- Partnership for Public Service

- Best Places to Work

- Center for Presidential Transition

- Go Government

- Service to America Medals

- Overview and Strategy

- Board and History

- Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- Work with Us

- Our Supporters

- Our Solutions

- Customer Experience

- Employee Engagement

- Innovation and Technology Modernization

- Leadership and Collaboration

- Presidential Transition

- Rebuilding Trust in Government

- Recognition

- Performance Measures

- Agency Performance Dashboard

- Best Places to Work in the Federal Government®

- Fed Figures

- Leadership 360 Assessment

- Political Appointee Tracker

- Trust in Government Dashboard

- Public Service Leadership Institute®

- Public Service Leadership Model

- Leadership Training

- Leadership Coaching

- Read, Watch and Listen

- Latest Releases

- Search this site

Case Study: Commitment to Public Good

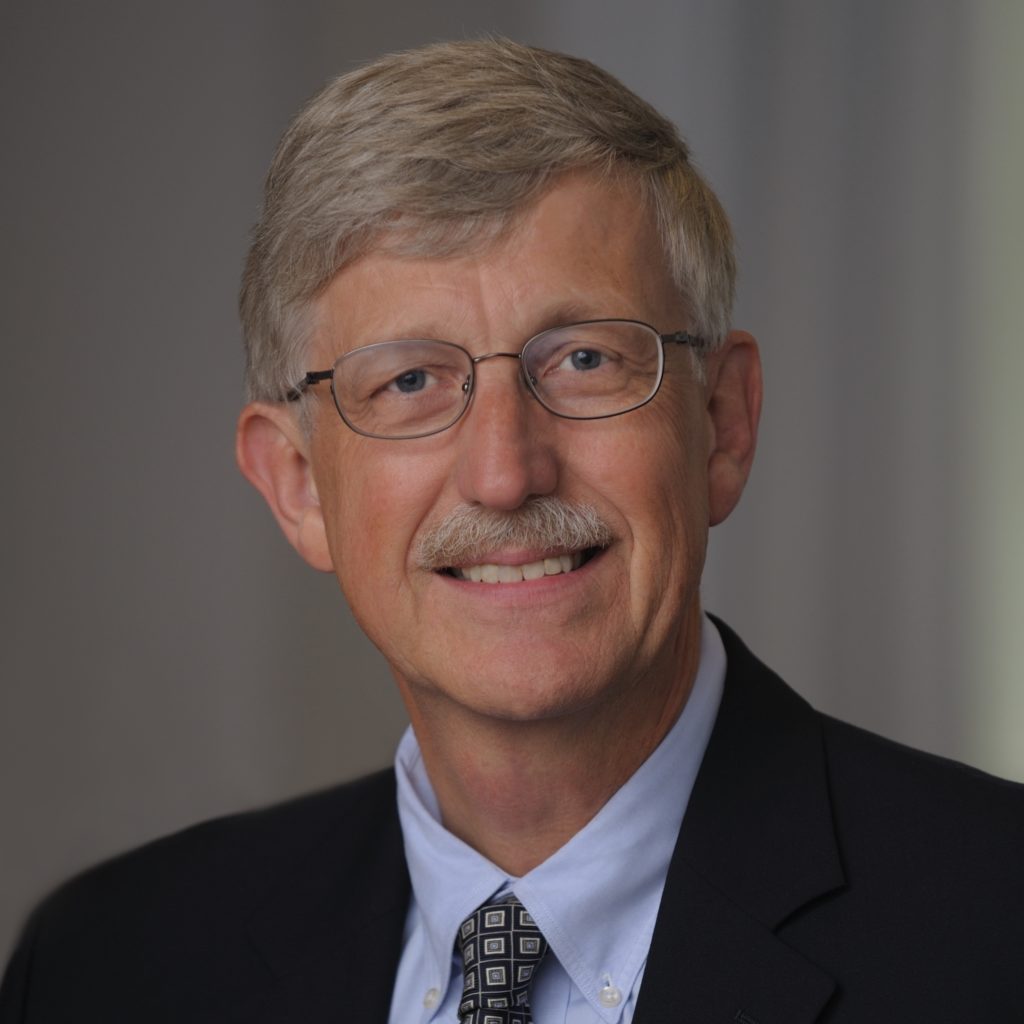

Francis collins: a commitment to public good, public health and public service leadership .

In the 1980s, a young scientist at the University of Michigan was working to identify the gene that causes cystic fibrosis, an inherited disease that researchers had been investigating for years.

Hitting roadblock after roadblock, the scientist was faced with a choice: go it alone and hope eventually to take credit for a discovery—or join forces with others competing for the same recognition.

He chose the latter, pitching a collaborative effort with Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Combining their labs, Tsui and the scientist identified the gene two years later, a landmark discovery that laid the groundwork for future advancements in the treatment of cystic fibrosis and marked one of the first times the genetic basis for an inherited disease had been found.

That scientist was none other than Dr. Francis Collins, one of the nation’s foremost public servants who has left an indelible mark on global medicine in roles ranging from leader of the Human Genome Project to director of the National Institutes of Health to science advisor to the president.

Collins’ work on cystic fibrosis foreshadowed his approach to solving other pressing health challenges: a willingness to collaborate and engage others ; a strong self-awareness with a unique blend of academic and emotional intelligence; a desire to lead change by taking calculated risks; and a steadfast focus on achieving results for individual patients.

Throughout his four-decade career, Collins has leveraged all of these leadership competencies to serve the public good and improve the well-being of current and future generations worldwide.

“I did not enter government as a public servant to add more entries to my CV about a committee I served on or a project I led. I became a public servant to give myself in every way that I can to advance the cause of human health for the benefit of humanity,” Collins said.

Commitment to Public Good

For federal leaders to achieve their agencies’ expansive missions that promote the general welfare of the American people, they need a deep-rooted service orientation and commitment to the public good.

“The path of least resistance”

The irony is that Collins almost didn’t make the jump from academic medicine to public service.

Content with leaving his mark as a professor of internal medicine and human genetics at the University of Michigan, he initially balked at the opportunity to lead the Human Genome Project—a sweeping initiative that aimed to map and sequence all the genes of the human race—when offered the role by former NIH Director Bernadine Healy.

At the time, Collins had only run research labs and found the prospect of managing the “largest big science project ever in biology and medicine” daunting.

Still, he found himself uneasy about declining Healy’s offer, wary that he would later regret the decision to pass on such a unique public service opportunity.

“What worried me was that I was taking the path of least resistance by staying at Michigan and potentially passing up something that would allow me to make a much greater contribution to the country, to the world and to human health,” he said. Three months after telling Dr. Healy “no,” he said “yes.”

From the story: How did Dr. Collins’ background prepare him for a career in public service?

For reflection: What contribution to the country and the world do you make in your public service?

For action: In what ways can you forego the path of least resistance in your public service leadership?

Engaging Others

When Collins began work on the Human Genome Project, he faced the management challenge of a lifetime: the need to recruit thousands of scientists in both the U.S. and overseas, build consensus on goals and standards for their work, and set a timetable for delivering findings and results.

“I floundered quite a bit for the first few years trying to figure out how to organize this effort,” he said.

Collins overcame these challenges by employing the same strategy he used to make a breakthrough on cystic fibrosis—he practiced an egoless and inclusive leadership style that prioritized collaboration and relationship-building to bring some of the world’s best and brightest scientists on board and propel the project.

Collins said a major key was respecting others’ expertise and being self-assured enough to “give them the permission to shine and to tell me when I was wrong.”

“It would have been harmful as a leader to send a message that everybody has to just do what I say,” he said.

Ultimately, more than 2,000 scientists working in six countries mapped the full genetic blueprint for a human being, identifying over 20,000 genes and sequencing 92% of the human genome in 2003. The work continues to provide researchers and health care providers with a wealth of new information to diagnose, treat, prevent and cure diseases associated with certain genes.

