- CREd Library , Planning, Managing, and Publishing Research

Grant Section Analysis: Significance and Innovation

Part 2 in a section-by-section overview with tips, suggestions, and examples for writing a strong research grant application., shelley i. gray.

- April, 2014

DOI: 10.1044/cred-pvd-lfs002

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Significance

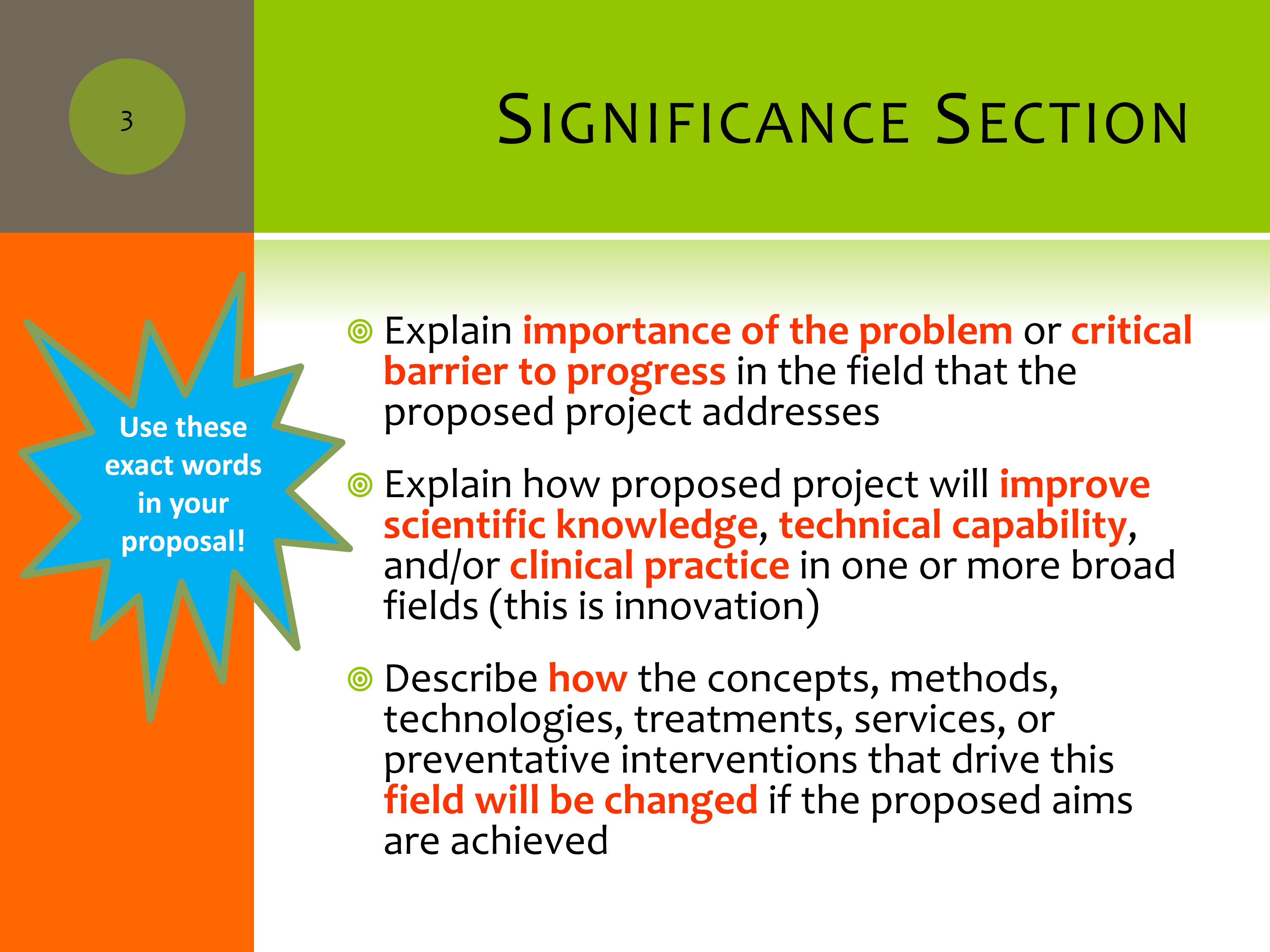

In the Significance Section, I’ve highlighted the key words straight from the instructions on what you should include. What we’re recommending is that you take this exact wording right out of the instructions and use it in your application. That makes it easy for the reviewers to find these critical words that are like little guideposts in your grant application.

You can see the words here. I think someone yesterday said that they keep a list of these things right up by their computer, or right on their desktop, as they are writing to make sure they’re being constantly reminded to include them as they write.

Clarity of Purpose

One of the more difficult things to do is to achieve this clarity of purpose. We have broad ideas, we have lots of ideas about what we want to do. For a grant application proposal, you really need to get a laser-focus on what you’re trying to accomplish, and be able to communicate that to the reviewer.

Your wording should convey your purpose clearly, enthusiastically, and concisely. To do that, one of the things I suggest is to use words with positive valence in your application. Words with positive valence evoke happy and positive thoughts as you read them. We’re using priming of positive valence words to help build a positive attitude.

Don’t be tentative. Be proactive and be confident in your grant proposal. We’ll talk about some words that are tentative. And do your best not to be vague.

Words with Positive Valence

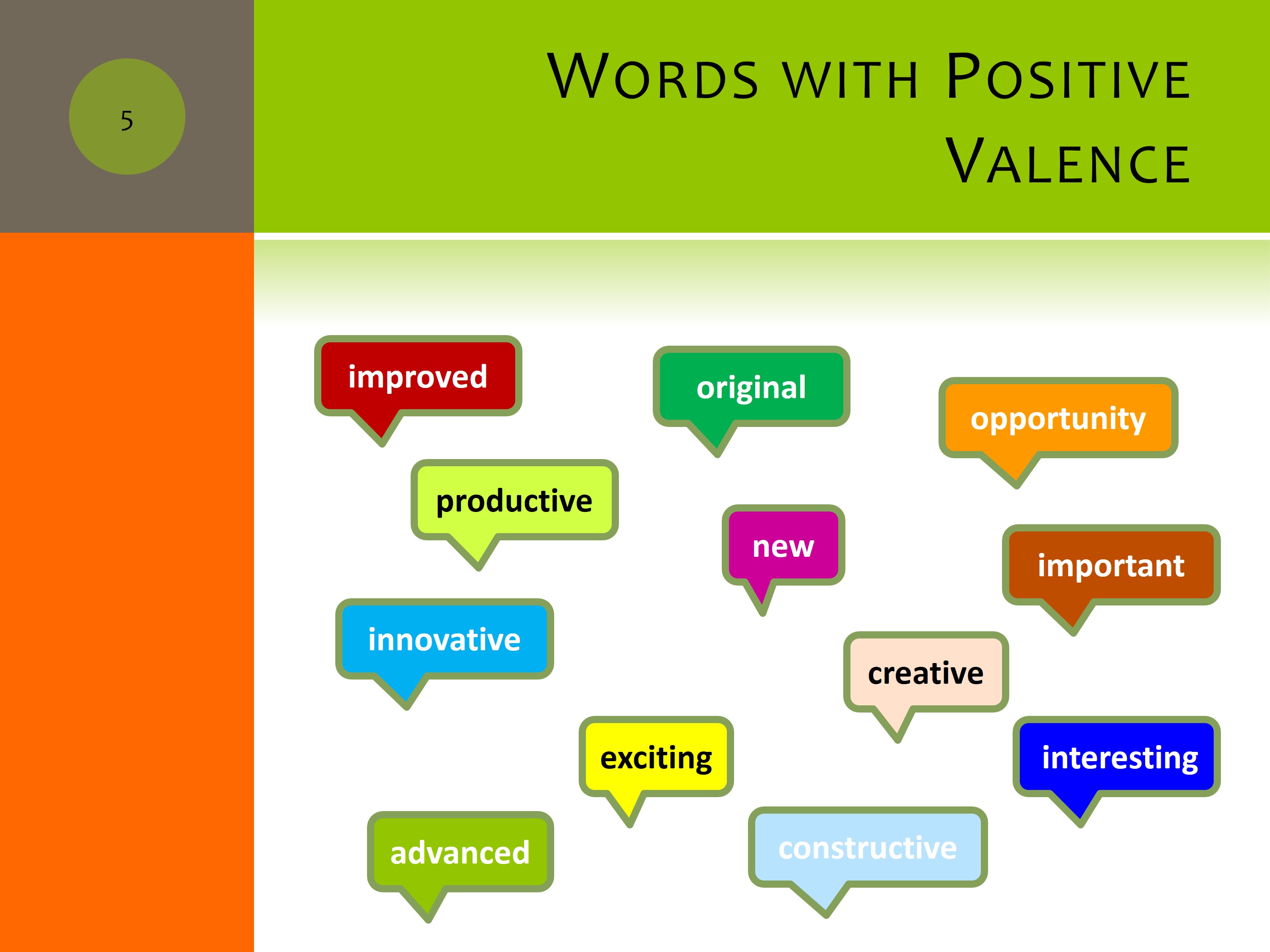

Here are some words with positive valence. Improved, original, opportunity, new, productive, innovative, exciting, creative, interesting, constructive, advanced, important, and you can probably think of a lot of other ones.

