- Screenwriting \e607

- Directing \e606

- Cinematography & Cameras \e605

- Editing & Post-Production \e602

- Documentary \e603

- Movies & TV \e60a

- Producing \e608

- Distribution & Marketing \e604

- Festivals & Events \e611

- Fundraising & Crowdfunding \e60f

- Sound & Music \e601

- Games & Transmedia \e60e

- Grants, Contests, & Awards \e60d

- Film School \e610

- Marketplace & Deals \e60b

- Off Topic \e609

- This Site \e600

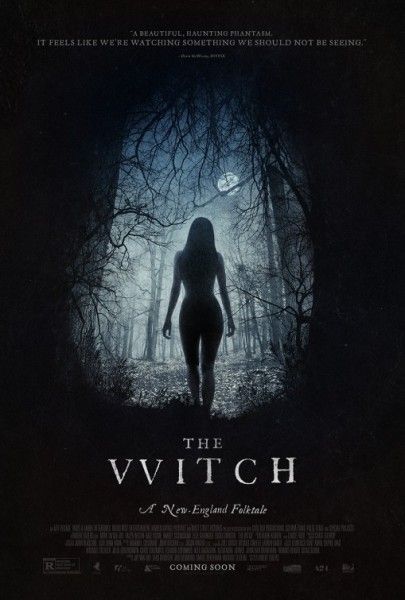

Watch: Why is 'The Witch' So Terrifying?

A new video essay showcases the art of dread and terror in 'the witch.'.

Among the many questions raised by Robert Eggers’ debut, The Witch , is this: what is it that makes a film terrifying? The easiest answer to this question would be "the general atmosphere," or, more vaguely speaking, "the mood." Or, simply, "it just felt scary."

The total effect here is that of indelible dread and terror.

As Chris Haydon so deftly points out in the below video essay, such an effect is created in a film because several components are working together in beyond-perfect harmony.

For starters, we have DP Jarin Blaschke’s stark, dramatic portrayals of the untamed colonial New England landscape. Dark forests and rolling plains complement each other in an unsettling way. As we watch small figures making their way through dense foliage or across vast fields, we empathize with them. We feel their loneliness, but beyond that, the fear—the sense that they have no idea what lies ahead, as each step they take leads them closer to what could be called the sublime, raging, wild, and tremendous heart of nature itself.

And then there’s Mark Korven’s soundtrack: violins steer us smoothly through the wildflowers and tall dry grasses at one moment and then jolt us out of our seats at another with their screaming crescendos. This further creates a sense that we humans—the viewers—are not in control here, and we will not be able to predict what comes next. Are there witches in the woods? Is young Thomasin’s baby brother, snatched from her one afternoon, still alive? What will be the fate of these settlers?

And then, last but certainly not least: the light. What is it about New England light? Blaschke has captured it here: the blazing, bright clarity of the days, unforgiving but also beautifully attentive to every last detail, even when the skies are overcast. And then the utter darkness of the nights, lit only by primitive fireplaces or lanterns. The total effect here is that of indelible dread and terror, and video essayist Haydon does an admirable job of showing us how that terror is built—and how it could be built in other films.

Sigma Announces the Powerful 28-105mm f/2.8 DG DN Art Zoom Lens

A look at the new sigma full-frame 28-105mm f/2.8 dg dn art lens, available for sony e and leica l mounts..

It’s turning out to be a great year for new lenses. We’ve seen some powerful new lenses from the likes of Sony , Fujinon , and Tamron , but we’re still excited to share the news of Sigma debuting a new full-frame 28-105mm f/2.8 DG DN Art zoom lens which is set to be available for Sony E and Leica L-mounts.

Let’s take a look at this newly announced zoom and explore its unique zoom range and how it could be a good pick for your event, travel, and on-the-run videography and photography needs.

The Sigma 28-105mm f/2.8 DG DN Art Lens

Designed to feature a vast zoom range and a fast constant aperture, the new 28-105mm f/2.8 DG DN Art Lens from Sigma is set to cover a variety of popular focal lengths. Shooters will be able to equip the lens to help them capture everything from sweeping landscapes to intimate portraits all with one lens.

Tailored for L-mount and E-mount full-frame mirrorless camera systems, this lens provides a minimum focusing distance of 15.8" across the entire zoom, ensuring your ability to capture detailed close-ups of your subjects.

The lens is driven by an HLA motor which should help it deliver quiet and precise autofocusing, and with its rounded 12-blade diaphragm you should be ensured to get pleasing and circular bokeh. This lens repels damage from outside elements by coupling a water- and oil-repellent front lens element coating with a dust- and splash-resistant design.

Price and Availability

The new Sigma 28-105mm f/2.8 DG DN Art Lens is currently available for pre-order, although we’re not sure when it should start shipping just yet. If you’d like to check it out though here are the specs and pre-order options:

- Full Frame | f/2.8 to f/22

- Fast Wide-to-Telephoto Zoom

- HLA Autofocus

- 15.8" Minimum Focus Distance

- Aperture Ring with Click & Lock Switches

- FLD, SLD, and Aspherical Elements

- Water and Oil-Repellant Coating

- Dust and Splash-Resistant Construction

Sigma 28-105mm f/2.8 DG DN Art Lens

www.bhphotovideo.com

Flexing a vast zoom range and a fast constant aperture, the 28-105mm f/2.8 DG DN Art Lens from Sigma covers a variety of popular focal lengths, equipping you to capture everything from sweeping landscapes to intimate portraits all with one lens.

The Ending of 'Shutter Island' Explained

The 'longlegs' ending explained, what are the best mystery movies of all time, turn your smartphone into an ai-powered micro-four-thirds camera, blackmagic camera for android 1.1 adds support for more phones, what is a texas switch and how can you use it in movies, launch into drone videography with dji’s tiny and affordable neo, 20 strong character traits to revitalize your writing, a conversation with 'art dealers' directors roy power and adam weiner, how to write great character descriptions.

Female Freedom and Fury in The Witch

The film’s director, Robert Eggers, discusses how his Puritan horror story came to focus on the empowerment of a teenage girl.

Robert Eggers’s debut film, The Witch , is made with all the assuredness of one who’s a veteran master of horror. Set in Puritan New England on the edge of civilization, it builds tension through a mix of period detail and supernatural bumps in the night, telling the story of a teenage girl, Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), and her family as they’re tormented by a supernatural presence in the woods. The Witch has been hailed by critics since its release last week, though the film’s scare factor has been much debated. But it’s the ending, particularly the resolution of Thomasin’s story, that distinguishes it from most traditional chillers, blending horror with an odd note of empowerment (spoilers ahead).

Recommended Reading

Say Goodbye to Your Manager

If Everyone Ate Beans Instead of Beef

What Menopause Does to Women’s Brains

Throughout the film, Thomasin’s family is picked off one by one until she’s the only one left (a particularly gory moment near the end sees her father William gored by the horns of a demonic goat named Black Phillip). She then signs herself over to the devil and joins a coven of witches dancing in the woods; the film closes on Thomasin levitating and laughing with delight. In an interview, Eggers said he didn’t initially approach his screenplay of The Witch as Thomasin’s story, but that he eventually realized she had to be the heart of the film.

The original draft was about how the titular witch manifested herself to different members of the family, meaning the film spent roughly equal time with everyone. “But through working on the second draft with my producers, Thomasin became the protagonist,” he said, adding that the film still works as an ensemble piece . In the story, the witch and her demonic partners take several forms: a goat, a raven, a rabbit, a beautiful woman, and a disfigured crone. While most of the other family members are besieged by these figures, Thomasin is targeted instead with suspicion from her parents and siblings, who come to think she’s in league with evil forces. “It was not my intention to make a story of female empowerment,” Egger said, “but I discovered in the writing that if you’re making a witch story, these are the issues that rise to the top.”

