Brown v. Board of Education: Annotated

The 1954 Supreme Court decision, based on the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, declared that “separate but equal” has no place in education.

The US Supreme Court’s decision in the case known colloquially as Brown v. Board of Education found that the “[t]he ‘separate but equal ’ doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education.” The Plessy case, decided in 1896, had found that the segregation laws which created “separate but equal” accommodations for Black Americans, specific to transportation but applicable generally, were not a violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Segregation in education had been challenged throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and rulings in a number coalesced to propel Brown to the level of the Supreme Court to address segregation in all public schools.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Below is an annotation of the opinion, with relevant scholarship covering the legal, social and education history leading up to and after the decision. As always, the supporting research is free to read and download.

The red J indicates free access to the linked research on JSTOR . ____________________________________________________________________________

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954) (USSC+)

Argued December 9, 1952

Reargued December 8, 1953

Decided May 17, 1954

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS*

Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment —even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors of white and Negro schools may be equal.

(a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education.

(b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation.

(c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

(d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal.

(e) The “separate but equal” doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education.

(f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees.

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion.

In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called “separate but equal” doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537 . Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case , the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools.

The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not “equal” and cannot be made “equal,” and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. Because of the obvious importance of the question presented, the Court took jurisdiction. Argument was heard in the 1952 Term, and reargument was heard this Term on certain questions propounded by the Court.

Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive. The most avid proponents of the post-War Amendments undoubtedly intended them to remove all legal distinctions among “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” Their opponents, just as certainly, were antagonistic to both the letter and the spirit of the Amendments and wished them to have the most limited effect. What others in Congress and the state legislatures had in mind cannot be determined with any degree of certainty.

An additional reason for the inconclusive nature of the Amendment’s history with respect to segregated schools is the status of public education at that time. In the South, the movement toward free common schools, supported by general taxation, had not yet taken hold . Education of white children was largely in the hands of private groups. Education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states. Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences, as well as in the business and professional world. It is true that public school education at the time of the Amendment had advanced further in the North, but the effect of the Amendment on Northern States was generally ignored in the congressional debates. Even in the North, the conditions of public education did not approximate those existing today. The curriculum was usually rudimentary; ungraded schools were common in rural areas; the school term was but three months a year in many states, and compulsory school attendance was virtually unknown. As a consequence, it is not surprising that there should be so little in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment relating to its intended effect on public education.

In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the Negro race. The doctrine of “separate but equal” did not make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson , supra, involving not education but transportation. American courts have since labored with the doctrine for over half a century. In this Court, there have been six cases involving the “separate but equal” doctrine in the field of public education. In Cumming v. County Board of Education , 175 US 528 , and Gong Lum v. Rice , 275 US 78 , the validity of the doctrine itself was not challenged. In more recent cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada , 305 US 337 ; Sipuel v. Oklahoma , 332 US 631; Sweatt v. Painter , 339 US 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , 339 US 637 . In none of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter , supra, the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education.

In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here, unlike Sweatt v. Painter , there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other “tangible” factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.

Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship . Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does.

In Sweatt v. Painter , supra, in finding that a segregated law school for Negroes could not provide them equal educational opportunities, this Court relied in large part on “those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school.” In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , supra, the Court, in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate school be treated like all other students, again resorted to intangible considerations: “…his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.” Such considerations apply with added force to children in grade and high schools. To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law , for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system .

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson , this finding is amply supported by modern authority. Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected.

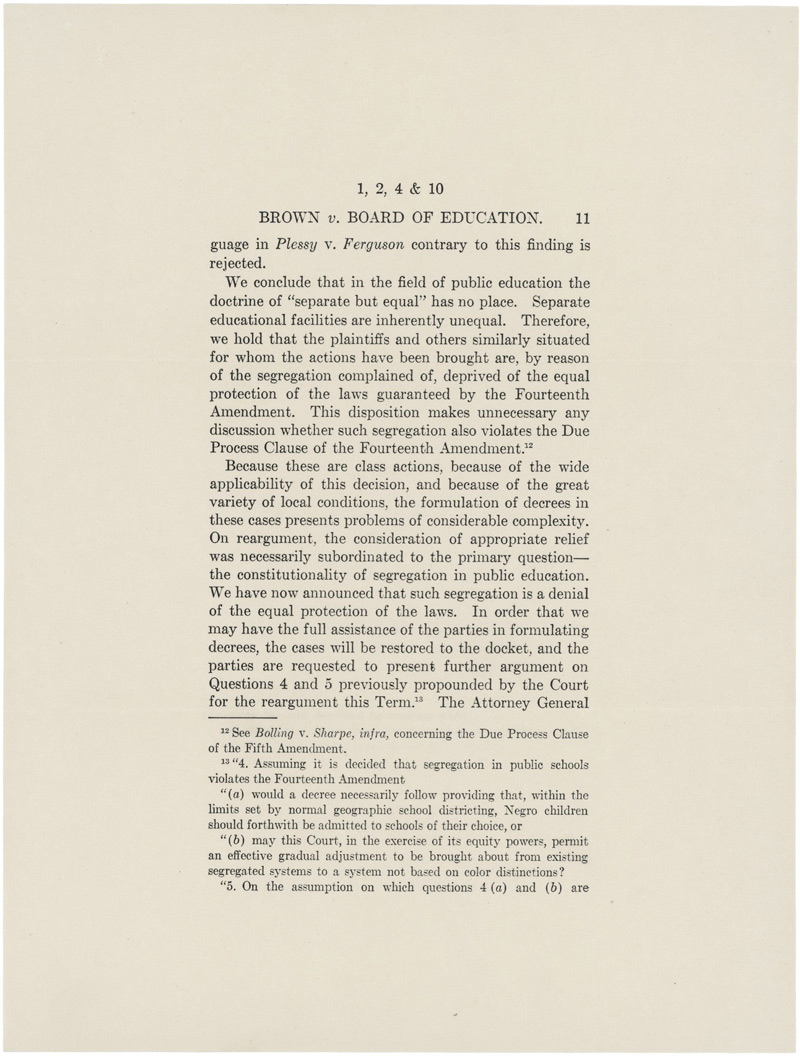

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal . Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Because these are class actions, because of the wide applicability of this decision, and because of the great variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases presents problems of considerable complexity . On reargument, the consideration of appropriate relief was necessarily subordinated to the primary question—the constitutionality of segregation in public education. We have now announced that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. In order that we may have the full assistance of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will be restored to the docket, and the parties are requested to present further argument on Questions 4 and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargument this Term The Attorney General of the United States is again invited to participate. The Attorneys General of the states requiring or permitting segregation in public education will also be permitted to appear as amici curiae upon request to do so by September 15, 1954, and submission of briefs by October 1, 1954.

It is so ordered.

* Together with No. 2, Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, argued December 9–10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953; No. 4, Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, argued December 10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953, and No. 10, Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al. , on certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware, argued December 11, 1952, reargued December 9, 1953.

[Transcript available from the National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/brown-v-board-of-education ]

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- The Post Office and Privacy

- The British Empire’s Bid to Stamp Out “Chinese Slavery”

- Tramping Across the USSR (On One Leg)

Harvey Houses: Serving the West

Recent posts.

- Debt-Trap Diplomacy

- How Government Helped Birth the Advertising Industry

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Brown v. Board of Education

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 27, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown v. Board of Education was one of the cornerstones of the civil rights movement, and helped establish the precedent that “separate-but-equal” education and other services were not, in fact, equal at all.

Separate But Equal Doctrine

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for Black people and whites were equal.

The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites—known as “Jim Crow” laws —and established the “separate but equal” doctrine that would stand for the next six decades.

