What Can We Learn from Violent Videogames?

Fears that violent videogames will cause people to be more violent are understandable, but unsupported by current research — social and developmental factors are better predictors of violent behavior. In fact, some violent videogames may actually lead to the development of empathy, understanding, and even moral behavior.

On October 1, 2015, a gunman walked into his classroom at Umpqua Community College and methodically began murdering his classmates one-by-one. It feels as if these kinds of mass violence are becoming more common. Columbine (1999). Virginia Tech (2007). Fort Hood (2009). Aurora (2012). Newtown (2012). Fort Hood (again: 2014). Charleston (2015). Those are just the ones most people remember; they don't include the other 34 mass shootings since 1984. Collectively, these mass shootings have claimed 372 lives and injured 412, not including the immeasurable injury done to the families and communities of those murdered.

Just as these events seem to be becoming more commonplace, the tenor of the discussions they prompt have also fallen into a routine. Why did it happen? What can we do to prevent it? In our search for answers, it is only natural that we look for definitive explanations to make sense of the incomprehensible. Was the shooter angry? Taking revenge? Mentally ill? On drugs?

Did the shooter play videogames?

It might seem odd to mention this last question in the same breath as the others, but it is in part because of these mass murders that one of the constant themes in the academic, political, and social debate about videogames in popular culture has been whether and to what extent violent videogames promote aggressive behavior. This debate has been around longer than videogames, however, having surfaced first with film (1900s) and radio (1930s), 1 then comic books (Fredric Wertham's 1954 Seduction of the Innocent , which led to the formation of the Comic Code Authority that same year) and later television (The Family Viewing Hour, a policy overturned by the courts in 1977). Seen in this context, videogames are just the latest media to raise age-old concerns.

Our tendency to view new media with suspicion is a good thing; many would argue that we do not do enough of this now with the shift to a digital economy (e.g., Jeron Lanier's Who Owns the Future ), our use of social media (e.g., Jon Ronson's So You've Been Publicly Shamed ), our loss of privacy and control of our genetic code, and the abuse of social media by employers and law enforcement (e.g., Lori Andrews' I Know Who You Are and I Saw What You Did ), or the spiritual and humanistic implications of technology (e.g., Noreen Herzfeld's In Our Image ). Yet, this tendency to overgeneralize can also blind us to the potential benefits of new media and even prevent us from understanding the way that media may in fact lead to the very outcomes we fear.

This article is based on three premises:

- First, questions about the impact of violent media on behavior are legitimate; we should be critical of the messages we consume and which we put in front of our children.

- Second, our policies and decisions in this regard should be based on evidence rather than anecdotal or conventional wisdom.

- Third, we should strive to be as open to the potential for videogames to promote positive attitudinal and behavioral outcomes as we are to their negative consequences. This is true even (and in some cases, especially) for violent videogames.

The first two premises are related, so I will start with what we do know about whether videogames increase violent behavior.

Do Games Teach Violence and Aggression?

Several good publications help introduce this complex area of study, 2 and I will highlight some of the key findings here. We must start by examining our common beliefs about popular culture media (like videogames) and aggression. In the case of media and violence, the common-sense theory posits that the more you experience violence, the more likely you will become violent. This assertion, however, is not borne out by the literature. Human beings are not passive receptors but active processors of our environments. We continually strive to "make sense" of the messages around us, placing them in social, emotional, cultural, and political contexts. This is why commercial advertisements do not necessarily lead us to purchase the advertised product and why, despite having watched hundreds of hours of The Three Stooges and The Road Runner , I (and thankfully, most other people) have yet to poke my family or friends in the eyes or drop anvils on them from a great height. However, this also explains why people who have trouble distinguishing fantasy and reality, who cannot regulate their emotions, or who lack social/emotional awareness 3 may also be more likely to seek out violent media or to act out in violent ways. This points out another weakness of studies that have found correlational associations linking violence and media consumption: they do not control for other explanatory factors. For example, boys are disproportionately attracted to videogames and more likely to act aggressively than are girls. Thus, correlational studies might document this sex–aggression relationship or other "hidden" correlations rather than media–aggression effects. 4

In Schwarzenegger (later, Brown) vs. Entertainment Merchants Association and Entertainment Software Association (ESA), the ESA sued to overturn a State of California law that restricted the sale of violent videogames to minors. California contended that it had the right to protect the health and well-being of minors, while the ESA contended that the lack of a causal link between violent media, including videogames, made the issue one of free speech. This case might represent the best-informed public debate to date on the issue of violent videogames and aggression. Amicus briefs filed on both sides of the case pulled all the relevant research known at the time and subjected it to intense scrutiny and debate. Among the dozens of briefs filed on behalf of the ESA was an amicus brief authored by a coalition of states and territories and 82 psychologists, criminologists, medical scientists, and media researchers, 5 all of whom contended that the State of California had misrepresented the science on videogames and that there was no causal link in the research. Ultimately, the argument by the ESA won out, first in District Court, later on appeal in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and finally in the U.S. Supreme Court. Each court ruled that there was insufficient evidence of a causal link between violent videogames (or any media, for that matter) and violent behavior or aggression.

This complex case involved many different issues and arguments, but the Supreme Court's 7-2 ruling hinged in three main points: videogames, "like the protected books, plays, and movies that preceded them…communicate ideas…" which "suffices to confer First Amendment protection; that current rating systems are sufficient to prevent minors from purchasing mature games and that…filling the remaining modest gap in concerned-parents' control can hardly be a compelling state interest." Moreover, there was no "compelling" link between violent videogames and aggression or violence in children.

Many are uncomfortable with the free speech component of the decision; when it comes to our children, safety feels more important than free speech (consider our views on cyberbullying today as a case in point). The second point is perhaps a bit more palatable because it seems to strike a balance between regulation (albeit self-imposed, and with at times questionable definitions of what qualifies a game for a rating of "Teen" vs. "Mature") 6 and parental control. Ultimately, no law can substitute for parental involvement in what their children consume and, more importantly, what meaning they make from it. Still, wherever you come down on this issue as a parent, teacher, administrator, politician, or citizen, the third point is the most salient and should serve to remove any qualms we have over the first two issues: There is no compelling evidence linking videogames (or TV, movies, magazines, plays, or books) to violence and aggression in children.

This case illustrated the error, to which people on both sides of the debate are prone, of oversimplification. The case ultimately hinged on whether evidence exists for the "dosing" model of violence and aggression. The dosing model holds that the presence of violence (any kind) leads to violent behavior, and that the more violence one is exposed to (time, intensity), the more likely one is to become more violent. As the hundreds of sources cited in the above-referenced amicus brief illustrates, the dosing model is too simplistic to predict violence or aggression. Teen violent crime has actually decreased over the last 20 years at the same time that videogame play has increased. If one plots the number of per capita gun-related murders against per capita spending on videogames, several interesting things become apparent. First, only China spends less per capita (~$5) on videogames than the United States (~$42); Germany, Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom, France, and Canada spend $45–$65, while South Korea and the Netherlands spend more than $100 per capita. Yet the United States has three times more gun murders than any other country, including South Korea (zero murders per 100,000) and the Netherlands (0.4 per 100,000). See table 1.

