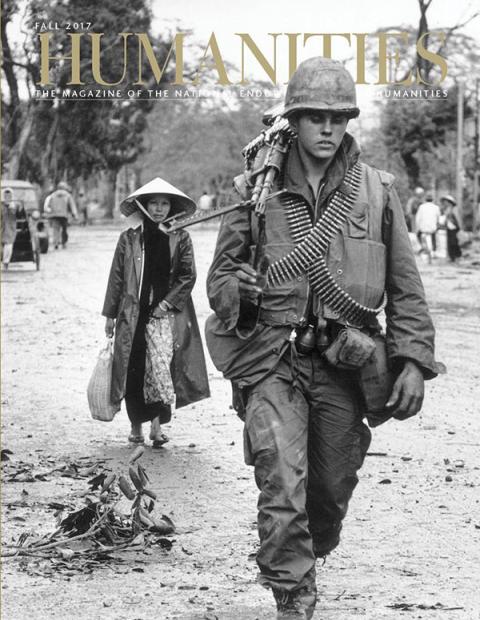

Sudden Death in Vietnam: ‘One Ride With Yankee Papa 13’

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13

Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Written By: Ben Cosgrove

In the spring of 1965, within weeks of 3,500 American Marines arriving in Vietnam, a 39-year-old Briton named Larry Burrows began work on a feature for LIFE magazine, chronicling the day-to-day experience of U.S. troops on the ground and in the air in the midst of the rapidly widening war. The photographs in this gallery focus on a calamitous March 31, 1965, helicopter mission; Burrows’ “report from Da Nang,” featuring his pictures and his personal account of the harrowing operation, was published two weeks later as a now-famous cover story in the April 16, 1965, issue of LIFE.

Over the decades, of course, LIFE published dozens of photo essays by some of the 20th century’s greatest photographers. Very few of those essays, however, managed to combine raw intensity and technical brilliance to such powerful effect as “One Ride With Yankee Papa 13” universally regarded as one of the greatest photographic documents to emerge from the war in Vietnam.

Here, LIFE.com presents Burrows’ seminal photo essay in its entirety: all of the photos that appeared in LIFE are here. (Note: In a picture from the article, Burrows mounts a camera to a special rig attached to an M-60 machine gun in helicopter YP13 a.k.a., “Yankee Papa 13.” At the end of this gallery, there are three previously unpublished photographs from Burrows’ 1965 assignment.]

Burrows, LIFE informed its readers, “had been covering the war in Vietnam since 1962 and had flown on scores of helicopter combat missions. On this day he would be riding in [21-year-old crew chief James] Farley’s machine and both were wondering whether the mission would be a no-contact milk run or whether, as had been increasingly the case in recent weeks, the Vietcong would be ready and waiting with .30-caliber machine guns. In a very few minutes Farley and Burrows had their answer.”

The following paragraphs lifted directly from LIFE illustrate the vivid, visceral writing that accompanied Burrows’ astonishing images, including Burrows’ own words, transcribed from an audio recording made shortly after the 1965 mission:

“The Vietcong dug in along the tree line, were just waiting for us to come into the landing zone,” Burrows reported. “We were all like sitting ducks and their raking crossfire was murderous. Over the intercom system one pilot radioed Colonel Ewers, who was in the lead ship: ‘Colonel! We’re being hit.’ Back came the reply: ‘We’re all being hit. If your plane is flyable, press on.’

“We did,” Burrows continued, “hurrying back to a pickup point for another load of troops. On our next approach to the landing zone, our pilot, Capt. Peter Vogel, spotted Yankee Papa 3 down on the ground. Its engine was still on and the rotors turning, but the ship was obviously in trouble. “Why don’t they lift off?’ Vogel muttered over the intercom. Then he set down our ship nearby to see what the trouble was.

“[Twenty-year-old gunner, Pfc. Wayne] Hoilien was pouring machine-gun fire at a second V.C. gun position at the tree line to our left. Bullet holes had ripped both left and right of his seat. The plexiglass had been shot out of the cockpit and one V.C. bullet had nicked our pilot’s neck. Our radio and instruments were out of commission. We climbed and climbed fast the hell out of there. Hoilien was still firing gunbursts at the tree line.”

Not until YP13 pulled away and out of range of enemy fire were Farley and Hoilien able to leave their guns and give medical attention to the two wounded men from YP3. The co-pilot, 1st Lt. James Magel, was in bad shape. When Farley and Hoilien eased off his flak vest, they exposed a major wound just below his armpit. “Magel’s face registered pain,” Burrows reported, “and his lips moved slightly. But if he said anything it was drowned out by the noise of the copter. He looked pale and I wondered how long he could hold on. Farley began bandaging Magel’s wound. The wind from the doorway kept whipping the bandages across his face. Then blood started to come from his nose and mouth and a glazed look came into his eyes. Farley tried mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but Magel was dead. Nobody said a word.”

In his searing, deeply sympathetic portrait of young men fighting for their lives at the very moment America is ramping up its involvement in Southeast Asia, Larry Burrows’ work anticipates the scope and the dire, lethal arc of the entire war in Vietnam.

Six years after “Yankee Papa 13” ran in LIFE, Burrows was killed, along with three other journalists Henri Huet, Kent Potter and Keisaburo Shimamoto when a helicopter in which they were flying was shot down over Laos in February, 1971. He was 44 years old.

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

LIFE_unpublished_slide

More Like This

Majesty in Tokyo: The 1964 Olympics

Eisenstaedt in Postwar Italy (and Yes, That’s Pasta)

A Young Actress Restarts Her Life in Postwar Paris

Eisenstadt’s Images of Change in the Pacific Northwest

Heartland Cool: Teenage Boys in Iowa, 1945

LIFE Said This Invention Would “Annihilate Time and Space”

Subscribe to the life newsletter.

Travel back in time with treasured photos and stories, sent right to your inbox

The Vietnam War, Part I: Early Years and Escalation

- Alan Taylor

- March 30, 2015

Fifty years ago, in March 1965, 3,500 U.S. Marines landed in South Vietnam. They were the first American combat troops on the ground in a conflict that had been building for decades. The communist government of North Vietnam (backed by the Soviet Union and China) was locked in a battle with South Vietnam (supported by the United States) in a Cold War proxy fight. The U.S. had been providing aid and advisors to the South since the 1950s, slowly escalating operations to include bombing runs and ground troops. By 1968, more than 500,000 U.S. troops were in the country, fighting alongside South Vietnamese soldiers as they faced both a conventional army and a guerrilla force in unforgiving terrain. Each side suffered and inflicted huge losses, with the civilian populace suffering horribly. Based on widely varying estimates, between 1.5 and 3.6 million people were killed in the war. This photo essay, part one of a three-part series, looks at the earlier stages of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, as well as the growing protest movement, between the years 1962 and 1967. Be sure to also see part 2 and part 3 . Warning: Several of these photographs are graphic in nature.

- Email/span>

Hovering U.S. Army helicopters pour machine gun fire into a tree line to cover the advance of South Vietnamese ground troops in an attack on a Viet Cong camp 18 miles north of Tay Ninh, near the Cambodian border, in March of 1965. #

An American officer serving with the South Vietnam forces poses with group of Montagnards in front of one of their provisionary huts in a military camp in central Vietnam on November 17, 1962. They were brought in by government troops from a village where they were used as labor force by communist Viet Cong forces. The Montagnards, dark-skinned tribesmen numbering about 700,000, live in the highlands of central Vietnam. The government was trying to win their alliance in its war with the Viet Cong. #

Vietnamese airborne rangers, their two U.S. advisers, and a team of 12 U.S. Special Forces troops set out to raid a Viet Cong supply base 62 miles northwest of Saigon, on August 6, 1963. As the H-21 helicopters hovered six feet from the ground to avoid spikes and wires and under sniper fire, the troops jumped out to attack. #

A South Vietnamese Marine, severely wounded in a Viet Cong ambush, is comforted by a comrade in a sugar-cane field at Duc Hoa, about 12 miles from Saigon, on August 5, 1963. A platoon of 30 Vietnamese Marines was searching for communist guerrillas when a long burst of automatic fire killed one Marine and wounded four others. #

Napalm air strikes raise clouds into gray monsoon skies as houseboats glide down the Perfume River toward Hue in Vietnam on February 28, 1963, where a battle for control of the old Imperial City ended with a Communist defeat. Firebombs were directed against a village on the outskirts of Hue. #

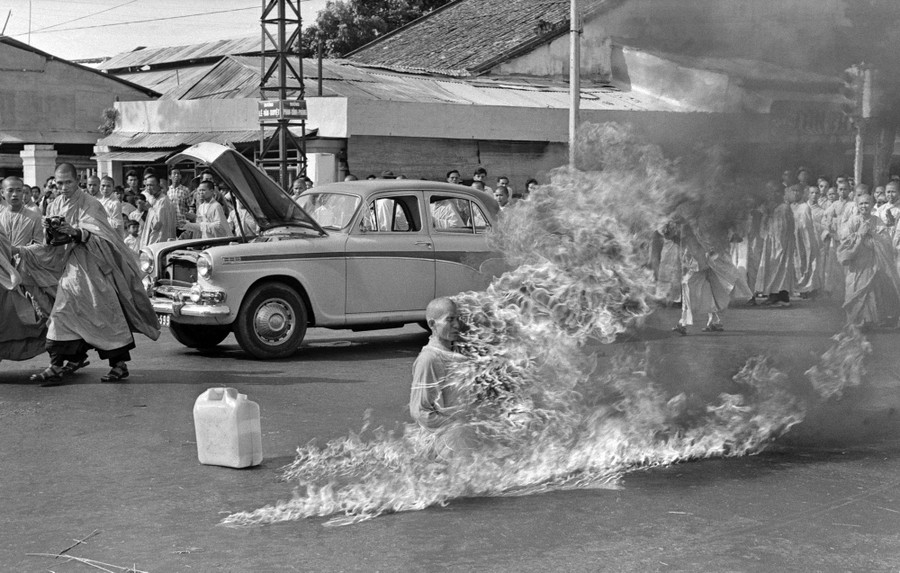

Thich Quang Duc, a Buddhist monk, burns himself to death on a Saigon street on June 11, 1963, to protest alleged persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government. President Ngo Dình Diem, part of the Catholic minority, had adopted policies that discriminated against Buddhists and gave high favor to Catholics. #

Flying low over the jungle, an A-1 Skyraider drops 500-pound bombs on a Viet Cong position below as smoke rises from a previous pass at the target, on December 26, 1964. #

Partially covered, a dying Viet Cong guerrilla raises his hands as South Vietnamese Marines search palm groves near Long Binh in the Mekong Delta, on February 27, 1964. The guerrilla died in a foxhole following a battle between a battalion of South Vietnamese Marines and a unit of Viet Cong. #

As U.S. "Eagle Flight" helicopters hover overhead, South Vietnamese troops wade through a rice paddy in Long An province during operations against Viet Cong guerrillas in the Mekong Delta, in December of 1964. The "Eagle Flight" choppers were loaded with Vietnamese airborne troops who were dropped in to support ground forces at the first sign of enemy contact. #

A father holds the body of his child as South Vietnamese Army Rangers look down from their armored vehicle on March 19, 1964. The child was killed as government forces pursued guerrillas into a village near the Cambodian border. #

Marines wade ashore with heavy equipment at first light at Red Beach near Da Nang in Saigon on April 10, 1965. #

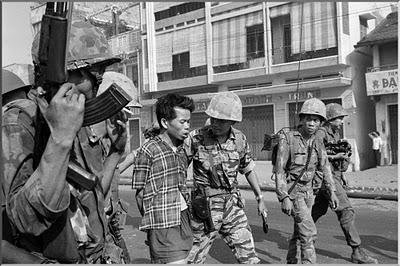

With the persuasion of a Viet Cong-made spear pressed against his throat, a captured Viet Cong guerrilla decided to talk to interrogators, telling them of a cache of Chinese grenades on March 28, 1965. He was captured with 13 other guerrillas and 17 suspects when two Vietnamese battalions overran a Viet Cong camp about 15 miles southwest of Da Nang air force base. #

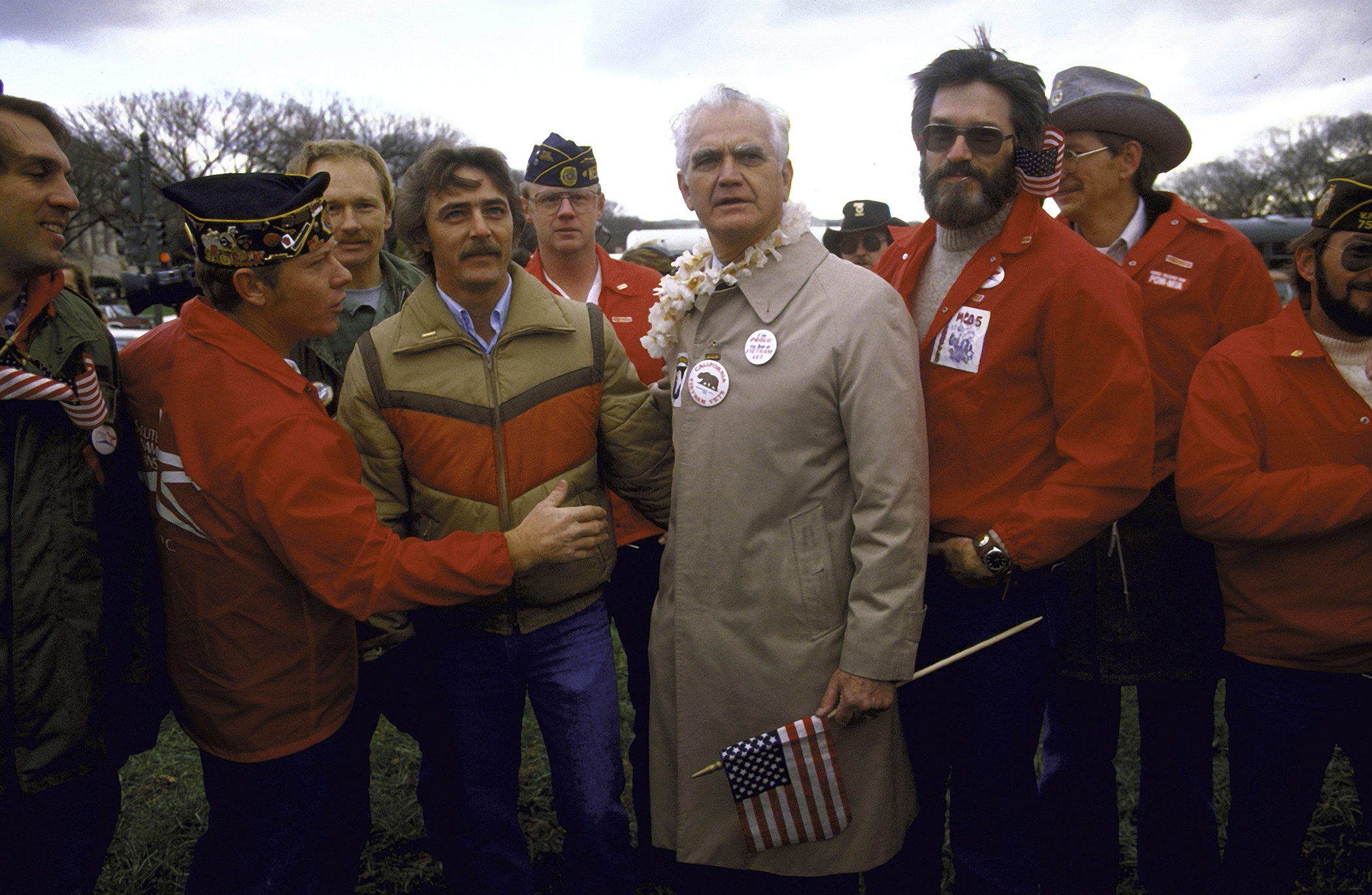

Thousands attend a rally on the grounds of the Washington Monument in Washington on April 17, 1965, to hear Ernest Gruening, a Democratic senator from Alaska, and other speakers discuss U.S. policy in Vietnam. The rally followed picketing of the White House by students demanding an end to Vietnam fighting. #

A nurse attempts to comfort a wounded U.S. Army soldier in a ward of the 8th army hospital at Nha Trang in South Vietnam on February 7, 1965. The soldier was one of more than 100 who were wounded during Viet Cong attacks on two U.S. military compounds at Pleiku, 240 miles north of Saigon. Seven Americans were killed in the attacks. #

Flag-draped coffins of eight American Servicemen killed in attacks on U.S. military installations in South Vietnam, on February 7, are placed in transport plane at Saigon, February 9, 1965, for return flight to the United States. Funeral services were held at the Saigon Airport with U.S. Ambassador Maxwell D. Taylor and Vietnamese officials attending. #

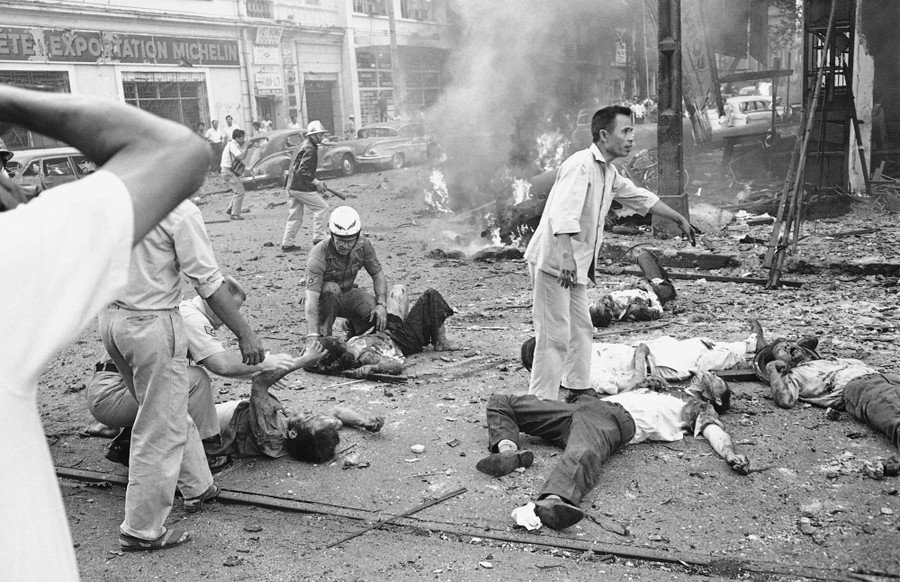

Injured Vietnamese receive aid as they lie on the street after a bomb explosion outside the U.S. embassy in Saigon, Vietnam, on March 30, 1965. Smoke rises from wreckage in background. At least two Americans and several Vietnamese were killed in the bombing. #

Four "Ranch Hand" C-123 aircraft spray liquid defoliant on a suspected Viet Cong position in South Vietnam in September of 1965. The four specially equipped planes covered a 1,000-foot-wide swath in each pass over the dense vegetation. #

A Vietnamese battalion commander, Captain Thach Quyen, left, interrogates a captured Viet Cong suspect on Tan Dinh Island, Mekong Delta, in 1965. #

A strategic air command B-52 bomber with externally mounted, 750-pound bombs heads toward its target about 56 miles northwest of Saigon near Tay Ninh on November 2, 1965. #

General William Westmoreland talks with troops of first battalion, 16th regiment of 2nd brigade of U.S. First Division at their positions near Bien Hoa in Vietnam, in 1965. #

Flares from planes light a field covered with the dead and wounded of the ambushed battalion of the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division in the Ia Drang Valley, Vietnam, on November 18, 1965, during a fierce battle that had been raging for days. Units of the division were battling to hold their lines against what was estimated to be a regiment of North Vietnamese soldiers. Bodies of the slain soldiers were carried to this clearing with their gear to await evacuation by helicopter. #

A Viet Cong fighter in Vietnam in an undated photo #

A U.S. Marine, newly arrived in South Vietnam on April 29, 1965, drips with perspiration while on patrol in search of Viet Cong guerrillas near Da Nang air base. American troops found 100-degree temperatures a tough part of the job. General Wallace M. Greene Jr., a Marine Corps commandant, after a visit to the area, authorized light short-sleeved uniforms as aid to troops’ comfort. #

In Berkeley-Oakland City, California, demonstrators march against the war in Vietnam in December of 1965. #

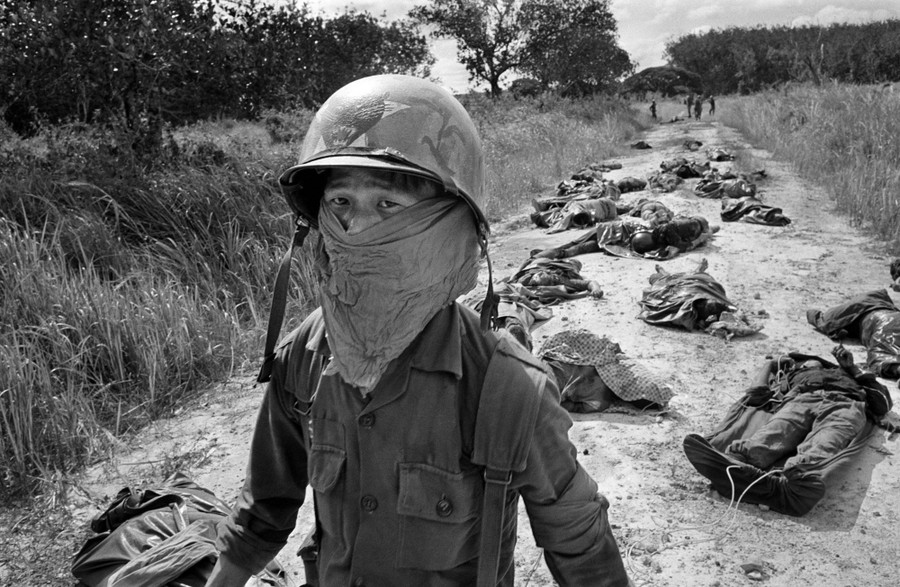

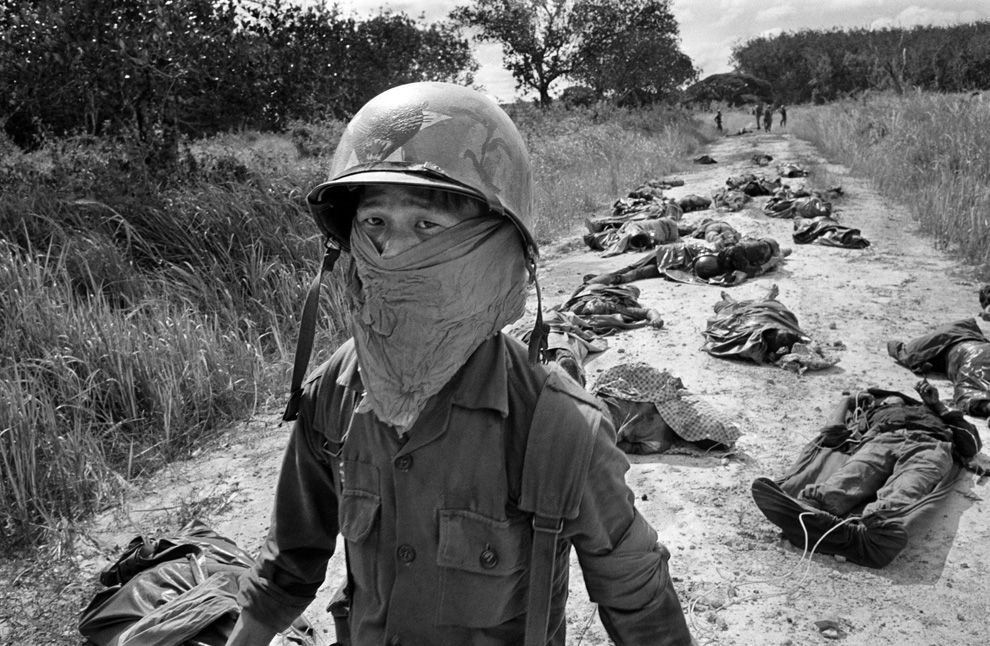

A Vietnamese litter bearer wears a face mask to keep out the smell as he passes the bodies of U.S. and Vietnamese soldiers killed in fighting against the Viet Cong at the Michelin rubber plantation, about 45 miles northeast of Saigon, on November 27, 1965. #

Pedestrians cross the destroyed Hue Bridge in Hue, Vietnam, in an undated photo. #

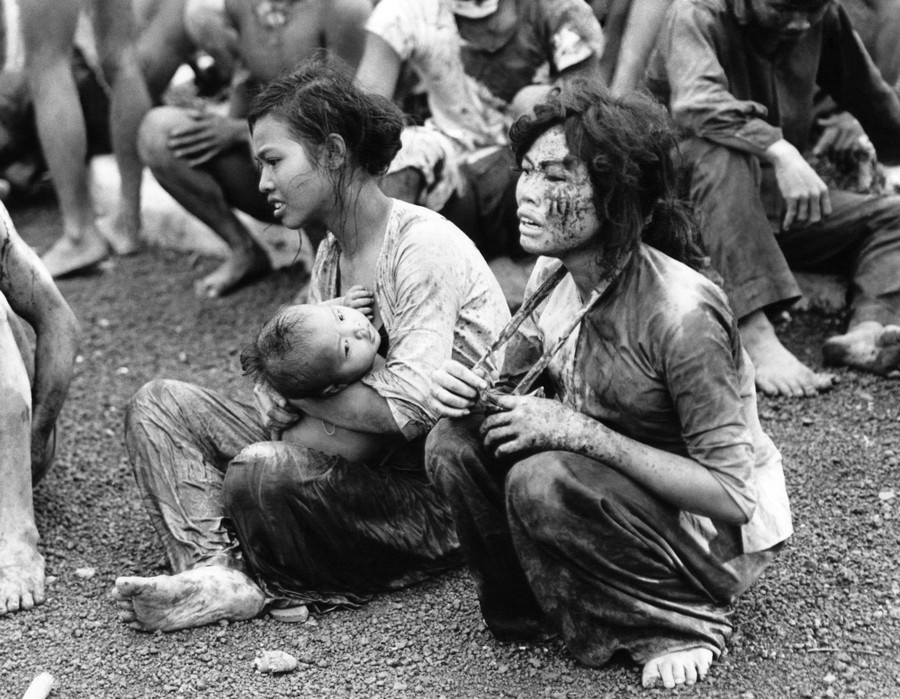

Wounded and shocked civilian survivors of Dong Xoai crawl out of a fort bunker on June 6, 1965, where they survived murderous ground fighting and air bombardments of the previous two days. #

A U.S. Air Force Douglas A-1E Skyraider drops a white phosphorus bomb on a Viet Cong position in South Vietnam in 1966. #

A Vietnamese girl, 23 years old, was captured by an Australian patrol 30 feet below ground at the end of a maze of tunnels some 10 miles west of the headquarters of the Australian task force (40 miles southeast of Saigon). The woman was crouched over a World War II radio set. About seven male Viet Cong took off when the Australians appeared—but the woman remained and appeared to be trying to conceal the radio set. She was taken back to the Australian headquarters where she told under sharp interrogation (which included a "waterprobe"; see her wet clothes after the interrogation) that she worked as a Viet Cong nurse in the village of Hoa Long and had been in the tunnel for 10 days. The Australians did not believe her because she seemed to lack any medical knowledge. They thought that she may have possibly been the leader of the political cell in Long Hoa. She was being led away after interrogation, clothes soaked from the "waterprobe" on October 29, 1966. #

Left: Pilot Leslie R. Leavoy in flight with other jets in the background above Vietnam in 1966. Right: Army nurse 2nd Lieutenant Roberta “Bertie” Steele in South Vietnam, on February 9, 1966. #

Women and children crouch in a muddy canal as they take cover from intense Viet Cong fire at Bao Trai, about 20 miles west of Saigon, on January 1, 1966. Paratroopers, background, of the U.S. 173rd Airborne Brigade escorted the South Vietnamese civilians through a series of firefights during the U.S. assault on a Viet Cong stronghold. #

A napalm strike erupts in a fireball near U.S. troops on patrol in South Vietnam in 1966. #

A Marine, top, wounded slightly when his face was creased by an enemy bullet, pours water into the mouth of a fellow Marine suffering from heat during Operation Hastings along the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam on July 21, 1966. #

Left: A Vietnamese child clings to his bound father who was rounded up as a suspected Viet Cong guerrilla during “Operation Eagle Claw” in the Bong Son area, 280 miles northeast of Saigon on February 17, 1966. The father was taken to an interrogation camp with other suspects rounded up by the U.S. 1st air cavalry division. Right: The body of an American paratrooper killed in action in the jungle near the Cambodian border is raised up to an evacuation helicopter in War Zone C, Vietnam, in 1966. #

The singing group the "Korean Kittens" appear on stage at Cu Chi, Vietnam, during the Bob Hope USO Christmas show, to entertain U.S. troops of the 25th Infantry Division. #

A grim-faced U.S. Marine fires his M60 machine gun, concealed behind logs and resting in a shallow hole, during the battle against North Vietnamese regulars for Hill 484, just south of the demilitarized zone, on October 10, 1966. After three weeks of bitter fighting, the 3rd battalion of the 4th Marines took the hill the week of October 2. #

Lieutenant Commander Donald D. Sheppard, of Coronado, California, aims a flaming arrow at a bamboo hut concealing a fortified Viet Cong bunker on the banks of the Bassac River, Vietnam, on December 8, 1967. #

A U.S. Marine CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter comes down in flames after being hit by enemy ground fire during Operation Hastings, just south of the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam, on July 15, 1966. The helicopter crashed and exploded on a hill, killing one crewman and 12 Marines. Three crewmen escaped with serious burns. #

A man brews tea while a U.S. Marine examines a pinup in Vietnam in September of 1967. #

A trooper of the U.S. 1st cavalry division aims a flamethrower at the mouth of cave in An Lao Valley in South Vietnam, on April 14, 1967, after the Viet Cong group hiding in it were warned to emerge. #

Sergeant Ronald Payne, 21, of Atlanta, Georgia, emerges from a Viet Cong tunnel holding his silencer-equipped revolver with which he fired at guerrillas fleeing ahead of him underground. Payne and others of the 196th light infantry brigade probed the massive tunnel in Hobo Woods, South Vietnam, on January 21, 1967, and found detailed maps and plans of the enemy. The infantrymen who explored the complex are known as “Tunnel Rats.” They were called out of the tunnels on January 21, and nauseating gas was pumped in. #

Military police, reinforced by Army troops, throw back anti-war demonstrators as they tried to storm a mall entrance doorway at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., on October 21, 1967. #

Rick Holmes of C company, 2nd battalion, 503rd infantry, 173rd airborne brigade, sits down on January 3, 1966, in Vietnam. #

U.S. Navy Douglas A-4E Skyhawks from Attack Squadrons VA-163 Saints and VA-164 Ghost Riders attack the Phuong Dinh railroad bypass bridge, 10 kilometers north of Thanh Hoe, North Vietnam, on September 10, 1967. Note the attacking Skyhawk in the lower right and one directly left of the explosions on the bridge. #

U.S. soldiers of the 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, look on a mass grave of enemy combatants after a day-long battle against the Viet Cong 272nd Regiment, about 60 miles northwest of Saigon, in March of 1967. U.S. military command reported 423 Communist forces dead, with American losses at 30 dead, 109 wounded, and three missing. #

U.S. troops of the 7th and 9th divisions wade through marshland during a joint operation on South Vietnam's Mekong Delta, in April of 1967. #

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to [email protected].

Most Recent

- July 19, 2024

Photos of the Week: Gruffalo Maze, Panama Swing, Luminous Mane

An orangutan rehabilitation center in Borneo, an iceberg-filled fjord in Greenland, scenes from the Republican National Convention, a fire festival in Japan, and much more

- July 17, 2024

A Century Ago, the Paris 1924 Summer Olympics

Images of the many events, athletes, and spectators at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris

- July 16, 2024

Two Years of Amazing Images From the James Webb Space Telescope

A collection of images from the James Webb Space Telescope’s second year in space

- July 12, 2024

Photos of the Week: Death Valley, Hill Town, Eleventh Night

A stegosaurus fossil up for auction in New York, a newborn pangolin at the Prague Zoo, a Volleyball on Water tournament in Slovenia, a lightsaber training session in Mexico City, and much more

Most Popular on The Atlantic

- Trump Versus the Coconut-Pilled

- Thank God for That

- A Candidate, Not a Cult Leader

- Joe Biden Made the Right Choice

- Trump Is Planning for a Landslide Win

- Biden’s Greatest Strengths Proved His Undoing

- It’s Official: The Supreme Court Ignores Its Own Precedent

- The Trump Campaign Has Peaked Too Soon

- The Kamala Harris Problem

- This Crew Is Totally Beatable

Educator Resources

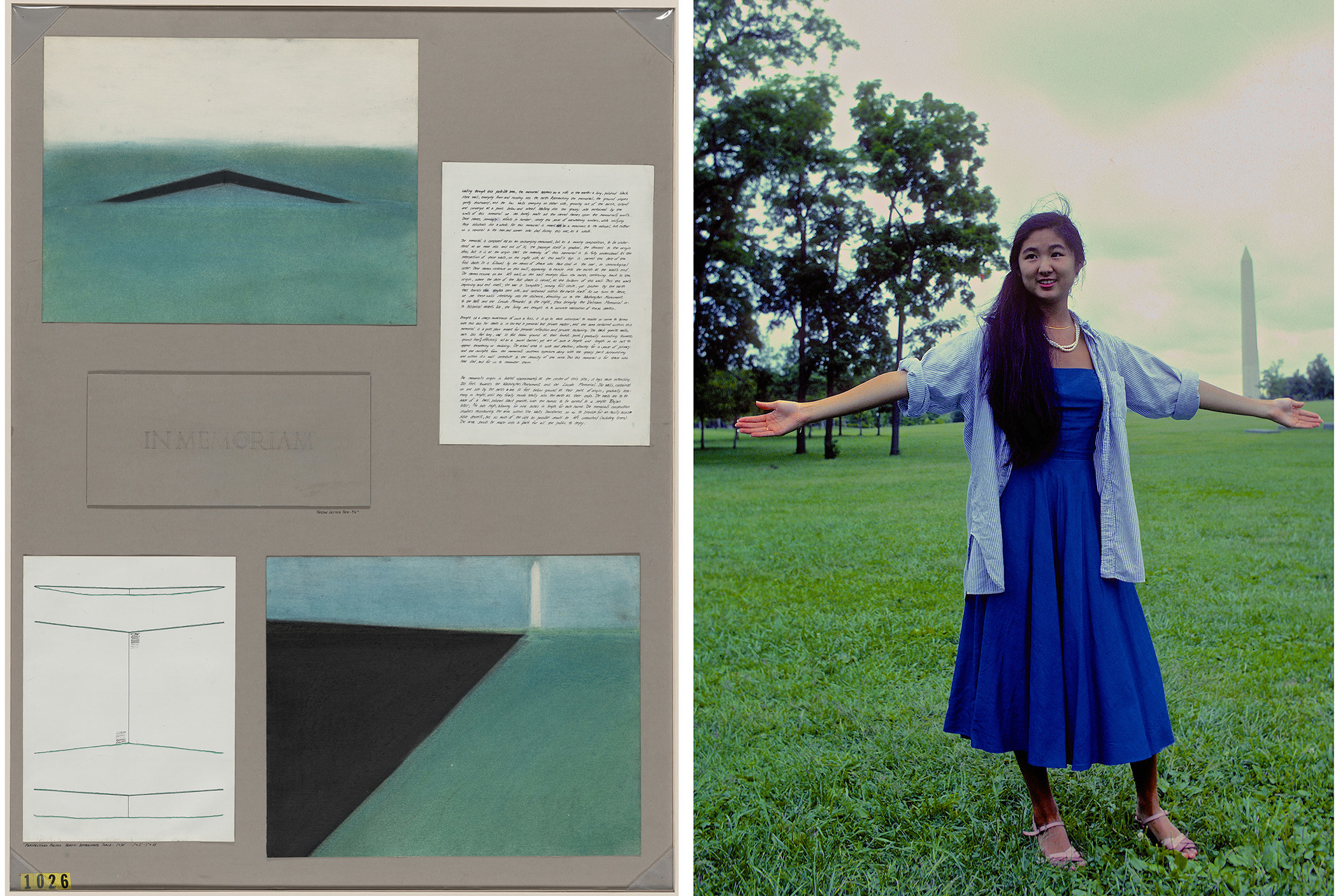

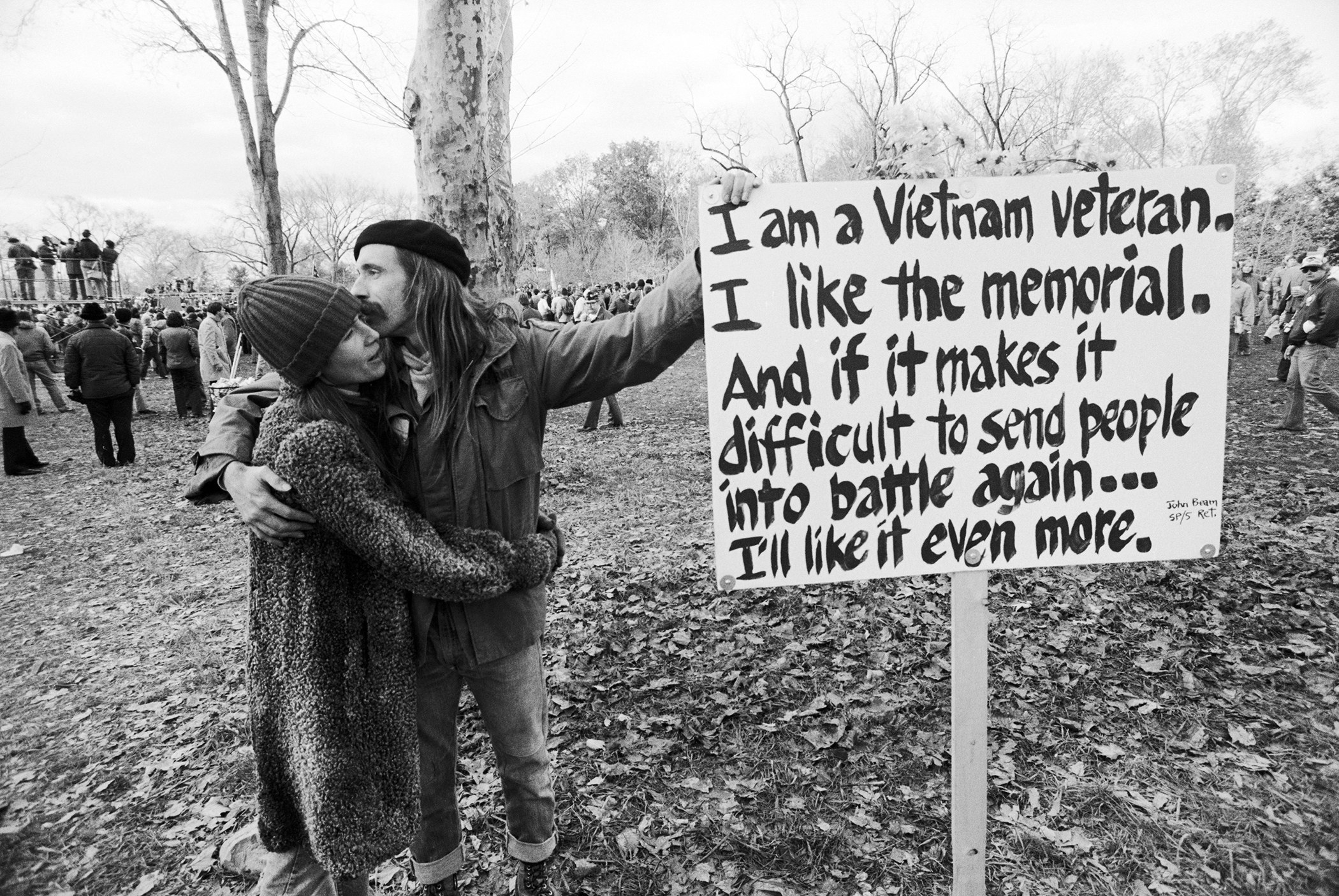

The War in Vietnam: A Story in Photographs

The war in Vietnam has been described as the first "living room war"—meaning combat was seen on TV screens and newspapers on a daily basis. Newspaper and television crews documented this war much more intensely than they did earlier conflicts. This willingness to allow documentation of the war extended to the military's own photographers—who captured thousands of images that covered every aspect of the conflict between 1962 and 1975.

Photographs

Links go to DocsTeach, the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

Marines on an M-48 Tank

Company A Gathers Around a Guitar

Operation "Oregon" Search and Destroy Mission

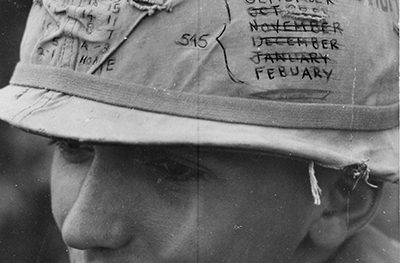

Keeping Track of Time Left on His Helmet

Soldiers Carry a Wounded Comrade Through a Swamp

A Marine Walks Through a Punji-staked Gully

A Marine Keeps a Battery Pack Dry Through Mud

A Marine Stands Watch in an Observation Tower

Home is Where You Dig It

Navy Seal Team One Moves Down the Bassac River

Red Cross Volunteer Playing Cards with Marines

Aboard the Hospital Ship USS Repose off South Vietnam

Intensive Care on the Hospital Ship USS Repose

Teaching Activities

The War in Vietnam - A Story in Photographs asks students to analyze the photographs from the Vietnam War shown above. After analysis, students will categorize the photos by topic and write captions in preparation for a photography exhibit about the war that "tells the story of the young men and women who fulfilled their duty to their country by serving in the war in Vietnam."

The Vietnam War Page on DocsTeach includes primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to the Vietnam War.

Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation

Vietnam inc.

Vietnam at war.

First published in 1971, Vietnam Inc. played a crucial part in changing public attitudes in the United States, turning the tide of opinion and ultimately helping to put an end to the Vietnam War. Philip Jones Griffiths’ classic account of the war was the outcome of years of intensive reporting and is one of the most detailed surveys of any conflict in twentieth-century history. Showing us the true horrors of the war as well as a study of Vietnamese rural life, the photographer and author creates a compelling argument against the de-humanizing power of the modern war machine and American imperialism. Rare and highly sought-after, Vietnam Inc. became one of the enduring classics of photojournalism.

His portraits of soldiers in action or, as often, at ease, have an insider’s conviction. The result is a work of extremes in which horror alternates with humanity: the soldiers on the point of raping a Vietnamese girl or the wounded civilian so swathed in bandages her identification is reduced to a label reading “VNC female”. Griffiths had an enduring sense of compassion for the Vietnamese people and their land, but also for the U.S troops, particularly those individuals who had been drafted. The real ‘bad guys’ are rarely the people with their boots on the ground.

Not since Goya has anyone portrayed war like Philip Jones Griffiths.

Henri cartier-bresson.

I decided to be the one to show what was really going on in Vietnam. Here was something of profound importance.

Philip jones griffiths.

Related work

Vietnam Leng Xuyen Bars

Vietnam Le Van Duyet’s tomb at Tet

Vietnam Flower Market at Tet

Buddhist Pagoda near Saigon, etc.

Publications.

Dark Odyssey

Vietnam Inc.

Agent Orange:

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Saigon. 1967

VIETNAM. Older soldiers who missed their families befriended dogs and children. The canines proved more congenial. More dogs than wives were taken back to the U.S. 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. 1970

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. MACV headquaters, Tan Son Nhut Airport. These are MACV (MIlitary Assistance Command, Vietnam) personnel who were lectured monthly on the progress of pacification. 1970

VIETNAM. This operation by the 1st Cavalry Division to cut the Ho Chi Minh trail failed like all the others but the U.S. military were shaken to find such sophisticate weapons stockpiled in the valley. Officers still talked of winning the war, of seeing "the light at the end of the tunnel." As it happened there was a light, that of a fast-approaching express train. 1968

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. The vietnamese village. Rise is traditionally threshed by walking a buffalo over it. This costs nothing and is a pleasant way to spend an evening.1970

VIETNAM. The parents of young children were rarely present in the village of Vietnam. Americans often wondered where all the children came from. The fathers were often away fighting for one side or the other, and the mothers had jobs servicing the G.I.'s. Whether officially called cleaning, laundering, shoe-shining, or even car-washing, "servicing" usually meant prostitution. 1970

VIETNAM. Delta and My Tho. 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Ben Tre. 1970

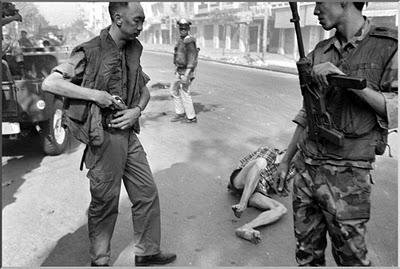

VIETNAM. Quang Ngai. This guerrilla fighter had just thrown a grenade, killing one member of the platoon and wounded two others. In the resulting fracas, he too was killed. The incident occurred in what had once been a quiet hamlet in central Vietnam, probably in the very field in front of his home where he'd spent his youth tilling the soil. 1967

VIETNAM. A CIA-organized demonstration of "spontaneous" anger against those favouring a negotiated settlement of the war. 1967

VIETNAM. Mortuary Vehicle. 1967

VIETNAM. 1967.

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Danang. 1967

VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. 1968

CAMBODIA. Car salesmen used to follow soldiers into the field to make their sales ("so the boys will have a real reason for wanting to get home in one piece"). As the fighting intensified, they found it safer to send catalogs. 1970

CAMBODIA. Prisoners of war were afforded very different treatment by each side. Americans were treated reasonably (the ranting of the MIA movement in America aside), whereas captured Vietcong were tortured, raped, and killed. Some ended in the tiger-cages of the U.S. administered Con Son prison, where conditions would have staggered a Spanish Inquisitor. 1970

CAMBODIA. His lack of equipment is a constant source of wonder to the GI's. Surrounded, this Vietcong "defected", in the best Maoist tradition. Caught in the wires of an "automatic ambush", he produced a Chieu Hoi (safe conduct) pass to classify himself as a "rallier" to the GVN side. 1970

VIETNAM. Quang Ngai. Peasants. 1967

VIETNAM. US 9th Division troops on patrol in the Mekong Delta during a conversation with a peasant boy. 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Ba Cho. 1971

VIETNAM. 1968. Innocent peasants take the brunt of the U.S. military drive.

VIETNAM DU SUD. Phu Quoc. 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Operation "Cedar Falls". 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Hospital. 1968

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Song Tra. 1967

VIETNAM. During the Vietnamese New Year celebrations of the Tet, the city of Hue an ancient Mandarin walled city which stood on the banks of the perfumed river and near to the demilitarised zone, a force of 5000 Vietcong and NVA (North Vietnamese Army) regulars took siege of the citadel. The American sent in the Fifth Marine Commando force to dislodge them. 1968

VIETNAM. Hue. US Marines inside the Citadel rescue the body of a dead Marine during the Tet Offensive. 1968

The battle for the Cities. U.S. Marines. 1968.

VIETNAM. Hue. Refugees flee across a damaged bridge. Marines intended to carry their counterattack from the southern side, right into the citadel of the city. Despite many guards, the Vietcong were able to swim underwater and blow up the bridge, using skin-diving equipment from the Marines.

VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. Refugees under fire. Confused urban warfare was such that Americans were shooting their staunchest supporters. 1968

VIETNAM. Called a "little tiger" for killing two "Vietcong women cadre" - his mother and teacher, it was rumored. 1968

VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. U.S. policy in Vietnam was based on the premise that peasants driven into the towns and cities by the carpet-bombing of the countryside would be safe. Furthermore, removed from their traditional value system they could be prepared for imposition of consumerism. This "restructuring" of society suffered a setback when, in 1968, death rained down on the urban enclaves. 1968

VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. Refugee from US Bombing. 1968

VIETNAM. The American policy of Annihilating as many Vietnamese as possible while claiming to be saving them from the "horrors" of Communism could be confirmed by visiting any hospital. 1967

VIETNAM. Quang Ngai. 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Quin Hon. U.S. Soldiers with a group of captured Vietcong suspects. 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Quin Hon. 1967

VIETNAM. Quang Ngai. This was a village a few miles from My Lai. It was a routine operation - troops were on a typical " search and destroy" mission. After finding and killing men in hiding, the women and children were rounded up. All bunkers where people could take shelter were then destroyed. Finally the troops withdrew and called in an artillery strike of the defenseless inhabitants. 1967

VIETNAM. Refugee camp. In this camp, the "Psy-Ops" officer discovered he'd forgotten to order "indigenous reading material" for the inmates, so he dished out Playboy magazine instead. 1967

VIETNAM. The battle for Saigon. The problem with "close" artilery support was that it was often too close. on this occasion shells called in by these troops had landed among them. The officer's desperate message to halt the bombardment were not recieved; he had taken up refuge inside an armoured personnel carrier where his frenzied transmissions could not penetrate the metal hull. 1968

VIETNAM. This boy was killed by U.S. helicopter gunfire while on his way to church - a Catholic church - whose members were avid supporters of the government, who were in turn pro-American. The result was a disillusioned urban population, reluctant to believe in or support their discredited leaders. 1968

VIETNAM. In Quang Ngai Province everything that moved was a target. It had been strongly Communist for thirty years and in practice U.S. policy was genocide. Each morning, a few lucky survivors of the previous night's carnage made it to the province hospital. The newly developed antipersonnel weapons caused a problem - their plastic darts did not show up on X-rays. 1967

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Danang. A U.S. Marine demonstrates how to bathe a child to bored Vietnamese mothers. 1967

VIETNAM. Nha Be. In a society where women are traditionally revered for their poise and purity, the wartime conditions effectively dehumanized them. This girl was dancing for a group of U.S. Navy personnel on a makeshift stage (the officer's reviewing stand) when she was joined by two unwelcomed spectators. 1970

VIETNAM. Long Binh. Discarded equipment collects in stockpiles as the ground war draws to a close. 1970

VIETNAM. Radar Control at Tan Son Nhut. 1970

VIETNAM. Can Tho. 1970

VIETNAM. Leng Xuyen Bars. 1970

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Saigon. 1970

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Phu Me. As a Young child, this boy had been in the arms of his fleeing mother as she was hit by machine-gun fire from a helicopter outside their home. He survived, but went insane and spent his life chained up to his hospital bed. When helicopters passed overhead he went berserk trying to shut out their sound. 1970

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Cam Ranh. 1970

As part of the techno-war concept, the idea of an automated battlefield was widely touted. Aircraft carriers - floating airstrips, secure from the attack - would respond to requests for bombing. The pilots never saw the faces of those they killed and maimed. It was considered important to protect men from sights that could produce emotional reactions.

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Quang Ngai. This group was not recovering from surgery so, to free up scarce beds, they transferred to an outbuilding to die. The determination was made by the hospital's solitary Spanish surgeon. There was no way he could operate on everyone; he explained with tears in his eyes, "Every morning I have to play God - deciding who will die and who I will give a chance to live." 1967

VIETNAM. Hue. US Marines inside the citadel in Hue during the Tet offensive. 1968

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. The levelled village of Ben Tre in the delta after the Tet offensive. 1968

VIETNAM. South Vietnam. Quang Ngai. 1967

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

7 Iconic Photos From the Vietnam War Era

By: Dave Roos

Updated: May 3, 2024 | Original: June 8, 2022

Many of the reporters and photographers who covered the conflict in Vietnam came from a new generation of journalists. Coverage of earlier wars was heavily influenced by the government, says Susan Moeller, a journalism professor and author of Shooting War: Photography and the American Experience of Combat , but in Vietnam, the journalistic mission was different.

“There was no longer that expectation that they should speak the government’s line,” says Moeller. “In Vietnam, journalists saw their remit as calling into question some of the statements and assertions of the White House and Pentagon.”

Stark photographs of dying soldiers and wounded civilians provided a striking counter-narrative to official reports that America was winning the war in Vietnam. As the conflict dragged on and the death toll of American soldiers mounted, these iconic images added fuel to the growing anti-war movement and shook the halls of power.

1. Buddhist Monk Self-Immolates

On June 11, 1963, a Buddhist monk named Thich Quang Duc sat calmly in a busy intersection near Siagon’s Presidential Palace as a fellow monk doused him with gasoline. After saying a short prayer, Thich Quang Duc lit a match and dropped it into his lap, instantly engulfing his body in flames. Images of the monk’s stoic self-immolation, taken by AP journalist Malcolm Browne , sent shockwaves around the world.

Thich Quang Duc gave his life in protest of the brutal, anti-Buddhist policies of the South Vietnamese president, Ngo Dinh Diem, a staunch Catholic. Browne’s unforgettable photographs called into question America’s growing support for the South Vietnam regime. President John F. Kennedy is reported to have said, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as that one.” But it didn’t change Kennedy’s mind on America’s position on Vietnam.

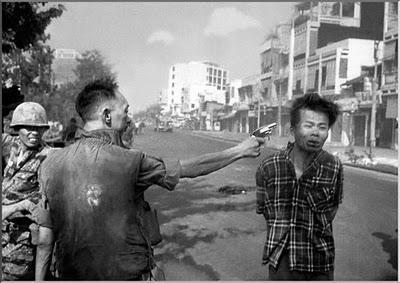

2. Shocking Execution

More than 50 years later, this image still has the power to startle and sicken. It was published on the front page of newspapers like The New York Times in February 1968, days into the Tet Offensive, massive coordinated attacks by the North Vietnamese government. In the photo, a South Vietnamese police chief calmly executes a Vietcong fighter in the streets of Saigon. The image, which won a Pulitzer Prize for photographer Eddie Adams, caused many Americans to openly question the morality of the war.

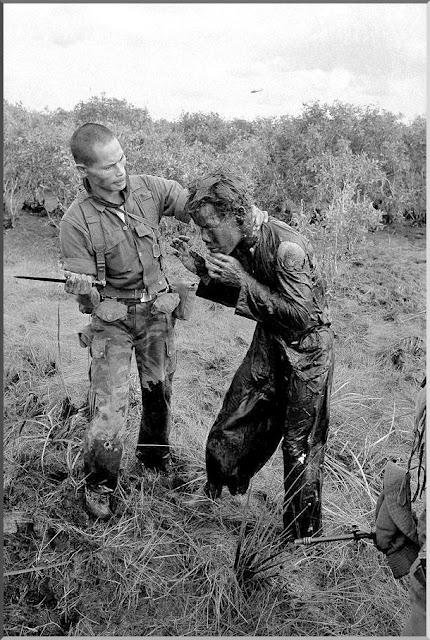

3. Deadliest Year for American Soldiers in Vietnam

1968 was the deadliest year for American soldiers in Vietnam, and this image, captured by freelance photographer Art Greenspon , summed up the tremendous cost being paid by young men fighting in what increasingly felt like a futile war.

The sense of brotherhood in the photo is palpable, as is the sense of anguish and desperation. Nearly half of the company had been killed in a firefight and the survivors waited two days for a medevac helicopter to arrive. The First Sergeant raised his arms in the air to signal the chopper, but he might as well have been lifting them in prayer.

Greenspon’s indelible image landed on the front page of The New York Times and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

4. LBJ and Family Watching Protests

Yoichi Okamoto was the very first chief White House photographer, hired by President Lyndon Johnson . Okamoto was given unfettered access to the president, as shown in this incredibly intimate moment captured inside the Johnsons’ bedroom at their family ranch in Stonewall, Texas.

The president and First Lady Ladybird Johnson are watching coverage of the anti-war protests outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

5. Kent State Shootings

On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon authorized the American invasion of Cambodia , a neutral country bordering Vietnam. Americans were deeply divided over the war, and Nixon’s decision sparked angry protests on college campuses, including Kent State in Ohio, where protestors burned down the ROTC building.

On May 4, 1970, National Guard troops ordered the Kent State protestors to disperse, but the crowd of roughly 3,000—composed of students and outside protesters—refused, with some throwing rocks at the Guardsmen. No one expected what happened next. The National Guard troops opened fire, sending a 13-second volley of bullets into the mass of protesters.

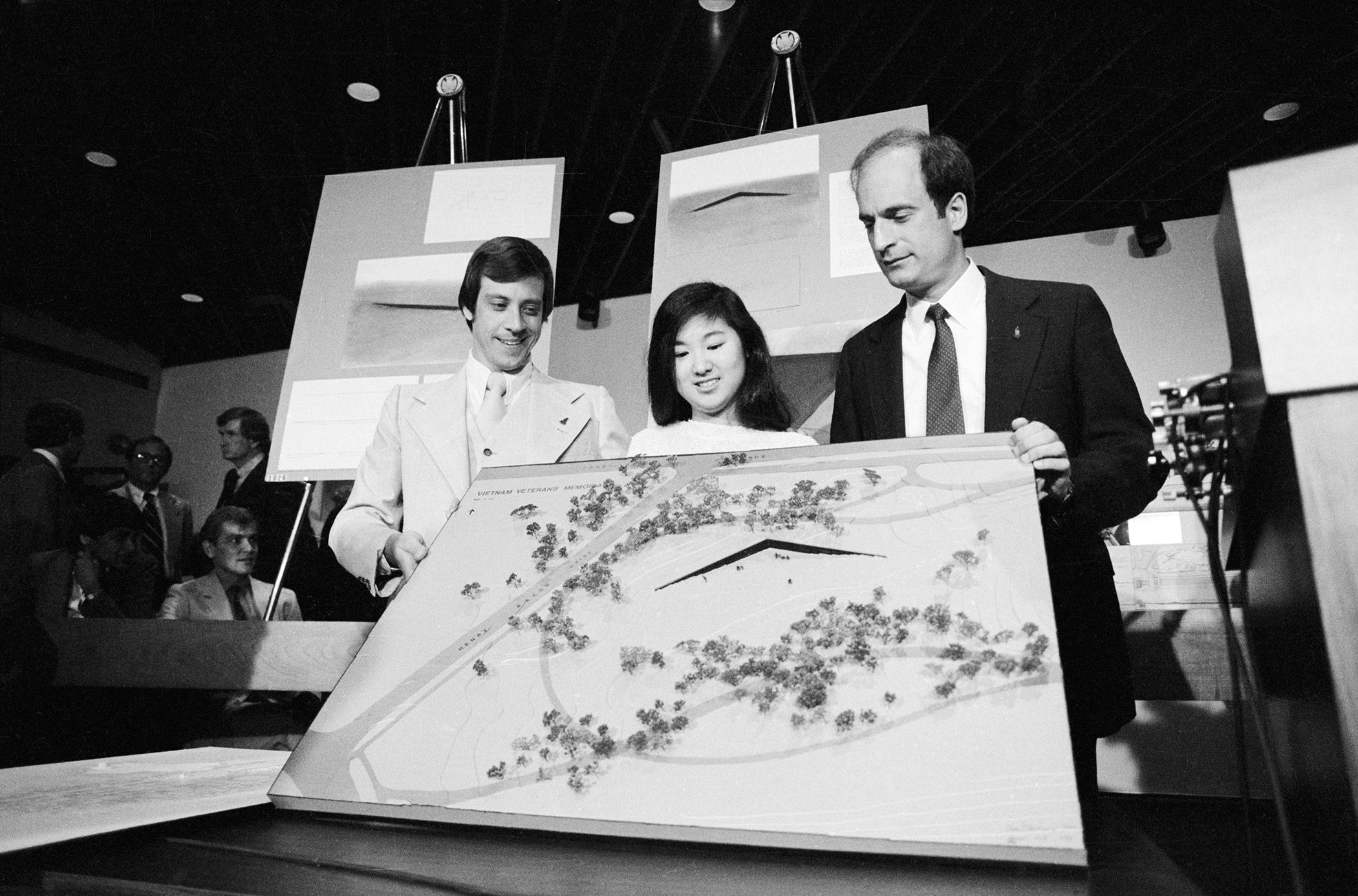

Four Kent State students were killed that day and nine more were injured. Student photographer John Filo won a Pulitzer Prize for his gripping photo of 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio crying out next to the fallen body of Jeffrey Miller. The shootings at Kent State cast a pall over the Nixon presidency and brought the violence of the Vietnam War home in a whole new way.

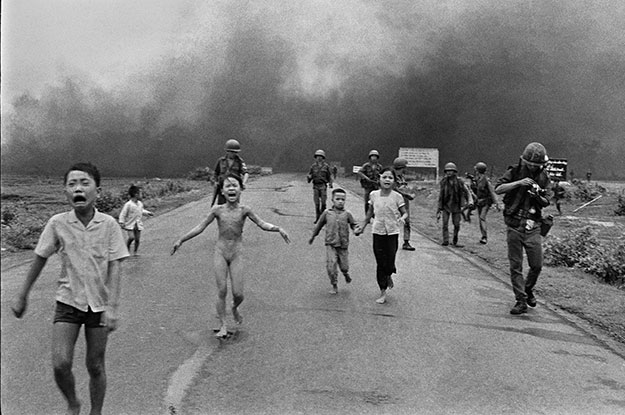

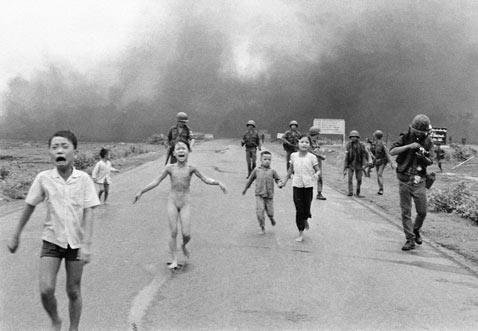

6. 'The Terror of War'

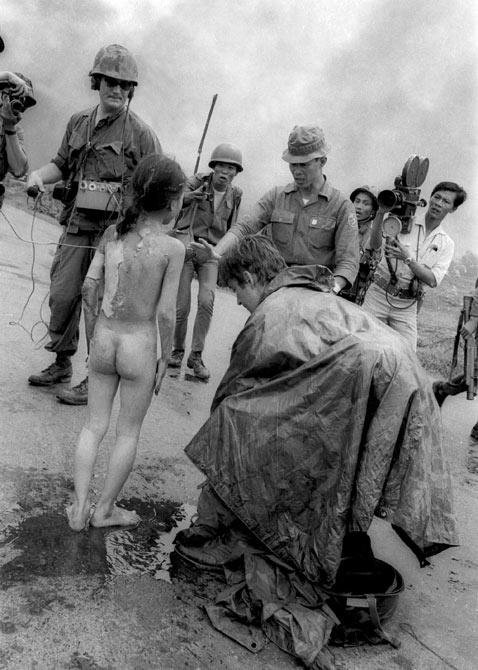

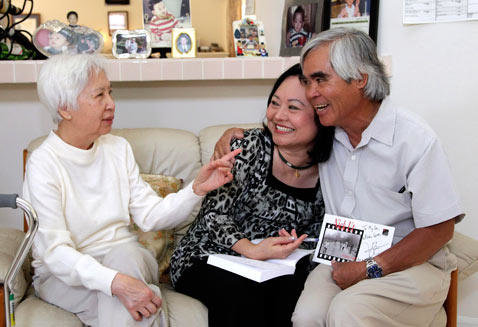

The title of this photo says it all, “The Terror of War.” Vietnamese-American photographer Nick Ut won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1972 image of innocent children fleeing an accidental napalm attack on their village. Front and center is nine-year-old Kim Phuc, naked and badly burned by the American chemical weapon. When Ut realized the extent of her injuries, he and others came to Phuc’s aid. They’re still close friends.

"That picture will always serve as a reminder of the unspeakable evil of which humanity is capable," Phuc wrote in a guest essay published in the New York Times 50 years later on June 6, 2022. "Still, I believe that peace, love, hope and forgiveness will always be more powerful than any kind of weapon."

7. Airlift Operation After Fall of Saigon

On April 29, 1975, the fall of Saigon was imminent. Panic engulfed the streets of the South Vietnamese capital as North Vietnamese troops encircled the city. American diplomats and journalists were ordered to evacuate Saigon immediately, and scores of South Vietnamese citizens crowded outside the U.S. Embassy in hopes of boarding one of the Marine helicopters carrying people to safety.

This iconic image, taken by Dutch journalist Hubert van Es, perfectly captured the desperate and ignominious withdrawal from Saigon, but the helicopter wasn’t perched atop the U.S. Embassy as most people think. It was an apartment building housing American CIA officers. Only about a dozen of the crush of people on the rooftop were able to squeeze on the helicopter before it lifted off, never to return.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Narrative Strategies of the Vietnam War Coverage by German War Photographer Horst Faas from 1964 - 1971 – An analysis of four selected pictures by Anton J. Hansen

It’s the early morning of June 5 th , 1972 and Huỳnh Công Út, professionally known as Nick Ut, joins a team of journalists, photographers and soldiers towards Trang Bang. The village is located about 25 miles northwest of Saigon and heavy fighting has been going on for a couple of days. Nick, only 21 years old at this time, is armed. Not with a rifle, but with a tool that plays an important role in ending this war. A war which has killed more than two million Vietnamese civilians, more than one million Vietnamese soldiers and more than 58 000 US-American soldiers (Lewy, 1980; Spector, 2020). A war, which has left millions traumatized. Since Vietnam gained its independence in 1946, it constantly had martial conflicts with its former colonizers France, and the United States of America which tried to set up a deeply corrupted regime in South Vietnam (Bradley, 2009, p.118). When Ho Chi Minh, the leading politician of North Vietnam who dreamed of reuniting his mother country, started to increase the political and martial pressure on South Vietnam, the United States of America started to send more and more military personnel to South Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh, who was looking for support by the United States, shortly after Vietnams independence in 1946, was rejected by the USA due to its diplomatic ties with former colonizing power France (Lawrence, 2008, p.27). Therefore, Ho Chi Minh switched sides and found the Soviet Union and China as allies. Fearing that Vietnam would reunite and become a Communistic country, which would pressure American alleys in South East Asia, including Cambodia, Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand, the United States increased their military engagement in South Vietnam in 1964 (Bradley, 2009, p.109). In 1968 already, more than 500.000 US-American soldiers fought one of the bloodiest, most brutal wars of the 20st century. Furthermore, three times the number of bombs were dropped by the USA until 1975 on that tiny South East Asian nation than were dropped by all parties in World War II combined (Bradley, 2009, p.115). The atrocities committed to Vietnamese civilians by US-American soldiers are widely compared to the holocaust committed by Nazi Germany (Lawrence, 2008, p. 159).

For Nick Ut, this morning is just as many mornings in the war. A local village has been bombed with napalm bombs, there are dead bodies, fleeing villagers and a lot of pain and misery. Nick, holding his camera ready, walks on a highway with his colleagues and suddenly, he sees them.

A group of children, horribly burned by napalm, running crying towards him while US army soldiers and journalists walk quietly besides them, minding their own business. Nick lifts his camera, his powerful tool, and takes photos, one after the other, before he runs towards the children to carry out first aid. The photo that he took of the fleeing children this morning will win the Pulitzer price and plays an important role in the anti-war movement. It narrates the cruelties that are committed by the US-troops to Vietnamese citizens and a good example of the strong appeal that imagery has on the minds of people.

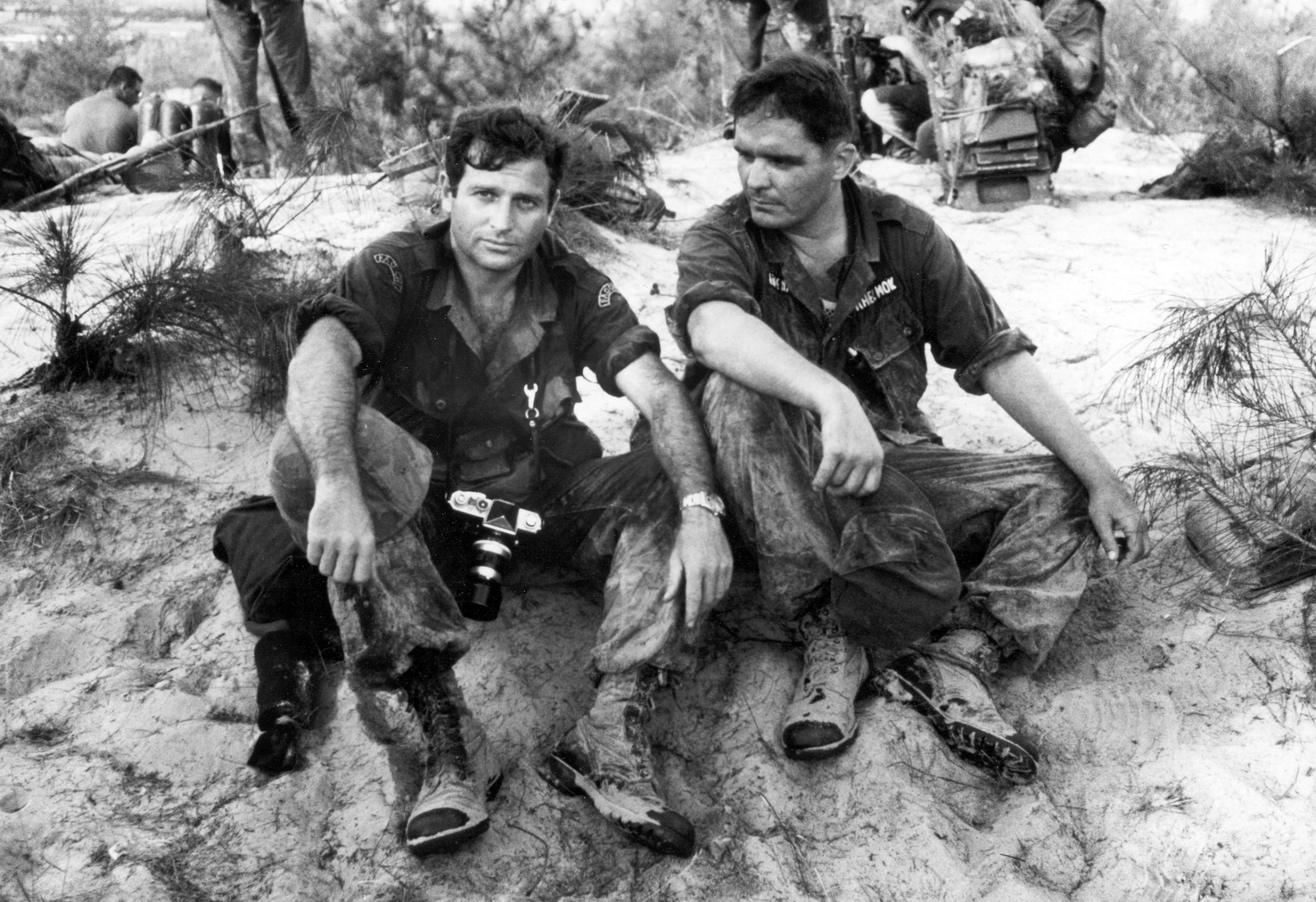

But the photo almost didn’t get published. Horst Faas, a German journalist, stationed in Saigon at the time, mobilized all his contacts to get the photo out of Vietnam and published. Associated Press was very critical of publishing a photo of a naked girl, but Faas directly realized the strong effect that publishing such a photo would have on public opinion worldwide. He knew, that this photo could have major contributions of ending this war. Horst Faas, working for Associated Press in Saigon, was also Nick Ut’s mentor and encouraged him to document the war in Vietnam for Associated Press. Horst Faas lend Nick and other young Vietnamese photography talents camera equipment and helped tremendously to get their work published. Apart from his role as recruiting young talents, Horst Faas also photographed and his photos are just as famous as Nick Ut’s “Accidental Napalm” is. The photos by Horst Faas are considered some of the best photos that were shot during the Vietnam war. Considering his role as a supporter for young Vietnamese talents and Faas’ journalistic impact by taking and publishing world-class photos of the war, one can say that Horst Faas was a central figure in shaping the photographic narrative that was told about the Vietnam war by media worldwide. Therefore, the question arises:

What are the uses of narrative in the photographic work of Horst Faas’ documentation of the Vietnam war?

To answer this question, I have selected four iconic photos, taken by Horst Faas between 1964 and 1971. Narrative refers to the succession of events, real of fictitious, that are the subjects of the discourse and has temporality (Casadei, 2015, p.30). But “photographic image stops, holds, fixes, immobilizes, highlights and separates duration, capturing a single moment of it” (Dubois, 1993, p.161). As “the flow, the race, the time has no validity in photography’s point of view”, photography is a figure without duration (Dubois, 1993, p.163). Never the less, we, the viewers of images constructs the temporality of images, by putting them into a context, into a historical frame through which we interpret them and their narratives (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, p.30). Consequently, the photojournalistic narrative says something about who looks at the picture

It is widely argued which impact the media had on the outcome of the Second Indo-China war, also known as the Vietnam war (Bradley, 2009; Griffin, 2010; Lewy, 1980). Horst Faas himself once said in an interview in 1997: “I don’t think we influenced the war at any time […] I don’t think we helped to win it or helped to lose it. We didn’t work on the outcome of the war.” However, he said that documenting a war is better than not documenting a war (Vitello, 2012). The control of narratives is key in establishing power relations and legitimizing the power of an authority. Controlling the mediazation of reality and the stories that are told about reality is part of it (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, p.16). Governments and political or economic interests work conscientiously to control, channel, limit, or delay image production and circulation that influences opposing narratives of war (Griffin, 2010, p.8).

Picture 1 – War is Hell

In the example of the Vietnam war, journalists challenged the narrative that was communicated by the US-army of brave man that defend the free world order in Asia (Griffin, 2010). This photo, taken on June 18, 1965 by Horst Faas challenges this narrative. The soldier, maybe 18-22 years old, is looking with a light smile into the camera. On a band around his helmet, it is written war is hell . Images that are communicated without the context, out of their historical, empirical linkage with agents, interests, media, circumstances, times and spaces, etc., stand for nothing, like a jellyfish taken out of the ocean or a snowflake taken from the air before it lands on the ground (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, 2011, p.30). When understanding the narrative of images, it is crucially important

to be familiar with the context of them. This photo portrays the feelings of thousands of US-American soldiers and the situation they found themselves in. Many were just fresh out of high school and have never been to a foreign country, let alone another US-state, before. Completely opposing the narrative of brave, experienced fighters, this photo shows the misery of a young man in hell . Seen in the context of young men that fight a war which can’t be won, the social establishment of the photograph is a cultural icon, a narrative maker of collective memory (Griffin, 2010, p.8). In addition to that, the narrative of the photo amplified the American sympathy with US army soldiers who seemed caught in a war for which national commitment was faltering (Oliver, 2006). American Television, which communicates a narrative through its implemented temporality, can be seen as a stream of under selected images, each of which cancels its predecessor. Photographs like this one on the contrary, are a “privileged moment”, turned into a slim object that one can keep and look at again (Sontag, 2010).

Picture 2 – Women and children crouch in muddy water

According to Oliver (2006), the American public had greater sympathy with US army soldiers than with Vietnamese civilians, even though pictures such as the one below was published. Horst Faas took this photo on January 1 st , 1966, when the GI-unit, that he joined for a patrol was attacked by North Vietnamese forces. The photo’s main character are the woman and the girl in the front, they are in focus, hiding in the muddy water. Behind them, is another woman and her baby, and even further behind are soldiers. The narrative of the photo shows the suffering of Vietnamese civilians, who have worried faces. They are brought to the center of the image, as if the photographer wanted to show the victims of the war as being the Vietnamese civilians. In contrast to them are the soldiers in the background who are unfocused and who’s faces aren’t visible, hidden by grass. The framing of the image deliberately excludes the American soldiers and includes the suffering of the Vietnamese villagers. Images as such offer viscerally exciting and voyeuristic glimpses into theaters of violence that, for most viewers, are alien to everyday experience (Taylor, 1998). Images are alternative strategies for the competition over the distribution of values in society and independent war photography challenges the narratives that are communicated by dominant powers (Butler, 2009). This dynamic of images is quite independently of the nature of the political regime in which images are taken and shared (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, 2011, p. 33). But even in democratic countries, such as the USA, reporters and photographers who attempted to publish pictures of victimized Vietnamese civilians in the late 1960s and 1970s met resistance from the mainstream US media and were even blacklisted or banned (Griffin, 2010).

Picture 3 – Father holding dead child

When accompanying American and South Vietnamese soldiers, Horst Faas often documented atrocities that were committed to civilians during the war. In the photo below, taken on March 19, 1964, a father holds his dead child, which was killed when South Vietnamese government forces pursued gorillas into a village near the Cambodian border. The structure of the photo communicates the narrative of a helpless victim against an overpowered enemy. Soldiers, sitting on a heavily armed vehicle are looking down on the father. They are above the cruelty, they are safe. The meaning of the photo relates to the general patterns it reveals about what war is. But the meaning is not simply located in the photo, it is produced by the observer and his or her assumptions, worldviews and prior narratives (Mayer, 2014, p.10). An extreme passion is captured in the photo that takes urgent claims on the viewer’s attention (Brothers, 1997). The narrative of the South Vietnamese troops, which were supported by the USA, as the overpowering force that kills children creates an alternative dimension of the political. The interpersonal and the intersubjective quickly turns into a matter directly affecting the competition for the distribution of values in society (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, 2011, p. 33). Those values might be human rights or democracy, for US-American viewers, and the space of uncertainty that the narrative of such a photo creates, invites for a reconsideration of the Vietnam war and its political aims. The angle from which the photo is taken and how it is framed, contribute greatly to this interpretation, as the military vehicle is visible as this big, overwhelming mass, against which the father and his dead son appear small and helpless.

Picture 4 – Dead Bodies

As the Vietnam war went on, more and more people were killed and the public opinion in the United States changed, opposing the war and American involvement in it. A reason for this was the rising number of American soldiers that were killed in the war and the media presentation of those losses (Griffin, 2010). Horst Faas documented this process with photos as the one below which was taken on November 27, 1965. Dead bodies are laying near a rubber plantation in South Vietnam before they are transported to be properly buried. In the front stands a South Vietnamese soldier, who looks in the camera and has his face covered against the rotting smell. The viewer is forced into a situation in which interpretation of the photo’s narrative is necessary but at the same time arbitrary and therefore ambiguous (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, p. 30). From an American perspective, the narrative of the photo describes the hopelessness of the war. The view of the man in the front is in despair, while dead bodies cover the dirt road behind him.

Horst Faas’ work encompasses many more than those photos, for which he won the Pulitzer Price twice. The communicated narratives tell stories about the people of the war. About suffering civilians, about young Americans killing and dying in a war initiated by white, old men, such as Richard Nixon or Lindon B. Johnson and about the cruelties of war. But the willingness to accept the premises of Faas‘ communicated narratives depends on the viewers of his images to evaluate the truth of narrative in terms of its precise correspondence with the real world. To grasp those narratives, viewers need to open their minds up and let go of a photo’s conformity with their general conceptions about the way the world works (Mayer, 2014, p.10). Photographs act on us and the analyzed photos communicate the suffering of individuals in war in such a way that viewers were prompted, and are still, to alter their political assessment of war (Butler, 2009, p.68). Even though, it is argued whether war photographs communicate a narrative, they definitely capture atrocities around which viewers construct narratives (Butler, 2009; Casadei, 2015; Dubois, 1993). Faas’ photos are known around the whole world and shape the memory of millions of people by documenting and telling the war in Vietnam.

Bradley, M. (2009). Vietnam at war . Oxford University Press.

Brothers, C. (1997). War and Photography: A Cultural History . London: Routledge.

Butler, J. (2009). Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?. London: Verso.

Casadei, E. B. (2015). Can still images tell stories? Symptom and temporality in photojournalism narrative theory. Brazilian Journalism Research , 11 (1), 28-43.doi:10.25200/bjr.v11n1.2015.804

Dubois, P. (1993). O ato fotográfico e outros ensaios. Campinas: Papirus.

Griffin, M. (2010). Media images of war. Media, War & Conflict, 3(1), 7–41. doi:10.1177/1750635210356813

Lawrence, M. A. (2008). The Vietnam War: A Concise International History . Oxford University Press.

Lewy, G. (1980). America in vietnam (Ser. A galaxy book, gb 601). Oxford University Press.

Mayer, F. (2014). Narrative politics : stories and collective . Oxford University Press.

Oliver, K. (2006) The My Lai Massacre in American History and Memory . Manchester University Press.

Sen. (2018, November 20). After Hell and Hollywood, Nick Ut basks in peace. VN Express. https://e.vnexpress.net/news/travel-life/after-hell-and-hollywood-nick-ut-basks-in-peace-3835521.html

Sontag, S. (2010). On photography. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Spector, R. H. (2020). Vietnam War. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War/The-Diem-regime-and-the-Viet-Cong

Stocchetti, M., and Kukkonen, K. (Eds.). (2011). Images in use: Towards the critical analysis of visual communication .

Taylor, J. (1998) Body Horror: Photojournalism, Catastrophe and War . New York: New York University Press.

Vitello, P. (2012, March 12). Horst Faas, Photographer Who Showed Horrors of War, Dies at 79. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/world/asia/horst-faas-vietnam-war-photographer-dies-at-79.html

Zelizer, B. (2010). About to Die: How News Images Move the Public . Oxford University Press.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

39 Photos That Captured the Human Side of the Vietnam War

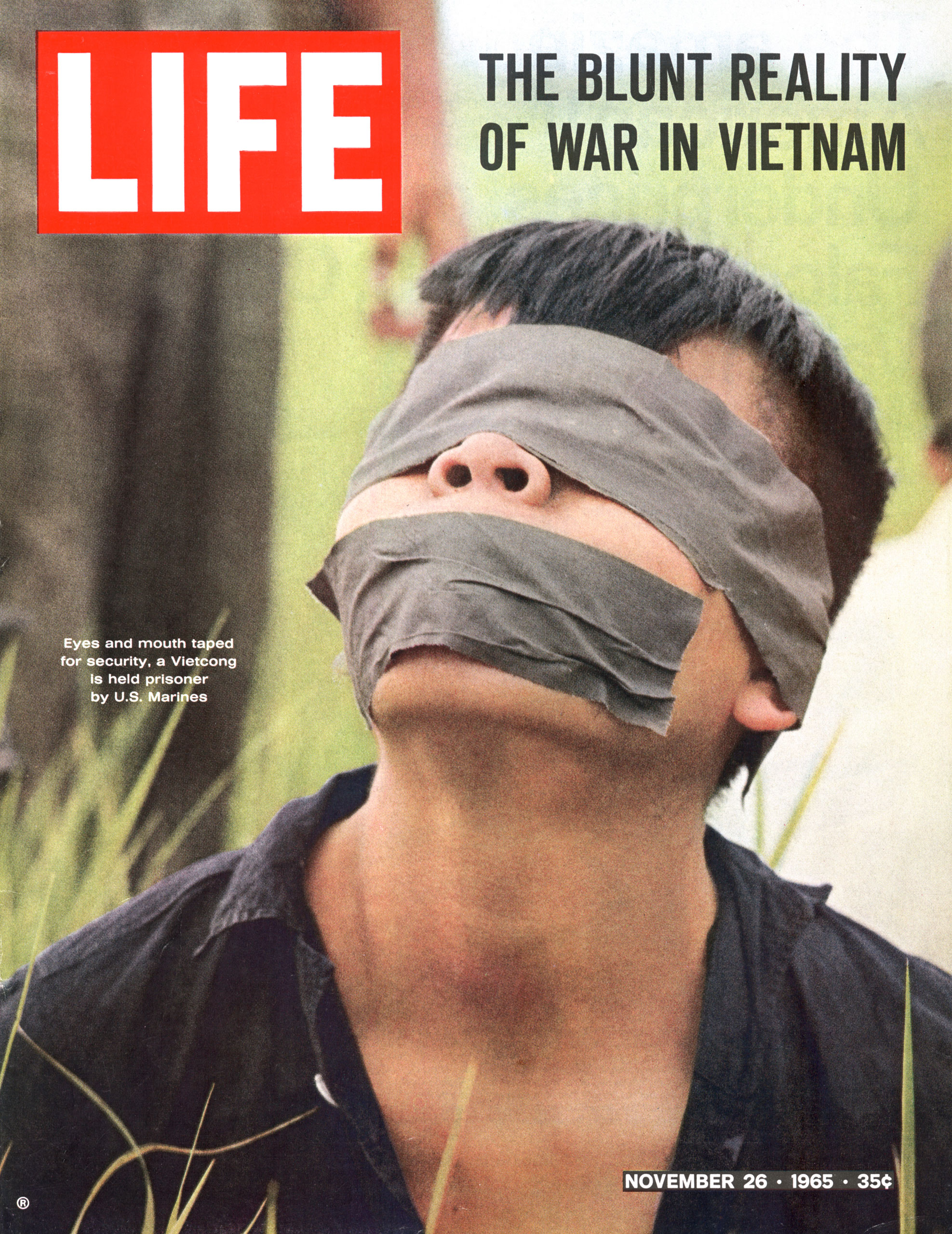

I n March 1965, 3,500 U.S. Marines landed in South Vietnam. By year’s end, there were 200,000 of them. When LIFE dispatched Associate Editor Michael Mok and Photographer Paul Schutzer to spend six weeks with them, the two men found the Marines mired in a world of ambiguity: They were at once dispatching lives and saving them, hailed as heroes and decried as villains.

Mok and Schutzer risked their lives to bring LIFE’s readers a 22-page photo essay on the “blunt reality” of the war—one that, Mok wrote, vividly called to mind scenes from Saipan in World War II and Inchon in the Korean War. “Only the locale is different, and this observer, now a generation older. No one used to call him ‘Pop’ or ‘Sir’ in the old days.”

The scenes the men captured, in images and words, reflect a world in which bullets and bandages were doled out in equal measure. The Marines carried out their missions, killing and capturing Viet Cong soldiers, but they also undertook a broader mission to win the hearts and minds of the people whose world they occupied. Treating the Vietnamese with dignity was as much a matter of human decency as it was a strategy to win the war: To acquire crucial intelligence from villagers, the Marines needed first to earn their trust.

The essay’s most enduring images are not those that portray scenes of battle and warfare, but those that capture the humanity of people embroiled in a situation not of their own making. There’s the Vietnamese mother carrying her wounded baby through her besieged village, and the U.S. Marine who scoops him up to get him to a medic, to no avail. There are Marines handing out dolls to children who have nothing, and children ripping them limb from limb, preferring the disembodied head of a doll to no doll at all.

The magazine chose a face to encapsulate the humanitarian side of American forces, and that face belonged to Hospitalman Second Class Josiah Lucier, 29. Nicknamed “The Doc,” Lucier’s primary job was to keep the Marines healthy. But, Mok wrote, “then there is the job he does because he wants to, which is holding sick call for all the villagers within walking distance.” Lucier treated his patients, especially the children, with a tenderness that’s palpable in photographs.

But he wasn’t Pollyannaish about the world he’d been living in for three years. Lucier carried a gun when he made house calls, never knowing where the enemy lurked. “I am a humanitarian and all that jazz,” he said, “but I am not completely out of my ever-lovin’ mind.”

For wartime readers, these images matched images of the faceless enemy with universal pictures of love and loss. They show another side to the soldier who might return home to be spit upon and scorned, a recipient of misplaced hatred.

The Marines, for their part, didn’t need to be greeted with protest signs to grapple with the gray area in which they lived each day. They had already internalized it. Said one, “Sometimes I feel like one of the bad guys … When we go into these villes and the people look at you in that sad kind of way they have, it’s pretty hard for me to imagine I’m wearing a white hat and riding a white horse.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk .

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Biden Drops Out of Presidential Race , Endorses Harris to Replace Him

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- ‘We’re Living in a Nightmare:’ Inside the Health Crisis of a Texas Bitcoin Town

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Stop Feeling Bad About Sweating

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Eliza Berman at [email protected]

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

The Agent Orange Syndrome

In the 1960s, the United States blanketed the Mekong River delta with Agent Orange, a chemical defoliant more devastating than napalm. Thirty years after the end of the Vietnam War, the chemical is still poisoning the water and coursing through the blood of a third generation. From Ho Chi Minh City to the town of Ben Tre—and from Greensboro, North Carolina, to Hackettstown, New Jersey—the photographer James Nachtwey went in search of the ecocide’s cruelest legacy, horribly deformed children in both Vietnam and America. Nachtwey, arguably the most celebrated war photographer of his generation, sees the former conflict in Southeast Asia as a touchstone for his work. “My decision to become a photographer,” he says, “was inspired by photographs from the Vietnam War.” This expanded photo essay from the land of Agent Orange—part of which appears in the August V.F. —makes clear, according to Nachtwey, that “the effects of war no longer end when the shooting stops.”

James Nachtwey/VII Photo

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Follow PetaPixel on YouTube

- Follow PetaPixel on Facebook

- Follow PetaPixel on X

- Follow PetaPixel on Instagram

How to Create a Photo Essay

The photographic essay, also called a photo essay or photo story, is a powerful way for photographers to tell a story with their images. If you are interested in creating your own photo essay, this article will guide you through the whole process, from finding a story to shoot to the basics of crafting your first visual narrative.

Table of Contents

What is a photo essay.

A photo essay tells a story visually. Just like the kind you read, the photo essay offers a complete rendering of a subject or situation using a series of carefully crafted and curated images. Photo stories have a theme, and each image backs up that overarching theme which is defined in the photo essay’s title and is sometimes supported with text.

From documentary to narrative to essay, photo stories are designed to move their audience, to inspire a certain action, awareness, or emotion. Photo stories are not just a collection of cool photos. They must use their visual power to capture viewers’ attention and remain unforgettable.

History of the Photo Story

In the “old days”, that is, before 1948, magazines ran photo stories very different from what we know today. They were staged, preconceived by an editor, not a truthful observation of life. Along came a photographer named W. Eugene Smith, who worked for Life magazine.

Deciding to follow a rural doctor for six weeks, he gathered material for a photo essay that really showed what it was like to be in that doctor’s shoes, always on the go to help his scattered patients. Smith’s piece, “ Country Doctor ,” shook other photographers out of their scripted stupor and revolutionized the way photographers report what they see.

From then on, photojournalism gained life and an audience through the lenses of legends like Robert Capa, Dorothea Lange, David “Chim” Seymour, Gordon Parks, Werner Bischof, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. The Vietnam War provided many examples for photo stories as represented by Philip Jones Griffiths, Catherine Leroy, and many more.

More recently, photo stories have found a sturdy home online thanks to the ease of publishing a series of photos digitally versus in print. Lynsey Addario, Peter Essick, and Adam Ferguson represent a few of the photographers pushing visual storytelling today.

Ways to Find Photo Stories and Themes

Photo stories exist all around, right in the midst of everyday life and in the fray of current events. A good place to begin developing a photo essay is by choosing a general theme.

Topics that Interest You

The best expression comes from the heart, so why not choose a topic that interests you. Maybe it’s a social issue, an environmental one, or just something you’re curious about. Find what moves you and share that with the world.

Personal Experiences

The more you’ve lived, the more you have to tell. This doesn’t necessarily mean age, it can also refer to experiences, big and small. If you know a subject better than most, like what it’s like to recover from a car crash, you’re an expert on the matter and therefore you have a story to tell. Also, consider the things you read and see or watch, like news or history, and incorporate that into your search for a story.

Problem/Solution

Problems abound in the world. But so do solutions. Photojournalists can present either, or both. Have a look at something that’s wrong in society and show why it’s a problem. Or find a problem that’s been resolved and show the struggle it took to get there. Even better, take your time shooting your story — sometimes it can take years — and document how a wrong is righted.

Day-in-the-Life

One of the most popular formats, day-in-the-life photo stories present microcosms of life that relate to the bigger picture. In a similar vein, behind-the-scenes photo stories show viewers what life is really like for others, especially in situations that are difficult or impossible to access. Events represent another simple yet powerful theme for documenting and storytelling with a camera.

Types of Photo Stories

Most photo stories concern people. If it’s about something like the environment, for example, the photo story can showcase the people involved. In either case, the impactful photo story will present the challenges and dilemmas of the human condition, viscerally.

There are three general types of photo stories.

Narrative Story

Narrative deals with complications and their resolution, problems, and solutions. If there appears to be no resolution, at least the struggle to find one can provide material for a photo essay. Some sort of narrative thread must push the story from beginning to middle to end, just like what you see in a good movie.

A good story also requires action, which in this case must be visual. Good stories are page-turners, whether they’re a Kerouac tale or a series of photos demonstrating the difficulties of single parenting. Adventure stories are one good example of photographic narrative storytelling.

The term “photo story” is generally used interchangeably with “photo essay”, but some photographers hold that there are subtle differences between the two. The essay type of photo story implies opinion, they argue. Essays make a point. They are the opposite of facts-only news. A photo story essay makes a case for something, like showing the danger and consequences of illegal fireworks or advocating for the preservation of a forest.

Documentary

On the other hand, documentaries lack opinion. Their purpose is to inform without adding judgment. Documentaries present the facts and let viewers decide. They illustrate something that’s occurring but they don’t always include a narrative story or an opinionated approach. Historical places, current events, and unique lifestyles always make for good documentary photo stories.

How to Craft a Photo Essay

Several elements come into play when putting together a photo essay. Once you’ve found a theme, it’s time to give your project a name. While out shooting, jot down titles that come to mind. Consider the title a magazine headline that explains in few words what the whole story is about.

Choose your photos according to whether or not they relate to and support the photo essay’s title. Reject those photos that don’t. If your collection seems to suggest a different angle, a different title, don’t be afraid to rename it. Sometimes stories develop organically. But if your title can’t assemble and define your selection of photos, maybe it’s too vague. Don’t rush it. Identify the theme, take the photos and the photo essay will take shape.

Certain techniques help tell the photo essay.

A photo essay is composed of a diversity of views, angles, and focal lengths. While masters like Henri Cartier-Bresson could capture a photo essay with a single prime lens, in his case a 50mm, the rest of us are wise to rely on multiple focal lengths. Just like what we see in the movies, a story is told with wide shots that set the scene, medium shots that tell the story, and close-ups that reveal character and emotion.

Unique angles make viewers curious and interested, and they break the monotony of standard photography. Consider working black-and-white into your photo essay. The photo essay lends itself well to reportage exclusively in monochrome, as the legends have demonstrated since W. Eugene Smith.

Visual Consistency

The idea of a photo essay is to create a whole, not a bunch of random parts. Think gestalt. The images must interact with each other. Repetition helps achieve this end. Recurring themes, moods, styles, people, things, and perspectives work to unify a project even if the photos tell different parts of the story.

Text can augment the impact of a photo essay. A photo may be worth a thousand words, but it doesn’t always replace them. Captions can be as short as a complete sentence, as long as a paragraph, or longer. Make sure to take notes in case you want to add captions. Some photo stories, however, function just fine without words.

Tell a Story as a Photographer

Few genres of photography have moved people like the photo essay. Since its inception, the art of visual storytelling has captivated audiences. Photo stories show viewers things they had never seen, have moved masses to action, and have inspired video documentaries. Today, photo stories retain their power and place, in part thanks to the internet. Every photographer should experiment with a photo essay or two.

The method of crafting a photo essay is simple yet complicated, just like life. Careful attention must be paid to the selection of images, the choice of title, and the techniques used in shooting. But follow these guidelines and the photo stories will come. Seek issues and experiences that inspire you and go photograph them with the intention of telling a complete story. The viewing world will thank you.

Image credits: Header photo shows the May 13, 1957 story in LIFE magazine titled, “ The Tough Miracle Man of Vietnam .” Stock photos from Depositphotos

Vietnam War: 6 personal essays describe the sting of a tragic conflict

The Vietnam War touched millions of lives. Within these personal essays from people who took part in the filming of The Vietnam War , are lessons about what happened, what it meant then and what we can learn from it now.

Long ago and far away, we fought a war in which more than 58,000 Americans died and hundreds of thousands of others were wounded. The war meant death for an estimated 3 million Vietnamese, North and South. The fighting dragged on for almost a decade, polarizing the American people, dividing the country and creating distrust of our government that remains with us today.

In one way or another, Vietnam has overshadowed every national security decision since.

We were told that our mission was to prevent South Vietnam from falling to communism. Very lofty. But the men I led as a young infantry platoon leader and later as a company commander weren’t fighting for that mission. Mostly draftees, they were terrific soldiers. They were fighting, I realized, for each other — to simply survive their year in-country and go home.

I had grown up as an “Army brat.” To me, the Army was like a second family. In Vietnam, the radio code word for our division’s infantry companies was family . A “rucksack outfit,” my company would disappear into the jungle, moving quietly, staying in the field for weeks. We all ate the same rations and endured the same heat, humidity, mosquitoes, leeches, skin rashes, jungle itch. We were like pack animals, carrying upwards of 60 pounds of gear, water, ammunition — and even more for the radio operators and machine gunners. I was impressed by how the men endured it all, especially the draftees who had answered the call to service.

I learned much about leadership. I was once counseled by a senior officer “not to be too worried about your men.” Incredible. I was concerned about my men’s safety at all times. Even though my company lost very few, I remember each of those deaths vividly. They were all good men, in a war very few understood.

On both of my combat tours, in 1968 at Huê´ during the Tet Offensive and in 1969-70 in the triple-canopy rainforests along the Cambodian border, we fought soldiers of the North Vietnamese army. They were good light infantry; I had respect for their determination and abilities. But they were the enemy; our job was to kill or capture them.

Though we were conducting a war of attrition, we were actually fighting the enemy’s birth rate. He was prepared and determined to keep fighting as long as he had the manpower to send south.

In terms of strategy, it seemed a war out of “Alice in Wonderland.” The Ho Chi Minh Trail, the enemy’s major supply line and infiltration route, ran through Cambodia and Laos. Yet until May 1970, both of those countries were off limits to U.S. ground forces. We bombed the trail incessantly, but the enemy’s ability to move troops and equipment south never seemed to slack. We never invaded North Vietnam. As demonstrated during Tet in ’68, the enemy could control the tempo of the war when he wished. We, on the other hand, would use unilaterally declared “truce” periods and would halt bombing to signal something never clearly defined — a willingness to talk, I imagined, which the enemy ignored.

Looking back, if our strategy was intended to force the enemy to say “enough,” resulting in a stalemate situation like that at the end of the Korean War, would the South Vietnamese have been able to defend themselves, independently? Unlikely.

Would the U.S. have been willing to commit and maintain American forces in South Vietnam indefinitely? Also unlikely.

Did we learn anything from that experience, which left such an indelible mark on our national psyche? History is a harsh teacher; there are still no easy answers.

Hal Kushner

When I deployed to Vietnam in August 1967, I was a young Army doctor, married five years, with a 3-year-old daughter, just potty trained, and another child due the following April. When I returned from Vietnam in late March 1973, I saw my 5-year-old son for the first time, and my daughter was in the fifth grade. In the interim, we had landed on the moon; there was women’s lib, Nixon had gone to China; Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated.

I was the only doctor captured in the 10-year Vietnam War. I was back from the dead.

We prisoners endured unspeakable horror, brutality and deprivation, and we saw and experienced things no human should ever witness. Our mortality rate was almost 50% — higher even than at the brutal Civil War prisons at Andersonville or Elmira a century earlier. I cradled 10 dying men in my arms as they breathed their last and spoke of home and family; then we buried them in crude graves, marked with stones and bamboo, and eulogized them with words of sunshine and hope, country and family. The eulogies were for the survivors, of course; they always are.

On the Fourth of July in five successive years, we sang patriotic songs, but very softly, so our captors couldn’t hear the forbidden words, and we cried. One of us had a missal issued by the Marine Corps, our only book, but our captors had torn out the pages with the American flag and The Star-Spangled Banner .

At my release in Hanoi, I was shocked by the hair and dress of the reporters there. Once home, I saw television and movies with frank profanity and sex. When I left, Lucy and Desi slept in twin beds. I left Ozzie and Harriett and returned to Taxi Driver . What had happened to my country? Why did we suffer and sacrifice?

When my aircraft crashed on Nov. 30, 1967, I collided with one planet and returned to another. The Vietnam War, which had about one-fifth of the casualties of World War II but had lasted three times as long, had changed the country as much as the greatest cataclysm in world history. It had changed forever the way we think of our government and ourselves. The country had lost its innocence — and, for a time, its confidence.

This war, which had such a great impact on my life, is a dim memory today. There are 58,000 names on that wall, and it rates but a few pages in a high school history book.

I am dismayed by how little our young people know about Vietnam, and how misunderstood it is by others. The Vietnam War is as remote to them as the War of 1812 or the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Now, 40 years later, we must try to understand.

Hal Kushner joined the Army and served as a flight surgeon in Vietnam. In 1967, he was captured by the Viet Cong after surviving a helicopter crash. He spent nearly six years as a prisoner of war. He lives in Daytona Beach, Fla.

p.p1{margin:0px;font:19px Times;-webkit-text-stroke:#000000}span.s1{font-kerning:none;background-color:#e0ebf6}span.s2{font-kerning:none} Mai Elliott

Having lived through war and seen what it did to my family and to millions of Vietnamese, I feel grateful for the peace and stability I now enjoy in the United States.

In Vietnam, my family and I experienced what it was like to be caught in bombing and fighting, and what it was like to flee our home and survive as refugees.

During World War II, in my childhood, we huddled in shelters as Allied planes targeting Japanese positions bombed the town in the North where we lived.