- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Fundamentals of Social Work Research

- Rafael J. Engel - University of Pittsburgh, USA

- Russell K. Schutt - University of Massachusetts Boston, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

The open-access Student Study Site includes the following:

- Mobile-friendly eFlashcards reinforce understanding of key terms and concepts that have been outlined in the chapters.

- Mobile-friendly web quizzes allow for independent assessment of progress made in learning course material.

- EXCLUSIVE! Access to certain full-text SAGE journal articles that have been carefully selected for each chapter. Each article supports and expands on the concepts presented in the chapter. This feature also provides questions to focus and guide student interpretation. Combine cutting-edge academic journal scholarship with the topics in your course for a robust classroom experience.

- Carefully selected, web-based video resources feature relevant interviews, lectures, personal stories, inquiries, and other content for use in independent or classroom-based explorations of key topics.

- Web resources are included for further research and insights.

- Web exercises direct you to useful and current web resources, along with creative activities to extend and reinforce learning or allow for further research on important chapter topics.

- Interactive Exercises based on real research examples allow for improving understanding of methodological concepts.

- GSS Datasets for quantitative data analysis practice.

The open-access Instructor Resource Site includes the following:

· A Microsoft® Word test bank is available containing multiple choice, true/false, short answer, and essay questions for each chapter. The test bank provides you with a diverse range of pre-written options as well as the opportunity for editing any question and/or inserting your own personalized questions to effectively assess students’ progress and understanding.

· A Respondus electronic test bank is available and can be used on PCs. The test bank contains multiple choice, true/false, short answer, and essay questions for each chapter and provides you with a diverse range of pre-written options as well as the opportunity for editing any question and/or inserting your own personalized questions to effectively assess students’ progress and understanding. Respondus is also compatible with many popular learning management systems so you can easily get your test questions into your online course.

· Editable, chapter-specific Microsoft® PowerPoint® slides offer you complete flexibility in easily creating a multimedia presentation for your course. Highlight essential content, features, and artwork from the book.

· Lecture notes summarize key concepts on a chapter-by-chapter basis to help with preparation for lectures and class discussions.

· EXCLUSIVE! Access to certain full-text SAGE journal articles that have been carefully selected for each chapter. Each article supports and expands on the concepts presented in the chapter. This feature also provides questions to focus and guide student interpretation. Combine cutting-edge academic journal scholarship with the topics in your course for a robust classroom experience.

· Sample course syllabi provide suggested models for use when creating the syllabi for your courses.

· Suggested course projects are designed to promote students’ in-depth engagement with course material.

· Carefully selected, web-based video resources feature relevant interviews, lectures, personal stories, inquiries, and other content for use in independent or classroom-based explorations of key topics.

· Web resources are included for further research and insights.

NEW TO THIS EDITION:

- A new chapter devoted to research ethics lays the foundation for the specific ethics sections in the individual chapters and includes coverage of internet-based research with more on netnography and interviewing online.

- New sections discuss mixed methods research and community-based participatory research .

- An added focus on qualitative research includes questions to use in evaluating a qualitative research study and a new Appendix D, "How to Read a Qualitative Research Article.”

- Updated examples integrate content on diversity and evidence-based practice.

- A new matrix links the topics covered in the book with CSWE Core Competencies.

- Additional content on evidence-based practice includes the steps associated with the EBP decision model and the challenges in implementing EBP.

- Coverage of emerging research efforts that use the Internet and other electronic media as a research tool has been added.

- Many findings are now presented through presentations, publications, and reports .

KEY FEATURES:

- Text content is fully integrated with CSWE Competencies .

- An engaging writing style coupled with real, applied examples demonstrates why a study of research methods is relevant and interesting to future social workers.

- Research with diverse populations is infused into every chapter.

- Ethical concerns are highlighted in each chapter, along with chapter-ending ethics exercises.

- Evidence-based practice is integrated throughout the text.

- Chapter-ending exercises ask students to critically evaluate quantitative and qualitative research studies.

- An expansive Student Study Site helps students master key topics through a variety of contemporary research examples, interactive exercises, quizzes, e-flashcards, web exercises, and more.

Sample Materials & Chapters

For instructors, select a purchasing option.

- Skip to header navigation

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Member login

International Federation of Social Workers

Global Online conference

Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles

July 2, 2018

Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles:

This Statement of Ethical Principles (hereafter referred to as the Statement) serves as an overarching framework for social workers to work towards the highest possible standards of professional integrity.

Implicit in our acceptance of this Statement as social work practitioners, educators, students, and researchers is our commitment to uphold the core values and principles of the social work profession as set out in this Statement.

An array of values and ethical principles inform us as social workers; this reality was recognized in 2014 by the International Federation of Social Workers and The International Association of Schools of Social Work in the global definition of social work, which is layered and encourages regional and national amplifications.

All IFSW policies including the definition of social work stem from these ethical principles.

Social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that facilitates social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledge, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing . http://ifsw.org/get-involved/global-definition-of-social-work/

Principles:

- Recognition of the Inherent Dignity of Humanity

Social workers recognize and respect the inherent dignity and worth of all human beings in attitude, word, and deed. We respect all persons, but we challenge beliefs and actions of those persons who devalue or stigmatize themselves or other persons.

- Promoting Human Rights

Social workers embrace and promote the fundamental and inalienable rights of all human beings. Social work is based on respect for the inherent worth, dignity of all people and the individual and social /civil rights that follow from this. Social workers often work with people to find an appropriate balance between competing human rights.

- Promoting Social Justice

Social workers have a responsibility to engage people in achieving social justice, in relation to society generally, and in relation to the people with whom they work. This means:

3.1 Challenging Discrimination and Institutional Oppression

Social workers promote social justice in relation to society generally and to the people with whom they work.

Social workers challenge discrimination, which includes but is not limited to age, capacity, civil status, class, culture, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, language, nationality (or lack thereof), opinions, other physical characteristics, physical or mental abilities, political beliefs, poverty, race, relationship status, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, spiritual beliefs, or family structure.

3.2 Respect for Diversity

Social workers work toward strengthening inclusive communities that respect the ethnic and cultural diversity of societies, taking account of individual, family, group, and community differences.

3.3 Access to Equitable Resources

Social workers advocate and work toward access and the equitable distribution of resources and wealth.

3.4 Challenging Unjust Policies and Practices

Social workers work to bring to the attention of their employers, policymakers, politicians, and the public situations in which policies and resources are inadequate or in which policies and practices are oppressive, unfair, or harmful. In doing so, social workers must not be penalized.

Social workers must be aware of situations that might threaten their own safety and security, and they must make judicious choices in such circumstances. Social workers are not compelled to act when it would put themselves at risk.