Table 1. Rank-ordered list of top 10 countries by videogame sales and corresponding gun homicides per capita*

| Country | Videogame Sales Per Capita* | Gun Homicides Per Capita** |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | $47.00 | 0.01 |

| South Korea | $102.00 | 0.03 |

| USA | $42.00 | 2.97 |

| UK | $60.00 | 0.05 |

| France | $62.00 | 0.06 |

| Canada | $60.00 | 0.51 |

| Australia | $48.00 | 0.10 |

| Germany | $43.00 | 0.19 |

| Netherlands | $110.00 | 0.33 |

| China | $0.00 | 0.00 |

* New Zoo Games Market Research ** United National Office on Drugs and Crime: Global Study on Homicide (2013)

Mass Shootings and Videogames

This has not stopped us from looking to videogames in our painful search to explain tragedies like Columbine, Aurora, Virginia Tech, and Sandy Hook. The killers responsible for the murders at Columbine, Aurora, and Sandy Hook reportedly played a lot of videogames, although the shooter at Virginia Tech did not. Yet, the Sandy Hook killer mostly played nonviolent games (he spent the most time playing Super Mario Brothers and Dance Dance Revolution ), and the shooter at Aurora played mostly role-playing games (fantasy-based games that feature armed combat against primarily monsters) like World of Warcraft , Neverwinter Nights , and Diablo , which do not feature guns. Of all the perpetrators of these horrific mass shootings, only the Columbine shooters actually played games that involve using guns to shoot people. The more common thread? All were mentally ill at the time of the shootings and all had access to guns. And, by the way, less than eight percent of violent crime committed by the mentally ill is the direct result of their mental illness, lest we commit another overgeneralization about causes of violence. 7

Videogames could have been part of their illness, of course. Suffering from a serious psychosis conceivably could lead to seeking out experiences and media that reinforce that psychosis and color one's perceptions of what those experiences mean. But it is another thing entirely to reverse the order and suggest that the medium or the experiences caused the illness. Being around young children does not cause people to become pedophiles; being a pedophile makes people seek out environments with young children.

Laboratory Studies vs. Real Life

Virtually every piece of research showing a link between media such as videogames and aggression comes from laboratory settings in which conditions are carefully controlled and in which aggression is measured by paper-and-pencil statements about aggression, not actual aggression. As such, the most we can conclude from these studies is that under some conditions, we can create people who self-report as more aggressive; there is no evidence that those people then go out and behave any differently as a result. The largest-scale meta-analysis to report a link between videogames and aggression included only a few studies with real-world incidents of aggression, and those relied on self-reported measures of aggression rather than observed acts. 8 The authors concluded that "These are not huge effects — not on the order of joining a gang vs. not joining a gang. But it is one risk factor for predicting future aggression and other negative outcomes" (emphasis added).

People do not exist in laboratories; we exist in societies and cultures with complex social systems of rules, expectations, and messages that ameliorate violence-tinged media messages. The vast majority of us can navigate these waters without becoming violent, a fact made evident by the lack of increased violent crime in those who read Grimm's Fairy Tales (stuffing witches in ovens, chopping people up, cannibalism), watched the Looney Tunes , or enjoyed The Three Stooges . Clearly, and thankfully, the relation between violent media messages and violent behavior is more complex and less direct than we fear.

One Small Factor

My argument is not that violent media cannot lead to violent behavior, only that the ways in which it does (and does not) are complex and nuanced. After all, videogame researchers like me can hardly argue that videogames can promote positive behaviors if we are not willing to acknowledge the conditions under which they can lead to undesired behavior as well. So what is the truth that lies between these two positions? We do not (yet) know enough about human beings to provide a definitive answer to this question. No one would disagree that it is possible to create a violent human being by exposing him or her to long-term, consistent messages of violence without any socialization to counteract it; we need only look to the tragic cycle of familial and domestic violence for evidence of that.

If we believe the evidence that suggests games can desensitize those with crippling phobias to the stimuli that trigger their feelings of panic, we can hardly argue that media cannot also desensitize someone to violence. By the same token, however, we must recognize that all the evidence we have shows that media do not desensitize most people. We should not accept that violent videogames (or any other medium) are anything but one small factor in a complex societal issue.

The Right Question

The question we should ask is not whether violent videogames can make people violent — they can, under the right circumstances. That set of circumstances is poorly understood, however, and thankfully quite rare. The real question of interest lies in determining the circumstances and mechanisms by which such changes can occur. This is much more than an academic pursuit; it has the potential to change our society in ways we cannot yet imagine. By asking how instead of whether or if games can create such sociological and behavioral changes, we shift the focus from a dosing model (exposure = change) to a social/cultural/cognitive/emotional explanation of how and under what circumstances beliefs and actions can be changed.

In retrospect, it seems obvious that context determines how people process media messages. For example, we already recognize that violence committed in self-defense is different than unprovoked violence. We provide social venues in which violence is not just allowed, but encouraged (e.g., MMA and American football) — violence that would result in arrest if demonstrated in other social contexts. If we recognize that the context of the violence makes a difference in these examples, we must also accept that violent videogames are subject to the same contextual influences.

Context does not just reduce the likelihood of becoming more aggressive as a result of violent media; it can actually result in positive behavioral outcomes. Research spanning the last 25 years has found that playing a violent videogame with another player (not against them) actually reduced aggression and increased prosocial behavior, 9 has provided evidence of a kind of cathartic effect for violent videogames (players are less aggressive after taking on the role of an avenging assassin in a videogame), 10 and that those who played an automobile racing game were more aggressive (as measured by biometric measures of arousal rather than paper-and-pencil tests) than those who played a shooter game in which they had to kill other human beings. 11 The researchers in the latter study hypothesized that the racing game tapped into real experiences (e.g., road rage, near accidents), whereas players had no related cognitive–emotional experiences to tap into with the shooting game.

Do Videogames Have Special Powers?

Many studies like those described here highlight the importance of the psychological, cognitive, and emotional characteristics of the individuals who consume the media and their social contexts. In this respect, videogames enjoy a distinct advantage over books and movies as media. In life, we are limited to our own experiences; our ability to develop empathy, tolerance, and a strong moral compass are limited to those experiences and the meaning we make within our social contexts. Books and movies, on the other hand, can provide a potentially unlimited set of experiences to make sense of and thus can build empathy through exposing us to virtual experiences of other people who think, act, and behave in ways different from us. The knowledge we gain in the process, by seeing that the ways "different" people, look, sound, and behave does not necessarily lead to "better" or "worse" people, can make us more tolerant and understanding of diversity.