For Collins, the key lesson is that engaging others to meet common goals often outweighs the benefits of taking sole credit for a scientific discovery.

“Rather than say, ‘I’m the one who did it all by myself,’ I got to build relationships and experience science in a much more inspired way. Pretty much everything I’ve done ever since has involved looking for partners and for people who had the skills and visions to make things happen that otherwise would take a really long time,” he said.

Collins incorporated those same views into his twelve years as NIH director. Indeed, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Collins tapped into relationships he had built over the years with research and development leaders as well as the heads of major pharmaceutical companies to launch Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines , a public-private partnership aimed at developing promising coronavirus treatments and vaccines.

Collins called the group “the most amazing partnership I’ve ever been part of” and a core driver of the federal efforts to develop safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite the demands of the pandemic—with staff working around-the-clock to develop new tests, treatments and vaccines, and Collins reportedly working 100-hour weeks at times—employee satisfaction and morale at the NIH held steady.

According to the 2020 Best Places to Work in the Federal Government ® rankings, the agency placed 63rd out of 411 agency subcomponents, with its highest mark coming in the “Effective Leadership: Senior Leaders” category.

During his tenure, the NIH also had nearly 30 finalists—12 of whom were winners—recognized at the Partnership’s annual Service to America Medals ® gala, the nation’s preeminent awards program for federal employees.

Collins attributes some of his leadership successes to self-care and maintaining healthy outlets to decompress. When not leading medical breakthroughs or combatting the pandemic, he can be found playing guitar in his rock ‘n’ roll band or riding bikes with his wife, Diane Baker, a leader in genetics counseling. He also stayed centered and grounded through his faith, starting most days with prayer and some Bible reading.

Overall, Collins fostered a culture of excellence at the NIH that enabled the agency to face adversity and mount a speedy and effective response to the pandemic.

“I will not forget being told, as the results were being unblinded for the phase three trial for the COVID-19 vaccine, that it was 95% effective. It was just like such an answer to prayer,” he said.

From the story: How did Collins’ mindset on building partnerships serve his goals and/or ambitions?

For reflection: What are your patterns for shining a light on others’ work and giving credit?

For action: How might you better achieve your organizational goals through cross-boundary partnerships and empowering those around you?

Becoming Self-Aware

The genome project also reinforced Collins’ sensitivity to diversity, equity and inclusion, and demonstrated his willingness to confront his own privilege—both as a white male and as a member of a medical establishment that has not always earned the trust of underserved communities.

Collins said the project illustrated that people with different skin color are at “the DNA level 99.9% the same” and underlined his commitment to reducing health care disparities—something he roots in the “long thread of 400 years of structural racism in our society.”

During the pandemic and under Collins’ leadership, the NIH prioritized this issue, supporting new federal programs to increase testing and participation in COVID-19 vaccine trials in underserved communities across the country. These efforts were recognized at the Partnership’s 2021 Service to America Medals ® program.

“I grew up not with a lot of financial resources, but I have had experiences as a white male of having doors open that would not necessarily have been opened to others,” he said.

Collins also was a strong supporter of providing leadership opportunities for women in biomedical research. As NIH director, he hired 11 women as directors of NIH institutes and centers. And he announced that he would no longer take part in “manels”—panels only populated by men—at scientific meetings, starting a trend that was subsequently adopted by many other leaders.

In 2013, Collins met with the descendants of Henrietta Lacks— a young African American mother, now the subject of a film and best-selling book —whose cancer cells were used by Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1951 to create an immortalized cell line—the HeLa cell line—that has enabled important medical breakthroughs.

For decades, ethical issues clouded these discoveries—information about Lacks’ cells were shared with researchers without her consent; her genetic information was made public; and the medical companies who profited from her cells did not compensate or even thank members of her family.

In 2013, Collins met with Lacks’ family three times over a four-month period to hash out an agreement for sharing DNA information from the cell line. Eventually, they agreed to release information on a case-by-case basis, pending approval from a review committee that includes family members.

“I did a lot of listening to Henrietta’s children and grandchildren about how they felt, and answered their questions about what this would do for science,” he said. “I learned a lot from that interaction about what it means to be African American in the U.S.”

Today he considers those family members as friends and colleagues.

From the story: How did Collins earn trust with Henrietta Lacks’ family and the trust of Americans when it came to progressing science and medicine?

For reflection: Where might your privilege or perspectives get in the way of you improving the lives of underserved communities?

For action: In what ways can you improve the lives of historically marginalized populations through your leadership?

Leading Change

After leading the genome project, Collins became NIH director. In that role, he oversaw a sprawling multibillion dollar organization focused on nearly every aspect of public health in the U.S.

From the get-go, Collins took calculated risks and embraced uncertainty to maximize the agency’s impact.

He prioritized supporting new and emerging projects in addition to more established ones that had already demonstrated proof of concept. Collins admitted that it was risky to fund projects lacking “a lot of preliminary data,” but recognized that NIH’s normal peer review process, while essential, often weeded out more experimental and potentially groundbreaking projects.

“We wanted to support people who weren’t sure their project was going to work, but knew that something really significant would happen if it did,” he said.

He also explored bigger opportunities “that could completely flop” but offered new possibilities in the field of science and medicine.

Using his convening power as NIH director and with support from the Obama administration, Collins brought together leading neuroscientists to develop a large-scale effort to better understand how the brain works called the BRAIN Initiative . Now in its seventh year, the initiative uses innovative technologies to show how individual cells and neural circuits in the brain interact over time and space—knowledge that is critical to treating, preventing and curing brain disorders.

Another “unproven investment” involved trying to build a public health data set to enable better precision medicine—a type of medicine that customizes health solutions based on an individual’s unique genetic and environmental factors.

Today, the All of Us Initiative , has collected electronic medical records, laboratory data— ultimately complete genome sequences—and health behavior information from more than 400,000 research partners across the U.S. to build one of the most diverse health databases in history.

Collins called the project “risky in all kinds of ways,” but believes the benefits of developing new knowledge about managing illness outweigh the costs.

“Advances in health and medicine aren’t going to happen just by waiting,” he said. “My main job as NIH director was to look across the landscape and identify bold new ideas and opportunities to make a difference.”

From the story: What were some of Collins’ reasons for taking risks as NIH director?

For reflection: What gets in the way of risk-taking for you as a public service leader?

For action: How might you instill an innovative mindset across your teams and encourage risk-taking to achieve greater results?

Achieving Results

At the core of Collins’ drive to make these larger advances in medical health lay a steadfast commitment to individual patients and customers. Throughout his career, Collins has considered himself a “physician-scientist” whose research projects “typically begin with a patient interaction.”

“I have found it useful to strive toward large-scale projects, but to also remember that, when it comes down to it, it’s about one person at a time that I’m trying to help,” he said.

This focus on helping patients has enabled Collins to expand the reach of his work.

For example, his lab has worked for decades to determine the cause of and develop treatments for Progeria, a rare genetic disease that causes premature aging in children. Even though the disease impacts just a few hundred children worldwide, seeing its effects on children up close has pushed him to make it a research priority.

“I just couldn’t look away when I saw that disease,” he said. “Nobody had really ever tried to sort it out.”

Thanks to his work, the Food and Drug Administration recently approved the first treatment for Progeria and new advancements in gene-editing are being developed to extend the lifespan of people with the disease.

When times are tough, Collins looks to the patients with whom he has worked for strength and inspiration.

For example, he keeps several reminders in his home office of Sam Berns—a young boy who lost his life Progeria in 2014 and whose parents started the Progeria Research Foundation in 1999.

More recently, Collins busted out his guitar to play music with a 13-year-old NIH patient with sickle cell disease who is also a talented violinist. He said that playing their instruments together in the atrium of the NIH Clinical Center, the largest research hospital in the world, served as a poignant reminder of the human impact of his work.

“What we do in medical research connects us to patients,” he said. “When we’re in a rough spot, we should be reminded and encouraged that this is something that’s really making a difference.”