3.5 Building Solidarity

Social workers actively work in communities and with their colleagues, within and outside of the profession, to build networks of solidarity to work toward transformational change and inclusive and responsible societies.

- Promoting the Right to Self-Determination

Social workers respect and promote people’s rights to make their own choices and decisions, provided this does not threaten the rights and legitimate interests of others.

- Promoting the Right to Participation

Social workers work toward building the self-esteem and capabilities of people, promoting their full involvement and participation in all aspects of decisions and actions that affect their lives.

- Respect for Confidentiality and Privacy

6.1 Social workers respect and work in accordance with people’s rights to confidentiality and privacy unless there is risk of harm to the self or to others or other statutory restrictions.

6.2 Social workers inform the people with whom they engage about such limits to confidentiality and privacy.

- Treating People as Whole Persons

Social workers recognize the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of people’s lives and understand and treat all people as whole persons. Such recognition is used to formulate holistic assessments and interventions with the full participation of people, organizations, and communities with whom social workers engage.

- Ethical Use of Technology and Social Media

8.1 The ethical principles in this Statement apply to all contexts of social work practice, education, and research, whether it involves direct face-to-face contact or through use of digital technology and social media.

8.2 Social workers must recognize that the use of digital technology and social media may pose threats to the practice of many ethical standards including but not limited to privacy and confidentiality, conflicts of interest, competence, and documentation and must obtain the necessary knowledge and skills to guard against unethical practice when using technology.

- Professional Integrity

9.1 It is the responsibility of national associations and organizations to develop and regularly update their own codes of ethics or ethical guidelines, to be consistent with this Statement, considering local situations. It is also the responsibility of national organizations to inform social workers and schools of social work about this Statement of Ethical Principles and their own ethical guidelines. Social workers should act in accordance with the current ethical code or guidelines in their country.

9.2 Social workers must hold the required qualifications and develop and maintain the required skills and competencies to do their job.

9.3 Social workers support peace and nonviolence. Social workers may work alongside military personnel for humanitarian purposes and work toward peacebuilding and reconstruction. Social workers operating within a military or peacekeeping context must always support the dignity and agency of people as their primary focus. Social workers must not allow their knowledge and skills to be used for inhumane purposes, such as torture, military surveillance, terrorism, or conversion therapy, and they should not use weapons in their professional or personal capacities against people.

9.4 Social workers must act with integrity. This includes not abusing their positions of power and relationships of trust with people that they engage with; they recognize the boundaries between personal and professional life and do not abuse their positions for personal material benefit or gain.

9.5 Social workers recognize that the giving and receiving of small gifts is a part of the social work and cultural experience in some cultures and countries. In such situations, this should be referenced in the country’s code of ethics.

9.6 Social workers have a duty to take the necessary steps to care for themselves professionally and personally in the workplace, in their private lives and in society.

9.7 Social workers acknowledge that they are accountable for their actions to the people they work with; their colleagues; their employers; their professional associations; and local, national, and international laws and conventions and that these accountabilities may conflict, which must be negotiated to minimize harm to all persons. Decisions should always be informed by empirical evidence; practice wisdom; and ethical, legal, and cultural considerations. Social workers must be prepared to be transparent about the reasons for their decisions.

9.8 Social workers and their employing bodies work to create conditions in their workplace environments and in their countries, where the principles of this Statement and those of their own national codes are discussed, evaluated, and upheld. Social workers and their employing bodies foster and engage in debate to facilitate ethically informed decisions.

Spanish translation – Traducción Español

Chinese Translation 全球社會工作倫理原則聲明 (繁體字譯本)

The Global Statement of Ethical Principles was approved at the General Meetings of the International Federation of Social Workers and the General Assembly of the International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) in Dublin, Ireland, in July 2018. IASSW additionally endorsed a longer version: Global-Social-Work-Statement-of-Ethical-Principles-IASSW-27-April-2018-1

National Code of Ethics

National Codes of Ethics of Social Work adopted by IFSW Member organisations. The Codes of Ethics are in the national languages of the different countries. More national codes of ethics will soon be added to the ones below:

- Canada | Guidelines for ethical practice

- Finland (Englis)

- Finland (Finish)

- Puerto Rico English | Spanish

- South Korea English | Korean

- Sweden English | Swedish

- Switzerland English | German | French | Italian

- Turkey English | Turkish

- United Kingdom

- Login / Account

- Documentation

- Online Participation

- Constitution/ Governance

- Secretariat

- Our members

- General Meetings

- Executive Meetings

- Meeting papers 2018

- Global Definition of Social Work

- Meet Social Workers from around the world

- Frequently Asked Questions

- IFSW Africa

- IFSW Asia and Pacific

- IFSW Europe

- IFSW Latin America and Caribbean

- IFSW North America

- Education Commission

- Ethics Commission

- Indigenous Commission

- United Nations Commission

- Information Hub

- Upcoming Events

- Keynote Speakers

- Global Agenda

- Archive: European DM 2021

- The Global Agenda

- World Social Work Day

A guide to social work ethics

You might have heard the phrase “social work ethics” but may be confused by what the term means and how it applies to the social work profession. This guide covers social work ethics, how ethics guide social workers’ behaviors and actions, and how professionals build their knowledge and skills around ethical dilemmas. In addition, state requirements for ethics training are covered, as is a discussion around how social work ethics apply to our now largely remote working world.

IN THIS GUIDE

- Where do social work ethics come from?

How are social workers trained in ethics?

State requirements for ethics training.

- Ethics in a remote work world

What are social work ethics?

Ethics are a code of morals or a moral philosophy that governs an individual’s behaviors and actions. It is also considered a set of standards or code of conduct set forth by a company or profession. Social work ethics are guidelines that social workers must abide by when acting in their professional capacity. Ethics differentiate between right and wrong and describe actions that are permissible or forbidden.

Who develops social work ethics?

The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) develops ethical guidelines for social workers. NASW is the largest membership organization of professional social workers around the world. The NASW establishes the principles, values, and standards that guide the profession. In addition, the organization strives to enhance the professional development and growth of its members and promote sound social policies.

The first NASW Code of Ethics was developed and approved in 1960. Revisions were made in 1967, 1979, 1990, 1993, 1996, 1999, and 2008. The latest revision occurred to the NASW Code of Ethics in August 2017.

A social worker does not need to be a member of NASW to be accountable to the professional ethical standards. However, NASW members are required to uphold the Code of Ethics. In addition, as will be discussed later in this guide, many states incorporate the Code of Ethics into their licensing requirements, so any licensed social worker in that state must also abide by the ethical guidelines set forth by NASW.

