- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

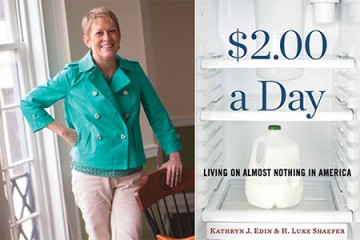

Kathryn Edin reveals the lives of people who live on $2 a day

Credit: Mark Smith

By Dale Keiger

Kathryn Edin has been an itinerant scholar of the poor for more than 20 years. She is a sociologist who works like an anthropologist, melding numbers and narrative to examine in illuminating detail the lives of poor people all over the United States. She has worked in Austin, Texas; Baltimore; Boston; Charleston, South Carolina; Camden, New Jersey; Chicago; Cleveland; Dallas; Milwaukee; New York; Philadelphia; and San Antonio; as well as Appalachian Tennessee and the Mississippi Delta. Her book titles signal where she has focused her effort: Making Ends Meet: How Single Mothers Survive Welfare and Low-Wage Work ; Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City ; and Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage .

Image caption:

Image credit : Matt Roth

In the summer of 2010, Edin was in the seventh year of a long-term study of children born in public housing in the early 1990s. At Latrobe Homes, a 700-unit housing project in East Baltimore, she encountered the 19-year-old woman she calls Ashley. "She had a two-week-old baby," Edin recalls. "When we walked into the house, the first thing I noticed was that as she was rocking her baby, she wasn't adequately supporting the head, and as a mother you know something's wrong. She just looked depressed, no expression on her face. She was visibly unkempt." Edin was sitting on the kitchen floor while she interviewed Ashley—there was only one chair—and she could look up and see there was no food in any of the cabinets. Despite six people living in the unit—Ashley, her baby, her mother, her brother, an elderly uncle, and a young cousin—there was almost no furniture. Edin noted a table with three legs that wouldn't stay upright unless propped against a wall, a filthy mattress with a Bugs Bunny fitted sheet, and a couch. The elderly uncle was on the couch nodding over in a heroin daze. Edin had witnessed plenty of poverty in her career, but not this bad. She knew from Ashley that no one in the household had a job, nor was anyone receiving public cash assistance. This was a family with no income. Edin recalls: "My first thought was that we'd found a whole new kind of poverty that we didn't think existed, and I wondered what was going on."

Since 2014, Edin has been a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in the Krieger and Bloomberg schools, and recently she became director of the 21st Century Cities Initiative, one of the signature initiatives of the Johns Hopkins Rising to the Challenge capital campaign. But when she came across Ashley, Edin was on the faculty of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. A young visiting professor named Luke Shaefer had recently arrived at Harvard, and he was expert at mining a government data set that social scientists refer to as "the SIPP," the Survey of Income and Program Participation compiled by the United States Census Bureau. The SIPP captured more of the income of the poor than any other representative survey. "I told him about Ashley," she says, "and I said, 'Let's work out something together. Let's figure out if this is a thing.'"

It was a thing. The SIPP polls about 40,000 households all over the United States regarding any source of cash income they have had in the previous four months, including government assistance. The data indicated to Shaefer and Edin that in any given month, 1.5 million families, including 3 million children, were surviving on cash incomes of no more than $2 per person per day. More than a third of these families were headed by a married couple. Nearly half were poor whites. Shaefer says, "I can picture in my head that very first readout of the data. I was sitting in the main Harvard library reading room. I hadn't really known what to make of what Kathy said she was seeing, and then out pops this output. I was just wowed by it. I said a couple of words I'm pretty sure cannot appear in your magazine."

For comparison, the official U.S. government poverty line for a family of three in 2015 is $20,090 in income per year; that works out to a bit more than $18 a day per person. About half of the 1.5 million families in Shaefer's data were receiving food assistance by way of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, the equivalent of what used to be called food stamps. Many had lived for a time in shelters or various precarious arrangements with kin, friends, or acquaintances, and had found other forms of help including public health insurance for their children. So they were not solely dependent on $2 a day for survival. But the United States has a cash economy. You cannot buy shoes for your children or pay the electric bill or take a bus to a job interview without money. How on earth were more than 4 million people living on no income? "In Ghana, where 80 percent of the economy is barter and noncash, it's one thing to live on $2 in cash per person per day," Edin says. "What does it mean to live cashless in the world's most advanced capitalist country?"

Shaefer and Edin were so startled by the numbers that they first tried to refute them. "One thing I don't think outsiders recognize about scientists is how hard we work to prove ourselves wrong," Edin says. They dug into other data sets, like public school reports on the number of homeless children in classrooms and the annual rolls of government food assistance, which record how many families report no cash income. They were looking for results at odds with what Shaefer had found in the SIPP. But everywhere they looked they found only corroboration. "The Census Bureau didn't believe us and chose to rerun our numbers," Edin says. "They got the exact same results."

So Edin and Shaefer crunched economic data to find 18 statistically representative families who had recently experienced at least three months of cashless poverty. Then, in 2012, Edin and a team of research assistants began documenting the daily lives of those families, to understand how they survived on so little and what their lives were like. The results were published in $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015). The volume includes enough history of welfare in the United States to explain how the country got to this point, plus some policy suggestions for going forward. But the heart of the book is the narrative material that vividly conveys what it means to find yourself so disconnected from the economic system.

Politicians and commentators who favor restricting welfare benefits often portray poor people as a segment of the population that has fallen into poverty through a lack of initiative or personal responsibility, or who prefer public handouts to working for a living. To the contrary, the people Edin studied embody what Americans like to think are the cardinal virtues of upstanding citizens. They are resourceful, inventive, thrifty, and not just willing to work but eager to work. They seize every opportunity for employment and want nothing as badly as they want stable, full-time jobs. But they have fallen out of the 21st-century U.S. economy at a time when there is little in the way of a net to catch them, and they face overwhelming obstacles to clawing their way back up. And there aren't a handful of them. There are millions.

For $2.00 a Day , Edin studied families in four locales that Shaefer's quantitative research told her would be representative of the larger picture. For a typical, prosperous major American city, she picked Chicago. For a once booming city now enduring a long downturn, she selected Cleveland. Analysis of the SIPP data turned up clusters of extreme poverty in Appalachia and the Deep South, which sent her team to families in Johnson City, Tennessee, which had experienced something of a resurgence, and the rural Mississippi Delta, which had been impoverished for decades. "Our initial analysis raised more questions than answers," she says. "Who are these people? How did they get into this situation? What were they actually doing to survive? Obviously, they couldn't really be living on just $2 a day."

Edin found that life in this kind of deprivation is complex, unstable, physically and psychologically punishing, and contingent upon small day-to-day events that could put someone out of work, out of shelter, and out of luck in the space of a week. Start with finding work. To interview for a job requires a clean, decent set of clothes and the opportunity to bathe; both can be problematic for anyone living in a shelter or in a relative's apartment with six other people. Unless the job seeker has the luck to be close enough to walk to the interview, he'll need access to a car or money for the bus. Few businesses hire anyone on the spot, so the applicant will also need a $30 refurbished, pay-as-you-go cellphone for callbacks. (Sociologists often note that it's expensive to be poor.)

