- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1E: Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 7932

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Ethnocentrism, in contrast to cultural relativism, is the tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of one’s own culture.

Learning Objectives

- Examine the concepts of ethnocentrism and cultural relativism in relation to your own and other cultures in society

- Ethnocentrism often entails the belief that one’s own race or ethnic group is the most important or that some or all aspects of its culture are superior to those of other groups.

- Within this ideology, individuals will judge other groups in relation to their own particular ethnic group or culture, especially with concern to language, behavior, customs, and religion.

- Cultural relativism is the belief that the concepts and values of a culture cannot be fully translated into, or fully understood in, other languages; that a specific cultural artifact (e.g., a ritual) has to be understood in terms of the larger symbolic system of which it is a part.

- Cultural relativism is the principle that an individual person’s beliefs and activities should be understood by others in terms of that individual’s own culture.

- ethnocentrism : The tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of one’s own culture.

- cultural relativism : Cultural relativism is a principle that was established as axiomatic in anthropological research by Franz Boas in the first few decades of the twentieth century, and later popularized by his students. Boas first articulated the idea in 1887: “…civilization is not something absolute, but… is relative, and… our ideas and conceptions are true only so far as our civilization goes. “

Ethnocentrism, a term coined by William Graham Sumner, is the tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of your own ethnic culture and the belief that that is in fact the “right” way to look at the world. This leads to making incorrect assumptions about others’ behavior based on your own norms, values, and beliefs. For instance, reluctance or aversion to trying another culture’s cuisine is ethnocentric. Social scientists strive to treat cultural differences as neither inferior nor superior. That way, they can understand their research topics within the appropriate cultural context and examine their own biases and assumptions at the same time.

This approach is known as “cultural relativism.” Cultural relativism is the principle that an individual person’s beliefs and activities should be understood by others in terms of that individual’s own culture. A key component of cultural relativism is the concept that nobody, not even researchers, comes from a neutral position. The way to deal with our own assumptions is not to pretend that they don’t exist but rather to acknowledge them, and then use the awareness that we are not neutral to inform our conclusions.

An example of cultural relativism might include slang words from specific languages (and even from particular dialects within a language). For instance, the word “tranquilo” in Spanish translates directly to “calm” in English. However, it can be used in many more ways than just as an adjective (e.g., the seas are calm). Tranquilo can be a command or suggestion encouraging another to calm down. It can also be used to ease tensions in an argument (e.g., everyone relax) or to indicate a degree of self-composure (e.g., I’m calm). There is not a clear English translation of the word, and in order to fully comprehend its many possible uses, a cultural relativist would argue that it would be necessary to fully immerse oneself in cultures where the word is used.

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

Ethnocentrism is the tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of one’s own culture. Part of ethnocentrism is the belief that one’s own race, ethnic or cultural group is the most important or that some or all aspects of its culture are superior to those of other groups. Some people will simply call it cultural ignorance.

Ethnocentrism often leads to incorrect assumptions about others’ behavior based on your own norms, values, and beliefs. In extreme cases, a group of individuals may see another culture as wrong or immoral and because of this may try to convert, sometimes forcibly, the group to their own ways of living. War and genocide could be the devastating result if a group is unwilling to change their ways of living or cultural practices.

Ethnocentrism may not, in some circumstances, be avoidable. We often have involuntary reactions toward another person or culture’s practices or beliefs but these reactions do not have to result in horrible events such as genocide or war. In order to avoid conflict over culture practices and beliefs, we must all try to be more culturally relative.

Cultural relativism is the principle of regarding and valuing the practices of a culture from the point of view of that culture and to avoid making hasty judgments. Cultural relativism tries to counter ethnocentrism by promoting the understanding of cultural practices that are unfamiliar to other cultures such as eating insects, genocides or genital cutting. Take for example, the common practice of same-sex friends in India walking in public while holding hands. This is a common behavior and a sign of connectedness between two people. In England, by contrast, holding hands is largely limited to romantically involved couples, and often suggests a sexual relationship. These are simply two different ways of understanding the meaning of holding hands. Someone who does not take a relativistic view might be tempted to see their own understanding of this behavior as superior and, perhaps, the foreign practice as being immoral.

D espite the fact that cultural relativism promotes the appreciation for cultural differences, it can also be problematic. At its most extreme, cultural relativism leaves no room for criticism of other cultures, even if certain cultural practices are horrific or harmful. Many practices have drawn criticism over the years. In Madagascar, for example, the famahidana funeral tradition includes bringing bodies out from tombs once every seven years, wrapping them in cloth, and dancing with them. Some people view this practice disrespectful to the body of the deceased person. Today, a debate rages about the ritual cutting of genitals of girls in several Middle Eastern and African cultures. To a lesser extent, this same debate arises around the circumcision of baby boys in Western hospitals. When considering harmful cultural traditions, it can be patronizing to use cultural relativism as an excuse for avoiding debate. To assume that people from other cultures are neither mature enough nor responsible enough to consider criticism from the outside is demeaning.

The concept of cross-cultural relationship is the idea that people from different cultures can have relationships that acknowledge, respect and begin to understand each other’s diverse lives. People with different backgrounds can help each other see possibilities that they never thought were there because of limitations, or cultural proscriptions, posed by their own traditions. Becoming aware of these new possibilities will ultimately change the people who are exposed to the new ideas. This cross-cultural relationship provides hope that new opportunities will be discovered, but at the same time it is threatening. The threat is that once the relationship occurs, one can no longer claim that any single culture is the absolute truth.

Culture and Psychology Copyright © 2020 by L D Worthy; T Lavigne; and F Romero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Ethnocentrism

Introduction.

- Definitions

- Disciplinary Precursors

- Progressivism

- Primitivism

- Nineteenth-Century Evolutionism

- Boasian Anthropology

- Struggle against Racism

- Functionalism

- Malinowski’s Personal Writings

- Postmodern Thought

- Sociocultural Anthropology

- Disease Avoidance

- Ebonics or African American Language (AAL)

- Archaeology

- Applied Anthropology

- Interdisciplinary Connections

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Agriculture

- Anthropology of Islam

- Bronisław Malinowski

- Cultural Relativism

- Culture and Personality

- Culture of Poverty

- E.E. Evans-Pritchard

- Eric R. Wolf

- Ethnography in Antiquity

- Linguistic Relativity

- Science Studies

- Whorfian Hypothesis

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Anthropology of Corruption

- University Museums

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Ethnocentrism by Elizabeth Baylor LAST REVIEWED: 11 January 2012 LAST MODIFIED: 11 January 2012 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199766567-0045

Ethnocentrism is a term applied to the cultural or ethnic bias—whether conscious or unconscious—in which an individual views the world from the perspective of his or her own group, establishing the in-group as archetypal and rating all other groups with reference to this ideal. This form of tunnel vision often results in: (1) an inability to adequately understand cultures that are different from one’s own and (2) value judgments that preference the in-group and assert its inherent superiority, thus linking the concept of ethnocentrism to multiple forms of chauvinism and prejudice, including nationalism, tribalism, racism, and even sexism and disability discrimination. Ethnocentrism is a concept that was coined within anthropology and formed the cornerstone of its early evolutionary theory before becoming one of the discipline’s primary social critiques. It continues to both challenge and inspire anthropologists, shifting in meaning and application with theoretical trends and across the subdisciplines. For many anthropologists in the Boasian tradition, ethnocentrism is the antithesis of anthropology, a mind-set that it actively counters through cultural relativism, education, and applied activities such as cultural brokering. Physical anthropologists have tended to define the concept more generally as preferential cooperation with a defined in-group and to interrogate its potential evolutionary origins, while the postmodern trend has been a growing suspicion of the anthropologist’s own ability to transcend cultural bias in his or her analysis and presentation of the “other,” leading to an emphasis on reflexivity and subjective diversity. Outside of the discipline, ethnocentrism is a topic of study for biologists, political scientists, communication experts, psychologists, and sociologists, particularly in the areas of politics, identity, and conflict. Marketing has seized on the term to describe consumers who prefer domestically produced goods, and the derivative ethnocentric has become a common criticism in the era of globalization for those assuming their own cultural superiority.