NASW states that the profession has overarching core values that guide the development of ethical principles. In turn, these create the format for social work ethical standards.

What are the social work ethical principles?

Social work ethics are based on the profession’s core values of social justice, service, dignity, and worth of each person, integrity, the importance of human relationships, and competence. These are the overarching ideals to which all social work professionals should aspire. These ethical principles lay the foundation for specific ethical standards that social workers need to follow.

Social work ethical principles include:

- Social justice: social workers are to challenge social injustice and seek social change on behalf of vulnerable and oppressed individuals and groups of people.

- Service: the primary goals of the profession are to address social problems and help people in need.

- Dignity and worth: social workers respect the inherent dignity and worth of each person, being mindful of diversity, and interact with each individual in a caring and respectful manner.

- Integrity: social workers are trustworthy, understanding the profession’s ethical responsibilities and acting in ways that are consistent with those requirements.

- Importance of human relationships: social workers understand that relationships are a critical vehicle of change and work to include clients as partners in the helping process.

- Competency: social workers are constantly increasing their skills and knowledge to apply these improved skills in practice. Social workers also contribute to the professions’ knowledge base by conducting, reading, and promoting research.

What are the social work ethical standards?

According to the Code of Ethics , the ethical standards categories concern social workers’ ethical responsibilities:

- To colleagues

- In practice settings

- As professionals

- To the social work profession

- To the broader society

Within each category are several standards that guide how a social worker is to act. Each standard also has a number of both enforceable and aspirational guidelines within it for social workers to follow.

Under Ethical Standard Category 1, Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities to Clients fall the following standards:

- Commitment to clients

- Self-determination

- Informed consent

- Cultural awareness and diversity

- Conflicts of interest

- Privacy and confidentiality

- Access to records

- Sexual relationships

- Physical contact

- Sexual harassment

- Derogatory language

- Payment for services

- Clients who lack decision-making capacity

- Interruption of services

- Referral for services

- Termination of services

Standard Category 2, which is Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities to Colleagues includes:

- Confidentiality

- Interdisciplinary collaboration

- Disputes involving colleagues

- Consultation

- Impairment of colleagues

- Incompetence of colleagues

- Unethical conduct of colleagues

Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities in Practice Settings is Standard Category 3 and includes:

- Supervision and consultation

- Education and training

- Performance evaluation

- Client records

- Client transfer

- Administration

- Continuing education and staff development

- Commitments to employers

- Labor-management disputes

Standard Category 4 is Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities as Professionals, which includes:

- Discrimination

- Private conduct

- Dishonesty, fraud, and deception

- Misrepresentation

- Solicitations

- Acknowledging credit

Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities to the Social Work Profession is Standard Category 5 and encompasses:

- Integrity of the profession

- Evaluation and research

Standard Category 6 is Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities to the Broader Society and includes:

- Social welfare

- Public participation

- Public emergencies

- Social and Political action

Social workers receive ethical training both while in school and after graduation via their workplace through professional development training or continuing education opportunities. Ethics training is a necessary component of the profession and requires ongoing knowledge and skills development, particularly as advances happen with technology, and changes occur in the social climate.

Most social work education programs are accredited through the Council for Social Work Education . This organization certifies that the bachelor’s or master’s degree program has met the standards set forth for professional social work education. To be accredited, the educational program must demonstrate its commitment to educating and assessing students in their adherence to following CSWE’s nine social work competencies.

Each competency ties back into various portions of the NASW Code of Ethics. Educators must weave ethical discussions, simulations, lectures, and readings into their courses and provide students opportunities to consider or role play ethical dilemmas and scenarios that might arise in their work.

As a component of continued accreditation, instructors review students at the end of the course on how well each student met the course’s social work competency or competencies. This task also helps instructors review their own work and make adjustments as necessary to improve future students’ knowledge and skills in recognizing and adhering to the NASW Code of Ethics.

Graduates of social work programs interested in obtaining social work licensure must complete a licensure examination. Professionals studying to take the exam often learn or refresh their knowledge about ethical responsibilities and requirements through exam study guides or study groups, as the exam contains questions about ethical standards and hypothetical ethical scenarios.

Agencies also further a social workers’ knowledge and skills via informal staff supervision and professional development training. Supervisors should work with new professionals to discuss concerning situations and talk about how the social worker should handle ethical dilemmas. Continuing education is also a method for ongoing training in the field of ethics. Conferences, webinars, and online courses are all methods by which someone can complete ethics training. These training programs often provide continuing education credits necessary to maintain employment or professional certifications or licensure.

In addition, NASW offers free online training on the latest changes to the Code of Ethics. Members can also earn two continuing education credits for free by completing this training module. Non-NASW members can earn continuing education credits with a nominal fee.

As previously mentioned, states require specific numbers of ethics continuing education hours or credits for social work certification or licensure. These hours are part of more extensive credit requirements that the professional must complete within a specific timeframe. Most states require a social worker to complete three hours of ethics training every two years. Below are some other examples from states that have different requirements:

- Idaho mandates an hour of ethics training annually

- Virginia insists on 1.5 hours of training every two years

- Two hours of ethics training every two years is required by Minnesota and North Dakota

- in Maine , Mississippi, North Carolina , and Wisconsin mandate four hours of training every two years.

- Georgia and New Jersey require five hours every two years

- California , New Hampshire , Oregon , Texas , and Washington mandate six hours of training every two years

- Michigan requires 5 hours of ethics training every three years

- Connecticut and West Virginia do not specifically mandate ethics training in their annual training hour requirements but rather recommend ethics training to social work professionals

Be sure to check the websites of each states’ licensing board for the most up-to-date requirements.

How do social work ethics apply in a remote work world?

Now that more people, both social work professionals, and their clients, are working remotely, adaptations were needed to accommodate these changes. Telehealth, which provides health and mental health services virtually either by phone or via computer, has quickly become the norm in the time of social distancing. Despite services not being provided face to face with clients, social workers must still follow the Code of Ethics.

Thankfully, several standards already address technology and social work, including:

Standard 1.03 – Informed Consent: (e) Social workers should discuss with clients the social workers’ policies concerning the use of technology in the provision of professional services. (g) Social workers who use technology to provide social work services should assess the clients’ suitability and capacity for electronic and remote services. Social workers should consider the clients’ intellectual, emotional, and physical ability to use technology to receive services and the clients’ ability to understand the potential benefits, risks, and limitations of such services. If clients do not wish to use services provided through technology, social workers should help them identify alternate methods of service.

Standard 1.04 – Competence: (d) Social workers who use technology in the provision of social work services should ensure that they have the necessary knowledge and skills to provide such services in a competent manner. This includes understanding the special communication challenges when using technology and the ability to implement strategies to address these challenges.