If the person does get a job, it will probably be in the service sector for minimum or sub-minimum wage. Many employers, like big-box stores, chain restaurants, and coffee shops, have adopted computerized systems that allow them to adjust their workforces day by day in response to changes in customer flow, the effects of sales events, seasonal fluctuations in business, even changes in the weather. So anyone holding down an entry-level job with one of these businesses is unlikely to have a dependable, steady, 40-hour-a-week work schedule that allows him to plan for all the other quotidian stuff that demands time and attention. He may be called in for 12-hour shifts over three straight days, or a couple of 16-hour open-to-close shifts at a coffee shop, then work only 10 hours all the next week. He may find his hours zeroed out, which means he is still technically employed but will have no income for that week. If he can't be flexible enough to accommodate the employer, he will lose the job because there is no shortage of people desperate for work who will take his place. If a parent needs time off because her child is sick or she needs to meet with the child's teacher or the car has broken down, forget it. In these jobs no one gets sick days or personal days or vacation.

The instability of work will be matched by instability in every other aspect of life for the poor. They may qualify for subsidized housing but are unlikely to get it since the wait list in many places is tens of thousands of people long and frequently closed. They may have enough money for a ramshackle apartment, but that will require regular income for rent, as well as for the electric and water bills. Losing a job or even a week's worth of hours can mean losing the apartment and having to resort to a shelter or a room in someone's house, and the people who take them in might well live in precarious situations of their own, not to mention three bus lines and two hours from that precious job. Children might have to spend six months in a house with relatives or strangers who have drug problems or are physically abusive. To be this poor means being vulnerable to every sort of predator.

In $2.00 a Day , the reader meets several people who live like this. Jennifer Hernandez (to respect their privacy rights and abide by institutional review board rules for the research, Edin created pseudonyms for everyone in the book) and her two children moved from one homeless shelter to another in Chicago. In the two and a half months spent at the third of those shelters, she applied for more than 100 jobs before landing one with a custodial company that cleaned foreclosed houses, many of which had been broken into and trashed by squatters and junkies. Working in filthy, unheated rooms during a Chicago winter, she kept coming down with respiratory problems and viral infections that she took home to her children, which led to missed work when they were home sick, which resulted in her hours being cut back so much she had to look for another job. But even at the worst times, she would not register for welfare benefits. Welfare was a handout and she would have none of that.

Modonna Harris, also in Chicago, had a high school diploma, two years of college, and a child from a broken marriage. For eight years, she held a full-time, $9-an-hour job at a music store but was summarily fired one day when her cash drawer came up $10 short. She then fell behind in her rent, was evicted, and had to move in with a succession of relatives who would shelter her and her daughter, Brianna, for only a few months at a time before turning them back out. Brianna still managed to make her school's honor roll one term. When food was in short supply, Modonna would turn a cup of coffee into "breakfast" by dumping in as much cream and sugar as the mug would hold.

There was Rae McCormick in Cleveland, whose mother abandoned her soon after her father died. At age 12, she lived for a time on her own, sheltered by a sympathetic landlord who let her stay in an apartment rent-free. By 21 she had a daughter to support and the deteriorating health of a much older person. Nevertheless, she managed to secure a full-time job with Walmart and in her first six months was named "cashier of the month" twice and encouraged to apply for promotion. Then one day she could not drive to work because the family friend whose truck she borrowed had run it out of gas and she had no cash to buy more. Her boss told her not to bother coming in anymore. Soon she spiraled down to $2-a-day poverty.

There's Paul in Cleveland who lost his house and savings when his chain of pizza parlors went bust. Martha in Mississippi who sold Kool-Aid pops and, on special occasions, a homemade delicacy, Kool-Aid Pickles, out of her living room for 50 cents apiece. Jessica Compton, a skinny, worried 21-year-old in Johnson City who sold her plasma twice a week because she had two kids and Red Lobster and McDonald's had zeroed out her and her husband's work hours when the seasonal economy slowed. They were three months behind in their rent and expected to be evicted any day, and she lived in terror that her iron levels would be too low for her to donate and receive the desperately needed $30 she collected for each plasma donation.

When the people Edin studied saw no other way, they sometimes broke the law to obtain cash. A woman might have "a friend" who would pay the electric bill one month in exchange for sex. The food assistance program, SNAP, is an in-kind benefit, a debit card that can be used only to purchase food. So the extremely poor sometimes traded $100 of SNAP groceries to a neighbor or family member for $60 in cash. This was risky; under federal sentencing guidelines, penalties for food stamp fraud are more severe than for voluntary manslaughter, aggravated assault with a firearm, or sexual contact with a child under 12. One woman studied by Edin in the Mississippi Delta sold her three children's Social Security numbers for $500 each to family members, who then claimed the children as dependents so they could collect tax refunds.

The researchers were meticulous about documenting their subjects' lives and corroborating what they reported. Nearly every interview was transcribed (they had to rely on fact-checked field notes once when the recorder malfunctioned) and every transcript coded. Whenever they could, the researchers found multiple sources to confirm what their subjects reported about their communities and work environments and schools. "We have a saying, 'Hearsay is not evidence,'" Edin says. "We get as close to the source as we can. You can never be sure—someone can always be lying to you. But for every claim that was made in this study, there were multiple verifications. The best fact-checking we do is staying with people for a long time."

Edin's exposure to poor people came early. She grew up in northern Minnesota on the boundary of two economically depressed counties. Her father ran the local technical college, so her family was middle class, but the poor were all around her and a routine part of her childhood. Her mother held a degree in parish work and did church-based social work on behalf of the small Evangelical Covenant church the family belonged to, driving all over in a van with Edin in the back. "She was the youth leader, and man, there was no youth that didn't get a knock on the door," Edin says. "I spent a lot of time hanging out with kids at the very bottom of the income distribution. I thought it was fascinating, and I thought it was normal to have your mother running around the county treating everyone like they mattered."

After earning an undergraduate degree at tiny North Park College (now North Park University) in Chicago, Edin enrolled at Northwestern University for graduate study in sociology. "You went to Northwestern to do one of two things. You either went to study with the great quantitative mastermind Christopher Jencks, or you went and studied with the qualitative guru Howard Becker." She cultivated both as mentors and absorbed their different methodologies. "Howie's approach was to go out to a place where you could find a lot of the people you were studying and just hang out with them. Jencks was concerned with things like sampling and gathering numbers. Howie would have me out at laundromats meeting welfare moms. But Jencks got me to systematically sample across Chicago so that I had no more than three respondents from any given social network and could claim some level of representativeness."

While she was at Northwestern, she taught in a church basement as part of a North Park program that brought college courses to poor people. "After class, we would just sit around and talk," she says. "I would relay things that I was learning in Jencks' poverty class and then these women would say, 'Oh, girl, that's not how it works at all. This is how it really works.' So one day we started talking about welfare, and they said, 'Girl, don't you know that everybody has to cheat to survive? Welfare doesn't pay enough.'" This was the seed for Edin's first book, Making Ends Meet , written with anthropologist Laura Lein. "We showed, after six years in four cities and multiple interviews with 400 low-income single mothers, that you couldn't live on welfare alone anywhere in the country. You actually had to work under the table to survive." Most people without work did not have sufficient welfare benefits to get by, but when they had work and reported the income, they lost benefits. Either way they came up short. The only solution was to earn money by whatever means but not tell the government about it.