You can use these adjectives, but if what you’re proposing is not these things, it’s not going to do you any good. It really does have to be these things. But once you have that in your content and your proposal, this will help create a positive attitude.

Tentative Stance

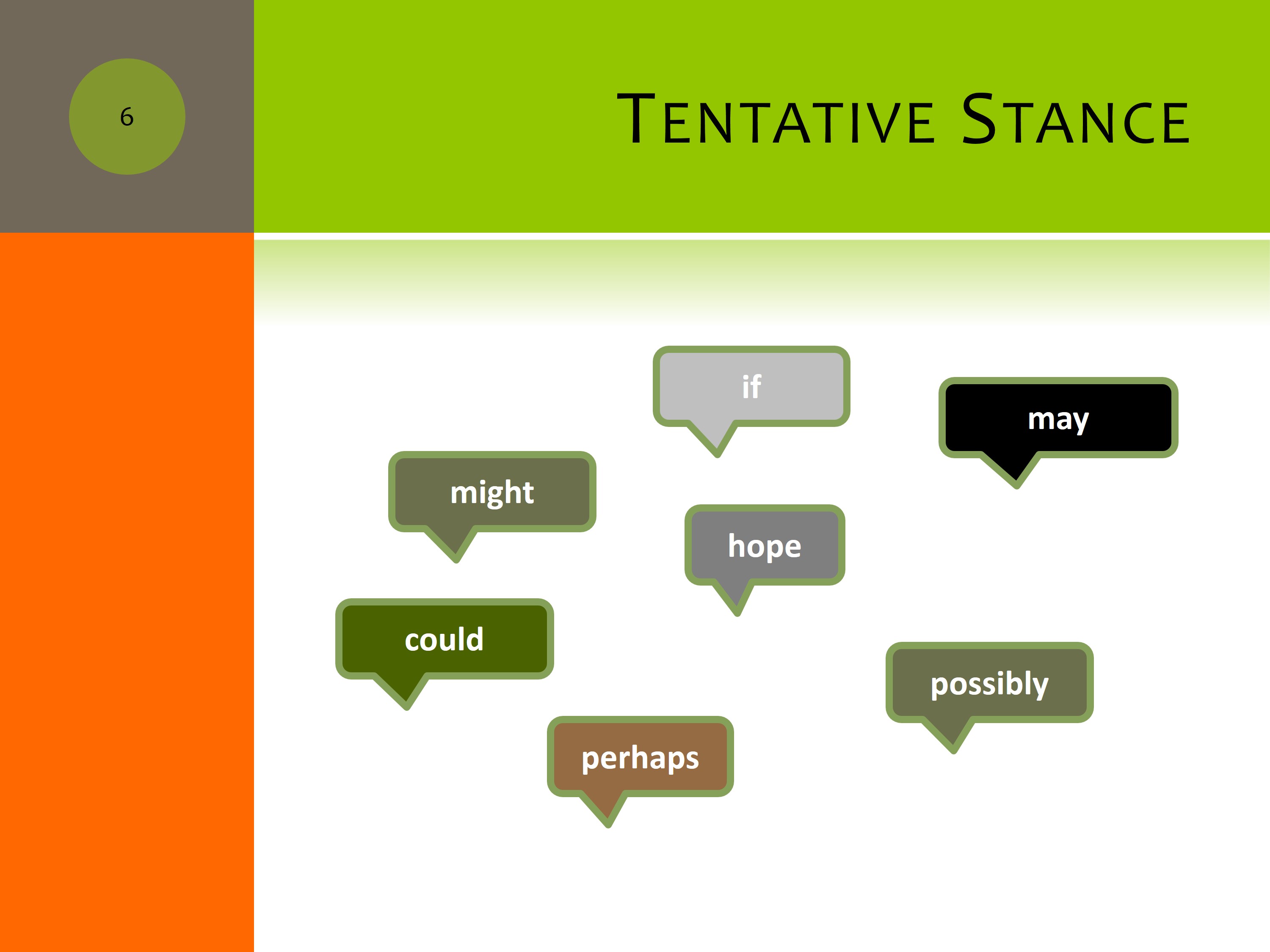

What are some words that convey a tentative stance? If. In science we use “if” statements a lot, but they shouldn’t be the kind of “if” statements that are casting doubt on whether something will turn out the way you think it will. You can use the word if for contingencies and cover both sides of the contingency, that’s important. But what you don’t want to do is raise a problem and not address it.

May — can you think of a replacement word for may?

Hope — we hope this happens. I’ve seen that in a lot of grant applications. Of course we hope it happens, but better not to say it that way.

Might — that’s another one, “it might.” In your grant application you want to plan for every contingency and let your reviewers know that you’ve thought through the different things that can happen and what you’ll do with each one of them. Same with “could.” It could happen, perhaps, possibly.

Do these words evoke a car sales ad to you? Do they make you feel like people can’t really say what this car will do for you, but it might do it, so we’re hedging our bets. You don’t want to hedge your bets in a grant application.

Vague Terminology

The thing and stuff words. Phrases like certain aspects — that’s not too specific. Some properties, a general outcome, the overall conceptualization, improved understanding, observed change, improved outlook. These might be big picture things that can happen, but when you start to use terms that aren’t real specific, it is good for you to think, “Is there something more specific I can say?”