General Overviews and Foundational Texts

It is difficult to identify a definitive text for the concept of ethnocentrism, given its shifting meanings and common usage as an implicit critique. Sumner 1906 provides the original formulation of the term, defining it as a “view of things in which one’s own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it.” While Sumner is commonly credited with coining the term, ethnocentric was previously used in McGee 1900 to characterize what he termed the primitive mind-set. Levine and Campbell 1972 provides one of the most comprehensive and research-friendly definitions, drawing on the literature from anthropology, sociology, psychology, political science, and economics to create a set of twenty-three testable characteristics. Yet while Levine and Campbell 1972 combines in-group and out-group directed characteristics, many theorists have argued for a decoupling of these concepts, further problematizing the issue of defining ethnocentrism (see Definitions ). See Murdock 1949 for a classic formulation of ethnocentrism as a universal form of in-group consciousness and Herskovits 1948 for a standard reading of the term as a human cultural feature with an implied value judgment.

Herskovits, Melville J. 1948. Man and his works . New York: Knopf.

Classic definition of ethnocentrism as a feeling of superiority regarding one’s own culture or way of life.

Levine, Robert A., and Donald T. Campbell. 1972. Ethnocentrism: Theories of conflict, ethnic attitudes, and group behavior . New York: Wiley.

The author draws on literature from anthropology, sociology, psychology, political science, and economics in this text to define ethnocentrism as a set of twenty-three characteristics, nine of which are attitudes toward a perceived in-group (e.g., perceptions of superiority and virtue, sanctions against murder and theft) and fourteen of which are toward a perceived out-group (e.g., blaming, distrust, fear).

McGee, William J. 1900. Primitive numbers. Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report 19:821–851.

Early source predating the classic Sumner 1906 definition. In this work, McGee uses the term ethnocentric to describe the dominant orientation characterizing primitive thought and action.

Murdock, George P. 1949. Social structure . New York: Macmillan.

Provides a useful alternative understanding of the concept of ethnocentrism, defining it as a “tendency to exalt the in-group and to depreciate other groups” (pp. 83–84).

Sumner, William G. 1906. Folkways: A study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals . New York: Mentor.

Publication credited with coining the term ethnocentrism .

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Anthropology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Africa, Anthropology of

- Animal Cultures

- Animal Ritual

- Animal Sanctuaries

- Anorexia Nervosa

- Anthropocene, The

- Anthropological Activism and Visual Ethnography

- Anthropology and Education

- Anthropology and Theology

- Anthropology of Kurdistan

- Anthropology of the Senses

- Anthrozoology

- Antiquity, Ethnography in

- Archaeobotany

- Archaeological Education

- Archaeology and Museums

- Archaeology and Political Evolution

- Archaeology and Race

- Archaeology and the Body

- Archaeology, Gender and

- Archaeology, Global

- Archaeology, Historical

- Archaeology, Indigenous

- Archaeology of Childhood

- Archaeology of the Senses

- Art Museums

- Art/Aesthetics

- Autoethnography

- Bakhtin, Mikhail

- Bass, William M.

- Benedict, Ruth

- Binford, Lewis

- Bioarchaeology

- Biocultural Anthropology

- Biological and Physical Anthropology

- Biological Citizenship

- Boas, Franz

- Bone Histology

- Bureaucracy

- Business Anthropology

- Cargo Cults

- Charles Sanders Peirce and Anthropological Theory

- Christianity, Anthropology of

- Citizenship

- Class, Archaeology and

- Clinical Trials

- Cobb, William Montague

- Code-switching and Multilingualism

- Cognitive Anthropology

- Cole, Johnnetta

- Colonialism

- Commodities

- Consumerism

- Crapanzano, Vincent

- Cultural Heritage Presentation and Interpretation

- Cultural Heritage, Race and

- Cultural Materialism

- Cultural Resource Management

- Culture, Popular

- Curatorship

- Cyber-Archaeology

- Dalit Studies

- Dance Ethnography

- de Heusch, Luc

- Deaccessioning

- Design, Anthropology and

- Digital Anthropology

- Disability and Deaf Studies and Anthropology

- Douglas, Mary

- Drake, St. Clair

- Durkheim and the Anthropology of Religion

- Economic Anthropology

- Embodied/Virtual Environments

- Emotion, Anthropology of

- Environmental Anthropology

- Environmental Justice and Indigeneity

- Ethnoarchaeology

- Ethnocentrism

- Ethnographic Documentary Production

- Ethnographic Films from Iran

- Ethnography

- Ethnography Apps and Games

- Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography

- Ethnomusicology

- Ethnoscience

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E.

- Evolution, Cultural

- Evolutionary Cognitive Archaeology

- Evolutionary Theory

- Experimental Archaeology

- Federal Indian Law

- Feminist Anthropology

- Film, Ethnographic

- Forensic Anthropology

- Francophonie

- Frazer, Sir James George

- Geertz, Clifford

- Gender and Religion

- GIS and Archaeology

- Global Health

- Globalization

- Gluckman, Max

- Graphic Anthropology

- Haraway, Donna

- Healing and Religion

- Health and Social Stratification

- Health Policy, Anthropology of

- Heritage Language

- House Museums

- Human Adaptability

- Human Evolution

- Human Rights

- Human Rights Films

- Humanistic Anthropology

- Hurston, Zora Neale

- Identity Politics

- India, Masculinity, Identity

- Indigeneity

- Indigenous Boarding School Experiences

- Indigenous Economic Development

- Indigenous Media: Currents of Engagement

- Industrial Archaeology

- Institutions

- Interpretive Anthropology

- Intertextuality and Interdiscursivity

- Laboratories

- Language and Emotion

- Language and Law

- Language and Media

- Language and Race

- Language and Urban Place

- Language Contact and its Sociocultural Contexts, Anthropol...

