- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

How to Write About Irony in a Literary Essay

Irony is used across literary genres to a variety of effects. There are two main steps to writing about irony in a literary essay. First, there’s the definition: You’ll need to recognize irony in the text and figure out what type of irony it is. Second, there’s the interpretation: You’ll comment on how that specific type of irony contributes to the overall meaning of the larger text.

Verbal Irony

In general, you can think of irony as occurring when an outcome undermines someone’s expectations. Verbal irony happens when conversational expectations are undermined. When another person listens to you speak, he usually assumes you’re saying what you mean. If you use verbal irony, you say something that you don’t want a listener to take literally. Sarcasm is one kind of verbal irony: If it’s storming, you might say, “Oh, what perfect weather for a picnic!” but expect your friend to realize that you mean just the opposite. Overstatement ( hyperbole ) and understatement (litotes) are also types of verbal irony. As is probably clear, verbal irony is heavily context dependent -- listeners or readers must know something about the speaker’s situation to interpret it correctly.

Dramatic Irony

Dramatic irony occurs when the audience knows something that a character doesn’t know. Usually, this “something” is a crucial piece of information for a decision that the character has to make. (This is the kind of irony that makes you scream at an unsuspecting heroine, “Don’t go out the back door-- the killer’s waiting there!”) For example, in William Shakespeare’s play “Romeo and Juliet,” Romeo finds Juliet in a drugged sleep, but mistakenly believes that she is dead and, in great distress, commits suicide. The gap between Romeo’s perspective -- that Juliet is dead -- and the audience’s perspective -- that Juliet is merely feigning death -- constitutes dramatic irony.

Situational Irony

Situational irony happens when a text’s plot takes a completely different turn than both the characters and the audience expect. For instance, In “Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back,” the story’s hero, Luke Skywalker, learns that the evil Darth Vader is really his father -- and the audience is just as surprised as he is. Situational irony is also sometimes called “cosmic irony” or “irony of fate.”

Interpreting Irony

Once you pinpoint and define irony, in your literary essay, you can show how irony is working to create, reinforce or undermine an overall theme of the text. For instance, in the example of dramatic irony from “Romeo and Juliet,” you could argue that Romeo’s hasty actions in response to his assumption comment on a larger theme of the play: the feud between his and Juliet’s parents. Although we might understand a smitten young lover’s rash decision to join his sweetheart in death, we can contrast his excusable immaturity with the parents’ inexcusable immaturity in holding a grudge that costs many lives. The dramatic irony of the death scene heightens our emotional response to the unnecessary nature of the lovers’ deaths. That emotion then makes us more invested in the play’s resolution, when the feuding families reconcile, and helps us to internalize one of the play’s messages: Bitter hate wounds the hater most deeply. As in all literary essays, make sure to discuss plenty of quotations (here, the ironic passages) as well as the textual and historical context to demonstrate irony’s role in the text as a whole.

- Kansas State University: Critical Concepts: Verbal Irony; Lyman Baker

Elissa Hansen has more than nine years of editorial experience, and she specializes in academic editing across disciplines. She teaches university English and professional writing courses, holding a Bachelor of Arts in English and a certificate in technical communication from Cal Poly, a Master of Arts in English from the University of Wyoming, and a doctorate in English from the University of Minnesota.

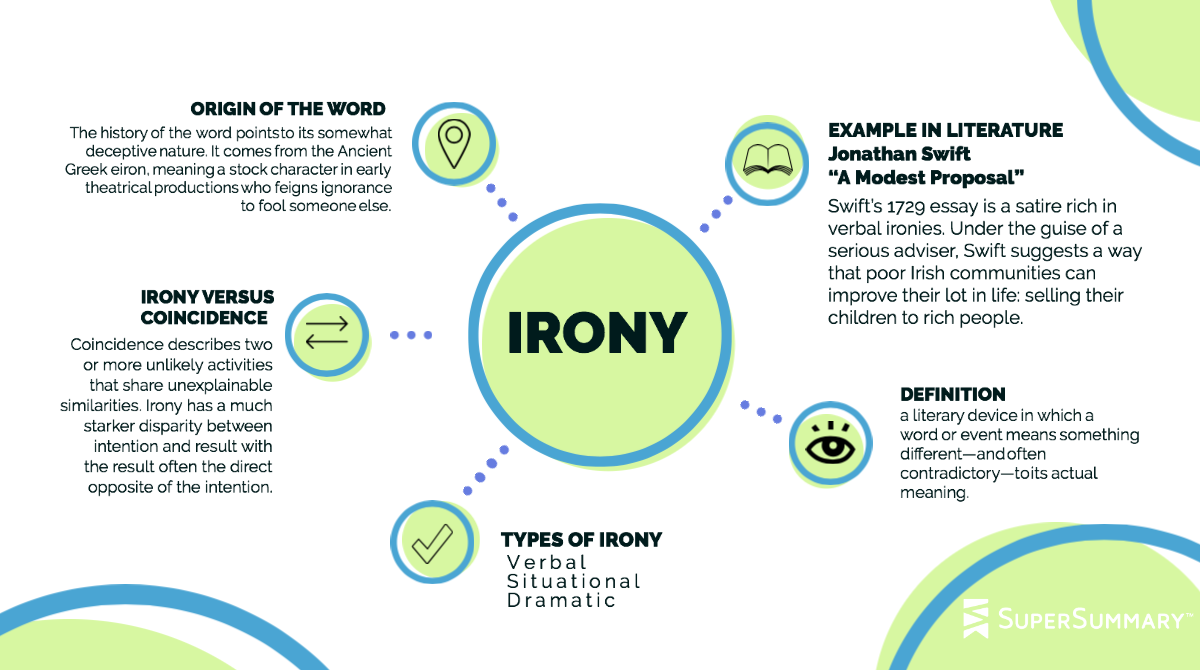

Irony Definition

What is irony? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Irony is a literary device or event in which how things seem to be is in fact very different from how they actually are. If this seems like a loose definition, don't worry—it is. Irony is a broad term that encompasses three different types of irony, each with their own specific definition: verbal irony , dramatic irony , and situational irony . Most of the time when people use the word irony, they're actually referring to one of these specific types of irony.

Some additional key details about irony:

- The term "irony" comes from the ancient Greek comic character called the "eiron," who pretends ignorance in order to deceive an opponent.

- Irony overlaps with, but is not identical to, sarcasm and satire .

- In the last twenty years or so, the term "ironic" has become popular to describe an attitude of detachment or subversive humor, like that of someone who wears a Christmas sweater as a joke. This more recent meaning of ironic is not entirely consistent with the original meaning of irony (a fact which itself might be described as being somewhat ironic).

Irony Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce irony: eye -run-ee

Irony in Depth

The term "irony" usually refers to three particular types of irony:

- Verbal irony is a figure of speech in which the literal meaning of what someone says is different from—and often opposite to—what they actually mean. For example, if someone has a painful visit to the dentist and when it's over says, "Well, that was pleasant," they are using verbal irony because the intended meaning of their words (that it wasn't at all pleasant) is the opposite of the literal meaning of the words. Verbal irony is the most common form of irony. In fact it is so common that when people mention "irony," they often are actually referring to verbal irony.

- Dramatic irony Is a plot device that highlights the difference between a character's understanding of a given situation, and that of the audience. When the audience watching a movie know what's behind that door, but the character in the movie has no idea... that's dramatic irony.

- Situational irony refers to an unexpected, paradoxical, or perverse turn of events. It is an example of situational irony when, in the O. Henry story " The Gift of the Magi ," a young wife cuts off her hair in order to buy her husband a chain for his prized watch, but the husband sells his watch to buy his wife a comb for her beautiful hair.

Although these three kinds of irony may seem very different at first glance, they all share one important quality: a tension between how things appear and how they really are. For a more in-depth look at each of these devices, please visit their individual pages.

Also, it's worth knowing that sometimes instances of irony don't quite fit into any of these categories, and instead align with the more general definition of irony as something that seems to be one way, but is in fact another way. Put more broadly: sometimes irony is verbal irony, sometimes it's dramatic irony, sometimes it's situational irony, and sometimes it's just irony.