Movies, as a kind of visual storytelling, seem to work in the same way as books; movies like Sophie's Choice (based on the book by the same name) would not work if the viewer did not identify with her in spite of the horrific act of filicide. Yet movies create a layer between the viewer and the medium by forcing a representation of place, time, and characters on the viewer, whereas books force the reader to generate these things. This cognitive act invests the reader in the narrative in some ways more deeply than film can and does so in ways that are correspondingly more connected to our own experiences (since we are most likely to generate people, places, and spaces like those we have experienced). Books also allow us to pause and reflect on decisions that characters make with which we may disagree or find unpalatable, whereas movies are time-based (remote controls notwithstanding) and proceed at their own pace, with less time to consider what we would do next. In both cases, however, we do not really have any control over what happens, and that means we can never really develop a full appreciation of the consequences of one decision over another. We might be sure that we would decide differently ourselves, but without the ability to try, we cannot know how we would feel or come to believe. Videogames do not suffer from this limitation — they allow us to experience both sides of a decision through replayability. Because videogames are dynamic, our choices lead to different outcomes and possibilities, thus promoting a desire to replay.

Can Violent Videogames Make Us More Moral?

In well-defined moral and ethical situations, the inability to experience both sides of an ethical or moral dilemma may have less consequence than with morally and ethically ambiguous situations. What happens, for example, when the protagonist in a book or movie commits acts considered unethical or immoral? Whether "justified" by the context (e.g., revenge, self-preservation), we wonder how we would have behaved and, more importantly, how we would have felt about making each choice. Our sense of morality is developed, in part, through exposure to dilemmas, our exploration of the possible choices, and our evaluation of the consequences of those choices, which involves our emotional responses.

By allowing us to choose what "we" do as the main character, videogames offer us the opportunity to explore all sides of such dilemmas, to experience the results of our choices through observable consequences in the game world, and to evaluate our own reaction to them. 12 This sense of agency, combined with directly observable consequences and replayability, makes videogames just as effective at promoting morality and ethics as for promoting violence. Dozens of digital game-based learning (DGBL) researchers work in this area, 13 but one example shared with me by my colleague, Bob DeSchutter, is illustrative.

In the game Fallout 3 , a post-apocalyptic world destroyed by nuclear war, one of the side quests leads to a community that has evolved for many generations in an isolated environment. At the center of their culture is a tree that holds religious significance for them. This tree turns out to be a human mutant, Harold, who is trapped inside this tree, which began growing out of his head many years ago and in which he is now completely encased. When the player meets Harold, he begs to be put out of his physical and spiritual misery. The community, however, believes such requests are spiritual tests, which they have ignored for years. The community wants Harold's bounty and wisdom (he has given birth to a rich ecosystem) to be spread across the world. The player can choose to commit murder in order to end Harold's suffering, knowing that doing so will also remove the spiritual center of a culture and guarantee the rest of the world remains barren. Or, the player can choose the good of the community, thus ensuring that Harold's torture will never end. There is no right or wrong answer to such moral dilemmas, and forcing the player not just to contemplate the decision but to actually make it and see (and feel) the results is a powerful experience not possible in other media. Because players can replay the scenario and choose differently, they can also explore both sides of the issue; what the game designers then program in as the consequences can play a significant role in helping to make meaning of the experience from a societal perspective.

What (Else) Can We "Learn" from Videogames?

The potential for videogames to promote positive behavioral outcomes is not limited to morality or ethics. Researchers like Ian Bogost, with his work on persuasive games, have shown how games can help us understand complex social problems from a personal perspective and make us more empathetic. For example, his game Fat World places the same geographic and economic constraints on the player as experienced by those who live in poor urban areas. Without access to reliable transportation, players are limited to food in their immediate surroundings, which comprise neighborhood shops with fewer healthy options and a significantly higher-per-capita presence of fast-food restaurants. With price disparities between healthy and unhealthy food and a limited food stamp budget, players must choose whether to buy high quantities of inexpensive, unhealthy food to last their family for a week or more expensive healthy food that may last only a few days. Thus, the game play shows how obesity and diabetes do not necessarily result from conscious choices or lack of willpower, but from complex socio-demographic factors beyond the control of individuals.

In a similar vein, researchers like Pam Kato have shown how games can make us healthier and live longer. Her game, Re-Mission , helped children with cancer understand the effects of their chemotherapy on their cancer (by letting them travel throughout their bodies and "kill" cancer cells using guns that deliver chemotherapy agents) and resulted in significantly higher adherence to their chemotherapy programs. This and hundreds of other studies and researchers have given rise to a field of study called games for health, with its own conferences, journals, and organizations.

Researchers like Jane McGonigal have shown how alternate reality games (ARGs), games that mix the real world with virtual components, can solve social problems. Her games Evolve (identifying and solving local social problems) and World Without Oil (finding solutions to the world's future energy needs) and those of hundreds of other researchers have resulted in millions of people voluntarily working to find solutions to a wide range of social problems.

Researchers like Bob DeSchutter, founder of the Gerontoludic Society, are building games for the elderly, not for cognitive training purposes (which have received dubious empirical support) but for ethical, quality-of-life, and aesthetic reasons. His games and projects have promoted intergenerational familial connections by supporting shared storytelling and shared game play and broadened the already significant games-for-aging arena. And virtual worlds like Snow World (a game for burn victims that has been clinically shown to improve pain management) and an NIH-funded clinical trial of another game shown to reduce PTSD symptoms 14 have extended the power of game technology to the counseling and therapy domains.

Concluding Thoughts

Once again, my argument is not that violent videogames cannot promote aggressive behavior, nor that their ability to promote positive outcomes outweighs that risk. The mere presence of violence in a videogame, however, is insufficient to make any judgment about its potential for good or harm. If we accept that videogames can promote negative outcomes, we must also accept that the opposite is also true. Just as our technologies and definitions of learning have evolved, so must our research questions and practices continue to change. If we are honest with ourselves, we have known for some time that the answer to whether violence in any medium is "good" or "bad" is "it depends." It depends on a variety of social, developmental, emotional, and contextual factors. It depends on the set of circumstances that each person, as an active participant in the meaning-making process, brings to the table. It depends on things we have not yet discovered. In defining these conditions and factors, we will have to leave our preconceived notions and prejudices behind and accept that positive and negative effects may result from "good" or "bad" media. If we fail to remain open to all such possibilities, even those that go against our personal beliefs, we put at risk the very outcome we are trying to achieve — a more just, fair, and moral world for future generations. If we succeed, videogames (even, or perhaps especially, violent ones) may help point the way to a better world.

- Ellen Wartella and Byron Reeves, "Historical trends in research on children and the media: 1900–1960," Journal of Communication, Vol. 35 (Spring 1985): 118–33.

- Craig A. Anderson, Akiko Shibuya, Nobuko Ihori, Edward L. Swing, Brad J. Bushman, Akira Sakamoto, Hannah R. Rothstein, and Muniba Saleem, " Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta-analytic review ," Psychological Bulletin , Vol. 136, No. 2 (March 2010): 151–173; Christopher J. Ferguson, Violent Crime: Clinical and Social Implications (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010); and Christopher John Ferguson, "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: A Meta-analytic Review of Positive and Negative Effects of Violent Video Games," Psychiatric Quarterly , Vol. 78, No. 4 (December 2007): 309–316.

- Because of mental or developmental disability or mental illness, for example. See Richard J. Davidson, Katherine M. Putnam, and Christine L. Larson (2000). " Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation—A possible prelude to violence ," Science, Volume 289, No. 5479: 591–594.