- Language Ideology

- Language Socialization

- Leakey, Louis

- Legal Anthropology

- Legal Pluralism

- Liberalism, Anthropology of

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistics, Historical

- Literary Anthropology

- Local Biologies

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude

- Malinowski, Bronisław

- Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, and Visual Anthropology

- Maritime Archaeology

- Material Culture

- Materiality

- Mathematical Anthropology

- Matriarchal Studies

- Mead, Margaret

- Media Anthropology

- Medical Anthropology

- Medical Technology and Technique

- Mediterranean

- Mendel, Gregor

- Mental Health and Illness

- Mesoamerican Archaeology

- Mexican Migration to the United States

- Militarism, Anthropology and

- Missionization

- Morgan, Lewis Henry

- Multispecies Ethnography

- Museum Anthropology

- Museum Education

- Museum Studies

- NAGPRA and Repatriation of Native American Human Remains a...

- Narrative in Sociocultural Studies of Language

- Nationalism

- Needham, Rodney

- Neoliberalism

- NGOs, Anthropology of

- Niche Construction

- Northwest Coast, The

- Oceania, Archaeology of

- Paleolithic Art

- Paleontology

- Performance Studies

- Performativity

- Perspectivism

- Philosophy of Museums

- Plantations

- Political Anthropology

- Postprocessual Archaeology

- Postsocialism

- Poverty, Culture of

- Primatology

- Primitivism and Race in Ethnographic Film: A Decolonial Re...

- Processual Archaeology

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Anthropology

- Public Archaeology

- Public Sociocultural Anthropologies

- Religion and Post-Socialism

- Religious Conversion

- Repatriation

- Reproductive and Maternal Health in Anthropology

- Reproductive Technologies

- Rhetoric Culture Theory

- Rural Anthropology

- Sahlins, Marshall

- Sapir, Edward

- Scandinavia

- Secularization

- Settler Colonialism

- Sex Estimation

- Sign Language

- Skeletal Age Estimation

- Social Anthropology (British Tradition)

- Social Movements

- Socialization

- Society for Visual Anthropology, History of

- Socio-Cultural Approaches to the Anthropology of Reproduct...

- Sociolinguistics

- Sound Ethnography

- Space and Place

- Stable Isotopes

- Stan Brakhage and Ethnographic Praxis

- Structuralism

- Studying Up

- Sub-Saharan Africa, Democracy in

- Surrealism and Anthropology

- Technological Organization

- Trans Studies in Anthroplogy

- Transnationalism

- Tree-Ring Dating

- Turner, Edith L. B.

- Turner, Victor

- Urban Anthropology

- Virtual Ethnography

- Visual Anthropology

- Willey, Gordon

- Wolf, Eric R.

- Writing Culture

- Youth Culture

- Zora Neale Hurston and Visual Anthropology

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.154]

- 81.177.182.154

1.3 Overcoming Ethnocentrism

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define the concept of ethnocentrism and explain the ubiquity of ethnocentrism as a consequence of enculturation.

- Distinguish certain forms of ethnocentrism in terms of their historical relationship to forms of empire and domination.

- Identify primitivism in European and American representations of African peoples.

- Identify orientalism in European and American representations of Asian and Middle Eastern peoples.

Have you ever known somebody who seems to think the world revolves around them? The kind of friend who is always talking about themselves and never asks any questions about you and your life? The kind of person who thinks their own ideas are cool and special and their own way of doing things is absolutely the best? You may know the word used to describe that kind of person: egocentric. An egocentric person is entirely caught up in their own perspective and does not seem to care much about the perspectives of others. It is good to feel proud of your personal qualities and accomplishments, of course, but it is equally important to appreciate the personal qualities and accomplishments of others as well.

The same sort of “centric” complex operates at the level of culture. Some people in some cultures are convinced that their own ways of understanding the world and of doing things are absolutely the best and no other ways are worth consideration. They imagine that the world would be a much better place if the superior beliefs, values, and practices of their own culture were spread or imposed on everyone else in the world. This is what we call ethnocentrism .

Enculturation and Ethnocentrism

We are all brought up in a particular culture with particular norms and values and ways of doing things. Our parents or guardians teach us how to behave in social situations, how to take care of our bodies, how to lead a good life, and what we should value and think about. Our teachers, religious leaders, and bosses give us instruction about our roles, responsibilities, and relationships in life. By the time we are in our late teens or early twenties, we know a great deal about how our society works and our role in that society.

Anthropologists call this process of acquiring our particular culture enculturation . All humans go through this process. It is natural to value the particular knowledge gained through our own process of enculturation because we could not survive without it. It is natural to respect the instruction of our parents and teachers who want us to do well in life. It is good to be proud of who we are and where we came from. However, just as egocentrism is tiresome, it can be harmful for people to consider their own culture so superior that they cannot appreciate the unique qualities and accomplishments of other cultures. When people are so convinced that their own culture is more advanced, morally superior, efficient, or just plain better than any other culture, we call that ethnocentrism. When people are ethnocentric, they do not value the perspectives of people from other cultures, and they do not bother to learn about or consider other ways of doing things.

Beyond the sheer rudeness of ethnocentrism, the real problem emerges when the ethnocentrism of one group causes them to harm, exploit, and dominate other groups. Historically, the ethnocentrism of Europeans and Euro-Americans has been used to justify subjugation and violence against peoples from Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas. In the quest to colonize territories in these geographical areas, Europeans developed two main styles of ethnocentrism, styles that have dominated popular imagination over the past two centuries. These styles each identify a cultural “self” as European and a cultural other as a stereotypical member of a culture from a specific region of the world. Using both of these styles of ethnocentrism, Europeans strategically crafted their own coherent self-identity in contrast to these distorted images of other cultures.

Primitivism and Orientalism

Since the 18th century, views of Africans and Native Americans have been shaped by the obscuring lens of primitivism . Identifying themselves as enlightened and civilized, Europeans came to define Africans as ignorant savages, intellectually inferior and culturally backward. Nineteenth-century explorers such as Henry M. Stanley described Africa as “the dark continent,” a place of wildness and depravity (Stanley 1878). Similarly, European missionaries viewed Africans as simple heathens, steeped in sin and needing Christian redemption. Elaborated in the writings of travelers and traders, primitivism depicts Africans and Native Americans as exotic, simple, highly sexual, potentially violent, and closer to nature. Though both African and Native American societies of the time were highly organized and well-structured, Europeans often viewed them as chaotic and violent. An alternative version of primitivism depicts Africans and Native Americans as “noble savages,” innocent and simple, living in peaceful communities in harmony with nature. While less overtly insulting, the “noble savage” version of primitivism is still a racist stereotype, reinforcing the notion that non-Western peoples are ignorant, backward, and isolated.

Europeans developed a somewhat different style of ethnocentrism toward people from the Middle East and Asia, a style known as orientalism . As detailed by literary critic Edward Said (1979), orientalism portrays peoples of Asia and the Middle East as irrational, fanatical, and out of control. The “oriental” cultures of East Asia and Middle East are depicted as mystical and alluring. The emphasis here is less on biology and nature and more on sensual and emotional excess. Middle Eastern societies are viewed not as lawless but as tyrannical. Relations between men and women are deemed not just sexual but patriarchal and exploitative. Said argues that this view of Asian and Middle Eastern societies was strategically crafted to demonstrate the rationality, morality, and democracy of European societies by contrast.