From the story: How does Collins’ commitment to public good center back on individual people?

For reflection: Consider the people you serve and, where possible, think of an individual person. What difference does your service make in their life?

For action: What can you do to renew your commitment to public good? What inspires you and keeps you driven to succeed in your and your agency’s missions?

Explore our other case studies

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Public Goods

The government plays a significant role in providing goods such as national defence, infrastructure, education, security, and fire and environmental protection almost everywhere. These goods are often referred to as “public goods”. Public goods are of philosophical interest because their provision is, to varying degrees, essential to the smooth functioning of society—economically, politically, and culturally—and because of their close connection to problems concerning the regulation of externalities and the free-rider problem. Without infrastructure and their protection goods cannot be exchanged, votes cannot be cast, and it would be harder to enjoy the fruits of cultural production. There is widespread agreement among political philosophers that some level of education is required for democracy to be effective. Due to their connection to externalities and the free-rider problem, the provision of public goods raises profound economic and ethical issues.

As we will see in Section 1, the economic definition of a public good has little to do with whether these goods are provided by the public or by private enterprises but with certain abstract features that are shared by many different goods, only some of which are regularly produced publicly. The abstract features economists use in their definition depend on technology, values and tastes, making boundaries contested and shifting over time. Section 2 will introduce the notion of an externality, and in Section 3 the standard neoclassical welfare economic analysis of public goods will be examined. Section 4 looks at the private provision of public goods. Section 5 offers a review of recent experimental work on public goods (which challenges the standard analysis to some extent). Section 6, finally, discusses some ethical arguments relevant to the provision of public goods.

1.1 Non-Rivalry and Non-Excludability

1.2 porous boundaries, 1.3 different kinds of public goods, 1.4 examples of public goods, 1.5 an alternative definition, 2. public goods and externalities, 3.1 the public-goods problem, 3.2 responses to the public-goods problem, 4.1 coupling, 4.2 other mechanisms, 5.1 public goods games, 5.2 other kinds of evidence: field studies, observational studies, case studies, 6.1 controversial assumptions in welfare economics, 6.2 the market as a discovery process, 6.3 market norms and other norms, other internet resources, related entries, 1. defining public goods and distinguishing between different kinds of public goods.

Even though Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson is usually credited with having introduced the theory of public goods to modern economics (e.g., in Sandmo 1989), the origins of the idea go back to John Stuart Mill, Ugo Mazzola (an Italian writer on public finance), and the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell (Blaug 1985: 218–9 and 596–7]). Samuelson defined what he called a “collective consumption good” as:

[a good] which all enjoy in common in the sense that each individual’s consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual’s consumption of that good…. (Samuelson 1954: 387)

In the contemporary debate, this feature or characteristic of goods is usually referred to as “non-rivalry”. A good is rivalrous if and only if an individual’s consumption of it diminishes others’ ability to consume it. Bob’s consumption of a grain of rice makes it impossible for Sally to consume the same grain of rice. By contrast, Sally’s enjoyment of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 in no way diminishes Bob’s ability to do the same. Rice is thus rivalrous while music is not. [ 1 ]

A few years after Samuelson, Richard Musgrave introduced an alternative criterion, that of (non-) excludability (Musgrave 1959). As the name suggests, a good is excludable if and only if it is possible to prevent individuals from consuming it, to “draw a fence around it” as it were. Land is thus a good that is considered excludable, while streetlight is not excludable: if Bob pays for a streetlight to be installed, he cannot stop his neighbour Sally from benefitting from it.

In contemporary economics, goods are usually defined as public goods if and only if they are both non-rivalrous and non-excludable (e.g., Varian 1992: 414). Rivalrous and excludable goods are called private goods. National defence is a paradigmatic example of a public good. Not only does Sally’s consumption of national defence not reduce Bob’s consumption; she could not prevent him from consumption if she tried. Food, clothes and flats are paradigmatic examples of private goods.

There are also goods that are rivalrous and non-excludable and goods that are non-rival and excludable. The former are sometimes called “common pool resources” (e.g., V. Ostrom & E. Ostrom 1977, E. Ostrom et al. 1994; E. Ostrom 2003). An example is fish stocks. The latter are sometimes called “club goods” (e.g., Mankiw 2012: 219; see also Buchanan 1965). Examples include watching a movie in a cinema and the services provided by social and religious associations.

Table 1 provides an overview of the different types of goods that have been distinguished so far.

| Private goods (homesteads, bathroom cleaner) | Club goods (Sports clubs, movie theatres) | |

| Common resource goods (fish stocks) | Public goods: local (fire protection), national (national defence), global (climate mitigation measures), partial (parades) |

Table 1: Different kinds of economic goods

The boundaries between these different types of goods are neither sharp nor fixed. For example, whether or not Bob’s enjoyment of a movie in a theatre is affected by Sally’s watching the movie in the same theatre at the same time depends on Bob’s values or tastes as well as details of the context. Sally might sit in front of Bob and partially block his view. Or she might be one of those people who sits right next to you even though fifty other seats are available. Or Bob might be bothered by anyone sitting in the same theatre at the same time, or enjoy watching the movie together with others. Thus, even supposing that Sally doesn’t alter Bob’s viewing of the movie as such, her presence can have a positive or negative effect on Bob’s enjoyment of it. Thus, whether or not a good is rivalrous in consumption depends on many contextual details and not just the nature of the good alone.

The same good can be excludable at one time, but non-excludable at another, or excludable in one society, but non-excludable in another. For example, radio broadcasts used to be a public good because it was not (easily) possible to prevent individuals from tuning in, but this is no longer the case in the digital age. But technology is only part of the story. A particular plot of land—a prime example of a private good—can be protected by building a fence around it. But there is no fence that cannot be overcome. In reality, a fence is more like a signal indicating that the owner prefers to keep others out, or it makes it more costly for them to do so. What matters for the characterisation of land as a private good is that the landowner has the right to stop potential trespassers and that this right will be enforced by the legal system. Of course, which sets of rights are attached to property depends on the norms prevailing in a society. Property rights are never absolute (property in a chain saw gives me the right to use it to cut my own trees but not to cut my neighbour’s trees, much less to use it to hurt anyone), and always the result of past negotiations.

To give a silly example, not everyone enjoys the sight of (particularly, white) socks in sandals. In our society, the sight of socks in sandals is something individuals have to endure because it is considered to be within the rights of the owners of white socks that they can wear them in public, in sandals or in other types of shoes. It is easy, however, to imagine societies that define the rights of sock-owners differently and value the tastes of those who are bothered by the blight of socks in sandals more highly. Indeed, even in modern liberal societies social norms regulate what is decent to wear in public. Since a good’s degree of excludability depends in part on property rights, and what property rights entail may differ between societies and, within societies, may change over time, a good’s excludability may differ between societies and change over time.

Another, related aspect is that the cost of enforcing property rights differs between cases, partly for technological, partly for legal and political reasons. That automobiles are private goods depends on the relatively cheap availability of suitable locks and also on the fact that the government enforces property rights in automobiles. If the price of locks were higher, or the government made it illegal to secure one’s car using a lock, or the government stopped prosecuting theft, automobiles would be “non-excludable” (Demsetz 1964).

A corollary of the non-excludability characteristic is that there are limitations to consumers’ consumption decisions regarding the public good, if it is produced. Individuals might have different preferences for the level of security provided by national defence, but once national defence is in place, they will consume the level that has been produced, not more or less of it. One cannot “opt out” of the consumption of a public good. Similarly, while everyone might like clean air, individuals will differ in their degree of tolerance of pollution. But once “clean air” has been produced, consumers must consume it independently of their preferences.

It has been suggested that the “public” nature of a public good may be an effect of its provision by the public rather than its cause (Cowen 1992: 6 credits unpublished work from 1987 by Boudewijn Bouckaert). If a good is provided by government, private actors have no reason to develop technologies that allow the exclusion of non-paying individuals. Accordingly, public investment in the good thereby makes a good that could be private a public good. Even if this idea is mistaken, it illustrates the fact that the boundary between private and public goods is not fixed because what is technologically possible depends in part on investment in research and development.

The physical characteristics of a good, then, together with the context of its consumption, values, tastes, legal, moral and social norms as well as technological possibilities determine the proper categorisation of a good as a private, common pool, club, or public good.

Distinctions can also be drawn among public goods. Most public goods do not affect all inhabitants of a large community equally. Fire protection services in Lower Manhattan are not consumed by those living in the Bronx, much less by Californians. Public parks benefit those who live in the neighbourhood, playgrounds only those who live in the neighbourhood and have children of a certain age (and indeed they might constitute a public bad for others). Charles Tiebout has developed a theory of local government, after which the term “local public good” was coined (Tiebout 1956, Stiglitz 1982). Other public goods may benefit all of humanity, such as climate change mitigation. We can therefore distinguish local , national , and global public goods (on the latter, see Kaul et al. 2003).

A partial public good is one from whose consumption some individuals can be excluded but not others. Mancur Olson gives the example of a parade that is a public good for those living in tall buildings overlooking the parade route but a private good to those who need to buy a ticket for a seat in the stands along the way (Olson 1971: 14). A full public good, by contrast, is one from whose consumption all individuals can be excluded.

The following are examples of goods that are typically regarded as public goods:

- Security . National defence has already been mentioned as an example. More generally, the ability to live safely and peacefully in a neighbourhood, city, region, or country (for instance, through police and armed forces) is considered a public good because it is difficult to exclude any inhabitant of the protected area from benefitting from the protection and one inhabitant’s enjoyment of protection does not generally diminish other inhabitants’ equal enjoyment.

- Education and science . The public goods character of education and science is somewhat more subtle. It is easily possible to exclude individuals from being schooled, and so “having an MIT engineering degree” is a private good. However, the more educated the general population is, the more individuals benefit from this general education—independently of how much they invest (or the public invests) in their own education—in a manner that is non-excludable and non-rivalrous. A better educated population makes it easier for businesses to thrive, and everybody profits from a thriving economy, not only those who are well-educated. It is difficult to exclude individuals from a thriving economy and a given individual’s benefit is not diminished by anybody else’s benefit. Scientific ideas are also considered to be public goods (Boldrin & Levine 2008). Once an idea (such as a scientific theory) has been created it is difficult to exclude individuals from benefitting (unless the idea is protected by a patent, see below), and individuals’ benefit is non-rivalrous. It is important to distinguish between the idea and its physical manifestation. The idea of a steam engine is a public good, whereas particular steam engines are both excludable and rivalrous.

- Infrastructure . Though infrastructure is often referred to as a public good (e.g., OECD 2016), whether the classification is correct depends on the details of the specific kind of infrastructure and technology. Paradigmatic examples of infrastructure are often not public goods. Roads and motorways are excludable, as the existence of toll roads attests. If the toll for a private road is sufficiently low, it can be rivalrous as well due to congestion. The same can be said about the internet. A traditional lighthouse is more likely to have public-goods character, though depending on the physical nature of the signal it sends, it may well be excludable (Varian 1992: 415). The reason many commentators classify infrastructure as a public good is that it tends to lead to positive externalities. The (close) relationship between public goods and externalities is explained below.

- Environment . Clean air is a paradigmatic good, at least outside. Without massive infringements of an individual's rights it is virtually impossible to exclude him or her from benefitting from clean air. And outside of narrowly enclosed spaces, clean air is non-rival. Similarly with the absence of littering. If I decide not to litter, I cannot easily prevent you from enjoying the clean space, and your enjoyment of it does not reduce anyone else’s.

- Public health . Individuals benefit from a healthy population in a variety of ways. For example, the fewer individuals are infected with a contagious disease, the less likely it is that any given (currently healthy) infects him- or herself. These benefits obtain in a non-excludable and non-rivalrous manner. A healthier population is also more likely to be productive, making public health analogous to education.

Angela Kallhoff has offered an alternative, albeit similar, definition of a public good (Kallhoff 2011: Ch. 2). According to her, a public good is one that satisfies the “basic availability condition” and the “open access condition”. Basic availability is her analogue of non-rivalry. A good satisfies this condition whenever each person benefitting from it has access to the same amount and the same types of benefits. To state the condition in these terms makes explicit that there may exist a level of consumption at which sameness of amount and types of benefit are no longer guaranteed. A single ship’s enjoying the benefits of a lighthouse does not affect another ship’s doing the same but once the sea is congested this may no longer be the case. A lighthouse is a public good because there exists a level at which each person has access to the same amount and the same types of benefits. Open access is Kallhoff’s analogue of non-excludability. It states that

entrance barriers that regulate access to a good are not combined with criteria which define a list of potential beneficiaries and exclude others. (Kallhoff 2011: 43)

Clubs produce services for a specific group of beneficiaries, the club members. In order to profit from a lighthouse, an individual needs a boat and a desire to travel to the coast where the lighthouse is located but there is no pre-specified collective that constitutes the intended beneficiaries of this good.

Externalities are effects of economic transactions on individuals that are not party to the transaction. The paradigm example is pollution: a company produces some good the production process for which is “dirty” in that it affects individuals independently of whether or not they are customers of the company. If such effects are undesired, as in the case of pollution, they are called negative externalities; if they are desired, positive externalities. A paradigmatic example of a positive externality is the pollination created by a honey producer’s bees. Individuals benefit from pollination whether or not they buy honey.

Public goods create positive externalities. Suppose a group of individuals get together and pay some company to produce (analog) radio broadcasts. Individuals who are not party to the transaction can now benefit from the good. Similarly, if a group of citizens get together to clean up a public park, individuals will benefit whether or not they were part of the group of citizen cleaners.

The existence of a public good implies the existence of (positive) externalities, but the reverse is not true. The beekeeper’s bees may pollinate the trees in the neighbouring orchard, thereby increasing its production, but that does not mean that it is impossible to exclude others from this or other benefits or that these benefits are non-rivalrous.

3. The Economics of Public Goods and the Public-Goods Problem

The provision of public goods is often associated with market failure due to the externalities created by the public good. Suppose that in a two-by-two toy economy Bob and Sally decide how much to invest in a discrete public good G such as a radio station. Both have an initial endowment of a private good (which functions as money in this economy). The public good will be produced \((G = 1)\) if the sum of contributions \(g_{\textrm{Bob}}\) plus \(g_{\textrm{Sally}}\) is higher than the production cost c . Thus (Varian 1992: 415):

How much they will contribute will depend on their reservation prices \(r_{\textrm{Bob}}\) and \(r_{\textrm{Sally}},\) i.e., on the maximum amount of the private good each agent is willing to give up for the public good. It is then easy to show that the production of the public good will be a Pareto-improvement if and only if (Varian 1992: 416) [ 2 ] :

that is, if the sum of reservation utilities exceeds the cost of providing the public good. This is analogous to the efficiency condition for a private good, which is efficiently provided whenever an individual’s willingness to pay exceeds the cost of producing it. In case of a public good, since consumption is non-rivalrous, it is enough when the sum total of all reservation prices exceeds the production cost.

In the simple two-by-two case, let us assume that \(r_{\textrm{Bob}} = r_{\textrm{Sally}} = 100\) and that \(c = 150,\) so that the efficiency condition is satisfied. If either Bob or Sally buy the public good, but not both, they would have to be charged the full cost, leading to an outcome of \(-50.\) The not-buying individual will free-ride on the other’s contribution and get 100. If both contribute, each receives a benefit \(100 - 150/2 = 25.\) If neither contributes, the good will not be produced and both end up with zero. The payoffs are displayed in the matrix in Table 2.

| (25; 25) | (−50; 100) | ||

| (100; −50) | (0; 0) | ||

This payoff structure is identical to a Prisoner’s Dilemma and illustrates the free-rider problem. Bob prefers the public good to be produced but since he benefits from it whether or not he contributes, his most preferred alternative is that in which Sally pays for its production and he free rides on her contribution. Sally faces identical payoffs. Therefore, both will choose not to contribute, meaning that the public good will not be produced, even though the alternative outcome in which both contribute would be Pareto superior. A Pareto-superior outcome is one that makes at least one individual better off while making no-one worse off. (Contribute; Contribute) is Pareto-superior to (Don’t contribute; Don’t contribute). (Don’t contribute; Don’t contribute) is the equilibrium strategy (in the sense that no player has a reason to deviate from playing it, given the other player’s move) but at the same time there is an outcome both would prefer if it could be reached, namely, (Contribute; Contribute).

Given this structure of benefits as well as rationality and self-interest of the members of a group, we can expect that free markets will undersupply public goods. As individuals have strong incentives to free ride and the incentive structure is exactly the same for everyone, everyone tries to free ride and the public good will not be produced in consequence. Let us call the apparent inability of the market to provide public goods in a sufficient quantity the problem the “public-goods problem”.

Many economists regard the public-goods problem as a justification for advocating coercive government action (e.g., Sidgwick 1901; Pigou 1920 [1932]; Samuelson 1954). The argument actually goes back to the origins of economics. In Book 5 of the Wealth of Nations , Adam Smith listed three functions of government. “The third and last duty of the sovereign or commonwealth,” Smith says,

is that of erecting or maintaining those public institutions and those public works, which, although they may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society, are, however, of such a nature, that the profit could not repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals, and which it therefore cannot be expected that any individual or small number of individuals should erect or maintain. (1776: Bk 5, ch. 1)

Similarly, in the nineteenth century John Stuart Mill wrote that:

… it is a proper office of government to build and maintain lighthouses, establish buoys, etc. for the security of navigation: for since it is impossible that the ships at sea which are benefited by a lighthouse, should be made to pay a toll on the occasion of its use, no one would build lighthouses from motives of personal interest, unless indemnified and rewarded from a compulsory levy made by the state. (1848 [1963: 968])

However, it is not easy for the government to estimate the demand for a given public good and calculate the appropriate level of taxes. If preferences were observable, the government could charge each citizen according to their marginal benefit (thereby levying so-called “Lindahl taxes”), and an efficient equilibrium (the “Lindahl equilibrium”) would result (Varian 1992: 426; Roberts 1974). But preferences can’t be observed. If they can’t, people have an incentive systematically to understate their reservation prices in the hope that others won’t do the same so they can free-ride on others’ tax contributions. If everyone does that, the public good doesn’t get funded publicly.

Leif Johansen has argued that the free-riding argument is less compelling than it appears (Johansen 1977). On the one hand, there is little evidence that people systematically misstate their preferences in elections. On the other hand, public goods are produced at rates that are much higher than would be suggested by the free-rider theory, which assumes that utility is strictly increasing in private consumption. The empirical evidence on these questions will be reviewed in Section 5 of this entry.

There are mechanisms that encourage individuals to reveal their true valuations of the public good. One is the so-called Groves-Clarke mechanism (after Groves 1973 and Clarke 1971). Here each individual submits a bid, which may be positive or negative, and which may or may not reflect the individual’s true value of the public good (i.e., the reservation price minus the cost). The public good is provided if and only if the sum of bids is at least zero. Apart from the public good, each individual receives a “side payment” calculated as the sum of all other individuals’ bids (which may also be negative, i.e., a tax).

No individual has an incentive to misrepresent his or her true values under the Groves-Clarke mechanism. Suppose we change the valuations in the above example so that the public good is now worth −24 to Bob (by adjusting his reservation price to 51). It should still be produced as the sum of valuations remains positive (alternatively, the sum of Bob’s and Sally’s reservation prices remains above the cost of producing the public good). Bob does not have an incentive to misrepresent his valuation (by bidding below −24) because with the transfer of 25 he receives he is still better off than if the public good was not produced. The same is true of Sally. She’ll have to pay a tax of 24 but is still better off than if the public good was not produced. If we lower Bob’s reservation price further to below −25, he would be worse off despite the transfer and thus accurately bid the true, low value. Sally, even though she would prefer the public good to be produced in the absence of transfers would also be worse off after paying the tax and therefore has no incentive to overstate her valuation.

The problem with the Groves-Clarke mechanism is that it is very expensive—large payments are needed in order to induce individuals to bid their correct value. There are alternative mechanisms that avoid positive payments but at the expense of generating social waste (Varian 1992: 428).

4. The Private Provision of Public Goods

Mancur Olson was among the first economists who studied the private provision of public goods in great detail (Olson 1971). He argued that the existence of a common purpose or common interests is characteristic of organisations . But if these interests are served, that means that a public good has been created. Therefore:

It is of the essence of an organization that it provides an inseparable, generalized benefit. It follows that the provision of public or collective goods is the fundamental function of organizations generally. (Olson 1971: 15)

But that doesn’t mean that organisations cannot also produce private goods:

There is no suggestion here that states or other organizations provide only public or collective goods. Governments often provide noncollective goods like electric power, for example, and they usually sell such goods on the market much as private firms would do. Moreover, as later parts of this study will argue, large organizations that are not able to make membership compulsory must also provide some noncollective goods in order to give potential members an incentive to join. (Olson 1971: 16; emphasis in original)

The coupling of private and public goods is one important mechanism through which private enterprises can be enabled to provide public goods. In the eighteenth century, lighthouses were public good because their “consumption” was non-rivalrous (barring congestion) and non-excludable (using the technology available then). Port spaces are private goods, however. British lighthouses were often financed by imposing light dues on ship owners at the ports (Coase 1974). The dues were calculated by the net ton per voyage for all ships arriving at, or departing from, ports in Britain. A public good that is coupled with a private good as a mechanism for its financing is called an “impure” public good (Cornes & Sandler 1984).

Shopping centres and some apartment buildings provide other examples of impure public goods. Shopping malls provide public spaces, streets, parking space, and security for which consumers pay indirectly by buying the merchandise offered in the shopping centre. Similarly, some apartment buildings offer common spaces and infrastructure for which owners pay through supplements to the apartment prices or rentals.

The shopping centre example illustrates a potential problem for the private provision of a public good. Suppose that it is prohibitively expensive to charge individuals for the use of parking spaces provided. Parking space is then a public good because non-shoppers can use it free of charge. Suppose further that the owner of land nearby exploits the situation by building a competing shopping centre that does not offer parking space. The new shopping centre can price its competitor out of the market by offering lower prices for the merchandise it sells because it does not have to pay for parking space.

However, at least in principle the owner of the first shopping centre can avoid this by purchasing the surrounding land before free parking is allowed. After Ronald Coase this mechanism for solving externalities problems is referred to as “extending the role of the firm” (see Demsetz 1964). Another example for this mechanism involves the public good pollination. If a bee keeper and the owner of an orchard cannot agree on the value of the pollination and nectar, either is free to buy the other’s property and thus internalise the externality by extending the firm.

An alternative reason for existence of privately provided public goods is that people do not always act in a fully self-interested manner. Most economic models assume that people care only about the benefits a public good provides to them, but people in fact also care about the outcomes for others. Donations to charity and political campaigns are obvious examples. One way to model this is to assume that the act of giving itself provides additional utility distinct from the utility obtained from the aggregate level of provision of the public good (Steinberg 1987).

A third reason for the ability of public goods to be provided privately to be discussed here is the existence of social norms. For example, as long as individuals meet repeatedly to decide about the creation of a public good, they might realise that lying is self-destructive, and as the situation is iterated, it is possible that a norm of truthful revelation of the valuations is developed upon which a convention of telling the truth would be built (Taylor 1976; Schotter 1981). That a non-co-operative strategy is not necessarily optimal in repeated games is a well-known result in game theory (see entry on game theory, section on repeated games and coordination ).

Other norms such as “everyone should do their bit” or fairness and equality norms can also help to increase private contributions to public goods. People might simply think that it is morally wrong to free ride (Sugden 1984). Social norms can motivate people to act altruistically but also help to solve co-ordination problems by specifying property rights and the terms of contracts (Young 1998). Clean streets (the absence of littering) can be regarded as a public good, and let us assume that littering isn’t punishable by law. In a game-theoretic setting, individuals would be expected to underproduce the public good, i.e., to litter too much. A norm not to litter can now help to induce people to co-operate and play the non-Nash equilibrium but Pareto superior strategy. The punishment of norm-violators through social sanctions will help to make people follow the norm without the government having to police norm following.

Most mechanisms discussed in this section can be expected to work better for local public goods than for national or global public goods. It is easier to negotiate with neighbours about littering than with people who live halfway across the globe, and people tend to feel more altruistic towards others who live nearby and are in other ways similar (Hamilton 1964).

5. Empirical Work on the Public-Goods Problem

There has been an explosion of experimental work relevant to the public goods problem since the rise of experimental economics in the second half of the twentieth century. An important strand in this literature describes results from so-called “public goods games” (for a survey, see Ledyard 1995).

A typical public goods game set-up is as follows. A number n of university students is brought into a room and seated at a table. They each receive an endowment of, say, €x. They are then asked to decide how much of that to spend on a group project, where contributions can range from €0 to the entire endowment. They put their contributions into an envelope so that other participants cannot see how much each individual has contributed. The sum total of the contributions is then doubled by the experimenter and divided equally among the participants.

A public goods game is an n -person Prisoners’ Dilemma. The Pareto optimal outcome is one in which everyone contributes their entire endowment. With \(n = 10\) participants and an endowment of \(x = €10,\) each participant would wind up with \(€20.\) But each individual has an incentive to contribute less. If everyone else contributed their entire endowment, each individual could receive up to \(9*€10*2/10+€10 = €28\) if they contributed nothing. This is the same for everyone in the game, and so the Nash equilibrium strategy is to contribute \(€0,\) resulting in a payoff of \(€10\) for each participant.

In experiments, the Nash-equilibrium strategy is typically played by only some of the players. Others contribute their entire endowment and yet others a sum in between. Total contributions typically lie between 40% and 60% of the social optimum. Other stylised facts include (Ledyard 1995: 13):

- In one-shot trials and in the initial stages of finitely repeated trials, subjects generally provide contributions halfway between the Pareto-efficient level and the free riding level,

- Contributions decline with repetition, and

- Face to face communication improves the rate of contribution.

The first two points have been described as “overcontribution and decay” (Guala 2005): people tend to contribute more than we would expect from a purely strategic point of view, but these overcontributions decline when the game is played repeatedly (though never to zero). Thus, people free ride less than advocates of government funding of public goods often suggest, but private provision is still at suboptimal levels.

There are a number of explanations for these phenomena. An obvious one is experience and learning: as players become more experienced with the set up, they come to understand that they can profit from non-co-operation (especially when others are slower to learn that lesson). Another one is that players’ behaviour is motivated by different considerations. Jon Elster describes six different types of co-operative behaviour:

Cooperation needs some individuals who are not motivated merely by the costs and benefits to them. Two categories of such individuals are what we shall call full utilitarians and selfless utilitarians . The first will cooperate if and only if their contribution increases the average benefit. […] The second category will cooperate if and only if their contribution increases the average benefit, not counting the costs to them … If the selfless utilitarians are too few, or if the predicament I described deters them from acting, unconditional cooperators are needed… These actors take a number of shapes—they may be Kantians, saints, heroes, fanatics, or they may be slightly mad. What they have in common is that they act neither as a function of the expected consequences of their action, nor as a function of the number of other cooperators. A further category of actors would never act as first movers, however. These are the individuals whose motivation is triggered by the observation of others’ cooperating or by the knowledge that cooperators can observe them… A first subset of this group are motivated by the quasi-moral norm of fairness: it is not fair for us to remain on the sidelines while others are taking risks for our common cause. […] A second subset are motivated by social norms. If noncooperators can be identified and subjected to social ostracism, as is usually the case at the workplace, for example, cooperators may shame them into joining. A final category are those who join the movement for its “process benefits”—because it is fun or otherwise personally appealing. (Elster 2007: 397–9; emphasis in original)

The presence of a certain proportion of conditional co-operators would explain why contributions start relatively high but go down over time. Empirical investigations confirm this explanation as well as the presence of “mixed motives” (Villeval 2012). In a classic paper, James Andreoni has argued that patterns observed in the data about charitable giving from U.S. national surveys are inconsistent with a model of pure altruism so that other motivations must be included to account for these data (Andreoni 1988).

A large number of factors appears to affect the size of the contributions. Apart from repetition (one-shot vs repeated games and number of rounds), experience and learning, and communication, the marginal payoff of contributions, the size of the group, provision points (in some experiments the public good is provided only if contributions reach a certain threshold), the heterogeneity of payoffs and endowments, and moral suasion (i.e., the priming of experimental subjects by experimenters) are among the factors that make a difference (Ledyard 1995: 36). Some results are quite surprising. For example, contributions increase with increasing thresholds at which the public good is provided while the probability that the threshold will be reached goes down (Isaac, Walker, & Thomas 1984). However, with heterogeneous endowments, there are no significant differences of contributions at different levels (Rapoport & Suleiman 1993). Similarly, contrary to economists’ expectations, group size can have a positive effect on contributions while it dilutes the effect of marginal returns (Isaac, Walker, & Williams 1994). That causal factors affect experimental results in unsystematic and quite unexpected ways appears to be a fairly general feature of experimental economics (Reiss 2008: Ch. 5).

Other kinds of empirical evidence that is relevant to the public goods problem include field experiments, observational studies, and case studies. They all have in common that they provide evidence that individuals make some voluntary contributions to public goods. What they investigate are the factors that affect the sizes of the contributions and the mechanisms used to encourage people to contribute.

Field studies have been used to examine the relationship between an individual’s contributions to a public good and others’ contributions. Depending on what one thinks individuals’ primary motivations are, one would expect an individual’s and others’ contributions to be substitutes or complements. If an individual is primarily motivated by altruism, he or she will care about the consumption of others and therefore contribute less when others or the government already contribute enough. In this case we would expect the two kinds of contributions to be substitutes. If, by contrast, an individual is primarily motivated my social norms such as fairness and reciprocity, he or she will contribute when others do their bit. In that case, we would expect the two kinds of contributions to be complements. Whether they are on average substitutes or complements is an issue that is difficult to determine in laboratory experiments due to the relatively small sample sizes and because the mix of motivations may differ between experiment and field.

A field experiment involving an on-air fundraising campaign for a public radio station found support for the complementarity hypothesis (Shang & Croson 2009). Specifically, if social information is provided about a high contribution of another donor, pledges increase and the likelihood that a donor contributes again next year goes up. The same has been found in a study of voluntary contributions to an information good (a newsletter) on the Internet (Borck et al. 2006). There have also been field studies of alternative provision mechanisms, comparing a voluntary contribution mechanism for a pure public environmental good to a green tariff mechanism, which can be interpreted as an impure public good (Kotchen & Moore 2007).

The substitutes-vs-complements issue has also been investigated in observational studies . That contributions are perfect substitutes, i.e., that government contributions or other private contributions crowd out an individual’s contribution completely is widely rejected. “Complete crowding out” here would mean that every dollar spent on a public good by the government reduces private spending by the same amount. Most studies find either no crowding out, or a merely a small amount. For example, Kingma 1989 and Kingma & McClelland 1995, focusing on public radio, found only a limited amount of crowding out between 12% and 19% of government expenditures on public radio (i.e., one dollar spent by government reduces private contributions by 12–19 cents).

There are a number of historical case studies as well. Ronald Coase’s study of the provision of lighthouses in nineteenth century Britain has already been mentioned. Cowen 1992 contains a number of further case studies that look closely at contracts between bee keepers and apple growers (exchanging the public good pollination) in Washington State, fire protection, leisure and recreation in the United States, species conservation in the Cayman Islands, and education in Great Britain before large-scale state subsidies. In each of these cases, the authors point to private solutions to the public goods problem. A historical review of publicly financed public goods is provided in Desai 2003.

6. The Ethics of Public Goods: Should the Government Pay for Public Goods?

It is sometimes suggested that the standard justification for government funding is attractive because it is based on a minimum of normative assumptions. David Schmidtz, for example, writes that

one of the most attractive features of the public goods argument is the minimal nature of the normative assumptions it must make in order to ground a justification of the state. (Schmidtz 1991: 82)

Indeed, it seems that all that is required is that a government intervention is justified if it brings about a state of affairs that makes everyone better off than under any non-intervention alternative.

However, to reach the conclusion that the government should provide public goods, one requires a number of additional assumptions, all of which are controversial. Standard welfare economics identifies well-being with preference satisfaction, a view that has received much criticism (see entry on well being ; Nussbaum 2001; Hausman et al. 2017: Ch. 8; Reiss 2013: Ch. 12). It is implausible to assume that people always choose what is best for them. People may have inconsistent or unstable preferences such as the smoker who flushes his cigarettes down the toilet in an attempt to quit smoking, just in order to buy a new pack the next day. If people have inconsistent or unstable preferences, it is unclear which consistent set to choose for policy. Uninformed preferences also appear to be a bad basis for policy. If people erroneously believe, say, that there is no external threat, they might prefer less investment in national defence than if they were fully informed. It has been argued that in the political realm, insufficient knowledge is the norm rather than the exception (Somin 1998, Caplan 2007, Somin 2013). It might be extraordinarily difficult to assess the value of a public good to an individual, especially if the public good is a national or global one such as defence, climate change mitigation or basic research.

It has therefore been argued that rational or laundered or informed preferences should provide the basis for policy decisions (e.g., Thaler & Sunstein 2008, Anomaly 2015). But it is not clear that we can straightforwardly assess what citizens would prefer if they were fully rational and informed. There is always the danger that whoever makes that assessment substitutes his or her preferences for the citizens’ or that his or her preferences influence the judgement about what the citizens’ preferences might be (Rizzo & Whitman 2008, 2009).

Assessing the value of a public good in terms of preference satisfaction, actual or rational, involves another problem: the impossibility of interpersonal comparisons. Suppose there are two indivisible public goods A and B , Bob prefers A while Sally prefers B , and Bob and Sally’s combined wealth suffices to buy only either A or B . Under a preference-satisfaction account of welfare, there arguably is no normatively defensible way to compare Bob’s welfare when A is purchased to Sally’s welfare when B is purchased or to compare what Bob would gain by purchasing and what Sally would gain by purchasing B . Dan Hausman has argued that this problem constitutes a reason to abandon the preference-satisfaction account of welfare because any moral theory that assesses situations fully or in part in terms of welfare requires interpersonal comparisons (Hausman 1995).

Standard welfare economics does not make interpersonal comparisons because it asks whether policies constitute a Pareto improvement over the status quo. A policy constitutes a Pareto improvement if and only if it makes some people better off while making no-one worse off. But few policies are as unequivocal as this standard demands. Especially when it comes to the items that are usually discussed under the rubric of public goods, it is rarely if ever the case that no-one is made worse off by the provision.

An alternative that has been introduced in the late 1930s is Hicks-Kaldor improvement (after Hicks 1939 and Kaldor 1939). If there are winners and losers to a policy, it constitutes a Hicks-Kaldor improvement whenever losers can be compensated by winners’ gains. But that losers can be compensated is little consolation unless they actually are compensated, and there is no reason to believe that this always happens (see for instance Rodrik 2017 on the failures to compensate losers from free-trade arrangements).

Characterising the public goods problem as a simple Prisoners’ Dilemma is therefore a significant idealisation. Frequently, the production of a public good will benefit some but make others worse off. Generally speaking, the decision whether to provide a public good or not involves issues of fairness, equality and justice.

Welfare economists tend to ignore such issues because neither Pareto improvements nor Kaldor-Hicks improvements (in their usual interpretations) need information about anything other than preferences. Indeed, standard welfare economics assumes that well-being is all that matters to the evaluation of social outcomes. Most people, however, care also about other values (Sen 1999: Ch. 3; Hausman et al. 2017: Chs 9–12; Reiss 2013: Ch. 14).

One moral issue that has to be addressed even when the item in question is unequivocally a public good to everyone affected by its provision is that of paternalism (see entry on paternalism ). It is by no means obvious that a coercive government intervention, even one that makes everyone better off is justified. Austrian-School economist Hans-Herrmann Hoppe expresses scepticism about the permissibility of such interventions when he writes:

The norm required to reach the above conclusion is this: Whenever one can somehow prove that the production of a particular good or service has a positive effect on someone else but would not be produced at all or would not be produced in a definite quantity or quality unless certain people participated in its financing, then the use of aggressive violence against these persons is allowed, either directly or indirectly with the help of the state, and these persons may be forced to share in the necessary financial burden. (Hoppe 1989: 31)

Infringements on rights are not the only worry we might have. Some public goods might disproportionately benefit those who are already relatively well-off and therefore exacerbate existing inequalities. Some aspects of tertiary education, for instance, might well be public goods but if tertiary education was mainly to the benefit of relatively well-off individuals, government provision could be considered unfair. It is therefore not clear whether the government provision of a public good is morally good, all things considered.

One point that advocates of government provision of public goods often overlook is the information creation and coordinating function of the price system (as described by Hayek 1945). In a market, prices generate information about preferences and scarcities. If a good is wanted by many individuals, it will become more scarce and its price will rise. The increase in price does not only provide a reason for consumers to buy less of it, it also signals to producers to make more and to potential market entrants that the market is lucrative. In the long run, supply should therefore increase and the price fall again. This mechanism does not operate when the government provides the public good and finances it by taxation. If the government builds, say, a lighthouse, it will be difficult to determine how much to invest every year, whether and how to extend or alter the service provided by the good (e.g., by building a second lighthouse nearby), and whether to invest in the development of new technologies.

So far, we have looked at public goods mainly as economic goods that have certain characteristics that give rise to doubts whether they can be provided privately at efficient levels. The government might be justified in engaging in the production of a public good because it corrects a market failure. Such an argument will always be contingent on private actors’ inability to produce the good or enough of it, which is why mechanisms that encourage private provision have been examined at some length in Section 4 above.

Some philosophers have offered arguments to the effect that the government should provide certain goods, independently of whether or not they could be produced in sufficient quantities by the market. Michael Waltzer and Elizabeth Anderson have argued that the sphere of the market should be limited because market norms do not embody certain important values and market exchange may undermine ideals and interests legitimately protected by the state (Walzer 1983, Anderson 1993). According to Anderson, market norms have the following five features: they are impersonal (independent of the relationship and of the other party’s ends), egoistic (the goal is to satisfy one’s personal interests), exclusive (defined as above), want-regarding (as opposed to responsive to objective needs), and oriented to “exit” rather than “voice” (rather than voicing one’s complaint one seeks an alternative) (see Anderson 1993: 143–4).

A good is an economic good according to Anderson if its production, distribution, and enjoyment are properly governed by market norms (Anderson 1993: 146). This contrasts with a number of other kinds of goods, such as gift goods. Friendly gift exchange should be responsive to the personal characteristics of the receiver, and to the relationship itself, rather than “impersonal”. It should also express an understanding of the relationship and not merely satisfy the receiver’s subjective wants. Giving money is often regarded as offensive exactly because it ignores these characteristics of gift goods.

What economists call public goods fall into Anderson’s category of “political goods”. They are characterised by three norms that oppose the respective market norms (Anderson 1993: 159). First, one’s freedom is exercised through voice rather than exit. Second, goods are distributed according to public principles rather than subjective wants. Third, the goods are provided on a non-exclusive basis. About these goods she says:

Some goods can be secured only through a form of democratic provision that is nonexclusive, principle- and need- regarding, and regulated primarily through voice. To attempt to provide these goods through market mechanisms is to undermine our capacity to value and realize ourselves as fraternal democratic citizens. (Anderson 1993: 159)

The examples Anderson discusses in this section of her book—roads, parks, primary and secondary education—are all public goods in the economist’s sense. Providing them privately would undermine the “capacity to value and realize ourselves as fraternal democratic citizens” because exercising freedom by voice would be replaced by exit (e.g., when parents send their kids to schools that approximate their values better than others instead of contributing to curricula through voice), by allowing owners to dictate terms on the basis of their wants instead of using principles such as freedom of speech and association (e.g., when owners of malls suppress speech and political activity they find offensive), and by the ability of owners to exclude non-payers instead of enabling all to meet one another on terms of equality (e.g., in the case of parks).

In a similar vein, Angela Kallhoff argues that some (but not all) public goods provide additional externalities that are essential for the functioning of a democracy (Kallhoff 2011, 2014). Some public goods constitute visible expressions of solidarity and social justice among citizens (“central goods”), some support connectivity and serve as representations of shared interests (“connectivity goods”), and some serve as visible representations of a shared sense of citizenship (“identification goods”). The absence of these goods would undermine the ability of the citizenry to engage in public deliberation and develop a sense of self-determination.

- Anderson, Elizabeth, 1993, Value in Ethics and Economics , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Andreoni, James, 1988, “Privately Provided Public Goods in a Large Economy: The Limits of Altruism”, Journal of Public Economics , 35: 57–73. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(88)90061-8

- Anomaly, Jonathan, 2015, “Public Goods and Government Action”, Politics, Philosophy & Economics , 14(2): 109–128. doi:10.1177/1470594X13505414

- Blaug, Mark, 1985, Economic Theory in Retrospect , fourth edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boldrin, Michele and David K. Levine, 2008, Against Intellectual Monopoly , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511510854

- Borck, Rainald, Björn Frank, and Julio R. Robledo, 2006, “An Empirical Analysis of Voluntary Payments for Information Goods on the Internet”, Information Economics and Policy , 18(2): 229–239. doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2006.01.003

- Bouckaert, Boudewijn, 1987, “Public Goods and the Rise of the Nation State”, unpublished manuscript, Ghent University.

- Buchanan, James M., 1965, “An Economic Theory of Clubs”, Economica , 32(125): 1–14. doi:10.2307/2552442

- Caplan, Bryan, 2007, The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies , Princeton, N:, Princeton University Press.

- Clarke, Edward H., 1971, “Multipart Pricing of Public Goods”, Public Choice , 11: 17–33. doi:10.1007/BF01726210

- Coase, Ronald H., 1974, “The Lighthouse in Economics”, The Journal of Law and Economics , 17(2): 357–376. doi:10.1086/466796

- Cornes, Richard and Todd Sandler, 1984, “Easy Riders, Joint Production, and Public Goods”, The Economic Journal , 94(375): 580–598. doi:10.2307/2232704

- Cowen, Tyler (ed.), 1992, Public Goods and Market Failures: A Critical Examination , New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Demsetz, Harold, 1964, “The Exchange and Enforcement of Property Rights”, The Journal of Law and Economics , 7: 11–26. doi:10.1086/466596

- Desai, Meghnad, 2003, “Public Goods: A Historical Perspective”, in Kaul et al. 2003: 63–77.

- Elster, Jon, 2007, Explaining Social Behavior: More Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Revised edition 2015. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107763111

- Groves, Theodore, 1973, “Incentives in Teams”, Econometrica , 41(4): 617–631. doi:10.2307/1914085

- Guala, Francesco, 2005, The Methodology of Experimental Economics , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511614651

- Hamilton, William D., 1964, “The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour. I”, Journal of Theoretical Biology , 7(1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4

- Hausman, Daniel M., 1995, “The Impossibility of Interpersonal Utility Comparisons”, Mind , 104(415): 473–490. doi:10.1093/mind/104.415.473

- Hausman, Daniel, Michael McPherson, and Debra Satz, 2017, Economic Analysis, Moral Philosophy, and Public Policy , third edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316663011

- Hayek, Friedrich A., 1945, “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, The American Economic Review , 35(4): 519–530.

- Hicks, John R., 1939, “The Foundations of Welfare Economics”, The Economic Journal , 49(196): 696–712. doi:10.2307/2225023

- Hoppe, Hans-Herrmann, 1989, “Fallacies of the Public Goods Theory and the Production of Security”, The Journal of Libertarian Studies , 9(1): 27–46.

- Isaac, R. Mark, James M. Walker, and Susan H. Thomas, 1984, “Divergent Evidence on Free Riding: An Experimental Examination of Possible Explanations”, Public Choice , 43(2): 113–149. doi:10.1007/BF00140829

- Isaac, R. Mark, James M. Walker, and Arlington W. Williams, 1994, “Group Size and the Voluntary Provision of Public Goods”, Journal of Public Economics , 54: 1–36. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(94)90068-X

- Johansen, Leif, 1977, “The Theory of Public Goods: Misplaced Emphasis?”, Journal of Public Economics , 7: 147–152. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(77)90042-1

- Kaldor, Nicholas, 1939, “Welfare Propositions of Economics and Interpersonal Comparisons of Utility”, The Economic Journal , 49(195): 549–552. doi:10.2307/2224835

- Kallhoff, Angela, 2011, Why Democracy Needs Public Goods , Landham, MD: Lexington Books.

- –––, 2014, “Why Societies Need Public Goods”, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy , 17(6): 635–651. doi:10.1080/13698230.2014.904539

- Kaul, Paul, Pedro Conceição, Katell Le Goulven, and Ronald U. Mendoza (eds.), 2003, Providing Global Public Goods: Managing Globalization , Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0195157400.001.0001

- Kingma, Bruce Robert, 1989, “An Accurate Measurement of the Crowd-out Effect, Income Effect, and Price Effect for Charitable Contributions”, Journal of Political Economy , 97(5): 1197–1207. doi:10.1086/261649

- Kingma, Bruce R. and Robert McClelland, 1995, “Public Radio Stations Are Really, Really Not Public Goods”, Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics , 66(1): 65–76.

- Kotchen, Matthew J. and Michael R. Moore, 2007, “Private Provision of Environmental Public Goods: Household Participation in Green-Electricity Programs”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , 53(1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2006.06.003

- Ledyard, John, 1995, “Public Goods: A Survey of Experimental Research”, in The Handbook of Experimental Economics , Vol. 1, John Kagel and Alvin Roth (eds), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 111–194.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory, 2012, Principles of Microeconomics , sixth edition, Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Mill, John Stuart, 1848 [1963], “Principles of Political Economy”, in Collected Works of John Stuart Mill , vols. 2–3, J. M. Robson (ed.), Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Musgrave, Richard, 1959, A Theory of Public Finance , New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Nussbaum, Martha C., 2001, “Symposium on Amartya Sen’s Philosophy: 5 Adaptive Preferences and Women’s Options”, Economics and Philosophy , 17(1): 67–88. doi:10.1017/S0266267101000153

- OECD, 2016, “Integrity Framework for Public Infrastructure”, OECD Public Governance Reviews , Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [ OECD 2016 available online ]

- Olson, Mancur, 1971, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups , Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ostrom, Elinor, 2003, “How Types of Goods and Property Rights Jointly Affect Collective Action”, Journal of Theoretical Politics , 15(3): 239–270. doi:10.1177/0951692803015003002

- Ostrom, Elinor, Roy Gardner, and James Walker, 1994, Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources , Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.