Irony, Sarcasm, and Satire

Besides the three main types of irony described above, two other literary devices—sarcasm and satire—share a lot in common with irony:

- Sarcasm is a bitter, cutting, or mocking taunt used to denigrate a particular person, place, or thing. It can sometimes take the form of verbal irony. For instance, if you were to say to someone who had just cut you in line, "What a polite, civilized person you are!" that would be sarcasm in the form of irony, since your meaning is the opposite of the literal meaning of your words. Sarcasm very often involves irony. However, it doesn't always have to use irony. For instance, when Groucho Marx says "i never forget a face, but in your case I'll be glad to make an exception," he is being sarcastic, but his words, however witty they are, mean exactly what they say.

- Satire is a form of social or political critique. Like sarcasm, it often makes use of irony, but it isn't always ironic.

You can get more details on both sarcasm and satire at their specific pages.

Irony Examples

All three forms of irony are used very frequently in literature, theater, and film. In addition, sometimes the irony found in any of these mediums is broader and doesn't fit into any of the specific categories, and is instead just general irony.

Irony in "The Sell Out"

" The Sell Out " by Simon Rich is a short story recently published in the New Yorker that is full of irony. The story is narrated by a Polish Jew named Herschel, who lives in Brooklyn in the early twentieth century. Herschel accidentally preserves himself in brine for one hundred years, and when he is finally discovered, still alive, in 2017, he is introduced to his great-great-grandson, a young man who lives in present-day Brooklyn. On Herschel's first day, the great-great-grandson Simon tells Herschel about computers. Herschel describes the scene (note that Hershel's English isn't all that great):

It takes him long time, but eventually Simon is able to explain. A computer is a magical box that provides endless pleasure for free. Simon is used to constant access to this box—a never-ending flow of pleasures. When the box stops working—or even just briefly slows down—he becomes so enraged that he curses our God, the one who gave us life and brought us forth from Egypt.

This description is a great example of irony in the most general sense. The humor stems from the disparity between what seems to be true to Herschel (that computers are magic pleasure boxes) and what is actually true (that computers are, well, computers, and that people are kind of stupidly addicted to them). The use of irony is effective here because Hershel's description, as outlandish as it is, actually points to something that is true about the way people use computers. Therefore, the disparity between "what is" and "what appears to be" to Herschel isn't merely a comical error; rather, it's ironic because it actually points to a greater truth about its subject.

Verbal Irony in Don Quixote

One famously ironic work is Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote . At one point, the book's narrator states:

… historians should and must be precise, truthful and unprejudiced, without allowing self-interest or fear, hostility or affection, to turn them away from the path of truth, whose mother is history.

We can identify the above quotation as an example of verbal irony if we consider that the book's hero, Don Quixote, is fundamentally incapable of distinguishing truth from fiction, and any historian of his life would have to follow a double track of reality and fantasy which continuously overlaps, tangles, and flips. One of the most basic premises of the book is that truth is more difficult to identify than it may seem. Therefore, when the narrator vows to follow the single path of truth, he is being ironic; in reality, he believes this to be impossible.

Dramatic Irony in Othello

The device of dramatic irony is especially well-suited to the theater, which displays constantly shifting sets, scenes, and characters to a stationary audience that, therefore, often has a more complete or "omniscient" perspective compared to any of the characters. One excellent example of dramatic irony can be found in Shakespeare's Othello .

Through the play, the audience watches as Iago plots against his commander Othello, and seeks to make Othello believe that his wife Desdemona has been unfaithful to him. The audience watches as Iago plots to himself and with others. Sometimes Iago even directly reveals his plans to the audience. Meanwhile, Othello continues to trust Iago, and the audience watches as the the plan they know that Iago is pursuing slowly plays out just as he intended, and Othello eventually murders the entirely innocent Desdemona. The way that the play makes the audience aware of Iago's plot, even as Othello is not, means that the play is full of dramatic irony almost for its entire length.

Situational Irony in The Producers

In this classic film, two friends come up with a complicated money-making scheme in which they put on a play that they think is absolutely certain to fail. Their plan backfires when the play, entitled "Springtime for Hitler," is so shockingly bad that people think it's a comedy and come to see it in droves. This is an example of situational irony because the outcome is the exact opposite of what the play's producers expected.

Why Do Writers Use Irony?

Irony is a tool that can be used for many different purposes. Though sarcasm and satire are two ways of using irony that are primarily negative and critical, ironic statements can also underscore the fragility, complexity, and beauty of human experience.

- Situational irony often demonstrates how human beings are always at the mercy of an unpredictable universe—and that life can always take an unexpected turn.

- Dramatic irony emphasizes that human knowledge is always partial and often incorrect, while giving the reader or viewer the satisfaction of a more complete understanding than that of the characters.

- In dialogue, verbal irony can display one character's sparkling wit, and another character's thickheadedness. Verbal irony can also create a connection between people who get the irony, excluding those who don't.

Ultimately, irony is used to create meaning—whether it's humorous or profound—out of the gap between the way things appear and how they actually are.

Other Helpful Irony Resources

- The Wikipedia page on irony : A helpful overview.

- The dictionary definition of irony : A basic definition, with a bit on the etymology.

- The comedian George Carlin explaining the difference between situational irony and mere coincidence.

- A site with a helpful index of examples of different types of irony in television, film, video games, and other media.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1924 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,556 quotes across 1924 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Dramatic Irony

- Verbal Irony

- Colloquialism

- Bildungsroman

- Epanalepsis

- Tragic Hero

- Juxtaposition

- Internal Rhyme

Definition of Irony

Irony is a literary device in which contradictory statements or situations reveal a reality that is different from what appears to be true. There are many forms of irony featured in literature. The effectiveness of irony as a literary device depends on the reader’s expectations and understanding of the disparity between what “should” happen and what “actually” happens in a literary work. This can be in the form of an unforeseen outcome of an event, a character ’s unanticipated behavior, or something incongruous that is said.

One of the most famous examples of irony in literature comes from The Gift of the Magi by O. Henry. In this story , a newly married couple decides independently to sacrifice and sell what means most to themselves in order to purchase a Christmas gift for the other. Unfortunately, the gifts they receive from each other are intended for the very prized possessions they both sold. As a result, though their sacrifices symbolize the love they have for each other, the actual gifts they receive are all but useless.

Common Examples of Irony

Many common phrases and situations reflect irony. Irony often stems from an unanticipated response ( verbal irony ) or an unexpected outcome ( situational irony ). Here are some common examples of verbal and situational irony:

- Verbal Irony

- Telling a quiet group, “don’t speak all at once”

- Coming home to a big mess and saying, “it’s great to be back”

- Telling a rude customer to “have a nice day”

- Walking into an empty theater and asking, “it’s too crowded”

- Stating during a thunderstorm, “beautiful weather we’re having”

- An authority figure stepping into the room saying, “don’t bother to stand or anything”

- A comedian telling an unresponsive audience , “you all are a great crowd”

- Describing someone who says foolish things as a “genius”

- Delivering bad news by saying, “the good news is”

- Entering a child’s messy room and saying “nice place you have here”

- Situational Irony

- A fire station that burns down

- Winner of a spelling bee failing a spelling test

- A t-shirt with a “Buy American” logo that is made in China

- Marriage counselor divorcing the third wife

- Sending a Christmas card to someone who is Jewish

- Leaving a car wash at the beginning of a downpour

- A dentist needing a root canal

- Going on a blind date with someone who is visually impaired

- A police station being burglarized

- Purchasing a roll of stamps a day before the price to send a letter increases

Examples of Irony in Plot

Irony is extremely useful as a plot device. Readers or viewers of a plot that includes irony often call this effect a “twist.” Here are some examples of irony in well-known plots:

- The Wizard of Oz (L. Frank Baum): the characters already have what they are asking for from the wizard

- Time Enough at Last (episode of “The Twilight Zone”): the main character, who yearns to be left alone to read, survives an apocalyptic explosion but breaks his reading glasses

- Oedipus Rex (Sophocles): Oedipus is searching for a murderer who, it turns out, is himself

- The Cask of Amontillado ( Edgar Allan Poe ): the character “Fortunato” meets with a very unfortunate fate

- Hansel and Gretel (Grimm fairy tale ): the witch, who intended to eat Hansel ad Gretel, is trapped by the children in her own oven

Real Life Examples of Irony

Think you haven’t heard of any examples of irony in real life? Here are some instances of irony that have taken place:

- It is reported that Lady Nancy Astor once said to Winston Churchill that if he were her husband, she would poison his tea. In response, Churchill allegedly said, “Madam, if I were your husband, I’d drink it.”