- E.g., Christopher J. Ferguson, John Colwell, Boris Mlačić, Goran Milas, and Igor Mikloušic, "Personality and media influences on violence and depression in a cross-national sample of young adults: Data from Mexican-Americans, English and Croatians," Journal of Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 27, No. 3 (May 2011): 1195–1200.

- Court brief of social scientists, medical scientists, and media effects scholars as amici curiae in support of respondents.

- I've seen one case where a game earned a rating of Teen for "comic mischief" involving throwing ice cream at your friends, while a recent Batman title earned the same rating despite portraying frequent, personal beatings (including personal strangulation and head stomps) of bad guys and a dirty-talking Catwoman with her suit unzipped to show significant cleavage.

- Jillian K. Peterson, Jennifer Skeem, Patrick Kennealy, Beth Bray, and Andrea Zvonkovic, " How often and how consistently do symptoms directly precede criminal behavior among offenders with mental illness? " Law and Human Behavior, Vol. 38, No. 5 (October 2014): 439–449.

- See note 2.

- S. B. Silvern, P. A. Williamson, and T. A. Countermine, "Video game play and social behavior: Preliminary findings , " paper presented at the International Conference on Play and Play Environments (1983b).

- Christopher J. Ferguson and Stephanie M. Rueda, " The Hitman study: Violent Video Game Exposure Effects on Aggressive Behavior, Hostile Feelings, and Depression ," European Psychologist , Vol. 15 No. 2 (2010): 99–108.

- Sarah L. Pearson and Simon Goodson, "Video games and aggression: Using immersive technology to explore the effects of violent content," Proceedings of the North East of England Branch of the BPS Annual Conference , June 26–27, 2009, Sheffield, UK.

- This might be more accurately characterized as co-authoring, since the design decisions made by the game designers also control and constrain the narrative.

- Karolien Poels and Steven Malliet, eds. Vice city virtue: Moral issues in digital game play (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2011); and Jose P. Zagal, "Ethically Notable Videogames: Moral Dilemmas and Game Play," Breaking new ground: Innovation in games, play, practice and theory, Proceedings of the 2009 DiGRA conference (2009).

- Daniel Pine, MD, of the NIMH Emotion and Development Branch, Yair Bar-Haim, PhD, School of Psychological Sciences, Tel Aviv University, and colleagues, report on their findings July 24, 2015, National Institute of Mental Health .

Richard Van Eck is associate dean for Teaching and Learning and the founding Dr. David and Lola Rognlie Monson Endowed Professor in Medical Education at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences. He has studied digital games since his doctoral studies at the University of South Alabama, where he worked on two award-winning science and problem-solving digital games (Adventures in Problem Solving and Ribbit’s Big Splash). His recent work has included consulting on evaluation and game design on several digital STEM games, including PlatinuMath, Project NEO, Project Blackfeather, and Contemporary Studies of the Zombie Apocalypse. He is a frequent keynote speaker and author on the educational potential of videogames at such venues as TEDx Manitoba and SXSW. He also publishes and presents on intelligent tutoring systems, pedagogical agents, authoring tools, and gender and technology.

© 2015 Richard N. Van Eck. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license

Recent Blog Articles

How well do you score on brain health?

When should your teen or tween start using skin products?

How — and why — to fit more fiber and fermented food into your meals

Protect your skin during heat waves — here's how

Respiratory health harms often follow flooding: Taking these steps can help

Want to cool down? 14 ideas to try

A fresh look at risks for developing young-onset dementia

Are you getting health care you don't need?

Weighing in on weight gain from antidepressants

Dengue fever: What to know and do

Violent video games and young people

Experts are divided about the potential harm, but agree on some steps parents can take to protect children..

Blood and gore. Intense violence. Strong sexual content. Use of drugs. These are just a few of the phrases that the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) uses to describe the content of several games in the Grand Theft Auto series, one of the most popular video game series among teenagers. The Pew Research Center reported in 2008 that 97% of youths ages 12 to 17 played some type of video game, and that two-thirds of them played action and adventure games that tend to contain violent content. (Other research suggests that boys are more likely to use violent video games, and play them more frequently, than girls.) A separate analysis found that more than half of all video games rated by the ESRB contained violence, including more than 90% of those rated as appropriate for children 10 years or older.

Given how common these games are, it is small wonder that mental health clinicians often find themselves fielding questions from parents who are worried about the impact of violent video games on their children.

The view endorsed by organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) is that exposure to violent media (including video games) can contribute to real-life violent behavior and harm children in other ways. But other researchers have questioned the validity or applicability of much of the research supporting this view. They argue that most youths are not affected by violent video games. What both sides of this debate agree on is that it is possible for parents to take steps that limit the possible negative effects of video games.

In its most recent policy statement on media violence, which includes discussion of video games as well as television, movies, and music, the AAP cites studies that link exposure to violence in the media with aggression and violent behavior in youths. The AAP policy describes violent video games as one of many influences on behavior, noting that many children's television shows and movies also contain violent scenes. But the authors believe that video games are particularly harmful because they are interactive and encourage role-playing. As such, the authors fear that these games may serve as virtual rehearsals for actual violence.

Both the AAP and AACAP reason that children learn by observing, mimicking, and adopting behaviors — a basic principle of social learning theory. These organizations express concern that exposure to aggressive behavior or violence in video games and other media may, over time, desensitize youths by numbing them emotionally, cause nightmares and sleep problems, impair school performance, and lead to aggressive behavior and bullying.

A 2001 report of the U.S. Surgeon General on the topic of youth violence made a similar judgment. Some meta-analyses of the literature — reviewing psychological research studies and large observational studies — have found an association between violent video games and increased aggressive thinking and behavior in youths. And some casual observers go further, assuming that tragic school shootings prove a link between such games and real-world aggression.

|

Source: PEW Internet & American Life Project, September 2008. |

A more nuanced view

In recent years, however, other researchers have challenged the popular view that violent video games are harmful. Several of them contributed papers to a special issue of the Review of General Psychology , published in June 2010 by the American Psychological Association.

In one paper, Dr. Christopher Ferguson, a psychology professor at Texas A&M International University, argued that many studies on the issue of media violence rely on measures to assess aggression that don't correlate with real-world violence — and even more important, many are observational approaches that don't prove cause and effect. He also cited data from federal criminal justice agencies showing that serious violent crimes among youths have decreased since 1996, even as video game sales have soared.

Other researchers have challenged the association between violent video game use and school shootings, noting that most of the young perpetrators had personality traits, such as anger, psychosis, and aggression, that were apparent before the shootings and predisposed them to violence. These factors make it more difficult to accept the playing of violent games as an independent risk factor. A comprehensive report of targeted school violence commissioned by the U.S. Secret Service and Department of Education concluded that more than half of attackers demonstrated interest in violent media, including books, movies, or video games. However, the report cautioned that no particular behavior, including interest in violence, could be used to produce a "profile" of a likely shooter.