Edin developed what became her signature approach to sociology: rigorous data mining to determine subjects for her to study in the manner of an anthropologist doing field work. For one project, she and colleague Paula England followed 75 couples for four years, amassing 75,000 pages of transcripts. The research for Making Ends Meet began with a study of census data to select cities that represented the range of labor markets and welfare systems around the country. Edin then spent six years interviewing welfare mothers and reporting the narratives that recorded the texture of their lives. The study's firm foundation in data was exemplified by the back of the book, which included 27 regression analyses, a technique for examining statistical variables and their relationships. The quantitative work applied social science rigor to the research so that it produced something more than a collection of vivid narratives, something scientifically meaningful that could also drive social policy. The narratives revealed the lives within the data. Her Johns Hopkins colleague, sociologist Andrew Cherlin, observes, "Kathy thinks like a sociologist and talks like an anthropologist."

One chapter of $2.00 a Day explicates the changes in welfare that did benefit many people but sent millions more spiraling into extreme poverty. In 1996, Congress passed and Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which was promoted as sweeping welfare reform aimed at getting people off cash assistance and into jobs. It replaced open-ended cash assistance with a severely time-limited cash program and the requirement that all able-bodied recipients had to work. Those fortunate enough to have work qualified for the Earned Income Tax Credit. The EITC was cash assistance but in the form of an annual tax credit for people employed in low-income jobs. The more money they earned, up to a point, the bigger the credit, and the annual supplement could be upward of $5,000, a major boost to poor families. But if you didn't have a job, you didn't qualify. So under the new law, people who arguably needed cash the most—the unemployed, who had to pay for shelter and utilities and clothes and transportation and other necessities but had zero income—no longer qualified to receive any cash once they had run out their brief eligibility.

The legislation was popular with voters because it encouraged work and all but did away with what they regarded as handouts. Opinion polls consistently indicate that the majority of Americans approve of helping the poor, but not if that help comes in the form of a welfare check. Peter Edelman is a law professor at Georgetown University and faculty director of the Center on Poverty and Inequality there; he resigned from the Clinton administration in protest when the president signed the 1996 law. He says, "If you ask the public, 'Do you favor education for low-income children?' they say yes. 'Do you think there ought to be help for low-income people for better health?' Yes. 'Help with hunger?' Yes. 'Housing?' Yes. But when you suggest just giving the poor money, the public has a different attitude. They regard that as giving something for nothing." Says Edin, "In America, work is about citizenship. You can't be a citizen if you're not a worker."

The reform worked for some people. In 1993, only 58 percent of low-income mothers were employed; by 2000, that figure had risen to nearly 75 percent. Child poverty rates fell four straight years after passage of the law. The EITC tax credits meant a great deal to those able to find and keep jobs. "The more you worked, the more you got, and that made them feel a great deal of pride," Edin says, "whereas welfare had the opposite effect, making them feel shamed and stigmatized. This citizenship-enhancing feature of the EITC is like policy magic. This is probably the best policy we've ever invented for poor people. Except it leaves out our people"—the people in $2.00 a Day —"because they don't have enough work to claim anything. They are working when they can, but they're at the ragged edge of the labor market. It's like hanging on to a rope that's dissolving in your hands."

The 1996 law, Edin points out, was based on the assumption that hundreds of thousands of people dropped from the old welfare rolls could find stable, full-time employment that paid living wages. And when the legislation was enacted, the economy was booming. What was not well-enough understood was that too many of the jobs provided by the labor market, especially for the uneducated and unskilled, were low-wage and unstable, and there were not enough of them to meet demand. The recession that began in 2008 further reduced the number of available jobs. In her book, Edin describes this as the "toxic alchemy" that pushed so many people into the deepest poverty. By the mid-2000s, one in five single mothers had become what sociologists call "disconnected"—neither working nor receiving welfare. During her research, Edin was struck by how many people had not even bothered to apply for benefits they were qualified to receive. They assumed, or had been told, that the system offered them nothing and they were on their own. And some simply refused to seek public assistance. "The key thing about these people is they see themselves as workers, not dependents," Edin stresses. "We know from the SIPP that only 10 percent of these families get a dime from cash benefits."

All the people she studied during the course of her research repeatedly sought work and took it whenever they could. Recall Ashley, the 19-year-old Baltimorean with the 2-week-old baby who first got Edin wondering about the poorest of the poor. As part of the protocol for the study that had brought her and Edin together, Edin paid Ashley $50 for the interview. The next day, Edin found pretext to go back and see her again because she was so worried by what she'd seen of how Ashley was interacting with her baby. When the young woman answered the door this time, Edin says she was transformed. She had placed the baby with her mother for the day, had used some of the $50 to get her hair permed and buy a pants suit at Goodwill to make herself presentable for job interviews, and was on her way out the door to look for work. Edin remembers her as utterly changed by the mere possibility of finding a job.

With Cherlin and fellow Johns Hopkins sociologist Stephanie De Luca, economist Robert Moffitt, and researchers from the schools of Medicine and Public Health, Edin has embarked on a yearlong project to plan a major multidisciplinary study of the extreme poor, a project that will be the first of its kind. She has kept in touch with most of the 18 families she studied for $2.00 a Day . "None of our families are doing appreciably better than when we first met them," she says. "Our hypothesis, that remains to be tested, is that once you find yourself in one of these spells, the work of survival becomes so all-consuming, and the wear of physically living in this condition becomes so acute, you can't really get out of it."

There seems to be little public support for a retooling of the welfare system sufficient to help the extreme poor. Part of the problem may be that to most of the American public, they are invisible. Before the work by Edin, Shaefer, and the rest of their team, these 4 million people were invisible even to sociologists. Says Cherlin, "In retrospect, I should have known—we all should have known—that the constriction of the welfare program would create families like this. But we didn't." In $2.00 a Day , Edin says, Here they are. These are their lives. And the question for Americans, she says, is this: "Does this look like the America you want to live in?"

In 1996, when Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York argued against the welfare reform legislation, he predicted the changes to the country's social safety net would produce a million children sleeping on heating grates. "What we found is that over the course of a year, 3.4 million children are experiencing at least three months of extreme poverty," Edin says. "They aren't as visible as Moynihan thought they would be. But they are three and a half times more numerous."

Dale Keiger, A&S '11 (MLA), is the magazine's editor.

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged sociology , kathryn edin

Related Content

Stories of extreme poverty

A notable read

You might also like, news network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

Advertisement

Supported by

‘$2.00 a Day,’ by Kathryn J. Edin and H. Luke Shaefer

- Share full article

By William Julius Wilson

- Sept. 2, 2015

From the late 1960s to the mid-1990s, a number of developments turned out to have profound effects on destitute families in the United States, which Kathryn J. Edin and H. Luke Shaefer’s “$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America” brings into sharp relief. Critics of welfare repeatedly argued that the increase of unwed mothers was mainly due to rising rates of welfare payments through Aid to Families With Dependent Children (A.F.D.C.). Even though the scientific evidence offered little support for this claim, the public’s outrage against the program, fueled by the “welfare queen” stereotype that Ronald Reagan peddled in stump speeches during his 1976 run for the presidency, led to calls for a major revamping of the welfare system.

In 1993, Bill Clinton and his advisers began a discussion of welfare reform that was designed to “make work pay,” a phrase coined by the Harvard economist David Ellwood in his 1988 book “Poor Support.” Ellwood, one of Clinton’s advisers, argued that to ease the transition from welfare to work, it would be necessary to provide training and job placement assistance; to help local government create public-sector jobs when private-sector jobs were lacking; and to develop child care programs for working parents. President Clinton’s early welfare-reform proposal included these features, as well as another component that Ellwood submitted — time limits on the receipt of welfare once these provisions were in place.