In his critique of orientalism, Said points to the very common representation of Muslim and Middle Eastern peoples in mainstream American movies as irrational and violent. In the very first minute of the 1992 Disney film Aladdin , the theme song declares that Aladdin comes from “a faraway place / where the caravan camels roam / where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face / it’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.” Facing criticism by antidiscrimination groups, Disney was forced to change the lyrics for the home video release of the film (Nittle 2021). Many thrillers such as the 1994 film True Lies , starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, cast Arabs as America-hating villains scheming to plant bombs and take hostages. Arab women are frequently portrayed as sexualized belly dancers or silent, oppressed victims shrouded in veils. These forms of representation draw from and reproduce orientalist stereotypes.

Both primitivism and orientalism were developed when Europeans were colonizing these parts of the world. Primitivist views of Native Americans justified their subjugation and forced migration. In the next section, we’ll explore how current versions of primitivism and orientalism persist in American culture, tracing the harmful effects of these misrepresentations and the efforts of anthropologists to dismantle them.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-anthropology/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Jennifer Hasty, David G. Lewis, Marjorie M. Snipes

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Anthropology

- Publication date: Feb 23, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-anthropology/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-anthropology/pages/1-3-overcoming-ethnocentrism

© Dec 20, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 October 2022

A cross-cultural comparison of ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate between two collectivistic cultures

- Muhammad Yousaf 1 ,

- Muneeb Ahmad 2 ,

- Deqiang Ji 3 ,

- Dianlin Huang 4 &

- Syed Hassan Raza 5

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 17087 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

9293 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

There is a prevalent notion regarding divergence in the extent of ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate across cultures. Given this cultural divergence, research is replete with comparative studies of ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate between individualistic and collectivistic cultures. However, to our knowledge, a comparison of these crucial cultural tendencies within and their consequences for collectivistic cultures has been overlooked. Thus, this study provides a cross-cultural comparison of ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate among university students from two collectivist cultures, i.e., Pakistan and China. The researchers employed a cross-sectional design. A sample of 775 students was collected using a survey technique. The findings show that Pakistani students are more ethnocentric and have a lower intercultural willingness to communicate than Chinese students. Moreover, males were found to be more ethnocentric and less willing to communicate in intercultural settings than females in both countries. These findings validate the notion of ethnocentrism divergence across collectivistic countries and its influence on the intercultural willingness to communicate. Additionally, they demonstrate the role of demographic attributes in evolving ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate. Accordingly, these findings also confirm the ecological assumption that contextual factors, such as demographic attributes (e.g., past interactions with foreigners), influence communication schemas. Therefore, concerning its management, these findings suggest that increased people-to-people interactions between the two focal countries can better foster their mutual understanding to reap an increased harvest of the fruits of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Insider-outsider: Methodological reflections on collaborative intercultural research

Cultural diversity in unequal societies sustained through cross-cultural competence and identity valuation

Cultural distances between home and host countries inspire sojourners to engage in intercultural exchange upon repatriation

Introduction.

Ethnocentrism is a global phenomenon and influences social interaction 1 , 2 . It has been the source of ethnic strains in different regions, such as South Africa and Lebanon 3 . It is assumed to be a twisted form of racism—a prejudice in individuals’ thinking regarding people they perceive to be the same ethnicity as themselves 4 and a negative treatment of those who belong to a different ethnicity 5 . However, most ethnocentric research compares individualistic cultures (e.g., the US and Western Europe) with collectivistic cultures (e.g., Korea, Japan and China) 6 , 7 , 8 . It is acknowledged that individualistic (Western) cultures emphasize the content of communications via the explicit and direct meanings of these communications. In contrast, collectivist (Eastern) cultures mainly value the context of communications 9 , 10 , i.e., meanings are implicit, indirect and context orientated. For that reason, people from collectivistic cultures are relatively more ethnocentric than people from individualistic cultures 11 . Put differently, collectivistic cultures are interdependent, i.e., group decisions are valued more than in individualistic cultures that emphasize personal decisions. Collectivistic individuals are more likely to associate themselves with their cultural group, which corresponds to increased ethnocentrism. Consequently, it is more likely that people show increased prejudice and discrimination in collectivistic cultures than in individualistic cultures 10 . To this end, some scholars have suggested that members of a collectivist culture are anticipated to exhibit distinct ethnocentric attitudes. However, the idea that collectivistic cultures are more ethnocentric than individualistic cultures has not been consistently supported by empirical studies. In this regard, the results show varying trends among both individualistic and collectivistic cultures 8 . For instance, for Korean students 6 and Chinese students 12 , researchers have reported a lower level of ethnocentrism than among American students, while Japanese students are reported to have a higher level of ethnocentrism than US students 3 . Moreover, international students have scored lower in ethnocentrism from the Malaysian perspective 13 . In contrast, Pakistani university students are more ethnocentric than their Chinese counterparts 14 . These inconsistent findings echo the involvement of various understudied ecological antecedents, which may make the extent of ethnocentrism salient in diverse cultures, irrespective of any patterns narrated in prior cultural models.

Ethnocentrism has an impact on the willingness to communicate, particularly the intercultural willingness to communicate. As a result, it affects the way members of different cultures show the intercultural willingness to communicate. To date, the intercultural willingness to communicate (IWTC) scale has been used by researchers in Australia 15 , Estonia 16 , Micronesia 17 , New Zealand 18 , Russia 19 Sweden 20 , and, quite recently, in New Zealand 21 . The intercultural willingness to communicate (IWTC) scale is different from the willingness to communicate (WTC) scale. The WTC refers to people’s communication tendencies with friends, colleagues, and strangers. In contrast, the IWTC relates to people’s willingness to be involved in communication encounters with people from different cultures, races, and backgrounds 7 . Ethnocentrism influences the intercultural willingness to communicate among people of different cultures 3 , 22 . In this context, researchers have found that the more ethnocentric an individual is, the less tendency toward communication the individual shows in intercultural settings 23 , 24 . Likewise, it has been found that ethnocentrism influences individuals’ understanding of other cultures and upholds their love for their own culture. However, these results are not consistent 25 . Some researchers have found that Korean students are both less ethnocentric and less interculturally willing to communicate than American students 6 . Similarly, it has been concluded that Romanian students have a higher ethnocentric score and lower IWTC than their American counterparts 7 . Moreover, it has found that Pakistani students are more ethnocentric and have less IWTC than Chinese students 26 .

However, it has been found that New Zealand’s management students have a moderate ethnocentric score and that they are also moderate in their intercultural willingness to communicate 21 . Furthermore, the researchers have shown that differences even exist among Asian countries with regard to ethnocentrism and the IWTC in their cross-cultural interactions 6 , 7 . In a recent study, conducted in Portugal, it has been found that ethnocentrism hinders intercultural communication interactions 27 .