Standard 1.05 – Cultural Awareness and Social Diversity: (d) Social workers who provide electronic social work services should be aware of cultural and socioeconomic differences among clients and how they may use electronic technology. Social workers should assess cultural, environmental, economic, mental or physical ability, linguistic, and other issues that may affect the delivery or use of these services.

Standard 1.07 – Privacy and Confidentiality: (m) Social workers should take reasonable steps to protect the confidentiality of electronic communications, including information provided to clients or third parties. Social workers should use applicable safeguards (such as encryption,firewalls, and passwords) when using electronic communications such as e-mail, online posts, online chat sessions, mobile communication, and text messages.

The committee that helped develop the latest round of revisions to the Code of Ethics in 2017 could not have predicted the reasons for remote service provision that we face today. Thankfully, however, the committee considered technology and how it could and might be used to serve clients as they drafted revisions. These standards have and continue to serve the profession well.

Social work ethics are guidelines that social workers must abide by when acting in their professional capacity. Ethics differentiate between right and wrong and describe actions that are permissible or forbidden. Social workers have ethical responsibilities to clients, colleagues, practice settings, professionals, the social work profession, and the broader society. The National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics is the guidebook on how social workers can meet those essential ethical responsibilities.

Aadam, B., Petrakis, M. (2020). Ethics, values, and recovery in mental health social work practice. In: Ow R., Poon, A. (eds) Mental Health and Social Work. Springer.

McCarthy, L.P., Imboden, R., Shdaimah, C.S., & Forrester, P. (2020). ‘Ethics are messy’: Supervision as a tool to help social workers manage ethical challenges. Ethics and Social Welfare, 14 (1):118-134.

National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Code of Ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics .

Reamer, F.G. (2018). Social Work Values and Ethics. Columbia University Press.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.2: Overview of the Research Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 26219

- Anol Bhattacherjee

- University of South Florida via Global Text Project

So how do our mental paradigms shape social science research? At its core, all scientific research is an iterative process of observation, rationalization, and validation. In the observation phase, we observe a natural or social phenomenon, event, or behavior that interests us. In the rationalization phase, we try to make sense of or the observed phenomenon, event, or behavior by logically connecting the different pieces of the puzzle that we observe, which in some cases, may lead to the construction of a theory. Finally, in the validation phase, we test our theories using a scientific method through a process of data collection and analysis, and in doing so, possibly modify or extend our initial theory. However, research designs vary based on whether the researcher starts at observation and attempts to rationalize the observations (inductive research), or whether the researcher starts at an ex ante rationalization or a theory and attempts to validate the theory (deductive research). Hence, the observation-rationalization-validation cycle is very similar to the induction-deduction cycle of research discussed in Chapter 1.

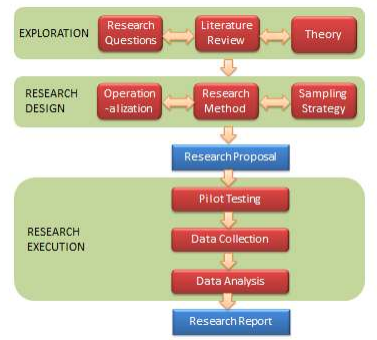

Most traditional research tends to be deductive and functionalistic in nature. Figure 3.2 provides a schematic view of such a research project. This figure depicts a series of activities to be performed in functionalist research, categorized into three phases: exploration, research design, and research execution. Note that this generalized design is not a roadmap or flowchart for all research. It applies only to functionalistic research, and it can and should be modified to fit the needs of a specific project.

The first phase of research is exploration . This phase includes exploring and selecting research questions for further investigation, examining the published literature in the area of inquiry to understand the current state of knowledge in that area, and identifying theories that may help answer the research questions of interest.

The first step in the exploration phase is identifying one or more research questions dealing with a specific behavior, event, or phenomena of interest. Research questions are specific questions about a behavior, event, or phenomena of interest that you wish to seek answers for in your research. Examples include what factors motivate consumers to purchase goods and services online without knowing the vendors of these goods or services, how can we make high school students more creative, and why do some people commit terrorist acts. Research questions can delve into issues of what, why, how, when, and so forth. More interesting research questions are those that appeal to a broader population (e.g., “how can firms innovate” is a more interesting research question than “how can Chinese firms innovate in the service-sector”), address real and complex problems (in contrast to hypothetical or “toy” problems), and where the answers are not obvious. Narrowly focused research questions (often with a binary yes/no answer) tend to be less useful and less interesting and less suited to capturing the subtle nuances of social phenomena. Uninteresting research questions generally lead to uninteresting and unpublishable research findings.

The next step is to conduct a literature review of the domain of interest. The purpose of a literature review is three-fold: (1) to survey the current state of knowledge in the area of inquiry, (2) to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and (3) to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area. Literature review is commonly done today using computerized keyword searches in online databases. Keywords can be combined using “and” and “or” operations to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a shortlist of relevant articles is generated from the keyword search, the researcher must then manually browse through each article, or at least its abstract section, to determine the suitability of that article for a detailed review. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology. Reviewed articles may be summarized in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organizing frameworks such as a concept matrix. A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature (which would obviate the need to study them again), whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review. The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions.

Since functionalist (deductive) research involves theory-testing, the third step is to identify one or more theories can help address the desired research questions. While the literature review may uncover a wide range of concepts or constructs potentially related to the phenomenon of interest, a theory will help identify which of these constructs is logically relevant to the target phenomenon and how. Forgoing theories may result in measuring a wide range of less relevant, marginally relevant, or irrelevant constructs, while also minimizing the chances of obtaining results that are meaningful and not by pure chance. In functionalist research, theories can be used as the logical basis for postulating hypotheses for empirical testing. Obviously, not all theories are well-suited for studying all social phenomena. Theories must be carefully selected based on their fit with the target problem and the extent to which their assumptions are consistent with that of the target problem. We will examine theories and the process of theorizing in detail in the next chapter.

The next phase in the research process is research design . This process is concerned with creating a blueprint of the activities to take in order to satisfactorily answer the research questions identified in the exploration phase. This includes selecting a research method, operationalizing constructs of interest, and devising an appropriate sampling strategy.

Operationalization is the process of designing precise measures for abstract theoretical constructs. This is a major problem in social science research, given that many of the constructs, such as prejudice, alienation, and liberalism are hard to define, let alone measure accurately. Operationalization starts with specifying an “operational definition” (or “conceptualization”) of the constructs of interest. Next, the researcher can search the literature to see if there are existing prevalidated measures matching their operational definition that can be used directly or modified to measure their constructs of interest. If such measures are not available or if existing measures are poor or reflect a different conceptualization than that intended by the researcher, new instruments may have to be designed for measuring those constructs. This means specifying exactly how exactly the desired construct will be measured (e.g., how many items, what items, and so forth). This can easily be a long and laborious process, with multiple rounds of pretests and modifications before the newly designed instrument can be accepted as “scientifically valid.” We will discuss operationalization of constructs in a future chapter on measurement.