- Sweden’s Icehotel, built of snow and ice, contains fire alarms.

- Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia is the official name for fear of long words

- Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury is considered an anti-censorship novel , and it is one of the most consistently banned books in the United States.

- A retired CEO of the Crayola company suffered from colorblindness.

- Many people claimed and/or believed that the Titanic was an “unsinkable” ship.

- There is a hangover remedy entitled “hair of the dog that bit you” that involves consuming more alcohol.

- George H.W. Bush reportedly stated, “I have opinions of my own, strong opinions, but I don’t always agree with them.”

Difference Between Verbal Irony, Dramatic Irony, and Situational Irony

Though there are many forms of irony as a literary device, its three main forms are verbal, dramatic, and situational. Verbal irony sets forth a contrast between what is literally said and what is actually meant. In dramatic irony , the state of the action or what is happening as far as what the reader or viewer knows is the reverse of what the players or characters suppose it to be. Situational irony refers to circumstances that turn out to be the reverse of what is expected or considered appropriate.

Essentially, verbal and situational irony are each a violation of a reader’s expectations and conventional knowledge. When it comes to verbal irony, the reader may be expecting a character’s statement or response to be one thing though it turns out to be the opposite. For situational irony, the reader may anticipate an event’s outcome in one way though it turns out to happen in a completely different way.

Dramatic Irony is more of a vicarious violation of expectations or knowledge. In other words, the reader/audience is aware of pertinent information or circumstances of which the actual characters are not. Therefore, the reader is left in suspense or conflict until the situation or information is revealed to the characters involved. For example, a reader may be aware of a superhero’s true identity whereas other characters may not know that information. Dramatic irony allows a reader the advantage of knowing or understanding something that a particular character or group of characters does not.

Writing Irony

Overall, as a literary device, irony functions as a means of portraying a contrast or discrepancy between appearance and reality. This is effective for readers in that irony can create humor and suspense, as well as showcase character flaws or highlight central themes in a literary work.

It’s essential that writers bear in mind that their audience must have an understanding of the discrepancy between appearance and reality in their work. Otherwise, the sense of irony is lost and ineffective. Therefore, it’s best to be aware of the reader or viewer’s expectations of reality in order to create an entirely different and unexpected outcome.

Here are some ways that writers benefit from incorporating irony into their work:

Plot Device

Irony in various forms is a powerful plot device. Unexpected events or character behaviors can create suspense for readers, heighten the humor in a literary work, or leave a larger impression on an audience. As a plot device, irony allows readers to re-evaluate their knowledge, expectations, and understanding. Therefore, writers can call attention to themes in their work while simultaneously catching their readers off-guard.

Method of Reveal

As a literary device, irony does not only reveals unexpected events or plot twists . It serves to showcase disparity in the behavior of characters, making them far more complex and realistic. Irony can also reveal preconceptions on the part of an audience by challenging their assumptions and expectations. In this sense, it is an effective device for writers.

Difference Between Irony and Sarcasm

Although irony encapsulates several things including situations, expressions, and actions, sarcasm only involves the use of language that is in the shape of comments. Whereas irony could be non-insulting for people, sarcasm essentially means ridiculing somebody or even insulting somebody. Therefore, it is fair to state that although sarcasm could be a part of an element of irony, the irony is a broad term, encompassing several items or ingredients of other devices in it.

Use of Irony in Sentences

- A traffic cop gets suspended for not paying his parking tickets.

- “Father of Traffic Safety” William Eno invented the stop sign, crosswalk, traffic circle, one-way street, and taxi stand—but never learned how to drive.

- Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone but refused to keep one in his study. He feared it would distract him from his work.

- Alan has been a marriage counselor for 10 years and he’s just filing for divorce.

- Oh, fantastic! Now I cannot attend the party I had been waiting for 3 months.

Examples of Irony in Literature

Irony is a very effective literary device as it adds to the significance of well-known literary works. Here are some examples of irony:

Example 1: The Necklace (Guy de Maupassant)

“You say that you bought a necklace of diamonds to replace mine?” “Yes. You never noticed it, then! They were very like.” And she smiled with a joy which was proud and naïve at once. Mme. Forestier, strongly moved, took her two hands. “Oh, my poor Mathilde! Why, my necklace was paste. It was worth at most five hundred francs!”

In his short story , de Maupassant utilizes situational irony to reveal an unexpected outcome for the main character Mathilde who borrowed what she believed to be a diamond necklace from her friend Mme. Forestier to wear to a ball. Due to vanity and carelessness, Mathilde loses the necklace. Rather than confess this loss to her friend, Mathilde and her husband replace the necklace with another and thereby incur a debt that takes them ten years of labor to repay.

In a chance meeting, Mathilde learns from her friend that the original necklace was fake. This outcome is ironic in the sense that Mathilde has become the opposite of the woman she wished to be and Mme. Forestier is in possession of a real diamond necklace rather than a false one. This ending may cause the reader to reflect on the story’s central themes, including pride, authenticity, and the price of vanity.

Example 2: Not Waving but Drowning (Stevie Smith)

Nobody heard him, the dead man, But still he lay moaning: I was much further out than you thought And not waving but drowning .

Example 3: A Modest Proposal (Jonathan Swift)

A child will make two dishes at an entertainment for friends; and when the family dines alone, the fore or hind quarter will make a reasonable dish, and seasoned with a little pepper or salt will be very good boiled on the fourth day, especially in winter .

Swift makes use of verbal irony in his essay in which he advocates eating children as a means of solving the issue of famine and poverty . Of course, Swift does not literally mean what he is saying. Instead, his verbal irony is used to showcase the dire situation faced by those who are impoverished and their limited resources or solutions. In addition, this irony is meant as a call to action among those who are not suffering from hunger and poverty to act in a charitable way towards those less fortunate.

Example 4: 1984 by George Orwell

War is Peace ; Freedom is Slavery and Ignorance is Strength .

There are several types of irony involved in the novel, 1984 , by George Orwell . The very first example is the slogan given at the beginning of the novel. This slogan is “ War is Peace ; Freedom is Slavery and Ignorance is Strength.” Almost every abstract idea is given beside or parallels to the idea that is contrary to it. These oxymoronic statements show the irony latent in them that although Oceania is at war, yet it is stressing the need for peace and the same is the case with others that although all are slaves of the state, they are calling it freedom. This is verbal irony.

Another example is that of situational irony. It is in the relationship of Winston and Julia that he secretly cherishes to have sexual advances toward her but outwardly hates her. When Julia finds that the place where it must be shunned, Junior Anti-Sex League, is the best place for such actions to do in hiding, it becomes a situational irony.

Synonyms of Irony

Some of the most known synonyms of irony are sarcasm, sardonicism, bitterness, cynicism, mockery, ridicule, derision, scorn, sneering, wryness, or backhandedness.

Related posts:

- Dramatic Irony

- 10 Examples of Irony in Shakespeare

- 15 Irony Examples in Disney Movies

- 11 Examples of Irony in Children’s Literature

- 12 Thought Provoking Examples of Irony in History

- Top 12 Examples of Irony in Poetry

- 10 Irony Examples in Shakespeare

- Romeo and Juliet Dramatic Irony

- Brevity is the Soul of Wit

- To Thine Own Self Be True

- Frailty, Thy Name is Woman

- My Kingdom for a Horse

- Lady Doth Protest too Much

- The Quality of Mercy is Not Strain’d

- Ignorance is Strength

Post navigation

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

What Is Irony? Definition and 5 Different Types of Irony to Engage Readers

by Fija Callaghan

Most of us are familiar with irony in our day to day lives—for instance, if you buy a brand new car only to have it break down on its very first ride (situational irony). Or if someone tells you they love your new dress, when what they actually mean is that it flatters absolutely no one and wasn’t even fashionable in their grandparent’s time (verbal irony).

Ironic understatement and ironic overstatement make their way into our conversations all the time, but how do you take those rascally twists of fate and use them to create a powerful story?

There are countless examples of irony in almost all storytelling, from short stories and novels to stage plays, film, poetry, and even sales marketing. Its distinctive subversion of expectation keeps readers excited and engaged, hanging on to your story until the very last page.

What is irony?

Irony is a literary and rhetorical device in which a reader’s expectation is sharply contrasted against what’s really happening. This might be when someone says the opposite of what they mean, or when a situation concludes the opposite of how one would expect. There are five types of irony: Tragic, Comic, Situational, Verbal, and Socratic.

The word irony comes from the Latin ironia , which means “feigned ignorance.” This can be a contradiction between what someone says and what they mean, between what a character expects and what they go on to experience, or what the reader expects and what actually happens in the plot. In all cases there’s a twist that keeps your story fresh and unpredictable.

By using different kinds of irony—and we’ll look at the five types of irony in literature down below—you can manage the reader’s expectations to create suspense and surprise in your story.

What’s not irony?

The words irony and ironic get thrown around a fair bit, when sometimes what someone’s really referring to is coincidence or plain bad luck. So what constitutes irony? It’s not rain on your wedding day, or or a free ride when you’ve already paid. Irony occurs when an action or event is the opposite of its literal meaning or expected outcome.

For example, if the wedding was between a woman who wrote a book called Why You Don’t Need No Man and a man who held a TEDtalk called “Marriage As the Antithesis of Evolution,” their wedding (rainy or not) would be ironic—because it’s the opposite of what we would expect.

Another perfect example of irony would be if you listened a song called “Ironic,” and discovered it wasn’t about irony after all.

Why does irony matter in writing?

Irony is something we all experience, sometimes without even recognizing it. Using irony as a literary technique in your writing can encourage readers to look at your story in a brand new way, making them question what they thought they knew about the characters, theme, and message that your story is trying to communicate.

Subverting the expectations of both your readers and the characters who populate your story world is one of the best ways to convey a bold new idea.

Aesop used this idea very effectively in his moralistic children’s tales, like “The Tortoise and the Hare.” The two title characters are set up to race each other to the finish line, and it seems inevitable that the hare will beat the tortoise easily. By subverting our expectations, and leading the story to an unexpected outcome, the author encourages the reader to think about what the story means and why it took the turn that it did.

The 5 types of irony

While all irony functions on the basis of undermining expectations, this can be done in different ways. Let’s look at the different types of irony in literature and how you can make them work in your own writing.

1. Tragic irony

Tragic irony is the first of two types of dramatic irony—both types always show the reader more than it shows its characters. In tragic dramatic irony, the author lets the reader in on the downfall waiting for the protagonist before the character knows it themselves.

This is a very common and effective literary device in many classic tragedies; Shakespeare was a big fan of using tragic irony in many of his plays. One famous example comes at the end of Romeo and Juliet , when poor Romeo believes that his girlfriend is dead. The audience understands that Juliet, having taken a sleeping potion, is only faking.

Carrying this knowledge with them as they watch the lovers hurtle towards their inevitable, heartbreaking conclusion makes this story even more powerful.

Another example of tragic irony is in the famous fairy tale “Red Riding Hood,” when our red-capped heroine goes to meet her grandmother, oblivious of any danger. The reader knows that the “grandmother” is actually a vicious, hungry wolf waiting to devour the girl, red hood and all. Much like curling up with a classic horror movie, the reader can only watch as the protagonist comes closer and closer to her doom.

This type of irony makes the story powerful, heartbreaking, and deliciously cathartic.

2. Comic irony

Comic irony uses the same structure as dramatic irony, only in this case it’s used to make readers laugh. Just like with tragic irony, this type of irony depends on allowing the reader to know more than the protagonist.

For example, a newly single man might spend hours getting ready for a blind date only to discover that he’s been set up with his former girlfriend. If the reader knows that both parties are unaware of what’s waiting for them, it makes for an even more satisfying conclusion when the two unwitting former lovers finally meet.

TV sitcoms love to use comedic irony. In this medium, the audience will often watch as the show’s characters stumble through the plot making the wrong choices. For example, in the TV series Friends , one pivotal episode shows a main character accepting a sudden marriage proposal from another—even though the audience knows the proposal was made unintentionally.

By letting the audience in on the secret, it gives the show an endearing slapstick quality and makes the viewer feel like they’re a part of the story.

3. Situational irony

Situational irony is when a story shows us the opposite of what we expect. This might be something like an American character ordering “shop local” buttons from a factory in China, or someone loudly championing the ethics of a vegan diet while wearing a leather jacket.

When most people think about ironic situations in real life, they’re probably thinking of situational irony—sometimes called cosmic irony. It’s also one of the building blocks of the twist ending, which we’ll look at in more detail below.

The author O. Henry was a master of using situational irony. In his short story “ The Ransom of Red Chief ,” two desperate men decide to get rich quick by kidnapping a child and holding him for ransom. However, the child in question turns out to be a horrendous burden and, after some negotiating, the men end up paying the parents to take him off their hands. This ironic twist is a complete reversal from the expectation that was set up at the beginning.

When we can look back on situational irony from the past, it’s sometimes called historical irony; we can retrospectively understand that an effort to accomplish one thing actually accomplished its opposite.

4. Verbal irony

Verbal irony is what we recognize most in our lives as sarcasm. It means saying the opposite of your intended meaning or what you intend the reader to understand, usually by either understatement or overstatement. This can be used for both tragic and comic effect.

For example, in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar , Mark Anthony performs a funeral speech honoring the character Brutus. He repeatedly calls him “noble” and “an honorable man,” even though Brutus was actually involved in the death of the man for which the funeral is being held. Mark Anthony’s ironic overstatement makes the audience aware that he actually holds the opposite regard for the villain, though he is sharing his inflammatory opinion in a tactful, politically safe way.

Verbal irony is particularly common in older and historical fiction in which societal constraints limited what people were able to say to each other. For example, a woman might say that it was dangerous for her to walk home all alone in the twilight, when what she really meant is that she was open to having some company.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice , the two younger girls wail that they’ve hurt their ankles, hoping to elicit some sympathy from the strong arms of the men. You can use this kind of rhetorical device to enhance your character development.

5. Socratic irony

Socratic irony is actually a little bit like dramatic irony, except that it happens between two characters rather than between the characters and the reader. This type of irony happens when one character knows something that the other characters don’t.

It’s a manipulative technique that a character uses in order to achieve a goal—to get information, to gain a confession, or to catch someone in a lie. For example, police officers and lawyers will often use this technique to trip someone up: They’ll pretend they don’t know something and ask questions in order to trick someone into saying something they didn’t intend.

Usually Socratic irony is used in a sly and manipulative way, but not always; a teacher might use the Socratic irony technique to make a child realize they know more about a subject than they thought they did, by asking them leading questions or to clarify certain points. Like verbal irony, Socratic irony involves a character saying something they don’t really mean in order to gain something from another character.

Is irony the same as a plot twist?

The “plot twist” is a stylistic way of using situational irony. In the O. Henry example we looked at above, the author sets up a simple expectation at the start of the story: the men will trade in the child for hard cash and walk away happy. Alas, life so rarely goes according to plan. By the time we reach the story’s conclusion, our expectation of the story has been completely twisted around in a fun, satisfying way.

Not all situational irony is a plot twist, though. A plot twist usually comes either at the end or at the midpoint of your story. Situational irony can happen at any time as major plot points, or as small, surprising moments that help us learn something about our characters or the world we live in.

You’ll often see plot twists being compared to dramatic irony, because they have a lot in common. Both rely on hidden information and the gradual unfurling of secrets. The difference is that with a plot twist, the reader is taken by surprise and given the new information right along with the characters. With dramatic irony, the reader is in on the trick and they get to watch the characters being taken off guard.

Both dramatic irony and plot twists can be used quite effectively in writing. It’s up to you as the writer to decide how close you want your readers and your characters to be, and how much you want them to experience together.

How to use irony in your own writing

One of the great advantages of irony is that it forces us to look at things in a new way. This is essential when it comes to communicating theme to your reader.

In literature, theme is the underlying story that’s being told—a true story, a very real message or idea about the world we live in, the way we behave within it, or how we can make it a better place. In order to get that message across to our readers, we need to give them a new way to engage with that story. The innate subversion of expectations in irony is a wonderful way to do this.

For example, the classic fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast” uses irony very effectively to communicate its theme: don’t judge a person by their appearance.

Based on our preconceptions of this classic type of fairy tale, we would go in expecting the handsome young soldier to be the hero and the beastly monster to be the adversary. We might also expect the beautiful girl to be helpless and weak-spirited, waiting for her father to come in and save her. In this story, however, it’s the girl who saves her foolish father, the handsome soldier who shows himself to be the true monster, and the beast who becomes a hero to fight for those he cares about.

Not only do these subversions make for a powerful and engaging story, they do something very important for our readers: they make them ask themselves why they had these preconceptions in the first place. Why do we expect the handsome soldier to be noble and kind? Why do we expect the worst from the man with the beastly face before even giving him the chance to speak?

It’s these honest, sometimes uncomfortable questions, more than anything else, that make the theme real for your reader.

When looking for ways to weave theme throughout your story, consider what preconceived ideas your reader might be coming into the story with that might stand in the way of what you’re trying to say. Then see if you can find ways to make those ideas stand on their head. This will make the theme of your story more convincing, resonant, and powerful.

The one mistake to never make when using irony in your story

I’m going to tell you one of life’s great truths, which might be a bit difficult for some people to wrap their heads around. Embrace it, and you’ll leave your readers feeling a lot happier and more satisfied at the end of your story. Here it is:

You don’t need to be the smartest person in the room.

Have you ever been faced with a plot twist in a story and thought, “but that doesn’t make any sense”? Or realized that a surprising new piece of information rendered the events of the plot , or the effective slow build of characterization, absolutely meaningless?

These moments happen because the author became so enamored with the idea of pulling a fast one on the reader, revealing their cleverly assembled sleight-of-hand with the flourish of a theater curtain, that they forget the most important thing: the story .

When using irony in your work, the biggest mistake you can make is to look at it like a shiny, isolated hat trick. Nothing in your story is isolated; every moment fits together as a thread in a cohesive tapestry.

Remember that even if an ironic turn is unexpected, it needs to make sense within the world of your story. This means within the time and place you’ve created—for instance, you wouldn’t create an ironic twist in a medieval fantasy by suddenly having a character whip out a cellphone—but also within the world of your characters.

For example, if it turns out your frail damsel in distress is actually a powerful sorceress intent on destroying the hero, that’s not something you can just drop into your story unannounced like a grenade (no matter how tempting it might be). You need to begin laying down story seeds for that moment right from the beginning. You want your reader to be able to go back and say “ ohhh , I see what they did there. It all makes sense now.”

Irony—in particular the “twist ending”—can be fun, surprising, and unexpected, but it also needs to be a natural progression of the world you’ve created.

Irony is a literary device that reveals new dimension

To understand irony, we need to understand expectation in our audience or readers. When you’re able to manipulate these expectations, you engage your audience in surprising ways and maybe even teach them something new.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

What is a Paradox? Definition, Types, and Examples

How to Write Flash Fiction: Short Stories in 1,500 Words or Fewer

Literary Devices List: 33 Main Literary Devices with Examples

Show, Don’t Tell: Meaning, Examples & Differences

What is an Oxymoron? Easy Definition, With Examples from Literature

Cliché vs. Trope in Writing: How They Differ, with Examples

How to Write About Irony in a Literary Essay

How to Identify Figurative Language

Irony is typically difficult to clearly explain, especially as a literary device, since part of the point of its use is to be unclear. According to the famous definition of irony given by Henry Watson Fowler in “The King’s English,” irony occurs when “...the surface meaning and the underlying meaning of what is said are not the same.” Irony can be a powerful literary tool and is typically classified into three distinct types. Once you understand which type you are working with, you'll better be able to discuss it as you write your essay.

Verbal Irony

Irony often expresses itself within a character's speech. For example, if a protagonist claims to be afraid in one context but reveals fearlessness in another, then he is using verbal irony. In the case of Plato's dialogue "Phaedo," Socrates claims to have no knowledge at all, famously pretending to be ignorant. However, it becomes clear that he actually knows many things and is depicted as philosophically superior to other characters.

Dramatic Irony

Verbal irony is defined by the contradiction between what a character says and what that character means. However, dramatic irony occurs when a character has one understanding of the situation he finds himself in and the reader (or audience) another. For example, the reader of Shakespeare's "Much Ado about Nothing" knows that Hero was always faithful to her soon-to-be-husband, Claudio. Claudio, however, does not know this and acts as if the opposite is true.

Situational Irony

The most exaggerated form of irony is situational. This occurs when neither the audience nor the characters are endowed with any special knowledge about what is about to happen. Everyone expects one set of circumstances and is, instead, confronted by another. This can be used for comedic effect but is more typically associated with tragedy. Alfred Hitchcock used situational irony in his suspenseful movies: He was notorious for shocking audiences with wildly unpredictable conclusions.

Discussing Irony

Once you've identified a particular type of irony, provide an account of the literary effect it was intended to produce. Keep in mind that any type of irony could be used by an author for a variety of purposes. For example, Jonathan Swift was able to harshly criticize English monarchy in "Gulliver's Travels" without fear of punishment as he used ironic humor to mask his judgments. Quote the ironic passages, pointing out what the author is actually saying.

Determine Success

As you're writing, assess whether the use of irony is successful. Irony shouldn’t be immediately obvious, but it also doesn't serve a purpose if it is undetectable. Review whether the author’s use of irony adequately fulfills the purpose that inspired it. If the intent is to gently teach the reader a lesson, evaluate if this is done well or whether the irony is used clumsily. This is the ultimate standard by which literary irony is to be judged when reviewing it.

Related Articles

How to Write a Thesis Statement for "Robinson Crusoe"

The Ideas of Alfred Whitehead & Ork in "Grendel"

How to Set Up a Rhetorical Analysis

How to Write a Critical Analysis of a Speech

Difference Between Literal and Figurative Language

Elements of Modernism in American Literature

Ideas for a Rhetorical Paper

How to Write an Introduction to an Analytical Essay

- The King's English; Henry Watson Fowler

- Kansas State University: Critical Concepts: Verbal Irony; Lyman A. Baker

Based in New York City, Ivan Kenneally has been writing about politics, education and American culture since 2006. His articles have appeared in national publications like the 'Washington Times," "Christian Science Monitor," "Cosmopolitan"and "Esquire." He has an Master of Arts in political theory from the New School for Social Research.

What Is Irony? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Irony definition.

Irony (EYE-run-ee) is a literary device in which a word or event means something different—and often contradictory—to its actual meaning. At its most fundamental, irony is a difference between reality and something’s appearance or expectation, creating a natural tension when presented in the context of a story. In recent years, irony has taken on an additional meaning, referring to a situation or joke that is subversive in nature; the fact that the term has come to mean something different than what it actually does is, in itself, ironic.

The history of the word points to its somewhat deceptive nature. It comes from the Ancient Greek eiron , meaning a stock character in early theatrical productions who feigns ignorance to fool someone else.

Types of Irony

When someone uses irony, it is typically in one of the three ways: verbal, situational, or dramatic.

Verbal Irony

In this form of irony, the speaker says something that differs from—and is usually in opposition with—the real meaning of the word(s) they’ve used. Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Cask of Amontillado.” As Montresor encloses Fortunato into the catacombs’ walls, he mocks Fortunato’s plea—”For the love of God, Montresor!”—by replying, “Yes, for the love of God!” Poe uses this to underscore how Montresor’s actions are anything but loving or humane—thus, far from God.

Situational Irony

This occurs when there is a difference between the intention of a specific situation and its result. The result is often unexpected or contrary to a person’s goal. The entire plot of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz hinges on situational irony. Dorothy and her friends spend the story trying to reach the Wizard so Dorothy can find a way back home, but in the end, the Wizard informs her that she had the power and knowledge to return home all along.

Dramatic Irony

Here, there is a disparity in how a character understands a situation and how the audience understands it. In Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House , the married Nora excitedly anticipates the day when she’ll be able to repay Krogstad, who illegally lent her money. She imagines a future “free from care,” but the audience understands that, because Nora must continue to lie to her husband about the loan, she will never be free.

Not all irony adheres perfectly to one of these definitions. In some cases, irony is simply irony, where something’s appearance on the surface is substantially different from the truth.

Irony vs. Coincidence

Irony is often confused with coincidence. Though there is some overlap between the two terms, they are not the same thing. Coincidence describes two or more unlikely activities that share unexplainable similarities. It is often confused with situational irony. For example, finding out a friend you made in adulthood went to your high school is a coincidence, not an ironic event. Additionally, coincidence isn’t classifiable by type.

Irony, on the other hand, has a much starker and more substantial disparity between intention and result, with the result often the direct opposite of the intention. For example, the fact that the word lisp is ironic, considering it refers to an inability to properly pronounce s sounds but itself contains an s .

The Functions of Irony

How an author uses irony depends on their intentions and the story or scene’s larger context . In much of literature, irony highlights a larger point the author is making—often a commentary on the inherent difficulties and messiness of human existence.

With verbal irony, a writer can demonstrate a character’s intelligence, wit, or snark—or, as in the case of “ The Cask of Amontillado ,” a character’s unmitigated evil. It is primarily used in dialogue and rarely offers up any insight into the plot or meaning of a story.

With dramatic irony, a writer illustrates that knowledge is always a work in progress. It reiterates that people rarely have all the answers in life and can easily be wrong when they don’t have the right information. By giving readers knowledge the characters do not have, dramatic irony keeps readers engaged in the story; they want to see if and when the characters learn this information.

Finally, situational irony is a statement on how random and unpredictable life can be. It showcases how things can change in the blink of an eye and in bigger ways than one ever anticipated. It also points out how humans are at the mercy of unexplained forces, be they spiritual, rational, or matters of pure chance.

Irony as a Function of Sarcasm and Satire

Satire and sarcasm often utilize irony to amplify the point made by the speaker.

Sarcasm is a rancorous or stinging expression that disparages or taunts its subject. Thus, it usually possesses a certain amount of irony. Because inflection conveys sarcasm more clearly, saying a sarcastic remark out loud helps make the true meaning known. If someone says “Boy, the weather sure is beautiful today” when it is dark and storming, they’re making a sarcastic remark. This statement is also an example of verbal irony because the speaker is saying something in direct opposition to reality. But an expression doesn’t necessarily need to be verbal to communicate its sarcastic nature. If the previous example appeared in a written work, the application of italics would emphasize to the reader that the speaker’s use of the word beautiful is suspect. To further clarify, the remark would closely precede or follow a description of the day’s unappealing weather.

Satire is an entire work that critiques the behavior of specific individuals, institutions, or societies through outsized humor. Satire normally possesses both irony and sarcasm to further underscore the illogicality or ridiculousness of the targeted subject. Satire has a long history in literature and popular culture. The first known satirical work, “The Satire of the Trades,” dates back to the second millennium BCE. It discusses a variety of trades in an exaggerated, negative light, while presenting the trade of writer as one of great honor and nobility. Shakespeare famously satirized the cultural and societal norms of his time in many of his plays. In 21st-century pop culture, The Colbert Report was a political satire show, in which host Stephen Colbert played an over-the-top conservative political commentator. By embodying the characteristics—including vocal qualities—and beliefs of a stereotypical pundit, Colbert skewered political norms through abundant use of verbal irony. This is also an example of situational irony, as the audience knew Colbert, in reality, disagreed with the kind of ideas he was espousing.

Uses of Irony in Popular Culture

Popular culture has countless examples of irony.

One of the most predominant, contemporary references, Alanis Morissette’s hit song “Ironic” generated much controversy and debate around what, exactly, constitutes irony. In the song, Morissette sings about a variety of unfortunate situations, like rainy weather on the day of a wedding, finding a fly floating in a class of wine, and a death row inmate being pardoned minutes after they were killed. Morissette follows these lines with the question, “Isn’t it ironic?” In reality, none of these situations is ironic, at least not according to the traditional meaning of the word. These situations are coincidental, frustrating, or plain bad luck, but they aren’t ironic. The intended meaning of these examples is not disparate from their actual meanings. For instance, another line claims that having “ten thousand spoons when all you need is a knife” is ironic. This would only be ironic, if, say, the person being addressed made knives for a living. Morissette herself has acknowledged the debate and asserted that the song itself is ironic because none of the things she sings about are ironic at all.

Pixar/Disney’s movie Monsters, Inc. is an example of situational irony. In the world of this movie, monsters go into the human realm to scare children and harvest their screams. But, when a little girl enters the monster world, it’s revealed that the monsters are actually terrified of children. There are also moments of dramatic irony. As protagonist Sully and Mike try to hide the girl’s presence, she instigates many mishaps that amuse the audience because they know she’s there but other characters have no idea.

In the iconic television show Breaking Bad , DEA agent Hank Schrader hunts for the elusive drug kingpin known as Heisenberg. But what Hank doesn’t know is that Heisenberg is really Walter White, Hank’s brother-in-law. This is a perfect example of dramatic irony because the viewers are aware of Walter’s secret identity from the moment he adopts it.

Examples of Irony in Literature

1. Jonathan Swift, “A Modest Proposal”

Swift’s 1729 essay is a satire rich in verbal ironies. Under the guise of a serious adviser, Swift suggests a way that poor Irish communities can improve their lot in life: selling their children to rich people. He even goes a step further with his advice:

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout.

Obviously, Swift does not intend for anyone to sell or eat children. He uses verbal ironies to illuminate class divisions, specifically many Britons’ attitudes toward the Irish and the way the wealthy disregard the needs of the poor.

2. William Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus

This epic Shakespeare tragedy is brutal, bloody, farcical, and dramatically ironic. It concerns the savage revenge exacted by General Titus on those who wronged him. His plans for revenge involve Tamora, Queen of the Goths, who is exacting her own vengeance for the wrongs she feels her sons have suffered. The audience knows from the outset what these characters previously endured and thus understand the true motivations of Titus and Tamora.

In perhaps the most famous scene, and likely one of literature’s most wicked dramatic ironies, Titus slays Tamora’s two cherished sons, grinds them up, and bakes them into a pie. He then serves the pie to Tamora and all the guests attending a feast at his house. After revealing the truth, Titus kills Tamora—then the emperor’s son, Saturninus, kills Titus, then Titus’s son Lucius kills Saturninus and so on.

3. O. Henry, “The Gift of the Magi”

In this short story, a young married couple is strapped for money and tries to come up with acceptable Christmas gifts to exchange. Della, the wife, sells her hair to get the money to buy her husband Jim a watchband. Jim, however, sells his watch to buy Della a set of combs. This is a poignant instance of situational irony, the meaning of which O. Henry accentuates by writing that, although “[e]ach sold the most valuable thing he owned in order to buy a gift for the other,” they were truly “the wise ones.” That final phrase compares the couple to the biblical Magi who brought gifts to baby Jesus, whose birthday anecdotally falls on Christmas Day.

4. Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

Atwood’s dystopian novel takes place in a not-too-distant America. Now known as Gilead, it is an isolated and insular country run by a theocratic government. Since an epidemic left many women infertile, the government enslaves those still able to conceive and assigns them as handmaids to carry children for rich and powerful men. If a handmaid and a Commander conceive, the handmaid must give the child over to the care of the Commander and his wife. Then, the handmaid is reassigned to another “post.”

A primary character in the story is Serena Joy, a Commander’s wife. In one of the book’s many ironic instances, it is revealed that Serena, in her pre-Gilead days, was a fierce advocate for a more conservative society. Though she now has the society she fought for, women—even Commanders’ wives—have few rights. Thus, she ironically suffers from the very reforms she spearheaded.

Further Resources on Irony

The Writer has an article about writing and understanding irony in fiction.

Penlighten ‘s detailed list of irony examples includes works mainly from classic literature.

Publishing Crawl offers five ways to incorporate dramatic irony into your writing .

Harvard Library has an in-depth breakdown of the evolution of irony in postmodern literature .

TV Tropes is a comprehensive resource for irony in everything from literature and anime to television and movies.

Related Terms

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Faculty Notes Submission Form

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is Irony? | Definition & Examples

"what is irony": a guide for english students and teachers.

View the Full Series: The Oregon State Guide to Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- OSU Admissions Info

What is Irony? - Transcription (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in the Video. Click HERE for the Spanish transcript)

By Raymond Malewitz , Oregon State University Associate Professor of American Literature

5 November 2019

As we transition from childhood into adulthood, we begin to realize that things, people, and events are often not what they appear to be. At times, this realization can be funny, but it can also be disturbing or confusing. Children often recoil at this murky confusion, preferring a simple world in which what you see is what you get. Adults, on the other hand, often LOVE this confusion-- so much so that we often tell ourselves stories just to conjure up this state. Whether we run from it or savor it, make no mistake: “irony” is a dominant feature of our lives.

In simplest terms, irony occurs in literature AND in life whenever a person says something or does something that departs from what they (or we) expect them to say or do. Just as there are countless ways of misunderstanding the world [sorry kids], there are many different kinds of irony. The three most common kinds you’ll find in literature classrooms are verbal irony, dramatic irony, and situational irony .

Verbal irony occurs whenever a speaker or narrator tells us something that differs from what they mean, what they intend, or what the situation requires. Many popular internet memes capitalize upon this difference, as in this example.

maxresdefault.jpg

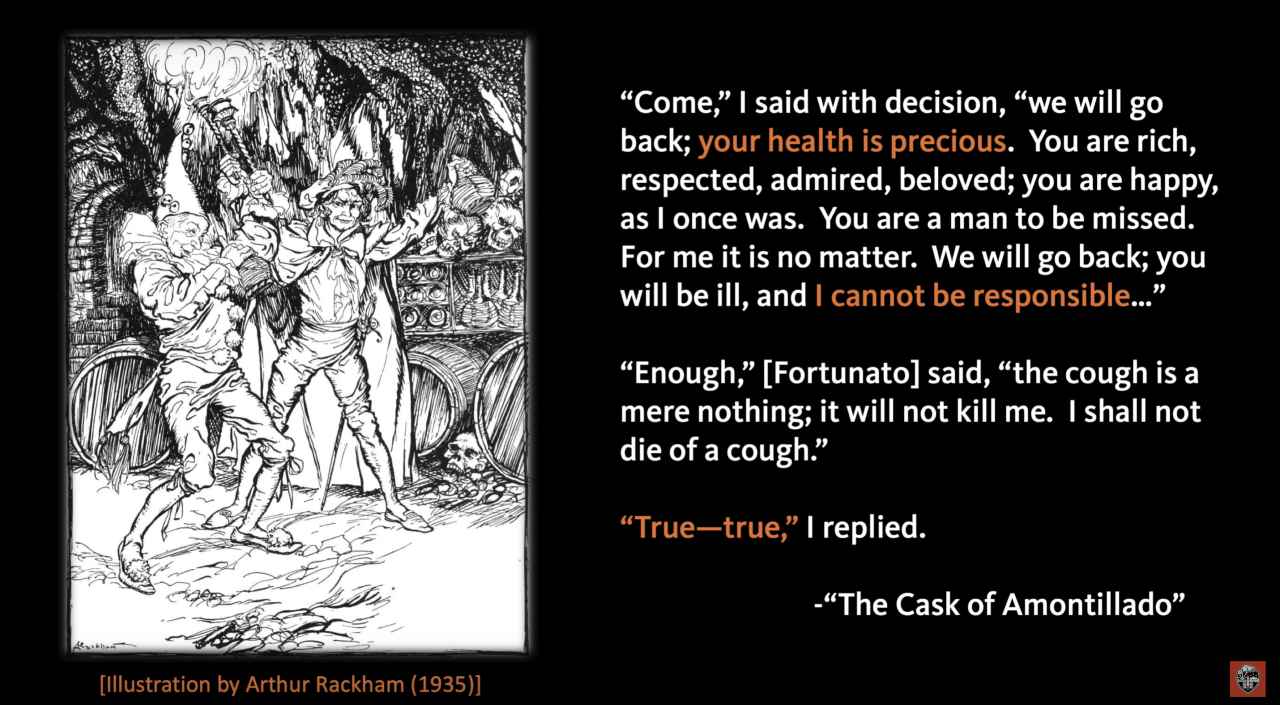

Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Cask of Amontillado” offers a more complex example of verbal irony. In the story, a man named Montresor lures another man named Fortunato into the catacombs beneath his house by appearing to ask him for advice on a recent wine purchase. In reality, he means to murder him. Brutally. By walling him up in those catacombs [spoiler alert]!

As the two men travel deeper underground, Fortunato has a coughing fit. Montresor appears to comfort him in the following richly ironic exchange:

“Come,” I said with decision, “we will go back; your health is precious. You are rich, respected, admired, beloved; you are happy, as I once was. You are a man to be missed. For me it is no matter. We will go back; you will be ill, and I cannot be responsible…”

“Enough,” [Fortunato] said, “the cough is a mere nothing; it will not kill me. I shall not die of a cough.”

“True—true,” I replied.”

from_poes_cask_of_amontillado.jpg

If we only paid attention to the appearance of Montresor’s words, we would think he was genuinely concerned with poor Fortunato’s health as he hacks up a lung. We would also think that Montresor was trying to be nice to Fortunato by agreeing with him that he won’t die of a cough. But knowing Montresor’s true intentions, which he reveals at the start of the story, we are able to understand the verbal irony that colors these assurances. Fortunato won’t die of a cough, Montresor knows, but he will definitely die.

This scene is also a great example of dramatic irony . Dramatic irony occurs whenever a character in a story is deprived of an important piece of information that governs the plot that surrounds them. Fortunato, in this case, believes that Montresor is a friendly schlub with a terrible wine palette and a curious habit of storing his wine near the dead bodies of his ancestors. The pleasure of reading the story stems in part from knowing what he doesn’t—that he’s walking into Montresor’s trap. We delight, in other words, in the ironic difference between our complex way of understanding of the world and Fortunato’s simple worldview.

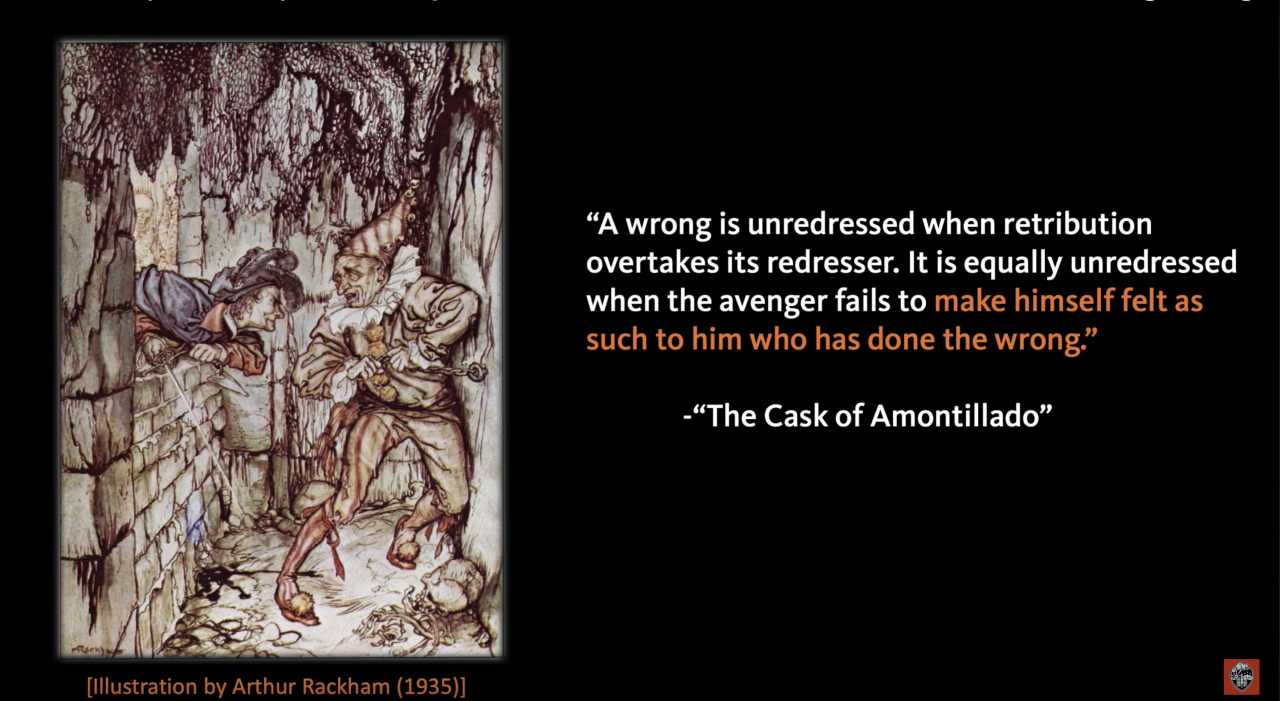

Finally, the story also includes, arguably, a great example of situational irony . As its name suggests, situational irony occurs when characters’ intentions are foiled, when people do certain things to bring about an intended result, but in fact produce the opposite result. At the start of the story, Montresor tells his readers that his project will succeed only if he “makes himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong.”

from_poes_cask_of_amontillado_ii.jpg

In other words, Fortunato must not only know that he has been tricked but also why he was tricked and why he must die. If this is Montresor’s intention, however, he goes about it in a rather strange way, offering Fortunato countless sips of wine on their trip into the catacombs that gets his antagonist pretty drunk. By the end of the story, Montresor has certainly got away with the crime, but it’s far from certain that Fortunato (or even Montresor) knows why he is given such a terrible death.

So why does Montresor insist on telling us that his story is a success? One reason might be that he is anxious about the situational irony that envelopes his story and wants to cover the reality of that irony with a simple appearance of triumph. He’s gotten away with it, and Fortunato knows why he must die. If readers push back against this desired outcome, testing it against Fortunato’s confusion at being chained to a wall and bricked into place, they travel further than even Montresor is willing to go into the murky catacombs of irony.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Malewitz, Raymond. "What is Irony?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 5 Nov. 2019, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-irony. Accessed [insert date].

Further Resources for Teachers:

Kate Chopin's story "The Story of an Hour" offers students many opportunities to discuss different kinds of irony. These ideas are indirectly discussed in our "What is Imagery?" video. Many other literary terms can be used for ironic effect, including Understatement , Free Indirect Discourse , Dramatic Monologue , and Unreliable Narrator . Yiyun Li's short story "A Thousand Years of Good Prayers" is another story suitable for this kind of analysis.

Writing Prompt #1: Identify examples of verbal irony, dramatic irony, and situational irony in Chopin's or Li's story. When you have made these determinations, explain how they operate together to convey meaning in the story.

Writing Prompt #2: See the prompt in our " What is a Sonnet? " video.

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

- Literary Terms

When and How to Use Irony

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Irony

How to Use Irony

Irony can be tough to write because first you have to notice something ironic to write about a situation, which is a kind of insight . That’s also why it’s a fairly impressive writing technique. So the trick is not to practice writing irony but to practice noticing it. Look around you every day, and you will see plenty of ways in which ordinary expectations are contradicted by what happens in the real, unpredictable world.

As you look around for irony, take care to avoid the pitfall of confusing irony with coincidence . Often coincidences are ironic, and often they are not. Think of it this way: a coincidence would be if firemen, on the way home from putting out a fire, suddenly got called back out to fight another one. Irony would be if their fire truck caught on fire. The latter violates our expectations about fire trucks, whereas the former is just an unfortunate (but not necessarily unexpected) turn of events.

Another way of putting it is this: coincidence is a relationship between facts (e.g. Fire 1 and Fire 2), whereas irony is a relationship between a fact and an expectation and how they contradict each other.

When to use irony

Irony belongs more in creative writing than in formal essays . It’s a great way of getting a reader engaged in a story, since it sets up expectations and then provokes an emotional response. It also makes a story feel more lifelike, since having our expectations violated is a universal experience. And, of course, humor is always valuable in creative writing.

Verbal irony is also useful in creative writing, especially in crafting characters or showing us their mind and feelings. Take this passage as an example:

Eleanor turned on her flashlight and stepped carefully into the basement. She kept repeating to herself that she was not afraid. She was not afraid. She was not afraid.

Even though the author keeps repeating “she was not afraid,” we all know that Eleanor was afraid. But we also know that she was trying to convince herself otherwise, and this verbal irony gives us additional psychological insight into the character. Rather than just saying “Eleanor was afraid of the basement,” the author is giving us information about how Eleanor deals with fear, and the emotions she is feeling as she enters the basement.

In formal essays , you should almost never use irony, but you might very well point it out . Irony is striking in any context, and a good technique for getting the reader’s attention. For example, a paper about the history of gunpowder could capture readers’ interest by pointing out that this substance, which has caused so much death over the years, was discovered by Chinese alchemists seeking an elixir of immortality.

It goes without saying that you shouldn’t express your own thoughts by using verbal irony in a formal essay – a formal essay should always present exactly what you mean without tricks or disguises.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

- The use of irony in Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

Irony is a powerful and common literary device that is skillfully incorporated throughout the narrative of Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice,” contributing to both character development and societal critique. The completed relationships and social conventions of the early 19th century are examined in this narrative, which is set in England. The main focus of this answer is on the various verbal, situational, and dramatic ironies used by Austen. It demonstrates how these devices are used to expose hidden truths, subvert social norms, and influence character development. By exploring the complex nature of irony, this answer tries to demonstrate how essential it is to the work’s depth and complexity, emphasizing how it affects character dynamics and contributes to a larger critique of societal conventions within the societal setting that Austen’s timeless work portrays.

Table of Contents

Verbal Irony in Pride and Prejudice

The language and narration of the characters in “Pride and Prejudice” are examples of verbal irony, which adds a subtle humor and reveals underlying realities. For example, Mr. Collins uses obsequious compliments that appear to be complimenting but actually serves to draw attention to his own conceit and lack of self-awareness. Renowned for her wit, Elizabeth Bennet frequently employs verbal irony with astute rejoinders that respectfully but gently express her actual opinions. Similar to this, Mr. Darcy’s seemingly cold remarks, especially during their early exchanges with Elizabeth, conceal his developing fondness and sincere care. These examples of verbal irony give the characters more depth and reveal to the reader what their genuine feelings are. This results in a story where words have several meanings and enhances Jane Austen’s social commentary and character development.

Read More: Women Characters in Pride and Prejudice

Situational Irony in Pride and Prejudice:

This kind of irony adds complexity to the story by arising through unexpected turns in the plot that surprise readers. The abrupt exit of Mr. Bingley from Netherfield, which was thought to indicate the end of his love interest in Jane Bennet, contrasts with his later return, demonstrating the erratic nature of romantic relationships. Situational irony is best illustrated by Lydia’s elopement with Mr. Wickham, in which the results of her impetuous actions go against accepted social mores and expectations. Furthermore, the novel’s thematic richness is enhanced by the situational irony that challenges readers’ preconceived notions by showing how Mr. Darcy’s true nature is one of humility and genuine care, in contrast to his initial impression as an aloof and seemingly proud aristocrat. Jane Austen’s deft use of situational irony to develop the plot and offer critical commentary on love, society, and human nature is best shown by these plot twists and character revelations.

Read More: Jane Austen’s Art of Characterization

Dramatic Irony in Pride and Prejudice:

The difference between what readers know and what the characters believe in “Pride and Prejudice” is the source of dramatic irony, which gives the story a greater depth. As readers witness Mr. Darcy’s fondness for Elizabeth grow over time, Elizabeth’s ignorance of his actual feelings for her serves as a perfect example. Another example is of Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s attempts to manipulate Elizabeth’s marriage; readers are made aware of Lady Catherine’s intervention while Elizabeth proceeds with the issue with little knowledge. The novel’s suspense and hilarity are also increased by giving readers insight into the motivations and genuine goals of the characters, such as Mr. Collins’s obsequious desire of a wealthy wife or Mr. Wickham’s dishonesty. The use of dramatic irony in Jane Austen’s writing not only affects readers on an emotional level but also highlights the author’s ability to create a story in which asymmetry in knowledge adds to the complexity of relationships and social commentary.

Irony in Social Commentary

Jane Austen used irony as a potent tool to parody and criticize the social mores of early 19th-century England. Irony permeates Mrs. Bennet’s unrelenting efforts to place her daughters in advantageous marriages, particularly her desire on finding affluent husbands. The irony is in the humorous and frequently erroneous nature of Mrs. Bennet’s attempts to improve her family’s social status through favorable pairings, which highlights the flimsiness of conventional expectations. The ironic portrayal of Lady Catherine de Bourgh highlights the ridiculousness of inflexible class divisions by showing her as an aristocratic lady trying to influence other people’s marriage decisions. In addition, Austen’s sharp social criticism is highlighted by the novel’s satirical depiction of society expectations for women, such as the focus on getting married well rather than out of love. This highlights the contradictions between accepted social conventions and real human connections. Through these examples, Austen uses irony as a means of challenging and criticizing popular beliefs about marriage, societal expectations, and class.