of anxious individuals is that they desire closeness but fear rejection and abandonment, it was predicted that anxious participants would experience higher negative affect with people with whom they did not feel close, than would those with a secure attachment.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Participants were 206 (44 men, 162 women) undergraduate students recruited from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain. The mean age of the sample was 21.3 years ( SD = 2.4). An additional eight participants enrolled in the study and completed the interview phase, but were omitted from the analyses due to failing to complete the ESM protocols. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University Ethics Committee. Participants provided written informed consent and were paid for their participation.

Materials and Procedure

Participants were assessed with the ASI, along with other interview and questionnaire measures not used in the present study. The ASI is a semi-structured interview that measures current attachment style through questions that elicit the content and context of interpersonal attitudes and behaviors ( Bifulco, 2002 ). The interview is composed of two parts. In the first part, a behavioral evaluation of the ability to make and maintain relationships is made (on a 4-point scale from “marked” to “little/none”) on the basis of the overall quality of the person’s ongoing relationships with up to three supportive figures (referred to as “very close others”), including partner if applicable. The term “behavioral evaluation” denotes that ratings are based on descriptions of actual behavior (such as instances of recent confiding, emotional support received, and presence of tension/conflicts with each “very close other”). The second part of the ASI assesses individuals’ feelings and thoughts about themselves in relation to others. Specifically, ratings are obtained for seven attitudinal scales that reflect anxiety and avoidance in relationships. These scales are: fear of rejection, fear of separation, desire for company, mistrust, anger, self-reliance, and constraints on closeness. Ratings on the attitudinal scales are based on the intensity of the attitude and the level of generalization. Most of them are rated on 4-point scales from “marked” to “little/none.”

The scores obtained throughout the interview are combined to enable the classification of the person’s attachment profile, which encompasses both the attachment style categorization as well as the degree of severity for the insecure styles. Note that scoring the ASI and deriving the person’s attachment profile is done on the basis of prior training, according to established rating rules and benchmark thresholds. Further details on the scoring scheme and case examples can be found in Bifulco and Thomas (2013) . Previous studies have provided evidence for the reliability and validity of the ASI ( Bifulco et al., 2004 ; Bifulco and Thomas, 2013 ). In the present study, the three main attachment style categories (i.e., secure, anxious, and avoidant) were used for analyses.

Experience sampling methodology data were collected on palm pilot personal digital assistants (PDAs). The PDAs signaled the participants randomly eight times a day (between 10 a.m. and 10 p.m.) for 1 week to complete brief questionnaires. When prompted by the signal, the participants had 5 min to initiate responding. After this time window or upon completion of the questionnaire, the PDA would become inactive until the next signal. Each questionnaire took ∼2 min to complete.

The ESM questionnaire included items that inquired about the following domains: (1) affect in the moment, (2) appraisals about the self, (3) appraisals about others, (4) appraisals of the current situation, (5) social contact, and (6) social appraisals and functioning (see Table 1 for the English translation of the ESM items used in the present study). The social contact item (i.e., “Right now I am alone”) was answered dichotomously (yes/no), whereas the remaining items were answered using 7-point scales from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Note that for the sake of aiding the interpretation of the results we have made a distinction between affective states and cognitive appraisals; however, we recognize that such a distinction is not clear-cut and that affect and cognition are complexly intertwined processes. Likewise, we grouped appraisals as pertaining to the self, others, or the situation. This distinction is somewhat artificial but useful for organizing the presentation of the data. Note that, unlike most previous studies, the label “appraisals about others” does not refer to participants’ ratings of interaction partners, but to the manner in which participants’ experience others’ motives, actions, or esteem toward them.