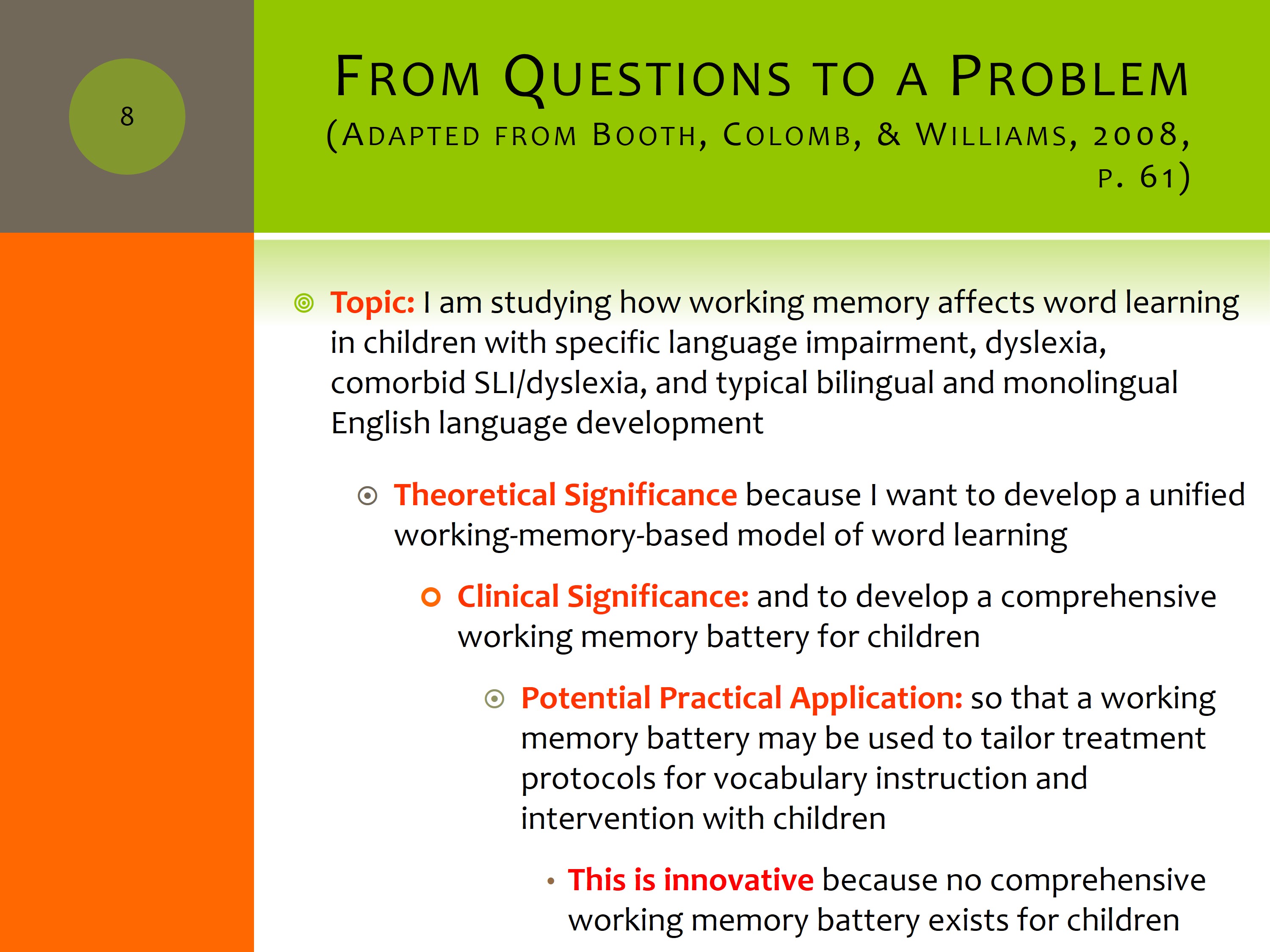

Another recommendation we introduced last year was this book (Booth, Colomb, & Williams, 2008). You can look it up on Amazon if you’d like, but one way to start — or maybe to back up if you’re having trouble with that laser focus — would be to think about something like this. Can I say in a few short sentences what I’m trying to accomplish?

Here’s an example: A real quick description of your topic. Then can you explain what you think the theoretical significance of that would be? What would be the clinical significance? Is there a potential practical application? And why is it innovative?

If you can summarize what you’re trying to do starting with this kind of an organization, chances are you’re going to be able to expand it. As someone was saying yesterday, you really need to be able to present your program of research or grant in a 30-second bite, a 2-minute bite, and so on. This kind of thing will help you do that.

Telling the Story

Integrate Your Story into the Literature Review

Another important thing to do is to think about integrating a story into your grant application. As someone said yesterday, it should read like an action novel.

On one hand, we’re talking about wordsmithing and using good grantsmanship, and you’re getting the wording in there. But on the other hand, you really need a story to unfold. And like any good writer, you’re trying to combine these two things.

What is the story you want to tell about the problem?

What is the problem? Is it an interesting problem? Is it an important problem?

Where does that problem come from? Is it a theoretical problem that we don’t have a theory in a particular area? Or the theory has been stuck at this level of conceptualization for a period of time, and we could move beyond that to suggest new lines of research? Why is it important in your story that you’re telling in the grant?

What are the gaps in knowledge that you’re particularly interested in? You’re the hero of the story, right? Your solution to the problem is the “Aha. Here comes the main character.” You are the main character and you are solving the problem that you’ve had the opportunity to build credibility for in your background section.

Convey Significance with Context

You want to explain the problem, and what is known about the problem right now in this day and age. It’s important that you are backing this up with current research. That the reviewers know that you understand the breadth of research.

Contextualize what work you have done so far that is helping to build the story. It might be published research. It might be pilot data that you have. It might be part of your training even. It you’ve contributed in any way to this work, you certainly want to highlight that.

You want to propose the next step and tell why what you’re proposing is the next logical step. What do you want to do right now that’s important? You really need to situate your problem within a theoretical framework, or at least a model to show how you fit in with history, and how you’re part fits in with the longer-playing story.

Example Sentences: Significance

Here are a couple examples to highlight the gap in knowledge or barrier to progress.

In human subjects it is difficult to determine the links among physiology, vocal function measurement, and perceptual quality because it is not possible to systematically manipulate one and observe the effects on the other.

So can you pick out the gap or barrier to progress in this paragraph? The problem is it’s difficult to determine the links among physiology, vocal function measurement, and perceptual quality — and it says not only that it’s a problem, but explains quickly and concisely why it’s a problem. Then here comes the possible solution to the problem.

Computational and physical modeling are alternative methods for studying the links among physiology, vocal function measures, and perceptual quality.

And it describes it in a very short amount of space.

Here’s a significance statement.

The proposed research is significant because understanding how specific vocal fold asymmetries contribute to voice quality will lead to improved efficiency of evaluation and treatment of voice disorders that involve vibratory asymmetry.

There’s the word “significant” — you might even want to bold it — it explains clearly and concisely why this proposed research is significant. This is the kind of quote a reviewer can lift right out of your grant proposal and put it into the significance section of the review.

Here’s another significance statement from one of our proposals that combines both the theoretical and the clinical significance.

The theoretical and clinical significance accrued across these aims include (1) data-based comparisons of four theoretically-based WM models in children, (2) the development and testing of a new working-memory-based WL model in children, (3) establishing the relationship between WM and WL in monolingual English and bilingual Spanish-English speaking children compared to children with SLI, dyslexia and SLI/dyslexia, (4) a comprehensive description of between- and within-group WL differences in large, carefully selected typical and clinical groups and (5) the refinement of a working-memory-based WL battery for future theoretical and clinical research.

In this proposal, we listed four areas that we felt were contributing both theoretically and clinically to the research base. Then, we also highlighted the population we were going to include, because we thought that was innovative as well.

These studies address important problems in the fields of psychology, language sciences and education, including the need for comprehensive working memory and word learning batteries for children to support valid and reliable assessment and the need to understand deficits underlying poor word learning so that effective treatments can be developed. By completing this research we will advance scientific knowledge in working memory and word learning for monolingual and bilingual children with typical development and children with language impairment and significantly improve the methods for assessing working memory and word learning in school age children.

These studies address important problems — so you’re going to spell out for reviewers exactly what the important problems are and what fields they are likely to impact. That comes right out of the instructions about saying how you’re going to be addressing important problems. Also, we have these keywords, “will advance scientific knowledge” in these ways, and it will “significantly improve the methods” in these ways. If you can’t figure out how it will do it, the reviewers can’t figure out how it will do it. You need to figure it out yourself, ahead of time, and put it in your application.

Yesterday we discussed that innovation can be its own section. And some people do make it its own section with a header. But it’s also important to weave innovation and words around innovation throughout your whole application to create an overall positive representation of your work.

You want to use these key words in your application. Seeking to shift current paradigms or clinical practice. Great to put that word in your application. “The proposed work will shift current clinical practice of X by doing Y.” It takes one sentence.

What’s novel about your proposal? There are many different things that could be novel, and you should highlight each of them. The theoretical concept, your approach, your methodologies, the instrumentation or intervention you propose to use. It’s great if you can explain why what you’re proposing has an advantage over what’s currently being done. Sometimes just a refinement in a methodology is an important step forward. Sometimes there is something that has been very successful and well-tested, but you are proposing a very novel application — like the example Holly gave yesterday with a book reading intervention tried with typically developing children, but it’s never been tried with children with language impairment.

As you’re telling your story, weave in about innovation.

Things That Are Innovative

Here are some things that are innovative. A new theory or model. Different application of an existing theory. Bringing in a theory or model from another field that has particular application. Applying a normal theory to a disordered population. New and better experimental methods, better instrumentation, or new approaches to analysis.

Things That Are Not Innovative

Here are some things that are not innovative and all of us have to fight against them.

Using the technique of the day, and thinking everyone will be interested in it because it is the new hot thing to do. Collecting more data because it would be interesting to know about it. You have to be careful about that word “interesting.” That in and of itself is not innovative.

