- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- History by Period

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Regional and National History

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Language Evolution

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Browse content in Religion

- Christianity

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Company and Commercial Law

- Comparative Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Financial Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Legal System and Practice

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Anaesthetics

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Forensic Medicine

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Medical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Paediatrics

- Browse content in Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Physical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Browse content in Computing

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Environmental Sustainability

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Analysis

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Classical Mechanics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Browse content in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Health Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Human Evolution

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Schools Studies

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Environment

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Economic Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Security Studies

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Research and Information

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Browse content in Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Migration Studies

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Journals A to Z

- Books on Oxford Academic

High Impact Sociology Research

Oxford University Press publishes a portfolio of leading Sociology journals. To keep up to date with the latest research your peers are reading and citing, browse our selection of high impact articles on a diverse breadth of topics below.

All articles are freely available to read, download, and enjoy until May 2023.

- Community Development Journal

- European Sociological Review

- International Political Sociology

- Journal of Human Rights Practice

- Journal of Refugee Studies

- Refugee Survey Quarterly

- Social Forces

- Social Politics

- Social Problems

- Social Science Japan Journal

- Sociology of Religion

- The British Journal of Criminology

Community Development Journal

Covid-19 and community development Sue Kenny Community Development Journal , Volume 55, Issue 4, October 2020, Pages 699–703, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa020

Financialization, real estate and COVID-19 in the UK Grace Blakeley Community Development Journal , Volume 56, Issue 1, January 2021, Pages 79–99, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa056

Financial subordination and uneven financialization in 21st century Africa Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven, Kai Koddenbrock, Ndongo Samba Sylla Community Development Journal , Volume 56, Issue 1, January 2021, Pages 119–140, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa047

CDJ Editorial—What is this Covid-19 crisis? Rosie R. Meade Community Development Journal , Volume 55, Issue 3, July 2020, Pages 379–381, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa013

There’s a time and a place: temporal aspects of place-based stigma Alice Butler-Warke Community Development Journal , Volume 56, Issue 2, April 2021, Pages 203–219, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa040

European Sociological Review

Cohort Changes in the Level and Dispersion of Gender Ideology after German Reunification: Results from a Natural Experiment Christian Ebner, Michael Kühhirt, Philipp Lersch European Sociological Review , Volume 36, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 814–828, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa015

‘Cologne Changed Everything’—The Effect of Threatening Events on the Frequency and Distribution of Intergroup Conflict in Germany Arun Frey European Sociological Review , Volume 36, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 684–699, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa007

The Accumulation of Wealth in Marriage: Over-Time Change and Within-Couple Inequalities Nicole Kapelle, Philipp M. Lersch European Sociological Review , Volume 36, Issue 4, August 2020, Pages 580–593, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa006

Three Worlds of Vocational Education: Specialized and General Craftsmanship in France, Germany, and The Netherlands Jesper Rözer, Herman G. van de Werfhorst European Sociological Review , Volume 36, Issue 5, October 2020, Pages 780–797, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa025

Intergenerational Class Mobility among Men and Women in Europe: Gender Differences or Gender Similarities? Erzsébet Bukodi, Marii Paskov European Sociological Review , Volume 36, Issue 4, August 2020, Pages 495–512, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa001

International Political Sociology

Confronting the International Political Sociology of the New Right Rita Abrahamsen, Jean-François Drolet, Alexandra Gheciu, Karin Narita, Srdjan Vucetic, Michael Williams International Political Sociology , Volume 14, Issue 1, March 2020, Pages 94–107, https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olaa001

Collective Discussion: Toward Critical Approaches to Intelligence as a Social Phenomenon Hager Ben Jaffel, Alvina Hoffmann, Oliver Kearns, Sebastian Larsson International Political Sociology , Volume 14, Issue 3, September 2020, Pages 323–344, https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olaa015

The Cruel Optimism of Militarism: Feminist Curiosity, Affect, and Global Security Amanda Chisholm, Hanna Ketola International Political Sociology, Volume 14 , Issue 3, September 2020, Pages 270–285, https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olaa005

Feminist Commodity Activism: The New Political Economy of Feminist Protest Jemima Repo International Political Sociology , Volume 14, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 215–232, https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olz033

Affect and the Response to Terror: Commemoration and Communities of Sense Angharad Closs Stephens, Martin Coward, Samuel Merrill, Shanti Sumartojo International Political Sociology , Volume 15, Issue 1, March 2021, Pages 22–40, https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olaa020

Journal of Human Rights Practice

Africa, Prisons and COVID-19 Lukas M. Muntingh Journal of Human Rights Practice , Volume 12, Issue 2, July 2020, Pages 284–292, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huaa031

Pandemic Powers: Why Human Rights Organizations Should Not Lose Focus on Civil and Political Rights Eda Seyhan Journal of Human Rights Practice , Volume 12, Issue 2, July 2020, Pages 268–275, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huaa035

Affirming Radical Equality in the Context of COVID-19: Human Rights of Older People and People with Disabilities Supriya Akerkar Journal of Human Rights Practice , Volume 12, Issue 2, July 2020, Pages 276–283, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huaa032

Digital Dead Body Management (DDBM): Time to Think it Through Kristin Bergtora Sandvik Journal of Human Rights Practice, Volume 12 , Issue 2, July 2020, Pages 428–443, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huaa002

Legal Reasoning for Legitimation of Child Marriage in West Java: Accommodation of Local Norms at Islamic Courts and the Paradox of Child Protection Hoko Horii Journal of Human Rights Practice , Volume 12, Issue 3, November 2020, Pages 501–523, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huaa041

Journal of Refugee Studies

Refugee-Integration-Opportunity Structures: Shifting the Focus From Refugees to Context Jenny Phillimore Journal of Refugee Studies , Volume 34, Issue 2, June 2021, Pages 1946–1966, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa012