Simultaneously with operationalization, the researcher must also decide what research method they wish to employ for collecting data to address their research questions of interest. Such methods may include quantitative methods such as experiments or survey research or qualitative methods such as case research or action research, or possibly a combination of both. If an experiment is desired, then what is the experimental design? If survey, do you plan a mail survey, telephone survey, web survey, or a combination? For complex, uncertain, and multifaceted social phenomena, multi-method approaches may be more suitable, which may help leverage the unique strengths of each research method and generate insights that may not be obtained using a single method.

Researchers must also carefully choose the target population from which they wish to collect data, and a sampling strategy to select a sample from that population. For instance, should they survey individuals or firms or workgroups within firms? What types of individuals or firms they wish to target? Sampling strategy is closely related to the unit of analysis in a research problem. While selecting a sample, reasonable care should be taken to avoid a biased sample (e.g., sample based on convenience) that may generate biased observations. Sampling is covered in depth in a later chapter.

At this stage, it is often a good idea to write a research proposal detailing all of the decisions made in the preceding stages of the research process and the rationale behind each decision. This multi-part proposal should address what research questions you wish to study and why, the prior state of knowledge in this area, theories you wish to employ along with hypotheses to be tested, how to measure constructs, what research method to be employed and why, and desired sampling strategy. Funding agencies typically require such a proposal in order to select the best proposals for funding. Even if funding is not sought for a research project, a proposal may serve as a useful vehicle for seeking feedback from other researchers and identifying potential problems with the research project (e.g., whether some important constructs were missing from the study) before starting data collection. This initial feedback is invaluable because it is often too late to correct critical problems after data is collected in a research study.

Having decided who to study (subjects), what to measure (concepts), and how to collect data (research method), the researcher is now ready to proceed to the research execution phase. This includes pilot testing the measurement instruments, data collection, and data analysis.

Pilot testing is an often overlooked but extremely important part of the research process. It helps detect potential problems in your research design and/or instrumentation (e.g., whether the questions asked is intelligible to the targeted sample), and to ensure that the measurement instruments used in the study are reliable and valid measures of the constructs of interest. The pilot sample is usually a small subset of the target population. After a successful pilot testing, the researcher may then proceed with data collection using the sampled population. The data collected may be quantitative or qualitative, depending on the research method employed.

Following data collection, the data is analyzed and interpreted for the purpose of drawing conclusions regarding the research questions of interest. Depending on the type of data collected (quantitative or qualitative), data analysis may be quantitative (e.g., employ statistical techniques such as regression or structural equation modeling) or qualitative (e.g., coding or content analysis).

The final phase of research involves preparing the final research report documenting the entire research process and its findings in the form of a research paper, dissertation, or monograph. This report should outline in detail all the choices made during the research process (e.g., theory used, constructs selected, measures used, research methods, sampling, etc.) and why, as well as the outcomes of each phase of the research process. The research process must be described in sufficient detail so as to allow other researchers to replicate your study, test the findings, or assess whether the inferences derived are scientifically acceptable. Of course, having a ready research proposal will greatly simplify and quicken the process of writing the finished report. Note that research is of no value unless the research process and outcomes are documented for future generations; such documentation is essential for the incremental progress of science.

Principles of Social Research Methodology

- © 2022

- M. Rezaul Islam 0 ,

- Niaz Ahmed Khan 1 ,

- Rajendra Baikady 2

Centre for Family and Child Studies, Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Department of social work, school of humanities, university of johannesburg, johannesburg, south africa.

- Emphasizes the essentials and fundamentals of research methodologies

- Covers the entire research process, beginning with the conception of the research problem

- Combines theory and practical application to familiarize the reader with the logic of research design

76k Accesses

32 Citations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (35 chapters)

Front matter, introduction to social research, inquiry: a fundamental concept for scientific investigation.

M. Rezaul Islam

Research: Meaning and Purpose

- Kazi Abusaleh, Akib Bin Anwar

Social Research: Definitions, Types, Nature, and Characteristics

- Kanamik Kani Khan, Md. Mohsin Reza

Theory in Social Research

- Mumtaz Ali, Maya Khemlani David, Kuang Ching Hei

Philosophy of Social Science and Research Paradigms

Inductive and/or deductive research designs.

- Md. Shahidul Haque

- Premalatha Karupiah

Critical Theory in Social Research: A Theoretical and Methodological Outlook

- Ashek Mahmud, Farhana Zaman

Narrative Inquiry, Phenomenology, and Grounded Theory in Qualitative Research

- Rabiul Islam, Md. Sayeed Akhter

- Md. Rafiqul Islam

Quantitative Research Approach

Designing research proposal in quantitative approach.

- Md. Rezaul Karim

Experimental Method

- Syed Tanveer Rahman, Md. Rabiul Islam

Social Survey Method

- Isahaque Ali, Azlinda Azman, Shahid Mallick, Tahmina Sultana, Zulkarnain A. Hatta

Survey Questionnaire

- Shofiqur Rahman Chowdhury, Mohammad Ali Oakkas, Faisal Ahmmed

Interview Method

- Hazreena Hussein

Sampling Techniques for Quantitative Research

- Moniruzzaman Sarker, Mohammed Abdulmalek AL-Muaalemi

Data Analysis Techniques for Quantitative Study

- Social Science Research

- Social Research Methods

- Qualitative Research

- Quantitative Research

- Mixed Method Research

- Research Design

About this book

This book is a definitive, comprehensive understanding to social science research methodology. It covers both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The book covers the entire research process, beginning with the conception of the research problem to publication of findings. The text combines theory and practical application to familiarize the reader with the logic of research design, the logic and techniques of data analysis, and the fundamentals and implications of various data collection techniques. Organized in seven sections and easy to read chapters, the text emphasizes the importance of clearly defined research questions and well-constructed practical explanations and illustrations. A key contribution to the methodology literature, the book is an authoritative resource for policymakers, practitioners, graduate and advanced research students, and educators in all social science disciplines.

Editors and Affiliations

Niaz Ahmed Khan

Rajendra Baikady

About the editors

Bibliographic information.

