Legitimacy, Authority, and Power Essay

An authority that is considered to be legitimate has the liberty to exercise power. Legitimacy is the ability to be defended with valid logic and justification. Authority is the power to influence opinion, behavior, and thought. Power is the capacity to influence the behavior of others. Legitimacy involves acceptance of an enforced law as an authority, whereas power involves persuading others to do something. Power becomes an authority after getting legitimized; thus, it is more effective. This paper argues that power, authority, and legitimacy are essential factors in politics because they provide political stability. Various methods have been put into practice to make the argument, such as determining the relationship between the elements and distinguishing them from each other. This essay will address power, authority, and legitimacy and look at the relationship and differences between the aspects in regard to political stability.

Power is used in politics to implement decisions making it more efficient when it is not a source of coercion. The stability of authority depends on how power is used. Authority is the capacity of an institution, people, and order; thus, it is essential in ensuring authenticity so that people follow regulations without hesitating (Koivunen and Vuorelma, 2022). Authority substitutes two main factors; Legitimacy and Power.

The legitimacy of a rule implies that people are ready to follow regulations because they reckon decisions made as fruitful in the community (Siess and Amossy, 2022). Exercising power is not necessary when legitimacy is attached to power but rather only comes out as a symbol. Power ensures the implementation of decisions and rules through the coercion of authority but later works as a catalyst for rebellion. Power is enabled by legitimacy; many communities follow the rules based on legitimacy; thus, enforcing power is unnecessary (Gardner-McTaggart, 2022, p.1-16). If the legitimacy of a law is rendered unchaste, a rule or regulation will not be observed, irrespective of the power of authority.

Legitimacy transforms power into authority and ensures political stability. Legitimacy is a psychologically accepted practice to exercise power. A person can have legitimacy and lack power contrary; a person can also have power but lack legitimacy. Authority has a legitimate right to rule, command, and write rules and laws. Legitimacy makes a relation between authority and power and helps the community to understand that political forces and regulations within the society are justified and rightful (Amossy, 2022, p.28). The relationship between power, authority, and legitimacy creates political stability used by most developed countries. Authority is associated with consent, while political power is based on authority. Force or power exercised without authority is ineffective in the political realm because authority can only be legitimate with consent. Power becomes more effective when it is not a source of coercion; thus, power becomes authority after getting legitimized.

Power is the ability to get someone to do something without giving them a choice, while authority is the right to give commands. Authority is perceived as legitimate power granted to a person or group over others in an organization (Andreopoulos and Rosow, 2022, pp.93-95). Power is an acquired ability, while authority is a legal right that high officials concede. Research conducted by Max Weber showed that power could not be possessed; rather, one can have means of power such as resources, determination, and luck (McLean and Nix, 2022, pp.1287-1309). The major sources of power are knowledge and expertise, while the position in an office determines authority. Power enforces the individual or collective will of groups of people, while legitimacy is a socially constructed right to use power. Legitimate power comes from an individual’s organizational role.

In political science, legitimacy involves the acceptance of authority from a governing law, whereas authority denotes a specific position in a government establishment. Studies showed the distinction between authority and legitimacy in resource-exchange analysis redirected from a preoccupation with differences in charismatic and patrimonial and source and degree (Akinlabi, 2022, p.11-24). Legitimacy is a formal authority from a job title that adds a sense of order and structure to the working environment. In contrast, authority involves assigning responsibilities, making decisions, and enforcing compliance (Alter, 2022). Power, authority, and legitimacy are exercised separately and constitute different practices.

Learning about the importance of power in political stability brings changes and educates people about government possession of control and authority. A country’s stability is ensured by implementing laws that benefit the socioeconomic sector. Power is essential in human life; it acquires many structures, is evident in many customs, and appears in many places (Brannigan, 2022, pp.417-427). Political leaders can exploit power through acts of injustice, such as corruption and bribery. Knowing strategies to take when powers are exploited helps create awareness. In the presence of power, rules can be made, mended, and broken to make changes.

Laws can be broken if they minimize opportunities, create unfair practices, exploit marginalized communities, and cause damage. Restoring and creating new rules while considering people’s opinions will help establish laws that apply to everyone. The changes made through amending new rules ensure that the needs of a community are addressed. Power is an effective tool that can succeed if used correctly and for the right reasons. The argument on power in political stability is relevant in reducing individual exploitation through control and changing society.

Legitimacy and authority in politics build political stability when they are associated together. Developed countries have established political institutions to provide the basis of strength. Countries that exercise just authority and legitimacy are more likely to succeed. Before 2003, Iraq was based on political legitimacy, but after the U.S. government used military force to bring down democracy, the political system of Iraq collapsed (Sabikh, 2022, pp.72-79). Iraq has been suffering from political instability since the establishment of the modern states in 1920, and the issue further increased in 2003 (Sabikh, 2022, pp.72-79). The argument of political stability resulting from legitimacy and authority is essential in ensuring the development of a country and reinforcing government strategies.

Power, authority, and legitimacy are important aspects that contribute to political stability. Power is the ability to carry out a task, authority is a social power within organized groups, and legitimacy identifies whether authority is justified. Power is enabled by legitimacy, while legitimacy transforms power into authority. On the other hand, authority is associated with consent, while political power is based on authority. Political stability is related to the relationship between the three factors. Power, authority, and legitimacy are distinguished by definition and application. Legitimacy involves the acceptance of authority from a governing law, whereas authority denotes a specific position in a government organization. Power contributes to changes through the amendment of new regulations. Authority and legitimacy are vital in the development and growth of a country. These aspects are also essential in politics due to political stability.

Reference List

Akinlabi, O.M., 2022. Understanding Legitimacy in Weber’s Perspectives and Contemporary Society . In Police-Citizen Relations in Nigeria (pp. 11-24). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. Web.

Alter, K.J., 2022. The Contested Authority and Legitimacy of International Law: The State Strikes Back . Web.

Amossy, R. (2022). Constructing political legitimacy and authority in discourse. Argumentation and Discourse Analysis , (28). Web.

Andreopoulos, G. and Rosow, S.J., 2022. Governance, authority, and legitimacy in the global space. In Reconfigurations of Authority, Power and Territoriality (pp. 93-95). Edward Elgar Publishing. Web.

Brannigan, J., 2022. Introduction: history, power, and politics in the literary artefact. In Literary Theories (pp. 417-427). Edinburgh University Press. Web.

Gardner-McTaggart, A., 2022. Legitimacy, power, and Aesthetics in the International Baccalaureate. Globalization, Societies, and Education , pp.1-16. Web.

Koivunen, A. and Vuorelma, J., 2022. Trust and authority in the age of mediatized politics . European Journal of Communication , 37(4). Web.

McLean, K. and Nix, J., 2022. Understanding the bounds of legitimacy: Weber’s facets of legitimacy and the police empowerment hypothesis . Justice Quarterly , 39 (6), pp.1287-1309. Web.

Sabikh, D.Y., 2022. The internal causes of Iraqi political instability after 2003. World Politics , (1), pp.72-79. Web.

Siess, J. and Amossy, R., 2022. Democratic legitimacy and authority in times of Corona: Angela Merkel’s address to the nation. Argumentation and Discourse Analysis , (28). Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, December 28). Legitimacy, Authority, and Power. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legitimacy-authority-and-power/

"Legitimacy, Authority, and Power." IvyPanda , 28 Dec. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/legitimacy-authority-and-power/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Legitimacy, Authority, and Power'. 28 December.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Legitimacy, Authority, and Power." December 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legitimacy-authority-and-power/.