But by the early 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ) was working hard to challenge segregation laws in public schools, and had filed lawsuits on behalf of plaintiffs in states such as South Carolina, Virginia and Delaware.

In the case that would become most famous, a plaintiff named Oliver Brown filed a class-action suit against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1951, after his daughter, Linda Brown , was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools.

In his lawsuit, Brown claimed that schools for Black children were not equal to the white schools, and that segregation violated the so-called “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment , which holds that no state can “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The case went before the U.S. District Court in Kansas, which agreed that public school segregation had a “detrimental effect upon the colored children” and contributed to “a sense of inferiority,” but still upheld the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Brown v. Board of Education Verdict

When Brown’s case and four other cases related to school segregation first came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court combined them into a single case under the name Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka .

Thurgood Marshall , the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, served as chief attorney for the plaintiffs. (Thirteen years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson would appoint Marshall as the first Black Supreme Court justice.)

At first, the justices were divided on how to rule on school segregation, with Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson holding the opinion that the Plessy verdict should stand. But in September 1953, before Brown v. Board of Education was to be heard, Vinson died, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower replaced him with Earl Warren , then governor of California .

Displaying considerable political skill and determination, the new chief justice succeeded in engineering a unanimous verdict against school segregation the following year.

In the decision, issued on May 17, 1954, Warren wrote that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” as segregated schools are “inherently unequal.” As a result, the Court ruled that the plaintiffs were being “deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.”

Little Rock Nine

In its verdict, the Supreme Court did not specify how exactly schools should be integrated, but asked for further arguments about it.

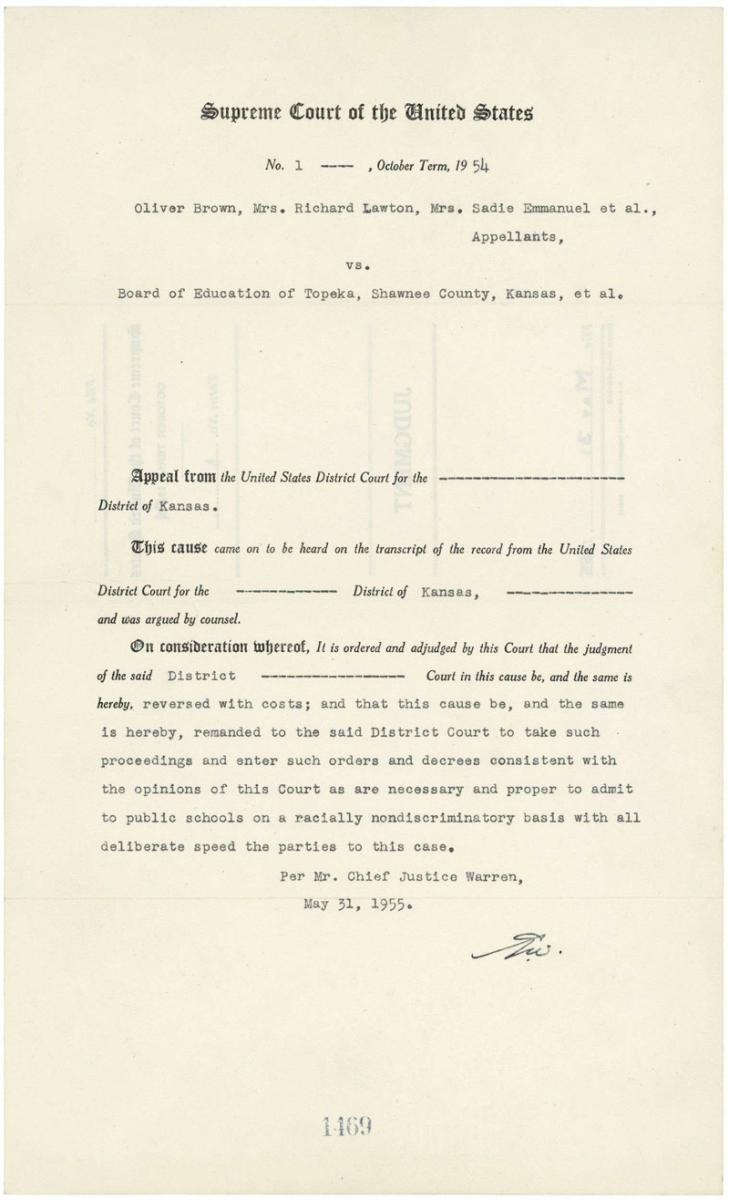

In May 1955, the Court issued a second opinion in the case (known as Brown v. Board of Education II ), which remanded future desegregation cases to lower federal courts and directed district courts and school boards to proceed with desegregation “with all deliberate speed.”

Though well intentioned, the Court’s actions effectively opened the door to local judicial and political evasion of desegregation. While Kansas and some other states acted in accordance with the verdict, many school and local officials in the South defied it.

In one major example, Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the state National Guard to prevent Black students from attending high school in Little Rock in 1957. After a tense standoff, President Eisenhower deployed federal troops, and nine students—known as the “ Little Rock Nine ”— were able to enter Central High School under armed guard.

Impact of Brown v. Board of Education

Though the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board didn’t achieve school desegregation on its own, the ruling (and the steadfast resistance to it across the South) fueled the nascent civil rights movement in the United States.

In 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery bus boycott and would lead to other boycotts, sit-ins and demonstrations (many of them led by Martin Luther King Jr .), in a movement that would eventually lead to the toppling of Jim Crow laws across the South.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , backed by enforcement by the Justice Department, began the process of desegregation in earnest. This landmark piece of civil rights legislation was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 .

Runyon v. McCrary Extends Policy to Private Schools

In 1976, the Supreme Court issued another landmark decision in Runyon v. McCrary , ruling that even private, nonsectarian schools that denied admission to students on the basis of race violated federal civil rights laws.

By overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education had set the legal precedent that would be used to overturn laws enforcing segregation in other public facilities. But despite its undoubted impact, the historic verdict fell short of achieving its primary mission of integrating the nation’s public schools.

Today, more than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education , the debate continues over how to combat racial inequalities in the nation’s school system, largely based on residential patterns and differences in resources between schools in wealthier and economically disadvantaged districts across the country.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

History – Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment, United States Courts . Brown v. Board of Education, The Civil Rights Movement: Volume I (Salem Press). Cass Sunstein, “Did Brown Matter?” The New Yorker , May 3, 2004. Brown v. Board of Education, PBS.org . Richard Rothstein, Brown v. Board at 60, Economic Policy Institute , April 17, 2014.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Educator Resources

Brown v. Board of Education

The Supreme Court's opinion in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954 legally ended decades of racial segregation in America's public schools. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement. Read more...

