What is PBL?

Project Based Learning (PBL) is a teaching method in which students learn by actively engaging in real-world and personally meaningful projects.

In Project Based Learning, teachers make learning come alive for students.

Students work on a project over an extended period of time – from a week up to a semester – that engages them in solving a real-world problem or answering a complex question. They demonstrate their knowledge and skills by creating a public product or presentation for a real audience.

As a result, students develop deep content knowledge as well as critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication skills. Project Based Learning unleashes a contagious, creative energy among students and teachers.

And in case you were looking for a more formal definition...

Project Based Learning is a teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem, or challenge.

Watch Project Based Learning in Action

These 7-10 minute videos show the Gold Standard PBL model in action, capturing the nuts and bolts of a PBL unit from beginning to end.

VIDEO: The Water Quality Project

VIDEO: March Through Nashville

VIDEO: The Tiny House Project

How does pbl differ from “doing a project”.

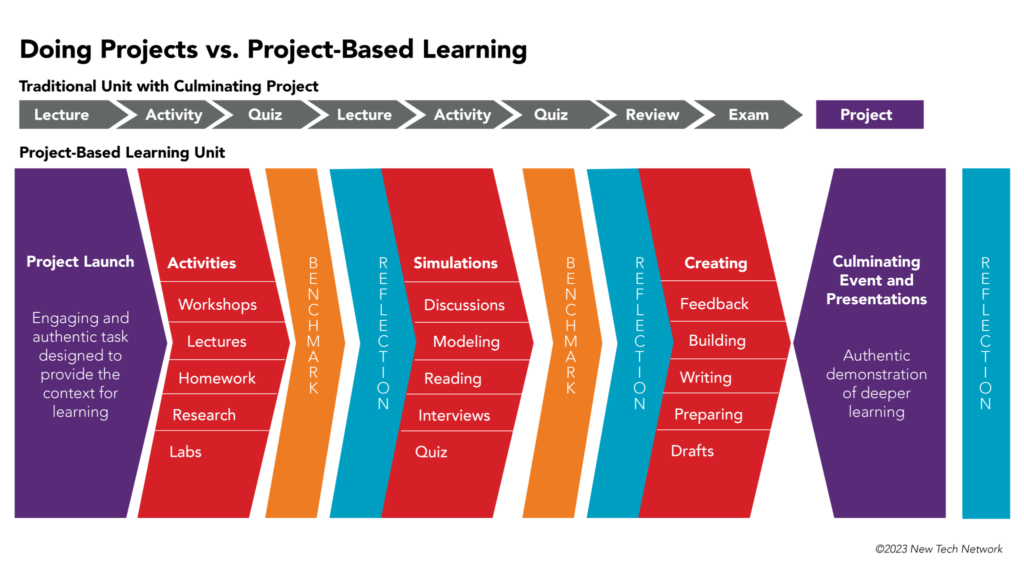

PBL is becoming widely used in schools and other educational settings, with different varieties being practiced. However, there are key characteristics that differentiate "doing a project" from engaging in rigorous Project Based Learning.

We find it helpful to distinguish a "dessert project" - a short, intellectually-light project served up after the teacher covers the content of a unit in the usual way - from a "main course" project, in which the project is the unit. In Project Based Learning, the project is the vehicle for teaching the important knowledge and skills student need to learn. The project contains and frames curriculum and instruction.

In contrast to dessert projects, PBL requires critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and various forms of communication. To answer a driving question and create high-quality work, students need to do much more than remember information. They need to use higher-order thinking skills and learn to work as a team.

Learn more about "dessert" projects vs PBL

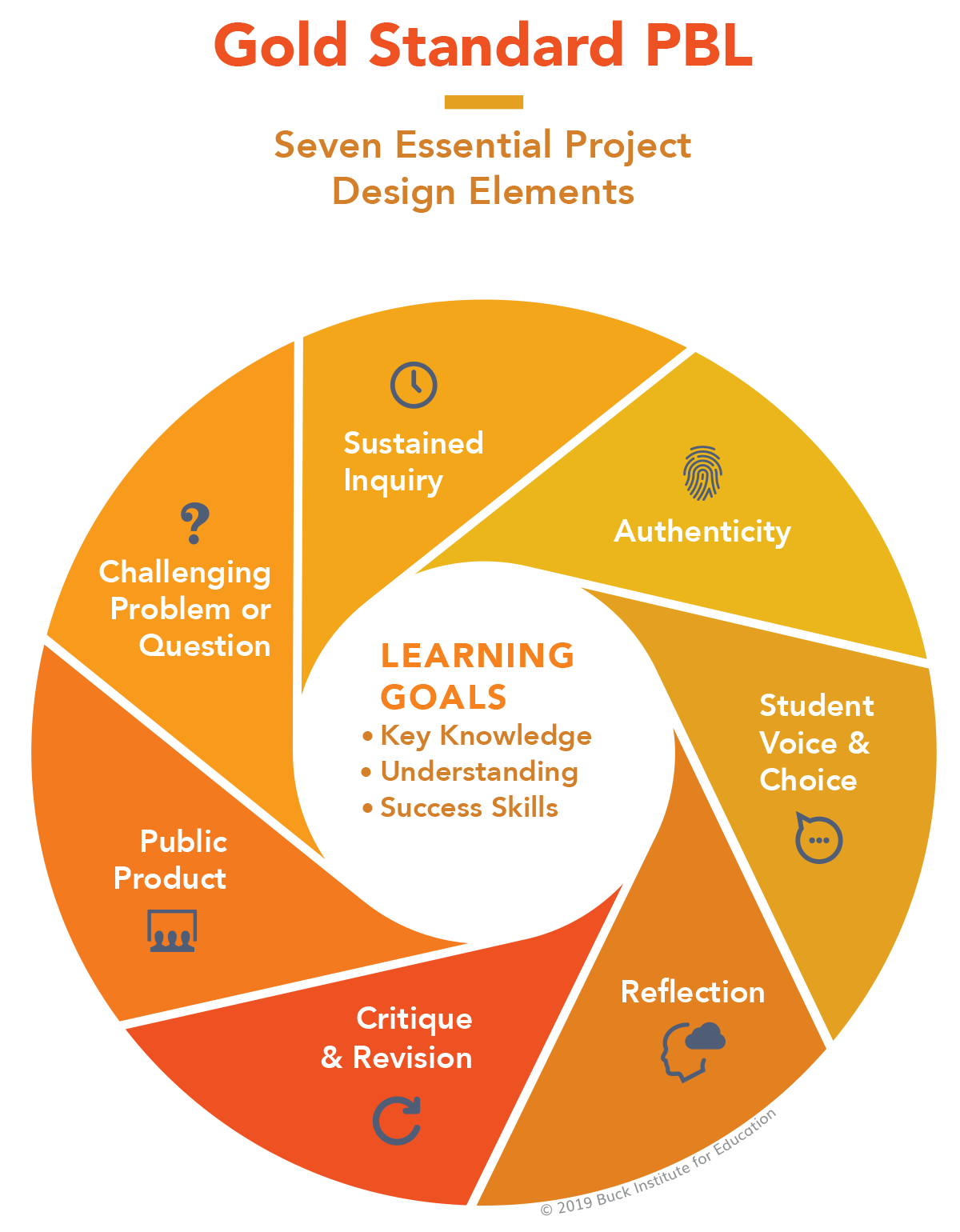

The gold standard for high-quality PBL

To help ensure your students are getting the main course and are engaging in quality Project Based Learning, PBLWorks promotes a research-informed model for “Gold Standard PBL.”

The Gold Standard PBL model encompasses two useful guides for educators:

1) Seven Essential Project Design Elements provide a framework for developing high quality projects for your classroom, and

2) Seven Project Based Teaching Practices help teachers, schools, and organizations improve, calibrate, and assess their practice.

The Gold Standard PBL model aligns with the High Quality PBL Framework . This framework describes what students should be doing, learning, and experiencing in a good project. Learn more at HQPBL.org .