The director grew up in a rural New England town and was fascinated with the history of the witch-trial era from a young age. “I wanted to make an archetypal New England horror story, something that would feel like an inherited nightmare, a Puritan nightmare from the past,” he said. The film is, after all, subtitled A New England Folk-Tale , and seems to serve as an eerie warning from the era against being prideful and leaving the community, which is William’s original sin. “The Puritans believed that if you were part of ‘the elect,’ you could not be harmed by witchcraft,” Eggers said.

He tried to build The Witch around the Puritans’ psychology. A folk tale like this one wouldn’t have been seen during that time as an allegory, or a story told for broader social reasons. “It wouldn’t have been a yarn to keep people under control, just like the Ten Commandments wasn’t just a yarn to keep people under control,” he said. “All of this is ‘literal truth’ in the period.”

The Witch really does feel like it’s coming out of the past—much of the dialogue is lifted from historical record—and its characters approach the horrors of the woods in a period-appropriate way. Talk of witches isn’t mumbo-jumbo to be dismissed, but a very real fear associated with shame and guilt. “In these people’s minds, there’s no question of the supernatural,” Eggers said. “When William is upset about Katherine bringing up the idea of a witch, it’s less that he doesn’t believe a witch is possible, and more that his pride has been hurt.”

The film’s exploration of patriarchal power was the key to unlocking Thomasin’s story. As a woman in the 17th century, she’s entirely stripped of agency. She exists only to work and help her family, and eventually be married off and bear more children. As The Witch progresses, it becomes clear that the campaign being waged against her family is targeted at freeing her so that she can join the coven in the woods. The idea that she’s been liberated is an intentionally muddy one—when she submits to Satan near the end of the film, he takes the form of a man—but there’s a giddy sense nonetheless that she has triumphed.

When asked about The Witch ’s deeper commentary at a press conference, the actress Anya Taylor-Joy said she thought the film had a “happy” ending—because joining the coven is the first choice Thomasin gets to make on her own. Eggers is careful to communicate the darkness of Thomasin’s coercion, but doesn’t shy away from the fact that she’s leaving a repressive society behind. When he started thinking about The Witch , his focus was on the unknown, on “understanding where all this stuff comes from, the origins of the clichés—how they’re powerful, how they’re part of everyday life.” But he’s surprised and happy with the way his story evolved, and how it can speak to important modern issues despite being set centuries ago. Thomasin and The Witch seem destined to enter the great canon of horror films that includes the likes of Carrie , The Descent , and A Nightmare on Elm Street: stories that terrify by tapping into the immense power and fury of isolated women.

About the Author

More Stories

How M. Night Shyamalan Came Back From the Dead

Want to See a Snake Eat Its Tail?

“The Witch,” a period drama/horror film by first-time writer/director Robert Eggers , tellingly advertises itself as “a New England folktale” instead of a fairy tale. Fairy tales are, at heart, parables that prescribe moral values. “The Witch,” a feminist narrative that focuses on an American colonial family as they undergo what seems to be an otherworldly curse, is more like a sermon. Sermons pose questions that use pointedly allegorical symbols to make us reconsider our lives, just as one character uses the Book of Job to understand her role in her family (more on Job shortly). But “The Witch” is not a morality play in a traditional sense. It’s an ensemble drama about a faithless family on the verge of self-destruction. And it is about women, and the patriarchal stresses that lead to their disenfranchisement.

For a while, it is unclear which character is exactly the focus of “The Witch.” It’s probably not grieving mother Katherine ( Kate Dickie ), though Eggers gives ample consideration to her mourning of infant son Samuel, who has disappeared under unusual circumstances. And it’s definitely not Katherine’s mischievous young twins Jonas and Mercy ( Lucas Dawson and Ellie Grainger , respectively), though Mercy does often speak for her and her brother’s inability to understand how the world works after their family is banished to a foreboding forest by a nearby colony. The film’s main protagonist might be William ( Ralph Ineson ), Katherine’s troubled husband. Or it could be her eldest son Caleb ( Harvey Scrimshaw ), a young man desperate to defend his father from his mother’s frustration.

But more often than not, “The Witch” concerns Thomasin ( Anya Taylor-Joy ), the eldest of Katherine and William’s five children. Thomasin undergoes puberty under the mistrustful eyes of her family, but realistically, they’re not too concerned with her when crops are failing, money is scarce, and Samuel is missing. Still, Thomasin absorbs the brunt of her family’s anxieties: her younger siblings look to her for comfort, but she balks at the added pressure, especially after her mother makes her do more chores than the rest of her family members. There are other subplots in “The Witch,” but all roads eventually lead to Thomasin. That’s the dark beauty of Eggers’s expansive story: it’s not just about the marginalized presence of women in a male-dominated microcosm, but the harsh conditions that can, even under extremely isolated circumstances, lead women to resentment, and crippling self-doubt.

“The Witch” is, in that sense, an anti-parable. Eggers eventually leads Thomasin out of the woods, but he takes his time in clearing her path. The result sometimes feels like an imaginary Harold Pinter-scripted version of “ The Crucible ,” since it follows desperate, lonely souls who do everything—set animal traps, milk goats, till the fields, do laundry—to avoid thinking about what’s really troubling them. It takes a while for Thomasin’s clan to even consider that their problems are caused by witch, or demonic enchantment. But it eventually happens. Before that, there are only signs and portents, particularly evil-looking animals: a tetchy goat, a twitchy hare, and some talkative crows. Eventually, Thomasin’s family personify their fears of nature, a gnawing uncertainty that is predictably gendered as feminine. And suddenly, the family’s day-to-day troubles—almost all of which stem from the fact that their land seems cursed—takes the form of a fairy tale witch.

Which brings us back to Job. In the Book of Job, God hurts Job in order to test his faith. The reader knows that God exists, and has a divine, or perhaps just Mysterious, reason for trying Job. But until Job’s body is plagued by God, he doesn’t question that there is a reason for his torment. The same is basically true of William and his family. Until events lead his family to start clawing at each other’s throats, he goes about his business as best he can. As a result, when you watch “The Witch,” you often don’t seem to know what the film is about. But the film’s title is a big clue: this is a fantasy about empowerment, albeit through unorthodox methods.

I’ve talked a lot about what “The Witch” is about without mentioning how well it’s about it. That’s partly because the film is so consistently engrossing that I surrendered to it early on. Eggers’ hyper-mannered camerawork draws you in by evoking Johannes Vermeer’s portraits and the landscape paintings of Andrew Wyeth (there’s also an overt reference to one of Francisco Goya’s more famous paintings, but I can’t tell you which one for fear of ruining a surprise). The complex sound design and controlled editing also help establish a mood that is (paradoxically) both inviting and somber. “The Witch” draws you in so well that you won’t realize its creators have been broadcasting exactly where they’re taking you.

Simon Abrams

Simon Abrams is a native New Yorker and freelance film critic whose work has been featured in The New York Times , Vanity Fair , The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

- Lucas Dawson as Jonas

- Ralph Ineson as William

- Harvey Scrimshaw as Caleb

- Ellie Grainger as Mercy

- Anya Taylor-Joy as Thomasin

- Kate Dickie as Katherine

Cinematographer

- Jarin Blaschke

- Louise Ford

- Mark Korven

- Robert Eggers

Leave a comment

Now playing.

The Front Room

Matt and Mara

The Thicket

The Mother of All Lies

The Paragon

My First Film

Don’t Turn Out the Lights

I’ll Be Right There

The Greatest of All Time

The Substance

His Three Daughters

Latest articles.

Wrapping Up My Experiences at the 2024 Telluride Film Festival

Peacock’s “Fight Night” Largely Entertains But Pulls A Few Punches

Telluride Film Festival 2024: Memoir of a Snail, Better Man, The White House Effect

Telluride Film Festival 2024: Blink, Apocalypse in the Tropics, Carville: Winning is Everything, Stupid!

