- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Boston Massacre

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Boston Massacre was a deadly riot that occurred on March 5, 1770, on King Street in Boston. It began as a street brawl between American colonists and a lone British soldier, but quickly escalated to a chaotic, bloody slaughter. The conflict energized anti-British sentiment and paved the way for the American Revolution.

Why Did the Boston Massacre Happen?

Tensions ran high in Boston in early 1770. More than 2,000 British soldiers occupied the city of 16,000 colonists and tried to enforce Britain’s tax laws, like the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts . American colonists rebelled against the taxes they found repressive, rallying around the cry, “no taxation without representation.”

Skirmishes between colonists and soldiers—and between patriot colonists and colonists loyal to Britain (loyalists)—were increasingly common. To protest taxes, patriots often vandalized stores selling British goods and intimidated store merchants and their customers.

On February 22, a mob of patriots attacked a known loyalist’s store. Customs officer Ebenezer Richardson lived near the store and tried to break up the rock-pelting crowd by firing his gun through the window of his home. His gunfire struck and killed an 11-year-old boy named Christopher Seider and further enraged the patriots.

Several days later, a fight broke out between local workers and British soldiers. It ended without serious bloodshed but helped set the stage for the bloody incident yet to come.

How Many Died After Violence Erupted?

On the frigid, snowy evening of March 5, 1770, Private Hugh White was the only soldier guarding the King’s money stored inside the Custom House on King Street. It wasn’t long before angry colonists joined him and insulted him and threatened violence.

At some point, White fought back and struck a colonist with his bayonet. In retaliation, the colonists pelted him with snowballs, ice and stones. Bells started ringing throughout the town—usually a warning of fire—sending a mass of male colonists into the streets. As the assault on White continued, he eventually fell and called for reinforcements.

In response to White’s plea and fearing mass riots and the loss of the King’s money, Captain Thomas Preston arrived on the scene with several soldiers and took up a defensive position in front of the Custom House.

Worried that bloodshed was inevitable, some colonists reportedly pleaded with the soldiers to hold their fire as others dared them to shoot. Preston later reported a colonist told him the protestors planned to “carry off [White] from his post and probably murder him.”

The violence escalated, and the colonists struck the soldiers with clubs and sticks. Reports differ of exactly what happened next, but after someone supposedly said the word “fire,” a soldier fired his gun, although it’s unclear if the discharge was intentional.

Once the first shot rang out, other soldiers opened fire, killing five colonists–including Crispus Attucks , a local dockworker of mixed racial heritage–and wounding six. Among the other casualties of the Boston Massacre was Samuel Gray, a rope maker who was left with a hole the size of a fist in his head. Sailor James Caldwell was hit twice before dying, and Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr were mortally wounded.

Boston Massacre Fueled Anti-British Views

Within hours, Preston and his soldiers were arrested and jailed and the propaganda machine was in full force on both sides of the conflict.

Preston wrote his version of the events from his jail cell for publication, while Sons of Liberty leaders such as John Hancock and Samuel Adams incited colonists to keep fighting the British. As tensions rose, British troops retreated from Boston to Fort William.

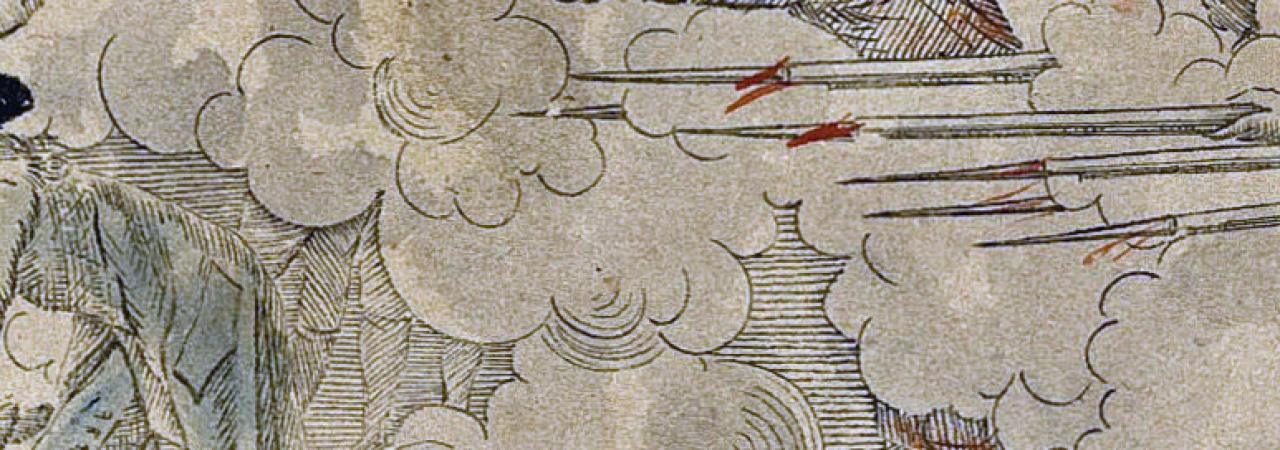

Paul Revere encouraged anti-British attitudes by etching a now-famous engraving depicting British soldiers callously murdering American colonists. It showed the British as the instigators though the colonists had started the fight.

It also portrayed the soldiers as vicious men and the colonists as gentlemen. It was later determined that Revere had copied his engraving from one made by Boston artist Henry Pelham.

John Adams Defends the British

It took seven months to arraign Preston and the other soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre and bring them to trial. Ironically, it was American colonist, lawyer and future President of the United States John Adams who defended them.

Adams was no fan of the British but wanted Preston and his men to receive a fair trial. After all, the death penalty was at stake and the colonists didn’t want the British to have an excuse to even the score. Certain that impartial jurors were nonexistent in Boston, Adams convinced the judge to seat a jury of non-Bostonians.

During Preston’s trial, Adams argued that confusion that night was rampant. Eyewitnesses presented contradictory evidence on whether Preston had ordered his men to fire on the colonists.

But after witness Richard Palmes testified that, “…After the Gun went off I heard the word ‘fire!’ The Captain and I stood in front about half between the breech and muzzle of the Guns. I don’t know who gave the word to fire,” Adams argued that reasonable doubt existed; Preston was found not guilty.

The remaining soldiers claimed self-defense and were all found not guilty of murder. Two of them—Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy—were found guilty of manslaughter and were branded on the thumbs as first offenders per English law.

To Adams’ and the jury’s credit, the British soldiers received a fair trial despite the vitriol felt towards them and their country.

Aftermath of the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre had a major impact on relations between Britain and the American colonists. It further incensed colonists already weary of British rule and unfair taxation and roused them to fight for independence.

Yet perhaps Preston said it best when he wrote about the conflict and said, “None of them was a hero. The victims were troublemakers who got more than they deserved. The soldiers were professionals…who shouldn’t have panicked. The whole thing shouldn’t have happened.”

Over the next five years, the colonists continued their rebellion and staged the Boston Tea Party , formed the First Continental Congress and defended their militia arsenal at Concord against the redcoats, effectively launching the American Revolution . Today, the city of Boston has a Boston Massacre site marker at the intersection of Congress Street and State Street, a few yards from where the first shots were fired.

After the Boston Massacre. John Adams Historical Society. Boston Massacre Trial. National Park Service: National Historical Park of Massachusetts. Paul Revere’s Engraving of the Boston Massacre, 1770. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. The Boston Massacre. Bostonian Society Old State House. The Boston “Massacre.” H.S.I. Historical Scene Investigation.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 3

- The Seven Years' War: background and combatants

- The Seven Years' War: battles and legacy

- Seven Years' War: lesson overview

- Seven Years' War

- Pontiac's uprising

- Uproar over the Stamp Act

- The Townshend Acts and the committees of correspondence

The Boston Massacre

- Prelude to revolution

- The Boston Tea Party

- The Intolerable Acts and the First Continental Congress

- Lexington and Concord

- The Second Continental Congress

- The Declaration of Independence

- Women in the American Revolution

- The American Revolution

- Boston, Massachusetts was a hotbed of radical revolutionary thought and activity leading up to 1770.

- In March 1770, British soldiers stationed in Boston opened fire on a crowd, killing five townspeople and infuriating locals.

- What became known as the Boston Massacre intensified anti-British sentiment and proved a pivotal event leading up to the American Revolution.

Boston, cradle of revolution

What do you think.

- Richard Archer, As If an Enemy’s Country: The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), xvi.

- For more, see Neil L. York, The Boston Massacre: A History with Documents (New York: Routledge, 2010).

- See Neil Longley York, "Rival Truths, Political Accommodation, and the Boston 'Massacre,'" Massachusetts Historical Review , Volume 11 (2009), 57–95.

- Hiller B. Zobel, The Boston Massacre (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1970), 301-302.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Drawn from MHS collections, our primary source sets promote learning in U.S. history and civics and are supported by teaching activities and guiding questions.

- Adams Family

- African Americans

- Citizenship

- Government and Civics

- NHD 2023: Frontiers in History

- Revolutionary War

- Voting Rights

- Transportation

- Early colonization and growth of colonies (up to 1754)

- Road to Revolution (1754-1775)

- Revolutionary War and a New Nation (1775-1787)

- Early Republic (1788-1815)

- Slavery, Expansion, and Reform (1816-1850)

- Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

- Industrialization, Immigration, and Empire (1876-1900)

- Progressive Era and WWI (1900-1920)

- Teacher Resources

Investigating Multiple Perspectives on the Boston Massacre

Inquiry Question 1: Although we don't know exactly what happened the night of March 5, 1770, what does the existing evidence from the Boston Massacre teach us about pre-Revolutionary America?

Inquiry Question 2: In what ways did people's political beliefs, social networks, and lived experience shape their understanding of the Boston Massacre?

The Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770

In 1768, British soldiers arrived in Boston, and lived alongside the colonists, sometimes paying to rent rooms in the colonists' houses. As British citizens, many colonists were angry to have armed regiments of the British military stationed in their city, but some colonists became friends with, and even married, soldiers.

The situation with the colonists and the soldiers grew tense and fights sometimes broke out between the two groups. One of the worst skirmishes took place in Boston on March 5, 1770. A crowd of angry colonists, some of them teenagers, gathered near several soldiers at the Custom House, where taxes on imported goods were paid. The colonists shouted insults at the soldiers and began throwing rocks and snowballs at them.

As the crowd moved forward, the soldiers opened fire. Three colonists were killed on the spot, and two others died later.

Among the dead was a Black and Indigenous sailor from Massachusetts named Crispus Attucks. Many people consider Crispus Attucks to be the first person killed in the fight for the colonies’ freedom.

Paul Revere, a Boston silversmith who was also a member of the Sons of Liberty, made a picture of the shooting and titled it The Bloody Massacre . A massacre is the killing of many people who cannot defend themselves. This event soon became known as the Boston Massacre, and gave energy to the colonists’ desire for independence from British rule.

The soldiers who were involved in the event were put on trial in Boston. They were defended by the lawyer John Adams, a future president of the United States. The British soldiers were acquitted of murder by a jury who determined that the soldiers had acted in self-defense.

Use our Image Comparison Tool to compare visual representations of the Boston Massacre side-by-side. The tool contains a total of seven engravings, along with an 1801 painting that depicts the setting of the Boston Massacre, which took place in front of the old State House on State Street (then known as King Street).

For elementary students, use this slide deck to explore the sources.

Download source set (Grades 8-12)

Customs : the government department that collects taxes on goods bought, sold, imported and exported. The “Customs House” was the building in Boston where the British government did this work, which also had a military protective presence.

Deposition : a formal recorded statement typically taken to be used in court. “Deponents” are individuals who have given this type of testimony under oath.

Propaganda : false, misleading, or biased ideas presented to an audience to gain support for a particular cause or leader. Propaganda can exist in many different forms: written, visual, verbal, etc.

Quarters : rooms that are provided for individuals to live in. In this case, “quarters” were provided for British soldiers and officers in Boston.

Regiment : a group of soldiers commanded by a colonel, who has supporting officers each in charge of smaller sub-groups of soldiers called companies. At this time, a standard British regiment had between 500-800 soldiers in it.

Siege : a military operation where an army tries to capture an area or town by surrounding it and stopping the movement of people / food / supplies.

Testimony : a formal recorded statement typically taken to be used in court.

Analysis Questions

Who is telling this account of the events surrounding the boston massacre, what is the relationship between the source creator and the events of the massacre, what purpose might have led to the creation of this source, for the two pamphlets: who is compiling these accounts and for what possible purpose, do you consider parts or the entirety of this account of the events surrounding the boston massacre to be reliable why or why not, how does this account of the events surrounding the boston massacre compare to the others you have viewed.

Created by MHS staff, Abigail Portu, and Kate Bowen

View the image with a transcript of Revere's text

A view of part of the town of Boston in New England and British ships of war landing their troops. . . On Friday Sept 30 1768 the Ships of War, armed Schooners, Transports &c Came up the Harbor and Anchored round the town, their Cannon loaded a Spring on their Cables, as for a regular Siege.

British General Thomas Gage sent regiments of British troops to Boston following protests during which Bostonians destroyed government property and threatened the British-appointed Governor Francis Bernard with physical violence. The influx of 4,000 soldiers (plus families and support staff) into a city of 16,000 was seen by some Bostonians as a punishment, interpreting the British ships of war moored off Boston’s Long Wharf as a symbolic siege , and the parades of British regiments through city streets as a show of force. Others took pride in the display of British strength. At first, troops stayed on their ships. Then, they moved into tents on Boston Common. Finally, they were quartered in Faneuil Hall, or paid Bostonians to rent out space in their warehouses, spare rooms, or homes.

Citation: A View of Part of the Town of Boston in New England and Brittish [sic] Ships of War Landing Their Troops 1768 (Original engraving by Paul Revere, 1768) Facsimile print issued by Alfred L. Sewell (Chicago, 1868), Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/3051 .

Read an excerpt of Rowe's diary entries from March 5th and 6th, 1770.

5 March Monday Much snow fell too night… A Quarrell between the soldiers & Inhabitants… the 29th under the Command of Capt Preston fird on the People they killed five – wounded Several Others…Capt Preston Bears a good Character--he was taken in the night & Committed…the Inhabitants [of Boston] are greatly enraged and not without Reason

John Rowe was a politically active Boston merchant who maintained friendships with many patriots and loyalists. In his diary, Rowe recorded the years leading up to the Revolution, revealing frustration with perceived British overreach and skepticism about the violence the Sons of Liberty used to advance their cause. Rowe did not witness the Boston Massacre, but recorded what he heard and thought that night, and the next day.

Citation: John Rowe diary 7, 5-6 March 1770, pages 1073, 1076-1077, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/552 .

Compare Revere's engraving side-by-side with other depictions of the Boston Massacre .

If scalding drops from rage, from anguish wrung If speechless sorrow, lab’ring for a tongue Or if a weeping world can ought appease The plaintive ghosts of victims such as these The patriot’s copious tears for each are shed A glorious tribute which embalms the dead… The unhappy sufferers were Mesr’s Sam’l Gray, Sam’l Maverick, James Caldwell Crispus Attucks, & Patr. Carr Killed Six wounded; two of them (Christ’r Monk & John Clark) mortally.

Before the end of March 1770, Paul Revere created and published this engraving of the Boston Massacre based on the original drawing by Henry Pelham. This piece was printed throughout the colonies and remains one of the most famous images of the American Revolutionary Era. The scene is generally considered by historians to be historically inaccurate and instead a piece of propaganda against the British military. For example, Revere changed the sign for the “ Customs House” where the British government housed officials and conducted much of their business to read “Butcher’s Hall.”

Citation: The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regiment, Hand-colored engraving by Paul Revere, Boston, 1770, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/151 .

Read the cover page in simplified language (Google slide)

A Short NARRATIVE OF The horrid Massacre in BOSTON, PERPETRATED In the Evening of the Fifth Day of March, 1770, BY Soldiers of the XXIXth Regiment ; WHICH WITH the XIVth Regiment Were then Quartered there ; WITH SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE STATE OF THINGS PRIOR TO THAT CATASTROPHE.

James Bowdoin, Samuel Pemberton, and Joseph Warren (all of whom were then Boston selectmen at the time and active members of the Sons of Liberty ) collected ninety-six depositions within two weeks of the Boston Massacre. They published this pamphlet as a narrative, followed by the first-hand accounts. Copies were sent to England and distributed throughout the colonies to share their perspective on the events of March 5, 1770.

Citation: A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston..., Edes and Gill (Boston, 1770), Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/337 .

Read the cover page in simplified language (Google Slide)

A FAIR ACCOUNT OF THE LATE Unhappy Disturbance At BOSTON in NEW ENGLAND; EXTRACTED From the DEPOSITIONS that have been made Concerning it by PERSONS of all PARTIES

Led by Lieutenant Colonel William Dalrymple of the 29th Regiment , British officers collected thirty-one witness testimonies after the Boston Massacre and shipped them to England. London lawyer Francis Maseres used those testimonies to write the narrative of events featured in this pamphlet, providing King George III and the British people with their first perspectives of the event.

Citation: A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England, printed for B. White (London, 1770), Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/386 .

Read an excerpted transcript.

Mar. 27. Joseph Whitehouse, Jane Crothers, Boston

These two pages from the marriage register of Christ Church, also known as Old North Church, record the marriage of Jane Crothers, a witness to the Boston Massacre, to Joseph Whitehouse, a British soldier of the 14th regiment , on March 27, 1770. Crothers was one of only three women who testified in the trials of Captain Thomas Preston and his soldiers. Her testimony , which was supported by others, assisted in clearing Capt. Preston of the charge of ordering his soldiers to fire into the crowd. Crothers said, “I am positive the man was not the Captain.” Instead, she said an unknown man had made the order. Her marriage to a British soldier was not mentioned during the trial.

In addition to showing the social connections between British soldiers and Bostonians, this marriage register also documents the membership and marriages of free and enslaved Black people at Old North Church.

Citation: List of marriages officiated by Rev. Mather Byles, Jr., November 1768 - February 1773, Clark's Register, 1723-1851, pages 124a and 124b, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/6505 .

Download source set (grades 8-12)

Historical Context Essay

Download source set with context and teacher directions (grades 3-5)

The Story of the Boston Massacre and the Legacy of Crispus Attucks Google Slides (grades 3-5)

Investigating Perspectives on the Boston Massacre

Background reading.

Investigating Perspectives on the Boston Massacre: Historical Context Essay

The Townshend Acts: Fall 1767

The Boston Massacre could not have happened if British soldiers were not stationed in the city. And the soldiers would not have been there if not for the Townshend Acts–and the distrust between colonists and the customs officials charged with collecting the taxes.

Following the repeal of the Stamp Act, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts on 29 June 1767. This time, the tax came in the form of a duty on imports–including paper, glass, lead, paint, and tea–into the colonies. British legislators hoped to avoid a repeat of the colonists’ furious reaction to the Stamp Act as they pondered how to generate revenue from the colonies and remind those colonies of Parliament's right to tax—and control—them. The Acts were named for Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was—as the chief treasurer of the British Empire—in charge of economic and financial matters. With the repeal of the Stamp Act, Great Britain believed it needed money to defray the expenses of governing the colonies in America. The Acts created a new Customs Commission and punished New York for refusing to abide by the Quartering Act of 1765.

In a series of twelve letters from a “Farmer in Pennsylvania” , John Dickinson argued that colonists were being taxed unjustly since they lacked representation in Parliament, which was their right as British subjects. Angry Bostonians committed themselves to nonconsumption, in which they refused to buy imported goods, and then many Boston merchants came together to agree on a policy of nonimportation, in which they refused to import the taxed goods.

When the customs commissioners accused John Hancock of smuggling and seized his sloop, Bostonians organized a protest in which they stoned commissioners’ houses and burned a commissioner’s racing sailboat on Boston Common. Boston’s rowdy protests terrified the commissioners.

By the fall of 1768, following a period of timidity and indecision by Governor Bernard, the commissioners finally felt that they had some support that could be trusted: four regiments of the British Army. General Gage (in Great Britain) had sent Governor Bernard a blank form he could use to call up two regiments from Halifax (in Canada), in addition to two regiments preparing to embark from Ireland. Bernard tried desperately to lay the blame for the request of troops elsewhere, knowing how deeply unpopular their arrival would be. (previous two paragraphs adapted from Serena Zabin's The Boston Massacre: A Family History , p.39-40)

Troops Arrive in Boston: Fall 1768

When the 14th and 29th Regiments of the British Army landed in Boston Harbor in late September 1768 (Source 1) , the Governor’s Council wanted the Regiments housed in barracks on Castle Island in Boston Harbor (7 miles by land and 3 miles by sea from the city center) but the Governor and Generals wanted the regiments quartered in the heart of Boston. Ultimately, after long negotiations, the army agreed to pay locals for the rental of private rooms and empty warehouses. For example, John Rowe rented the military one of his warehouses.

But how would colonists and soldiers get along with one another? The soldiers – some of whom arrived with their wives and children – were a varied group, with many different hopes, skill sets, and ideas.

Bostonians were a similarly varied group:

The “Sons of Liberty” was an informal network of men opposed to the Massachusetts Governor, but not all Bostonians were steadfast opponents of British power. In 1770, they were not sorted into tidy factions of loyalist and patriot; they did not yet conceive of those terms as necessarily distinct, not diametrically opposed. They were all Britons, although they did not all agree on the best way for Britain to rule. (Zabin, Introduction)

The Boston Massacre: 5 March 1770

By the winter of 1770, clashes between civilians and soldiers of the 14th and 29th regiments, the last troops remaining in Boston, had become more frequent. After a series of clashes between soldiers and workers at John Gray's ropewalks during the weekend of 2 March, many Bostonians predicted additional trouble was to come. On the evening of 5 March, a lone sentry posted in front of the Customs House – the site where officials tasked with collecting the Townshend duties worked in the daytime – was hassled by a group of teenagers. As the crowd swelled, Captain Thomas Preston led seven soldiers from the Twenty-ninth Regiment to reinforce the sentry, but he could not persuade the growing crowd to disperse. Amidst the noise and confusion, shots were fired; three civilians were killed instantly and two more were mortally wounded. Within hours of the episode, Captain Preston and his men were in jail, and townspeople immediately demanded that the troops be removed from Boston. Newspapers scrambled to report the news of the tumultuous week and its capstone event.

The Aftermath

Today, asking, “What really happened? Who yelled ‘fire’?” is a tempting, but ultimately futile question. Hundreds of accounts and witness testimonies recorded shortly after the shooting exist, so a lack of sources is not the issue. The problem arises when one begins to read the sources: In 1770, no one could agree on what happened that night either! The street was pitch-black; street lamps (lit with an open flame) would not be imported to Boston until the beginning of 1774. Observers were stationed on the street, on balconies, on doorsteps, and inside, peering through windows. People had different vantage points and obstacles blocking their line of sight. Moreover, people had different motivations, social relationships, and prior experiences that colored their perspectives that night. The wealthy merchant John Rowe, who had been born in England and immigrated to Boston in his 20s, had also long protested British tax policies; however, he also frequently socialized with and entertained government officials and high-ranking members of the military. His diary entry the night of the Massacre expressed how conflicted he felt about the event (Source 2) . When Paul Revere hastily created his engraving The Bloody Massacre (Source 3) , based on an engraving by Henry Pelham, he had already spent years as a member of the Sons of Liberty, publicly protesting British tax policies and the military’s presence in Boston (like the Source 1 image). Jane Crothers, a working-class woman and parishioner at Old North Church who witnessed the Massacre on the street, testified in court that Captain Preston had absolutely not been the person to yell ‘Fire!’ Was she influenced by the fact that she married Joseph Whitehouse , a soldier in the 14th Regiment, three weeks after the soldiers shot and killed five men? (Source 6)

Three Boston selectmen–all members of the Sons of Liberty–collected depositions from people who had witnessed the event itself, and also talked to people about interactions between soldiers and civilians in the days and weeks leading up to 5 March. They published a pamphlet entitled A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre (Source 4) in which they used the depositions they had collected to tell a story of the soldiers’ premeditated murder of unarmed colonists. The British military also collected their own set of witness depositions, which they sent back to England to be published in a competing pamphlet entitled A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance (Source 5). In each pamphlet, depositions make clear that Bostonians knew, worked with, lived beside, ang argued with the soldiers. Following the chaos of the snowy night on 5 March 1770, and the propaganda that followed in its wake, one thing was clear: some Bostonians may have liked–and even married–individual soldiers, but the presence of a standing army in Boston had to go.

Works Cited

Zabin, Serena. The Boston Massacre: A Family History (2020)

Coming of the American Revolution: Boston Massacre (masshist.org)

Close Reading Questions

- Which words/phrases in the title and/or caption of his engraving supports this reading?

- How might the size and placement of British troops and ships in the engraving have caused viewers to support Paul Revere’s point of view about the arrival of the British troops?

- What does this engraving add to your understanding of the Boston Massacre?

- How does this engraving relate to Revere’s 1770 engraving of “The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street” (Source 3)?

View Source .

- For whom does Rowe show sympathy in his description of the event? How do you know?

- How might Rowe’s social and economic position in Boston society have affected his perspective on the event?

- Do you find him credible? Why/why not?

- According to Rowe, in his entry on March 6, 1770, what were the immediate causes of the Boston Massacre? How did Bostonians react to it?

View Source.

- Paul Revere was a member of the Sons of Liberty. What elements of this engraving and caption would been compelling to the Sons of Liberty and their supporters?

- Consider both imagery and the ways in which Revere describes the victims and their deaths/injuries.

- What information does the title of this pamphlet give you about the events of March 5, 1770? What questions still need to be answered?

- What was the creators’ point of view of the event? Which words best show their perspective?

- What would you expect to learn from the narrative and depositions inside the pamphlet?

- How does the title of this source compare to the pamphlet printed in London ( Source 5 )?

- How does the title of this source compare to the pamphlet created from the pamphlet printed in Boston ( Source 4 )?

- How does this record of the marriage between a Bostonian and a British soldier challenge ideas about the general relationship between the two groups in 1770?

- How might Jane Crothers’ testimony in the trial of the soldiers have been affected by her as both a Bostonian and the wife of a soldier?

- How is a source like a church record different to analyze than a written / spoken testimony or diary entry? How can it support or challenge other sources you examine when looking at a historical event?

Read a transcript .

Suggested Activities – Elementary

Propaganda in Colonial Massachusetts handout

Propaganda in Colonial Massachusetts – Google Slides

This activity uses these two primary sources:

A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston...

A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England

Activity Overview: These sources are designed to be used before the teaching of the Boston Massacre and serve as a “hook” to develop interest in the event. The sources are both pamphlets, designed and printed by Patriots and British officials, and include recollections from people about the events of March 5, 1770. The pamphlets were distributed in the colony prior to the trials of the British soldiers.

This is designed to be a teacher-guided activity where students find sourcing information from the pamphlets and draw inferences about the creators’ purposes and points of view.

Using a Plot Diagram to teach historical events

The Story of the Boston Massacre – Google slides

Activity Overview: Using a Plot Diagram on your wall or bulletin board helps students see the path that a story follows from beginning to end. It is also a great way to reinforce elements of a story by integrating English-Language Arts skills with historical content. Using visuals on the Plot Diagram helps students, especially English Language Learners, to remember key details.

A plot diagram contains 5 elements: Setting, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, Resolution. The Google slides show how a plot diagram can be used to teach the Boston Massacre.

The Boston Massacre Close Reading: Informational Text Handout

Activity Overview:

The Close Reading handout contains two options:

- Students read and annotate an informational text to understand the context for and events of March 5, 1770.

- Students read an informational text with vocabulary supports and then write a paragraph summarizing the Boston Massacre, using three vocabulary content words in their summary.

Annotating John Rowe's diary entry Handout

Activity Overview: Students read excerpts of a Boston merchant's diary entries for March 5 and 6, 1770. Rowe did not witness the event, but writes brief descriptions of what happened the night of the event and the next day; how the townspeople reacted to the event, and how he personally felt about it. Rowe was neutral in the Revolution, and his sympathies for both the soldiers and the victims is evident. While they read, students annotate for the: setting, emotion words, and actions. This activity will help students to have a basic overview of what happened on March 5, 1770, and in its immediate aftermath, before they read conflicting witness accounts.

Witness Testimony excerpts and chart

Optional: Fire! Voices of the Boston Massacre - YouTube (8-minute video featuring historical reinterpreters presenting witness testimony)

Activity Overview: Working in groups, students read an excerpted testimony of one person who witnessed the Boston Massacre, taking notes on the witness’s identity. Then, they discuss whether the witness testimony supported the British soldiers or the Patriots, citing evidence for their claim. In a share-out, students take notes on the testimonies other groups read.

The handout includes testimonies from five diverse witnesses: a free Black man; a white woman who married a British soldier three weeks after the Boston Massacre; a white nightwatchman; a white man who was neighbors with one of the British soldiers standing trial; and, an enslaved man whose enslaver was a member of the Sons of Liberty.

Suggested Activities – High School

To engage students in the topic, teachers can begin with either a “game of telephone” or a “quick sketch” to introduce students to the idea that not all primary sources are reliable or accurate.

Overview – A Game of Telephone: Come up with a selection of short phrases or statements. They can be funny or serious, related to history or not.

Have students sit or stand in a circle or straight line. They will need to be close enough so that whispering to the person next to them is possible, but not so close that other players can hear. The teacher should show or whisper the phrase to the first student, who will then relay what they heard to the next student and so forth until the final student has heard the phrase.

Students can only whisper the phrase once to the person next to them and cannot repeat it if the message was not remembered or not clear.

The last player then says what they believe the phrase to be out loud for all to hear. (For a large class, the students can be divided into two teams and each group can be given the same phrase to start and then compare which group was more accurate at the end.)

Discuss how the phrase does or does not change and the complexities of hearing and memory when it comes to repeating word for word phrases. How might this play out in history when it comes to major events? How might this play out in the modern day / in their own lives? How is this important when it comes to analyzing primary sources?

Overview – “Quick Sketch”: Select a famous historical photograph or painting.

Provide each student with a blank piece of paper and pen/pencill.

Display the image on the front board for all the students to see. Give students 60 seconds to look at the image, but do not let them draw yet.

Then, remove the image so they can no longer see it. Ask them to recreate the image on their paper (2-4 minutes).

Put the image back up on the board and discuss. What elements of the image did all/most students include? What elements were most commonly left out? Were there any elements of the image that students exaggerated, changed, or got wrong? How might memory and describing what someone saw play out in history when it comes to major events and how might it affect primary sources we analyze?

Historical Overview

Source 3: Paul Revere’s engraving, The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regiment (masshist.org)

Source 4: A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston... (masshist.org)

Source 5: A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England (masshist.org)

Cover Art Handout

Activity Overview: After reading the historical overview and analyzing Revere’s engraving alongside the two pamphlet covers, students will create cover art to accompany one of the two pamphlets. Then, students explain why/how their image would support their chosen pamphlet.

“Deposition Excerpts” handout taken from:

- A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston... and

- A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England

Gallery Walk Worksheet

Gallery Walk Discussion Prompts

Teacher Prep: Read through the “Deposition Excerpts” document and select the excerpts to use with students to analyze the Boston Massacre. (Print-friendly versions of the quotes are available after the table in the document.)

Activity Overview: Students read the background historical overview and analyze the covers of Source 4: Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre and Source 5: A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston. Now, they are ready to dive into some of the depositions in the two pamphlets. For the gallery walk, display the selected excerpts around the room and provide students with the Gallery Walk Worksheet . Students will walk around the classroom analyzing the excerpts on their worksheet. Each of the documents gives information on a different part of the story and students will decide which perspective they believe is being supported by the document and which of the two pamphlets they believe the deposition was taken from.

At the end, students review correct answers and discuss (whole group) or write (individually) about one or more of the discussion prompts .

Boston Massacre Jigsaw Teacher Directions

Deposition Excerpts - Jigsaw Handout

Boston Massacre Jigsaw: Student Directions

Boston Massacre Jigsaw: discussion prompts

Teacher Prep:

Choose and print deposition excerpts from the handout for students to use.

Activity Overview: Students work in groups to read excerpts from the two pamphlets containing depositions from the Boston Massacre. They then summarize the topic / issue and point of view expressed in their text set. Students will also address the credibility / accuracy of the sources they examined in their summaries. After 20 minutes, each group shares out with the whole class, and takes notes on one another’s text sets. Following the jigsaw, students can continue to discuss as a class or write individually on one or more of the discussion prompts.

“Expressing Our Opinions” Worksheet

Activity Overview: Students examine all of the ways voices and opinions are expressed today in comparison to the ways that existed in 1770 Boston. Before this activity, students should read the background historical overview. As homework, students research and think about the different ways they hear/look for news today. In class, students examine the primary sources in this set (teacher can choose which the sources) and fill out the Expressing Our Opinions Worksheet . The teacher should then facilitate a class discussion, think-pair-share, or small group discussion for students to explain their thinking and opinions.

Applicable Standards

Skill Standards Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources

Analyze the purpose and point of view of each source; distinguish opinion from fact.

Evaluate the credibility, accuracy, and relevance of each source.

Argue or explain conclusions using valid reasoning and evidence

Content Standards Grade 3, Topic 6, Topic 6. Massachusetts in the 18th century through the American Revolution

Grade 5, Topic 2. Reasons for revolution, the Revolutionary War, and the formation of government

Grade 8. Topic 1. The philosophical foundations of the U.S. political system Topic 2. The development of the U.S. government Topic 4. Rights and responsibilities of citizens

US History 1, Topic 1. Origins of the Revolution and the Constitution

D2.His.4.3-5. Explain why individuals and groups during the same historical period differed in their perspectives.

D2.His.11.3-5. Infer the intended audience and purpose of a historical source from information within the source itself.

D2.His.16.3-5. Use evidence to develop a claim about the past.

D2.His.6.6-8. Analyze how people’s perspectives influenced what information is available in the historical sources they created.

D2.His.10.6-8. Detect possible limitations in the historical record based on evidence collected from different kind of historical sources.

D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

D2.His.6.9-12. Analyze the ways in which the perspectives of those writing history shaped the history that they produced.

D2.His.10.9-12. Detect possible limitations in various kinds of historical evidence and differing secondary interpretations.

Use the Image Comparison Tool to compare engravings of the Boston Massacre in the MHS collections side-by-side.

Images include:

- State Street, 1801 : James Brown Marston's painting depicts the site of the Boston Massacre, in front of the old State House (then known as the Town House). "King Street" was renamed "State Street" in 1784, following the end of the Revolutionary War.

- Bingley engraving : Published by W. Bingley of London, it was based on Henry Pelham's original print and originally designed as the frontispiece for the pamphlet A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre. It was also sold separately.

- Dilly engraving : Based on Henry Pelham's, this engraving was used as the frontispiece for the second edition of the pamphlet A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre

- Mullikan engraving : The clockmaker Joseph Mulliken based this image on Paul Revere's engraving, and printed it in Newburyport, MA.

- Revere's 1772 woodcut engraving : Paul Revere based this image on his 1770 engraving; it was used in a broadside commemorating the Boston Massacre and was also printed in a 1772 Massachusetts almanac .

- 1835 Hartwell woodcut : Based on Paul Revere's 1770 engraving, this image was printed in various magazines in the 1830s and '40s.

- 1856 Bufford lithograph : Unlike the earlier images that features all victims and bystanders as white, this lithograph centers Crispus Attucks, a Black and Indigenous man

Henry Pelham’s Fruits of Arbitrary Power, or the Bloody Massacre (American Antiquarian Society)

Paul Revere based his engraving of the Boston Massacre on one done first by Henry Pelham (a Bostonian and future Loyalist). View Pelham’s original engraving at the AAS website.

Explore additional primary sources related to the Boston Massacre, and the earlier death of Christopher Seider, in this digital textbook produced by the MHS.

Perspectives on the Boston Massacre - Massachusetts Historical Society (masshist.org)

Examine materials from a variety of source types to learn more about the varying perspectives and experiences regarding March 5, 1770.

Massachusetts Historical Society | Commemorating the 250th Anniversary of the Boston Massacre (masshist.org)

In 2020, the MHS organized an exhibition featuring handwritten and published sources with compelling accounts of the confrontation, the aftermath, and the trials. This website is the digital companion to the physical exhibit.

Revolutionary Spaces is a museum based at the Old State House, the site of the Boston Massacre that explores connections between the past and present.

On-site programming includes a tour on the Massacre and Memory and an exhibit entitled “Framing Mass Killings.”

Digital resources include a video called “Political Violence: From the Boston Massacre to Today” and a blog post on “The Boston Massacre and Modern Police Violence.”

Old North Church

Illuminating the Unseen | The Old North Church From the website of Old North Church: “Illuminating the Unseen is a video series produced by Old North Illuminated that studies the histories of Black and Indigenous peoples. Written and presented by our Research Fellow, Dr. Jaimie Crumley, the series dives into Old North’s archival documents to shine a light on those who have often been excluded in the church’s broader historical narrative.”

The Occupation of 1768 and the Threat to Boston | The Old North Church & Historic Site British soldiers arrived in Boston, MA in 1768 and departed in the spring of 1770. This article situates the Boston Massacre within the timeline of the British occupation, and examines the ways in which it did and did not influence the British Parliament to withdraw troops from the city.

Boston 1775 , a blog run by Massachusetts writer J.L. Bell, specializes in the start of the American Revolution in Massachusetts.

Find posts on Newton Prince , Jane (Crothers) Whitehouse , Joseph Whitehouse , and more.

Boston 1775: Pvt. Joseph Whitehouse’s Story about Capt. Goldfinch Learn more about Joseph Whitehouse, 14th Regiment soldier and husband to Bostonian Jane Whitehouse. What did Whitehouse tell his superiors about British soldiers’ experience with Boston’s townspeople, and why might some of his accounts seem unreliable?

Boston 1775: Newton Prince: London pensioner Following the outbreak of war in MA, how did Newton Prince’s testimony related to the Boston Massacre help him secure a pension as a Loyalist living in London?

"Fire! Voices of the Boston Massacre" is an eight-minute video featuring reenactors reciting portions of actual depositions of people who witnessed the events on King Street the night of 5 March 1770. Although they all witnessed the happenings, they stood in different locations and their accounts are not consistent with one another.

The historical figures portrayed are:

- Captain-Lieutenant John Goldfinch of the 14th Regiment (the soldiers who fired their weapons came from the 29th Regiment)

- Edward Garrick (or Gerrish), a young wigmaker’s apprentice

- Edward Payne, a merchant who lived near the Custom House, Payne was shot by a soldier but survived (the MHS has the bullets that pierced his arm)

- Newton Prince, a free Black man (a lemon merchant and pastry cook—about 35 years old)

- Jane Crothers (she married a British soldier named Joseph Whitehouse soon after the shootings)

- Charles Bourgate, a French Canadian indentured servant of Edward Manwaring

- Elizabeth Avery, a maid who lived and worked in the Custom House

Read the script (the excerpted depositions) for each historical figure.

Questions or suggestions? Contact us at [email protected] .

The Boston Massacre, 1770

March 5, 1770

The Boston Massacre was an incident in which British regulars fired into a group of Bostonians who were harassing them. It is generally considered one of the first acts of violence of the American Revolution.

This illustration depicts the Boston Massacre. Image Source: Digital Culture of Metropolitan New York .

Boston Massacre Summary

The Boston Massacre was a deadly altercation between British soldiers and a Boston mob that occurred on March 5, 1770, where the Redcoats fired on colonists, killing five and wounding six others. It was the culmination of resentment by the Boston citizenry toward British troops that Parliament had deployed in 1768 to enforce the Townshend Acts of 1767 . The incident on March 5 began when a small group of Bostonians started harassing a lone British sentry guarding the Customs House. When a crowd assembled and became more hostile, British reinforcements arrived on the scene to protect the sentry. The soldiers, under the command of Captain Thomas Preston, fired their muskets into the crowd. The first person killed was Crispus Attucks , an African-American who worked on the docks in Boston. In order to restore peace between the Redcoats and the colonists, Governor Thomas Hutchinson conducted an investigation and the soldiers were tried in court. They were defended by Founding Father John Adams and two of the soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. In the years following the Boston Massacre, March 5 was observed as a holiday in Boston, and a memorial was held to commemorate the incident.

Boston Massacre History

The history of the Boston Massacre began long before the night of March 5, 1770. It is important to understand the Boston Massacre was not an incident that just happened one night, out of nowhere. There was a slow, steady buildup of tension between colonists living in Boston and British officials, especially Governor Francis Bernard , over British policies.

The Stamp Act Crisis and the Sons of Liberty

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which imposed taxes on the colonies by requiring various types of documents to be printed on paper that included a stamp on it. The paper was printed in Britain, shipped to the colonies, and had to be purchased from authorized Stamp Distributors. The colonies were outraged when news of the Stamp Act arrived, and the so-called Stamp Act Crisis began. There were protests throughout the colonies. American merchants set up trade boycotts and refused to order products from Britain and the colonial papers were full of articles that criticized the provisions of the act. The slogan, “No taxation without representation” became popular.

In Boston, a group formed that quickly gained a reputation for its harassment of British officials, which included physical violence and vandalism. Prominent members and associates of the group in Boston were Samuel Adams, Joseph Warren, James Otis Jr., and John Hancock.

The group came to be called the Sons of Liberty , and similar groups were formed in other cities, including New York, Charleston, and Philadelphia. Throughout the summer and fall of 1765, the group was responsible for publicly threatening British officials if they enforced the provisions of the Stamp Act. The Sons also coordinated riots that included mobs attacking the homes of men like Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson .

On the morning of December 17, 1765, a broadsheet was posted throughout Boston that demanded Stamp Distributor Andrew Oliver appear at the Liberty Tree at noon and announce his resignation. Oliver did as was requested, although he read his resignation from the window of a house near the Liberty Tree because it was raining.

Parliament Repeals the Stamp Act and Passes the Declaratory Act

On March 18, 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, primarily due to protests from British merchants who believed it would damage their prospects of doing business in the colonies. However, on that same day, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act , which declared Parliament had the “full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.”

The Declaratory Act made it clear the threat of Parliament levying taxes on the colonies was still viable. The Sons of Liberty in Boston did not disband when the Stamp Act was repealed, they continued to meet to discuss and plan resistance to British policies. They believed Parliament was going to continue to exercise its authority — which it gave itself — to levy taxes on the colonies.

The Townshend Acts

In 1767 and 1768, Parliament did exactly as the Sons of Liberty and prominent leaders like Samuel Adams expected, when it passed a series of acts for various purposes, including establishing a flow of revenue from the colonies to Britain, tightening control over the colonial governments, and paying the salaries of royal officials in the colonies.

Collectively, they are known as the Townshend Acts and they set up a system where the officials were obligated to support the taxes because the revenue generated from them paid their salaries. The five acts were:

- The New York Restraining Act

- The Townshend Revenue Act

- The Indemnity Act

- The Commissioners of Customs Act

- The Vice-Admiralty Court Act

The Liberty Affair

To help enforce the Townshend Revenue Act and the Navigation Acts, the American Board of Customs Commissioners located in Boston. The Board of Customs played a key role in an incident with John Hancock and one of his ships. On May 9, 1768, a small ship owned by Hancock, the Liberty, arrived at the Port of Boston. It had come from Madeira, so the Customs Officials expected the ship to be full of wine.

Initially, the Customs Officials said they could not inspect the ship’s cargo, because it was too dark. They said they had to wait until the morning of May 10. When the cargo of Liberty was inspected on the morning of May 10, Customs Officials found it was carrying less than 25% of what they expected. They informed the Customs Commissioners and said could not explain where the other 75% of the cargo went. They said they watched the ship all through the night of the 9th and did not see any cargo taken off the ship. One of those officials was Thomas Kirk, who would change his story two weeks later.

On May 17, the HMS Romney , a British man-of-war, arrived in Boston Harbor. The ship was under the command of Captain John Corner. Corner sent press gangs onshore to force sailors into service on the Romney . Merchants and smugglers avoided Boston Harbor, for fear of losing crew members. However, the presence of the Romney and Corner’s press gangs increased tension between the townspeople and British officials, but likely made Thomas Kirk feel like he could tell the truth about what happened on the night he was supposed to inspect the Liberty .

On June 9, the situation grew worse when Kirk changed his testimony about what happened on the night of May 9. He told Joseph Harrison, the Collector of the Port of Boston, that the Captain of the Liberty had offered him a bribe and the Liberty was, in fact, smuggling extra casks of wine. Harrison took the new information to the Board of Customs Commissioners.

Harrison, along with other British officials, including Comptroller Benjamin Hallowell were warned by members of the Sons of Liberty to leave Hancock’s ship alone. The warning was ignored, and on June 10, David Lisle, the Solicitor General to the Board of Customs, ordered the Liberty to be seized. Sailors from the Romney were sent to carry out the task.

A crowd gathered and some of them tried to convince the British officials to leave the Liberty alone, at least until John Hancock could arrive on the scene. Harrison and Hallowell declined and a fight broke out while the sailors towed the Liberty away and moored it near the Romney.

Harrison and Hallowell fled the scene. However, the crowd at the dock, which had grown to around 3,000 people, chased after them. When the crowd was unable to find them, they went to the homes of the two men and smashed in the windows. After that, they went back to the dock and pulled Harrison’s boat out of the water. They dragged it through the streets to Boston Common where they set it on fire and burned it to the ground.

The seizure of the Liberty caused unrest in Boston because many people believed it had been illegally taken. Rumors started to circulate that people from all around Boston were planning to “begin an insurrection.”

Boston’s political leaders sent a letter to the colony’s agent — or representative — in London, Dennys De Berndt. The letter placed the blame for the incident on the Townshend Acts and Parliament’s continued efforts to raise taxes from the colonies. It also compared the Customs Officers and Commissioners to thieves who stole from the people of Massachusetts.

The Customs Commissioners also expressed concerns that an uprising was imminent in a letter they sent to London. They accused the local assemblies of coordinating efforts to resist British policies and believed if there was an uprising in Boston it would spread to other colonies. They suggested the only way to stop an uprising was to send troops to Boston to occupy the town.

Governor Francis Bernard also sent a detailed narrative of the incident to William Legge, Lord Hillsborough, the Secretary of State for the Colonies. Bernard urged Hillsborough to do something to help prevent an uprising because he believed the colonists were capable of insurrection.

Ultimately, Hancock was taken to court by the Customs Commissioners, where he was defended by John Adams. Although the charges against Hancock were eventually dismissed, he did lose the Liberty , which was purchased by the Customs Commissioners and used to patrol the waters off Rhode Island for smugglers.

Military Occupation of Boston

In order to restore order in Boston, prevent an uprising, and enforce the provisions of the Townshend Acts, British troops were sent to Boston to occupy the town. Governor Bernard had asked for troops as early as 1766 due to the unrest and his request was finally granted. The American Customs Board of Commissioners also asked for troops to help them enforce the Townshend Acts in the aftermath of the Liberty Affair. Ships carrying troops arrived on September 28, 1768. On October 1, the troops disembarked and were quartered at various locations throughout the town.

For several months, the monthly Boston Town Meeting discussed the problem of troops occupying the city during peacetime. During the meetings, the officials in Boston and Massachusetts questioned the legality of housing a standing army during a time of peace. They argued it was a violation of the Massachusetts Constitution, the and English Bill of Rights. They believed it would certainly be seen as illegal if it was done in London.

Joseph Warren Comes Into the Spotlight

In March 1769, the Boston Town Meeting adopted a petition to the King, asking for the removal of the troops. At the same meeting, Joseph Warren was appointed to a committee to clear the town from the false accusations that had been made, in regards to rebellion and loyalty to the Crown. The members of the committee were James Otis, Samuel Adams, Thomas Cushing , Richard Dana, Joseph Warren, John Adams, and Samuel Quincy.

John Adams was not as involved as some of the others during this time. He was more cautious about becoming too involved with the unrest. He wrote: “I was solicited to go to the Town Meetings and harangue there. This I constantly refused. My friend Dr. Warren the most frequently urged me to this: My Answer to him always was ‘That way madness lies.’. . . he always smiled and said, ‘it was true.’”

Bernard Replaced and Some Troops Leave Boston

On July 21, 1769, Governor Bernard left Boston and returned to England. He was replaced by Thomas Hutchinson, a native of Massachusetts.

Soon after Bernard left Boston, two regiments — the 64th and 65th — were removed from the city. The 14th Regiment and 29th Regiment remained. Despite the reduction in the number of troops that were quartered in the city, the activities the troops indulged in made matters worse with the citizens of Boston. Some of the issues were:

- British officers paraded their troops through the streets on a frequent basis.

- On Sundays, the troops would race their horses through the streets.

On top of those things, off-duty soldiers were often employed by businesses in the city when they were off duty. The residents of Boston who needed jobs accused the soldiers of taking their jobs.

The people of Boston retaliated by insulting and teasing the troops, which would sometimes lead to arguments or even fights.

The Death of Christopher Seider

On February 22, 1770, a mob gathered outside the home of a Customs Official Ebeneezer Richardson. The people were upset that Richardson had broken up a protest in front of the shop owned by Theophilus Lillie, a Loyalist merchant.

The crowd turned violent and threw rocks through the windows of Richardson’s house. One of them hit Richardson’s wife. When that happened, Richardson grabbed his gun and fired into the crowd. 11-year-old Christopher Seider was shot twice, once in the arm and once in the head.

After the boy died, his body was taken to Joseph Warren for an autopsy. Warren found the body contained, “eleven shot or plugs, about the bigness of large peas.”

Warren’s autopsy confirmed the boy was indeed killed by Richardson’s weapon. Some consider the boy to be the first casualty of the American Revolution.

Samuel Adams arranged for Seider’s funeral and a public display was made of what Richardson had done. An estimated 2,000 people attended the funeral at the Granary Burial Ground which fueled the outrage of the people of Boston.

Incident on March 2, 1770

On March 2, a British soldier, Private Patrick Walker, was walking along Gray’s Ropewalk in Boston, looking for a job. A Boston rope maker, William Green, asked Walker if he was looking for work. When Walker said he was, Green told him he could clean the public toilet. Walker was offended and told Green, “Empty it yourself.”

When the two exchanged heated words, Walker tried to hit Green. One of Walker’s employees knocked Green down. When Walker was able to get to his feet, he went to the barracks and gathered some friends. He returned to the scene with a handful of soldiers and they were looking for a fight.

When the rope makers saw them, they gathered to help defend Walker and then roughly 40 soldiers arrived on the scene. The crowd of rope makers included Samuel Gray and, possibly, Crispus Attucks. A full-scale riot broke out and the rope makers forced the British soldiers to return to their barracks.

The Boston Massacre — March 5, 1770

On the morning of March 5, the news of Christopher Seider’s death appeared in the Boston Gazette . That night, an altercation between a British soldier, Private Hugh White, and a 13-year-old boy, Edward Garrick exploded into violence.

The incident started when Garrick insulted Captain Lieutenant John Goldfinch. Goldfinch ignored the boy, but Private White, who was nearby at his post, demanded the boy apologize to Goldfinch. Garrick refused, and words were exchanged. Then Garrick poked Goldfinch in the chest, which led to White hitting the boy in the head with his musket. Garrick’s friend, Bartholomew Broaders, started arguing with White, which drew the attention of more people. The crowd grew and included Boston bookseller Henry Knox.

The officer in charge of the night’s watch, Captain Thomas Preston, was alerted to the trouble and sent an officer and six privates to assist White. Preston ordered the troops to fix bayonets and went with them to the scene. By the time they arrived, the crowd had grown to more than 300 people.

The commotion and shouting led to the church bells being sounded, which usually meant there was a fire. More people came running to the scene, including John Adams.

The crowd started throwing snowballs, ice, rocks, and other things at the troops. Private Hugh Montgomery was hit with something and dropped his musket. When he picked it back up, he fired into the crowd, even though Preston had not given an order to fire. Montgomery’s discharge struck and killed Crispus Attucks . Within moments, the other troops panicked and fired into the crowd. When the shooting was over, five were dead, and six were wounded. Along with Attucks, the others killed by British fire were Samuel Gray, Patrick Carr, James Caldwell, and Samuel Maverick.

The crowd backed away and Preston called soldiers from the 29th Regiment out. The British took defensive positions in front of the Town House to protect themselves from the mob. Governor Hutchinson was called out to help restore order. Hutchinson promised the mob there would be an investigation into the incident, but only if the mob dispersed. The mob did break up.

During the melee, Warren was called to the scene to tend to the wounded. Later, he recalled the incident and wrote: “The horrors of that dreadful night are but too deeply impressed on our hearts. Language is too feeble to paint the emotions of our souls, when our streets were stained with the blood of our brethren, when our ears were wounded by the groans of the dying, and our eyes were tormented by the sight of the mangled bodies of the dead.”

Warren continued, and made it clear he believed that British troops firing on British citizens was a final straw, “To arms! we snatched our weapons, almost resolved, by one decisive stroke, to avenge the death of our slaughtered brethren, and to secure from future danger all that we held most dear.”

Samuel Adams dubbed the incident “The Boston Massacre.”

Boston Massacre Outcome

Before the mob broke up, the Patriot leaders sent express riders to neighboring towns to inform them of what happened. On the morning of March 6, people from the towns and countryside went into Boston and gathered at Faneuil Hall. According to Hutchinson, they were “in a perfect frenzy.”

A delegation of prominent city leaders was chosen to go to Governor Hutchinson and ask for the immediate removal of the troops. Warren was one of the members of the delegation, along with Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Hutchinson had the troops moved out to Castle William in the harbor.

Official Report — A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre

A week later, the Boston Committee of Safety organized a committee, which included Warren, to investigate the incident. Warren wrote the report for the committee, which was called “A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston.” The report blamed Parliament for what happened because of the situation it had put the troops in.

The report said, “As they were the procuring cause of the troops being sent hither, they must therefore be the remote and blameable cause of all the disturbances and bloodshed that have taken place in consequence of that measure.”

The report was published as a pamphlet and included an appendix with 96 depositions. It was sent to Britain to ensure the government received the American viewpoint of what was happening in Boston.

Boston Massacre Trials

Captain Preston and his men were eventually tried in court for the accusations made against them in regard to the incident. John Adams defended them in court, along with Josiah Quincy, Jr., Sampson Salter Blowers, and Robert Auchmuty.

Preston’s trial started on October 24, 1770. He was found not guilty on October 30.

The trial of the eight soldiers from the 29th regiment started on November 27. The jury reached its verdict on December 5. Six of the soldiers were acquitted. Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy were found guilty of manslaughter. Montgomery and Kilroy were branded with the letter “M” — for manslaughter — on their hands, where the palm meets the thumb.

Repeal of the Townshend Acts

After the Boston Massacre, the situation calmed down in Boston, especially since the troops had been moved to Castle William.

On March 5, the same day the news of Christopher Seider’s death was printed in the Boston Gazette and the Boston Massacre took place, Lord North made a motion in the House of Commons to partially repeal the Townshend Acts.

On April 12, 1770, Parliament voted to repeal the taxes levied by the Townshend Acts, except for the tax on tea.

After the repeal of the Townshend Acts, many of the Patriots toned down their involvement in political affairs. However, Joseph Warren and Samuel Adams continued to write in the papers and warned people that it was only a matter of time before Parliament would start levying taxes and infringing on their rights again.

Boston Massacre Memorials

In the years following the Boston Massacre, May 5 was a holiday in Boston and a memorial was held to commemorate the incident. Each year, a prominent member of the community was chosen to deliver a speech, which would be printed in the papers.

Massacre Day 1772

In 1772, the committee that selected the speaker unanimously chose Joseph Warren. He delivered his speech at the Old South Church, and it marked the first time he spoke publicly before a large audience. An estimated 5,000 people were in attendance. Warren used the opportunity to give a passionate speech that criticized Parliament and he called on the people to defend their rights against oppressive British policies.

Warren’s speech was a huge success with the Patriot faction and was printed in the papers throughout the colonies.

Massacre Day 1775

In 1775, as March 5 approached, rumors spread through Boston that British officers were threatening violence against whoever delivered the Massacre Day speech. Once again, Joseph Warren delivered the speech from the pulpit at Old South Church. The church was so full that Warren had to use a ladder to climb in through a window a the back of the pulpit. Roughly 40 British officers were seated in the front rows and some of them were even on the steps leading to the pulpit. They intended to harass Warren during the speech. Warren’s friends, who were also in attendance and scattered throughout the church, feared for his life and were prepared to react at a moment’s notice to protect him.

Warren delivered the speech dressed in a white Roman toga, which was meant to be a symbol of liberty. His speech lasted for roughly 35 minutes. Warren delivered a speech that clearly laid out that Parliament had no right to tax the colonies without their consent and criticized it for the “baleful influence of standing armies in time of peace.” He pointed out that Britain had made a significant change in its colonials policies, starting with the Sugar Act, when it decided to pass legislation for the purpose of raising revenue.

One of the more famous quotes from his speech was, “Resistance to tyrants is obedience to God.”

Within six weeks, British troops marched to Concord, by way of Lexington, where they were met by Massachusetts Minutemen under the command of Captain John Parker . When Parker and his men refused to lay down their weapons — even though they were dispersing, as ordered by British officer Major John Pitcairn — a shot was fired. Within moments, British troops and American Minutemen were firing on each other and the War for Independence had begun.

Boston Massacre Significance

The Boston Massacre was an important event in American history because British troops fired on and killed American colonists. Because of that, it is commonly referred to as the “First Bloodshed of the American Revolution.”

Boston Massacre APUSH Notes and Study Guide

The APUSH Study Guide for the Boston Massacre l has been moved to a new page and expanded.

- Written by Randal Rust

The Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre marked the moment when political tensions between British soldiers and American colonists turned deadly. Patriots argued the event was the massacre of civilians perpetrated by the British Army, while loyalists argued that it was an unfortunate accident, the result of self-defense of the British soldiers from a threatening and dangerous mob. Regardless of what actually happened, the event fanned the flames of political discord and ignited a series of events that would eventually lead to American independence. John Adams believed that “on that night, the foundation of American independence was laid.”

Following the end of the French and Indian War , Great Britain began to levy taxes on her colonies to defray the cost of the expensive war. However, colonies who had been in charge of taxing themselves began to openly resist Great Britain. Decades of self-rule and benign neglect had many colonists feeling their liberty was being stripped away by their mother country. Boston was the home to some of the most radical opponents and largest protests. In an attempt to use an excessive amount of force to crack down on these upstart colonials, Great Britain passed the Townshend Acts in 1767 and dispatched the British Army to restore order in Boston. On October 1, 1768, the British fleet arrived, and hundreds of British soldiers marched into the hostile city.

Rather than restore order, this maneuver proved to only worsen relations between the British and Americans. The presence of British regular troops in the streets of Boston enraged colonists, who now felt they were being occupied by a foreign army. British soldiers faced numerous insults and taunting as they patrolled the streets. The verbal abuse soon became physical as fights between civilians and British soldiers became common in the streets of Boston. Angry mobs would frequently protest British soldiers or American loyalists who supported the British policies. In February of 1770, Christopher Seider, an 11-year-old boy, was killed while protesting with a group in front of the home of a loyalist. Thousands of Bostonians turned out for the boy’s funeral and the tension and distrust between the civilians and the British grew larger.

It was just eleven days after Seider’s death, on March 5, 1770, when Private Hugh White of the 29 th Regiment of Foot took up a sentry post outside of the Customs House on King Street. The Customs House had taken on symbolic meaning as the center of British taxation. As a young wigmaker’s apprentice, Edward Garrick, passed the sentry, he yelled at a British officer that he had not paid his bill for a wig. The sentry, White, reprimanded the young man. The two engaged in a heated conversation when Private White swung his musket at Garrick, hitting him on the side of the head.

Word traveled through the streets about the altercation and a large mob began to descend on the lone British sentry at the Custom House. As the mob of people began to grow larger and larger, the sentry called for reinforcements. Seven British soldiers of the 29 th Regiment of Foot, under the command of Captain Thomas Preston, marched to the sentry’s defense with fixed bayonets. As the nine British soldiers stood guard near the steps to the Custom House, passions enflamed and dozens of more people joined the crowd surrounding the soldiers. Bells began ringing in the city and more people came out of their homes and into the streets. The crowd was estimated to have grown to as many as 300 or 400 people. They were yelling at the soldiers, shouting profanities and insults at the soldiers. Others threw rocks, paddles, and snowballs at the besieged men. One of those protestors near the soldiers was a former slave named Crispus Attucks . The crowd continued to hurl verbal abuse and challenged the soldiers repeatedly to fire their weapons. Preston’s men loaded their muskets in front of the crowd.

The crowd became angrier and angrier. At one point a club or stick was thrown at the soldiers and struck one of the British soldiers. The soldier fell to the ground. He stood back up and yelled, “Damn you, fire!” and fired his musket into the crowd. The musket ball struck Attucks who fell dead to the ground. A few seconds later, the other British soldiers fired into the crowd. Eleven people were hit, five men were killed and six were wounded. After the smoke cleared, Preston ordered his men to cease fire and called out dozens of soldiers to defend the Custom House.

Most of the crowd of civilians left the area immediately around the soldiers as others ran to help the wounded. American blood had been spilled at the hands of British soldiers for the first time. Royal governor Thomas Hutchison arrived on the scene and calmed the anxious and angry colonists and promised justice for what had just occurred. The next day Preston and the eight soldiers involved were arrested and sent to trial for murder.