Primary Sources

Links go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

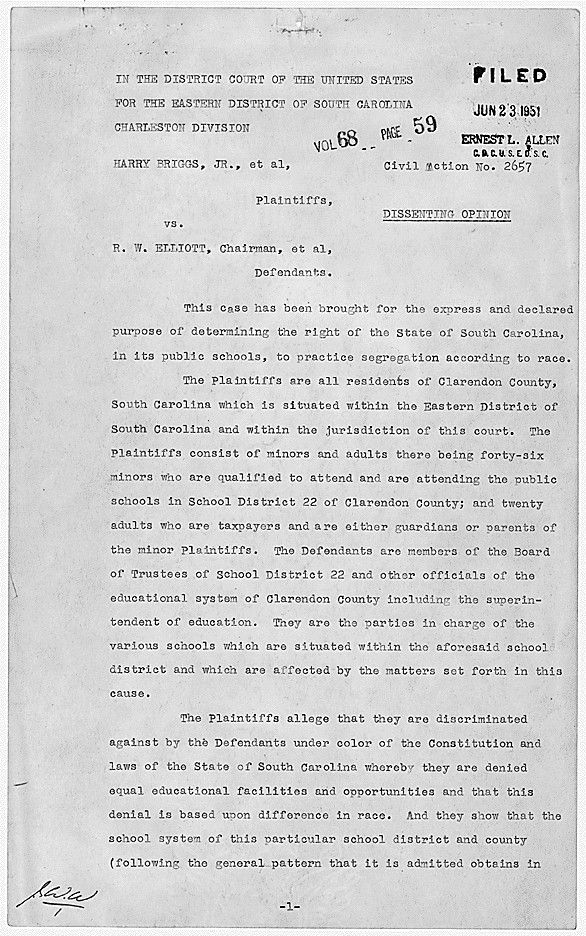

Dissenting opinion in Briggs v. Elliott in which Judge Waties Waring opposed the District Court ruling that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment – he presented arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas , 6/21/1951

View in National Archives Catalog

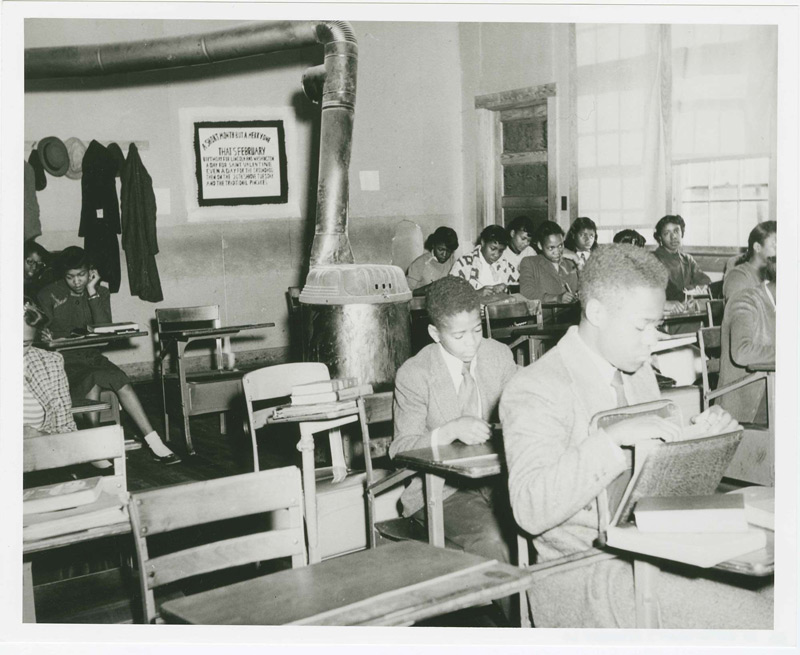

English class at Moton High School , a school for Black students, one of several photographs entered as evidence in the case Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia , which was one of five cases that the Supreme Court consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education , ca. 1951

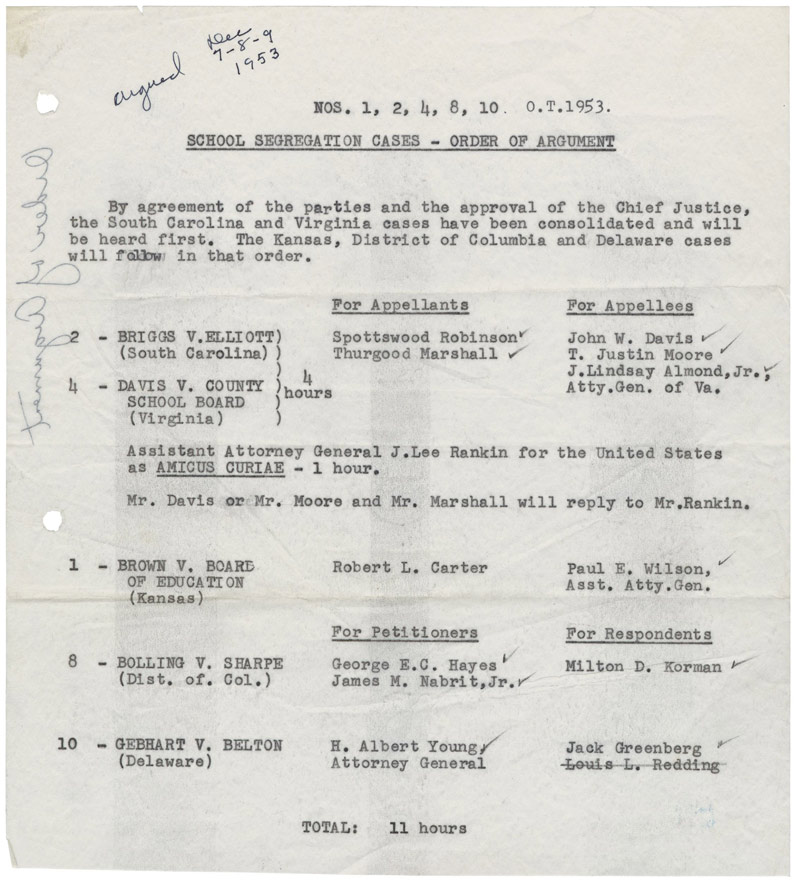

Order of Argument in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka during which attorneys reargued the five cases that the Supreme Court heard collectively and consolidated under the name Brown v. Board of Education , 12/1953

Page 11 of the unanimous Supreme Court ruling of 5/17/1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools violated the 14th Amendment, marking the end of the "separate but equal" precedent

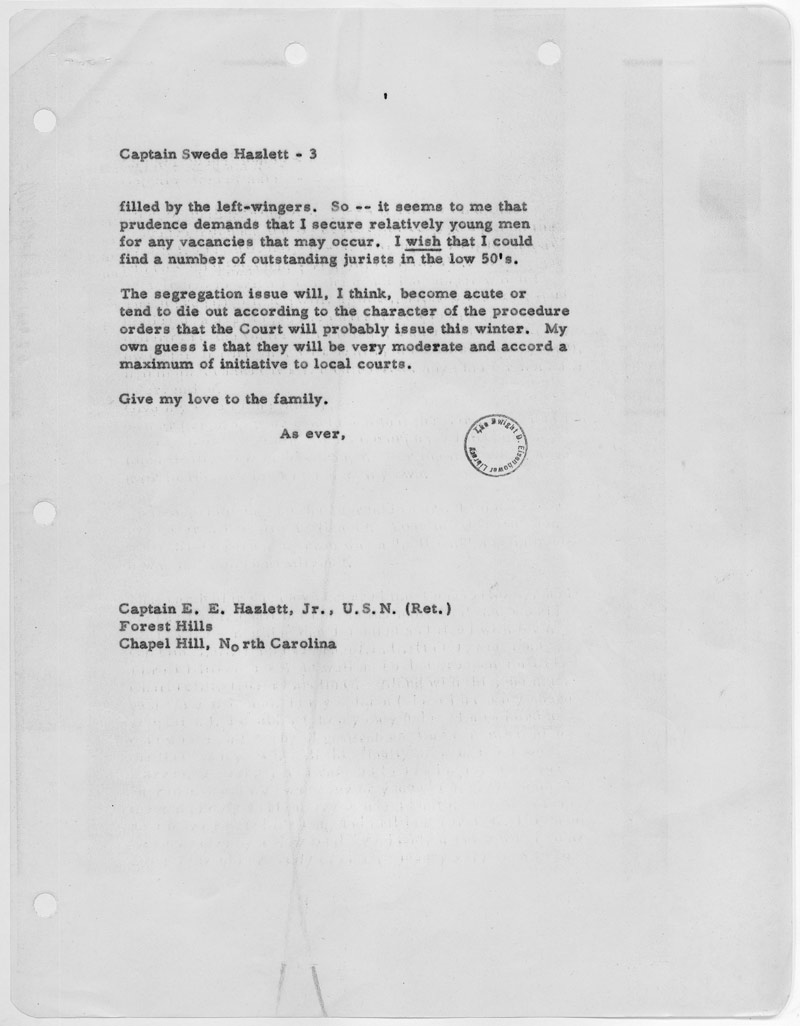

Page 3 of a letter from President Eisenhower to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett in which the President expressed his belief that the new Warren court would be very moderate on the issue of segregation, 10/23/1954

