- Campus Library Info.

- ARC Homepage

- Library Resources

- Articles & Databases

- Books & Ebooks

Baker College Research Guides

- Research Guides

- General Education

COM 1010: Composition and Critical Thinking I

- Understanding Genre and Genre Analysis

- The Writing Process

- Essay Organization Help

- Understanding Memoir

- What is a Book Cover (Not an Infographic)?

- Understanding PowerPoint and Presentations

- Understanding Summary

- What is a Response?

- Structuring Sides of a Topic

- Locating Sources

- What is an Annotated Bibliography?

- What is a Peer Review?

- Understanding Images

- What is Literacy?

- What is an Autobiography?

- Shifting Genres

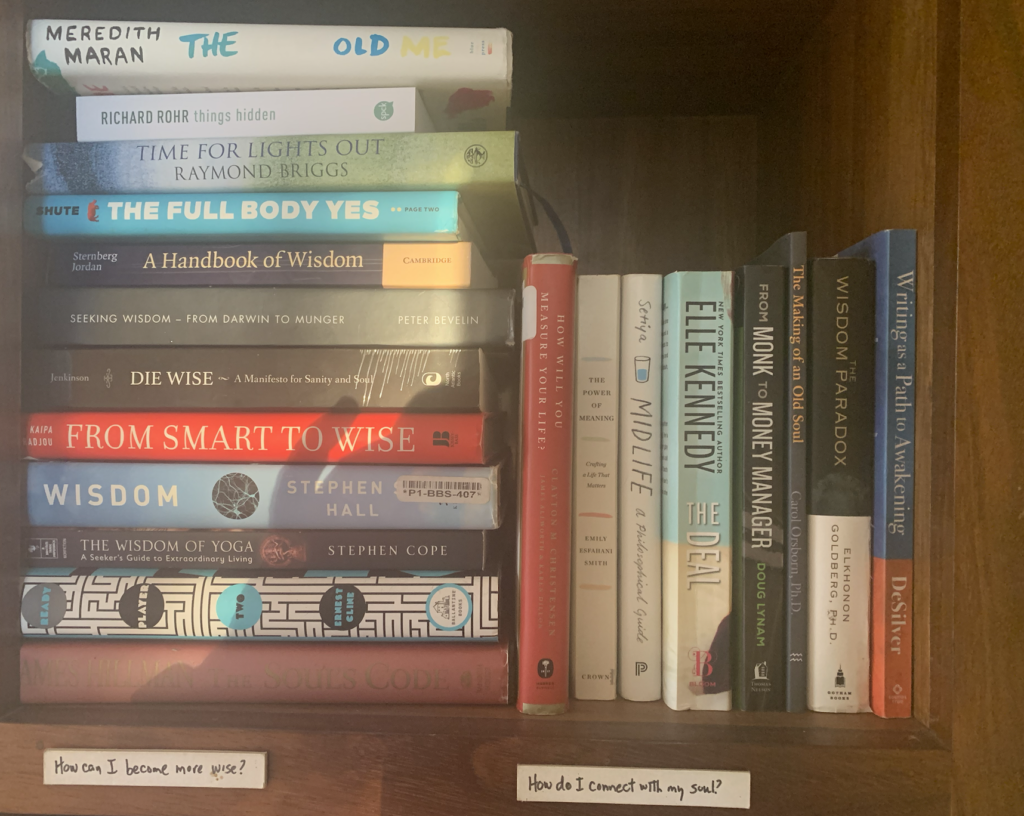

Understanding What is Meant by the Word "Genre"

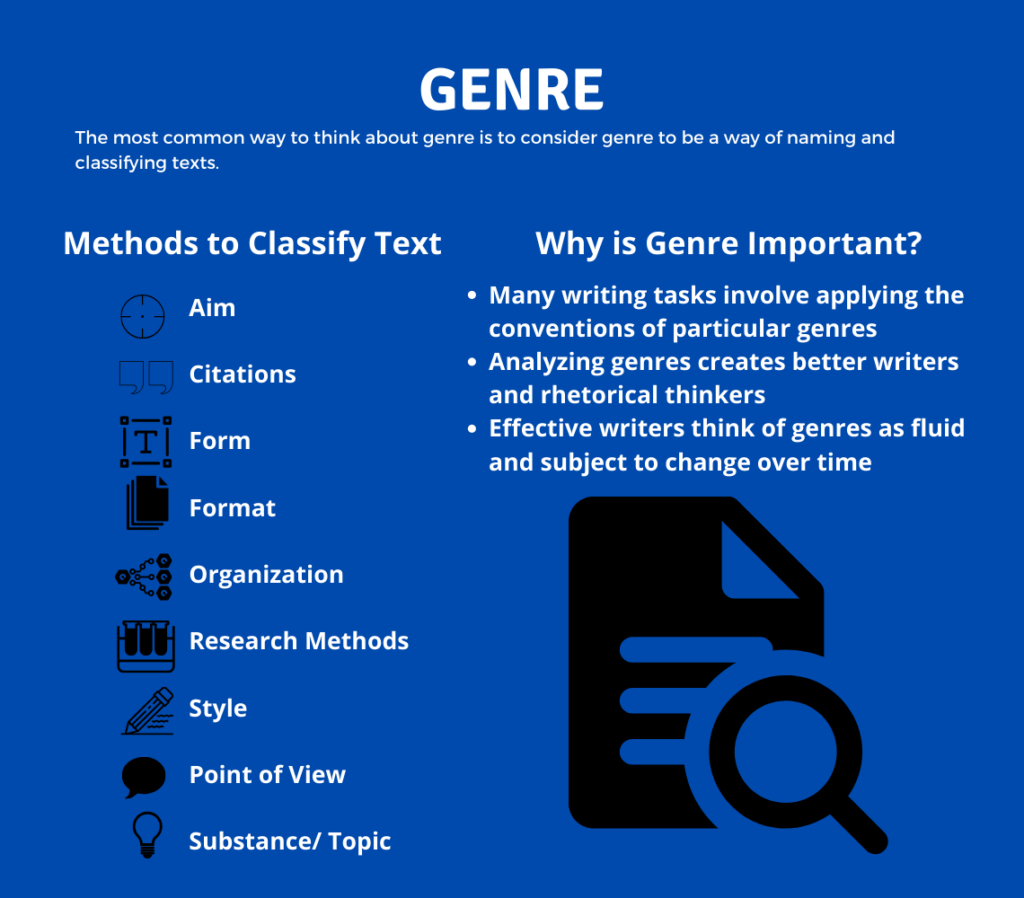

What do we mean by genre? This means a type of writing, i.e., an essay, a poem, a recipe, an email, a tweet. These are all different types (or categories) of writing, and each one has its own format, type of words, tone, and so on. Analyzing a type of writing (or genre) is considered a genre analysis project. A genre analysis grants students the means to think critically about how a particular form of communication functions as well as a means to evaluate it.

Every genre (type of writing/writing style) has a set of conventions that allow that particular genre to be unique. These conventions include the following components:

- Tone: tone of voice, i.e. serious, humorous, scholarly, informal.

- Diction : word usage - formal or informal, i.e. “disoriented” (formal) versus “spaced out” (informal or colloquial).

- Content : what is being discussed/demonstrated in the piece? What information is included or needs to be included?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Short-hand? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Can pictures / should pictures be included? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : where does the genre appear? Where is it created? i.e. can be it be online (digital) or does it need to be in print (computer paper, magazine, etc)? Where does this genre occur? i.e. flyers (mostly) occur in the hallways of our school, and letters of recommendation (mostly) occur in professors’ offices.

- Genre creates an expectation in the minds of its audience and may fail or succeed depending on if that expectation is met or not.

- Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such as magazines and websites.

- The goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

- Basically, each genre has a specific task or a specific goal that it is created to attain.

