Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

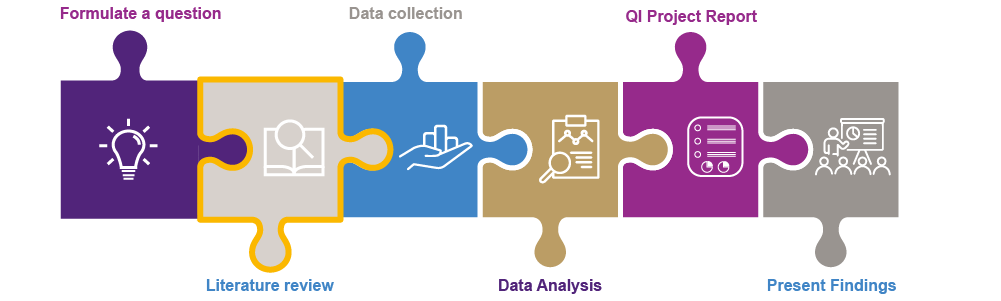

The Literature Review

29 The Five ‘C’s of Writing a Literature Review

To help you frame and write your literature review, think about these five ‘c’s (Callahan, 2014).

- Cite the material you have referred to and used to help you define the research problem that you will study.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methods, and findings expressed in the literature. For example, describe where the various researchers agree and where they disagree. Describe the similarities and dissimilarities in approaches to studying related research problems.

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methods, approaches, and controversies apparent and/or described in the literature. For example, describe what major areas are contested, controversial and/or still in debate.

- Critique the literature. Describe which arguments you find more persuasive and explain why. Explain which approaches, findings, and methods seem most reliable, valid, appropriate, and/or most popular and why. Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what previous researchers have stated (e.g. asserts, demonstrates, argues, clarifies, etc.).

- Connect the various research studies you reviewed. Describe how your work utilizes, draws upon, departs from, synthesizes, adds to or extends previous research studies.

An Introduction to Research Methods in Sociology Copyright © 2019 by Valerie A. Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

To help you frame and write your literature review, think about these five c’s (Callahan, 2014):

- Cite the material you have referred to and used to help you define the research problem that you will study.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methods, and findings expressed in the literature.For example, describe where the various researchers agree and where they disagree. Describe the similarities and dissimilarities in approaches to studying related research problems.

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methods, approaches, and controversies apparent and/or described in the literature. For example, describe what major areas are contested, controversial and/or still in debate.

- Critique the literature. Describe which arguments you find more persuasive and explain why. Explain which approaches, findings, and methods seem most reliable, valid, appropriate, and/or most popular and why. Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what previous researchers have stated (e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, clarifies, etc.).

- Connect the various research studies you reviewed. Describe how your work utilizes, draws upon, departs from, synthesizes, adds to or extends previous research studies.

Research Methods, Data Collection and Ethics Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A Royal Conservatoire of Scotland Portal site

- Introduction to academic writing

- Personal organisational skills

- Research skills

- Developing criticality

- Literature review

- Sections of your project

- Developing your academic writing

- Types of academic submission

- Research design

- Developing assessment criteria for rubrics

The five 'C's of a Literature Review

The following five headings are useful to keep in mind when writing the literature review:

- Cite : keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare : the various arguments, theories, methodologies and findings expressed in the literature: What do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analysing the research problem?

- Contrast : the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: What are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate?

- Critique : which arguments are more persuasive and why? Which approaches, findings, methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does (e.g. suggests, asserts, demonstrates, etc.)

- Connect : the literature to your own area of research and investigation: How does your own work draw upon, depart from, or synthesise what has been said in the literature?

(Adapted from Sudheesh, Duggappa , Nethra, 2016).

Sudheesh K., Duggappa D.R., Nethra S.S. (2016) ‘How to write a research proposal?’ Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 pp. 631-4.

- Search for:

© 2024 PGLT Academic Toolkit

Theme by Anders Norén — Up ↑

15 The 5 Cs of a literature review

To help you frame and write your literature review, think about these five ‘C’s (Callahan, 2014).

- Cite the material you have referred to and used to help you define the research problem that you will study.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methods, and findings expressed in the literature. For example, describe where the various researchers agree and where they disagree. Describe the similarities and dissimilarities in approaches to studying related research problems.

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methods, approaches, and controversies apparent and/or described in the literature. For example, describe what major areas are contested, controversial and/or still in debate.

- Critique the literature. Describe which arguments you find more persuasive and explain why. Explain which approaches, findings, and methods seem most reliable, valid, appropriate, and/or most popular and why. Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what previous researchers have stated (e.g. asserts, demonstrates, argues, clarifies, etc.).

- Connect the various research studies you reviewed. Describe how your work utilises, draws upon, departs from, synthesises, adds to or extends previous research studies.

