The Future of Peer Review

- Peer Review

Essential Science Conversations

February 2023

- Transcript (PDF, 84KB)

- Related resources (PDF, 110KB)

Many recent changes, coming from the White House, the academy, and advances in technology, have raised questions about the future of peer review. Is peer review worth saving? Should peer review processes be revised? How should reviewers’ work be recognized? Join us for an Essential Science Conversation on The Future of Peer Review.

This program does not offer CE credit.

Joanne Davila, PhD

Professor of psychology, Stony Brook University.

Craig Rodriguez-Seijas, PhD

Assistant professor of psychology, University of Michigan.

Jessica Schleider, PhD

Assistant professor of psychology, Stony Brook University.

Jasper Simons, MA

Chief publishing officer, APA.

Mitch Prinstein, PhD

Chief Science Officer, APA.

More in this series

The number of publications among graduate school/faculty applicants, or among those applying for tenure and promotion seems to have increased considerably

September 18, 2024 Live Webinar

Physical activity benefits mental and physical health, yet participation rates are declining.

May 2024 On Demand Webinar

Discussing AI's impact on psychological research: potential to replace human participants, unintended consequences, peer review challenges, and ethical considerations.

April 2024 On Demand Webinar

Panel discusses strategies to combat stigma across clinical, research, educational, and community settings.

March 2024 On Demand Webinar

- Current Students

Half-million-dollar grant will create peer review and science communication curriculum for grad students

- By Elise Proulx

- 3 min. read ▪ Published August 29

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook

- Share on X (Twitter)

The ability to critically evaluate scientific literature is crucial for graduate students as they start their careers in science.

However, a lack of systematic training can hamper students’ future ability to review the work of others in their field.

“Reviewing scientific literature and analyzing literature is a huge part of graduate student education,” says Sarah Klass , a postdoctoral fellow in the Keasling Lab at UC Berkeley and the Joint Bioenergy Institute and the lead recipient of a $499,992, two-year grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF). “But there’s no formal education” on how to do it, Klass continues.

To attempt to remedy this disconnection, Klass and her partners will use the NSF grant to fund a new curriculum that will immerse graduate students in the sciences in the “principles and practices of peer review and science communication with a heavy emphasis on building practical skills.” Peer review is the system in which multiple experts review scientific papers to ensure quality before publication.

The team will spend the first year developing a curriculum. The second year, UC Berkeley grad students will put it to the test. The grant team, which will also include UC Berkeley School of Public Health professor Stefano M. Bertozzi and a to-be-determined team of UC Berkeley graduate students, will collect data on impact and effectiveness.

The proposed curriculum builds upon the success that the journal Rapid Reviews\Infectious Diseases ( RR\ID ) has had in making rigorous peer review faster and more efficient, partially by training UC Berkeley undergraduate students. RR\ID is an open-access journal that prioritizes rapid and efficient peer review alongside offering student training and mentoring and supporting the democratization of academic publishing through partnerships with a dozen academic institutions in low- and middle-income countries that will be established over the next three years. Bertozzi is the journal’s editor-in-chief

“As part of UC Berkeley Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program, RR\ID editors have offered a workshop allowing undergraduates to participate in research projects with faculty members for academic credit, focusing on topics of special interest,” the grant application reads. “The aim is to familiarize undergraduate students with contemporary scientific and academic research, peer review processes, and publication standards, particularly concerning infectious diseases.”

The new curriculum project will pilot a curriculum for a training program that will initially involve STEM graduate students enrolled at UC Berkeley, specializing in a broad spectrum of fields related to infectious diseases, data science, public health, engineering, and basic biological and chemical sciences. “By providing graduate students with the necessary tools and insights to critically evaluate scientific literature and review preprints, our goal is to improve graduate student research/literature comprehension and engagement with their respective STEM fields,” the team said.

“We are trying to teach good peer review skills to graduate students so they can help enable the rapid dissemination of scientifically vetted literature that can have an immediate impact on people’s lives,” says Klass.

“Above all, the intellectual discourse that needs to happen around science is closed off and isolated,” says Hildy Fong Baker, executive director of the UC Berkeley Center for Global Public Health and managing director of the project. “We are creating an avenue for people to be part of an ecosystem at the beginning of their careers.”

The course materials created during the two-year grant period will eventually be available to all via open access to encourage other institutions to adopt and adapt the curriculum worldwide.

People of BPH found in this article include:

- Stefano Bertozzi Professor, Health Policy and Management

More in category “School News”:

Meet our new faculty: xiudi li, alum melissa stafford jones on her career developing meaningful policy approaches in public health, uc berkeley school of public health welcomes inaugural cohort of impact fellows, new alumni association co-presidents are ready to foster engagement and make an impact.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- For authors

- New editors

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Online First

- They are still children: a scoping review of conditions for positive engagement in elite youth sport

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5244-6416 Stuart G. Wilson 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0009-0000-1865-0915 Mia KurtzFavero 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4616-2617 Haley H. Smith 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1377-0234 Michael F Bergeron 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3242-599X Jean Côté 1

- 1 School of Kinesiology & Health Studies , Queen's University , Kingston , Ontario , Canada

- 2 Performance Health , WTA Women’s Tennis Association , St. Petersburg , Florida , USA

- Correspondence to Dr Stuart G. Wilson; Stuart.wilson{at}queensu.ca

Objective The objective of this study is to characterise the key factors that influence positive engagement and desirable developmental outcomes in sport among elite youth athletes by summarising the methods, groups and pertinent topical areas examined in the extant published research.

Design Scoping review.

Data sources We searched the databases SPORTDiscus, APA PsycINFO, Web of Science and Sports Medicine & Education Index for peer-reviewed, published in English articles that considered the factors influencing positive developmental outcomes for athletes under 18 years competing at a national and/or international level.

Results The search returned 549 articles, of which 43 met the inclusion criteria. 16 studies used a qualitative approach, 14 collected quantitative data, 2 adopted mixed methods and 11 were reviews. Seven articles involved athletes competing in absolute skill contexts (ie, against the best athletes of any age) while the majority involved athletes competing in relative skill contexts (ie, against the best in a specific age or developmental group). The studies described the characteristics of the athletes, as well as their training, relationships with others, social and physical environments, and/or their overall developmental pathways.

Conclusion Existing research on positive engagement in elite youth sport aligned with and mapped onto established models of positive development in youth sport more generally. Our findings further support that, while certain youth athletes may demonstrate extraordinary performance capabilities, they are still children who benefit from positive engagement prompted and reinforced by developmentally appropriate and supportive activities, relationships and environments.

- Psychology, Sports

- Athletic Performance

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2024-108200

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

X @SGWilsonQU, @mia_jkf, @hale_smith, @DrMBergeron_01, @jeancote46

Contributors SGW is the guarantor. JC and MFB conceived of the project. SGW, MK, HHS and JC designed and conducted the review. SGW, MK and JC drafted the paper, and all authors contributed to editing and revising the paper.

Funding This research was supported by a Research Grant from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC Grant # 435-2020-0094).

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Peer reviewers wanted: Help colleagues grow their teaching skills

Corie Farnsley Aug 26, 2024

Annual peer review of teaching training workshop is Sept. 24

Is this you?

- You have a talent for teaching, guiding, mentoring or serving.

- You have a heart for building up those around you.

- You are seeking opportunities to serve your colleagues while helping the Indiana University School of Medicine continue to provide world-class medical education for learners.