- Understanding Genre

- Understanding the Rhetorical Situation

To understand genre, one has to first understand the rhetorical situation of the communication.

Below are some additional resources to assist you in this process:

- Reading and Writing for College

Genre Analysis

Genre analysis: A tool used to create genre awareness and understand the conventions of new writing situations and contexts. This a llows you to make effective communication choices and approach your audience and rhetorical situation appropriately

Basically, when we say "genre analysis," that is a fancy way of saying that we are going to look at similar pieces of communication - for example a handful of business memos - and determine the following:

- Tone: What was the overall tone of voice in the samples of that genre (piece of writing)?

- Diction : What was the overall type of writing in the three samples of that genre (piece of writing)? Formal or informal?

- Content : What types(s) of information is shared in those pieces of writing?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): Do the pieces of communication contain long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be in that type of writing style? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Are pictures included? If so, why? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : Where did the pieces appear? Were they online? Where? Were they in a printed, physical context? If so, what?

- Audience: What audience is this piece of writing trying to reach?

- Purpose : What is the goal of the piece of writing? What is its purpose? Example: the goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

In other words, we are analyzing the genre to determine what are some commonalities of that piece of communication.

For additional help, see the following resource for Questions to Ask When Completing a Genre Analysis .

- << Previous: The Writing Process

- Next: Essay Organization Help >>

- Last Updated: Feb 23, 2024 2:08 PM

- URL: https://guides.baker.edu/com1010

- Search this Guide Search

Exploring Different Essay Genres: Your In-Depth Guide

.png)

Essays, as a literary form, have deep historical roots. Their origins can be traced back to ancient Greece and Rome, where philosophers and scholars penned texts that shared knowledge, insights, and reflections. Over the centuries, essays have evolved into a versatile medium for expressing ideas, emotions, and information. This evolution has led to the development of various essay genres, each tailored to serve a distinct purpose.

Imagine the ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle or the Roman statesman and philosopher Seneca using essays to convey their profound thoughts and philosophical musings. Fast forward to modern times, and we see how essays have adapted to our changing world, becoming a cornerstone of communication and education.

Exploring Different Essay Genres: Short Description

In this article, we'll unravel various essay genres, from narrative to expository, argumentative to descriptive, and many more. We'll break them down by explaining what they are and what makes them unique. You'll find examples that show how these essays work in the real world, along with tips to help you become a pro at writing them. Whether you're a student looking to ace your assignments or a writer seeking to sharpen your skills, we've got you covered with all you need to know about different kinds of essays.

What Type of Essays Are There: The Diversity of Essay Genres

Before we dive into the specifics of different essay genres, let's take a moment to appreciate the rich tapestry of essay writing. Essays come in various forms, each with its own unique characteristics and purposes. From narratives that tell compelling stories to expository essays that explain complex topics and persuasive essays that aim to change minds, custom essay writers of our persuasive essay writing service will explore this diverse landscape to help you understand which genre suits your needs and how to master it.

- Essays Are Like Handy Tools : Think of essays as tools that can help you communicate in many different ways. Just like a Swiss Army knife has different functions, essays can be used for various purposes in writing.

- Choose Your Words Wisely : Different situations need different ways of talking or writing. Essays let you choose the best way to say what you want, whether you're telling a personal story, explaining something, or trying to convince someone of your point of view.

- Boost Your Writing Skills : Learning about different essay types can make you a better writer. It can help you write more effectively, whether you're working on a school assignment, a blog post, or an important letter.

- Essays Have Made History : Throughout history, essays have been a big deal. They've shaped our culture and society. From old classics to modern essays, they've had a big impact.

- Stand Out in the Online World : In today's digital world, where there's a lot of information and not much time, knowing how to write different types of essays can help you get noticed. Being good at different styles of writing is a useful skill in a world full of information.

The Descriptive Essay

In a descriptive essay, the objective is to immerse the reader in the experience of what you're describing. For instance, when contemplating how to write an article review , utilizing descriptive writing allows you to vividly depict the subject matter, creating a rich and immersive portrayal through words.

A. Definition and Characteristics

- What is it? A descriptive essay is like a word painting. It uses lots of details and vivid words to create a picture in the reader's mind.

- Characteristics:

- Lots of sensory details: Descriptive essays make you feel like you're right there by using words that describe what you can see, hear, smell, taste, or touch.

- Vivid language and imagery: They use colorful words and phrases to make the reader really imagine what's being described.

B. Examples and Use Cases

- When do we use it? Imagine describing your favorite place, like a cozy cabin in the woods, or a memorable experience, like your first day at school. These are common subjects for descriptive essays.

- Describing a beautiful sunset over the ocean.

- Painting a picture of your childhood home, room by room.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Descriptive Essay

- Show, Don't Tell: Instead of just saying something is 'nice,' show why it's nice by describing the details that make it special.

- Organize Details: Arrange your descriptions in an order that makes sense. Start with the big picture and then focus on the smaller details.

Engage the Senses: Make sure your writing appeals to all the senses. Describe how things look, sound, smell, taste, and feel to create a complete picture.

Ready to Craft a One-of-a-Kind Essay?

Order now for a tailored essay - Our expert wordsmiths are armed with creativity, precision, and a sprinkle of genius!

The Expository Essay

In an expository essay, your job is to be a great teacher. You're presenting information in a way that's easy to understand and follow so the reader can learn something new or gain a deeper insight into a subject.

- What is it? An expository essay is like a friendly explainer. It provides clear and factual information about a topic, idea, or concept.

- It's all about facts: Expository essays rely on solid evidence, data, and information to explain things.

- Clear and organized: They follow a logical structure with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

- When do we use it? Think of when you need to explain something, like how photosynthesis works, how to bake a cake, or the causes of climate change. These topics are perfect for expository essays.

- Explaining the steps to solve a math problem.

- Describing the history and significance of a famous landmark.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Expository Essay

- Clear Thesis Statement: Start with a strong and clear thesis statement that tells the reader what your essay is all about.

- Organized Structure: Divide your essay into clear sections or paragraphs that each cover a specific aspect of the topic.

- Supporting Evidence and Citations: Use reliable sources and provide evidence like facts, statistics, or examples to back up your explanations.

The Argumentative Essay

In this example of essay type, your goal is to persuade the reader to agree with your point of view or take action on a specific issue. It's like being a lawyer presenting your case in court, but instead of a judge and jury, you have your readers.

- What is it? An argumentative essay is like a debate on paper. It's all about taking a clear stance on a controversial topic and providing strong reasons and evidence to support your point of view.

- A strong thesis statement: Argumentative essays start with a clear and assertive thesis statement that tells the reader your position.

- Counter Arguments: They also consider opposing viewpoints and then refute them with evidence.

- When do we use it? Imagine you want to convince someone that your favorite book is the best ever or that recycling should be mandatory. These are situations where you'd use an argumentative essay.

- Arguing for or against a particular law or policy.

- Debating the pros and cons of a controversial technology like artificial intelligence.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Argumentative Essay

- Strong Thesis: Make sure your thesis is clear, specific, and debatable.

- Evidence and Logic: Back up your arguments with solid evidence and use logical reasoning.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge opposing views and explain why your perspective is more valid.

The Narrative Essay

In a narrative essay, you assume the role of the storyteller, guiding your readers through your personal experiences. This style is particularly apt when contemplating how to write a college admission essay . It offers you the opportunity to share a piece of your life story and forge a connection with your audience through the captivating art of storytelling.

- What is it? A narrative essay is like sharing a personal story. It's all about recounting an experience, event, or moment in your life in a way that engages the reader.

- It's personal: Narrative essays often use 'I' because they're about your own experiences.

- Storytelling: They have a beginning, middle, and end, just like a good story.