Understanding the difference between a literature review and an essay

So now that you know what a literature review is and how to write it, it is important to understand how a literature review is different from an essay. First of all, it is necessary to point out that many students struggle with understanding the difference between a literature review and an essay. This is particularly so because a student can use the exact same resources to create a literature review or an essay; however, what is different about the two is where the emphasis in the writing is placed (Thomas, 2012).

As discussed previously, a literature review focuses on everything that has been written about a particular topic, theory, or research. It is focused on the research and the researchers who have undertaken research on your topic. In contrast, an essay focuses on proving a point. It does not need to provide an extensive coverage of all of the material on the topic. In fact, the writer chooses only those sources that prove the point. Most professors will expect to see you discuss a few different perspectives from the materials that run contrary to the point you are trying to make. For example, suppose you want to write an essay about the negative effects of shiftwork on nurses. You would gather material to show that shiftwork negatively affects nurses, and the various ways it affects nurses. Now in this case, you might find the odd research paper that states shiftwork has no effect – although, I doubt it, because it has been extensively documented to have a negative affect. However, the point is that with an essay you are focused on providing information on your topic and proving your point.

Understanding the difference between a literature review and an annotated bibliography

There is a third type of academic writing that can also confuse students who are attempting to write a literature review and that is an annotated bibliography. An annotated bibliography provides all of the reference details of a bibliography, but it goes one step further and provides a short (approximately 150 words) description of the reference. An annotated bibliography is not to be confused with a bibliography. A bibliography is a list of journal articles, books, and other resources that someone has utilised in writing. The bibliography, provides a list of all resources that someone used to write a research paper and, unlike a reference list, includes references that may not appear in the body of the paper. No doubt you have had to create many bibliographies in your academic studies. Visit Writing an annotated bibliography (PDF, 677KB) to learn more and see a sample of an annotated bibliography.

Callahan, J. L. (2014). Writing literature reviews: A reprise and update. Human Resource Development Review , 13 (3), 271-275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484314536705

Thomas, J. (2012, September 26). Literature review vs. essay. https://blogs.qut.edu.au/library/2012/09/26/literature-review-vs-essay/

This chapter was adapted from “ The five ‘C’s of writing a literature review ” in An introduction to research methods in sociology by Valerie A. Sheppard, used under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Quality in Healthcare: Assessing What We Do Copyright © 2024 by The University of Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

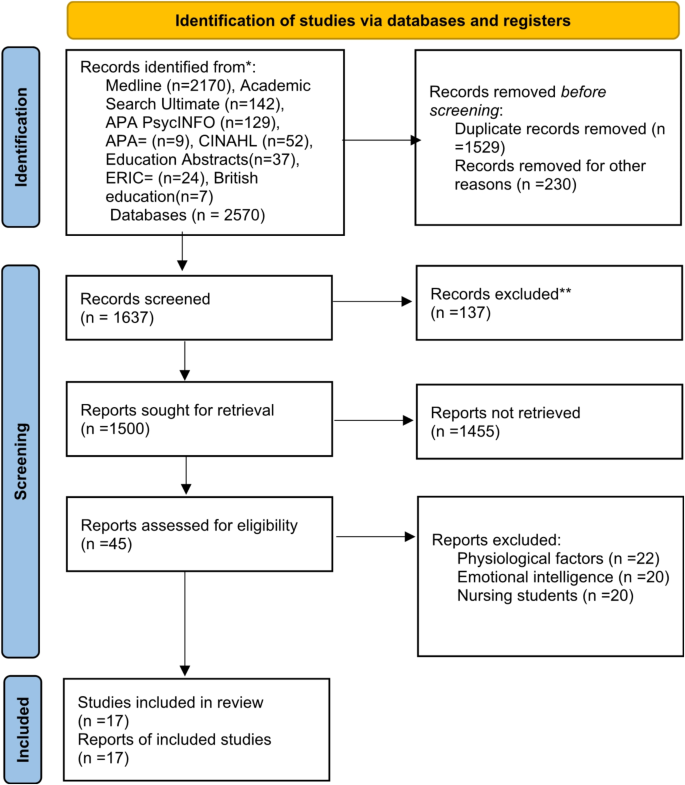

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time

SciSpace Discover’s personalized suggestion engine helps you stay on course and get the complete picture of the topic from one place. Every time you visit an article page, it provides you links to related papers. Besides that, it helps you understand what’s trending, who are the top authors, and who are the leading publishers on a topic.

Make referring sources super easy

To ensure you don't lose track of your sources, you must start noting down your references when doing the literature review. SciSpace Discover makes this step effortless. Click the 'cite' button on an article page, and you will receive preloaded citation text in multiple styles — all you've to do is copy-paste it into your manuscript.

Final tips on how to write a literature review

A massive chunk of time and effort is required to write a good literature review. But, if you go about it systematically, you'll be able to save a ton of time and build a solid foundation for your research.

We hope this guide has helped you answer several key questions you have about writing literature reviews.

Would you like to explore SciSpace Discover and kick off your literature search right away? You can get started here .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to start a literature review.

• What questions do you want to answer?

• What sources do you need to answer these questions?

• What information do these sources contain?

• How can you use this information to answer your questions?

2. What to include in a literature review?

• A brief background of the problem or issue

• What has previously been done to address the problem or issue

• A description of what you will do in your project

• How this study will contribute to research on the subject

3. Why literature review is important?

The literature review is an important part of any research project because it allows the writer to look at previous studies on a topic and determine existing gaps in the literature, as well as what has already been done. It will also help them to choose the most appropriate method for their own study.

4. How to cite a literature review in APA format?

To cite a literature review in APA style, you need to provide the author's name, the title of the article, and the year of publication. For example: Patel, A. B., & Stokes, G. S. (2012). The relationship between personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 16-21

5. What are the components of a literature review?

• A brief introduction to the topic, including its background and context. The introduction should also include a rationale for why the study is being conducted and what it will accomplish.

• A description of the methodologies used in the study. This can include information about data collection methods, sample size, and statistical analyses.

• A presentation of the findings in an organized format that helps readers follow along with the author's conclusions.

6. What are common errors in writing literature review?

• Not spending enough time to critically evaluate the relevance of resources, observations and conclusions.

• Totally relying on secondary data while ignoring primary data.

• Letting your personal bias seep into your interpretation of existing literature.

• No detailed explanation of the procedure to discover and identify an appropriate literature review.

7. What are the 5 C's of writing literature review?

• Cite - the sources you utilized and referenced in your research.

• Compare - existing arguments, hypotheses, methodologies, and conclusions found in the knowledge base.

• Contrast - the arguments, topics, methodologies, approaches, and disputes that may be found in the literature.

• Critique - the literature and describe the ideas and opinions you find more convincing and why.

• Connect - the various studies you reviewed in your research.

8. How many sources should a literature review have?

When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. if it is a self-contained paper in itself, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

9. Can literature review have diagrams?

• To represent an abstract idea or concept

• To explain the steps of a process or procedure

• To help readers understand the relationships between different concepts

10. How old should sources be in a literature review?

Sources for a literature review should be as current as possible or not older than ten years. The only exception to this rule is if you are reviewing a historical topic and need to use older sources.

11. What are the types of literature review?

• Argumentative review

• Integrative review

• Methodological review

• Systematic review

• Meta-analysis review

• Historical review

• Theoretical review

• Scoping review

• State-of-the-Art review

12. Is a literature review mandatory?

Yes. Literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It is a critical step in the process that allows you to establish the scope of your research, and provide a background for the rest of your work.

But before you go,

- Six Online Tools for Easy Literature Review

- Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review

- Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 26, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

excellent , thank you

Thank you for this significant piece of information.

This piece of information is very helpful. Thank you so much and look forward to hearing more literature review from you in near the future.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

University Library

Write a literature review.

- Examples and Further Information

1. Introduction

Not to be confused with a book review, a literature review surveys scholarly articles, books and other sources (e.g. dissertations, conference proceedings) relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, providing a description, summary, and critical evaluation of each work. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic.

2. Components

Similar to primary research, development of the literature review requires four stages:

- Problem formulation—which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues?

- Literature search—finding materials relevant to the subject being explored

- Data evaluation—determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic

- Analysis and interpretation—discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature

Literature reviews should comprise the following elements:

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review

- Division of works under review into categories (e.g. those in support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative theses entirely)

- Explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

In assessing each piece, consideration should be given to:

- Provenance—What are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity—Is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness—Which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value—Are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

3. Definition and Use/Purpose

A literature review may constitute an essential chapter of a thesis or dissertation, or may be a self-contained review of writings on a subject. In either case, its purpose is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to the understanding of the subject under review

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration

- Identify new ways to interpret, and shed light on any gaps in, previous research

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort

- Point the way forward for further research

- Place one's original work (in the case of theses or dissertations) in the context of existing literature

The literature review itself, however, does not present new primary scholarship.

- Next: Examples and Further Information >>

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License except where otherwise noted.

Land Acknowledgement

The land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, comprised of the descendants of indigenous people taken to missions Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista during Spanish colonization of the Central Coast, is today working hard to restore traditional stewardship practices on these lands and heal from historical trauma.

The land acknowledgement used at UC Santa Cruz was developed in partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Chairman and the Amah Mutsun Relearning Program at the UCSC Arboretum .

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE: Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review