The U.S. Department of Justice has funded research at the Center for Mental Health and Media at Massachusetts General Hospital to better determine what impact video games have on young people. Although it is still in the preliminary stages, this research and several other studies suggest that a subset of youths may become more aggressive after playing violent video games. However, in the vast majority of cases, use of violent video games may be part of normal development, especially in boys — and a legitimate source of fun too. Given the likelihood of individual variability, it may be useful to consider the impact of video games within three broad domains: personality, situation, and motivation.

Personality. Two psychologists, Dr. Patrick Markey of Villanova University and Dr. Charlotte Markey of Rutgers University, have presented evidence that some children may become more aggressive as a result of watching and playing violent video games, but that most are not affected. After reviewing the research, they concluded that the combination of three personality traits might be most likely to make an individual act and think aggressively after playing a violent video game. The three traits they identified were high neuroticism (prone to anger and depression, highly emotional, and easily upset), disagreeableness (cold, indifferent to other people), and low levels of conscientiousness (prone to acting without thinking, failing to deliver on promises, breaking rules).

Situation. Dr. Cheryl Olson, cofounder of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Mental Health and Media, led a study of 1,254 students in public schools (most were ages 12 to 14) in South Carolina and Pennsylvania. The researchers found that certain situations increased exposure to violent video games — such as locating game consoles and computers in children's bedrooms, and allowing older siblings to share games with younger ones. In this study, children who played video games often with older siblings were twice as likely as other children to play mature-rated games (considered suitable for ages 17 and older).

Motivation. In a three-year study, a team led by Dr. Mizuko Ito, a cultural anthropologist at the University of California, Irvine, both interviewed and observed the online behavior of 800 youths. The researchers concluded that video game play and other online activities have become so ubiquitous among young people that they have altered how young people socialize and learn.

Although adults tend to view video games as isolating and antisocial, other studies found that most young respondents described the games as fun, exciting, something to counter boredom, and something to do with friends. For many youths, violent content is not the main draw. Boys in particular are motivated to play video games in order to compete and win. Seen in this context, use of violent video games may be similar to the type of rough-housing play that boys engage in as part of normal development. Video games offer one more outlet for the competition for status or to establish a pecking order.

What parents can do

Parents can protect their children from potential harm from video games by following a few commonsense strategies — particularly if they are concerned that their children might be vulnerable to the effects of violent content. These simple precautions may help:

Check the ESRB rating to better understand what type of content a video game has.

Play video games with children to better understand the content, and how children react.

Place video consoles and computers in common areas of the home, rather than in children's bedrooms.

Set limits on the amount of time youths can play these games. The AAP recommends two hours or less of total screen time per day, including television, computers, and video games.

Encourage participation in sports or school activities in which youths can interact with peers in person rather than online.

Video games share much in common with other pursuits that are enjoyable and rewarding, but may become hazardous in certain contexts. Parents can best protect their children by remaining engaged with them and providing limits and guidance as necessary.

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Children and Video Games: Playing with Violence (Facts for Families, updated Aug. 2006).

American Academy of Pediatrics. "Policy Statement — Media Violence," Pediatrics (Nov. 2009): Vol. 124, No. 5, pp. 1495–503.

Anderson CA, et al. "Violent Video Game Effects on Aggression, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior in Eastern and Western Countries: A Meta-Analytic Review," Psychological Bulletin (March 2010): Vol. 136, No. 2, pp. 151–73.

Ferguson CJ. "Blazing Angels or Resident Evil? Can Violent Video Games Be a Force for Good?" Review of General Psychology (June 2010): Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 68–81.

Ito M, et al. Living and Learning with New Media: Summary of Findings from the Digital Youth Project (The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, 2008).

Lenhart A, et al. Teens, Video Games, and Civics (Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2008).

Markey PM, et al. "Vulnerability to Violent Video Games: A Review and Integration of Personality Research," Review of General Psychology (June 2010): Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 82–91.

Olson CK. "Children's Motivations for Video Game Play in the Context of Normal Development," Review of General Psychology (June 2010): Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 180–87.

Olson CK, et al. "Factors Correlated with Violent Video Game Use by Adolescent Boys and Girls," Journal of Adolescent Health (July 2007): Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 77–83.

For more references, please see /mentalextra .

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.

Free Healthbeat Signup

Get the latest in health news delivered to your inbox!

Thanks for visiting. Don't miss your FREE gift.

The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness , is yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School

Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive health , plus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercise , pain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more.

Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School

Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss ...from exercises to build a stronger core to advice on treating cataracts . PLUS, the latest news on medical advances and breakthroughs from Harvard Medical School experts.

BONUS! Sign up now and get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness

Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School.

Plus, get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness .

APA Reaffirms Position on Violent Video Games and Violent Behavior

- Physical Abuse and Violence

- Video Games

Cautions against oversimplification of complex issue

WASHINGTON — There is insufficient scientific evidence to support a causal link between violent video games and violent behavior, according to an updated resolution (PDF, 60KB) adopted by the American Psychological Association.

APA’s governing Council of Representatives seated a task force to review its August 2015 resolution in light of many occasions in which members of the media or policymakers have cited that resolution as evidence that violent video games are the cause of violent behavior, including mass shootings.

“Violence is a complex social problem that likely stems from many factors that warrant attention from researchers, policymakers and the public,” said APA President Sandra L. Shullman, PhD. “Attributing violence to video gaming is not scientifically sound and draws attention away from other factors, such as a history of violence, which we know from the research is a major predictor of future violence.”

The 2015 resolution was updated by the Council of Representatives on March 1 with this caution. Based on a review of the current literature, the new task force report (PDF, 285KB) reaffirms that there is a small, reliable association between violent video game use and aggressive outcomes, such as yelling and pushing. However, these research findings are difficult to extend to more violent outcomes. These findings mirror those of an APA literature review (PDF, 413KB) conducted in 2015.

APA has worked for years to study the effects of video games and other media on children while encouraging the industry to design video games with adequate parental controls. It has also pushed to refine the video game rating system to reflect the levels and characteristics of violence in these games.

APA will continue to work closely with school officials and community leaders to raise awareness about the issue, the resolution said.

Kim I. Mills

(202) 336-6048

Is Playing Violent Video Games Related to Teens' Mental Health?

New research indicates that video games are not as bad as we once feared..

Posted February 25, 2021 | Reviewed by Matt Huston

Key Points:

- Two recent studies provide insight into whether playing violent video games is related to mental health or aggression .

- Teens who had consistently played violent games for years also reported higher aggression compared to those with gaming patterns that changed over time.

- Researchers found no links between violent video game play and anxiety , depression , somatic symptoms, or ADHD after two years.

With so many kids still home this year, and an apparent increase in the number of teens and adults playing video games, it seems appropriate to re-examine the evidence on whether aggression in video games is associated with problems for adolescents or society. A special issue of Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking published in January did just that. As a parent of three—aware of how video games can suck kids in—and a psychologist working at a social innovation lab that has been a leader in the games for health movement, I’m eager to look at studies that examine teens’ violent video game play and any effects later on in life. I asked, in the ongoing conversation about whether playing games like Fortnite makes teens more aggressive, depressed, or anxious, what do we now know?