However, despite an increased interest in ethnocentrism and its impact on the IWTC, it is surprising that little empirical research has been conducted in collectivistic cultures while considering possible ecological antecedents. Therefore, what remains to be investigated is how ethnocentrism influences intercultural willingness in collectivistic cultures such as China and Pakistan, where the extended network of family and friends is given much importance. This requires a careful examination of the questions that explain how ecological settings, such as demographic attributes among individuals, influence their interactions while communicating with others that draws from past studies (see for review 28 ) that suggest individuals uphold demographic attributes that may influence their patterns of actions based on their ecological environment. Nevertheless, both nations are culturally diverse in terms of their cultural dimensions and cultural orientations (see for review 29 ). Correspondingly, these cultural dimensions serve as each society’s collective schemas, guiding the members of a particular society to behave in a specific condition 30 .

Recently, both Pakistan and China have engaged in joint projects ranging from student exchange programs to developmental projects under the Belt & Road Initiative umbrella. Both countries, being collectivistic, provide a unique context for investigating the influence of ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate. Thus, it is timely to offer a deeper understanding to policy-makers regarding the intercultural communication relations between the nationals of these two nations. Therefore, this study investigates the extent of ethnocentrism among Pakistani and Chinese students and how it influences their intercultural willingness to communicate in cultural and ecological settings while interacting with outgroups. To the best of our knowledge, there is not a single study that has documented the influence of ethnocentrism on the intercultural willingness to communicate in the context of collectivistic cultures. To address this gap in the literature, this study, therefore, contributes to our understanding of how people from two collectivistic cultures with a different set of values, emotions, and communicative norms interact with one another in intercultural settings.

Literature review

Theoretically unpacking the concept of culture.

The extensive social sciences literature is categorized into either the ‘essentialist’ or ‘no essentialist’ view of culture 31 . The former is termed positivist, and the latter is labeled ‘interpretive’. Hofstede is considered the proponent of the ‘essentialist’ notion of culture. This view posits that culture within a nation emphasizes categorizing people into different groups based on certain qualities (ibid). Likewise, one’s culture is also differentiated from that of others according to a set of essential qualities. In this view, culture is felt, experienced and seen by other individuals. This promotes stereotyping, i.e., we treat in-groups as superior and outgroups as inferior. In other words, we treat those who come from our own culture different than those who belong to a separate culture. In contrast, the nonessentialist notion of culture treats culture as a moveable entity. In this view, people treat culture as a different thing in different places. The essentialist notion is also called ‘Orientalist’, i.e., people treat cultures as we/them categories. Outgroups are considered inferior and weak, and in-groups are treated favorably and deemed superior 31 . In this study, we have adopted an essentialist notion of culture. The literature is replete with evidence that cultural dimensions influence intercultural interactions; however, this study unswervingly investigates how ethnocentric traits drive communicative actions, such as the willingness to communicate. Compared to past studies that compare the intercultural willingness to communicate between countries based on their individualist vs. collectivist cultural variability, we argue that ethnocentrism can affect the communicative actions of the people in different cultures with the same cultural variability. This is in line with theoretical notions that any ethnocentrism inhibits intercultural communication. Drawing on the orientalist standpoint, the degree of ethnocentric traits determines the evasion that leads to outlining one’s communicative predispositions. In summary, when individuals interact with people from other cultures, they sense dissimilarities, including those in communicative patterns. Most people respond to these differences with an ethnocentric approach, employing their communicative norms that they consider appropriate. As such, when intercultural encounters occur, people apply their own cognitive framework—outlined by their degree of ethnocentrism—and judge any differences, which can lead to an unwillingness to communicate. Further implications of this process are delineated in the next sections.

Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism is a crucial concept for understanding social interactions among individuals in different cultures. Sumner first introduced the term ethnocentrism to the social sciences literature. He defined it as “the technical name for this view of things in which one’s own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it” (p. 13) 32 . That is, one group considers itself superior to other groups. In another study 33 , it has been maintained that ethnocentrism “is our defensive attitudinal tendency to view the values and norms of our culture as superior to other cultures, and we perceive our cultural ways of living as the most reasonable and proper ways to conduct our lives” (p. 157). In this context, some cultures are treated as superior to others. In their study of traditional Chinese culture and art communication in the digital era, researchers observed that treating cultures as ‘us’ and ‘them’ also affects individuals' evaluation of such cultures 34 . This indicates that the attitude of individuals toward a particular culture mediates their evaluation of other cultures. In a similar vein, a positive attitude toward other cultures affects the intercultural communication competence of individuals. This consistent view has been shared in prior studies 1 , 2 , 35 , 36 , 37 ). These findings suggest the manifestation of ethnocentrism across cultures. Accordingly, everyone is ethnocentric to a certain extent, as ethnocentrism manifests differently based upon individuals’ cultural and ecological education learning. This effect is thus a phenomenon where an individual’s own group is a point of reference for interpreting and evaluating members of other groups or cultures 6 , 38 , 39 .

Recently, it has been proposed that “ethnocentrism [is] the belief that one’s own culture is superior to all others. [Where one] view[s] the rest of the world through the narrow lens of one’s own culture” (p. 183) 40 . Additionally, ethnocentrism has mainly been used to study in-group and outgroup attitudes 41 , 42 . In previous research, scholars 2 have identified several attitudinal and behavioral characteristics of ethnocentric individuals. Regarding behavioral ethnocentrism, individuals develop good relations with ingroup members but have a sense of competition with outgroup members 2 . The findings have shown that Japanese students are more ethnocentric than American students 1 . Likewise, it was found that Pakistani university students are more ethnocentric than their Chinese counterparts 14 . Thus, ethnocentrism is a crucial barrier to effective communication. Pakistan and China have discrete political and media systems, cultural norms, and values. Building on past cultural models (i.e., Schwartz, Hofstede, and GLOBE), regardless of any similar clusters (collectivism/individualism), all nations have many dissimilarities, such as their orientation toward a specific phenomenon 43 . With respect to collectivism/individualism, Hofstede theoretically identified five dimensions of culture: ‘power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity/femininity and long W term/short W term orientation’. These cultural dimensions influence the communication of individuals in intercultural contexts along with ethnocentrism (ibid.). Therefore, we argue that both Pakistani and Chinese individuals, while collectivistic, are diversified based on their learned values, including ethnocentric phenomena; thus, in light of the literature, we hypothesize the following:

Pakistani students will score significantly higher on ethnocentrism than Chinese students.

Intercultural willingness to communicate

Communication is a basic human instinct and is central to human interaction; accordingly, it is inevitable for individuals to understand other individuals and perceive cultural variations. Today, humans live in a globalized and rather interdependent world, where the role of intercultural communication has drastically increased. It is an indubitable fact that cultural context influences intercultural communication 44 . Specifically, intercultural communication involves interactions and managing the differences between people from different cultures 45 , 46 . Intercultural communication also entails “respect for diversity”, which leads to entering into dialog with others and working for “harmony without uniformity”. Such acknowledgment of diversity in intercultural communication is made possible by caring for others’ cultures 47 . This requires justly understanding others’ cultures by utilizing intercultural communication, which can foster individuals to overcome cultural prejudices by engaging with diversity. To this end, the willingness to interact with others is central in ensuring such diversification.

