Critical Cases in Organisational Behaviour

- J. Martin Corbett

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Part of the book series: Management, Work and Organisations (MWO)

1717 Accesses

18 Citations

- Table of contents

About this book

About the author, bibliographic information.

- Publish with us

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check for access.

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, case study analysis of organisational behaviour, analysing individual behaviour in organisations, the meaning of work, motivation and commitment, the management of meaning, motivation and commitment, analysing group behaviour in organisations, interpersonal relations and group decision-making, analysing organisational behaviour, inter-group relations, organisational design and change, technology and organisation, analysing organisational environments, organisation and environment, back matter.

- organization

- problem solving

Book Title : Critical Cases in Organisational Behaviour

Authors : J. Martin Corbett

Series Title : Management, Work and Organisations

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-23295-6

Publisher : Palgrave London

eBook Packages : Palgrave Business & Management Collection

Copyright Information : Macmillan Publishers Limited 1994

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XI, 304

Topics : Organization , Industrial, Organisational and Economic Psychology

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

7.4 Recent Research on Motivation Theories

- Describe the modern advancements in the study of human motivation.

Employee motivation continues to be a major focus in organizational behavior. 35 We briefly summarize current motivation research here.

Content Theories

There is some interest in testing content theories (including Herzberg’s two-factor theory), especially in international research. Need theories are still generally supported, with most people identifying such workplace factors as recognition, advancement, and opportunities to learn as the chief motivators for them. This is consistent with need satisfaction theories. However, most of this research does not include actual measures of employee performance. Thus, questions remain about whether the factors that employees say motivate them to perform actually do.

Operant Conditioning Theory

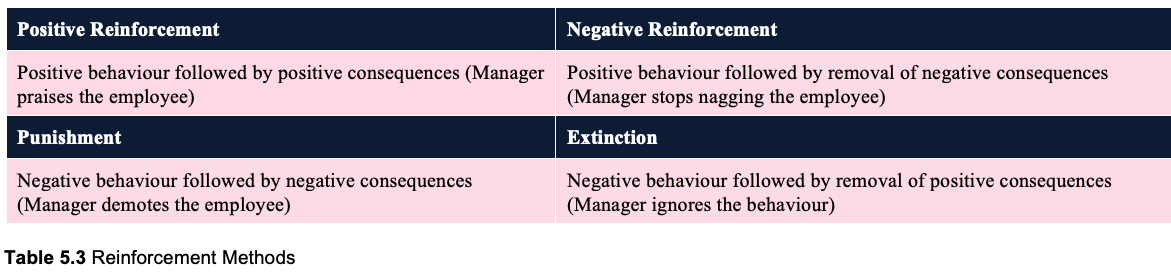

There is considerable interest in operant conditioning theory, especially within the context of what has been called organizational behavior modification. Oddly enough, there has not been much research using operant conditioning theory in designing reward systems, even though there are obvious applications. Instead, much of the recent research on operant conditioning focuses on punishment and extinction. These studies seek to determine how to use punishment appropriately. Recent results still confirm that punishment should be used sparingly, should be used only after extinction does not work, and should not be excessive or destructive.

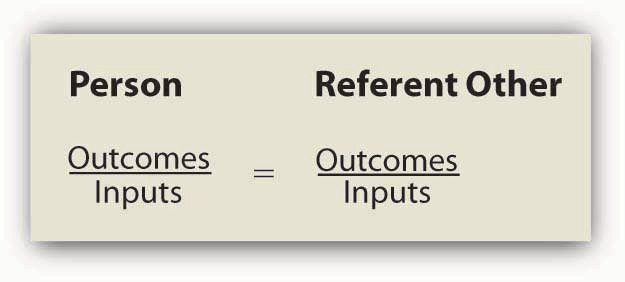

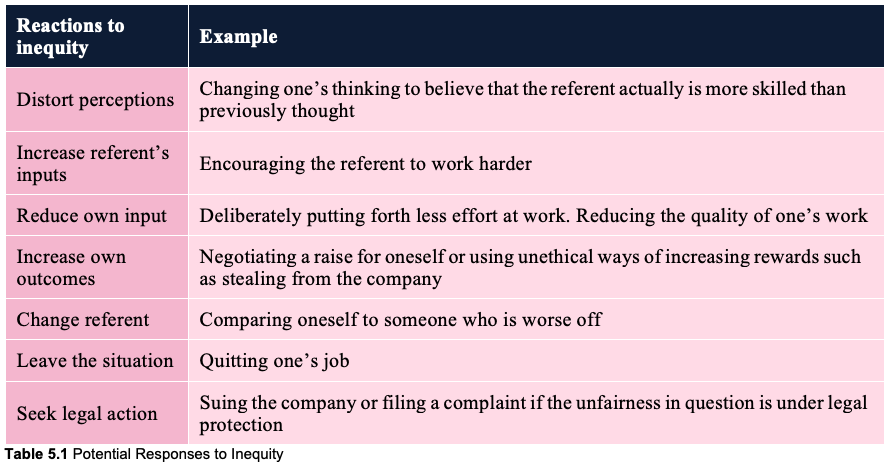

Equity Theory

Equity theory continues to receive strong research support. The major criticism of equity theory, that the inputs and outcomes people use to evaluate equity are ill-defined, still holds. Because each person defines inputs and outcomes, researchers are not in a position to know them all. Nevertheless, for the major inputs (performance) and outcomes (pay), the theory is a strong one. Major applications of equity theory in recent years incorporate and extend the theory into the area called organizational justice. When employees receive rewards (or punishments), they evaluate them in terms of their fairness (as discussed earlier). This is distributive justice. Employees also assess rewards in terms of how fair the processes used to distribute them are. This is procedural justice. Thus during organizational downsizing, when employees lose their jobs, people ask whether the loss of work is fair (distributive justice). But they also assess the fairness of the process used to decide who is laid off (procedural justice). For example, layoffs based on seniority may be perceived as more fair than layoffs based on supervisors’ opinions.

Goal Theory

It remains true that difficult, specific goals result in better performance than easy and vague goals, assuming they are accepted. Recent research highlights the positive effects of performance feedback and goal commitment in the goal-setting process. Monetary incentives enhance motivation when they are tied to goal achievement, by increasing the level of goal commitment. There are negative sides to goal theory as well. If goals conflict, employees may sacrifice performance on important job duties. For example, if both quantitative and qualitative goals are set for performance, employees may emphasize quantity because this goal achievement is more visible.

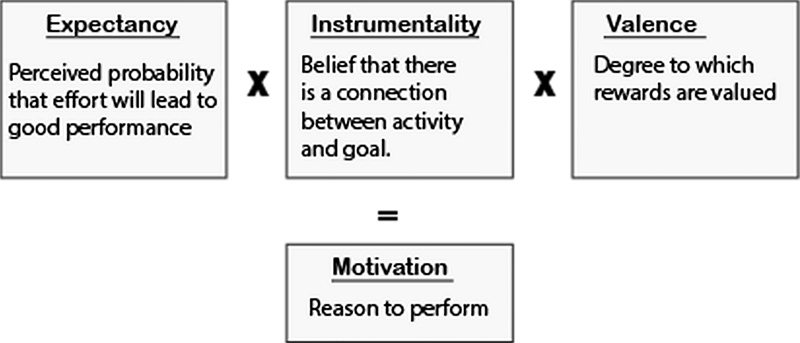

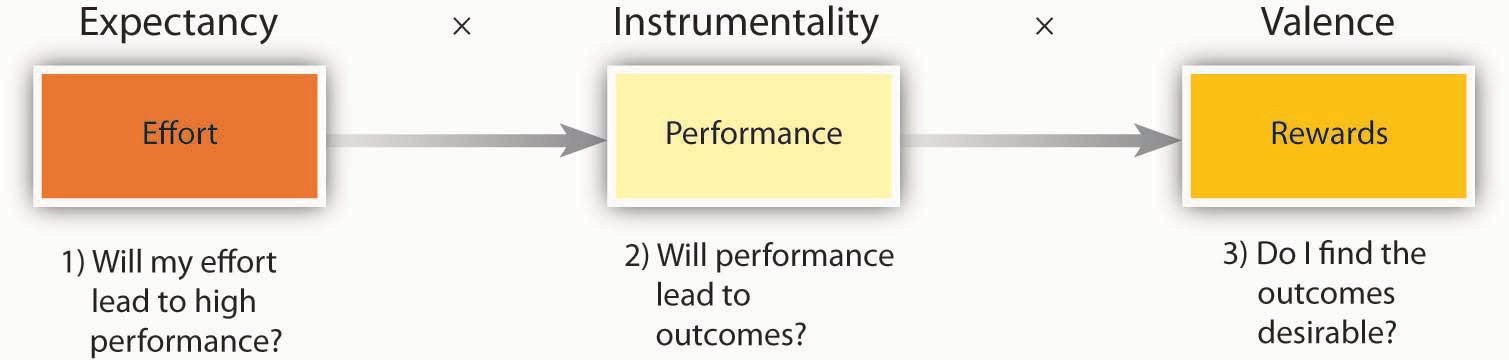

Expectancy Theory

The original formulation of expectancy theory specifies that the motivational force for choosing a level of effort is a function of the multiplication of expectancies and valences. Recent research demonstrates that the individual components predict performance just as well, without being multiplied. This does not diminish the value of expectancy theory. Recent research also suggests that high performance results not only when the valence is high, but also when employees set difficult goals for themselves.