If yes, clear your schedule from 3 to 4:30 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 24, and learn how you can get involved in peer review of teaching.

The annual Academy of Teaching Scholars session, Giving Great Teaching Feedback: How to Conduct a Peer Review of Teaching , is the first (required) step for becoming a peer reviewer. During this online session, you will learn to provide effective feedback to colleagues that can inspire change and improve learner experiences in the classroom, operating room, labs and clinical settings.

Who should attend

- Anyone interested in conducting peer reviews of teaching; the course is required for new reviewers

- Veteran reviewers who would like to refresh their skills and knowledge of peer review best practices

- Faculty who are interested in serving their school and peers on a flexible schedule can learn about important best practices and receive the resources they need to provide effective feedback.

- Faculty who wish to be promoted, gain tenure, earn awards, join honor societies or simply improve their teaching effectiveness should undergo multiple peer reviews of their teaching over the course of their time at IU School of Medicine. In addition to learner evaluations, peer reviews of teaching help faculty members documenting a holistic review of their teaching efforts. Faculty peer reviewers are an essential resource for fellow colleagues and for the school as a whole.

“Becoming a better educator requires one being open to feedback from both learners and peers,” said Matthew Holley, PhD, assistant dean for faculty affairs and professional development and the director of both the Academy of Teaching Scholars and the Peer Review of Teaching programs. “Using the feedback from a peer review, educators can spend time reflecting upon their work — acknowledging their strengths but also their potential areas for growth. By serving as a peer reviewer, you play an important role in the growth and development of educators.”

What the session will cover

- The administrative process IU School of Medicine uses to manage peer reviews

- The steps you should take to ensure an effective review

- The various reasons why faculty undergo review and how to adjust reviews to meet faculty needs

- Resources to efficiently conduct a peer review

- Examples of established reviewers' experiences conducting and completing reviews

Participants and session leaders will conduct a mini peer review as a group during the session.

Growth is never by mere chance; it is the result of forces working together.

James Cash Penney

Corie Farnsley

Corie is communications generalist for Indiana University School of Medicine Faculty Affairs and Professional Development (FAPD). She focuses on telling the story of FAPD by sharing information about the many opportunities the unit provides for individuals’ professional development, the stories behind how these offerings help shape a broad culture of faculty vitality, and ultimately the impact IU School of Medicine faculty have on the future of health. She is a proud IU Bloomington School of Journalism alumna who joined the IU School of Medicine team in 2023 with nearly 25 years of communications and marketing experience.

- Open access

- Published: 24 August 2024

The impact of religious spiritual care training on the spiritual health and care burden of elderly family caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a field trial study

- Afifeh Qorbani 1 ,

- Shahnaz Pouladi 2 ,

- Akram Farhadi 3 &

- Razieh Bagherzadeh 2

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 584 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

98 Accesses

Metrics details

Family caregiving is associated with many physical and psychological problems for caregivers, but the effect of spiritual support on reducing their issues during a crisis is also the subject of research. The study aims to examine the impact of religious spiritual care training on the spiritual health and care burdens of elderly family caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

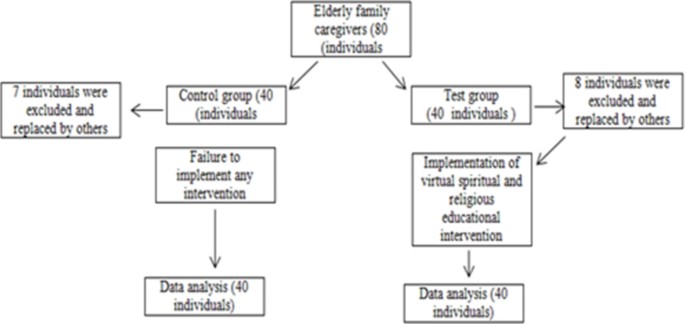

The randomized controlled field trial involved 80 Iranian family caregivers in Bushehr City, who were selected by convenience sampling based on the inclusion criteria and divided into experimental (40 people) and control (40 people) groups by simple random sampling in 2021 and 2022. Data collection was conducted using spiritual health and care burden questionnaires using the Porsline software. The virtual intervention included spiritual and religious education. Four virtual sessions were held offline over two weeks. The first session was to get to know the participants and explain the purpose, The second session focused on the burden of care, the third on empowerment, and the fourth on mental health and related issues. In the control group, daily life continued as usual during the study.

Mean changes in existential health (3.40 ± 6.25) and total spiritual health (5.05 ± 11.12) increased in the intervention group and decreased in the control group. There were statistically significant differences between the two groups for existential health (t = 3.78, p = 0.001) and spiritual health (t = 3.13, p = 0.002). Cohen’s d-effect sizes for spiritual health and caregiving burden were 0.415 and 0.366, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in mean changes in religious health ( p = 0.067) or caregiving burden ( p = 0.638) between the two intervention and control groups.

Given that the religious-spiritual intervention had a positive effect on existential health and no impact on religious health or care burden, it is recommended that comprehensive planning be undertaken to improve the spiritual health of family caregivers to enable them to better cope with critical situations such as a COVID-19 pandemic.

Trial registration

IRCT code number IRCT20150529022466N16 and trial ID number 48,021. (Registration Date2020/06/28)

Peer Review reports

With the global outbreak of COVID-19 on January 12, 2020, and the highly contagious nature of this virus, the World Health Organization issued protocols for limiting community interactions worldwide [ 1 ]. While individuals of all ages are susceptible to COVID-19, The high incidence of infection in older people, the greater severity of the disease, and the increased mortality are significant challenges in implementing appropriate preventive measures and future strategies to protect against this disease in the geriatric population [ 2 , 3 ]. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 31% of COVID-19 cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of intensive care unit admissions, and 80% of COVID-19-related deaths in the United States occur in the elderly [ 4 ].

During the COVID-19 crisis, elderly people required various forms of assistance, including telephone and digital visits, with most of these services provided by family members [ 5 ], Park (2021) reported that long-term caregivers (> 1 year) had more negative somatic physical symptoms (headaches, body aches, and abdominal discomfort), worse mental health, and more significant fatigue than non-caregivers [ 6 ]. Family caregivers can only provide up to 80% of the required care to seniors with Multiple chronic conditions in the community, and they are also responsible for the majority of the costs and shoulder the related burden. This increased reliance on family caregivers has, in turn, heightened their care burden. The burden of care is a significant issue globally, with millions of individuals taking on caregiving responsibilities for their loved ones. The care burden encompasses various dimensions, including time-dependent, evolving, physical, social, and emotional aspects, making it a complex and highly individualized concept [ 7 ]. It often results from a negative imbalance between caregiving responsibilities and other obligations [ 8 ].

In Iran, like in many other countries, this burden can have profound implications on caregivers’ physical, emotional, and financial well-being. By introducing the concept of spiritual health into the discourse, we aim to shed light on a potentially overlooked aspect that could provide additional support and resilience to caregivers. Statistics indicate that caregivers who report a strong sense of spiritual well-being often exhibit lower levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, highlighting the importance of addressing this dimension in caregiving research. The existing literature on caregiver burden focuses mainly on caregiving’s physical and emotional aspects. While these studies provide valuable insights, there is a noticeable gap in understanding the role of spiritual health in mitigating the burden of care. Further exploration is needed to investigate how spiritual well-being can influence the overall caregiving experience and contribute to the well-being of the caregiver and the care recipient. In Iranians’ religious and national culture, the elderly hold a revered position and are highly respected. Reflecting on this cultural perspective, the Prophet of Islam stated, that respecting older people of my community is the same as respecting me [ 9 ]. This cultural context is evident in the fact that 86.4% of elderly individuals in Iran, according to statistics from the welfare organization, live with their children and spouses [ 10 ]. However, when caregiving responsibilities increase, they can overshadow the multiple health dimensions of the older people’s family members, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects. Coping strategies, such as spiritual-religious approaches, are often employed to manage the challenges [ 11 ].

There are two dimensions to spiritual health: religious and existential. Religious health refers to how a person understands his or her spiritual well-being when connected to a higher power. Conversely, existential health centers on an individual’s capacity for adaptation to their being, the societal landscape, and the broader environment [ 12 ]. In the past, the significance of spirituality in effectively managing stress was often underestimated; however, recent years have seen increased attention from researchers [ 11 , 13 , 14 ]. It is important to note that the understanding of spirituality is influenced by culture and religion, and its implications may vary for different individuals [ 15 ]. The current research gap lies in the lack of comprehensive studies that assess the intersection of spiritual health and care burden in the Iranian caregiving landscape. While some research exists on the broader topic of spirituality and health, there is a need for targeted investigations that consider the unique cultural and religious factors that shape the Iranian perspective on caregiving. Understanding these nuances can provide valuable insights into how spiritual care practices can be effectively integrated into support systems for caregivers in Iran. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the impact of religious-spiritual care training on the spiritual health and care burden of family caregivers of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the critical role of nurses as caregivers for family and elderly health along with their supportive function [ 16 ], it is essential to identify caregivers at risk during critical situations and address their spiritual needs as part of community-oriented care. The study aimed to examine the impact of religious spiritual care training on the spiritual health and caregiving burden of older family carers during the COVID-19 pandemic. By thoroughly exploring the relationship between spiritual health and the caregiving burden of older family carers, we aim to identify potential strategies and interventions that can improve the well-being of caregivers and the overall quality of care provided to care recipients in Iran.

Study design

This study utilized a randomized controlled field trial design. The choice of a field randomized controlled trial for this study provides a rigorous and systematic approach to evaluating the effectiveness of a spiritual health intervention on care burden among Iranian caregivers. This design ensures internal validity, generalizability, and ethical soundness, thereby strengthening the overall quality of the research findings.

Participants and data collection

Participants were selected from the home care department of the comprehensive rehabilitation service center for the elderly in Mohammadieh, Bushehr City (affiliated with the welfare organization), and four comprehensive urban health centers in Bushehr Port, specifically Kheybar, Quds, Meraj, and Shohada centers. The inclusion criteria encompass caring for elderly individuals who showed a degree of dependence in at least one of their six daily activities, as defined by Katz’s criteria for activities of daily living (ADL). Additionally, caregivers had to possess literacy skills (reading and writing), with at least six months having elapsed since the commencement of their caregiving responsibilities. Furthermore, inclusion criteria require a family relationship between caregivers and elderly individuals in their care, cohabitation with older people, and delivering at least 40 h of care per week. Caregivers had to be at least 18-year-old Shia Muslims. The exclusion criteria dictated that the caregivers be excluded from the study under certain conditions, including the death of either the caregiver or the elderly individual during the study, refusal to continue participation in the study, the presence of neurological and psychiatric diseases, or the use of neuropsychiatric drugs, self-reported drug or alcohol addiction, or prior involvement in a spiritual-religious educational program related to elderly care.

Sample size

Based on the effect sizes observed in the studies by Hosseini et al. (2016) [ 17 ], Mahdavi et al. (2016) [ 18 ], and Moeini et al. (2012) [ 19 ], with a Type I error rate of 0.50 and a power of 80%, and using the G Power 3.1.9.2 software, the required sample size for the two-group test was approximately 80 individuals, with 40 participants in each group. Eligible elderly family caregivers were selected from available candidates and randomly assigned to either the test or control group (Fig. 1 ). Randomization was done using Random Allocation software and by a person who did not know the participants and did not know their characteristics.

Consort diagram

Instruments

The data collection instruments used in this study consisted of a demographic information form, along with the spiritual health questionnaire developed by Paloutzian and Ellison (1982) and the care burden questionnaire designed by Novak and Guest (1989).

Demographic information form

This form collected information about the caregiver, including age, number of children, family relationship to older people, level of education, occupation, income, and type of housing.

Spiritual health questionnaire (Paloutzian and Ellison, 1982)

The Spiritual Health Questionnaire, developed by Paloutzian and Ellison in 1982, is widely used to assess an individual’s spiritual well-being and beliefs. This questionnaire consists of 20 items that explore different aspects of spirituality, including beliefs, practices, values, and experiences. Participants are asked to respond to statements about spirituality on a six-point Likert scale, with responses to agree strongly or to disagree strongly. This questionnaire includes two subscales: (1) Religious well-being (10 items): This subscale assesses how an individual’s religious beliefs, values, and practices contribute to their overall well-being and sense of purpose. (2) Existential well-being (10 items): This subscale focuses on the individual’s sense of meaning, purpose, and connection to something greater than themselves, regardless of religious affiliation. Each subscale receives a score from 10 to 60. The spiritual health score is the sum of these two subscales and ranges from 20 to 120. In Iran, during the research conducted by Parvizi et al. (2000), the reliability of this questionnaire using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.82 [ 20 ]. In Hamdami et al.‘s research (2015), Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the total spiritual health score was 0.79 [ 21 ].

Care burden questionnaire (Novak and Guest, 1989)

The Care Burden Questionnaire, developed by Novak and Guest in 1989, is a widely used instrument for assessing the burden experienced by caregivers who provide care to individuals with chronic illnesses or disabilities. Caregivers are asked to respond to a series of statements concerning caregiving burden on a Likert scale, with response options typically ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). The maximum score that can be attained on this questionnaire is 96, while the minimum score is 0. The questionnaire includes five sub-scales designed to capture a specific aspect of the burden. These include time demands, emotional stress, social isolation, financial strain, and conflicts with other responsibilities. In Iran, in the study of Abbasi et al. (2013), the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this questionnaire was 0.90, and its subscales ranged from 0.72 to 0.82 [ 22 ].

Baseline test

Before the intervention, research sessions were initially scheduled to occur in person; however, the coronavirus pandemic rendered it impractical to conduct face-to-face training sessions. As a result, spiritual and religious training was carried out online without impacting b behavioral therapy (CBT) and stress management techniques. It was structured to address the emotional, social, and physical dimensions of caregiver burden while simultaneously fostering coping strategies and self-care practices. The intervention framework was informed by existing research on caregiver interventions, CBT, and stress management. Studies have shown the effectiveness of psychoeducational programs in reducing caregiver burden and enhancing well-being. The incorporation of CBT techniques aimed to help caregivers identify and reframe negative thought patterns, while stress management strategies were included to help caregivers better cope with stressors.