Judgment of May 31, 1955, in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II) – a year after the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional – directing that schools be desegregated "with all deliberate speed"

- Brown v. Board of Education Timeline

- Biographies of Key Figures

- Related Primary Sources: Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case

Teaching Activities

The "Rights in America" page on DocsTeach includes primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to how individuals and groups have asserted their rights as Americans. It includes topics such as segregation, racism, citizenship, women's independence, immigration, and more.

Additional Background Information

While the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution outlawed slavery, it wasn't until three years later, in 1868, that the 14th Amendment guaranteed the rights of citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including due process and equal protection of the laws. These two amendments, as well as the 15th Amendment protecting voting rights, were intended to eliminate the last remnants of slavery and to protect the citizenship of Black Americans.

In 1875, Congress also passed the first Civil Rights Act, which held the "equality of all men before the law" and called for fines and penalties for anyone found denying patronage of public places, such as theaters and inns, on the basis of race. However, a reactionary Supreme Court reasoned that this act was beyond the scope of the 13th and 14th Amendments, as these amendments only concerned the actions of the government, not those of private citizens. With this ruling, the Supreme Court narrowed the field of legislation that could be supported by the Constitution and at the same time turned the tide against the civil rights movement.

By the late 1800s, segregation laws became almost universal in the South where previous legislation and amendments were, for all practical purposes, ignored. The races were separated in schools, in restaurants, in restrooms, on public transportation, and even in voting and holding office.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson . Homer Plessy, a Black man from Louisiana, challenged the constitutionality of segregated railroad coaches, first in the state courts and then in the U. S. Supreme Court.

The high court upheld the lower courts, noting that since the separate cars provided equal services, the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment was not violated. Thus, the "separate but equal" doctrine became the constitutional basis for segregation. One dissenter on the Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan, declared the Constitution "color blind" and accurately predicted that this decision would become as baneful as the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857.

In 1909 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was officially formed to champion the modern Civil Rights Movement. In its early years its primary goals were to eliminate lynching and to obtain fair trials for Black Americans. By the 1930s, however, the activities of the NAACP began focusing on the complete integration of American society. One of their strategies was to force admission of Black Americans into universities at the graduate level where establishing separate but equal facilities would be difficult and expensive for the states.

At the forefront of this movement was Thurgood Marshall, a young Black lawyer who, in 1938, became general counsel for the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund. Significant victories at this level included Gaines v. University of Missouri in 1938, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma in 1948, and Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. In each of these cases, the goal of the NAACP defense team was to attack the "equal" standard so that the "separate" standard would in turn become susceptible.

Five Cases Consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education

By the 1950s, the NAACP was beginning to support challenges to segregation at the elementary school level. Five separate cases were filed in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware:

- Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

- Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R.W. Elliott, et al.

- Dorothy E. Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al.

- Spottswood Thomas Bolling et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe et al.

- Francis B. Gebhart et al. v. Ethel Louise Belton et al.

While each case had its unique elements, all were brought on the behalf of elementary school children, and all involved Black schools that were inferior to white schools. Most importantly, rather than just challenging the inferiority of the separate schools, each case claimed that the "separate but equal" ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

The lower courts ruled against the plaintiffs in each case, noting the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of the United States Supreme Court as precedent. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education , the Federal district court even cited the injurious effects of segregation on Black children, but held that "separate but equal" was still not a violation of the Constitution. It was clear to those involved that the only effective route to terminating segregation in public schools was going to be through the United States Supreme Court.

In 1952 the Supreme Court agreed to hear all five cases collectively. This grouping was significant because it represented school segregation as a national issue, not just a southern one. Thurgood Marshall, one of the lead attorneys for the plaintiffs (he argued the Briggs case), and his fellow lawyers provided testimony from more than 30 social scientists affirming the deleterious effects of segregation on Black and white children. These arguments were similar to those alluded to in the Dissenting Opinion of Judge Waites Waring in Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R. W. Elliott, Chairman, et al . (shown above).

These [social scientists] testified as to their study and researches and their actual tests with children of varying ages and they showed that the humiliation and disgrace of being set aside and segregated as unfit to associate with others of different color had an evil and ineradicable effect upon the mental processes of our young which would remain with them and deform their view on life until and throughout their maturity....They showed beyond a doubt that the evils of segregation and color prejudice come from early training...it is difficult and nearly impossible to change and eradicate these early prejudices however strong may be the appeal to reason…if segregation is wrong then the place to stop it is in the first grade and not in graduate colleges.

The lawyers for the school boards based their defense primarily on precedent, such as the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, as well as on the importance of states' rights in matters relating to education.

Realizing the significance of their decision and being divided among themselves, the Supreme Court took until June 1953 to decide they would rehear arguments for all five cases.

The arguments were scheduled for the following term. The Court wanted briefs from both sides that would answer five questions, all having to do with the attorneys' opinions on whether or not Congress had segregation in public schools in mind when the 14th amendment was ratified.

The Order of Argument (shown above) offers a window into the three days in December of 1953 during which the attorneys reargued the cases. The document lists the names of each case, the states from which they came, the order in which the Court heard them, the names of the attorneys for the appellants and appellees, the total time allotted for arguments, and the dates over which the arguments took place.

Briggs v. Elliott

The first case listed, Briggs v. Elliott , originated in Clarendon County, South Carolina, in the fall of 1950. Harry Briggs was one of 20 plaintiffs who were charging that R.W. Elliott, as president of the Clarendon County School Board, violated their right to equal protection under the fourteenth amendment by upholding the county's segregated education law. Briggs featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs from some of the nation's leading child psychologists, such as Dr. Kenneth Clark, whose famous doll study concluded that segregation negatively affected the self-esteem and psyche of African-American children. Such testimony was groundbreaking because on only one other occasion in U.S. history had a plaintiff attempted to present such evidence before the Court.

Thurgood Marshall, the noted NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice, argued the Briggs case at the District and Federal Court levels. The U.S. District Court's three-judge panel ruled against the plaintiffs, with one judge dissenting, stating that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment. In his dissenting opinion (shown above), Judge Waties Waring presented some of the arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas . The case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia

Marshall also argued the Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, case at the Federal level. Originally filed in May of 1951 by plaintiff's attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, the Davis case, like the others, argued that Virginia's segregated schools were unconstitutional because they violated the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. And like the Briggs case, Virginia's three-judge panel ruled against the 117 students who were identified as plaintiffs in the case. (For more on this case, see Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case .)

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Listed third in the order of arguments, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in February of 1951 by three Topeka area lawyers, assisted by the NAACP's Robert Carter and Jack Greenberg. As in the Briggs case, this case featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs that segregation had a harmful effect on the psychology of African-American children. While that testimony did not prevent the Topeka judges from ruling against the plaintiffs, the evidence from this case eventually found its way into the wording of the Supreme Court's May 17, 1954 opinion. The Court concluded that:

To separate them [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.