Yes, we provide PBL training for educators! PBLWorks offers a variety of workshops, courses and services for teachers, school and district leaders, and instructional coaches to get started and advance their practice with Project Based Learning. Learn more

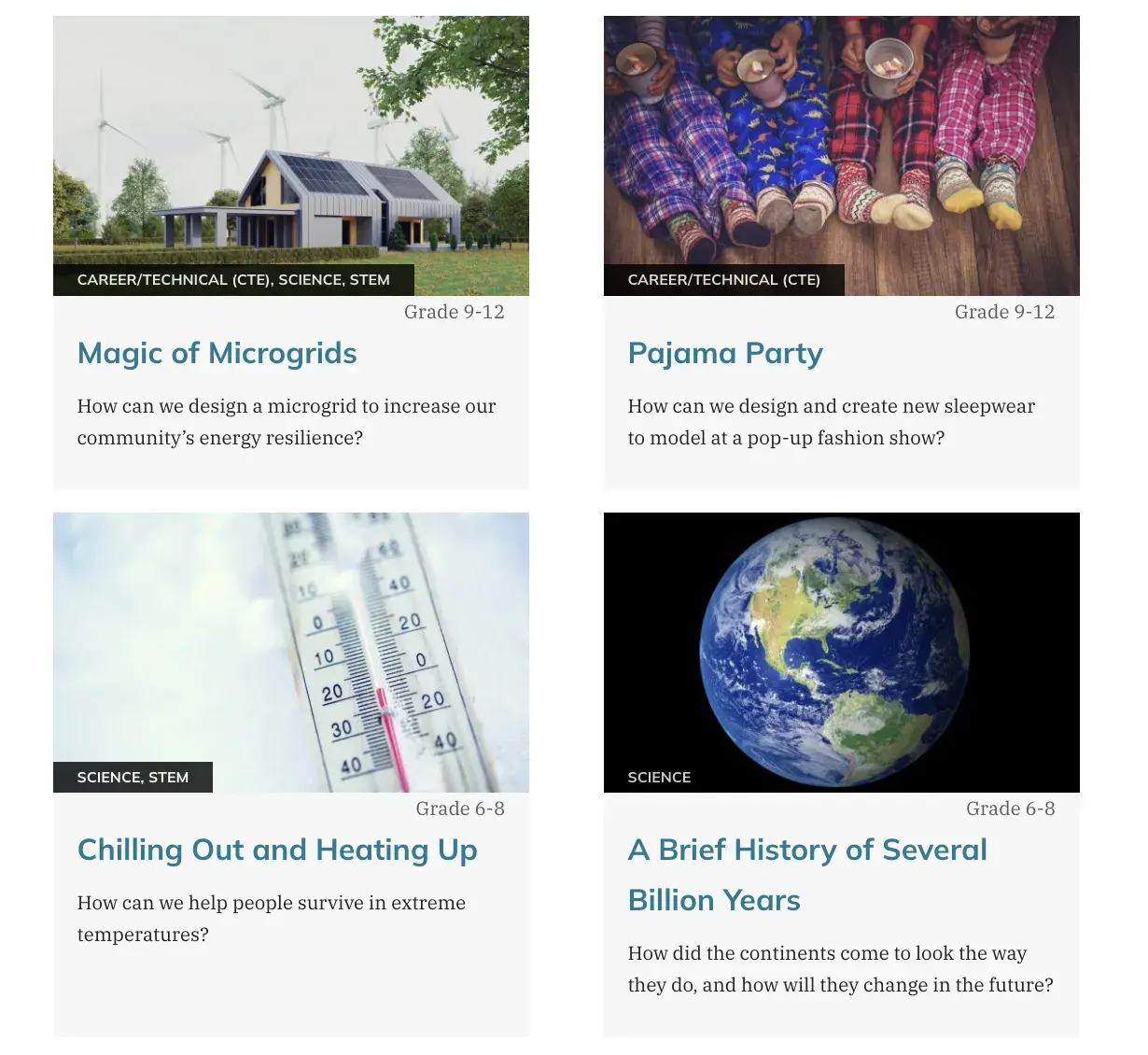

See Sample Projects

Explore our expanding library of project ideas, with over 80 projects that are standards-aligned, and cover a range of grade levels and subject areas.

Don't miss a thing! Get PBL resources, tips and news delivered to your inbox.

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning refers to any programmatic or instructional approach that utilizes multifaceted projects as a central organizing strategy for educating students. When engaged in project-based learning, students will typically be assigned a project or series of projects that require them to use diverse skills—such as researching, writing, interviewing, collaborating, or public speaking—to produce various work products, such as research papers, scientific studies, public-policy proposals, multimedia presentations, video documentaries, art installations, or musical and theatrical performances, for example. Unlike many tests, homework assignments, and other more traditional forms of academic coursework, the execution and completion of a project may take several weeks or months, or it may even unfold over the course of a semester or year.

Closely related to the concept of authentic learning , project-based-learning experiences are often designed to address real-world problems and issues, which requires students to investigate and analyze their complexities, interconnections, and ambiguities (i.e., there may be no “right” or “wrong” answers in a project-based-learning assignment). For this reason, project-based learning may be called inquiry-based learning or learning by doing , since the learning process is integral to the knowledge and skills students acquire. Students also typically learn about topics or produce work that integrates multiple academic subjects and skill areas. For example, students may be assigned to complete a project on a local natural ecosystem and produce work that investigates its history, species diversity, and social, economic, and environmental implications for the community. In this case, even if the project is assigned in a science course, students may be required to read and write extensively (English); research local history using texts, news stories, archival photos, and public records (history and social studies); conduct and record first-hand scientific observations, including the analysis and tabulation of data (science and math); and develop a public-policy proposal for the conservation of the ecosystem (civics and government) that will be presented to the city council utilizing multimedia technologies and software applications (technology).

In project-based learning, students are usually given a general question to answer, a concrete problem to solve, or an in-depth issue to explore. Teachers may then encourage students to choose specific topics that interest or inspire them, such as projects related to their personal interests or career aspirations. For example, a typical project may begin with an open-ended question (often called an “essential question” by educators): How is the principle of buoyancy important in the design and construction of a boat? What type of public-service announcement will be most effective in encouraging our community to conserve water? How can our school serve healthier school lunches? In these cases, students may be given the opportunity to address the question by proposing a project that reflects their interests. For example, a student interested in farming may explore the creation of a school garden that produces food and doubles as a learning opportunity for students, while another student may choose to research health concerns related to specific food items served in the cafeteria, and then create posters or a video to raise awareness among students and staff in the school.

In public schools, the projects, including the work products created by students and the assessments they complete, will be based on the same state learning standards that apply to other methods of instruction—i.e., the projects will be specifically designed to ensure that students meet expected learning standards. While students work on a project, teachers typically assess student learning progress—including the achievement of specific learning standards—using a variety of methods, such as portfolios , demonstrations of learning , or rubrics , for example. While the learning process may be more student-directed than some traditional learning experiences, such as lectures or quizzes, teachers still provide ongoing instruction, guidance, and academic support to students. In many cases, adult mentors, advisers, or experts from the local community—such as scientists, elected officials, or business leaders—may be involved in the design of project-based experiences, mentor students throughout the process, or participate on panels that review and evaluate the final projects in collaboration with teachers.

As a reform strategy, project-based learning may become an object of debate both within a school or in the larger community. Schools that decide to adopt project-based learning as their primary method of instruction, as opposed to schools that are founded on the philosophy and use the method from their inception, are more likely to encounter criticism or resistance. The instructional nuances of project-based learning can also become a source of confusion and misunderstanding, given that the approach represents a fairly significant departure from more familiar conceptions of schooling.

In addition, there may be debate among educators about what specifically does and doesn’t constitute “project-based learning.” For example, some teachers may already be doing “projects” in their courses, and they might consider these activities to be a form of project-based learning, but others may dispute such claims because the projects do not conform to their more specific and demanding definition—i.e., they are not “authentic” forms of project-based learning since they don’t meet the requisite instructional criteria (such as the features described above).

The following are a few representative examples of the kinds of arguments typically made by advocates of project-based learning:

- Project-based learning gives students a more “integrated” understanding of the concepts and knowledge they learn, while also equipping them with practical skills they can apply throughout their lives. The interdisciplinary nature of project-based learning helps students make connections across different subjects, rather than perceiving, for example, math and science as discrete subjects with little in common.

- Because project-based learning mirrors the real-world situations students will encounter after they leave school, it can provide stronger and more relevant preparation for college and work. Student not only acquire important knowledge and skills, they also learn how to research complex issues, solve problems, develop plans, manage time, organize their work, collaborate with others, and persevere and overcome challenges, for example.

- Project-based learning reflects the ways in which today’s students learn. It can improve student engagement in school, increase their interest in what is being taught, strengthen their motivation to learn, and make learning experiences more relevant and meaningful.

- Since project-based learning represents a more flexible approach to instruction, it allows teachers to tailor assignments and projects for students with a diverse variety of interests, career aspirations, learning styles, abilities, and personal backgrounds. For related discussions, see differentiation and personalized learning .

- Project-based learning allows teachers and students to address multiple learning standards simultaneously. Rather than only meeting math standards in math classes and science standards in science classes, students can work progressively toward demonstrating proficiency in a variety of standards while working on a single project or series of projects. For a related discussion, see proficiency-based learning .

The following are few representative examples of the kinds of arguments that may be made by critics of project-based learning:

- Project-based learning may not ensure that students learn all the required material and standards they are expected to learn in a course, subject area, or grade level. When a variety of subjects are lumped together, it’s more difficult for teachers to monitor and assess what students have learned in specific academic subjects.

- Many teachers will not have the time or specialized training required to use project-based learning effectively. The approach places greater demands on teachers—from course preparation to instructional methods to the evaluation of learning progress—and schools may not have the funding, resources, and capacity they need to adopt a project-based-learning model.