- When do we use it? Think of moments in your life that you want to share, like a funny incident, a life-changing event, or a memorable trip. These are perfect for narrative essays.

- Sharing a personal childhood memory that taught you a valuable lesson.

- Describing an adventure-filled vacation that had a big impact on your life.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Narrative Essay

- Engaging Start: Begin with a captivating hook to draw the reader into your story.

- Show, Don't Tell: Use descriptive language to help the reader visualize the events and feel the emotions.

- Reflect and Conclude: Wrap up your narrative by reflecting on the experience and why it was meaningful or significant.

The Contrast Essay

In this type of essays, your goal is to help the reader understand how two or more things are distinct from each other. It's a way to bring out the unique qualities of each subject and make comparisons that highlight their differences.

- What is it? A contrast essay is like a spotlight on differences. It's all about showing how two or more things are different from each other.

- Comparison: Contrast essays focus on comparing two or more subjects and highlighting their dissimilarities.

- Clear Structure: They often use a structured format, discussing one point of difference at a time.

- When do we use it? Imagine you want to explain how two cars you're considering for purchase are different, or you're comparing two historical figures for a school project. These are situations where you'd use a contrast essay.

- Contrasting the pros and cons of two different smartphone models.

- Comparing the lifestyles and philosophies of two famous authors.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Contrast Essay

- Choose Clear Criteria: Decide on the specific criteria or aspects you'll use to compare the subjects.

- Organized Structure: Use a clear and organized structure, such as a point-by-point comparison or a subject-by-subject approach.

- Highlight Key Differences: Ensure you emphasize the most significant differences between the subjects.

The Definition Essay

In a definition essay, you take on the role of a language detective, seeking to unravel the intricate layers of meaning behind a term. It's a chance to explore the nuances and variations in how people understand and use a specific word or concept.

- What is it? A definition essay is like a word detective. It's all about explaining the meaning of a specific term or concept, often one that's abstract or open to interpretation.

- Clarity: Definition essays aim to provide a clear, precise, and comprehensive definition of the chosen term.

- Exploration: They explore the various facets, interpretations, and nuances of the term.

- When do we use it? Think of terms or concepts that people might misunderstand or have different opinions about, like 'freedom,' 'happiness,' or 'justice.' These are great candidates for definition essays.

- Defining the concept of 'success' and what it means to different people.

- Exploring the various definitions and interpretations of 'love' in different cultures and contexts.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Definition Essay

- Choose a Complex Term: Select a term that has multiple meanings or interpretations.

- Research and Explore: Investigate the term thoroughly, including its history, etymology, and various definitions.

- Provide Examples: Use real-life examples, anecdotes, or scenarios to illustrate your definition.

The Persuasive Essay

In a persuasive essay, your goal is to be a persuasive speaker through your writing. You're trying to win over your readers and get them to agree with your perspective or take action on a particular issue. It's all about presenting a compelling argument that makes people see things from your point of view.

- What is it? A persuasive essay is like a friendly argument with facts. It's all about convincing the reader to agree with your point of view on a particular topic or issue.

- Strong Opinion: Persuasive essays start with a clear and strong opinion or position.

- Evidence-Based: They rely on solid evidence, logic, and reasoning to support their argument.

- When do we use it? Think of situations where you want to persuade someone to see things your way, like convincing your parents to extend your curfew or advocating for a cause you believe in. These are scenarios where you'd use a persuasive essay.

- Arguing for stricter environmental regulations to combat climate change.

- Convincing readers to support a specific charity or volunteer for a cause.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

- Clear Thesis Statement: Start with a strong thesis statement that clearly states your opinion.

- Evidence and Logic: Back up your arguments with solid evidence, statistics, and logical reasoning.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing views to strengthen your argument.

How to Identify the Genre of an Essay

Identifying the genre of an essay is like deciphering the code that unlocks its purpose and style. This skill is crucial for both readers and writers because it helps set expectations and allows for a deeper understanding of the text. Here are some insightful tips on how to identify the genre of an essay from our thesis writing help :

1. Analyze the Introduction:

- The introductory paragraph often holds valuable clues. Look for keywords, phrases, or hints that reveal the writer's intention. For example, a narrative essay might start with a personal anecdote, while a synthesis essay may introduce a topic with a concise explanation.

2. Examine the Tone and Language

- The tone and language used in the essay provide significant clues. A persuasive essay may employ passionate and convincing language, whereas an informative essay tends to maintain a neutral and factual tone.

3. Check the Structure

- Different genres of essays follow specific structures. Narrative essays typically have a chronological structure, while argumentative essays present a clear thesis and structured arguments. Understanding the essay's organizational pattern can help pinpoint its genre.

4. Consider the Content

- The subject matter and content of the essay can also indicate its genre. Essays discussing personal experiences or emotions often lean towards the narrative or descriptive genre, while those presenting facts and analysis typically fall into the expository or argumentative category.

5. Identify the Author's Intent

- Sometimes, the author's intent becomes apparent when considering why they wrote the essay. Are they trying to entertain, inform, persuade, or reflect on a personal experience? Understanding the author's purpose can be a powerful tool for genre identification.

6. Recognize Genre Blending

- Keep in mind that some essays may blend multiple genres. For instance, a personal essay might incorporate elements of both narrative and descriptive writing. In such cases, it's essential to identify the dominant genre and any secondary influences.

7. Seek Contextual Clues

- Context can provide valuable insights. Consider where you encountered the essay — in a literature class, a news outlet, or a personal blog. The context can often hint at the intended genre.

8. Ask Questions

- Don't hesitate to ask questions as you read. What is the author trying to achieve? Is the focus on storytelling, providing information, arguing a point, or something else? Questions like these can guide you toward identifying the genre.

Final Thoughts

In the tapestry of writing, we've unraveled the threads of diverse essay styles, from the vivid descriptions of the descriptive essay to the informative clarity of expository pieces. Each genre brings its unique charm to the literary world. Embrace this versatility in your own writing journey, adapting your style to engage, inform, and persuade. In the realm of essays, your creative potential has boundless opportunities. Should you ever require help with the request, ' write papers for me ,' you can be confident that our professional writers will deliver an exceptional paper tailored to your needs!

18.1 Mixing Genres and Modes

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Address a range of audiences using a variety of technologies.

- Adapt composing processes for a variety of modalities, including textual and digital compositions.

- Match the capacities of different print and electronic environments to varying rhetorical situations.

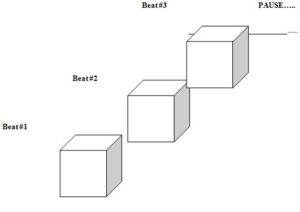

The writing genre for this chapter incorporates a variety of modalities. A genre is a type of composition that encompasses defined features, follows a style or format, and reflects your purpose as a writer. For example, given the composition types romantic comedy , poetry , or documentary , you probably can think easily of features of each of these composition types. When considering the multimodal genres, you will discover that genres create conventions (standard ways of doing things) for categorizing media according to the expectations of the audience and the way the media will be consumed. Consider film media, for example; it encompasses genres including drama, documentaries, and animated shorts, to name a few. Each genre has its own conventions, or features. When you write or analyze multimodal texts, it is important to account for genre conventions.

A note on text: typically, when referring to text, people mean written words. But in multimodal genres, the term text can refer to a piece of communication as a whole, incorporating written words, images, sounds, and even movement. The following images are examples of multimodal texts.

Multimodal genres are uniquely positioned to address audiences through a variety of modes , or types of communication. These can be identified in the following categories:

Linguistic text : The most common mode for writing, the linguistic mode includes written or spoken text.

Visuals : The visual mode includes anything the reader can see, including images, colors, lighting, typefaces, lines, shapes, and backgrounds.

Audio : The audio mode includes all types of sound, such as narration, sound effects, music, silence, and ambient noise.