In the test group, the intervention took the form of spiritual care based on the model of Richards and Bergin, which was aligned with Islamic teachings. This model featured six key steps: First, caregivers were guided to pay attention to spiritual-cultural sensitivities. Second, they were trained to establish an open and secure spiritual relationship. Third, potential ethical challenges were addressed. Fourth, caregivers conducted a religious and spiritual assessment of clients. The fifth step involved defining suitable goals for spiritual therapy, and the final step focused on properly implementing spiritual interventions [ 23 ]. The educational sessions covered various dimensions of the care burden, including physical, mental, social, and financial elements, as well as facets of spiritual health, which included the religious dimension (about communication with a transcendent higher power) and the existential dimension (encompassing communication with oneself, creation, and all living beings). These educational sessions were delivered via pre-recorded video presentations developed by a specialist in geriatric nursing and religious education. Participants engaged in four virtual sessions offline, conducted through WhatsApp social messenger, with two sessions held per week. Each session involved the following activities: (1) Following up on the previous session’s topics; (2) providing feedback to participants; (3) summarizing and outlining previous topics to create a connection between the topics discussed; and (4) offering explanations and summaries related to the new session’s topic. One month after the end of the intervention, test and control group participants completed the Mental Health Questionnaire and the Carer’s Burden Questionnaire again. The control group continued with their daily lives as usual throughout the study. Upon its conclusion, the educational materials on spirituality and its various concepts, which had been shared via WhatsApp Messenger, were made available in alignment with the ethical principles that govern such research. The educational content for the sessions was developed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a nurse psychiatrist, a gerontologist, and a Specialist in Quran and Hadith. The educational content was designed and compiled by the research team to improve practical skills, stress management, self-care, and communication, based on the model of Richards and Bergin and according to the teachings of Islam and the Shia religion. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the content, the educational materials underwent a rigorous review process involving experts from diverse fields, including caregiving, psychology, and Quranic and Hadith sciences. Feedback from caregivers and pilot testing were also used to refine and validate the content before implementation. A pilot study was conducted to test the intervention’s feasibility, acceptability, and initial effectiveness. The pilot study involved a small group of caregivers who received the intervention, and their feedback was used to refine the program before full implementation. All contributors implementing the intervention received comprehensive training on the educational content and intervention protocols. These trainings were followed daily by viewing the participants’ WhatsApp to receive educational content and listening to audio files, making daily phone calls, and asking them questions over the phone to understand the content and express their questions. The intervention was implemented by a team of trained healthcare professionals, including a social gerontologist, a nursing gerontologist, and a medical-surgical nursing student with a master’s degree. They all had relevant qualifications and expertise in mental health and caregiving support. Potential challenges for implementers could include caregiver resistance, emotional distress, not receiving training materials on time, or difficulty engaging participants. The plan for dealing with such situations included regular monitoring of caregiver progress, open communication, and flexibility in the delivery of sessions. For participants who required more specialized training or support beyond the scope of the intervention, referrals were made through telephone communication with the training session facilitators. Response data from the instruments, such as the Care Burden Questionnaire and other assessment measures, were collected through self-report questionnaires and standardized rating scales administered by trained assessors. Caregivers were asked to respond based on their experiences before and after the intervention. To handle ambiguities in the response data, assessors were trained to clarify any uncertainties or ambiguities in the questions with caregivers. This involved providing clear explanations, and examples, and ensuring that caregivers understood the questions before responding. A specific post-intervention assessment time point was established to standardize the time after the intervention for all participants. This time point was determined based on the intervention duration and the optimal timeframe for assessing the intervention’s impact on caregiver burden based on past studies [ 24 , 25 ]. Caregivers were scheduled for the post-intervention assessment at this standardized time point to ensure consistency across all participants.

Ethical considerations

This study originated from a master’s thesis in internal surgical nursing at the Faculty of Midwifery Nursing, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, with an ethics code number of IR.BPUMS.REC.1399.042. It is also registered with the Clinical Trial Centre of Iran under IRCT20150529022466N16. The caregivers were furnished with comprehensive information about the study, encompassing its objective, methodology, potential hazards and advantages, confidentiality protocols, and their entitlement to withdraw from the study at any point. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before they participated in the study. Measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality of participants’ personal information and data collected during the study. Participants were assured that their responses would be anonymized, stored securely, and only accessed by authorized research staff.

Data analysis

Due to the peak of the Corona pandemic and the closing of universities in person, the possibility of consulting statistics professors and performing data analysis was delayed for eight months. The data collected during the study were analyzed using SPSS version 19 software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the distribution of the data. An independent t-test, or Mann-Whitney test, was used to compare quantitative demographic variables between two groups. A Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare qualitative demographic variables between groups. To test the hypotheses above, a paired t-test was employed to ascertain the mean of the primary variables in question, before and after the intervention in each group. An independent t-test was utilized to determine the mean of the variables between groups, and Cohen’s d was calculated as the effect size. Independent t-tests were conducted to compare the mean scores of the changes. The significance level was assumed to be less than 0.05 in all cases.

No statistically significant differences were detected between the groups in terms of demographic variables, suggesting group homogeneity ( p > 0.05) (Tables 1 and 2 ). Regarding spiritual health, within the intervention group, the post-test average score for total spiritual health was significantly higher than the pre-test score ( p = 0.007), in contrast within the control group, the post-test average score was considerably lower than the pre-test score ( p = 0.003). No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of mean posttest spiritual health scores (Table 3 ) still, changes in overall spiritual health increased in the intervention group and decreased in the control group, with statistically significant differences between the two groups ( p = 0.002) (Table 4 ). The Cohen’s d effect size for the difference in spiritual health between the intervention and control groups was 0.415, indicating a moderate effect of the intervention (Table 3 ). Within-group analysis showed no statistically significant differences between pre-and post-test scores for total care burden in either group. Furthermore, no statistically significant differences between the two groups were observed in terms of average care burden scores ( p < 0.05) (Table 5 ). Likewise, the average changes in care burden scores between the intervention and control groups showed no statistically significant differences ( p < 0.05) (Table 6 ). The Cohen’s d effect size for the difference in caregiving burden between the intervention and control groups was 0.366, indicating a moderate effect of the intervention on caregiving burden, although not statistically significant (Table 5 ).