After a few decades of research in this area, the answer is not definitive . There was a slew of studies in the early 2000s showing a link between violent video game play and aggressive behavior, and a subsequent onslaught of studies showing that the aggression was very slight and likely due to competition rather than the violent nature of the games themselves. For example, studies showed that people got just as aggressive when they lost at games like Mario Kart as when they lost a much more violent game such as Fortnite . It was likely the frustration of losing rather than the violence that caused people to act aggressively.

Looking at Mental Health and Gaming Over Time

Two studies in the January special issue add to the evidence showing that violent video games may not be as dangerous as they have been made out to be. These studies are unique because they looked at large samples of youth over long periods of time. This line of research helps us to consider whether extensive play in a real-world environment (i.e., living rooms, not labs) is associated with mental health functioning later on in the teen and young adult years.

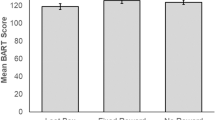

The first study revisited the long-standing debate over whether violent video game play is associated with aggression and mental health symptoms in young adulthood. The study reported on 322 American teens, ages 10 to 13 at the outset, who were interviewed every year for 10 years. The study looked at patterns of violent video game play, and found three such patterns over time: high initial violence (those who played violent games when they were young and then reduced their play over time); moderates (those whose exposure to violent games was moderate but consistent throughout adolescence ); and low-increasers (those who started with low exposure to violent games, and then increased slightly over time). Most kids were low-increasers, and kids who started out with high depression scores were more likely to be in the high initial violence group. Only the kids in the moderates group were more likely to show aggressive behavior than the other two groups.

The researchers concluded that it was sustained violent game play over many years that was predictive of aggressive behavior, not the intensity of the violence alone or the degree of exposure for shorter periods. Importantly, none of the three exposure groups predicted either depression or anxiety, nor did any predict differences in prosocial behavior such as helping others.

The second study was even larger, following 3,000 adolescents from Singapore, and looking at whether playing violent video games was associated with mental health problems two years later. Results showed that neither violent video game play, nor video game time overall, predicted anxiety, depression, somatic symptoms, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder after two years. Consistent with many previous studies, mental health symptoms at the beginning of the study were predictive of symptoms two years later. In short, no connection was found between video games and the mental health functioning of youth.

Taken together, these studies suggest that predispositions to mental health problems like depression and anxiety are more important to pay attention to than video game exposure, violent or not. There is also an implication that any potential effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior would tend to show up when use is prolonged—though the research did not show that gaming itself necessarily causes the aggressive behavior.

So, Should Parents Be Concerned?

These findings are helpful during a year when many kids have no doubt had unprecedented exposure to video games, some of them violent. The most current evidence is telling us that these games are not likely to make our kids more anxious, depressed, aggressive, or violent.

Do parents still need to watch our children’s screen time ? Yes, as too much video game play takes kids away from other valuable activities for their social, emotional, and creative development, such as using their imagination and making things that have not been given to them by programmers (stories, art, structures, fantasy play). Do parents need to be freaking out that our kids trying to find the "imposter" in a game will make them more likely to hit their friends when they are back together in person? Probably not.

We still need to pay attention to mental health symptoms; teens appear to be feeling the effects of the pandemic more than adults, and levels of depression and anxiety have reached unprecedented heights.

So let’s say the quiet part out loud: if they’re using video games to cope right now, it’s not the end of the world, and if they’re struggling psychologically, we should not be blaming the games. Normal elements of daily life have been reduced for teenagers during what should be their most expansive years, for what has become an increasingly large percentage of their lives. It is untenable, and even still, teens are showing us what they always do—that they are adaptive and resilient , and natural harm reduction experts.

As parents, let’s stay plugged in to what they’re going through, and think more about how games can be supportive of well-being. It’s needed now more than ever.

LinkedIn and Facebook image: Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

Coyne, S. M., & Stockdale, L. (2020). Growing Up with Grand Theft Auto: A 10-Year Study of Longitudinal Growth of Violent Video Game Play in Adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0049

Ferguson, C. J., & Wang, C. K. J. (2020). Aggressive Video Games Are Not a Risk Factor for Mental Health Problems in Youth: A Longitudinal Study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(1), 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0027

Kato, P. M., Cole, S. W., Bradlyn, A. S., & Pollock, B. H. (2008). A Video Game Improves Behavioral Outcomes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics, 122(2), e305–e317. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3134

Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (n.d.). Violent video game engagement is not associated with adolescents’ aggressive behaviour: Evidence from a registered report. Royal Society Open Science, 6(2), 171474. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.171474

Danielle Ramo, Ph.D. , is a clinical psychologist, researcher in digital mental health and substance use, and Chief Clinical Officer at BeMe Health, a mobile mental health platform designed to improve teen wellbeing.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 March 2018

Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study

- Simone Kühn 1 , 2 ,

- Dimitrij Tycho Kugler 2 ,

- Katharina Schmalen 1 ,

- Markus Weichenberger 1 ,

- Charlotte Witt 1 &

- Jürgen Gallinat 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 24 , pages 1220–1234 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

556k Accesses

109 Citations

2354 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

It is a widespread concern that violent video games promote aggression, reduce pro-social behaviour, increase impulsivity and interfere with cognition as well as mood in its players. Previous experimental studies have focussed on short-term effects of violent video gameplay on aggression, yet there are reasons to believe that these effects are mostly the result of priming. In contrast, the present study is the first to investigate the effects of long-term violent video gameplay using a large battery of tests spanning questionnaires, behavioural measures of aggression, sexist attitudes, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), mental health (depressivity, anxiety) as well as executive control functions, before and after 2 months of gameplay. Our participants played the violent video game Grand Theft Auto V, the non-violent video game The Sims 3 or no game at all for 2 months on a daily basis. No significant changes were observed, neither when comparing the group playing a violent video game to a group playing a non-violent game, nor to a passive control group. Also, no effects were observed between baseline and posttest directly after the intervention, nor between baseline and a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention period had ended. The present results thus provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games in adults and will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective on the effects of violent video gaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

The associations between autistic characteristics and microtransaction spending

No effect of short term exposure to gambling like reward systems on post game risk taking

Increasing prosocial behavior and decreasing selfishness in the lab and everyday life

The concern that violent video games may promote aggression or reduce empathy in its players is pervasive and given the popularity of these games their psychological impact is an urgent issue for society at large. Contrary to the custom, this topic has also been passionately debated in the scientific literature. One research camp has strongly argued that violent video games increase aggression in its players [ 1 , 2 ], whereas the other camp [ 3 , 4 ] repeatedly concluded that the effects are minimal at best, if not absent. Importantly, it appears that these fundamental inconsistencies cannot be attributed to differences in research methodology since even meta-analyses, with the goal to integrate the results of all prior studies on the topic of aggression caused by video games led to disparate conclusions [ 2 , 3 ]. These meta-analyses had a strong focus on children, and one of them [ 2 ] reported a marginal age effect suggesting that children might be even more susceptible to violent video game effects.