And the bane of our existence, conducting more research because “very little is known” about this thing. There might be a very good reason very little is known. Maybe nobody cares one bit about it, except for you. Remember you’re going to get a lot of money for this study, so it needs to be something that people care about.

Example Sentences: Innovation

Here are some lines out of different people’s grants with innovation statements. It seeks to “shift current working memory paradigms in children by testing …”, “shift current word learning paradigms by…”, “the proposed methodology goes beyond typical measures of word learning…”, “a novel word learning battery…”, “shift current research and clinical paradigms by studying large, diverse participant groups…”, it’s innovative because “our collaboration itself is innovative.”

What I’d like you to take a minute to do here is see if you can say, “my study is significant because…” and follow that with “my study is innovative because…”

I think a really hard part about this is being concise, and capturing the essence of what you’re doing. If you can’t capture the essence, often you haven’t got the essence yet. This is a good exercise for you — it’s a good exercise for me too.

More on Grantsmanship

A little more on grantsmanship. As I already said, use and highlight the words from the grant package and the scoring guide. You should have the scoring guide that the reviewers are using right there beside you when you write. Tape it up on the wall, put on your computer screen.

Don’t go down side roads. On many of the applications that I read when I review, you see that people have a love of many areas, but often the love of that area doesn’t feed directly into the purpose of the grant. It’s important — don’t let your train go down the dirt road. Stay on the track.

Have a careful, accurate review of the research, with an appropriate scope of research and citations. The reviewers know the literature quite well. If you haven’t done a good job with your literature search, and if you don’t have a command of the literature in the area, it will show.

And use positive valence words.

We talked about figures. Defining your terminology is really important. Don’t use acronyms. But when you’re using a term, make sure you’re defining how you’re using it, because different fields use the same term differently.

We talked about including white space.

The editing. I don’t know about you, but I really need to see it on paper to edit. How many of you that review print out grants? See — there are still four or five people who still print them out. Probably half the people in the room. You need to make sure that, if you’re a better editor on paper, go ahead and print it out and edit.

You should not have any typos or grammatical errors. Zero.

Questions and Discussion

I think we have a couple minutes if you have questions.

Question: How can we avoid “if” statements when we are not certain of the outcomes of our experiments?

I think there is a difference between your hypothesis testing — where you say that if it turns out this way, this is what it will add to our field, and if it turns out this way, it will do this — as opposed to building your story on a series of “ifs,” each one contingent on the other.

One of the things reviewers will always be concerned about is, for example, if the results of specific aim two are contingent on a certain outcome from specific aim one. Because if it doesn’t work, you’ve wasted money. If you write with a lot of if statements, it sets up that expectation. That’s different from hypothesis testing.

Question: My study is not an intervention study, it’s a basic science study. For the significance part, can I imply it is clinically important when it is not directly so for my study? If this is for the future, for long-term clinical importance can I mention this? Or, if it’s not specific, is it better to just not mention it?

My thought is that they are funding the work you are proposing now. That work needs to have impact. If it has impact ten years down the road, I don’t want to pay for that now. That’s my feeling.

Audience Discussion:

- I think what it doesn’t do, is it doesn’t use that space to really boost the feeling about your current work. If it has obvious clinical implications down the road, they’ll be fairly obvious. In my opinion, you would be better off to be really specific about the positive theoretical or scientific benefits of your proposed work right now. Often we can see clinical benefits down the road, but there are so many steps to get there that what we can’t see is the next critical, short-term step. Especially for an R03.

- I’m Dan Sklare from the NIDCD, I would add to what’s been said that you have the advantage, in a fellowship application, or a career award application, of demonstrating your vision five and ten years down the road. I think that showing the impact of a more fundamental study down the road to the field is going to be easier. Because you’re doing that within the context of tracking the vision of your own evolving research career. I think you’ve got a leg up in showing significance and impact.

- Also, don’t walk away with the impression that fundamental or basic science is in itself not innovative. It can be extremely innovative. Of course, its translatability and impact to the field is another issue. I would integrate the two, and I agree with the comments previously made about the importance of showing innovation even in a fellowship proposal.

Shelley I. Gray Arizona State University

Developed by Shelley Gray, Karen Kirk, and Bonnie Martin-Harris, with past input from Melanie Schuele, Kris Tjaden, Paul Abbas, Steven Barlow, Brenda Ryals, and Jack Jiang.

Presented at Lessons for Success (April 2014). Hosted by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Research Mentoring Network.

Lessons for Success is supported by Cooperative Agreement Conference Grant Award U13 DC007835 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and is co-sponsored by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation (ASHFoundation).

Copyrighted Material. Reproduced by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association in the Clinical Research Education Library with permission from the author or presenter.

Clinical Research Education

More from the cred library, innovative treatments for persons with dementia, implementation science resources for crisp, when the ears interact with the brain, follow asha journals on twitter.

© 1997-2024 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Privacy Notice Terms of Use

How To Write Significance of the Study (With Examples)

Whether you’re writing a research paper or thesis, a portion called Significance of the Study ensures your readers understand the impact of your work. Learn how to effectively write this vital part of your research paper or thesis through our detailed steps, guidelines, and examples.

Related: How to Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research

Table of Contents

What is the significance of the study.

The Significance of the Study presents the importance of your research. It allows you to prove the study’s impact on your field of research, the new knowledge it contributes, and the people who will benefit from it.

Related: How To Write Scope and Delimitation of a Research Paper (With Examples)

Where Should I Put the Significance of the Study?

The Significance of the Study is part of the first chapter or the Introduction. It comes after the research’s rationale, problem statement, and hypothesis.

Related: How to Make Conceptual Framework (with Examples and Templates)

Why Should I Include the Significance of the Study?

The purpose of the Significance of the Study is to give you space to explain to your readers how exactly your research will be contributing to the literature of the field you are studying 1 . It’s where you explain why your research is worth conducting and its significance to the community, the people, and various institutions.

How To Write Significance of the Study: 5 Steps

Below are the steps and guidelines for writing your research’s Significance of the Study.

1. Use Your Research Problem as a Starting Point

Your problem statement can provide clues to your research study’s outcome and who will benefit from it 2 .

Ask yourself, “How will the answers to my research problem be beneficial?”. In this manner, you will know how valuable it is to conduct your study.

Let’s say your research problem is “What is the level of effectiveness of the lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) in lowering the blood glucose level of Swiss mice (Mus musculus)?”

Discovering a positive correlation between the use of lemongrass and lower blood glucose level may lead to the following results:

- Increased public understanding of the plant’s medical properties;

- Higher appreciation of the importance of lemongrass by the community;

- Adoption of lemongrass tea as a cheap, readily available, and natural remedy to lower their blood glucose level.

Once you’ve zeroed in on the general benefits of your study, it’s time to break it down into specific beneficiaries.

2. State How Your Research Will Contribute to the Existing Literature in the Field

Think of the things that were not explored by previous studies. Then, write how your research tackles those unexplored areas. Through this, you can convince your readers that you are studying something new and adding value to the field.

3. Explain How Your Research Will Benefit Society

In this part, tell how your research will impact society. Think of how the results of your study will change something in your community.

For example, in the study about using lemongrass tea to lower blood glucose levels, you may indicate that through your research, the community will realize the significance of lemongrass and other herbal plants. As a result, the community will be encouraged to promote the cultivation and use of medicinal plants.

4. Mention the Specific Persons or Institutions Who Will Benefit From Your Study

Using the same example above, you may indicate that this research’s results will benefit those seeking an alternative supplement to prevent high blood glucose levels.

5. Indicate How Your Study May Help Future Studies in the Field

You must also specifically indicate how your research will be part of the literature of your field and how it will benefit future researchers. In our example above, you may indicate that through the data and analysis your research will provide, future researchers may explore other capabilities of herbal plants in preventing different diseases.

Tips and Warnings

- Think ahead . By visualizing your study in its complete form, it will be easier for you to connect the dots and identify the beneficiaries of your research.

- Write concisely. Make it straightforward, clear, and easy to understand so that the readers will appreciate the benefits of your research. Avoid making it too long and wordy.

