We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Case studies in social work practice

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

cut off text tight binding and margin

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station36.cebu on November 19, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Case study exploring social group work practice principles and processes with adolescents

Files and links (2).

Cookie Preference Center

Your preferences, strictly necessary cookies.

As described in our Corporate Privacy Notice and Cookie Policy , we use cookies (including pixels or other similar technologies) on our websites, mobile applications and related products (the “services”). The types of cookies we use are described below.

These are cookies necessary for the services to function and are always active. They are usually only set in response to actions made by the user which amount to a request for services, such as setting privacy preferences, logging in, or filling in forms.

Cookie List

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 24 September 2018

A mixed methods case study exploring the impact of membership of a multi-activity, multicentre community group on social wellbeing of older adults

- Gabrielle Lindsay-Smith ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3864-1412 1 ,

- Grant O’Sullivan 1 ,

- Rochelle Eime 1 , 2 ,

- Jack Harvey 1 , 2 &

- Jannique G. Z. van Uffelen 1 , 3

BMC Geriatrics volume 18 , Article number: 226 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

70k Accesses

30 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Social wellbeing factors such as loneliness and social support have a major impact on the health of older adults and can contribute to physical and mental wellbeing. However, with increasing age, social contacts and social support typically decrease and levels of loneliness increase. Group social engagement appears to have additional benefits for the health of older adults compared to socialising individually with friends and family, but further research is required to confirm whether group activities can be beneficial for the social wellbeing of older adults.

This one-year longitudinal mixed methods study investigated the effect of joining a community group, offering a range of social and physical activities, on social wellbeing of adults with a mean age of 70. The study combined a quantitative survey assessing loneliness and social support ( n = 28; three time-points, analysed using linear mixed models) and a qualitative focus group study ( n = 11, analysed using thematic analysis) of members from Life Activities Clubs Victoria, Australia.

There was a significant reduction in loneliness ( p = 0.023) and a trend toward an increase in social support ( p = 0.056) in the first year after joining. The focus group confirmed these observations and suggested that social support may take longer than 1 year to develop. Focus groups also identified that group membership provided important opportunities for developing new and diverse social connections through shared interest and experience. These connections were key in improving the social wellbeing of members, especially in their sense of feeling supported or connected and less lonely. Participants agreed that increasing connections was especially beneficial following significant life events such as retirement, moving to a new house or partners becoming unwell.

Conclusions

Becoming a member of a community group offering social and physical activities may improve social wellbeing in older adults, especially following significant life events such as retirement or moving-house, where social network changes. These results indicate that ageing policy and strategies would benefit from encouraging long-term participation in social groups to assist in adapting to changes that occur in later life and optimise healthy ageing.

Peer Review reports

Ageing population and the need to age well

Between 2015 and 2050 it is predicted that globally the number of adults over the age of 60 will more than double [ 1 ]. Increasing age is associated with a greater risk of chronic illnesses such as cardio vascular disease and cancer [ 2 ] and reduced functional capacity [ 3 , 4 ]. Consequently, an ageing population will continue to place considerable pressure on the health care systems.

However, it is also important to consider the individuals themselves and self-perceived good health is very important for the individual wellbeing and life-satisfaction of older adults [ 5 ]. The terms “successful ageing” [ 6 ] and “healthy ageing” [ 5 ] have been used to define a broader concept of ageing well, which not only includes factors relating to medically defined health but also wellbeing. Unfortunately, there is no agreed definition for what exactly constitutes healthy or successful ageing, with studies using a range of definitions. A review of 28 quantitative studies found that successful ageing was defined differently in each, with the majority only considering measures of disability or physical functioning. Social and wellbeing factors were included in only a few of the studies [ 7 ].

In contrast, qualitative studies of older adults’ opinions on successful ageing have found that while good physical and mental health and maintaining physical activity levels are agreed to assist successful ageing, being independent or doing something of value, acceptance of ageing, life satisfaction, social connectedness or keeping socially active were of greater importance [ 8 , 9 , 10 ].

In light of these findings, the definition that is most inclusive is “healthy ageing” defined by the World Health Organisation as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability (defined as a combination of intrinsic capacity and physical and social environmental characteristics), that enables well-being in older age” (p28) [ 5 ].This definition, and those provided in the research of older adults’ perceptions of successful ageing, highlight social engagement and social support as important factors contributing to successful ageing, in addition to being important social determinants of health [ 11 , 12 ].

Social determinants of health, including loneliness and social support, are important predictors of physical, cognitive and mental health and wellbeing in adults [ 12 ] and older adults [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Loneliness is defined as a perception of an inadequacy in the quality or quantity of one’s social relationships [ 16 ]. Social support, has various definitions but generally it relates to social relationships that are reciprocal, accessible and reliable and provide any or a combination of supportive resources (e.g. emotional, information, practical) and can be measured as perceived or received support [ 17 ]. These types of social determinants differ from those related to inequality (health gap social determinants) and are sometimes referred to as ‘social cure’ social determinants [ 11 ]. They will be referred to as ‘social wellbeing’ outcome measures in this study.

Unfortunately, with advancing age, there is often diminishing social support, leading to social isolation and loneliness [ 18 , 19 ]. Large nationally representative studies of adults and older adults reported that social activity predicted maintenance or improvement of life satisfaction as well as physical activity levels [ 20 ], however older adults spent less time in social activity than middle age adults.

Social wellbeing and health

A number of longitudinal studies have found that social isolation for older adults is a significant predictor of mortality and institutionalisation [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. A meta-analysis by Holt-Lunstadt [ 12 ] reported that social determinants of health, including social integration and social support (including loneliness and lack of perceived social support) to be equal to, or a greater risk to mortality as common behavioural risk factors such as smoking, physical inactivity and obesity. Loneliness is independently associated with poor physical and mental health in the general population, and especially in older adults [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Adequate perceived social support has also been consistently associated with improved mental and physical health in both general and older adults [ 20 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. The mechanism suggested for this association is that social support buffers the negative impacts of stressful situations and life events [ 30 ]. The above research demonstrates the benefit of social engagement for older adults; in turn this highlights the importance of strategies that reduce loneliness and improve social support and social connectedness for older adults.

Socialising in groups seems to be especially important for the health and wellbeing of older adults who may be adjusting to significant life events [ 26 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. This is sometimes referred to as social engagement or social companionship [ 26 , 30 , 31 ]. It seems that the mechanism enabling such health benefits with group participation is through strengthening of social identification, which in turn increases social support [ 31 , 34 , 35 ]. Furthermore, involvement in community groups can be a sustainable strategy to reduce loneliness and increase social support in older adults, as they are generally low cost and run by volunteers [ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ].