It was found that the willingness to communicate is an “individual’s attitude” when engaging in communication with others 48 . In contrast, it has been suggested that the “intercultural willingness to communicate (IWTC) is defined as one’s predisposition to initiate intercultural communication encounters” (p. 400) 49 . Although the intercultural willingness to communicate (IWTC) seems related to the willingness to communicate (WTC), it is conceptually quite different from the latter 50 . The WTC is related to an individual’s inclination to initiate communication with others when the individual has the freedom to communicate. Put differently, the WTC refers to people’s communication tendencies with friends, colleagues, and strangers. In contrast, the IWTC relates to people’s willingness to be involved in communication encounters with people from different cultures, races, and backgrounds (ibid).

Additionally, ethnocentrism influences intercultural communication. In a study of Japanese and American participants, the more ethnocentric participants had a less empathetic understanding of other cultures, affecting how they interacted with other individuals 3 . Ethnocentrism is also different in various countries, and culture is the main factor that mediates it. In this context, Chinese college students have been shown to be less ethnocentric and have less IWTC than their American counterparts, who are more ethnocentric and have greater IWTC 12 . However, another study has shown that Romanian college students scored significantly higher on the ethnocentric scale and lower on the IWTC scale than their American counterparts 7 . Additionally, it has been reported that Korean college students have significantly lower scores on both the ethnocentric and the IWTC scales than American students 6 . In the Iranian context, it was concluded that ethnocentrism influences the intercultural willingness to communicate between both English and non-English major students 51 . In a more recent study, it was concluded that a higher level of ethnocentrism corresponds to a lower level of the intercultural willingness to communicate among Chinese and Indian undergraduate students studying at a private Malaysian university 52 .

Moreover, some studies of individualistic cultures have explored the IWTC among management students in New Zealand 21 . However, these studies have focused on the individualistic–collectivistic culture dichotomy. To our knowledge, there is no accessible study that has compared ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate among respondents from collectivistic cultures.

Although the Chinese and Pakistani cultures are similar to the Japanese and Korean cultures because both fall into the category of collectivistic cultures, both Korean and Japanese participants can vary in their degree of ethnocentrism. Although Chinese and Pakistani cultures are collectivistic, they have many dissimilarities. For example, the shared cultural attributes of individuals in both nations and their tendencies toward collectivism are quite different. For example, Pakistan is scored notably higher than China on the collectivism dimension by Hofstede 29 . Another difference, as narrated above, is their diverse shared cultural attributes, which imply many variances in a given attitude. Thus, there will be a different level of ethnocentrism among participants from these countries; consequently, this will affect the intercultural willingness to communicate. Despite their collectivistic cultures, Pakistan and China share many dissimilarities, ranging from their media systems and political systems to their cultural norms. There should be dissimilarities among people in terms of their willingness to communicate in different cultures due to their disparate norms, values, and communication practices 49 . Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

There is a difference in the level of their predisposition toward the intercultural willingness to communicate between Pakistani and Chinese students.

Influence of ethnocentrism on the predisposition toward the intercultural willingness to communicate

Culture and communication are mutually supportive; one’s level of ethnocentrism affects an individual’s intercultural willingness to communicate with people from other cultures. In this vein, “there is not one aspect of human life that is not touched and altered by culture” (p. 14) 53 . This discussion classifies culture into high-context and low-context. In the former, communication is very explicit, and its meanings are shared by society members; in the latter, communication is implicit, and detailed information, including context, is needed to delineate a message. Asian countries likely hold high-context cultural tendencies. High-context cultures are found in countries such as Korea, Japan, China, and Pakistan; on the other hand, low-context cultures are found in countries similar to the USA and Germany. For instance, individuals from low‐context cultures are more social and confrontation-avoiding than those from high-context cultures 54 . As a result, a greater extent of ethnocentrism is probable within high-context cultures and serves as a mechanism for deciphering cultural differences. Put differently, ethnocentrism affects our understanding of other cultures and influences people’s willingness to communicate with others.

Two communication predispositions, ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate, influence individuals’ intent toward intercultural interactions with people from different cultural backgrounds 6 . Thus, ethnocentrism leads to a lack of the intercultural willingness to communicate, which results in cultural conflict. In this context, knowledge of communication predispositions, such as ethnocentrism, helps identify the factors responsible for creating cultural conflict between two cultures 3 . Consequently, it also facilitates adopting effective communication strategies to address a conflict between individuals from two different cultures.

Although ethnocentrism is an individual disposition, it varies from culture to culture and is primarily contextual and cultural. In this regard, ethnocentrism has both negative and positive characteristics. Furthermore, the literature has suggested that members of collective cultures follow in-group authority, are eager to uphold the veracity of their in-group, and are reluctant to collaborate with people from outgroups 3 . Therefore, people in such cultures are expected to be more ethnocentric and to have less willingness to communicate. Moreover, ethnocentric people tend to foster supportive relationships with people belonging to their in-group while being contentious toward and possibly reluctant to cooperate with outgroup members (ibid). Therefore, ethnocentrism is largely considered an adverse trait, associated with intercultural communication. In this scenario, ethnocentrism stems from the ambiguity that can diminish the intercultural willingness to communicate 7 , 12 . For instance, individuals perceive a higher extent of ambiguity when communicating with outgroup members (e.g., strangers) than with members of their ingroup. Therefore, ethnocentrism-driven intercultural communicative anxiety can prevent individuals from communicating effectively. It can promote putting ‘patriotism’ before one’s own group interests and act as a communication barrier between people from different cultures and backgrounds 22 . Hence, ethnocentrism affects people’s attitudes toward one another in addition to their communication behaviors when they interact with one another in intercultural settings. In light of this literature, we therefore propose our third hypothesis:

There is a negative influence of ethnocentrism on the predisposition toward the intercultural willingness to communicate between Pakistani and Chinese students.

Influence of demographics on ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate

Past research has identified that regardless of cultural dissimilarities among cultures, demographic attributes are vital in predicting several predispositions and behavioral outcomes 55 . These demographic attributes and other sociocultural factors, such as norms or beliefs, provide an ecological environment to an individual in a given culture 56 . In turn, individuals learn and groom themselves within this ecological environment 28 , 43 . For example, people learn acceptable behaviors (i.e., norms), which are regulated by the social institutions available to them in such ecological settings. On the other hand, demographics also expose people to diverse ecological settings, allowing them to learn differently, even within a culture 57 . Hence, each demographic segment (men/women) of a particular culture has a different socialization based on the ecological resources provided to its members 58 . For example, Pakistani women are guided by their family system (ecological resource) concerning how to interact/communicate when encountering men. It is possible that these demographic attributes and ecological settings among diverse nations enable different viewpoints about different actions.

Accordingly, actions and attitudes, such as ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate, are certainly influenced by demographic attributes. Thus, demographic variables such as gender, past interactions with foreigners, and background (urban or rural) influence the attitude of respondents. For instance, recent studies 55 have reported that gender significantly influences ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness of respondents in intercultural settings. Likewise, a respondent’s background also plays a significant role in his or her ethnocentric score and, consequently, intercultural willingness to communicate. In addition, the experience of interactions with foreigners is another variable that affects ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate. The socioeconomic status and gender of a respondent influence his or her academic performance 59 . Therefore, in the context of this study, we assume that the gender, past experience of interactions with foreigners, and rural or urban background of a respondent influence his or her ethnocentrism and intercultural willingness to communicate. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Based on their demographic features such as gender, foreign interactions, and urban or rural background, there is a difference in the influence of ethnocentrism on the predisposition toward the IWTC between Pakistani and Chinese students.