Bolling v. Sharpe

Because Washington, D.C., is a Federal territory governed by Congress and not a state, the Bolling v. Sharpe case was argued as a fifth amendment violation of "due process." The fourteenth amendment only mentions states, so this case could not be argued as a violation of "equal protection," as were the other cases. When a District of Columbia parent, Gardner Bishop, unsuccessfully attempted to get 11 African-American students admitted into a newly constructed white junior high school, he and the Consolidated Parents Group filed suit against C. Melvin Sharpe, president of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia. Charles Hamilton Houston, the NAACP's special counsel, former dean of the Howard University School of Law, and mentor to Thurgood Marshall, took up the Bolling case.

With Houston's health already failing in 1950 when he filed suit, James Nabrit, Jr. replaced Houston as the original attorney. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court on appeal, George E.C. Hayes had been added as an attorney for the petitioners, beside James Nabrit, Jr. According to the Court, due to the decision in Plessy , "the plaintiffs and others similarly situated" had been "deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment," therefore, segregation of America's public schools was unconstitutional.

Belton v. Gebhart

The last case listed in the order of arguments, Belton v. Gebhart , was actually two nearly identical cases (the other being Bulah v. Gebhart ), both originating in the state of Delaware in 1952. Ethel Belton was one of the parents listed as plaintiffs in the case brought in Claymont, while Sarah Bulah brought suit in the town of Hockessin, Delaware. While both of these plaintiffs brought suit because their African-American children had to attend inferior schools, Sarah Bulah's situation was unique in that she was a white woman with an adopted Black child, who was still subject to the segregation laws of the state. Local attorney Louis Redding, Delaware's only African-American attorney at the time, originally argued both cases in Delaware's Court of Chancery. NAACP attorney Jack Greenberg assisted Redding. Belton/Bulah v. Gebhart was argued at the Federal level by Delaware's attorney general, H. Albert Young.

Supreme Court Rehears Arguments

Reargument of the Brown v. Board of Education cases at the Federal level took place December 7-9, 1953. Throngs of spectators lined up outside the Supreme Court by sunrise on the morning of December 7, although arguments did not actually commence until one o'clock that afternoon. Spottswood Robinson began the argument for the appellants, and Thurgood Marshall followed him. Virginia's Assistant Attorney General, T. Justin Moore, followed Marshall, and then the court recessed for the evening.

On the morning of December 8, Moore resumed his argument, followed by his colleague, J. Lindsay Almond, Virginia's Attorney General. Following this argument, Assistant United States Attorney General J. Lee Rankin, presented the U.S. government's amicus curiae brief on behalf of the appellants, which showed its support for desegregation in public education. In the afternoon, Robert Carter began arguments in the Kansas case, and Paul Wilson, Attorney General for the state of Kansas, followed him in rebuttal.

On December 9, after James Nabrit and Milton Korman debated Bolling , and Louis Redding, Jack Greenberg, and Delaware's Attorney General, H. Albert Young argued Gebhart , the Court recessed. The attorneys, the plaintiffs, the defendants, and the nation waited five months and eight days to receive the unanimous opinion of Chief Justice Earl Warren's court, which declared, "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place."

The Warren Court

In September 1953, President Eisenhower had appointed Earl Warren, governor of California, as the new Supreme Court chief justice. Eisenhower believed Warren would follow a moderate course of action toward desegregation. His feelings regarding the appointment are detailed in the closing paragraphs of a letter he wrote to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett, a childhood friend (shown above). On the issue of segregation, Eisenhower believed that the new Warren court would "be very moderate and accord a maximum initiative to local courts."

In his brief to the Warren Court that December, Thurgood Marshall described the separate but equal ruling as erroneous and called for an immediate reversal under the 14th Amendment. He argued that it allowed the government to prohibit any state action based on race, including segregation in public schools. The defense countered this interpretation pointing to several states that were practicing segregation at the time they ratified the 14th Amendment. Surely they would not have done so if they had believed the 14th Amendment applied to segregation laws. The U.S. Department of Justice also filed a brief; it was in favor of desegregation but asked for a gradual changeover.

Over the next few months, the new chief justice worked to bring the splintered Court together. He knew that clear guidelines and gradual implementation were going to be important considerations, as the largest concern remaining among the justices was the racial unrest that would doubtless follow their ruling.

The Supreme Court Ruling

Finally, on May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren read the unanimous opinion: school segregation by law was unconstitutional (shown above). Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine exactly how the ruling would be imposed.

Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II (also shown above). It instructed states to begin desegregation plans "with all deliberate speed." Warren employed careful wording in order to ensure backing of the full Court in his official judgment.

The Brown decision was a watershed in American legal and civil rights history because it overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine first articulated in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. By overturning Plessy , the Court ended America's 58-year-long practice of legal racial segregation and paved the way for the integration of America's public school systems.

Despite two unanimous decisions and careful, if not vague, wording, there was considerable resistance to the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education . In addition to the obvious disapproving segregationists were some constitutional scholars who felt that the decision went against legal tradition by relying heavily on data supplied by social scientists rather than precedent or established law. Supporters of judicial restraint believed the Court had overstepped its constitutional powers by essentially writing new law.

However, minority groups and members of the Civil Rights Movement were buoyed by the Brown decision even without specific directions for implementation. Proponents of judicial activism believed the Supreme Court had appropriately used its position to adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times. The Warren Court stayed this course for the next 15 years, deciding cases that significantly affected not only race relations, but also the administration of criminal justice, the operation of the political process, and the separation of church and state.

Parts of this text were adapted from an article written by Mary Frances Greene, a teacher at Marie Murphy School in Wilmette, IL.

The New York Times

The learning network | may 17, 1954 | supreme court declares school segregation unconstitutional in brown v. board of education.

May 17, 1954 | Supreme Court Declares School Segregation Unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education

Historic Headlines

Learn about key events in history and their connections to today.

- Go to related On This Day page »

- Go to related post from our partner, findingDulcinea »

- See all Historic Headlines »

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court issued its landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling, which declared that racially segregated public schools were inherently unequal.

The decision overturned the 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the court ruled that segregation laws were constitutional if equal facilities were provided to whites and blacks. Segregation was therefore justified under the doctrine “separate but equal,” but in few cases were segregated facilities actually equal. The disparity was particularly clear in public schools, where the amount of financing and the standard of education for all-black schools lagged far behind all-white schools.

In 1951, the NAACP recruited families from Topeka, Kan., to take part in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of school segregation. The named plaintiff, Oliver Brown, had a daughter who was forced to take a bus to an all-black school rather than attend the all-white school blocks from her house. The case was combined with similar cases from other parts of the country and argued before the Supreme Court by a team of NAACP lawyers headed by the future justice Thurgood Marshall. The New York Times summarized the NAACP’s case: “Their main thesis was that segregation, of itself, was unconstitutional. The 14th Amendment, which was adopted July 28, 1868, was intended to wipe out the last vestige of inequality between the races, the Negro side argued. … The Negroes also asserted that segregation had a psychological effect on pupils of the Negro race and was detrimental to the educational system as a whole.”

The defense argued that there was nothing in the Constitution outlawing segregation and that therefore it was a matter for the states to decide. The court, in a 9 to 0 decision, sided with the plaintiffs, ruling that segregation violated the clause of the 14th Amendment guaranteeing that states could not “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

In the most famous comment on the case, Chief Justice Earl Warren declared, “In the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

In a separate 1955 case that became known as Brown II, the court ruled that school districts in the 17 states that required segregation and the four that allowed it (including Kansas) integrate their school systems “with all deliberate speed.” The ambiguity of the phrase encouraged many school districts to strongly resist integration, often by shutting down public schools and financing private schools (which were not affected by Brown) for white students. In some places, it took more than 10 years for public schools to become integrated.

Connect to Today:

Even after the implementation of Brown, many schools remained virtually segregated because of neighborhood patterns. In the 1970s, some school districts sought — and some were forced by courts — to achieve a racial balance in schools using tactics like busing students to schools outside their neighborhood. However, in 2007, a divided Supreme Court ruled that public schools “cannot seek to achieve or maintain integration through measures that take explicit account of a student’s race.”

In January 2012, The Times reported on a study by the Manhattan Institute that found that segregation in U.S. neighborhoods had greatly declined and that “the nation’s cities are more racially integrated than at any time since 1910.” While, as the article noted, the findings were generally accepted by a number of experts, some argued that the decline in busing to achieve racial integration has resulted in some public schools that are more segregated than before.

What are your thoughts on the evolution of integration in the United States since Brown? How do you think we should consider the issue of continued school segregation in the context of increased urban integration? Why?

Learn more about what happened in history on May 17»

Learn more about Historic Headlines and our collaboration with findingDulcinea »

Comments are no longer being accepted.

Yes, it was 1954 that the Supreme Court declared school segregation was unconstitutional. Please tell me how Louisiana can still separate boys and girls in there schools here. I have lived in other States and there is not anymore Boys Academy or Girls Academy. The girls schools here do not even have equal rights when it come to getting to have any kind of sports. There are many other reasons but first how can they do this?

Very useful for my school project

An Overlooked Historical Fact about Brown v. Bd of Education The May 16 article, discussing how the decision in Brown v. Bd of Education impacted on the First Lady, “The Decision That Helped Shape Michelle Obama,” overlooked a crucial and critical historical fact. Brown v. Bd of Education actually began with a school bus in Calarendon County, South Carolina. (See Chapter 1, “Simple Justice” by Richard Kluger.) Levi Pearson and three other individuals were seeking money to pay for gasoline for the school bus they and others in their community had privately purchased to transport black children to their segregated school. Their children had been walking 8 to 9 miles one way to get to their school, while white children were passing them on the free public school buses. Pearson volunteered to be the lead plaintiff in Levi Pearson v Clarendon County Bd of Education, signed by attorneys Thurgood Marshall and Harold Boulware. Mr. Levi, posthumously, received the Congressional Gold Medal on Sept. 8, 2004 for his courage to stand up and bring the first desegregation law suit that eventually became, Briggs v. Elliott, and which subsequently became Brown v. Bd of Education. We should never forget those who had the courage to stand up and be counted when such an act could result in their death.

I have a question: What landmark did the supreme court declare that the segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment? This is a church assignment that we have to do, but we can use the internet…

What's Next

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

1954: brown v. board of education.

On May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races to be unconstitutional. The decision dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in public schools and Jim Crow laws, which limited the rights of African Americans, particularly in the South.

Segregation in Schools

Naacp challenges segregation in court, separate, but equal has 'no place', brown v board quick facts.

What is it? A landmark Supreme Court case.

Significance: Ended 'Separate, but equal,' desegregated public schools.

Date: May 17, 1954

Associated Sites: Brown v Board of Education National Historic Site; US Supreme Court Building

You Might Also Like

- brown v. board of education national historical park

- little rock central high school national historic site

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- desegregation

- african american history

- brown v. the board of education of topeka

- public education

Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park , Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

Last updated: July 12, 2023

70 years later, 1 in 3 Black people say integration didn’t help Black students

Landmark Brown. v. Board Supreme Court decision is revered, but Post-Ipsos poll shows mixed feelings about how to address today’s school segregation

Seventy years after the Supreme Court delivered its landmark decision outlawing school segregation, Brown v. Board of Education ranks as perhaps the court’s most venerated decision. A Washington Post-Ipsos survey shows it is overwhelmingly popular.

That’s the simple part. Most everything else related to the decision — and to school segregation itself — is complex.

Nearly 7 in 10 Americans say more should be done to integrate schools across the nation — a figure that has steadily climbed from 30 percent in 1973 and is now at its apex. But a deeper look into the views of both Black and White people shows skepticism about the success of Brown and mixed messages about how to move forward.

In its unanimous decision in Brown , the Supreme Court ruled segregated schools were unconstitutional and “inherently unequal,” combining five cases in which Black students and their schools had far fewer resources than their White peers — longer commutes, lower-quality classes, overcrowding, fewer opportunities and less money. Yet 1 in 3 Black Americans now say integration has failed to improve the education of Black students, a companion Post-Ipsos survey of Black Americans finds.

Today, about half of Black adults favor letting children attend neighborhood schools, even if it means most students would be of the same race — which, given housing patterns, is often the case.

White Americans also sometimes hold conflicting views. Nine in 10 Whites say they support the Brown decision, and nearly 2 in 3 say more needs to be done to integrate schools throughout the nation. Nonetheless, large segments of the White population oppose strategies that would help make that a reality. Nearly 8 in 10 White adults say it is better for children to go to neighborhood schools over diverse ones.

“The Brown decision speaks to our highest ideals as a nation. It’s who we say we want to be as a country,” said Stefan Lallinger, senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a nonprofit that promotes school integration, whose grandfather was part of the team of civil rights attorneys who appeared before the Supreme Court in the Brown case. “Where the rubber meets the road is where people’s personal decisions about where to send their kids to school clash with those ideals.”

The decision, which was issued 70 years ago Friday, continues to hold a special place in American history. On Thursday, President Biden marked the anniversary by meeting with some of the surviving plaintiffs and their families from the five lawsuits that were consolidated into the Brown decision. On Friday, he addressed an NAACP event at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington marking the milestone.

“The Brown decision proves a simple idea. We learn better when we learn together,” Biden said.

The Brown decision focused on the value of mixing children of different races. But for many integration activists — then and now — the case is about a path to fair and equitable educational resources. Those legal battles continue.

Today’s complex views about schools and integration come amid persistent segregation that has risen in recent decades, changes in the legal landscape and the complicated dynamics of education and race in America today.

Because of Brown , school officials may no longer deliberately separate students by race — but under more recent Supreme Court orders, they aren’t allowed to deliberately mix them by race either. Integration advocates today have stopped looking to the federal courts for help and are pursuing state lawsuits instead. And some Black leaders have concluded that the answer is not integration at all but more money and more opportunity for high-poverty schools serving students of color.

“It never worked the way it was supposed to,” said Candace Northern, 43, of Sacramento, who is Black. She had a mixed experience with integration as a child growing up in the area. Now, as mother to four children who went to or will attend public schools, she sees how the system keeps most poor students of color concentrated in certain schools and wealthy, mostly White students in others.

“The intention behind [ Brown ] was good, but it really didn’t make sense to integrate the schools if you were still going to have separate neighborhoods and then only give the resources to the rich people,” she said. “It was more of an appeasement — ‘Let’s give these Black people something so they’ll shut up.’”

The evolution of a landmark ruling

The Brown decision was deeply polarizing, with massive resistance in the segregated South, where federal troops were at times required to escort Black students into what had been all-White schools, and violence in the North, too, as some White parents angrily protested busing orders that federal courts began issuing in the 1970s. Shortly after the 1954 ruling, a Gallup poll found 55 percent of Americans approved of Brown , while 40 percent disapproved.