1. IvyPanda . "Legitimacy, Authority, and Power." December 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legitimacy-authority-and-power/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Legitimacy, Authority, and Power." December 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legitimacy-authority-and-power/.

- Public Policies and Legitimacy in Virtual Communities

- Political Legitimacy Matrix

- Impacts, Justification and Legitimacy of the U.S Invasion of Iraq

- Discussion of Online Service Providers Limiting

- Governance: Description, Benefits, and Examples

- Increasing Vocational Opportunities for the Youth

- Analysis of Iran’s Nuclear Deal

- Human vs. National Security Differences

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

14.1 Power and Authority

Learning objectives.

- Define power and the three types of authority.

- List Weber’s three types of authority.

- Explain why charismatic authority may be unstable in the long run.

Politics refers to the distribution and exercise of power within a society, and polity refers to the political institution through which power is distributed and exercised. In any society, decisions must be made regarding the allocation of resources and other matters. Except perhaps in the simplest societies, specific people and often specific organizations make these decisions. Depending on the society, they sometimes make these decisions solely to benefit themselves and other times make these decisions to benefit the society as a whole. Regardless of who benefits, a central point is this: some individuals and groups have more power than others. Because power is so essential to an understanding of politics, we begin our discussion of politics with a discussion of power.

Power refers to the ability to have one’s will carried out despite the resistance of others. Most of us have seen a striking example of raw power when we are driving a car and see a police car in our rearview mirror. At that particular moment, the driver of that car has enormous power over us. We make sure we strictly obey the speed limit and all other driving rules. If, alas, the police car’s lights are flashing, we stop the car, as otherwise we may be in for even bigger trouble. When the officer approaches our car, we ordinarily try to be as polite as possible and pray we do not get a ticket. When you were 16 and your parents told you to be home by midnight or else, your arrival home by this curfew again illustrated the use of power, in this case parental power. If a child in middle school gives her lunch to a bully who threatens her, that again is an example of the use of power, or, in this case, the misuse of power.

These are all vivid examples of power, but the power that social scientists study is both grander and, often, more invisible (Wrong, 1996). Much of it occurs behind the scenes, and scholars continue to debate who is wielding it and for whose benefit they wield it. Many years ago Max Weber (1921/1978), one of the founders of sociology discussed in earlier chapters, distinguished legitimate authority as a special type of power. Legitimate authority (sometimes just called authority ), Weber said, is power whose use is considered just and appropriate by those over whom the power is exercised. In short, if a society approves of the exercise of power in a particular way, then that power is also legitimate authority. The example of the police car in our rearview mirrors is an example of legitimate authority.

Weber’s keen insight lay in distinguishing different types of legitimate authority that characterize different types of societies, especially as they evolve from simple to more complex societies. He called these three types traditional authority, rational-legal authority, and charismatic authority. We turn to these now.

Traditional Authority

As the name implies, traditional authority is power that is rooted in traditional, or long-standing, beliefs and practices of a society. It exists and is assigned to particular individuals because of that society’s customs and traditions. Individuals enjoy traditional authority for at least one of two reasons. The first is inheritance, as certain individuals are granted traditional authority because they are the children or other relatives of people who already exercise traditional authority. The second reason individuals enjoy traditional authority is more religious: their societies believe they are anointed by God or the gods, depending on the society’s religious beliefs, to lead their society. Traditional authority is common in many preindustrial societies, where tradition and custom are so important, but also in more modern monarchies (discussed shortly), where a king, queen, or prince enjoys power because she or he comes from a royal family.

Traditional authority is granted to individuals regardless of their qualifications. They do not have to possess any special skills to receive and wield their authority, as their claim to it is based solely on their bloodline or supposed divine designation. An individual granted traditional authority can be intelligent or stupid, fair or arbitrary, and exciting or boring but receives the authority just the same because of custom and tradition. As not all individuals granted traditional authority are particularly well qualified to use it, societies governed by traditional authority sometimes find that individuals bestowed it are not always up to the job.

Rational-Legal Authority

If traditional authority derives from custom and tradition, rational-legal authority derives from law and is based on a belief in the legitimacy of a society’s laws and rules and in the right of leaders to act under these rules to make decisions and set policy. This form of authority is a hallmark of modern democracies, where power is given to people elected by voters, and the rules for wielding that power are usually set forth in a constitution, a charter, or another written document. Whereas traditional authority resides in an individual because of inheritance or divine designation, rational-legal authority resides in the office that an individual fills, not in the individual per se. The authority of the president of the United States thus resides in the office of the presidency, not in the individual who happens to be president. When that individual leaves office, authority transfers to the next president. This transfer is usually smooth and stable, and one of the marvels of democracy is that officeholders are replaced in elections without revolutions having to be necessary. We might not have voted for the person who wins the presidency, but we accept that person’s authority as our president when he (so far it has always been a “he”) assumes office.

Rational-legal authority helps ensure an orderly transfer of power in a time of crisis. When John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Vice President Lyndon Johnson was immediately sworn in as the next president. When Richard Nixon resigned his office in disgrace in 1974 because of his involvement in the Watergate scandal, Vice President Gerald Ford (who himself had become vice president after Spiro Agnew resigned because of financial corruption) became president. Because the U.S. Constitution provided for the transfer of power when the presidency was vacant, and because U.S. leaders and members of the public accept the authority of the Constitution on these and so many other matters, the transfer of power in 1963 and 1974 was smooth and orderly.

Charismatic Authority

Charismatic authority stems from an individual’s extraordinary personal qualities and from that individual’s hold over followers because of these qualities. Such charismatic individuals may exercise authority over a whole society or only a specific group within a larger society. They can exercise authority for good and for bad, as this brief list of charismatic leaders indicates: Joan of Arc, Adolf Hitler, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Jesus Christ, Muhammad, and Buddha. Each of these individuals had extraordinary personal qualities that led their followers to admire them and to follow their orders or requests for action.

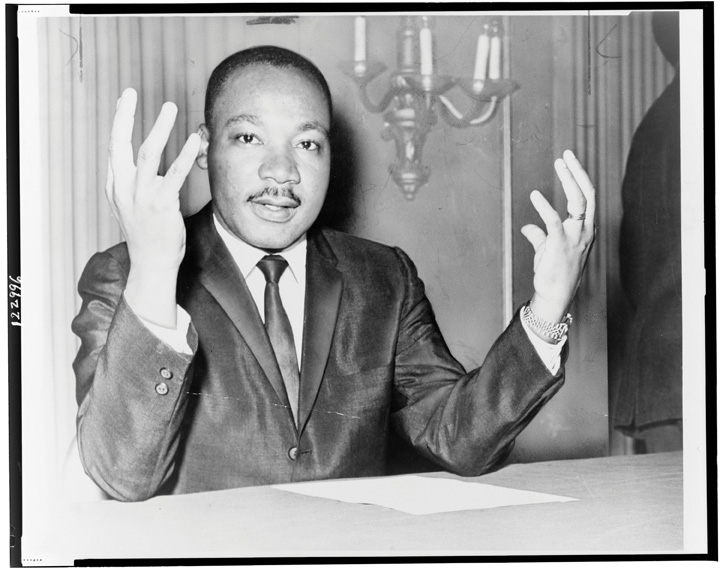

Much of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s appeal as a civil rights leader stemmed from his extraordinary speaking skills and other personal qualities that accounted for his charismatic authority.

U.S. Library of Congress – public domain.