What Difference do Mayors Make? The Role of Municipal Authorities in Turkey and Lebanon's Response to Syrian Refugees Alexander Betts, Fulya MemiŞoĞlu, Ali Ali Journal of Refugee Studies , Volume 34, Issue 1, March 2021, Pages 491–519, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa011

Old Concepts Making New History: Refugee Self-reliance, Livelihoods and the ‘Refugee Entrepreneur’ Claudena Skran, Evan Easton-Calabria Journal of Refugee Studies , Volume 33, Issue 1, March 2020, Pages 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez061

Research with Refugees in Fragile Political Contexts: How Ethical Reflections Impact Methodological Choices Lea Müller-Funk Journal of Refugee Studies , Volume 34, Issue 2, June 2021, Pages 2308–2332, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa013

The Kalobeyei Settlement: A Self-reliance Model for Refugees? Alexander Betts, Naohiko Omata, Olivier Sterck Journal of Refugee Studies , Volume 33, Issue 1, March 2020, Pages 189–223, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez063

Migration Studies

International migration management in the age of artificial intelligence Ana Beduschi Migration Studies , Volume 9, Issue 3, September 2021, Pages 576–596, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa003

Migration as Adaptation? Kira Vinke, Jonas Bergmann, Julia Blocher, Himani Upadhyay, Roman Hoffmann Migration Studies , Volume 8, Issue 4, December 2020, Pages 626–634, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa029

Research on climate change and migration where are we and where are we going? Elizabeth Ferris Migration Studies , Volume 8, Issue 4, December 2020, Pages 612–625, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa028

The emotional journey of motherhood in migration. The case of Southern European mothers in Norway Raquel Herrero-Arias, Ragnhild Hollekim, Haldis Haukanes, Åse Vagli Migration Studies , Volume 9, Issue 3, September 2021, Pages 1230–1249, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa006

'I felt like the mountains were coming for me.'-The role of place attachment and local lifestyle opportunities for labour migrants' staying aspirations in two Norwegian rural municipalities Brit Lynnebakke Migration Studies , Volume 9, Issue 3, September 2021, Pages 759–782, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa002

Refugee Survey Quarterly

Refugee Rights Across Regions: A Comparative Overview of Legislative Good Practices in Latin America and the EU Luisa Feline Freier, Jean-Pierre Gauci Refugee Survey Quarterly , Volume 39, Issue 3, September 2020, Pages 321–362, https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdaa011

Syrian Refugee Migration, Transitions in Migrant Statuses and Future Scenarios of Syrian Mobility Marko Valenta, Jo Jakobsen, Drago Župarić-Iljić, Hariz Halilovich Refugee Survey Quarterly , Volume 39, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 153–176, https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdaa002

Ambiguous Encounters: Revisiting Foucault and Goffman at an Activation Programme for Asylum-seekers Katrine Syppli Kohl Refugee Survey Quarterly , Volume 39, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 177–206, https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdaa004

Behind the Scenes of South Africa’s Asylum Procedure: A Qualitative Study on Long-term Asylum-Seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo Liesbeth Schockaert, Emilie Venables, Maria-Teresa Gil-Bazo, Garret Barnwell, Rodd Gerstenhaber, Katherine Whitehouse Refugee Survey Quarterly , Volume 39, Issue 1, March 2020, Pages 26–55, https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdz018

Improving SOGI Asylum Adjudication: Putting Persecution Ahead of Identity Moira Dustin, Nuno Ferreira Refugee Survey Quarterly , Volume 40, Issue 3, September 2021, Pages 315–347, https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdab005

Social Forces

Paths toward the Same Form of Collective Action: Direct Social Action in Times of Crisis in Italy Lorenzo Bosi, Lorenzo Zamponi Social Forces , Volume 99, Issue 2, December 2020, Pages 847–869, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz160

Attitudes toward Refugees in Contemporary Europe: A Longitudinal Perspective on Cross-National Differences Christian S. Czymara Social Forces , Volume 99, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 1306–1333, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa055

Opiate of the Masses? Inequality, Religion, and Political Ideology in the United States Landon Schnabel Social Forces , Volume 99, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 979–1012, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa027

Re-examining Restructuring: Racialization, Religious Conservatism, and Political Leanings in Contemporary American Life John O’Brien, Eman Abdelhadi Social Forces , Volume 99, Issue 2, December 2020, Pages 474–503, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa029

Evidence from Field Experiments in Hiring Shows Substantial Additional Racial Discrimination after the Callback Lincoln Quillian, John J Lee, Mariana Oliver Social Forces , Volume 99, Issue 2, December 2020, Pages 732–759, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa026

Social Politics

Varieties of Gender Regimes Sylvia Walby Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society , Volume 27, Issue 3, Fall 2020, Pages 414–431, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa018

The Origins and Transformations of Conservative Gender Regimes in Germany and Japan Karen A. Shire, Kumiko Nemoto Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society , Volume 27, Issue 3, Fall 2020, Pages 432–448, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa017

Counteracting Challenges to Gender Equality in the Era of Anti-Gender Campaigns: Competing Gender Knowledges and Affective Solidarity Elżbieta Korolczuk Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society , Volume 27, Issue 4, Winter 2020, Pages 694–717, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa021

Gender, Violence, and Political Institutions: Struggles over Sexual Harassment in the European Parliament Valentine Berthet, Johanna Kantola Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society , Volume 28, Issue 1, Spring 2021, Pages 143–167, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa015

Gender Regime Change in Decentralized States: The Case of Spain Emanuela Lombardo, Alba Alonso Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society , Volume 27, Issue 3, Fall 2020, Pages 449–466, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa016

Social Problems

Technologies of Crime Prediction: The Reception of Algorithms in Policing and Criminal Courts Sarah Brayne, Angèle Christin Social Problems , Volume 68, Issue 3, August 2021, Pages 608–624, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa004