Research design

Participants and data collection.

In this study, we used a cross-sectional design vis-à-vis the survey method to conduct a cross-cultural comparison of ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate between Pakistani and Chinese students. Two samples were purposively chosen from a leading university in Pakistan and in China. The aim of selecting a purposive sample from these two universities was to represent two well-known institutes of communication studies in each country. Students from all parts of these countries select these respective universities for majoring in communications. Thus, considering the nature and significance of this study, the researchers chose the purposive sample of students majoring in communication in both universities. In addition to other places for interaction, university life offers unique opportunities for students worldwide to interact with others 60 . Therefore, exploring ethnocentrism and the IWTC with university students seemed more practical and provided a heterogeneous sample. The students studying at these two universities are almost representative of the total student population majoring in communications. In total, 788 respondents completed the self-report survey questionnaire. After dropping 13 redundant responses, the sample consisted of 775 respondents. In this final sample, seven respondents did not report their gender, 33 did not mention their age, 21 omitted any information about traveling abroad, 27 did not give information regarding their residence, and 18 did not provide any information about their interactions with foreigners.

Pakistani sample

A self-report survey questionnaire with demographic variables was administered to Pakistani students enrolled in the communications program at the University of Punjab, Lahore-Pakistan. The survey was in the English language, and the survey instrument included the ethnocentrism and IWTC scales. The Pakistani sample consisted of 387 respondents, of which 167 were males and 217 were females. The respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 39 years (M = 22.86, SD = 2.3). Eighty-two students had traveled abroad, whereas 291 had never traveled abroad. Ninety-three students came from rural areas, and 282 came from urban backgrounds. Two hundred forty-one students reported that they had experienced interactions with foreigners, and 132 had not had any interactions with foreigners.

Chinese sample

The Chinese sample comprised 388 students—74 males and 310 females—enrolled in a communications program. The Chinese respondents’ ages ranged from 17 to 39 years (M = 21.40, SD = 2.8). One hundred seven students had traveled abroad, and 274 had never went abroad. Eighty-four reported a rural background, while 289 were from urban areas. Three hundred nineteen had experience interacting with foreigners, whereas 65 had never interacted with foreigners. For Chinese students, the English version of the revised Generalized Ethnocentrism Scale was translated into Chinese by two native doctoral students enrolled in the communications major. Any discrepancies in their translations were discussed and resolved.

Measurement of variables

To obtain their ethnocentrism score, participants were administered the 22-item revised Generalized Ethnocentrism Scale (GENE). Of its 22 items, 15 are scored to obtain an ethnocentrism score. This 22-item scale is a Likert-type response scale, ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5. The ethnocentrism scale has good internal consistency. The higher the score of respondents on the ethnocentrism scale, the higher their ethnocentrism is. For instance, for American and Romanian participants, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was previously reported to be 0.90 and 0.81, respectively 7 . In this study, the reliability of the 15-item scale for Chinese participants was 0.86 and 0.81 for Pakistani participants.

The IWTC scale was administered to respondents to measure their intercultural willingness to communicate 49 . The scale consisted of 12 items—half (six) were filler items and half were used to obtain a IWTC score. The IWTC scores ranged from 0 to 100%. A score of 0 means never willing to talk in an intercultural situation, and 100 means always willing to talk. The higher the score respondents have, the greater their intercultural willingness to communicate. For Chinese students, the English version of the IWTC Scale was translated into Chinese by two native doctoral students enrolled in the communications major. Any discrepancies in their translations were discussed and resolved. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values for the 6-item IWTC scale in a previous study for Korean and American samples were 0.83 and 0.91, respectively 6 . Likewise, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the 6-item intercultural-willingness-to-communicate scale was 0.90 for an American sample in a study where that of the Romanian participants was 0.81 7 . In the current study, the reliabilities of the 6-item IWTC scale for the Pakistani and Chinese samples were 0.83 and 0.91, respectively.

Demographic variables

Drawing on previous studies suggesting the potential role of demographic attributes in predicting ethnocentrism and the intercultural willingness to communicate, this study used three demographic attributes, namely, gender, past interaction with foreigners, and background (urban or rural).

Descriptive analysis

Initially, we performed descriptive analysis to test the normality of the data by observing the outliers and histograms that indicated a normal distribution of data across both samples. Table 1 illustrates the mean and standard deviation of the IWTC and ET separately for both samples. In addition, bivariate correlation analysis was performed, which revealed that all variables were significantly correlated across both samples (see Table 3 ). After normality testing, the study performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and validity

The study used the multigroup methodical approach, which suggests analyzing group differences 61 , 62 . These differences were examined by CFA for the identification of the invariance and factor loadings. This approach is useful for determining the measurement equivalence of how particular factors remain the same when explaining their parent variables in different cultural settings by constraining and unconstricting the paths. The results of the multigroup CFA reveal that the comparison of both models showed no significant differences, and thus, invariance was verified. Furthermore, the results of the CFA of the Chinese sample (n = 387) reveal that after deleting four items, the third, sixth, and seventh items of ethnocentrism and the second item of IWTC, all other items had loadings better than the suggested cutoff value (0.6) 63 , 64 . The recommended cutoff criterion for the goodness of fit measures is that the value of × 2/df should be within the range of 1 to 5. It is also recommended to attain at least five indices other than chi-square threshold values that may be employed separately to evaluate model fit. These include baselines and indices such as CFI, TLI and IFI and GFI ≥ 0. 90. For RMSEA and SRMR, values of 0.01, 0.05 and 0.08 indicate outstanding, decent and average fit, respectively, which imply a satisfactory fit. The measurement model solution revealed fit statistics for this research as follows: x 2 /df = 2.72; SRMR = 0.04; RMSEA = 0.043; GFI = 0.92; CFI = 0.95; IFI = 0.97 and TLI = 0.96.

Additionally, the models were tested for discriminant and convergent validity via the factor loadings. Using HTMT analysis, composite reliability and average variance extracted values were examined (see Table 2 ), and they met the threshold values suggested in the literature 63 , 65 . The loadings of the factors are given in Table 3 .