Charismatic authority can reside in a person who came to a position of leadership because of traditional or rational-legal authority. Over the centuries, several kings and queens of England and other European nations were charismatic individuals as well (while some were far from charismatic). A few U.S. presidents—Washington, Lincoln, both Roosevelts, Kennedy, Reagan, and, for all his faults, even Clinton—also were charismatic, and much of their popularity stemmed from various personal qualities that attracted the public and sometimes even the press. Ronald Reagan, for example, was often called “the Teflon president,” because he was so loved by much of the public that accusations of ineptitude or malfeasance did not stick to him (Lanoue, 1988).

Weber emphasized that charismatic authority in its pure form (i.e., when authority resides in someone solely because of the person’s charisma and not because the person also has traditional or rational-legal authority) is less stable than traditional authority or rational-legal authority. The reason for this is simple: once charismatic leaders die, their authority dies as well. Although a charismatic leader’s example may continue to inspire people long after the leader dies, it is difficult for another leader to come along and command people’s devotion as intensely. After the deaths of all the charismatic leaders named in the preceding paragraph, no one came close to replacing them in the hearts and minds of their followers.

Because charismatic leaders recognize that their eventual death may well undermine the nation or cause they represent, they often designate a replacement leader, who they hope will also have charismatic qualities. This new leader may be a grown child of the charismatic leader or someone else the leader knows and trusts. The danger, of course, is that any new leaders will lack sufficient charisma to have their authority accepted by the followers of the original charismatic leader. For this reason, Weber recognized that charismatic authority ultimately becomes more stable when it is evolves into traditional or rational-legal authority. Transformation into traditional authority can happen when charismatic leaders’ authority becomes accepted as residing in their bloodlines, so that their authority passes to their children and then to their grandchildren. Transformation into rational-legal authority occurs when a society ruled by a charismatic leader develops the rules and bureaucratic structures that we associate with a government. Weber used the term routinization of charisma to refer to the transformation of charismatic authority in either of these ways.

Key Takeaways

- Power refers to the ability to have one’s will carried out despite the resistance of others.

- According to Max Weber, the three types of legitimate authority are traditional, rational-legal, and charismatic.

- Charismatic authority is relatively unstable because the authority held by a charismatic leader may not easily extend to anyone else after the leader dies.

For Your Review

- Think of someone, either a person you have known or a national or historical figure, whom you regard as a charismatic leader. What is it about this person that makes her or him charismatic?

- Why is rational-legal authority generally more stable than charismatic authority?

Lanoue, D. J. (1988). From Camelot to the teflon president: Economics and presidential popularaity since 1960. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press. (Original work published 1921).

Wrong, D. H. (1996). Power: Its forms, bases, and uses . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Political Legitimacy

Political legitimacy is a virtue of political institutions and of the decisions—about laws, policies, and candidates for political office—made within them. This entry will survey the main answers that have been given to the following questions. First, how should legitimacy be defined? Is it primarily a descriptive or a normative concept? If legitimacy is understood normatively, what does it entail? Some associate legitimacy with the justification of coercive power and with the creation of political authority. Others associate it with the justification, or at least the sanctioning, of existing political authority. Authority stands for a right to rule—a right to issue commands and, possibly, to enforce these commands using coercive power. An additional question is whether legitimate political authority is understood to entail political obligations or not. Most people probably think it does. But some think that the moral obligation to obey political authority can be separated from an account of legitimate authority, or at least that such obligations arise only if further conditions hold.

Next there are questions about the requirements of legitimacy. When are political institutions and the decisions made within them appropriately called legitimate? Some have argued that this question must be answered primarily on the basis of procedural features of political decision-making. Others argue that legitimacy depends—exclusively or at least in part—on the substantive values that are realized. And on what grounds is the procedure versus substance question to be settled, is it on moral grounds— relating to values such as freedom or equality—or is it on epistemic grounds—relating to the epistemic merits of how political decisions are made? A related question is: does political legitimacy demand democracy or not? Insofar as democracy is seen as necessary for political legitimacy, when are democratic decisions legitimate? Can that question be answered with reference to procedural features only, or does democratic legitimacy depend both on procedural values and on the quality of the decisions made? And what is the role of epistemic considerations in this regard? Finally, there is the question which political institutions are subject to the legitimacy requirement. Historically, legitimacy was associated with the state and institutions and decisions within the state. The contemporary literature tends to judge this as too narrow, however. This raises the question how the concept of legitimacy may apply—beyond the nation state and decisions made within it—to the international and global context.

1. Descriptive and Normative Concepts of Political Legitimacy

2.1 legitimacy and the justification of political authority, 2.2 justifying power and coercion, 2.3 political legitimacy and political obligations, 3.1 consent, 3.2 public justification and political participation, 3.3 normative facts and epistemic advantage, 4.1 democratic instrumentalism, 4.2 pure proceduralist conceptions of democratic legitimacy, 4.3 alternative conceptions of democratic legitimacy, 5.1 political nationalism, 5.2 political cosmopolitanism, other internet resources, related entries.

If legitimacy is interpreted descriptively, it refers to people’s beliefs about political authority and, sometimes, political obligations. In his sociology, Max Weber put forward a very influential account of legitimacy that excludes any recourse to normative criteria (Mommsen 1989: 20, but see Greene 2017 for an alternative reading). According to Weber, that a political regime is legitimate means that its participants have certain beliefs or faith (“Legitimitätsglaube”) in regard to it: “the basis of every system of authority, and correspondingly of every kind of willingness to obey, is a belief, a belief by virtue of which persons exercising authority are lent prestige” (Weber 1964: 382). As is well known, Weber distinguishes among three main sources of legitimacy—understood as the acceptance both of authority and of the need to obey its commands. People may have faith in a particular political or social order because it has been there for a long time (tradition), because they have faith in the rulers (charisma), or because they trust its legality—specifically the rationality of the rule of law (Weber 2009 [1918]; 1964). Weber identifies legitimacy as an important explanatory category for social science, because faith in a particular social order produces social regularities that are more stable than those that result from the pursuit of self-interest or from habitual rule-following (Weber 1964: 124).

In contrast to Weber’s descriptive concept, the normative concept of political legitimacy refers to some benchmark of acceptability or justification of political power or authority and—possibly—obligation. On one view, held by John Rawls (1993) and Arthur Ripstein (2004), for example, legitimacy refers, in the first instance, to the justification of coercive political power. Whether a political body such as a state is legitimate and whether citizens have political obligations towards it depends on whether the coercive political power that the state exercises is justified. On a widely held alternative view, legitimacy is linked to the justification of political authority. On this view, political bodies such as states may be effective, or de facto , authorities, without being legitimate. They claim the right to rule and to create obligations to be obeyed, and as long as these claims are met with sufficient acquiescence, they are authoritative. Legitimate authority, on this view, differs from merely effective or de facto authority in that it actually holds the right to rule and creates political obligations (e.g., Raz 1986). On some views, even legitimate authority is not sufficient to create political obligations. The thought is that a political authority (such as a state) may be permitted to issue commands that citizens are not obligated to obey (Dworkin 1986: 191). Based on a view of this sort, some have argued that legitimate political authority only gives rise to political obligations if additional normative conditions are satisfied (e.g. Wellman 1996; Edmundson 1998; Buchanan 2002).