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

- Editorial Boards

- Guest Editors

- Schools & Mentors

- Privacy Policy

- Style Guide & Forms

- Back Issues

- Masoud Yazdani Award

- John Pruitt Archive

- Criterion^3

- Cucalorus x Film Matters

The Witch (2015). Reviewed by Chris Dymond

The Witch (A24, 2015)

The Witch is not so much horrifying in its visual content as it is in its evocative ability to convincingly bring forth a historic space in which the ideology of the American frontier percolates so violently with the Western concept of the religious sublime. Steeped in its historical parlance and rigor, The Witch brings one to the epistemic environment of intense anxiety in which such terrifying potentialities could have been brought into common existence. Because of this, The Witch is unflinching, albeit heavy-handed, in its desire to posit such an encounter of rampant ideologies as the root cause of the horrific intracultural and intra-familial violence that took place amongst the early moments of North America’s colonization. It is firstly sincere, therefore, in its attention to historic detail. However, progressively, this sincerity extends to the emotional, corporeal, and moral anxieties that beset such a historical period. The Witch follows William (Ralph Ineson), Katherine (Kate Dickie), and their children Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), the twins Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and Jonas (Lucas Dawson), as well as their infant child Samuel (Athan Conrad Dube), as they are plunged into isolation following William’s exile from their seventeenth-century New England Puritan settlement after his rejection of the Church’s diluted interpretation of scripture. Despite such condemnation, the family vigorously set forth, breaking ground at the forest’s edge whilst vowing to “conquer this wilderness.” However, they are immediately tormented by horrors that threaten not only their physical existence, but their ardent piety.

William and Katherine’s children begin to disappear and perish, falling prey to what they believe to be a woodland witch. This tears the familial unit apart, and Katherine and William seem to grow afeared of Thomasin as they believe her to be in league with the Devil. After Caleb’s violent death, William seals Thomasin, Jonas, and Mercy inside their goat-pen. He awakes in the morning to find Thomasin drenched in blood and surrounded by the bodies of goats whilst the young fraternal twins are nowhere to be seen. As he stands in shock, he is gored to death by Black Phillip, the ram upon the farm, and as Katherine emerges from the meager house, charging Thomasin in anger and disgust, she is killed by Thomasin in self-defense. Distraught and desperate, Thomasin attempts to speak to Black Phillip as she believes him to be the conduit of Satan. A cloaked man appears and whispers in response, instructing Thomasin to sign her name within his book. As she does, she is led into the woods with Black Phillip following closely behind.

Such a terrible series of events begins when the dogmatic realities of William and Kate, though stoic and unflinching in faith, are pierced and rendered unstable as Samuel, their newborn son, impossibly disappears during a game of peekaboo with Thomasin. The only thing, we later learn, that could have stolen Samuel away is the witch residing in the woods beside the farmstead. As the secluded family attempt to rationalize the disappearance of Samuel, repeatedly suggesting that he was snatched by an opportunistic wolf, the reverberating presence of the witch seems to infiltrate all of their waking and unconscious hours. Even the “Godly land” of the farmstead seems repulsed by the witch’s presence. William’s crop of corn fails, succumbing to what we can assume to be the condemning rot of ergot: the infection of corn which turns the grain into a potent psychedelic hallucinogen as well as a deadly pathogen once imbibed, and which is precariously accepted as the precursor for the pervasive witch trials that occurred throughout seventeenth and eighteenth-century New England.

Jonas and Mercy, the young fraternal twins, are also seen to reciprocally converse with the he-goat known as Black Phillip; he who gradually assumes the guise of the conduit of Satan. Alongside this quivering presumption, and in response to potential starvation, the young Caleb ventures into the woods in search of game. Alone and afeared, he is lured into the embrace of the woodland witch as she appears youthful and pristine. Caleb returns that eve with lacerations upon his body, lingering on the verge of consciousness. He dies the following day, belching forth a rotten apple from his esophagus, after proclaiming his love for Jesus whilst his family pray vehemently at the side of his bed. The violent death of Caleb only acts to exacerbate the family’s internal sundering. Satan, “the wicked one,” is now not just seen in Black Phillip; he is seen in Thomasin, the infantile twins, and the lingering shadows about the forest edge.

These oscillating anxieties of The Witch are not simply communicated narratively, however, but cinematically. The camera continually moves fluidly throughout the profilmic world, visualizing cinematic space through the distinctly nonhuman apparatus of the Steadicam. The free-moving nonhuman camera, as it resists the desire to be situated within the body of any one character, therefore suggests the existence of an external being, though one who is continually present in the diegesis. Such a modality of the camera draws us not only to the isolation of The Witch ’s characters, as we are not allowed to subjectively become a part of their individual worlds, but also to the existence of other proximal beings existing intimately.

Alongside such an anxious visuality, the audible soundscape of The Witch operates along a similar dialectic. In achieving this, The Witch ‘s audioscape becomes less a cinematic soundtrack than the Nietzschean musicality of tragedy. The orchestral cacophony of wailing women that becomes the motif of the forest brings us repeatedly to Nietzsche’s notion of the affects of that music which is Dionysian in intent: formless and fervent without recourse to structured language, giving away instead to audible abandon. The presence of such a Dionysian soundscape, occurring firstly when the camera captures the sublime expanse of the forest, finds its textual anchor in the closing sequence of The Witch where a coven of witches maniacally gesticulates amongst the boughs of the midnight forest.

Inherently, though, the attraction of The Witch is drawn from its existence within the somewhat catch-all genre of horror. However, though we are presented with horrific images in Samuel’s death, or Katherine’s descent into madness, it is the ways in which these images interact with the palpable presence of anxiety that slithers its way across the bodies of humans and throughout the recesses of the woods that gives rise to the umbrous specter of fear and revulsion.

It is this thought that turns me back to my opening statement: The Witch is not so horrible in its surface content, but in its ability to eloquently present the intertwined ideologies that gave rise to such events within a historic environment. Though greatly disturbing, the horror of The Witch is not truly felt in the flaccid body of the decrepit woodland woman, but in those moments where father strikes daughter, or daughter murders mother, because the perceptible though impossible presence of Satan is seen within their tainted souls. This historio-religious anxiety is also experienced in those moments where the camera frames the nonhuman forest as if it was a singular being capable of outward communication. We repeatedly look upon that distinctly sublime face of nature as William does; though, where William sees God amongst the trees, we see Satan.

Therefore, The Witch , through its reserved claims to history, lets us glimpse and comprehend those physical and mental movements that brought people into contact with those beings they called either God or Satan. As such The Witch , as we closely shadow the Puritanical family through their personal piety to their epistemic collapse, brings us to, and immerses us in, that environment where fear and terror truly begin.

Author Biography

Chris Dymond is a student at Queen Mary University of London. He greatly admires those individuals that made up the second-wave of American Avant-Garde film, as well as those who became the North American Structural/Materialists.

Film Details

The Witch (2015) USA Director Robert Eggers Runtime 93 minutes

- Search for:

Film Matters Links

- Film Matters @ Intellect

- Film Matters @ Intellect Discover

- Film Matters on Facebook

- Film Matters on Vimeo

- Film Matters on YouTube

- Sample issue of Film Matters

Undergraduate Research Opportunities

- Council on Undergraduate Research

- SCMS Undergraduate Hub

Related Links

- Avant-Garde Film Index

- Caméra Stylo

- Cinemablography

- Diegesis: Film & Television Magazine

- Film Bureau

- Film International

- Global Cinemas Resource

- Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Recent Posts

- Leandra Djomo, Author of FM 14.3 (2023) Article “Daydreaming: An Exposé on VR Technology as a Form of Digital Escapism and Identity Design”

- FM 14.3 (2023) TOC Highlights

- Interview with Filmmaker Kim Carr. By Kim Carr and Sophia Fuller

- A. G. Lawler, Author of FM 14.2 (2023) Article “‘Films for Humanity’: De-victimization of the Female in At Five in the Afternoon and The Milk of Sorrow”

- Johanna Carter, Author of FM 14.2 (2023) Article “Translating a Monster: Motherhood and Horror Criteria in Ringu and The Ring”

- Citation Ethics

- Mise-en-Scene

- My Film Festivals

- New York Film Festival

- Press Releases

- Telluride Horror Show

- The Film Essay

- Videographic

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A father and his son, a boy of twelve or so, go into a wood. They are out hunting, armed with a gun. As they walk, they engage in one of those ordinary, man-to-man chats that arise on a country stroll. “Canst thou tell me what thy corrupt nature is?” the father asks. “My corrupt nature is empty of grace, bent unto sin, only unto sin, and that continually,” the lad replies. Clearly, he has learned the words by rote, yet they don’t sound tired or hollow in his mouth; he means them. His next task is to help with the traps that have been laid in the undergrowth. We watch his small hands slowly easing wide the iron jaws.

These scenes are from “The Witch,” a film written and directed by Robert Eggers. The father is William (Ralph Ineson), who is tall and roughly bearded, with a hatchet face. Indeed, there is something axelike in his demeanor, and he seems most elemental—most true to his own hard-hewn being—when stripped to the waist and savagely splitting logs. He would make a good executioner. The boy is Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), who looks solid enough, though a flame of fear burns in his eyes. William is married to Katherine (Kate Dickie), and they have four other children: an older daughter, the radiant Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy); twins, Mercy (Ellie Grainger) and Jonas (Lucas Dawson), young and mischievous; and a baby named Samuel. He is tended to, one day, by Thomasin, who plays peekaboo for his delight, in the open air. Three times she covers and uncovers her eyes, and he laughs. The fourth time she uncovers them, he is gone.

The film, bearing the subtitle “A New-England Folktale,” is set around 1630, meaning that William and Katherine, whose heavy accents betray their roots in the North of England, belong to the early generation of settlers. This particular family, though, has been doubly exiled—first across the ocean, and then from the fortified village where they used to reside. In the opening scene, William is brought before a council of his fellow-citizens and accused of “prideful conceit.” What exactly that entails we never know, and he claims to have practiced only “the pure and faithful dispensation of the Gospels,” but the outcome is harsh: he and his kin are banished, with all their possessions piled on a cart. The wilderness awaits.

The rest of the action takes place on the verge of a forest: the classic habitation of a fairy tale. That is where William, Katherine, and their children build a home and try to forge a life, with the dense gloom rustling beside them. When Samuel is snatched, we see him—or think we see him, in a glimpse—being carried through the trees by a scuttling figure, caped in red. We are meant to recall not just the Brothers Grimm but Nicolas Roeg’s “Don’t Look Now” (1973), in which the alleyways of Venice were prowled by a similar scarlet fiend. What occurs, after the abduction, is the first of many terrible rites: a female form, naked and unnamed, pounding at something within the rotten trunk of a tree, like an apothecary with a mortar and pestle, and smearing herself with gore.

What is going on here? And is it going on at all? Could we be observing not facts but the fanciful terrors of the devout? The film is certainly stuffed with devilry, and Eggers is not shy of familiar tropes. The family keeps goats, for instance—a white one whose udders spurt blood into a pail when Thomasin milks her, and a villainous brute called Black Phillip, whom the twins both taunt and conspire with in their chanted nursery rhymes. He’s a dead ringer for the billy on the inner sleeve of the Rolling Stones’ “Goats Head Soup,” and Eggers holds him in such careful closeup that his muzzle is blurred while his mad and staring eye remains in focus. As a rule, keep clear of his horns. The question of whether he is the Prince of Darkness or merely a farmyard pest, however, stays unresolved, and “The Witch” feels at once sticky with tangible detail and numinous with suggestion. Katherine dreams of a raven pecking at her breast, in a parody of a suckling child, but when she wakes in the morning there really is a bloodstain on her shift.

Viewers who grew up with the “Scream” franchise, or with the toothless array of “Saw” films, will doubtless fidget and sigh at such ambivalence. They will rightly ask if “The Witch” even deserves to be called a horror flick. Well, it sounds like one; the composer of the score, Mark Korven, doesn’t hold back on the shriek of strings, beefed up by a choir of rising moans. Also, there are just enough jumps to rattle your popcorn. I knew that something was afoot as Caleb approached a mossy hut in the woods, but I didn’t expect an actual foot, bare and tempting, to appear on the threshold. Yet the film is thoroughly stripped of the sniggering ironies that beset, and often wreck, the modern fright fest. You can laugh at the archaism of the dialogue, if you wish, though I happen to like its sturdy lyricism. (“Thou shalt be home by candle-time tomorrow.”) More important, there is no silliness to undercut the menace—nothing to let you off the hook of having to think about these folk, about the leathery toughness of their existence, and about the load that their souls are forced to bear. You believe in their belief.

This is, to put it mildly, an uncommon state of affairs for anyone who frequents the cinema, the theatre, or the opera house. How many people, these days, heading out of “Don Giovanni,” are honestly shaken by the mortal terror of the hero, in his final conflagration? Which of us treats “The Crucible,” set sixty years or so after the events of “The Witch,” as anything but a reflection on the political hysteria of the time in which it was written? The problem is simple: we can’t be damned. One gradual effect of the Enlightenment was to tamp down the fires of Hell and sweep away the ashes, allowing us to bask in the rational coolness that ensued. But the loss—to the dramatic imagination, at any rate—has been immense. If your characters are convinced that a single action, a word out of place, or even a stray thought brings not bodily risk but an eternity of pain, your story will be charged with illimitable dread. No thriller, however tense, can promise half as much.

That is what Eggers is striving for in “The Witch.” It’s the first feature that he has directed; hitherto, he has worked as a production and costume designer, and the legacy shows in the weave of the homespun clothes. The twins are swaddled like dolls, thus acquiring an extra layer of creepiness, and the colors of the outfits, matching the umbers and grays of the landscape, turn any glint of red into an explosion. But period dress is nothing unless shrouded in period emotions—in the qualms and the ragged jitters of the age. That is why we see Caleb, on the brink of puberty, casting sly glances at the swell of his sister’s bosom; incestuous guilt is enough to persuade the poor sap that he is, in the deepest sense, bewitched. Indeed, each person thinks that he or she is responsible for the loss of Samuel, and for the dire events that follow. The entire film is crafted as a kind of spiritual whodunnit. Katherine is afraid that her baby, as yet unbaptized, will be among the lost, denied entrance to Heaven, while William, his authority flaking and peeling away with every scene, admits out loud to being a thief.

And what did he steal? A silver wine cup. Time and again, Eggers adds hints of the Biblical, to thicken the air of piety that these people breathe. One of them, in the wake of a spell, vomits up a whole apple, shiny and intact. When they pray, they are planted squarely in the frame, and viewed either from behind, kneeling on the ground with their hands conjoined and upraised, or head on, at table, as in the Last Supper, with William saying grace. Thomasin, alone, confesses to the Almighty, “I have, in secret, played upon thy Sabbath,” compelling us to wonder what her games consist of and whether they count as play.

Taylor-Joy is remarkable in the role, her wide-eyed innocence entwined with a thread of cunning—proof either of her quick wits, scarcely unusual in a clever and curious girl, or of some fell purpose. One night, in Black Phillip’s stall, we hear a low whisper of temptation in her ear: “Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?” it asks. “To see the world?” There is surely no chance that she—or we, for that matter, even now—could refuse that proposition. And so “The Witch” hastens to its harrowing climax, about which, I predict, you will want to rage deliciously. It borrows from Goya, an artist in his element with demons, and I cannot decide if the sequence unbalances the ambitions of “The Witch” or brings them to full and flamboyant bloom. But this is a scary movie and a serious one, because it lures us into the minds, and the earthly domains, of those who are themselves scared, night and day, that they have forfeited the mercies of God. It takes an original movie to remind us of original sin. ♦

'The Witch' Review: One of the Scariest Horror Films in Years

Your changes have been saved

Email is sent

Email has already been sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

'The Equalizer's Denzel Washington May Claim Another Prestigious Title

The 10 best war movies that are perfectly directed, ranked, this guillermo del toro-produced horror mixed hitchcock with giallo for 90% on rotten tomatoes.

A good horror film isn’t terribly easy to create. Sure, you can make audiences jump with loud noises or the sudden appearance of a character, or you can make them long to find out the rest of the mythology behind a particular bad guy/book/object of questionable mystic qualities before all curiosity falls away once it’s revealed. But it’s tough to craft something in the genre that stays with people once they’ve left the theater. With writer/director Robert Eggers ’ feature film debut, The Witch , however, that rare, memorable and affecting horror film has arisen. Opting for dread and mood over jump scares or deep mythology, Eggers delivers a seriously terrifying and deeply unsettling “New England folktale” set in colonial America that is intensely disturbing and wholly unforgettable.

Set in 1630 New England, a generation before the Salem witch trials, the film revolves around a small family that has been excommunicated from its plantation due to father William’s ( Ralph Ineson ) outspoken objections to what he sees as the community’s lax religious principles. William welcomes the chance to leave the plantation and practice his strict adherence to the Lord on his own, moving his family to a remote cabin near the foreboding woods.

Early in the story, daughter Thomasin ( Anya Taylor-Joy )—verging on becoming a woman herself—is playing peek-a-boo with the family’s baby near the treeline when, all of a sudden, she opens her eyes to see the boy is gone, with no trace of where he went. The audience is then introduced to a cloaked figure running with the baby through the woods—the titular witch—and what happens next is unspeakable. Suffice it to say, Eggers conjures the film's physical antagonist in such a way that you’re left both wanting to see more of her and never wanting to see the character again.

What follows is the crux of the film’s conflict: the family struggles with the disappearance of the child while attempting to maintain their faith in God in light of such a tragedy. Moreover, things keep getting worse, as their harvest of corn goes bust and, without the safety of the plantation, the family is in danger of starving to death during the winter.

The faith of the individual family members—which also includes mother Katherine ( Kate Dickie ), pre-teen son Caleb ( Harvey Scrimshaw ), and two young, rambunctious twins Jonas ( Lucas Dawson ) and Mercy ( Ellie Grainger )—alternatively wavers and stays strong as they question original sin, the afterlife fate of the young baby, and whether they themselves have been redeemed in the eyes of God. Is it possible to go to heaven if you’ve sinned? Can we know for sure that God forgives? What does it mean to invite sin into your life, and what do those consequences look like? These questions are pondered by the individuals of the family, namely Thomasin, William, and Caleb, and begin to weigh on their hearts, turning their tension and doubt on each other. Someone must be to blame for their poor fortune, and if not God, it’s surely one of them.

And throughout all of this, there’s the encroaching dread of the witch, which the family may or may not believe exists. Instead of crafting a villain whose face the audience comes to see as familiar and iconic, Eggers knows that the true power in this kind of film is what you don’t show. The audience is constantly left in question of just exactly what the witch looks like, and at the same time the brief glances we do get are absolutely chilling. This tease of just enough but not too much is executed to perfection, which not only increases the tension surrounding the witch herself, but keeps the story’s main focus on the family. The key to The Witch is that Eggers deals in dread, not scares. Aided by a striking score from Mark Korven that owes a debt to Stanley Kubrick ’s The Shining (many times a shot will linger just a little too long as the music grows louder and louder, becoming more and more terrifying), the audience is constantly watching in trepidation, not sure where the film will go next. Jarin Blaschke ’s bleak yet hauntingly beautiful cinematography adds yet another layer to the film’s atmosphere, fully engrossing the audience into the secluded, colonial setting. And the performances, especially young Taylor-Joy, are quite effective, selling the sense of isolation, regret, and deep-seated tension amongst one another.

The movie does deflate a little bit in the middle section, which drags a tad as dread gives way to despair and the inner turmoil of the remaining family becomes somewhat monotonous. For a moment it seems like The Witch is poised to switch its focus to becoming a sort of prequel to the Salem witch trials (some of the dialogue was pulled straight from Salem-era journals), but then Eggers delivers a third act that, quite simply, scared the living hell out of me and will be ingrained in my mind for a very long time. Brain, meet nightmare fuel. While the horror genre has never really lost its prevalence over the years, it feels like a lot of “scary” movies these days are simply going through the motions, offering up the cinematic equivalent of junk food—it may taste good in the moment, but it’s not necessarily fulfilling or all that memorable. The Witch is not only an incredibly well-crafted horror film, it’s a good movie period. Eggers announces himself as a talented filmmaker to watch, with a knack for blending genre elements with larger, more thoughtful questions, which in the case of The Witch consider sin and inherent goodness. That the film will most likely find you wanting to watch with one hand covering your face is just a bonus.

- Kate Dickie

April 1, 2022 By Meg Shields

Screams and Sirens: Appreciating the Sound Design of Robert Eggers

*the persistent foghorn wails*

October 20, 2019 By Kieran Fisher

How Robert Eggers Brings the Past to Life Onscreen

With ‘The Northmen,’ the director of ‘The Witch’ and ‘The Lighthouse’ will go back in time once again.

September 30, 2019 By Mary Beth McAndrews

The History and Transformation of the Final Girl

The trope carries implications of strength, perseverance, and resilience. But where did the Final Girl come from, and how has she changed?

June 21, 2019 By Julia Teti

The Devil is in the Details in Robert Eggers’ ‘The Witch’

Meshing historic milieu with fear of the female body, Eggers incites a horror spectacle with a contemporary reading.

December 6, 2018 By Sheryl Oh

How Cinematic Purpose Can Fuel Women to Kick Ass

Watch this video essay highlighting the power of stories to explicate meaning in our daily lives beyond self-preservation.

November 9, 2018 By Jacob Trussell

What’s Inside Robert Eggers’ ‘The Lighthouse’

No matter what, we’re hoping for major ‘The Fog’ vibes.

October 17, 2018 By Siobhan Spera

The Three Types of Feminine Monsters

Watch a video essay that sheds light on how feminine monsters perpetuate society’s age-old fears about women.

'The Witch' Isn't a Horror Flick—It's a High-Powered Feminist Manifesto

Find your coven—and yourself.

The real horror in Robert Eggers' new film The Witch: A New England Folktale isn't satanic goats, baby abduction, or even nefarious witches in the woods—it's the limited and punishing road to womanhood.

Welcome to 1630 New England, where our coming-of-age heroine, Thomasin, is coming face-to-face with puritanical gender roles, and her culture's vilification of women who break ranks. The movie, which opened last month to critical acclaim and has made $22 million at the box office, turns these suffocating circumstances on their head. Instead, it uses them to show us how much Thomasin, a girl who is eventually (spoiler alert, in case you hadn't already guessed) brave enough to seek autonomy, stands to gain by taking the other, more transgressive role for women. She chooses to be a witch, the most reviled manifestation of womanhood—and she's all the better for it.

The real horror in Robert Eggers' new film The Witch is the limited and punishing road to womanhood.

When we meet Thomasin, her family is being exiled from their community and forced to settle in a geographically and emotionally remote place. At the time, trade was the only means of attaining food and goods that you could not make or grow yourself—and trade relied on trust and social ties. It's understandable that Thomasin's parents then agonize over their new circumstances: crops aren't coming in, money is scarce, hunting is touch and go, they have five children to feed, and they're outcasts from society. Economizing their eldest daughter through traditional marriage is the logical next step. Thomasin's family is all too willing to take her to town and marry her off to whomever will house her.

This tension between the domestic home and independence is clear from the get-go. We first see Thomasin as a girl staring into the woods, returning again and again to gaze into the wilderness each time she's scolded for failing at the endless string of household tasks she is assigned. If church and the nuclear family unit are the foundation on which puritan life was built, the woods represent everything that's dangerous, disorderly, and sinful. Thomasin wants a life beyond the boundaries of the home—the limited and prescribed life that she, as a woman, can look forward to leading.

Thomasin and her brother Caleb

To be a wife and mother was the only acceptable life for a puritan woman. Keep in mind that the very idea of personal freedom would have been a questionable concept to the puritan people. The Calvinist religion, to which Thomasin and her family subscribe, dictates that god predetermines a person's fate—even your own fortune in the afterlife was not under your control. In this historical context, autonomy for women is not only reviled—its maligned. We see that being "a witch," like being a feminist, is just another term for believing in self-determination.

That women were unholy by nature—and had to be anchored by marriage and family—was a common theme in the New England witch trials. In the 1600s, transgressive women were those who failed to satisfy the two most important traits for a female: to be godly and to be a mother. Defying these roles often manifests in folklore's most frequent female archetypes: the woman in red and the crone. Red, the color of lust and menstrual blood, is a symbol of sexuality and coming-of-age, while the crone is the withered fate of a woman outside of the traditional family unit. In The Witch , we are visited by both.

We see that being "a witch," like being a feminist, is just another term for believing in self-determination.

The crone—nude, cackling gruesomely, and bathed in blood—materializes throughout The Witch . First, when Thomasin's baby brother, whom she fails to watch closely, suddenly disappears. Though the family initially blames a wolf, we know better. Later, we see a woman out of focus clad in nothing but the evidence of baby Sam's brutal carnage.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

The Witch then introduces us to another symbol of the transgressive female: the sexually independent woman. When Thomasin's brother, Caleb, gets lost in the woods, he's greeted by an unfamiliar, buxom woman draped in a red cloak. We're already aware of Caleb's approaching sexual maturation when we catch him eyeing his sister's barely-revealed neckline. When he returns from a tryst with the woman in red, nude and exhausted, his transgression is completely overlooked. Instead, he turns the family's attention to Thomasin, crying out "Her nether-parts, she sends them upon me!" He then prays to God in an orgasmic fashion, purifying his soul before suddenly dying. It's here that Thomasin's family becomes convinced that she is the witch who has been terrorizing their family with her wanton wickedness (or just, you know, wanting a life beyond the home).

A post shared by The Witch (@thewitchmovie) A photo posted by on

With her parents now determined to reject her, Thomasin finally rejects them: She defends herself against their physical attacks and executes both a literal and metaphoric assault on the traditional family unit, freeing herself from society. Following the family goat into the woods, she joins a circle of similarly naked, blood-soaked women. Her eyes become wide with wonder, then laughter, and finally levitation.

The Witch may present like a highbrow horror film, but it delivers a powerful feminist message: She's now a woman, with the awesome power to determine her own life.

Follow Marie Claire on Instagram for the latest celeb news, pretty pics, funny stuff, and an insider POV.

First day snapshots have never been more royal.

By Kristin Contino Published 4 September 24

The Kansas City Chiefs star also opened up about his memorable “Eras Tour” cameo.

By Danielle Campoamor Published 4 September 24

Three divisive trends all in one look.

By India Roby Published 4 September 24

Zoë Kravitz's directorial debut doesn't provide the nuance needed to move the conversation forward.

By Sadie Bell Published 4 September 24

Talk about snubs.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published 30 August 24

If you thought you weren't a science-fiction fan, think again.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published 26 August 24

There's more to these blockbusters than fight scenes and superheroes.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published 21 August 24

Consider your to-read list and your watch list full.

By Andrea Park Published 19 August 24

It's not cheating at trivia, but JLC is also an expert at that...

By Quinci LeGardye Published 9 August 24

Filmmaker Sean Wang breaks down how he created a must-see coming-of-age film set in the '00s.

By Sadie Bell Published 9 August 24

The superstar herself teased the news today.

By Quinci LeGardye Published 1 August 24

- Contact Future's experts

- Advertise Online

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

Marie Claire is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

The Witch centers on a 17th-century family who believes they're being cursed by a witch.

Plotting Harm. The Conjuring, Under The Skin , Green Room, The Babadook, It Follows. The Witch belongs on this list because it's one of the best modern horror films, a must-see movie, and a theater-worthy experience. What these films have in common is their ability to surprise audiences, their ingenuity, resourcefulness, and the clever blend of influence and originality. With The Witch, the influence, while not overly obvious, is surely there. From Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) to Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009), The Witch is a fascinating culmination of the familiar and the new. Where we believe a film titled The Witch will take us is met instead by something far more sinister. It’s a mature film with large ambitions, a small budget, an inexperienced director, and a lot of talent. The final product has embedded images and sounds into my memory; lingering moments that both frightened and confused me. It even led to a little educational reading and research into who Robert Eggers is and why I hadn’t known about him before. To say that The Witch is perfect would be unfair as it does have its downsides. But they are outweighed by so much good that they're hardly worth mentioning. What is fair to say is that The Witch is a film that deserves its attention, praise, and recommendation.

Satan’s Church. The film creates a tone that is undeniably heavy and dreadful from the very first scene. Our characters don’t live on a pleasant little farm outside the woods. They live on a misty, foggy patch of wet, colorless land with a traditionally haunted-looking forest looming just yards away. The general feel of the film (the sights and sounds) goes a long way to set the stage tonally, but it’s worth noting that the photography compliments it perfectly. The camera creeps slowly, it uncomfortably exposes events in low light and heavy shadow. This obscures your initial understanding and helps bring you to terrifying realizations. It often establishes the landscape in a grim yet picturesque fashion. What we know is limited to what we can see, and in that style of filmmaking, The Witch shines. The unsettling music and use of dramatic sound help reiterate the dangers and inevitability of something unexplainable, but present. The uncertainty the film creates, with limited information, clean photography, and editing, and with solid writing, help pull the audience into the world of madness. Its talent may be too great, however, as the audience might find it difficult to escape that world very easily.

The Real Curse. Despite the well-constructed atmosphere and all the noteworthy things the film does, there are a few negatives that should be addressed. The major issue I had with the film was the use of jump scares. While jump scares have long been known as a cheap imitation of genuine horror, the positive spin that could be put on them in this film is that they aren’t built up predictably. There aren’t moments where the film becomes dead silent, where we see a character quietly breathing in a panicked hush, only for the audience to be “scared” by a loud noise or a fast image. Instead, these moments happen a bit more organically and out of the blue. There is no reason to expect them, but once they happen it’s hard not to feel cheated. Especially since the film already does such a good job of creating an authentically unnerving tone and setting, shows the audience such unsettling images, and tells such a shocking story. It begs the question: why are jump scares in movies? With only a few exceptions, most notably in The Thing , jump scares seem inorganic and can never be relived with the same outcome. After watching the film a second time, this predictable suspicion was confirmed, as the few moments of jump scares had little to no impact. And not because they are jump scares, but how they are created. The film also suffers from an interesting but divisive ending and some occasionally shoddy acting.

What Dost Thou Want?... The Witch has a few weaknesses, but it’s still such a solid film that it’s hard to believe it was Robert Egger’s first feature film. The acting, while certainly hit or miss at times, is overall solid for the bulk of the film. Ralph Ineson and Anya Taylor-Joy are standouts continually, having the appropriate look, feel and sound to their characters. It’s convincing throughout that we’re seeing the lives of people in the 1630s because the dialogue, the costumes, and the set design was researched thoroughly and not watered down. This doesn’t have a “Hollywood” feel to it but also doesn’t suffer from that low-budget, amateur-film style that puts many people off. However, the dialogue may be a bit of a turnoff for some people as it’s not exactly easy to follow at times. This is hardly a fault with the film though and was something of a joy to listen to. Ineson delivers his lines with intense gravel that seems otherworldly while Joy has the soft kindness of someone not of our more complicated and corrupt society. Weighing the pros and cons of The Witch results in a clear victory for Robert Egger’s first attempt, the horror community, and A24.

The Witch is a modern classic in American horror that creates memorable images and characters.

Watch The Witch now

THE WITCH: A Dark, Haunting, Atmospheric Folk Tale

One for the road: a bite-sized horror, 30 for 30: american son: celebrating the rise of tennis star michael chang, creature commandos trailer 1, she came back: a haunting fusion of drama and suspense, trap: a concert you’ll want to bail, the story of g.i. joe: the stunning new restoration celebrates the work of war correspondent ernie pyle, the instigators: requiem for the boston movie, joker folie a deux trailer 1, new york asian film festival 2024: pattaya heat, twilight of the warriors: walled in & brush of the god, conclave trailer 1, twisters: maximum escapism, endless charm, but same old twists, captain america: brave new world trailer 1.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Robert Eggers ‘ The Witch is its unwillingness to pander to its audience. Though people may have been expecting a semi-typical supernatural horror film (complete with jumpscares and excessive gore), what they receive instead is something much more disturbing in its implications. Set in Puritan era New England, The Witch is an atmospherically driven, religion-coated film that is, at times, both beautiful and terrifying.

Dark and Brooding

The Witch focuses on a single Puritan family in rural New England in the 17th century. Cast out by their village due to allegations of excessive pride, they settle on the outskirts of a forest to resume their farming lifestyle. The family consists of patriarchal head William ( Ralph Ineson ), wife Katherine ( Kate Dickie ), daughter Thomasin ( Anya Taylor-Joy ), son Caleb, twins Mercy and Jonas, and baby Samuel. One day while Thomasin is playing peekaboo with Samuel, he suddenly disappears before her eyes, and after days of searching, is presumed dead.

The haunting and alluring tone of The Witch is almost immediately present from the first opening images, where we glimpse the dark, brooding woods lurking just outside the family’s home. “There is evil in the wood,” as we know by William’s own words, but exactly what kind of evil is not immediately obvious. That is, until baby Samuel disappears, and what follows is amongst the more horrifying film sequences that I have seen in some time. It is now clear: this is not a film to be taken lightly.

Yet, after easily the most disturbing scene of the film, Eggers turns almost immediately back to the simple Puritan life, which goes on as usual despite the setback of losing a child. Much of Eggers ‘ film is based on this all-too-underused premise: that implications are sometimes much more disturbing than clear, obviously terrifying images. At one point, the parents discuss how lucky they are to have lost only one child, due to not having lost any thus far. To so plainly discuss something that we would typically think of as deeply disheartening is a scary concept indeed.

The Puritan Life

Eggers also chose to linger heavily on the strictly religious lifestyle of this typical Puritan family, where nearly every conversation comes back to their devotion to God, and the idea of sin is greater than any hardship they can endure. After all, William’s family is cast off by their village for religious reasons, and so the importance of daily reverence is even more important as a result.

As the head of the family, William attempts to instill this reverence in every member of his family, with a special emphasis on Thomasin as the eldest child. The scenes between the two often make for some of the more captivating scenes of The Witch , with both Ralph Ineson and Anya Taylor-Joy easily giving the film’s best performances. Ineson in particular, with his deep gruff voice and speaking in the Puritan dialect, almost seems to have been yanked right from that era, while Taylor-Joy is a young but talented actress with much to give.

There are times, though, when The Witch gets even too heavy-handed, especially during some dialogue rich scenes between family members. The religious insinuations become too front-and-center, which unfortunately makes the film appear almost parodic of its subject. Luckily, there are only a few instances where this occurs, as a majority of it is more ideally balanced.

A Folk Tale

The conclusion of The Witch explains that the film is based on folk tales of the time, which would have been written as scary stories to tell around the fire, usually meant to scare straight those who would otherwise stray from their self-disciplined religious lifestyle. They were literal warnings to those who would even consider living their life outside of a strict reverence and devotion to God.

Viewed from this light, it’s easy to see why Eggers made many of the choices he did in his film, such as the decision to not blatantly show the satanic aspects of it from the start. Satanism and evil are always lurking just outside the Puritan’s field of vision, and despite their alluring prospects, it’s up to them to resist its urge. By having such a strict and unwavering way of life, though, the idea of complete freedom is even more enticing. And perhaps this is what The Witch seems to be conveying more than anything else.

The Witch is an exceptional horror film precisely because there are few films to compare it to. It may be underwhelming to those looking for an outright frightening film as opposed to its more stylistic approach, yet there is much to admire about it. If you allow yourself to be caught up in The Witch ‘s mesmerizing tone, it can be a truly satisfying (if also unsettling) cinematic experience.

So what did you think of The Witch? What are some of your favorite recent horror films?

Does content like this matter to you?

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

A family in 1630s New England is torn apart by the forces of witchcraft, black magic and possession. A family in 1630s New England is torn apart by the forces of witchcraft, black magic and possession. A family in 1630s New England is torn apart by the forces of witchcraft, black magic and possession.

- Robert Eggers

- Anya Taylor-Joy

- Ralph Ineson

- Kate Dickie

- 1.3K User reviews

- 598 Critic reviews

- 84 Metascore

- 43 wins & 72 nominations

Top cast 36

- The Witch, Young

- Black Phillip

- (as Wahab Chaudhry)

- Lead Coven Witch

- (as Vivien Moore)

- Coven Witch

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia The spelling of the title "The VVitch" is how the word was written in the story's period because the letter "W" was not yet in common use at the time.

- Goofs One mistake in the dialogue is the incorrect usage of the personal pronouns "Thou" and "You." During the 17th century, "You" was reserved for formal situations, and when one was addressing someone of higher status/rank. "Thou," on the other hand, was used in personal/informal settings and between peers and close relations (similar to the French Tu vs. Vous). Throughout the film, the characters use thou and you interchangeably; however, a close-knit family such as theirs would not have likely addressed each other with the formal "You."

Thomasin : Black Phillip, I conjure thee to speak to me. Speak as thou dost speak to Jonas and Mercy. Dost thou understand my English tongue? Answer me.

Black Phillip : What dost thou want?

Thomasin : What canst thou give?

Black Phillip : Wouldst thou like the taste of butter? A pretty dress? Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?

Thomasin : Yes.

Black Phillip : Wouldst thou like to see the world?

Thomasin : What will you from me?

Black Phillip : Dost thou see a book before thee?... Remove thy shift.

Thomasin : I cannot write my name.

Black Phillip : I will guide thy hand.

- Connections Featured in Film '72: Episode #45.3 (2016)

User reviews 1.3K

- punishable-by-death

- Oct 20, 2015

Every A24 Horror Movie, Ranked by IMDb Rating

- How long is The Witch? Powered by Alexa

- During the exorcist scene, is it the boy talking or is it the witch?

- What is The Witch and what is it about?

- February 19, 2016 (United States)

- United States

- United Kingdom

- Official Site

- Official Site - A24

- Kiosk, Ontario, Canada

- Parts and Labor

- RT Features

- Rooks Nest Entertainment

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- $4,000,000 (estimated)

- $25,138,705

- Feb 21, 2016

- $40,423,945

Technical specs

- Runtime 1 hour 32 minutes

- Dolby Digital

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed.

Get the Reddit app

A more laid-back place for witches of all experience levels and walks of life to talk about witchcraft and all of its little nuances.

I made a video essay about the great European witch-hunt, but from a feminist perspective!

By continuing, you agree to our User Agreement and acknowledge that you understand the Privacy Policy .

Enter the 6-digit code from your authenticator app

You’ve set up two-factor authentication for this account.

Enter a 6-digit backup code

Create your username and password.

Reddit is anonymous, so your username is what you’ll go by here. Choose wisely—because once you get a name, you can’t change it.

Reset your password

Enter your email address or username and we’ll send you a link to reset your password

Check your inbox

An email with a link to reset your password was sent to the email address associated with your account

Choose a Reddit account to continue

Advertisement

Supported by

Fall Preview

27 TV Shows to Watch This Fall

A “WandaVision” spinoff, Colin Farrell in “The Penguin” and Alfonso Cuarón’s “Disclaimer” are among the season’s tantalizing offerings.