Republicans, however, seizing control of Congress in 1994, devised a bill that reflected their own vision of welfare reform. Designed as a block grant, giving states considerably more latitude in how they spent government money for welfare than A.F.D.C. permitted, the Republican bill also included a five-year lifetime limit on benefits based on federal funds. States were allowed to impose even shorter time limits. Although the bill increased child care subsidies for recipients who found jobs, the all-important public-sector jobs for those unable to find employment in the private sector were missing. Moreover, there wasn’t enough budgeted for education and training. Much to the chagrin of the bill’s critics — including Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who predicted in 1995 that the proposed legislation would lead to poor children “sleeping on grates” — President Clinton signed the bill, called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), on Aug. 22, 1996, two days after his signing into law the first increase in the federal minimum wage in five years.

In the immediate years following the passing of welfare reform, supporters of TANF argued that Moynihan and other critics were proved wrong. The number of single mothers who exited welfare and found work exceeded all expectations; child poverty rates fell; the expansion of the earned-income tax credit, a wage subsidy for the working poor, combined with the 1996 increase in the minimum wage and the additional availability of dollars for child care (as long as the parents were employed), boosted government provisions for working-poor families.

Timing, though, had something to do with the apparent success of welfare reform. The tight labor market during the economic boom of the late 1990s significantly lowered unemployment at the very time that TANF was being implemented. Besides, despite improvements for the working poor, studies revealed that the number of “disconnected” single mothers — neither working nor on welfare — had grown substantially since the passage of TANF, rising to one in five single mothers during the mid-2000s. This is the group featured in “$2.00 a Day,” a remarkable book that could very well change the way we think about extreme poverty in the United States.

When Edin returned to the field in the summer of 2010 to update her earlier work on poor mothers, she was surprised to find a number of families struggling “with no visible means of cash income from any source.” To ascertain whether her observations reflected a greater reality, Edin turned to Shaefer, a University of Michigan expert on the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation, who was visiting Harvard for a semester while she was a faculty member. (Edin and I served on three dissertation committees together; she is now a professor at Johns Hopkins.) Shaefer analyzed the census data, which is based on annual interviews with tens of thousands of American households, to determine the growth of the virtually cashless poor since welfare reform. His results were shocking: Since the passage of TANF in 1996, the number of families living in $2-a-day poverty had more than doubled, reaching 1.5 million households in early 2011. Edin and Shaefer found additional evidence for the rise of such poverty in reports from the nation’s food banks and government data on families receiving food stamps, now called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and in accounts from the nation’s schools on the rising numbers of homeless children.

In the summer of 2012, the authors also began ethnographic studies in sites across the country: Chicago, Cleveland, a midsize city in the Appalachian region and small rural villages in the Mississippi Delta. In each of these areas it did not prove difficult to find families surviving on cash incomes of no more than $2 per person, per day during certain periods of the year.

Edin and Shaefer’s field research provides plausible reasons for the sharp rise in destitute families. The first has to do with the “perilous world of low-wage work.” The mechanization of agriculture has wiped out a lot of jobs in the Mississippi Delta, and even in cities like Chicago, the number of applicants for entry-level work in the service and retail industries far exceeds the number of available positions: “Companies such as Walmart might have hundreds of applicants to choose from” for any one position. Moreover, work schedules are often unpredictable, with abrupt ups and downs in the number of hours a worker gets. Responding to decreasing demand, “employers keep employees on the payroll but reduce their scheduled hours, sometimes even to zero.”

Furthermore, given the glut of applicants, an employer can quickly move to the next person on the list if a job seeker can’t be reached by telephone immediately, which is a real problem for those who live in homeless shelters and lack cellphones. Finally, many applicants who are eligible for TANF aren’t even aware that it is available. The authors meet people who “thought they just weren’t giving it out anymore.”

There are various strategies that the $2-a-day poor use to survive — from taking advantage of public libraries, food pantries and homeless shelters to collecting aluminum cans and donating plasma for cash. Still, in small Delta towns “the nearest food pantry is often miles away, despite the sky-high poverty.” SNAP constitutes the only real safety net program available to the truly destitute — but it cannot be used to pay the rent. “While SNAP may stave off some hardship,” the authors write, “it doesn’t help families exit the trap of extreme destitution like cash might.”

All of the $2-a-day families highlighted by Edin and Shaefer have had to double up with kin and friends at various times because their earnings were insufficient to maintain their own home. Some had to endure verbal, physical and sexual abuse in these dwellings, and the ensuing trauma sometimes precipitated a family’s fall into severe poverty.

This essential book is a call to action, and one hopes it will accomplish what Michael Harrington’s “The Other America” achieved in the 1960s — arousing both the nation’s consciousness and conscience about the plight of a growing number of invisible citizens. The rise of such absolute poverty since the passage of welfare reform belies all the categorical talk about opportunity and the American dream.

$2.00 A DAY

Living on almost nothing in america.

By Kathryn J. Edin and H. Luke Shaefer

210 pp. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. $28.

William Julius Wilson, a professor of sociology and social policy at Harvard, is the author of “More Than Just Race: Being Black and Poor in the Inner City.”

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

How did fan culture take over? And why is it so scary? Justin Taylor’s novel “Reboot” examines the convergence of entertainment , online arcana and conspiracy theory.

Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker unearth botany’s buried history to figure out how our gardens grow.

A new photo book reorients dusty notions of a classic American pastime with a stunning visual celebration of black rodeo.

Two hundred years after his death, this Romantic poet is still worth reading . Here’s what made Lord Byron so great.

Harvard’s recent decision to remove the binding of a notorious volume in its library has thrown fresh light on a shadowy corner of the rare book world.

Bus stations. Traffic stops. Beaches. There’s no telling where you’ll find the next story based in Accra, Ghana’s capital . Peace Adzo Medie shares some of her favorites.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- IPR Intranet

INSTITUTE FOR POLICY RESEARCH

Living on less than $2 a day.

Johns Hopkins sociologist recounts how 'death of welfare' led to rise in extreme poverty

Get all our news

Subscribe to newsletter

Kathryn Edin recounts the day-to-day struggles of the extreme poor, who live on less than $2 a day.

It was opening a refrigerator in a bare, rundown apartment and seeing nothing but a milk carton that provided the inspiration for the cover of Kathryn Edin 's latest book, $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America .

That lone milk carton became symbolic of everything the book was about, said Edin, a Johns Hopkins sociologist and Northwestern alumna (PhD, ’91), in her February 18 IPR Distinguished Public Policy Lecture at Northwestern University.

“Could it be that in the aftermath of welfare reform, a whole new kind of poverty had arisen in the United States—a poverty so deep, we hadn’t even thought to look for it?” she said as she dove into her study of the more than 1.6 million Americans who now live in extreme poverty in “the world’s most advanced capitalistic society.”

Edin recounted the day-to-day struggles of those who live on less than $2 a day—of getting fired because your roommate used all the gas in the car tank so you had no way to get to work, of standing in line to sell your blood plasma twice a week to generate much-needed cash, and of being so hungry that it made you feel “like you want to be dead,” as 18-year-old Tabitha told her, “because it’s peaceful being dead.”