There is sometimes a tendency in the literature to equate the normative concept of legitimacy with justice. Some explicitly define legitimacy as a criterion of minimal justice (e.g., Hampton 1998; Buchanan 2002). Someone might claim, for example, that while political institutions such as states are often unjust, only a just state is morally acceptable and legitimate in this sense. Unfortunately, there is sometimes also a tendency to blur the distinction between the two concepts, and a lot of confusion arises from that. Rawls (1993, 1995) clearly distinguishes between the two concepts. In his view, while justice and legitimacy are related—they draw on the same set of political values—they have different domains and legitimacy makes weaker demands than justice (1993: 225; 1995: 175ff.). Political institutions may be legitimate but unjust, but the converse is not possible: just political institutions are necessarily legitimate (see also Langvatn 2016 on this). On other views, legitimacy and justice have different normative foundations (e.g., Simmons 2001; Pettit 2012). According to Pettit (2012: 130ff), a state is just if it imposes a social order that promotes freedom as non-domination for all its citizens. It is legitimate if it imposes a social order in an appropriate way. A state that fails to impose a social order in an appropriate way, however just the social order may be, is illegitimate. Vice versa, a legitimate state may fail to impose a just social order.

Realist political theorists criticize any tendency to blur the distinction between legitimacy and justice (e.g., Rossi and Sleat 2014). They diagnose it as a sign of misplaced “political moralism” (Williams 2005; Horton 2010), or, relatedly, as a misleading interpretation of political theory as a branch of applied ethics (e.g., Honig 1993). But they also want to carve out an alternative to a purely descriptive interpretation of legitimacy. Bernard Williams’s claim (2005: 4ff) that political institutions are subject to a “basic legitimation demand” has been very influential in this regard. According to Williams, the first political question is how a state provides basic political goods such as security and stability and the conditions for cooperation. That it provides these goods is a necessary requirement for legitimacy, but it is not sufficient. A state is also under the normative expectation to justify how it provides these goods. That normative expectation is the distinctively political basic legitimation demand.

By interpreting the concept of political legitimacy along those lines, political realists lend support to those who have questioned a sharp distinction between the descriptive and normative concepts of legitimacy (e.g., Habermas 1979; Beetham 1991; Horton 2012). The objection to a strictly normative concept of legitimacy is that it is of only limited use in understanding actual processes of legitimation. The charge is that philosophers tend to focus too much on the general conditions necessary for the justification of political institutions but neglect the historical actualization of the justificatory process. In Jürgen Habermas’ words (Habermas 1979: 205): “Every general theory of justification remains peculiarly abstract in relation to the historical forms of legitimate domination. … Is there an alternative to this historical injustice of general theories, on the one hand, and the standardlessness of mere historical understanding, on the other?” The objection to a purely descriptive concept such as Weber’s is that it neglects people’s second order beliefs about legitimacy—their beliefs, not just about the actual legitimacy of a particular political institution, but about the justifiability of this institution, i.e. about what is necessary for legitimacy. According to Beetham, a “power relationship is not legitimate because people believe in its legitimacy, but because it can be justified in terms of their beliefs” (Beetham 1991: 11). As Tommie Shelby (2007) has highlighted, from the point of view of oppressed minorities political institutions often lack legitimacy because they (rightly) perceive the social order to be unjust.

A key claim of political realism is that while legitimacy is a normative property of political institutions or decisions, its normativity is not (just) moral (e.g., Rossi 2012, Sleat 2014). In support of this claim, some realists argue that the basic legitimation demand can’t be satisfied just by appeal to moral arguments, for example because political processes are necessary to forge political agreements (Stears 2007). Others focus on the role of epistemic normativity (see the discussion in Burelli and Destri 2022). But, as Leader Maynard and Worsnip (2018) ask, is there a distinct political normativity that political realists could resort to? Or does normative political philosophy have resources to address the realists’ worries? A possible reply to these questions is that realist political theory is less concerned with the nature of normativity than with drawing attention to neglected topics in political theory (Baderin 2014; Jubb 2019). But this raises the further question whether there is a unified project at the core of political realism, or whether it is better seen as the intersection of different projects motivated by a range of meta-normative, normative, and political concerns.

2. The Function of Political Legitimacy

This section lays out the different ways in which legitimacy, understood normatively, can be seen as relating to political authority, coercion, and political obligations.

The normative concept of political legitimacy is often seen as related to the justification of authority. The main function of political legitimacy, on this interpretation, is to explain the difference between merely effective or de facto authority and legitimate authority.

John Locke put forward such an interpretation of legitimacy. Locke’s starting-point is a state of nature in which all individuals are equally free to act within the constraints of natural law and no individual is subject to the will of another. As Rawls (2007: 129) characterizes Locke’s understanding of the state of nature, it is “a state of equal right, all being kings.” Natural law, while manifest in the state of nature, is not sufficiently specific to rule a society and cannot enforce itself when violated, however. The solution to this problem is a social contract that transfers political authority to a civil state that can realize and secure the natural law. According to Locke, and contrary to his predecessor Thomas Hobbes, the social contract thus does not create authority. Political authority is embodied in individuals and pre-exists in the state of nature. The social contract transfers the authority they each enjoy in the state of nature to a particular political body.

While political authority thus pre-exists in the state of nature, legitimacy is a concept that is specific to the civil state. Because the criterion of legitimacy that Locke proposes is historical, however, what counts as legitimate authority remains connected to the state of nature. The legitimacy of political authority in the civil state depends, according to Locke, on whether the transfer of authority has happened in the right way. Whether the transfer has happened in the right way depends on individuals’ consent: “no one can be put out of this estate and subjected to the political power of another without his own consent” (Locke 1980 [1690]: 52). Anyone who has given their express or tacit consent to the social contract is bound to obey a state’s laws (Locke 1980 [1690]: 63). Locke understands the consent criterion to apply not just to the original institutionalization of a political authority—what Rawls (2007: 124) calls “originating consent”. It also applies to the ongoing evaluation of the performance of a political regime—Rawls (2007: 124) calls this “joining consent”.

Although Locke emphasises consent, consent is not, however, sufficient for legitimate authority because an authority that suspends the natural law is necessarily illegitimate (e.g., Simmons 1976). On some interpretations of Locke (e.g., Pitkin 1965), consent is not even necessary for legitimate political authority; the absence of consent is only a marker of illegitimacy. Whether an actual political regime respects the constraints of the natural law is thus at least one factor that determines its legitimacy.

This criterion of legitimacy is negative: it offers an account of when effective authority ceases to be legitimate. When a political authority fails to secure consent or oversteps the boundaries of the natural law, it ceases to be legitimate and, therefore, there is no longer an obligation to obey its commands. For Locke—unlike for Hobbes—political authority can thus not be absolute.

The contemporary literature has developed Locke’s ideas in several ways. John Simmons (2001) uses them to argue that we should distinguish between the moral justification of states in general and the political legitimacy of actual states. We will come back to this point in section 3.2. Joseph Raz links legitimacy to the justification of political authority. According to Raz, political authority is just a special case of the more general concept of authority (1986, 1995, 2006). He defines authority in relation to a claim—of a person or an agency—to generate what he calls pre-emptive reasons. Such reasons replace other reasons for action that people might have. For example, if a teacher asks her students to do some homework, she expects her say-so to give the students reason to do the homework.

Authority is effective if it gets people to act on the reasons it generates. The difference between effective and legitimate authority, on Raz’ view, is that the former merely purports to change the reasons that apply to others, while legitimate authority actually has the capacity to change these reasons. Legitimate authority satisfies a pre-emption thesis: “The fact that an authority requires performance of an action is a reason for its performance which is not to be added to all other relevant reasons when assessing what to do, but should exclude and take the place of some of them” (Raz 1986: 46). (There are limits to what even a legitimate authority can rightfully order others to do, which is why it does not necessarily replace all relevant reasons.)