Book Title : Principles of Social Research Methodology

Editors : M. Rezaul Islam, Niaz Ahmed Khan, Rajendra Baikady

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2

Publisher : Springer Singapore

eBook Packages : Social Sciences

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2022

Hardcover ISBN : 978-981-19-5219-7 Published: 27 October 2022

Softcover ISBN : 978-981-19-5524-2 Published: 28 October 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-981-19-5441-2 Published: 26 October 2022

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXXI, 508

Number of Illustrations : 24 b/w illustrations, 45 illustrations in colour

Topics : Social Work , Education, general

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Scientific Inquiry in Social Work

(9 reviews)

Matthew DeCarlo, Radford University

Copyright Year: 2018

ISBN 13: 9781975033729

Publisher: Open Social Work Education

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Shannon Blajeski, Assistant Professor, Portland State University on 3/10/23

This book provides an introduction to research and inquiry in social work with an applied focus geared for the MSW student. The text covers 16 chapters, including several dedicated to understanding how to begin the research process, a chapter on... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This book provides an introduction to research and inquiry in social work with an applied focus geared for the MSW student. The text covers 16 chapters, including several dedicated to understanding how to begin the research process, a chapter on ethics, and then eight chapters dedicated to research methods. The subchapters (1-5 per chapter) are concise and focused while also being tied to current knowledge and events so as to hold the reader's attention. It is comprehensive, but some of the later chapters covering research methods as well as the final chapter seem a bit scant and could be expanded. The glossary at the end of each chapter is helpful as is the index that is always accessible from the left-hand drop-down menu.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

The author pulls in relevant current and recent public events to illustrate important points about social research throughout the book. Each sub-chapter reads as accurate. I did not come across any inaccuracies in the text, however I would recommend a change in the title of Chapter 15 as "real world research" certainly encompasses more than program evaluation, single-subject designs, and action research.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

Another major strength of this book is that it adds currency to engage the reader while also maintaining its relevance to research methods. None of the current events/recent events that are described seem dated nor will they fade from relevance in a number of years. In addition, the concise nature of the modules should make them easy to update when needed to maintain relevancy in future editions.

Clarity rating: 5

Clarity is a major strength of this textbook. As described in the interface section, this book is written to be clear and concise, without unnecessary extra text that detracts from the concise content provided in each chapter. Any lengthy excerpts are also very engaging which lends itself to a clear presentation of content for the reader.

Consistency rating: 5

The text and content seems to be presented consistently throughout the book. Terminology and frameworks are balanced with real-world examples and current events.

Modularity rating: 5

The chapters of this textbook are appropriately spaced and easily digestible, particularly for readers with time constraints. Each chapter contains 3-5 sub-chapters that build upon each other in a scaffolding style. This makes it simple for the instructor to assign each chapter (sometimes two) per weekly session as well as add in additional assigned readings to complement the text.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The overall organization of the chapters flow well. The book begins with a typical introduction to research aimed at social work practitioners or new students in social work. It then moves into a set of chapters on beginning a research project, reviewing literature, and asking research questions, followed by a chapter on ethics. Next, the text transitions to three chapters covering constructs, measurement, and sampling, followed by five chapters covering research methods, and a closing chapter on dissemination of research. This is one of the more logically-organized research methods texts that I have used as an instructor.

Interface rating: 5

The modular chapters are easy to navigate and the interface of each chapter follows a standard presentation style with the reading followed by a short vocabulary glossary and references. This presentation lends itself to a familiarity for students that helps them become more efficient with completing reading assignments, even in short bursts of time. This is particularly important for online and returning learners who may juggle their assignment time with family and work obligations.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

No grammatical errors were noted.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

At first glance at the table of contents, the book doesn't seem to be overtly committed to cultural representation, however, upon reading the chapters, it becomes clear that the author does try to represent and reference marginalized groups (e.g., women, individuals with disabilities, racial/ethnic/gender intersectionality) within the examples used. I also am very appreciative that the bottom of each introduction page for each chapter contains content trigger warnings for any possible topics that could be upsetting, e.g., substance abuse, violence.

As the author likely knows, social work students are eager to engage in learning that is current and relevant to their social causes. This book is written in a way that engages a non-researcher social worker into reading about research by weaving research information into topics that they might find compelling. It also does this in a concise way where short bits of pertinent information are presented, making the text accessible without needing to sustain long periods of attention. This is particularly important for online and returning learners who may need to sit with their readings in short bursts due to attending school while juggling work and family obligations.

Reviewed by Lynn Goerdt, Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin - Superior on 9/17/21

Text appears to be comprehensive in covering steps for typical SWK research class, taking students from the introduction of the purpose and importance of research to how to design and analyze research. Author covers the multitude of ways that... read more

Text appears to be comprehensive in covering steps for typical SWK research class, taking students from the introduction of the purpose and importance of research to how to design and analyze research. Author covers the multitude of ways that social workers engage in research as way of building knowledge and ways that social work practitioners conduct research to evaluate their practice, including outcome evaluation, single subject design, and action research. I particularly appreciated the last section on reporting research, which should be very practical.

Overall, content appears mostly accurate which few errors. Definitions and citations are mostly thorough and clear. Author does cite Wikipedia in at least one occasion which could be credible, depending on the source of the Wikipedia content. There were a few references within the text to comic or stories but the referenced material was not always apparent.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

The content of Scientific Inquiry for Social Work is relevant, as the field of social work research methods does not appear to change quickly, although there are innovations. The author referenced examples which appear to be recent and likely relatable to interests of current students. Primary area of innovation is in using technology for the collection and analysis of data, which could be expanded, particularly using social media for soliciting research participants.

Style is personable and content appears to be accessible, which is a unique attribute for a research textbook. Author uses first person in many instances, particularly in the beginning to present the content as relatable.

Format appears to be consistent in format and relative length. Each chapter includes learning objectives, content advisory (if applicable), key takeaways and glossary. Author uses color and text boxes to draw attention to these sections.

Modularity rating: 4

Text is divided into modules which could easily be assigned and reviewed in a class. The text modules could also be re-structured if desired to fit curricular uniqueness’s. Author uses images to illuminate the concepts of the module or chapter, but they often take about 1/3 of the page, which extends the size of the textbook quite a bit. Unclear if benefit of images outweighs additional cost if PDF version is printed.

Textbook is organized in a very logical and clear fashion. Each section appears to be approximately 6-10 pages in length which seems to be an optimal length for student attention and comprehension.

Interface rating: 4

There were some distortions of the text (size and visibility) but they were a fairly minor distraction and did not appear to reduce access to the content. Otherwise text was easy to navigate.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

No grammatical errors were noted but hyperlinks to outside content were referenced but not always visible which occasionally resulted in an awkward read. Specific link may be in resources section of each chapter but occasionally they were also included in the text.