But it succeeded in diversifying schools, with segregation rates falling through the 1970s and ’80s . Integration peaked around 1988; then courts began lifting their orders, and segregation began to rise again. A majority of Americans wrongly believe that schools are less racially segregated today than 30 years ago, The Post-Ipsos poll finds; in fact, by multiple measures, they are more segregated.

Jackie Beckley was raised in a small town in Kentucky and saw it all up close. Her father had to walk for miles and then travel by train to reach the nearest Black high school because the closer, White schools would not let Black children attend. Born in 1961, Beckley was among the first Black children to be admitted to White schools.

It wasn’t easy for her.

“You’re very much aware of the fact that you’re not like everybody else. You’re different,” she said. She remembered not being chosen as a cheerleader in elementary school despite her excellent gymnastic skills. She knew the reason and if there was any doubt, a White classmate said it out loud: “They didn’t pick her because she’s colored,” he told the class. Students were usually nice to her, she recalled, but if there was an argument, someone might hurl the n-word.

Over time, the Brown decision took on a revered status, one both liberals and conservatives cite as among the Supreme Court’s finest moments. By 1994, 87 percent of Americans approved of the ruling, and the new Post-Ipsos poll finds it just as popular today. But support is lower among Black people — about 8 in 10 say they approve of the decision. Asked if integration had improved the lives of Black students, 75 percent of White people say yes, but a smaller share — 63 percent — of Black people say the same — down from 70 percent in 1994.

Beckley understands why. Her own son attended an integrated school in suburban Columbus, Ohio, where she now lives, but she thinks more funding for schools serving students of color — “so they are educating the kids to the same standard” — is more important than creating diverse schools.

Isaac Heard, 74, is also skeptical after seeing the entire history of school integration unfold before him in Charlotte.

When Heard was growing up in Charlotte, his segregated neighborhood elementary school was so overcrowded that students attended in shifts — either morning or afternoon. “They had decided basically they weren’t going to build any more schools in the Black neighborhoods,” he recalled. His parents sent him to a private Catholic school instead.

Heard returned to public school in ninth grade and the experience was better, though still segregated. His school was economically if not racially diverse, and he recalls the teaching as excellent; in his senior year, four of his teachers had PhDs. He credited the talented Black women who had few career options other than teaching.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C., school district did not fully desegregate until 1970, three years after Heard graduated and went off to Dartmouth College. But once it did, the district gained a reputation for running a successful busing program. In the 1990s, Heard’s own children attended the same district, and he said they received an excellent education.

“The biggest thing is they had role models, and resources were available,” he said. “If they were curious about something, they had access to it.”

Later, working in city planning in Charlotte, Heard saw things change again after the federal court order mandating desegregation was lifted in 1999 and the schools began to resegregate. While some wealthier Black families (including his own) now lived in diverse neighborhoods and attended racially diverse schools, lower-income Black and Hispanic families were concentrated in urban areas and their schools became segregated again .

Heard believes one answer is to spread affordable housing to wealthier neighborhoods, so the neediest students are spread out, but he said these proposals “raised the hackles in this community like you wouldn’t believe.”

Heard’s experience — segregation, integration, and partial segregation again — leaves him with mixed feelings about the impact of Brown . “There’s a generation of kids who really benefited from it, but it’s slowly receding in terms of its positive impact, particularly among lower-income populations,” he said.

A tangle of contradictions

The views of White Americans are also wrapped in contradictions. A wide majority says they support the Brown decision, but many oppose leading ideas for integration today.

Those include adding low-income housing in the suburbs and other high-income areas (43 percent opposed), redrawing boundaries to create more racially diverse districts (45 percent opposed) and requiring schools to bus some students to neighboring districts (70 percent opposed). Only one strategy enjoys support from a large majority (71 percent) — more regional magnet schools with specialized courses (24 percent of Whites are opposed).

Among Black Americans, there is majority support for all four strategies — with at least 7 in 10 backing the proposals for mixed-income housing, redrawing boundaries and magnet schools.

At the same time, nearly 8 in 10 White people say they support “letting students go to the local school in their community, even if it means that most of the students would be of the same race,” while 17 percent favor “transferring students to other schools to create more integration, even if it means that some students would have to travel out of their communities to go to school.”

Elaine Burkholder, 44, who is raising five children in a rural community in central Pennsylvania, did not hesitate when asked her views on Brown . “It was a good decision,” she said. “It’s definitely good to have integration, open the children up to different viewpoints and that sort of thing.”

She said she is not concerned about any segregation that persists today because the law is no longer barring children from going to school together.

“As long as you have the ability to move and stuff you can probably get your children into a decent school district,” she said. “It’s pretty well a personal choice at this point, where your children go to school.”

Burkholder, whose children attend a private Christian school, was not particularly concerned that some families cannot afford to move to another school district. “I’m a little more of a pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” Burkholder said. “I like to see people working to get where they want to go.”

The way forward

The contradictions inherent in public opinion have given rise to conflicting strategies about what should come next.

David Banks, the chancellor of the New York City schools, the nation’s largest school system, who is Black, attended integrated schools in Queens as a child but does not see integration as the answer for children in New York City today. Today, 24 percent of the students in the city schools are Black, and 41 percent are Hispanic. Just 15 percent of students are White. He said the path to a better education for a student of color cannot be sitting next to a White student; there aren’t enough White students to go around.

“I do not believe Black kids need to go to school with White kids to get a good education. I fundamentally reject that,” he said in an interview.

Instead of integration, Banks favors directing more money and adding programs to high-poverty schools serving students of color and providing more opportunities for advanced coursework in low-income areas.

But others say students of color will never get what they need if so many are isolated in high-poverty school districts. A new generation of legal advocates is now targeting the boundary lines that separate school districts, which drive most of the racial and economic segregation today.

They’ve also shifted legal strategy. Supreme Court rulings issued in the years since Brown make success in federal courts unlikely, they say, so unlike their counterparts from past decades, they are focused on state courts.

A lawsuit in New Jersey is challenging district boundary lines based on a provision in the state constitution. The parties have been negotiating for months in hopes of reaching a settlement. Another case challenging segregation in the Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minn., schools has been working its way through the Minnesota courts for nearly a decade. A lawsuit in New York City relies on the state constitution to challenge admissions policies that place students into gifted and advanced programs, creating a two-tiered education system that hurts Black and Hispanic students.

A new organization called Brown’s Promise is looking for other potential lawsuits, possibly based on state constitutions that guarantee a “thorough and efficient” public education.

“Any meaningful definition of a ‘ thorough education’ has to mean learning to live, work and thrive in a multiracial community,” said Ary Amerikaner, co-founder of Brown’s Promise.

She pointed to research that shows the post- Brown integration years succeeded in raising achievement levels of Black students.

“We cannot keep concentrating poverty in a small number of districts and expecting the adults to work miracles,” she said. She said it’s worth fighting for more money for these schools — adding that a little more money probably won’t help, but a lot more would.

“But even that cannot create the sort of social capital that we know comes from access to communities that are historically more privileged.”

The Washington Post-Ipsos poll of 1,029 U.S. adults was conducted April 9-16 and included a partially overlapping sample of 1,331 non-Hispanic Black adults. The margin of sampling error among Americans overall and Black Americans is plus or minus 3.2 percentage points; among the 703 White Americans the margin of error is 3.9 points.

Skip to main content

- Life & style

- Environment

Brown vs. Board of Education: Here’s what happened in 1954 courtroom

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

E DITOR’S NOTE: On May 17, 1954, a hushed crowd of spectators packed the Supreme Court, awaiting word on Brown vs. Board of Education, a combination of five lawsuits brought by the NAACP’s legal arm to challenge racial segregation in public schools. The high court decided unanimously that “separate but equal” education denied black children their constitutional right to equal protection under the law, effectively removing a cornerstone that propped up Jim Crow, or state-sanctioned segregation of the races.