To unravel this topic of research, we designed a randomised controlled trial on adults to draw causal conclusions on the influence of video games on aggression. At present, almost all experimental studies targeting the effects of violent video games on aggression and/or empathy focussed on the effects of short-term video gameplay. In these studies the duration for which participants were instructed to play the games ranged from 4 min to maximally 2 h (mean = 22 min, median = 15 min, when considering all experimental studies reviewed in two of the recent major meta-analyses in the field [ 3 , 5 ]) and most frequently the effects of video gaming have been tested directly after gameplay.

It has been suggested that the effects of studies focussing on consequences of short-term video gameplay (mostly conducted on college student populations) are mainly the result of priming effects, meaning that exposure to violent content increases the accessibility of aggressive thoughts and affect when participants are in the immediate situation [ 6 ]. However, above and beyond this the General Aggression Model (GAM, [ 7 ]) assumes that repeatedly primed thoughts and feelings influence the perception of ongoing events and therewith elicits aggressive behaviour as a long-term effect. We think that priming effects are interesting and worthwhile exploring, but in contrast to the notion of the GAM our reading of the literature is that priming effects are short-lived (suggested to only last for <5 min and may potentially reverse after that time [ 8 ]). Priming effects should therefore only play a role in very close temporal proximity to gameplay. Moreover, there are a multitude of studies on college students that have failed to replicate priming effects [ 9 , 10 , 11 ] and associated predictions of the so-called GAM such as a desensitisation against violent content [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] in adolescents and college students or a decrease of empathy [ 15 ] and pro-social behaviour [ 16 , 17 ] as a result of playing violent video games.

However, in our view the question that society is actually interested in is not: “Are people more aggressive after having played violent video games for a few minutes? And are these people more aggressive minutes after gameplay ended?”, but rather “What are the effects of frequent, habitual violent video game playing? And for how long do these effects persist (not in the range of minutes but rather weeks and months)?” For this reason studies are needed in which participants are trained over longer periods of time, tested after a longer delay after acute playing and tested with broader batteries assessing aggression but also other relevant domains such as empathy as well as mood and cognition. Moreover, long-term follow-up assessments are needed to demonstrate long-term effects of frequent violent video gameplay. To fill this gap, we set out to expose adult participants to two different types of video games for a period of 2 months and investigate changes in measures of various constructs of interest at least one day after the last gaming session and test them once more 2 months after the end of the gameplay intervention. In contrast to the GAM, we hypothesised no increases of aggression or decreases in pro-social behaviour even after long-term exposure to a violent video game due to our reasoning that priming effects of violent video games are short-lived and should therefore not influence measures of aggression if they are not measured directly after acute gaming. In the present study, we assessed potential changes in the following domains: behavioural as well as questionnaire measures of aggression, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), and depressivity and anxiety as well as executive control functions. As the effects on aggression and pro-social behaviour were the core targets of the present study, we implemented multiple tests for these domains. This broad range of domains with its wide coverage and the longitudinal nature of the study design enabled us to draw more general conclusions regarding the causal effects of violent video games.

Materials and methods

Participants.

Ninety healthy participants (mean age = 28 years, SD = 7.3, range: 18–45, 48 females) were recruited by means of flyers and internet advertisements. The sample consisted of college students as well as of participants from the general community. The advertisement mentioned that we were recruiting for a longitudinal study on video gaming, but did not mention that we would offer an intervention or that we were expecting training effects. Participants were randomly assigned to the three groups ruling out self-selection effects. The sample size was based on estimates from a previous study with a similar design [ 18 ]. After complete description of the study, the participants’ informed written consent was obtained. The local ethics committee of the Charité University Clinic, Germany, approved of the study. We included participants that reported little, preferably no video game usage in the past 6 months (none of the participants ever played the game Grand Theft Auto V (GTA) or Sims 3 in any of its versions before). We excluded participants with psychological or neurological problems. The participants received financial compensation for the testing sessions (200 Euros) and performance-dependent additional payment for two behavioural tasks detailed below, but received no money for the training itself.

Training procedure

The violent video game group (5 participants dropped out between pre- and posttest, resulting in a group of n = 25, mean age = 26.6 years, SD = 6.0, 14 females) played the game Grand Theft Auto V on a Playstation 3 console over a period of 8 weeks. The active control group played the non-violent video game Sims 3 on the same console (6 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 24, mean age = 25.8 years, SD = 6.8, 12 females). The passive control group (2 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 28, mean age = 30.9 years, SD = 8.4, 12 females) was not given a gaming console and had no task but underwent the same testing procedure as the two other groups. The passive control group was not aware of the fact that they were part of a control group to prevent self-training attempts. The experimenters testing the participants were blind to group membership, but we were unable to prevent participants from talking about the game during testing, which in some cases lead to an unblinding of experimental condition. Both training groups were instructed to play the game for at least 30 min a day. Participants were only reimbursed for the sessions in which they came to the lab. Our previous research suggests that the perceived fun in gaming was positively associated with training outcome [ 18 ] and we speculated that enforcing training sessions through payment would impair motivation and thus diminish the potential effect of the intervention. Participants underwent a testing session before (baseline) and after the training period of 2 months (posttest 1) as well as a follow-up testing sessions 2 months after the training period (posttest 2).

Grand Theft Auto V (GTA)

GTA is an action-adventure video game situated in a fictional highly violent game world in which players are rewarded for their use of violence as a means to advance in the game. The single-player story follows three criminals and their efforts to commit heists while under pressure from a government agency. The gameplay focuses on an open world (sandbox game) where the player can choose between different behaviours. The game also allows the player to engage in various side activities, such as action-adventure, driving, third-person shooting, occasional role-playing, stealth and racing elements. The open world design lets players freely roam around the fictional world so that gamers could in principle decide not to commit violent acts.

The Sims 3 (Sims)

Sims is a life simulation game and also classified as a sandbox game because it lacks clearly defined goals. The player creates virtual individuals called “Sims”, and customises their appearance, their personalities and places them in a home, directs their moods, satisfies their desires and accompanies them in their daily activities and by becoming part of a social network. It offers opportunities, which the player may choose to pursue or to refuse, similar as GTA but is generally considered as a pro-social and clearly non-violent game.

Assessment battery

To assess aggression and associated constructs we used the following questionnaires: Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire [ 19 ], State Hostility Scale [ 20 ], Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale [ 21 , 22 ], Moral Disengagement Scale [ 23 , 24 ], the Rosenzweig Picture Frustration Test [ 25 , 26 ] and a so-called World View Measure [ 27 ]. All of these measures have previously been used in research investigating the effects of violent video gameplay, however, the first two most prominently. Additionally, behavioural measures of aggression were used: a Word Completion Task, a Lexical Decision Task [ 28 ] and the Delay frustration task [ 29 ] (an inter-correlation matrix is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1 1). From these behavioural measures, the first two were previously used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay. To assess variables that have been related to the construct of impulsivity, we used the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale [ 30 ] and the Boredom Propensity Scale [ 31 ] as well as tasks assessing risk taking and delay discounting behaviourally, namely the Balloon Analogue Risk Task [ 32 ] and a Delay-Discounting Task [ 33 ]. To quantify pro-social behaviour, we employed: Interpersonal Reactivity Index [ 34 ] (frequently used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay), Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale [ 35 ], Reading the Mind in the Eyes test [ 36 ], Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire [ 37 ] and Richardson Conflict Response Questionnaire [ 38 ]. To assess depressivity and anxiety, which has previously been associated with intense video game playing [ 39 ], we used Beck Depression Inventory [ 40 ] and State Trait Anxiety Inventory [ 41 ]. To characterise executive control function, we used a Stop Signal Task [ 42 ], a Multi-Source Interference Task [ 43 ] and a Task Switching Task [ 44 ] which have all been previously used to assess effects of video gameplay. More details on all instruments used can be found in the Supplementary Material.