- Share full article

By Mike Hale

The fall television season is short on blockbuster titles — a “Star Wars” extension, “Skeleton Crew,” from Disney+, and perhaps HBO’s as-yet-unscheduled “Dune: Prophecy.” But there is plenty that’s of interest, including Alfonso Cuarón’s return to television with “Disclaimer” on Apple TV+, Colin Farrell’s incarnation of the Penguin for HBO and Kathryn Hahn’s reboot of her “WandaVision” character in “Agatha All Along” for Disney+. There will also be new seasons of offbeat but proven comedies like “Bad Sisters” on Apple TV+, “Somebody Somewhere” on HBO and “What We Do in the Shadows,” which, unlike its vampire heroes, will perish after its sixth season on FX. Here are 25 shows to keep an eye out for this fall, in chronological order; all dates are subject to change.

‘ THE OLD MAN ’ In Season 2 of this melancholy spy thriller, Jeff Bridges and John Lithgow return as former C.I.A. colleagues and improbable action buddies — the two actors’ average age is 76, and Lithgow’s character once hired a hit man to kill Bridges’s. (With 76-year-old Kathy Bates starring in CBS’s “Matlock” reboot, it’s a good season for septuagenarians.) (FX, Sept. 12)

‘ HOW TO DIE ALONE ’ The actress and writer Natasha Rothwell (“Insecure,” “White Lotus”) created and stars in this wistful comedy about a lonely airport worker whose life changes after a near-death experience involving an armoire and crab Rangoon. (Hulu, Sept. 13)

‘ AGATHA ALL ALONG ’ Kathryn Hahn returns to her “WandaVision” character in this Marvel spinoff series. The witch Agatha Harkness, stripped of her powers, hits the road and forms a new coven; the cast includes Joe Locke of “Heartstopper,” Sasheer Zamata, Debra Jo Rupp and Aubrey Plaza. (Disney+, Sept. 18)

‘ THE PENGUIN ’ Colin Farrell covers himself in silicone once again to play the waddling gangster Oswald Cobblepot, a.k.a. the Penguin, a role he first essayed in Matt Reeves’s 2022 film “The Batman.” Reeves is an executive producer of this mini-series, and Lauren LeFranc (“Impulse,” “Chuck”) is writer and showrunner. (HBO, Sept. 19)

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Witch (2015) is a movie about a family of early English settlers in America who tear each other apart when supposed evidence of a witch starts appearing....

As Chris Haydon so deftly points out in the below video essay, such an effect is created in a film because several components are working together in beyond-perfect harmony. Landscape For starters, we have DP Jarin Blaschke's stark, dramatic portrayals of the untamed colonial New England landscape.

go to https://mubi.com/filmfatales for 30 days of great cinema for FREE!! 0:00 the witch7:00 witches on film 10112:30 the craft15:40 the witch21:00 the love...

Based on the excellent pacing, imagery and atmosphere, I'd have hoped this film would have a tighter, more clever/witch-based plot. Also, the part where the witch in the goat shed turns around and goes " bleah!" like a a Scooby-Doo character was ridiculous. -3. Reply.

Excellent video essay - The Witch: You are Not So Rational Share Sort by: Best. Open comment sort options. Best. Top. New. Controversial. Old. Q&A. Add a Comment. Lothric43 • That was pretty good. Now I need to watch The Witch again. Reply reply Top 1% Rank by size . More posts you may like Related discussions Witch Movies Like The Witch;

32M subscribers in the movies community. The goal of /r/Movies is to provide an inclusive place for discussions and news about films with major…

The Witch really does feel like it's coming out of the past—much of the dialogue is lifted from historical record—and its characters approach the horrors of the woods in a period-appropriate ...

Three film students vanish after traveling into a Maryland forest to film a documentary on the local Blair Witch legend, leaving only their footage behind.HE...

"The Witch," a period drama/horror film by first-time writer/director Robert Eggers, tellingly advertises itself as "a New England folktale" instead of a fairy tale.Fairy tales are, at heart, parables that prescribe moral values. "The Witch," a feminist narrative that focuses on an American colonial family as they undergo what seems to be an otherworldly curse, is more like a sermon.

The Witch (A24, 2015) Jonas and Mercy, the young fraternal twins, are also seen to reciprocally converse with the he-goat known as Black Phillip; he who gradually assumes the guise of the conduit of Satan. Alongside this quivering presumption, and in response to potential starvation, the young Caleb ventures into the woods in search of game.

R. 1h 32m. By Manohla Dargis. Feb. 18, 2016. A finely calibrated shiver of a movie, "The Witch" opens on a scene of religious wrath. On a New England plantation, around 1630, a true believer ...

Ralph Ineson is an outcast in a film set in seventeenth-century New England. Illustration by Mikkel Sommer. A father and his son, a boy of twelve or so, go into a wood. They are out hunting, armed ...

The audience is constantly left in question of just exactly what the witch looks like, and at the same time the brief glances we do get are absolutely chilling. This tease of just enough but not ...

Film. Read time: 7 mins. Ruth Bushi. 23 March 2022. 27 July 2024. Religious extremism, misogyny and madness stoke fears of the supernatural in The Witch, a folk tale rooted in horror and history. In 17th-century New England a pilgrim family clashes with the church and is banished to the wilderness - and soon falls prey to supernatural forces.

Feb. 18, 2016. It's not long after "The Witch" begins that things get very, very dark. Within the first 10 minutes, the infant son of an isolated 17th-century Puritan family goes missing ...

Watch this video essay highlighting the power of stories to explicate meaning in our daily lives beyond self-preservation. November 9, 2018 By Jacob Trussell What's Inside Robert Eggers ...

The real horror in Robert Eggers' new film The Witch is the limited and punishing road to womanhood. When we meet Thomasin, her family is being exiled from their community and forced to settle in ...

Why I left the center.Support this channel: https://www.patreon.com/contrapoints•Donate: https://paypal.me/contrapoints•Twitter: https://twitter.com/ContraPo...

The Witch is a modern classic in American horror that creates memorable images and characters. My name is Matt and I love film. The Witch: A New-England Folktale [2015] centers on a 17th-century family who believes they are being cursed by a witch. Written and Directed by Robert Eggers and starring Anya Taylor-Joy.

By having such a strict and unwavering way of life, though, the idea of complete freedom is even more enticing. And perhaps this is what The Witch seems to be conveying more than anything else. Conclusion. The Witch is an exceptional horror film precisely because there are few films to compare it to. It may be underwhelming to those looking for ...

Anna Biller's movie is a feminist masterpiece, but not for the reason you might think.All third party clips are used under Fair Use.Anna Biller's work can be...

The Witch: Directed by Robert Eggers. With Anya Taylor-Joy, Ralph Ineson, Kate Dickie, Harvey Scrimshaw. A family in 1630s New England is torn apart by the forces of witchcraft, black magic and possession.

So, I hope it's cool that I post this here! I wrote my Bachelor's thesis about the misogynistic and political aspects of the witch-hunt, that took place between the 15th and 18th centuries, that are very often overlooked when the witch-hunt is discussed, and turned it into a video essay for anyone who'd like to learn more about the subject!

BRIGHTON, Utah — The Utah man who was captured on a viral video threatening a snowboarder who accidentally crossed onto his property near Brighton Ski Resort earlier this year has forfeited his rifle and submitted an essay on the use of deadly force in Utah.Keith Robert Stebbings, 67, was charged with third-degree felony aggravated assault and misdemeanor threat of violence in March.

The witch Agatha Harkness, stripped of her powers, hits the road and forms a new coven; the cast includes Joe Locke of "Heartstopper," Sasheer Zamata, Debra Jo Rupp and Aubrey Plaza. (Disney+ ...