Despite the demonstrated importance of social factors for successful ageing and the established risk associated with reduced social engagement as people age, few in-depth studies have longitudinally investigated the impact of community groups on social wellbeing. For example, a non-significant increase in social support and reduction in depression was found in a year-long randomised controlled trial conducted in senior centres in Norway with lonely older adults in poor physical and mental health [ 37 ]. Some qualitative studies have reported that community groups and senior centres can contribute to fun and socialisation for older adults, however social wellbeing was not the primary focus of the studies [ 38 , 40 , 41 ]. Given that social wellbeing is a broad and important area for the health and quality of life in older adults, an in-depth study is warranted to understand how it can be maximised in older adults. This mixed methods case study of an existing community aims to: i) examine whether loneliness and social support of new members of Life Activities Clubs (LACs) changes in the year after joining and ii) conduct an in-depth exploration of how social wellbeing changes in new and longer-term members of LACs.

A mixed methods study was chosen as the design for this research to enable an in-depth exploration of how loneliness and social support may change as a result of joining a community group. A case study was conducted using a concurrent mixed-methods design, with a qualitative component giving context to the quantitative results. Where the survey focused on the impact of group membership on social support and loneliness, the focus groups were an open discussion of the benefits in the lived context of LAC membership. The synthesis of the two sections of the study was undertaken at the time of interpretation of the results [ 42 ].

The two parts of our study were as follows:

a longitudinal survey (three time points over 1 year: baseline, 6 and 12 months). This part of the study formed the quantitative results;

a focus group study of members of the same organisation (qualitative).

Ethics approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Victoria University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE14–071 [survey] and HRE15–291 [focus groups]) All participants provided informed consent to partake in the study prior to undertaking the first survey or focus group.

Setting and participants

Life activities clubs victoria.

Life Activities Clubs Victoria (LACVI) is a large not-for-profit group with 23 independently run Life Activities Clubs (LACs) based in both rural and metropolitan Victoria. It has approximately 4000 members. The organisation was established to assist in providing physical, social and recreational activities as well as education and motivational support to older adults managing significant change in their lives, especially retirement.

Eighteen out of 23 LAC clubs agreed to take part in the survey study. During the sampling period from May 2014 to December 2016, new members from the participating clubs were given information about the study and invited to take part. Invitations took place in the form of flyers distributed with new membership material.

Inclusion/ exclusion criteria

Community-dwelling older adults who self-reported that they could walk at least 100 m and who were new members to LACVI and able to complete a survey in English were eligible to participate. New members were defined as people who had never been members of LACVI or who had not been members in the last 2 years.

To ensure that the cohort of participants were of a similar functional level, people with significant health problems limiting them from being able to walk 100 m were excluded from participating in the study.

Once informed consent was received, the participants were invited to complete a self-report survey in either paper or online format (depending on preference). This first survey comprised the baseline data and the same survey was completed 6 months and 12 months after this initial time point. Participants were sent reminders if they had not completed each survey more than 2 weeks after each was delivered and then again 1 week later.

Focus groups

Two focus groups (FGs) were conducted with new and longer-term members of LACs. The first FG ( n = 6) consisted of members who undertook physical activity in their LAC (e.g. walking groups, tennis, cycling). The second FG ( n = 5) consisted of members who took part in activities with a non-physical activity (PA) focus (e.g. book groups, social groups, craft or cultural groups). LACs offer both social and physical activities and it was important to the study to capture both types of groups, but they were kept separate to assist participants in feeling a sense of commonality with other members and improving group dynamic and participation in the discussions [ 43 ]. Of the people who participated in the longitudinal survey study, seven also participated in the FGs.

The FG interviews were facilitated by one researcher (GLS) and notes around non-verbal communication, moments of divergence and convergence amongst group members, and other notable items were taken by a second researcher (GOS). Both researchers wrote additional notes after the focus groups and these were used in the analysis of themes. Focus groups were recorded and later transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist, including identification of each participant speaking. One researcher (GLS) reviewed each transcription to check for any errors and made any required modifications before importing the transcriptions into NVivo for analysis. The transcriber identified each focus group participant so themes for individuals or other age or gender specific trends could be identified.

Dependent variables

- Social support

Social support was assessed using the Duke–UNC Functional Social support questionnaire [ 44 ]. This scale specifically measures participant perceived functional social support in two areas; i) confidant support (5 questions; e.g. chances to talk to others) and ii) affective support (3 questions; e.g. people who care about them). Participants rated each component of support on a 5-item likert scale between ‘much less than I would like’ (1 point) to ‘as much as I would like’ (5 points). The total score used for analysis was the mean of the eight scores (low social support = 1, maximum social support = 5). Construct validity, concurrent validity and discriminant validity are acceptable for confidant and affective support items in the survey in the general population [ 44 ].

Loneliness was measured using the de Jong Gierveld and UCLA-3 item loneliness scales developed for use in many populations including older adults [ 45 ]. The 11-item de Jong Gierveld loneliness scale (DJG loneliness) [ 46 ] is a multi-dimensional measure of loneliness and contains five positively worded and six negatively worded items. The items fall into four subscales; feelings of severe loneliness, feelings connected with specific problem situations, missing companionship, feelings of belongingness. The total score is the sum of the items scores (i.e. 11–55): 11 is low loneliness and 55 is severe loneliness. Self-administered versions of this scale have good internal consistency (> = 0.8) and inter-item homogeneity and person scalability that is as good or better than when conducted as face-to face interviews. The validity and reliability for the scale is adequate [ 47 ]. The UCLA 3-item loneliness scale consists of three questions about how often participants feel they lack companionship, feel left out and feel isolated. The responses are given on a three-point scale ranging from hardly ever (1) to often (3). The final score is the sum of these three items with the range being from lowest loneliness (3) to highest loneliness (9). Reliability of the scale is good, (alpha = 0.72) as are discriminant validity and internal consistency [ 48 ]. The scale is commonly used to measure loneliness with older adults ([ 49 ] – review), [ 50 , 51 ].

Sociodemographic variables

The following sociodemographic characteristics were collected in both the survey and the focus groups: age, sex, highest level of education, main life occupation [ 52 ], current employment, ability to manage on income available, present marital status, country of birth, area of residence [ 53 ]. They are categorised as indicated in Table 2 .

Health variables

The following health variables were collected: Self-rated general health (from SF-12) [ 54 ] and Functional health (ability to walk 100 m- formed part of the inclusion criteria) [ 55 ]. See Table 2 for details about the categories of these variables.

The effects of becoming a member on quantitative outcome variables (i.e. Social support, DJG loneliness and UCLA loneliness) were analysed using linear mixed models (LMM). LMM enabled testing for the presence of intra-subject random effects, or equivalently, correlation of subjects’ measures over time (baseline, 6-months and 12 months). Three correlation structures were examined: independence (no correlation), compound symmetry (constant correlation of each subjects’ measures over the three time points) and autoregressive (correlation diminishing with increase in spacing in time). The best fitting correlation structure was compound symmetry; this is equivalent to a random intercept component for each subject. The LMM incorporated longitudinal trends over time, with adjustment for age as a potential confounder. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for windows (v24).

UCLA loneliness and social support residuals were not normally distributed and these scales were Log10 transformed for statistical analysis.

Analyses were all adjusted for age, group attendance (calculated as average attendance at 6 and 12 months) and employment status at baseline (Full-time, Part-time, not working).

Focus group transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis [ 56 , 57 ], a flexible qualitative methodology that can be used with a variety of epistemologies, approaches and analysis methods [ 56 ]. The transcribed data were analysed using a combination of theoretical and inductive thematic analysis [ 56 ]. It was theorised that membership in a LAC would assist with social factors relating to healthy ageing [ 5 ], possibly through a social identity pathway [ 58 ], although we wanted to explore this. Semantic themes were drawn from these codes in order to conduct a pragmatic evaluation of the LACVI programs [ 56 ]. Analytic rigour in the qualitative analysis was ensured through source and analyst triangulation. Transcriptions were compared to notes taken during the focus groups by the researchers (GOS and GLS). In addition, Initial coding and themes (by GLS) were checked by a second researcher (GOS) and any disagreements regarding coding and themes were discussed prior to finalisation of codes and themes [ 57 ].

Sociodemographic and health characteristics of the 28 participants who completed the survey study are reported in Table 1 . The mean age of the participants was 66.9 and 75% were female. These demographics are representative of the entire LACVI membership. Education levels varied, with 21% being university educated, and the remainder completing high school or technical certificates. Two thirds of participants were not married. Some sociodemographic characteristics changed slightly at 6 and 12 months, mainly employment (18% in paid employment at baseline and 11% at 12-months) and ability to manage on income (36% reporting trouble managing on their income at baseline and 46% at 12 months). Almost 90% of the participants described themselves as being in good-excellent health.

Types of activities

There were a variety of types of activities that participants took part in: physical activities such as walking groups ( n = 7), table tennis ( n = 5), dancing class ( n = 2), exercise class ( n = 1), bowls ( n = 2), golf ( n = 3), cycling groups ( n = 1) and non-physical leisure activities such as art and literature groups ( n = 5), craft groups ( n = 5), entertainment groups ( n = 12), food/dine out groups ( n = 18) and other sedentary leisure activities (e.g. mah jong, cards),( n = 4). A number of people took part in more than one activity.

Frequency of attendance at LACVI and changes in social wellbeing

At six and 12 months, participants indicated how many times in the last month they attended different types of activities at their LAC. Most participants maintained the same frequency of participation over both time points. Only four people participated more frequently at 12 than at 6 months and nine reduced participation levels. The latter group included predominantly those who reduced from more than two times per week at 6 months to 2×/week at 6 months to one to two times per week ( n = 5) or less than one time per week ( n = 2) at 12 months. Average weekly club attendance at six and 12 months was included as a covariate in the statistical model.

Outcome measures

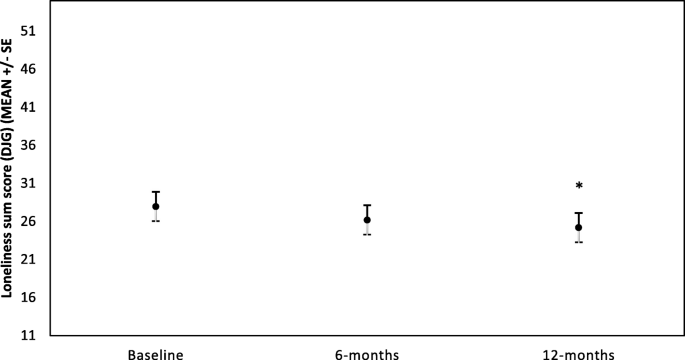

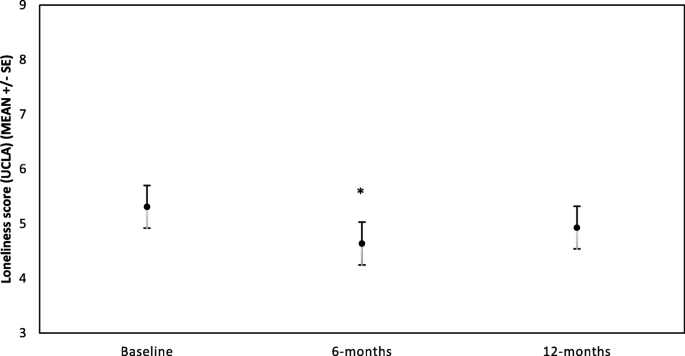

Overall, participants reported moderate social support and loneliness levels at baseline (See Table 2 ). Loneliness, as measured by both scales, reduced significantly over time. There was a significant effect of time on the DJG loneliness scores (F (2, 52) = 3.83, p = 0.028), with Post-Hoc analysis indicating a reduction in DJG loneliness between baseline and 12 months ( p = 0.008). UCLA loneliness scores (transformed variable) also changed significantly over time (F (2, 52) = 4.08, p = 0.023). Post hoc tests indicated a reduction in UCLA loneliness between baseline and 6 months ( p = 0.007). There was a small non-significant increase in social support (F (2, 53) =2.88, p = 0.065) during the first year of membership (see Table 2 and Figs. 1 and 2 ).

DJG loneliness for all participants over first year of membership at LAC club ( n = 28).

*Represents significant difference compared to baseline ( p < 0.01)

UCLA loneliness score for all participants over first year of membership at LAC club ( n = 28).

*Indicates log values of the variable at 6-months were significantly different from baseline ( p < 0.01)

In total, 11 participants attended the two focus groups, six people who participated in PA clubs (four women) and five who participated in social clubs (all women). All focus group participants were either retired ( n = 9) or semi-retired ( n = 2). The mean age of participants was 67 years (see Table 2 for further details). Most of the participants (82%) had been members of a LAC for less than 2 years and two females in the social group had been members of LAC clubs for 5 and 10 years respectively.

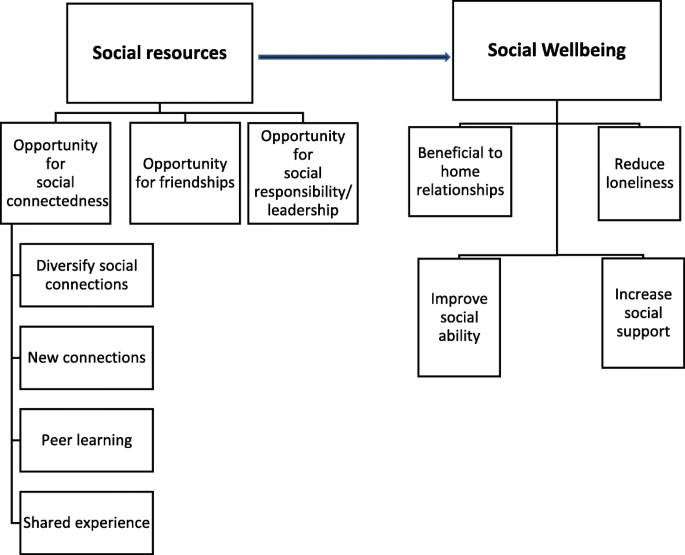

Analysis of the focus group transcripts identified two themes relating to social benefits of group participation; i) Social resources and ii) Social wellbeing (see Fig. 3 ). Group discussion suggested that membership of a LAC provides access to more social resources through greater and diverse social contact and opportunity. It is through this improvement in social resources that social wellbeing may improve.