- The projects that students select and design may vary widely in academic rigor and quality. Project-based learning could open the door to watered-down learning expectations and low-quality coursework.

- Project-based learning is not well suited to students who lack self-motivation or who struggle in less-structured learning environments .

- Project-based learning raises a variety of logistical concerns, since students are more likely to learn outside of school or in unsupervised settings, or to work with adults who are not trained educators.

Alphabetical Search

The Comprehensive Guide to Project-Based Learning: Empowering Student Choice through an Effective Teaching Method

Our network.

Resources and Tools

In K-12 education, project-based learning (PBL) has gained momentum as an effective inquiry-based, teaching strategy that encourages students to take ownership of their learning journey.

By integrating authentic projects into the curriculum, project-based learning fosters active engagement, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. This comprehensive guide explores the principles, benefits, implementation strategies, and evaluation techniques associated with project-based instruction, highlighting its emphasis on student choice and its potential to revolutionize education.

What is Project-Based Learning?

Project-based learning (PBL) is a inquiry-based and learner-centered instructional approach that immerses students in real-world projects that foster deep learning and critical thinking skills. Project-based learning can be implemented in a classroom as single or multiple units or it can be implemented across various subject areas and school-wide.

In contrast to teacher led instruction, project-based learning encourages student engagement, collaboration, and problem-solving, empowering students to become active participants in their own learning. Students collaborate to solve a real world problem that requires content knowledge, critical thinking, creativity, and communication skills.

Students aren’t only assessed on their understanding of academic content but on their ability to successfully apply that content when solving authentic problems. Through this process, project-based learning gives students the opportunity to develop the real-life skills required for success in today’s world.

Positive Impacts of Project-Based Learning

By integrating project-based learning into the classroom, educators can unlock a multitude of benefits for students. The research evidence overwhelmingly supports the positive impact of PBL on students, teachers, and school communities. According to numerous studies (see Deutscher et al, 2021 ; Duke et al, 2020 ; Krajick et al, 2022 ; Harris et al, 2015 ) students in PBL classrooms not only outperform non-PBL classrooms academically, such as on state tests and AP exams, but also the benefits of PBL extend beyond academic achievement, as students develop essential skills, including creativity, collaboration, communication, and critical thinking. Additional studies documenting the impact of PBL on K-12 learning are available in the PBL research annotated bibliography on the New Tech Network website.

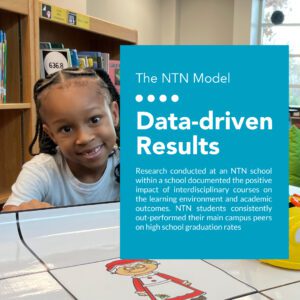

New Tech Network Project-Based Learning Impacts

Established in 1996, New Tech Network NTN is a leading nonprofit organization dedicated to transforming teaching and learning through innovative instructional practices, with project-based learning at its core.

NTN has an extensive network of schools across the United States that have embraced the power of PBL to engage students in meaningful, relevant, and challenging projects, with professional development to support teachers in deepening understanding of “What is project-based learning?” and “How can we deliver high quality project-based learning to all students?”

With over 20 years of experience in project-based learning, NTN schools have achieved impactful results. Several research studies documented that students in New Tech Network schools outperform their peers in non-NTN schools on SAT/ACT tests and state exams in both math and reading (see Hinnant-Crawford & Virtue, 2019 ; Lynch et al, 2018 ; Stocks et al, 2019 ). Additionally, students in NTN schools are more engaged and more likely to develop skills in collaboration, agency, critical thinking, and communication—skills highly valued in today’s workforce (see Ancess & Kafka, 2020 ; Muller & Hiller, 2020 ; Zeiser, Taylor, et al, 2019 ).

NTN provides comprehensive support to educators, including training, resources, and ongoing coaching, to ensure the effective implementation of problem-based learning and project-based learning. Through their collaborative network, NTN continuously shares best practices, fosters innovation, enables replication across districts, and empowers educators to create transformative learning experiences for their students (see Barnett et al, 2020 ; Hernández et al, 2019 ).

Key Concepts of Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning is rooted in several key principles that distinguish it from other teaching methods. The pedagogical theories that underpin project-based learning and problem-based learning draw from constructivism and socio-cultural learning. Constructivism posits that learners construct knowledge through active learning and real world applications. Project-based learning aligns with this theory by providing students with opportunities to actively construct knowledge through inquiry, hands-on projects, real-world contexts, and collaboration.

Students as active participants

Project-based learning is characterized by learner-centered, inquiry-based, real world learning, which encourages students to take an active role in their own learning. Instead of rote memorization of information, students engage in meaningful learning opportunities, exercise voice and choice, and develop student agency skills. This empowers students to explore their interests, make choices, and take ownership of their learning process, with teachers acting as facilitators rather than the center of instruction.

Real-world and authentic contexts

Project-based learning emphasizes real-world problems that encourage students to connect academic content to meaningful contexts, enabling students to see the practical application of what they are learning. By tackling personally meaningful projects and engaging in hands-on tasks, students develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter and its relevance in their lives.

Collaboration and teamwork

Another essential element of project-based learning is collaborative work. Students collaborating with their peers towards the culmination of a project, mirrors real-world scenarios where teamwork and effective communication are crucial. Through collaboration, students develop essential social and emotional skills, learn from diverse perspectives, and engage in constructive dialogue.

Project-based learning embodies student-centered learning, real-world relevance, and collaborative work. These principles, rooted in pedagogical theories like constructivism, socio-cultural learning, and experiential learning, create a powerful learning environment, across multiple academic domains, that foster active engagement, thinking critically, and the development of essential skills for success in college or career or life beyond school.

A Unique Approach to Project-Based Learning: New Tech Network

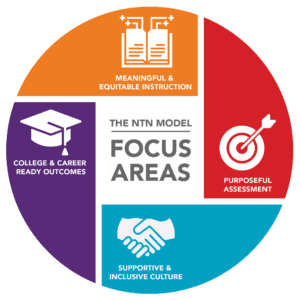

New Tech Network schools are committed to these key focus areas: college and career ready outcomes, supportive and inclusive culture, meaningful and equitable instruction, and purposeful assessment.

In the New Tech Network Model, rigorous project-based learning allows students to engage with material in creative, culturally relevant ways, experience it in context, and share their learning with peers.

Why Undertake this Work?

Teachers, administrators, and district leaders undertake this work because it produces critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and collaborators who are vital to the long-term health and wellbeing of our communities.

Reynoldsburg City Schools (RCS) Superintendent Dr. Melvin J. Brown observed that “Prior to (our partnership with New Tech Network) we were just doing the things we’ve always done, while at the same time, our local industry was evolving and changing— and we were not changing with it. We recognized we had to do better to prepare kids for the reality they were going to walk into after high school and beyond.

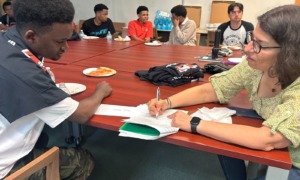

Students embrace the Model because they feel a sense of belonging. They are challenged to learn in relevant, meaningful ways that shape the way they interact with the world, like these students from Owensboro Innovation Academy in Owensboro, Kentucky .

When change is collectively held and supported rather than siloed, and all stakeholders are engaged rather than alienated, schools and districts build their own capacity to sustain innovation and continuously improve. New Tech Network’s approach to change provides teachers, administrators, and district leaders with clear roles in adopting and adapting student-centered learning.

Part of NTN’s process for equipping schools with the data they need to serve their students involves conducting research surveys about their student’s experiences.

“The information we received back from our NTN surveys about our kids’ experiences was so powerful,” said Amanda Ziaer, Managing Director of Strategic Initiatives for Frisco ISD. “It’s so helpful to be reminded about these types of tactics when you’re trying to develop an authentic student-centered learning experience. It’s just simple things you might skip because we live in such a traditional adult-centered world.”

NTN’s experienced staff lead professional development activities that enable educators to adapt to student needs and strengths, and amplify those strengths while adjusting what is needed to address challenges.

Meaningful and Equitable Instruction

The New Tech Network model is centered on a PBL instructional core. PBL as an instructional method overlaps with key features of equitable pedagogical approaches including student voice, student choice, and authentic contexts. The New Tech Network model extends the power of PBL as a tool for creating more equitable learning by building asset-based equity pedagogical practices into the the design using key practices drawn from the literature on culturally sustaining teaching methods so that PBL instruction leverages the assets of diverse students, supports teachers as warm demanders, and develops critically conscious students in PBL classrooms (see Good teaching, warm and demanding classrooms, and critically conscious students: Measuring student perceptions of asset-based equity pedagogy in the classroom ).

Examples of Project-Based Learning

New Tech Network schools across the country create relevant projects and interdisciplinary learning that bring a learner-centered approach to their school. Examples of NTN Model PBL Projects are available in the NTN Help and Learning Center and enable educators to preview projects and gather project ideas from various grade levels and content areas.