Associated Press reporter Herb Altschull chronicled the decision and what it meant for segregation, which in 1954 permeated many aspects of American life. Using the style and language of journalists of his era, including a reference to Asians as “Orientals,” Altschull captured the uncertainty hanging over a society on the brink of seismic change. H ere is Altschull’s compelling report.

The Supreme Court ruled today that the states of the nation do not have the right to separate Negro and white pupils in different public schools.

By a unanimous 9-0 vote, the high court held that such segregation of the races is unconstitutional.

Chief Justice Warren read the historic decision to a packed but hushed gallery of spectators nearly two years after Negro residents of four states and the District of Columbia went before the court to challenge the principle of segregation.

The ruling does not end segregation at once. Further hearings were set for this fall to decide how and when to end the practice of segregation. Thus a lengthy delay is likely before the decision is carried out.

Dean Acheson, secretary of State under former President Harry Truman, was in the courtroom to hear the ruling. He called it “great and statesmanlike.”

Atty. Gen. [Herbert] Brownell was also present. He declined comment immediately. Brownell and the Eisenhower administration, like Truman’s, opposed segregation.

For years 17 Southern and “border” states have imposed compulsory segregation on approximately two-thirds of the nation’s Negroes. Officials of some states already are on record as saying they will close the schools rather than permit them to be operated with Negro and white pupils in the same classrooms.

In its decision, the high court struck down the long-standing “separate but equal” doctrine first laid down by the Supreme Court in 1896 when it maintained that segregation was all right if equal facilities were made available for Negroes and whites.

Here is the heart of today’s decision as it deals with this hotly controverted doctrine:

“We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal education opportunities?”

“We believe that it does.”

James C. Hagerty, presidential press secretary, told a news conference the White House would have no comment at this time. He noted that Warren’s opinion said formulation of specific decrees must await later hearings.

Gov. Herman Talmadge, one of the most outspoken supporters of segregation, hit back from Atlanta that the court’s decision had reduced the constitution to “a mere scrap of paper.”

“It has blatantly ignored all law and precedent and usurped from the Congress and the people the power to amend the Constitution and from the Congress the authority to make the laws of the land,” Talmadge said.

Thurgood Marshall, Negro attorney from New York who had argued the case against segregation last December, said he was highly pleased that the decision was unanimous and that the language used was unequivocal.

“Once the decision is made public to the South as well as to the North,” Marshall said, “The people will get together for the first time and work this thing out.”

He said he was not in any way fearful lest the final decree nibble away at the principles in the decision. Marshall said, too, he believes the people of the South will abide by the ruling. “The people of the South are just as law abiding as any other good citizens,” he said.

Marshall is a special counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which has spearheaded the drive against segregation. He said NAACP people will meet this week to discuss “what we are going to do.”

Today’s decision was the first major ruling of the Supreme Court since Warren became chief justice last October, succeeding the late Fred Vinson.

The court confined its ruling to the question of the segregation of Negro public school pupils, but it obviously is applicable to the exclusion from public schools of any minority group -- Orientals, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and so on.

Today’s decision was the latest in a series of court rulings wiping out legal restrictions on Negroes.

In previous cases the Supreme Court had:

1. Ruled that colleges must admit Negroes to study professional courses not open to them in Negro colleges.

2. Ruled that Negroes may not be excluded from train and bus coaches operated in interstate travel.

3. Ruled that Negroes may not be barred from eating in restaurants in the District of Columbia.

The “separate but equal” doctrine was set forth in a 7-1 decision on May 18, 1896, in a case involving Homer Adolph Plessy, who was part Negro.

Plessy boarded a train for a ride from New Orleans to Covington, La., and took a seat in a coach assigned to white passengers in violation of a Louisiana law which required segregation of whites and Negroes on trains.

The conductor asked Plessy to leave the white coach but he refused. A policeman arrested Plessy and took him to jail in New Orleans.

That set off a vigorous legal battle in which the Louisiana Supreme Court eventually upheld the state law. Plessy appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States and the decision went against him.

Justice Henry Billings Brown, who wrote that decision, said the Louisiana law was not in conflict with the U.S. Constitution since Plessy was not refused the right to ride in trains so long as he stayed in a coach restricted to Negroes.

Thus grew up the philosophy of “separate but equal” facilities. Warren, in today’s decision, wrote that the Plessy case involved transportation, not public schools. Inasmuch as he called special attention to the distinction, it is apparent that the court is not now dismissing all forms of segregation.

Warren said that when the 14th Amendment was enacted, “education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states.”

“Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences as well as in the business and professional world.”

Warren noted that in the early 1870s when cases dealing with segregation first went to the Supreme Court, “compulsory education was virtually unknown” and that for this reason the question of school segregation was unimportant.

After the 1896 decision, Warren wrote, American courts began using it as a basis for decisions on all matters dealing with separation of Negroes and whites.

But it was not until the present cases were brought before the court, Warren said, that the “separate but equal” doctrine was challenged insofar as it might deal with public school education.

Warren noted that the lower courts, in finding against Negro appellants on the basis of the 1896 decision, maintained that the Negro and white schools involved had, in fact, been equalized “with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers and other ‘tangible’ factors.”

But, the Chief Justice said, “our decision. cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.”

The Warren opinion recalled that in an earlier decision dealing with the question of whether Negroes should be admitted to graduate courses in segregated universities, the court had said this:

“To separate them (Negroes) from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.”

Reaction from Capitol Hill was swift and in some cases strongly critical.

Sen. [Richard] Russell of Georgia, leader of Southern Democrats in the Senate, termed the decision “a flagrant abuse of judicial power.” He said questions like that of segregation should be decided by the lawmakers, not the courts.

Other Southerners were plainly unhappy, but they did not go so far as Russell. Sen. [Marion Price] Daniel (D-Texas) said the verdict was “disappointing” and that he couldn’t see how the court could arrive at such a decision.

Sen. [Allen J.] Ellender (D-La.) said, “I am of course very much disappointed by this. But I don’t want to criticize the Supreme Court. It is bound to have a very great effect until we readjust ourselves to it.”

He said there would be “violent repercussions” if enforcement were ordered too quickly.

Rep. [Kenneth B.] Keating (R-NY), a strong backer of civil rights legislation, said “There is no doubt about the soundness of the court’s decision.”

Gov. William B. Umstead of North Carolina said in a statement put out by his office that he was “terribly disappointed.”

J.M. Hinton, South Carolina conference president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), said:

“Christianity and democracy have been given a great place in America through the elimination of segregation in public school and communism has lost a talking point.”

The appeals from the four states - Kansas, Delaware, Virginia and South Carolina - challenged the legality of segregation on the ground that it violated the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. The District of Columbia complaint alleged violation of the 5th Amendment.

The 14th Amendment, put through shortly after the end of the Civil War, was designed to reinforce the rights of the newly freed slaves. It said that no state may deprive any person of due process or equal rights under the law.

The 5th Amendment gives all persons involved in court cases dealing with federal matters the right to due process of law.

Actually, the court did not decide the question purely on the basis of these amendments.

Warren wrote that the court “cannot turn the clock back” to the enactment of the 14th Amendment in 1868 or the imposing of the “separate but equal” doctrine in 1896.

“We must consider public education,” Warren wrote, “In the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the nation. “

“Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.”

“Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments... It is the very foundation of good citizenship... In these days it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education.”

“Such an opportunity where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”

The court minced no words in applying the “equal rights” section of the 14th Amendment to the issue of school segregation. It said: