- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

There is more to war poetry than mud, wire and slaughter

Poems about the first world war have defined the genre for decades. It is time to hear from new voices that reflect a wider view of conflicts

W hen we say “war poetry” today, the sort of writing that comes to mind is a conglomeration of Wilfred Owen , Siegfried Sassoon and the other great writers of the first world war. It means descriptions of mud, wire and slaughter on a horrific scale. It includes accusations that the top brass prolonged hostilities for no good reason and that people at home supported the cause in ignorance. It involves fierce protest as well as intense sympathy. It issues a warning.

Because poetry of this sort has been drip-fed into British schools for several generations (interestingly, the process did not start as soon as the war ended, but only began in earnest during the 1960s), it has settled in the public mind at an extraordinary depth. There are large benefits, of course. The best poetry of the first world war is exceptionally powerful – not just the lyrics of Owen and others, but the more complex and modernistic narrative of In Parenthesis by David Jones (which still has some claim to be considered a neglected masterpiece). Furthermore, by rubbing its readers’ noses in the brutal facts of conflict and suffering, it possibly creates a social value as well – by helping to educate people in the human cost of war, and in the process discouraging them from starting or supporting another one.

At the same time, maybe there are disadvantages. Perhaps by placing such an emphasis on war poetry in the school curriculum, we don’t actually put people off the idea of fighting, but inculcate the idea that it is somehow normal for the British to take up arms? Perhaps it solidifies the idea of us as a war-like nation? There is a literary consequence to the classroom focus too. By concentrating on the poetry of one conflict, which to an important extent is shaped by its particular circumstances, it directs attention away from the poetry of other wars.

Not just the poetry of other wars, in fact, but other kinds of war poetry. “I am the enemy you killed, my friend,” says the dead soldier encountered in Owen’s “Strange Meeting”: “I parried; but my hands were loath and cold”. This summarises the whole circumstance of first world war poetry: it often involved hand-to-hand fighting; it was intimate. The second world war, by contrast, was for many soldiers a more distanced affair. Keith Douglas when taking aim in his poem “How to Kill”, says: “Now in my dial of glass appears / the soldier who is going to die”. He still thinks of him as a fellow creature (the soldier “moves about in ways / his mother knows, habits of his”) but also feels a crucial separation – a gap that exists as a physical space, and proves the conflict has frozen or exterminated a part of the speaker’s own humanity.

The difference between these two poems is shorthand for the differences between two periods and two kinds of war poetry. It is also an opportunity to point out that while the Owen poem has been read by millions of schoolchildren in the last 50-odd years, the Douglas poem (which is just as good, if not better) has been read by a handful. By not conforming to the pattern of war poetry laid down between 1914 and 1918 (actually between about 1916 and 1918), it has been sidelined.

The point here is not to discredit poetry of the first world war. As a collective act of witness, made at an extraordinary level of technical skill and with equally extraordinary emotional power, it is in its terrible way magnificent. The point, rather, is to say that our definition of “war poetry” has become too narrow to be accurate or fair. By extending it we are not only able to make a large literary gain – by admiring a much wider range of expertise, thoughtfulness and compassion – but also to appreciate in even more varied and detailed ways the effects of war.

This applies to the first world war itself, if we look away from the frontline and move to the home-front poetry of men in uniform such as Edward Thomas , or women waiting for them such as Eleanor Farjeon . Or to the extraordinary reports by nurses and other volunteers such as Helen Mackay, May Wedderburn Cannan and Margaret Postgate Cole . Or to the visceral and proto-existentialist poems and songs and chants of “Anonymous” (“I don’t want a bayonet up my arsehole, / I don’t want my bollocks shot away”).

A glance across the landscape of war poetry written after 1918 gives an even more dramatic sense of variety. The frontline (in north Africa, then France) brilliantly evoked by Douglas – in his poetry as well as his memoir Alamein to Zem Zem – is just a part of the large picture in which also appears Alun Lewis writing about soldierly boredom and nervous waiting during the second world war, and Dylan Thomas writing about the blitz – and, around them, international voices speaking with and through and over them: Nelly Sachs , Paul Celan , Anna Akhmatova and Tadeusz Różewicz .

As we come towards the present day, our sense of dilation becomes even greater. Not just in the sense that poets have made far-flung wars visible at home ( Yusef Komunyakaa writing about Vietnam, for instance, or Brian Turner about Iraq), but also because the reporting of wars in the media has encouraged non-combatants to address the subject in greater numbers than ever before. This is a difficult business, since it is all too easy to get caught grandstanding, or parading sensitivities, or seeming to aggrandise oneself by associating with a grand subject. But when it is done well it produces poems that earn the right to sit besides those written by people in uniform: Tony Harrison ’s “A Cold Coming” , for example, or James Fenton ’s “Dead Soldiers”.

Before the first world war, war poetry since time immemorial ( The Iliad ) had been largely concerned to celebrate, commend, remember and, yes, grieve. Think of Lord Byron ’s Assyrian, coming down like a wolf on the fold, or Sir John Moore in Charles Wolfe’s poem about the battle of Corunna . Since 1918, like war itself, the poetry of conflict has become a thing of infinite variety, describing apparently infinite tragedy. Yet for all this – which deserves more acknowledgment than it gets – something has stayed the same. The something Owen meant when he spoke about “the pity”.

- Point of view

- First world war

- Second world war

Most viewed

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.4: The War Poets

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 134628

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Understand the effects of World War I on Britain and on the development of Modern literature.

- Recognize the cognitive dissonance caused by accounts of the achievements and victories of the British military and the firsthand accounts of returning individuals and of writers such as the war poets.

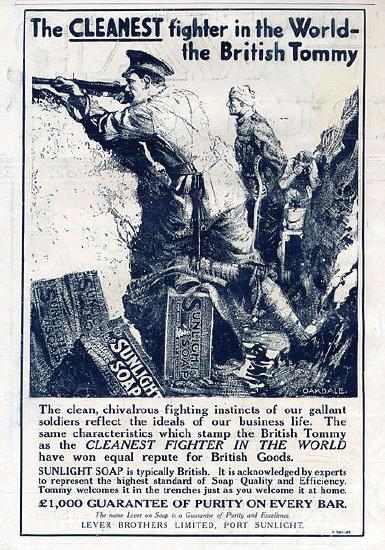

No words could describe the general public’s perception of World War I better than the photo essay at the Modern American Poetry website (Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). In the photo essay note the first pictures of men going off to war, women cheering them on, both sides confident in their abilities and confident that the war would be over within a few months followed by increasingly somber pictures of the reality. The ad pictured here capitalized on the widespread belief that British troops, because they were honorable, chivalrous, gallant, would soon march home in victory. The work of soldier poets such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Rupert Brooke informed the British public of the realities of war as much as, perhaps more than, the censored journalistic reports that reached British newspapers and magazines. The brutalities of outdated military tactics used against modern weapons resulted in incomparable British losses . The war poets painted vivid pictures of the realities of war.

The BBC provides extensive information about World War I , including virtual tours of the trenches and excerpts from oral histories, diaries, and letters.

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

Wilfred Owen was born in Shropshire, a rural area of England. He was interested in poetry, particularly Keats and other Romantic poets, and wrote poetry in his teens. When he failed to be admitted to college, he moved to France to work as an English language tutor. After World War I began, he moved back to England to enlist. In 1917, he was diagnosed with what was then called shell shock and sent to Craiglockhart Hospital in Scotland for treatment. There he met Siegfried Sassoon. Both poets wrote some of their most well-known poetry while there. Owen returned to the front in the fall of 1918, won the Military Cross, and just days before the war ended was killed in battle. His family received the news of his death in the midst of celebrations on November 11, Armistice Day, 1918.

“Dulce et Decorum Est”

The Latin phrase from a work by Homer may be translated “It is sweet and right to die for one’s country.” Juxtaposed against the illusion of war as a glorious adventure, Owen paints the horrors of war’s reality.

Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori .

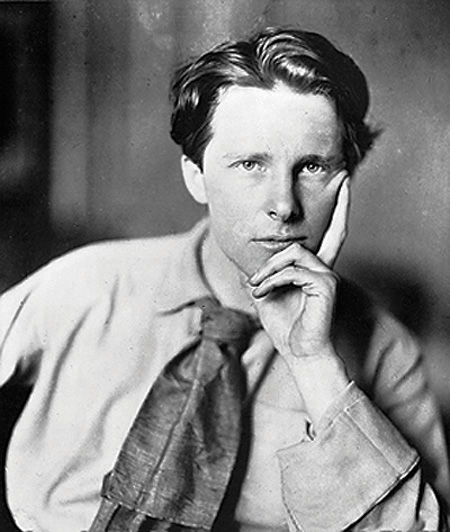

Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

Rupert Brooke also was fond of the works of the Romantic poets. He attended Cambridge University where he met and befriended members of the Bloomsbury Group whose literature was an important piece of British modernism. Brooke was commissioned into the Royal Navy, but in 1915 he died of sepsis onboard a hospital ship. He is buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

Rupert Brooke’s grave.

“The Soldier”

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967)

Although Sassoon grew up in a family divided by religious differences, his father was Jewish, his mother Roman Catholic, his background provided him enough wealth to live comfortably. He attended Cambridge University for a while, without taking a degree, preferring to live the life of a country gentlemen playing cricket and writing. Sassoon joined the British Army at the beginning of World War I; he was sent home from the front twice, once when he contracted a fever and once for shell shock, this being the occasion when he met Wilfred Owen. Sassoon survived World War I and continued writing until his death.

By George Charles Beresford, 1915

“Glory of Women”

Glory of women.

You love us when we’re heroes, home on leave,

Or wounded in a mentionable place.

You worship decorations; you believe

That chivalry redeems the war’s disgrace.

You make us shells. You listen with delight,

By tales of dirt and danger fondly thrilled.

You crown our distant ardours while we fight,

And mourn our laurelled memories when we’re killed.

You can’t believe that British troops “retire”

When hell’s last horror breaks them, and they run,

Trampling the terrible corpses—blind with blood.

_O German mother dreaming by the fire,

While you are knitting socks to send your son

His face is trodden deeper in the mud._

In the last three lines, the speaker turns from addressing the people back home in England to speak to the imagined mother of a German soldier. His comment has the effect of humanizing the political enemy.

Key Takeaways

- The staggering casualties and the horrors of modern warfare contributed to the modernist sense that the world lacks a stable, centralizing force and that life lacks ultimate purpose—that the world we live in is, in the words of Thomas Hardy’s character Tess, a “blighted one.”

- The work of the war poets helped enlighten the public about the nature of the war experience.

- In “Dulce Et Decorum Est” the last stanza is directed to people back at home. What is the purpose of this stanza?

- Read this brief description of the mustard gas used in World War I. Does Owen’s description seem realistic? Which account seems more emotionally based? Which might have had a more profound effect on the people at home away from the war?

- Brooke’s poem “The Soldier” seems brighter in mood and tone than the other two poems, and yet it describes a soldier’s death. What makes the poem less horrific than “Dulce Et Decorum Est”?

- How would you describe the mood of the speaker in “The Soldier”?

- The speaker of “Glory of Women” expresses disillusionment with the supposed glory of war. How would you describe his attitude toward the women back at home?

- In “Glory of Women,” although the Germans are the enemy of the British, what common human trait does the poet reveal?

General Information

- Anthem for Doomed Youth: Writers and Literature of The Great War, 1914–1918. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- The First World War Poetry Digital Archive . University of Oxford and JISC [Joint Information Systems Committee]. text (including biographies, primary texts, background information), images (including portraits, digital images of manuscripts, photos of World War I, images from the Imperial War Museum); audio; video (including a Second Life Virtual Simulation from the Imperial War Museum and a YouTube video introduction , over 150 video clips, film clips), and an interactive timeline.

- “ Home Front: World War One .” British History. BBC.

- “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Wilfred Owen’s ‘ Dulce et Decorum Est .’” Online Gallery. British Library. image of handwritten manuscript and information about Owen and World War I.

- “ World War One .” World Wars. BBC History .

- Poems by Wilfred Owen with an Introduction by Siegfried Sassoon . A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Pennsylvania State University.

- “ Rupert Brooke, 1887–1915 .” “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Rupert Brooke (1887–1915) .” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “ Rupert Chawner Brooke .” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “ Siegfried Sassoon .” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “ Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967) .” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “ Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) .” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “ Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) .” “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Wilfred Edward Salter Owen .” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “ 1914 V. The Soldier “ by Rupert Brooke. Representative Poetry Online . Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “ Anthem for Doomed Youth .” by Wilfred Owen. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. text and a digital image of the original handwritten manuscript.

- “ Dulce et Decorum Est .” by Wilfred Owen . Paul Halsall, Fordham University. Internet Modern History Sourcebook .

- “ Dulce et Decorum Est .” by Wilfred Owen. “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Glory of Women .” by Siegfred Sassoon. Counter-Attack and Other Poems . 1918. Bartleby.com .

- “ Glory of Women .” The War Poems of Siegfried Sassoon . Project Gutenberg .

- “ Sonnet V. The Soldier .” by Rupert Brooke. “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Wilfred Owen’s ‘ Dulce et Decorum Est .’” Online Gallery. British Library.

- “ World War I Photo Essay .” Modern American Poetry . Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- “ Dulce et Decorum Est .” by Wilfred Owen. LibriVox .

- Extract from a letter by Wilfred Owen, July 1918 . “ —the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War .” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “ Siegfried Sassoon 1886–1967 ). A Recording Owned by Mrs. Olga Ironside Wood. 1 January 1967. BBC.

- “ The Soldier .” by Rupert Brooke. LibriVox .

- “ Wilfred Owen Audio Gallery .” Dominic Hibberd. World Wars. BBC History .

Owen Sheers: war poetry

Monday 8 September 2014 | by Owen Sheers

Owen Sheers reflects on war poetry in this thought piece

‘A voice had become audible, a note had been struck, more true, more thrilling, more able to do justice to the nobility of our youth in arms engaged in this present war’

In his 1952 poem ‘The Shield of Achilles’, Auden describes Achilles’ mother, Thetis, looking over the shoulder of Hephaestus as he forges her son a shield. She does so anticipating scenes of honour, celebration and prestige: ‘vines and olive trees’; ‘ritual pieties’; ‘athletes at their games’. But instead the blacksmith God, informed with all the terrible knowledge of Auden’s twentieth century, is busy embossing the shield with scenes of war and its aftermath. ‘An artificial wilderness/ And a sky like lead’; ‘decent folk’ watching an execution; a voice proving ‘by statistics that some cause was just’; a wandering urchin ‘who’d never heard/ Of any world where promises were kept,/ Or one could weep because another wept.’ Confronted with these unflinching depictions of what war really is and means, Thetis cries out in dismay as Hephaestus, his job done, ‘hobbles away.’

For much of human history war poetry, which from a 21st Century perspective we might expect to have always have been on the side of the truth-telling Hephaestus, has more often than not contributed to a public narrative closer to Thetis’ anticipated scenes of honour and glory. Until recently poets wrote about war not because poetry was particularly well-suited to exposing and giving voice to its realities (although it is – more on that later), but rather because war was well-suited to poetry. Sacrifice, heroism, drama, loss, virtue, amputated love – for centuries wars and the men who fought them have presented poets with a fertile landscape in which to cultivate their craft. In doing so, writing narrative, elegiac or heroic verse at a temporal or physical distance from the battlefield, poets have tended to fuel the climate in which wars are cultivated rather than evoke the truth of conflict or challenge its over-simplified narratives. Dulce et decorum est, wrote Horace, pro patria mori – It is sweet and right to die for one’s country. 2000 years later, in ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, Tennyson might have lamented the blunder that sent ‘the noble six hundred’ into the valley of death, but to what extent does the poem actually move on from Horace’s statement? To what extent does it bring to life what it was like to have ridden into that futile carnage of cannonballs and shot? Were all six hundred of the Light Brigade truly noble? The wounds, the stench, the screams. The individual human stories of hope, fear, hate. All of what it was like for those men is smothered by a blanket of retrospective grandeur, Tennyson’s poetry investing the horror with a safely tragic mythic weight rather than any resonant human detail that might have punctured the propaganda of the day with lyrical authenticity.

Even the poetry that provoked the quote to which this essay is a response, the work of Rupert Brooke, failed to get close to sounding a true note of the war in which he died. A voice might have become audible, as Churchill said, but it was an old voice, not a new or a truthful one; a continuation of the centuries-old tradition of poetry being put to the service of war’s bland romantic narratives. Had he survived the infected mosquito bite from which he died and witnessed the bitter, cruel fighting of WWI, I’m sure Brooke would have come to use his poetry to try and sound such a note. As it was, however, he didn’t, so the sounding of that true note was left to others – the WWI poets we now know so well, Wilfred Owen (who famously re-occupied Horace’s statement for the common soldier), Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, David Jones, Issac Rosenberg, Ivor Gurney.

It was in the poems by these men, all of whom fought in the trenches, that British poetry finally took up the role of Auden’s Hephaestus in relation to conflict, deploying its unique literary qualities to speak truth to power and give voice to the full spectrum of the realities of soldiering. In doing so - in writing from war rather than about war – the WWI poets revealed poetry to be a stunningly effective form through which to unflinchingly render the multifaceted experience of conflict. ‘In war,’ Aeschylus wrote, ‘truth is the first casualty.’ The poets of WWI proved poetry could help keep that casualty breathing. Because they did, the nature of the poetry they wrote has since become a benchmark for what we ask from, and consider to be, the best of contemporary war poetry.

So why were these poems so successful? For two reasons, I think. Firstly, because of the qualities of poetry itself, a literary form that deals in the specific, the arresting image, and yet in which the specific is simultaneously made to resonant in the universal. A form in which the moment, in all its intimacy and context, is not just made to live, but to live on. A poem (I’ll assume we’re talking about good poetry here and follow the line of the WWII poet Keith Douglas who said there is no such thing as bad poetry, just poetry and not poetry) is both immediate and enduring, gaining special purchase in the memory through its calling upon every shade of our communicative selves – the intellectual, the emotional, the associative, the visual, the rhythmic and the musical. ‘Poetry’, as John Berger once wrote, ‘draws windows everywhere.’

In contrast, public discourses about war tend to close windows everywhere. Stories become simplified, brushstrokes become broad, alternative perspectives silenced. Amnesia and misplaced patriotism combine in a lethal cocktail to kill hundreds of thousands. Poetry is an antidote to this. A vital and vitalizing remembering through all five of our senses; a counter-tide against the distancing language of government and the military-industrial complex. Where a news report might talk of a ‘surgical strike’, a poem, working at the leading edge of language, can bring us inside the breathing, panicking, loving and hating body of the person trapped in the bombed building’s rubble, and do so with an immediacy and depth impossible to achieve in journalism, film or, I’d argue, a novel. Where the lexicon of war defuses language, poetry charges it.

But poetry has always had these qualities. So why the sudden sea-change with WWI? Because, quite simply, the poets were there and their poems were read. In the trenches the poet became the soldier and the soldier became the poet. They wrote from what they lived and saw, not from an inherited idea of war or from reported experience. And then, having been written, those poems were read. Not always immediately, but still relatively soon, and in time by a large and engaged readership.

In the years since the end of WWI we’ve seen a gradual reduction in such conflict poetry of immediate proximity reaching a wide audience. There were many excellent soldier poets in WWII who continued the tradition, and combatant poets on both sides of the conflict in Vietnam. But as, through the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, global conflicts have increasingly been fought either by professional armies or marginalized, disposed groups, so the sources of poetry written by those who’ve experienced conflict and its aftermath have drastically reduced. Similarly, the vast majority of civilians affected by conflict tend not to have access to the means to either write their experiences as poetry, or to distribute their work if they do. Lastly, we the readers, no longer go in search of these voices.

In response to this situation the last decade has seen a noticeable increase in war poetry written by poets working from primary sources – from interviews with or testimonials by those who have experienced war first hand. Such a poetry of personal testimony, with the poet becoming a conduit for another’s voice over their own, is crucial if we are to ensure that the stories of contemporary conflict are allowed to continue flowing with any vibrancy into the poetic bloodstream. But it is not enough. Poets’ access is often limited to their own cultural sphere, leading to a constriction of voices along national lines that war poetry already has a tendency to encourage. So the question and challenge facing us today is how can we make sure that a poetry of proximity, a poetry of witness that represents all of those involved, is still written from the frontlines of today’s wars? How can we give an effective poetic voice to the experience of the women Kurdish militia fighting against ISIS? The Syrian child refugee? How can we continue to marry the worst of manmade human experience with what I still believe to be the best of manmade human expression? How can we, to put it simply, keep creating poems that tell us what it is really like, while also making us think, feel, and never forget?

I don’t pretend to have the answers, but I do know we must try. Because if we don’t, then the conversation around war and its aftermath will become, by however small a degree, less articulate, less representative, the notes it sounds less true, and a world in which we continue to solve our disputes through violence, more likely.

Owen Sheers, September 2014

Related writers

Owen Sheers was born in Fiji in 1974 and brought up in Abergavenny, South Wales. He was educated at ...

- Non-Fiction

Widget Title

london book fair What we're reading Indonesia baltics Poetry Hay Festival Shakespeare Poland Literature on Lockdown Walking Cities Caribbean Unwritten Poems 14-18 Now Africa spoken word sonnets Edinburgh book festival translation Awards Trinidad and Tobago Bocas Cervantes Short Stories Women Feminism graphic novel Illustration South Africa Kuwait

Sign Up to the Newsletter

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- The ALH Review

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About American Literary History

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Works cited.

- < Previous

Poetry and the War(s)

Michael S. Begnal teaches writing at Ball State University. His essay on the World War I poetry of the Spectra group was published recently (2018). A poet as well as a scholar, his latest collections are The Muddy Banks (2016) and Future Blues (2012).

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Michael S Begnal, Poetry and the War(s), American Literary History , Volume 31, Issue 3, Fall 2019, Pages 540–549, https://doi.org/10.1093/alh/ajz022

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Three new critical monographs remind us that, when it comes to war, poets have always been political. In their respective recent volumes, Tim Dayton, Rachel Galvin, and Adam Gilbert are concerned with the ways in which poets respond not only to war itself but also the ideology and propaganda that supports it, how their work resists or sometimes replicates these scripts, and the strategies they use to construct the poetic authority to address it. These critical texts, read together, reveal that resistance to hegemonic narratives is more complicated than simply writing an antiwar poem, that subverting the narratives of war requires some knowledge of how their sociopolitical and economic algorithms function to begin with. Dayton’s study offers a model of resistance to such narratives through its revealing juxtaposition of anachronistic or propagandistic poetic rhetoric with the true nature of and motives for the US’ participation in World War I. Galvin argues for the sociopolitical validity of the work of canonical modernist poets more recently disparaged as overly absorbed in aesthetic concerns. For Gilbert, poetry is an overlooked reservoir of knowledge bearing witness to the experience of US soldiers in the American War in Vietnam.

A recent essay by poet laureate Tracy K. Smith contends that, through the 1990s, American poetry was gripped by a “firm admonition to avoid composing political poems,” but with the shock of 9/11 and the ensuing war in Iraq, “something shifted in the nation’s psyche” that sparked a renewed flowering of socially engaged political poetry. Three new critical monographs remind us, however, that, at least when it comes to war, poets have always been political. In their respective volumes, Tim Dayton, Rachel Galvin, and Adam Gilbert are concerned with the ways in which poets respond not only to war itself but also the ideology and propaganda that supports it, how their work resists or sometimes replicates these scripts, and the strategies they use to construct the poetic authority to address it. Just as Smith suggests that contemporary political poetry can be “a means of owning up to the complexity of our problems, of accepting the likelihood that even we the righteous might be implicated by or complicit in some facet of the very wrongs we decry,” so do these critical texts, read together, reveal that resistance to hegemonic narratives is more complicated than simply writing an antiwar poem, that subverting the narratives of war requires some knowledge of how their sociopolitical and economic algorithms (so to speak) function to begin with.

Dayton’s American Poetry and the First World War (2018) is unique among the works considered here in that it looks at that war and the poetry it inspired through a Marxist-materialist lens. This confers a number of advantages, one being that it provides a model for contrasting the real reasons behind the US’ entry into the war with the jingoistic discourses perpetuated in its favor that the poets whom Dayton examines (mostly) amplified. Much has been written about the disillusionment that the war engendered among high modernists like T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, among others, and Paul Fussell’s argument in The Great War and Modern Memory (1975)—that World War I introduces ironic disjuncture as the primary trope of literary modernism—still looms large (Fussell 38). Dayton’s aim is to examine how the poets often served Woodrow Wilson’s “audacious attempt to establish the United States as the hegemonic power of the capitalist world system” (15). Dayton’s clarity about the wider purpose of the war, “a contest over which nation would succeed the United Kingdom as the hegemonic capitalist power, the US or Germany,” needs to be made prominent because so much of the rhetoric, both in the popular press and in the poetry he studies here, helped to obscure the underlying economic reasons for the war, instead invoking an anachronistic millennialism or the ideology of a medievalist crusader (67).

Dayton spends much of his first chapter putting distance between his historical-materialist approach (his theoretical foundation is Marx’s base/superstructure model, as modified by Sean Creaven to include a third level, the substructure) and that of scholars like Mark Van Wienen, Cary Nelson, Walter Kalaidjian, and others, who have in recent decades championed the work of political poets formerly excluded from the modernist canon. Dayton terms these critics “left neo-pragmatists” and points out that “none of them operate from within a classical Marxist framework, despite their leftist commitment” (29). Though he presumably shares this political commitment, Dayton is particularly trenchant about Van Wienen’s Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War (1997). While acknowledging its value as a recovery project, Dayton criticizes this 20-year-old text for being content to do “cultural work,” which, he asserts, “threatens to devolve into a gross instrumentalism if it becomes a total program, rather than a way of understanding an aspect of literary (or other) works” and which, being itself “a hallmark of capitalist modernity, is something that Marxist critics as different as Georg Lukács and T. W. Adorno have fought against within Marxism” (31). This is noteworthy in that here we have a politically Marxist critic essentially saying that an overt Marxist political stance (as Van Wienen and Nelson articulate) is not intrinsically sufficient as a program of criticism because of its “orientation toward persuasion: Nelson and company often seem more oriented toward reshaping the reader’s vision of literary history than to disclosing the nature of the interaction between literature and history” (32). In other words, for Dayton, being a Marxist is all well and good, but literary criticism needs to investigate the ideological, structural, and economic forces that shape poets and poetry if it is to have any real value, for without that, “conflict thus appears more ethical than properly political” (34).

Such investigation is something that, Dayton charges, Van Wienen does not do: “ Partisans and Poets . . . never ventures to enquire into the deeper nature of the war itself, and so leaves unasked a variety of questions about the relationship between the war and literature about it” (35). It is true that Van Wienen, using the terminology of speech act theorist J. L. Austin, makes clear a bias against the modernist poetry of “locution”—“how a ‘grammatical utterance’ is produced within a particular formal network,” instead favoring partisan-political poems that foreground “illocution” or “the purpose of that utterance within a social situation” (Van Wienen 24). Yet, to be fair to Van Wienen, he does spend ample time delineating some of the deeper political and economic contexts of US involvement in World War I (18–22), as well as the ways that hegemonic discourses (in the Gramscian sense) and ideologies (in the Althusserian sense) intersect with the poetry that he chooses to discuss (30–34). Be that as it may, Dayton’s historical-materialist approach is rather comprehensive and allows him to engage with poets whose politics he clearly does not endorse, but whose work helps to illuminate the anachronistic rhetoric that often obscured the economic and political basis for US participation in World War I and the industrialized means by which its violence was carried out.

For example, Dayton devotes a whole chapter to Alan Seeger (most famous, of course, for his poem “I Have a Rendezvous with Death”), who reacted against this era of capitalist modernity by retreating into the martial ideals of “an imagined medieval world” (98). Dayton is fairly devastating in his analysis, particularly when he contrasts Seeger’s romantic embrace of war with the reality of “the machine technology characteristic of the second industrial revolution . . . applied to the business of killing people” (116). Dayton demonstrates how medievalist discourse (employed by Seeger, along with Lynn Harold Hough, Henry van Dyke, William Hartley Holcomb, and Edward S. Van Zile) was marshaled in support of the US’ business interests: “Indeed, insofar as the First World War occurred within, not against, capitalist modernity and is a part of its unfolding dynamic, medievalism was largely incorporated by the social forces it scorned, providing Seeger and others with vital self-deceptions that helped enable one of modernity’s greatest atrocities” (117). Despite Seeger’s popularity during the war years, Dayton observes that there were other poets who refused to buy into the vision he put forward in “I Have a Rendezvous with Death.” In 1918, Haniel Long (perhaps best known for his 1935 documentary political poem Pittsburgh Memoranda , which preceded and likely influenced Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead [1938]) published a sonnet titled “Seeger,” which deflates the heroism of its subject and thus, as Dayton observes, “avoids the high diction of war” (143). Such toggling back and forth between writers known and until-recently forgotten (and those somewhere in the middle), between those who wrote in popular, genteel, or even high-modernist styles, provides a more holistic understanding of the historical context of the poetic response in the Great War period, where the nonetheless valuable work of Fussell, Van Wienen, et al. is more concerned with either making or unmaking the canon of modernism.

Accordingly, Dayton’s analysis of E. E. Cummings’s war poems “next to of course god america i” and “my sweet old etcetera” returns him to contending with Van Wienen, whom Dayton criticizes for “inadequately characteriz[ing] and, perhaps as a consequence, undervalu[ing] the exact nature of Cummings’s response to the war” (223). Though Cummings is nowhere actually mentioned in Partisans and Poets , it is true that he would likely be lumped in with those modernist poets of locution and individualism whom Van Wienen rejects from the scope of his criticism. As a Marxist critic, however, Dayton looks to Adorno’s defense of lyric poetry for its role in revealing “the ineluctably dialectical nature of the individual-social relation” (241). For Dayton, the linguistic experimentation in the Cummings poems remains socially engaged because it satirizes the public discourse that justifies and supports a capitalistic war effort (with “next to of course god america i” exposing the idiocy of jingoistic nationalism and “my sweet old etcetera” attacking the familial pieties of the home front). At the same time, he notes in his conclusion the contradictory situation in which modernist literature itself did have “a profound political and social character as a commentary on the decisive event of the twentieth century,” yet also became largely reactionary and, with the advent of New Criticism, sought to unmoor itself from its sociohistorical context (250). Such contradictions may be further illustrated in the fact that Cummings later became a right-wing conservative, sympathetic to the anti-Communist ideologue Joseph McCarthy (Sawyer-Lauçanno 505).

… many of the texts I analyze have been criticized as too hermetic in comparison with the ostensible transparency of politically committed poetry and, censurably, as being disengaged with politics in a time of crisis. I argue, however, that these poets’ rhetorical strategies reveal an ethically motivated self-scrutiny about the use of language in wartime. (9)

Here her modus operandi is not unlike Dayton’s rhetorical approach to Cummings. This is not to say that the broadly antiwar stances of Stevens, Moore, and Stein (or, as noted, Cummings) make their conservative politics especially palatable to anyone on the left—for example, Galvin makes clear Stein’s support of the Vichy head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain and suggests that if her translations of his speeches, intended to “trumpet Pétain’s texts to Americans,” had been published, “Stein likely would have been considered a collaborator” (279). Instead, Galvin focuses on what she terms their “meta-rhetoric,” which she defines as “the self-reflexive use of rhetorical schemes and tropes to signal the literariness and mediated, constructed nature of a text” (22). She differentiates this from the more common practice of self-reflexivity that poets have engaged in especially from the twentieth century onward, and from the standard definition of rhetoric as persuasive writing, by foregrounding its wartime context and the mediation of the press, specifically newspaper reports from the front.

This strategy provides a means of overcoming the question of authority in a post–World War I era, where the participatory experience of the British soldier-poets (Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon, etc.) had quickly come to be seen as the ne plus ultra of war writing. Yet no such anxiety prevented numerous noncombatant poets on both sides of the Atlantic, before, during, and immediately after the Great War, from commenting on it in poetic form (as the work of both Dayton and Van Wienen clearly demonstrates). In his critique of Fussell, Van Wienen decries the way “that British World War I poetry becomes not only the starting point for a canon of war literature that is decisively opposed to war, but also the origin of modernism,” which also had the effect of devaluing the authority of civilian, often female poets (26). Nonetheless, such views very quickly took hold. Indeed, Galvin observes that Auden, though too young to have fought in World War I, carried a sense of guilt about his lack of war experience and worshipped the authenticity of Wilfred Owen (103–8), while Marianne Moore famously came in for a savage attack from Randall Jarrell for her poem “In Distrust of Merits,” in which she, as a woman who would not have been allowed to participate in combat even if she had wished to, dared to speak as a civilian of the suffering of war (266–72). Galvin takes up Auden’s phrase “the guilt which every civilian must feel at not being in the fighting line” to describe the problem many of these poets faced (12). Meta-rhetoric, she asserts, allows civilian poets to comment on events that they have not observed firsthand by admitting their own lack of combat experience, or “flesh-witnessing” (Galvin borrows this term from Samuel Hynes), paradoxically creating one kind of authority by exposing the lack of another.

Galvin does not deal in any length with the causes of or discourses surrounding World War II, aside from stating that it was a continuation of previous conflicts (104–6, 258). The varying, often conservative politics of the modernist poets she takes up notwithstanding, insofar as they all seem to arrive at a broadly antiwar position, speaking out in meta-rhetorical ways against the brutality of it, raises the question of exactly what broader ideological frameworks the poets were either supporting or resisting. From our vantage point, we commonly view World War II as the “Good War” heroically waged against fascism, and in some respects of course that is true. Yet at the time, as historian Kenneth D. Rose reminds us, in the run-up to and throughout the war, Americans had no clear picture of its purpose or their role in it. Indeed, he observes, there was “little in the way of flag-waving patriotism among ordinary Americans, and even less in the way of a rationale for taking part in the war in the first place,” going on to explain that this was in large part to do with the memory of the carnage of World War I, for “it had been appeals to American idealism and patriotism that had led to U.S. participation in that earlier catastrophe” (61). Thus, it seems that the poets that Galvin analyzes, Auden, Moore, Stein, and Stevens especially, whatever their individual politics, are writing out of a kind of cynicism about war in general and the resulting senseless violence. As Rose further writes, “The lack of an informing ideology seemed to affect the entire society,” and the sometimes wry tone of these civilian poets roughly mirrors that of soldier-poets like Jarrell and Karl Shapiro (64).

One wonders, then, if all the civilian poets under consideration here really felt as much guilt (per se) about their lack of flesh-witness as Auden did, given the overall lack of enthusiasm for participation. To look at it another way, Moore was already in her fifties during World War II and had no choice but to observe the unfolding of events through the mediation of the press. In any case, the issue of how to write about a war one has not seen firsthand was definitely a concern. Galvin makes the point that, in “In Distrust of Merits,” Moore already “anticipates responses from later critics such as Jarrell” by “articulating occluded vision, the problem of the observer at a distance who is not a flesh-witness” (262). This not only makes Jarrell’s attack all the more unwarranted but gives new insight to Moore’s broader poetics, which Galvin observes “often acknowledge that they are inextricable from discursive structures within which they are born,” but which is “intensified in her poems that respond to news of war” (261). Stein goes so far as to use the title Wars I Have Seen (1945) for the multigenre text that Galvin analyzes as an “anti-newspaper,” and in a sense it is apt (280). Despite (or perhaps because of) her accommodationist approach toward the Nazi occupation of France (and even her own home), Stein did have a kind of firsthand experience of the war: “Living in a country occupied by a hostile military certainly counts as witnessing war, and for innumerable noncombatants, wartime means precisely what Stein describes: waiting, worrying, working, stockpiling food, seeking news, gathering rumors, anticipating violence” (Galvin 286). Her use of meta-rhetoric involves her “pressing upon the question of what is ‘real,’” which may or may not resemble a possible response to the experience of battle (290). Certainly, the irony or disjuncture that Fussell emphasizes as the hallmark of the British soldier-poets could impart a feeling of unreality, but in those poems, it always emerges as a result of the horror experienced directly.

At the same time, the authority of flesh-witnessing is not in itself unassailable. As we have seen, Dayton argues that Seeger, a combatant eventually killed in action in World War I, deployed poetry as part of an elaborate “self-deception” about that war. The absurdity of Rupert Brooke’s simile of young men volunteering for battle “as swimmers into cleanness leaping” has been widely remarked (4). In defending her focus on civilian-authored war poetry, Galvin avers that “flesh-witnessing has certain dangers as an episteme”; “the risk is that it will help perpetuate an idealization of experience that obstructs empathy and forecloses political debate” (15). Largely avoiding these dangers, however, Gilbert examines the work of the US soldier-poets who actively participated in the American War in Vietnam. His study, A Shadow on Our Hearts: Soldier-Poetry, Morality, and the American War in Vietnam (2018), thus excludes certain significant figures such as John Balaban (a conscientious objector who served as a medic in Vietnam) because its stated focus is “on a group of people whose participation in, and perpetration of, the violence of the war provides them with a particularly interesting and potentially insightful vantage point from which to view the conflict’s moral issues” (8). Gilbert asserts that his study is not meant to be taken as a literary analysis; the many poets and poems that he reads (with particular attention paid to W. D. Ehrhart, Bruce Weigl, Yusef Komunyakaa, David Connolly, and Dick Shea) illuminate intersecting moral and historical questions. For Gilbert, this body of poetry is an overlooked reservoir of knowledge bearing witness to the experience of US soldiers in Vietnam.

Drawing on the work of moral historian Jonathan Glover rather than Marx, Gilbert, like Dayton, also relies heavily on Adorno as well as the further insight of Albert Camus’s philosophical text The Rebel (1951). As in Dayton’s study, Gilbert puts forward a view of the Vietnam War as “an imperialistic inheritance,” driven forward by the profit motive of large corporations (214). The poets he analyzes on this aspect of the war (Connolly, Lamont Steptoe, Steve Mason) are particularly scathing. The poets’ accounts of killing and their frequent depiction of American atrocities suggest an answer to Adorno’s famous declaration that “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” (qtd. in Gilbert 29). Adorno himself later gave nuance to this pronouncement, Gilbert points out, and then adds to it with his claim that “ there is no longer beauty or consolation except in the gaze falling on horror, withstanding it, and in unalleviated consciousness of negativity holding fast to the possibility of what is better ” (qtd. in Gilbert 29, Gilbert’s emphasis). In this light, Gilbert reads the work of Weigl and Ehrhart especially as a kind of atonement for the moral wrongs of the war and a rejection of the politics and discourses (for example, of patriotism, masculinity, race) supporting it.

Also in light of the aforementioned Adorno passage, perhaps, much of this poetry only foregrounds flesh-witnessing in a direct, confessional style, neither needing to engage in elaborate strategies of modernist meta-rhetoric nor wishing to construct, like Seeger, romantic or idealistic justifications of militarism. Aside from language itself, there is no mediation between direct experience and the page. Gilbert contends that these poets “show little desire for detachment but rather a strong resolve to enter into an engaged relationship with the world through their poetry” and quotes Weigl’s lines, “I can’t abide / by words that simply decorate” (29). Of course, this further reinforces these poets’ ethos of moral authority, but it is also an interesting contrast to the treatment of the American War in Vietnam in other genres of art, like film (especially Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now [1979] and Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket [1987]), Michael Herr’s journalistic novel Dispatches (1977), and the fiction of Tim O’Brien, which often rely on postmodern strategies of disjuncture that blur the lines between reality and perception. Indeed, Fredric Jameson called the American War in Vietnam the “first terrible postmodern war,” which created a “breakdown of all previous narrative paradigms . . . along with the breakdown of any shared language through which a veteran might convey such experience” (44). Eric Gadzinski, for one, makes a tentative case for Weigl’s work as postmodern in the way that the “decentering transparency of” the trauma of the past intrudes upon the speaker’s sense of the present, destabilizing it (137), but, for Gilbert, the poetry’s direct style, which ethically lets its gaze fall on the horror without aestheticizing it very much, is also what allows it to be treated as a historical archive.

In this manner, given the still-ongoing wrangling over the causes and meaning of the US war in Vietnam, Gilbert’s book is a useful counterpoint to another recent recasting of its history, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s documentary series The Vietnam War (2017). Both works centralize the testimony of soldier participants (Ehrhart appears in both), yet each makes a different argument. Even though Burns and Novick attend to the colonialist roots of the conflict, they seem intent on justifying the US involvement in Vietnam while belittling the antiwar protesters at home, whom they too often portray as either naïve fools or violent thugs. In contrast, Gilbert’s study demonstrates that many Vietnam veterans—at least those who became poets—actively supported civilian antiwar protestors “as the group of Americans who actually fulfilled their responsibility by attempting to end the war” (239). Furthermore, many even came to sympathize with the cause of the Vietcong. Gilbert registers “the widespread belief among the poets that the Vietnamese revolutionaries were fighting for a moral cause; just as there is little in the poetry that blames the revolutionaries, there is rarely any suggestion that they were fighting in anything other than a justifiable campaign” (200). Thus, we see poetry taking an active role in a debate of great political import and instantiating an ethical response to a morally repugnant war.

As contemporary poets consider strategies for engaging with and possibly resisting the US’ … perpetual, low-level … warfare throughout the Middle East and around the globe … these three scholars offer key signposts for navigating that process.

Brooke Rupert. “Peace.” Poetry , vol. 6 , no. 1 , April 1915 , p. 18 .

Google Scholar

Burns Ken , Novick Lynn , directors. The Vietnam War . PBS , 2017 .

Google Preview

Dayton Tim. American Poetry and the First World War . Cambridge UP , 2018 .

Fussell Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. 1975 . Oxford UP , 2013 .

Gadzinski Eric. “Bruised Azaleas: Bruce Weigl and the Postwar Aesthetic.” The Vietnam War and Postmodernity , edited by Bibby Michael , U of Massachusetts P , 1999 , pp. 129 – 40 .

Galvin Rachel. News of War: Civilian Poetry 1936–1945 . Oxford UP , 2018 .

Gilbert Adam. A Shadow on Our Hearts: Soldier-Poetry, Morality, and the American War in Vietnam . U of Massachusetts P , 2018 .

Jameson Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism . Duke UP , 1991 .

Leavell Linda. Holding On Upside Down: The Life and Work of Marianne Moore . Farrar , Straus and Giroux , 2013 .

Rose Kenneth D. Myth and the Greatest Generation: A Social History of Americans in World War II . Routledge , 2008 .

Sawyer-Lauçanno Christopher. E. E. Cummings: A Biography . Sourcebooks , 2004 .

Smith Tracy K. “Political Poetry Is Hot Again: The Poet Laureate Explores Why, and How.” The New York Times Book Review , 10 Dec. 2018 . Web .

Van Wienen Mark W. Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War . Cambridge UP , 1997 .

Author notes

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-4365

- Print ISSN 0896-7148

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An Introduction to English War Poetry

The poet’s career doesn’t end once he dies. The soldier’s career arguably does. The poet-soldier, then, has died physically, but what remains of him is his art. Both Edward Thomas and Francis Ledwidge managed to create something that transcended their persons and lasted long after being killed in war.

One of the greatest contributions to modern English poetry came through the works that described World War I, in great part because of WWI’s significance on human history. Poetry written by soldiers is one of the best ways to approach literature on the subject, and it will be the focus of this essay to introduce two war poets, one Englishman and one Irishman, who conveyed the sense of being a soldier in the Great War and, in turn, were transformed by this event. Edward Thomas and Francis Ledwidge were two such poets whose pieces drew upon elements of nature to communicate a soldier’s isolation and his acceptance, even embrace, of imminent death. These two poets were common men, and sometimes within the canon of English and Western literature we may forget that there were talented writers of value even if they did not reach international renown. Many times, it is only through the art of small men that we can understand the impact of the forces that we create and that envelop us as they grow out of control.

Edward Thomas was an English poet born in 1878. He enlisted as a soldier at the age of thirty-seven in 1915 and was killed, after two years of training, on the first day of battle in Arras, France in 1917.[1] Francis Ledwidge, born in 1887, enlisted as a soldier in 1914 at the young age of twenty-seven and was killed three years later in Boezinge, Belgium.[2] Though both of these men wrote several poems inspired by their experiences fighting during the Great War, they were not concerned with the war as a political or controversial topic. In fact, those familiar with war poetry might wonder why I don’t mention better-known WWI poets, like Wilfred Owen. All soldiers were diverse people who understood war differently. Owen had one of the most explicit critiques of war, and I think most of his fame came from that political statement. Take his most famous poem, “Dulce et Decorum Est,” the message of which can be understood from a first reading:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs, And towards our distant rest began to trudge. Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots, But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time, But someone still was yelling out and stumbling And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.— Dim through the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace Behind the wagon that we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin; If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,— My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori .

The poem is moving, no doubt, because it is a true depiction of war. Even in his blunt description of battle, Owen manages to describe death in beautiful verse, “Dim through the misty panes and thick green light / As under a green sea, I saw him drowning” (13-14), followed by a nightmarish description of the image that haunts him in his sleep. The moral of the story? It is a lie, that it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country. Owen’s message resonated with many anti-war activists, and this statement is not meant to detract from what is an exceptional poem with intricate literary devices (just read the first two lines out loud! Alliteration, assonance, almost onomatopoeic, making the sound of soldiers marching—amazing). But I do think Owen’s political message has influenced his appreciation as a poet as being more for his message, not for his poetry .

What I prefer about the lesser-known war poets is the humility of their voice, which is more preoccupied with coming to terms with themselves as soldiers, as the helpless victims of circumstance, rather than criticizing the world for what’s happened to them. What Thomas and Ledwidge seemed to understand was that during times of war wherein a soldier found himself lost and alone, it was man’s relationship with himself that took priority over everything else. While the spirit of the soldier who sacrifices himself for others is revered, I do believe that, internally, what took place in the minds of these soldiers was a necessary form of isolation that turned into self-reflection. This excerpt of a letter from Ledwidge to a woman named Katherine conveys a similar sentiment to Owen’s poem, but in a very different tone:

If I survive the war, I have great hopes of writing something that will live. If not, I trust to be remembered in my own land for one or two things which its long sorrow inspired… You ask me what I am doing. I am a unit in the Great War, doing and suffering… I may be dead before this reaches you, but I will have done my part… I am always homesick. I hear the roads calling, and the hills, and the rivers wondering where I am. It is terrible to always be homesick. —Francis Ledwidge, Letter to Katherine Tynan, dated 6 January 1917 .[3]

It is not poetry, of course, but it was written by a poet. Notice how Ledwidge says that if he “survives,” he wants to write something that will “live.” He does not use the word “live” for himself, although we usually say, “if I live.” It is almost as though Ledwidge is recognizing that he’s already lost a part of himself. Ledwidge viewed himself as a “unit,” just going through the motions of what needed to be done. It was not on the battlefield or while doing his duty as a soldier, then, that the individual fighter contemplated himself. Their relationship with the self, then, was the solution to their loneliness and feeling of insignificance.

The machinery used during the Great War meant that infantry combat was only a secondary resource in battle, and this change in weaponry prevented the individual soldier from playing a direct part in this industrialized war.[4] People’s belief in a heroic image of one body of men fighting arm in arm was shattered upon realizing that soldiers were dying undignified and by the thousands. The question then became, what was a singular man’s place amidst such mass destruction? Truly, his identity was overcome by an agglomerate of soldiers who were treated as objects. What “greater” sense of himself could the soldier contribute to a cause devoid of greatness?

For Edward Thomas and Francis Ledwidge, the way that they contemplated their place and themselves was through their poetry, and nature was an integral part of this relationship because it was a direct way for them to envision home. Since home was seldom in proximity for the soldier, it can be deduced that he often resorted to his immediate surroundings to find comfort and reassurance. Both Thomas and Ledwidge developed this sort of companionship with nature.

Nature’s characteristic as an ongoing duality between life and death, the beauty of creation and destruction, bore resemblance to what they were experiencing on a daily basis, and they perceived it, therefore, as a reflection of their own lives. Thomas and Ledwidge did not solely use nature in their poetry to recount their personal experiences, however, but they also used it to create a space of recognition for the individual faceless soldier as a method of remembrance. They used the symbol of a grave to manifest this sentiment.

The Grave Symbolic for Death and Life

Since there were no number of graves that would suffice for the number of casualties in the Great War, the grave as it was used by these two poets is a symbol for what it represents. In the case of Edward Thomas, the grave as a symbol of remembrance was more important than the physical tombstone. He did not mention graves in his poems, nor did he describe or reference them. Thomas’ focus on the grave was on the writings that would commonly go on the tombstone, and he replicated them in lyrical structure and form in his verses. This elegiac form, often meant for epitaphs, is common in several of his poems.[5] Thomas saw a contrast with epitaphs since they represented what was fixed but also what was transcendent, and he even attributed a literary value to them.[6] An example of such a poem is titled, “In Memoriam (Easter 1915)”:

The flowers left thick at nightfall in the wood This Eastertide call into mind the men, Now far from home, who, with their sweethearts, should Have gathered them and will never do again. (1-4)

This poem, written in iambic pentameter with an alternating end-rhyme, is typical of an elegiac stanza, which is a fitting style based on the content of Thomas’ piece since it is a poem of remembrance for the men who left for war and did not return. Nature is immediately invoked when Thomas mentions the flowers “left thick at nightfall in the wood” (1) that should have been gathered by the young soldiers and their sweethearts. Thomas acknowledges that seeing the life of the flowers that have not been picked calls to mind the death of the soldiers: the presence of one thing represents the absence of another.

Thomas used the flower as a symbol of both remembrance and impermanence to recall the past, note the present, and contemplate the future. The importance of nature in the poem might be further stressed upon considering that Thomas used un-plucked flowers in the woods as the main subject. It is only upon seeing the flowers that he is reminded of the dead soldiers. Rather than addressing the dead soldiers directly, Thomas prefers to invoke them through nature even though the poem, as the title expresses, is meant to be an elegy or epitaph of some sort for the men who died in war.

Another poem that expresses this notion of the grave as a point of convergence for death and life is “A Soldier’s Grave” by Francis Ledwidge. It bears some similarity to “In Memoriam (Easter 1915)” since flowers are also mentioned and used as a symbol of remembrance, but the flowers are only secondary to the greater symbol that is the actual earth-grave, which is the main subject of the poem. Here, however, the grave is one with nature, or, rather, the grave is a platform for nature:

And where the earth was soft for flowers we made A grave for him that he might better rest. So, Spring shall come and leave it sweet arrayed, And there the lark shall turn her dewy nest (5-8)

Spring is personified to depict a regenerating force that will decorate the soldier’s grave with different forms of life. A grave was made where “the earth was soft” (5), and spring will use this ground as its stage to grow new flowers and attract birds to lay their nests (8). In the context of this poem, death relieves the soldier from his burdens and even results in beauty and harmony as nature pushes the cycle forward, thus demonstrating that time continues to pass as one life ends by turning the soldier’s resting place into a display of new life. Both poets console the horrors of war with the beauty of nature and portray nature as playing an active role in death and life. By attributing these characteristics to nature, Thomas and Ledwidge are displaying self-awareness in their role as a soldier. They hint, likewise, at their acceptance of death since their poems display a similar disposition towards mortality, where the thought of dying comes no longer as a fear, but as a part of nature.

The Notion of “Passing” as Nature

Francis Ledwidge was able to depict nature as serene and personify it as a force of aid for the dying soldier. We can further analyze his poem “A Soldier’s Grave” and look at the first stanza to corroborate this point:

Then in the lull of midnight, gentle arms Lifted him slowly down the slopes of death Lest he should hear again the mad alarms Of battle, dying moans, and painful breath (1-4)

With his opening line, Ledwidge immediately assumes a narrative tone, which serves to calm the reader since the poet sounds like he is telling a pleasant story that is taking place in a tranquil setting, “the lull of midnight” (1). The simple alternating end-rhyme scheme enhances this emotion as each stanza concludes in such a way that sounds complete, and the word-choice (lull, gentle, lifted, slowly) reassures the reader that what is happening to the soldier is a good thing rather than a negative one. In terms of the story that Ledwidge is telling, an unknown entity is introduced whose role is to ease the soldier’s passing and carry him peacefully towards death: But the reader is not told who or what it is; it is simply described as “gentle arms” (1). Though it might be difficult to infer who or what the gentle arms refer to, Ledwidge seems to imply that the entity is a gracious and sympathetic one since it is taking the soldier away from “the mad alarms of battle, dying moans, and painful breath” (3-4).

Francis Ledwidge briefly mentioned the journey from life towards death in “A Soldier’s Grave” when he describes the soldier being lifted down death’s slopes (2). Edward Thomas elaborated on this journey to a greater extent in “Lights Out,” which was written by Thomas in 1916 just before going to war.[7] The poem is about the process of dying, and he describes this gradual passing, which he calls a sleep, by relating it to walking in a forest. The presence of nature here plays a distinct role: It is no longer a kind and sympathetic force as Ledwidge portrayed in his poem; rather, Thomas depicts it as intense and inescapable:

I have come to the borders of sleep, The unfathomable deep Forest where all must lose Their way, however straight, Or winding, soon or late; They cannot choose.

Many a road and track That, since the dawn’s first crack, Up to the forest brink, Deceived the travelers, Suddenly now blurs, And in they sink. (1-12)

Nature, here in the form of a forest, is bottomless; if sleep were a land, Thomas describes the borders of this realm as abysmal since he chooses to break the sentence at a moment where the sentence reads, “I have come to the borders of sleep / The unfathomable deep…” (1-2) It is only after continuing the poem that Thomas reveals a forest that is inevitable; “where all must lose their way, however straight or winding, soon or late; they cannot choose” (3-6). Considering the conditions and timing under which Thomas wrote this poem, prior to going to war and a year before his death, we can assume that Thomas used sleep to refer to death and the forest as a metaphor for the passing. The two symbols of sleep and the forest combined emphasize the inevitability of death since Thomas explains that everyone will eventually succumb to this sleep regardless of the path they take. All the roads and tracks that “deceived” travelers, perhaps into thinking death would not come for them, blur at the forest brink. That forest is a whole wherein they sink: A deep sleep.

Nature, in this respect, has tricked and captured the traveler wandering through the forest, which might cause the reader to view nature as a negative force. The subsequent stanzas, however, rectify this false assumption as Thomas defends the forest as being a neutral place where all emotion is distilled and where the traveler can rid himself of all earthly cares:

Here love ends, Despair, ambition ends; All pleasure and all trouble, Although most sweet or bitter, Here ends in sleep that is sweeter Than tasks most noble.

There is not any book Or face of dearest look That I would not turn from now To go into the unknown I must enter, and leave, alone, I know now how. (13-24)

It is interesting to note that Thomas describes death as neither good nor bad: both pleasure and trouble end, both love and despair (1-3). The fourth stanza in the poem indicates a type of personal relief in death that is incomparable to any worldly joy. “Face” (20) in this context represents any family or friend that would normally keep Thomas from dying, while “book” (19) might be a symbol for any moral, intellectual, or philosophical code of ethics that might make a man believe that it is better to continue living. Alternatively, it could be a metaphorical representation of literature and of Thomas’ potential career as a literary figure, since he was a well-reputed writer and book reviewer before he enlisted in the army. Thomas determines, nonetheless, that neither will stop him from entering the unknown.

In the fifth and final stanza of the poem, Thomas returns to his nature imagery and completes a cycle not only in the mechanical structure of the poem as he brings back the image of the forest, but also in a metaphorical sense since he concludes by expressing the embrace of death as a release from the self and a unification with nature:

The tall forest towers; Its cloudy foliage lowers Ahead, shelf above shelf; Its silence I hear and obey That I may lose my way And myself. (25-30)

There is a clear contradiction when Thomas states that he is able to “hear” (28) the forest’s silence and that this absence of sound is what persuades him to obey it. It is as though the forest did not need to do anything to convince Thomas to comply; rather, the impulse to follow it comes intuitively and subconsciously. While the forest seems to overpower Thomas as “its cloudy foliage lowers” (26) over him and beckons him to venture deeper, Thomas simultaneously displays free will and choice by acknowledging the fact that in so doing he will lose his path in the forest and ultimately himself (30). The facts that Thomas senses an invitation from the forest, that he understands what he must do without the need for an audible command or signal, and that he is well aware of the consequences, serve to support the idea that he views passing to be almost instinctive and part of nature.

By placing such an emphasis on dying while concurrently using nature as a metaphor and analogy to describe the process, Thomas and Ledwidge affirm an instinctual connection between their deaths and their environment. For both of these poets, the transience of nature was a way to understand and justify their role as a soldier likely to die at any moment. Thomas’ poem opens the important subject of English WWI poetry: the self.

The “Self” and Individual Life

Although the previous poems might insinuate that Thomas and Ledwidge had accepting dispositions towards death, they wrote other poems on the matter that conflicted with the notion of them having one view of death. The thought of death might have served as alleviation for these poets, but it did not resolve many questions in regard to their place amidst the Great War, after all. Their poetry was the attempt to validate the life and death of the soldier more than it was an outward critique on war. Thomas and Ledwidge placed a heavy importance on the “self” and the individual life of the soldier as he lived and suffered the war, for this experience tremendously affected his perception of the world, of life, and of death. From the traumatizing events that they endured, an existential question correspondingly arose and troubled the soldier’s mind: were his efforts and his death justified? Would he ever have recompense for his efforts, even after death? Francis Ledwidge addressed these questions in one of his most famous poems, “Lament for Thomas MacDonagh.” MacDonagh was a revolutionary leader during the 1916 Easter Rising who was executed by the British Army.[8] Ledwidge wrote a poem in his honor where he revealed his thoughts on the individual who sacrificed his life and died for a greater cause: