Chapter 4: Civil Liberties

What Are Civil Liberties?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define civil liberties and civil rights

- Describe the origin of civil liberties in the U.S. context

- Identify the key positions on civil liberties taken at the Constitutional Convention

- Explain the Civil War origin of concern that the states should respect civil liberties

The U.S. Constitution —in particular, the first ten amendments that form the Bill of Rights—protects the freedoms and rights of individuals. It does not limit this protection just to citizens or adults; instead, in most cases, the Constitution simply refers to “persons,” which over time has grown to mean that even children, visitors from other countries, and immigrants—permanent or temporary, legal or undocumented—enjoy the same freedoms when they are in the United States or its territories as adult citizens do. So, whether you are a Japanese tourist visiting Disney World or someone who has stayed beyond the limit of days allowed on your visa, you do not sacrifice your liberties. In everyday conversation, we tend to treat freedoms, liberties, and rights as being effectively the same thing—similar to how separation of powers and checks and balances are often used as if they are interchangeable, when in fact they are distinct concepts.

DEFINING CIVIL LIBERTIES

To be more precise in their language, political scientists and legal experts make a distinction between civil liberties and civil rights, even though the Constitution has been interpreted to protect both. We typically envision civil liberties as being limitations on government power, intended to protect freedoms that governments may not legally intrude on. For example, the First Amendment denies the government the power to prohibit “the free exercise” of religion; the states and the national government cannot forbid people to follow a religion of their choice, even if politicians and judges think the religion is misguided, blasphemous, or otherwise inappropriate. You are free to create your own religion and recruit followers to it (subject to the U.S. Supreme Court deeming it a religion), even if both society and government disapprove of its tenets. That said, the way you practice your religion may be regulated if it impinges on the rights of others. Similarly, the Eighth Amendment says the government cannot impose “cruel and unusual punishments” on individuals for their criminal acts. Although the definitions of cruel and unusual have expanded over the years, as we will see later in this chapter, the courts have generally and consistently interpreted this provision as making it unconstitutional for government officials to torture suspects.

Civil rights, on the other hand, are guarantees that government officials will treat people equally and that decisions will be made on the basis of merit rather than race, gender, or other personal characteristics. Because of the Constitution’s civil rights guarantee, it is unlawful for a school or university run by a state government to treat students differently based on their race, ethnicity, age, sex, or national origin. In the 1960s and 1970s, many states had separate schools where only students of a certain race or gender were able to study. However, the courts decided that these policies violated the civil rights of students who could not be admitted because of those rules. [1]

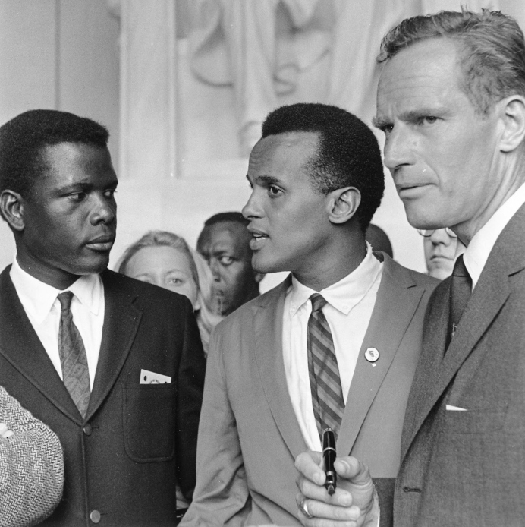

The idea that Americans—indeed, people in general—have fundamental rights and liberties was at the core of the arguments in favor of their independence. In writing the Declaration of Independence in 1776, Thomas Jefferson drew on the ideas of John Locke to express the colonists’ belief that they had certain inalienable or natural rights that no ruler had the power or authority to deny to his or her subjects. It was a scathing legal indictment of King George III for violating the colonists’ liberties. Although the Declaration of Independence does not guarantee specific freedoms, its language was instrumental in inspiring many of the states to adopt protections for civil liberties and rights in their own constitutions, and in expressing principles of the founding era that have resonated in the United States since its independence. In particular, Jefferson’s words “all men are created equal” became the centerpiece of struggles for the rights of women and minorities (Figure) .

CIVIL LIBERTIES AND THE CONSTITUTION

The Constitution as written in 1787 did not include a Bill of Rights , although the idea of including one was proposed and, after brief discussion, dismissed in the final week of the Constitutional Convention. The framers of the Constitution believed they faced much more pressing concerns than the protection of civil rights and liberties, most notably keeping the fragile union together in the light of internal unrest and external threats.

Moreover, the framers thought that they had adequately covered rights issues in the main body of the document. Indeed, the Federalists did include in the Constitution some protections against legislative acts that might restrict the liberties of citizens, based on the history of real and perceived abuses by both British kings and parliaments as well as royal governors. In Article I , Section 9, the Constitution limits the power of Congress in three ways: prohibiting the passage of bills of attainder, prohibiting ex post facto laws, and limiting the ability of Congress to suspend the writ of habeas corpus.

A bill of attainder is a law that convicts or punishes someone for a crime without a trial, a tactic used fairly frequently in England against the king’s enemies. Prohibition of such laws means that the U.S. Congress cannot simply punish people who are unpopular or seem to be guilty of crimes. An ex post facto law has a retroactive effect: it can be used to punish crimes that were not crimes at the time they were committed, or it can be used to increase the severity of punishment after the fact.

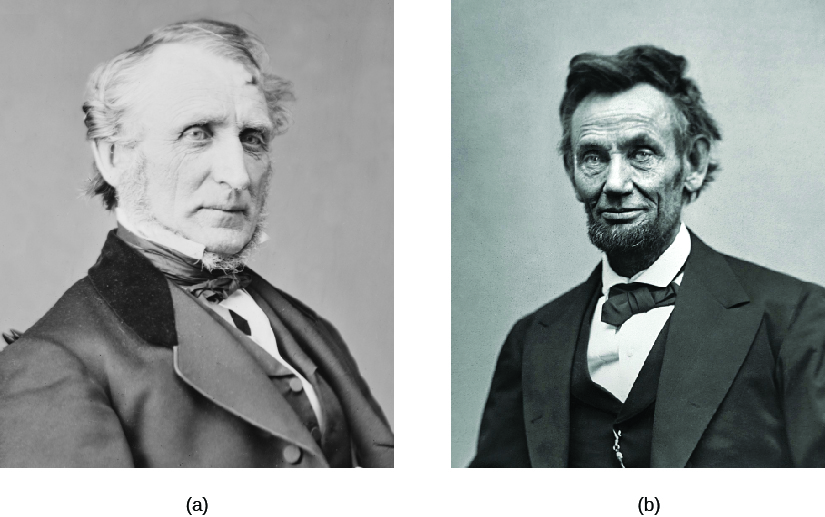

Finally, the writ of habeas corpus is used in our common-law legal system to demand that a neutral judge decide whether someone has been lawfully detained. Particularly in times of war, or even in response to threats against national security, the government has held suspected enemy agents without access to civilian courts, often without access to lawyers or a defense, seeking instead to try them before military tribunals or detain them indefinitely without trial. For example, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln detained suspected Confederate saboteurs and sympathizers in Union-controlled states and attempted to have them tried in military court s, leading the Supreme Court to rule in Ex parte Milligan that the government could not bypass the civilian court system in states where it was operating. [2]

During World War II, the Roosevelt administration interned Japanese Americans and had other suspected enemy agents—including U.S. citizens—tried by military courts rather than by the civilian justice system, a choice the Supreme Court upheld in Ex parte Quirin (Figure) . [3]

More recently, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the Bush and Obama administrations detained suspected terrorists captured both within and outside the United States and sought, with mixed results, to avoid trials in civilian courts. Hence, there have been times in our history when national security issues trumped individual liberties.

Debate has always swirled over these issues. The Federalists reasoned that the limited set of enumerated powers of Congress, along with the limitations on those powers in Article I , Section 9, would suffice, and no separate bill of rights was needed. Alexander Hamilton , writing as Publius in Federalist No. 84, argued that the Constitution was “merely intended to regulate the general political interests of the nation,” rather than to concern itself with “the regulation of every species of personal and private concerns.” Hamilton went on to argue that listing some rights might actually be dangerous, because it would provide a pretext for people to claim that rights not included in such a list were not protected. Later, James Madison , in his speech introducing the proposed amendments that would become the Bill of Rights, acknowledged another Federalist argument: “It has been said, that a bill of rights is not necessary, because the establishment of this government has not repealed those declarations of rights which are added to the several state constitutions.” [4]

For that matter, the Articles of Confederation had not included a specific listing of rights either.

However, the Anti-Federalists argued that the Federalists’ position was incorrect and perhaps even insincere. The Anti-Federalists believed provisions such as the elastic clause in Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution would allow Congress to legislate on matters well beyond the limited ones foreseen by the Constitution’s authors; thus, they held that a bill of rights was necessary. One of the Anti-Federalists, Brutus , whom most scholars believe to be Robert Yates , wrote: “The powers, rights, and authority, granted to the general government by this Constitution, are as complete, with respect to every object to which they extend, as that of any state government—It reaches to every thing which concerns human happiness—Life, liberty, and property, are under its controul [sic]. There is the same reason, therefore, that the exercise of power, in this case, should be restrained within proper limits, as in that of the state governments.” [5]

The experience of the past two centuries has suggested that the Anti-Federalists may have been correct in this regard; while the states retain a great deal of importance, the scope and powers of the national government are much broader today than in 1787—likely beyond even the imaginings of the Federalists themselves.

The struggle to have rights clearly delineated and the decision of the framers to omit a bill of rights nearly derailed the ratification process. While some of the states were willing to ratify without any further guarantees, in some of the larger states—New York and Virginia in particular—the Constitution’s lack of specified rights became a serious point of contention. The Constitution could go into effect with the support of only nine states, but the Federalists knew it could not be effective without the participation of the largest states. To secure majorities in favor of ratification in New York and Virginia, as well as Massachusetts, they agreed to consider incorporating provisions suggested by the ratifying states as amendments to the Constitution.

Ultimately, James Madison delivered on this promise by proposing a package of amendments in the First Congress, drawing from the Declaration of Rights in the Virginia state constitution, suggestions from the ratification conventions, and other sources, which were extensively debated in both houses of Congress and ultimately proposed as twelve separate amendments for ratification by the states. Ten of the amendments were successfully ratified by the requisite 75 percent of the states and became known as the Bill of Rights (Figure) .

| Rights and Liberties Protected by the First Ten Amendments | |

|---|---|

| First Amendment | Right to freedoms of religion and speech; right to assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances |

| Second Amendment | Right to keep and bear arms to maintain a well-regulated militia |

| Third Amendment | Right to not house soldiers during time of war |

| Fourth Amendment | Right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure |

| Fifth Amendment | Rights in criminal cases, including due process and indictment by grand jury for capital crimes, as well as the right not to testify against oneself |

| Sixth Amendment | Right to a speedy trial by an impartial jury |

| Seventh Amendment | Right to a jury trial in civil cases |

| Eighth Amendment | Right to not face excessive bail, excessive fines, or cruel and unusual punishment |

| Ninth Amendment | Rights retained by the people, even if they are not specifically enumerated by the Constitution |

| Tenth Amendment | States’ rights to powers not specifically delegated to the federal government |

| One of the most serious debates between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists was over the necessity of limiting the power of the new federal government with a Bill of Rights. As we saw in this section, the Federalists believed a Bill of Rights was unnecessary—and perhaps even dangerous to liberty, because it might invite violations of rights that weren’t included in it—while the Anti-Federalists thought the national government would prove adept at expanding its powers and influence and that citizens couldn’t depend on the good judgment of Congress alone to protect their rights. As George Washington’s call for a bill of rights in his first inaugural address suggested, while the Federalists ultimately had to add the Bill of Rights to the Constitution in order to win ratification, and the Anti-Federalists would soon be proved right that the national government might intrude on civil liberties. In 1798, at the behest of President John Adams during the Quasi-War with France, Congress passed a series of four laws collectively known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These were drafted to allow the president to imprison or deport foreign citizens he believed were “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States” and to restrict speech and newspaper articles that were critical of the federal government or its officials; the laws were primarily used against members and supporters of the opposition Democratic-Republican Party. State laws and constitutions protecting free speech and freedom of the press proved ineffective in limiting this new federal power. Although the courts did not decide on the constitutionality of these laws at the time, most scholars believe the Sedition Act, in particular, would be unconstitutional if it had remained in effect. Three of the four laws were repealed in the Jefferson administration, but one—the Alien Enemies Act—remains on the books today. Two centuries later, the issue of free speech and freedom of the press during times of international conflict remains a subject of public debate.

|

EXTENDING THE BILL OF RIGHTS TO THE STATES

In the decades following the Constitution’s ratification, the Supreme Court declined to expand the Bill of Rights to curb the power of the states, most notably in the 1833 case of Barron v. Baltimore . [6]

In this case, which dealt with property rights under the Fifth Amendment , the Supreme Court unanimously decided that the Bill of Rights applied only to actions by the federal government. Explaining the court’s ruling, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that it was incorrect to argue that “the Constitution was intended to secure the people of the several states against the undue exercise of power by their respective state governments; as well as against that which might be attempted by their [Federal] government.”

In the wake of the Civil War, however, the prevailing thinking about the application of the Bill of Rights to the states changed. Soon after slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment , state governments—particularly those in the former Confederacy—began to pass “black codes” that restricted the rights of former slaves and effectively relegated them to second-class citizenship under their state laws and constitutions. Angered by these actions, members of the Radical Republican faction in Congress demanded that the laws be overturned. In the short term, they advocated suspending civilian government in most of the southern states and replacing politicians who had enacted the black codes. Their long-term solution was to propose two amendments to the Constitution to guarantee the rights of freed slaves on an equal standing with whites; these rights became the Fourteenth Amendment , which dealt with civil liberties and rights in general, and the Fifteenth Amendment , which protected the right to vote in particular (Figure) . But, the right to vote did not yet apply to women or to Native Americans.

With the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, civil liberties gained more clarification. First, the amendment says, “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States,” which is a provision that echoes the privileges and immunities clause in Article IV , Section 2, of the original Constitution ensuring that states treat citizens of other states the same as their own citizens. (To use an example from today, the punishment for speeding by an out-of-state driver cannot be more severe than the punishment for an in-state driver). Legal scholars and the courts have extensively debated the meaning of this privileges or immunities clause over the years; some have argued that it was supposed to extend the entire Bill of Rights (or at least the first eight amendments) to the states, while others have argued that only some rights are extended. In 1999, Justice John Paul Stevens , writing for a majority of the Supreme Court, argued in Saenz v. Roe that the clause protects the right to travel from one state to another. [7]

More recently, Justice Clarence Thomas argued in the 2010 McDonald v. Chicago ruling that the individual right to bear arms applied to the states because of this clause. [8]

The second provision of the Fourteenth Amendment that pertains to applying the Bill of Rights to the states is the due process clause, which says, “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” This provision is similar to the Fifth Amendment in that it also refers to “due process,” a term that generally means people must be treated fairly and impartially by government officials (or with what is commonly referred to as substantive due process). Although the text of the provision does not mention rights specifically, the courts have held in a series of cases that it indicates there are certain fundamental liberties that cannot be denied by the states. For example, in Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Supreme Court ruled that states could not deny unemployment benefits to an individual who turned down a job because it required working on the Sabbath. [9]

Beginning in 1897, the Supreme Court has found that various provisions of the Bill of Rights protecting these fundamental liberties must be upheld by the states, even if their state constitutions and laws do not protect them as fully as the Bill of Rights does—or at all. This means there has been a process of selective incorporation of the Bill of Rights into the practices of the states; in other words, the Constitution effectively inserts parts of the Bill of Rights into state laws and constitutions, even though it doesn’t do so explicitly. When cases arise to clarify particular issues and procedures, the Supreme Court decides whether state laws violate the Bill of Rights and are therefore unconstitutional.

For example, under the Fifth Amendment a person can be tried in federal court for a felony—a serious crime—only after a grand jury issues an indictment indicating that it is reasonable to try the person for the crime in question. (A grand jury is a group of citizens charged with deciding whether there is enough evidence of a crime to prosecute someone.) But the Supreme Court has ruled that states don’t have to use grand juries as long as they ensure people accused of crimes are indicted using an equally fair process.

Selective incorporation is an ongoing process. When the Supreme Court initially decided in 2008 that the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to keep and bear arms, it did not decide then that it was a fundamental liberty the states must uphold as well. It was only in the McDonald v. Chicago case two years later that the Supreme Court incorporated the Second Amendment into state law. Another area in which the Supreme Court gradually moved to incorporate the Bill of Rights regards censorship and the Fourteenth Amendment. In Near v. Minnesota (1931), the Court disagreed with state courts regarding censorship and ruled it unconstitutional except in rare cases. [10]

The Bill of Rights is designed to protect the freedoms of individuals from interference by government officials. Originally these protections were applied only to actions by the national government; different sets of rights and liberties were protected by state constitutions and laws, and even when the rights themselves were the same, the level of protection for them often differed by definition across the states. Since the Civil War, as a result of the passage and ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment and a series of Supreme Court decisions, most of the Bill of Rights’ protections of civil liberties have been expanded to cover actions by state governments as well through a process of selective incorporation. Nonetheless there is still vigorous debate about what these rights entail and how they should be balanced against the interests of others and of society as a whole.

- Green v. County School Board of New Kent County , 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Allen v. Wright , 468 U.S. 737 (1984). ↵

- Ex parte Milligan , 71 U.S. 2 (1866). ↵

- Ex parte Quirin , 317 U.S. 1 (1942); See William H. Rehnquist. 1998. All the Laws but One: Civil Liberties in Wartime . New York: William Morrow. ↵

- American History from Revolution to Reconstruction and Beyond, “Madison Speech Proposing the Bill of Rights June 8 1789,” http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1786-1800/madison-speech-proposing-the-bill-of-rights-june-8-1789.php (March 4, 2016). ↵

- Constitution Society, “To the Citizens of the State of New-York,” http://www.constitution.org/afp/brutus02.htm (March 4, 2016). ↵

- Barron v. Baltimore , 32 U.S. 243 (1833). ↵

- Saenz v. Roe , 526 U.S. 489 (1999). ↵

- McDonald v. Chicago , 561 U.S. 742 (2010). ↵

- Sherbert v. Verner , 374 U.S. 398 (1963). ↵

- Near v. Minnesota , 283 U.S. 697 (1931). ↵

American Government Copyright © 2016 by cnxamgov is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Constitutional Convention

Civil liberties and the Bill of Rights

The fourteenth amendment, the constitution as a living document.

- List of amendments to the U.S. Constitution

- What did James Madison accomplish?

- What was Alexander Hamilton’s early life like?

- Why is Alexander Hamilton famous?

- What was Benjamin Franklin’s early life like?

- What did Benjamin Franklin do?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Social Science LibreTexts - The Constitution of the United States

- The White House - The Constitution

- Bill of Rights Institute - Constitution of the United States of America (1787)

- HistoryNet - The Conventional, and Unconventional, U.S. Constitution

- United States Senate - Constitution of the United States

- National Archives - The Constitution of the United States

- United States Constitution - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- United States Constitution - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The federal government is obliged by many constitutional provisions to respect the individual citizen’s basic rights. Some civil liberties were specified in the original document, notably in the provisions guaranteeing the writ of habeas corpus and trial by jury in criminal cases (Article III, Section 2) and forbidding bills of attainder and ex post facto laws (Article I, Section 9). But the most significant limitations to government’s power over the individual were added in 1791 in the Bill of Rights. The Constitution’s First Amendment guarantees the rights of conscience , such as freedom of religion , speech , and the press , and the right of peaceful assembly and petition . Other guarantees in the Bill of Rights require fair procedures for persons accused of a crime—such as protection against unreasonable search and seizure , compulsory self-incrimination , double jeopardy , and excessive bail —and guarantees of a speedy and public trial by a local, impartial jury before an impartial judge and representation by counsel . Rights of private property are also guaranteed. Although the Bill of Rights is a broad expression of individual civil liberties, the ambiguous wording of many of its provisions—such as the Second Amendment ’s right “to keep and bear arms” and the Eighth Amendment ’s prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishments”—has been a source of constitutional controversy and intense political debate. Further, the rights guaranteed are not absolute, and there has been considerable disagreement about the extent to which they limit governmental authority. The Bill of Rights originally protected citizens only from the national government. For example, although the Constitution prohibited the establishment of an official religion at the national level, the official state-supported religion of Massachusetts was Congregationalism until 1833. Thus, individual citizens had to look to state constitutions for protection of their rights against state governments.

Recent News

After the American Civil War , three new constitutional amendments were adopted: the Thirteenth (1865), which abolished slavery; the Fourteenth (1868), which granted citizenship to those who had been enslaved; and the Fifteenth (1870), which guaranteed formerly enslaved men the right to vote . The Fourteenth Amendment placed an important federal limitation on the states by forbidding them to deny to any person “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” and guaranteeing every person within a state’s jurisdiction “the equal protection of its laws.” Later interpretations by the Supreme Court in the 20th century gave these two clauses added significance. In Gitlow v. New York (1925), the due process clause was interpreted by the Supreme Court to broaden the applicability of the Bill of Rights’ protection of speech to the states, holding both levels of government to the same constitutional standard. During subsequent decades, the Supreme Court selectively applied the due process clause to protect from state infringement other rights and liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights, a process known as “selective incorporation.” Those rights and liberties included freedom of religion and of the press and the right to a fair trial, including the right to an impartial judge and to the assistance of counsel. Most controversial were the Supreme Court’s use of the due process clause to ground an implicit right of privacy in Roe v. Wade (1973), which led to the nationwide legalization of abortion , and its selective incorporation of the Second Amendment’s right to “keep and bear Arms” in McDonald v. Chicago (2010).

The Supreme Court applied the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), in which it ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. In the 1960s and ’70s the equal protection clause was used by the Supreme Court to extend protections to other areas, including zoning laws, voting rights , and gender discrimination . The broad interpretation of this clause has also caused considerable controversy.

Twenty-seven amendments have been added to the Constitution since 1789. In addition to those mentioned above, other far-reaching amendments include the Sixteenth (1913), which allowed Congress to impose an income tax ; the Seventeenth (1913), which provided for direct election of senators; the Nineteenth (1920), which mandated women’s suffrage ; and the Twenty-sixth (1971), which granted suffrage to citizens 18 years of age and older.

In more than two centuries of operation, the United States Constitution has proved itself a dynamic document. It has served as a model for other countries, its provisions being widely imitated in national constitutions throughout the world. Although the Constitution’s brevity and ambiguity have sometimes led to serious disputes about its meaning, they also have made it adaptable to changing historical circumstances and ensured its relevance in ages far removed from the one in which it was written.

10. Civil Liberties and Civil Rights

"It is a fair summary of constitutional history that the landmarks of our liberties have often been forged in cases involving not very nice people." - Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter

Each of these people made sensational headline news as the center of one of many national civil liberties disputes in the late 20th century. They became involved in the legal process because of behavior that violated a law, and almost certainly, none of them intended to become famous. More important than the headlines they made, however, is the role they played in establishing important principles that define the many civil liberties and civil rights that Americans enjoy today.

Liberties or Rights?

What is the difference between a liberty and a right? Both words appear in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. The distinction between the two has always been blurred, and today the concepts are often used interchangeably. However, they do refer to different kinds of guaranteed protections.

Civil liberties are protections against government actions. For example, the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights guarantees citizens the right to practice whatever religion they please. Government, then, cannot interfere in an individual's freedom of worship. Amendment I gives the individual "liberty" from the actions of the government.

Civil rights, in contrast, refer to positive actions of government should take to create equal conditions for all Americans. The term "civil rights" is often associated with the protection of minority groups, such as African Americans, Hispanics, and women. The government counterbalances the "majority rule" tendency in a democracy that often finds minorities outvoted.

Right vs. Right

Most Americans think of civil rights and liberties as principles that protect freedoms all the time. However, the truth is that rights listed in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights are usually competing rights. Most civil liberties and rights court cases involve the plaintiff's right vs. another right that the defendant claims has been violated.

For example, in 1971, the New York Times published the "Pentagon Papers" that revealed some negative actions of the government during the Vietnam War. The government sued the newspaper, claiming that the reports endangered national security. The New York Times countered with the argument that the public had the right to know and that its freedom of the press should be upheld. So, the situation was national security v. freedom of the press. A tough call, but the Court chose to uphold the rights of the press.

The Bill of Rights and 14th Amendment

The overwhelming majority of court decisions that define American civil liberties are based on the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments added to the Constitution in 1791. Civil liberties protected in the Bill of Rights may be divided into two broad areas: freedoms and rights guaranteed in the First Amendment (religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition) and liberties and rights associated with crime and due process. Civil rights are also protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects violation of rights and liberties by the state governments.

14th Amendment

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each state, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the executive and judicial officers of a state, or the members of the legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such state, being twenty-one years of age [Changed by the 26th Amendment], and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such state.

Section 4. The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any state shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Protection of civil liberties and civil rights is basic to American political values, but the process is far from easy. Protecting one person's right may involve violating those of another. How far should the government go to take "positive action" to protect minorities? The answers often come from individuals who brush most closely with the law, whose cases help to continually redefine American civil liberties and rights.

Report broken link

If you like our content, please share it on social media!

Copyright ©2008-2022 ushistory.org , owned by the Independence Hall Association in Philadelphia, founded 1942.

THE TEXT ON THIS PAGE IS NOT PUBLIC DOMAIN AND HAS NOT BEEN SHARED VIA A CC LICENCE. UNAUTHORIZED REPUBLICATION IS A COPYRIGHT VIOLATION Content Usage Permissions

The notion that humans have natural, inalienable rights is the foundation of liberal democracies. Political philosophers – from John Locke to John Stuart Mill to John Rawls – argue that the foundation of the justice of the state is its respect for and protection of civil liberties, such as due process, freedom of speech, and right to privacy. In fact, civil liberties are so fundamental that some consider them as “sacred,” and not to be subject to comparison or trade-offs.

However, when societies are faced with major crises, the trade-offs between individual civil liberties and societal well-being become acute and inevitable. On the one hand, the state’s ability to weather the crises often hinges on mobilizing resources and imposing restrictions. On the other hand, as Friedrich Hayek puts it, “‘Emergencies’ have always been the pretext on which the safeguards of individual liberty have been eroded.” Crises may become the excuse for permanent erosion of civil liberties and even a backsliding of civil democracies.

As the world confronts the global health threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, what are citizens willing to sacrifice and what are they steadfast in supporting no matter what the circumstance? How do citizens’ views vary across countries and across demographic groups within a country? How do such views change over time in relation to the evolution of the pandemic? Given the scale of the pandemic and the extraordinary measures adopted by governments to curtail it, the COVID-19 crisis provides a unique and tragic opportunity to understand how citizens view the trade-offs between civil liberties and improved public health conditions.

While COVID-19 represents one of the largest and in many dimensions unprecedented crises in recent history, the debate about trading-off civil liberties during crises has been age-old. Similar discussions have repeatedly arisen in the past: for example, after the terrorist attacks in 2001 and the US government’s surveillance of the population; after many devastating natural disasters when various governments move to restrict freedom; and after the Great Influenza in 1918 when many states imposed bans on public gatherings and enforced face masks in public space – much like what we are witnessing today, more than a century later (see Figures 1 and 2).

In order to study how citizens view the trade-offs between civil liberties and improved public health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, my collaborators and I administered a large-scale representative survey during the past 7 months to more than 400,000 people in 15 countries – Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Singapore, Spain, South Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. By focusing directly on citizens’ evolving attitudes toward public-health policies and civil liberties, we can see how people navigate the trade-offs brought on by the pandemic, as well as the factors that shape public preferences.

Several conclusions emerge from the study. First, a large fraction of people around the world reported being willing to sacrifice their own rights and freedoms in order to improve public health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, about 80% of respondents were willing to sacrifice at least some of their own rights in times of crisis, and citizens from the countries surveyed ranked the importance of core civil liberties similarly. For example, people tend to be least willing to give up rights to privacy or cede power to a central figure, and most willing to endure personal restrictions or significant economic losses.

However, the differences between countries are substantial (see Figure 3). For example, a mere 5% of respondents in China expressed an unwillingness to sacrifice any of their own rights during times of crisis, whereas four times as many respondents in the US did. Moreover, almost half of US respondents said they would not give any ground on freedom of the press, compared to under 5% of respondents in China. The citizens of Japan and the United States, for instance, tend to be among the least willing to sacrifice civil liberties in exchange for improved public health conditions. Conversely, the citizens of China and India seem to be among the most willing to. EU citizens tend to fall somewhere in between.

We also find that, in democratic societies, individuals who have stronger connections to countries that historically did not provide extensive protections of civil liberties are less willing to sacrifice their own rights and freedom for the sake of public health. Specifically, we find that individuals who live in regions that belonged to East Germany before reunification, and individuals who have relatives from North Korea reported being less willing to give up their rights than their co-national counterparts.

Second, we document a strong and robust pattern of individuals with greater exposure to health risks exhibiting a stronger willingness to give up civil liberties in the name of public health. Citizens more prone to COVID-19-related health complications and residing in COVID-19 hotspots are more willing to sacrifice individual rights and freedoms than are those who have a lower risk. Exposure to COVID-19 risks is associated with greater acceptance of policies to relax privacy protections, greater willingness to suspend democratic procedures and to delegate decision-making to experts, and greater tolerance of policies that curtail economic activity and mobility.

Third, we find that citizens’ willingness to sacrifice civil liberties reflects more than just health concerns. People with less education and weaker attachments to the labor force, or (in the case of the US) who are members of racial and ethnic minorities, are less willing to trade off their rights than are other groups, even in the face of heightened health risks. Perhaps being able to accept restrictions on civil liberties is a “luxury” that members of these groups, who may have a long history of exclusion and abuse, cannot afford, so they view any such restrictions as a threat to their lives and livelihoods. It also is possible that those who are more economically advantaged already have their interests well represented by policymakers, and don’t necessarily have to rely on free speech and assembly, much less worry about state surveillance.

Finally, we find that in most countries, people’s willingness to give up civil liberties in exchange for improved public health conditions closely tracks the extent to which they are worried about the pandemic. As shown in Figure 4, between March and mid-June 2020, people became less worried about the risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, and their willingness to sacrifice their rights decreased. After a plateau period in the later summer, worries picked up again and so did people’s willingness to sacrifice civil liberties for the sake of public health.

This study paints a complicated picture of how citizens trade-off civil liberties during major crises. While many do not consider civil liberties as “sacred,” their willingness to sacrifice rights and freedom during crises is shaped by different exposure to the health risks, diverse socioeconomic background, and distinct perceptions of the potential long-term erosion of civil liberties.

The policy responses adopted by governments, especially democratic ones, should be responsive to the preferences of the citizenry. The extent to which citizens comply with policies enacted in times of crises likely depends on whether they agree with the restrictions imposed by the policies, which could ultimately determine the efficacy of these policies against the pandemic. Moreover, providing safeguards that ensure restrictions are lifted once the crisis subsides would be instrumental in citizens’ willingness to sacrifice rights and freedom during the crisis, and critical to the protection of the core values, rights and freedom that humanity fights for and cherishes dearly.

3 November 2020

| All content © 2024 |

National Government, Crisis, and Civil Liberties

What is the balance

Lesson Components

Guiding Questions

- How do we balance the security of the nation with protections of individual liberties?

- How much power should the federal government have over an individual’s civil liberties?

- Students will define civil liberties.

- Students will explain the limits of individual freedoms.

- Students will explain the original intention of the Bill of Rights.

- Students will analyze the balance that is needed in a federal republic between individual freedoms and the security of the country.

Expand Materials Materials

Educator Resources

- Handout B: A Proclamation Answer Key

- Handout D: Case Briefing Sheet Answer Key

- Handout G: The History of Civil Liberty Laws Answer Key

Student Handouts

- National Government, Crisis, and Civil Liberties Essay

Handout A: Abraham Lincoln and Habeas Corpus

- Handout B: A Proclamation

Handout C: Milligan and the Constitution

Handout d: case briefing sheet.

- Handout E: The Ruling

- Handout F: Civil Liberty Laws

- Handout G: The History of Civil Liberty Laws Table

Expand Key Terms Key Terms

- Constitution

- habeas corpus

- military tribunal

- civil liberties

- Bill of Rights

- civilian court

- Amendment VI

- speedy and public trial

- Article I Sections 8 & 9

- Article II Sections 2 & 3

Expand More Information More Information

Following this activity it would be helpful for students to learn of other more recent examples of the President’s need to balance national security with individual freedoms. One example is Security, Liberty, and the USA PATRIOT Act .

Expand Prework Prework

Have students read the National Government, Crisis, and Civil Liberties Essay prior to class time.

Basic understanding of civil liberties and the bill of rights is required for this activity. If more context than the introductory essay is needed, students may benefit from one or more of the following:

- https://billofrightsinstitute.org/webinars/2021-ap-government-prep-with-paul-sargent-5-reviewing-civil-liberties

- https://billofrightsinstitute.org/webinars/2021-ap-government-skills-with-john-burkowski-8-unit-3-civil-liberties-civil-rights-digital-exam

- https://billofrightsinstitute.org/webinars/ap-government-prep-episode-7-civil-liberties

Other resources

- https://billofrightsinstitute.org/games/life-without-the-bill-of-rights

Expand Warmup Warmup

Write this well-known quote on the board, but do not provide the source or date.

“[T]hose who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety” (Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania Assembly: Reply to the Governor, November 11, 1755).

Ask for student responses to the statement: agree/disagree/why. Share source of the quote, and tell students that tension between liberty and security is a recurring feature of U.S. history.

Expand Activities Activities

Have students read Handout A: Abraham Lincoln and Habeas Corpus . Display Handout B: A Proclamation . Point out the questions, and have students listen for the answers as you read the Proclamation aloud. Then go over the answers as a large group. Point out to students that in 1861, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus in some areas. The 1862 suspension of habeas corpus expanded to cover the entire nation.

Preparation for trial role-play: Tell students they will now simulate a trial of Mr. Milligan. Distribute Handout C: Milligan and the Constitution . Read aloud the scenario of Mr. Milligan, who has been sentenced to death for disloyalty by a military court. Divide the class into groups of appropriate size for: attorneys for Mr. Milligan, attorneys for the US, and the Justices of Supreme Court. Give each group a copy of Handout D: Case Briefing Sheet . Have groups complete Handout D using Handouts A , B , and C .

The trial: With about twenty minutes remaining, allow attorneys for the government to make their case, followed by attorneys from Mr. Milligan. The Supreme Court members should then deliberate and announce their verdict. Tell students that they were debating an actual Supreme Court case from 1866. Using Handout E: The Ruling , explain the information and ask students if they agree with the Court. Was Lincoln’s action constitutional? Ask students how they would assess Lincoln’s attempt to balance the strength of the government with the liberties of its people?

Break students into four groups and have each group read one of the policies on Handout F: Civil Liberty Laws . After they finish reading, they should do some background research to complete the graphic organizer on Handout G: The History of Civil Liberty Laws .

After each group has completed their section of Handout G , hold a class discussion about the historical implications of each of the policies and discuss how they affected civil liberties.

Expand Wrap Up Wrap Up

Students discuss and write a reflection on the balance between civil liberties and security as portrayed in this example. How do we know when we’ve gotten this issue right?

Expand Homework Homework

Students conduct research into another example of the tensions between security and individual freedom during a time of crisis in this nation. Depending upon the age and class, instructor could provide a list of examples and have students each pick one to research for homework. Students would write up their findings and share them with the class the next day.

Expand Extensions Extensions

Students research political cartoons exhibiting this tension between rights and liberties. Further investigation into the Bill of Rights and selective incorporation. Students explore how the federal government has intervened in state laws to prevent infringement of individual liberties.

Essay: National Government, Crisis, and Civil Liberties

Primary source: a proclamation – abraham lincoln, 1862, handout e: the ruling of ex parte milligan (1866), primary source: civil liberty laws, handout g: the history of civil liberty laws.

Next Lesson

State and Local Government

Related resources.

Civil Liberties and Coronavirus

The balancing of liberty and security is difficult, particularly in times of crisis. During the COVID-19 pandemic, both national and state governments across the country have exercised expansive powers to enact policies in an effort to slow the spread of the virus.

2021 AP Government Prep with Paul Sargent #5 | Reviewing Civil Liberties

Session 5: Civil Liberties This session investigates the history of civil liberties in the United States. Special attention is on the important Supreme Court cases that outlined modern civil liberties and the process of selective incorporation that applied the Bill of Rights to state governments.

2021 AP Government Skills with John Burkowski #8 | Unit 3: Civil Liberties & Civil Rights (Digital Exam)

In this episode, we review strategies in developing skills to best apply relevant content related to the interpretation, expansion, and limitation of individual freedoms by the various institutions of the American political system, particularly through landmark Supreme Court decisions.

2020 AP Government Prep Episode #7 | Civil Liberties

Session 7: Civil Liberties This session investigates the history of civil liberties in the United States. Special attention is on the important Supreme Court cases that outlined modern civil liberties and the process of selective incorporation that applied the Bill of Rights to state governments. The process was utilized significantly in working to obtain civil liberties specifically through the Due Process Clause and Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Civil Liberties and Law in the Era of Surveillance

- November 13, 2014

- Marguerite Rigoglioso

- Comments ( 1 )

- Fall 2014 – Issue 91

- Cover Story

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share by Email

It may no longer be an exaggeration to say that big brother is watching . When Edward Snowden leaked classified government documents last year, many were surprised to learn just how much access the National Security Agency (NSA) has to the personal email and phone records of ordinary citizens. Those revelations about the scope and extent of surveillance by American intelligence agencies have prompted a national debate about civil liberties in an age of new technology that enables the government to both collect and store vast amounts of personal information about its citizens. The discussion is also surfacing in local communities where technology allows law enforcement to indiscriminately gather information on law-abiding citizens—information that is collected, kept, and shared with little to no oversight, or awareness by the general public.

Today, new technologies are changing the relationship between the citizen and the state, with the government and law enforcement able to access our information and observe our private activities, raising important civil liberties questions. Stanford Law School faculty and alumni are centrally involved in some of the most important questions surrounding this issue—working in key areas where the law is still catching up with technology.

Looming large over the debate is the post-9/11 war on terrorism, which has led to legislation such as the USA Patriot Act, designed to make it easier for the government to collect data that would help combat terrorism. At the same time, the incredible evolution in technology over the past two decades has revolutionized both the tools available to the government for surveillance and those used by individuals to live their lives.

“We’re living in the 21st century, but when it comes to issues concerning information technology, the law is still rooted in the 20th century,” says Anthony Romero, JD ’90, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

In striking a balance between constitutional rights, crime fighting, and national security, the legal doctrines at issue include everything from post-9/11 legislation that has given law enforcement access to electronic records, to constitutional rules governing criminal procedure, to the regulation of surveillance technology equipment by local governments.

Technology at the Local Level

The U.S. is a country of highways and cars, where Americans spend a lot of time behind the wheel. And tracking how we use our cars offers a picture of much more than simply our mode of transportation.

Automatic License Plate Reader/Recognition technology, ALPR, developed in the United Kingdom in the late 1970s, has been in use since the early 1980s as a tool to aid law enforcement agencies in various ways, from tracking stolen cars to identifying criminals. Since its introduction, this technology has become more powerful, mobile, and affordable. Today, more than 70 percent of police departments in the U.S. use some form of ALPR, recording thousands of plate numbers daily with cameras mounted on patrol cars and at key traffic areas such as highway overpasses and street lamps.

While capturing the license plate information, ALPR can also capture photos of the cars—and often the occupants, as well as where they live, where they shop, and where they drive. Put together, this technology can tell a story of how we go about our daily lives.

“Civil liberties problems arise when you engage in the mass tracking of hundreds of millions of Americans, most of whom are completely innocent of any wrongdoing,” says Catherine Crump, JD ’04 (BA ’00), who joined the Berkeley Law faculty this year as an assistant clinical professor of law and associate director of the Samuelson Clinic. She explains that technology is enabling the mass collection of data that can paint a detailed picture of how we interact, gleaning facts about us that the state couldn’t previously collect. As data storage has become more available and affordable, police departments are increasingly sharing gathered data regionally, and with the federal government, creating large databases of citizens, most of them law-abiding.

“No one denies that a license plate reader can be a useful investigative tool and it’s valuable to law enforcement to be able to check to see if a particular vehicle is stolen or associated with a suspected criminal,” says Crump, who was a staff attorney at the ACLU focusing on issues of government surveillance until earlier this year. “The civil liberties objection arises when law enforcement starts to pool massive amounts of location data and keep it for long periods of time based on the mere possibility that it might be useful someday. Because then you have a large database tracking people’s movements and that’s the type of information that can be misused.”

- Watch a CSPAN report on Technology and Police Surveillance

- View a panel discussion about WikiLeaks

And currently, there are few regulations for how the data is used and how long it can be kept.

“There are no generally applicable laws placing limits, there are no federal laws,” she says. “In general it’s up to each state and law enforcement agency to come up with its own rules.”

Crump cites a few states that have introduced legislation for ALPR, including Utah, Maine, and New Hampshire, noting that it is largely a nonpartisan issue.

“It’s an issue where people on the left and right can find common ground between civil libertarian and law enforcement interests because everyone agrees that there are legitimate uses of the technology,” she says. “So the objections are not to the technology, but to certain uses.”

Crump thinks it important for all Americans to carefully consider these issues now, as new technologies are increasingly used by local law enforcement and the federal government.

“We should project forward to a world where it is possible to install a license plate reader on every street lamp,” she says. “And we should start planning for a world where that type of omnipresent surveillance is possible and figure out how we feel about it. And if people agree with my general view that that type of surveillance can be oppressive, it’s time to put rules and regulations in place to ensure that we take advantage of the positive aspects of this technology without suffering an undue loss to our civil liberties.”

Catherine Crump, JD ’04 (BA ’00)

New surveillance capabilities also raise concerns about how powerful investigatory tools typically reserved for investigations of criminal organizations may now be turned against certain communities.

“The government has a particular security interest in Muslim communities in the United States and abroad, yet these communities rarely have the political clout to resist overbroad surveillance,” says Shirin Sinnar , JD ’03, an assistant professor of law at Stanford.

- Watch a CSPAN report on Transportation Security

- Watch Sinnar speak about airport profiling

Sinnar has written about the devastating mistakes made in associating people with terrorist activity in the United States––errors that have resulted from prejudicial attitudes, insufficient oversight, and lopsided incentives to err on the side of security. She has also noted cases in which the pervasive mapping, surveillance, and investigation of Muslim communities have “significantly harmed their ability to practice their faith and express their views.”

Crump offers an example of police surveillance of mosques. She explains that in 2012 as part of a program to gather information on the city’s Muslim community, the New York City Police Department mounted cameras directly outside of city mosques and used license plate-reading technology to record the identities of attendees and the cars they arrived in.

Although some of these practices have since been challenged in court, few have been resolved, Sinnar says. Most are dismissed for lack of standing or because the government invokes a national security-specific “state secrets” privilege, impeding any resolution of the constitutional questions at stake.

Reining in Mass Collection of Personal Data

In 2011, an unnamed telecommunications company received a demand from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to hand over records about a customer (or customers). The demand came in the form of a National Security Letter (NSL), a type of legal demand that doesn’t require a court order and allows federal law enforcement to obtain information from telecommunications and Internet companies about their customers. NSLs have been issued by the government since about 1978, but the USA Patriot Act, passed overwhelmingly by Congress in 2001, greatly expanded their use. Critics have argued that the procedure raises major problems because NSLs lack judicial oversight and are almost always accompanied by a nondisclosure provision that prevents the recipient from revealing that it has received such a letter.

The company, whose name could not be revealed because of that secrecy order, challenged the NSL in court, arguing that both the nondisclosure provision and the limited judicial oversight were unconstitutional.

In March 2013, Judge Susan Illston, JD ’73, a federal district court judge in San Francisco, ruled that the statute authorizing the NSL violates the Constitution. In her decision, In re: National Security Letter , she wrote that even when “no national security concerns exist, thousands of recipients of NSLs are nonetheless prohibited from speaking out about the mere fact of their receipt of the NSL, rendering the statute impermissibly overbroad and not narrowly tailored.” She acknowledged “significant consti tutional and national security issues at stake” and stayed her order to allow an appellate court to weigh in. The case was argued before the Ninth Circuit in October.

The case is one of a number of ongoing challenges to legislation that has expanded the government’s ability to access private data since the 9/11 attacks. Separately, the ACLU filed a lawsuit (now before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals) that challenges the government’s program of collecting phone records of all Americans under the Patriot Act. “It’s the first suit that hasn’t been kicked out because, thanks to Snowden, we can now establish standing—that is, show that the American public has been the subject of surveillance,” says Romero, who has met with Snowden twice in Moscow and is assisting with his legal counsel through the ACLU.

- Read Romero’s Huffington Post article about Edward Snowden

- Watch Romero speak about the ACLU

- Watch Anthony Romero on the Colbert Report

- Watch a symposium presentation with Anthony Romero

Meanwhile, some members of Congress are pushing to revise the Patriot Act in light of recent developments. Under pressure from the public as well as many Internet and telecommunications companies, Congress is considering limiting surveillance with the USA Freedom Act. While the House and Senate passed differing versions of the bill, both versions propose to rein in the collection of data by the NSA and other government agencies. The aim is to increase transparency of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), a federal court established under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) of 1978 to oversee requests for surveillance warrants against suspected foreign agents inside the United States. The FISC’s powers were extended under the Patriot Act to include domestic information collection when relevant to a counterterrorism investigation. The act also calls for narrowing of the requirement that businesses hand over customer data to the government and the creation of an independent constitutional advocate to argue cases before the FISC. So far, the bill is pending.

“The Senate version of the bill goes much farther than the tepid House version in strengthening the system of checks and balances and ensuring greater government transparency, but we still need to look more stringently at the operations of the judicial system and the oversight mechanisms of Congress,” says Romero.

With deadlines approaching, Congress is likely to act. “In June 2015, section 215, the law under which the phone records collection is happening, is set to expire. Congress will have to address the concerns raised by the telephony metadata program before then,” says Laura Donohue, JD ’07, professor of law at Georgetown Law, director of Georgetown’s Center on National Security and the Law, and co-director of the Center on Privacy and Technology.

National Security and Personal Privacy

In designing national security laws, the challenge for policymakers is to strike the right balance, says Jennifer Granick , civil liberties director at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society . “The big-picture issue is how do we protect national security and conduct foreign intelligence without creating a surveillance state,” she says.

- Watch a CIS video on the “surveillance state”

- Watch a video on civil liberties in the post-Snowden era

- Watch Granick speak about NSA surveillance

Referencing the NSA’s program to obtain email and other private communications from Internet companies, she explains that “the government is engaged in a huge ‘dragnet’ in which an immense amount of information is getting sucked in about Americans as well as foreign targets. That raises all kinds of statutory and privacy questions. Is the law appropriate? Is the government collecting and using data lawfully and appropriately? Do we protect the rights of foreigners? When they get information about Americans, what do they do with it?”

“The three branches of the government were asleep at the switch when it came to protecting fundamental freedoms and privacy in the post 9/11 era,” says Romero. “The courts rubber-stamped the overzealous collection of data by the executive branch, and Congress exercised only limited oversight.”

Romero maintains that such acts have challenged not only the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable search and seizures, but also the First Amendment, which prohibits the abridging of free speech and of the practice of religion.

“People who realize they’re being surveilled are less likely to write emails, place phone calls, and express themselves freely if they know they might be caught in government surveillance,” he says. “This will fundamentally change the way we live in our democracy.”

Granick asserts that a key priority should be ending government spying based on secret interpretations of law. “We don’t really know what laws the executive branch is following or how the Fourth Amendment and statutes already on the books are being interpreted. There’s an immense amount of classified information, including court opinions,” she says, referring to secret decisions of the FISC.

The Fight for Internet Freedom — featuring David Drummond, JD ’89 and Google VP

Ivan Fong, JD ’87, former general counsel of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) agrees that data collection has to stay within constitutional limits, while lauding the importance of intelligence in national security investigations. “A certain amount of intelligence collection is, of course, necessary for the president to fulfill his constitutional duties and to act as commander in chief,” he says. “In a number of cases in which I was involved, the intelligence indeed played a significant role in preventing or disrupting actual terrorist threats.”

Fong is also sympathetic to civil liberties concerns. From 2009 to 2012, Fong was responsible for all legal determinations and regulatory policy at DHS. He provided legal counsel to the secretary of homeland security on questions of counterterrorism and national security law and policy and of cybersecurity law and policy. Fong believes current intelligence surveillance can both be lawful and serve our national security interests.

“Such collection should be, consistent with the law, as narrow as possible—in other words, a process known as minimization—and we should search for and embrace any new technological and other means to ensure stronger protection of privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties interests.”

Still, he agrees that courts, legislators, and policymakers “need to carefully articulate the core principles at stake to ensure outdated legal constructs or paradigms are reassessed in view of the new technology.” Fong points to the recent Supreme Court decision requiring police generally to obtain a warrant to search the contents of cell phones seized during an arrest as a good example of a case that updates existing legal doctrine in light of the power of new digital tools.

Riley : Redefining the Limits of Legal Search

That decision [Riley v. California , which the Court decided along with a related case, U.S. v. Wurie ] recognizes that privacy in a digital world may require new rules and “brings the Fourth Amendment into the 21st century,” says Jeffrey Fisher , professor of law at Stanford and co-director of the Supreme Court Litigation Clinic .

- Fisher discusses Riley v. California

- Watch Fisher talk about arguing cases in the Supreme Court

It was Fisher who argued Riley before the Supreme Court in April, supported by the research and brief writing of his clinic students. The clinic represented David Riley, a college student currently serving a prison term in part due to evidence found on his cell phone that linked him to gang activities and a drive-by shooting.

In general, the Fourth Amendment allows police to search items that are found on a person who has been arrested, which could include a cell phone. But until Riley and Wurie, it wasn’t clear whether that right extended to police reading and reviewing data stored on the phone—before first obtaining a warrant.

“We argued that smart phones are categorically different from any other kind of non-digital object that can be found on a person because of the vast quantities of sensitive personal information involved and we argued that they should therefore not be subjected to search without a warrant,” says Fisher. Because the Supreme Court agreed with that argument unanimously, handing down its decision in June, in the future police will be able to seize but not search cell phones until a warrant has been obtained. Riley himself may be entitled to a new trial that excludes the cell phone evidence, which was obtained without a warrant.

The implications of the case could go well beyond the context of law enforcement and cell phones, and Fisher argues it will have implications in the national security context. “The Riley decision essentially rejects the argument that the government is currently using to justify the NSA’s collection of data on individuals, which is that digital data is subject to the same legal rules as analog data,” says Fisher.

The case also resolved a tough question about how to apply long-standing legal standards to new technologies. “This is a game changer, showing that the Court agrees that information gleaned from digital devices can paint a portrait of us that creates privacy considerations that didn’t exist before,” says Fisher.

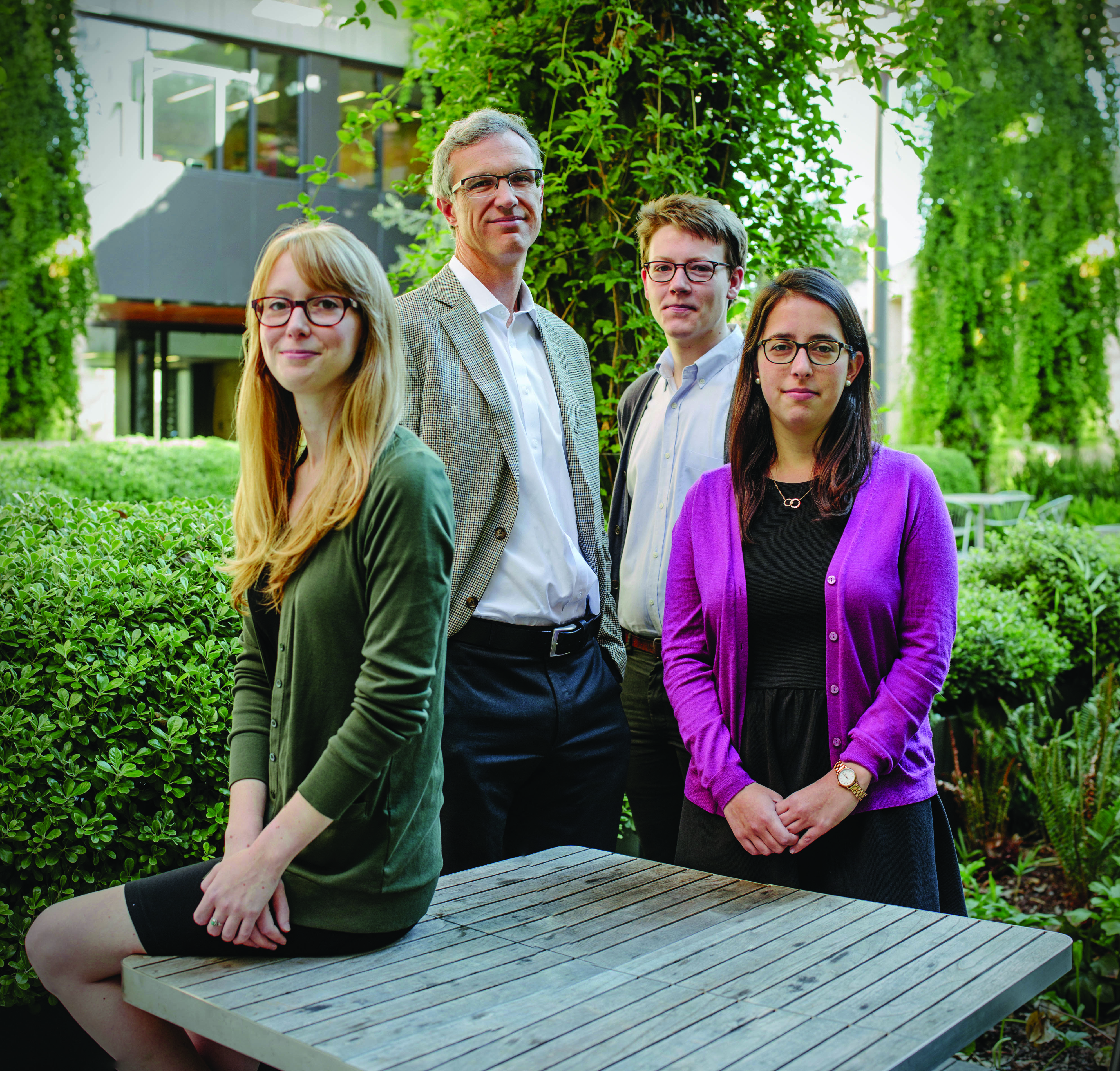

Professor Jeffrey L. Fisherdiscusses the work he did with Stanford Supreme Court Litigation Clinic students preparing for the important digital privacy case. Revisiting Third-Party Privacy Protection

One of the most serious places where the law has gone awry relates to the third-party doctrine, says Jonathan Mayer, JD ’13, a doctoral student in the computer science department who has taught Computer Security and Privacy at Stanford Law School.

According to Robert Weisberg , JD ’79, the Edwin E. Huddleson, Jr. Professor of Law, that legal theory, which evolved in the 1970s, holds that people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in information volunteered to third parties, such as banks, phone companies, and perhaps even email services. Without that expectation of privacy, the government may constitutionally obtain information from third parties without a warrant.

“It’s an anachronistic doctrine, because these days we give all sorts of private information to third parties, including cloud services. That’s the modern way of life, and the law needs to catch up,” says Mayer, whose online Stanford University course Surveillance Law this fall explores how U.S. law facilitates electronic surveillance—but also substantially constrains it.

“Given the changes in technology over the past few decades, we definitely need new laws that revisit the third-party doctrine of Fourth Amendment concerns,” affirms Weisberg.

This past spring, Weisberg guided students in a policy practicum to prepare a background study of legal and policy issues regarding state law enforcement access to user records held by communications companies. The study, done for the California Law Revision Commission, considered civil liberties, public safety, and the scope of federal preemption.

“Our recommendation was that statutes imposing a warrant requirement be established for law enforcement access to user records of cell phone providers, Internet service providers, social media companies, and other mobile and Internet-based communication providers and that they be very specific about what they do and do not allow,” says Weisberg, who is co-director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center.

Such a revision in California statutory law, Weisberg explains, would address some problems, at least at the state level, with the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), a federal regulation regarding the government’s ability to intercept electronic communications and to demand disclosure of stored communications, customer records, and other user data. ECPA has been criticized for failing to sensibly protect communications and consumer records, mainly because the law is so outdated and out of touch with how people share, store, and use information today.

Drones Coming Home

Use of unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones, by the military has increased dramatically as part of the effort to combat terrorism overseas. But use of drones in the U.S., for a variety of purposes, may also be on the rise.

High-altitude drones can hover over cities for long periods of time and record everything that takes place. But they are not widely adopted yet because the FAA has largely prohibited their use due to safety concerns with airplane traffic. But after passage of a provision in the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, drone use in the United States looks likely to increase. The act calls on the FAA to integrate unmanned aircraft by 2015 and to start by relaxing restrictions. Drones are already used to patrol the Mexican border and increasingly by businesses including agriculture. And local law enforcement agencies are now also exploring how they might be applied to crime fighting. Here again, new technology useful to law enforcement is raising questions about surveillance and mass collection of data, with regulations to safeguard the civil liberties of citizens not yet in place.

“Drones’ ability to track people and their movements raises huge privacy concerns,” says Romero. “There’s a serious lack of oversight on how they are being deployed and used, where data is being accessed and stored, and who has access to it.”

And the public seems to agree. Crump offers examples of two cities that have purchased drones but have then backtracked: Seattle and San Jose. “When the purchase of drones becam e public, there was an uproar, with residents raising privacy concerns,” she says. In each case the program was shut down. “I think the idea of unmanned airborne vehicles hovering over people’s backyards and peering into their windows makes people deeply uncomfortable. Drones challenge people’s notions of privacy in a way that few other technologies have.”

A key concern with the introduction of this new surveillance technology is the lack of public review and consultation. “I think this raises important questions about the democratic process,” says Crump. “It’s what is known as ‘policymaking by procurement.’ Police departments simply acquire this equipment, often with funding from the federal government. And then they use it and it takes months or years for local government and the public at large to even learn about it.”

One exception—now—is Seattle. The city council passed an ordinance last year requiring the police department to first notify the council about surveillance purchases and to come forward with a proposal about how the information collected will be used.

Correcting the balance among social controls, governmental responsibilities for security, and individual liberty will require the public, Congress, and the courts understanding and navigating a maze of practices and policies, says Granick. “Over-classification, secret law, and intelligence jargon are getting in our way,” she says.

In reflecting on the secrecy regarding surveillance law and lack of robust oversight, Donohue observes, “The founders of the Constitution understood very deeply that not only must the government control the governed—but we must ensure that the government controls itself. Concentration of power in the hands of the few is the very definition of tyranny that the founders held—and that’s what we want to protect against, as we face issues of how government surveillance is being conducted in theglobal digital age.” SL

1 Response to “ Civil Liberties and Law in the Era of Surveillance ”

Maureen coffey.

“Can the law keep up with technology?” Yes and no. It was actually never the law (in my opinion) that could not keep up with technology, it was always a problem of detection and hence enforcement. This battle between crime investigation and enforcement never lacked legal framework. Poisoning (except by kings …) was always a crime, yet not all poisons were detectable. The invasion of privacy is a crime, but the means to do it are fast moving beyond enforceable detection. The more technology advances and no tangible damage can be seen (no broken windows, no finger prints, no “losses” – i.e. all passwords are “still there”) the less can law enforcement do about it. Once nano technology and quantum computing are advanced enough, we may not even know of any “intrusions” nor will the perpetrators themselves know (!) that in turn THEIR perimeters have been breached. Which may lead to interesting avoidance techniques by individualistic individuals that remind one of Amish lifestyles …

Comments are closed.

Civil Rights and Civil Liberties

Differences.