She zeroed in on this extreme poverty in America after spending a summer in Baltimore conducting a study on young people born in public housing. What she saw led her to the larger question of how does one end up in this kind of extreme poverty—and what do you do to survive?

Edin spent part of her early career at Northwestern University, where she was an IPR fellow from 2000–04.

“Her foundation for research was born at both Northwestern and IPR,” said IPR Director David Figlio, an education economist, in introducing her to the 90-plus attendees. “It’s difficult to think of a more important research question than the line of work that Kathy does.”

The 'Death of Welfare'

The book dissects the national data on the larger trend, with statistics from the Survey of Income and Program Participation, but it also recounts what she and her research team, including her co-author H. Luke Shaefer of the University of Michigan, found when they went to Chicago; Cleveland; Johnson City, Tennessee; and two small towns along the Mississippi Delta, seeking out people in extreme poverty and listening to their stories.

The people they met are part of a larger trend: Data shows extreme poverty in the U.S. has increased since the passage of welfare reform in 1996. About 600,000 families with children lived on less than $2 per person per day in 1996, growing to more than 1.6 million families in 2011. Meanwhile, food bank usage has increased and the number of homeless students has risen. The United States has also become the world’s leading supplier of blood plasma, with the donations the only source of cash income for some of the country’s poorest citizens.

Edin pinpoints the “death of welfare” as one cause behind the increase, explaining that welfare has become “a shadow of its former self” since reform.

In 1994, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program served 14.2 million people. Today, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, which replaced the AFDC, serves about 4.1 million people, a drop of 71 percent. The enactment of welfare time limits has contributed to the drop: The 1996 welfare law prohibits states from using federal TANF funds to aid most families for more than 60 months.

The death of welfare may have led more people into poverty, but there are also factors keeping them there, including unsafe work conditions, insufficient work hours, wage theft, and labor law violations.

Edin told the story of a woman who found a job cleaning foreclosed homes in the winter in Chicago. The mold in these homes and the chemicals used for cleaning weakened her immune system, leading to a cycle of illness and missed work. Her employer then branded her unreliable and cut her hours. The woman ended up quitting to find more stable work, but she couldn’t find a new job and ended up homeless.

Those living on less than $2 a day also have to worry about unsafe conditions at home, dealing with housing instability and sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. One woman was “doubling up” with family because she couldn’t afford a place on her own, and she came home from work to find her uncle molesting her 9-year-old daughter.

Pinpointing Potential Solutions

With such a variety of factors contributing to extreme poverty and keeping people from breaking free of its cycle, what can policymakers do?

Edin suggests that there needs to be a cash safety net, because “we can’t completely rely on a work-based safety net.”

“We really do need something to catch people when they fall,” Edin said. “The help for the working poor only applies to them when they are working. When they lose those jobs, they have nothing.”

She highlighted possible solutions such as reviving the welfare system, offering a guaranteed child allowance, or expanding the childcare tax credit. Edin also argued everyone deserves the opportunity to work. Everyone she spoke to said they wanted more work, “Nobody said they wanted more handouts,” she noted.

Most importantly, Edin proposed a litmus test for any proposed reform: “Does it integrate the poor, does it weave them back into society, does it give them honor and dignity? Or does it separate them, shame them, stigmatize them?”

“When we integrate the poor and give them dignity, we have a better chance of getting them out of poverty,” Edin concluded.

Kathryn Edin is Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Sociology and of Population, Family, and Reproductive Health at Johns Hopkins University.

Watch Edin's lecture.

Published: March 29, 2017.

Related Research Stories

Sociologist Alondra Nelson to Deliver Distinguished Policy Lecture at Northwestern

Elizabeth Tipton to Become a 2024 AERA Fellow

Reckoning with the Impossible

inequality.com

The stanford center on poverty and inequality, search form.

- like us on Facebook

- follow us on Twitter

- See us on Youtube

Custom Search 1

- Stanford Basic Income Lab

- Social Mobility Lab

- California Lab

- Social Networks Lab

- Noxious Contracts Lab

- Tax Policy Lab

- Housing & Homelessness Lab

- Early Childhood Lab

- Undergraduate and Graduate Research Fellowships

- Minor in Poverty, Inequality, and Policy

- Certificate in Poverty and Inequality

- America: Unequal (SOC 3)

- Inequality Workshop for Doctoral Students (SOC 341W)

- Postdoctoral Scholars & Research Grants

- Research Partnerships & Technical Assistance

- Conferences

- Pathways Magazine

- Policy Blueprints

- California Poverty Measure Reports

- American Voices Project Research Briefs

- Other Reports and Briefs

- State of the Union Reports

- Multimedia Archive

- Recent Affiliate Publications

- Latest News

- Talks & Events

- California Poverty Measure Data

- American Voices Project Data

- About the Center

- History & Acknowledgments

- Center Personnel

- Stanford University Affiliates

- National & International Affiliates

- Employment & Internship Opportunities

- Graduate & Undergraduate Programs

- Postdoctoral Scholars & Research Grants

- Research Partnerships & Technical Assistance

- Talks & Events

- History & Acknowledgments

- National & International Affiliates

- Get Involved

$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America

Jessica Compton’s family of four would have no cash income unless she donated plasma twice a week at her local donation center in Tennessee. Modonna Harris and her teenage daughter Brianna in Chicago often have no food but spoiled milk on weekends. After two decades of brilliant research on American poverty, Kathryn Edin noticed something she hadn’t seen since the mid-1990s — households surviving on virtually no income. Edin teamed with Luke Shaefer, an expert on calculating incomes of the poor, to discover that the number of American families living on $2.00 per person, per day, has skyrocketed to 1.5 million American households, including about 3 million children. Where do these families live? How did they get so desperately poor? Edin has “turned sociology upside down” (Mother Jones) with her procurement of rich — and truthful — interviews. Through the book’s many compelling profiles, moving and startling answers emerge. The authors illuminate a troubling trend: a low-wage labor market that increasingly fails to deliver a living wage, and a growing but hidden landscape of survival strategies among America’s extreme poor. More than a powerful exposé, $2.00 a Day delivers new evidence and new ideas to our national debate on income inequality.

essica Compton’s family of four would have no cash income unless she donated plasma twice a week at her local donation center in Tennessee. Modonna Harris and her teenage daughter Brianna in Chicago often have no food but spoiled milk on weekends.

After two decades of brilliant research on American poverty, Kathryn Edin noticed something she hadn’t seen since the mid-1990s — households surviving on virtually no income. Edin teamed with Luke Shaefer, an expert on calculating incomes of the poor, to discover that the number of American families living on $2.00 per person, per day, has skyrocketed to 1.5 million American households, including about 3 million children.

Where do these families live? How did they get so desperately poor? Edin has “turned sociology upside down” ( Mother Jones ) with her procurement of rich — and truthful — interviews. Through the book’s many compelling profiles, moving and startling answers emerge.

The authors illuminate a troubling trend: a low-wage labor market that increasingly fails to deliver a living wage, and a growing but hidden landscape of survival strategies among America’s extreme poor. More than a powerful exposé, $2.00 a Day delivers new evidence and new ideas to our national debate on income inequality.

- See more at: http://www.hmhco.com/shop/books/200-a-Day/9780544303188#sthash.U75TC8CS....

A revelatory account of poverty in America so deep that we, as a country, don’t think it exists

Jessica Compton’s family of four would have no cash income unless she donated plasma twice a week at her local donation center in Tennessee. Modonna Harris and her teenage daughter Brianna in Chicago often have no food but spoiled milk on weekends.