Themes arising from focus group discussion around the benefits of LAC membership

Social resources

The social resources theme referred to an increase in the availability and variety of social connections that resulted from becoming a member of a LAC. The social nature of the groups enabled an expansion and diversification of members’ social network and improved their sense of social connectedness. There was widespread agreement in both the focus groups that significant life events, especially retirement, illness or death of spouse and moving house changes one’s social resources. Membership of the LAC had benefits especially at these times and these events were often motivators to join such a club. Most participants found that their social resources declined after retirement and even felt that they were grieving for the loss of their work.

“ I just saw work as a collection of, um, colleagues as opposed to friends. I had a few good friends there. Most were simply colleagues or acquaintances …. [interviewer- Mmm.] ..Okay, you’d talk to them every day. You’d chatter in the kitchen, oh, pass banter back and forth when things are busy or quiet, but... Um, in terms of a friendship with those people, like going to their home, getting to know them, doing other things with them, very few. But what I did miss was the interaction with other people. It had simply gone….. But, yeah, look, that, the, yeah, that intervening period was, oh, a couple of months. That was a bit tough…. But in that time the people in LAC and the people in U3A…. And the other dance group just drew me into more things. Got to know more people. So once again, yeah, reasonable group of acquaintances.” (Male, PAFG)

Group members indicated general agreement with these two responses, however one female found she had a greater social life following retirement due to the busy nature of her job.

Within the social resources theme, three subthemes were identified, i) Opportunity for social connectedness, ii) Opportunity for friendships, and iii) Opportunity for social responsibility/leadership . Interestingly, these subthemes were additional to the information gathered in the survey. This emphasises the power of the inductive nature of the qualitative exploration employed in the focus groups to broaden the knowledge in this area.

The most discussed and expanded subtheme in both focus groups was Opportunity for social connectedness , which arose through developing new connections, diversifying social connections, sharing interests and experiences with others and peer learning. Participants in both focus groups stated that being a member of LAC facilitated their socialising and connecting with others to share ideas, skills and to do activities with, which was especially important through times of significant life events. Furthermore, participants in each of the focus groups valued developing diverse connections:

“ Yeah, I think, as I said, I finished up work and I, and I had more time for wa-, walking. So I think a, in meeting, in going to this group which, I saw this group of women but then someone introduced me to them. They were just meeting, just meeting a new different set of people, you know? As I said, my work people and these were just a whole different group of women, mainly women. There’s not many men. [Interviewer: Yes.]….. Although our leader is a man, which is ironic and is about, this man out in front and there’s about 20 women behind him, but, um, so yeah, and people from different walks of life and different nationalities there which I never knew in my work life, so yeah. That’s been great. So from that goes on other things, you know, you might, uh, other activities and, yeah, people for coffee and go to the pictures or something, yeah. That’s great.” (Female, PAFG)

Simply making new connections was the most widely discussed aspect related to the opportunity for social connectedness subtheme, with all participants agreeing that this was an important benefit of participation in LAC groups.

“Well, my experience is very similar to everybody else’s…….: I, I went from having no social life to a social life once I joined a group.” (Female, PAFG)

There was agreement in both focus groups that these initial new connections made at a LAC are strengthened through development of deeper personal connections with others who have similar demographics and who are interested in the same activities. This concurs with the Social Identity Theory [ 58 ] discussed previously.

“and I was walking around the lake in Ballarat, like wandering on my own. I thought, This is ridiculous. I mean, you’ve met all those groups of women coming the opposite way, so I found out what it was all about, so I joined, yeah. So that’s how I got into that.[ Interviewer: Yeah.] Basically sick of walking round the lake on my own. [Interviewer: Yeah, yeah.] So that’s great. It’s very social and they have coffee afterwards which is good.” (female, PAFG)

The subtheme Opportunity for development of friendships describes how, for some people, a number of LAC members have progressed from being just initial social connections to an established friendship. This signifies the strength of the connections that may potentially develop through LAC membership. Some participants from each group mentioned friendships developing, with slightly more discussion of this seen in the social group.

“we all have a good old chat, you know, and, and it’s all about friendship as well.” (female, SocialFG)

The subtheme Opportunity for social responsibility or leadership was mentioned by two people in the active group, however it was not brought up in the social group. This opportunity for leadership is linked with the development of a group identity and desiring to contribute meaningfully to a valued group.

“with our riding group, um, you, a leader for probably two rides a year so you’ve gotta prepare for it, so some of them do reccie rides themselves, so, um, and also every, uh, so that’s something that’s, uh, a responsibility.” (male, PAFG)

Social wellbeing

The social resources described above seem to contribute to a number of social, wellbeing outcomes for participants. The sub themes identified for Social wellbeing were , i) Increased social support, ii) Reduced loneliness, iii) Improved home relationships and iv) Improved social skills.

Increased social support

Social support was measured quantitatively in the survey (no significant change over time for new members) and identified as a benefit of LAC membership during the focus group discussions. However, only one of the members of the active group mentioned social support directly.

‘it’s nice to be able to pick up the phone and share your problem with somebody else, and that’s come about through LAC. ……‘Cos before that it was through, with my family (female, PAFG)

There was some agreement amongst participants of the PA group that they felt this kind of support may develop in time but most of them had been members for less than 2 years.

“[Interviewer: Yeah. Does anyone else have that experience? (relating to above quote)]” There is one lady but she’s actually the one that I joined with anyway. [Interviewer: Okay.] But I, I feel there are others that are definitely getting towards that stage. It’s still going quite early days. (female1, PAFG) [Interviewer: I guess it’s quite early for some of you, yeah.] “yeah” (female 2, PAFG)

Social support through sharing of skills was mentioned by one participant in the social group also, with agreement indicated by most of the others in the social focus group.

Discussion in the focus groups also touched on the subthemes Reduced loneliness and Improved home relationships, which were each mentioned by one person. And focus groups also felt that group membership Improved social skills through opening up and becoming more approachable (male, PAFG) or enabling them to become more accepting of others’ who are different (general agreement in Social FG).

This case study integrated results from a one-year longitudinal survey study and focus group discussions to gather rich information regarding the potential changes in social wellbeing that older adults may experience when joining community organisations offering group activities. The findings from this study indicate that becoming a member of such a community organisation can be associated with a range of social benefits for older adults, particularly related to reducing loneliness and maintaining social connections.