- Go from general to specific . Like an inverted pyramid, you start from above by discussing the general contribution of your study and become more specific as you go along. For instance, if your research is about the effect of remote learning setup on the mental health of college students of a specific university , you may start by discussing the benefits of the research to society, to the educational institution, to the learning facilitators, and finally, to the students.

- Seek help . For example, you may ask your research adviser for insights on how your research may contribute to the existing literature. If you ask the right questions, your research adviser can point you in the right direction.

- Revise, revise, revise. Be ready to apply necessary changes to your research on the fly. Unexpected things require adaptability, whether it’s the respondents or variables involved in your study. There’s always room for improvement, so never assume your work is done until you have reached the finish line.

Significance of the Study Examples

This section presents examples of the Significance of the Study using the steps and guidelines presented above.

Example 1: STEM-Related Research

Research Topic: Level of Effectiveness of the Lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ) Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice ( Mus musculus ).

Significance of the Study .

This research will provide new insights into the medicinal benefit of lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ), specifically on its hypoglycemic ability.

Through this research, the community will further realize promoting medicinal plants, especially lemongrass, as a preventive measure against various diseases. People and medical institutions may also consider lemongrass tea as an alternative supplement against hyperglycemia.

Moreover, the analysis presented in this study will convey valuable information for future research exploring the medicinal benefits of lemongrass and other medicinal plants.

Example 2: Business and Management-Related Research

Research Topic: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Social Media Marketing of Small Clothing Enterprises.

Significance of the Study:

By comparing the two marketing strategies presented by this research, there will be an expansion on the current understanding of the firms on these marketing strategies in terms of cost, acceptability, and sustainability. This study presents these marketing strategies for small clothing enterprises, giving them insights into which method is more appropriate and valuable for them.

Specifically, this research will benefit start-up clothing enterprises in deciding which marketing strategy they should employ. Long-time clothing enterprises may also consider the result of this research to review their current marketing strategy.

Furthermore, a detailed presentation on the comparison of the marketing strategies involved in this research may serve as a tool for further studies to innovate the current method employed in the clothing Industry.

Example 3: Social Science -Related Research.

Research Topic: Divide Et Impera : An Overview of How the Divide-and-Conquer Strategy Prevailed on Philippine Political History.

Significance of the Study :

Through the comprehensive exploration of this study on Philippine political history, the influence of the Divide et Impera, or political decentralization, on the political discernment across the history of the Philippines will be unraveled, emphasized, and scrutinized. Moreover, this research will elucidate how this principle prevailed until the current political theatre of the Philippines.

In this regard, this study will give awareness to society on how this principle might affect the current political context. Moreover, through the analysis made by this study, political entities and institutions will have a new approach to how to deal with this principle by learning about its influence in the past.

In addition, the overview presented in this research will push for new paradigms, which will be helpful for future discussion of the Divide et Impera principle and may lead to a more in-depth analysis.

Example 4: Humanities-Related Research

Research Topic: Effectiveness of Meditation on Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students.

Significance of the Study:

This research will provide new perspectives in approaching anxiety issues of college students through meditation.

Specifically, this research will benefit the following:

Community – this study spreads awareness on recognizing anxiety as a mental health concern and how meditation can be a valuable approach to alleviating it.

Academic Institutions and Administrators – through this research, educational institutions and administrators may promote programs and advocacies regarding meditation to help students deal with their anxiety issues.

Mental health advocates – the result of this research will provide valuable information for the advocates to further their campaign on spreading awareness on dealing with various mental health issues, including anxiety, and how to stop stigmatizing those with mental health disorders.

Parents – this research may convince parents to consider programs involving meditation that may help the students deal with their anxiety issues.

Students will benefit directly from this research as its findings may encourage them to consider meditation to lower anxiety levels.

Future researchers – this study covers information involving meditation as an approach to reducing anxiety levels. Thus, the result of this study can be used for future discussions on the capabilities of meditation in alleviating other mental health concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is the difference between the significance of the study and the rationale of the study.

Both aim to justify the conduct of the research. However, the Significance of the Study focuses on the specific benefits of your research in the field, society, and various people and institutions. On the other hand, the Rationale of the Study gives context on why the researcher initiated the conduct of the study.

Let’s take the research about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Levels of College Students as an example. Suppose you are writing about the Significance of the Study. In that case, you must explain how your research will help society, the academic institution, and students deal with anxiety issues through meditation. Meanwhile, for the Rationale of the Study, you may state that due to the prevalence of anxiety attacks among college students, you’ve decided to make it the focal point of your research work.

2. What is the difference between Justification and the Significance of the Study?

In Justification, you express the logical reasoning behind the conduct of the study. On the other hand, the Significance of the Study aims to present to your readers the specific benefits your research will contribute to the field you are studying, community, people, and institutions.

Suppose again that your research is about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students. Suppose you are writing the Significance of the Study. In that case, you may state that your research will provide new insights and evidence regarding meditation’s ability to reduce college students’ anxiety levels. Meanwhile, you may note in the Justification that studies are saying how people used meditation in dealing with their mental health concerns. You may also indicate how meditation is a feasible approach to managing anxiety using the analysis presented by previous literature.

3. How should I start my research’s Significance of the Study section?

– This research will contribute… – The findings of this research… – This study aims to… – This study will provide… – Through the analysis presented in this study… – This study will benefit…

Moreover, you may start the Significance of the Study by elaborating on the contribution of your research in the field you are studying.

4. What is the difference between the Purpose of the Study and the Significance of the Study?

The Purpose of the Study focuses on why your research was conducted, while the Significance of the Study tells how the results of your research will benefit anyone.

Suppose your research is about the Effectiveness of Lemongrass Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice . You may include in your Significance of the Study that the research results will provide new information and analysis on the medical ability of lemongrass to solve hyperglycemia. Meanwhile, you may include in your Purpose of the Study that your research wants to provide a cheaper and natural way to lower blood glucose levels since commercial supplements are expensive.

5. What is the Significance of the Study in Tagalog?

In Filipino research, the Significance of the Study is referred to as Kahalagahan ng Pag-aaral.

- Draft your Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from http://dissertationedd.usc.edu/draft-your-significance-of-the-study.html

- Regoniel, P. (2015). Two Tips on How to Write the Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from https://simplyeducate.me/2015/02/09/significance-of-the-study/

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Last Updated May 6, 2023 10:29 AM

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

Demystifying the Significance Section in Research Proposals

- No Comments

Introduction

Research proposals serve as the blueprint for groundbreaking studies, outlining the what, why, and how of a research endeavor. Among its various sections, the Significance Section emerges as a linchpin, compelling researchers to delve into the profound impact their work can have on the scientific community and beyond.

Understanding the Purpose

At its core, the Significance Section articulates the broader relevance and importance of the proposed research. It goes beyond the immediate problem at hand, highlighting why the research matters in the grander scheme of things.

Components of the Significance Section

Statement of the problem.

A well-defined problem statement lays the foundation for a compelling Significance Section. It serves as the starting point, setting the stage for the significance to unfold.

Literature Review

Intertwined with the problem statement is the literature review, providing a comprehensive backdrop to the research. It establishes the context, showcasing the existing body of knowledge and paving the way for the identification of a research gap.

Research Gap Identification

Identifying a gap in existing research is a pivotal aspect of the Significance Section. It emphasizes the unique contribution the proposed study aims to make.

Crafting a Compelling Section

Clarity and Specificity

A clear and specific Significance Section is paramount. Ambiguity can dilute the impact, making it crucial to articulate the significance with precision.

Demonstrating Relevance

Connecting the dots between the research and its relevance to the broader community adds weight to the Section. It answers the question: Why should anyone care?

Highlighting Innovation

Innovation is the heartbeat of impactful research. The Section should underscore how the proposed study breaks new ground and contributes to the advancement of knowledge.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Lack of clarity.

One pitfall to sidestep is a lack of clarity. Ambiguous or convoluted language can obfuscate the true significance of the research.

Overemphasis or Underemphasis

Finding the delicate balance is key. Overemphasizing or underemphasizing the significance can skew the perception of the proposal.

Importance for Funding Agencies

For funding agencies, the Section holds immense sway in decision-making. It serves as a litmus test, helping them discern which projects have the potential for substantial impact.