I did not recognize any text which was culturally insensitive or offensive. Images used which depicted people, appeared to represent diverse experiences, cultures, settings and persons. Did notice image depicting homelessness appeared to be stereotypical person sleeping on sidewalk, which can perpetuate a common perception of homelessness. Would encourage author to consider images representing a wider range of experiences of a social phenomena. Content advisories are used for each section, which is not necessarily cultural relevance but is respectful and recognizes the diversity of experiences and triggers that the readers may have.

Overall, I was very impressed and encouraged with the well organized content and thoughtful flow of this important textbook for social work students and instructors. The length and readability of each chapter would likely be appreciated by instructors as well as students, increasing the extent that the learning outcomes would be achieved. Teaching research is very challenging because the content and application can feel very intimidating. The author also has provided access to supplemental resources such as presentations and assignments.

Reviewed by elaine gatewood, Adjunct Faculty, Bridgewater State University on 6/15/21

The book provides concrete and clear information on using research as consumers, It provides a comprehensive review of each step to take to develop a research project from beginning to completion, with examples. read more

The book provides concrete and clear information on using research as consumers, It provides a comprehensive review of each step to take to develop a research project from beginning to completion, with examples.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

From my perspective, content is highly accurate in the field of learning research method and unbiased. It's all there!

The content is highly relevant and up-to-date in the field. The book is written and arranged in a way that its easy to follow along with adding updates.

The book is written in clear and concise. The book provides appropriate context for any jargon/technical terminology used along with examples which readers are able to follow along and understand.

The contents of the book flow quite well. The framework in the book is consistent.

The text appears easily adaptable for readers and the author also provides accompanying PowerPoint presentations; these are a good foundation tools for readers to use and implement.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The contents of the book flow very well. Readers would be able to put into practice the key reading strategies shared in the book ) because its organization is laid out nicely

Interface rating: 3

The interface is generally good, but I was only able to download the .pdf. This may present issues for some student readers.

There are no grammatical errors.

The text was culturally relevant and provided diverse research and practice examples. The text could have benefited from sexamples of intersectional and anti-oppressive lenses for students to consider in their practice.

This text is a comprehensive introduction to research that can be easily adapted for a BSW/MSW research course.

Reviewed by Taylor Hall, Assistant Professor, Bridgewater State University on 6/30/20

This text is more comprehensive than the text I currently use in my Research Methods in Social Work course, which students have to pay for. This text not only covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods, but also all parts of the... read more

This text is more comprehensive than the text I currently use in my Research Methods in Social Work course, which students have to pay for. This text not only covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods, but also all parts of the research process from thinking about research ideas to questions all the way to evaluation after social work programs/policies have been employed.

Not much to say here- with research methods, things are black and white; it is or isn't. This content is accurate. I also like to way the content is explained in light of social work values and ethics. This is something our students can struggle with, and this is helpful in terms of showing why social work needs to pay attention to research.

There are upcoming changes to CSWE's competencies, therefore lots of text materials are going to need to be updated soon. Otherwise, case examples are pertinent and timely.

Clarity rating: 4

I think that research methods for social workers is a difficult field of study. Many go into the field to be clinicians, and few understand (off the bat) the importance of understanding methods of research. I think this textbook makes it clear to me, but hard to rate a 5 as I know from a student's perspective, lots of the terminology is so new.

Appears to be so- I was able to follow, seems consistent.

Yes- and I think this is a strong point of this text. This was easy to follow and read, and I could see myself easily divvying up different sections for students to work on in groups.

Yes- makes sense to me and the way I teach this course. I like the 30,000 ft view then honing in on specific types of research, all along the way explaining the different pieces of the research process and in writing a research paper.

I sometimes struggle with online platforms versus in person texts to read, and this OER is visually appealing- there is not too much text on the pages, it is spaced in a way that makes it easier to read. Colors are used well to highlight pertinent information.

Not something I found in this text.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

This is a place where I feel the text could use some work. A nod to past wrongdoings in research methods on oppressed groups, and more of a discussion on social work's role in social justice with an eye towards righting the wrongs of the past. Updated language re: person first language, more diverse examples, etc.

This is a very useful text, and I am going to recommend my department check it out for future use, especially as many of our students are first gen and working class and would love to save money on textbooks where possible.

Reviewed by Olubunmi Oyewuwo-Gassikia, Assistant Professor, Northeastern Illinois University on 5/5/20

This text is an appropriate and comprehensive introduction to research methods for BSW students. It guides the reader through each stage of the research project, including identifying a research question, conducting and writing a literature... read more

This text is an appropriate and comprehensive introduction to research methods for BSW students. It guides the reader through each stage of the research project, including identifying a research question, conducting and writing a literature review, research ethics, theory, research design, methodology, sampling, and dissemination. The author explains complex concepts - such as paradigms, epistemology, and ontology - in clear, simple terms and through the use of practical, social work examples for the reader. I especially appreciated the balanced attention to quantitative and qualitative methods, including the explanation of data collection and basic analysis techniques for both. The text could benefit from the inclusion of an explanation of research design notations.

The text is accurate and unbiased. Additionally, the author effectively incorporates referenced sources, including sources one can use for further learning.

The content is relevant and timely. The author incorporates real, recent research examples that reflects the applicability of research at each level of social practice (micro, meso, and macro) throughout the text. The text will benefit from regular updates in research examples.

The text is written in a clear, approachable manner. The chapters are a reasonable length without sacrificing appropriate depth into the subject manner.

The text is consistent throughout. The author is effective in reintroducing previously explained terms from previous chapters.

The text appears easily adaptable. The instructions provided by the author on how to adapt the text for one's course are helpful to one who would like to use the text but not in its entirety. The author also provides accompanying PowerPoint presentations; these are a good foundation but will likely require tailoring based on the teaching style of the instructor.

Generally, the text flows well. However, chapter 5 (Ethics) should come earlier, preferably before chapter 3 (Reviewing & Evaluating the Literature). It is important that students understand research ethics as ethical concerns are an important aspect of evaluating the quality of research studies. Chapter 15 (Real-World Research) should also come earlier in the text, most suitably before or after chapter 7 (Design and Causality).

The interface is generally good, but I was only able to download the .pdf. The setup of the .pdf is difficult to navigate, especially if one wants to jump from chapter to chapter. This may present issues for the student reader.

The text was culturally relevant and provided diverse research and practice examples. The text could have benefited from more critical research examples, such as examples of research studies that incorporate intersectional and anti-oppressive lenses.

This text is a comprehensive introduction to research that can be easily adapted for a BSW level research course.