One last comment on motivation: As the world of work changes, so will the methods organizations use to motivate employees. New rewards—time off instead of bonuses; stock options; on-site gyms, cleaners, and dental services; opportunities to telecommute; and others—will need to be created in order to motivate employees in the future. One useful path that modern researchers can undertake is to analyze the previous studies and aggregate the findings into more conclusive understanding of the topic through meta-analysis studies. 36

Catching the Entrepreneurial Spirit

Entrepreneurs and motivation.

Motivation can be difficult to elicit in employees. So what drives entrepreneurs, who by definition have to motivate themselves as well as others? While everyone from Greek philosophers to football coaches warn about undirected passion, a lack of passion will likely kill any start-up. An argument could be made that motivation is simply part of the discipline, or the outcome of remaining fixed on a purpose to mentally remind yourself of why you get up in the morning.

Working from her home in Egypt, at age 30 Yasmine El-Mehairy launched Supermama.me, a start-up aimed at providing information to mothers throughout the Arab world. When the company began, El-Mehairy worked full time at her day job and 60 hours a week after that getting the site established. She left her full-time job to manage the site full time in January 2011, and the site went live that October. El-Mehairy is motivated to keep moving forward, saying that if she stops, she might not get going again (Knowledge @ Wharton 2012).

For El-Mehairy, the motivation didn’t come from a desire to work for a big company or travel the world and secure a master’s degree from abroad. She had already done that. Rather, she said she was motivated to “do something that is useful and I want to do something on my own” (Knowledge @ Wharton 2012 n.p.).

Lauren Lipcon, who founded a company called Injury Funds Now, attributes her ability to stay motivated to three factors: purpose, giving back, and having fun outside of work. Lipcon believes that most entrepreneurs are not motivated by money, but by a sense of purpose. Personally, she left a job with Arthur Andersen to begin her own firm out of a desire to help people. She also thinks it is important for people to give back to their communities because the change the entrepreneur sees in the community loops back, increasing motivation and making the business more successful. Lipcon believes that having a life outside of work helps keep the entrepreneur motivated. She particularly advocates for physical activity, which not only helps the body physically, but also helps keep the mind sharp and able to focus (Rashid 2017).

But do all entrepreneurs agree on what motivates them? A July 17, 2017 survey on the hearpreneur blog site asked 23 different entrepreneurs what motivated them. Seven of the 23 referred to some sense of purpose in what they were doing as a motivating factor, with one response stressing the importance of discovering one’s “personal why.” Of the remaining entrepreneurs, answers varied from keeping a positive attitude (three responses) and finding external sources (three responses) to meditation and prayer (two responses). One entrepreneur said his greatest motivator was fear: the fear of being in the same place financially one year in the future “causes me to take action and also alleviates my fear of risk” (Hear from Entrepreneurs 2017 n.p.). Only one of the 23 actually cited money and material success as a motivating factor to keep working.

However it is described, entrepreneurs seem to agree that passion and determination are key factors that carry them through the grind of the day-to-day.

Hear from Entrepreneurs. 2017. “23 Entrepreneurs Explain Their Motivation or if ‘Motivation is Garbage.’” https://hear.ceoblognation.com/2017/07/17/23-entrepreneurs-explain-motivation-motivation-garbage/

Knowledge @ Wharton. 2012. “The Super-motivated Entrepreneur Behind Egypt’s SuperMama.” http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/the-super-motivated-entrepreneur-behind-egypts-supermama/

Rashid, Brian. 2017. “How This Entrepreneur Sustains High Levels of Energy and Motivation.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brianrashid/2017/05/26/how-this-entrepreneur-sustains-high-levels-of-energy-and-motivation/2/#2a8ec5591111

- In the article from Hear from Entrepreneurs, one respondent called motivation “garbage”? Would you agree or disagree, and why?

- How is staying motivated as an entrepreneur similar to being motivated to pursue a college degree? Do you think the two are related? How?

- How would you expect motivation to vary across cultures?[/BOX]

Concept Check

- Understand the modern approaches to motivation theory.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: J. Stewart Black, David S. Bright

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Organizational Behavior

- Publication date: Jun 5, 2019

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/pages/7-4-recent-research-on-motivation-theories

© Jan 9, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

The Science of Improving Motivation at Work

The topic of employee motivation can be quite daunting for managers, leaders, and human resources professionals.

Organizations that provide their members with meaningful, engaging work not only contribute to the growth of their bottom line, but also create a sense of vitality and fulfillment that echoes across their organizational cultures and their employees’ personal lives.

“An organization’s ability to learn, and translate that learning into action rapidly, is the ultimate competitive advantage.”

In the context of work, an understanding of motivation can be applied to improve employee productivity and satisfaction; help set individual and organizational goals; put stress in perspective; and structure jobs so that they offer optimal levels of challenge, control, variety, and collaboration.

This article demystifies motivation in the workplace and presents recent findings in organizational behavior that have been found to contribute positively to practices of improving motivation and work life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

Motivation in the workplace, motivation theories in organizational behavior, employee motivation strategies, motivation and job performance, leadership and motivation, motivation and good business, a take-home message.

Motivation in the workplace has been traditionally understood in terms of extrinsic rewards in the form of compensation, benefits, perks, awards, or career progression.

With today’s rapidly evolving knowledge economy, motivation requires more than a stick-and-carrot approach. Research shows that innovation and creativity, crucial to generating new ideas and greater productivity, are often stifled when extrinsic rewards are introduced.

Daniel Pink (2011) explains the tricky aspect of external rewards and argues that they are like drugs, where more frequent doses are needed more often. Rewards can often signal that an activity is undesirable.

Interesting and challenging activities are often rewarding in themselves. Rewards tend to focus and narrow attention and work well only if they enhance the ability to do something intrinsically valuable. Extrinsic motivation is best when used to motivate employees to perform routine and repetitive activities but can be detrimental for creative endeavors.

Anticipating rewards can also impair judgment and cause risk-seeking behavior because it activates dopamine. We don’t notice peripheral and long-term solutions when immediate rewards are offered. Studies have shown that people will often choose the low road when chasing after rewards because addictive behavior is short-term focused, and some may opt for a quick win.

Pink (2011) warns that greatness and nearsightedness are incompatible, and seven deadly flaws of rewards are soon to follow. He found that anticipating rewards often has undesirable consequences and tends to:

- Extinguish intrinsic motivation

- Decrease performance

- Encourage cheating

- Decrease creativity

- Crowd out good behavior

- Become addictive

- Foster short-term thinking

Pink (2011) suggests that we should reward only routine tasks to boost motivation and provide rationale, acknowledge that some activities are boring, and allow people to complete the task their way. When we increase variety and mastery opportunities at work, we increase motivation.

Rewards should be given only after the task is completed, preferably as a surprise, varied in frequency, and alternated between tangible rewards and praise. Providing information and meaningful, specific feedback about the effort (not the person) has also been found to be more effective than material rewards for increasing motivation (Pink, 2011).

They have shaped the landscape of our understanding of organizational behavior and our approaches to employee motivation. We discuss a few of the most frequently applied theories of motivation in organizational behavior.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Frederick Herzberg’s (1959) two-factor theory of motivation, also known as dual-factor theory or motivation-hygiene theory, was a result of a study that analyzed responses of 200 accountants and engineers who were asked about their positive and negative feelings about their work. Herzberg (1959) concluded that two major factors influence employee motivation and satisfaction with their jobs:

- Motivator factors, which can motivate employees to work harder and lead to on-the-job satisfaction, including experiences of greater engagement in and enjoyment of the work, feelings of recognition, and a sense of career progression

- Hygiene factors, which can potentially lead to dissatisfaction and a lack of motivation if they are absent, such as adequate compensation, effective company policies, comprehensive benefits, or good relationships with managers and coworkers

Herzberg (1959) maintained that while motivator and hygiene factors both influence motivation, they appeared to work entirely independently of each other. He found that motivator factors increased employee satisfaction and motivation, but the absence of these factors didn’t necessarily cause dissatisfaction.