Real-Life Examples

Examining successful proposals can provide valuable insights. Let’s delve into real-life examples where a robust Section played a pivotal role in securing funding and recognition.

Impact on the Overall Proposal Evaluation

Reviewers often prioritize the Section in their evaluation. Understanding how this section influences their perception is crucial for researchers.

Tips for Improving the Significance Section

Thorough research and understanding.

In-depth research forms the bedrock of a compelling Section. A nuanced understanding of the problem and its context is indispensable.

Collaboration and Feedback

Seeking input from peers and mentors can offer fresh perspectives. Collaborative efforts often refine the Section, enhancing its impact.

Revision and Refinement

A Section is seldom perfect in the first draft. Iterative refinement is key to polishing this section to its full potential.

Significance Section Across Different Disciplines

Tailoring the Section for different research areas is an art. Understanding the nuances of each discipline ensures the section resonates effectively.

Trends in Significance Section Writing

As expectations and standards evolve, staying abreast of trends is essential. Adapting to these changes ensures proposals remain relevant and impactful.

Addressing Perplexity in Significance

Balancing complexity and clarity is an art. The Section should engage without overwhelming, navigating the fine line between perplexity and accessibility.

Burstiness in Significance

Captivating the reader’s attention requires a burst of dynamism. A Section should exude energy, sparking interest from the very first sentence.

The Role of Analogies and Metaphors

Incorporating analogies and metaphors bridges the gap between complex research and reader comprehension. Making the abstract tangible fosters a deeper connection.

In the realm of research proposals, the Significance Section reigns supreme. Demystifying its intricacies reveals its true importance—a linchpin that can elevate a proposal from ordinary to extraordinary. Let Blainy be your trusted research assistant, guiding you to get quality research paper with latest trends and updates also to discover a wealth of resources, expert insights, and personalized assistance tailored to your research needs

- The Significance Section showcases the broader impact of the research, influencing funding decisions and reviewer perceptions.

- Thorough research, collaboration, and iterative refinement are key to achieving clarity in the Significance Section.

- Analogies and metaphors make complex concepts relatable, enhancing reader engagement and understanding.

- Yes, avoiding ambiguity, overemphasis, and underemphasis are crucial for crafting an effective Significance Section.

- Tailoring the Significance Section to the nuances of each discipline ensures relevance and resonance.

Related Post

Mastering language in research papers: art of scho.

Enhancing the Visual Appeal of Research Papers

The power of precision: creating impactful researc.

How To Write a Significance Statement for Your Research

A significance statement is an essential part of a research paper. It explains the importance and relevance of the study to the academic community and the world at large. To write a compelling significance statement, identify the research problem, explain why it is significant, provide evidence of its importance, and highlight its potential impact on future research, policy, or practice. A well-crafted significance statement should effectively communicate the value of the research to readers and help them understand why it matters.

Updated on May 4, 2023

A significance statement is a clearly stated, non-technical paragraph that explains why your research matters. It’s central in making the public aware of and gaining support for your research.

Write it in jargon-free language that a reader from any field can understand. Well-crafted, easily readable significance statements can improve your chances for citation and impact and make it easier for readers outside your field to find and understand your work.

Read on for more details on what a significance statement is, how it can enhance the impact of your research, and, of course, how to write one.

What is a significance statement in research?

A significance statement answers the question: How will your research advance scientific knowledge and impact society at large (as well as specific populations)?

You might also see it called a “Significance of the study” statement. Some professional organizations in the STEM sciences and social sciences now recommended that journals in their disciplines make such statements a standard feature of each published article. Funding agencies also consider “significance” a key criterion for their awards.

Read some examples of significance statements from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) here .

Depending upon the specific journal or funding agency’s requirements, your statement may be around 100 words and answer these questions:

1. What’s the purpose of this research?

2. What are its key findings?

3. Why do they matter?

4. Who benefits from the research results?

Readers will want to know: “What is interesting or important about this research?” Keep asking yourself that question.

Where to place the significance statement in your manuscript

Most journals ask you to place the significance statement before or after the abstract, so check with each journal’s guide.

This article is focused on the formal significance statement, even though you’ll naturally highlight your project’s significance elsewhere in your manuscript. (In the introduction, you’ll set out your research aims, and in the conclusion, you’ll explain the potential applications of your research and recommend areas for future research. You’re building an overall case for the value of your work.)

Developing the significance statement

The main steps in planning and developing your statement are to assess the gaps to which your study contributes, and then define your work’s implications and impact.

Identify what gaps your study fills and what it contributes

Your literature review was a big part of how you planned your study. To develop your research aims and objectives, you identified gaps or unanswered questions in the preceding research and designed your study to address them.

Go back to that lit review and look at those gaps again. Review your research proposal to refresh your memory. Ask:

- How have my research findings advanced knowledge or provided notable new insights?

- How has my research helped to prove (or disprove) a hypothesis or answer a research question?

- Why are those results important?

Consider your study’s potential impact at two levels:

- What contribution does my research make to my field?

- How does it specifically contribute to knowledge; that is, who will benefit the most from it?

Define the implications and potential impact

As you make notes, keep the reasons in mind for why you are writing this statement. Whom will it impact, and why?

The first audience for your significance statement will be journal reviewers when you submit your article for publishing. Many journals require one for manuscript submissions. Study the author’s guide of your desired journal to see its criteria ( here’s an example ). Peer reviewers who can clearly understand the value of your research will be more likely to recommend publication.

Second, when you apply for funding, your significance statement will help justify why your research deserves a grant from a funding agency . The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), for example, wants to see that a project will “exert a sustained, powerful influence on the research field(s) involved.” Clear, simple language is always valuable because not all reviewers will be specialists in your field.

Third, this concise statement about your study’s importance can affect how potential readers engage with your work. Science journalists and interested readers can promote and spread your work, enhancing your reputation and influence. Help them understand your work.

You’re now ready to express the importance of your research clearly and concisely. Time to start writing.

How to write a significance statement: Key elements

When drafting your statement, focus on both the content and writing style.

- In terms of content, emphasize the importance, timeliness, and relevance of your research results.

- Write the statement in plain, clear language rather than scientific or technical jargon. Your audience will include not just your fellow scientists but also non-specialists like journalists, funding reviewers, and members of the public.

Follow the process we outline below to build a solid, well-crafted, and informative statement.

Get started

Some suggested opening lines to help you get started might be:

- The implications of this study are…

- Building upon previous contributions, our study moves the field forward because…

- Our study furthers previous understanding about…

Alternatively, you may start with a statement about the phenomenon you’re studying, leading to the problem statement.

Include these components

Next, draft some sentences that include the following elements. A good example, which we’ll use here, is a significance statement by Rogers et al. (2022) published in the Journal of Climate .

1. Briefly situate your research study in its larger context . Start by introducing the topic, leading to a problem statement. Here’s an example:

‘Heatwaves pose a major threat to human health, ecosystems, and human systems.”

2. State the research problem.

“Simultaneous heatwaves affecting multiple regions can exacerbate such threats. For example, multiple food-producing regions simultaneously undergoing heat-related crop damage could drive global food shortages.”

3. Tell what your study does to address it.

“We assess recent changes in the occurrence of simultaneous large heatwaves.”

4. Provide brief but powerful evidence to support the claims your statement is making , Use quantifiable terms rather than vague ones (e.g., instead of “This phenomenon is happening now more than ever,” see below how Rogers et al. (2022) explained it). This evidence intensifies and illustrates the problem more vividly:

“Such simultaneous heatwaves are 7 times more likely now than 40 years ago. They are also hotter and affect a larger area. Their increasing occurrence is mainly driven by warming baseline temperatures due to global heating, but changes in weather patterns contribute to disproportionate increases over parts of Europe, the eastern United States, and Asia.

5. Relate your study’s impact to the broader context , starting with its general significance to society—then, when possible, move to the particular as you name specific applications of your research findings. (Our example lacks this second level of application.)

“Better understanding the drivers of weather pattern changes is therefore important for understanding future concurrent heatwave characteristics and their impacts.”

Refine your English

Don’t understate or overstate your findings – just make clear what your study contributes. When you have all the elements in place, review your draft to simplify and polish your language. Even better, get an expert AJE edit . Be sure to use “plain” language rather than academic jargon.