White Christian Nationalism and Relative Political Tolerance for Racists Joshua T. Davis, Samuel L. Perry Social Problems , Volume 68, Issue 3, August 2021, Pages 513–534, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa002

The Increasing Effect of Neighborhood Racial Composition on Housing Values, 1980-2015 Junia Howell, Elizabeth Korver-Glenn Social Problems , Volume 68, Issue 4, November 2021, Pages 1051–1071, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa033

Transition into Liminal Legality: DACA' Mixed Impacts on Education and Employment among Young Adult Immigrants in California Erin R. Hamilton, Caitlin Patler, Robin Savinar Social Problems , Volume 68, Issue 3, August 2021, Pages 675–695, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa016

Constructing Allyship and the Persistence of Inequality J. E. Sumerau, TehQuin D. Forbes, Eric Anthony Grollman, Lain A. B. Mathers Social Problems , Volume 68, Issue 2, May 2021, Pages 358–373, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa003

Social Science Japan Journal

Nuclear Restart Politics: How the ‘Nuclear Village’ Lost Policy Implementation Power Florentine Koppenborg Social Science Japan Journal , Volume 24, Issue 1, Winter 2021, Pages 115–135, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyaa046

Factors Affecting Household Disaster Preparedness Among Foreign Residents in Japan David Green, Matthew Linley, Justin Whitney, Yae Sano Social Science Japan Journal , Volume 24, Issue 1, Winter 2021, Pages 185–208, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyaa026

Climate Change Policy: Can New Actors Affect Japan's Policy-Making in the Paris Agreement Era? Yasuko Kameyama Social Science Japan Journal , Volume 24, Issue 1, Winter 2021, Pages 67–84, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyaa051

Japan Meets the Sharing Economy: Contending Frames Thomas G. Altura, Yuki Hashimoto, Sanford M. Jacoby, Kaoru Kanai, Kazuro Saguchi Social Science Japan Journal , Volume 24, Issue 1, Winter 2021, Pages 137–161, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyaa041

Administrative Measures Against Far-Right Protesters: An Example of Japan’s Social Control Ayaka Löschke Social Science Japan Journal , Volume 24, Issue 2, Summer 2021, Pages 289–309, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyab005

Sociology of Religion

Religion in the Age of Social Distancing: How COVID-19 Presents New Directions for Research Joseph O. Baker, Gerardo Martí, Ruth Braunstein, Andrew L Whitehead, Grace Yukich Sociology of Religion , Volume 81, Issue 4, Winter 2020, Pages 357–370, https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sraa039

Keep America Christian (and White): Christian Nationalism, Fear of Ethnoracial Outsiders, and Intention to Vote for Donald Trump in the 2020 Presidential Election Joseph O. Baker, Samuel L. Perry, Andrew L. Whitehead Sociology of Religion , Volume 81, Issue 3, Autumn 2020, Pages 272–293, https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sraa015

Formal or Functional? Traditional or Inclusive? Bible Translations as Markers of Religious Subcultures Samuel L. Perry, Joshua B. Grubbs Sociology of Religion , Volume 81, Issue 3, Autumn 2020, Pages 319–342, https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sraa003

Political Identity and Confidence in Science and Religion in the United States Timothy L. O’Brien, Shiri Noy Sociology of Religion , Volume 81, Issue 4, Winter 2020, Pages 439–461, https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sraa024

Religious Freedom and Local Conflict: Religious Buildings and Zoning Issues in the New York City Region, 1992–2017 Brian J. Miller Sociology of Religion , Volume 81, Issue 4, Winter 2020, Pages 462–484, https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sraa006

The British Journal of Criminology

Reporting Racist Hate Crime Victimization to the Police in the United States and the United Kingdom: A Cross-National Comparison Wesley Myers, Brendan Lantz The British Journal of Criminology , Volume 60, Issue 4, July 2020, Pages 1034–1055, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa008

Does Collective Efficacy Matter at the Micro Geographic Level?: Findings from a Study Of Street Segments David Weisburd, Clair White, Alese Wooditch The British Journal of Criminology , Volume 60, Issue 4, July 2020, Pages 873–891, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa007

Responses to Wildlife Crime in Post-Colonial Times. Who Fares Best? Ragnhild Aslaug Sollund, Siv Rebekka Runhovde The British Journal of Criminology , Volume 60, Issue 4, July 2020, Pages 1014–1033, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa005

‘Playing the Game’: Power, Authority and Procedural Justice in Interactions Between Police and Homeless People in London Arabella Kyprianides, Clifford Stott, Ben Bradford The British Journal of Criminology , Volume 61, Issue 3, May 2021, Pages 670–689, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa086

Live Facial Recognition: Trust and Legitimacy as Predictors of Public Support For Police Use of New Technology Ben Bradford, Julia A Yesberg, Jonathan Jackson, Paul Dawson The British Journal of Criminology , Volume 60, Issue 6, November 2020, Pages 1502–1522, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa032

Affiliations

- Copyright © 2024

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Sociology articles from across Nature Portfolio

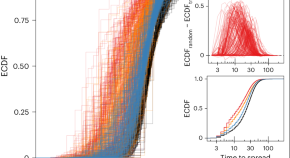

Long ties across networks accelerate the spread of social contagions

Long ties that bridge socially separate regions of networks are critical for the spread of contagions, such as innovations or adoptions of new norms. Contrary to previous thinking, long ties have now been found to accelerate social contagions, even for behaviours that involve the social reinforcement of adoption by network neighbours.

