- Past Issues

- Industry Statistics

- Members Only

- Best Places to Work

- General Interest

- Exploration & Development

- Drilling & Production

- Refining & Processing

- Pipelines & Transportation

- Energy Transition

Quantitative risk assessment improves refinery safety

Risk analysis for installations containing large amounts of flammable substances is important to ensure safety and to meet legal requirements.

This article deals with a quantitative risk assessment (QRA) of a typical LPG storage installation that is common in many refineries. An incident in the isobutene tank may cause a "domino effect" due to its location.

QRA allows one to identify and rank incidents that contribute to total risk. A methodology based on the risk concept that considers the dependence between hazard potential and associated safeguards is an effective way to assess plant safety. The proposed methodology allows a calculation of individual and social risk curves.

Plant safety systems consist of multiple layers of a safeguard system in which each layer represents an appropriate risk-reduction level. Semiquantitative methods that use a multilayer risk matrix can help one evaluate the risk-reduction level.

This refinery installation did not meet acceptable risk criteria; a possible domino effect increased individual and societal risk. Proposed adequate safety and protection measures lowered the associated risk.

Refinery risks

Refineries have many dangerous substances and processes that have a high potential for safety hazards. Most refineries are near densely populated, urban residential and industrial areas, and ecosystems.

A risk analysis of the possibility and scale of explosions or fires is important so that operators can provide adequate precautionary, protective, and preventive measures. QRA achieves this task. 1

The QRA in this article calculates potential consequences of a flammable substance release and individual and social risk curves.

Refinery LPG storage

LPGs are produced in many refining processes including: atmospheric distillation, vacuum distillation, hydrocracking, catalytic cracking, reforming, and isomerization. These gases usually appear in the light stage (wet gas); after purification and separation they are collected in storage tanks as C3 and C4. They can then be used for other petrochemical processes.

Pumps and a piping system link the storage tanks in a refinery. They are used for temporary storage or as supply sources for the production lines. Tanks usually have a capacity of 200-400 cu m, and are often situated close to the production units and control room. They can cause a domino effect if unexpected developments occur.

The chemical composition of LPG obtained from refining processes varies from location to location and can contain simple alkanes, alkenes, small-molecule olefins, and other cyclical and aromatic hydrocarbons.

When modeling the releases and dispersions of these mixtures, one must therefore consider the specific composition.

Risk management

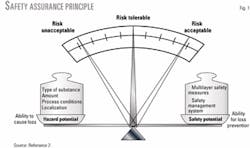

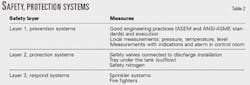

Risk management is based on the assessment of relations between existing hazards and applied safety and protection systems. Fig. 1 illustrates the concept.

Many different hazards in refineries represent a relatively fixed fire and explosion potential. They are measured with any semiquantitative technique or full consequence analysis. 1-3

Various safety systems help mitigate safety hazards. Guidelines of the Center for Chemical Process Safety (CCPS) of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE) organize safety systems into a multi-layer system: 4

•Layer 1 is a prevention layer responsible for minimizing chemical releases. This layer consists of basic process control systems, process alarms, and operators and their responses. This layer mainly concerns the likelihood of chemical releases.

•Layer 2 is a protection layer comprising the automatic protection of an installation after releases or after critical alarms. It includes safety instrument systems (safety valves, trips, interlocks, emergency shut-down devices), blowdown systems, emergency cooling, fire fighting, and explosion protection. This layer considers the likelihood and consequences of chemical releases.

•Layer 3 is the response layer. It consists of chemical-release mitigation and includes the actions of firefighters and rescue services.

Characteristic features of multilayer safety systems include:

•The sequential, serial, and independent activities of each safety layer.

•The assumption that each safety layer is a barrier to develop hazards and may consist of sublayers.

•The assumption that the initiating event for the release incident was a failure of elements in the prevention layer.

•Each layer's risk reduction level can be calculated separately based on Bayes theorem.

•The effectiveness of each layer depends on the safety management system and applicability of best available technologies (BAT).

The relation between existing hazards and safeguard system is unique to each installation. A detailed analysis of hazards and connected safety measures, especially the layers of protection, is necessary when one evaluates and assesses risk.

QRA incident selection

The first step in the QRA is to select the most representative set of incidents (RSI). Hazard identification techniques help identify a wide range of incidents that are the basis for selection.

A possible accidental release of chemicals or energy, however, can be large due to a variety of possible ruptures or leaks occurring in different locations and sizes of piping or vessels.

Each release incident can expand into a release incident outcome (RIO) depending on the propagation, safeguards, and mitigation measures. A risk evaluation must account for these outcomes.

There is no well-grounded methodology that satisfies the risk study requirements that also adequately represents all hazards and safeguards.

Our approach applied the "multi-layer risk matrix" (MRM). 5 Fig. 2 shows the matrix in which each layer of protection is represented by a separate risk matrix with a specific categorization of the risk component.

The frequency, consequences, and risk levels include:

- Frequency. Five categories from very frequent (10 -1 -year -1 ) to very rare (> 10 -4 year -1 ).

- Consequence severity. Five categories from catastrophic to negligible.

- Risk level, four categories:

- Low, acceptable risk (A), no need for further action.

- Low, tolerable risk (TA), action based on ALARP principle.

- Tolerable risk (TNA), improvements must be made in the long-term.

- Unacceptable risk (NA), must reduce immediately.

One can use these steps to evaluate the risk level using MLM:

- Identify the safety systems (safety layers).

- Determine an initiating event and its frequency (generic).

- Determine the initial consequence, C0 (generic).

- Evaluate the risk-reduction level for Layer 1.

- Evaluate the risk-reduction level for Layer 2.

- Evaluate the risk-reduction level for Layer 3.

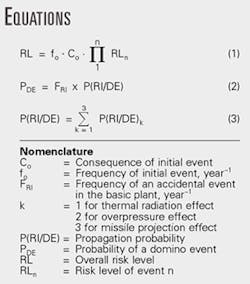

- Evaluate the risk level, RL (Equation 1 in the accompanying equations box).

Scenario for LPG releases

Incidents and types of hazards accompanying gas releases depend on the characteristics of the release source and external conditions in the release area, including:

- An ignition source, either immediate or delayed.

- An LPG leakage point; i.e., above the LPG surface (tank's vapor phase) or in the liquid phase.

- Size of the leakage.

- Nature of the leakage, continuous or instantaneous.

Storage installations have many potential leak points such as small openings in the wall or faulty seals, as well as catastrophic ruptures like pipeline ruptures or an opening in the tank with a diameter larger than the largest connection.

Publications from the Institute of Chemical Engineers (IChemE) cover standard hole-size guidelines. 6

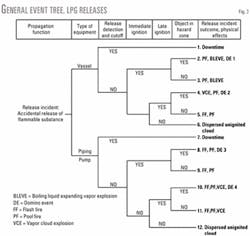

One can develop different RIOs for a flammable substance release incident (RI) using the event tree in Fig. 3.

It shows that some outcome cases can further develop into different domino events.

It may happen if only the hazard zone, where particular physical effects exceed a threshold value, envelopes adjacent vulnerable objects.

Assessing domino effects

If the domino effects are covered in legal requirements then it is important to include them in final QRA results. 7

The European Union (EU) defines "domino effect" as the effect of a major accident in a basic plant causing a release of a dangerous substance from an adjacent plant or nearby site as the result of direct or indirect interrelation.

"Domino" is more serious than an "escalation," which usually refers to one particular plant. There are two types of domino events:

- A direct domino event caused by the interaction of containment events.

- An indirect domino event caused by a small leak due to equipment failure, loss of utilities, human error, or an ineffective mitigation system.

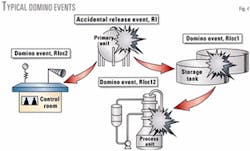

A typical feature of the domino effect is a chain of incidents that may be in series or parallel. Fig. 4 shows a characteristic pattern of domino effects in a chemical plant.

A release incident (RI) can have three different physical effects: shock wave, thermal radiation, and missile projection.

Each of these physical effects generates a hazard zone in which the values of particular effects exceed threshold values; therefore, a particular domino event may occur.

Different factors can influence the domino process, which are specific for each type of event. The most important factors include:

- Type of equipment.

- Type of substance involved.

- Adjacent equipment and its vulnerability.

- Distance from the RI and arrangement of subsequent equipment.

- Propagation conditions like ignition sources, wind direction, and mitigation efforts.

The damage level from a domino event depends on the distance involved, propagation conditions, and vulnerability of adjacent equipment.

The impact of various physical effects on humans, buildings, and industrial installations vary according to the source. 3 8 9

Table 1 shows the most common threshold criteria. There is no universal threshold value for missile projection. The Committee for the Prevention of Disasters' Yellow Book provides a calculation procedure for predicting missile range. 10

The QRA should consider additional domino event scenarios.

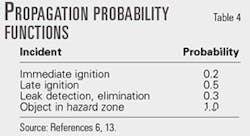

One must calculate the probability of a domino event, PDE, and the consequence of that event using Equations 2 and 3. 3

An estimate of P(RI/DE) should account for propagation mechanisms; for a particular type of physical effect, three different approaches apply for this estimate:

- Based on Probit functions.

- Based on empirical data.

- Worst-case scenario.

The last approach assumes that the propagation probability equals 1 if the vulnerable target is inside the hazard zone for the particular physical effect.

Domino-event consequences are catastrophic and calculated similar to release incidents that consider the appropriate conditions: type of the substance, amount, conditions before release, and external propagation conditions.

A domino event can also occur outside the hazard zone of a critical physical effect; however, the probability and consequence of this event is significantly smaller and it was not taken into account.

Fig. 5 shows the methodology of considering domino top events in calculating individual and societal risk.

Isobutane storage case study

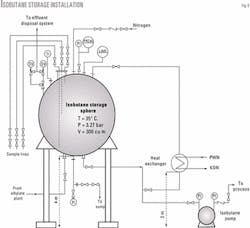

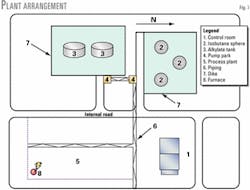

A typical isobutane storage tank was situated within a production installation in a refinery and consisted of: three 300-cu m spherical tanks, a system of pumps, heat exchangers, and appropriate linking pipelines.

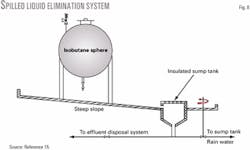

Fig. 6 shows the installation scheme and Fig. 7 shows the location of the storage installation.

We assumed these meteorological conditions: air humidity 70%, dominating class of atmospheric stability was very stable (F) and neutral (D), wind velocity was 2 m/sec and 5 m/sec, respectively, and the dominant wind direction was southwest.

About 34 m from the installation are two 2,000-cu m cylindrical floating roof tanks that store gasoline.

About 44 m from the isobutane tank are a control room and a production installation.

A flask furnace is a direct ignition source and sits about 100 m from the isobutane storage tank.

Table 2 shows the installation's safety and protection systems.

RSI identification

We analyzed the principal causes of failures in isobutane and butane tanks using 21 historical data points collected in the Accident Database. 11

Overfilling, overpressure, mechanical failure, human error, and external events are the most frequent causes.

When a release and gas dispersion into the atmosphere without ignition was reported, the breakdown of various incidents was: boiling liquid expanding vapor explosions (BLEVEs) 14%, vapor cloud explosions (VCEs) 43%, pool fires (PFs) 19%, and flash fires (FFs) 24%.

In a primary hazard assessment (PHA), we evaluated 17 incidents using a typical four-level risk matrix. We could therefore obtain three RIs representing tolerable risk that still belong to the same group of releases.

Table 3 shows six RIs that represent two types of seal failures, rupture and leakage. We included domino event incidents because, as later calculations prove, the hazard zone enveloped neighboring objects (Fig. 7).

We used the event tree (Fig. 3) to calculate the outcome incident frequencies for RI DE 7-RI DE 10.

Generic data from literature sources served as the basis for data concerning the frequency of certain RIs. 3 6 12 13

Table 4 shows the propagation functions that we used.

Domino events

A commercial software package helped perform the calculations. 14 It enabled the calculation of the potential consequences of releases of flammable substances, and individual and societal risk curves.

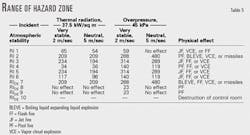

The first calculations identified the hazard zone for the release incidents accounting for these threshold criteria:

- Thermal radiation of 37.5 kw/sq m.

- Overpressure of 45 kPa.

The radius, based on the distance from release source to the threshold value, forms the hazard zone, which is the impact area where domino effects may occur.

Table 5 shows the calculated range of hazard zones for all release incidents. These objects, which are possible targets for domino effects, are inside the impact area:

- Neighboring spherical isobutane tank.

- Atmospheric gasoline tank.

- Process piping.

- Control room with four operators.

Because all these targets are sources of subsequent domino events (RI DE 7-RI DE 10), we calculated similar risk probabilities and consequences.

Table 5 shows the calculation results. Because RI DE 8 and RI DE 9 do not form a hazard zone, they do not contribute to the individual and societal risk estimate.

Calculation option selection

We considered six options to show the impact of domino effects as well as the effects of RSIs on individual and social risk:

- Option 1 included six release incidents, RI 1-RI 6.

- Option 2 eliminated incident RI 2 that led to the BLEVE. A proposal to install a liquid elimination system allowed us to delete incident RI 2 (Fig. 8).

- Option 3 is similar to Option 1 and includes an additional domino incident, RI DE 7.

- Option 4 included RI 1-RI 6 and all domino events RI DE 7 - RI DE 10.

- Option 5 is Option 2 plus an additional domino incident, RI DE 8, due to possible missile projection.

- Option 6 is Option 4 with a modification to the societal risk; the population density was changed from 0.002 to 0.0005 persons/sq m.

Risk calculation results

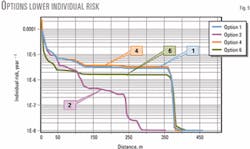

Figs. 9 and 10 show the calculation results for Options 1, 2, 4, and 6.

Individual and social risks vary with the selected RSIs. Different sets of release scenarios generate different risk characteristics. This is a key point in risk analysis.

Only Options 2 and 5 have an acceptable individual risk level of 10 -6 year -1 at 110 m because we eliminated the BLEVE factor. The acceptable individual risk level was 350 m from the storage tanks for the other options. All domino events included in Option 4 have a negligible effect on individual risk.

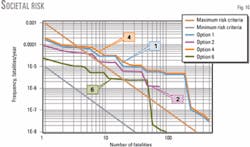

Fig. 10 presents societal risk as the cumulative risk of multiple fatalities as a function of the number of fatalities.

Most of the societal risk curves are above the recommended limits of maximum risk criteria. Options 2, 5, and 6, which eliminate the BLEVE scenario, give the best results.

The societal risk ranking analysis shows that the major contributors to off-site societal risk are RI 2 and RI 6, which account for over 75% of the fatalities. This knowledge helps target areas for risk mitigation measures.

Additionally, the domino events do not have an appreciable impact on the total societal risk especially for higher number of fatalities. In fact, the increase is just 18% for Option 4, which includes all identified domino events.

RI DE 7 has the greatest impact on social risk, 8.8%. RI DE 8, RI DE 9, and RI 10, in terms of probabilities and consequences, are negligible.

Table 6 presents total societal risk for entire hazard area.

Option 6, which assumes a smaller population, provides the greatest risk reduction level. Options 2 and 5 also reduce the total risk level that results from the proposal presented in Fig. 8.

Acknowledgment

This article constitutes a part of studies financed by the grant 7 T09C 022 20 of the Polish Committee for Scientific Research.

- "Guidelines for chemical process quantitative risk analysis," AIChE Center for Chemical Process Safety, New York, 2000.

- "Zapobieganie Stratom w Przemysle- cz.III Zarzadzanie bezpieczenstwem procesowym," Markowski, A.S., ed., Wyd. Politechnika Lodzka, 2000.

- Lees, F.P., Loss prevention in process industries, Butterworths, London, 1996.

- Guidelines for engineering design for process safety, AIChE Center for Chemical Process Safety, New York, 1993.

- Markowski, A.S., "Multi-layer risk matrix for process installations," International Conference on Safety and Reliability, KONBiN 2001, ITWL, 2001, pp. 213-22.

- Cox, A.W., Lees, F.P., and Ang, M.L., "Classification of hazardous location," IChemE, 1990.

- "The control of major-accident hazards involving dangerous substances (COMAH)," 96/82/EC, Official Journal of the European Communities, 1, 1997.

- TNO, "Method for the determination of possible damage to people and objects resulting from releases from hazardous materials," 1979.

- "The effects of explosion in the process industries-overpressure monographs," IChemE, 1989.

- "Methods for the calculation of physical effects," Yellow Book, CPR14E, The Committee for the Prevention of Disasters, The Hague, 1997.

- The Accident Database, version 4, IChemE, Rugby, UK, 2000.

- Offshore reliability data, 3rd ed., Offshore Reliability Data, SINTEF IM, Norway, 1997.

- "Guidelines for quantitative risk assessment," Purple Book, The Committee for the prevention of Disasters, The Hague, 1999.

- "SafetiMicro, Software for assessment of fire &toxic impact," DNV, UK, 2001

- "Guidelines for engineering design for process safety," CCPS, AIChE, 1993.

Adam S. Markowski is a senior lecturer in the department of environmental engineering systems at the Technical University of Lodz, Poland. He is also head of its safety and environmental management group. His research interests include industrial process safety, risk and safety management, loss prevention in the process industries, and thermal explosions in the process industries. Markowski holds an MSc (1965) and a PhD (1972), both in chemical engineering from the Technical University of Lodz.

Based on a presentation to the 2001 Annual Symposium of the Mary Kay O'Connor Process Safety Center, Texas A&M University, College Station, Tex., Oct. 30-31, 2001.

Continue Reading

Ecuador terminates Oxy's Block 15 contract

AUDITING REDUCES ACCIDENTS BY ELIMINATING UNSAFE PRACTICES

Latest in home.

Brazos Midstream advances Permian gas processing, gathering buildout

Shell sanctions waterflood project at Gulf of Mexico Vito field

BPCL taps Lummus technologies for Bina refinery’s petrochemical project

Strike Energy granted Perth basin production license

Accessibility Links

- Skip to content

- Skip to search IOPscience

- Skip to Journals list

- Accessibility help

- Accessibility Help

Click here to close this panel.

Purpose-led Publishing is a coalition of three not-for-profit publishers in the field of physical sciences: AIP Publishing, the American Physical Society and IOP Publishing.

Together, as publishers that will always put purpose above profit, we have defined a set of industry standards that underpin high-quality, ethical scholarly communications.

We are proudly declaring that science is our only shareholder.

Risk Assessment on Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Handling Facility, Case Study: Terminal LPG Semarang

T A Akbar 1,2 , A A B Dinariyana 1,2 , A Baheramsyah 1 , F I Prastyasari 1,2 and P D Setyorini 2,3

Published under licence by IOP Publishing Ltd IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering , Volume 588 , Indonesia Malaysia Research Consortium Seminar 2018 (IMRCS 2018) 21–22 November 2018, East Java, Indonesia Citation T A Akbar et al 2019 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 588 012007 DOI 10.1088/1757-899X/588/1/012007

Article metrics

989 Total downloads

Share this article

Author e-mails.

Author affiliations

1 Department of Marine Engineering, Faculty of Marine Technology, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember Surabaya, Indonesia, 60111

2 Centre of Excellences of Maritime Safety and Marine Installation (PUI-KEKAL) Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember Surabaya

3 Department of Marine Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Marine Sciences, Hang Tuah University Surabaya, Indonesia

Buy this article in print

LPG plays important role in Indonesia as household fuel. With the rapid growth of LPG usage, its handling facility is built across the country. The handling of LPG requires various activity prior to supporting its supply chain. One of the vital facility is Terminal LPG (or on this case Terminal LPG Semarang) which serve as a hub in LPG distribution because it handles a relatively huge amount of LPG. It is exposed to operational risk especially fire risk. This paper is intended to assess the risk of LPG Terminal by using combined both qualitative and quantitative methods. The initial step is to identify the hazard by using HAZOP Study. The next step is to determine the likelihood of the risk by using FTA and ETA resulted in event frequency. The severity level is determined using consequences analysis which involved fire modeling of the intended scenarios. The result from both frequency and consequences will be presented in the risk matrix to determine the unacceptable risk scenario to develop a mitigation plan by using Fire Risk Card to assess the capability of the Terminal firefighting equipment.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence . Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

- Publications

- AHFE Access

- Instructions

- Aims and scope

- Volumes & Issues

- Editorial Board

- AHFE Conference Series

Risk Assessment for LPG Storage

Abstract: in view of the growing prices of petrol and oil, the interest of drivers in liquefied propane-butane (lpg) as a fuel for cars rises. the number of storage tanks for car filling, both stand-alone tanks and tanks as part of petrol filling stations increases. prevention of accidents associated with lpg storage facilities is a priority in the protection of people in the vicinity of the facilities and equipment and forms an integral part of the management of system safety. the aim is to contribute to the prevention of accidents and incidents of process equipment with lpg based on the analysis of possible scenarios of accidents of lpg storage tanks and on the assessment of risks., keywords: major accident prevention, risk assessment methods, lpg, fuels, doi: 10.54941/10023, cite this paper: .css-i44wyl{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;-webkit-flex-direction:column;-ms-flex-direction:column;flex-direction:column;position:relative;min-width:0;padding:0;margin:0;border:0;vertical-align:top;} @-webkit-keyframes mui-auto-fill{from{display:block;}}@keyframes mui-auto-fill{from{display:block;}}@-webkit-keyframes mui-auto-fill-cancel{from{display:block;}}@keyframes mui-auto-fill-cancel{from{display:block;}} .css-1bn53lx{font-family:"roboto","helvetica","arial",sans-serif;font-weight:400;font-size:1rem;line-height:1.4375em;letter-spacing:0.00938em;color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.87);box-sizing:border-box;position:relative;cursor:text;display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;position:relative;border-radius:4px;padding-right:14px;}.css-1bn53lx.mui-disabled{color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.38);cursor:default;}.css-1bn53lx:hover .muioutlinedinput-notchedoutline{border-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.87);}@media (hover: none){.css-1bn53lx:hover .muioutlinedinput-notchedoutline{border-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.23);}}.css-1bn53lx.mui-focused .muioutlinedinput-notchedoutline{border-color:#1976d2;border-width:2px;}.css-1bn53lx.mui-error .muioutlinedinput-notchedoutline{border-color:#d32f2f;}.css-1bn53lx.mui-disabled .muioutlinedinput-notchedoutline{border-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.26);} .css-b52kj1{font:inherit;letter-spacing:inherit;color:currentcolor;padding:4px 0 5px;border:0;box-sizing:content-box;background:none;height:1.4375em;margin:0;-webkit-tap-highlight-color:transparent;display:block;min-width:0;width:100%;-webkit-animation-name:mui-auto-fill-cancel;animation-name:mui-auto-fill-cancel;-webkit-animation-duration:10ms;animation-duration:10ms;padding-top:1px;padding:8.5px 14px;padding-right:0;}.css-b52kj1::-webkit-input-placeholder{color:currentcolor;opacity:0.42;-webkit-transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;}.css-b52kj1::-moz-placeholder{color:currentcolor;opacity:0.42;-webkit-transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;}.css-b52kj1:-ms-input-placeholder{color:currentcolor;opacity:0.42;-webkit-transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;}.css-b52kj1::-ms-input-placeholder{color:currentcolor;opacity:0.42;-webkit-transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:opacity 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;}.css-b52kj1:focus{outline:0;}.css-b52kj1:invalid{box-shadow:none;}.css-b52kj1::-webkit-search-decoration{-webkit-appearance:none;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1::-webkit-input-placeholder{opacity:0important;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1::-moz-placeholder{opacity:0important;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1:-ms-input-placeholder{opacity:0important;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1::-ms-input-placeholder{opacity:0important;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1:focus::-webkit-input-placeholder{opacity:0.42;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1:focus::-moz-placeholder{opacity:0.42;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1:focus:-ms-input-placeholder{opacity:0.42;}label[data-shrink=false]+.muiinputbase-formcontrol .css-b52kj1:focus::-ms-input-placeholder{opacity:0.42;}.css-b52kj1.mui-disabled{opacity:1;-webkit-text-fill-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.38);}.css-b52kj1:-webkit-autofill{-webkit-animation-duration:5000s;animation-duration:5000s;-webkit-animation-name:mui-auto-fill;animation-name:mui-auto-fill;}.css-b52kj1:-webkit-autofill{border-radius:inherit;} .css-1nvf7g0{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;height:0.01em;max-height:2em;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;white-space:nowrap;color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.54);margin-left:8px;} .css-1wf493t{text-align:center;-webkit-flex:0 0 auto;-ms-flex:0 0 auto;flex:0 0 auto;font-size:1.5rem;padding:8px;border-radius:50%;overflow:visible;color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.54);-webkit-transition:background-color 150ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:background-color 150ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;}.css-1wf493t:hover{background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.04);}@media (hover: none){.css-1wf493t:hover{background-color:transparent;}}.css-1wf493t.mui-disabled{background-color:transparent;color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.26);} .css-1yxmbwk{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;position:relative;box-sizing:border-box;-webkit-tap-highlight-color:transparent;background-color:transparent;outline:0;border:0;margin:0;border-radius:0;padding:0;cursor:pointer;-webkit-user-select:none;-moz-user-select:none;-ms-user-select:none;user-select:none;vertical-align:middle;-moz-appearance:none;-webkit-appearance:none;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;color:inherit;text-align:center;-webkit-flex:0 0 auto;-ms-flex:0 0 auto;flex:0 0 auto;font-size:1.5rem;padding:8px;border-radius:50%;overflow:visible;color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.54);-webkit-transition:background-color 150ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:background-color 150ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;}.css-1yxmbwk::-moz-focus-inner{border-style:none;}.css-1yxmbwk.mui-disabled{pointer-events:none;cursor:default;}@media print{.css-1yxmbwk{-webkit-print-color-adjust:exact;color-adjust:exact;}}.css-1yxmbwk:hover{background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.04);}@media (hover: none){.css-1yxmbwk:hover{background-color:transparent;}}.css-1yxmbwk.mui-disabled{background-color:transparent;color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.26);} .css-vubbuv{-webkit-user-select:none;-moz-user-select:none;-ms-user-select:none;user-select:none;width:1em;height:1em;display:inline-block;fill:currentcolor;-webkit-flex-shrink:0;-ms-flex-negative:0;flex-shrink:0;-webkit-transition:fill 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:fill 200ms cubic-bezier(0.4, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;font-size:1.5rem;} .css-19w1uun{border-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.23);} .css-igs3ac{text-align:left;position:absolute;bottom:0;right:0;top:-5px;left:0;margin:0;padding:0 8px;pointer-events:none;border-radius:inherit;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;overflow:hidden;min-width:0%;border-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.23);} .css-ihdtdm{float:unset;width:auto;overflow:hidden;padding:0;line-height:11px;-webkit-transition:width 150ms cubic-bezier(0.0, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;transition:width 150ms cubic-bezier(0.0, 0, 0.2, 1) 0ms;} .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Quantitative Area Risk Analysis to Support Decision on Lpg Depots and Land Use Planning

2008, Journal of Konbin

The Quantitative Area Risk Analysis to Support Decision on Lpg Depots and Land Use PlanningIn Italy, for assessing LPG depots, a simplified method has been used for twelve years. The method is based on the classification of the plant according the MOND index. Standardized accidental scenarios are applied to have damage areas. Land vulnerability and compatibility are evaluated according a method inspired by the IAEA method for land use compatibility. In this paper it has been demonstrated credible, as their results are confirmed by using a higher level method, such as the well known method defined in the TNO purple book.

Related Papers

Quantified risk assessment in major industrial areas is a valuable tool, which can be used in order to both assess the existing risk as well as to rationalize emergency preparedness and land use planning. Thriassion Plain and Thessalonica are the two major industrial regions in Greece. They both have a significant concentration of industries, which lie under the Seveso II directive. Specifically, installations that produce, store, bottle and distribute LPG are considered to pose significant risks to the surrounding areas. Quantified risk assessment has been performed for those two areas and is presented in this study.

Giovanni Francalanza

Quantitative Area Risk Assessment (QARA) techniques were used to evaluate the local, individual and social risk in an Italian industrial area. The changes in the risk values for population were evaluated with respect to different land-use options proposed for risk reduction. Even if more work is needed to develop straightforward procedures for the quantitative evaluation of some accidental scenarios, the QARA techniques proved to be a powerful decision-making tool in order to evaluate the impact on industrial risk of alternative land-use solutions. The European Directive 96/82/EC (better known as "Seveso-II" Directive) requires the implementation of land use planning criteria for the minimization of industrial risk caused by the production, the use and the storage of hazardous substances. The proposed Italian implementation of the Directive identifies 25 areas where the high concentration of sites involving the manipulation of hazardous substances requires a comprehensive ...

IAEME Publication

The Risk Assessment is an important legal requirement which should be carried out in industries in order to prevent any incident in future and manage emergencies better. In this article a typical LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) storage bullet of capacity 14.7m 3 and truck tanker of capacity 18 m 3 were selected for the study. Risk assessment was carried out for various fire scenarios such as BLEVE, VCE, and Jet fire which can happen in LPG storage area. The inputs used in the estimation are collected from various articles and from a typical LPG handling and storing industry in the southern part of Tamil Nadu. The meteorological conditions for the assumed Madurai region are given as an input data in the ALOHA software for dispersion predictions of various scenarios. The accident situations are selected from various reports and literatures of LPG storages around the world. By using the ALOHA software, the dispersion models are used to estimate dispersion concentrations, Blast effects, Flammable effects, Thermal radiation and Toxic effects. The results are arrived from the predicted and user defined inputs in ALOHA software with the references and industrial investigations.

Iranian Journal of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering-international English Edition

Farshad Nourai

Safety distance has already been a main measurement for the hazard control of chemical installations interpreted to mean providing space between the hazardous installation and different types of targets. But, the problem is how to determine the enough space. This study considers the application of quantitative risk assessment to evaluating a compressed natural gas station site and to identify nearby land use limitations. In such cases, the most important consideration is to assure that the proposed site would not be incompatible with existing land uses in the vicinity. This scope is possible by categorization of estimated levels of risk imposed by the proposed site. It means that an analysis of the consequences and likelihood of credible accident scenarios coupled with general acceptable risk criteria should be undertaken. This enables the calculated risk of the proposed site to be considered at an early stage, to allow prompt responses or in the later stages to observe limitations....

The Open Ecology Journal

Irina Priputina

Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries

Bahman Abdolhamidzadeh , genserik reniers

This study considers the application of quantitative risk assessment (QRA) on the siting of compressed natural gas (CNG) stations and determining nearby land use limitations. In such cases the most important consideration is to be assured that the proposed site would not be incompatible with existing land uses in the vicinity. It is possible by the categorization of the estimated levels of individual risk (IR) which the proposed site would impose upon them. An analysis of the consequences and likelihood of credible accident scenarios coupled with acceptable risk criteria is then undertaken. This enables the IR aspects of the proposed site to be considered at an early stage to allow prompt responses or in the later stages to observe limitations. According to the results in many cases not only required distances have not been provided but also CNG stations are commonly located in vicinity of populated areas to facilitate refueling operations. This is chiefly because of inadequate risk...

Safety and reliability. …

Zoe Nivolianitou

This paper deals with the uncertainties present in the results of risk assessment of chemical installations and it examines their implications to land-use planning decisions. In particular, the results from the EU funded research project ASSURANCE are used as a case-study. Three types of ...

Genserik Reniers , Hans Pasman

Journal of Hazardous Materials

Genserik Reniers

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Alexandru Ozunu

Natural Hazards

Adriana Galderisi

Land Use Policy

Viorel-Ilie Arghius

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering

D. Peter Shin

Thaisa De Sá , Erick Galante , Assed Haddad

Franco Oboni

Periodica Polytechnica Chemical Engineering

Luboš Kotek

Chemical engineering transactions

jan kerstens

Jerome TIXIER

American Journal of Applied Sciences

Mara Lombardi

Mahdi Maleki

Journal of Failure Analysis and Prevention

Rachid CHAIB

Safety Science

Vipin Upadhyay

Proceedings of the …

Igor Kozine

DR MOHD FARIS KHAMIDI

Chemical Engineering Transactions

Angel Irabien

Reliability Engineering & System Safety

Mark Cunningham

LALIT GABHANE

DAN SERBANESCU

prevenzioneoggi.ispesl.it

Eleonora Bottani

Proposed Rule

Design Updates: As part of our ongoing effort to make FederalRegister.gov more accessible and easier to use we've enlarged the space available to the document content and moved all document related data into the utility bar on the left of the document. Read more in our feature announcement .

Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Species Status for Cedar Key Mole Skink and Designation of Critical Habitat

A Proposed Rule by the Fish and Wildlife Service on 08/08/2024

This document has a comment period that ends in 46 days. (10/07/2024) Submit a formal comment

Thank you for taking the time to create a comment. Your input is important.

Once you have filled in the required fields below you can preview and/or submit your comment to the Interior Department for review. All comments are considered public and will be posted online once the Interior Department has reviewed them.

You can view alternative ways to comment or you may also comment via Regulations.gov at https://www.regulations.gov/commenton/FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053-0001 .

- What is your comment about?

Note: You can attach your comment as a file and/or attach supporting documents to your comment. Attachment Requirements .

this will NOT be posted on regulations.gov

- Opt to receive email confirmation of submission and tracking number?

- Tell us about yourself! I am... *

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- State Alabama Alaska American Samoa Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Guam Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Puerto Rico Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Texas Utah Vermont Virgin Islands Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming

- Country Afghanistan Åland Islands Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia, Plurinational State of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Bouvet Island Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Colombia Comoros Congo Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Cook Islands Costa Rica Côte d'Ivoire Croatia Cuba Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia French Southern Territories Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Heard Island and McDonald Islands Holy See (Vatican City State) Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran, Islamic Republic of Iraq Ireland Isle of Man Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jersey Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Republic of Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Lao People's Democratic Republic Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macao Macedonia, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova, Republic of Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine, State of Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Pitcairn Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Réunion Romania Russian Federation Rwanda Saint Barthélemy Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Martin (French part) Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Sint Maarten (Dutch part) Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Svalbard and Jan Mayen Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syrian Arab Republic Taiwan, Province of China Tajikistan Tanzania, United Republic of Thailand Timor-Leste Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States United States Minor Outlying Islands Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of Viet Nam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, U.S. Wallis and Futuna Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

- Organization Type * Company Organization Federal State Local Tribal Regional Foreign U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate

- Organization Name *

- You are filing a document into an official docket. Any personal information included in your comment text and/or uploaded attachment(s) may be publicly viewable on the web.

- I read and understand the statement above.

- Preview Comment

This document has been published in the Federal Register . Use the PDF linked in the document sidebar for the official electronic format.

- Document Details Published Content - Document Details Agencies Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Agency/Docket Numbers Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053 FXES1111090FEDR-245-FF09E21000 CFR 50 CFR 17 Document Citation 89 FR 65124 Document Number 2024-17271 Document Type Proposed Rule Pages 65124-65160 (37 pages) Publication Date 08/08/2024 RIN 1018-BH41 Published Content - Document Details

- View printed version (PDF)

- Document Dates Published Content - Document Dates Comments Close 10/07/2024 Dates Text We will accept comments received or postmarked on or before October 7, 2024. Comments submitted electronically using the Federal eRulemaking Portal (see ADDRESSES, below) must be received by 11:59 p.m. eastern time on the closing date. We must receive requests for a public hearing, in writing, at the address shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT by September 23, 2024. Published Content - Document Dates

This table of contents is a navigational tool, processed from the headings within the legal text of Federal Register documents. This repetition of headings to form internal navigation links has no substantive legal effect.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Supplementary information:, executive summary, information requested, public hearing, previous federal actions, peer review, summary of peer reviewer comments, i. proposed listing determination, regulatory and analytical framework, regulatory framework, analytical framework, summary of biological status and threats, subspecies needs, climate change, conservation efforts and regulatory mechanisms, cumulative effects, current condition, representation, determination of cedar key mole skink's status, status throughout all of its range, status throughout a significant portion of its range, determination of status, available conservation measures, ii. critical habitat, physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species, summary of essential physical or biological features, special management considerations or protection, criteria used to identify critical habitat, proposed critical habitat designation, unit 1: live oak key, unit 2: cedar point, unit 3: scale key, unit 4: dog island, unit 5: atsena otie key, unit 6: snake key, unit 7: seahorse key, unit 8: north key, unit 9: airstrip island, unit 10: way key south, unit 11: way key north, unit 12: richards island, unit 13: seabreeze island, unit 14: shell mound, unit 15: raleigh and horse islands, unit 16: deer island, unit 17: clark islands, effects of critical habitat designation, section 7 consultation, destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat, application of section 4(a)(3) of the act, consideration of impacts under section 4(b)(2) of the act, consideration of economic impacts, consideration of national security impacts, consideration of other relevant impacts, summary of exclusions considered under 4(b)(2) of the act, required determinations, clarity of the rule, regulatory planning and review (executive orders 12866, 13563, and 14094), regulatory flexibility act ( 5 u.s.c. 601 et seq.), energy supply, distribution, or use— executive order 13211, unfunded mandates reform act ( 2 u.s.c. 1501 et seq.), takings— executive order 12630, federalism— executive order 13132, civil justice reform— executive order 12988, paperwork reduction act of 1995 ( 44 u.s.c. 3501 et seq.), national environmental policy act ( 42 u.s.c. 4321 et seq.), government-to-government relationship with tribes, references cited, list of subjects in 50 cfr part 17, signing authority, proposed regulation promulgation, part 17—endangered and threatened wildlife and plants.

Comments are being accepted - Submit a public comment on this document .

3 comments have been received at Regulations.gov.

Agencies review all submissions and may choose to redact, or withhold, certain submissions (or portions thereof). Submitted comments may not be available to be read until the agency has approved them.

| Docket Title | Document ID | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Proposed Endangered status and Critical Habitat for the Cedar Key mole skink | 3 |

FederalRegister.gov retrieves relevant information about this document from Regulations.gov to provide users with additional context. This information is not part of the official Federal Register document.

Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Proposed Endangered status and Critical Habitat for the Cedar Key mole skink

- Sharing Enhanced Content - Sharing Shorter Document URL https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2024-17271 Email Email this document to a friend Enhanced Content - Sharing

- Print this document

Document page views are updated periodically throughout the day and are cumulative counts for this document. Counts are subject to sampling, reprocessing and revision (up or down) throughout the day.

This document is also available in the following formats:

More information and documentation can be found in our developer tools pages .

This PDF is the current document as it appeared on Public Inspection on 08/07/2024 at 8:45 am.

It was viewed 0 times while on Public Inspection.

If you are using public inspection listings for legal research, you should verify the contents of the documents against a final, official edition of the Federal Register. Only official editions of the Federal Register provide legal notice of publication to the public and judicial notice to the courts under 44 U.S.C. 1503 & 1507 . Learn more here .

Document headings vary by document type but may contain the following:

- the agency or agencies that issued and signed a document

- the number of the CFR title and the number of each part the document amends, proposes to amend, or is directly related to

- the agency docket number / agency internal file number

- the RIN which identifies each regulatory action listed in the Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions

See the Document Drafting Handbook for more details.

Department of the Interior

Fish and wildlife service.

- 50 CFR Part 17

- [Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053; FXES1111090FEDR-245-FF09E21000]

- RIN 1018-BH41

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

Proposed rule.

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), propose to list the Cedar Key mole skink ( Plestiodon egregius insularis ), a lizard subspecies from the Cedar Keys, Florida, as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). After a review of the best available scientific and commercial information, we find that listing this subspecies is warranted. We also propose to designate critical habitat for the Cedar Key mole skink under the Act. In total, approximately 2,713 acres (1,098 hectares) in Levy County, Cedar Keys, Florida, fall within the boundaries of the proposed critical habitat designation. In addition, we announce the availability of an economic analysis of the proposed designation of critical habitat for the Cedar Key mole skink. If we finalize this rule as proposed, it would extend the Act's protections to this subspecies and its designated critical habitat.

We will accept comments received or postmarked on or before October 7, 2024. Comments submitted electronically using the Federal eRulemaking Portal (see ADDRESSES , below) must be received by 11:59 p.m. eastern time on the closing date. We must receive requests for a public hearing, in writing, at the address shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT by September 23, 2024.

You may submit comments by one of the following methods:

(1) Electronically: Go to the Federal eRulemaking Portal: https://www.regulations.gov . In the Search box, enter FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053, which is the docket number for this rulemaking. Then, click on the Search button. On the resulting page, in the panel on the left side of the screen, under the Document Type heading, check the Proposed Rule box to locate this document. You may submit a comment by clicking on “Comment.”

(2) By hard copy: Submit by U.S. mail to: Public Comments Processing, Attn: FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, MS: PRB/3W, 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA 22041-3803.

We request that you send comments only by the methods described above. We will post all comments on https://www.regulations.gov . This generally means that we will post any personal information you provide us (see Information Requested, below, for more information).

Availability of supporting materials: Supporting materials, such as the species status assessment report, are available on the Service's website at https://www.fws.gov/office/florida-ecological-services/library and at https://www.regulations.gov at Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053. For the proposed critical habitat designation, the coordinates or plot points or both from which the maps are generated are included in the decision file for this critical habitat designation and are available at https://www.regulations.gov at Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053 and on the Service's website at https://www.fws.gov/office/florida-ecological-services/library .

Lourdes Mena, Division Manager, Classification and Recovery, Florida Ecological Services Field Office, 7915 Baymeadows Way, Suite 200, Jacksonville, FL 32256-7517; [email protected] ; telephone 352-749-2462. Individuals in the United States who are deaf, deafblind, hard of hearing, or have a speech disability may dial 711 (TTY, TDD, or TeleBraille) to access telecommunications relay services. Individuals outside the United States should use the relay services offered within their country to make international calls to the point-of-contact in the United States. Please see Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2024-0053 on https://www.regulations.gov for a document that summarizes this proposed rule.

Why we need to publish a rule. Under the Act ( 16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq. ), a species warrants listing if it meets the definition of an endangered species (in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range) or a threatened species (likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range). If we determine that a species warrants listing, we must list the species promptly and designate the species' critical habitat to the maximum extent prudent and determinable. We have determined that the Cedar Key mole skink meets the Act's definition of an endangered species; therefore, we are proposing to list it as endangered and proposing a designation of its critical habitat. Both listing a species as an endangered or threatened species and making a critical habitat designation can be completed only by issuing a rule through the Administrative Procedure Act rulemaking process ( 5 U.S.C. 551 et seq. ).

What this document does. We propose to list the Cedar Key mole skink as an endangered species under the Act, and we propose the designation of critical habitat for the subspecies.

The basis for our action. Under the Act, we may determine that a species is an endangered or threatened species because of any of five factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. We have determined that the Cedar Key mole skink is endangered due to threats associated with climate change, specifically sea level rise, increased high tide flooding, and increased intensity of storm events (Factor E).

Section 4(a)(3) of the Act requires the Secretary of the Interior (Secretary), to the maximum extent prudent and determinable, concurrently with listing designate critical habitat for the species. Section 3(5)(A) of the Act defines critical habitat as (i) the specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed, on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protections; and (ii) specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed, upon a determination by the Secretary that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. Section 4(b)(2) of the Act states that the Secretary must make the designation on the basis of the best scientific data available and after taking into consideration the economic impact, the impact on national security, and any other relevant impacts of specifying any particular area as critical habitat. ( print page 65125)

We intend that any final action resulting from this proposed rule will be based on the best scientific and commercial data available and be as accurate and as effective as possible. Therefore, we request comments or information from other governmental agencies, Native American Tribes, the scientific community, industry, or any other interested parties concerning this proposed rule. We particularly seek comments concerning:

(1) The subspecies' biology, range, and population trends, including:

(a) Biological or ecological requirements of the subspecies, including habitat requirements for feeding, breeding, and sheltering;

(b) Genetics and taxonomy;

(c) Historical and current range, including distribution patterns and the locations of any additional populations of this subspecies;

(d) Historical and current population levels, and current and projected trends; and

(e) Past and ongoing conservation measures for the subspecies, its habitat, or both.

(2) Threats and conservation actions affecting the subspecies, including:

(a) Factors that may be affecting the continued existence of the subspecies, which may include habitat modification or destruction, overutilization, disease, predation, the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms, or other natural or humanmade factors;

(b) Biological, commercial trade, or other relevant data concerning any threats (or lack thereof) to this subspecies; and

(c) Existing regulations or conservation actions that may be addressing threats to this subspecies.

(3) Additional information concerning the historical and current status of this subspecies.

(4) Specific information on:

(a) The amount and distribution of Cedar Key mole skink habitat;

(b) Any additional areas occurring within the range of the subspecies, the Cedar Keys in Levy County, Florida, that should be included in the critical habitat designation because they (i) are occupied at the time of listing and contain the physical or biological feature that is essential to the conservation of the subspecies and that may require special management considerations or protection, or (ii) are unoccupied at the time of listing and are essential for the conservation of the subspecies;

(c) Special management considerations or protection that may be needed in the critical habitat areas we are proposing, including managing for the potential effects of climate change; and

(d) Whether areas not occupied at the time of listing qualify as habitat for the species and are essential for the conservation of the species.

(5) Land use designations and current or planned activities and their possible impacts on proposed critical habitat.

(6) Any probable economic, national security, or other relevant impacts of designating any area that may be included in the final designation, and the related benefits of including or excluding specific areas.

(7) Information on the extent to which the description of probable economic impacts in the economic analysis is a reasonable estimate of the likely economic impacts and any additional information regarding probable economic impacts that we should consider.

(8) Whether any specific areas we are proposing for critical habitat designation should be considered for exclusion under section 4(b)(2) of the Act, and whether the benefits of potentially excluding any specific area outweigh the benefits of including that area under section 4(b)(2) of the Act. If you think we should exclude any additional areas, please provide information supporting a benefit of exclusion.

(9) Whether we could improve or modify our approach to designating critical habitat in any way to provide for greater public participation and understanding, or to better accommodate public concerns and comments.

Please include sufficient information with your submission (such as scientific journal articles or other publications) to allow us to verify any scientific or commercial information you include.

Please note that submissions merely stating support for, or opposition to, the action under consideration without providing supporting information, although noted, do not provide substantial information necessary to support a determination. Section 4(b)(1)(A) of the Act directs that determinations as to whether any species is an endangered or a threatened species must be made solely on the basis of the best scientific and commercial data available, and section 4(b)(2) of the Act directs that the Secretary shall designate critical habitat on the basis of the best scientific data available.

You may submit your comments and materials concerning this proposed rule by one of the methods listed in ADDRESSES . We request that you send comments only by the methods described in ADDRESSES .

If you submit information via https://www.regulations.gov , your entire submission—including any personal identifying information—will be posted on the website. If your submission is made via a hardcopy that includes personal identifying information, you may request at the top of your document that we withhold this information from public review. However, we cannot guarantee that we will be able to do so. We will post all hardcopy submissions on https://www.regulations.gov .

Comments and materials we receive, as well as supporting documentation we used in preparing this proposed rule, will be available for public inspection on https://www.regulations.gov .

Our final determination may differ from this proposal because we will consider all comments we receive during the comment period as well as any information that may become available after the publication of this proposal. Based on the new information we receive (and, if relevant, any comments on that new information), we may conclude that the subspecies is threatened instead of endangered, or we may conclude that the subspecies does not warrant listing as either an endangered species or a threatened species. For critical habitat, our final designation may not include all areas proposed, may include some additional areas that meet the definition of critical habitat, or may exclude some areas if we find the benefits of exclusion outweigh the benefits of inclusion and exclusion will not result in the extinction of the subspecies. In our final rule, we will clearly explain our rationale and the basis for our final decision, including why we made changes, if any, that differ from this proposal.

Section 4(b)(5) of the Act provides for a public hearing on this proposal, if requested. Requests must be received by the date specified in DATES . Such requests must be sent to the address shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT . We will schedule a public hearing on this proposal, if requested, and announce the date, time, and place of the hearing, as well as how to obtain reasonable accommodations, in the Federal Register and local newspapers at least 15 days before the hearing. We may hold the public hearing in person or virtually via webinar. We will announce any public hearing on our website, in addition to the Federal Register . The use of virtual public ( print page 65126) hearings is consistent with our regulations at 50 CFR 424.16(c)(3) .

On July 11, 2012, we received a petition from the Center for Biological Diversity to list the Cedar Key mole skink as an endangered or threatened species under the Act. On July 1, 2015, we published in the Federal Register ( 80 FR 37568 ) a 90-day finding that the petition provided substantial information indicating that listing the Cedar Key mole skink may be warranted. On December 19, 2018, we published in the Federal Register ( 83 FR 65127 ) a 12-month finding that the Cedar Key mole skink did not warrant listing under the Act. On January 26, 2022, the Center for Biological Diversity filed suit against the Service, alleging the Service did not use the best available scientific data regarding sea level rise and its impacts to Cedar Key mole skink habitat in its 12-month finding. In May 2022, the Service agreed to submit a new finding to the Federal Register by July 31, 2024. This finding and proposed rule reflect the updated assessment of the status of the Cedar Key mole skink based on the best available science, including an updated species status assessment for the subspecies (Service 2023, entire).

A species status assessment (SSA) team prepared an SSA report for the Cedar Key mole skink. The SSA team was composed of Service biologists, in consultation with other species experts. The SSA report represents a compilation of the best scientific and commercial data available concerning the status of the subspecies, including the impacts of past, present, and future factors (both negative and beneficial) affecting the subspecies.

In accordance with our joint policy on peer review published in the Federal Register on July 1, 1994 ( 59 FR 34270 ), and our August 22, 2016, memorandum updating and clarifying the role of peer review in listing and recovery actions under the Act, we solicited independent scientific review of the information contained in the Cedar Key mole skink SSA report. We sent the SSA report to six independent peer reviewers and received one response. Results of this structured peer review process can be found at https://www.regulations.gov and https://www.fws.gov/office/florida-ecological-services . In preparing this proposed rule, we incorporated the results of this review, as appropriate, into the SSA report, which is the foundation for this proposed rule.

As discussed in Peer Review above, we received comments from one peer reviewer on the draft SSA report. We reviewed the comments for substantive issues and new information regarding the contents of the SSA report. The peer reviewer generally concurred with our methods and conclusions, and provided additional information, clarifications, and suggestions, including clarifications in terminology and other editorial suggestions.

The peer reviewer suggested that our statement that “rafting is rare, but does occur” was inappropriate. The peer reviewer noted that there is no evidence that rafting occurs in the Cedar Key mole skink (or any mole skink subspecies) and that, in fact, genetic evidence suggests the opposite (that there is no movement of mole skinks among islands). We updated the SSA report to indicate that rafting is unlikely.

The peer reviewer also commented that our analysis of “potential habitat” on the two developed islands, Way Key and Airstrip Island, was an overrepresentation of the amount of habitat truly available to the Cedar Key mole skink. In our initial analysis, we included high intensity and low intensity urban data layers for these islands as part of our calculation of potential habitat available because skinks have been found in backyards, in parking lots, along roadsides, and in other disturbed or developed areas. However, these data layers also included roads, buildings, and other developed areas, which are not considered habitat for the Cedar Key mole skink. As a result, our use of these data layers increased what we had identified as potential habitat on Airport Island from 1.00 acre (0.40 hectares) to 52.43 acres (21.0 hectares), and on Way Key from 2.65 acres (1.07 hectares) to 266.14 acres (107.70 hectares). We agree with the peer reviewer that the use of the urban areas in our analysis overestimated the amount of habitat truly available to the Cedar Key mole skink. Thus, we restricted our analysis of these two islands to only include the preferred habitat data layers that included beaches, dunes, and coastal hammock. We included the additional analysis focused on high-intensity and low-intensity urban areas on Way Key and Airport Island as part of appendix A in the SSA report.

A thorough review of the taxonomy, life history, and ecology of the Cedar Key mole skink ( Plestiodon egregius insularis ) is presented in the SSA report (Service 2023, pp. 2-16). The Cedar Key mole skink is one of five distinct subspecies of mole skinks in Florida, all in the genus Plestiodon (previously Eumeces ) (Brandley et al. 2005, pp. 387-388), and is endemic to the Cedar Keys, Florida. This subspecies represents a unique genetic lineage that is distinct from the other four mole skink subspecies (Brandley et al. 2005, pp. 387-388; Parkinson et al. 2016, entire). The Cedar Key mole skink is the largest of the five subspecies, approaching 15 centimeters (5.9 inches), with the tail accounting for two-thirds of the length.

The Cedar Key mole skink is semi-fossorial (adapted to digging, burrowing, and living underground) and cryptic in nature. The Cedar Key mole skink is a cold-blooded reptile and therefore highly dependent air and soil temperature to thermoregulate (maintain body core temperature) (Mount 1963, p. 362). Ground cover moderates soil temperatures and provides shade to assist in the skinks' thermoregulation in hot climate. The optimum temperature range for the mole skink species ( Plestiodon egregius ) is 26 to 34 degrees Celsius (C) (78.8 to 93.2 degrees Fahrenheit (F)) with a mean of 29.5 C (85.1 F) (Mount 1963, p. 363). Mole skinks are considered thermoconformers, lacking the capacity to adjust or regulate to changes in temperature outside of this stable and relatively narrow thermal range in which it occurs (Gallagher et al 2015, p. 62).

The specific diet of Cedar Key mole skink is unknown, but in general, skinks in the genus Plestiodon are known to eat ants, spiders, crickets, beetles, termites, small bugs, mites, and butterfly larva (Hamilton and Pollack 1958, p, 26). Native snakes are considered natural predators of mole skinks (Hamilton and Pollack 1958, p. 28, Mount 1963, p. 356) and domestic and feral cats on some islands in the Cedar Keys are known to prey on skink populations (Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC) 2013, p.5). The Cedar Key mole skink relies on dry, unconsolidated soils for movement, cover, and nesting, and it needs detritus, leaves, wrack, and other ground cover for shelter, temperature regulation, and food (insects and arthropods found in ground cover).

The Cedar Keys are a coastal complex of islands, tidal creeks, bays, and salt marsh, located along 10 miles (16 kilometers) of Florida's central Gulf of Mexico coast in Levy County. The Cedar Key mole skink has been found in small numbers on 10 islands of the Cedar ( print page 65127) Keys archipelago (see figure 1, below). Eight of these islands are currently considered occupied (skink detections documented between 2000 to 2022), and two of these islands are considered to have uncertain status (skink detections documented prior to 1999, but not resurveyed) (Mount 1963, entire; Mount 1965 entire; FWC 2023, entire). In total, 215 Cedar Key mole skinks have been detected, with 62 individuals documented since 2000. Within this limited range, the Cedar Key mole skink is found most frequently in sand beach and coastal dune habitats. The estimated home range of a Cedar Key mole skink is approximately a 328-ft (100-meter) radius (Service 2023, p. 12).

The Cedar Keys archipelago is a relatively small coastal ecosystem of 30 or more, mostly undeveloped islands of varying size and elevations. Of the eight current islands with known Cedar Key mole skink occurrence, only one island, Airstrip Island, is developed. Deer Island, also occupied by the Cedar Key mole skink, is privately owned with one dwelling and could be further developed with a small number of (off-the-grid) dwellings. Way Key, the largest island within the Cedar Keys, where the City of Cedar Key is located, is mostly developed, but the Cedar Key mole skink population status there is uncertain. The remaining islands with known populations of the Cedar Key mole skink are undeveloped and largely protected as part of the Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuge. There are other islands of the Cedar Keys archipelago that contain suitable habitat and soils for the Cedar Key mole skink, but they have unknown occupancy due to lack of survey efforts. Many of these islands are also protected as conservation lands, and some are privately owned (all or in part) but remain undeveloped.

Section 4 of the Act ( 16 U.S.C. 1533 ) and the implementing regulations in title 50 of the Code of Federal Regulations set forth the procedures for determining whether a species is an endangered species or a threatened species, issuing protective regulations for threatened species, and designating critical habitat for endangered and threatened species. On April 5, 2024, jointly with the National Marine Fisheries Service, we issued a final rule that revised the regulations in 50 CFR part 424 regarding how we add, remove, and reclassify endangered and threatened species and what criteria we apply when designating listed species' critical habitat ( 89 FR 24300 ). On the same day, we published a final rule revising our protections for endangered species and threatened species at 50 CFR 17 ( 89 FR 23919 ). These final rules are now in effect and are incorporated into the current regulations.

The Act defines a “species” as including any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants, and any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature. The Act defines an “endangered species” as a species that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range, and a “threatened species” as a species that is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. The Act requires that we determine whether any species is an endangered species or a threatened species because of any of the following factors:

(A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range;

(B) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

(C) Disease or predation;

(D) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or

(E) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

These factors represent broad categories of natural or human-caused actions or conditions that could have an effect on a species' continued existence. In evaluating these actions and conditions, we look for those that may have a negative effect on individuals of the species, as well as other actions or conditions that may ameliorate any negative effects or may have positive effects.

We use the term “threat” to refer in general to actions or conditions that are known to or are reasonably likely to negatively affect individuals of a species. The term “threat” includes actions or conditions that have a direct impact on individuals (direct impacts), as well as those that affect individuals through alteration of their habitat or required resources (stressors). The term “threat” may encompass—either together or separately—the source of the action or condition or the action or condition itself.

However, the mere identification of any threat(s) does not necessarily mean that the species meets the statutory definition of an “endangered species” or a “threatened species.” In determining whether a species meets either definition, we must evaluate all identified threats by considering the species' expected response and the effects of the threats—in light of those actions and conditions that will ameliorate the threats—on an individual, population, and species level. We evaluate each threat and its expected effects on the species, then analyze the cumulative effect of all of the threats on the species as a whole. We also consider the cumulative effect of the threats in light of those actions and conditions that will have positive effects on the species, such as any existing regulatory mechanisms or conservation efforts. The Secretary determines whether the species meets the definition of an “endangered species” or a “threatened species” only after conducting this cumulative analysis and describing the expected effect on the species.