Joining a LAC was associated with a reduction in loneliness over 1 year. This finding is in line with past group-intervention studies where social activity groups were found to assist in reducing loneliness and social isolation [ 49 ]. This systematic review highlighted that the majority of the literature explored the effectiveness of group activity interventions for reducing severe loneliness or loneliness in clinical populations [ 49 ]. The present study extends this research to the general older adult population who are not specifically lonely and reported to be of good general health, rather than a clinical focus. Our findings are in contrast to results from an evaluation of a community capacity-building program aimed at reducing social isolation in older adults in rural Australia [ 59 ]. That program did not successfully reduce loneliness or improve social support. The lack of change from pre- to post-program in that study was reasoned to be due to sampling error, unstandardised data collection, and changes in sample characteristics across the programs [ 59 ]. Qualitative assessment of the same program [ 59 ] did however suggest that participants felt it was successful in reducing social isolation, which does support our findings.

Changes in loneliness were not a main discussion point of the qualitative component of the current study, however some participants did express that they felt less lonely since joining LACVI and all felt they had become more connected with others. This is not so much of a contrast in results as a potential situational issue. The lack of discussion of loneliness may have been linked to the common social stigma around experiencing loneliness outside certain accepted circumstances (e.g. widowhood), which may lead to underreporting in front of others [ 45 ].

Overall, both components of the study suggest that becoming a member of an activity group may be associated with reductions in loneliness, or at least a greater sense of social connectedness. In addition to the social nature of the groups and increased opportunity for social connections, another possible link between group activity and reduced loneliness is an increased opportunity for time out of home. Previous research has found that more time away from home in an average day is associated with lower loneliness in older adults [ 60 ]. Given the significant health and social problems that are related to loneliness and social isolation [ 13 , 14 , 15 ], the importance of group involvement for newly retired adults to prevent loneliness should be advocated.

In line with a significant reduction in loneliness, there was also a trend ( p = 0.056) toward an increase in social support from baseline to 12 months in the survey study. Whilst suggestive of a change, it is far less conclusive than the findings for loneliness. There are a number of possible explanations for the lack of statistically significant change in this variable over the course of the study. The first is the small sample size, which would reduce the statistical power of the study. It may be that larger studies are required to observe changes in social support, which are possibly only subtle over the course of 1 year. This idea is supported by a year-long randomised controlled trial with 90 mildly-depressed older adults who attended senior citizen’s club in Norway [ 37 ]. The study failed to see any change in general social support in the intervention group compared to the control over 1 year. Additional analysis in that study suggested that people who attended the intervention groups more often, tended to have greater increases in SS ( p = 0.08). The researchers stated that the study suffered from significant drop-out rates and low power as a result. In this way, it was similar to our findings and suggests that social support studies require larger numbers than we were able to gain in this early exploratory study. Another possible reason for small changes in SS in the current study may be the type of SS measured. The scale used gathered information around functional support or support given to individuals in times of need. Maybe it is not this type of support that changes in such groups but more specific support such as task-specific support. It has been observed in other studies and reviews that task-specific support changes as a result of behavioural interventions (e.g. PA interventions) but general support does not seem to change in the time frames often studied [ 61 , 62 , 63 ].

There were many social wellbeing benefits such as increased social connectivity identified in focus group discussion, but the specific theme of social support was rarely mentioned. It may be that general social support through such community groups may take longer than 1 year to develop. There is evidence that strong group ties are sequentially positively associated between social identification and social support [ 34 ], suggesting that the connections formed through the groups may lead increased to social support from group members in the future. This is supported by results from the focus group discussions, where one new member felt she could call on colleagues she met in her new group. Other new members thought it was too soon for this support to be available, but they could see the bonds developing.

Other social wellbeing changes

In addition to social support and loneliness that were the focus of the quantitative study, the focus group discussions uncovered a number of other benefits of group membership that were related to social wellbeing (see Fig. 3 ). The social resources theme was of particular interest because it reflected some of the mechanisms that appeared enable social wellbeing changes as a result of being a member of a LAC but were not measured in the survey. The main social resources relating to group membership that were mentioned in the focus groups were social connectedness, development of friendships and opportunity for social responsibility or leadership. As mentioned above, there was wide-spread discussion within the focus groups of the development of social connections through the clubs. Social connectedness is defined as “the sense of belonging and subjective psychological bond that people feel in relation to individuals and groups of others.” ([ 25 ], pp1). As well as being an important predecessor of social support, greater social connectedness has been found to be highly important for the health of older adults, especially cognitive and mental health [ 26 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 64 ]. One suggested theory for this health benefit is that connections developed through groups that we strongly identify with are likely to be important for the development of social identity [ 34 ], defined by Taifel as: “knowledge that [we] belong to certain social groups together with some emotional and value significance to [us] of this group membership” (Tajfel, 1972, p. 31 in [ 58 ] p 2). These types of groups to which we identify may be a source of “personal security, social companionship, emotional bonding, intellectual stimulation, and collaborative learning and……allow us to achieve goals.” ([ 58 ] p2) and an overall sense of self-worth and wellbeing. There was a great deal of discussion relating to the opportunity for social connectedness derived through group membership being particularly pertinent following a significant life event such as moving to a new house or partners becoming unwell or dying and especially retirement. This change in their social circumstance is likely to have triggered the need to renew their social identity by joining a community group. Research with university students has shown that new group identification can assist in transition for university students who have lost their old groups of friends because of starting university [ 65 ]. In an example relevant to older adults, maintenance or increase in number of group memberships at the time of retirement reduced mortality risk 8 years later compared to people who reduce their number of group activities in a longitudinal cohort study [ 66 ]. This would fit with the original Activity Theory of ageing; whereby better ageing experience is achieved when levels of social participation are maintained, and role replacement occurs when old roles (such as working roles) must be relinquished [ 67 ]. These connections therefore appear to assist in maintaining resilience in older adults defined as “the ability to maintain or improve a level of functional ability (a combination of intrinsic physical and mental capacity and environment) in the face of adversity” (p29, [ 5 ]). Factors that were mentioned in the focus groups as assisting participants in forming connections with others were shared interest, learning from others, and a fun and accepting environment. It was not possible to assess all life events in the survey study. However, since the discussion from the focus groups suggested this to be an important motivator for joining clubs and potentially a beneficial time for joining them, it would be worth exploring in future studies.

Focus group discussion suggested that an especially valuable time for joining such clubs was around retirement, to assist with maintaining social connectivity. The social groups seem to provide social activity and new roles for these older adults at times of change. It is not necessarily important for all older adults but maybe these ones identify themselves as social beings and therefore this maintenance of social connection helps to continue their social role. Given the suggested importance of social connectivity gained through this organisation, especially at times of significant life events, it would valuable to investigate this further in future and consider encouragement of such through government policy and funding. The majority of these types of clubs exist for older adults in general, but this study emphasises the need for groups such as these to target newly retired individuals specifically and to ensure that they are not seen as ‘only for old people’.