The NTN Project Planning Toolkit is used as a guide in the planning and design of PBL. The Project-based learning examples linked above include a third grade Social Studies/ELA project, a seventh grade Science project, and a high school American Studies project (11th grade English Language Arts/American History).

The Role of Technology in Project-Based Learning

A tool for creativity

Technology plays a vital role in enhancing PBL in schools, facilitating student engagement, collaboration, and access to information. At the forefront, technology provides students with tools and resources to research, analyze data, and create multimedia content for their projects.

A tool for collaboration

Technology tools enable students to express their understanding creatively through digital media, such as videos, presentations, vlogs, blogs and interactive websites, enhancing their communication and presentation skills.

A tool for feedback

Technology offers opportunities for authentic audiences and feedback. Students can showcase their projects to a global audience through online platforms, blogs, or social media, receiving feedback and perspectives from beyond the classroom. This authentic audience keeps students engaged and striving for high-quality work and encourages them to take pride in their accomplishments.

By integrating technology into project-based learning, educators can enhance student engagement, deepen learning, and prepare students for a digitally interconnected world.

Interactive PBL Resources

New Tech Network offers a wealth of resources to support educators in gaining a deeper understanding of project-based learning. One valuable tool is the NTN Help Center, which provides comprehensive articles and resources on the principles and practices of implementing project-based learning.

Educators can explore project examples in the NTN Help Center to gain inspiration and practical insights into designing and implementing PBL projects that align with their curriculum and student needs.

Educators can start with the article “ What are the basic principles and practices of Project-Based Learning? Doing Projects vs. PBL . ” The image within the article clarifies the difference between the traditional education approach of “doing projects” and true project-based learning.

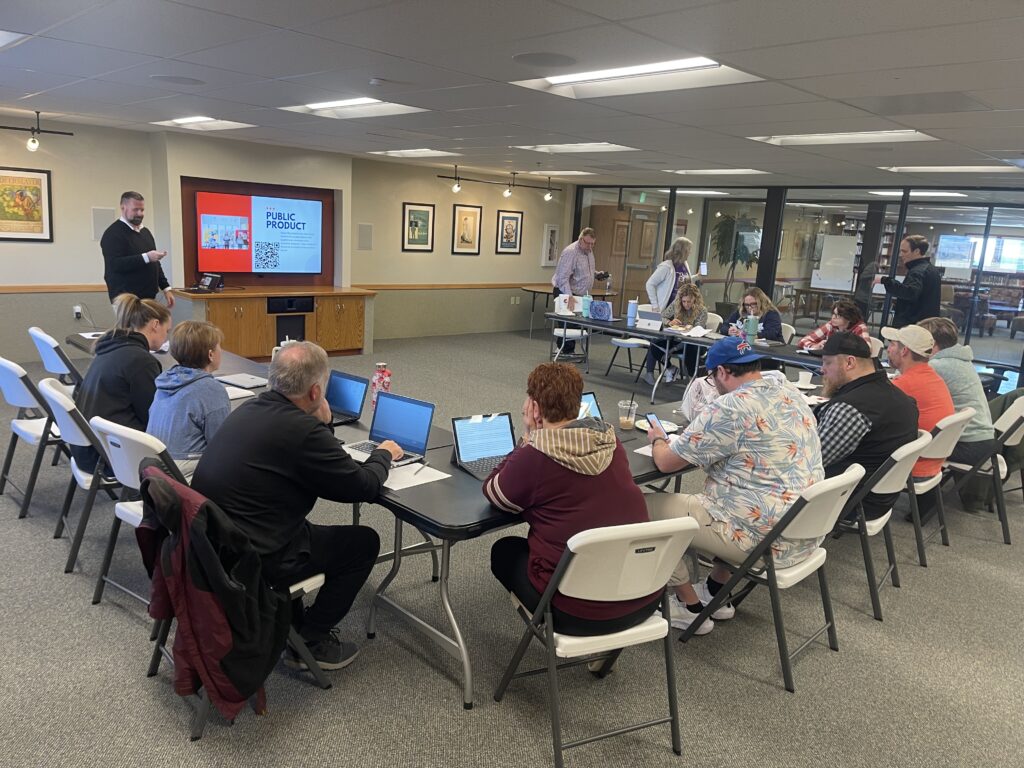

Project Launch

Students are introduced to a project by an Entry Event in the Project Launch (designated in purple on the image) this project component typically requires students to take on a role beyond that of ‘student’ or ‘learner’. This occurs either by placing students in a scenario that has real world applications, in which they simulate tasks performed by adults and/or by requiring learners to address a challenge or problem facing a particular community group.

The Entry Event not only introduces students to a project but also serves as the “hook” that purposefully engages students in the launch of a project. The Entry Event is followed by the Need to Know process in which students name what they already know about a topic and the project ask and what they “need to know” in order to solve the problem named in the project. Next steps are created which support students as they complete the Project Launch phase of a project.

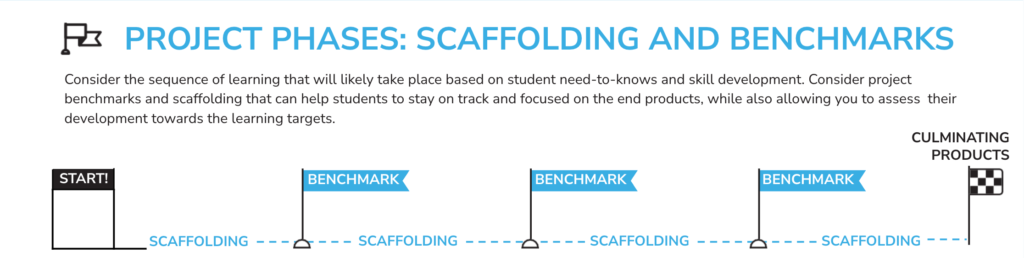

Scaffolding

Shown in the image in red, facilitators ensure students gain content knowledge and skills through ‘scaffolding’. Scaffolding is defined as temporary supports for students to build the skills and knowledge needed to create the final product. Similar to scaffolding in building construction, it is removed when these supports are no longer needed by students.

Scaffolding can take the form of a teacher providing support by hosting small group workshops, students engaging in independent research or groups completing learner-centered activities, lab investigations, formative assessments and more.

Benchmarks (seen in orange in the image) can be checks for understanding that allow educators to give feedback on student work and/or checks to ensure students are progressing in the project as a team. After each benchmark, students should be given time to reflect on their individual goals as well as their team goals. Benchmarks are designed to build on each other to support project teams towards the culminating product at the end of the project.

NTN’s Help Center also provides resources on what effective teaching and learning look like within the context of project-based learning. The article “ What does effective teaching and learning look like? ” outlines the key elements of a successful project-based learning classroom, emphasizing learner-centered learning, collaborative work, and authentic assessments.

Educators can refer to this resource to gain insights into best practices, instructional strategies, and classroom management techniques that foster an engaging and effective project-based learning environment.

From understanding the principles and practices of PBL to accessing examples of a particular project, evaluating project quality, and exploring effective teaching and learning strategies, educators can leverage these resources to enhance their PBL instruction and create meaningful learning experiences for their students.

Preparing Students for the Future with PBL

The power of PBL is the way in which it encourages students to think critically, collaborate, and sharpen communication skills, which are all highly sought-after in today’s rapidly evolving workforce. By engaging in authentic, real-world projects, and collaborating with business and community leaders and community members, students develop the ability to tackle complex problems, think creatively, and adapt to changing circumstances.

These skills are essential in preparing students for the dynamic and unpredictable nature of the future job market, where flexibility, innovation, and adaptability are paramount.

“Joining New Tech Network provides us an opportunity to reframe many things about the school, not just PBL,” said Bay City Public Schools Chief Academic Officer Patrick Malley. “Eliminating the deficit mindset about kids is the first step to establishing a culture that makes sure everyone in that school is focused on next-level readiness for these kids.”

The New Tech Network Learning Outcomes align with the qualities companies are looking for in new hires: Knowledge and Thinking, Oral Communication, Written Communication, Collaboration and Agency.

NTN schools prioritize equipping students with the necessary skills and knowledge to pursue postsecondary education or training successfully. By integrating college readiness and career readiness into the fabric of PBL, NTN ensures that students develop the academic, technical, and professional skills needed for future success.

Through authentic projects, students learn to engage in research, analysis, and presentation of their work, mirroring the expectations and demands of postsecondary education and the workplace. NTN’s commitment to college and career readiness ensures that students are well-prepared to transition seamlessly into higher education or enter the workforce with the skills and confidence to excel in their chosen paths.

The Impact of PBL on College and Career Readiness

PBL has a profound impact on college and career readiness. Numerous studies document the academic benefits for students, including performance in AP courses, SAT/ACT tests, and state exams (see Deutscher et al, 2021 ; Duke et al, 2020 ; Krajick et al, 2022 ; Harris et al, 2015 ). New Tech Network schools demonstrate higher graduation rates and college persistence rates than the national average as outlined in the New Tech Network 2022 Impact Report . Over 95% of NTN graduates reported feeling prepared for the expectations and demands of college.