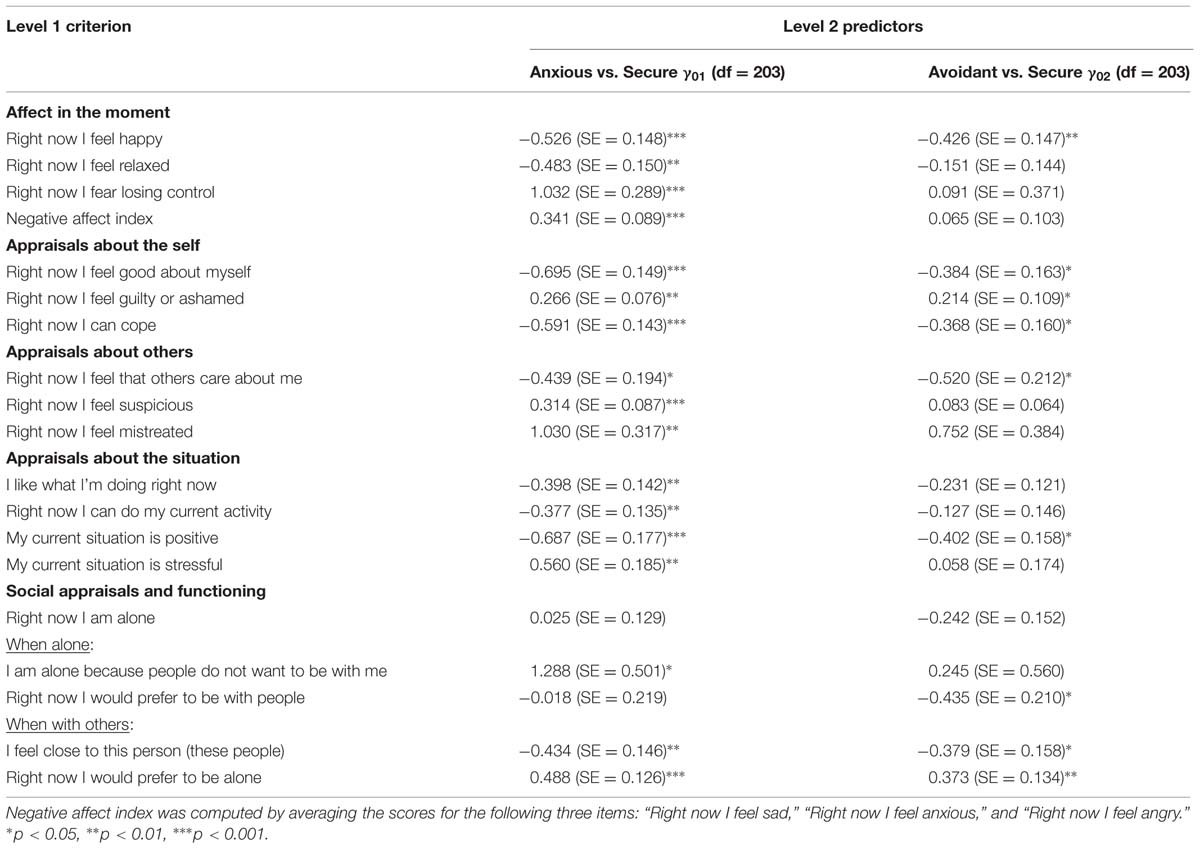

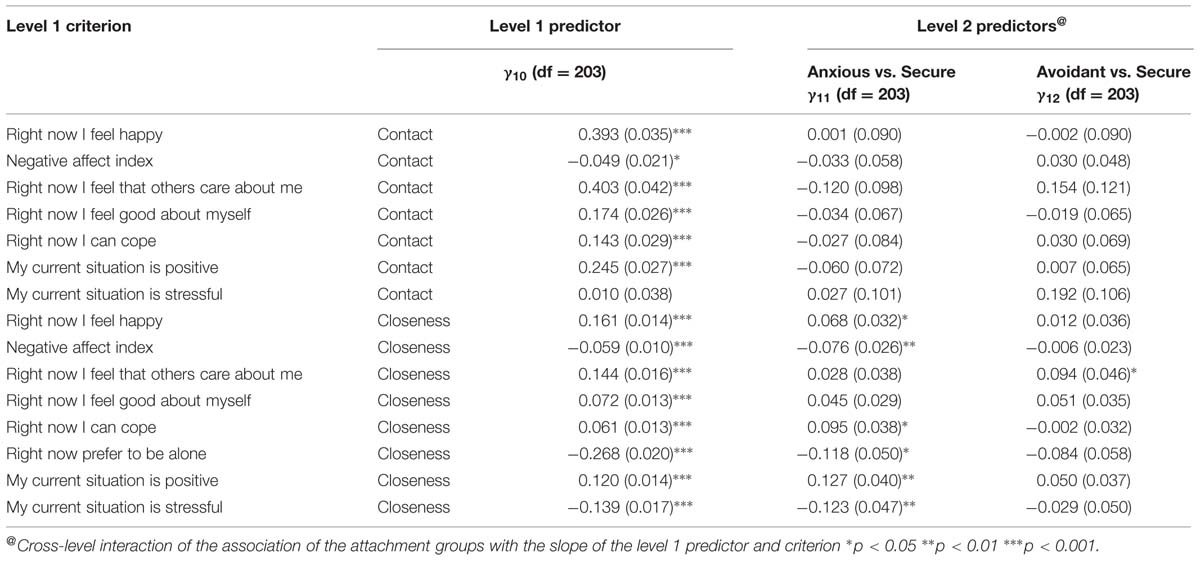

TABLE 1. Direct effects of attachment style on daily life experiences.