- Avoid acronyms, scientific jargon, and technical terms

- Use active verbs in your sentence structure rather than passive voice (e.g., instead of “It was found that...”, use “We found...”)

- Make sentence structures short, easy to understand – readable

- Try to address only one idea in each sentence and keep sentences within 25 words (15 words is even better)

- Eliminate nonessential words and phrases (“fluff” and wordiness)

Enhance your significance statement’s impact

Always take time to review your draft multiple times. Make sure that you:

- Keep your language focused

- Provide evidence to support your claims

- Relate the significance to the broader research context in your field

After revising your significance statement, request feedback from a reading mentor about how to make it even clearer. If you’re not a native English speaker, seek help from a native-English-speaking colleague or use an editing service like AJE to make sure your work is at a native level.

Understanding the significance of your study

Your readers may have much less interest than you do in the specific details of your research methods and measures. Many readers will scan your article to learn how your findings might apply to them and their own research.

Different types of significance

Your findings may have different types of significance, relevant to different populations or fields of study for different reasons. You can emphasize your work’s statistical, clinical, or practical significance. Editors or reviewers in the social sciences might also evaluate your work’s social or political significance.

Statistical significance means that the results are unlikely to have occurred randomly. Instead, it implies a true cause-and-effect relationship.

Clinical significance means that your findings are applicable for treating patients and improving quality of life.

Practical significance is when your research outcomes are meaningful to society at large, in the “real world.” Practical significance is usually measured by the study’s effect size . Similarly, evaluators may attribute social or political significance to research that addresses “real and immediate” social problems.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

- APPLICATIONS

- LEARN & SUPPORT

CST BLOG: Lab Expectations

The official blog of Cell Signaling Technology (CST), where we discuss what to expect from your time at the bench, share tips, tricks, and information.

- Science Education

Writing a Grant Part 2: Significance and Innovation

The significance and innovation section is a recent (within the last 10 years) addition to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and most other foundation grant applications. It is a place for you to showcase why the work should be done — why there is a significant need for your study, and how the work is different from everyone else’s approach.

When writing this section, ask yourself: What makes my work groundbreaking, original research that will advance our scientific knowledge?

Writing the Significance Section

Let’s start with significance. Depending upon the government agency and/or institution to which you are applying, you will need to tailor this section to highlight an unmet need specific to the goals of the organization or funding opportunity to which you are applying. Whether you’ve identified a novel target for the treatment of a rare disease or you’ve designed technology with applications pertinent to national defense systems, you’ll need to be specific about what the problem is, the extent of the burden, and the paucity of adequate solutions to address it.

As an example, let’s assume that you’ve uncovered the previously-unknown role of a kinase in neuronal death and loss of motor control. A well-structured significance section may have the following subheadings and content:

- What is the underlying cause of the disease?

- How many patients are affected in the US and worldwide?

- What is the total economic impact?

- What is the clinical presentation of the disease?

- How is it treated, and what gaps in the standard of care have been revealed?

- Are there mutations in the kinase that directly correlate with disease?

- Has overexpression been shown to increase neuronal death in culture? Conversely, has knockdown been shown to be protective?

- What is the phenotype of the knockout mouse? Do these animals present with improved mobility? Do they have increased survival?

- Is the target druggable? If so, are there tool compounds available that could be assessed pre-clinically?

Writing the Innovation Section

With this foundation firmly established, you can now build the framework for how your proposal approaches the problem in a way that nobody else has tried. How will your approach change the way that people think about the problem? For some, composing this section of the grant may be foreign territory and lead to countless blank stares at the laptop screen.

When you get lost, remember that there are several types of innovation. In his first book, Mapping Innovation: A Playbook for Navigating a Disruptive Age (McGraw Hill Education, 2017), Greg Satell outlines four categories in what he terms the “innovation matrix”:

Adapted from: Mapping Innovation: A Playbook for Navigating a Disruptive Age

The problem, as addressed in the significance section, is the need being satisfied by your research. The domain is the set of skills required to solve the problem.

Let’s look at our kinase example to highlight the utility of this matrix. As part of your pre-clinical animal studies, you’ve determined the efficacy of a tool compound known to inhibit the kinase. The molecule dose-dependently reduces neuronal death and motor dysfunction, but it’s also poorly absorbed and leads to weight loss in rodents. The only means of improving the drug-like properties is to develop a novel chemical synthesis pathway. In this case, the problem is clear, but the set of skills required is not. Thus, you’re on the verge of a breakthrough innovation.

Obviously, this matrix is generic, but it can help to put your research into context. Keep in mind that the more specific you are in defining the problem, the more distinctly you can describe your innovative solution. Furthermore, no solution is complete without a few descriptive figures and a schematic of goals and objectives. Not only do you want to show that you’ve solved a certain need, but you also want to demonstrate feasibility, intermediate milestones, and future efforts.

Lastly — and this point can’t be overstated — be sure to circulate your significance and innovation sections to as many of your mentors and peers as possible. If it’s not clear to them, it certainly won’t be to your reviewers!

Read the Complete Grant Writing Series:

- Part One: First Things First

- Part Two: Significance and Innovation

- Part Three: The Experimental Approach

- Part Four: Additional Details

- Part Five: Smaller Application Components

- Part Six: Budget Justification, Letters of Support, and More

- Part Seven: How to Interpret Summary Statement and Reviewer’s Critiques

- Part Eight: What Are My Chances?

Additional Grant-Writing Resources

Check out the Cell Mentor portal for more career advice or scientific tricks and tips.

Note: The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provides sample applications along with corresponding summary statements. This is a good resource to see what gets people funded!

Topics: Techniques , Science Education

Automated IHC ChIP ELISA Flow IF-IC IHC Western Blot Workflow mIHC

Autophagy Cancer Immunology Cancer Research Cell Biology Developmental Biology Epigenetics Immunology Immunotherapy Medicine Metabolism Neurodegeneration Neuroscience Post Translational Modification Proteomics

Antibody Performance Antibody Validation Companion Reagents Fixation PTMScan Primary Antibodies Protocols Q&A Reproducibility Tech Tips Techniques

Corporate Social Responsibility

CST Newsletter

Popular posts, related posts, interrogating immnunometabolism in the tme using a metabolic checkpoint, the peer review process: what is it, and how to suggest reviewers, characterizing the autophagic-lysosomal pathway in parkinson’s disease.

- Our Company

- Our Approach

- Antibody Guarantee

- Social Responsibility

Help & Support

- Technical Support

- Order Information

- Scientific Resources

- Conferences & Events

- Publications & Posters

- Protein Modification Resource

- Videos & Webinars

- Trademark Info

- Privacy Policy

- Privacy Shield

- Cookie Policy

- Terms & Conditions

For Research Use Only. Not for Use in Diagnostic Procedures. © 2024 Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

NIH Grant Writing Tips: The Significance of “Significance”

Once upon a time, the NIH had you lead the body of your grant proposal with a section titled “Background and Significance.” Then they messed everything up by taking out the “Background” part, quite confusing many a grant writer as to the meaning of a “significance” without a “background.”

Let’s get that sorted out here.

One perspective on this comes from my book Four Steps to Funding . The four steps are The Why, The Who, The What, and The How. I take the position that you need all four of these to truly engage your readers – especially when you have a combination of both specialists and nonspecialists reading your proposal.

If it were only the specialist in your narrow little field reading your grant, you could forego some of the Why and the What – but that is actually quite rare to have such a specialized readership, despite common misconceptions to the contrary. In almost all cases, you need a very strong “Why,” as in, “why is this work important?” to draw in readers who don’t already have inherent knowledge of why your project is vital.

In grant writing lore of old, the “Why” was addressed by a sometimes long and rambling “literature review” that covered all the salient work that’s ever touched on the topic, to give the reader a “broad perspective” on the field.

That’s nice and all. But it completely ignores the reality of your grant reviewer, who is pressed at all sides for time . The last thing he (or she) usually wants to be doing at this moment is reading your grant proposal to get “yet another in-depth review” of the literature. In fact, more than anything, he just wants to be spending time on his own science, or spending time with family, or one of a myriad other more exciting things than reading your grant proposal to be “educated” on the whole field.