Review: What is it like to live on ‘$2.00 a Day’? New book examines deep poverty in the U.S.

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

For “Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage,” Kathryn J. Edin, with coauthor Maria Kefalas, immersed herself in the lives of Philadelphia-area unwed mothers, exploding myths about their choices. She found that many of these women sought children as a source of love and meaning while disdaining marriage to men unable to provide economic stability.

In her latest book, “$2.00 a Day,” she applies the same analytical skills to a harrowing examination of deep poverty in the United States. This time, Edin, professor of sociology and public health at Johns Hopkins University, teams with H. Luke Shaefer, associate professor at the University of Michigan School of Social Work, to report on both historically destitute regions and those suffering more recent economic decline.

Their research, backed by income data, takes them into the homes of severely cash-deprived families in Chicago, Cleveland, the Mississippi Delta and Johnson City, Tenn. We meet a mother bouncing with her daughter from one homeless shelter to the next, desperate for a minimum-wage job; chronically hungry children who live in cramped, fetid houses often lacking heat, electricity or running water; a woman who sells her blood plasma twice a week to pay the bills; and a 10th-grader who opts to trade sex with a gym teacher for food.

They are the soul of this important and heart-rending book, in the tradition of Michael Harrington’s “The Other America” and Alex Kotlowitz’s “There Are No Children Here.” Their skillfully told stories are meant both to inspire empathy and change policy.

Even after the ebbing of the Great Recession, Edin and Shaefer discover that households subsisting virtually without cash income are disconcertingly easy to find. Writing with clear-eyed compassion for these men, women and especially children at society’s margins, they emphasize the extent to which the adults embrace the prototypical American values of hard work and individual responsibility. There is, of course, considerable tragic irony in their subjects’ adherence to American ideals: The labor market and political system have both failed them, and even their distinctly modest versions of the American Dream remain out of reach.

These $2-a-day poor have “had their share of bad luck; they’ve made their share of bad moves; they have other personal liabilities…; and their kin pull them down as often as they lift them up,” the authors write. “Yet,” they add, “jobs in the low-wage labor market can be exceedingly unforgiving,” offering no benefits, irregular schedules, limited hours and little security.

The book’s essential argument is that, in a recession-plagued, post-industrial economy, even low-skill, low-wage jobs can be hard to find and even harder to keep. As a result, policies aimed at ending welfare dependence and helping the working poor, though effective on their face, have been disastrous for many.

While those with consistent work histories have benefited from the expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit and other programs, the less fortunate have fallen through the proverbial safety net. Instead, they turn to everything from selling sex and food stamps to running off-the-books businesses to eke out survival.

For Edin and Shaefer, the original sin that precipitated the current crisis was the end of what President Clinton called “welfare as we know it.” That politically potent rallying cry led to the elimination in 1996 of a program aimed largely at nonworking single mothers, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC. Together with food stamps, Medicaid and subsidized housing, it made subsistence possible. But for some, it also transformed low-wage labor, which entailed child care and other expenses and led to curtailed benefits, into a bad economic choice. The “reform” that replaced it made welfare payments temporary and imposed lifetime limits and work requirements. In the process, it flooded the low-wage labor market and gave employers the whip hand.

Edin and Shaefer don’t want a return to the past — but rather major public works programs, a higher minimum wage and other marketplace fixes. But history and analysis aside, what will likely remain with readers of “$2.00 a Day” are its indelible pseudonymous portraits of families struggling to survive.

It will be hard to forget Jennifer Hernandez, an asthmatic who excels at her janitorial job until she is forced to clean Chicago’s cold and moldy foreclosed houses, sickens from the dank air and gets her hours drastically reduced. Or Cleveland’s Rae McCormick, an ace cashier who is fired after her housemates use all her gas and she is unable to drive to work. Or the Delta’s Tabitha Hicks, who tries to protect her mother from a violent thug who beats her bloody — and is evicted when her mother chooses the thug over her.

Finally, there is college-educated Paul Heckewelder, once a middle-class businessman who owned a chain of pizza parlors that employed many family members. A casualty of the recession, he ends up losing it all and sheltering 22 people in a small house without running water. All are trying to live on his single disability check and the proceeds of his scrap metal recycling.

The diabetic Heckewelder and his hard-luck brood serve as a reminder that economic crisis and need can hit almost anyone, and that these families are not “other” — they are potentially us.

Klein is a cultural reporter and critic and a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review.

$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America

Kathryn J. Edin & H. Luke Shaefer Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: 240 pp., $28

NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote a novel about Sherlock Holmes’ brother (and it’s good!)

Street kids, poverty and fortitude: Photographer Mary Ellen Mark’s stirring last project

L.A. County adds $50 million to funds for fighting homelessness

More to Read

Opinion: I was homeless in college. California can do more for students who sleep in their cars

April 9, 2024

Granderson: College costing nearly $100,000 a year? Forgiving loans is the least we can do

April 8, 2024

Letters to the Editor: Middle class couples aren’t having kids. Blame American politics and inequality

Feb. 23, 2024

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Paul Auster, postmodern author behind ‘The New York Trilogy’ and ‘Smoke,’ dies at 77

The week’s bestselling books, May 5

May 1, 2024

‘Rebel’ redacted: Rebel Wilson’s book chapter on Sacha Baron Cohen struck from some copies

April 25, 2024

$2.00 a day

Living on almost nothing in america, by kathryn edin and h. luke shaefer.

- 11 Want to read

- 3 Currently reading

- 2 Have read

Preview Book

My Reading Lists:

Use this Work

Create a new list

My book notes.

My private notes about this edition:

Check nearby libraries

- Library.link

Buy this book

"A revelatory account of poverty in America so deep that we, as a country, don't think it exists Jessica Compton's family of four would have no cash income unless she donated plasma twice a week at her local donation center in Tennessee. Modonna Harris and her teenage daughter Brianna in Chicago often have no food but spoiled milk on weekends. After two decades of brilliant research on American poverty, Kathryn Edin noticed something she hadn't seen since the mid-1990s -- households surviving on virtually no income. Edin teamed with Luke Shaefer, an expert on calculating incomes of the poor, to discover that the number of American families living on $2.00 per person, per day, has skyrocketed to 1.5 million American households, including about 3 million children. Where do these families live? How did they get so desperately poor? Edin has "turned sociology upside down" (Mother Jones) with her procurement of rich -- and truthful -- interviews. Through the book's many compelling profiles, moving and startling answers emerge. The authors illuminate a troubling trend: a low-wage labor market that increasingly fails to deliver a living wage, and a growing but hidden landscape of survival strategies among America's extreme poor. More than a powerful expose, $2.00 a Day delivers new evidence and new ideas to our national debate on income inequality. "--

Previews available in: English

Showing 1 featured edition. View all 1 editions?

Add another edition?

Book Details

Table of contents, edition notes.

Includes bibliographical references (pages 179-199) and index.

Classifications

The physical object, community reviews (0).

- Created July 19, 2019

- 10 revisions

Wikipedia citation

Copy and paste this code into your Wikipedia page. Need help?

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

$2.00 a Day : Book summary and reviews of $2.00 a Day by Kathryn J. Edin

Summary | Reviews | More Information | More Books

$2.00 a Day

Living on Almost Nothing in America

by Kathryn J. Edin

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' rating:

Published Sep 2015 240 pages Genre: History, Current Affairs and Religion Publication Information

Rate this book

About this book

Book summary.