Latest Research and Reviews

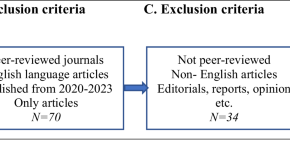

Early marriage of girls in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review

- Shah Md Atiqul Haq

- Mufti Nadimul Quamar Ahmed

- Khandaker Jafor Ahmed

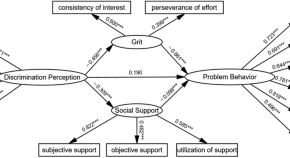

Discrimination perception and problem behaviors of left-behind children in China: the mediating effect of grit and social support

- Wangqian Fu

Neither right nor wrong? Ethics of collaboration in transformative research for sustainable futures

- Julia M. Wittmayer

- Ying-Syuan (Elaine) Huang

- Ana Vasques

Family communication patterns, self-efficacy, and adolescent online prosocial behavior: a moderated mediation model

- Weizhen Zhan

Effect of the contextual (community) level social trust on women’s empowerment: an instrumental variable analysis of 26 nations

- Alena Auchynnikava

- Nazim Habibov

Indigenous bodies, gender, and sexuality in the Jesuit Missions of South America (17th–18th centuries)

- Jean Tiago Baptista

- Tony Willian Boita

News and Comment

We urgently need a culture of multi-operationalization in psychological research

Analysis of different operationalizations shows that many scientific results may be an artifact of the operationalization process. A culture of multi-operationalization may be needed for psychological research to develop valid knowledge.

- Dino Carpentras

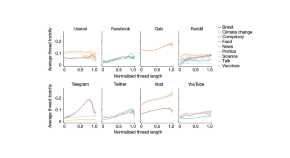

Long online discussions are consistently the most toxic

An ambitious investigation has analysed discourse on eight social-media platforms, covering a vast array of topics and spanning several decades. It reveals that online conversations increase in toxicity as they get longer — and that this behaviour persists despite shifts in platforms’ business models, technological advances and societal norms.

Using stakeholder network analysis to enhance the impact of participation in water governance

Citizen participation in water governance can improve the relevance, implementation, and effectiveness of public policies. However, participation can be expressed in a great diversity of forms, on a gradient ranging from mere public consultation to shared governance of natural resources. Positive outcomes ultimately depend on the conditions under which participation takes place, with key factors such as leadership, the degree of trust among stakeholders, and the interaction of public authorities with citizens. Social network analysis has been used to operationalize participatory processes, contributing to the identification of leaders, intersectoral integration, strategic planning, and conflict resolution. In this commentary, we analyze the potential and limitations of participation in water governance and illustrate it with the case of the Campina de Faro aquifer in southern Portugal. We propose that stakeholder network analysis is particularly useful for promoting decentralized decision-making and consensual water resources management. The delegation of power to different interest groups is a key process in the effectiveness of governance, which can be operationalized with network analysis techniques.

- Isidro Maya Jariego

How a tree-hugging protest transformed Indian environmentalism

Fifty years ago, a group of women from the villages of the Western Himalayas sparked Chipko, a green movement that remains relevant in the age of climate change.

- Seema Mundoli

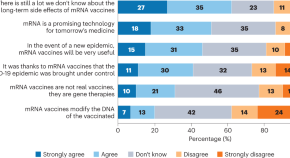

To understand mRNA vaccine hesitancy, stop calling the public anti-science

- Patrick Peretti-Watel

- Pierre Verger

- Jeremy K. Ward

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Social Theory Follow Following

- Political Sociology Follow Following

- Cultural Sociology Follow Following

- Sociological Theory Follow Following

- Sociology of Culture Follow Following

- Social Movements Follow Following

- Historical Sociology Follow Following

- Sociology of Knowledge Follow Following

- Critical Theory Follow Following

- Neoliberalism Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define and describe the scientific method.

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research.

- Describe the function and importance of an interpretive framework.

- Describe the differences in accuracy, reliability and validity in a research study.

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method and a scholarly interpretive perspective, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries, in families that have enlightened family members, and in education that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried and true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, and field research. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving ideas right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behavior.

However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of six prescribed steps that have been established over centuries of scientific scholarship.

Sociological research does not reduce knowledge to right or wrong facts. Results of studies tend to provide people with insights they did not have before—explanations of human behaviors and social practices and access to knowledge of other cultures, rituals and beliefs, or trends and attitudes.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of psychological well-being, community cohesiveness, range of vocation, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Are communities functioning smoothly? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might study vacation trends, healthy eating habits, neighborhood organizations, higher education patterns, games, parks, and exercise habits.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. They work outside of their own political or social agendas. This does not mean researchers do not have their own personalities, complete with preferences and opinions. But sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in collecting and analyzing data in research studies.

With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. They provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton 1963). Typically, the scientific method has 6 steps which are described below.

Step 1: Ask a Question or Find a Research Topic

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?”

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review , which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized.

To study crime, a researcher might also sort through existing data from the court system, police database, prison information, interviews with criminals, guards, wardens, etc. It’s important to examine this information in addition to existing research to determine how these resources might be used to fill holes in existing knowledge. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variables (IV) , which are the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV) , which is the effect , or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

In a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

Taking an example from Table 12.1, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying related two topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Step 4: Design and Conduct a Study

Researchers design studies to maximize reliability , which refers to how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced. Reliability increases the likelihood that what happens to one person will happen to all people in a group or what will happen in one situation will happen in another. Cooking is a science. When you follow a recipe and measure ingredients with a cooking tool, such as a measuring cup, the same results is obtained as long as the cook follows the same recipe and uses the same type of tool. The measuring cup introduces accuracy into the process. If a person uses a less accurate tool, such as their hand, to measure ingredients rather than a cup, the same result may not be replicated. Accurate tools and methods increase reliability.

Researchers also strive for validity , which refers to how well the study measures what it was designed to measure. To produce reliable and valid results, sociologists develop an operational definition , that is, they define each concept, or variable, in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept. By operationalizing the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner. Moreover, researchers can determine whether the experiment or method validly represent the phenomenon they intended to study.