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of religious spiritual care training on the spiritual health and care burden experienced by elderly family caregivers in Bushehr during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study suggest that a religious and spiritual intervention approach can effectively promote existential health and overall spiritual well-being. However, it was observed that this approach did not yield a notable impact on religious health or care burden. The Scores for existential health and overall spiritual health increased in the intervention group after the training, while they decreased in the control group. The mean change in religious health scores between the two groups did not reach statistical significance. These findings are consistent with the study conducted by Sayyadi et al. (2018) [ 26 ], who also observed an increase in spiritual health following a religious psychotherapy intervention. In this study, most family caregivers in the experimental and control groups initially demonstrated moderate to high levels of spiritual health. Similarly, Sayyadi et al. (2018) found higher spiritual health scores in medical and nursing students compared to other student populations. To explain and interpret the consistent findings regarding the positive effects of spiritual health on caregivers in the study by Sayyadi et al. and the current study on the impact of religious spiritual care training on elderly family caregivers, we can consider several factors that may contribute to these findings: (1) Spiritual health is often associated with providing a sense of support, purpose and coping mechanisms during challenging times. Caregivers facing the stress and demands of caregiving may benefit from a solid spiritual foundation to help them navigate their roles and find meaning in their experiences. Studies may have highlighted the role of spiritual health as a resource for caregivers to cope with the emotional and psychological challenges they face. (2) Spiritual health can help to build resilience and foster hope in individuals, including caregivers. By nurturing their spiritual well-being, caregivers may develop a sense of resilience that enables them to cope with adversity and maintain a positive outlook. Studies may have observed the positive impact of spiritual health on caregivers’ resilience and hope, leading to improved well-being and outcomes. (3) Spiritual health is often linked to personal growth and making sense of one’s experiences [ 27 ]. Caregivers possessing a robust spiritual foundation may engage in meaning-making processes, facilitating the discovery of purpose and significance within their caregiving journey. Studies may have underscored the role of spiritual health in promoting personal growth and facilitating meaning-making among caregivers. These factors, alongside the consistent focus on spiritual health across studies, provide a robust framework for understanding the positive impact of spiritual health on caregivers. Recognizing the importance of spiritual well-being within the broader context of caregiver health, and integrating interventions that specifically address spiritual needs, can contribute to improved outcomes and well-being for caregivers. This is supported by the findings of both Sayyadi et al. and the present study. It is important to note that the religious health scores did not increase after the intervention in the current study. The intervention, centered on religious and spiritual care training, had a significant impact on both existential well-being and overall spiritual health. The caregiver survey of palliative care patients will likely target different aspects of spiritual well-being, such as hope and general well-being. In interpreting these results, it is essential to consider the unique components of each intervention and how they may have influenced different aspects of spiritual health. On the other hand, Casalerio et al. (2024) in the study: Promoting Spiritual Coping of Family Caregivers of an Adult Relative with Severe Mental Illness: Development and Test of a Nursing Intervention, reported that the spiritual and religious intervention for caregivers increased their spiritual health dimension and their religious dimension [ 28 ]. These contrasting religious findings with the current study suggest that the effectiveness of religious and spiritual interventions may vary depending on the specific focus and approach of the intervention. Caregivers’ responses to such interventions may be influenced by factors such as the nature of the caring role, the context of the carer’s condition, and individual preferences regarding spirituality and religiosity. Further research and tailored interventions may be needed to address the diverse spiritual needs of caregivers in different care contexts.

Regarding the care burden, the results of the current study demonstrated no statistically significant differences in the average care burden scores within and between the groups. This result contrasts with previous studies by Polat et al. (2024), Xavier et al. (2023) [ 13 , 29 ], Partovirad et al. (2024) [ 11 ], Hekmatpour and colleagues (2018) [ 30 ], Shoghi et al. (2018) [ 31 ], which showed reductions in the care burden following intervention models and the current study care burden result align with previous studies by Khalili et al. (2024) [ 32 ], Salmoirago-Blotcher et al. (2016) [ 33 ], and Karadag Arli (2017) [ 34 ]. One of the reasons why the present study did not show the same effect of spiritual and religious interventions in reducing caregiver burden as similar studies have shown is probably due to the high caregiver burden in the relevant situation. In the present study, caregiver burden had increased due to the conditions of the Corona pandemic, and reducing caregiver burden may require more extended, and more social interventions. One potential explanation for the lack of reduction in care burden scores in the current study is the influence of social interaction theory and attachment theory. These theoretical frameworks emphasize the significance of the dynamic interplay between caregiver and care recipient, particularly highlighting the role of mutual appreciation and non-violent communication in mitigating caregiver burden [ 35 ]. The physical and mental conditions of care recipients, coupled with their inability to engage in appropriate interactions with caregivers during the COVID-19 crisis, may have intensified the care burden. Furthermore, a review of similar studies reveals that most interventions aimed at reducing care burden were conducted over longer periods than our study. These studies typically involved a higher number of sessions, ranging from 8 to 12 (e.g., Mohammadi and Babaei (2018) [ 36 ], Rahgooy et al. (2018) [ 37 ], Sotoudeh et al. (2018) [ 38 ] and Salehinejad et al. (2017) [ 39 ] Consequently, the shorter duration and fewer sessions in our study may have limited the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing the care burden. Additionally, the limitations imposed by social distancing measures may have exacerbated the needs of elderly individuals, leading to an increased caregiver burden. Furthermore, a review of similar studies reveals that most interventions aimed at reducing care burden were conducted over more extended periods than our study. These studies typically involved a higher number of sessions, ranging from 8 to 12 (e.g., Mohammadi and Babaei (2018) [ 30 ], Rahgooy et al. (2018) [ 32 ], Sotoudeh et al. (2018) [ 39 ] and Salehinejad et al. Consequently, the shorter duration and fewer sessions in our study may have limited the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing the care burden.

Limitations

This study had limitations. The limitations imposed by the pandemic, including the need for social distancing, made it impossible to conduct face-to-face training sessions and deprived participants and carers of the opportunity for close, face-to-face communication during the spiritual and religious intervention. This limitation may have affected the participants’ internal beliefs, emotions, and motivations. The restrictions imposed by the pandemic, through the utilization of routine telephone communications and collaboration with pertinent academic staff, exemplify adaptability and ingenuity in maintaining communication with participants. This multi-channel approach may have helped to ensure continued engagement and support for participants throughout the intervention. Despite the challenges posed by the lack of face-to-face communication, the study managed to keep participants engaged through alternative means. The regular phone calls and coordination with the professors may have fostered a sense of connection and support, potentially enhancing participants’ overall experience and engagement with the intervention. The lack of face-to-face interaction during the spiritual and religious intervention may have limited the depth of participants’ engagement and the impact on their internal beliefs and motivations. This limitation could affect the validity of the study findings, as face-to-face communication is often crucial for building trust and rapport in interventions of this nature. The short duration of the intervention and the constraints imposed by the pandemic may have limited the generalizability of the study results. Further research utilizing more extended intervention periods and more diverse participant groups may enhance the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. Utilizing virtual platforms for interactive sessions and group discussions could facilitate the replication of the advantages of face-to-face communication and cultivate a sense of community among participants. Conducting long-term follow-up studies to track the sustained effects of spiritual and religious interventions on caregiver burden could provide valuable insights into the lasting impact and effectiveness of the intervention over time.

Based on the study, the results were mixed. The religious and spiritual intervention was effective in improving existential health and overall spiritual health but did not have a significant impact on religious health and caregiving burden. The training in religious and spiritual care was determined to be effective in enhancing the existential well-being of elderly family caregivers, as evidenced by an increase in their sense of meaning, purpose, and fulfillment in the caregiving role. The intervention demonstrated effectiveness in improving caregivers’ overall spiritual health, suggesting positive outcomes in terms of emotional well-being, connectedness, and resilience. Notwithstanding the favorable outcomes in existential and general spiritual well-being, the intervention did not demonstrate a notable impact on religious well-being and caregiver burden, underscoring domains that may warrant further investigation and the development of alternative intervention strategies. It is crucial to recognize the intricate nature of caregiving dynamics and the various ways in which spirituality and religion can impact the well-being of caregivers. The result of the study indicates that integrating religious and spiritual care training could effectively enhance the existential and holistic spiritual well-being of elderly family caregivers. Practitioners and caregivers can utilize this intervention to foster a greater sense of meaning and spiritual well-being within the caregiving context. In addition, the study highlights the importance of personalized interventions that consider individual differences in spiritual beliefs and coping strategies. In conclusion, while the religious and spiritual intervention showed promising results in improving certain aspects of the spiritual health of elderly family caregivers in Bushehr, further research is needed to address the nuances of religious health and care burden. By carefully considering these key findings and implications, practitioners and researchers can tailor interventions to better support caregivers’ holistic well-being in the face of challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Na Zhu DZ, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. 2020:727–33. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/ https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

Dhama K, Patel SK, Kumar R, Rana J, Yatoo MI, Kumar A, et al. Geriatric population during the COVID-19 pandemic: problems, considerations, exigencies, and beyond. Front Public Health. 2020;8:574198. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.574198

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhang J, Wang J, Liu H, Wu C. Association of dementia comorbidities with caregivers’ physical, psychological, social, and financial burden. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03774-9

Shahid ZKR, McClafferty B, Kepko D, Ramgobin D, Patel R. COVID-19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926–9. https://doi.org/.1111/jgs.16472 . Epub 2020 Apr 20. PMID: 32255507; PMCID: PMC7262251.

Moradi M, Navab E, Sharifi F, Namadi B, Rahimidoost M. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the elderly: a systematic review. J Salmand: Iran J Ageing. 2021;16(1):2–29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.574198

Article Google Scholar

Park SS. Caregivers’ mental health and somatic symptoms during COVID-19. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa121 . PMID: 32738144; PMCID: PMC7454918.

Malmir S, Navipour H, Negarandeh R. Exploring challenges among Iranian family caregivers of seniors with multiple chronic conditions: a qualitative research study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):270. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02881-3

Phillips R, Durkin M, Engward H, Cable G, Iancu M. The impact of caring for family members with mental illnesses on the caregiver: a scoping review. Health Promot Int. 2023;38(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac049 . PMID: 35472137; PMCID: PMC10269136.

jaafari zadeh H, SmS K, rahgozar M. Health care status of elderly people with disabilities in District 13 of Tehran Municipality and their problems. Journal of Urmia Nursing And Midwifery Faculty. 2006;4(2):67–81.

Nafei ARV, Ghafori R, Khalvati M, Eslamian A, Sharifi D, et al. Death anxiety and related factors among older adults in Iran: findings from a National Study. Salmand Iran J Ageing. 2024;19(1):144–57. https://doi.org/10.32598/sija.2023.1106.1

Partovirad M, Rizi S, Amrollah Majdabadi Z, Mohammadi F, Hosseinabadi A, Nikpeyma N. Assessing the relationship between spiritual intelligence and care burden in family caregivers of older adults with chronic diseases. 2024. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4343106/v1

Davarinia Motlagh Quchan A, Mohammadzadeh F, Mohamadzadeh Tabrizi Z, Bahri N. The relationship between spiritual health and COVID-19 anxiety among nurses: a national online cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):16356. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67523-7

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Türkben Polat H, Kiyak S. Spiritual well-being and care burden in caregivers of patients with breast cancer in Turkey. J Relig Health. 2023;62(3):1950–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01695-2 . Epub 2022 Dec 5. PMID: 36469230; PMCID: PMC9734401.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Francesco Chirico KB, Batra R, Ferrari G, Crescenzo P. Spiritual well-being and burnout syndrome in healthcare: asystematic review. School of Medicine Faculty Publications. 2023;15(3). https://doi.org/10.19204/2023/sprt2

Rezaei H, Niksima SH, Ghanei Gheshlagh R. Burden of care in caregivers of Iranian patients with chronic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01503-z . PMID: 32746921; PMCID: PMC7398060.

Kurtgöz A, Edis EK. Spiritual care from the perspective of family caregivers and nurses in palliative care: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2023;22(1):161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01286-2

Hosseini MA, Mohammadzaheri S, Fallahi Khoshkenab, Mohammadi Shahbolaghi M, Reza Soltani F, Sharif Mohseni M. Effect of mindfulness program on caregivers’ strain on Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. Salmand: Iran J Ageing. 2016;11(3):448–55. https://doi.org/10.21859/sija-1103448

Mahdavi B, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Mohammadi F, Hosseini MA, Haghi M. Effects of spiritual group therapy on caregiver strain in-home caregivers of the elderly with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(3):269–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.12.003

Moeini M, Ghasemi TMG, Yousefi H, Abedi HJIjon, Research M. The effect of spiritual care on the spiritual health of patients with cardiac ischemia. 2012;17(3):195. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23833611/

Parvizi S, Allahbakhshian M, Jafarpour allavi M, Haghani H. The relationship between spiritual health and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2000;12(3):29–33. https://civilica.com/doc/963361/

Google Scholar

Hamdami M, GHasemi jovineh R, Zahrakar K, Karimi K. The role of spiritual health and mindfulness in students’ psychological capital. Res Med Educ. 2015;8(2):2736. https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.rme.8.2.27

Abbasi A, Ashraf Rezaei N, Asayesh H, Shariati A, Rahmani H, Molaei E, et al. Relationship between caregiving pressure and coping skills of caregivers of patients undergoing hemodialysis. Urmia School Nurs Midwifery. 2011;10(4):533–9.

Pouladi S ss, Bahreyni M, Bagherzadeh R. The effect of spiritual-religious psychotherapy on self-concept and sense of coherence in cancer patients of Bushehr City, 2017–2018. Bushehr University of Medical Sciences.

Modarres MAS. Effect of religion-based spirituality education on happiness of postmenopausal women: an interventional study. Health Spiritual Med Ethics. 2021;8(1):44–54. https://doi.org/10.29252/jhsme.8.1.44

Jahdi F, mA B, Mahani M, Behboudi Moghaddam Z. The effect of prenatal group care on the empowerment of pregnant women. Payesh. 2014;13(2):229–34.

Sayyadi M, Sayyad S, Vahabi A, Vahabi B, Noori B, Amani M. Evaluation of the spiritual health level and its related factors in the students of Sanandaj Universities, 2015. Shenakht J Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;6(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.22122/cdj.v6i3.332

Koburtay TJD, Aljafari A. Religion, spirituality, and well-being: a systematic literature review and futuristic agenda. Bus Ethics Environ Responsib. 2023;32(1):41–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12478

Casaleiro TMH, Caldeira S. Promoting spiritual coping of family caregivers of an adult relative with severe mental illness development and test of a nursing intervention. Healthcare. 2024;12(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12131247

Xavier FT, Esperandio MRG. Spirituality and caregiver burden of people with intellectual disabilities: an empirical study. Int J Latin Am Religions. 2023;7(1):17–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-023-00196-8

Hekmatpour DB, EM.Dehkordi LM. The effect of patient care education on the burden of care and the quality of life of caregivers of stroke patients. Multidisciplinary Healthc. 2019;12(2):7–11. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S232970 . PMID: 30936715; PMCID: PMC6430991.

Shoghi MN, Seyedfatemi., Shahbazi B. M S. The effect of family-center empowerment model(FCEM) on the care burden of the patient of children diagnosed with cancer. 2019;20(6):1757–68. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.6.1757

Khalili Z, Habibi E, Kamyari N, Tohidi S, Yousofvand V. Correlation between spiritual health, anxiety, and sleep quality among cancer patients. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2024;20:100668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2024.100668

Salmoirago-Blotcher EFG, Leung K, Volturo G, Boudreaux E, Crawford S, et al. An exploration of the role of religion/spirituality in the promotion of physicians’ well-being in emergency medicine. Prev Med Rep. 2016;1(3):189–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.01.009 . PMID: 27419014; PMCID: PMC4929145.

Karadag Arli SBA, Erisik E. An investigation of the relationship between nurses’ views on spirituality and spiritual care and their level of burnout. J Holist Nurs. 2017;35(3):214–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010116652974 . Epub 2016 May 30. PMID: 27241132.