A revelatory account of poverty in America so deep that we, as a country, don't think it exists Jessica Compton's family of four would have no cash income unless she donated plasma twice a week at her local donation center in Tennessee. Modonna Harris and her teenage daughter Brianna in Chicago often have no food but spoiled milk on weekends. After two decades of brilliant research on American poverty, Kathryn Edin noticed something she hadn't seen since the mid-1990s — households surviving on virtually no income. Edin teamed with Luke Shaefer, an expert on calculating incomes of the poor, to discover that the number of American families living on $2.00 per person, per day, has skyrocketed to 1.5 million American households, including about 3 million children. Where do these families live? How did they get so desperately poor? Edin has "turned sociology upside down" ( Mother Jones ) with her procurement of rich - and truthful - interviews. Through the book's many compelling profiles, moving and startling answers emerge. The authors illuminate a troubling trend: a low-wage labor market that increasingly fails to deliver a living wage, and a growing but hidden landscape of survival strategies among America's extreme poor. More than a powerful exposé, $2.00 a Day delivers new evidence and new ideas to our national debate on income inequality.

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

"Starred Review. This slim, searing look at extreme poverty deftly mixes policy research and heartrending narratives from a swath of the 1.5 million American households eking out an existence on cash incomes of $2 per person per day." - Publishers Weekly "An eye-opening account of the lives ensnared in the new poverty cycle." - Kirkus "Affluent Americans often cherish the belief that poverty in America is far more comfortable than poverty in the rest of the world. Edin and Shaefer's devastating account of life at $2 or less a day blows that myth out of the water. This is world class poverty at a level that should mobilize not only national alarm, but international attention." - Barbara Ehrenreich, author of Nickeled and Dimed "In $2.00 A Day, Kathy Edin and Luke Shaefer reveal a shameful truth about our prosperous nation: many - far too many - get by on what many of us spend on coffee each day. It's a chilling book, and should be essential reading for all of us." - Alex Kotlowitz, author of There Are No Children Here "Kathryn Edin and Luke Shaefer deliver an incisive pocket history of 1990s welfare reform - and then blow the lid off what has happened in the decades afterward. Edin's and Shaefer's portraits of people in Chicago, Mississippi, Tennessee, Baltimore, and more forced into underground, damaging survival strategies, here in first-world America, are truly chilling. This is income inequality in America at its most stark and most hidden." - Michael Eric Dyson, author of Come Hell or High Water: Hurricane Katrina and the Color of Disaster

Click here and be the first to review this book!

Author Information

Kathryn j. edin.

Kathryn J. Edin is one of the nation's leading poverty researchers, recognized for using both quantitative research and direct, in-depth observation to illuminate key mysteries about people living in poverty: "In a field of poverty experts who rarely meet the poor, Edin usefully defies convention" ( New York Times ). Her books include Promises I Can't Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage and Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City. Edin is the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Public Health at Johns Hopkins University.

More Author Information

More Recommendations

Readers also browsed . . ..

- The Country of the Blind by Andrew Leland

- Red Memory by Tania Branigan

- All You Have to Do Is Call by Kerri Maher

- Says Who? by Anne Curzan

- The Demon of Unrest by Erik Larson

- Poverty, by America by Matthew Desmond

- Flee North by Scott Shane

- Impossible Escape by Steve Sheinkin

- Absolution by Alice McDermott

- Becoming Madam Secretary by Stephanie Dray

more history, current affairs and religion...

Support BookBrowse

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Flower Sisters by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

Who Said...

Any activity becomes creative when the doer cares about doing it right, or better.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

- Keep Your Goals In View.

- Weather the Storm.

- Because it is there.

- Trust Your Path.

- Wake up from your digital slumber.

- Protect Your Energy.

- Vote with your Feet.

- Keep the promise you make to yourself.

Book Summary – $ 2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America by Kathryn J. Edin & H. Luke Shaefer.

After two decades of brilliant research on American poverty, Kathryn Edin noticed something she hadn’t seen before – households surviving on virtually no cash income. Edin teamed with Luke Shaefer, an expert on calculating incomes of the poor, to discover that the number of American families living on $ 2.00 per person, per day , has skyrocketed to one and a half million households, including about three million children.

The authors argue that in-kind benefits like SNAP (food stamps) are important—even vital. Yet in 21st Century America, they are not enough—cash is critical. The book is about what happens when a government safety net that is built on the assumption of full-time, stable employment at a living wage combines with a low-wage labor market that fails to deliver on any of the above. It is this toxic alchemy, the authors argue, that is spurring the increasing numbers of $2-a-day poor in America.

A hidden but growing landscape of survival strategies among those who experience this level of destitution has been the result. At the community level, these strategies can pull families into a web of exploitation and illegality that turns conventional morality upside down.

Favorite Takeaways -$ 2.00 a Day

Two dollars is less than the cost of a gallon of gas, roughly equivalent to that of a half gallon of milk. Many Americans have spent more than that before they get to work or school in the morning. Yet in 2011, more than 4 percent of all households with children in the world’s wealthiest nation were living in a poverty so deep that most Americans don’t believe it even exists in this country.

US Government Welfare Programs

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program ( SNAP )

In the United States, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program ( SNAP ), formerly known as the Food Stamp Program , is a federal program that provides food-purchasing assistance for low- and no-income people.

SNAP benefits supplied roughly 40 million Americans in 2018, at an expenditure of $57.1 billion SNAP benefits cost a total of $85.6B in the 2020 fiscal year amid heightened US poverty and unemployment.

Aid to Families with Dependent Children ( AFDC )

Aid to Families with Dependent Children ( AFDC ) was a federal assistance program in the United States in effect from 1935 to 1997. Administered by the United States Department of Health and Human Services that provided financial assistance to children whose families had low or no income.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families ( TANF )

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families ( TANF ) is a federal assistance program of the United States. It began on July 1, 1997, and succeeded the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, providing cash assistance to indigent American families through the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP)

The SIPP, administered by the U.S. Census Bureau, is based on survey interviews with tens of thousands of American households each year. Census Bureau employees ask detailed questions about every possible source of income, including gifts from family and friends and cash from odd jobs. A key goal of the survey is to get the most accurate accounting possible of the incomes of the poor and the degree to which they participate in government programs.

America’s cash welfare program

America’s cash welfare program—the main government program that caught people when they fell—was not merely replaced with the 1996 welfare reform; it was very nearly destroyed. In its place arose a different kind of safety net, one that provides a powerful hand up to some—the working poor—but offers much less to others, those who can’t manage to find or keep a job.

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

The EITC is refundable, which means that if the amount for which low-income workers are eligible is more than they owe in taxes, they will get a refund for the difference. Low-income working parents often get tax refunds that are far greater than the income taxes withheld from their paychecks during the year.

Section 8. – housing choice voucher program

Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1937 (42 U.S.C.), often called Section 8 , as repeatedly amended, authorizes the payment of rental housing assistance to private landlords on behalf of low-income households in the United States.

Of the 5.2 million American Households that received rental assistance in 2018, approximately 2.2 million of those households received a Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher. 68% of total rental assistance in the United States goes to seniors, children, and those with disabilities .

Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is a means-tested program that provides cash payments to disabled children, disabled adults, and individuals aged 65 or older who are citizens or nationals of the United States.