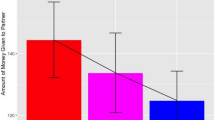

Data analysis

On the basis of the research question whether violent video game playing enhances aggression and reduces empathy, the focus of the present analysis was on time by group interactions. We conducted these interaction analyses separately, comparing the violent video game group against the active control group (GTA vs. Sims) and separately against the passive control group (GTA vs. Controls) that did not receive any intervention and separately for the potential changes during the intervention period (baseline vs. posttest 1) and to test for potential long-term changes (baseline vs. posttest 2). We employed classical frequentist statistics running a repeated-measures ANOVA controlling for the covariates sex and age.

Since we collected 52 separate outcome variables and conduced four different tests with each (GTA vs. Sims, GTA vs. Controls, crossed with baseline vs. posttest 1, baseline vs. posttest 2), we had to conduct 52 × 4 = 208 frequentist statistical tests. Setting the alpha value to 0.05 means that by pure chance about 10.4 analyses should become significant. To account for this multiple testing problem and the associated alpha inflation, we conducted a Bonferroni correction. According to Bonferroni, the critical value for the entire set of n tests is set to an alpha value of 0.05 by taking alpha/ n = 0.00024.

Since the Bonferroni correction has sometimes been criticised as overly conservative, we conducted false discovery rate (FDR) correction [ 45 ]. FDR correction also determines adjusted p -values for each test, however, it controls only for the number of false discoveries in those tests that result in a discovery (namely a significant result).

Moreover, we tested for group differences at the baseline assessment using independent t -tests, since those may hamper the interpretation of significant interactions between group and time that we were primarily interested in.

Since the frequentist framework does not enable to evaluate whether the observed null effect of the hypothesised interaction is indicative of the absence of a relation between violent video gaming and our dependent variables, the amount of evidence in favour of the null hypothesis has been tested using a Bayesian framework. Within the Bayesian framework both the evidence in favour of the null and the alternative hypothesis are directly computed based on the observed data, giving rise to the possibility of comparing the two. We conducted Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVAs comparing the model in favour of the null and the model in favour of the alternative hypothesis resulting in a Bayes factor (BF) using Bayesian Information criteria [ 46 ]. The BF 01 suggests how much more likely the data is to occur under the null hypothesis. All analyses were performed using the JASP software package ( https://jasp-stats.org ).

Sex distribution in the present study did not differ across the groups ( χ 2 p -value > 0.414). However, due to the fact that differences between males and females have been observed in terms of aggression and empathy [ 47 ], we present analyses controlling for sex. Since our random assignment to the three groups did result in significant age differences between groups, with the passive control group being significantly older than the GTA ( t (51) = −2.10, p = 0.041) and the Sims group ( t (50) = −2.38, p = 0.021), we also controlled for age.

The participants in the violent video game group played on average 35 h and the non-violent video game group 32 h spread out across the 8 weeks interval (with no significant group difference p = 0.48).

To test whether participants assigned to the violent GTA game show emotional, cognitive and behavioural changes, we present the results of repeated-measure ANOVA time x group interaction analyses separately for GTA vs. Sims and GTA vs. Controls (Tables 1 – 3 ). Moreover, we split the analyses according to the time domain into effects from baseline assessment to posttest 1 (Table 2 ) and effects from baseline assessment to posttest 2 (Table 3 ) to capture more long-lasting or evolving effects. In addition to the statistical test values, we report partial omega squared ( ω 2 ) as an effect size measure. Next to the classical frequentist statistics, we report the results of a Bayesian statistical approach, namely BF 01 , the likelihood with which the data is to occur under the null hypothesis that there is no significant time × group interaction. In Table 2 , we report the presence of significant group differences at baseline in the right most column.

Since we conducted 208 separate frequentist tests we expected 10.4 significant effects simply by chance when setting the alpha value to 0.05. In fact we found only eight significant time × group interactions (these are marked with an asterisk in Tables 2 and 3 ).

When applying a conservative Bonferroni correction, none of those tests survive the corrected threshold of p < 0.00024. Neither does any test survive the more lenient FDR correction. The arithmetic mean of the frequentist test statistics likewise shows that on average no significant effect was found (bottom rows in Tables 2 and 3 ).

In line with the findings from a frequentist approach, the harmonic mean of the Bayesian factor BF 01 is consistently above one but not very far from one. This likewise suggests that there is very likely no interaction between group × time and therewith no detrimental effects of the violent video game GTA in the domains tested. The evidence in favour of the null hypothesis based on the Bayes factor is not massive, but clearly above 1. Some of the harmonic means are above 1.6 and constitute substantial evidence [ 48 ]. However, the harmonic mean has been criticised as unstable. Owing to the fact that the sum is dominated by occasional small terms in the likelihood, one may underestimate the actual evidence in favour of the null hypothesis [ 49 ].

To test the sensitivity of the present study to detect relevant effects we computed the effect size that we would have been able to detect. The information we used consisted of alpha error probability = 0.05, power = 0.95, our sample size, number of groups and of measurement occasions and correlation between the repeated measures at posttest 1 and posttest 2 (average r = 0.68). According to G*Power [ 50 ], we could detect small effect sizes of f = 0.16 (equals η 2 = 0.025 and r = 0.16) in each separate test. When accounting for the conservative Bonferroni-corrected p -value of 0.00024, still a medium effect size of f = 0.23 (equals η 2 = 0.05 and r = 0.22) would have been detectable. A meta-analysis by Anderson [ 2 ] reported an average effects size of r = 0.18 for experimental studies testing for aggressive behaviour and another by Greitmeyer [ 5 ] reported average effect sizes of r = 0.19, 0.25 and 0.17 for effects of violent games on aggressive behaviour, cognition and affect, all of which should have been detectable at least before multiple test correction.

Within the scope of the present study we tested the potential effects of playing the violent video game GTA V for 2 months against an active control group that played the non-violent, rather pro-social life simulation game The Sims 3 and a passive control group. Participants were tested before and after the long-term intervention and at a follow-up appointment 2 months later. Although we used a comprehensive test battery consisting of questionnaires and computerised behavioural tests assessing aggression, impulsivity-related constructs, mood, anxiety, empathy, interpersonal competencies and executive control functions, we did not find relevant negative effects in response to violent video game playing. In fact, only three tests of the 208 statistical tests performed showed a significant interaction pattern that would be in line with this hypothesis. Since at least ten significant effects would be expected purely by chance, we conclude that there were no detrimental effects of violent video gameplay.