Practices that Support Equitable College Access and Readiness

According to a literature review conducted by New York University’s Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools ( Perez et al, 2021 ) classroom level, school level, and district level practices can be implemented to create more equitable college access and readiness and these recommendations align with many of the practices built into the the NTN model, including culturally sustaining instructional approaches, foundational literacy, positive student-teacher relationships, and developing shared asset-based mindsets.

About New Tech Network

New Tech Network is committed to meeting schools and districts where they are and helping them achieve their vision of student success. For a full list of our additional paths to impact or to speak with someone about how the NTN Model can make an impact in your district, please send an email to [email protected] .

Sign Up for the NTN Newsletter

Disclosure: MyeLearningWorld is reader-supported. We may receive a commission if you purchase through our links.

What is Project-Based Learning? A Complete Guide For Educators

Published on: 12/04/2023

By Julia Bashore

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Reddit

- Share on Pinterest

Project-based learning is a hands-on educational approach where students gain knowledge and skills by working for an ongoing, extended project to investigate and respond to a complex question, problem, or challenge.

In today’s educational world, it’s easy to feel like standardized tests have all the power. From elementary to high school, multiple-choice tests carry a great deal of weight concerning everything from district funding to college admissions. Despite this, though, standardized tests aren’t exactly exciting, nor are they especially empowering for students.

As a teacher myself, I can tell that many of us lament the relentless drilling of skills to prepare students for a test they probably won’t even remember a few months later, but without standardized tests, how can we engage students in learning and applying important content?

The answer lies in Project-Based Learning. Researchers discovered that almost 50% of students in project-based learning environments successfully passed their AP exams, surpassing their peers in conventional classrooms by a margin of 8 percentage points. Let’s find out why…

What is Project Based Learning?

Project-Based Learning, or PBL, is rooted in action . Students work on an ongoing project related to their grade level standards and receive scores and feedback for each milestone they accomplish.

Rather than focusing on teacher-led discussions, Project-Based Learning lets students make discoveries on their own. By working on a project for an extended period of time, students gradually build their problem-solving and critical thinking skills while acquiring and applying new knowledge.

This approach puts learning directly in the hands of the students. Instead of simply memorizing facts or plugging in numbers, they must collaborate with one another to grow in their abilities to reason, revise, and reflect on solutions for an ongoing educational question or challenge. This active engagement fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills, encouraging students to take ownership of their learning journey and apply their knowledge in practical, real-world contexts.

How is Project Based Learning Different From “Normal” Classroom Projects?

Project Based Learning may sound familiar to anyone who recalls throwing together a science fair project or crafting a book report diorama back in the day. Authentic PBL, however, is a far deeper dive into knowledge and learning than the classroom projects we remember from yesteryear.

In order to fit the criteria of Project Based Learning, the assignment students are working on cannot merely be an accessory to a unit of study. Instead, the project is the unit of study.

Consider a second-grade reading class learning about different story genres. In a traditional classroom setting, students might complete several quizzes and tests on each type of story, then put together a simple report or poster highlighting their favorite at the end of the unit. While this is a perfectly viable way to teach this content, it’s not Project-Based Learning.

Project Based Learning might achieve the same goal by giving students a challenging question to work towards over the semester, such as: How can we make different types of stories come alive for young readers in the community?

Students would then be placed into teams or groups and given time to brainstorm their ideas. They would work together to closely read several examples of each genre and map out storyboards and scripts to make them “come alive.”

Students would then revise and edit together before finalizing video performances of their favorite stories. Each video might include a rubric of important plot elements, as well as a summary of the story’s main idea or theme.

Students could publish their completed video projects to a schoolwide channel or play them for other classes to share their finished work. They might then reflect with one another on how and why it’s important to keep stories engaging and exciting for future readers.

This project, adapted from The Storytime Channel example offered by MyPBLWorks , is an example of an ongoing, meaningful project that comprises an entire in-depth unit of study.

The project itself is multi-faceted and requires thorough knowledge and understanding of the topic, as well as the capacity for critical thinking and self-reflection.

Instead of merely being the “cherry on top,” the project in a PBL classroom is the entire main dish.

How to Go for the Gold with Project Based Learning

To reach that main dish level of impact, Project Based Learning assignments should ideally incorporate seven project design elements. Take a look at each below to get a better understanding of why they work together to form meaningful, successful projects.

- Challenging Problem or Question. In order for a project to help students grow academically, it needs to spark curiosity. PBL projects are centered around solving meaningful problems or answering impactful questions, rather than simply following directions. Again, consider the difference between “How can we make different types of stories come alive for young readers?” versus “Describe and give examples of your three favorite story genres.” A meaningful question creates a more empowering goal for students to work towards.

- Sustained Inquiry. Students should go through several rigorous cycles of asking questions, researching answers, and applying new skills as they work to complete their projects. There should be ongoing growth as students wonder, learn, and then continue to wonder and learn at a more sophisticated level. If the assignment or activity does not prompt sustained inquiry over the course of time it takes to reach completion, then the project is not in-depth enough for real Project-Based Learning.

- Authenticity. Just as the project’s central question or problem should be meaningful, every step along the way should also be rooted in real-world skills that matter to students’ everyday lives. The project should be based in an authentic context and have a clear impact on students’ personal concerns and interests. By keeping authentic issues at the crux of the project, students are able to widen their focus, think more deeply, and, ultimately, get more out of their learning.

- Student Voice & Choice. Projects should also be structured to allow all of the contributors to express themselves. Students should have a say in decisions related to the project, and each group member should be able to make choices on the roles they will play throughout the experience. As students get more confident in voicing their strengths and ideas, they will not only submit better work, but will also become better advocates for themselves. Allowing students to have a measure of control over the work they do creates more personal investment and engagement in the process, and helps each individual tap into their own potential.

- Reflection. Making time for genuine reflection is often an overlooked part of today’s educational world, but I’ve found it’s one of the most essential steps in actually growing as a learner. PBL classrooms factor in time for students and teachers to review the effectiveness of each project-based activity. Teachers can offer praise and guidance as students continue to progress, and students can identify areas where they have done well and where they might wish to improve. This results in a clearer understanding of expectations and a more thoughtful approach to each element of the project.

- Critique & Revision. Following a period of reflection, students are also expected to give and receive meaningful feedback throughout each unit’s project. By collaborating on and revising their work, students create a more polished final product and learn to be comfortable with criticism. Learning to carefully and kindly critique a teammate’s work can build a student’s own thinking and learning potential. On the other hand, practicing how to gracefully respond to others’ suggestions is an important skill both in and out of the academic world.

- Public Product. In PBL classrooms, students celebrate the completion of their hard work by presenting or displaying it to folks outside of the classroom itself. Whether it’s a performance, a presentation, a published booklet, a video, a speech, or a display at a local library or community center, making a finished product public is a huge part of PBL. By taking finished projects outside the classroom, students can take ownership and feel proud of the real work they’ve accomplished.

Make PBL Work For Your Class

These seven gold-standard criteria are easy to implement across a variety of classroom levels. From Kindergarten to high school, meaningful projects are always an important way to engage students and teach them to grow as classmates, researchers, and citizens.

Students in first grade may work in teams to design their ideal playground as they learn about force, motion, and simple machines. They can practice simple math facts as they calculate the height of slides and swings, and work on their writing and reading skills as they record and diagram their ideas. Finished ideas could be shared with the principal or displayed around local parks.

Students in fifth grade, meanwhile, might work to raise awareness about endangered animals by researching and writing about their habitats, predators, and defenses. They could then design nonfiction books to distribute to their community and film campaigns suggesting ways to protect these animals in the future.

Middle schoolers, on the other hand, could team up to create an app that would benefit young people’s learning. They could brainstorm, practice writing pitches, and ultimately learn about coding as they create an app in the field of their choosing. Completed apps could be shared online or in a school-wide demo or fair.

Down the line, high schoolers might be involved in projects centered around local or international issues, such as promoting clean water quality, conserving natural resources, or solving issues like homelessness in the community. These projects could be presented to the school board or local officials, as well as displayed on social media, to create authentic buy-in.

Moving Forward with Project Based Learning

Clearly, there are no limits to the potential of Project Based Learning. If you can dream it, your students can do it.

Whether you’re teaching how to read , how to code , math, science, or something else, there are plenty of ways to incorporate PBL.

By adapting your vision to encompass the seven gold-standard criteria, you can guarantee that your project will promote collaboration, growth, and academic rigor for all the members of your class.

While PBL may take a bit more effort than grading those fill-in-the-blank worksheets, I truly believe that implementing it effectively will give your students the chance to achieve thorough, meaningful knowledge about a topic that genuinely interests them and contributes to their society.