Some of the more experienced (read: senior) grant applicants I’ve worked with use that as a reason to skip the Significance step. They realize that the reviewer doesn’t need a pedantic education about the field, and they realize that reviewer time and attention is a scarce resource, but they implement the wrong solution. The result is often disaster.

I advocate this position that, aside from your Specific Aims, the Significance is the most vital part of your grant proposal. I advocate that if you don’t do this part well, then nothing else you do in your grant is likely to matter. While the Significance may be shorter than its following Approach section, it should never be too short.

The goal of Significance What is the goal of the Significance section? Your number one goal should be to engage your reader. You need to give her a compelling reason for paying attention. You need to give her a compelling reasons for taking interest in your science or your project and for desiring its success.

It is important to remember the context within which your grant is reviewed. It is not reviewed in isolation, but rather, within the context of a bundle of other proposals being considered at the same time. Hence, it’s not just a matter of reviewers taking interest in your project, but of them taking more interest in your project than the other projects being considered.

For example: If you’ve ever gone to the cereal isle in a US grocery store, there are a plethora of cereals to choose from. Do you buy them all? Probably not. In all likelihood, you buy one or two that you like, leaving the rest to sit on the store shelves.

Grants are a lot like that – your reviewer knows that she can only pick one or maybe two proposals to advocate for – and that’s it. The rest are going to “sit on the shelf.” However, there’s one key difference: unlike cereals, where you may have a favorite that you buy on most trips, each time the grant reviewer reviews, there is a new set of choices presented.

Successful cereal makers use quite a variety of ways in which to capture the interest of the prospective consumer, and you can learn from these. They include: compelling but not gaudy graphics and text, catering to the latest health trends, and matching their message with that of the intended audience. On the latter point, you’ll notice that cereal for kids portrays quite a different image than cereal for adults. Likewise, your potential reviewers aren’t just one big, generic mass of “scientists” – rather, they’re segmented into groups like microbiologists, oncologists, physicists, etc. Different audiences respond to different messages.

Whatever the composition of your reviewers, the very first thing that you have to do, then, is to capture the their interest.

If you boringly blend into the crowd, there’s little chance that you’ll get picked.

In your title, abstract, and Specific Aims you should have already started standing out from the crowd. Now you either make that or break that in the Significance section.

Good science isn’t good enough There’s a lot of “good” science to fund out there, and not nearly enough funding for it. “Good” science doesn’t stand out from the crowd. If all you’re doing is proposing some “good” science, it’s unlikely to be enough. That’s especially true in days of 10% or less pay lines.

Instead, you must be solving a problem that your reviewer cares about. This isn’t just something generic like “curing HIV/AIDS” or “curing cancer.” Scientists are in science because they like science (obvious, but a lot of people forget this!) They want, not only to solve pressing health problems, but to solve interesting scientific puzzles. The puzzles that your peers are interested in change with the times. You need to make sure that the puzzle you’re solving is one that is currently of interest – or your chances of attracting the necessary excitement by a reviewer is much lower.

Where many fail Here’s where many “significance” writers fall down: they assume that the reviewer comes to read the proposal already understanding what the problem, question, or challenge is. They assume some sort of magical, in-built knowledge on the part of the reviewer, almost as if there had been a brain transplant from writer to reader. In the name of due diligence, most writers will briefly re-state that problem or challenge in the span of a few sentences – but that’s far too little.

You need to spend the time and space to explain fully why this is an important and compelling problem.

You have to remember that your reader is coming from a very different place than you, and there hasn’t been any brain transplantation going on.

If you haven’t built up the challenge and the problem for your reviewer, so that she has a really strong desire to see it solved right now, then how likely is it that your grant is going to be the 1 in 10 (or less) that get funding? The likelihood is low and growing lower as paylines drop.

Your job in a nutshell, is to build desire Your job in the Significance, then, is to build desire for your project. It is not there to show how smart or well-read you are. It is not there to add even more details to how you’re going to carry out the project. It is there to give a compelling reason for the question: why does this project deserve scarce funding dollars?

Here are a few pointers that will help you do this:

- The Significance section should not be too short. For a specialist audience, it might be 1.5-2 pages. For an audience that includes non-specialists in your field, it should be longer, i.e. 2-4 pages. The extra space is used to educate your reader about the importance of the problem that you’re working on. If they’re a non-specialist, they won’t already know this, and if you fail to convey this in your significance section, then you’ll fail to generate interest or desire.

- Really good grant proposals are always based on solving a problem that peers in your field care about. Therefore, your Significance section needs to clearly delineate that problem, yet it must do so without getting into a boring lit review.

- Use your Significance section to tell a compelling, yet condensed, story of your project. Have you ever marveled at how a great film director can condense a book into a few hours on film? (e.g. Peter Jackson’s renditions of the Lord of The Rings Trilogy is a great case in point) Your goal is the same. You’ve got a “novel” in your mind about your science, but your reviewer doesn’t have time or patience for a novel (and you don’t have the space) – he only has time for the movie version. You must do the hard job of introducing the key villains and heroes with appropriate vignettes, i.e. mini-stories, and having it all flow together. I teach a “layering” approach in my Grant Foundry seminars that is one way of doing this.

- Ask really good questions and provide great insights. The entire time that someone is reading your proposal, she is judging you based on what she sees written. The best way to convince her that you’re smart and capable is not by showing “how much you know,” but instead by asking great questions and providing great insights. Don’t be stingy with your great ideas. I’ve encountered some folks who are so afraid of the competition that they withhold their best ideas. However, if you’re trying to get your grant to be the one that reviewers pick, you are unlikely to do so by being stingy with your ideas.

- Show why your team is poised and ready to tackle the problem right now. Many grant writers make the mistake of writing the proposal as a generic project that anyone could perform. Can you imagine Lord of The Rings as a “generic story?” Of course not. Nobody funds “generic projects” for “generic teams.” Instead, funders fund specific people to do specific projects that they think they are well-suited for and likely to succeed in. In your significance section, you should show the reviewer why you and your team are the right people for the job.

Writing a really good Significance section is an art form that requires practice and patience. Typically, I’ll spend far more time working on the Significance portion of a proposal than on the Innovation and Approach – even though it is a shorter section.

If you would like more help with the “Art of The Significance,” then stay tuned for an announcement of the next Grant Foundry workshop. (Not on the newsletter list? Then you’ll miss out. You can subscribe by filling in that form to the right).

If you want more clarity on getting funded in today’s environment, I’ve got a free on-demand training that will teach you how to get your reviewers excited and ready to fund your project. Sign up here.

2 replies to "NIH Grant Writing Tips: The Significance of “Significance”"

Inspiring, as always!

Very informative.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

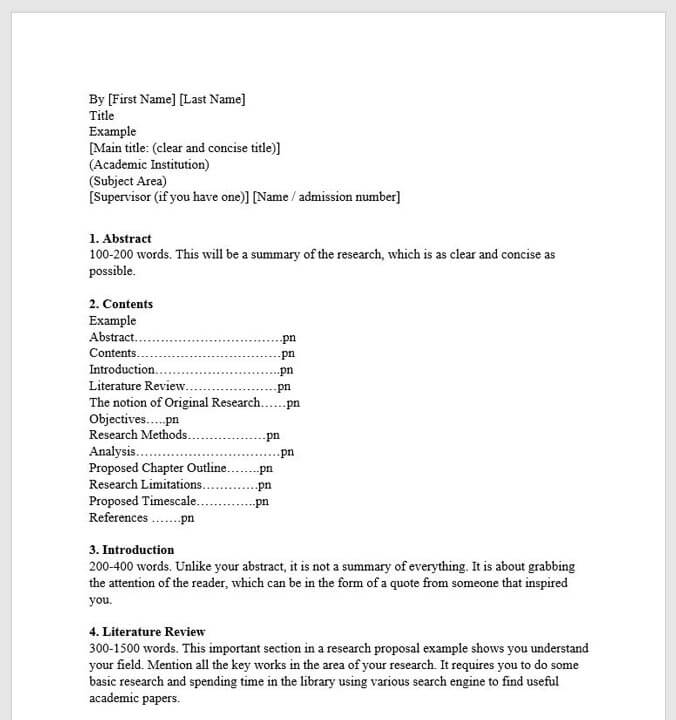

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].