Welfare is Dead

At the old welfare program’s height in 1994, it served more than 14.2 million people—4.6 million adults and 9.6 million children. In 2012, there were only 4.4 million people left on the rolls—1.1 million adults (about a quarter of whom were working) and 3.3 million kids. That’s a 69 percent decline. By fall 2014, the TANF caseload had fallen to 3.8 million.

Before 1996, welfare was putting a sizable dent in the number of families living below the $2-a-day threshold. As of early 1996, the program was lifting more than a million households with children out of $2-a-day poverty every month. Whatever else could be said for or against welfare, it provided a safety net for the poorest of the poor. In the late 1990s, as welfare reform was gradually implemented across the states, its impact in reducing $2-a-day poverty began to decline precipitously. By mid-2011, TANF was lifting only about 300,000 households with children above the $2-a-day mark.

We waged a war on poverty, and poverty won. – Ronald Reagan

Welfare Queen

In 1960, only about 5 percent of births were to unmarried women, consistent with the two previous decades. But then the percentage began to rise at an astonishing pace, doubling by the early 1970s and nearly doubling again over the next decade. A cascade of criticism blamed welfare for this trend. According to this narrative, supporting unwed mothers with public dollars made them more likely to trade in a husband for the dole.

In a speech in January 1976, Reagan announced that she “[has] used 80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans benefits for four nonexistent, deceased veteran husbands, as well as welfare. Her tax-free cash income alone has been running $150,000 a year.

“By 1988, there were 10.9 million recipients on AFDC, about the same number as when he took office. Four years later, when Reagan’s successor, George H. W. Bush, left office, the welfare caseloads reached 13.8 million—4.5 million adults and their 9.3 million dependent children.”

Growing Poverty

According to Feeding America, an antihunger organization and national network of food banks that conducts the nation’s largest study of charitable food distribution in the United States every few years, pantries and other emergency food programs nationwide served roughly 21.4 million Americans in 1997. By 2005, that number was higher by 3.9 million, and it ballooned even further during the Great Recession, to 37 million Americans in 2009.

Beginning in 2004, public schools were mandated to count the number of homeless children in their classrooms. (This is the number of children whose parents or guardians could not afford permanent housing but were still attending school.) In 2004–2005, there were 656,000 such children. This number spiked temporarily in 2005–2006 because of Hurricanes Katrina and Wilma, but then gradually increased over time, reaching 795,000 in 2007–2008 and 1.3 million in 2012–2013.

“For the $2-a-day poor, whose home lives are often incredibly stressed, work can even offer an escape of sorts. ”

Manufacturing, which once accounted for more than 30 percent of all jobs in the United States, now provides less than 10 percent of jobs. The country had roughly 12 million manufacturing jobs as of 2012, 7 million fewer than at the sector’s peak in the late 1970s. In contrast, there were about 15 million jobs in the retail sector and almost 14 million in leisure and hospitality.

Housing Cost

Housing costs have reached a crisis point for low-income families, eating up far more of their incomes than they can possibly afford. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) deems a family that is spending more than 30 percent of its income on housing to be “cost burdened,” at risk of having too little money for food, clothing, and other essential expenses.

“Today there is no state in the Union in which a family that is supported by a full-time, minimum-wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent without being cost burdened, according to HUD.”

Housing instability is a hallmark of life among the $2-a-day poor. Children experiencing $2-a-day poverty are far more likely to move over the course of a year than other kids—even than children living in less extreme poverty. Much of this instability is fueled by perilous double-ups, which mark—and often speed—the descent of those who are already suffering from the fallout from nonsustaining work into the ranks of the desperately poor.

Toxic Stress,

Toxic Stress defined as “strong, frequent, or prolonged activation of the body’s stress response systems in the absence of the buffering protection of a supportive, adult relationship.

Exposure to toxic stress affects people mentally and even physically. It can impair “executive functions, such as decision-making, working memory, behavioral self-regulation, and mood and impulse control.” It “may result in anatomic changes and/or physiologic dysregulations that are the precursors of later impairments in learning and behavior as well as the roots of chronic, stress-related physical and mental illness.” Toxic stress can literally wear you down and, in the end, kill you.

Survival Strategies

The panoply of survival strategies used by today’s $2-a-day poor are variations on the same tactics poor families used a generation ago to get by: private charity, a variety of small-time under-the-table income-generating schemes, and plain old scrimping.

Survival strategies come in three forms :

Public Spaces and Private Charities – Free Events and Resources

The first is taking advantage of public spaces and private charities—the nation’s libraries, food pantries, homeless shelters, and so on.

Income-Generation Strategies – Cash

Then come a variety of income-generation strategies, such as donating plasma—means for gleaning at least some of that all-important resource that families seem unable to survive without: cash.

Finally, there’s the art—often finely honed through years of hardship—of finding ways to stretch your resources and make do with less.

private charities

Beyond these vital public spaces, there are many private charities across Chicago like La Casa that serve the poor day in and day out, operating shelters, food pantries and soup kitchens, free health clinics, job training programs, and educational programs for children and youth.

Most of this aid comes not in the form of cash, but rather through in-kind assistance targeting basic needs (such as shelter and food) or direct services (such as health exams and mental health counseling). The forms this aid takes are not just determined by what families seeking help need. Rather, the nonprofits must be conscious of the values of the broader community and of the requirements placed on them by the government agencies, private foundations, and donors who fund the work. Sometimes what is offered fits what a family needs well. Sometimes it doesn’t.

The Art of Making Do with Less

Even accounting for what’s made available by the nation’s private charities and for the little amounts of cash that can be generated from the various strategies discussed previously, none of these resources can in and of themselves allow a family in $2-a-day poverty to survive.

Survival takes more. It requires a stubborn optimism in the face of very tough circumstances. It requires a spirit of determination that can propel someone forward in his or her effort to make do on next to nothing. So beyond private charity and public spaces, beyond selling SNAP, scrap, blood plasma, and even one’s body, the primary way the $2-a-day poor cope is to find inventive ways to make do with less. Some have spent years, even decades, in and out of poverty, with multiple spells of living on virtually nothing. For these Americans, the entrepreneurial skills that have been honed by the school of hard knocks are impressive indeed.

The authors approach to ending $2-a-day poverty is guided by three principles:

(1) all deserve the opportunity to work; (2) parents should be able to raise their children in a place of their own; and (3) not every parent will be able to work or work all of the time, but parents’ well-being, and the well-being of their children, should nonetheless be ensured.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Lifelong Learner | Entrepreneur | Digital Strategist at Reputiva LLC | Marathoner | Bibliophile [email protected] | [email protected]

Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It’s Doing to Us by Will Storr.

Top 30 Quotes on Change.

Related posts, book summary: the seat of the soul by gary zukav., book summary: the power of one more by ed mylett., book summary: the four tendencies by gretchen rubin., book summary: slow productivity by cal newport., book summary: mastery by george leonard., book summary: what got you here won’t get you there by marshall goldsmith..

Pingback: 100 Books Reading Challenge 2021 – Lanre Dahunsi

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

$2.00 A DAY

Living on almost nothing in america.

by Kathryn J. Edin & H. Luke Shaefer ‧ RELEASE DATE: Sept. 1, 2015

An eye-opening account of the lives ensnared in the new poverty cycle.

An analysis of the growing portion of American poor who live on an average of $2 per day.