Not a lot of standardized tests can boast the same.

Other Useful Resources

- What is Adaptive Learning?

- What is Inquiry Based Learning?

- What is Just in Time Learning?

- What is Microlearning?

- What is Problem Based Learning?

- What is Service Learning?

Have any questions about Project Based Learning? Let us know by leaving a comment below.

What is Inquiry-Based Learning? A Complete Guide for Educators

What quiz format should you use in your online course 7 different types, leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Project-Based Learning

This teaching guide explores the different types of project-based learning (PBL), its benefits, and tips for implementation in your classes.

Introduction

Project-based learning (PBL) involves students designing, developing, and constructing hands-on solutions to a problem. The educational value of PBL is that it aims to build students’ creative capacity to work through difficult or ill-structured problems, commonly in small teams. Typically, PBL takes students through the following phases or steps:

- Identifying a problem

- Agreeing on or devising a solution and potential solution path to the problem (i.e., how to achieve the solution)

- Designing and developing a prototype of the solution

- Refining the solution based on feedback from experts, instructors, and/or peers

Depending on the goals of the instructor, the size and scope of the project can vary greatly. Students may complete the four phases listed above over the course of many weeks, or even several times within a single class period.

Because of its focus on creativity and collaboration, PBL is enhanced when students experience opportunities to work across disciplines, employ technologies to make communication and product realization more efficient, or to design solutions to real-world problems posed by outside organizations or corporations. Projects do not need to be highly complex for students to benefit from PBL techniques. Often times, quick and simple projects are enough to provide students with valuable opportunities to make connections across content and practice.

Implementing project-based learning

As a pedagogical approach, PBL entails several key processes:

- Defining problems in terms of given constraints or challenges

- Generating multiple ideas to solve a given problem

- Prototyping — often in rapid iteration — potential solutions to a problem

- Testing the developed solution products or services in a “live” or authentic setting.

Defining the problem

PBL projects should start with students asking questions about a problem. What is the nature of problem they are trying to solve? What assumptions can they make about why the problem exists? Asking such questions will help students frame the problem in an appropriate context. If students are working on a real-world problem, it is important to consider how an end user will benefit from a solution.

Generating ideas

Next, students should be given the opportunity to brainstorm and discuss their ideas for solving the problem. The emphasis here is not to generate necessarily good ideas, but to generate many ideas. As such, brainstorming should encourage students to think wildly, but to stay focused on the problem. Setting guidelines for brainstorming sessions, such as giving everyone a chance to voice an idea, suspending judgement of others’ ideas, and building on the ideas of others will help make brainstorming a productive and generative exercise.

Prototyping solutions

Designing and prototyping a solution are typically the next phase of the PBL process. A prototype might take many forms: a mock-up, a storyboard, a role-play, or even an object made out of readily available materials such as pipe cleaners, popsicle sticks, and rubber bands. The purpose of prototyping is to expand upon the ideas generated during the brainstorming phase, and to quickly convey a how a solution to the problem might look and feel. Prototypes can often expose learners’ assumptions, as well as uncover unforeseen challenges that an end user of the solution might encounter. The focus on creating simple prototypes also means that students can iterate on their designs quickly and easily, incorporate feedback into their designs, and continually hone their problem solutions.

Students may then go about taking their prototypes to the next level of design: testing. Ideally, testing takes place in a “live” setting. Testing allows students to glean how well their products or services work in a real setting. The results of testing can provide students with important feedback on the their solutions, and generate new questions to consider. Did the solution work as planned? If not, what needs to be tweaked? In this way, testing engages students in critical thinking and reflection processes.

Unstructured versus structured projects

Research suggests that students learn more from working on unstructured or ill-structured projects than they do on highly structured ones. Unstructured projects are sometimes referred to as “open ended,” because they have no predictable or prescribed solution. In this way, open ended projects require students to consider assumptions and constraints, as well as to frame the problem they are trying to solve. Unstructured projects thus require students to do their own “structuring” of the problem at hand – a process that has been shown to enhance students’ abilities to transfer learning to other problem solving contexts.

Using Design Thinking in Higher Education (Educause)

Design Thinking and Innovation (GSM SI 839)

Project Based Learning through a Maker’s Lens (Edutopia)

You may also be interested in:

Case-based learning, game-based learning & gamification, assessment for experiential learning, designing experiential learning projects, creativity/innovation hub guide, partnerships in experiential learning: faq, experiential learning resources for faculty: introduction, reflection for experiential learning.

Project-Based Learning

What is project-based learning.

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is more than just a teaching method. It is a revitalization of education for students so that they can develop intellectually and emotionally. By using real-world scenarios, challenges, and problems, students gain useful knowledge and skills that increase during their designated project periods. The goal of using complex questions or problems is to develop and enhance student learning by encouraging critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork, and self-management. The project’s proposed question drives students to make their own decisions, perform their own research, and review their own and fellow students’ processes and projects.

Discover our On-Site & Virtual PBL Workshops that best fit your needs!

One-day pbl workshops.

- Discover Fundamentals of PBL Pedagogy

- Learn How to Plan and Implement Projects

- Fits into your PD Schedule

Multi-Day PBL Workshops

- Learn High-Quality PBL Standards

- Earn Graduate-Level Continuing Education Units (CEU/PDU)

- Become PBL Certified

Long Term Coaching & Workshops

- Ensure Your PD is Longer Term, Collaborative & Job-Embedded

- Accessible PBL Professional Development

- Enhance & Hone High Quality PBL Delivery and Project Management

Schedule a Free Consultation with us about Project-Based Learning today!

Personal information.

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Phone Number *

School Information

- School Name *

- Job / Role at School *

- State * Alabama Alaska Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Texas Utah Vermont Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming

- ZIP / Postal Code *

- PBL Certification Training

- PBL and Technology Integration

- Long Term PBL Consulting

- Google Search

- Word of Mouth

Why Project-Based Learning?

We believe that PBL is an integral key to increasing student success and long-term growth. The combination of collaboration, reflection, and individual decision-making gives the students an applicable scenario to real-world situations that they will face as they mature. Moreover, we believe that the authenticity of PBL allows students to voice their personal interests, concerns, or issues that are significant parts of their lives. Instead of a pre-determined project or assignment, students can witness the issues or concerns in their community, discover one that they find particularly interesting, and brainstorm ways to address or solve the problem.

Allowing students to have this control, we believe that PBL can develop deeper learning proficiencies necessary for tertiary education, careers, and life in society. School becomes much more engaging through active participation in projects that focus on real-world issues rather than passively attending classes. Furthermore, PBL provides content and skills that students can actively apply in future life events and situations.

Using PBL is not only beneficial to students; it also makes teaching much more gratifying and pleasurable. Teachers have the chance to engage with students on a higher personal level by discovering their interests and concerns and then performing important, high-quality work alongside them. Through this, teachers and students alike can revive their passion for learning.

In addition to finding resources, developing project timelines, and learning to overcome obstacles, students have the opportunity to publicly display their work. Displaying their completed projects in public gives the students the chance to grow their public speaking and presentation skills while explaining their project’s outcome to individuals outside of the classroom.

At Educators of America, we believe that PBL is one of the best ways to connect students and their schools to their surrounding communities and the real world. We believe that projects developed by PBL methods are empowering students and teachers to make a real difference. Whether that be developing a sustainable school garden or investigating cell phone service providers to analyze the best plan for them and their families; the opportunities with PBL are endless.

Technology and PBL

Students and teachers today are very familiar with new technology and technological tools. When deploying PBL, students can perform better research, collect outside information, and collaborate easier and faster with fellow students, teachers, and industry experts.

Presentations are no longer tri-folds and printed datasheets, with technology, students can display presentations that better visualize their results and development process to audiences both in and outside of the classroom. When speaking of audiences and how the students present to them, technology becomes an avenue of authenticity whereby students can connect with members of an audience via video or telecommunications during the middle or at the end of a project.

Furthermore, by using technology in conjunction with PBL, students can use the technological tools available to them most effectively and how they can use them with an intentional purpose. By gaining a deeper understanding of why technology exists and how it can be used, students develop an advanced literacy of the technology they use. The creation of this knowledge can lead to future habits or practices of project management and collaboration in students’ education, career, and civic participation. As students collaborate on a project, technology such as Evernote, Edmodo, and Wikis, becomes essential for storing data and information. Teachers can also use these technologies to send out the necessary material and files to learners and students.

As mentioned previously, the concept of technology literacy is a skill that in the 21st century seems standard. However, how is it measured? How do teachers and students assess themselves in terms of proficiency? Teachers can use quality indicators from ISTE NETS for measuring their students’ use of technology. It not only provides rubrics but also allows students to reflect on what they have learned and seek opportunities to gain more technology information from classmates or educators.

There are a plethora of avenues and means to adopt PBL into your classroom, school, or community. At Educators of America, our goal is to help you do just that .

Learn About Our Programs

Learn more about all of the current programs offered from Educators of America!