Hypothesis testing

Independent samples t tests were used to test three hypotheses (H1, H2, and H4). The independent samples t test was conducted to compare the ethnocentrism score for Pakistani and Chinese students; its results indicate that there is a significant difference between Pakistani (M = 38.49, SD = 6.8) and Chinese students (M = 35.73, SD = 5.5; t (773) = 6.17, p = 0.000, two-tailed). Similarly, the results of an independent samples t test comparing the intercultural willingness to communicate between the two cultures show that Chinese students have a higher intercultural willingness to communicate score (M = 299.41, SD = 136.24) than Pakistani students (M = 267.41, SD = 160.06, t (771) = − 2.99, p = 0.003, two-tailed). Moreover, an independent-sample t test between gender and the ethnocentric scores indicated that male participants (M = 38.00, SD = 6.34) are more ethnocentric than female participants (M = 36.66, SD = 6.35; t (766) = 2.73, p = 0.007, two-tailed). Likewise, an independent samples t test for the IWTC between the two samples indicated that male respondents (M = 259.89, SD = 143.06) have less intercultural willingness to communicate than females (M = 294.25, SD = 150.60, t (764) = − 2.98, p = 0.003, two-tailed). In other words, female participants are more willing to communicate with people from different cultures. When we compared within-sample differences for gender, we found that within Pakistan, there is no significant difference for the ethnocentrism score between males (M = 38.5, SD = 6.90) and females (M = 38.48), SD = 6.94, t (382), = 0.05, p = 0.96, two-tailed). However, within the Chinese sample, we found that males (M = 36.84, SD = 4.67) are more ethnocentric than females (M = 35.38, SD = 5.56, t (382) = 2.08, p = 0.04, two-tailed). For both samples, there were no significant differences in the IWTC between males and females. We did not find a significant difference in the ethnocentrism score for those 189 respondents who reported that they had traveled abroad (M = 36.44, SD = 6.39) or for the 565 who had not traveled abroad (M = 37.29, SD = 6.36, t (752) = − 1.95, p = 0.11, two-tailed). Similarly, no significant difference was found for the intercultural willingness to communicate among those who had traveled abroad (M = 298.86.SD = 145.9) and those who had not traveled abroad (280.60, SD = 150.69, t (750) = 1.45, p = 0.148 (two-tailed).

An independent samples t test for rural students showed no significant difference in the ethnocentrism score between rural (M = 37.16, SD = 6.32) and urban students M = 37.16, SD = 6.36, t (746) = 0.004, p = 0.99, two-tailed). Our independent samples t test for the IWTC of urban and rural students showed that urban students (M = 292.43, SD = 149.4) scored significantly higher than rural students (M = 263.44, SD = 145.84, t (744) = − 2.26, p = 0.02, two-tailed). Hence, urban students have a greater IWTC than their rural counterparts. When we compared those students who had experience interacting with foreigners to those who did not, we found a significant difference in ethnocentrism between the former (M = 36.36, SD = 6.11) and the latter (M = 39.20, SD = 6.64, t (755) = − 5.47, p = 0.000, two-tailed). However, there was no significant difference in the IWTC of students who had such interactions (M = 289.44, SD = 145.31) and those who did not (M = 269.09, SD = 156.89, t (753) = 1.65, p = 0.09 (two-tailed). An independent samples t test comparison between undergraduate and postgraduate students regarding their ethnocentrism score showed a significant difference. The undergraduate students (M = 37.7761, SD = 6.56) were more ethnocentric than the postgraduate students (M = 36.4241, SD = 6.13, t (773) = 2.96, p = 0.003 (two-tailed). For the IWTC analysis, there was also a significant difference. The undergraduates (M = 297.53, SD = 155.26) had a greater tendency toward the intercultural willingness to communicate than the postgraduate students (M = 269.01, SD = 141.75, t (771) = 2.66, p = 0.008 (two-tailed).

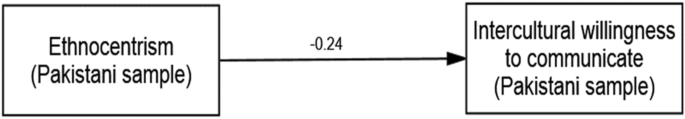

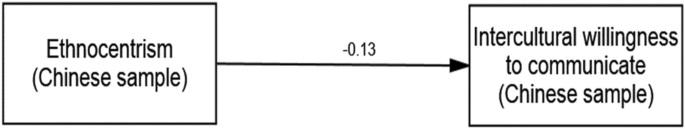

Moreover, to validate Hypothesis H3, we constructed two structural models for each country’s sample, i.e., one for China and one for Pakistan (see Fig. 1 ). This approach permitted us to detect the all-inclusive suitability of the proposed models for both samples and whether the data could validate the structural models 63 , 66 . The results of the commonly used fit indices revealed each model’s goodness of fit (Table 4 ).

Structural model (Pakistani sample).

The results for our test of H3 illustrate that ethnocentrism negatively affected the predisposition to intercultural competence (= − 0.24, p = 0.05) in the Pakistani sample and negatively affected the predisposition to intercultural competence (= − 0.13, p = 0.04) in the Chinese sample (see Figs. 1 , 2 ).

Structural model (Chinese sample).

However, these results supported H3 regarding the Pakistani sample due to its high score on the ethnocentrism scale. Hence, ethnocentrism more negatively affected the predisposition to intercultural competence among the Pakistani sample than among the Chinese sample.

Our first hypothesis (H1) posits that Pakistani students would have more ethnocentric scores than their Chinese counterparts. In this study, the Pakistani students scored significantly higher on the Ethnocentrism (GENE) scale than the Chinese students. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Our second hypothesis suggests that there is a difference between the predisposition to the intercultural willingness to communicate between Pakistani and Chinese students. This hypothesis is also supported. As Pakistani students are more ethnocentric, they consequently have less intercultural willingness to communicate than Chinese students, who are less ethnocentric and have a greater tendency toward the intercultural willingness to communicate. These findings validate the notion presented in existing cultural theories, such as Hofstede’s 29 , i.e., national culture drives individuals’ schemas of actions.

Similarly, a plausible explanation could be drawn from a national culture; that is, regardless of, e.g., a similar Asian context, there are certain cultural dissimilarities across cultures. For example, individuals living together amid shared cultural characteristics, such as norms, regulate their actions and tendencies to react in a situation 42 . Furthermore, the ecological environment where people socialize affects their behavioral patterns 56 . Likewise, the Chinese ethnic group has a higher education level. They are more self-centered and less cooperative, but they are also more diligent, tolerant and easy-going, respecting other ethnic minorities and cherishing family values 67 . Therefore, Chinese students are less ethnocentric and more willing to communicate in intercultural settings. In contrast, Pakistan is a diverse country, housing religious and ethnic minorities; there, the religious element is more dominant than the cultural element.

Consequently, Pakistani students are more ethnocentric and less interculturally eager to interact. One of the likely reasons for this greater ethnocentrism and lesser intercultural eagerness to engage in intercultural interactions is the religious socialization of the students. They are more reserved and less willing to engage in intercultural communication with people with another origin, culture, and values. The males in both samples are more ethnocentric than females and consequently less willing to engage in intercultural communication.

These findings support those of previous research 6 , 12 . These findings also support the rich body of communication studies, suggesting that females are more open and relation oriented during communications 68 . This research line can explain why females are less ethnocentric and more willing to communicate interculturally than their male counterparts. Thus, China’s rise as an economic player on the global stage and its subsequent integration with the world amid increasing cross-cultural exchanges provide Chinese students more opportunities for interaction and communication in different intercultural settings with people from different countries with different cultures and political and social values. Therefore, their lower level of ethnocentrism and greater intercultural willingness to communicate than Pakistani students makes sense and is not surprising.