Likewise, the presence of hygiene factors didn’t appear to increase satisfaction and motivation, but their absence caused an increase in dissatisfaction. It is debatable whether his theory would hold true today outside of blue-collar industries, particularly among younger generations, who may be looking for meaningful work and growth.

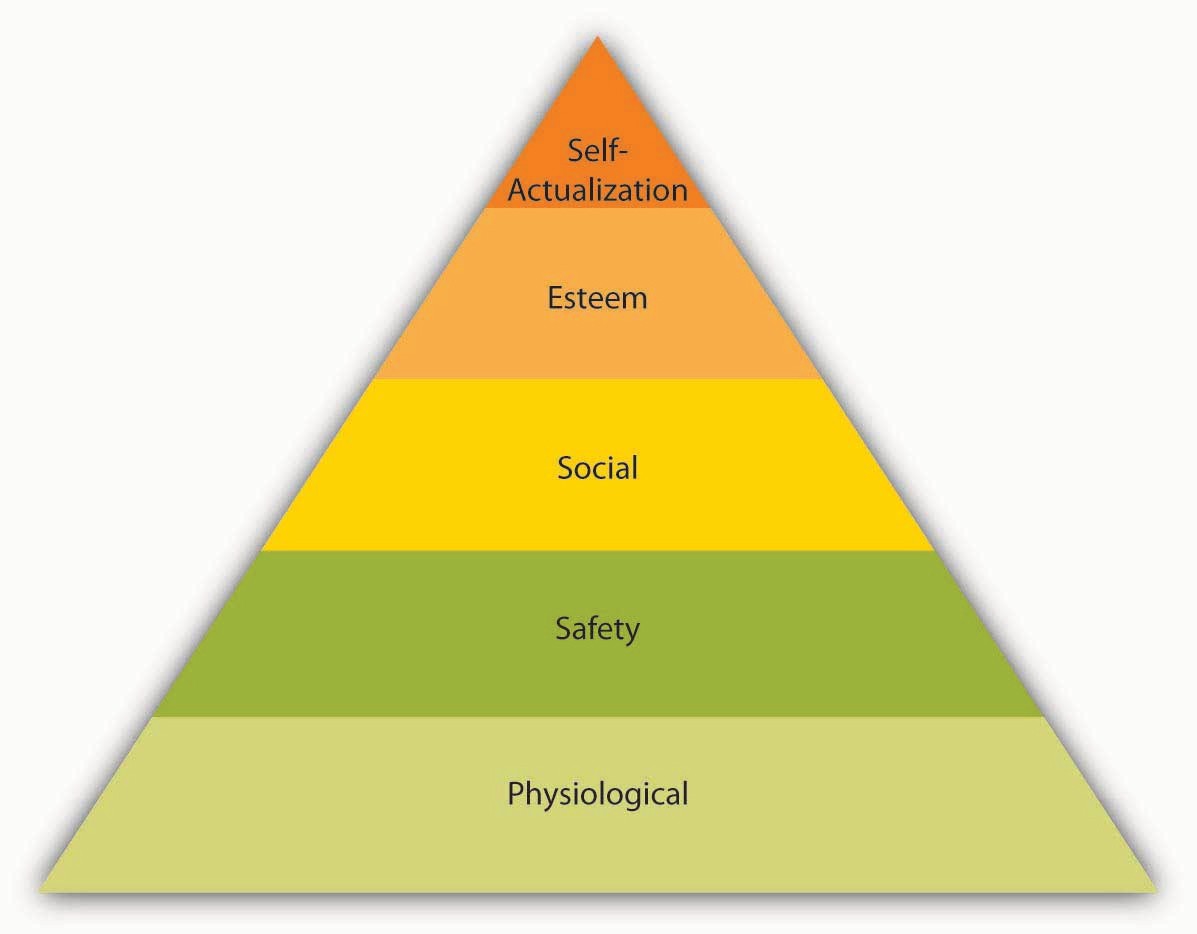

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory proposed that employees become motivated along a continuum of needs from basic physiological needs to higher level psychological needs for growth and self-actualization . The hierarchy was originally conceptualized into five levels:

- Physiological needs that must be met for a person to survive, such as food, water, and shelter

- Safety needs that include personal and financial security, health, and wellbeing

- Belonging needs for friendships, relationships, and family

- Esteem needs that include feelings of confidence in the self and respect from others

- Self-actualization needs that define the desire to achieve everything we possibly can and realize our full potential

According to the hierarchy of needs, we must be in good health, safe, and secure with meaningful relationships and confidence before we can reach for the realization of our full potential.

For a full discussion of other theories of psychological needs and the importance of need satisfaction, see our article on How to Motivate .

Hawthorne effect

The Hawthorne effect, named after a series of social experiments on the influence of physical conditions on productivity at Western Electric’s factory in Hawthorne, Chicago, in the 1920s and 30s, was first described by Henry Landsberger in 1958 after he noticed some people tended to work harder and perform better when researchers were observing them.

Although the researchers changed many physical conditions throughout the experiments, including lighting, working hours, and breaks, increases in employee productivity were more significant in response to the attention being paid to them, rather than the physical changes themselves.

Today the Hawthorne effect is best understood as a justification for the value of providing employees with specific and meaningful feedback and recognition. It is contradicted by the existence of results-only workplace environments that allow complete autonomy and are focused on performance and deliverables rather than managing employees.

Expectancy theory

Expectancy theory proposes that we are motivated by our expectations of the outcomes as a result of our behavior and make a decision based on the likelihood of being rewarded for that behavior in a way that we perceive as valuable.

For example, an employee may be more likely to work harder if they have been promised a raise than if they only assumed they might get one.

Expectancy theory posits that three elements affect our behavioral choices:

- Expectancy is the belief that our effort will result in our desired goal and is based on our past experience and influenced by our self-confidence and anticipation of how difficult the goal is to achieve.

- Instrumentality is the belief that we will receive a reward if we meet performance expectations.

- Valence is the value we place on the reward.

Expectancy theory tells us that we are most motivated when we believe that we will receive the desired reward if we hit an achievable and valued target, and least motivated if we do not care for the reward or do not believe that our efforts will result in the reward.

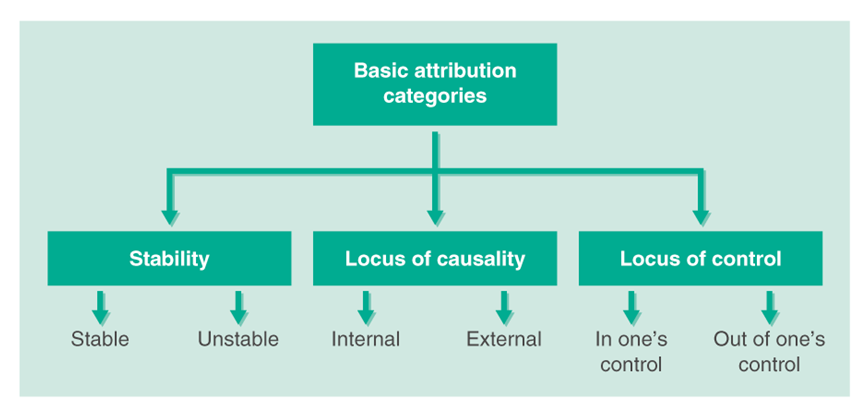

Three-dimensional theory of attribution

Attribution theory explains how we attach meaning to our own and other people’s behavior and how the characteristics of these attributions can affect future motivation.

Bernard Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution proposes that the nature of the specific attribution, such as bad luck or not working hard enough, is less important than the characteristics of that attribution as perceived and experienced by the individual. According to Weiner, there are three main characteristics of attributions that can influence how we behave in the future:

Stability is related to pervasiveness and permanence; an example of a stable factor is an employee believing that they failed to meet the expectation because of a lack of support or competence. An unstable factor might be not performing well due to illness or a temporary shortage of resources.

“There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.”

Colin Powell

According to Weiner, stable attributions for successful achievements can be informed by previous positive experiences, such as completing the project on time, and can lead to positive expectations and higher motivation for success in the future. Adverse situations, such as repeated failures to meet the deadline, can lead to stable attributions characterized by a sense of futility and lower expectations in the future.

Locus of control describes a perspective about the event as caused by either an internal or an external factor. For example, if the employee believes it was their fault the project failed, because of an innate quality such as a lack of skills or ability to meet the challenge, they may be less motivated in the future.

If they believe an external factor was to blame, such as an unrealistic deadline or shortage of staff, they may not experience such a drop in motivation.

Controllability defines how controllable or avoidable the situation was. If an employee believes they could have performed better, they may be less motivated to try again in the future than someone who believes that factors outside of their control caused the circumstances surrounding the setback.

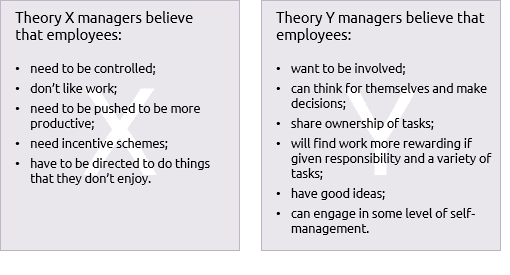

Theory X and theory Y

Douglas McGregor proposed two theories to describe managerial views on employee motivation: theory X and theory Y. These views of employee motivation have drastically different implications for management.

He divided leaders into those who believe most employees avoid work and dislike responsibility (theory X managers) and those who say that most employees enjoy work and exert effort when they have control in the workplace (theory Y managers).

To motivate theory X employees, the company needs to push and control their staff through enforcing rules and implementing punishments.

Theory Y employees, on the other hand, are perceived as consciously choosing to be involved in their work. They are self-motivated and can exert self-management, and leaders’ responsibility is to create a supportive environment and develop opportunities for employees to take on responsibility and show creativity.

Theory X is heavily informed by what we know about intrinsic motivation and the role that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs plays in effective employee motivation.

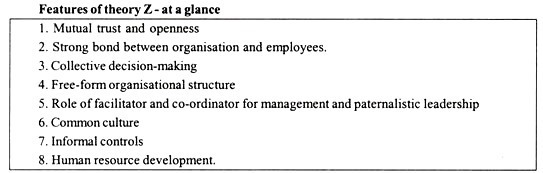

Taking theory X and theory Y as a starting point, theory Z was developed by Dr. William Ouchi. The theory combines American and Japanese management philosophies and focuses on long-term job security, consensual decision making, slow evaluation and promotion procedures, and individual responsibility within a group context.

Its noble goals include increasing employee loyalty to the company by providing a job for life, focusing on the employee’s wellbeing, and encouraging group work and social interaction to motivate employees in the workplace.

There are several implications of these numerous theories on ways to motivate employees. They vary with whatever perspectives leadership ascribes to motivation and how that is cascaded down and incorporated into practices, policies, and culture.

The effectiveness of these approaches is further determined by whether individual preferences for motivation are considered. Nevertheless, various motivational theories can guide our focus on aspects of organizational behavior that may require intervening.

Herzberg’s two-factor theory , for example, implies that for the happiest and most productive workforce, companies need to work on improving both motivator and hygiene factors.

The theory suggests that to help motivate employees, the organization must ensure that everyone feels appreciated and supported, is given plenty of specific and meaningful feedback, and has an understanding of and confidence in how they can grow and progress professionally.

To prevent job dissatisfaction, companies must make sure to address hygiene factors by offering employees the best possible working conditions, fair pay, and supportive relationships.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs , on the other hand, can be used to transform a business where managers struggle with the abstract concept of self-actualization and tend to focus too much on lower level needs. Chip Conley, the founder of the Joie de Vivre hotel chain and head of hospitality at Airbnb, found one way to address this dilemma by helping his employees understand the meaning of their roles during a staff retreat.

In one exercise, he asked groups of housekeepers to describe themselves and their job responsibilities by giving their group a name that reflects the nature and the purpose of what they were doing. They came up with names such as “The Serenity Sisters,” “The Clutter Busters,” and “The Peace of Mind Police.”

These designations provided a meaningful rationale and gave them a sense that they were doing more than just cleaning, instead “creating a space for a traveler who was far away from home to feel safe and protected” (Pattison, 2010). By showing them the value of their roles, Conley enabled his employees to feel respected and motivated to work harder.

The Hawthorne effect studies and Weiner’s three-dimensional theory of attribution have implications for providing and soliciting regular feedback and praise. Recognizing employees’ efforts and providing specific and constructive feedback in the areas where they can improve can help prevent them from attributing their failures to an innate lack of skills.

Praising employees for improvement or using the correct methodology, even if the ultimate results were not achieved, can encourage them to reframe setbacks as learning opportunities. This can foster an environment of psychological safety that can further contribute to the view that success is controllable by using different strategies and setting achievable goals .

Theories X, Y, and Z show that one of the most impactful ways to build a thriving organization is to craft organizational practices that build autonomy, competence, and belonging. These practices include providing decision-making discretion, sharing information broadly, minimizing incidents of incivility, and offering performance feedback.

Being told what to do is not an effective way to negotiate. Having a sense of autonomy at work fuels vitality and growth and creates environments where employees are more likely to thrive when empowered to make decisions that affect their work.

Feedback satisfies the psychological need for competence. When others value our work, we tend to appreciate it more and work harder. Particularly two-way, open, frequent, and guided feedback creates opportunities for learning.

Frequent and specific feedback helps people know where they stand in terms of their skills, competencies, and performance, and builds feelings of competence and thriving. Immediate, specific, and public praise focusing on effort and behavior and not traits is most effective. Positive feedback energizes employees to seek their full potential.

Lack of appreciation is psychologically exhausting, and studies show that recognition improves health because people experience less stress. In addition to being acknowledged by their manager, peer-to-peer recognition was shown to have a positive impact on the employee experience (Anderson, 2018). Rewarding the team around the person who did well and giving more responsibility to top performers rather than time off also had a positive impact.

Stop trying to motivate your employees – Kerry Goyette

Other approaches to motivation at work include those that focus on meaning and those that stress the importance of creating positive work environments.

Meaningful work is increasingly considered to be a cornerstone of motivation. In some cases, burnout is not caused by too much work, but by too little meaning. For many years, researchers have recognized the motivating potential of task significance and doing work that affects the wellbeing of others.

All too often, employees do work that makes a difference but never have the chance to see or to meet the people affected. Research by Adam Grant (2013) speaks to the power of long-term goals that benefit others and shows how the use of meaning to motivate those who are not likely to climb the ladder can make the job meaningful by broadening perspectives.

Creating an upbeat, positive work environment can also play an essential role in increasing employee motivation and can be accomplished through the following:

- Encouraging teamwork and sharing ideas

- Providing tools and knowledge to perform well

- Eliminating conflict as it arises

- Giving employees the freedom to work independently when appropriate

- Helping employees establish professional goals and objectives and aligning these goals with the individual’s self-esteem

- Making the cause and effect relationship clear by establishing a goal and its reward

- Offering encouragement when workers hit notable milestones

- Celebrating employee achievements and team accomplishments while avoiding comparing one worker’s achievements to those of others

- Offering the incentive of a profit-sharing program and collective goal setting and teamwork

- Soliciting employee input through regular surveys of employee satisfaction

- Providing professional enrichment through providing tuition reimbursement and encouraging employees to pursue additional education and participate in industry organizations, skills workshops, and seminars

- Motivating through curiosity and creating an environment that stimulates employee interest to learn more

- Using cooperation and competition as a form of motivation based on individual preferences

Sometimes, inexperienced leaders will assume that the same factors that motivate one employee, or the leaders themselves, will motivate others too. Some will make the mistake of introducing de-motivating factors into the workplace, such as punishment for mistakes or frequent criticism, but negative reinforcement rarely works and often backfires.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

There are several positive psychology interventions that can be used in the workplace to improve important outcomes, such as reduced job stress and increased motivation, work engagement, and job performance. Numerous empirical studies have been conducted in recent years to verify the effects of these interventions.

Psychological capital interventions

Psychological capital interventions are associated with a variety of work outcomes that include improved job performance, engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Avey, 2014; Luthans & Youssef-Morgan 2017). Psychological capital refers to a psychological state that is malleable and open to development and consists of four major components:

- Self-efficacy and confidence in our ability to succeed at challenging work tasks

- Optimism and positive attributions about the future of our career or company

- Hope and redirecting paths to work goals in the face of obstacles

- Resilience in the workplace and bouncing back from adverse situations (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017)

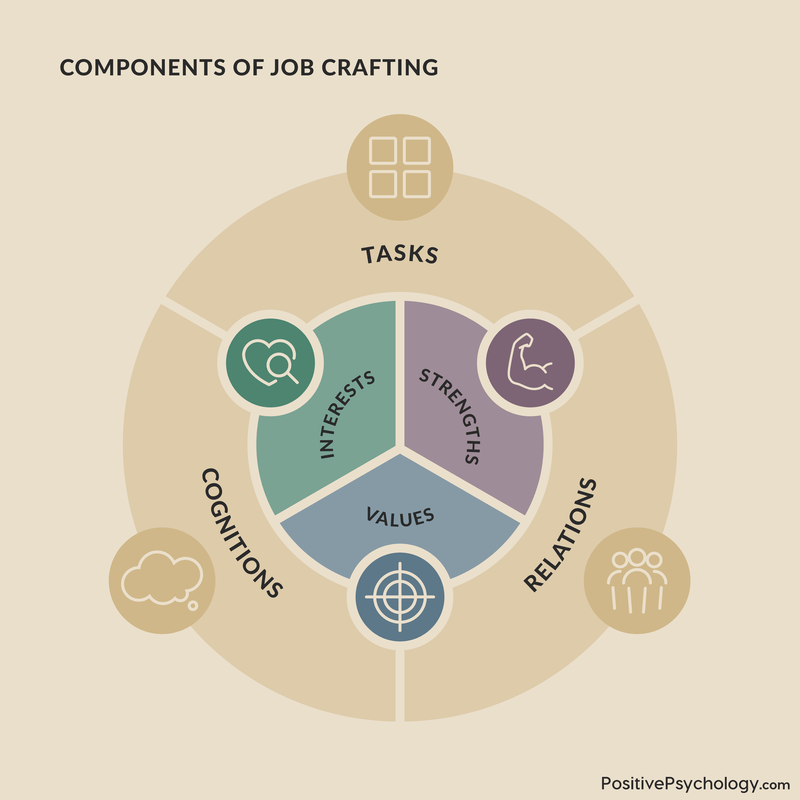

Job crafting interventions

Job crafting interventions – where employees design and have control over the characteristics of their work to create an optimal fit between work demands and their personal strengths – can lead to improved performance and greater work engagement (Bakker, Tims, & Derks, 2012; van Wingerden, Bakker, & Derks, 2016).

The concept of job crafting is rooted in the jobs demands–resources theory and suggests that employee motivation, engagement, and performance can be influenced by practices such as (Bakker et al., 2012):

- Attempts to alter social job resources, such as feedback and coaching

- Structural job resources, such as opportunities to develop at work

- Challenging job demands, such as reducing workload and creating new projects

Job crafting is a self-initiated, proactive process by which employees change elements of their jobs to optimize the fit between their job demands and personal needs, abilities, and strengths (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

Today’s motivation research shows that participation is likely to lead to several positive behaviors as long as managers encourage greater engagement, motivation, and productivity while recognizing the importance of rest and work recovery.

One key factor for increasing work engagement is psychological safety (Kahn, 1990). Psychological safety allows an employee or team member to engage in interpersonal risk taking and refers to being able to bring our authentic self to work without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career (Edmondson, 1999).

When employees perceive psychological safety, they are less likely to be distracted by negative emotions such as fear, which stems from worrying about controlling perceptions of managers and colleagues.

Dealing with fear also requires intense emotional regulation (Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, 2003), which takes away from the ability to fully immerse ourselves in our work tasks. The presence of psychological safety in the workplace decreases such distractions and allows employees to expend their energy toward being absorbed and attentive to work tasks.

Effective structural features, such as coaching leadership and context support, are some ways managers can initiate psychological safety in the workplace (Hackman, 1987). Leaders’ behavior can significantly influence how employees behave and lead to greater trust (Tyler & Lind, 1992).

Supportive, coaching-oriented, and non-defensive responses to employee concerns and questions can lead to heightened feelings of safety and ensure the presence of vital psychological capital.

Another essential factor for increasing work engagement and motivation is the balance between employees’ job demands and resources.

Job demands can stem from time pressures, physical demands, high priority, and shift work and are not necessarily detrimental. High job demands and high resources can both increase engagement, but it is important that employees perceive that they are in balance, with sufficient resources to deal with their work demands (Crawford, LePine, & Rich, 2010).

Challenging demands can be very motivating, energizing employees to achieve their goals and stimulating their personal growth. Still, they also require that employees be more attentive and absorbed and direct more energy toward their work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

Unfortunately, when employees perceive that they do not have enough control to tackle these challenging demands, the same high demands will be experienced as very depleting (Karasek, 1979).

This sense of perceived control can be increased with sufficient resources like managerial and peer support and, like the effects of psychological safety, can ensure that employees are not hindered by distraction that can limit their attention, absorption, and energy.

The job demands–resources occupational stress model suggests that job demands that force employees to be attentive and absorbed can be depleting if not coupled with adequate resources, and shows how sufficient resources allow employees to sustain a positive level of engagement that does not eventually lead to discouragement or burnout (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001).

And last but not least, another set of factors that are critical for increasing work engagement involves core self-evaluations and self-concept (Judge & Bono, 2001). Efficacy, self-esteem, locus of control, identity, and perceived social impact may be critical drivers of an individual’s psychological availability, as evident in the attention, absorption, and energy directed toward their work.

Self-esteem and efficacy are enhanced by increasing employees’ general confidence in their abilities, which in turn assists in making them feel secure about themselves and, therefore, more motivated and engaged in their work (Crawford et al., 2010).

Social impact, in particular, has become increasingly important in the growing tendency for employees to seek out meaningful work. One such example is the MBA Oath created by 25 graduating Harvard business students pledging to lead professional careers marked with integrity and ethics:

The MBA oath

“As a business leader, I recognize my role in society.

My purpose is to lead people and manage resources to create value that no single individual can create alone.

My decisions affect the well-being of individuals inside and outside my enterprise, today and tomorrow. Therefore, I promise that:

- I will manage my enterprise with loyalty and care, and will not advance my personal interests at the expense of my enterprise or society.

- I will understand and uphold, in letter and spirit, the laws and contracts governing my conduct and that of my enterprise.

- I will refrain from corruption, unfair competition, or business practices harmful to society.

- I will protect the human rights and dignity of all people affected by my enterprise, and I will oppose discrimination and exploitation.

- I will protect the right of future generations to advance their standard of living and enjoy a healthy planet.

- I will report the performance and risks of my enterprise accurately and honestly.

- I will invest in developing myself and others, helping the management profession continue to advance and create sustainable and inclusive prosperity.

In exercising my professional duties according to these principles, I recognize that my behavior must set an example of integrity, eliciting trust, and esteem from those I serve. I will remain accountable to my peers and to society for my actions and for upholding these standards. This oath, I make freely, and upon my honor.”

Job crafting is the process of personalizing work to better align with one’s strengths, values, and interests (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Any job, at any level can be ‘crafted,’ and a well-crafted job offers more autonomy, deeper engagement and improved overall wellbeing.

There are three types of job crafting:

- Task crafting involves adding or removing tasks, spending more or less time on certain tasks, or redesigning tasks so that they better align with your core strengths (Berg et al., 2013).

- Relational crafting includes building, reframing, and adapting relationships to foster meaningfulness (Berg et al., 2013).

- Cognitive crafting defines how we think about our jobs, including how we perceive tasks and the meaning behind them.

If you would like to guide others through their own unique job crafting journey, our set of Job Crafting Manuals (PDF) offer a ready-made 7-session coaching trajectory.

Prosocial motivation is an important driver behind many individual and collective accomplishments at work.

It is a strong predictor of persistence, performance, and productivity when accompanied by intrinsic motivation. Prosocial motivation was also indicative of more affiliative citizenship behaviors when it was accompanied by motivation toward impression management motivation and was a stronger predictor of job performance when managers were perceived as trustworthy (Ciulla, 2000).

On a day-to-day basis most jobs can’t fill the tall order of making the world better, but particular incidents at work have meaning because you make a valuable contribution or you are able to genuinely help someone in need.

J. B. Ciulla

Prosocial motivation was shown to enhance the creativity of intrinsically motivated employees, the performance of employees with high core self-evaluations, and the performance evaluations of proactive employees. The psychological mechanisms that enable this are the importance placed on task significance, encouraging perspective taking, and fostering social emotions of anticipated guilt and gratitude (Ciulla, 2000).

Some argue that organizations whose products and services contribute to positive human growth are examples of what constitutes good business (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004). Businesses with a soul are those enterprises where employees experience deep engagement and develop greater complexity.

In these unique environments, employees are provided opportunities to do what they do best. In return, their organizations reap the benefits of higher productivity and lower turnover, as well as greater profit, customer satisfaction, and workplace safety. Most importantly, however, the level of engagement, involvement, or degree to which employees are positively stretched contributes to the experience of wellbeing at work (Csíkszentmihályi, 2004).

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Daniel Pink (2011) argues that when it comes to motivation, management is the problem, not the solution, as it represents antiquated notions of what motivates people. He claims that even the most sophisticated forms of empowering employees and providing flexibility are no more than civilized forms of control.

He gives an example of companies that fall under the umbrella of what is known as results-only work environments (ROWEs), which allow all their employees to work whenever and wherever they want as long their work gets done.

Valuing results rather than face time can change the cultural definition of a successful worker by challenging the notion that long hours and constant availability signal commitment (Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011).

Studies show that ROWEs can increase employees’ control over their work schedule; improve work–life fit; positively affect employees’ sleep duration, energy levels, self-reported health, and exercise; and decrease tobacco and alcohol use (Moen, Kelly, & Lam, 2013; Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang, 2011).

Perhaps this type of solution sounds overly ambitious, and many traditional working environments are not ready for such drastic changes. Nevertheless, it is hard to ignore the quickly amassing evidence that work environments that offer autonomy, opportunities for growth, and pursuit of meaning are good for our health, our souls, and our society.

Leave us your thoughts on this topic.

Related reading: Motivation in Education: What It Takes to Motivate Our Kids

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Anderson, D. (2018, February 22). 11 Surprising statistics about employee recognition [infographic]. Best Practice in Human Resources. Retrieved from https://www.bestpracticeinhr.com/11-surprising-statistics-about-employee-recognition-infographic/

- Avey, J. B. (2014). The left side of psychological capital: New evidence on the antecedents of PsyCap. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21( 2), 141–149.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (vol. 3). John Wiley and Sons.

- Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations , 65 (10), 1359–1378

- Barsade, S. G., Brief, A. P., & Spataro, S. E. (2003). The affective revolution in organizational behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 3–52). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81-104) . American Psychological Association.

- Ciulla, J. B. (2000). The working life: The promise and betrayal of modern work. Three Rivers Press.

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology , 95 (5), 834–848.

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2004). Good business: Leadership, flow, and the making of meaning. Penguin Books.

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology , 863) , 499–512.

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly , 44 (2), 350–383.

- Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and take: A revolutionary approach to success. Penguin.

- Hackman, J. R. (1987). The design of work teams. In J. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 315–342). Prentice-Hall.

- Herzberg, F. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley.

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits – self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology , 86 (1), 80–92.

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal , 33 (4), 692–724.

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (2), 285–308.

- Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: Schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review , 76 (2), 265–290.

- Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne revisited: Management and the worker, its critics, and developments in human relations in industry. Cornell University.

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4 , 339-366.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E. L., & Lam, J. (2013). Healthy work revisited: Do changes in time strain predict well-being? Journal of occupational health psychology, 18 (2), 157.

- Moen, P., Kelly, E., Tranby, E., & Huang, Q. (2011). Changing work, changing health: Can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(4), 404–429.

- Pattison, K. (2010, August 26). Chip Conley took the Maslow pyramid, made it an employee pyramid and saved his company. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/1685009/chip-conley-took-maslow-pyramid-made-it-employee-pyramid-and-saved-his-company

- Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Penguin.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2) , 1-9.

- Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 25) (pp. 115–191). Academic Press.

- von Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2016). A test of a job demands–resources intervention. Journal of Managerial Psychology , 31 (3), 686–701.

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26 (2), 179–201.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Good and helpful study thank you. It will help achieving goals for my clients. Thank you for this information

A lot of data is really given. Validation is correct. The next step is the exchange of knowledge in order to create an optimal model of motivation.

A good article, thank you for sharing. The views and work by the likes of Daniel Pink, Dan Ariely, Barry Schwartz etc have really got me questioning and reflecting on my own views on workplace motivation. There are far too many organisations and leaders who continue to rely on hedonic principles for motivation (until recently, myself included!!). An excellent book which shares these modern views is ‘Primed to Perform’ by Doshi and McGregor (2015). Based on the earlier work of Deci and Ryan’s self determination theory the book explores the principle of ‘why people work, determines how well they work’. A easy to read and enjoyable book that offers a very practical way of applying in the workplace.

Thanks for mentioning that. Sounds like a good read.

All the best, Annelé

Motivation – a piece of art every manager should obtain and remember by heart and continue to embrace.

Exceptionally good write-up on the subject applicable for personal and professional betterment. Simplified theorem appeals to think and learn at least one thing that means an inspiration to the reader. I appreciate your efforts through this contributive work.

Excelente artículo sobre motivación. Me inspira. Gracias

Very helpful for everyone studying motivation right now! It’s brilliant the way it’s witten and also brought to the reader. Thank you.

Such a brilliant piece! A super coverage of existing theories clearly written. It serves as an excellent overview (or reminder for those of us who once knew the older stuff by heart!) Thank you!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

How to Assess and Improve Readiness for Change

Clients seeking professional help from a counselor or therapist are often aware they need to change yet may not be ready to begin their journey. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Section 6: Motivation in the Workplace

The impacts of motivation in the workplace

So far in this chapter, we’ve discussed the components of motivation and some of the most well-known and useful motivational theories. There are more theories out there, and we could go on for quite a while describing them. However, it’s important for managers to understand that all of them seek to predict human behavior and understand the mystery that is motivation, and that all of them bring some amount of clarity to the issue.

Now it’s time to dig into how motivation impacts the workplace.

Learning Outcomes

- Analyze managerial responses to motivation theories

- Discuss the impact of cultural differences on motivation

Managerial Responses to Motivation

Now that we understand a bit more about what motivation is and the theories behind its origins and development, we can put them to work in a managerial setting. Let’s take a look at some managerial responses to motivation.

Management by Objectives

We talked a bit about management by objectives (MBO) when we discussed goal setting as a part of the work component of motivation. Management by Objective is a response to the goal-setting theory as a motivator.

The goal-setting theory has an impressive base of research support, and MBO makes it operational. As a reminder, MBO sets individual goals for employees based on department goals, which are based on company goals. It looks like this:

MBO advocates specific, measurable goals and feedback. There is only implication, though, that goals are perceived as attainable. The approach is most effective when the individual has to stretch to meet the goals set.

MBO can be a participative process. When individuals are consulted in the creation of their own goals, it often results in workers setting a goal that stretch them further. MBO does not require that the individual worker participate, though. The process seems to be about as effective when goals are assigned by a manager to the individual.

MBO is a widely used and successful practice for many industries. Failures occur when unrealistic expectations come into play, or cultural incompatibilities thwart the process.

Employee Recognition Programs

Employee recognition programs cover a wide variety of activities, ranging from private “thank yous” to publicized recognition ceremonies. It strengthens the link between performance and outcome of the expectancy framework. Recognition continues to be cited on surveys as one of the most powerful motivators for an employee.

Types of recognition might include:

- A personal thank you to an employee from a manager, verbally or in a note

- A public recognition of an employee, in a company communication or ceremony

- A team thank you via a lunch bought by the manager

- A program where customers recognize great service by front line workers

In an environment where there are layoffs and increased workloads all across the country, recognition programs go a long way toward motivating employees and provide a relatively low-cost way to boost performance.

Employee Involvement Programs

Here are a few types of employee involvement:

- Employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs). A fairly popular employee involvement program, where an ESOP trust is created, and the organization will contribute stock or cash to buy stock for the trust. The stock is then allocated to employees. Research suggests that ESOPs increase satisfaction but their impact on performance remains unclear, as companies offering this option often perform similarly to companies that don’t.

- Participative management. This is a program where subordinates share a significant responsibility for decision making with their managers. As jobs become more complex, managers aren’t always aware of everything that employees do, and studies have found that this process increases the commitment to decisions. Research shows that this approach has a modest influence productivity, motivation, and job satisfaction.

- Representative participation. This is an approach where workers are represented by a small group of employees who participate in organizational decisions. Representative participation is mean to put labor on more equal terms with management and stockholders where company decisions are concerned. The overall influence on working employees seems to be minimal, and the value of it appears to be more symbolic than motivating.

Looking at these employment involvement programs through the Theory X & Theory Y lens, the approach certainly leans more toward the Theory Y approach of people management. These programs can also satisfy an employee’s needs for responsibility, achievement, etc., and thus fit well with the ERG theory as well. They can be part of a good balance of motivational offerings.

Job Redesign Programs

Clever redesign of jobs to accommodate employees’ needs for additional flexibility can serve to motivate them. Managers looking to reshape jobs in order to make them more motivating might look toward a few redesign and scheduling options.

- Job rotation. Employees who have very repetitive jobs can find new motivation in a job rotation program. An assembly line might employ this technique, where a worker might be focused on constructing a portion of an exhaust system for a period of time, and the move over to an area that is devoted to putting together transmissions. This approach navigates the pitfalls of boredom, but it can increase training costs and temporarily reduce productivity as people ramp up with their new responsibilities.

- Job enrichment. This refers to the vertical expansion of one’s job to include additional responsibilities that allow employees to control planning, execution, and evaluation aspects of their work. Employees can see a task through from start to finish in many cases, allowing for a holistic view of the task and ownership of the outcome. For instance, a group that formerly only handled the development of art for marketing materials might be retrained to meet with clients, get a better understanding of their needs, and then work with a printer to produce the final product. This process generally yields a reduction in turnover and an increase in job satisfaction for employees, but evidence of increased productivity is often inconclusive.

- Flexible Hours. Flexible hours allow employees a degree of autonomy when it comes to the hours of their workday. Morning people can be up-and-at-‘em at 6AM, and night owls can show up later and work later. Flexible hours often reduce absenteeism, increase productivity, and reduce overtime expenses. However, this approach is not applicable to every job.

- Job Sharing. This program allows for two or more individuals to share a 40-hour workweek. Job sharing allows an organization to draw on the talents of more than one person to complete a job and allows them to avoid layoffs due to overstaffing. Conversely, a manager has to find compatible pairs of employees, which is not always such an easy task.

- Telecommuting. When an individual can work from home, he or she can have more flexible hours, less downtime in a car, the ability to wear whatever he or she wants, and fewer interruptions. Organizations that employ telecommuting can realize higher productivity, enjoy a larger labor pool from which to select employees, and experience less office space costs. But telecommuters can’t experience the benefits of an office situation, and managers can tend to undervalue the contributions of workers they don’t see regularly.

Job redesign and scheduling can be linked to several motivational theories. Herzberg’s two-factor theory supports the idea of job enrichment in its proposal that increasing intrinsic factors of a job will increase an employee’s satisfaction with a job. Flexibility is an important link in linking rewards to personal goals in the expectancy theory.

Variable Pay Programs

Variable-pay programs increase motivation and productivity, as organizations with these plans are shown to have higher levels of profitability than those who don’t. Variable-pay is most compatible with the expectancy theory predictions that employees should perceive a strong relationship between their performance and the rewards they receive.

These programs help managers address differences in individual needs and allow employees to participate in decisions that affect them. Combining some of these tactics with MBO so that employees understand what’s expected of them, linking performance and rewards through recognition and making sure the system is equitable can help make a manager’s organization productive.

Practice Question

Motivation in different cultures.

A warning for managers everywhere—motivation theories are culture-bound.

For instance, Maslow’s theory, which suggests that humans follow a needs path from physiological needs to needs of safety, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization, is a typically American point of view. Greece and Mexico, countries with cultures that look for a significant set of rules and guidelines in their lives, might have safety at the top of their pyramids, while Scandinavian countries, well known for their nurturing characteristics, might have social needs at the top of theirs. If these differences are well understood, managers can adapt accordingly, and understand that group work is more important for their Scandinavian workers, and so on.

What other theories fall short when you stand them up against other cultures? Well, the need to achieve and a concern for performance is found in the US, UK and Canada, but in countries like Chile and Portugal, it’s almost non-existent. The equity theory, which we talked about in the first section of this module, is embraced in the US, but in the former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, workers expect their rewards to reflect their personal needs as well as their performance. It stands to reason that US pay practices might be perceived as unfair in these countries.

Geert Hofstede, a Dutch social psychologist, professor at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and a former IBM employee, conducted some pioneering research on cross-cultural groups in organizations, which led to his cultural dimensions theory.

In this theory, Hofstede defines culture as the unique way in which people are collectively taught in their environments. He looks to compare and understand the collective mindset of these groups of people and how they differ. His conclusions were that cultural differences showed themselves in six significant buckets. Hofstede created an “index” for each category to show where individual cultures fell along the spectrum:

- Power Distance: this is an index that describes the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. A higher index number suggests that hierarchy is clearly established and executed in society, while a lower index would indicate that people question authority in that culture. (Latin, Asian, and Arab countries score on the high side, while Anglo and Germanic countries score low. The US is in the middle.)

- Individualism: this measures the degree to which people in a society are integrated into groups. The United States scores very high in this category.

- Uncertainty avoidance: this is defined as a “society’s tolerance for ambiguity.” Cultures scoring high in this area opt for very defined codes of behavior and laws, while cultures scoring lower are more accepting of different thoughts and ideas. Belgium and Germany score high while countries like Sweden and Denmark score lower.

- Masculinity vs femininity: in more masculine societies, women and men are more competitive, while in feminine societies, they share caring views equally with men. Anglo countries like the UK and the US tend to lean toward masculinity in their cultures, while Scandinavian countries tend toward femininity.

- Long-term Orientation vs. Short-term Orientation: this measures the degree to which a society honors tradition. A lower score indicates traditions are kept, while a higher score indicates the society views adaptation and problem-solving as a necessary component of their culture. Asian cultures have strong long-term orientation, while Anglo countries, Africa and Latin America have shorter-term orientation.

- Indulgence vs. restraint: this is a measurement of happiness if simple joys are fulfilled. Indulgent societies believe themselves to be in control of their lives, while restrained societies believe that external forces dictate their lives. There is less data about this particular dimension, but we do know that Latin America, the Anglo countries and Nordic Europe score high on indulgence, while Muslim countries and East Asia tend to score high on restraint.

The Hofstede Insight website takes the guesswork out of comparing countries’ cultures and can help you understand the collective viewpoint of their people as they relate to these six indices.

When you compare Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as we briefly did above, you can see where cultural differences shift the order of needs on the pyramid. We mentioned above that Belgium and Germany score high on the uncertainty avoidance dimension—they don’t like social ambiguity, they want to be able to control their futures and feel threatened by the unknown. So it would make sense that, while “safety” is the second rung of the pyramid here in the United States, it’s a more significant need to satisfy in German culture.

Hofstede’s cultural dimension highlight the importance cultures place on different needs. These dimensions can be used to determine differences in individual needs based on their cultural teachings and beliefs.

Now that we’ve discussed this in some detail, it’s important to understand that not all motivational drivers are culture-bound. For example, the desire for interesting work appears to be important to all workers everywhere. Growth, achievement, and responsibility were also highly rated across various cultures. The manager of an international team doesn’t have to approach everything differently. But keeping in mind that cultural differences drive individuals’ needs will help a manager create motivating circumstances for all his workers.

CC licensed content, Original

- What is Motivation?. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Images: The Expectancy Framework. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- Untitled. Authored by: Julio Pascoal Palestrante. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/photos/male-business-elegant-executives-3163392/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Pixabay License

6.4 Motivation in the Workplace Copyright © 2019 by Graduate Studies is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: Theories of Motivation

Chapter Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to know and learn the following:

- Understand the role of motivation in determining employee performance.

- Classify the basic needs of employees.

- Describe how fairness perceptions are determined and consequences of these perceptions.

- Understand the importance of rewards and punishments.

- Apply motivation theories to analyze performance problems.

Introduction

The challenges and motivators in a post pandemic world..

The world is becoming progressively more digital with every passing year, so today’s workforce looks a lot different than it did 25 years ago. This progression, expedited by the global pandemic of Covid19, presents new challenges that today’s employers must learn to navigate to motivate their teams, prevent employee burnout and minimize turnover.

To understand and overcome the challenges in motivating today’s workforce, especially companies with significant numbers of non-desk workers, we must understand both the challenges and the motivators of new age, digital employees.

Let’s start with the challenges.

The top challenges chosen by the vast majority of employers

A. Building a great employee experience

1.Listen to people. Ensure that employees have a means of communication. Many non-desk workers are not connected to the company in a way that allows two-way communication.

2.Get feedback from surveys and focus groups, then implement change if need be. Keep an open channel of communication so that employees feel connected. Be committed to employee development and growth.

3.Equip and enable managers to support their teams. Creating a positive employee experience goes a long way with employee engagement and motivation.

B. Creating calm and reassurance in periods of turbulence

1.We can all agree that the world has been in a period of turbulence over the past two years. As a leader in an organization, you must pause and breathe . Managers can unintentionally pass their stress onto other employees.

2.Do the research and prevent the spread of misinformation. Speak clearly and confidently to your teams and colleagues so that you appear to have control over the situation. Transparency will create trust and go a long way in calming the workforce.

C. Fighting burnout

1.Let’s talk about the ever-elusive fight against burnout. It’s easy to understand that the outside stressors of everyday life during and after a pandemic paired with the daily stressors of work are enough to burn anyone out. More than 70% of employees reported feeling burnt out over the past year, making history (Forbes.com).

2.It’s never been more critical than it is now to tackle feelings of physical and emotional exhaustion. The key to avoiding burnout is getting in front of it, as it is much easier to prevent burnout than reverse it.

D. Turnover and letting employees go

1.Turnover tends to be a result of a poor approach to the above challenges. It’s no secret that the cost of turnover is high, estimated at 1.5 – 2 times an employee’s salary and $1,500 per hourly employee (builtin.com).

Therefore, organizations should actively avoid turnover by putting into place best practices and implementing a solid plan to tackle the above challenges.

E. Retaining top talent

1.With the cost of turnover being so high, retaining top talent is a priority . The key here is employee engagement, so ask questions to gain insight on employees to instill the correct development and training programs.

Weekly one-on-one meetings with department heads or managers are an excellent way to ask questions and get to know these individuals. Including all employees in the communication loop creates an atmosphere of teamwork and ensures that everyone’s efforts are appreciated.

2.Create on-the-job learning opportunities, whether significant or small. Vary learning experiences and provide insightful feedback that is constructive and accompanied by manageable action steps.

F. Communicating effectively

These challenges arguably have a common denominator – they’re a causal effect of poor communication. Therefore, effective communication could essentially eliminate or solve these challenges.

It seems simple, yet effective communication is complex and involves complex solutions. Everyone communicates differently. The good news is there are a plethora of companies specializing in making communications in the workforce easy.

According to Pew Research, 91% of Americans between the ages of 18 and 64 own a smartphone, making them far and away the most popular way to communicate. Due to this information, the most innovative and easiest way to reach employees and increase engagement would be to interact via the smartphone.

Employee engagement apps can simplify your workforce management system and workplace communication making it accessible for all employees, non-desk workers, remote and office workers alike. Some of these platforms include Artificial Intelligence which provides highly structured communications.

These communications give the right message to the right person at the right time, prevent spray and pray messaging, and the chaos and lack of usage that reply-all messaging creates.

Now that the challenges have been addressed, let’s understand the motivators.

Why is it that, on some days, it can feel harder than others to get up when your alarm goes off, do your workout, complete a work or school assignment, or make dinner for your family?

Motivation (or a lack thereof) is usually behind why we do the things that we do.

There are different types of motivation, and as it turns out, understanding why you are motivated to do the things that you do can help you keep yourself motivated — and can help you motivate others.

There are two types of motivator categories in a company’s culture, intrinsic and extrinsic.

What Is Intrinsic Motivation?

When you’re intrinsically motivated, your behavior is motivated by your internal desire to do something for its own sake — for example, your personal enjoyment of an activity, or your desire to learn a skill because you’re eager to learn.

Examples of intrinsic motivation could include:

- Reading a book because you enjoy the storytelling

- Exercising because you want to relieve stress

- Cleaning your home because it helps you feel organized

What Is Extrinsic Motivation?

When you’re extrinsically motivated, your behavior is motivated by an external factor pushing you to do something in hopes of earning a reward — or avoiding a less-than-positive outcome.

Examples of extrinsic motivation could include:

- Reading a book to prepare for a test

- Exercising to lose weight

- Cleaning your home to prepare for visitors coming over

If you have a job, and you must complete a project, you’re probably extrinsically motivated — by your manager’s praise or a potential raise or commission — even if you enjoy the project while you’re doing it. If you’re in school, you’re extrinsically motivated to learn a foreign language because you’re being graded on it — even if you enjoy practicing and studying it.

So, intrinsic motivation is good, and extrinsic motivation is good. The key is to figure out why you — and your team — are motivated to do things and encouraging both types of motivation.

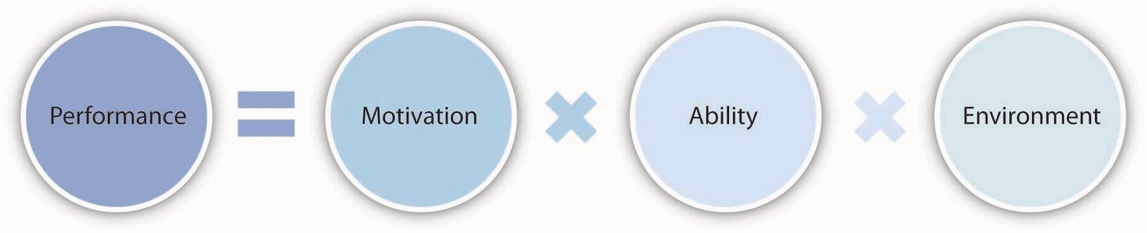

If someone is not performing well, what could be the reason? According to this equation, motivation, ability, and environment are the major influences over employee performance.

Motivation is one of the forces that lead to performance. Motivation is defined as the desire to achieve a goal or a certain performance level, leading to goal-directed behaviour. When we refer to someone as being motivated, we mean that the person is trying hard to accomplish a certain task. Motivation is clearly important if someone is to perform well; however, it is not sufficient. Ability —or having the skills and knowledge required to perform the job—is also important and is sometimes the key predictor of effectiveness. Finally, environmental factors such as having the resources, information, and support to perform well are critical to determine performance. At different times, one of these three factors may be the key to high performance. For example, for an employee sweeping the floor, motivation may be the most important factor that determines performance. In contrast, even the most motivated individual would not be able to successfully design a house without the necessary talent involved in building quality homes. Being motivated is not the same as being a high performer and is not the sole reason why people perform well, but it is nevertheless a key influence over our performance level.

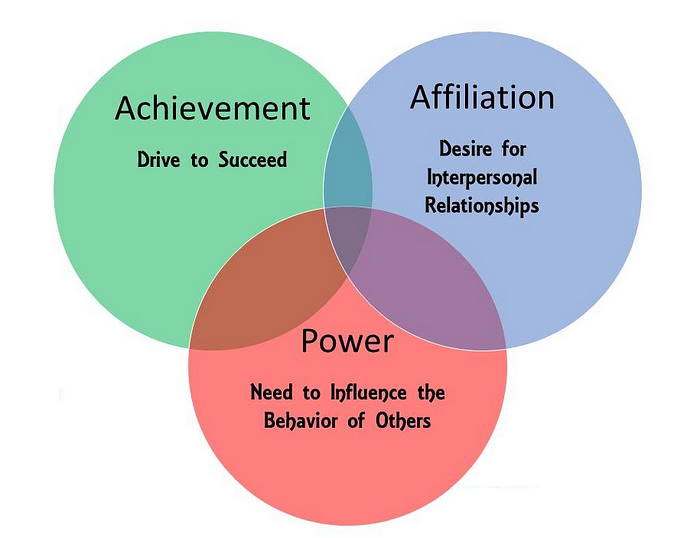

So, what motivates people? Why do some employees try to reach their targets and pursue excellence while others merely show up at work and count the hours? As with many questions involving human beings, the answer is anything but simple. Instead, there are several theories explaining the concept of motivation. We will discuss motivation theories under two categories: need-based theories and process theories.

5.1 A Motivating Place to Work: The Case of Rogers Communications Inc

Rogers Communications Inc has been identified as one of Canada’s 100 top employers by Media Corp Canada, who investigate Canadian companies based on 8 criteria: (1) Physical Workplace; (2) Work Atmosphere & Social; (3) Health, Financial & Family Benefits; (4) Vacation & Time Off; (5) Employee Communications; (6) Performance Management; (7) Training & Skills Development; and (8) Community Involvement. Employers are compared to other organizations in their field to determine which offers the most progressive and forward-thinking programs (Media Corp Canada,2019).

5.2 Need-Based Theories of Motivation