Get Involved

Discover how you, your organization or your business can get involved with Educators of America today.

See What We're Up To

See what Educators of America is up to and get helpful information on PBL, MicroGrants, and more on our Blog!

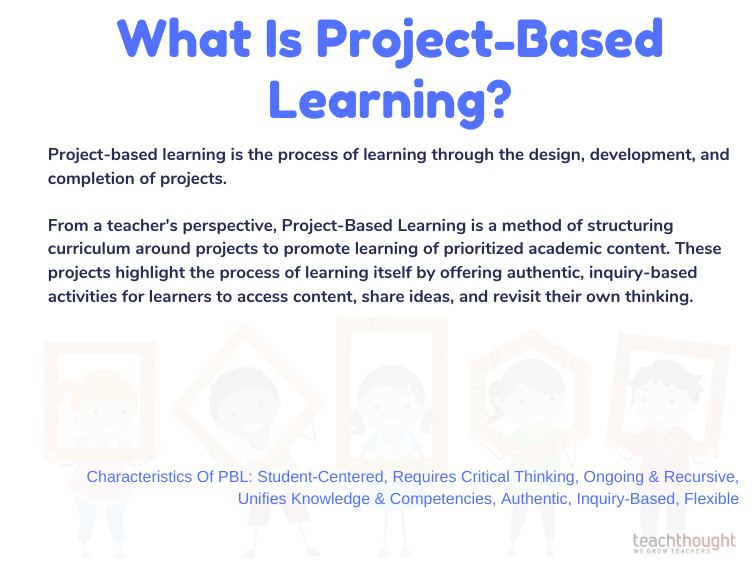

What Is Project-Based Learning?

Project-based learning is the student-centered process of learning through the design, development, and completion of projects.

Project-Based Learning? A Definition.

by Terry Heick

In one sentence, project-based learning (PBL) is the process of learning through projects.

To be a bit more specific, PBL is the process of learning through the design, development, and completion of projects.

It can be useful to think of it in terms of what it’s not– The Difference Between Projects And Project-Based Learning , for example. PBL is not completing projects or it’d be called ‘Learning-Based Projects’–or just ‘projects.’ In quality PBL, the goal is learning and the projects help facilitate that learning. That is, projects act as vehicles.

PBL depends on background knowledge, learner choice, technology tools, support from others, and dozens of other factors that result in a process of learning that produces very different results and ‘projects’

In 3 Types Of Project-Based Learning , we gave a definition for project-based learning that we’re using as a basis to push the idea a bit further.

Characteristics Of Project-Based Learning

What are the characteristics of PBL? According to Joseph S. Krajcik and Phyllis C. Blumenfeld in The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (2006)–who quote the research of Blumenfeld et al., 1991; Krajcik, et al., 1994; Krajcik, Czerniak, & Berger, 2002)–PBL experiences:

“They start with a driving question, a problem to be solved.

Students explore the driving question by participating in authentic, situated inquiry – processes of problem-solving that are central to expert performance in the discipline. As students explore the driving question, they learn and apply important ideas in the discipline.

Students, teachers, and community members engage in collaborative activities to find solutions to the driving question. This mirrors the complex social situation of expert problem-solving.

While engaged in the inquiry process, students are scaffolding with learning technologies that help them participate in activities normally beyond their ability.

Students create a set of tangible products that address the driving question. These are shared artifacts, publicly accessible external representations of the class’s learning.”

Benefits Of Project-Based Learning

- Requires critical thinking (e.g., design, evaluation, analysis, judgment, prioritizing, etc.). This is in contrast to other forms of learning that hope to ‘promote’ critical thinking but can be accomplished without it.

- Driven by inquiry

- Combines knowledge and competencies/skills

- Illuminates learning as iterative and recursive (as opposed to learn–>study–>assess–>move on)

- Student-Centered

- Unifies other disparate skills

- Easy to align with standards

Teaching Through Project-Based Learning

From a teacher’s perspective, Project-Based Learning is a method of structuring curriculum around projects to promote learning of prioritized academic content. These projects highlight the process of learning itself by offering authentic, inquiry-based activities for learners to access content, share ideas, and revisit their own thinking.

At the risk of becoming redundant, return again to the difference between projects and project-based learning–primarily that Project-Based Learning is about the process , and projects are about the product that comes at the end.

Project-Based Learning often requires students not simply to collect resources, organize work, and manage long-term activities, but also to collaborate, design, revise, and share their ideas and experiences with authentic audiences and supportive peer groups in the classroom, or within physical and digital communities the student is a member of and contributes to.

Founder & Director of TeachThought

mySmowltech

Project-based learning: definition, benefits and ideas

Learning and Development

Table of contents

Project-based learning is a teaching method in which students apply an active inquiry approach to real-world challenges and problems.

Organizing and implementing the project-based learning method of teaching includes a commitment on the part of all those involved to carry out activities in which the investigation of authentic real-world problems, the development of solutions and discussion are key.

To provide you with an approach to this type of teaching, in this article we will take you by the hand through the subject. We will start by explaining what project-based learning is , then we will show you its benefits and end by sharing with you a series of ideas related to the subject.

What is project-based learning?

Project-based learning or PBL is a teaching method in which the curriculum takes the student as the center of reference to develop learning through research, questions and the resolution of non-fictional situations in the real world.

The teacher’s role is one of accompaniment and does not instruct the students, but rather it is the students who face a learning process that must be open, participatory and focused on critical thinking, communication, collaboration and creativity.

PBL is such an attractive process as to encourage students to engage in it and develop their own approaches by delving deeper into answers and solutions to present a final resolute result.

With the final presentation of the prototypes, students show the problems solved, the research processes and methods used, as well as the results obtained.

From all this, they can receive feedback and undergo a review of the plans and the projects as if it were one in real life.

9 benefits of project-based learning

Implementing a curriculum focused on project-based learning brings a number of benefits that we detail below:

Strengthens long-term retention of what is learned

The direct research process to find solutions, measures and tools, as well as the practical involvement in the resolution of the project, make the learning more established and last longer in the student’s memory.

On the other hand, the fact of being personally involved makes the concentration on learning to be more intense and the final performance also yields better results.

Subscribe today to SMOWL’s weekly newsletter!

Discover the latest trends in eLearning, technology, and innovation, alongside experts in assessment and talent management. Stay informed about industry updates and get the information you need.

Simply fill out the form and stay up-to-date with everything relevant in our field.

It generates intrinsic motivation and engagement

The student’s participation in this type of teaching is voluntary and is usually a response to a self-motivation to learn in a different way.

Believing that this is the learning that best fits their expectations of study, leads the student to a greater commitment to the project.

Improves technological skills

The irruption of ICTs in education has meant a wonderful discovery of the power of technology when it comes to improving learning processes.

Among the tools to consult and use, the technological ones are especially relevant, helping the student to carry out research with a much wider range of sources consulted -always under the premise of respect for digital privacy – and with a saving of search times also to be taken into account.

Enhances project management competence

Students are submitted to the resolutions by themselves -or in a team- of a project based on real problems.

The achievement of the project is obtained by going through the whole management process from the beginning to the end.

Project-based learning can be focused on large, long projects or on smaller projects. Also, as we have anticipated, it can correspond to a solo project or to collaborative projects with other students with whom to form a team.

Encourages active and continuous learning

Tackling a possibly unfamiliar starting project involves a thorough investigation of topics and resources that perfectly symbolizes active learning .

Students search for the resources and means that will help them create the prototype of the final project to be presented.

Once students have discovered the benefits of research and documentation, their receptiveness to participate naturally in continuous learning processes is self-evident.

Develops communication skills

The learner must be able to communicate with others the needs, solutions or results they are obtaining as their work progresses.

Whether we focus on communication with other team members, when the project so requires, or if we talk about a solo project, in all cases the ability to communicate the aspects mentioned in the previous paragraph are key to a successful achievement.

If communication fails, does not exist or is erroneous, the factors associated with it, such as the correct understanding of the project, can be compromised.

In addition to presenting their impressions and views, learners must be able to listen to the opinions of others.

Boosts collaborative and teamwork skills

Collaborative and teamwork skills are directly related to communication and engagement, and help the learner develop relationships that are key to their academic and personal growth.

These collaborative skills end up extending and creating a development of peers, professional networks and members of the industry.

Reinforces creativity

Students enrolled in project-based learning programs are more predisposed to think innovatively and creatively.

This is logical when you consider that they have total freedom to explore different approaches and methods, as well as being an excellent opportunity to express their personality and talent through their work.

Enhances critical thinking and problem solving skills

This benefit makes sense, since the student is confronted with the pragmatic resolution of problems that are not solved in textbooks.

We are not talking about a traditional study, in this case thinking beyond the established and collected is the key to move the project forward.

10 ideas for project-based learning

There is a multitude of options that fit in the project-based learning, so we will use a battery of 10 ideas so that from them you can think of a better development of those mentioned or so that having these references you can think of your own.