Jafari M, Alipour F, Raheb G, Mardani M. Perceived stress and burden of care in elderly caregivers: the moderating role of resilience Salmand. Iran J Ageing. 2022;17(1):62–75. https://doi.org/10.32598/sija.2021.2575.2

Mohammadi F, Babaie M. The impact of participation in support groups on spiritual health and care burden of elderly patients with Alzheimer’s family caregivers. Iran J Ageing. 2012;12(19):29–37. https://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-374-en.html

Rahgooy AF, Sojoudi M. T. Investigating the effect of the empowerment program on the care burden of mothers with children with phenylketonuria and the level of phenylalanine in the children’s serum. TEHRAN: University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Welfare; 2016.

Sotoudeh RPS, Alavi M. The effect of a family-based training program on the care burden of family caregivers of patients undergoing hemodialysis. Iran J Nurse Midwifery Res. 2019;24(2):144. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_93_18 . PMID: 30820227; PMCID: PMC6390430.

Salehi Nejad S, Azami M, Motamedi F, Bahaadinbeigy K, Sedighi B, Shahesmaili A. The effect of web-based information intervention in caregiving burden in caregivers of patients with dementia. J J Health Biomedical Inf. 2017;4(3):181–91. https://www.sid.ir/fa/VEWSSID/J_pdf/3007513960302.pdf

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the Student Research Committee, the Persian Gulf Martyrs Hospital’s Clinical Research Development Center, and all the elderly caregivers who participated in this research, as their contributions were invaluable.

Research expenses by the vice president of research and the student research committee of Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Iran, have been paid.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Islamic Republic of Iran

Afifeh Qorbani

Nursing and Midwifery Faculty of Bushehr, University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Islamic Republic of Iran

Shahnaz Pouladi & Razieh Bagherzadeh

Persian Gulf Tropical Medicine Research Center, Persian Gulf Biomedical Sciences Research Institute, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Islamic Republic of Iran

Akram Farhadi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AQ: Student. Author of the article. SH: Supervisor, the editor, preparation of educational packages. AF.: Consultant professor, the editor, preparation of educational packages. RB: Consultant professor of statistics department, the editor.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shahnaz Pouladi .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

The research has an ethics code number of IR.BPUMS.REC.1399.042 from the Research Vice-Chancellor of Bushehr University of Medical Sciences. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Qorbani, A., Pouladi, S., Farhadi, A. et al. The impact of religious spiritual care training on the spiritual health and care burden of elderly family caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a field trial study. BMC Nurs 23 , 584 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02268-2

Download citation

Received : 29 May 2024

Accepted : 16 August 2024

Published : 24 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02268-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Caregiver burden

- Spirituality

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 28 August 2024

Transforming simulation in healthcare to enhance interprofessional collaboration leveraging big data analytics and artificial intelligence

- Salman Yousuf Guraya 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 941 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Simulation in healthcare, empowered by big data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI), has the potential to drive transformative innovations towards enhanced interprofessional collaboration (IPC). This convergence of technologies revolutionizes medical education, offering healthcare professionals (HCPs) an immersive, iterative, and dynamic simulation platform for hands-on learning and deliberate practice. Big data analytics, integrated in modern simulators, creates realistic clinical scenarios which mimics real-world complexities. This optimization of skill acquisition and decision-making with personalized feedback leads to life-long learning. Beyond clinical training, simulation-based AI, virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR) automated tools offer avenues for quality improvement, research and innovation, and team working. Additionally, the integration of VR and AR enhances simulation experience by providing realistic environments for practicing high-risk procedures and personalized learning. IPC, crucial for patient safety and quality care, finds a natural home in simulation-based education, fostering teamwork, communication, and shared decision-making among diverse HCP teams. A thoughtful integration of simulation-based medical education into curricula requires overcoming its barriers such as professional silos and stereo-typing. There is a need for a cautious implantation of technology in clinical training without overly ignoring the real patient-based medical education.

Peer Review reports

Simulation in healthcare, powered by big data analytics (BDA) and artificial intelligence (AI), stands at the forefront of transformative innovations with a promise to facilitating interprofessional collaboration (IPC). This convergence of technologies towards educational philosophies not only revolutionizes medical training but also enhances the quality of care and patient safety in an IPC climate for an efficient delivery of healthcare system [ 1 ]. Simulation in healthcare showcases a controlled, versatile, and safe environment for healthcare professionals (HCPs) from diverse disciplines to engage in hands-on learning with deliberate practice [ 2 ]. Learners are engrossed in immersive, iterative, and interactive climate which can nurture opportunities for the acquisition of transferable psychomotor and cognition-based skills [ 3 ]. A simulated environment nurtures the real jest of life-long learning where learners can be trained by deliberate practice till the acquisition of their skills.

BDA, embedded in modern cutting-edge simulators, can utilize enormous healthcare data for clinical training and skills acquistion [ 4 ]. For instance, Bateman and Wood employed Amazon’s Web Service to accumulate a complete human genomic scaffold including 140 million individual base pairs by adopting an advanced hashing algorithm [ 5 ]. Later, a BDA platform successfully matched patients’ data of children in hospital to their whole-genome sequencing for the management of potentially incurable clinical conditions [ 6 ]. From another perspective, leveraging clinical scenarios with realism, BDA can be a valuable tool in reflecting the complexities of the real-world medical practice. This data-driven approach diligently mimics the variability and inconsistency encountered in real clinical settings, preparing HCPs for diverse patient encounters and crisis management. Artificial intelligence (AI) with its machine learning algorithm (MLA) and natural language processing (NLP) further fortifies the impact of simulation by enabling adaptive learning experiences [ 7 ]. Moreover, AI-powered patient simulators with automated interfaces can demonstrate high fidelity realistic physiological responses such as pulse, blood pressure, breathing patterns, and facial expressions to allow learners to practice decision-making in lifelike scenarios. By analyzing simulation data, institutions can identify trends, best practices, and areas for improvement, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and advancing medical knowledge.

Applications of BDA harness the experimental usage of electronic health records, medical imaging, genetic information, and patients’ demographics. By aggregating and analyzing this data, simulation platforms can create realistic scenarios that can be used by learners for clinical reasoning and critical decision-making. Additionally, MLA and NLP have the ability to predict disease prognosis, treatment efficacy, and unwanted outcomes, thereby offering a reliable hub for interactive and immersive learning for HCPs [ 8 ]. MLA and NLP encourage adaptive learning experiences by analyzing learner interactions and performance in real-time. This unique opportunity of acquiring skills mastery with personalized feedback either by simulator, peer, or facilitator makes simulation a master-class educational and training tool for all HCPs. For instance, if a learner consistently makes errors in decision-making or a procedural skill, a smart simulator can tailor further exercises to provide targeted practice opportunities for individual learners.

Clinical training is interposed at the crossroads of adopting AI, virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR) technologies. Beyond training, simulation-driven medical education holds immense potential for quality improvement and research in healthcare [ 9 ]. VR and AR technologies offer immersive experiences that simulate clinical settings with unprecedented realism. VR headsets transform learners into a cyber space where they deal with animations, digital images, and a host of other exercises in virtual climate [ 10 ]. AR overlays digital information onto the physical world, allowing learners to visualize anatomical structures, medical procedures, or patient data in real-time. Moreover, VR and AR can be used to perform high risk medical procedures till the complete acquisition of skill mastery. Such opportunity is not possible due to threats to patient safety and limited time for learners’ training in real-world workplaces [ 11 ]. At the same time, the mapping of learners’ needs with the curriculum is possible only in simulated environment where learners’ expectations can be tailored to meet their learning styles [ 11 ]. AI, VR, and AR technologies in healthcare simulators essentially empower learners to develop clinical expertise, enhance patient care, and drive innovations in healthcare delivery.