Statistical Method

Experience sampling methodology data have a hierarchical structure in which daily life ratings (level 1 data) are nested within participants (level 2 data). Multilevel or hierarchical linear modeling techniques are a standard approach for the analysis of ESM data ( Nezlek, 2001 ; Bolger and Laurenceau, 2013 ). The multilevel analyses examined two types of relations between the attachment groups and daily life experiences. First, we assessed the independent effects of level 2 predictors (attachment style groups) on level 1 dependent measures (ESM ratings in daily life). Second, cross-level interactions (or slopes-as-outcomes) examined whether level 1 relationships (e.g., closeness and negative affect in the moment) varied as a function of level 2 variables (attachment groups). The analyses were conducted with Mplus 6 ( Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2010 ). To examine the effects of attachment, the analyses included two dummy-coded attachment style variables that were entered simultaneously as the level 2 predictors, following Cohen et al. (2003) . The first dummy code contrasted the anxious and secure attachment groups, and the second contrasted the avoidant and secure attachment groups. The secure attachment group was coded 0 in both codings. Note that direct comparisons of the anxious and avoidant attachment groups were not made, given that our hypotheses focused on differences between secure and insecure attachment. Level 1 predictors were group-mean centered ( Enders and Tofighi, 2007 ). The data departed from normality in some cases, so parameter estimates were calculated using maximum likelihood estimation with robust SEs.

Based upon the ASI, 119 (57.8%) of the participants were categorized as having secure attachment, 46 (22.3%) as having anxious attachment, and 41 (19.9%) as having avoidant attachment. These percentages are comparable to those reported in previous studies using the ASI in non-clinical samples (e.g., Conde et al., 2011 ; Oskis et al., 2013 ). The attachment groups did not differ in terms of age or sex. Participants completed an average of 40.8 usable ESM questionnaires ( SD = 9.1). The attachment groups did not differ on the mean number of usable questionnaires (Secure = 40.8, SD = 8.2; Anxious = 40.5, SD = 9.8; Avoidant = 41.1, SD = 10.9).