Strengths and limitations

The use of mixed –methodologies, combining longitudinal survey study analysed quantitatively, with a qualitative exploration through focus group discussions and thematic analysis, was a strength of the current study. It allowed the researchers to not only examine the association between becoming a member of a community group on social support and loneliness over an extended period, but also obtain a deeper understanding of the underlying reasons behind any associations. Given the variability of social support definitions in research [ 17 ] and the broad area of social wellbeing, it allowed for open exploration of the topic, to understand associations that may exist but would have otherwise been missed. Embedding the research in an existing community organisation was a strength, although with this also came some difficulties with recruitment. Voluntary coordination of the community groups meant that informing new members about the study was not always feasible or a priority for the volunteers. In addition, calling for new members was innately challenging because they were not yet committed to the club fully. This meant that so some people did not want to commit to a year-long study if they were not sure how long they would be a member of the club. This resulted in slow recruitment and a resulting relatively low sample size and decreased power to show significant statistical differences, which is a limitation of the present study. However, the use of Linear Mixed Models for analysis of the survey data was a strength because it was able to include all data in the analyses and not remove participants if one time point of data was missing, as repeated measures ANOVAs would do. The length of the study (1 year) is another strength, especially compared to previous randomised controlled studies that are typically only 6–16 weeks in length. Drop-out rate in the current study is very low and probably attributable to the benefits of working with long-standing organisations.

The purpose of this study was to explore in detail whether there are any relationships between joining existing community groups for older adults and social wellbeing. The lack of existing evidence in the field meant that a small feasibility-type case study was a good sounding-board for future larger scale research on the topic, despite not being able to answer questions of causality. Owing to the particularistic nature of case studies, it can also be difficult to generalise to other types of organisations or groups unless there is a great deal of similarity between them [ 68 ]. There are however, other types of community organisations in existence that have a similar structure to LACVI (Seniors centres [ 36 , 40 ], Men’s Sheds [ 38 ], University of the Third Age [ 34 , 69 ], Japanese salons [ 70 , 71 ]) and it may be that the results from this study are transferable to these also. This study adds to the literature around the benefits of joining community organisations that offer social and physical activities for older adults and suggests that this engagement may assist with reducing loneliness and maintaining social connection, especially around the time of retirement.

Directions for future research

Given that social support trended toward a significant increase, it would be useful to repeat the study on a larger scale in future to confirm this. Either a case study on a similar but larger community group or combining a number of community organisations would enable recruitment of more participants. Such an approach would also assist in assessing the generalisability of our findings to other community groups. Given that discussions around social benefits of group membership in the focus groups was often raised in conjunction with the occurrence of significant life events, it would be beneficial to include a significant life event scale in any future studies in this area. The qualitative results also suggest that it would be useful to investigate whether people who join community groups in early years post retirement gain the same social benefits as those in later stages of retirement. Studies investigating additional health benefits of these community groups such as physical activity, depression and general wellbeing would also be warranted.

With an ageing population, it is important to investigate ways to enable older adults to age successfully to ensure optimal quality of life and minimisation of health care costs. Social determinants of health such as social support, loneliness and social contact are important contributors to successful ageing through improvements in cognitive health, quality of life, reduction in depression and reduction in mortality. Unfortunately, older adults are at risk of these social factors declining in older age and there is little research investigating how best to tackle this. Community groups offering a range of activities may assist by improving social connectedness and social support and reducing loneliness for older adults. Some factors that may assist with this are activities that encourage sharing interests, learning from others, and are conducted in a fun and accepting environment. Such groups may be particularly important in developing social contacts for newly retired individuals or around other significant life events such as moving or illness of loved ones. In conclusion, ageing policy and strategies should emphasise participation in community groups especially for those recently retired, as they may assist in reducing loneliness and increasing social connections for older adults.

Abbreviations

Focus group

Life Activities Club

Life Activities Clubs Victoria

Linear mixed model

Physical activity

World Health Organisation

United Nations. In: P.D. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, editor. World Population Ageing 2015. New York: United Nations; 2015.

Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. Global Health and Ageing. 2011 [cited 2014 March 25]; Available from: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health/en/ .

Balogun JA, et al. Age-related changes in balance performance. Disabil Rehabil. 1994;16(2):58–62.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Singh MAF. Exercise comes of age: rationale and recommendations for a geriatric exercise prescription. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2002;57(5):M262–82.

Article Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2015.

Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful Aging1. The Gerontologist. 1997;37(4):433–40.

Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):6–20.

Song M, Kong E-H. Older adults’ definitions of health: a metasynthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(6):1097–106.

Tate RB, Lah L, Cuddy TE. Definition of successful aging by elderly Canadian males: the Manitoba follow-up study. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):735–44.

Phelan EA, et al. Older Adults’ views of “successful aging”—how do they compare with Researchers’ definitions? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):211–6.

Haslam SA, et al. Social cure, what social cure? The propensity to underestimate the importance of social factors for health. Soc Sci Med. 2018;198:14–21.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316.

Richard A, et al. Loneliness is adversely associated with physical and mental health and lifestyle factors: results from a Swiss national survey. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):1–18.

Luo Y, et al. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(6):907–14.

Luo Y, Waite LJ. Loneliness and mortality among older adults in China. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(4):633–45.

de Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T, Dykstra PA. Loneliness and social isolation. In: Vangelisti A, Perlman D, editors. Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. p. 485-500.

Williams P, Barclay L, Schmied V. Defining social support in context: a necessary step in improving research, intervention, and practice. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(7):942–60.

Valtorta N, Hanratty B. Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: do we need a new research agenda? J R Soc Med. 2012;105(12):518–22.

Jylhä M. Old age and loneliness: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses in the Tampere longitudinal study on aging. Can J Aging La Revue can du vieil. 2010;23(2):157–68.

Huxhold O, Miche M, Schüz B. Benefits of having friends in older ages: differential effects of informal social activities on well-being in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(3):366–75.

Berkman L, Syme S. Social networks, host resistance and mortality: a nine year follow-up study of alameda county residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;185(11):1070–88.

House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–5.

Pynnonen K, et al. Does social activity decrease risk for institutionalization and mortality in older people? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67(6):765–74.

Broadhead WE, et al. The epidemiologic evidence for a relationship between social support and health. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117(5):521–37.

Haslam C, et al. Social connectedness and health. Encyclopedia of geropsychology. 2017:2174–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-080-3_46-1 .

Haslam C, Cruwys T, Haslam SA. “The we’s have it”: evidence for the distinctive benefits of group engagement in enhancing cognitive health in aging. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:57–66.

Uebelacker LA, et al. Social support and physical activity as moderators of life stress in predicting baseline depression and change in depression over time in the Women’s Health Initiative. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(12):1971–82.

Tajvar M, et al. Social support and health of older people in middle eastern countries: a systematic review. Australas J Ageing. 2013;32(2):71–8.

Dalgard OS, Bjork S, Tambs K. Social support, negative life events and mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(1):29–34.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57.

Gilmour H. Social participation and the health and well-being of Canadian seniors. Health Rep. 2012;23(4):1B.

Glei DA, et al. Participating in social activities helps preserve cognitive function: an analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of the elderly. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(4):864–71.

Lee SH, Kim YB. Which type of social activities may reduce cognitive decline in the elderly?: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):165.

Haslam C, et al. Group ties protect cognitive health by promoting social identification and social support. J Aging Health. 2016;28(2):244–66.

Haslam C, et al. Groups 4 health: evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. J Affect Disord. 2016;194:188–95.

Bøen H. Characteristics of senior Centre users -- and the impact of a group programme on social support and late-life depression. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2012;22(2):261–9.

Bøen H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a senior Centre group programme for increasing social support and preventing depression in elderly people living at home in Norway. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:20.

Golding BG. Social, local, and situated: recent findings about the effectiveness of older Men’s informal learning in community contexts. Adult Educ Q. 2011;61(2):103.

Life Activities Clubs. Life Activities Clubs. About Us. . 2014 [cited 2014 January 13, 2014]; Available from: http://www.life.org.au/aboutus .

Hutchinson SL, Gallant KA. Can senior Centres be contexts for aging in third places? J Leis Res. 2016;48(1):50–68.

Millard J. The health of older adults in community activities. Work Older People. 2017;21(2):90–9.

Creswell JW, Plano-Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications; 2007. p. c2007.

Loeb S, Penrod J, Hupcey J. Focus groups and older adults: tactics for success. J Gerontol Nurs. 2006;32(3):32–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Broadhead W, et al. The Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire: measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26(7):709–23.

De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T. Living arrangements of older adults in the Netherlands and Italy: Coresidence values and behaviour and their consequences for loneliness. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1999;14(1):1–24.

de Jong-Gierveld J, Kamphuls F. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1985;9(3):289–99.

Tilburg Tv, Leeuw Ed. Stability of scale quality under various data collection procedures: a mode comparison on the ‘De Jong-Gierveld loneliness scale. Int J Public Opin Res. 1991;3(1):69–85.

Hughes ME, et al. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys - results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–72.

Dickens AP, et al. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:647.

Hawkley LC, et al. Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(1):132.

Netz Y, et al. Loneliness is associated with an increased risk of sedentary life in older Israelis. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(1):40–7.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations, 2013, Version 1.2. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2011.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey - construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Sanson-Fisher RW, Perkins JJ. Adaptation and validation of the SF-36 health survey for use in Australia. J Clin Epidemiol. 51(11):961–7.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 4 ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2015.

Haslam SA, et al. Social identity, health and well-being: an emerging agenda for applied psychology. Appl Psychol. 2009;58(1):1–23.

Bartlett H, et al. Preventing social isolation in later life: findings and insights from a pilot Queensland intervention study. Ageing Soc. 2013;33(07):1167–89.

Petersen J, et al. Time out-of-home and cognitive, physical, and emotional wellbeing of older adults: a longitudinal mixed effects model. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139643.

Lindsay Smith G, et al. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):56.

Sallis JF, et al. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–36.

Oka R, King A, Young DR. Sources of social support as predictors of exercise adherence in women and men ages 50 to 65 years. Womens Health Res Gender Behav Policy. 1995;1:161–75.

CAS Google Scholar

Greenaway KH, et al. From “we” to “me”: group identification enhances perceived personal control with consequences for health and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;109(1):53–74.

Iyer A, et al. The more (and the more compatible) the merrier: multiple group memberships and identity compatibility as predictors of adjustment after life transitions. Br J Soc Psychol. 2009;48(4):707–33.

Steffens NK, et al. Social group memberships in retirement are associated with reduced risk of premature death: evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010164.

Havighurst RJ. Successful aging. Gerontol. 1961;1:8–13.

Yin R. Case study research: design and methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage publishing; 1994.

Merriam SB, Kee Y. Promoting community wellbeing: the case for lifelong learning for older adults. Adult Educ Q. 2014;64(2):128–44.

Hikichi H, et al. Social interaction and cognitive decline: results of a 7-year community intervention. Alzheimers Dement: Translat Res Clin Interv. 2017;3(1):23–32.

Hikichi H, et al. Effect of a community intervention programme promoting social interactions on functional disability prevention for older adults: propensity score matching and instrumental variable analyses, JAGES Taketoyo study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(9):905–10.

Download references

The primary author contributing to this study (GLS) receives PhD scholarship funding from Victoria University. The other authors were funded through salaries at Victoria University.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the ethics approval for this study not allowing open access to the individual participant data but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia

Gabrielle Lindsay-Smith, Grant O’Sullivan, Rochelle Eime, Jack Harvey & Jannique G. Z. van Uffelen

School of Health and Life Sciences, Federation University, Ballarat, Australia

Rochelle Eime & Jack Harvey

Department of Movement Sciences, Physical Activity, Sports and Health Research Group, KU Leuven - University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Jannique G. Z. van Uffelen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

GLS, RE and JVU made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. GLS and GOS supervised data collection for the surveys (GLS) and focus groups (GOS and GLS). GLS, GOS, RE, JH and JVU were involved in data analysis and interpretation. All authors were involved in drafting, the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gabrielle Lindsay-Smith .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Victoria University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE14–071 [survey] and HRE15–291 [focus groups]). All survey participants provided informed consent to partake in the study prior to undertaking the first survey by clicking ‘agree’ in the survey software (online participants) or signing a written consent form (paper participants) after they had read all participant information relating to the study. Focus group participants also completed a written consent form after reading and understanding all participant information regarding the study.

Consent for publication

Focus group participants have given permission for their quotes to be used in de-identified form prior to undertaking the research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lindsay-Smith, G., O’Sullivan, G., Eime, R. et al. A mixed methods case study exploring the impact of membership of a multi-activity, multicentre community group on social wellbeing of older adults. BMC Geriatr 18 , 226 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0913-1

Download citation

Received : 19 April 2018

Accepted : 10 September 2018

Published : 24 September 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0913-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social engagement

- Group activity

BMC Geriatrics

ISSN: 1471-2318

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

“So at least now I know how to deal with things myself, what I can do if it gets really bad again”—experiences with a long-term cross-sectoral advocacy care and case management for severe multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study

- Anne Müller ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2456-2492 1 ,

- Fabian Hebben ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0003-6401-3433 1 ,

- Kim Dillen 1 ,

- Veronika Dunkl 1 ,

- Yasemin Goereci 2 ,

- Raymond Voltz 1 , 3 , 4 ,

- Peter Löcherbach 5 ,

- Clemens Warnke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3510-9255 2 &

- Heidrun Golla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4403-630X 1

on behalf of the COCOS-MS trial group represented by Martin Hellmich

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 453 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Persons with severe Multiple Sclerosis (PwsMS) face complex needs and daily limitations that make it challenging to receive optimal care. The implementation and coordination of health care, social services, and support in financial affairs can be particularly time consuming and burdensome for both PwsMS and caregivers. Care and case management (CCM) helps ensure optimal individual care as well as care at a higher-level. The goal of the current qualitative study was to determine the experiences of PwsMS, caregivers and health care specialists (HCSs) with the CCM.

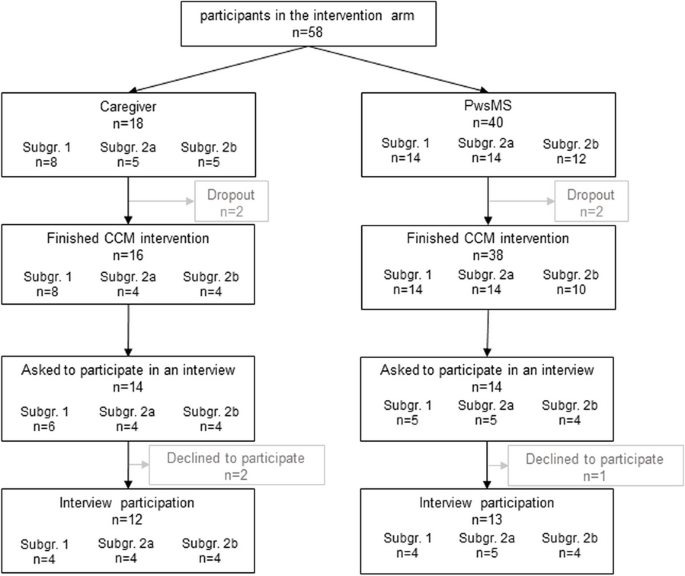

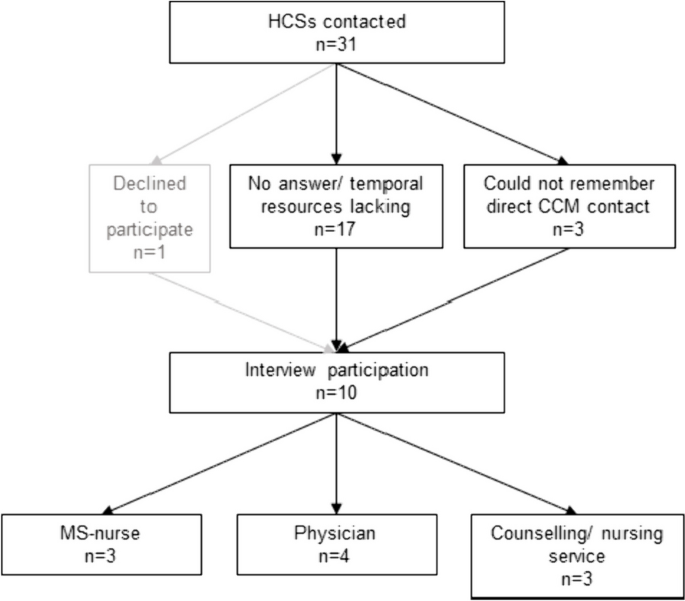

In the current qualitative sub study, as part of a larger trial, in-depth semi-structured interviews with PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs who had been in contact with the CCM were conducted between 02/2022 and 01/2023. Data was transcribed, pseudonymized, tested for saturation and analyzed using structuring content analysis according to Kuckartz. Sociodemographic and interview characteristics were analyzed descriptively.

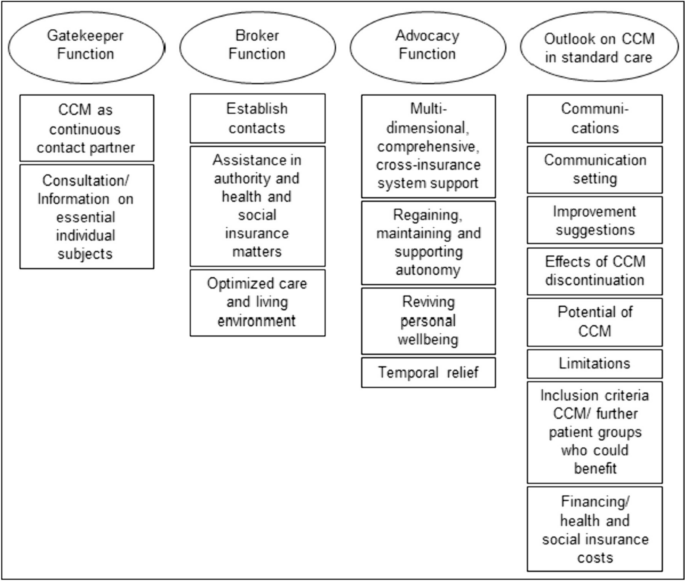

Thirteen PwsMS, 12 caregivers and 10 HCSs completed interviews. Main categories of CCM functions were derived deductively: (1) gatekeeper function, (2) broker function, (3) advocacy function, (4) outlook on CCM in standard care. Subcategories were then derived inductively from the interview material. 852 segments were coded. Participants appreciated the CCM as a continuous and objective contact person, a person of trust (92 codes), a competent source of information and advice (on MS) (68 codes) and comprehensive cross-insurance support (128 codes), relieving and supporting PwsMS, their caregivers and HCSs (67 codes).

Conclusions

Through the cross-sectoral continuous support in health-related, social, financial and everyday bureaucratic matters, the CCM provides comprehensive and overriding support and relief for PwsMS, caregivers and HCSs. This intervention bears the potential to be fine-tuned and applied to similar complex patient groups.

Trial registration

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Cologne (#20–1436), registered at the German Register for Clinical Studies (DRKS00022771) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most frequent and incurable chronic inflammatory and degenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Illness awareness and the number of specialized MS clinics have increased since the 1990s, paralleled by the increased availability of disease-modifying therapies [ 1 ]. There are attempts in the literature for the definition of severe MS [ 2 , 3 ]. These include a high EDSS (Expanded disability Status Scale [ 4 ]) of ≥ 6, which we took into account in our study. There are also other factors to consider, such as a highly active disease course with complex therapies that are associated with side effects. These persons are (still) less disabled, but may feel overwhelmed with regard to therapy, side effects and risk monitoring of therapies [ 5 , 6 ].

Persons with severe MS (PwsMS) develop individual disease trajectories marked by a spectrum of heterogeneous symptoms, functional limitations, and uncertainties [ 7 , 8 ] manifesting individually and unpredictably [ 9 ]. This variability can lead to irreversible physical and mental impairment culminating in complex needs and daily challenges, particularly for those with progressive and severe MS [ 5 , 10 , 11 ]. Such challenges span the spectrum from reorganizing biographical continuity and organizing care and everyday live, to monitoring disease-specific therapies and integrating palliative and hospice care [ 5 , 10 ]. Moreover, severe MS exerts a profound of social and economic impact [ 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. PwsMS and their caregivers (defined in this manuscript as relatives or closely related individuals directly involved in patients’ care) often find themselves grappling with overwhelming challenges. The process of organizing and coordinating optimal care becomes demanding, as they contend with the perceived unmanageability of searching for, implementing and coordinating health care and social services [ 5 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].