An example of integration of AI, NP, ML, and certain other algorithms in simulation is the sepsis management of a virtual patient being managed by a team of HCPs from different healthcare disciplines. A patient presents with fever, confusion, and rapid breathing in the emergency room. AI platform creates a detailed medical record of the patient with past hospital visits, medications, allergies, and baseline health metrics. AI simulates patient’s symptoms in real-time with tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and fever. The trainees interview the virtual patient and AI responds, using NLP, by providing coherent and contextually appropriate answers. The trainees order a set of tests, including blood cultures, a complete blood count, and lactate levels. AI presents realistic test results where blood cultures show a bacterial infection, leukocytosis, and elevated lactate levels. Based on the diagnosis of sepsis, the trainees plan treatment which typically includes oxygen, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and intravenous fluid. AI then adjusts the patient condition based on the trainees’ actions which may lead to improvement in clinical parameters. However, a delayed treatment could lead to worsening symptoms such as septic shock. Furthermore, AI can introduce complications if initial treatments were ineffective or if the trainees commit errors. Thereupon, AI provides real-time feedback on the trainees’ decisions which can highlight missed signs, suggest alternative diagnostic tests, or recommend adjustments to treatment plans. Lastly, AI would generate a summary report of the performance with a breakdown of diagnostic accuracy, treatment efficacy, and adherence to clinical guidelines. MLAs analyze patterns in patient data to assist in diagnosis. In this context, decision trees and neural networks of MLAs analyze vast datasets of patient records to create realistic virtual patients with diverse medical histories and clinical conditions.

There has been a proliferation of empirical research about the powerful role of IPC in medical education [ 12 , 13 ]. IPC fosters shared decision-making, role identification and negotiations, team coherence, and mitigates potential errors [ 14 ]. Through simulated scenarios, HCPs learn to navigate interdisciplinary challenges, appreciate each other’s roles, and develop a shared approach to patient care. Additionally, simulation in healthcare faces the challenges of costs, access, development, and ethical considerations. Nevertheless, the integration of simulation, BDA, VR, AR, and AI heralds a new era of IPC in healthcare, where learning, practice, and innovation converge to shape the future of medicine.

The overarching goal of all healthcare systems focuses on patient safety as reiterated by the World Health Organization (WHO) sustainable development goals [ 15 ]. General Medical Council, Irish Medical Council, Canada MEDs, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and EmiatesMEDS are also in agreement with WHO and, in this context, IPC can potentially enhance the quality of care and patient safety [ 16 ]. Though the role of IPC is widely accepted, there is a lukewarm response from medical institutions about its integration into the existing curricula. Professional silos, stereotyping, bureaucratic inertia, and resistant mindsets are some of the deterring factors [ 17 ]. In the era of simulation in healthcare, IPC can be efficiently embedded into this technology-powered educational tool for impactful collaborative teamwork. By harnessing the technological power of VR, AR, and AI, simulation platforms can leverage the indigenous advantage of IPC in clinical training. Once skills acquisition is accomplished in the simulated platform, its recreation in the real world would be a seamless transition of transferable skills.

To sum up, despite an exponential growth in the use of technology-driven simulation in healthcare, educators should be mindful of its careful integration in medical curricula. Clinical training on real patients cannot be replaced by any strategy or tool regardless of its perceived efficiency or effectiveness. Bearing in mind the learning styles of our learners with a preference toward fluid than crystalloid verbal comprehension and fluid reasoning, technology-driven simulation plays a vital role in medical education. A thoughtful integration of simulation pitched at certain courses and modules spiraled across the curriculum will enhance the learning experience of medical and health sciences students and HCPs [ 18 ].

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Choudhury A, Asan O. Role of artificial intelligence in patient safety outcomes: systematic literature review. JMIR Med Inf. 2020;8(7):e18599.

Article Google Scholar

Higgins M, Madan CR, Patel R. Deliberate practice in simulation-based surgical skills training: a scoping review. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(4):1328–39.

Watts PI, McDermott DS, Alinier G, Charnetski M, Ludlow J, Horsley E, et al. Healthcare simulation standards of best practiceTM simulation design. Clin Simul Nurs. 2021;58:14–21.

Chrimes D, Moa B, Zamani H, Kuo M-H, editors. Interactive healthcare big data analytics platform under simulated performance. 2016 IEEE 14th Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, 14th Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, 2nd Intl Conf on Big Data Intelligence and Computing and Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/DataCom/CyberSciTech); 2016: IEEE.

Bateman A, Wood M. Cloud computing. Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 1475.

Twist GP, Gaedigk A, Miller NA, Farrow EG, Willig LK, Dinwiddie DL, et al. Constellation: a tool for rapid, automated phenotype assignment of a highly polymorphic pharmacogene, CYP2D6, from whole-genome sequences. NPJ Genomic Med. 2016;1(1):1–10.

Winkler-Schwartz A, Bissonnette V, Mirchi N, Ponnudurai N, Yilmaz R, Ledwos N, et al. Artificial intelligence in medical education: best practices using machine learning to assess surgical expertise in virtual reality simulation. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(6):1681–90.

Li WT, Ma J, Shende N, Castaneda G, Chakladar J, Tsai JC, et al. Using machine learning of clinical data to diagnose COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2020;20:1–13.

Google Scholar

Caffò AO, Tinella L, Lopez A, Spano G, Massaro Y, Lisi A, et al. The drives for driving simulation: a scientometric analysis and a selective review of reviews on simulated driving research. Front Psychol. 2020;11:917.

Hsieh M-C, Lee J-J. Preliminary study of VR and AR applications in medical and healthcare education. J Nurs Health Stud. 2018;3(1):1.

Forgione A, Guraya SY. The cutting-edge training modalities and educational platforms for accredited surgical training: a systematic review. J Res Med Sci. 2017;22(1):51.

Sulaiman N, Rishmawy Y, Hussein A, Saber-Ayad M, Alzubaidi H, Al Kawas S, et al. A mixed methods approach to determine the climate of interprofessional education among medical and health sciences students. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:1–13.

Guraya SY, David LR, Hashir S, Mousa NA, Al Bayatti SW, Hasswan A, et al. The impact of an online intervention on the medical, dental and health sciences students about interprofessional education; a quasi-experimental study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:1–11.

Wei H, Corbett RW, Ray J, Wei TL. A culture of caring: the essence of healthcare interprofessional collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(3):324–31.

Organization WH. Global patient safety action plan 2021–2030: towards eliminating avoidable harm in health care. World Health Organization; 2021.

Guraya SS, Umair Akhtar M, Sulaiman N, David LR, Jirjees FJ, Awad M, et al. Embedding patient safety in a scaffold of interprofessional education; a qualitative study with thematic analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):968.

Supper I, Catala O, Lustman M, Chemla C, Bourgueil Y, Letrilliart L. Interprofessional collaboration in primary health care: a review of facilitators and barriers perceived by involved actors. J Public Health. 2015;37(4):716–27.

Guraya SS, Guraya SY, Al-Qahtani MF. Developing a framework of simulation-based medical education curriculum for effective learning. Med Educ. 2020;24(4):323–31.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Vice Dean College of Medicine, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Salman Yousuf Guraya

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

This is a sole author manuscript. Salman Guraya conceived, prepraed, revieweed, revised, and finalized this editorial artcile.

Corresponding author