Reviewed by Smita Dewan, Assistant Professor, New York City College of Technology, Department of Human Services on 12/6/19

This is a very good introductory research methodology textbook for undergraduate students of social work or human services. For students who might be intimidated by social research, the text provides assurance that by learning basic concepts of... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This is a very good introductory research methodology textbook for undergraduate students of social work or human services. For students who might be intimidated by social research, the text provides assurance that by learning basic concepts of research methodology, students will be better scholars and social work or human service practitioners. The content and flow of the text book supports a basic assignment of most research methodology courses which is to develop a research proposal or a research project. Each stage of research is explained well with many examples from social work practice that has the potential to keep the student engaged.

The glossary at the end of each chapter is very comprehensive but does not include the page number/s where the content is located. The glossary at the end of the book also lacks page numbers which might make it cumbersome for students seeking a quick reference.

The content is accurate and unbiased. Suggested exercises and prompts for students to engage in critical thinking and to identify biases in research that informs practice may help students understand the complexities of social research.

Content is up-to-date and concepts of research methodology presented is unlikely to be obsolete in the coming years. However, recent trends in research such as data mining, using algorithms for social policy and practice implications, privacy concerns, role of social media are topics that could be considered for inclusion in the forthcoming editions.

Content is presented very clearly for undergraduate students. Key takeaways and glossary for each section of the chapter is very useful for students.

Presentation of content, format and organization is consistent throughout the book.

Subsections within each chapter is very helpful for the students who might be assigned readings just in parts for the class.

Students would benefit from reading about research ethics right after the introductory chapter. I would also move Chapter 8 to right after the literature review which might inform creating and refining the research question. Content on evaluation research could also be moved up to follow the chapter on experimental designs. Regardless of the organization, the course instructors can assign chapters according to the course requirements.

PDF version of the book is very easy to use especially as students can save a copy on their computers and do not have to be online. Charts and tables are well presented but some of the images/photographs do not necessarily serve to enhance learning. Image attributions could be provided at the end of the chapter instead of being listed under the glossary. Students might also find it useful to be able to highlight the content and make annotations. This requires that students sign-in. Students should be able to highlight and annotate a downloaded version through Adobe Reader.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

Content is not insensitive or offensive in any way. Supporting examples in chapters are very diverse. Students would benefit from some examples of international research (both positive and negative examples) of protection of human subjects.

Reviewed by Jill Hoffman, Assistant Professor, Portland State University on 10/29/19

This text includes 16 chapters that cover content related to the process of conducting research. From identifying a topic and reviewing the literature, to formulating a question, designing a study, and disseminating findings, the text includes... read more

This text includes 16 chapters that cover content related to the process of conducting research. From identifying a topic and reviewing the literature, to formulating a question, designing a study, and disseminating findings, the text includes research basics that most other introductory social work research texts include. Content on ethics, theory, and to a lesser extent evaluation, single-subject design, and action research are also included. There is a glossary at the end of the text that includes information on the location of the terms. There is a practice behaviors index, but not an index in the traditional sense. If using the text electronically, search functions make it easy to find necessary information despite not having an index. If using a printed version, this would be more difficult. The text includes examples to illustrate concepts that are relevant to settings in which social workers might work. As most other introductory social work research texts, this book appears to come from a mainly positivist view. I would have appreciated more of a discussion related to power, privilege, and oppression and the role these play in the research topics that get studied and who benefits, along with anti-oppressive research. Related to evaluations, a quick mention of logic models would be helpful.

The information appears to be accurate and error free. The language in the text seems to emphasize "right/wrong" choices/decisions instead of highlighting the complexities of research and practice. Using gender-neutral pronouns would also make the language more inclusive.

Content appears to be up-to-date and relevant. Any updating would be straightforward to carry out. I found at least one link that did not work (e.g., NREPP) so if you use this text it will be important to check and make sure things are updated.

The content is clearly written, using examples to illustrate various concepts. I appreciated prompts for questions throughout each chapter in order to engage students in the content. Key terms are bolded, which helps to easily identify important points.

Information is presented in a consistent manner throughout the text.

Each chapter is divided into subsections that help with readability. It is easy to pick and choose various pieces of the text for your course if you're not using the entire thing.

There are many ways you can organize a social work research text. Personally, I prefer to talk about ethics and theory early on, so that students have this as a framework as they read about other's studies and design their own. In the case of this text, I'd put those two chapters right after chapter 1. As others have suggested, I'd also move up the content on research questions, perhaps after chapter 4.

In the online version, no significant interface issues arose. The only thing that would be helpful is to have chapter titles clearly presented when navigating through the text in the online version. For example, when you click through to a new chapter, the title simply says "6.0 Chapter introduction." In order to see the chapter title you have to click into the contents tab. Not a huge issue but could help with navigating the online version. In the pdf version, the links in the table of contents allowed me to navigate through to various sections. I did notice that some of the external links were not complete (e.g., on page 290, the URL is linked as "http://baby-").

Cultural representation in the text is similar to many other introductory social work research texts. There's more of an emphasis on white, western, cis-gendered individuals, particularly in the images. In examples, it appeared that only male/female pronouns were used.

Reviewed by Monica Roth Day, Associate Professor, Social Work, Metropolitan State University (Saint Paul, Minnesota) on 12/26/18

The book provides concrete and clear information on using research as consumers, then developing research as producers of knowledge. It provides a comprehensive review of each step to take to develop a research project from beginning to... read more

The book provides concrete and clear information on using research as consumers, then developing research as producers of knowledge. It provides a comprehensive review of each step to take to develop a research project from beginning to completion, with appropriate examples. More specific social work links would be helpful as students learn more about the field and the uses of research.

The book is accurate and communicates information and largely without bias. Numerous examples are provided from varied sources, which are then used to discuss potential for bias in research. The addition of critical race theory concepts would add to this discussion, to ground students in the importance of understanding implicit bias as researchers and ways to develop their own awareness.

The book is highly relevant. It provides historical and current examples of research which communicate concepts using accessible language that is current to social work. The text is written so that updates should be easy. Links need to be updated on a regular basis.

The book is accessible for students at it uses common language to communicate concepts while helping students build their research vocabulary. Terminology is communicate both within the text and in glossaries, and technical terms are minimally used.

The book is consistent in its use of terminology and framework. It follows a pattern of development, from consuming research to producing research. The steps are predictable and walk students through appropriate actions to take.

The book is easily readable. Each chapter is divided in sections that are easy to navigate and understand. Pictures and tables are used to support text.

Chapters are in logical order and follow a common pattern.

When reading the book online, the text was largely free of interface issues. As a PDF, there were issues with formatting. Be aware that students who may wish to download the book into a Kindle or other book reader may experience issues.

The text was grammatically correct with no misspellings.