A study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, might define “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” However, one researcher might define a “good” grade as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for “good.” For the results to be replicated and gain acceptance within the broader scientific community, researchers would have to use a standard operational definition. These definitions set limits and establish cut-off points that ensure consistency and replicability in a study.

We will explore research methods in greater detail in the next section of this chapter.

Step 5: Draw Conclusions

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, tabulate or categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss the implications of the results for the theory or policy solution that they were addressing. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, researchers may consider repeating the experiment or think of ways to improve their procedure.

However, even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, these results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

Sociologists carefully keep in mind how operational definitions and research designs impact the results as they draw conclusions. Consider the concept of “increase of crime,” which might be defined as the percent increase in crime from last week to this week, as in the study of Swedish crime discussed above. Yet the data used to evaluate “increase of crime” might be limited by many factors: who commits the crime, where the crimes are committed, or what type of crime is committed. If the data is gathered for “crimes committed in Houston, Texas in zip code 77021,” then it may not be generalizable to crimes committed in rural areas outside of major cities like Houston. If data is collected about vandalism, it may not be generalizable to assault.

Step 6: Report Results

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develops as the relationships between social phenomenon are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on empirical data and the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework . While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective , seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge or understanding about the human experience.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects including storytelling. This type of researcher learns through the process and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

Critical Sociology

Critical sociology focuses on deconstruction of existing sociological research and theory. Informed by the work of Karl Marx, scholars known collectively as the Frankfurt School proposed that social science, as much as any academic pursuit, is embedded in the system of power constituted by the set of class, caste, race, gender, and other relationships that exist in the society. Consequently, it cannot be treated as purely objective. Critical sociologists view theories, methods, and the conclusions as serving one of two purposes: they can either legitimate and rationalize systems of social power and oppression or liberate humans from inequality and restriction on human freedom. Deconstruction can involve data collection, but the analysis of this data is not empirical or positivist.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Open access

- Published: 22 August 2017

Social conditions of becoming homelessness: qualitative analysis of life stories of homeless peoples

- Mzwandile A. Mabhala ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1350-7065 1 , 3 ,

- Asmait Yohannes 2 &

- Mariska Griffith 1

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 16 , Article number: 150 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

66k Accesses

49 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

It is increasingly acknowledged that homelessness is a more complex social and public health phenomenon than the absence of a place to live. This view signifies a paradigm shift, from the definition of homelessness in terms of the absence of permanent accommodation, with its focus on pathways out of homelessness through the acquisition and maintenance of permanent housing, to understanding the social context of homelessness and social interventions to prevent it.

However, despite evidence of the association between homelessness and social factors, there is very little research that examines the wider social context within which homelessness occurs from the perspective of homeless people themselves. This study aims to examine the stories of homeless people to gain understanding of the social conditions under which homelessness occurs, in order to propose a theoretical explanation for it.

Twenty-six semi-structured interviews were conducted with homeless people in three centres for homeless people in Cheshire North West of England.

The analysis revealed that becoming homeless is a process characterised by a progressive waning of resilience capacity to cope with life challenges created by series of adverse incidents in one’s life. The data show that final stage in the process of becoming homeless is complete collapse of relationships with those close to them. Most prominent pattern of behaviours participants often describe as main causes of breakdown of their relationships are:

engaging in maladaptive behavioural lifestyle including taking drugs and/or excessive alcohol drinking

Being in trouble with people in authorities.

Homeless people describe the immediate behavioural causes of homelessness, however, the analysis revealed the social and economic conditions within which homelessness occurred. The participants’ descriptions of the social conditions in which were raised and their references to maladaptive behaviours which led to them becoming homeless, led us to conclude that they believe that their social condition affected their life chances: that these conditions were responsible for their low quality of social connections, poor educational attainment, insecure employment and other reduced life opportunities available to them.

It is increasingly acknowledged that homelessness is a more complex social and public health phenomenon than the absence of a place to live. This view signifies a paradigm shift, from the definition of homelessness in terms of the absence of permanent accommodation [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ], with its focus on pathways out of homelessness through the acquisition and maintenance of permanent housing [ 6 ], to understanding the social context of homelessness and social interventions to prevent it [ 6 ].

Several studies explain the link between social factors and homelessness [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. The most common social explanations centre on seven distinct domains of deprivation: income; employment; health and disability; education, skills and training; crime; barriers to housing and social support services; and living environment [ 11 ]. Of all forms, income deprivation has been reported as having the highest risk factors associated with homelessness [ 7 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]: studies indicate that people from the most deprived backgrounds are disproportionately represented amongst the homeless [ 7 , 13 ]. This population group experiences clusters of multiple adverse health, economic and social conditions such as alcohol and drug misuse, lack of affordable housing and crime [ 10 , 12 , 15 ]. Studies consistently show an association between risk of homelessness and clusters of poverty, low levels of education, unemployment or poor employment, and lack of social and community support [ 7 , 10 , 13 , 16 ].

Studies in different countries throughout the world have found that while the visible form of homelessness becomes evident when people reach adulthood, a large proportion of homeless people have had extreme social disadvantage and traumatic experiences in childhood including poverty, shortage of social housing stocks, disrupted schooling, lack of social and psychological support, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, neglect, dysfunctional family environments, and unstable family structures, all of which increase the likelihood of homelessness [ 10 , 13 , 14 ].