When is effective or de facto authority legitimate? In other words, what determines whether the pre-emption thesis is satisfied? Raz’ answer is captured in two further theses. The “dependence thesis” states that the justification of political authority depends on the normative reasons that apply to those under its rule directly, independently of the authority’s directives. Building on the dependence thesis, the “normal justification thesis” then states that political authority is justified if it enables those subject to it to better comply with the reasons that apply to them anyway. In full, the normal justification thesis says: “The normal way to establish that a person has authority over another involves showing that the alleged subject is likely to better comply with the reasons which apply to him (other than the alleged authoritative directive) if he accepts the directives of the alleged authority as authoritatively binding and tries to follow them, rather than by trying to follow the reasons which apply to him directly” (Raz 1986: 53). The normal justification thesis explains why those governed by a legitimate authority ought to treat its directives as binding. It thus follows as a corollary of the normal justification thesis that such an authority generates a duty to be obeyed. Raz calls his conception the “service conception” of authority (1986: 56). Note that even though legitimate authority is defined as a special case of effective authority, only the former is appropriately described as a serving its subjects. Illegitimate—but effective—authority does not serve those it aims to govern, although it may purport to do so.

William Edmundson formulates this way of linking authority and legitimacy via a condition he calls the warranty thesis: “If being an X entails claiming to F , then being a legitimate X entails truly claiming to F .” (Edmundson 1998: 39). Being an X here stands for “a state”, or “an authority”. And “to F ” stands for “to create a duty to be obeyed”, for example. The idea expressed by the warranty thesis is that legitimacy morally justifies an independently existing authority such that the claims of the authority become moral obligations.

Those who link political legitimacy to the problem of justifying authority tend to think of political coercion as only a means that legitimate states may use to secure their authority. As Leslie Green puts it: “Coercion threats provide secondary, reinforcing motivation when the political order fails in its primary normative technique of authoritative guidance” (Green 1988: 75). According to a second important view, held by Rawls (1993), for example, the main function of legitimacy is precisely to justify coercive power. (For an excellent discussion of the two interpretations of legitimacy and a defense of the coercion-based interpretation, see Ripstein 2004; see also Hampton 1998.) On coercion-based interpretations, the main problem that a conception of legitimacy aims to solve is how to distinguish the rightful use of political power from mere coercion. Whether a political body such as a state is legitimate and whether citizens have political obligations towards it depends, on this view on whether the coercive political power that the state exercises is justified. Again, there are different ways in which this idea might be understood.

In Thomas Hobbes’ influential account, political authority is created by the social contract. In the state of nature, everyone’s self-preservation is under threat, and this makes it rational for all to consent to a covenant that authorizes a sovereign who can guarantee their protection and to transfer their rights to this sovereign—an individual or a group of individuals. When there is no such sovereign, one may be created by a covenant—Hobbes calls this “sovereignty by institution”. But political authority may also be established by the promise of all to obey a threatening power (“sovereignty by acquisition”; see Leviathan , chapter 17). Both manners of creating a sovereign are equally legitimate. And political authority will be legitimate as long as the sovereign ensures the protection of the citizens, as Hobbes believes that the natural right to self-preservation cannot be relinquished ( Leviathan , chapter 21). Beyond that, however, there can be no further questions about the legitimacy of the sovereign. In particular, there is no distinction between effective authority and legitimate authority in Hobbes’ thought. It might even be argued that Hobbes fails to distinguish between legitimate authority and the mere exercise of power (Korsgaard 1997: 29; see chapter 30 of Leviathan , however, for an account of the quality of the sovereign’s rule).

Another way in which the relation between legitimacy and the creation of authority may be understood is that the attempt to rule without legitimacy is an attempt to exercise coercive power—not authority. Such a view can be found in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s work. Legitimacy, for Rousseau, justifies the state’s exercise of coercive power and creates an obligation to obey. Rousseau contrasts a legitimate social order with a system of rules that is merely the expression of power. Coercive power is primarily a feature of the civil state. While there are some forms of coercive power even in the state of nature—for example the power of parents over their children—Rousseau assumes that harmful coercive power arises primarily in the civil state and that this creates the problem of legitimacy. In the first chapter of the first book of On the Social Contract he remarks that while “[m]an is born free”, the civil state he observes makes everyone a slave. Rousseau’s main question is under what conditions a civil state, which uses coercive power to back up its laws, can be thought of as freeing citizens from this serfdom. Such a state would be legitimate. As he puts it in the opening sentence of the Social Contract , “I want to inquire whether there can be some legitimate and sure rule of administration in the civil order, taking men as they are and laws as they might be.”

Rousseau’s account of legitimacy is importantly different from Locke’s in that Rousseau does not attach normativity to the process through which a civil state emerges from the state of nature. Legitimate political authority is created by convention, reached within the civil state. Specifically, Rousseau suggests that legitimacy arises from the democratic justification of the laws of the civil state ( Social Contract I:6; cf. section 3.3. below).

For Immanuel Kant, as for Hobbes, political authority is created by the establishment of political institutions in the civil state. It does not pre-exist in individuals in the state of nature. What exists in the pre-civil social state, according to Kant, is the moral authority of each individual qua rational being and a moral obligation to form a civil state. Establishing a civil state is “in itself an end (that each ought to have )” (Kant, Theory and Practice 8:289; see also Perpetual Peace , Appendix I). Kant regards the civil state as a necessary first step toward a moral order (the “ethical commonwealth”). It helps people conform to certain rules by eliminating what today would be called the free-riding problem or the problem of partial compliance. By creating a coercive order of public legal justice, “a great step is taken toward morality (though it is not yet a moral step), toward being attached to this concept of duty even for its own sake” (Kant, Perpetual Peace 8:376, notes to Appendix I; see also Riley 1982: 129 f ).

The civil state, according to Kant, establishes the rights necessary to secure equal freedom. Unlike for Locke and his contemporary followers, however, coercive power is not a secondary feature of the civil state, necessary to back up laws. According to Kant, coercion is part of the idea of rights. The thought can be explained as follows. Coercion is defined as a restriction of the freedom to pursue one’s own ends. Any right of a person—independently of whether it is respected or has been violated—implies a restriction for others. (cf. Kant, Theory and Practice , Part 2; Ripstein 2004: 8; Flikschuh 2008: 389f). Coercion, in this view, is thus not merely a means for the civil state to enforce rights as defenders of an authority-based concept of legitimacy claim. Instead, according to Kant, it is constitutive of the civil state. This understanding of rights links Kant’s conception of legitimacy to the justification of coercion.

Legitimacy, for Kant, depends on a particular interpretation of the social contract. For Kant, the social contract which establishes the civil state is not an actual event. He accepts David Hume’s objection to Locke that the civil state is often established in an act of violence (Hume “Of the Original Contract”). Kant invokes the social contract, instead, as the test “of any public law’s conformity with right” (Kant Theory and Practice 8:294). The criterion is the following: each law should be such that all individuals could have consented to it. The social contract, according to Kant, is thus a hypothetical thought experiment, meant to capture an idea of public reason. As such, it sets the standard for what counts as legitimate political authority. Because of his particular interpretation of the social contract, Kant is not a social contract theorist in the strict sense. The idea of a contract is nevertheless relevant for his understanding of legitimacy. (On the difference between voluntaristic and rationalistic strands in liberalism, see Waldron 1987.)

Kant, unlike Hobbes, recognizes the difference between legitimate and effective authority. For the head of the civil state is under an obligation to obey public reason and to enact only laws to which all individuals could consent. If he violates this obligation, however, he still holds authority, even if his authority ceases to be legitimate. This view is best explained in relation to Kant’s often criticized position on the right to revolution. Kant famously denied that there is a right to revolution (Kant, Perpetual Peace , Appendix II; for a recent discussion, see Flikschuh 2008). Kant stresses that while “a people”—as united in the civil state—is sovereign, its individual members are under the obligation to obey the head of the state thus established. This obligation is such that it is incompatible with a right to revolution. Kant offers a transcendental argument for his position (Kant Perpetual Peace , Appendix II; Arendt 1992). A right to revolution would be in contradiction with the idea that individuals are bound by public law, but without the idea of citizens being bound by public law, there cannot be a civil state—only anarchy. As mentioned earlier, however, there is a duty to establish a civil state. Kant’s position implies that the obligation of individuals to obey a head of state is not conditioned upon the ruler’s performance. In particular, the obligation to obey does not cease when the laws are unjust.

Kant’s position on the right to revolution may suggest that he regards political authority as similarly absolute as Hobbes. But Kant stresses that the head of state is bound by the commands of public reason. This is manifest in his insistence on freedom of the pen: “a citizen must have, with the approval of the ruler himself, the authorization to make known publicly his opinions about what it is in the ruler’s arrangements that seems to him to be a wrong against the commonwealth” (Kant Theory and Practice 8:304). While there is no right to revolution, political authority is only legitimate if the head of state respects the social contract. But political obligations arise even from illegitimate authority. If the head of state acts in violation of the social contract and hence of public reason, for example by restricting citizens’ freedom of political criticism, citizens are still obligated to obey.

In 2004, Ripstein argued that much of the contemporary literature on political legitimacy has been dominated by a focus on the justification of authority, rather than coercive political power (Ripstein 2004). In the literature since then, it looks as if the tables are turning, especially if one considers the debates on international and global legitimacy (section 5). But prominent earlier coercion-based accounts include those by Nagel (1987) and by contemporary Kantians such as Rawls and Habermas (to be discussed in sections 3.3. and 4.3., respectively).

Let me briefly mention other important coercion-based interpretations. Jean Hampton (1998; drawing on Anscombe 1981) offers an elegant contemporary explication of Hobbes’ view. According to her, political authority “is invented by a group of people who perceive that this kind of special authority as necessary for the collective solution of certain problems of interaction in their territory and whose process of state creation essentially involves designing the content and structure of that authority so that it meets what they take to be their needs” (Hampton 1998: 77). Her theory links the authority of the state to its ability to enforce a solution to coordination and cooperation problems. Coercion is the necessary feature that enables the state to provide an effective solution to these problems, and the entitlement to use coercion is what constitutes the authority of the state. The entitlement to use coercion distinguishes such minimally legitimate political authority from a mere use of power. Hampton draws a further distinction between minimal legitimacy and what she calls full moral legitimacy, which obtains when political authority is just.

Buchanan (2002) also argues that legitimacy is concerned with the justification of coercive power. Buchanan points out that this makes legitimacy a more fundamental normative concept than authority. Like Hampton, he advocates a moralized interpretation of legitimacy. According to him, “an entity has political legitimacy if and only if it is morally justified in wielding political power” (2002: 689). Political authority, in his approach, obtains if an entity is legitimate in this sense and if some further conditions, relating to political obligation, are met (2002: 691). Anna Stilz (2009) offers a coercion-centered account of state legitimacy that draws on both Kant and Rousseau.

Historically speaking, the dominant view has been that legitimate political authority entails political obligations. Locke, for example, writes: “every man, by consenting with others to make one body politic under one government, puts himself under an obligation to every one of that society to submit to the determination of the majority, and to be concluded by it; or else this original compact, whereby he with others incorporates into one society, would signify nothing, and be no compact if he be left free and under no other ties than he was in before in the state of nature” (Locke 2009 [1690]: 52f).

While this is still the view many hold, not all do. Some take the question of what constitutes legitimate authority to be distinct from the question of what political obligations people have. Ronald Dworkin (1986: 191) treats political obligations as a fundamental normative concept in its own right. What he calls “associative obligations” arise, not from legitimate political authority, but directly from membership in a political community. (For a critical discussion of this account, see Simmons 2001; Wellman 1996.)

Arthur Applbaum (2019) offers a conceptual argument to challenge the view that legitimate political authority entails an obligation to obey. Applbaum grants that legitimate political authority has the capacity to change the normative status of those under its rule, as Raz (1986), for example, has influentially argued, and that this capacity should be interpreted as a moral power in Hohfeld’s sense, not as a claim right to rule. But, Applbaum argues, Hohfeldian powers, unlike rights, are not correlated with duties; they are correlated with liabilities. On Applbaum’s view, legitimate political authority thus has the capacity to create a liability for those under its rule, but not an obligation. To be liable to legitimate political authority means to not be free from the authority’s power or control. To be sure, the liability might be to be subject to a duty, but to be liable to be put under a duty to obey should not be confused with being under a duty to obey (see also Perry 2013 on this distinction).

Views that dissociate legitimate authority from political obligation have some appeal to those who aim to counter Robert Paul Wolff’s influential anarchist argument. The argument highlights what today is sometimes called the subjection problem (Perry 2013): how can autonomous individuals be under a general—content-independent—obligation to subject their will to the will of someone else? A content-independent obligation to obey the state is an obligation to obey a state’s directives as such, independently of their content. Wolff (1970) argues that because there cannot be such a general obligation to obey the state, states are necessarily illegitimate.

Edmundson (1998) has a first response to the anarchist challenge. He argues that while legitimacy establishes a justification for the state to issue directives, it does not create even a prima facie duty to obey its commands. He claims that the moral duty to obey the commands of legitimate political authority arises only if additional conditions are met.

Simmons (2001) has a different response to Wolff. Simmons draws a distinction between the moral justification of states and the political legitimacy of a particular, historically realized, state and its directives. According to Simmons, the state’s justification depends on its moral defensibility. If it can successfully be shown that having a state is morally better than not having a state (Simmons 2001: 125), the state is justified. But moral justification is only necessary, not sufficient, for political legitimacy, according to Simmons. The reason is that our moral obligations are to everyone, including citizens of other states, not to the particular state we live in. A particular state’s legitimacy, understood as the capacity to generate and enforce a duty to obey, depends on citizens’ actual consent. While there is no general moral duty to obey the particular state we live in, we may have a political obligation to obey if we have given our prior consent to this state. The absence of a general moral duty to obey the state thus does not imply that all states are necessarily illegitimate (Simmons 2001: 137).

3. Sources of Political Legitimacy

Insofar as legitimacy, understood normatively, determines which political institutions and which decisions made within them are justified or acceptable, and, in some cases, what kind of obligations people who are governed by these institutions incur, there is the question of what makes political institutions and political decisions legitimate. As we’ll see, this question has both a normative and a meta-normative dimension (see Peter 2023 for more on this distinction). This section briefly reviews different accounts that have been given of the sources of legitimacy.

While there is a strong voluntarist line of thought in Christian political philosophy, it was in the 17 th century that consent came to be seen as the main source of political legitimacy. The works of Hugo Grotius, Hobbes, and Samuel Pufendorf tend to be seen as the main turning point that eventually led to the replacement of natural law and divine authority theories of legitimacy (see Schneewind 1998; Hampton 1998). The following passage from Grotius’ On the Law of War and Peace expresses the modern perspective: “But as there are several Ways of Living, some better than others, and every one may chuse which he pleases of all those Sorts; so a People may chuse what Form of Government they please: Neither is the Right which the Sovereign has over his Subjects to be measured by this or that Form, of which divers Men have different Opinions, but by the Extent of the Will of those who conferred it upon him” (cited by Tuck 1993: 193). It was Locke’s version of social contract theory that elevated consent to the main source of the legitimacy of political authority.

Raz helpfully distinguishes among three ways in which the relation between consent and legitimate political authority may be understood (1995: 356): (i) consent of those governed is a necessary condition for the legitimacy of political authority; (ii) consent is not directly a condition for legitimacy, but the conditions for the legitimacy of authority are such that only political authority that enjoys the consent of those governed can meet them; (iii) the conditions of legitimate political authority are such that those governed by that authority are under an obligation to consent. There is a question, however, whether versions of (ii) and (iii) are best understood as versions of a consent theory of political legitimacy, or whether they are versions of an alternative justificationist theory (Stark 2000; Peter 2023).

Locke and his contemporary followers such as Robert Nozick (1974) or Simmons (2001), but also Rousseau and his followers defend a version of (i)—the most typical form that consent theories take. Amanda Greene (2016) defends a version of this view she calls the quality consent view. One question that all versions of (i) must address is whether consent must be explicit or whether tacit consent, expressed by residency, is sufficient (see Puryear 2021 for a defence of the latter).

Versions of (ii) appeal to those who reject actual consent as a basis for legitimacy, as they only regard consent given under ideal conditions as binding. Theories of hypothetical consent, such as those articulated by Kant or Rawls, fall into this category. Such theories view political authority as legitimate only if those governed would consent under certain ideal conditions (cf. section 3.2).

David Estlund (2008: 117ff) defends a version of hypothetical consent theory that matches category (iii). What he calls “normative consent” is a theory that regards non-consent to authority, under certain conditions as invalid. Authority, in this view, may thus be justified without actual consent. Estlund defines authority as the moral power to require action. Estlund uses normative consent theory as the basis for an account of democratic legitimacy, understood as the permissibility of using coercion to enforce authority. The work that normative consent theory does in Estlund’s account is that it contributes to the justification of the authority of the democratic collective over those who disagree with certain democratically approved laws.

Although consent theory has been dominating for a long time, there are many well-known objections to it. As we will explain more fully in the next section, Simmons (2001) argues that hypothetical consent theories (and, presumably, normative consent theories, too) conflate moral justification with legitimation, and that only actual consent can legitimize political institutions. Other objections, especially to Lockean versions, are about as old as consent theory itself. David Hume, in his essay “Of the Original Contract”, and many after him object to Locke that consent is not feasible, and that actual states have almost always arisen from acts of violence. The attempt to legitimize political authority via consent is thus, at best, wishful thinking (Wellman 1996). What is worse, it may obscure problematic structures of subordination (Pateman 1988). Hume’s own solution to this problem was, like Bentham later, to propose to justify political authority with reference to its beneficial consequences (see section 3.3).

An important legacy of consent theory in contemporary thought is manifest in accounts that attribute the source of legitimacy either to an idea of public reason—taking the lead from Kant—or to a theory of democratic participation—taking the lead from Rousseau. Theories of deliberative democracy combine elements of both accounts.

Public reason accounts tend to focus on the problem of justifying political coercion. The solution they propose is that political coercion is justified if it is supported on the basis of reasons that all reasonable persons can share. Interest in public reason accounts started with Rawls’ Political Liberalism, but Rawls developed the idea more fully in later works. Rawls’ starting-point is the following problem of legitimacy (Rawls 2001: 41): “in the light of what reasons and values … can citizens legitimately exercise … coercive power over one another?” The solution to this problem that Rawls proposes is the following “liberal principle of legitimacy”: “political power is legitimate only when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution (written or unwritten) the essentials of which all citizens, as reasonable and rational, can endorse in the light of their common human reason” (Rawls 2001: 41; see Michelman 2022 for an extensive discussion of constitutional essentials).

Rawls’ idea of public reason, which is at the core of the liberal principle of legitimacy, rests on the method of “political”—as opposed to “metaphysical”—justification that Rawls has developed in response to critics of his theory of justice as fairness (Rawls 1993). This means that public reason should be “freestanding” in the same way as his theory of justice is. Public reason should involve only political values and be independent of—potentially controversial—comprehensive moral or religious doctrines of the good. This restricts the content of public reason to what is given by the family of what Rawls calls political conceptions of justice (Rawls 2001: 26). Rawls recognizes that because the content of the idea of public reason is restricted, the domain to which it should apply must be restricted too. The question is: in what context is it important that the restriction on reason is observed? Rawls conceives of the domain of public reason as limited to matters of constitutional essentials and basic justice and as applying primarily—but not only—to judges, government officials, and candidates for public office when they decide on matters of constitutional essentials and basic justice.

Simmons (2001) criticizes Rawls’ approach for mistakenly blurring the distinction between justifying the state and political legitimacy (see also section 2.3.). A Rawlsian could reply, however, that the problem of legitimacy centrally involves the justification of coercion, and that legitimacy should thus be understood as what creates—rather than merely justifies—political authority. The following thought supports this claim. Rawls—in Political Liberalism —explicitly focuses on the democratic context. It is a particular feature of democracy that the right to rule is created by those who are ruled. As Hershovitz puts it in his critique of the Razian approach to political legitimacy, in a democracy there is no sharp division between the “binders” and the “bound” (2003: 210f). The political authority of democracy is thus entailed by some account of the conditions under which citizens may legitimately exercise coercive power over one another (see Viehoff 2014 and Kolodny 2023 on this question). But even if Simmons’ objection can be refuted in this way, a further problem for public reason accounts is whether they can successfully show that some form of public justification is indeed required for political legitimacy (see Enoch 2015).

Recent public reason accounts have developed Rawls’ original idea in different ways (see also the entry on public reason). Those following Rawls more closely will understand public reasons as reasons that attract a—hypothetical—consensus. On this interpretation, a public reason is a reason that all reasonable persons can be expected to endorse. The target of the consensus is either the political decisions themselves or the procedure through which political decisions are made. On a common reading today, the Rawlsian idea of public reason is understood in terms of a hypothetical consensus on substantive reasons (e.g., Quong 2011; Hartley and Watson 2018). On those conceptions, the use of political coercion is legitimate if it is supported by substantive reasons that all reasonable persons can be expected to endorse. The problem with this interpretation of public reason is that the demand for a consensus on substantive reasons in circumstances of moral and religious pluralism and disagreement either relies on a very restrictive characterization of reasonable persons or ends up with a very limited domain for legitimate political coercion.

Rawls’ conception of political legitimacy can also be understood in terms of procedural reasons (Peter 2008). On this interpretation, the domain of public reason is limited to the justification of the process of political decision-making, and need not extend to the substantive (as opposed to the procedural) reasons that justify a decision. For example, if public reason supports democratic decision-making, then the justification for a decision is that it has been made democratically. Of course, a political decision that is legitimate in virtue of the procedure in which it has been made may not be fully just. But this is just a reflection of the fact that legitimacy is a weaker idea than justice.

An alternative interpretation of the public reason account focuses on convergence, not consensus (Gaus 2011; Vallier 2011; Vallier and Muldoon 2020). A political decision is legitimized on the basis of public reason, on this account, if reasonable persons can converge on that decision. They need not agree on the—substantive or procedural—reasons that support a decision. Instead, it is argued, it is sufficient for political legitimacy if all can agree that a particular decision should be made, even if they disagree about the reasons that support this decision. Note that the convergence needs not be actual; it can be hypothetical.

Accounts that emphasize political participation or political influence regard a political decision as legitimate only if it has been made in a process that allows for equal participation of all relevant persons. They thus see political legitimacy as dependent on the participation or influence of all, to paraphrase Bernard Manin’s (1987) expression, not on the will of all, as consent theories do, or on a justification all can access, as public reason accounts do. Older accounts of this kind focus on democratic participation (Pateman 1970). Newer accounts include deliberative democracy accounts (Manin 1987), Philipp Pettit’s equal control view (Pettit 2012), and Lafont’s theory of democratic legitimacy (Lafont 2019).

Rousseau’s solution to the problem of how to explain the legitimacy of political decisions has influenced many contemporary democratic theorists (see section 4.3.). One of the important departures from Locke’s version of social contract theory that Rousseau proposes is that tacit consent is not sufficient for political legitimacy. Without citizens’ active participation in the justification of a state’s laws, Rousseau maintains, there is no legitimacy. According to Rousseau, one’s will cannot be represented, as this would distort the general will, which alone is the source of legitimacy: “The engagements that bind us to the social body are obligatory only because they are mutual… the general will, to be truly such, should be general in its object as well as in its essence; … it should come from all to apply to all; and … it loses its natural rectitude when it is directed towards any individual, determinate object” (Rousseau, Social Contract , II:4; see also ibid . I:3 and Rawls 2007: 231f).

Rousseau distinguishes among a citizen’s private will, which reflects personal interests, a citizen’s general will, which reflects an interpretation of the common good, and the general will, which truly reflects the common good. A democratic decision is always about the common good. In democratic decision-making, citizens thus compare their interpretations of the general will. If properly conducted, it reveals the general will. This is the legitimate decision.

Active participation by all may not generate a consensus. So why would those who oppose a particular decision be bound by that decision? Rousseau’s answer to this question is the following. On Rousseau’s view, citizens can—and will want to—learn from democratic decisions. Since the democratic decision, if conducted properly, correctly reveals the general will, those who voted against a particular proposal will recognize that they were wrong and will adjust their beliefs about what the general will is. In this ingenious way, individuals are only bound by their own will, but everyone is bound by a democratic decision.

The theories of political legitimacy reviewed in the previous two sections take the citizens’ will, whether expressed through their actual consent, supported by shared or converging reasons, or established through processes of political participation, as the ground of political legitimacy. While such will-based conceptions have dominated the philosophical literature on political legitimacy, they are not the only conceptions on offer. There are two main alternatives, as well as hybrid conceptions (see Peter 2023). A first alternative are fact-based conceptions of political legitimacy, according to which the legitimacy of political institutions and decisions depends on whether they accord with normative facts. Utilitarian theories, which focus on the beneficial consequences of political institutions and the decisions made within them, are a good example. According to belief-based conceptions, as articulated in epistocratic conceptions and in some epistemic theories of democracy, the source of political legitimacy is some form of epistemic advantage that supports the justification of political decisions. In this section, we expand on the two main alternatives to will-based conceptions of political legitimacy.

In the utilitarian view, legitimate political authority should be grounded on the principle of utility. The relevant normative facts are facts concerning the maximization of happiness or utility. Christian Thomasius, a student of Pufendorf and contemporary of Locke, may be seen as a precursor of the utilitarian approach to political legitimacy, as he rejected voluntarism and endorsed the idea that political legitimacy depends on principles of rational prudence instead (Schneewind 1998: 160; Barnard 2001: 66). Where Thomasius differs from the utilitarians, however, is in his attempt to identify a distinctively political—not moral or legal—source of legitimacy. He developed the idea of “decorum” into a theory of how people should relate to one another in the political context. Decorum is best described as a principle of “civic mutuality” (Barnard 2001: 65): “You treat others as you would expect them to treat you” (Thomasius, Foundations of the Law of Nature and of Nations , quoted by Barnard 2001: 65). By thus distinguishing legitimacy from legality and justice, Thomasius adopted an approach that was considerably ahead of his time.

Jeremy Bentham (in Anarchical Fallacies ) rejects the Hobbesian idea that political authority is created by a social contract. According to Bentham, it is the state that creates the possibility of binding contracts. The problem of legitimacy that the state faces is which of its laws are justified. Bentham proposes that legitimacy depends on whether a law contributes to the happiness of the citizens. (For a contemporary take on this utilitarian principle of legitimacy, see Binmore 2000.)

A well-known problem with the view that Bentham articulates is that it justifies restrictions of rights that liberals find unacceptable. John Stuart Mill’s answer to this objection consists, on the one hand, in an argument for the compatibility between utilitarianism and the protection of liberty rights and, on the other, in an instrumentalist defense of democratic political authority based on the principle of utility. According to Mill, both individual freedom and the right to participate in politics are necessary for the self-development of individuals (Mill On Liberty and Considerations on Representative Government , see Brink 1992; Ten 1998).

With regard to the defense of liberty rights, Mill argues that the restriction of liberty is illegitimate unless it is permitted by the harm principle, that is, unless the actions suppressed by the restriction harm others ( On Liberty , chapter 1; for a critical discussion of the harm principle as the basis of legitimacy, see Wellman 1996; see also Turner 2014). Mill’s view of the instrumental value of (deliberative) democracy is expressed in the following passage of the first chapter of On Liberty : “Despotism is a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, provided that the end be their improvement and the means justified by actually effecting that end. Liberty, as a principle, has no application to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being improved by free and equal discussion.” Deliberation is important, according to Mill, because of his belief in the power of ideas—in what Habermas would later call the force of the better argument (Habermas 1990: 158ff). Deliberation should keep partisan interests, which could threaten legitimacy by undermining the general happiness, in check: “The representative system ought … not to allow any of the various sectional interests to be so powerful as to be capable of prevailing against truth and justice and the other sectional interests combined. There ought always to be such a balance preserved among personal interests as may render any one of them dependent for its successes, on carrying with it at least a large proportion of those who act on higher motives, and more comprehensive and distant views” (Mill, Collected Works XIX: 447, cited by Ten 1998: 379).

Many are not convinced that such instrumentalist reasoning provides a satisfactory account of political legitimacy. Rawls (1971:175ff) and Jeremy Waldron (1987: 143ff) object that the utilitarian approach will ultimately only convince those who stand to benefit from the felicific calculus, and that it lacks an argument to convince those who stand to lose.

Can fact-based conceptions of political legitimacy address this problem? Fair play theories offer one solution to this problem (see Klosko 2004 and the entry on political obligation ). Wellman’s (1996) samaritan account of political legitimacy is also an attempt to overcome this problem. In his account, a state’s legitimacy depends on it being justified to use coercion to enforce its laws. His suggestion is that the justification of the state can be grounded in the samaritan duty to help others in need. The thought is that “what ultimately legitimizes a state’s imposition upon your liberty is not merely the services it provides you , but the benefits it provides others ” (Wellman 1996: 213; his emphasis). Wellman argues that because “political society is the only vehicle with which people can escape the perils of the state of nature” (Wellman 1996: 216), people have a samaritan duty to provide to one another the benefits of a state. Associated restrictions of their liberty by the state, Wellman claims, are legitimate.