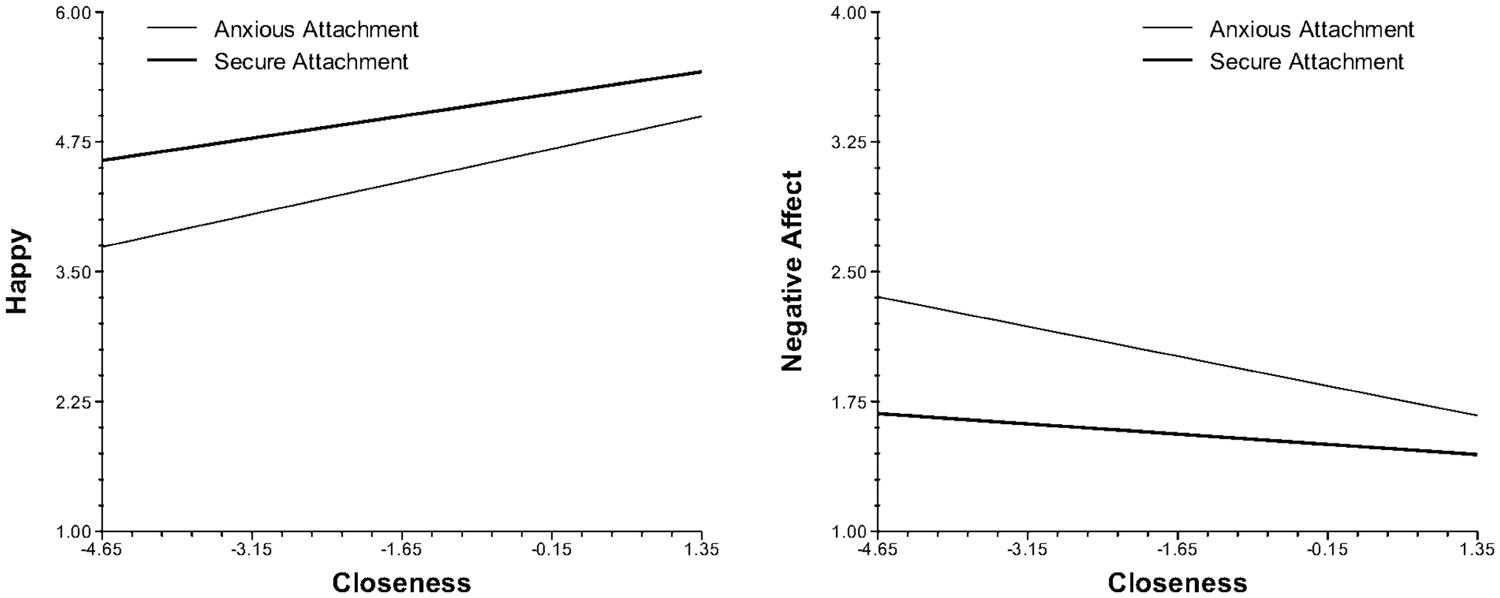

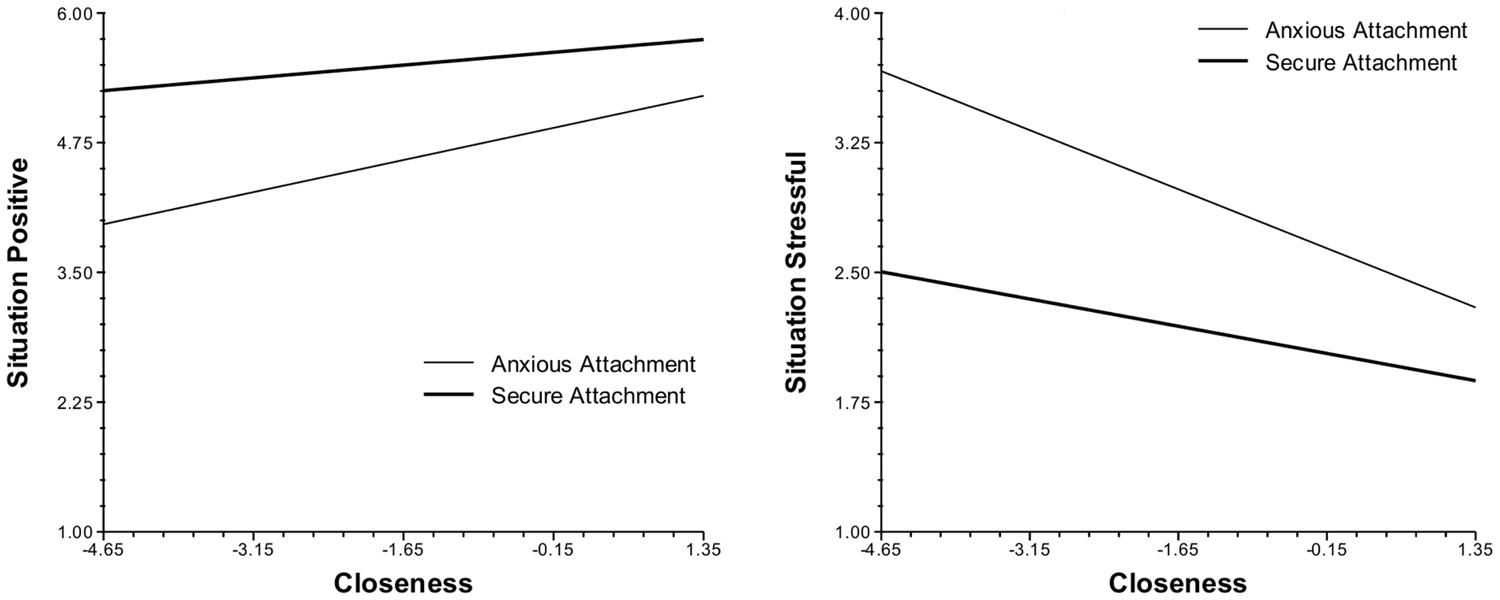

Expression of Attachment Styles in Daily Life

Table 1 presents the direct effects of attachment on daily life experiences. Compared to participants with a secure attachment, those with an anxious attachment reported higher negative affect, lower positive affect, as well as greater fear of losing control in daily life. As expected, the avoidant and secure groups did not differ in their ratings of negative affect, but avoidant participants reported feeling less happy than their secure counterparts. In addition to comparing the attachment groups on the experience of mean levels of affect in daily life, we also compared the groups on variance of affect using one-way ANOVAs. Note that this was not nested data because each participant had a single (within-person) variance score based upon their own distribution of happiness or negative affect. The ANOVA was significant for negative affect variance, F (2,203) = 5.58, p < 0.01. Post-hoc comparisons using Dunnett’s t -test indicated that the anxious attachment group exceeded the secure attachment group, p < 0.01. The avoidant and secure attachment groups did not differ. The ANOVA for happiness variance was not significant, F (2,203) = 0.48.