Furthermore, a large body of evidence suggests that people exposed to diverse social disadvantages at an early age are less likely to adapt successfully compared to people without such exposure [ 9 , 10 , 13 , 17 ], being more susceptible to adopting maladaptive coping behaviours such as theft, trading sex for money, and selling or using drugs and alcohol [ 7 , 9 , 18 , 19 ]. Studies show that these adverse childhood experiences tend to cluster together, and that the number of adverse experiences may be more predictive of negative adult outcomes than particular categories of events [ 17 , 20 ]. The evidence suggests that some clusters are more predictive of homelessness than others [ 7 , 12 ]: a cluster of childhood problems including mental health and behavioural disorders, poor school performance, a history of foster care, and disrupted family structure was most associated with adult criminal activities, adult substance use, unemployment and subsequent homelessness [ 12 , 17 , 21 ]. However, despite evidence of the association between homelessness and social factors, there is very little research that examines the wider social context within which homelessness occurs from the perspective of homeless people themselves.

This paper adopted Anderson and Christian’s [ 18 ] definition, which sees homelessness as a ‘function of gaining access to adequate, affordable housing, and any necessary social support needed to ensure the success of the tenancy’. Based on our synthesis of the evidence, this paper proposes that homelessness is a progressive process that begins at childhood and manifests itself at adulthood, one characterised by loss of the personal resources essential for successful adaptation. We adopted the definition of personal resources used by DeForge et al. ([ 7 ], p. 223), which is ‘those entities that either are centrally valued in their own right (e.g. self-esteem, close attachment, health and inner peace) or act as a means to obtain centrally valued ends (e.g. money, social support and credit)’. We propose that the new paradigm focusing on social explanations of homelessness has the potential to inform social interventions to reduce it.

In this study, we examine the stories of homeless people to gain understanding of the conditions under which homelessness occurs, in order to propose a theoretical explanation for it.

The design of this study was philosophically influenced by constructivist grounded theory (CGT). The aspect of CGT that made it appropriate for this study is its fundamental ontological belief in multiple realities constructed through the experience and understanding of different participants’ perspectives, and generated from their different demographic, social, cultural and political backgrounds [ 22 ]. The researchers’ resulting theoretical explanation constitutes their interpretation of the meanings that participants ascribe to their own situations and actions in their contexts [ 22 ].

The stages of data collection and analysis drew heavily on other variants of grounded theory, including those of Glaser [ 23 ] and Corbin and Strauss [ 24 ].

Setting and sampling strategy

The settings for this study were three centres for homeless people in two cities (Chester and Crewe) in Cheshire, UK. Two sampling strategies were used in this study: purposive and theoretical. The study started with purposive sampling and in-depth one-to-one semi-structured interviews with eight homeless people to generate themes for further exploration.

One of the main considerations for the recruitment strategy was to ensure that the process complies with the ethical principles of voluntary participation and equal opportunity to participate. To achieve this, an email was sent to all the known homeless centres in the Cheshire and Merseyside region, inviting them to participate. Three centres agreed to participate, all of them in Cheshire – two in Chester and one in Crewe.

Chester is the most affluent city in Cheshire and Merseyside, and therefore might not be expected to be considered for a homelessness project. The reasons for including it were: first, it was a natural choice, since the organisations that funded the project and the one that led the research project were based in Chester; second, despite its affluence, there is visible evidence of homelessness in the streets of Chester; and third, it has several local authority and charity-funded facilities for homeless people.

The principal investigator spent 1 day a week for 2 months in three participating centres, during that time oral presentation of study was given to all users of the centre and invited all the participants to participate and written participants information sheet was provided to those who wished to participate. During that time the principal investigator learned that the majority of homeless people that we were working with in Chester were not local. They told us that they came to Chester because there was no provision for homeless people in their former towns.

To help potential participants make a self-assessment of their suitability to participate without unfairly depriving others of the opportunity, participants information sheet outline criteria that potential participants had to meet: consistent with Economic and Social Research Council’s Research Ethics Guidebook [ 25 ], at the time of consenting to and commencing the interview, the participant must appear to be under no influence of alcohol or drugs, have a capacity to consent as stipulated in England and Wales Mental Capacity Act 2005 [ 26 ], be able to speak English, and be free from physical pain or discomfort.

As categories emerged from the data analysis, theoretical sampling was used to refine undeveloped categories in accordance with Strauss and Corbin’s [ 27 ] recommendations. In total 26 semi-structured interviews were carried out. Theoretical sampling involved review of memos or raw data, looking for data that might have been overlooked [ 27 , 28 ], and returning to key participants asking them to give more information on categories that seemed central to the emerging theory [ 27 , 28 ].

The sample comprised of 22 male and 4 female, the youndgest participant was 18 the eldest was 74 years, the mean age was 38.6 years. Table 1 illustrates participant’s education history, childhood living arrangements, brief participants family and social history, emotional and physical health, the onset of and trigger for homelessness.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Chester. The centre managers granted access once ethical approval had been obtained, and after their review of the study design and other research material, and of the participant information sheet which included a letter of invitation highlighting that participation was voluntary.

Data analysis

In this study data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously. Analysis drew on Glaser’s [ 23 ] grounded theory processes of open coding, use of the constant comparative method, and the iterative process of data collection and data analysis to develop theoretical explanation of homelessness.

The process began by reading the text line-by-line identifying and open coding the significant incidents in the data that required further investigation. The findings from the initial stage of analysis are published in Mabhala [ 29 ]. The the second stage the data were organised into three themes that were considered significant in becoming homeless (see Fig. 1 ):

Engaging in maladaptive behaviour

Being in trouble with the authorities.

Being in abusive environments.

Social explanation of becoming homeless. Legend: Fig. 1 illustrates the process of becoming homeless

The key questions that we asked as we continued to interrogate the data were: What category does this incident indicate? What is actually happening in the data? What is the main concern being faced by the participants? Interrogation of the data revealed that participants were describing the process of becoming homeless.

The comparative analysis involved three processes described by Glaser ([ 23 ], p. 58–60): each incident in the data was compared with incidents from both the same participant and other participants, looking for similarities and differences. Significant incidents were coded or given labels that represented what they stood for, and similarly coded or labeled when they were judged to be about the same topic, theme or concept.

After a period of interrogation of the data, it was decided that the two categories - destabilising behaviour, and waning ofcapacity for resilience were sufficiently conceptual to be used as theoretical categories around which subcategories could be grouped (Fig. 1 ).

Once the major categories had been developed, the next step consisted of a combination of theoretical comparison and theoretical sampling. The emerging categories were theoretically compared with the existing literature. Once this was achieved, the next step was filling in and refining the poorly defined categories. The process continued until theoretical sufficiency was achieved.

Figure 1 illustrates the process of becoming homeless. The analysis revealed that becoming homeless is a process characterised by a progressive waning of resilience created by a series of adverse incidents in one’s life. Amongst the frequently cited incidents were being in an abusive environment and losing a significant person in one’s life. However, being in an abusive environment emerged from this and previously published studies as a major theme; therefore, we decided to analyse it in more detail.

The data further show that the final stage in the process of becoming homeless is a complete collapse of relationships with those with whom they live. The most prominent behaviours described by the participants as being a main cause of breakdown are:

Engaging in maladaptive behaviour: substance misuse, alcoholism, self-harm and disruptive behaviours

Being in trouble with the authorities: theft, burglary, arson, criminal offenses and convictions

The interrogation of data in relation to the conditions within which these behaviours occurred revealed that participants believed that their social contexts influenced their life chance, their engagement with social institution such as education and social services and in turn their ability to acquire and maintain home. Our experiences have also shown that homeless people readily express the view that behavioural lifestyle factors such as substance misuse and engaging in criminal activities are the causes of becoming homeless. However, when we spent time talking about their lives within the context of their status as homeless people, we began to uncover incidents in their lives that appeared to have weakened their capacity to constructively engage in relationships, engage with social institutions to make use of social goods [ 29 , 30 , 31 ] and maturely deal with societal demands.

Being in abusive environments

Several participants explicitly stated that their childhood experiences and damage that occurred to them as children had major influences on their ability to negotiate their way through the education system, gain and sustain employment, make appropriate choices of social networks, and form and maintain healthy relationships as adults.

It appears that childhood experiences remain resonant in the minds of homeless participants, who perceive that these have had bearing on their homelessness. Their influence is best articulated in the extracts below. When participants were asked to tell their stories of what led to them becoming homeless, some of their opening lines were:

What basically happened, is that I had a childhood of so much persistent, consistent abuse from my mother and what was my stepfather. Literally consistent, we went around with my mother one Sunday where a friend had asked us to stay for dinner and mother took the invitation up because it saved her from getting off her ass basically and do anything. I came away from that dinner genuinely believing that the children in that house weren’t loved and cared for, because they were not being hit, there was no shouting, no door slamming. [Marco]

It appears that Marco internalised the incidents of abuse, characterised by shouting, door slamming and beating as normal behaviour. He goes on to intimate how the internalised abusive behaviour affected his interaction with his employers.

‘…but consistently being put down, consistently being told I was thick, I started taking jobs and having employers effing and blinding at me. One employer actually used a “c” word ending in “t” at me quite frequently and I thought it was acceptable, which obviously now I know it’s not. So I am taking on one job after another that, how can I put it? That no one else would do basically. I was so desperate to work and earn my own money. [Marco]

Similarly, David makes a connection between his childhood experience and his homelessness. When he was asked to tell his life story leading to becoming homeless, his opening line was:

I think it [homelessness] started off when I was a child. I was neglected by my mum. I was physically and mentally abused by my mum. I got put into foster care, when I left foster care I was put in the hostel, from there I turn into alcoholic. Then I was homeless all the time because I got kicked out of the hostels, because you are not allowed to drink in the hostel. [David]

David and Marco’s experiences are similar to those of many participants. The youngest participant in this study, Clarke, had fresh memories of his abusive environment under his stepdad:

I wouldn't want to go back home if I had a choice to, because before I got kicked out me stepdad was like hitting me. I wouldn't want to go back to put up with that again. [I didn't tell anyone] because I was scared of telling someone and that someone telling me stepdad that I've told other people. ‘[Be] cause he might have just started doing again because I told people. It might have gotten him into trouble. [Clarke]

In some cases, participants expressed the beliefs that their abusive experience not only deprived them life opportunities but also opportunities to have families of their own. As Tom and Marie explain:

We were getting done for child neglect because one of our child has a disorder that means she bruise very easily. They all our four kids into care, social workers said because we had a bad childhood ourselves because I was abused by my father as well, they felt that we will fail our children because we were failed by our parents. We weren’t given any chance [Tom and Marie]

Norma, described the removal of her child to care and her maladaptive behaviour of excessive alcohol use in the same context as her experience of sexual abuse by her father.

I had two little boys with me and got took off from me and put into care. I got sexually abused by my father when I was six. So we were put into care. He abused me when I was five and raped me when I was six. Then we went into care all of us I have four brothers and four sisters. My dad did eighteen months for sexually abusing me and my sister. I thought it was normal as well I thought that is what dads do [Norma]

The analysis of participants in this study appears to suggest that social condition one is raised influence the choice of social connections and life partner. Some participants who have had experience of abuse as children had partner who had similar experience as children Tom and Marie, Lee, David and his partners all had partners who experienced child abuse as children.

Tom and Marie is a couple we interviewed together. They met in hostel for homeless people they have got four children. All four children have been removed from them and placed into care. They sleep rough along the canal. They explained:

We have been together for seven years we had a house and children social services removed children from us, we fell within bedroom tax. …we received an eviction order …on the 26th and the eviction date was the 27th while we were in family court fighting for our children. …because of my mental health …they were refusing to help us.

Our children have been adopted now. The adoption was done without our permission we didn’t agree to it because we wanted our children home because we felt we were unfairly treated and I [Marie] was left out in all this and they pin it all on you [Tom] didn’t they yeah, my [Tom] history that I was in care didn’t help.

Tom went on to talk about the condition under which he was raised:

I was abandoned by my mother when I was 12 I was then put into care; I was placed with my dad when I was 13 who physically abused me then sent back to care. [Tom].

David’s story provides another example of how social condition one is raised influence the choice of social connections and life partner. David has two children from two different women, both women grew up in care. Lisa one of David’s child mother is a second generation of children in care, her mother was raised in care too.

I drink to deal with problems. As I say I’ve got two kids with my girlfriend Kyleigh, but I got another lad with Lisa, he was taken off me by social services and put on for adoption ten years ago and that really what started it; to deal with that. Basically, because I was young, and I had been in care and the way I had been treated by my mum. Basically laid on me in the same score as my mum and because his mum [Lisa] was in care as well. So they treated us like that, which was just wrong. [David]

In this study, most participants identified alcohol or drugs and crime as the cause of relationships breakdown. However, the language they used indicates that these were secondary reasons rather than primary reasons for their homelessness. The typical question that MA and MG asked the interview participants was “tell us how did you become homeless”? Typically, participants cited different maladaptive behaviours to explain how they became homeless.

Alvin’s story is typical of:

Basically I started off as a bricklayer, … when the recession hit, there was an abundance of bricklayers so the prices went down in the bricklaying so basically with me having two young children and the only breadwinner in the family... so I had to kinda look for factory work and so I managed to get a job… somewhere else…. It was shift work like four 12 hour days, four 12 hour nights and six [days] off and stuff like that, you know, real hard shifts. My shift was starting Friday night and I’ll do Friday night, Saturday night to Monday night and then I was off Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, but I’d treat that like me weekend you know because I’ve worked all weekend. Then… so I’d have a drink then and stuff like that, you know. 7 o’ clock on a Monday morning not really the time to be drinking, but I used to treat it like me weekend. So we argued, me and my ex-missus [wife], a little bit and in the end we split up so moved back to me mum's, but kept on with me job, I was at me mum’s for possibly about five years and but gradually the drinking got worse and worse, really bad. I was diagnosed with depression and anxiety. … I used to drink to get rid of the anxiety and also to numb the pain of the breakup of me marriage really, you know it wasn’t good, you know. One thing led to another and I just couldn’t stop me alcohol. I mean I’ve done drugs you know, I was into the rave scene and I’ve never done hard drugs like heroin or... I smoke cannabis and I use cocaine, and I used to go for a pint with me mates and that. It all came to a head about November/December time, you know it was like I either stop drinking or I had to move out of me mum's. I lost me job in the January through being over the limit in work from the night before uum so one thing led to another and I just had to leave. [Alvin]

Similarly, Gary identified alcohol as the main cause of his relationship breakdown. However, when one listens to the full story alcohol appears to be a manifestation of other issues, including financial insecurities and insecure attachment etc.

It [the process of becoming homeless] mainly started with the breakdown of the relationship with me partner. I was with her for 15 years and we always had somewhere to live but we didn't have kids till about 13 years into the relationship. The last two years when the kids come along, I had an injury to me ankle which stopped me from working. I was at home all day everyday. …I was drinking because I was bored. I started drinking a lot ‘cause I couldn't move bout the house. It was a really bad injury I had to me ankle. Um, and one day me and me partner were having this argument and I turned round and saw my little boy just stood there stiff as a board just staring, looking at us. And from that day on I just said to me partner that I'll move out, ‘cause I didn't want me little boy to be seeing this all the time. [Gary]

In both cases Gary and Alvin indicate that changes in their employment status created conditions that promoted alcohol dependency, though both explained that they drank alcohol before the changes in their employment status occurred and the breakdown of relationships. Both intimated that that their job commitment limited the amount of time available to drink alcohol. As Gary explained, it is the frequency and amount of alcohol drinking that changed as a result of change in their employment status:

I used to have a bit of a drink, but it wasn’t a problem because I used to get up in the morning and go out to work and enjoy a couple of beers every evening after a day’s work. Um, but then when I wasn't working I was drinking, and it just snowballed out, you know snowball effect, having four cans every evening and then it went from there. I was drinking more ‘cause I was depressed. I was very active before and then I became like non-active, not being able to do anything and in a lot of pain as well. [Gary]

Furthermore, although the participants claim that drinking alcohol was not a problem until their employment circumstances changed, one gets a sense that alcohol was partly responsible for creating conditions that resulted in the loss of their jobs. In Gary’s case, for example, alcohol increased his vulnerability to the assault and injuries that cost him his job:

I got assaulted, kicked down a flight of stairs. I landed on me back on the bottom of the stairs, but me heel hit the stairs as it was still going up if you know what I mean. Smashed me heel, fractured me heel… So, by the time I got to the hospital and they x-rayed it they wasn't even able to operate ‘cause it was in that many pieces, they weren't even able to pin it if you know what I mean. [Gary]

Alvin, of the other hand, explained that:

I lost my job in the January through being over the limit in work from the night before, uum so one thing led to another and I just had to leave. [Alvin]

In all cases participants appear to construct marriage breakdown as an exacerbating factor for their alcohol dependence. Danny, for example, constructed marriage breakdown as a condition that created his alcohol dependence and alcohol dependence as a cause of breakdown of his relationship with his parents. He explains:

I left school when I was 16. Straight away I got married, had children. I have three children and marriage was fine. Umm, I was married for 17 years. As the marriage broke up I turned to alcohol and it really, really got out of control. I moved in with my parents... It was unfair for them to put up with me; you know um in which I became... I ended up on the streets, this was about when I was 30, 31, something like that and ever since it's just been a real struggle to get some permanent accommodation. [Danny]

Danny goes on to explain: