- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Beccaria – “On Crimes And Punishments”

November 4, 2018 By Margit

Cesare Beccaria is seen by many people as the “father of criminology.” Here is a brief summary of his ideas and famous essay “On Crimes and Punishments,” both in video and text format.

Table of Contents

Discussions about Crime and Punishment

Cesare Beccaria is seen by many people as the “father of criminology” for his ideas about crime, punishment, and criminal justice procedures. He was an Italian born as an aristocrat in the year 1738 in Milan. At that time European thought about crime and punishment was still very much dominated by the old idea that crime was sin and that it was caused by the devil and by demons. And in part to punish the devil and the demons that were causing crime, very harsh punishments were used. At the time when Beccaria came along, the era of Enlightenment was in full swing, and scientists were starting to challenge the old views, but the people who had political power were not ready to leave those old ideas behind yet.

Beccaria didn’t start out as an intellectual. In fact, he wasn’t considered to be above average or interested really when it came to science or philosophy. But after he completed his law studies at the University of Pavia, he started to surround himself with a group of young men who were interested in all kinds of philosophical issues and social problems. And the intellectual discussions that Beccaria was able to have with these people led him to question many of the practices that were common in his time, including the way in which offenders were being punished for their crimes.

Publication of Beccaria’s “On Crimes and Punishments”

Beccaria’s famous work, “On Crimes and Punishments,” was published in 1764, when he was 26 years old. His essay called out the barbaric and arbitrary ways in which the criminal justice system operated. Sentences were very harsh, torture was common, there was a lot of corruption, there were secret accusations and secret trials, and there was a lot of arbitrariness in the way in which sentences were imposed. There was no such thing as equality before the law. And powerful people of high status were treated very differently from people who were poor and who did not have a lot of status.

Beccaria’s ideas clashed dramatically with these practices. And I’ll go through some of the central principles that his work is based on.

Only the Law Can Prescribe Punishment

According to Beccaria, only the law can prescribe punishment. It is up to the legislator to define crime and to prescribe which punishment should be imposed. It is not up to a magistrate or a judge to impose a penalty if the legislator has not prescribed it. And neither is it up to a judge to change what the law says about how a crime should be punished. The judge should do exactly what the law says.

The Law Applies Equally to All People

In addition, Beccaria said that the law applies equally to all people. And so punishment should be the same for all people, regardless of their power and status.

Making the Law and Law Enforcement Public

Beccaria also believed in the power of making the law and law enforcement public. More specifically, laws should be published so that people actually know about them, and trials should be public, too. Only then can onlookers judge if the trial is fair.

Beccaria: Punishments Should be Proportional, Certain, and Swift

Regarding severe punishment, Beccaria said that if severe punishments do not prevent crime, they should not be used. Instead, punishments should be proportional to the harm that the crime has caused. According to Beccaria, the aim of punishment is not to cause pain to the offender, but to prevent them from doing it again and to prevent other people from committing crime. In order to be able to do that, Beccaria believed that punishment should be certain and swift. He believed that if offenders were sure that they would be punished and if punishment would come as quickly as possible after the offense, that this would have the largest chance of preventing crime.

Beccaria Argued Against the Death Penalty

As another controversial issue, Beccaria argued against the death penalty. In his view, the state does not have the right to repay violence with more violence. And in addition to that, Beccaria believed that the death penalty was useless. The death penalty is momentary, it is not lasting and therefore the death penalty cannot be very successful in preventing crimes. Instead, lasting punishments, such as life imprisonment, would be more successful in preventing crimes, because potential offenders will find this a much more miserable condition than the death penalty.

No Right To Torture

Similarly, according to Cesare Beccaria, the state does not have the right to torture. Because no one is guilty until he or she is found guilty, no one has the right to punish a person by torturing him or her. Plus, people who are under torture will want the torture to stop and might therefore make false claims, including that they committed a crime they did not commit. So torture is also ineffective.

The Power of Education

Instead of torture and severe penalties, Beccaria believed that education is the most certain method of preventing crime.

Beccaria: Controversy and Success

Beccaria’s ideas are hardly controversial today, but they caused a lot of controversy at the time, because they were an attack on the entire criminal justice system. Beccaria initially published his essay anonymously, because he didn’t necessarily consider it to be a great idea to publish such radical ideas. And this idea was partly confirmed when the book was put on the black list of the Catholic Church for a full 200 years.

But even though his ideas were controversial back then, his essay became an immediate success. In fact, Cesare Beccaria’s ideas became the basis for all modern criminal justice systems and there is some evidence that his essay influenced the American and French revolutions which happened not long after the publication of the essay. His ideas were not original, because others had also proposed them, but Beccaria was the first one to present them in a consistent way. Many people were ready for the changes that he proposed, which is why his essay was such a success.

Beccaria ends his essay with what can be seen as a kind of summary of his view:

“So that any punishment be not an act of violence of one or of many against another, it is essential that it be public, prompt, necessary, minimal in severity as possible under given circumstances, proportional to the crime, and prescribed by the laws.”

You can find Cesare Beccaria’s full essay “On Crimes and Punishments” here .

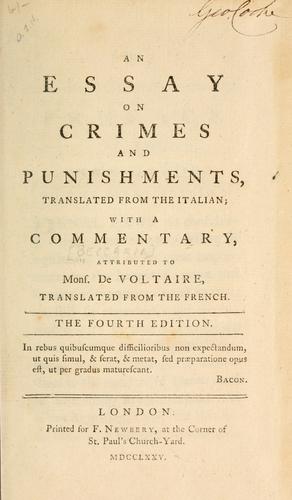

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments

- Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria (author)

- Voltaire (author)

An extremely influential Enlightenment treatise on legal reform in which Beccaria advocates the ending of torture and the death penalty. The book also contains a lengthy commentary by Voltaire which is an indication of high highly French enlightened thinkers regarded the work.

- EBook PDF This text-based PDF or EBook was created from the HTML version of this book and is part of the Portable Library of Liberty.

- Facsimile PDF This is a facsimile or image-based PDF made from scans of the original book.

- Kindle This is an E-book formatted for Amazon Kindle devices.

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. By the Marquis Beccaria of Milan. With a Commentary by M. de Voltaire. A New Edition Corrected. (Albany: W.C. Little & Co., 1872).

The text is in the public domain.

- United States

Related Collections:

Detail from The Good Government (1338-9), by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. To the right: Magnanimity, Temperance and Justice seated above prisoners. From a fresco at the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. Photo by Getty Images

The first socialist

Well before bentham, cesare beccaria radically questioned the right of the state to imprison and execute its citizens.

by Lorenzo Zucca + BIO

On 12 April 1764, the citizens of Milan witnessed the brutal killing of Bartolomeo Luisetti. He had been condemned to death after being accused of sodomy. Luisetti was killed by asphyxiation and then burnt at the stake in front of the crowd. Throughout Europe, ruling elites believed that criminal justice had to be done and be seen to be done; and that criminal punishment had to be cruel so as to instil the fear of God in the people watching the horrific spectacle.

Cesare Beccaria witnessed the scene with horror. It was hard to believe that such cruelty could be regarded as a rational response. At the time of the event, Beccaria was only in his mid-20s, but already had strong political and philosophical views. Born in 1738, the first son of a prominent Milanese aristocrat, he was educated in a stifling Jesuit school in Parma. After studying law in Pavia, he returned to Milan where his eyes were opened by Montesquieu’s Lettres persanes (1721), or Persian Letters, an epistolary novel giving an outsider’s critical angle on Parisian customs. Beccaria entered the world of Enlightenment philosophy without hesitation; his lodestars were French and British intellectuals, and he was inspired in particular by reading Claude Adrien Helvétius, Denis Diderot, David Hume and John Locke.

In 1759, Beccaria became a member of the so-called ‘ academy of fisticuffs ’, a group of young Milanese aristocrats who rebelled against the oppression of the local elite, including their own families: the conflict was social and intergenerational. As they saw it, the interests of the few systematically trumped the interests of the many, and the laws were designed to increase the power of the privileged class. Their collaboration gave birth to a magazine called Il Caffé, a vehicle for reformist ideas. In 1762, Rousseau published The Social Contract, which provided Beccaria with an ideological framework: his treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764) was published two years later, and 25 years before the French Revolution. Beccaria’s manifesto against cruel punishment spread swiftly through Europe, igniting radical reforms of repressive and coercive institutions throughout the continent.

Europe was at that time a profoundly hierarchical society, where a few privileged people ruled over the entire population with an arbitrary and unaccountable authority. Enlightenment philosophers took inequality to be the germ of social injustice. Beccaria had the ambition to radically reform his society, the institutions and the laws. It was an ambition shared by all Enlightenment thinkers in Europe, although the means to achieve that reform differed. France took the revolutionary path, while Milan engaged in steady reforms from within; Beccaria and the other pugilists were to play an important part in the administration of the city state.

European radical thinkers agreed that the Church was one of the strongest enforcers of inequality and subjection. Indeed, Italian political minds never ceased to be inspired by Niccolò Machiavelli’s central idea that Christian morality is incompatible with the morality of Civic Republicanism. The former is passive, and requires obedience to the established authority; the latter is active, and demands participation in the political affairs of the city. Only when the city was put first would institutions and laws reflect the interests of the whole society, and not just the vested interests of a few privileged ones.

Mindful of the interest of the many, Beccaria formulated a motto: la massima felicità divisa nel maggior numero (the greatest happiness shared among the greater number), which was subsequently adopted by the English utilitarian thinker Jeremy Bentham. Beccaria saw this maxim as a fundamental tenet of a new science, whose object was human society and whose name was ‘the science of man’, echoing Hume’s project in that phrase. Beccaria’s keen interest in mathematics and the sciences was channelled into the development of political economy and, soon afterwards, Beccaria was made chair of political economy in Milan, his first civic appointment.

Political economy for Beccaria was not just a tool with which to administer the state more efficiently; it was a Copernican revolution that explained the place of man in society, and the importance of reconceiving politics to serve the interests of any particular society. Political economy was intended to be the science of happiness, and aimed to replace religion as the guiding light of human behaviour. Beccaria was aware that great progress had been achieved in public matters through political economic reforms: trade replaced wars, print spread new ideas, and the relation between sovereign and subjects had been reconceived. But he also noted that little had been said and done about the cruelty and arbitrariness of criminal laws, the most immediate and visible display of brute force that had not yet been subject to rational analysis. He knew that it was not uncommon in those years to see people condemned to death and brutally ravaged in the public square with the intent of educating the citizenry.

On Crimes and Punishments was the first attempt to apply principles of political economy to the practice of punishment so as to humanise and rationalise the use of coercion by the state. After all, arbitrary and cruel punishment was the most immediate instrument that the state had to terrorise the people into submission, so as to avoid rebellion against the hierarchical structure of the society. The problem that Beccaria faced, then, was the simple fact that the elite had complete control of the law, which was a family business and a highly esoteric language that only the initiated could master. The path leading to the rational reform of penal law required a fundamental philosophical rethinking of the role and place of law in society.

B eccaria’s project was to dismantle the edifice of Roman law, which he mockingly referred to as ‘a few odd remnants of the laws of an ancient conquering race codified 1,200 years ago by a prince ruling at Constantinople’. The law was an arcane language of power, he felt; its content was unclear and imprecise as it was made of the odd admixture of Roman law, local customs, and it was ‘bundled up in the rambling volumes of obscure academic interpreters’. The opacity of the law was deliberate and instrumental to the control of the people.

Beccaria was a trained lawyer as well as a published mathematician, but philosophy was the key to his mission of reform. On Crimes and Punishments was the first glaring model of an excoriating work of censorial jurisprudence. As the English philosopher H L A Hart pointed out in 1982:

Bentham admired Beccaria not only because he agreed with his ideas and was stimulated by them but also because of Beccaria’s clear-headed conception of the kind of task on which he was engaged. According to Bentham, Beccaria was the first to embark on the criticism of law and the advocacy of reform without confusing this task with the description of the law that actually existed.

Beccaria’s work was entirely censorial; he was the first legal philosopher to maintain a very firm distinction between evaluation and description of the law.

Philosophy was the critical tool that Beccaria used to revolutionise the way in which European societies thought about the law. He was not interested in what the law said: the rule of law was, at the time of his writing, a chimera, since the law obeyed the rule of lawyers and catered for the interests of the few. Beccaria’s censorial approach focused on the law as a social institution that had always been taken for granted as a benevolent instrument of social order. Beccaria’s contribution to the philosophical methodology was monumental, but we should not forget that this philosophical turn had an underlying ambition of substantial social, political and institutional reform.

Beccaria was accused of being a ‘socialist’, in this term’s earliest known vernacular appearance. The charge came from two opposite directions: Padre Facchinei, a theologian who dreaded the rise of political economy as an immanent replacement for religion, used it first. Then came French economists, the so-called Physiocrats and other freemarketeers, who criticised Beccaria for the demanding role he gave the state in the economy, a stance that pointed the way to redistribution and social justice. Both Facchinei and the Physiocrats, along with Adam Smith, believed that the market was a spontaneous order guided by an invisible hand , possibly that of God. Beccaria disagreed: political institutions had a significant interventionist role to play in bridging the gap between the rich and the poor, which he plausibly regarded as the prime cause of crime.

Whether or not Beccaria was a socialist in a way we would recognise today is debatable. He certainly was, however, a secular political thinker whose main aim was to promote a free and equal society, and his main focus was on political justice as opposed to divine justice. Political justice, he believed, exists only because of the creation of a political society, which is a free association of men through the social contract. Thus, crime is defined as a breach of the social contract and not as a sin.

His originality lies in the way he arrives at a compromise between freedom and utility in the name of justice

Under the social contract, people agree to pool together a minimum portion of their freedom so as to guarantee its protection under the unified power of an authority: they swap their natural freedom in the state of nature for political freedom in the civil order of the state. The social contract is not a moment of celebration. People grudgingly agree to sign a pact with each other, and they are frequently tempted to break that pact to pursue their own advantage. What moves them to stick to the pact is the feeling of uncertainty, which makes it impossible to enjoy their natural freedom to act according to their immediate passions. The uncertainty as to how to exercise natural freedom leads everyone to accept a basic necessity: something has to be given away in order for everyone to enjoy genuine political freedom. Everyone’s minimum portion of natural freedom constitutes the public deposit of sovereignty which is the basis for the right to punish those actions that are injurious to the human society. The right to punish is a necessary evil that is exercised by the sovereign in order to respond to the radical uncertainty created by the unfettered exercise of natural freedom.

Political freedom is a psychological, qualitative state and not something that can be measured or quantified by the law. However, the law can help by giving clear and predictable guidance as to what counts as socially harmful behaviour, which will in turn result in the feeling of security. Criminal law’s aim is to guarantee political freedom. Beccaria’s insistence on the rule of law as the guarantor of individual liberty was later on enshrined in Article 4 of the French Declaration of the Rights of the Man and the Citizen (1789):

Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

Yet Beccaria’s originality does not lie in developing innovative interpretations of utility, political freedom or the social contract. His originality lies in the way he combines them to arrive at a compromise between freedom and utility in the name of justice. As far as criminal justice is concerned, the right to punish must be as narrow as possible if it is to be considered legitimate. The conclusion of On Crimes and Punishments could not be clearer:

In order that punishment should not be an act of violence perpetrated by one or many upon a private citizen, it is essential that it should be public, speedy, necessary, the minimum possible in the given circumstances, and determined by the law.

This theorem set in motion a cultural revolution. Beccaria’s little tract is the symbol of a philosophical movement that was bent on replacing entrenched forms of knowledge that were used by elites to preserve their privileges. The traditional understanding of the law was arcane and inaccessible. Beccaria wanted to replace it with a demystified conception of the law as the product of social fact, whose sole source would be legislation. He also knew that religion was still a potent form of social control; for that reason, he enthusiastically embraced the turn to political economy as a source of knowledge that government could use to ground its policies on reason. It is important to stress, however, that his philosophical method was the driving force of his ideas. He used philosophy to undermine the grounds of ancient law, and to carve out an immanent domain of politics, free from traditionalist and moralist understandings of justice.

T o justify punishment using reason meant to reduce – even to minimise – the quantity and quality of violence within the society. Not only the violence attached to crimes, but also the violence entailed by the reaction to crimes by private parties and by public authorities. Beccaria’s goal was to regulate the right to punish, and eradicate from its practice all forms of vengeance and religious beliefs. This idea of rational punishment has its advocates and its detractors, of course. Advocates understand that cruel and arbitrary punishment does not build a robust sense of trust in the public authority; they also believe that punishment might be a necessary deterrent against the use of private and public violence, so they accept punishment as expressing society’s commitment against violence. On the other hand, detractors believe that rationalising punishment amounts to giving the state a more efficient instrument with which to control and discipline us. Both views are important, but for Beccaria the project of rationalising punishment had a deep reformist meaning. It meant moving from a society that wielded punishment as a weapon of mass control to a society in which punishment would only be the last resort, and proportional to the crime.

Minimum Criminal Law is an apt formula to describe Beccaria’s critique of the practice of punishment. It refers to the specific nature of Beccaria’s social contract, which stipulates only a minimum transfer of natural freedom. In return, the contract will justify only a minimum restriction on natural freedom and suffering. The principle of minimum evil is deduced from the sacrificial nature of the contract: the minimum transfer of natural freedom for the maximum gain of political freedom.

Because the intervention of criminal law is limited by necessity, the state can use criminal law only as a final resort. If there are other means to prevent crimes, they should be used. This part of Beccaria’s thought is often ignored by those who consider him the forefather of utilitarianism in England or the ancestor of law and economics in the United States. This is so because Beccaria asks for the least penal intervention, and for the maximum provision of social services as part of the same package. It is criminal law that must be kept to a minimum, not the state. Beccaria requires a robust intervention of the state to redress inequality and to prevent crimes by educating and assisting people, not by repressing them.

Should we invest in tracking petty thieves, or should the system focus its attention on grand-scale criminality?

Beccaria’s views conquered Europe’s enlightened circles. He was received in Paris as a hero by the philosophes : Diderot annotated his little tract, and Voltaire wrote a review claiming that the reform of criminal law along Beccaria’s ideas ought to become one of the centrepieces of the Enlightenment’s reforms. Thomas Jefferson, who resided at the time in Paris, read the book in Italian, and sent copious notes back to the American founding fathers. Catherine II of Russia even invited Beccaria to lead the drafting of the Russian penal code and the reform of criminal justice. Beccaria’s tract became so popular that in 1866 Fyodor Dostoyevsky borrowed its title for one of his major works. In less than a century, Europe had started to implement his ideas: torture began to disappear, and the death penalty was abolished in a growing number of states. To celebrate the 100th anniversary of On Crimes and Punishments , the Italian Parliament voted in 1865 to abolish the death penalty in the kingdom and to erect a statue of Beccaria in his native Milan.

Quietly ignored for a century or more, Beccaria’s little book is being rediscovered today. Why? I suspect that his radical, reformist spirit hits a deep chord with many people. Inequality is again on the rise. In most countries, criminalisation is also on the rise: criminal law attempts to micromanage the behaviour of the many, while giving a blank cheque to wealthy billionaires whose tax-dodging and exploitative behaviour go unpunished.

We have once more reached a point where we need to reconsider the whole system of criminal justice. It is not about tinkering with what we have; it is about reforming criminal law radically. What hurts our society more? Should we invest endless amounts of resources tracking petty thieves and minor infringements, or should the system focus its attention on grand-scale criminality?

Beccaria denounced the inequality between the ruling class and the masses: he insisted that disproportionate inequality is bound to increase the crime rate because of poverty and injustice. In turn, that predicament is likely to bring only more social conflict and less certainty about security in society. Penal practices are likely to worsen as a result of this; and criminal law might well become once more a force serving the strong against the most vulnerable. In our societies, which are deeply polarised and unequal, Beccaria’s thought still rings true: we need more social justice and less criminal punishment. To have seen this already in the 18th century was remarkable.

Metaphysics

The enchanted vision

Love is much more than a mere emotion or moral ideal. It imbues the world itself and we should learn to move with its power

Mark Vernon

What is ‘lived experience’?

The term is ubiquitous and double-edged. It is both a key source of authentic knowledge and a danger to true solidarity

Patrick J Casey

Human rights and justice

My elusive pain

The lives of North Africans in France are shaped by a harrowing struggle to belong, marked by postcolonial trauma

Farah Abdessamad

Thinkers and theories

Philosophy is an art

For Margaret Macdonald, philosophical theories are akin to stories, meant to enlarge certain aspects of human life

Conscientious unbelievers

How, a century ago, radical freethinkers quietly and persistently subverted Scotland’s Christian establishment

Felicity Loughlin

History of technology

Why America fell for guns

The US today has extraordinary levels of gun ownership. But to see this as a venerable tradition is to misread history

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, on crimes and punishments (1764).

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria | 1764

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, marquis of Gualdasco and Villaregio (1738-94), was the author of On Crimes and Punishments (1764). Inspired by the discussion of criminal law in Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws , this Milanese wrote a systematic treatise on the subject that was almost immediately translated into English and French. In it, he argued that the sole purpose of punishment is deterrence, and he denounced torture, the entertainment of secret accusations, and the death penalty; suggested that pre-trial detention can rarely be justified; and called for promptitude in punishment. The impact of his little book on the post-revolutionary revisal of the laws in the various nascent American states was considerable.

Selected by

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

Chapter 1: Of the Origin of Punishment

Laws are the conditions under which men, naturally independent, united themselves in society. Weary of living in a continual state of war, and of enjoying a liberty which became of little value, from the uncertainty of its duration, they sacrificed one part of it to enjoy the rest in peace and security. . . .

Chapter 2: Of the Right to Punish

Every punishment which does not arise from absolute necessity, says the great Montesquieu, is tyrannical. A proposition which may be made more general, thus. Every act of authority of one man over another, for which there is not an absolute necessity, is tyrannical. It is upon this, then, that the sovereign’s right to punish crimes is founded; that is, upon the necessity of defending the public liberty, intrusted to his care, from the usurpation of individuals. . . .

No man ever gave up his liberty merely for the good of the public. Such a chimera exists only in romances. Every individual wishes, if possible, to be exempt from the compacts that bind the rest of mankind. . . .

Observe, that by justice I understand nothing more than that bond, which is necessary to keep the interest of individuals united; without which, men would return to the original state of barbarity. All punishments, which exceed the necessity of preserving this bond, are in their nature unjust.

Chapter 6: Of the Proportion between Crimes and Punishments

It is not only the common interest of mankind that crimes should not be committed, but that crimes of every kind should be less frequent, in proportion to the evil they produce to society. Therefore, the means made use of by the legislature to prevent crimes, should be more powerful, in proportion as they are destructive of the public safety and happiness, and as the inducements to commit them are stronger. Therefore there ought to be a fixed proportion between crimes and punishments.

Chapter 12: Of the Intent of Punishments

From the foregoing considerations it is evident, that the intent of punishments is not to torment a sensible being, nor to undo a crime already committed. Is it possible that torments, and useless cruelty, the instruments of furious fanaticism, or of impotency of tyrants, can be authorized by a political body? which, so far from being influenced by passion, should be the cool moderator of the passions of individuals. Can the groans of a tortured wretch recal the time past, or reverse the crime he has committed? The end of punishment, therefore, is no other, than to prevent others from committing the like offence. Such punishments, therefore, and such a mode of inflicting them, ought to be chosen, as will make strongest and most lasting impressions on the minds of others, with the least torment to the body of the criminal.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Excerpts from

An essay on crimes and punishments, by cesare beccaria translated from the italian, 1775 (original published in 1764), introduction, chapter i: of the origin of punishments, chapter ii: of the right to punish, chapter vi: of the proportion between crimes and punishments, chapter xii: of the intent of punishments, chapter xix: of the advantage of immediate punishment, chapter xxvii: of the mildness of punishments.

Of Crimes and Punishments

Cesare Bonesana, Marchese Beccaria, 1738-1794

Originally published in Italian in 1764

Introductory Material

Table of Contents

Cesare Beccaria

Cesare Beccaria was one of the greatest minds of the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century. His writings on criminology and economics were well ahead of their time.

(1738-1794)

Who Was Cesare Beccaria?

Cesare Beccaria was a criminologist and economist. In the early 1760s, Beccaria helped form a society called "the academy of fists," dedicated to economic, political and administrative reform. In 1764, he published his famous and influential criminology essay, "On Crimes and Punishments." In 1768, he started a career in economics, which lasted until his death.

Beccaria was born March 15, 1738 in Milan, Italy. His father was an aristocrat born of the Austrian Habsburg Empire, but earned only a modest income.

Beccaria received his primary education at a Jesuit school in Parma, Italy. He would later describe his early education as "fanatical" and oppressive of "the development of human feelings." Despite his frustration at school, Beccaria was an excellent math student. Following his education at the Jesuit school, Beccaria attended the University of Pavia, where he received a law degree in 1758.

Even in his early life, Beccaria was prone to mood swings. He tended to vacillate between fits of anger and bursts of enthusiasm, often followed by periods of depression and lethargy. He was shy in social settings, but cherished his relationships with friends and family.

In 1760, Beccaria extended his family by proposing to Teresa Blasco. Teresa was just 16 years old, and her father strongly objected to the engagement. A year later, the couple eloped. In 1762, they welcomed a baby girl, the first of the couple’s three children.

Also among those people that Beccaria held particularly dear were his friends Pietro and Alessandro Verri. In collaboration with the Verri brothers, Beccaria formed an intellectual/literary society called "the academy of fists." In line with the principles of the Enlightenment, the society was dedicated to "waging relentless war against economic disorder, bureaucratic tyranny, religious narrow-mindedness, and intellectual pedantry." Its main goal was to promote economic, political and administrative reform.

To this effect, academy members encouraged Beccaria to read French and British writings on the Enlightenment, and to take a stab at writing himself. To fulfill his friends’ assignment, Beccaria composed his first published essay, "On Remedies for the Monetary Disorders of Milan in the Year 1762."

Criminal Justice

Also spurred by his involvement in the "academy of fists" was Beccaria’s most famous and influential essay, "On Crimes and Punishments," published in 1764. "On Crimes and Punishments" is a thorough treatise exploring the topic of criminal justice. Because Beccaria’s ideas were critical of the legal system in place at the time, and were therefore likely to stir controversy, he chose to publish the essay anonymously -- for fear of government backlash.

Three tenets served as the basis of Beccaria’s theories on criminal justice: free will, rational manner, and manipulability. According to Beccaria — and most classical theorists — free will enables people to make choices. Beccaria believed that people have a rational manner and apply it toward making choices that will help them achieve their own personal gratification.

In Beccaria’s interpretation, law exists to preserve the social contract and benefit society as a whole. But, because people act out of self-interest and their interest sometimes conflicts with societal laws, they commit crimes. The principle of manipulability refers to the predictable ways in which people act out of rational self-interest and might therefore be dissuaded from committing crimes if the punishment outweighs the benefits of the crime, rendering the crime an illogical choice.

In "On Crimes and Punishments," Beccaria identified a pressing need to reform the criminal justice system, citing the then-present system as barbaric and antiquated. He went on to discuss how specific laws should be determined, who should make them, what they should be like and whom they should benefit. He emphasized the need for adequate but just punishment, and went so far as to explain how the system should define the appropriate punishment for each type of crime.

Unlike documents before it, "On Crimes and Punishments" sought to protect the rights of criminals as well as the rights of their victims. "On Crimes and Punishments" also assigned specific roles to the various members of the courts. The thorough treatise included a discussion of crime-prevention strategies.

In addition to his fascination with criminal law, Beccaria was still drawn to the field of economics. In 1768, he was appointed the Chair in Public Economy and Commerce at the Palatine School in Milan. For the next two years, he also served as a lecturer there. Based on these lectures, Beccaria created an economic analysis entitled "Elements of Public Economy." In it he pioneered the discussion of such topics as division of labor. "Elements of Public Economy" was eventually published in 1804, a decade after Beccaria’s death.

Beccaria’s economics career also entailed serving on the Supreme Economic Council of Milan. This public position enabled him to strive for the same goal — economic reform — that he had set with "the academy of fists" so many years ago. While in office, Beccaria focused largely on the issues of public education and labor relations. He also created a report on the system of measures that led France to start using the metric system.

Beccaria’s career in economics was productive. His work in analysis helped paved the way for later theorists like Thomas Malthus. However, Beccaria failed to match the astronomical level of success he had previously achieved in the criminal justice field. While retaining his career in economics, in 1790 Beccaria served on a committee that promoted civil and criminal law reform in Lombardy, Italy.

Death and Legacy

Near the end of his life, Beccaria was depressed by the excesses of the French Revolution and withdrew from his family and friends. He died on November 28, 1794, in his birthplace of Milan, Italy.

Following his death, talk of Beccaria spread to France and England. People speculated as to whether Beccaria’s lack of recent writing on criminal justice was evidence that he had been silenced by the British government. In fact, Beccaria, prone to periodic bouts of depression and misanthropy, had grown silent on his own.

A forerunner in criminology, Beccaria’s influence during his lifetime extended to shaping the rights listed in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. "On Crimes and Punishments" served as a guide to the founding fathers.

Beccaria’s theories, as expressed in his treatise "On Crimes and Punishments," have continued to play a role in recent times. Recent policies impacted by his theories include, but are not limited to, truth in sentencing, swift punishment and the abolishment of the death penalty in some U.S. states. While many of Beccaria’s theories are popular, some are still a source of heated controversy, even more than two centuries after the famed criminologist’s death.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Cesare Beccaria

- Birth Year: 1738

- Birth date: March 15, 1738

- Birth City: Milan

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Cesare Beccaria was one of the greatest minds of the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century. His writings on criminology and economics were well ahead of their time.

- Crime and Terrorism

- Education and Academia

- Politics and Government

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1794

- Death date: November 28, 1794

- Death City: Milan

- Death Country: Italy

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

American Revolutionaries

Samuel Adams

Andrew Jackson

George Rogers Clark

Roger Sherman

James Monroe

Martha Washington

The Real Story of Paul Revere’s Ride

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

An essay on crimes and punishments

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2,534 Views

12 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Smithsonian Libraries and Archives on May 21, 2015

An essay on crimes and punishments

By cesare beccaria.

- ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ 5.00 ·

- 31 Want to read

- 1 Currently reading

- 1 Have read

My Reading Lists:

Use this Work

Create a new list

My book notes.

My private notes about this edition:

Download Options

Check nearby libraries

Buy this book

Book digitized by Google from the library of Oxford University and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Previews available in: Chinese English French Italian German

Showing 10 featured editions. View all 144 editions?

Add another edition?

Book Details

Published in, the physical object, community reviews (1).

- Created April 1, 2008

- 6 revisions

On Crimes and Punishments by Cesare Beccaria: A Book Review

Beccaria was a young, 25 years old, eager to bring reforms in the Italian criminal justice system. His proposed treaties were the first systematically suggested reforms in the criminal justice system. As noted: "In order that punishment should not be an act of violence perpetrated by one or many upon a private citizen, it is essential that it should be public, speedy, necessary, the minimum possible in the given circumstances, proportionate to the crime, and determined by the law".

Related Papers

Seth Carter

Laura Carter

Tijana Jurišić

John Dunkley

The focus of this collection of essays is the two-way relation of Cesare Beccaria's "On Crimes and Punishments" with Britain. It is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to be entirely devoted to this subject.

Alberto Cadoppi

Tiago Pires Marques

Criminology

Piers Beirne

Diciottesimo secolo

Rosamaria Loretelli

Following the trails of Pietro Molini, an Italian publisher residing in London whose name appears in Alessandro Verri's letters to his brother Pietro, and of John Almon, the publisher of the first English translation of Cesare Beccaria's "On Crimes and Punishments" (1767), this article sheds light on the editorial, political and cultural environments in which the translation came into being. It also illustrates how, when Beccaria and Verri were in Paris in October and November 1766, they repeatedly met John Wilkes, who was living there in exile.

Philosophical Inquiries

Filippo Santoni de Sio

Philippe Audegean

RELATED PAPERS

Fiatal Műszakiak Tudományos Ülésszaka

Sándor Fórián

Critique D Art Actualite Internationale De La Litterature Critique Sur L Art Contemporain

Roula Matar-Perret

Communications

S Bekti Istiyanto

Cadernos CEMARX

Amarilio Ferreira Junior

Louis Mamudi

Solid Earth

Mehran Arian

Pedro Pírez

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology

Sulolipu: Media Komunikasi Sivitas Akademika dan Masyarakat

Andi Ruhban

Global Ecology and Conservation

Dr Rakesh Banyal

Research, Society and Development

Márcio Cleber de Medeiros Corrêa

International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics

Bhadrasain Vikram

Erni Suhartini

Revista Debates Insubmissos

sara meneses

The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics

Antonio Penta

Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease

Juan U. Ayala

Journal of Applied Oral Science

Clóvis Bramante

Maria Gonzalez

Richard Crouch

The University of Texas at Austin: Estados Unidos

Esteban Montenegro

Achara Chandrachai

Call Girls in Zakir Nagar

Call Girls in Mahipalpur Delhi 9899985641 Escorts Service

International Journal of Social Work

Kamal Khatiwada

Antonis Zervos

Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine

Emmanuel Timothy

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

COMMENTS

Beccaria's famous work, "On Crimes and Punishments," was published in 1764, when he was 26 years old. His essay called out the barbaric and arbitrary ways in which the criminal justice system operated. Sentences were very harsh, torture was common, there was a lot of corruption, there were secret accusations and secret trials, and there ...

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments [1764] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of

On Crimes and Punishments. Frontpage of the original Italian edition Dei delitti e delle pene. On Crimes and Punishments ( Italian: Dei delitti e delle pene [dei deˈlitti e ddelle ˈpeːne]) is a treatise written by Cesare Beccaria in 1764. The treatise condemned torture and the death penalty and was a founding work in the field of penology .

Cesare Beccaria (born March 15, 1738, Milan [Italy]—died November 28, 1794, Milan) was an Italian criminologist and economist whose Dei delitti e delle pene (1764; Eng. trans. J.A. Farrer, Crimes and Punishment, 1880) was a celebrated volume on the reform of criminal justice.

An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria (author) Voltaire (author) An extremely influential Enlightenment treatise on legal reform in which Beccaria advocates the ending of torture and the death penalty. The book also contains a lengthy commentary by Voltaire which is an indication of high highly French enlightened ...

An essay on crimes and punishments translated from the Italian of Cæsar Bonesana, marquis Beccaria by Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di, 1738-1794; Voltaire, 1694-1778; Ingraham, Edward D. (Edward Duncan), 1793-1854. Publication date 1819 Topics Crime, Capital punishment, Torture, Punishment, Law reform

ABSTRACT. At the heart of the criminal reform proposed in Cesare Beccaria's 1764 Dei delitti e delle pene (On Crimes and Punishments) are the principles of penal parsimony derived from a precise interpretation of the social contract.Punishment, being no more than a necessary evil devoid of any intrinsic virtue, must serve no more than a preventative function to the smallest possible extent ...

In 1762, Rousseau published The Social Contract, which provided Beccaria with an ideological framework: his treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764) was published two years later, and 25 years before the French Revolution. Beccaria's manifesto against cruel punishment spread swiftly through Europe, igniting radical reforms of repressive and ...

The first systematic study of the principles of crime and punishment. Originally published: London: Printed for E. Newberry, 1775. viii, [iv], 179, lxxix pp. Infused with the spirit of the Enlightenment, its advocacy of crime prevention and the abolition of torture and capital punishment marked a significant advance in criminological thought, which had changed little since the Middle Ages.

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, marquis of Gualdasco and Villaregio (1738-94), was the author of On Crimes and Punishments (1764). Inspired by the discussion of criminal law in Montesquieu's Spirit of the Laws, this Milanese wrote a systematic treatise on the subject that was almost immediately translated into English and French.In it, he argued that the sole purpose of punishment is deterrence ...

Excerpts from An Essay on Crimes and Punishments by Cesare Beccaria translated from the Italian, 1775 (original published in 1764) Introduction In every human society, there is an effort continually tending to confer on one part the height of power and happiness, and to reduce the other to the extreme of weakness and misery.

Of Crimes and Punishments. Cesare Bonesana, Marchese Beccaria, 1738-1794. Originally published in Italian in 1764. Dei delitti e delle pene. English: An essay on crimes and punishments. Written by the Marquis Beccaria, of Milan. With a commentary attributed to Monsieur de Voltaire.

In 1764, he published his famous and influential criminology essay, "On Crimes and Punishments." In 1768, he started a career in economics, which lasted until his death. Early Life

Appears in 14 books from 1768-2004. Page 158 - To show mankind, that crimes are sometimes pardoned, and that punishment is not the necessary consequence, is to nourish the flattering hope of impunity, and is the cause of their considering every punishment inflicted as an act of injustice and oppression. Appears in 31 books from 1800-2004.

Beccaria's very influential "Dei Delitti e delle Pene" was first published in Livorno in 1764, and the first English translation followed in 1767. Beccaria's book brought into the language the phrase "the greatest happiness of the greatest number" and his arguments about crime and punishment, revolutionary in their time, are part and parcel of ...

An essay on crimes and punishments Bookreader Item Preview ... An essay on crimes and punishments by Beccaria, Cesare, marchese di, 1738-1794; Voltaire, 1694-1778. Publication date 1778 Topics Criminal law, Crime, Criminals, Punishment, Capital punishment, Torture, Law reform

Cesare Beccaria was an Italian jurist and politician from an aristocratic family. He is considered a significant Enlightenment thinker, particularly for his Essay on Crimes and Punishments. The treatise argues for the need for reform in the penal system, particularly arguing against arbitrary power, torture and the overuse of capital punishment ...

09. An essay on crimes and punishments. 1775, Printed for F. Newbery. - 4th ed. aaaa. Read Listen. Libraries near you: WorldCat. 08. An essay on crimes and punishments, translated from the Italian: with a commentary, attributed to Mons. de Voltaire, translated from the French ...

Cesare Beccaria's On Crimes and Punishments: the meaning and gen-esis of a jurispolitical pamphlet. History of European Ideas, 2017, 43 (8), pp.884-897. ... sold in over five hundred copies in Italy between July and August 1764 alone, On Crimes and Punishments soon became one of the best-sellers of the Enlightenment upon its first

Cesare Beccaria's influential Treatise on Crimes and Punishments is considered a foundational work in the field of criminology. Three major themes of the Enlightenment run through the Treatise: the idea that the social contract forms the moral and political basis of the work's reformist zeal; the idea that science supports a dispassionate and reasoned appeal for reforms; and the belief ...

View PDF. On Crimes and Punishments by Cesare Beccaria: A Book Review Hamdah Aziz Abbasi* Undergraduate Laws, University of London, United Kingdom1 Email: [email protected] Beccaria was a young, 25 years old, eager to bring reforms in the Italian criminal justice system. His proposed treaties were the first systematically suggested ...

Source: Erom Cesare Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishments, E. D. Ingraham, trans. (Philadelphia: H. Nicklin, 1819),pp.xii,1819,47,5960,9394,104-105,148149. This text is part of the Internet Modern History Sourcebook. The Sourcebook is a collection of public domain and copy-permitted texts for introductory level classes in modern ...

Beccaria's treatise "On Crimes and Punishments" (1764) has become a placeholder for the classical school of thought in criminology, for deterrence-based public policy, for death penalty abolitionism, and for liberal ideals of legality and the rule of law. A source of inspiration for Bentham and Blackstone, an object of praise for Voltaire and the Philosophies, a target of pointed critiques ...

Beccaria's treatise On Crimes and Punishments, ... Search past episodes of Essay on Crimes and Punishments, An by Voltaire and Cesare Beccaria. Embed this search bar to your website PREVIOUS EPISODES Preface by the Translator of M.D. Voltaire's Commentary Sept. 29, 2023 00:04:15 ...