- Design of a community garden.

- Create prototypes of accessories for existing machinery.

- Innovate recipes based on new cooking techniques.

- Design food programs for people with specific health problems.

- Simulate trials on specific causes.

- Create sustainable city plans.

- Research new technological applications based on renewable energies.

- Create interactive digital maps of specific regions.

- Research specific artistic movements and create their own works inspired by these movements.

- Create reports with different statistics to identify patterns of behavior after analyzing the data. After that, develop strategies for prevention or problem solving.

At Smowltech, we have been involved in developing a range of scalable, flexible and innovative proctoring products that you can offer to your students and other stakeholders in the educational community. Request a free demo , and we will be happy to show you the solutions that best fit your needs.

Download now!

8 interesting

about proctoring

Discover everything you need about online proctoring in this book to know how to choose the best software.

Fill out the form and download the guide now.

And subscribe to the weekly SMOWL newsletter to get exclusive offers and promotions .

You will discover all the trends in eLearning, technology, innovation, and proctoring at the hands of evaluation and talent management experts .

Sustainability indicators: what are they and how a business can use it

Smishing and phishing: meaning and differences

16 core HR competencies to build a strong Human Resources department

- Copyright © 2024 all rights reserved SMOWLTECH

Write below what you are looking for

Escribe a continuación lo que estas buscando

New Resources

About eduproject.

- monographs contributed by PBL practitioners and researchers;

- a handbook that focuses on the early stages of project-based learning;

- links to PBL professional development resources;

- links to open access PBL research studies, cataloged by educational level;

- a carefully selected playlist of PBL videos with discussion questions;

- an Amazon linked PBL bookstore.

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Implementing the Project Approach in an Inclusive Classroom: A Teacher’s First Attempt With Project-Based Learning (Voices)

You are here

Thoughts on the Article | Barbara A. Henderson, Voices Executive Editor

Stacey Alfonso was teaching in an inclusion preschool in New York City, serving children with a range of special learning and developmental differences when she conducted this research. As she strove to embrace the child-centered inquiry that is at the heart of the project approach, she struggled with general expectations within her school culture that curriculum and instruction be teacher directed instead of cocreated with the children. Her teacher research makes a valuable contribution to the literature because she provides clear and believable examples of how the project approach worked for the children with special needs and examples of the challenges she faced due to the newness of her approach, her lack of mentors, and the varied learning strengths of the children. Stacey is especially effective in communicating the voices and work products of the children, showing how they are fully capable and eager to undertake inquiry and direct their own learning. Her trust in the children and her joy at their discoveries provided a turning point in her career that informs her current teaching in a forest school.

One of the biggest challenges I faced during my years teaching in an inclusive prekindergarten classroom was differentiating instruction. I was constantly searching for methods to engage all children because their wide range of abilities and needs required me to offer varied outlets for learning. My school held to a theme-based curriculum with a strong backbone of structure that guided classroom activities and children’s learning. I held to this approach as well, until, as I gained experience as an educator and learned more about child development, I began to question what I was doing and to seek alternative methods.

I wanted the children in my classroom to be motivated, authentically engaged, and excited to learn. I wanted them to take hold of their learning and drive their own experiences. The children were learning; still, I felt that their experiences should be more personal than I had been able to provide using a teacher-derived curriculum. I thought this could be best accomplished in an open-ended environment where children are free to explore and follow their interests. But how could this be done within my school’s current approach? I found my answer when I discovered the project approach.

The literature I read presented a pedagogy that would motivate and engage children with a diverse range of abilities, allowing them the freedom to explore their own interests, yet still provide enough structure to fit into my school’s current culture (Harris & Gleim 2008; Beneke & Ostrosky 2009; Katz, Chard, & Kogen 2014). My research question for this study was, How can I implement the project approach in my inclusive classroom in a preschool that has a history of structured, teacher-driven curriculum?

Review of literature

John Dewey was among the first to suggest that an ideal way for children to learn is by planning their own activities and implementing those plans, thereby providing opportunities for multilevel instruction, cooperative learning, peer support, and individualized learning (Harris & Gleim 2008). Today, many teachers find that project-based learning meets Dewey’s goals (Beneke & Ostrosky 2009; Yuen 2009; Brewer 2010). Overall, the project approach is viewed as empowering to children because they are active participants in shaping their own learning (Harris & Gleim 2008; Harte 2010; Helm & Katz 2011)

The project approach: A brief overview

The project approach seemed to be a good fit with my goal of finding a new way to engage and intrinsically motivate the children in my classroom, while meeting a wide range of needs. My research also suggested this approach would produce a well-organized curriculum that was straightforward to implement. The project approach involves children’s in-depth investigation of a worthwhile topic developed through authentic questions (Mitchell et al. 2009; Katz & Chard 2013). The teacher’s role is to support children through their inquiry. Teachers help children become responsible for their work, guide them to document and report their findings, and provide opportunities for choice (Katz & Chard 2013; Katz, Chard, & Kogen 2014).

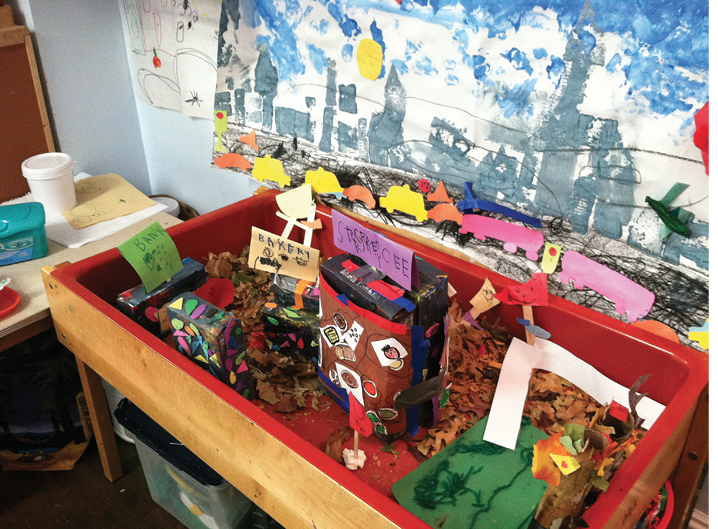

I was encouraged that the project approach uses a specific three-phase design, because this structure seemed compatible with my school’s culture. During phase one, selecting a topic , teachers build common experiences by talking with children about their personal experiences to determine interests and helping children articulate specific questions as a topic emerges (Mitchell et al. 2009; Yuen 2010; Helm & Katz 2011; Katz & Chard 2013).

Phase two, data collection , emphasizes meaningful hands-on experiences. Children are researchers, gaining new information as they collect data to answer their questions. This phase is the bulk of the project investigation and takes place through direct and authentic experiences such as field trips, events, and interviews with visiting experts (Harte 2010; Katz & Chard 2013). Children can also gather data through secondary sources, including books, photos, videos, and websites.

Phase three, the culminating event , is a time to conclude the experience, usually through a summarizing event or activity (Mitchell et al. 2009). The children’s role continues to be central and the class often holds discussions on what they have learned to create a plan to share their insights (Harte 2010).

Methodology and research design

After reading extensively about the project approach, I felt ready to implement it in my classroom.

Setting and participants

I conducted my study in a small private preschool on the Upper West Side in New York City. The school has a decades-long history in the neighborhood, and families have come to trust and love the educators there. The school’s traditional curricular model of teacher-driven, thematic-based learning is well established and, as far as I know, had not been previously challenged or adapted.

Study participants included 13 pre-K children, my two coteachers, and myself. The children had a diverse range of abilities. Seven children had significant sensory processing issues, two had severe cognitive and language delays, and four had mild language delays and/or mild sensory processing issues. Most children who enroll at the school can attend and participate independently, although some require one-on-one support with a therapist.

Data collection and analysis

Throughout the study, I collected and analyzed data through field notes, a reflective journal, children’s work, and anecdotal records that included photos, videos, and audio recordings. My primary source of data was field notes, which I used to provide a day-to-day recollection of how the project-based curriculum affected the children. The Teacher Notes app on the iPad and iPhone helped me collect and analyze the field notes. I kept project planning journals using a notebook and the Evernote app on my iPad. The software provided me with flexibility because it was accessible via iPad, iPhone, and computer; therefore, I was able to take ample notes and continually reflect upon my plans and implementation.

Helping children understand that they could find answers to their questions made a difference.

I collected work samples from the children—their writing, drawing, and artwork. The samples helped me assess children’s progress, and they became an additional source for documenting the growth in children’s participation throughout the project. Finally, I used videos, audio recordings, and photographs to document children in the process of working.

At least weekly, I read and reflected on my field notes to identify emerging themes. At least twice a week during prep time, I reflected on my Evernote journal to help with planning. Additionally, I continually reviewed and organized children’s work using Teacher Notes and listened to and watched audio and video recordings as they accrued, noting themes such as children using research terms or working independently to find answers to their questions.