Spatial : Especially important in digital media, the spatial mode includes spacing, image and text size and position, white space, visual organization, and alignment.

Gestural : The gestural mode includes communication through all kinds of body language, including movement and facial expressions.

Multimodal composition provides an opportunity for you to develop and practice skills that will translate to future coursework and career opportunities. Creating a multimodal text requires you to demonstrate aptitude in various modes and reflects the requirements for communication skills beyond the academic world. In other words, although multimodal creations may seem to be little more than pictures and captions at times, they must be carefully constructed to be effective. Even the simplest compositions are meticulously planned and executed. Multimodal compositions may include written text, such as blog post text, slideshow text, and website content; image-based content, such as infographics and photo essays; or audiovisual content, including podcasts, public service announcements, and videos.

Multimodal composition is especially important in a 21st-century world where communication must represent and transfer across cultural contexts. Because using multiple modes helps a writer make meaning in different channels (media that communicate a message), the availability of different modes is especially important to help you make yourself understood as an author. In academic settings, multimodal content creation increases engagement, improves equity, and helps prepare you to be a global citizen. The same is true for your readers. Multimodal composition is important in addressing and supporting cultural and linguistic diversity. Modes are shaped by social, cultural, and historic factors, all of which influence their use and impact in communication. And it isn’t just readers who benefit from multimodal composition. Combining a variety of modes allows you as a composer to connect to your own lived experiences—the representation of experiences and choices that you have faced in your own life—and helps you develop a unique voice, thus leveraging your knowledge and experiences.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/18-1-mixing-genres-and-modes

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- University Writing Center

- The Writing Mine

How To: Genre Analysis

Although most of us think of music styles when we hear the word “genre,” the word simply means category of items that share the same characteristics, usually in the arts. In this context, however, we are talking about types of texts. Texts can be written, visual, or oral.

For instance, a written genre would be blogs, such as this one, books, or news articles. A visual genre would be cartoons, videos, or posters. An oral genre would be podcasts, speeches, or songs. Each of these genres communicates differently because each genre has different rules.

A genre analysis is an essay where you dissect texts to understand how they are working to communicate their message. This will help you understand that each genre has different requirements and limitations that we, as writers, must be aware of when using that genre to communicate.

Sections of a genre analysis

Like all other essays, a genre analysis has an introduction, body, and conclusion.

In your introduction, you introduce the topic and the texts you’ll be analyzing.

In your body, you do your analysis. This should be your longest section.

In your conclusion, you do a short summary of everything you talked about and include any closing thoughts, such as whether you think the text accomplished its purpose and why.

Content

All professors ask for different things, so make sure to look at their instructions. These are some areas that will help you analyze your text and that you might want to touch base on in your essay (most professors ask for them):

1. Purpose of the text

What did the creator of the text want to achieve with it? Why was the text created? Did something prompt the creator to make the text?

Sometimes, the texts themselves answer these questions. Other times, we get that through clues like the language they use, the platforms the creator chose to spread their text, and so on. Make sure to include in your essay what features of the text led you to your answer.

If we take this blog post as an example, we can say that its purpose is to inform students like you about what a genre analysis is and the content it requires. You probably figured this out through the language I’m using and the information I’m choosing to include.

2. Intended audience

Who is the creator of the text trying to reach? How did you figure that out?

The audience can be as specific as a small group of people interested in a very niche topic or as broad as people curious about a common topic.

With this blog, for example, I’m trying to reach students, particularly UTEP students who have this assignment and are trying to understand it. My causal and informative tone, as well as the fact that the blog is posted on UTEP’s Writing Center blog, probably gave this away.

3. Structure

How is the text organized? How does that help the creator achieve the text’s purpose?

You need to know the information at the top of this blog post to understand what comes after, so this blog post is organized in order of complexity.

4. Genre conventions

Is the text following the usual characteristics of the genre? How is this helping or impeding the text to achieve its purpose?

Like most blogs, this one is using simple language, short paragraphs, and illustrations. My use of all these elements is helping me be clear and specific so you can understand your assignment.

5. Connection

Do the ideas in the text come from somewhere else? Can the reader or consumer interact with the text? Is the text inviting that interaction?

Most of the time, when the ideas come from another source, the text will make that clear by mentioning the text. In terms of interaction possible with the text, think about if it would be easy for you to say something back to the text.

For instance, if you wanted to ask a question about this blog post, you could type it in our comment section. I might not explicitly say that many ideas in this blog come from the guidelines your professor gives you for this assignment, but you probably gathered that because I mention that these areas are things most professors are looking for.

Hopefully, this information helps you tackle your assignment with a clearer idea of what your professor is looking for. Make sure to address any other areas the professor is asking you to.

If you still have questions or want to make sure you are on the right path, come visit us at the University Writing Center.

Connect With Us

The University of Texas at El Paso University Writing Center Library 227 500 W University El Paso, Texas 79902

E: [email protected] P: (915) 747-5112

- Basics for GSIs

- Advancing Your Skills

Writing in a Genre

What kind of paper do you want your students to produce?

It often helps students if you are explicit about the features and rhetorical situation of the papers you want them to write. Remember that in some entering students’ experience, “academic essay” may call to mind a five-paragraph paper giving a summary or opinion. How can you bridge from their previous understanding of formal writing to the understanding they need to develop in your R&C course?

One strategy is to work with the idea of genres. The five-paragraph essay is useful in some contexts, but in college work students are expected to write in multiple academic genres. What are the expectations of the genre you are assigning? You can make your expectations explicit by working through a handout such as the one reproduced below and analyzing an example paper as a class, using the description on the handout. This one emphasizes developing an intellectual voice and framework.

The Genre of Academic Interpretive Argumentation

The task of an academic interpretive argument is to articulate a good case for seeing a text, event, or artifact in a particular way, using the best available evidence and valid reasoning.

Although in the school context it may sometimes seem that students write papers merely for an instructor to grade, really good essays explore an interesting or puzzling question or idea that you can share with others.

Assume that your audience is as well-educated as you are, takes a different perspective, and wants to challenge their understanding by reading your essay. In other words, you are an intelligent person in conversation with another intelligent person through your writing, and the topic interests you both.

Assume that your audience has read the same primary text you have. You do not need to summarize the plot for your reader. Instead, refer to passages briefly — just enough to let the reader know what passage you are analyzing — and focus on what you have to say about the passage.

Interpretive Argumentation

Most really interesting questions or problems are complex and can be approached in a variety of ways. Multiple approaches are possible and yield multiple ways to pose and answer questions. Good interpretive arguments explain why a topic represents a problem from a certain point of view. Identify your argument and from what perspective it makes sense of the problem or question you have chosen.

While there may be many ways to approach a question, all possible answers are not equally good. Some arguments are more plausible and validly presented than others, and some arguments may ignore important, relevant evidence. In developing your question or issue around a topic, you discipline yourself to select the most relevant evidence and to use valid logic, and you anticipate questions your readers might raise and address them as part of your presentation.

Any given essay in this genre does not necessarily reflect its author’s permanent opinion on the topic; the essay is usually more like a snapshot of the author’s best thinking at the time of the writing.

How would you describe the elements of an essay that make sense in your field?

It is also important to show students examples of essays or articles and analyze them closely for the traits you want (and don’t want) to see in students’ work. The full-class discussion and analysis can be followed up with a small-group activity analyzing another short paper, or with a homework assignment in which students compare their own paper or draft with the description of the genre.

Secondary Menu

Genres of writing.

We use the term genres to describe categories of written texts that have recognizable patterns, syntax, techniques, and/or conventions. This list represents genres students can expect to encounter during their time at Duke. The list is not intended to be inclusive of all genres but rather representative of the most common ones. Click on each genre for detailed information (definition, questions to ask, actions to take, and helpful links).

- Abstract (UNC)

- Academic Email

- Annotated Bibliography

- Argument Essay

- Autobiographical Reflection

- Blogs (Introduction)

- Blogs (Academic)

- Book Review

- Business Letter (Purdue)

- Close Reading

- Compare/Contrast: see Relating Multiple Texts

- Concert Review

- Cover Letter

- Creative Non-fiction

- Creative Writing

- Curriculum Vitae

- Essay Exams (Purdue)

- Ethnography

- Film Review

- Grant Proposals (UNC)

- Group Essays

- Letters to the Editor

- Literature Review

- Mission Statement

- Oral Presentations

- Performance Review

- Personal Statement: Humanities

- Personal Statement: Professional School/Scholarship

- Poetry Explication

- Policy Memo

- Presentation: Convert your Paper into a Talk

- Program II Duke Application Tips

- Relating Multiple Texts

- Research and Grant Proposals

- Response/Reaction Paper

- Resume, Non-academic ( useful list of action verbs from Boston College)

- Scientific Article Review

- Scientific Writing for Scientists (quick tips)

- Scientific Writing for Scientists: Improving Clarity

- Scientific Writing for a Popular Audience

- Scientific Jargon

- Timed Essays/Essay Exams

- Visual Analysis

- Job Opportunities

- Location & Directions

- Writing 101: Academic Writing

- "W" Codes

- TWP Writing Studio

- Duke Reader Project

- Writing Resources

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Deliberations 2020: Meet the Authors

- Deliberations 2021: Meet the Authors

- TWP & Duke Kunshan University

- Writing in the Disciplines

- Upcoming WID Pedagogy Workshops

- WID Certificate

- Course Goals and Practices

- Faculty Guide

- First-Year Writing & The Library

- Guidelines for Teaching

- Applying for "W" Code

- Faculty Write Program

- Teaching Excellence Awards

- Writing 101: Course Goals and Practices

- Choosing a Writing 101 Course

- Writing 101 and Civic Engagement

- Applying and Transferring Writing 101 Knowledge

- Approved Electives

- Building on Writing 101

- Crafting Effective Writing Assignments

- Responding to Student Writing

- Thinking & Praxis Workshops

- About the Writing Studio

- What to Expect

- Schedule an Appointment

- View or Cancel an Appointment

- Graduate Writing Lab

- Undergraduate Writing Accountability Group

- Consultant Bios

- Resources for Faculty

- Community Outreach

- Frequently Asked Questions

- About the Faculty Write Program

- Writing Groups

- How I Write

- Course List

- Instructors

- Think-Aloud Responses Examples

- TWP Courses

- Approved Non-TWP Courses

- Graduate Student Instructors

- Faculty Selected Books

- Featured Publications

Florida State University

FSU | Writing Resources

Writing Resources

The English Department

- College Composition

Genre Knowledge: Linking Movies and Music to Genres of Writing

- Genre Scavenger Hunt

Genre and Rhetorical Situation: Choosing an appropriate Genre

- Genre and Reflection Exercise: Using Reflection to Understand Genre

Comparing Digital Genres: Facebook, Twitter, and Text Messaging

Purpose of Exercise: This exercise helps students understand that writers use genre to reach a variety of different audiences (themselves, friends, peers, instructors, employers, parents, and more) with lots of different expectations. To reach an audience effectively, writers need to be flexible -- they need to be able to analyze and make decisions about how to approach any writing situation. Developing genre knowledge prepares students to assess the writing situations they’ll encounter in college and beyond.

Description: Students work in small groups to identify conventions of various movie genres and discuss audience expectations. Each group presents the conventions of their genre to the class, and class discussion allows for identification of similarities/differences/connections between genres. The discussion shifts to genres of music, where conventions are identified but also the “blurriness” of genres is discussed. All this discussion about the familiar – movies and music – gets students to identify what a genre is, how we might define it or at least qualify it, and finally what an audience expects from a particular genre. Students have some confidence about the concept of genre for the next step, the discussion of the less familiar writing genres. In groups, students identify conventions of various genres of writing – the academic essay, a text message, a newsletter, a poster, a web site, a lab report, an obituary, a magazine article – and report back. The class then discusses what these genres include, how they might be defined, and what audiences expect from each genre.

Suggested Time: 30-50 for exercise; plus 20 minutes suggested for journal writing which can be assigned in–class or as homework

Procedure: Divide students into small groups. Assign each group a movie genre (horror, romantic comedy, drama, action, thriller, comedy, documentary, or other). Have students answer the following questions:

- Genre: What are the conventions of your group’s movie genre?

- Audience: Who goes to/rents/watches this type of movie?

- Audience Expectation: What does an audience expect to experience/feel/learn/see from this genre?

- Evidence: Provide 3 examples of movies that fit this type and explain why they fit.

Move to class discussion – ask each group to present their genre while you note their points on the board; once all groups are done, engage in class discussion to add more conventions or expectations, draw connections between genres, and allow students to come up with genres and conventions you did not originally assign.

Next, ask students to look at their iPods or phones or wherever their music is stored. Ask for some favorite songs and write them on the board. Then ask students to define the genre of each, or ask in which genre the song is categorized in their iPod? Continue class discussion by asking for other genres of music, with conventions and song examples. Ask the class to come up with a “genre bleeder” or song that is difficult to categorize (i.e. Jimmy Buffett’s “Margaritaville straddles country and pop, Black–Eyed Peas’ “Boom Boom Pow” straddles R&B, Hip Hop, and Pop, Kid Rock’s “Roll On” is a country song often categorized as Rap because of the artist’s other work). At this point, the instructor may choose to move back to the movie discussion to identify “genre bleeders” but only for a minute or two so the discussion can move to writing.

Next, move the class into a discussion of genres of writing. Ask them to identify different types of writing – from class reading assignments, to writing they do every day, to writing they see in public. Then organize into categories – genres and subgenres – on the board. This exercise often requires more prompting than movies and music – students don’t always think about writing genres when they encounter them. If necessary, break them off into small groups again to identify as many types of writing as they can in 2 minutes. Then come back together.

On the board, as you categorize writing into genres and subgenres, ask students to direct you. Prompt them to consider which genres are parallel and which are subgenres of another. Be sure to ask them for a wide range of examples – genres of fiction, genres of professional writing, genres of personal writing (they never see texting as writing so it’s a good one to start with), etc. As they begin to make sense of writing genres, they will offer more examples. The board should become crowded with examples and arrows drawing connections between genres.

Ask students to identify the one element that is always a factor in deciding on a genre to compose in, whether you are composing in writing, in music, or in film: Audience.

Finally, ask students to complete a journal, in class or as homework. The following prompts can be used:

- How do you define genre?

- Does your definition hold true for movies, music, and writing, or does it differ between media?

- What makes a genre definable, or what makes us able to categorize a genre? Provide an example of a genre of writing and illustrate its categorization.

- List 10 genres of writing you use here at FSU regularly, both in and out of class.

- What are the audiences for the genres you mention above?

- What genre are you writing in now? Define it and identify its audience.

- What is the role of audience in considering genre? Why does audience matter?

Back to Top

Genre scavenger hunt.

Purpose of Exercise: This exercise is a great way to get students actively thinking outside of their understanding of genre in music and movies. It is meant to get them outside of the classroom and up and moving around. More importantly, it is great exercise to show students how writing is public and that writing can take many forms including everyday use. The exercise helps students begin to make connections between the writing they do in the classroom and the writing they do outside the classroom.

Description: Have students in groups of two or three and give them a list of things they must “find” relating to genre within the Williams Building.

Suggested Time: 30-40 minutes; plus 20 min reflection to bring it all together

Procedure: Put students into groups of two or three. Let them know they will be working in these groups and can’t expand to include two groups in one. Tell them they will be doing a “genre scavenger hunt” and in order to complete it they must venture into the halls of Williams. Anywhere in Williams is fair game but they can’t leave the building. The first two teams back wins

**Note: you don’t have to have a “prize” but you can if you would like. Candy works or bonus points on homework on in-class assignments.

**Note: the hunt works best if students use their cell phones to take pictures and videos, but a pen and paper works just as well. So if one group doesn’t have a phone that has these functions they can still participate.

Students need to come back with the following items—

- 5 different examples of genres—they must document them by taking pictures with one of the group members phones. Note: Some examples they could find—someone on a laptop, someone texting, a professor teaching, a literature book, a poster, etc.

- Find one person in the Williams building to define genre theory (they have to get a name of the person)—they must document this by video recording them with their phone or jotting notes while the person talks

- Find an example of an “old” genre and “new” genre—they must document them by taking pictures and jotting down on a piece of notebook paper why they represent old and new genres (these must be different than the 5 examples of genre they found in #1) **Note: newer genres can include digital genres, so for example a picture of a text message

- Find two examples of genres in action in other words find two examples of people working in genres (you can give them a hint: could be someone typing up a note)—they must document them by taking pictures

- Predict a new genre based on your understanding of genre theory

The Reflection: In a quick reflection, respond to the following questions:

What did you learn about genre in the scavenger hunt? Why might the scavenger hunt have been useful? Redefine genre. How, if at all, does your definition of genre keep expanding?

Purpose of Exercise: This exercise helps students understand that genre is linked to rhetorical situation, and that the choice of genre is one a writer must carefully decide using a variety of factors. Key to making the appropriate choice is audience, message, and occasion – all factors in the rhetorical situation. In order for students to write successfully beyond the FYC classroom, they must understand how to make choices appropriate to the writing situation. Understanding the factors that determine the rhetorical situation and how genre and audience connect within each situation, will help students make choices that will lead to successful writing in other contexts.

*Some knowledge of Lloyd Bitzer’s article “The Rhetorical Situation” is especially helpful for this activity—whether it’s the teacher’s familiarity or whether the article is assigned as reading is up to you.

Description: Students work at “stations” in the classroom, using the same overall scenario to write using a different genre for each rhetorical situation the scenario has created. The scenario is a car accident which requires communication to different audiences, and forces students to think about the rhetorical situation and how it changes based on audience and genre.

Suggested Time: 50 minutes; plus 20 minutes suggested for reflection writing which can be assigned in–class or as homework

Procedure: Before class starts, post each scenario (on paper) at different points in the classroom, creating a “writing station” for each. Forcing students to physically move between stations emphasizes the change in rhetorical situation, and it allows students to write at their own pace and collaborate with a new group at each station.

Note: For computer classrooms, adapt this exercise by creating one handout/Discussion Board post that students can use as a guideline to write on computers. Add in a small group discussion about the assignment before they being writing so there is an element of collaboration, the assignment is understood, and questions can be brought up (or stop the class for a minute after each “station” to discuss the next.

(Instructions to give students: A message is communicated successfully if it is received by its intended audience. The message conveyed in two different genres might involve the same content, but the conventions used to communicate this message may be drastically different depending on factors of the rhetorical situation. In this exercise we’ll analyze the ways conventions are used to communicate messages, the underlying assumptions associated with different genres, and the choices we must make when writing based on the audience for which we are writing. For all scenarios, stick to the details in the story provided but tailor your writing appropriately. Write each piece to the specific audience, analyzing before and as you write, how considering your audience and your genre varies.)

Divide students into small groups at each station so everyone starts at different places. Encourage them to collaborate in discussing genre conventions, while the instructor circulates to get involved in the discussion at each station. The overall rhetorical situation is as follows:

Earlier today you were in a car accident while driving your grandmother’s car on your way to take your Biology midterm. Luckily you were not hurt, nor were any others, but your vehicle and another have significant damage and are headed to the repair shop. Since you were texting your friend while driving instead of paying attention, you ran through a red light, so the accident was your fault. Police responded to the scene and your insurance company has been notified. Your grandmother’s car was towed away to get repaired.

Use the following scenarios for each station:

Scenario #1

You now have to write a letter to your grandmother telling her about the accident. Write this in the genre of a letter, whichever of those you would use to communicate with Grandma. Some things to consider as you write:

- What content should be included for this genre? (What information and details are relevant in this letter to your grandmother?)

- What is the style of the language used?

- What format is it written in? How could I tell by looking at it that it is a letter?

Scenario #2

Because of the car accident, you are missing your Biology midterm. Your professor is old and ornery, and you are pretty sure he said “if you miss the midterm or final, your grade is zero - no make-ups” at the beginning of the semester. You are stressed out! By the time the police clear the accident scene, the mid-term is over and you are headed home. Write an email to your Biology professor, explaining what happened and appealing to him for another chance to take the mid-term or to make it up somehow. Write the email, considering the audience and the situation as well as the following:

- What content should be included? What details are relevant? Or too much?

- What style of language should you use for this email?

- What else is appropriate?

Scenario #3

Write a text message to a friend – you are finished at the accident scene and need a ride. Write this in the genre of a txt msg explaining what you need, why, and from where to where. Some things to consider:

- What content should be included for this genre? (What info/details are relevant in a text message?)

- What is the style of the language used in a text message to a friend?

- What format is it written in? How could I tell by looking at it that it is a text message?

Scenario # 4

You are now writing about the accident in the diary/journal you keep to record your thoughts every night before you go to bed. You have had a rough day, and you’re trying to make sense of things before going to sleep. Write this in the genre of a “journal entry.” Some things to keep in mind:

- What content should be included for this genre? What details are relevant?

- What is the style of the language used? Who is the audience?

- What format is it written in? How is it obviously a journal entry?

Scenario #5

You are doing some online research about car accidents a few weeks after your accident happened because it had a big impact on you even though you were unhurt. You stumble across a blog where people share their stories about how car accidents have impacted their lives. There is an open forum for anyone who wants to post an entry to do so. You read about some horrific accidents that left people with permanent damage or loss. You are struck by the fact that your car accident, while inconvenient and a bit scary, was nothing as bad as it might have been. You decide to tell your story. Write a blog entry detailing your experience and explaining its impact on you. Some things to keep in mind:

- What content would you include in this genre? Why?

- What is the style of the language used? What format is it written in?

- What are the conventions of a blog?

- Who is the audience?

Scenario #6

You are assigned an essay for your Psychology class on the topic of human behavior and what makes people change learned habits. The assignment requires that you indicate why the topic is important to you as the writer of it. You decide to write about distracted driving, and you include your story about texting and driving as the introduction, using this personal experience to set the stage for your essay and explain your interest in the topic. It is significant for you because the accident reminds you of another time in your life when you had a close call that left you with a greater sense of appreciation for life. But you still engaged in texting while driving, so it occurs to you that you didn’t learn the lesson. Write the introduction to this Psych essay, keeping the following in mind:

- What genre are you writing in and what are its conventions?

- Who is the audience and what are its expectations?

- What details are relevant to this introduction?

- What does this part of the essay need to do? How will you achieve that goal?

Reflection on Rhetorical Situation and Genre:

Reflect on the experience of writing in different genres for each rhetorical situation. Use the following prompts as a guideline:

- How did you know what was appropriate for each genre?

- For each scenario, how did your audience impact what and how you chose to say?

- Compare any two scenarios and discuss the significant differences in rhetorical situation (discuss purpose, audience, intended outcome, and appropriateness of writing style for each).

- How does your understanding of genre, audience, and rhetorical situation influence the choices you make in writing?

- What 5 elements from this exercise can you apply to a writing assignment you are currently working on in any other class? In other words, what did you learn by doing this that you can now transfer to another writing situation?

Genre and Reflection Exercise: Using Reflection to Understand Genre

Purpose of Exercise: This exercise helps students articulate how genre plays a role in their understanding of their own writing and writing process(es). Using reflection as the method by which they explore their understanding of genre and key terms in writing, students can begin to make connections to how the understanding of genre aids their ability to write more successfully.

Description: This is a four step exercise that normally spans at least two-three class periods and is most often helpful when done during week two or week three of the semester. Additionally, it works best if you have the students read several different readings that are in several different genres. So for example have students read a short memoir, a newspaper article, and an inquiry-based essay as homework during this week of class, so they have a variety of genres that you know they have read.

Note: This activity works well when used alongside the activity “Genre Knowledge: Linking Movies and Music to Genres of Writing.”

Suggested Time: 25-30 minutes per class period; plus 30 min discussion at the end of the second class and a 20 min reflection to bring it all together

Procedure:

**Note: if you do not teach in a computer classroom you can have the students write in a notebook.

Step 1: Key Terms

During the second week of class have students take 20 min or so to respond to the following questions:

In this quick reflection, think about words or terms that you believe are important in creating "good" writing (think about your own writing and your method of writing...what terms would you associate with this?). Generate a list of 5-10 terms and define them. Next give specific examples of authors and/or pieces that you believe use these terms and do so in a good way. Finally, tell why you believe the list you have created is important to writing, specifically your own writing.

After having students generate this list have them hold onto it until the next class.

Step 2: Understanding Genre

Have the students pull up their list from the first day and reflection to the following questions:

If you had to define genre based on your readings and your own understanding of genre, what would that definition be? Think about each of the readings and their specific genre and support your definition with examples from the three readings so far. Be specific. Talk through how each author uses genre.

Step 3: Class Discussion

Lead a class discussion using the following questions as a guideline:

Why is it important that you learn about different genres of writing? Why learn about key terms such as genre, audience, purpose, rhetorical situation, etc? What does it do for your writing to understand these key terms? How do these terms contribute to your development as a writer?

Step 4: Bringing it Together

After the class discussion has the students reflect on the following questions:

Revisit your key terms and your reflection on good writing. How has this changed or morphed? Would you add/delete any key terms—why or why not? Walk through your writing process. How does your new understanding of genre affect your writing process?

Purpose of Exercise: This activity provides students with a chance to develop and apply genre knowledge to digital genres to see how they are both similar to and different from each other and“analogue” genres. By comparing the digital genres of the Facebook status update, the tweet, and the text message, students are able to see how digital writing responds to diverse purposes and audiences.

Description: In this activity, students compare (their own or others’) the Facebook statuses, tweets, and text messages and complete a series of writing and discussion tasks to look at the genres that shape their own (and others’) writing in digital media.

Suggested Time: 20-30 minutes, but flexible

First, have students collect a certain number of Facebook statuses, tweets, and texts messages—either their own or from others. If you are in a computer classroom, this can be done in-class. If not, it may be useful to give students a homework assignment in which they collect—and maybe even print out—these snippets of text.

Next, have students take a moment to write about if and how they use these three kinds of writing. You might prompt them with one (or several) of the following questions:

Do they Facebook? Tweet? Write text messages? When and with what digital technologies? Do they use them for the same purposes? Do they use them for different purposes and in different situations? Who do they plan to reach when they write a Facebook status, tweet, or text message? In short, how do they decide whether to write a Facebook status, tweet, or text?

Third, have students take a minute to write about how these genres are both similar to and different from each other. You might prompt them with one (or several) of the following questions:

What kind of writing does each venue allow you to do? What doesn’t it allow you to do (that is, what constraints does it put on you)? How does each genre allow you to connect texts with each other? How do they incorporate (or not) images? What do you think is the history of this genre?

Finally, bring students together for a discussion and reflection. What kind of patterns emerge as they share what they’ve written? Are there generalizations that can be drawn about the way we use these particular digital genres? And, finally, how do the uses of Facebook statuses, tweets, and text messages differ from the genres they use in school? And why might that be?

Literary Genres: Definition and Examples of the 4 Essential Genres and 100+ Subgenres

by Joe Bunting | 1 comment

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed. Learn more and sign up here.

What are literary genres? Do they actually matter to readers? How about to writers? What types of literary genres exist? And if you're a writer, how do you decide which genre to write in?

To begin to think about literary genres, let's start with an example.

Let's say want to read something. You go to a bookstore or hop onto a store online or go to a library.

But instead of a nice person wearing reading glasses and a cardigan asking you what books you like and then thinking through every book ever written to find you the next perfect read (if that person existed, for the record, they would be my favorite person), you're faced with this: rows and rows of books with labels on the shelves like “Literary Fiction,” “Travel,” “Reference,” “Science Fiction,” and so on.

You stop at the edge of the bookstore and just stand there for a while, stumped. “What do all of these labels even mean?!” And then you walk out of the store.

Or maybe you're writing a book , and someone asks you a question like this: “What kind of book are you writing? What genre is it?”

And you stare at them in frustration thinking, “My book transcends genre, convention, and even reality, obviously. Don't you dare put my genius in a box!”

What are literary genres? In this article, we'll share the definition and different types of literary genres (there are four main ones but thousands of subgenres). Then, we'll talk about why genre matters to both readers and writers. We'll look at some of the components that people use to categorize writing into genres. Finally, we'll give you a chance to put genre into practice with an exercise .

Table of Contents

Introduction Literary Genres Definition Why Genre Matters (to Readers, to Writers) The 4 Essential Genres 100+ Genres and Subgenres The 7 Components of Genre Practice Exercise

Ready to get started? Let's get into it.

What Are Literary Genres? Literary Genre Definition

Let's begin with a basic definition of literary genres:

Literary genres are categories, types, or collections of literature. They often share characteristics, such as their subject matter or topic, style, form, purpose, or audience.

That's our formal definition. But here's a simpler way of thinking about it:

Genre is a way of categorizing readers' tastes.

That's a good basic definition of genre. But does genre really matter?

Why Literary Genres Matter

Literary genres matter. They matter to readers but they also matter to writers. Here's why:

Why Literary Genres Matter to Readers

Think about it. You like to read (or watch) different things than your parents.

You probably also like to read different things at different times of the day. For example, maybe you read the news in the morning, listen to an audiobook of a nonfiction book related to your studies or career in the afternoon, and read a novel or watch a TV show in the evening.

Even more, you probably read different things now than you did as a child or than you will want to read twenty years from now.

Everyone has different tastes.

Genre is one way we match what readers want to what writers want to write and what publishers are publishing.

It's also not a new thing. We've been categorizing literature like this for thousands of years. Some of the oldest forms of writing, including religious texts, were tied directly into this idea of genre.

For example, forty percent of the Old Testament in the Bible is actually poetry, one of the four essential literary genres. Much of the New Testament is in the form of epistle, a subgenre that's basically a public letter.

Genre matters, and by understanding how genre works, you not only can find more things you want to read, you can also better understand what the writer (or publisher) is trying to do.

Why Literary Genres Matter to Writers

Genre isn't just important to readers. It's extremely important to writers too.

In the same way the literary genres better help readers find things they want to read and better understand a writer's intentions, genres inform writers of readers' expectations and also help writers find an audience.

If you know that there are a lot of readers of satirical political punditry (e.g. The Onion ), then you can write more of that kind of writing and thus find more readers and hopefully make more money. Genre can help you find an audience.

At the same time, great writers have always played with and pressed the boundaries of genre, sometimes even subverting it for the sake of their art.

Another way to think about genre is a set of expectations from the reader. While it's important to meet some of those expectations, if you meet too many, the reader will get bored and feel like they know exactly what's going to happen next. So great writers will always play to the readers' expectations and then change a few things completely to give readers a sense of novelty in the midst of familiarity.

This is not unique to writers, by the way. The great apparel designer Virgil Abloh, who was an artistic director at Louis Vuitton until he passed away tragically in 2021, had a creative template called the “3% Rule,” where he would take an existing design, like a pair of Nike Air Jordans, and make a three percent change to it, transforming it into something completely new. His designs were incredibly successful, often selling for thousands of dollars.

This process of taking something familiar and turning it into something new with a slight change is something artists have done throughout history, including writers, and it's a great way to think about how to use genre for your own writing.

What Literary Genre is NOT: Story Type vs. Literary Genres

Before we talk more about the types of genre, let's discuss what genre is not .

Genre is not the same as story type (or for nonfiction, types of nonfiction structure). There are ten (or so) types of stories, including adventure, love story, mystery, and coming of age, but there are hundreds, even thousands of genres.

Story type and nonfiction book structure are about how the work is structured.

Genre is about how the work is perceived and marketed.

These are related but not the same.

For example, one popular subgenre of literature is science fiction. Probably the most common type of science fiction story is adventure, but you can also have mystery sci-fi stories, love story sci-fi, and even morality sci-fi. Story type transcends genre.

You can learn more about this in my book The Write Structure , which teaches writers the simple process to structure great stories. Click to check out The Write Structure .

This is true for non-fiction as well in different ways. More on this in my post on the seven types of nonfiction books .

Now that we've addressed why genre matters and what genre doesn't include, let's get into the different literary genres that exist (there are a lot of them!).

How Many Literary Genres Are There? The 4 Essential Genres, and 100+ Genres and Subgenres

Just as everyone has different tastes, so there are genres to fit every kind of specific reader.

There are four essential literary genres, and all are driven by essential questions. Then, within each of those essential genres are genres and subgenres. We will look at all of these in turn, below, as well as several examples of each.

An important note: There are individual works that fit within the gaps of these four essential genres or even cross over into multiple genres.

As with anything, the edges of these categories can become blurry, for example narrative poetry or fictional reference books.

A general rule: You know it when you see it (except, of course, when the author is trying to trick you!).

1. Nonfiction: Is it true?

The core question for nonfiction is, “Is it true?”

Nonfiction deals with facts, instruction, opinion/argument reference, narrative nonfiction, or a combination.

A few examples of nonfiction (more below): reference, news, memoir, manuals, religious inspirational books, self-help, business, and many more.

2. Fiction: Is it, at some level, imagined?

The core question for fiction is, “Is it, at some level, imagined?”

Fiction is almost always story or narrative. However, satire is a form of “fiction” that's structured like nonfiction opinion/essays or news. And one of the biggest insults you can give to a journalist, reporter, or academic researcher is to suggest that their work is “fiction.”

3. Drama: Is it performed?

Drama is a genre of literature that has some kind of performance component. This includes theater, film, and audio plays.

The core question that defines drama is, “Is it performed?”

As always, there are genres within this essential genre, including horror films, thrillers, true crime podcasts, and more.

4. Poetry: Is it verse?

Poetry is in some ways the most challenging literary genre to define because while poetry is usually based on form, i.e. lines intentionally broken into verse, sometimes including rhyme or other poetic devices, there are some “poems” that are written completely in prose called prose poetry. These are only considered poems because the author and/or literary scholars said they were poems.

To confuse things even more, you also have narrative poetry, which combines fiction and poetry, and song which combines poetry and performance (or drama) with music.

Which is all to say, poetry is challenging to classify, but again, you usually know it when you see it.

Next, let's talk about the genres and subgenres within those four essential literary genres.

The 100+ Literary Genres and Subgenres with Definitions

Genre is, at its core, subjective. It's literally based on the tastes of readers, tastes that change over time, within markets, and across cultures.

Thus, there are essentially an infinite number of genres.

Even more, genres are constantly shifting. What is considered contemporary fiction today will change a decade from now.

So take the lists below (and any list of genres you see) as an incomplete, likely outdated, small sample size of genre with definitions.

1. Fiction Genres

Sorted alphabetically.

Action/Adventure. An action/adventure story has adventure elements in its plot line. This type of story often involves some kind of conflict between good and evil, and features characters who must overcome obstacles to achieve their goals .

Chick Lit. Chick Lit stories are usually written for women who interested in lighthearted stories that still have some depth. They often include romance, humor, and drama in their plots.

Comedy. This typically refers to historical stories and plays (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a happy ending, often with a wedding.

Commercial. Commercial stories have been written for the sole purpose of making money, often in an attempt to cash in on the success of another book, film, or genre.

Crime/Police/Detective Fiction. Crime and police stories feature a detective, whether amateur or professional, who solves crimes using their wits and knowledge of criminal psychology.

Drama or Tragedy. This typically refers to historical stories or plays (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a sad or tragic ending, often with one or more deaths.

Erotica. Erotic stories contain explicit sexual descriptions in their narratives.

Espionage. Espionage stories focus on international intrigue, usually involving governments, spies, secret agents, and/or terrorist organizations. They often involve political conflict, military action, sabotage, terrorism, assassination, kidnapping, and other forms of covert operations.

Family Saga. Family sagas focus on the lives of an extended family, sometimes over several generations. Rather than having an individual protagonist, the family saga tells the stories of multiple main characters or of the family as a whole.

Fantasy. Fantasy stories are set in imaginary worlds that often feature magic, mythical creatures, and fantastic elements. They may be based on mythology, folklore, religion, legend, history, or science fiction.

General Fiction. General fiction novels are those that deal with individuals and relationships in an ordinary setting. They may be set in any time period, but usually take place in modern times.

Graphic Novel. Graphic novels are a hybrid between comics and prose fiction that often includes elements of both.

Historical Fiction. Historical stories are written about imagined or actual events that occurred in history. They usually take place during specific periods of time and often include real or imaginary characters who lived at those times.

Horror Genre. Horror stories focus on the psychological terror experienced by their characters. They often feature supernatural elements, such as ghosts, vampires, werewolves, zombies, demons, monsters, and aliens.

Humor/Satire. This category includes stories that have been written using satire or contain comedic elements. Satirical novels tend to focus on some aspect of society in a critical way.

LGBTQ+. LGBTQ+ novels are those that feature characters who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or otherwise non-heterosexual.

Literary Fiction. Literary fiction novels or stories have a high degree of artistic merit, a unique or experimental style of writing , and often deal with serious themes.

Military. Military stories deal with war, conflict, combat, or similar themes and often have strong action elements. They may be set in a contemporary or a historical period.

Multicultural. Multicultural stories are written by and about people who have different cultural backgrounds, including those that may be considered ethnic minorities.

Mystery G enre. Mystery stories feature an investigation into a crime.

Offbeat/Quirky. An offbeat story has an unusual plot, characters, setting, style, tone, or point of view. Quirkiness can be found in any aspect of a story, but often comes into play when the author uses unexpected settings, time periods, or characters.

Picture Book. Picture book novels are usually written for children and feature simple plots and colorful illustrations . They often have a moral or educational purpose.

Religious/Inspirational. Religious/ inspirational stories describe events in the life of a person who was inspired by God or another supernatural being to do something extraordinary. They usually have a moral lesson at their core.

Romance Genre. Romance novels or stories are those that focus on love between two people, often in an ideal setting. There are many subgenres in romance, including historical, contemporary, paranormal, and others.

Science Fiction. Science fiction stories are usually set in an imaginary future world, often involving advanced technology. They may be based on scientific facts but they are not always.

Short Story Collection . Short story collections contain several short stories written by the same or different authors.

Suspense or Thriller Genre. Thrillers/ suspense stories are usually about people in danger, often involving crimes, natural disasters, or terrorism.

Upmarket. Upmarket stories are often written for and/or focus on upper class people who live in an upscale environment.